Impact statement

Alternative oxidation reactions (AORs) mark a paradigm shift in electrocatalysis, redefining anodic chemistry by replacing the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) with value-generating, kinetically favorable transformations – such as aldehyde oxidation to acids, or other strategic intermediates. This innovation simultaneously reduces cell voltage, elevates energy conversion efficiency and produces market-relevant coproducts, offering an integrated pathway toward energy and material circularity. By directly addressing the intrinsic bottlenecks of conventional OER – including high overpotentials, as well as electrode and membrane degradation – AOR-enabled platforms deliver robust, scalable and durable catalytic systems. Their deployment supports sustainable chemical synthesis, distributed energy storage architectures and the high-value valorization of renewable or bio-derived feedstocks, all with a minimal carbon footprint. Uniting energy efficiency with selective product formation in AOR-based electrocatalysis constitutes a step change in the field – laying the groundwork for technologies that can redefine industrial electrochemistry, drive large-scale decarbonization and bring the vision of a fully circular, low-carbon economy closer to reality.

Breaking the OER barrier: Toward efficient anodic alternatives

The oxygen evolution (OER) remains a critical bottleneck due to its sluggish four-electron kinetics, high overpotential (~1.23 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) theoretically, often >1.5 V in practice) and the generation of low-value O2. It accounts for over 90% of the energy consumption in hydrogen evolution (HER) and CO2RR systems (Verma et al., Reference Verma, Lu and Kenis2019), and contributes up to 70–80% of the operational costs in industrial-scale hydrogen production, for instance (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Xiang, Huang and Wei2024). Moreover, in membrane-based electrolyzers – such as those with a flow cell configuration commonly used at pilot and industrial scales – O2 crossover can accelerate cathode degradation, severely compromising device stability and lifespan and pose significant safety risks due to the potential for H2/O2 mixing and explosion. In addition, the harsh oxidative conditions required for the OER – often involving higher anodic potentials than many alternative oxidation reactions (AORs), which exacerbate corrosion and delamination – can accelerate damage to electrode supports and current collectors. This effect is particularly pronounced under dynamic operation, thereby limiting the durability of advanced cell architectures (Lei et al., Reference Lei, Li, Jiang, Yang and Yu Xia2024). Furthermore, the evolving O2 bubbles can block active sites, reduce the effective surface area and consequently disrupt mass transport and create local pH gradients that reduce Faradaic efficiency (FE) (He et al., Reference He, Cui, Zhao, Chen, Shang and Tan2023).

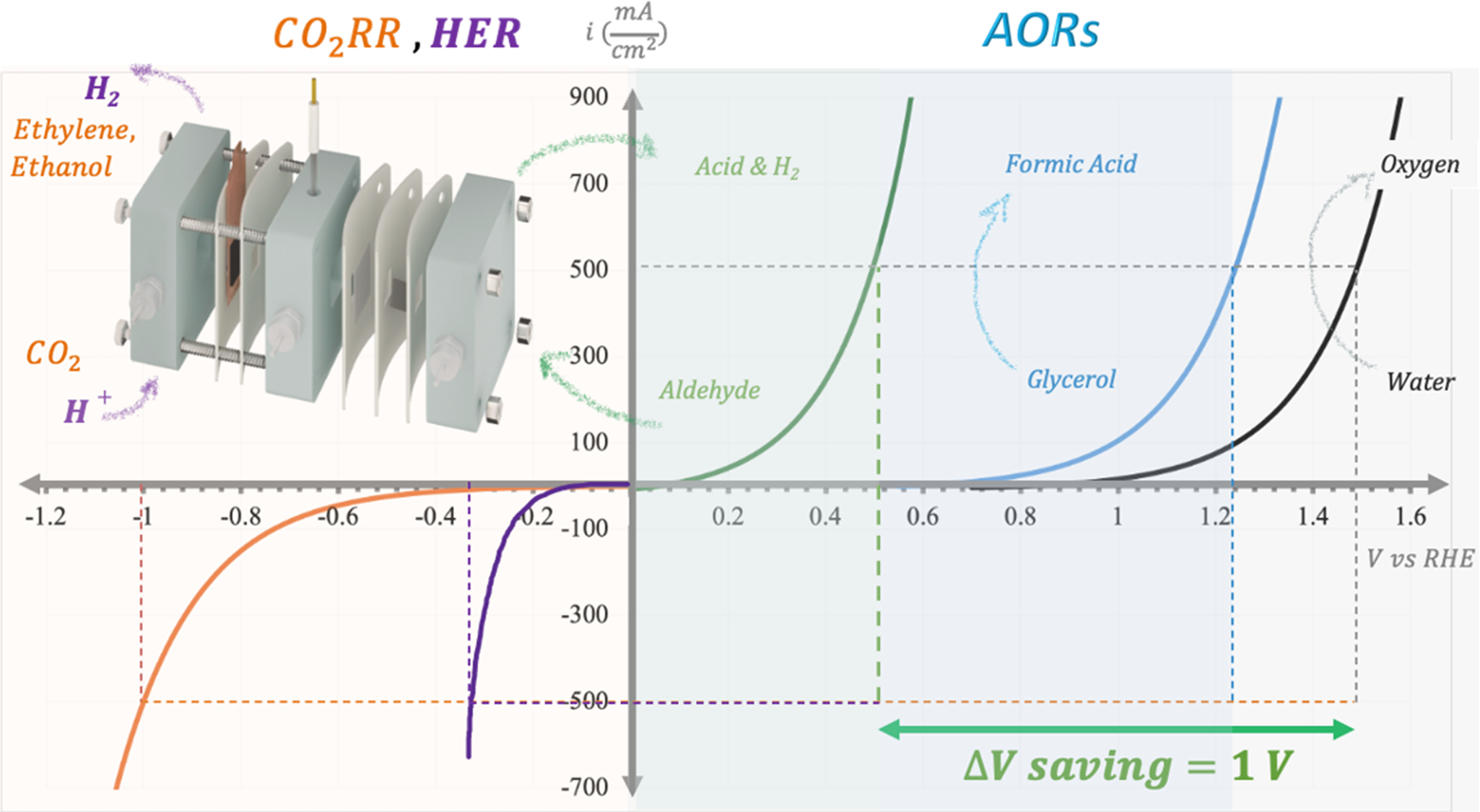

To overcome these limitations, researchers are replacing OER with AORs (Schematic 1) that are thermodynamically favorable (i.e., they require a lower onset potential than OER) and can offer improved kinetics with appropriate catalysts. Many AORs – such as alcohol-to-aldehyde conversions (<1.0 V vs. RHE) and pollutant degradation – proceed via simpler mechanisms (e.g., two-electron pathways), operating at lower potentials than OER. For example, glycerol oxidation reduces cell voltage by ~1.06 V (1.34 V vs. 2.40 V for OER at current densities of 180 mA cm−2), with an associated 49% reduction in energy required for the CO-to-C2H4 process (Yadegari et al., Reference Yadegari, Ozden, Alkayyali, Soni, Thevenon, Rosas-Hernández, Agapie, Peters, Sargent and Sinton2021). It ought to be noted that, however, such efficiencies are typically achieved using noble metal catalysts (e.g., Pt, Ru and Pd), which exhibit superior activity and low-onset potentials under mild electrochemical conditions. Yet, the limited availability and high cost of these materials pose significant barriers to their widespread adoption in large-scale applications. In contrast, when utilizing earth-abundant catalysts – such as nickel (Ni)-based systems stable in alkaline media – the onset potential for glycerol oxidation often remains within the range of 1.0–1.2 V versus RHE, closely approximating that of the OER (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Kumari, Wegner, Pedrini, Adofo, Olean-Oliveira, Hagemann, Kleszczynski, Andronescu and Čolić2025). This diminishes the practical energy advantage that AORs can offer. The situation mirrors challenges faced in fuel cell technologies, where reliance on Pt has hindered broad commercialization despite favorable performance metrics. Consequently, while anodic reactions like glycerol oxidation hold considerable promise, their scalability ultimately depends on the development of cost-effective, durable and catalytically efficient materials capable of operating at significantly lower overpotentials without the use of precious metals.

Schematic 1. Schematic illustration of the electrochemical co-production system, along with I–V curves and the typical required potentials at the cathode and anode for co-electrolysis.

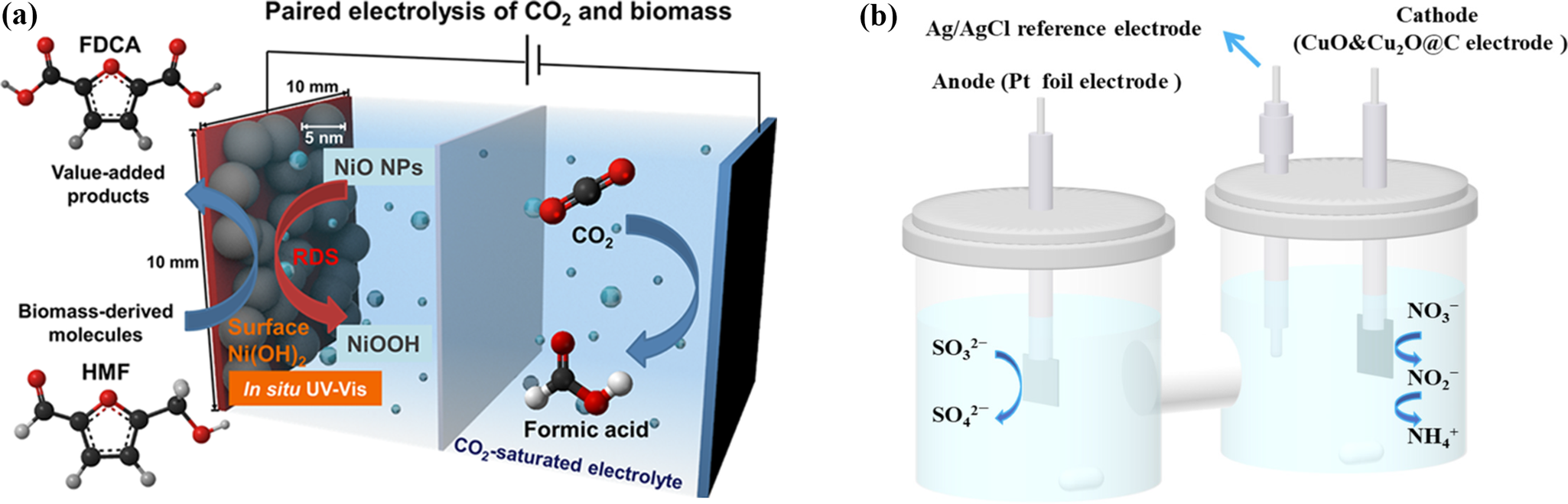

While most reactions align with a 30–50% energy reduction, specific systems exceed this range, emphasizing the viability of replacing OER with sustainable electrochemical processes (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ding, Kang, Zeng, Li, Li, Li, Li and He2023). In a typical aldehyde-to-carboxylic acid electrooxidation, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) is efficiently converted into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) at anodic potentials ranging from ~1.0 to 1.4 V versus RHE, depending on the type of the catalyst (Chai et al., Reference Chai, Jiang, Wang, Ren, Liu, Chen, Zhuang and Wang2022; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Salehi, Guo and Seifitokaldani2022; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Abdinejad, Farzi, Salehi and Seifitokaldani2023; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Yang, Zheng, Salehi, Farzi, Patel, Wang, Guo, Liu and Gao2024; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Jiang, Liu, Ji, Chen and Wang2024) (Schematic 2-a). Given FDCA’s high value and its potential as a precursor for green, degradable polymers, researchers have been motivated to develop hybrid electrochemical systems – such as coupling CO2RR with HMF oxidation – that can operate at cell voltages as low as ~1.40 V (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Yang, Zheng, Salehi, Farzi, Patel, Wang, Guo, Liu and Gao2024), thereby improving overall energy efficiency while simultaneously generating a value-added product. Beyond glycerol and HMF, an increasingly diverse portfolio of organic substrates is being investigated as sustainable anodic alternatives to the OER. These include low-molecular-weight compounds such as ethanol (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Xu, Yu, Deng, Xu, Wang and Wang2024), methanol (Mahmood et al., Reference Mahmood, Aljohani, Aljohani, Bukhari and Abedin2024), ethylene glycol (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kang, Huang, Xu, Wu, Zhang, Zhu, Fan, Fang and Zhou2025), glucose (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhao, Shi, Kang, Das, Wang, Chu, Wang, Davey and Zhang2024), benzyl alcohol (Du et al., Reference Du, Xie, Wang, Li, Li, Li, Song, Li, Lee and Shao2024), formaldehyde (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Dai, Mou, Wang, Cheng and Dong2023), furfural (Begildayeva et al., Reference Begildayeva, Theerthagiri, Lee, Min, Kim, Manickam and Choi2024), acetaldehyde (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Wang, Zhang, Chai, Lu, Wang, Zhao and Ma2022), formic acid (ShyamYadav et al., Reference ShyamYadav, Gebru, Teller, Schechter and Kornweitz2024), acetic acid (Tian et al., Reference Tian, Li, Nelson, Ou, Zhou, Chen, Zhang, Huang, Wang and Yu2023) and amines (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Sun, Zhou, Xie, Zheng, Xu, Sun, Zeng and Zhao2024), alongside more structurally complex feedstocks derived from biomass, including kraft lignin (Han et al., Reference Han, Lin, Salehi, Farzi, Carkner, Liu, Abou El-Oon, Ajao and Seifitokaldani2023), polyols (Li et al., Reference Li, Yan, Xu, Zhou, Xu, Ma, Shao, Kong, Wang and Zheng2022) and carbohydrates (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Zhong and Jin2023).

Schematic 2. Schematic representation of paired electrolysis: (a) cathodic CO2RR coupled with anodic HMFOR (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Balamurugan, Lee, Cho, Park, Seo and Nam2020), and (b) cathodic NO3RR coupled with anodic SO3OR (Cui et al., Reference Cui, Wang, Guo, Zhao and Rohani2023).

These anodic transformations save energy and yield high-value chemicals or offer environmental remediation, thus turning the anode into a site of productivity rather than loss. The integration of biomass-derived substrates and organic feedstocks exemplifies this shift, broadening the scope of sustainable chemical manufacturing. Beyond these systems, a novel anodic reaction is emerging that not only further reduces energy input and produces valuable organic acids via aldehyde oxidation, but also generates hydrogen at the anode. These dual-hydrogen production systems are discussed in literature in which the HER occurs at the cathode, generating hydrogen gas, along with anodic hydrogen production, while aldehyde oxidation – using aliphatic straight-chain, furanic or aromatic aldehydes – replaces the OER at the anode (Bender et al., Reference Bender, Warburton, Hammes-Schiffer and Choi2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Tao, Zhu, Chen, Chen, Du, Zhou, Zhou, Wang and Xie2022). This approach facilitates the oxidation of aldehydes to their corresponding carboxylic acids at a substantially lower applied potential, with an onset ~1 V lower than that of the OER.

Replacing the OER with formaldehyde oxidation to formate (FOR) under alkaline conditions (e.g., 1 M KOH as electrolyte) – using, for example, a Cu3Ag7 bimetallic anode – has yielded FOR and anodic H2 at low voltage (Li et al., Reference Li, Han, Wang, Cui, Moehring, Kidambi, D-e and Sun2023). This system delivered 200% FE, producing H2 at both electrodes and achieving 500 mA cm−2 at 0.60 V versus RHE. Electricity consumption was around 0.30 kWh m−3 H2 at 100 mA cm−2 (vs. 4.10 kWh for water splitting) and 0.70 kWh m−3 H2 at 500 mA cm−2 (vs. 4.70 kWh for water splitting). In another integrated electrochemical system, FOR was synthesized through a paired CO2RR/FOR process, delivering high selectivity at low voltage (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Zhao, Wang and Zou2022). Cathodically, BiOCl nanosheets gave 99% FOR FE at −1.16 V versus RHE (partial j = 36 mA cm−2), with FE >90% across −0.48 to −1.32 V versus RHE. In a flow cell, CO2RR reached 100 mA cm−2 at −0.67 V versus RHE and >200 mA cm−2 with >90% FE between −1.08 and −1.32 V versus RHE with high stability. Anodically, Cu2O showed a low onset (approximately −0.13 V vs. RHE) for the FOR and near-quantitative FOR/H2 selectivity from about 0.05 to 0.35 V versus RHE (FE >90% from −0.05 to 0.35 V vs. RHE) with durability over six cycles. Implemented as a membrane electrode assembly (MEA) flow cell to improve CO2 mass transport and reduce ohmic losses, the CO2RR/FOR pair delivered 100 mA cm−2 at 0.86 V, demonstrating efficient, low-energy electrosynthesis of FOR.

However, the anodic FOR system faces key limitations. Under strong alkaline conditions, formaldehyde undergoes non-electrochemical disproportionation (Cannizzaro reaction) to FOR and methanol, generating FOR without electron transfer to the electrode (Swain et al., Reference Swain, Powell, Sheppard and Morgan1979). This decouples product formation from current, artificially inflates apparent yields and FEs and decreases the actual electrochemical H2 produced per mole of formaldehyde consumed. Moreover, formaldehyde predominantly exists as its hydrated form in water, with the hydrated-to-free aldehyde ratio highly sensitive to pH, concentration and temperature (Li et al., Reference Li, Han, Wang, Cui, Moehring, Kidambi, D-e and Sun2023). These species exhibit different adsorption and oxidation kinetics, making selectivity, activity and reproducibility highly dependent on subtle changes in conditions. Meanwhile, over-oxidation can produce CO or CO2 at off-potentials or on altered surfaces (Du et al., Reference Du, Wei, Tan, Kobayashi, Peng, Zhu, Jin, Song, Liu and Li2022); CO poisons active sites (e.g., Cu, Pt, Ag), while CO2 forms carbonate/bicarbonate in alkaline media, decreasing solubility and causing precipitation or fouling with divalent cations (e.g., Cu2+ cations). Also, reactive aldehydes and intermediates can react with nucleophilic groups (e.g., amines in anion exchange membranes [AEMs]) (Sriram et al., Reference Sriram, Dhanabalan, Ajeya, Aruchamy, Ching, Oh, H-Y and Kurkuri2023), damaging membrane conductivity and stability.

Parallel innovations include nitrate (NO3−)−sulfite (SO32−) co-electrolysis platforms, which achieve above 93% NO3− removal efficiency at 50 mA/cm2 while eliminating secondary waste (Cui et al., Reference Cui, Wang, Guo, Zhao and Rohani2023) (Schematic 2-b). This integrated system couples cathodic NO3− reduction with anodic SO32− oxidation, enabling synergistic pollutant degradation. The process leverages a dual-functional electrode design where NO3− is reduced to N2 or NH3 at the cathode, while SO32− is oxidized to sulfate (SO42−) at the anode.

The double-edged sword of organic oxidation

As discussed, organic electrooxidation presents a promising alternative to the OER, often proceeding at lower overpotentials and enabling energy savings. However, several challenges may limit its practical implementation to some extent. In some cases, certain substrates or catalyst systems still require relatively high overpotentials, diminishing the expected energy efficiency gains; for example, the oxidation of methanol to FOR on Mo–Co4N catalyst requires potentials as high as 1.43 V versus RHE (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Cao, Qin, Chen, Li and Jiao2021), reducing efficiency. Moreover, complex reaction pathways – especially for biomass-derived molecules – often result in multiple competing reactions. For instance, glucose electrooxidation yields a variety of products, including formic acid, gluconic acid, glucaric acid and other partially oxidized compounds, complicating selectivity control (Crisafulli et al., Reference Crisafulli, de la Hoz, de la Osa, Sánchez and de Lucas-Consuegra2025). This complexity prohibits maintaining a high selectivity toward a single desired product, ultimately reducing FE.

The formation of undesired or even toxic byproducts, such as chlorinated organics in systems containing chloride ions, further complicates downstream purification and raises environmental concerns; for example, during electrooxidation in chloride-containing electrolytes, the formation of chlorinated phenols has been reported (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Ye, Xing, Xu, Zhang and Fu2022). Diffusion and mass transport limitations also pose a challenge, particularly in systems with poorly soluble substrates or two-phase mixtures, where the transport of reactants and products to and from the electrode is hindered. For example, the mass transport of kraft lignin molecules in aqueous electrolytes is limited due to their large molecular size and low solubility (Argyropoulos et al., Reference Argyropoulos, Crestini, Dahlstrand, Furusjö, Gioia, Jedvert, Henriksson, Hulteberg, Lawoko and Pierrou2023).

Additionally, electrode stability is a concern, as certain organic intermediates strongly adsorb onto catalyst surfaces, leading to poisoning, corrosion and degradation over time. A well-documented example is the deactivation of Ni-based electrodes caused by strongly adsorbed carbonaceous species formed during glycerol oxidation (Kim and Jack, Reference Kim and Jack2025). Integrating organic oxidation reactions with complementary electrochemical processes – such as CO2RR – to achieve low overall cell voltages requires precise system tuning, which can be challenging to optimize and scale. For instance, coupling CO2RR with HMF oxidation necessitates balancing catalyst activity and electrolyte composition to prevent reactant crossover and maintain a high stability (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Won, Lee and Lee2025).

Endurance under electrochemical stress: Stability challenges ahead

To drive progress in developing coupled cathodic reactions beyond the HER and anodic reactions beyond the OER in electrochemical conversions, key challenges arise across critical domains. Transition metal-based catalysts (e.g., CoP for CO2RR and NiFeO x for organics oxidation) exhibit accelerated dissolution rates (>10−6 M), particularly when paired in non-HER/OER systems. For instance, coupling cathodic CO-to-C2H4 conversion with anodic glycerol oxidation introduces pH-dependent degradation pathways, destabilizing catalysts at operational currents >200 mA/cm2 (Yadegari et al., Reference Yadegari, Ozden, Alkayyali, Soni, Thevenon, Rosas-Hernández, Agapie, Peters, Sargent and Sinton2021). Dynamic potential fluctuations during intermittent operation – common in systems powered by renewable energy – could exacerbate metal dissolution, particularly under open-circuit conditions where redox intermediates accumulate (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Olivier, Pera, Pahon and Roche2024). Supramolecular structures – such as covalent organic frameworks (COFs) or conductive polymers (e.g., conjugated polymers) – could potentially be used as modular support frameworks for electrocatalysts to enhance both stability and performance. COFs offer tunable porosity for stable active sites, efficient charge transfer and resistance to degradation. However, key challenges remain, including scalability and the ability to generate C2 and C2+ products during CO2RR – an outcome that, aside from Cu-based catalysts and a few rare metal-based examples, remains difficult to achieve (Pourebrahimi et al., Reference Pourebrahimi, Pirooz, Ahmadi, Kazemeini and Vafajoo2023).

Coupling reactions with differing pH requirements – such as basic anodic HMF oxidation and nominally neutral cathodic CO2RR (which, although, becomes locally alkaline at high currents) – create steep pH gradients across ion-exchange membranes. These gradients complicate ion transport and pH regulation, leading to overpotentials that increase energy losses and reduce system efficiency (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Zhang, Cheng, Long, Liu, Paul, Fang, Su, Qu and Dai2023). That is, the membrane must manage diverse ionic species under varying local pH, hindering charge balance and causing voltage penalties. Using an alkaline catholyte can reduce pH gradients by aligning cathode and anode conditions, improving ion transport and lowering overpotentials. However, CO2RR in alkaline media suffers from decreased CO2 solubility and carbonate formation (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhou, Luo, Lu, Li, Weng and Yang2023), limiting CO2 availability and complicating product separation. Thus, many systems prefer neutral catholytes to simplify operation and improve CO2 utilization despite pH gradients. Balancing these trade-offs is key to designing efficient, durable paired electrochemical systems. In pH-decoupled systems, thermal expansion mismatches in bipolar membranes become critical, with temperature swings exceeding 30 °C accelerating mechanical degradation and failure (Yue et al., Reference Yue, Zheng, Wang, Wang, Li, Zhang and Ming2025). To address pH-dependent inefficiencies, several established strategies are adapted. These include: (1) designing pH-tolerant catalysts – such as bifunctional transition metal oxides or doped carbons – to balance reaction kinetics (He et al., Reference He, Hu, Zhu, Li, Huang, Zhang, M-S and Tong2024) and (2) developing robust bipolar membranes with thermally stable junctions (e.g., three-dimensional electrospun layers or poly(terphenylalkylene) scaffolds) to reduce thermal stress and ion transport losses (Al-Dhubhani et al., Reference Al-Dhubhani, Post, Duisembiyev, Tedesco and Saakes2023).

To achieve the economic viability of coupling value-added anodic reactions (e.g., HMF-to-FDCA) with cathodic CO2RR – a strategy that reduces energy inputs by 30–50% compared to conventional OER-based systems – researchers must overcome several interrelated challenges. Although lower cell voltages (around 1.0 V vs. >1.5 V for OER) improve energy efficiency, operational stability remains limited. That is, cumulative membrane degradation and catalyst leaching often constrain continuous operation to <100 h. Membrane fouling by organic intermediates (e.g., keto-HMF adsorption on AEMs) increases ionic resistance by 30–50% per day (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Xiao, Wang, Liang, Wei, Wen and Huang2020), while pH-driven dissolution of anodic NiFeO x catalysts, for instance, under alkaline conditions (10−6–10−5 M/h) accelerates material loss (Trzesniowski et al., Reference Trzesniowski, Deka, van der Heijden, Golnak, Xiao, Koper, Seidel and Mom2023).

Techno-economic trade-offs: Balancing value and durability

Economic viability depends on a broad set of interdependent factors, including: (i) aligning anodic product value to offset cathodic costs, (ii) ensuring long-term durability under industrial current densities, (iii) maintaining low overpotentials for efficient large-scale operation, (iv) achieving high selectivity (i.e., FE) to minimize energy consumption per product and (v) reducing downstream product separation costs. Product value alignment necessitates that co-produced high-value organics – anodic or cathodic – must economically offset the production costs of lower-value products (e.g., targeting <$3/kg). For lower-value cathodic products such as FOR (HCOO−), achieving overall economic viability requires the anodic product (e.g., FDCA) to be competitively priced – ideally above $3/kg – to offset costs. This is especially important given the current market imbalance. While global demand for FDCA is around 1.2 million tons per year, production capacity remains limited (~30,000 tons/year as of 2019), with planned expansion to only 1,20,000 tons/year (Böhm et al., Reference Böhm, Lehner and Kienberger2021). Durability benchmarks demand sustained current densities exceeding 400 mA/cm2 with <5% activity loss over 1,000 cycles, necessitating innovations in electrode stabilization. For NiFeO x anodes, for example, phosphate doping enhances structural stability by forming protective iron-phosphate surface layers, reducing dissolution rates under high-current operation (e.g., <0.8% activity loss per cycle at 400 mA/cm2) (Komiya et al., Reference Komiya, Obata, Honma and Takanabe2024). High FE ensures most input current forms the desired products, minimizing energy losses to side reactions. For instance, pairing HCOO− at the cathode with HMF oxidation to FDCA at the anode, FE >90% for FDCA directs electricity efficiently, reducing energy consumption per mole compared to low-FE (<50%) routes (Li et al., Reference Li, Wang, Wang, Azam and Wu2024). This selectivity is crucial for low-value cathodic products, for example, HCOO−, where high-FE anodic products help offset market prices below $1/kg to maintain overall costs under $3/kg. Reducing downstream separation costs is critical, as techno-economic analyses (TEA) often attribute roughly 20–40% of total operating costs in eCO2RR and related processes to product separation and purification, depending on product volatility and mixture complexity (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Muchharla, Dikshit, Dongare, Kumar, Gurkan and Spurgeon2024). For electrocatalytic HMF-to-FDCA, studies report that switching from dilute, mixed-product streams to near-quantitative FDCA formation (FE ≳ 90%) at high concentrations (≥50–100 g/L) enables recovery by simple acidification and crystallization, cutting separation energy demand by about 30–50% relative to more dilute or impure cases that require multistep extractions or resins (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yuan, Huang, Huang, Sun, Qian and Zhang2023). Similarly, for glucaric acid, antisolvent or pH-triggered crystallization from concentrated aqueous solutions (∼100–200 g/L) can reduce separation-related energy use by roughly 20–30% compared to evaporation- or chromatography-heavy routes, provided that side products remain below about 5–10 wt.%. (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Soland, Buss, Honeycutt, Tomashek, Haugen, Ramirez, Miscall, Tan and Smith2022).

Separation science: Isolating value from the mix

Cost-effective separation in integrated electrochemical systems relies on advanced adsorbents, such as hybrid materials combining zeolites and metal–organic frameworks, which offer exceptionally high surface areas – ca. 3,000 m2/g – for efficiently isolating complex mixtures of organic and inorganic products from coupled cathodic and anodic reactions. We envision that effectively coupling CO2RR with anodic HMF-to-FDCA oxidation will require a new generation of hydrophobically tailored adsorbents. By selectively capturing FDCA while actively excluding water, these materials could drastically reduce the energetic burden of downstream dehydration – an inefficiency that continues to hinder the viability of conventional thermal separation processes. Adsorbent replacement costs must stay low (e.g., below $5/kg) to align with the economic viability of systems like CO2-to-C2H4 coupled with glycerol oxidation. Emerging solutions might include COF-coated membranes, which enable simultaneous molecular separation (e.g., isolating FDCA from cathodic FOR) and electrochemical durability during continuous operation – critical for hybrid platforms like nitrate-sulfite co-electrolysis.

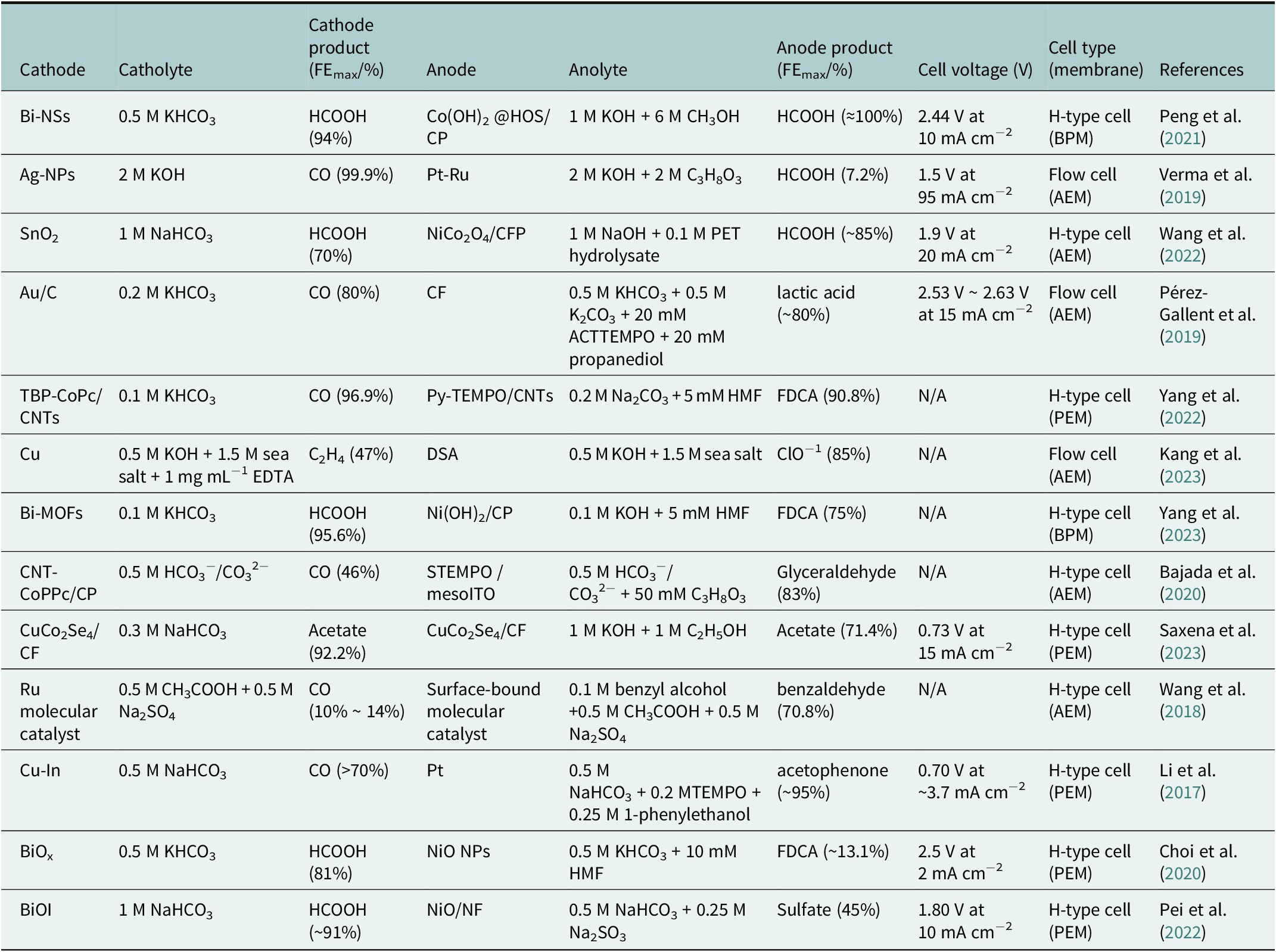

To provide a clear comparison of previously reported integrated eCO2RR systems with AORs, we compiled a summary table (Table 1) highlighting key design and performance metrics.

Table 1. An overview of integrated eCO2RR platforms paired with anodic alcohol, biomass and chlorine oxidation reactions, outlining the electrocatalysts, electrolytes, cell designs, membranes, operating voltages, key products and the highest Faradaic efficiencies achieved for each cathodic and anodic pathway

Toward the next frontier

AORs, such as alcohol-to-aldehyde conversions (e.g., methanol to formaldehyde) or aldehyde-to-acid conversions (e.g., benzaldehyde to benzoic acid), present significant advantages over the OER in hybrid electrochemical systems. The concept of electrolyzer intelligence is vital for advancing future device designs. A critical direction for future research lies in broadening the scope of anodic substrates beyond simple alcohols or aldehydes to include a wider variety of functionalized and biomass-derived aldehydes with valuable oxidation products. Beyond commonly studied molecules like furfural, HMF, benzaldehyde and formaldehyde, promising candidates include vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde), which electrooxidizes to vanillic acid; 2,5-diformylfuran, an HMF derivative convertible to FDCA; protocatechualdehyde (3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde), yielding protocatechuic acid; 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, oxidized to 4-hydroxybenzoic acid; and syringaldehyde, producing syringic acid. Additionally, halogenated aromatic aldehydes – such as chlorobenzaldehyde, fluorobenzaldehyde and bromobenzaldehyde – are valuable due to their applications in pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. They undergo distinct electrooxidation pathways to yield halogenated benzoic acids, which serve as important intermediates in fine chemical synthesis. These substrates have the potential to exhibit efficient electrooxidation at lower overpotentials than the OER, enabling more energy-efficient anodic reactions. Incorporating such aldehydes can significantly reduce the required cell voltage in electrolyzers and paired reactors, leading to improved energy savings and overall process sustainability.

Designing coupled electrochemical systems without membranes – so-called membraneless reactors – holds great promise for significantly reducing energy consumption and system complexity. In such configurations, both cathodic reduction (e.g., CO2RR, HER and NO3RR) and AORs occur in the same electrolyte volume without a physical membrane separating the electrodes. This eliminates membrane-related ohmic losses, lowers fabrication costs and avoids membrane degradation issues. Advanced flow engineering enables effective separation of anodic and cathodic products by exploiting hydrodynamic forces and careful control of electrolyte flow, preventing cross-contamination even at high current densities. By integrating such membrane-free architectures with selective AORs (e.g., using aldehydes or other organic substrates), these systems could achieve substantial voltage and energy savings alongside simultaneous generation of value-added chemicals on both electrodes, marking a promising path toward more efficient, durable and cost-effective electrochemical production technologies.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cat.2025.10009.

Author contribution

S.P. wrote the original draft, and A.S. performed review and editing.

Financial support

A.S. acknowledges support from the NSERC Alliance Mission Grant (ALLRP 577240) and Canada Research Chair program (950-23288).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear Professors Garcia de Arquer and Dinh,

We would like to thank you for the invitation and the opportunity to submit this perspective to the journal Cambridge Prisms: Carbon Technologies, entitled “New Paradigms in Electrocatalysis with Alternative Oxidation Reactions”. We hope this short discussion be an added-value to the journal and help the electrocatalysis community working on CO2 conversion and green fuel synthesis to improve the energy efficiency of their electrocatalytic systems.

We would be happy to further improve the quality of the manuscript upon receiving feedback from the reviewers and editors.

Thanks for your consideration.

Sincerely yours,

Ali Seifitokaldani, PhD, PEng.,

Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair

Department of Chemical Engineering

McGill University

Montreal, Canada