Between 2014 and 2022, the US government imposed targeted sanctions on numerous Russian individuals and entities in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, cyberattacks, and interference in US elections. The Alfa Bank, the largest private bank in Russia, and its owners – Peter Aven, Mikhail Fridman, German Khan, and Alexey Kuzmichev – remained untouched by US sanctions during this period. However, the Pandora Papers, released in 2021, and the investigative work of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) reveal how these individuals pre-emptively reshuffled their assets worth billions of dollars through the British Virgin Islands, Cyprus, and other prominent offshore financial centers following the 2014 sanctions.Footnote 1 In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and subsequent US and EU sanctions on all Alfa Bank operations and its founders, these oligarchs continued to utilize offshore financial centers to safeguard and expand their wealth under sanctions, with some accounts even showing activity on the very day sanctions were imposed.Footnote 2 The secrecy of offshore financial jurisdictions not only allowed Alfa Bank and its owners to sanction-proof their assets, but also complicated US efforts to monitor elites’ assets and use sanctions as a policy tool.

In this paper, we identify a hide-and-seek game between the US government increasing its efforts to monitor international finance and secrecy-seeking actors evading scrutiny by moving money to offshore financial jurisdictions. As a snapshot of this dynamic, we examine how changes in US efforts to monitor compliance with and enforce its sanction programs influence the demand for offshore financial services by actors in targeted countries. We examine actors blacklisted via financial sanctions, as well as their non-targeted co-nationals.Footnote 3 We introduce each set of actors’ incentive structures for seeking anonymity in their financial dealings following the imposition of targeted sanctions.

Using data from the Office of Foreign Asset Control’s (OFAC’s) Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list, the ICIJ’s database on offshore leaks, and additional country-level economic and political data, we investigate the relationship between targeted sanctions and the financial strategies adopted by sanctioned actors, as well as their non-targeted co-nationals. Specifically, we show that increases in the number of targeted sanctions against a country’s individuals or firms are associated with heightened offshore financial activity originating from that country. These new offshore transactions occur in low-supervision jurisdictions offering weak regulation and anonymity of financial flows and ownership. Notably, SDN sanctions do not predict a shift towards high-supervision jurisdictions with stringent regulations and transparency. Thus, efforts to monitor and prevent illicit finance via SDN sanctions may inadvertently incentivize non-targeted actors to pre-emptively relocate their assets, specifically to opaque and harder-to-regulate offshore locations. Our findings offer novel insights into the evolving landscape of international finance and the strategies employed by various actors to navigate the complexities of financial regulation. We also complement the literature on the unintended economic consequences of sanctions, highlighting how sanctions can push economic activity underground and make it harder to monitor financial activity in the long run (Andreas Reference Andreas2005). Furthermore, we underscore the importance of offshore finance for political science and international relations scholars aiming to understand the modern financial landscape and its implications for co-operation and security.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: first, we discuss the symbiotic relationship between financial liberalization facilitated by governments and the pursuit of financial anonymity by secrecy-seeking actors. We then outline our theory connecting governments’ increased need to monitor international finance and changes to the demands for offshore financial services. To lay the foundation for our theoretical framework, we first identify the web of economic and political actors navigating the evolving financial landscape. We then examine what their goals are and how they pursue them in the context of the hide-and-seek game. Subsequently, we apply our theoretical framework to the case of US-targeted sections. We present our empirical strategy, conduct statistical analysis, discuss the findings, and conclude by exploring the implications of our results for scholars and policy makers.

A Vicious Cycle: Financial Liberalization and Financial Secrecy

Financial globalization has been on the rise, and the movement of capital has never been easier (Gygli et al. Reference Gygli, Haelg, Potrafke and Sturm2019). For decades, liberal governments have facilitated the free flow of capital across borders, allowing it to move to where its productivity is highest. This has promoted efficiency and prosperity (Quinn and Inclan Reference Quinn and Inclan1997; Altamura Reference Altamura2017), enhanced risk sharing, and spurred economic growth (King and Levine Reference King and Levine1993; Henry Reference Henry2003). Governments have also contributed to the growth of offshore financial centers (OFCs), the proliferation of financial service providers and intermediaries, and the symbiotic relationship they all have with financial liberalization (Palan Reference Palan1988; Braun et al. Reference Braun, Krampf and Murau2020). However, relaxing control over transnational capital flows, providing less regulated spaces outside domestic scrutiny, and the simultaneous growth of OFCs characterized by weak regulation and secrecy in financial flows (Binder Reference Binder2023) may have inadvertently facilitated illicit financial activity.Footnote 4 OFCs have provided cartels, terrorist organizations, and violent actors with unprecedented access to international finance and a veil of anonymity in their dealings (Sharman Reference Sharman2010 a; Andreas Reference Andreas2004). This evolving financial landscape necessitated increased monitoring and enforcement measures to combat illicit financial activity, even as countries strive to do so without jeopardizing lucrative financial flows and alienating economic elites (Major Reference Major2012). In response, actors engaged in criminal financial activities have adopted more sophisticated methods to evade detection and maintain their secrecy. Before introducing our theoretical framework explaining the tension between financial liberalization and financial secrecy, we first examine how various relevant economic and political actors navigate this evolving financial landscape.

Governments: Architects of Financial Liberalization

Growing financial openness has been a key driver of economic growth and prosperity; two central goals for governments. While financial liberalization is often welfare-enhancing, it also introduces two interconnected trade-offs that create significant costs for governments in pursuing these goals.

First, financial liberalization can undermine government efforts to enforce laws and regulations domestically and internationally. The surge in the volume of financial transactions and the proliferation of novel financial instruments encouraged by governments have also inadvertently facilitated illicit activities. Criminal actors rely on money to carry out their operations, and they seek investment opportunities to increase profit while diversifying their assets and minimizing the risk of detection. With the increasing number and types of international financial entities and the rising volume of capital flows, barriers to entry and concerns about secrecy may be reduced, prompting an increase in illicit financial activities (Cobham and Jansky Reference Cobham and Jansky2020).

Second, governments face a trade-off between maximizing taxation revenue and exerting control over citizens’ assets or creating a welcoming, low-regulation environment for domestic and foreign investors to accumulate wealth (Pistor Reference Pistor2020). As a part of their strategy for navigating this trade-off, governments have also supported the growth of offshore financial centers, either directly or indirectly, by providing tacit agreement (Ogle Reference Ogle2017). By allowing and even sometimes encouraging the use of OFCs, governments were able to pursue contradictory economic policies and support the creation of jurisdictions with reduced regulations without undermining their claim to regulate and tax economic actors and activities at home (Palan Reference Palan1988, Reference Palan2003; Fernandez et al. Reference Fernandez, Hendrikse and Klinge2023).

In addition to governments’ desire to optimize regulation of capital flows in and out of their home state, there are incentives to monitor the broader international financial landscape. Such incentives are especially important for powerful actors such as the United States or the European Union. This furthers several goals, such as monitoring illicit financial flows that directly benefit criminal or violent activity, pulling the purse strings of elites to accomplish broader policy objectives, and ensuring the efficacy of international financial regulation to avoid crises. Although financial liberalization may benefit domestic firms, many governments face political incentives to maintain a modicum of control over the international financial landscape. The growth of offshore financial centers, coupled with the increasing ease of carrying out illicit activities via global financial networks, has necessitated increased scrutiny of global finance to differentiate legal from criminal transactions.

Offshore Financial Centers

Offshore finance centers complicate government efforts to distinguish between legal and criminal transactions. While offshore finance refers to financial services provided to non-residents by banks and intermediaries, OFCs are jurisdictions characterized by low or no taxes, tight financial secrecy, and weak regulation (Sharman Reference Sharman2010 a; Cobham et al. Reference Cobham, Jansky and Meinzer2015; Binder Reference Binder2023). It is estimated that 50 per cent of the world’s cross-border assets and liabilities pass through OFCs (Garcia-Bernardo et al. Reference Garcia-Bernardo, Fichtner, Takes and Heemskerk2017).

To attract clients and remain competitive, OFCs may be incentivized to deregulate, minimize barriers to entry, and reduce monitoring, taxation, fees, and bureaucracy (Dionne and Macey Reference Dionne, Macey and Morriss2010). Their services are in very high demand among individuals and firms engaged in both legal and illegal transactions who are seeking to maximize the value of their assets and minimize investment risks. Like countries competing to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), offshore jurisdictions balance minimizing the costs of financial services and promoting a reputation for asset security. The market for offshore financial services is thus driven by diverse consumer needs across a spectrum ranging from secrecy to security (Cobham et al. Reference Cobham, Jansky and Meinzer2015). This means that some OFCs specialize by deregulating and offering cheap, poorly regulated services to remain competitive, while others are able to market their adherence to international financial standards for security. The market for OFC services and variation among OFCs remains underexplored, and this paper offers one explanation for the demand for poorly regulated offshore financial jurisdictions: blacklisted entities via US targeted sanctions or their co-nationals aiming for de-risking or sanction-proofing following sanctions.

Offshore Investors Engaged in Legal Activity

Importantly, engaging in offshore finance is not inherently illegal or nefarious, and the majority of offshore accounts are estimated to be held legally. Investors often use OFCs to avoid or reduce tax liabilities (Zucman Reference Zucman2014); safeguard wealth from litigation, political instability, or violation of private property rights at home; avoid financial regulation such as capital controls (Binder Reference Binder2019; Sharman Reference Sharman2010 a); or escape low profitability and weak infrastructure at home (Foad and Lundberg Reference Foad and Lundberg2017). But they also often benefit from decreased bureaucratic red tape (Findley et al. Reference Findley, Nielson and Sharman2014), reduced cost of transactions, and increased efficiency. Factors such as the rule of law, corruption levels, and regulatory quality in the home country compared to offshore jurisdictions influence individuals and firms’ decisions on whether to utilize offshore financial services and which OFCs to work with. Individuals and firms seeking safety, stability, or a higher yield from their investments in comparison to what is available by keeping their assets in their home countries should be expected to have different preferences for their assets than those seeking secrecy for criminal activity or sanction-proofing.

Offshore Investors Engaged in Illicit Activity

While legal investors can benefit from the efficiency and reduced costs of the services provided by OFCs, the anonymity they offer is often a necessity for actors engaged in illicit activities (Sharman Reference Sharman2011; Freeman and Ruehsen Reference Freeman and Ruehsen2013; Baradaran et al. Reference Baradaran, Findley, Nielson and Sharman2014; Findley et al. Reference Findley, Nielson and Sharman2014; Dubowitz Reference Dubowitz2012; Masciandaro Reference Masciandaro2017). Terrorist organizations, nuclear proliferation financiers, drug dealers, and sanction evaders often resort to money laundering to make illegally gained proceeds appear legal (Freeman and Ruehsen Reference Freeman and Ruehsen2013). They place money earned via illicit activity into the financial system and layer it through a series of transactions to obscure its origin.Footnote 5 Shell and front companies, difficult-to-trace transactions in virtual environments (Irwin et al. Reference Irwin, Slay, Choo and Lui2014), and currency smuggling are also common methods for facilitating illicit activity through OFCs. These types of illicit financial activities require the confidentiality OFCs offer to escape the scrutiny of their own governments and international monitoring. Asset seizure and loss of access to financial services are primary concerns for blacklisted actors and those fearing future sanctions, which provokes movement into the minimally regulated jurisdictions that are best able to obscure investors’ money.

Enablers in International Finance

The growth of OFCs, as well as the size and scale of illicit financial flows (Cobham and Jansky Reference Cobham and Jansky2020), has been accompanied by the expansion of offshore financial service providers: banks, accountants, audit firms, law firms, tax advisory businesses, and trust and corporate service providers.Footnote 6 As private and profit-seeking entities, these intermediaries often position themselves as intentional or unwitting enablers of illicit activity and capitalize on the unmatched confidentiality offered by the jurisdictions they are based in (Ge et al. Reference Ge, Kim, Li and Zhang2022 a; Levi Reference Levi2022).

One notable example of enablers of illicit activity in OFCs is Mossack Fonseca, a major law firm and offshore financial service provider based in Panama. ICIJ records revealed how they acted as a proxy for Petropars, an Iranian oil company blacklisted by the United States to limit the financing of Iran’s nuclear program.Footnote 7 Similarly, they also enabled the operations of DCB Finance Limited, a Pyongyang front company registered in the British Virgin Islands, offering financial services to North Korea’s main arms dealer and its financial arm, both sanctioned for supporting North Korea’s nuclear programs.Footnote 8 In both cases, offshore financial services and the leeway they provide to financial enablers allowed sanctioned entities to move money and conduct lucrative business transactions via shell and front companies, bypassing US restrictions.

The Hide and Seek Game

As discussed above, governments navigate the trade-off between supporting financial liberalization and the growth of offshore financial services while also investing in scrutiny of global finance to be able to distinguish between legal and criminal financial activities. To fight international crime and limit financing of illicit activities, governments ‘follow the money’ and monitor international finance in partnership with other governments and private stakeholders, such as banks (Liss and Sharman Reference Liss and Sharman2014). The US government, for instance, has strengthened its monitoring efforts by introducing the Bank Secrecy Act, Money Laundering Control Act, and Money Laundering and Financial Crimes Strategy Act, among others, in partnership with the Financial Action Task Force, an intergovernmental body aimed at preventing illegal financial flows (Levi and Reuter Reference Levi and Reuter2006; Vlcek Reference Vlcek2011).Footnote 9 As governments scale up their monitoring and anti-money-laundering initiatives, criminal actors continuously seek new and creative ways to sustain their operations while escaping detection. This research investigates the interplay between heightened monitoring and enforcement efforts in the global financial system and the use of offshore financial services by secrecy-seeking actors to circumvent these efforts while maintaining their monetary operations.

We argue that actors seeking to safeguard and grow their wealth, including those involved in illicit financial activities, must adapt to increasingly rigorous global financial monitoring and enforcement systems. To achieve their goals, actors with illicit transactions or the ones anticipating being labeled as such, as well as the actors in need of moving assets expediently or with little oversight, are expected to shift their assets towards low-supervision jurisdictions. These low-supervision jurisdictions offer obscurity as a byproduct of their lack of regulation. We thus argue that heightened scrutiny and enforcement measures (seeking) from the international community should only increase the demand for the services offered in low-supervision jurisdictions (hiding). In the following section, we detail our theory in the context of US targeted sanctions and discuss how the intensified efforts to enforce US sanctions may have amplified the need for the financial secrecy that low-supervision offshore jurisdictions can provide.

Targeted Sanctions and Offshore Financial Services

The US government has increasingly employed targeted financial sanctions to achieve various objectives (Drezner Reference Drezner2015), from combating drug trafficking to deterring nuclear proliferation (Biersteker et al. Reference Biersteker, Eckert and Tourinho2016). These sanctions are designed to inflict costs on leaders and elites directly responsible for the policies sanctions aim to change. Thus, they target individuals, firms, and organizations (Cortright and Lopez Reference Cortright and Lopez2002; Drezner Reference Drezner2011; Arnold Reference Arnold2016). The United States, as the most prolific imposer of targeted sanctions, is uniquely positioned to monitor compliance with and enforce its sanctions globally due to its financial clout (Farrell and Newman Reference Farrell and Newman2019), centrality in global financial markets (Oatley et al. Reference Oatley, Winecoff, Pennock and Danzman2013), and the status of the US dollar as the world’s principal reserve currency (Norrlof Reference Norrlof2014).Footnote 10 The US government often utilizes its unique position to accompany sanctions with sophisticated financial instruments to stop the movement of funds to or from specific countries or corporations, freeze assets of individuals and firms, and limit or ban access to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).

Parallel to the increased use of targeted sanctions, the United States has intensified its commitment to enhancing monitoring and enforcement efforts to bolster the efficacy of its sanctions programs.Footnote 11 This includes strengthening the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC), which serves as the primary US agency responsible for administering and enforcing US targeted sanctions. As part of this effort,

OFAC publishes a list of individuals and companies owned or controlled by, or acting for targeted countries. It also lists individuals, groups, and entities, such as terrorists and narcotics traffickers designated under programs that are not country-specific. Collectively, such individuals and companies are called ’Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List’ or ’SDNs.’ Their assets are blocked and U.S. persons are generally prohibited from dealing with them. Footnote 12

Furthermore, the US government heavily relies on extra-territorial provisions that extend beyond domestic firms and encompass foreign firms, thereby broadening the reach of sanctions enforcement (Cilizoglu and Early Reference Cilizoglu and Early2021). OFAC further bolsters its monitoring and enforcement capabilities by wielding substantial powers to fine sanction violators. Over the years, there has been a significant increase in the number of individuals, firms, and entities blacklisted on the SDN lists, as well as in the fines and penalties imposed on non-compliant firms (Early and Preble Reference Early and Preble2020).

Blacklisted Actors and Offshore Financial Centers

As US financial monitoring and enforcement efforts tighten globally, blacklisted actors must adapt to sustain and expand their operations under sanctions. We argue that low-regulation offshore jurisdictions offer these actors an opportunity to shield their transactions from scrutiny. Shell companies established in these jurisdictions often have no physical presence and generate little to no independent economic value.Footnote 13 By utilizing offshore services offered in low-regulation OFCs, blacklisted actors can effectively mask the true originators or end-users of their transactions (Ruehsen and Spector Reference Ruehsen and Spector2015). They can also transfer money to sanctioned entities and purchase sanctioned goods with a lowered risk of getting detected. Additionally, the services offered by low-regulation jurisdictions are often easy and quick to set up and use without much paperwork or disclosure requirements (Findley et al. Reference Findley, Nielson and Sharman2014; Sharman Reference Sharman2010 b).

To illustrate, consider how Russian oligarchs targeted by US sanctions use OFCs to seek anonymity and evade sanctions. A US Senate report revealed how Russian oligarchs used high-value art transactions to evade US sanctions since 2014. These transactions, amounting to over $91 million, involved intricate trails leading back to anonymous offshore shell companies tied to Russian oligarchs and significantly undermined US sanctions.Footnote 14

A similar sanction evasion scheme was used by Iran. The Iranian regime is known to successfully leverage offshore shell companies to generate revenue and transfer funds while under sanctions, enabling them to support activities such as backing terrorist groups and advancing ballistic missile development. For instance, the Iranian airline, Mahan Air, blacklisted by OFAC in 2011, used multiple front companies to transfer funds and procure aviation parts without detection.Footnote 15 These front companies allow funds and materials to change hands multiple times before being forwarded to Iran. These cases highlight the difficulty of enforcing targeted sanctions in this very complex financial environment.

In response, OFAC works to trace these shell companies and blacklist those involved in illicit transactions. Between 2012 and 2018, more than ten new front companies affiliated with Mahan Air were added to the SDN list. However, criminal actors counter these efforts by establishing fresh shell companies under new identities and addresses, continuing to undermine US sanctions. OFCs – particularly those with a competitive advantage in low-supervision service provision – facilitate this adaptive response by obstructing international financial transparency. In both the Iranian and Russian cases, offshore shell companies helped blacklisted entities and their partners continue their financial activity without (or with delayed) detection.

Co-nationals and Offshore Financial Centers

However, the increased demand for anonymity is not limited to actors already blacklisted by the US. We argue that non-targeted individuals and firms in countries with active sanctions programs, referred to here as co-nationals, may also have a heightened need to seek anonymity in their dealings, making low-regulation OFCs an attractive destination for their assets regardless of whether they engage in legal or criminal activity. These examples also highlight the complexity of the modern financial system, characterized by convoluted ownership structures, shell companies, and newly found opportunities to commit financial crimes.

First, some co-nationals may credibly worry that they could be subjected to financial sanctions themselves under the same sanctions program in the future. These individuals or firms include political or economic elites who are close to the government or involved in designing or implementing the policy under contention. As a result, they may take pre-emptive action to sanction-proof their assets (Cilizoglu and Bapat Reference Cilizoglu and Bapat2020).Footnote 16 In this case, sanction-proofing can look like transferring the ownership of legal entities and property to relatives or trusted figureheads, ensuring control and access to wealth if sanctions were to be imposed on them. Wealth can also be hidden through real estate and luxury item purchases via companies registered in low-regulation OFCs. For example, Suleiman Kerimov, one of the wealthiest Russian oligarchs and a member of the Russian Federation Council, is reported to have done just that between the years following the 2014 sanctions on Russia and 2018, when he was eventually targeted by US sanctions himself. ICIJ records describe billions of dollars in transactions between firms owned by Kerimov’s family and shell companies owned and administered by figureheads, registered in various OFCs. In addition to those transactions, documents describe billions of dollars in loans during this period from OFC-registered financial firms to companies controlled by Kerimov’s family.Footnote 17 In sum, actors seeking sanction-proofing are likely to be attracted to low-regulation OFCs offering anonymity and a shield of assets against potential future sanctions.

Actors seeking to sanction-proof their assets will also be attracted to low-regulation OFCs due to their easy and quick-to-set-up services without significant paperwork or disclosure requirements (Findley et al. Reference Findley, Nielson and Sharman2014; Sharman Reference Sharman2010 b). In a time-sensitive environment where OFAC lists are frequently updated (even daily), minimizing the risk of not being able to move their assets offshore can potentially be a priority for successfully sanction-proofing assets, increasing their demand for low-regulation OFCs following the sanctions they observe targeting their fellow citizens.

Second, co-nationals might benefit from moving their assets to low-regulation offshore jurisdictions as a part of their de-risking strategies, even if they do not anticipate being placed on the SDN list. Sanctions levied on actors within a country may create additional negative externalities for co-nationals as they seek to move assets, which may increase the preference for easy-to-access, low-cost, low-supervision jurisdictions. Specifically, co-nationals may be subject to predatory policies by their governments as they attempt to withstand the costs of sanctions, such as increased risk of private property violations (Peksen Reference Peksen2017) or heavy taxation. Further, sanctions are known to be associated with increased repression (Wood Reference Wood2008) and political violence (Lektzian and Regan Reference Lektzian and Regan2016) as well as a heightened risk of currency crises (Peksen and Son Reference Peksen and Son2015) in targeted countries. Lastly, under a targeted sanctions program, banks and financial institutions are often the first ones to be blacklisted. Co-nationals, regardless of their level of concern about getting blacklisted, are likely going to be restricted in their access to their funds, savings, and investments if the banks and financial institutions they work with are targeted with sanctions. This, in turn, can drive these actors to engage in de-risking by moving their assets abroad to ensure greater flexibility and security. All of these potential consequences of sanctions can alter co-nationals’ strategies regarding their asset allocations and can make offshore financial investment more attractive compared to their domestic economies. The application of US sanctions may provoke risky financial decisions in the short term to avoid any of these consequences in the long term, making access to low-supervision jurisdictions a more expedient choice.

We argue that this hide-and-seek game between the US government and secrecy-seeking actors has systemic consequences for global finance. In sum, we argue that increased monitoring and enforcement in the financial realm, as exemplified by the application of US sanctions, has inadvertently increased demand for offshore financial services offered by low-regulation jurisdictions for the purposes of obscuring investors’ identities and asset flows and de-risking asset allocations. An increase in targeted US sanctions against actors from a particular country indicates intensified scrutiny by the US government towards that country’s financial inflows and outflows.

This pattern is similar to how comprehensive trade sanctions incentivize firms and individuals in the domestic economy to move ‘underground’ and increasingly use shadow and informal sectors and transactions (Andreas Reference Andreas2005; Early and Peksen Reference Early and Peksen2019). This, in turn, weakens the effectiveness of trade sanctions (Early and Peksen Reference Early and Peksen2020) and creates long-term systemic impacts on states’ ability to domestically and internationally monitor domestic economies and punish illegal activity.

In the context of targeted sanctions and efforts to monitor global financial flows, blacklisted entities are more likely to seek anonymity in their financial dealings to avoid asset seizures. Co-nationals seeking to sanction-proof their assets in anticipation of additional US scrutiny can be expected to obscure the paper trail by relocating their assets as well. Similarly, co-nationals seeking de-risking strategies will also be attracted by the opportunity to act fast and avoid the long-term risks of keeping their assets at home or in high-regulation jurisdictions upon observing increased scrutiny of their home country. We argue that in newly monitored financial environments, operationalized by increased SDN targeting at the country level, firms and individuals from the same home country will have an increased demand for offshore financial services in low-supervision offshore jurisdictions. This increase in offshore transactions should only be observed between entities from the recently targeted country and jurisdictions with limited transparency, supervision, and co-operation with global monitoring infrastructure. In contrast, increases in targeted sanctioning should have no effect on the number of transactions between entities in the targeted country and better supervised and internationally co-operative jurisdictions.Footnote 18

This leads us to our testable hypotheses:

HYPOTHESIS 1a: Increases in targeted (SDN) sanctions to entities within a country correspond with an increase in transactions between entities from that country and low-supervision offshore jurisdictions.

HYPOTHESIS 1b: This effect is limited to low-supervision offshore jurisdictions.

Research Design: OFAC Sanctions and Offshore Transactions

To evaluate the relationship between targeted sanctions and changes in the offshore financial landscape, we bring together two main data sources. We first collect information about sanctions levied against SDNs by the US Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) (of the Treasury, n.d.). The data allowing us to trace offshore financial transactions is compiled by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. We then include data about the home countries of entities involved in offshore financial transactions.Footnote 19 Collectively, these data allow us to assess if increases in targeted sanctions on individuals or firms within a country provoke additional transactions to low-supervision offshore jurisdictions after accounting for other country-level push factors.

To classify ‘low-supervision’ and ‘high-supervision’ offshore jurisdictions, we rely on the IMF’s categorization of offshore jurisdictions into three groups of Offshore Financial Centers (IMF Background Paper (2000). Group I are ‘jurisdictions generally viewed as cooperative, with a high quality of supervision, which largely adhere to international standards’. Group II are ‘jurisdictions generally seen as having procedures for supervision and co-operation in place, but where actual performance falls below international standards, and there is substantial room for improvement’. Group III are jurisdictions ‘generally seen as having a low quality of supervision, and/or being non-co-operative with onshore supervisors, and with little or no attempt being made to adhere to international standards’. Group I includes jurisdictions such as Switzerland and Luxembourg, Group II includes the likes of Bermuda and Malta, and Group III includes jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, and Panama.Footnote 20 We combine groups II and III – the groups distinguished by performance well below international standards in supervision and co-operation – into a low-supervision group of jurisdictions and treat Group I as high-supervision jurisdictions. Our theory suggests that firms or individuals that have been blacklisted or are engaging in sanction-proofing will prefer jurisdictions that do not meet international standards for supervision and monitoring. In contrast, firms or individuals moving assets offshore to escape asset seizure, volatility, or high taxes in their home country will prefer transactions with high-supervision, co-operative jurisdictions.Footnote 21

The list of SDN entities, hosted on the OFAC website, is continually updated. Entities sanctioned under a variety of countries (Iran) or programs (counter-terrorism sanctions) can be added, removed, or edited at any time. This poses a challenge for researchers interested in changes over time, as only the current set of sanctioned entities is available online. However, OFAC also publishes yearly lists of activities in PDF form, which include the date on which entities are added or removed, the location of the sanctioned entity, the program under which the entity was sanctioned, and whether the entity is a firm or an individual. From these lists, we built a monthly database.Footnote 22 We tally the number of firms and individuals added per month, taking note of the target’s location and the program under which the target is sanctioned. These data are available over the years 2000–20.

The information about offshore entities comes from the ICIJ, a non-profit organization of international journalists highlighting issues of global corruption and financial crime. In addition to reporting about tax havens and illicit financial flows, the organization compiled a database of secret companies, trusts, and funds created in offshore locales that ‘link to people and companies in more than 200 countries and territories’ (International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, n.d.). These data include information from several data leaks: the Offshore Leaks (2013), Bahamas Leaks (2016), Panama Papers (2016), Paradise Papers (2017 and 2018), and the Pandora Papers (2021). Our analyses make use of the Offshore Leaks, Panama Papers, and Paradise Papers. We exclude the Bahamas Leaks due to missing temporal and location information and exclude the Pandora Papers to ensure temporal overlap with our SDN data. The characteristics of each leak are similar, as they capture information given to journalists about the creation of shell companies and their connections offshore. The Panama Papers, for example, represent information leaked from Mossack Fonseca, a leading creator of shell companies used to obscure asset ownership for both illicit and legal reasons. The Paradise Papers were a similar leak, but encompassing several other important firms that create shell companies. Because the only available data is what has been leaked to journalists, they should not be seen as a random sample representative of the entire offshore population but rather as a convenience sample (Landers and Behrend. Reference Landers and Behrend2015). Because of this, we conduct our analysis both on the entire sample (pooling all three leaks together) as well as on each leak/set of papers independently. Should the same effect be observed across each sample, despite that the actors leaking each set of documents, the original journalistic source, and the process of leak compilation into data differ, this should increase confidence in the external validity of our findings.Footnote 23 Comprehensively, these data extend until 2020 and identify when companies or individuals initiate offshore transactions as well as the entities’ country of origin.

Our interest in the timing of new offshore activity in relation to changes in sanctioning and the origin country of assets moving offshore prompts us to make several additional changes. First, we limit our data to offshore activity in which a start month and year are known, meaning that we can assess movement to low- and high-supervision offshore jurisdictions as a result of sanctioning behavior in the previous month. Second, we remove observations for which country-level location information (gleaned from registered addresses) is unknown for any of the entities in each offshore transaction. We then aggregate these data to create a country-month level of observation, where the observation itself is the number of new offshore transactions per jurisdiction type. For example, if one transaction is between Canada, the United States, and the Cayman Islands, we create one row in our data for US–Cayman Islands and one for Canada–Cayman Islands. We then sum the number of new transactions each origin country (here, the United States and Canada) has to each type of offshore financial jurisdiction (low or high supervision). Our expectation is that increases in sanctioning provokes an increase in two kinds of new transactions to low-supervision jurisdictions: blacklisted entities further obscuring their financial trail and co-nationals attempting to sanction-proof their assets. Sanctioning should have no effect on movement to well-regulated, high-supervision jurisdictions.Footnote 24 , Footnote 25

We include all possible origin countries to account for the many factors that may provoke offshore investment and ensure we do not bias our sample towards countries with ‘riskier’ investors.Footnote 26 As such, many observations see no offshore connections in a given month.Footnote 27 We combine these data with the monthly SDN counts per origin country. After merging in the explanatory variables capturing other ‘push factors’ for moving money offshore discussed below, this gives us over 38,000 observations for the combined data and roughly 28,000 per leak over the period of 2000–20.Footnote 28

Firms’ and individuals’ reasons for pursuing offshore investment are varied, and may not be driven by a desire to conceal assets or sanction-proof. Investors may move holdings offshore when their home states’ extractive capacity increases or when financial and political conditions become more risky, making tax havens relatively more attractive. We include several additional variables to account for alternative explanations that may push investors abroad. Perhaps the most prominent alternative explanation for offshore activity is high taxes. This would indicate that individuals or firms are moving their assets offshore to avoid increases in taxation. We account for this with a measure retrieved from Our World in Data that measures taxes on the incomes, profits, and capital gains of individuals and corporations as a share of country GDP (UNU-Wider Government Revenue Dataset 2020). We code for an increase in the tax capacity of a state in the year prior.Footnote 29

Violence, instability, and political upheaval may also provoke the movement of assets either from regime challengers or threatened elites. To account for this, we include a variable from the Varieties of Democracy project (VDem) (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Alizada, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Hicken, Hindle, Ilchenko, Krusell, Luhrmann, Maerz, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Paxton, Pemstein, Pernes, Von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tan Tzelgov, Ting Wang, Wig, Wilson and Ziblatt2021) capturing the ‘degree of threat from anti-system movements’. Countries assigned the highest value are experiencing significant, destabilizing upheaval from opposition groups – such as Haiti or the Central African Republic – whereas countries given a low value may have anti-system movements present but experience minimal threat from such movements.Footnote 30 In addition to domestic instability and increases in extractive capacity in the origin country, another alternative explanation for increases in offshore financial transactions is investors seeking access to the US dollar. To account for this, we include the differential between the US interest rate (EFFR) and the offshore interest rate (LIBOR) (Effective Federal Funds Rate 2024; U.S. Dollar (Eurodollar) LIBOR Rates 2024). Global oil prices and an abundance of petrodollars may also provoke additional movement offshore. As such, we include the global oil price (Global price of Brent Crude [POILBREUSDM] 2024). Both of these two indicators are lagged to capture financial dynamics in the previous month.

Our dependent variable for each model is the number of new offshore connections for each type of offshore jurisdiction (low- or high-supervision). However, we face a challenge when observing this outcome: a choice in the type of jurisdiction can only be made by entities that move their assets offshore in the first place. In addition, the same factors that push individuals or firms to move assets offshore may also affect their movement into a specific category of offshore financial jurisdiction. Because of these concerns, a two-stage selection model (Heckman) is appropriate.Footnote 31 In the first stage, we estimate the effect of sanctions, country-level push factors, and indicators of the global appeal of the US dollar on whether or not a country sees individuals or firms engaging in new offshore activity. In the second stage, we estimate the effect of newly applied SDN sanctions in the previous month as well as several other push factors on the number of new offshore transactions per jurisdiction type.Footnote 32 , Footnote 33 Below, we present tables and discuss the results for the effect of SDN sanctions on increases in offshore transactions in low v. high supervision groups.

Results and Discussion

Our theory predicts that targeted (SDN) sanctions may have an adverse effect in the long term by pushing co-national individuals or firms – those seeking the secrecy that comes with minimal international regulation – to obscure their transactions in low-supervision financial centers. We further predicted that sanctions would not increase new connections between origin countries and offshore jurisdictions with high levels of supervision, as entities are more likely to seek these better-monitored financial centers due to home-country-level push factors such as fears of asset seizure, high taxes, or volatility.

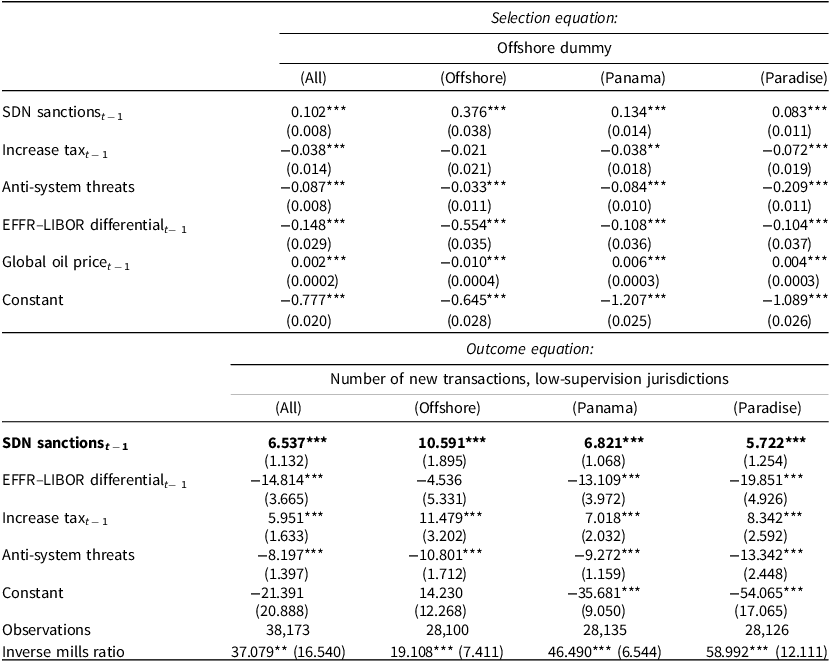

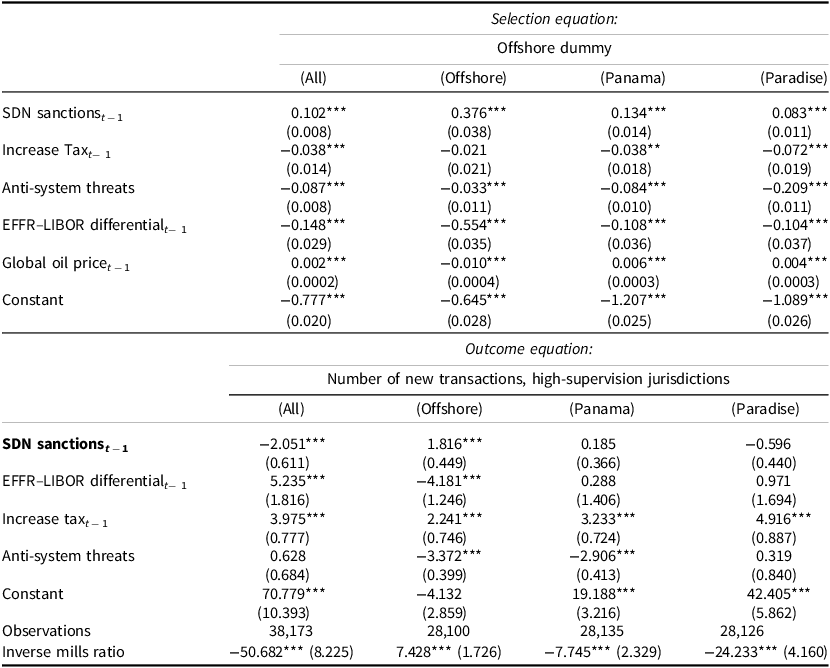

Tables 1 and 2 present the results of our two-stage models. Each table includes the selection and outcome equations, with the coefficients and statistical significance of SDN sanctions in the month prior (t - 1) in bold for ease of reading and interpretation. In each table, we include results for the full data (all ICIJ leaks/papers pooled together) as well as the Offshore Leaks, Panama Papers, and Paradise Papers as separate samples.Footnote 34

Table 1. SDN sanctions and new transactions in low-supervision jurisdictions

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

SDN: specially designated nationals

Table 2. SDN sanctions and new transactions in high-supervision jurisdictions

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

SDN: specially designated nationals

As Table 1 shows, when targeted sanctions are levied against their co-nationals, individuals or firms seeking the non-traceability of offshore finance are more likely to conduct transactions with financial jurisdictions that are poorly supervised. Jurisdictions in this category are described as ‘having a low quality of supervision, and/or being non-co-operative with onshore supervisors, and with little or no attempt being made to adhere to international standards’ or ‘having procedures for supervision and co-operation in place, but where actual performance falls below international standards and there is substantial room for improvement’ (Offshore Financial Centers. IMF Background Paper 2000). SDN sanctions in the month prior are a positive and statistically significant predictor of new offshore transactions into these jurisdictions across each of the data leaks. The increase in transactions reflects both firms’ and individuals’ initial movement of assets to risky offshore jurisdictions as a means of sanction-proofing and blacklisted entities’ attempts to further obscure the location and movement of their investments. This effect is consistent even as we control for the alternative explanations for capital flight to offshore jurisdictions discussed above.

As Table 2 indicates, SDN sanctions do not similarly increase financial movement into well-regulated and supervised offshore jurisdictions. Only in the Offshore Leaks, the earliest of the available leaks, is this effect positive and statistically significant. We offer two temporal and compatible explanations for this: that offshore financial jurisdictions had not yet specialized or marketed themselves as offering more supervision/secrecy or that the practice of sanction-proofing by moving assets to risky jurisdictions evolved as the efficacy of sanctioning increased. In all other samples, the effect of SDN sanctions on movement into high-supervision offshore jurisdictions is null or negative. While the imposition or threat of SDN sanctions provokes the movement of assets to low-supervision jurisdictions that are more difficult to monitor, there is no similar effect in high-supervision offshore jurisdictions.

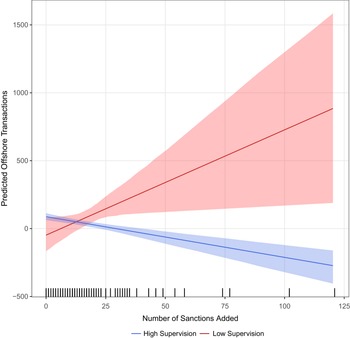

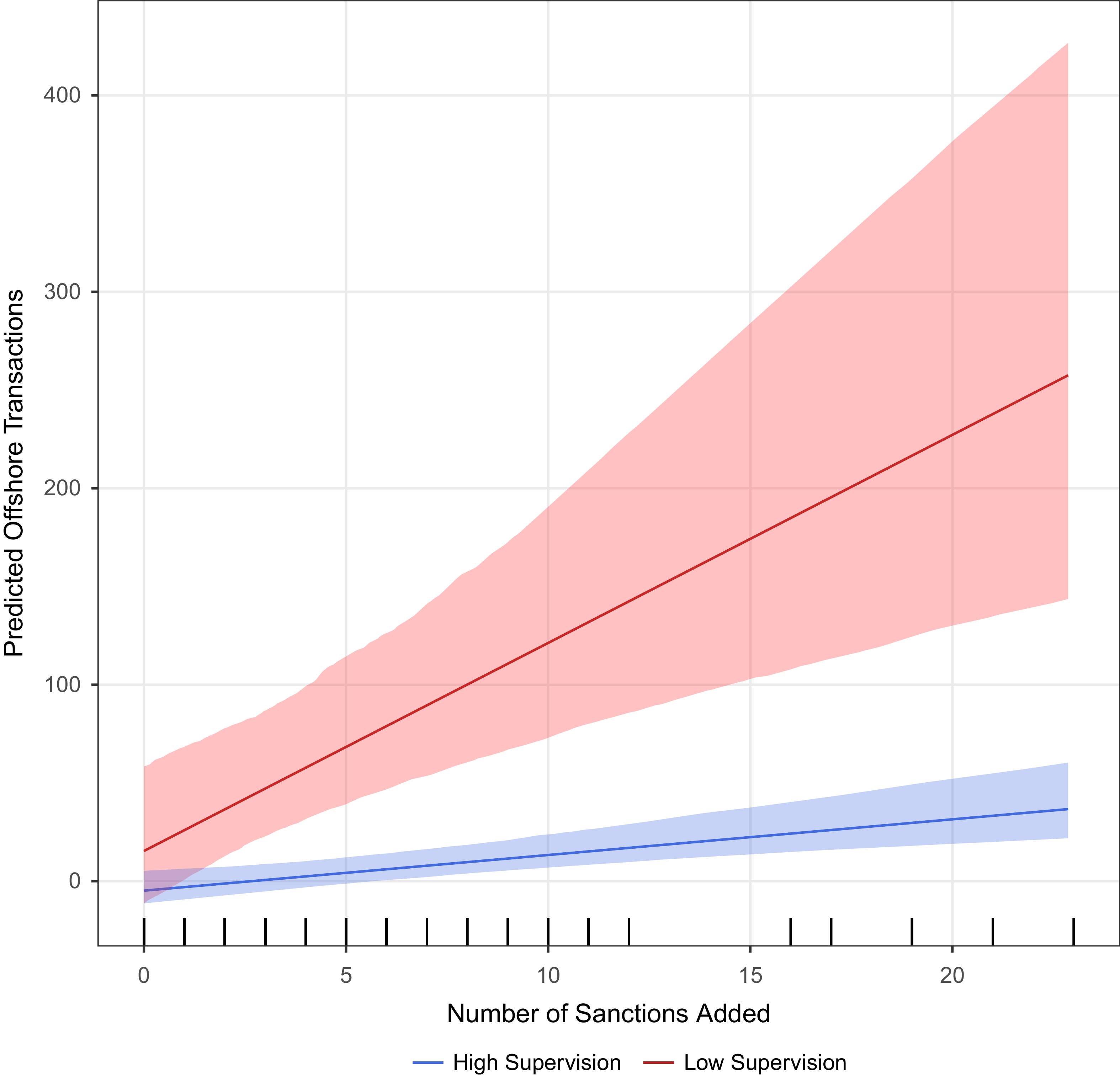

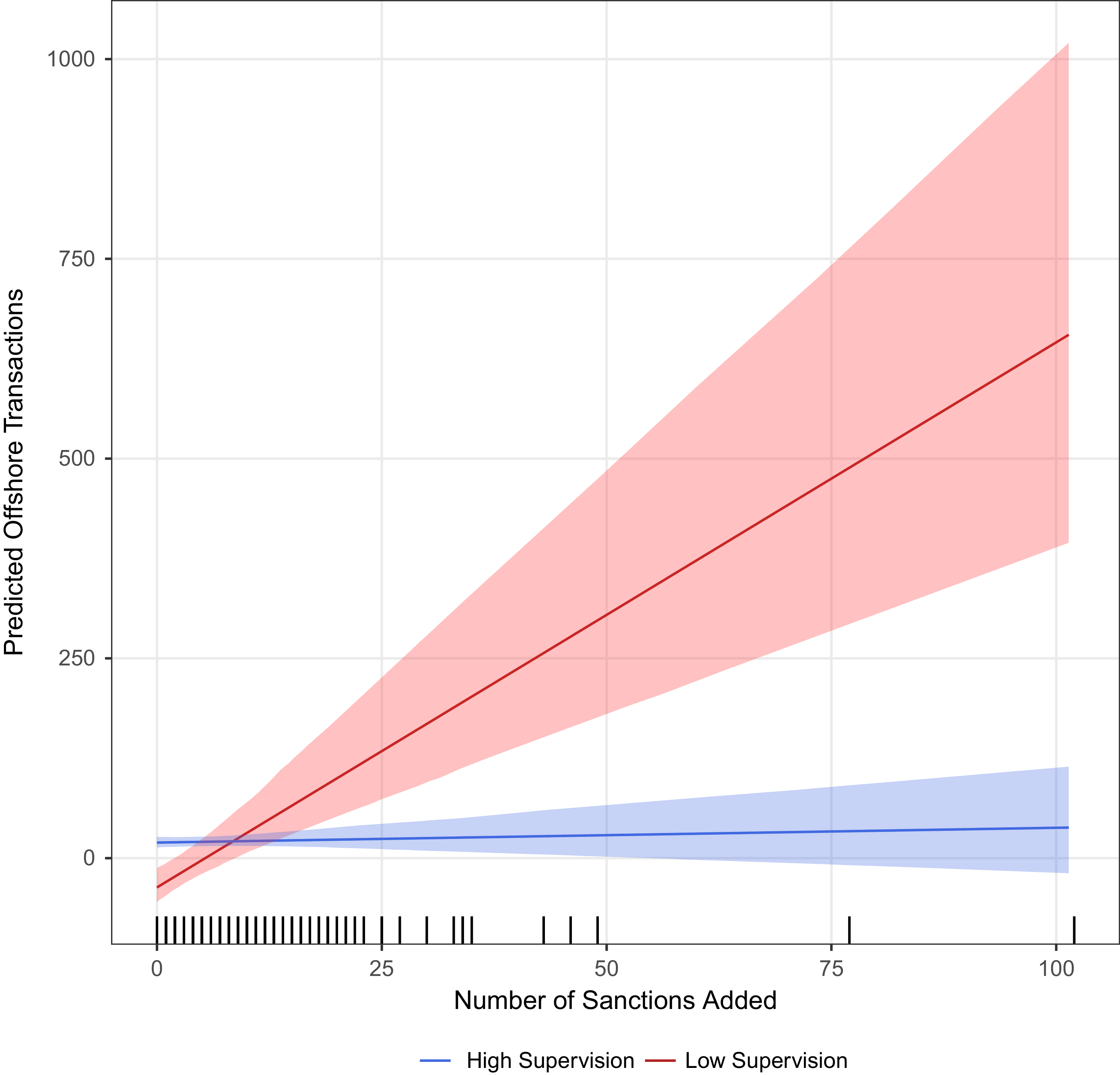

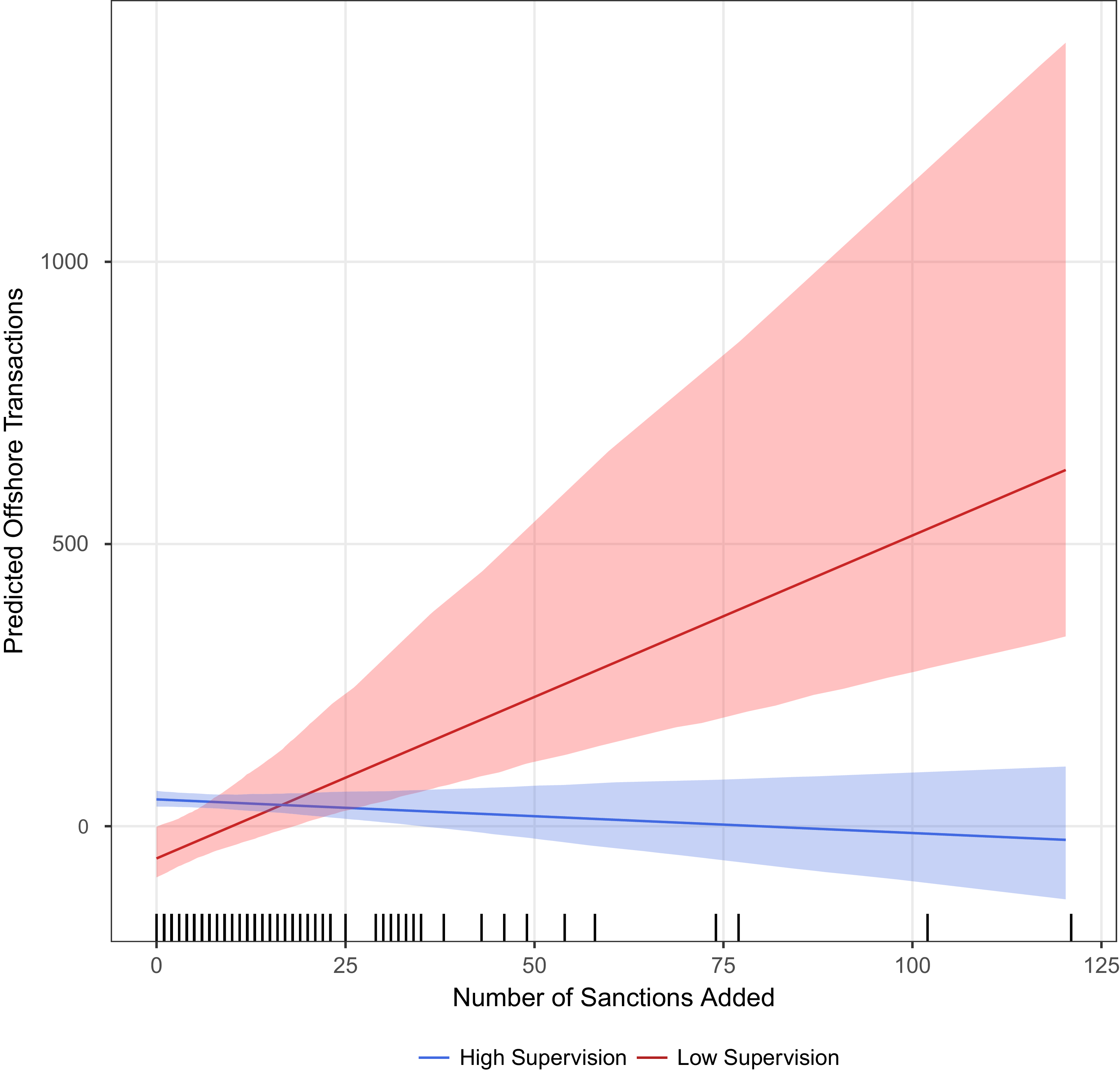

Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 illustrate the substantive implications of our findings. The range of the number of SDN sanctions applied in the month prior can be found on the x-axis, while the predicted number of offshore connections is on the y-axis.Footnote 35 Predicted values and bootstrapped 0.95 per cent confidence intervals for each group are shown (low supervision jurisdictions in red, high supervision in blue). The distribution of SDN sanctions for each sample (all data, Offshore, Panama, and Paradise) is also shown in a rug at the bottom of each plot. The majority of country-months experience very few sanctions, with a maximum of 121 in the full data. For the full, aggregated data and each of the samples, the predicted number of new transactions in low-supervision jurisdictions when sanctions have been applied is higher than the predicted number of high-supervision transactions. This effect increases and is significant over the observed range of sanctioning activity. Substantively, this means that sanctioning many entities within a month results in a high number of new transactions as blacklisted entities or concerned sanction-proofers within the same country move assets to poorly regulated, difficult-to-trace environments. Overall, our results and plots of predicted offshore connections by type of jurisdiction suggest that new SDN sanctions push blacklisted and sanction-proofing entities seeking secrecy to poorly supervised offshore financial jurisdictions, but this effect is not observed for well-supervised and monitored jurisdictions. When individuals or firms seek to avoid monitoring and punitive international action, the inherent risk of moving assets to a poorly regulated offshore jurisdiction becomes a positive draw.

Figure 1. Predicted offshore transactions and SDN sanctions, all data.

Figure 2. Predicted offshore transactions and SDN sanctions, Offshore Leaks.

Figure 3. Predicted offshore transactions and SDN sanctions, Panama Papers.

Figure 4. Predicted offshore transactions and SDN sanctions, Paradise Papers.

Our variables capturing alternate explanations for moving offshore merit additional discussion. First, and most interestingly, our two home country push factors – increases in taxation and anti-system threats – are negatively associated with movement offshore, as shown in the first stage of our selection models. This runs counter to the expectation from previous literature. We encourage caution with the interpretation of these findings for several reasons. Missingness in either measure is unlikely to be at random. For the tax measure in particular, countries engaging in sudden or unexpected levels of financial asset seizure may not be reporting in a timely or consistent fashion. Likewise, expert consensus about anti-system threats may be most difficult to achieve for countries experiencing new sources of turmoil or without significant reported information. Beyond the consequences of missingness are concerns about whether these variables have a linear relationship with offshore movement and how our novel temporal unit of analysis may be obscuring a commonly found relationship. Specifically, our tax variable captures any increase in taxation (in keeping with the previous literature) regardless of baseline tax level or the degree of increase. Increases may not uniformly affect offshore financial movement, but accounting for relevant changes for each country or country type lies outside of the scope of this paper. For the anti-system threat variable, it may be that states facing the highest threat level are not the most likely to experience capital flight offshore. Our paper highlights an opportunity to consider which types and what degree of threats provoke such movement and what does not. Lastly, both of these variables are coded at the yearly level while our dependent variable is monthly movement to different types of jurisdictions. It is unclear how long it takes changes in taxation or threats to the state to provoke movement of capital. For example, is the year prior too distant, indicating that the months in between may see a positive association although the year does not? Each of these factors – missingness, uncertainty about linearity and magnitude, and temporal mismatch – offer opportunities for further exploration into the dynamics of movement to different offshore jurisdictions.Footnote 36

The direction of our variables designed to capture access to the US dollar and oil prices are as anticipated. A higher spread between EFFR and LIBOR is negatively associated with offshore activity, but there is no difference between low- and high-supervision jurisdictions as both increase access to the US dollar. Similarly, higher oil prices correspond to an increase in offshoring of assets but with no strong preference for low- or high-supervision jurisdictions. The comparatively small effect of these variables (specifically, global oil price) raises an opportunity to reconsider an important distinction about the ICIJ data. These data capture increases in the number of transactions to different offshore jurisdictions but do not advance our understanding of the volume of offshore financial flows. When global oil prices increase, investors should increase the volume of their financial flow to OFCs rather than inefficiently creating new shell companies. On the contrary, when the impetus for moving money offshore is an increase in targeted sanctions, new shell companies/new transactions create additional layers of obscurity and therefore security. This distinction highlights an important area for additional future research on the drivers of increased financial flows v. numbers of transactions.

Conclusion and Future Research

Financial globalization has reshaped the international economic landscape, facilitating the free flow of capital across borders. However, this liberalization has also spurred the growth of offshore financial centers (OFCs), creating challenges for governments in distinguishing between legal and illicit financial activities. While OFCs provide legitimate services for investors seeking tax efficiency and asset protection, they also offer a veil of anonymity for illicit actors. Consequently, governments find themselves in a duality where they continue to encourage the free flow of capital, including via OFCs, while also intensifying monitoring and enforcement to differentiate between legal and illegal activities. Secrecy-seeking actors, in turn, continuously adapt to maintain anonymity.

In this paper, we argue that this hide-and-seek dynamic between governments and secrecy-seeking actors has systemic consequences for the global financial landscape. We specifically examine this dynamic in the context of US targeted sanctions and demonstrate a connection between the imposition of targeted sanctions and a subsequent surge in demand for services provided by OFCs characterized by weak regulation, limited transparency, and a reluctance to co-operate with international efforts against financial crimes.

We only find a consistent positive relationship between increased US monitoring and enforcement (targeted sanctions) and new offshore transactions with low-supervision jurisdictions where the paper trail is easily obscured. On the other hand, the movement of assets to well-regulated offshore locales is better predicted by economic push factors in the actors’ home countries. Different motivations for using offshore financial services influence the evolution of the offshore market and international finance more broadly. However, observing actors’ motivations – whether legal or criminal, profit-driven or politically motivated – is particularly challenging in this environment of restricted information. This paper takes a step towards assessing the impact of various demands for offshore services by focusing on the effect of targeted sanctions on the distribution of offshore transactions in aggregate.

These findings illustrate the underlying tension between financial liberalization and financial crime. They also underscore the irony that governments’ very efforts to monitor global finance inadvertently drive actors into greater anonymity. In the context of US sanctions, our research reveals an interesting unintended and counterproductive consequence of international financial regulation: efforts to enforce targeted sanctions in the short term can undermine the long-term efficacy of sanctions as a foreign policy tool. OFCs prove invaluable for targeted individuals and entities to evade sanctions, allowing them to pursue their lucrative transactions while under sanctions. Furthermore, our findings illustrate an intriguing dynamic where sanctions push co-nationals – individuals and entities from the same country as those targeted with US sanctions – into anonymity. This trend can weaken the effectiveness of US sanction programs over time and significantly complicate the monitoring of global finance.

Our findings complement the literature on the unintended consequences of economic sanctions by exploring the systemic effects of targeted sanctions on global financial flows. Parallel to the findings on how sanctions push domestic economies into the shadow economy (Andreas Reference Andreas2005; Early and Peksen Reference Early and Peksen2019), we demonstrate that targeted sanctions push individuals and firms to low-regulation offshore financial centers. These unintended consequences of targeted sanctions have two important implications for future research. First, our findings suggest the potential for financial losses in high-regulation offshore centers or onshore financial businesses as global sanction regimes expand. Second, and relatedly, they raise an intriguing puzzle about the long-term impact on regulatory frameworks in offshore financial centers. As sanction regimes and international monitoring efforts intensify, offshore financial centers may respond by relaxing regulations to attract resources from sanctioned countries, setting the stage for a potential ‘race to the bottom’ dynamic.

This dynamic underscores the importance of international co-operation and regulatory co-ordination in combating illicit financial activities and sanction evasion. Without the partnership of jurisdictions most attractive to actors seeking secrecy, monitoring and enforcement efforts will always be undermined. Moreover, our results contribute to the literature on sanction effectiveness, emphasizing the need to sanction not only actors directly linked to the policies sanctions aim to change but also the intermediaries and enablers of evasion (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Harrington, Fu and Rockmore2023).

Our work is not without its limitations, and discussing them can also offer avenues for future research. First, while we present a theoretical framework that broadly addresses the tension between financial liberalization and criminalization, our hypotheses are tested with a focus on US targeted sanctions and their monitoring and enforcement via OFAC. Although the US is the most prolific user of economic sanctions, we cannot claim that our findings apply to other senders of economic sanctions, such as the European Union or the United Nations.

Similarly, our work explicitly theorizes about and analyzes targeted sanctions imposed by adding individuals and entities to the SDN list maintained by OFAC. We do not make claims about other forms of sanctions, such as trade sanctions or more comprehensive sanctions. Future research could explore the impact sanctions have on the demand for offshore finance with a focus on EU sanctions or examine variations in sanction characteristics, such as their type or the costs they impose on the targeted country.

Another note of caution stems from to the nature of our data and modeling process. First, these data are leaks – although they are comprehensive, we cannot claim they represent the population of offshore financial transactions a truly random sample would. Although this problem plagues most data collection in international relations,Footnote 37 we suggest that future research should also consider the process of selection into the ICIJ dataset. Second, our interest is in global monitoring and subsequent patterns of movement into low- or high-supervision OFCs. This means that we aggregate transaction information to the country of origin level. While our work finds an association between increases in SDN sanctions and the flow of transactions to low-supervision OFCs, future research should investigate each transaction to identify if and when different types of actors (for example blacklisted v. sanction-proofing v. others) move offshore.

Despite its limitations, the ICIJ offshore data offers invaluable opportunities to test the scope conditions of existing theories in both international political economy and conflict or security studies. For instance, research on sanction effectiveness and international co-operation around sanctions policies prompts questions about effective monitoring and money laundering via offshore transactions. Studies on competition for FDI and attracting investors shed light on the patterns in tax haven attractiveness. Similarly, literature on terrorist group financing and the illicit economy informs our expectations about when violent groups can finance themselves via offshore centers. In short, new scholarship in political science and international relations scholarship is crucial for understanding the proliferation and importance of offshore financial centers and networks, which have largely been examined from an economics perspective. This paper not only demonstrates the connection between US targeted sanctions and offshore financial transactions but also aims to galvanize the discipline towards this new research agenda.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101087.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HM2UAJ.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants of the Perry World House Seminar Series at the University of Pennsylvania (October 2021), the University of North Carolina International Relations Brownbag (November 2021), the International Studies Association’s 2022 Workshop on the Politics of Offshore Finance, and the 2019 Annual Meeting of PolNet for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this paper. We also thank Cristina Bodea (Executive Editor of BJPS), four anonymous reviewers, Navin Bapat, Tobias Heinrich, Will Winecoff, Timothy Peterson, Alex Parets, Devin Case-Ruchala, and Tyler Ditmore for their helpful comments and guidance. Finally, we are grateful to Isabel Wallace for her excellent research assistance.

Author contribution

Authors listed in alphabetical order; equal contribution given.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None to disclose.