Introduction

Governments are responsive when they shape policies following public demands. This correspondence between government actions and the will of the public is one of the ‘key characteristics’ of democracy (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Przeworski, Reference Przeworski2010). Moreover, it serves as a ‘justification’ for the principle of representation (Powell, Reference Powell2004), as a fundamental indicator of democratic quality (Gilens, Reference Gilens2005), and as a source of political legitimacy for both regimes and the policies they implement (Grimes & Esaiasson, Reference Grimes and Esaiasson2014).Footnote 1 Finally, responsiveness helps citizens choose their preferred candidates during elections by enabling the accountability of incumbents. If the decisions of governments were systematically detached from public opinion, it would become impossible to hold them accountable.

Given the importance of the concept of responsiveness for democracy, recent studies tested if public opinion actually influences the actions of governments. In general terms, early findings looked promising: Many scholars reported congruence between public opinion (or government ideology) and policy outputs (see, e.g., Brooks & Manza, Reference Brooks and Manza2006, Reference Brooks and Manza2008; Budge et al., Reference Budge, Pennings, McDonald and Keman2012; Dipoppa & Grossman, Reference Dipoppa and Grossman2020; Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2002; Kang & Powell, Reference Kang and Powell2010; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Reher and Toshkov2019; Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010; Toshkov et al., Reference Toshkov, Mäder and Rasmussen2020; but see O'Grady & Abou‐Chadi, Reference O'Grady and Abou‐Chadi2019; & Bernardi, Reference Bernardi2020). Scholars found that even in transitioning countries public opinion matters for policymaking. For instance, Roberts and Kim (Reference Roberts and Kim2011) investigated cases in Eastern Europe and reported that economic reforms were more likely when the public supported them.

While these results led to optimism about the functioning of contemporary democracies, other scholars (particularly in later accounts) have called for greater caution: Under some conditions, the previous, promising accounts on responsive governments may not apply. In particular, two factors affect democratic responsiveness: institutions and the economy. Institutions influence the accountability of governments (e.g., Wlezien & Soroka, Reference Wlezien and Soroka2011) and, therefore, have an impact on responsiveness (see, e.g., Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008; Golder & Stramski, Reference Golder and Stramski2010; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Reher and Toshkov2019). And the economy is pivotal as well. For instance, unequal economic conditions among citizens can make governments more responsive to the wealthy (see, e.g., Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hangartner and Schmid2016; Fenzl, Reference Fenzl2018; Gilens, Reference Gilens2009, Reference Gilens2012; Rosset & Kurella, Reference Rosset and Kurella2021; Traber et al., Reference Traber, Hänni, Giger and Breunig2022). Beyond inequality, growth matters as well. A study by Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) reports that bad economic times hinder the ability of policymakers to transform the preferences of their citizens into policies. Elsässer and Haffert (Reference Elsässer and Haffert2022) report similar results on the effects of fiscal constraints in Germany.

This study builds on these results to investigate the effect of the shadow economy. The latter (also known as ‘submerged’ or ‘underground’ economy) includes legal or illegal economic activities that are outside official registers.Footnote 2 As a consequence, these economic transactions are not taxed, do not count towards social contributions and do not enter official statistics. The shadow economy then inhibits the ability of governments to extract economic resources through taxation and makes government statistics less reliable (see, e.g., Schneider, Reference Schneider2018a). By doing so, this study suggests, the shadow economy limits the capacity of governments to expand social policies or decrease taxes – even when public opinion demands similar policy shifts.

This effect is consistent with what policymakers often denounced. For instance, in 2010, Attilio Befera (director of the Italian State Revenue Agency between 2008 and 2014) stated that fiscal evasion is not compatible ‘with any system really democratic’.Footnote 3 The Italian Minister of the Economy, Fabrizio Saccomanni, then added that fiscal evasion impeded equity objectives in Italy.Footnote 4 Similarly, in Greece, some commentators reported that the debt crisis and the consequent austerity policies could be linked, at least partially, to the large revenue losses resulting from widespread tax evasion.Footnote 5

An empirical analysis of data from 15 established democracies in Europe supports this theorized negative effect of the submerged economy on welfare generosity (indicating that an expansion in the underground economy reduces the generosity of the welfare system); and a positive (in sign) effect on taxes that hit specific sectors of the electorate (such as corporate taxation that tends to be higher when the submerged sector becomes larger). In other words, the shadow economy makes governments unable to expand social policies and thirstier for resources. In these circumstances, the empirical analysis supports the conclusion that the shadow economy ends up wiping out the impact of public opinion on policy outputs.

These results have very important implications for both the literature in comparative politics and for policymaking. All countries, including advanced economies, are affected by the underground economy (see Hassan & Schneider, Reference Hassan and Schneider2016).Footnote 6 In recognition of the endemic nature of underground economies, economists have started exploring their determinants (see, e.g., Schneider & Enste, Reference Schneider and Enste2000; Teobaldelli, Reference Teobaldelli2011; Torgler & Schneider, Reference Torgler and Schneider2009) and consequences (for instance, Elgin & Uras, Reference Elgin and Uras2013; Estrin & Mickiewicz, Reference Estrin and Mickiewicz2012; Mazhar & Méon, Reference Mazhar and Méon2017; Schneider, Reference Schneider2018b). Instead, the topic has largely remained at the margins of political science research.Footnote 7 We then know close to nothing about the political consequences of the shadow economy in itself, particularly when we focus on political processes in European established democracies. Therefore, this paper fills an important gap in the political science literature, investigating one of the most basic features of democracy: government responsiveness. By doing so, this paper empirically tests a conclusion that policymakers had previously denounced: Without a well‐functioning tax system, democracy suffers. Additionally, this contribution broadens our perspective on the impact of the informal economy on welfare regimes – an intellectual question still highly understudied but of great importance. If the shadow economy makes policymakers unable to realize generous welfare policies, it also inhibits the resilience of countries against negative economic shocks – something that has become more and more noticeable after the 2008 financial crisis. Finally, the results help us qualify previous findings in the literature: If (good) economic performance is fundamental for responsiveness, countries also need the ability to extract resources from that (larger) pie in order to realize the policies that their publics demand.

Why and when are governments responsive? Institutions, governments and the economy

Most scholars would argue that when governments are systematically unresponsive to their polities, the quality of democracy is low. At least since Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) and Dahl (Reference Dahl1971), democratic theories considered government responsiveness as a key feature of democracy. Dahl explicitly states ‘a key characteristic of democracy is the continuing responsiveness of the government to the preferences of its citizens, considered as political equals’ (Reference Dahl1971, p. 1).Footnote 8 It is now hard to think of representative democracies without assuming that government policies should follow public opinion. Powell (Reference Powell2004) similarly underlines how responsiveness is actually a ‘key justification’ for (representative) democracy itself.

A growing body of scholarly literature has then tested responsiveness through empirical data. Scrutinizing the strength of responsiveness, early studies on the topic often reported optimistic results. On average, the governments of many established democracies in Europe and North America seemed to follow the will of their publics (see, e.g., Brooks & Manza, Reference Brooks and Manza2006, Reference Brooks and Manza2008; Budge et al., Reference Budge, Pennings, McDonald and Keman2012; Cohen, Reference Cohen1999; Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2002; Hobolt & Klemmensen, Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008; Kang & Powell, Reference Kang and Powell2010; Przeworski et al., Reference Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Reher and Toshkov2019; Roberts & Kim, Reference Roberts and Kim2011; Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2004). All these studies found at least some empirical evidence in favour of the relevance of public opinion for policymaking – or for the congruence between government ideology and policy outputs.Footnote 9

Why should governments respond to the public? The main mechanisms that link voters to public policies are based on electoral cycles. If governments want to be (re‐)elected, they need to offer policy platforms that voters find appealing. But voters must also believe that those policy platforms stand a real chance of being implemented if their preferred party wins the election and forms a government. In both electoral and non‐electoral years, governments then have an incentive to follow the public in order to attract voters, appease their supporters and signal that future policies will predictably reflect their campaigns. For these reasons, political parties tend to speak in a way that is coherent with policy outputs (see Bischof, Reference Bischof2018); making it possible (at least for attentive citizens) to know what the government/opposition is doing. Consistent with these conclusions, studies on electoral marginality report that governments and candidates are particularly attentive to public demands in close elections (see, e.g., Griffin, Reference Griffin2006, for the American case; and Andr et al., Reference André, Depauw and Martin2015, for a comparative study). Moreover, empirical studies show that pre‐electoral times tend to induce responsiveness (see Dipoppa & Grossman, Reference Dipoppa and Grossman2020).

At the same time, some factors weaken, if not impede, this connection between voters' preferences and policy outputs. For instance, governments that do not face a credible opposition have fewer incentives to follow the will of their citizens. Institutional settings that do not promote political competition hence weaken responsiveness. In particular, electoral rules (see, among others, Coman, Reference Coman2015; Ferland, Reference Ferland2020; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Dassonneville and Oser2019; Maedgen & Wlezien, Reference Maedgen and Wlezien2024; Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2015) and federalism (see Wlezien & Soroka, Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012) strongly affect the ability of politicians' ears to hear the voices of their citizens. Institutions also affect responsiveness through the creation of veto players (Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2002; Ezrow et al., Reference Ezrow, Fenzl and Hellwig2024). When constitutions empower more veto players, governments have a tighter room of manoeuvre to enable responsive policies.

However, institutions are not the only dimension that matters for responsiveness. A growing body of research has focused on the effect of different economic factors (see, e.g., Böhmelt & Ezrow, Reference Böhmelt and Ezrow2022). For instance, Gilens (Reference Gilens2012) underlines that income inequality makes the US democracy more responsive to richer income groups. This idea resonates in comparative research as well (see, e.g., the accounts from Traber et al., Reference Traber, Hänni, Giger and Breunig2022; and Rosset & Kurella, Reference Rosset and Kurella2021). And inequality is not the only economic factor with an impact on responsiveness. Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) investigated the effect of economic performance. The authors introduced the notion of costs in the theoretical paradigm of responsiveness. Governments face electoral costs when being unresponsive to their publics. However, they also face material costs when implementing policies. Ezrow and colleagues (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) then found that ‘bad economic times’ damage government responsiveness because governments have more limited opportunities to satisfy public demands. Analysing the case of Germany, Elsässer and Haffert (Reference Elsässer and Haffert2022) similarly report the damaging effects of economic constraints on responsiveness in Germany (see also Guinaudeau & Guinaudeau, Reference Guinaudeau and Guinaudeau2023).

This study builds upon these results and on this notion of ‘material costs’ and focuses on the effects of the shadow economy on democratic policymaking. Each economy has two main sectors: one that is official; and one that is submerged (also called shadow or underground). Involving transactions that remain outside of official registers, the shadow economy includes activities that cannot be taxed (see Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Raczkowski and Mróz2015). More than mere tax evasion, the shadow economy deprives states of social security contributions (see Petersen and colleagues, Reference Petersen, Thießen and Wohlleben2010). By doing so, it reduces the fiscal revenues of countries (Schneider & Enste, Reference Schneider and Enste2000).Footnote 10 This effect is irrespective of economic performance, implying that the beneficial effects of growth for policymaking might be moderated by (large) submerged sectors. In other words, governments may find themselves lacking resources not only when the economy is performing poorly, but also when they are unable to extract all possible resources from economic activities even when the economy is thriving.

This paper then develops the argument that larger shadow economies lead to less responsive governments. This argument is based on two main mechanisms, both based on the notions of material costs and of governments' capacity to deliver responsive policies. The first mechanism making governments less responsive to public opinion is the availability of resources that can be employed to finance social policies or to cut taxes. When the shadow economy is large, governments simply have fewer inputs to satisfy the demands of their citizens. This is why a large submerged sector can lead to poorer public services (see, e.g., the early contributions by Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Kaufmann and Zoido‐Lobatón1998, Reference Johnson, Kaufmann and Zoido‐Lobatón1999).Footnote 11 This study, therefore, expects to observe less generous welfare policies when the shadow economy grows larger. Moreover, following the reasoning above, there is also an expectation that a larger shadow economy would lead to higher taxes, particularly in sectors that are less likely to generate widespread malcontent in the electorate – as in the case of corporate taxes. While increases in income or consumption taxes are likely highly unpopular, taxing corporate profits could provide (some) additional resources while insulating governments from strong, generalized public reactions.Footnote 12

Hypothesis Ia: If the shadow economy grows larger, welfare generosity will decrease.

Hypothesis Ib: If the shadow economy grows larger, governments will demand higher taxes, at least in less ‘politically sensitive’ sectors.

Second – yet also related to the capacity of governments to deliver responsive policies – the underground sector reduces the reliability of economic statistics (Schneider & Enste, Reference Schneider and Enste2000; Schneider, Reference Schneider2018a). By doing so, large shadow economies decrease governments' ability to design policies that are able to address societal problems or to face exogenous shocks. If the government's economic intelligence is less reliable, it becomes harder to realize policies able to meet the needs of society. At the same time, as previously underlined, governments have lower resources when the shadow economy is large. These two mechanisms imply that large shadow economies will moderate governments' capacity to deliver policies that follow shifts in public opinion. These conclusions imply that large submerged economies will also affect the ability of governments to translate public preferences into policy outputs.

Hypothesis II: If the shadow economy grows larger, governments will be less responsive to shifts in public opinion.

These hypotheses expand our knowledge of the factors that can inhibit responsive governments in democracies. Importantly, they show that – when it comes to economic performance – growth may not be enough to guarantee responsive governments. More transactions in the economy can help the government only if the latter is able to extract fiscal revenues from those thriving economic activities. This is the first study, to the best of the author's knowledge, to suggest the effects of the shadow economy on democracy, exploring the role of the submerged sector for democratic responsiveness in the context of established Western democracies.

Data and methods

The main hypothesis of this study is that a large submerged economy reduces the resources that governments can employ to realize their policy objectives. Consequently, generous welfare policies and the chances of tax cuts will suffer when submerged economies grow larger (Hypotheses Ia and Ib). Therefore, governments will have lower resources to satisfy public demands (Hypothesis II). To test these hypotheses, this study employs data on (1) policy outputs (the dependent variables), (2) public opinion and (3) the size of the shadow economy.

To measure policy outputs, this paper mainly follows Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) and employs data on welfare state generosity (through the index developed by Scruggs et al., Reference Scruggs, Jahn and Kuitto2017).Footnote 13 The index measures a wide range of social benefits that include employment insurance, sick pay insurance and public pensions. The goal of the Comparative Welfare Entitlements project, which produces the welfare generosity index, has been to provide time‐varying scores of the decommodification index previously proposed by Esping‐Andersen (Reference Andersen1990). This produced z scores for each country‐year characteristic, normed on the cross‐sectional mean and standard deviation, following the formula:

![]() $(x_{knt}\bar{x}_{knt})/ \sigma _{knt}$. The annual generosity index is calculated as the sum of the sub‐indices. This measure offers important benefits over the choice of welfare spending as a measure of policy output, as it is not influenced (unlike the latter) by unemployment rates and by the population of pensioners. Both these variables would indeed influence welfare spending, regardless of factual changes in welfare entitlements. Using welfare generosity shields the results from these interpretative fallacies.

$(x_{knt}\bar{x}_{knt})/ \sigma _{knt}$. The annual generosity index is calculated as the sum of the sub‐indices. This measure offers important benefits over the choice of welfare spending as a measure of policy output, as it is not influenced (unlike the latter) by unemployment rates and by the population of pensioners. Both these variables would indeed influence welfare spending, regardless of factual changes in welfare entitlements. Using welfare generosity shields the results from these interpretative fallacies.

To test Hypothesis Ib, this study further employs data on corporate taxation. The data, retrieved from OECD Statistical Data, measures taxes on corporate profits, that is, taxes on net profits of enterprises, as a percentage of GDP. In this way, the empirical test can investigate the ability of governments to provide generous social policies or to realize tax cuts at varying levels of the shadow economy. Corporate taxes are particularly well‐suited for testing taxation policies. While increases in income or consumption taxes are highly unpopular, taxing corporate profits could insulate governments from strong public reactions. A government thirsty for resources could then increase corporate taxes with lower levels of public disapproval than if it decided to raise consumption (e.g. Value Added Tax, commonly referred to as VAT), labour, property, inheritance or income taxes. This study, therefore, looks at corporate tax rates to investigate the effect of the shadow economy on the thirst of governments for taxes.Footnote 14

To study the effect of public opinion on policy, the rest of the empirical testing will, however, focus only on welfare generosity. This is because there is a lack of correspondence between tax rates and public opinion, as it is shown in the Online Appendix in Section G. This is the reason why corporate taxes are only used to test Hypothesis Ib (that focuses on the incentives of governments, notwithstanding public opinion) but not Hypothesis II. Concentrating on welfare policy entails other important benefits too. First of all, welfare regimes and social policy tend to be highly salient policy issues in established democracies. Instead, precise changes in corporate taxation may remain largely more hidden from public scrutiny – something that appears consistent with the lack of correspondence between public opinion and tax rates shown in the Online Appendix. Second, they can correspond to left‐right divisions better than other policy areas, for which the left‐right divide is fuzzier.Footnote 15 Finally, welfare policies clearly entail the need for resources. Therefore, they are the most significant policy area to test the effect of the shadow economy on government responsiveness.

To measure public opinion (relevant for Hypothesis II), this paper employs the interpolated median voter position on the Left/Right scale (where 1 corresponds to the Left and 10 to the Right). The measure is based on survey responses in the Eurobarometer seriesFootnote 16, with additional data from the Swiss Panel Household Survey for the case of Switzerland. Several previous studies have analysed the relationship between redistributive attitudes and placements on the Left/Right scale (see, e.g., Kang & Powell Reference Kang and Powell2010). These studies report strong correlations between the two (see, e.g., Benoit & Laver, Reference Benoit and Laver2006). McDonald et al. (Reference McDonald, Mendes and Budge2004) also show that elections, despite institutional variations, tend to be good at representing the median voter. Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) also employ this measure to study government responsiveness under different growth rates.

By its very definition, the submerged economy includes activities that are outside of official government records, and hence statistics. To measure the size of the shadow economy, this paper employs the measure developed by Elgin and ztunali (Reference Elgin and ztunali2012) and included in the Quality of Government Institute (University of Gothenburg) Basic Dataset (Dahlberg et al., Reference Dahlberg, Holmberg, Rothstein, Khomenko and Svensson2016, version January 2020). The measure, estimated yearly as a percentage of each country's GDP, is based on a two‐sector dynamic general equilibrium model, calibrated by macroeconomic variables (Elgin & ztunali, Reference Elgin and ztunali2012). This measure is the only one to offer such a large pool of annual data for the considered period. Moreover, this measure, compared to other predecessors, does not lack micro‐foundations (see the critique by Lucas, Reference Lucas1976) and is not based on ad hoc econometric specifications or assumptions (see Elgin & ztunali, Reference Elgin and ztunali2012).

Each model then considers a series of control variables. Controls specifically include economic variables that could influence both the shadow economy and welfare generosity. These are (1) growth (in real terms), (2) employment ratio (as lower employment could push more people into the informal economy but also influence welfare generosity and fiscal policies), (3) trade and (4) taxes on individuals (as higher taxes might influence individuals' willingness to participate in the informal sector). Data for growth and employment ratio are retrieved from the Comparative Political Dataset (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Wenger, Wiedemeier, Isler, Weisstanner and Knópfel2017). Data for trade is from the World Development Indicators of the World Bank and was retrieved from the Quality of Government Standard Dataset (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Dahlberg, Holmberg, Rothstein, Pachon and Axelsson2020). The same dataset has been the source of the data on taxes on individuals (with an indicator on taxes for total income, capital gains and profit taxes on individuals, collected by the International Centre for Tax and Development and the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research, UNU‐WIDER). The models on responsiveness then include country fixed effects to take into account time constant factors. The model for HII also includes data on corruption from the V‐Dem dataset, given the possible complementarity between corruption and the submerged sector, and the theoretical relevance of corruption for policymaking and party politics (Dreher & Schneider, Reference Dreher and Schneider2010).Footnote 17 The Online Appendix shows the robustness of results to the inclusion of additional political and economic variables.

These variables are the main independent factors for the test of Hypotheses Ia, Ib and II. The variables above are observed between 1978 and 2009 (due to data limitations but also to exclude years of the financial crisis and its aftermath, as the crisis posed exogenous constraints on policy choices and, therefore, conditioned the actions of governments). The sampled timeframe reflects data availability also for the welfare generosity index. The empirical test then includes data on 15 countries. Namely, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

To test Hypotheses Ia and Ib, this study employs a first‐difference model. This modelling choice is due to the fact that, by the hypothesis in this paper, a dynamic increase in the shadow economy would suddenly decrease the resources of governments, forcing them to offer less generous welfare and to require higher taxes. To test Hypothesis II, this study instead employs an error correction model (ECM) of the formFootnote 18:

where the operator

![]() $\Delta$ indicates change (difference operator) while

$\Delta$ indicates change (difference operator) while

![]() $t$ indixes the time for countries

$t$ indixes the time for countries

![]() $i$. This specification has the advantage of disentangling short‐ versus long‐term effects of X on Y. The immediate effect of a shock in X on Y is indicated by

$i$. This specification has the advantage of disentangling short‐ versus long‐term effects of X on Y. The immediate effect of a shock in X on Y is indicated by

![]() $\beta _1$. Instead,

$\beta _1$. Instead,

![]() $\beta _2/\alpha _1$ denotes the cumulative (or long‐term) effect (see De Boef & Keele, Reference De Boef and Keele2008). Moreover, modelling policy changes rather than levels prevents potential issues of non‐random error structures (see Tromborg, Reference Tromborg2014). The same estimation technique is proposed by Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) and by Franko (Reference Franko2016). This estimation technique has been chosen also because previous studies (Ezrow et al., Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020; Kang & Powell, Reference Kang and Powell2010) showed that the effect of public opinion on policy tends to be ascribed to the long term. This model specification allows the test to take this time dynamic into consideration.Footnote 19 However, Section F in the Online Appendix replicates the analysis using a different modelling technique that focuses on (lagged) levels. The results show that there is no substantive change to the conclusions of the analyses.

$\beta _2/\alpha _1$ denotes the cumulative (or long‐term) effect (see De Boef & Keele, Reference De Boef and Keele2008). Moreover, modelling policy changes rather than levels prevents potential issues of non‐random error structures (see Tromborg, Reference Tromborg2014). The same estimation technique is proposed by Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) and by Franko (Reference Franko2016). This estimation technique has been chosen also because previous studies (Ezrow et al., Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020; Kang & Powell, Reference Kang and Powell2010) showed that the effect of public opinion on policy tends to be ascribed to the long term. This model specification allows the test to take this time dynamic into consideration.Footnote 19 However, Section F in the Online Appendix replicates the analysis using a different modelling technique that focuses on (lagged) levels. The results show that there is no substantive change to the conclusions of the analyses.

Panel‐corrected standard errors address heteroscedasticity and potential issues of contemporaneously correlated errors (see Beck & Katz, Reference Beck and Katz1995). Further robustness checks are also shown in the Online Appendix.

Empirical results

The effect of the shadow economy on shifts in welfare policies and corporate taxation

The hypotheses of this study start from theorized constraints on policy choices that result from large(r) shadow economies. In particular, Hypotheses Ia and Ib posit that governments facing lower revenues – as happens when the shadow economy becomes largerFootnote 20 – will reduce welfare generosity (Ia) and/or increase taxes (Ib).Footnote 21 To test these hypotheses, this study employs a first difference model.Footnote 22 Expectation is that a positive change in the size of the submerged sector will correspond to a decrease in generosity and an increase in corporate tax rates.Footnote 23

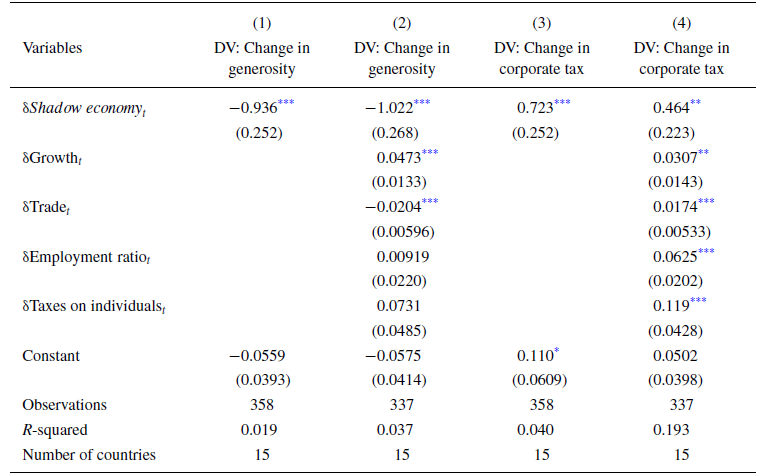

Table 1 presents parameter estimates for the first difference models. Model 1 is for the bivariate relationship between changes in the size of the shadow economy and shifts in welfare generosity. Model 2 adds relevant covariates. In both models, a negative and significant association between the shadow economy and the dependent variable can be observed. When the submerged sector gets larger, the generosity of welfare decreases. The covariates in the models show signs in the expected directions. Higher growth enhances generosity, while an increase in international trade corresponds to a reduced generosity of welfare policy. Model 3 tests the bivariate relationship between changes in corporate taxes and changes in the shadow economy. The estimated coefficient shows a significant and positive relationship: When governments face lower revenues, corporate taxes grow. This relationship holds true even when controlling for additional economic factors that can influence corporate taxation levels, as shown in Model 4. Additionally, it is worth highlighting that the shadow economy prompts governments to increase corporate taxes and taxes on income profits and capital gains, rather than reducing any tax. This is shown in Section D of the Online Appendix. These findings indicate that the shadow economy creates a demand for resources by governments. At the same time, governments seek re‐election and, therefore, need to avoid the blame of increasing taxes for society at large. They, then, become more likely to increase taxes that hurt only smaller sections of the electorate. This, however, comes at a cost: these taxes contribute marginally – in advanced European economies – to overall revenues. Consequently, they become a finger in the dike and are unlikely to really compensate for the loss in revenues coming from a large underground economy.

Table 1. Evaluating the effect of the shadow economy on welfare generosity and corporate taxation

Note: Entries show the estimated coefficients, with panel‐corrected standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable (DV) is

![]() $\delta$ Welfare

$\delta$ Welfare

![]() ${\rm generosity}_t$ for Models 1 and 2; and

${\rm generosity}_t$ for Models 1 and 2; and

![]() $\delta$ Corporate taxationt for Models 3 and 4. Countries included in the analysis are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The data in the analysis includes observations for the years going from 1978 to 2009.

$\delta$ Corporate taxationt for Models 3 and 4. Countries included in the analysis are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The data in the analysis includes observations for the years going from 1978 to 2009.

***p

![]() $ \nobreakspace <\nobreakspace $0.01, **p

$ \nobreakspace <\nobreakspace $0.01, **p

![]() $<\nobreakspace $0.05, *p

$<\nobreakspace $0.05, *p

![]() $<\nobreakspace $0.1.

$<\nobreakspace $0.1.

The results of the study provide support for both Hypotheses Ia and Ib. The presence of a large shadow economy constrains governments' policy choices, leading to lower welfare generosity and higher taxes. Appendix B further shows consistent evidence about the hypothesized link between the shadow economy and revenues (i.e., that the shadow economy is linked to decreased revenues). Appendix C further demonstrates the correspondence between government revenues and the generosity of the welfare system, aligning with the hypotheses put forward in this study.

The effect of the shadow economy on responsiveness to the median voter

Previous research has examined the conditions under which governments are responsive to public opinion. This study, however, is the first to test the possible impact of the shadow economy on government responsiveness, with the hypothesis of a negative relationship between the two. When the submerged sector is large, by the hypothesis of this study, governments face limitations in resources for expanding welfare policies, and cannot consequently meet the demands of their publics.

To test this hypothesis, this study employs data from 15 European democracies. The main dependent variable of interest is the change in welfare generosity.Footnote 24 Governments are responsive when the position of public opinion is a relevant predictor of policy shifts. In this context, a negative coefficient indicates responsiveness, as higher values (indicating more rightward public opinion positions) correspond to consistent policy adjustments.

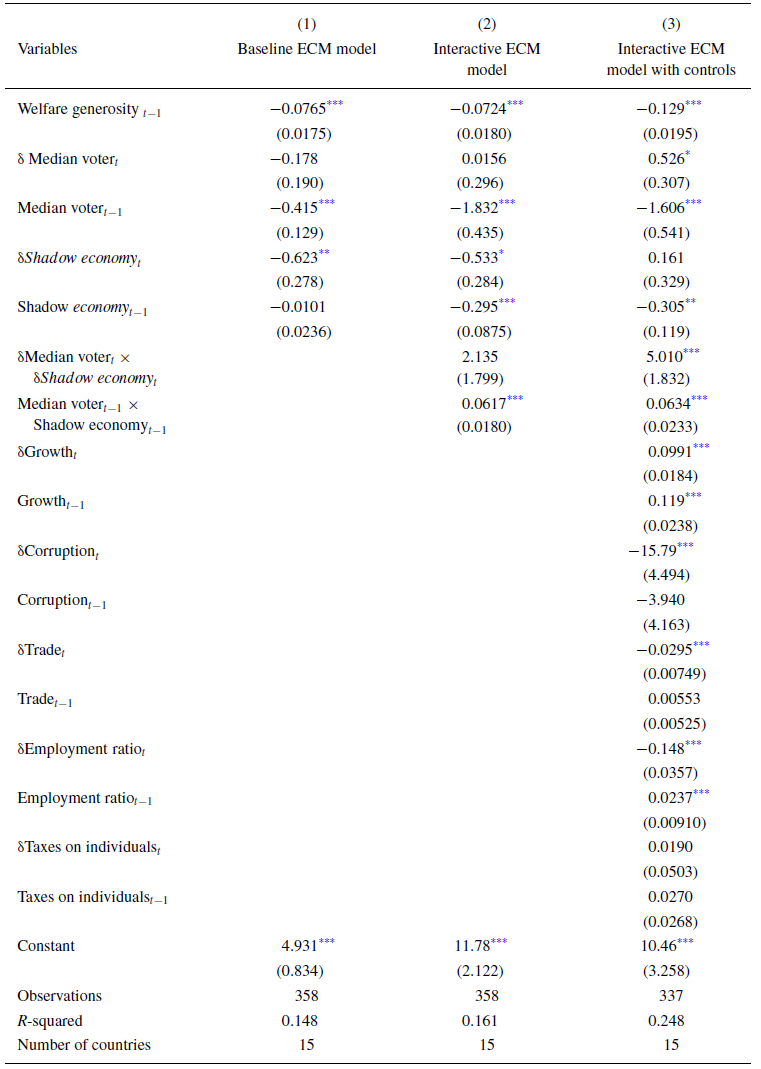

Model 1 in Table 2 displays the results for the ‘baseline’ ECM model, that is, for the specification without interaction effects. This model shows that the lagged position of the public matters for policymaking. As anticipated, the effect is negative, indicating that as the public shifts towards the right of the political spectrum, the generosity of welfare states decreases. The results also indicate that this is a long‐term effect. In the short term, the effect goes in the expected direction but it does not reach statistical significance. This is consistent with previous findings (see Ezrow et al., Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020).

Table 2. Evaluating the effect of the median voter on welfare generosity

Note: Entries show the estimated coefficients, with panel‐corrected standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is

![]() $\Delta$ Welfare

$\Delta$ Welfare

![]() ${\rm generosity}_t$. GDP growth is expressed as a change in GDP from the previous year, in real terms (i.e., net of inflation). The V‐Dem index of political corruption indicates greater corruption with higher scores. Country fixed effects are included through country dummies for all three models but excluded from the presentation. Countries included in the analysis are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The data in the analysis include observations for the years going from 1978 to 2009.

${\rm generosity}_t$. GDP growth is expressed as a change in GDP from the previous year, in real terms (i.e., net of inflation). The V‐Dem index of political corruption indicates greater corruption with higher scores. Country fixed effects are included through country dummies for all three models but excluded from the presentation. Countries included in the analysis are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The data in the analysis include observations for the years going from 1978 to 2009.

Abbreviation: ECM, error correction model.

***p

![]() $<$ 0.01, ** p

$<$ 0.01, ** p

![]() $<$0.05, * p

$<$0.05, * p

![]() $<$ 0.1.

$<$ 0.1.

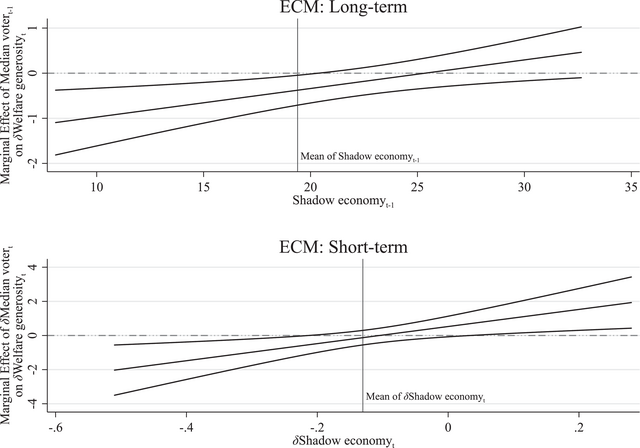

But what about the role of the submerged sector? The shadow economy exhibits a negative coefficient in the short term (as expected, an expansion in the shadow economy corresponds to a decrease in generosity). However, Hypothesis II focuses on the conditional effect of public opinion at varying sizes of the shadow economy. Model 2, therefore, introduces an interaction effect between public opinion and the submerged sector, while Model 3 adds control variables to test the stability of the reported parameter. Figure 1 graphically displays the conditional coefficient in Model 3. The graph illustrates that the shadow economy significantly moderates the impact of public opinion. When the shadow economy is small, public opinion and policy outputs align closely. However, as the shadow economy grows larger, the strength of the association between public opinion and policy outputs diminishes and then vanishes. Once the shadow economy reaches approximately 20.5 per cent of GDP (a value not far from the mean for the sample), the coefficient for public opinion becomes statistically indistinguishable from zero. It is worth noting that during the considered period, Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain reported shadow economies larger than 20.5 per cent of GDP. This result supports Hypothesis II. Furthermore, the Online Appendix demonstrates that this result remains robust even when including different sets of control variables, encompassing both institutional and economic factors. Footnote 25 We can, therefore, observe that a decrease in the size of the shadow economy correlates with government responsiveness to public opinion in policy outputs. Conversely, an increase in the size of the shadow economy corresponds to a diminished relevance of public opinion in shaping policy outcomes.Footnote 26

Figure 1. Conditional effect of public opinion on welfare policy at varying sizes of the shadow economy.

Note: The graph shows the coefficient of the Median voter

![]() $_{t-1}$ conditional on the Size of the shadow economy

$_{t-1}$ conditional on the Size of the shadow economy

![]() $_{t-1}$, based on Model 3 in Table 2.

$_{t-1}$, based on Model 3 in Table 2.

The analysis, therefore, provides compelling evidence supporting the main hypothesis of this paper, which suggests that the shadow economy hampers responsiveness. This conclusion holds true even when performing a series of robustness checks as shown in the Online Appendix.

Conclusion

Government responsiveness is a crucial measure of democratic quality. This is why, scholars are increasingly evaluating it with empirical data. These empirical accounts revealed that some conditions, economic and institutional, can hinder governments' responsiveness to public demands. In particular, recent studies have emphasized that responsiveness comes with costs, and governments cannot satisfy public demands unless they have the necessary resources to do so.

Expanding on the notion of the costs of responsiveness, this study specifically examined the impact of the shadow economy on government responsiveness. It proposed that a large shadow economy could impede responsiveness by limiting governments' access to the resources they need to expand social policies or cut taxes – and by worsening the quality of governments' economic intelligence.

To test this argument, this study started with the association between the shadow economy and (a) the generosity of welfare systems and (b) tax rates imposed on corporate profits. The findings revealed that as the shadow economy expands, welfare regimes become less generous. Subsequently, the study explored government responsiveness to public opinion across different sizes of the shadow economy. The results revealed that as the shadow economy grows larger, governments face more limited options, diminishing the influence of public opinion on welfare policy changes. This suggests that government responsiveness, a crucial indicator of democratic quality, is compromised when the submerged sector constitutes a significant portion of the overall economy. Furthermore, the results indicate that even short‐term increases in the size of the shadow economy can impede responsiveness, while a movement in the opposite direction could stimulate it.

These results have important implications for the literature in political science. First of all, the study's focus on the impact of the shadow economy on government responsiveness offers a fresh perspective, as previous research has primarily examined other factors (such as clientelism or corruption) while neglecting the political consequences of the shadow economy, particularly in European countries. This paper, therefore, contributes to the existing literature because it shows that the shadow economy has decisive political implications for established Western democracies. Specifically, the shadow economy should be considered alongside other economic factors (such as economic growth and income inequality) that tend to impede the influence of public opinion on policymaking – decreasing the overall quality of democracy. Moreover, the findings reinforce the notion that strong economic performance is not enough for a functioning democracy. Governments need to have the capacity to generate revenues in order to effectively translate public preferences into actionable policies.

These conclusions have important implications for policymaking. First of all, when informal activities reduce government revenues, democracy suffers in various ways. Over time, this can result in a growing disconnect between governments and their public. When this happens, it is easy to predict rising levels of public dissatisfaction and growing distrust towards institutions. As policy‐makers already noted, the shadow economy is incompatible with a truly democratic regime. Second, the results highlight that the shadow economy diminishes the generosity of welfare systems and creates incentives for governments to increase (some) taxes. On the one hand, this implies that citizens – and disproportionately more those in disadvantaged positions – will suffer under large shadow economies. At the same time, the heightened fiscal pressures on specific groups can have negative consequences for economic performance and may exacerbate informal economic activities. Addressing large shadow economies with appropriate measures should, then, be a priority for any country that wants to remain (or aspires to be) truly democratic and economically competitive.

Before concluding, it is important to acknowledge that this study focused on two primary mechanisms linking the shadow economy to government responsiveness: the availability of resources for governments in the presence of a large shadow economy and the impact of the shadow economy on governments' economic intelligence. However, there may be other channels through which the shadow economy affects the relationship between governments and citizens. One such mechanism could concern the effect of large unofficial sectors on the tax morale of citizens – and, consequently, on their willingness to contribute to public goods (Torgler, Reference Torgler2005). The shadow economy can signal to citizens that the society is unwilling to commit to public goods and that fiscal institutions are unable to enforce the collection of taxes. Consequently, we can expect a negative effect of the shadow economy on tax morale and an increasing cynicism about the importance of electoral promises. In turn, this could have negative consequences for accountability and for the need of governments to respond to shifts in public opinion (rather than to specific selectorates). This is a situation similar to what happens in clientelistic regimes (see Afonso et al., Reference Afonso, Zartaloudis and Papadopoulos2015; Kitschelt & Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007, among others), or when governing parties face an incentive to represent the interests of rentier groups (Herb, Reference Herb2005). Exploring these additional mechanisms would be a fruitful avenue for future research. Furthermore, this study examined the shadow economy as a whole, without dissecting its specific components. Future studies could delve into the various aspects of the shadow economy and explore their distinct impacts on policymaking.

Acknowledgements

The author wants to express the most sincere gratitude to Despina Alexiadou, Ruth Dassonneville, Lawrence Ezrow, Timothy Hellwig, Werner Krause, Jochen Rehmert, Verena Reidinger, Jonathan Slapin, the anonymous reviewers and the editors of the European Journal of Political Research. Their comments and insights have been an invaluable contribution to the development of this study.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

All data and replication files (Stata) are freely available through the repository Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0LKAJX

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

t−>1

t−>1 t−>1

t−>1