1 Introduction

How does one compare the latest large language models (LLMs) to prior methods for text-as-data applications where political science domain knowledge is well developed and important? Choosing the appropriate tool for the extraction and classification of relevant information from large and often unstructured corpora is a contemporary and ongoing challenge. As social (political) scientists, we possess replicable and encoded domain expertise to understand texts in our field and apply appropriate methods for our tasks (either with humans, text-as-data, natural language processing (NLP), or other methods). How then should one combine the insights of domain experts and computational scientists to evaluate which models are useful for extracting the domain information across various tasks with attention to accuracy, cost, and other metrics of interest? Should we use simpler information extraction tools or newer, generative, and more costly LLMs? To answer these questions, we compare ConfliBERT (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022), our domain-specific, extractive encoder model, to a selection of more recent generative LLMs. We examine different political science text-as-data applications, such as event extraction, classification, and named entity recognition (NER), with comparisons in terms of accuracy, processing speed, and other performance metrics. Through these analyses, we gain an understanding of the capabilities of longer-established extractive NLP tools versus more recent generative models.

An area of focus with significant application and domain expertise is conflict event data coded from news reports. The transformation of news texts into structured “who-did-what-to-whom” event data is fundamental in international relations and studies of conflict and political violence. The process of gathering and preparing data for analysis in this domain is to assemble a corpus, filter for relevant information, identify target events, and annotate event attributes. This process can be costly and time-consuming: time required for data collection, structuring and filtering large amounts of text, training human annotators to apply the event ontology, and several rounds of quality controls to ultimately achieve a curated text corpus. This approach parallels the widely systematized way to process text-as-data in much of international relations and the social sciences (Croicu and Eck Reference Croicu and Eck2022; Grimmer, Roberts, and Stewart Reference Grimmer, Roberts and Stewart2022; O’Connor, Stewart, and Smith Reference O’Connor, Stewart and Smith2013). Ultimately, the purpose is to extract relevant information on source actors (who), actions (did what), targets and actors (to whom), and other attributes for political science research.

Although computational methods have been used to analyze political texts for decades (Gerner et al. Reference Gerner, Schrodt, Francisco and Weddle1994), tools for these tasks have developed rapidly with the advent of LLMs. Models that were commonly used include extractive LLMs that can be trained specifically for classification, NER, and to annotate other features of the text. This is the focus of models like BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT, ELECTRA, and ConfliBERT, which are all variously sized (layered) encoder neural network models. More recently, this also includes generative LLMs that both encode the original text and provide a decoder to summarize the output features of interest, the generative output from a prompt. This includes many of the now familiar LLMs like Gemma, Llama, Qwen, ChatGPT, etc. In this research, we compare these extractive and generative types of LLMs for common text analysis tasks. The focus is not on a comparison across BERT-alike models, but on a domain-specific, fine-tuned BERT model (ConfliBERT) to more recent generative LLMs.

We make three significant contributions. First, compared to recent generative LLMs, ConfliBERT has superior performance based on classification metrics (AUC,

![]() $F_1$

, etc.) applied to multiple datasets (BBC, Global Terrorism Database [GTD], and re3d) and tasks (binary and multi-class classifications and NER). Specifically, ConfliBERT outperforms Meta’s Llama 3.1 (Dubey et al. Reference Dubey2024), Google’s Gemma 2 (Team Gemma et al. 2024), and Alibaba’s Qwen 2.5 (Hui et al. Reference Hui2024) in relevant tasks. These results show that fine-tuned models used to extract political conflict information from domain-relevant texts can outperform the more general models in terms of accuracy, precision, and recall. This is consistent with prior work from Hürriyetoğlu et al. (Reference Hürriyetoğlu and Hürriyetoğlu2021), Kent and Krumbiegel (Reference Kent and Krumbiegel2021), Ollion et al. (Reference Ollion, Shen, Macanovic and Chatelain2023), Wang (Reference Wang2024), and Croicu and von der Maase (Reference Croicu and von der Maase2025). Second, ConfliBERT is hundreds of times faster than generative LLMs at identical tasks. This time savings is important when processing hundreds of thousands or millions of documents, as is often the case for large-scale event coding projects like Georeferenced Event Data or Militarized Interstate Dispute (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer2022; Sundberg and Melander Reference Sundberg and Melander2013). The savings is amplified when used for active learning, iterative coding, and additional rounds of fine-tuning. Third, ConfliBERT models are open and extensible, so these results align with other recent and related political science work and developing standards (Barrie, Palmer, and Spirling Reference Barrie, Palmer and Spirling2024; Burnham et al. Reference Burnham, Kahn, Wang and Peng2024).Footnote

1

We ran the generative LLMs locally using the Ollama backend, a framework that provides the instruction-tuned model variants that are standard for task-based research, not the raw base models. For efficiency, these models were deployed with 4-bit quantization, a common practice that explains the low memory footprint in our results while representing a typical trade-off between performance and computational cost. This setup ensures our comparison is against LLMs as they are practically applied by researchers.

$F_1$

, etc.) applied to multiple datasets (BBC, Global Terrorism Database [GTD], and re3d) and tasks (binary and multi-class classifications and NER). Specifically, ConfliBERT outperforms Meta’s Llama 3.1 (Dubey et al. Reference Dubey2024), Google’s Gemma 2 (Team Gemma et al. 2024), and Alibaba’s Qwen 2.5 (Hui et al. Reference Hui2024) in relevant tasks. These results show that fine-tuned models used to extract political conflict information from domain-relevant texts can outperform the more general models in terms of accuracy, precision, and recall. This is consistent with prior work from Hürriyetoğlu et al. (Reference Hürriyetoğlu and Hürriyetoğlu2021), Kent and Krumbiegel (Reference Kent and Krumbiegel2021), Ollion et al. (Reference Ollion, Shen, Macanovic and Chatelain2023), Wang (Reference Wang2024), and Croicu and von der Maase (Reference Croicu and von der Maase2025). Second, ConfliBERT is hundreds of times faster than generative LLMs at identical tasks. This time savings is important when processing hundreds of thousands or millions of documents, as is often the case for large-scale event coding projects like Georeferenced Event Data or Militarized Interstate Dispute (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer2022; Sundberg and Melander Reference Sundberg and Melander2013). The savings is amplified when used for active learning, iterative coding, and additional rounds of fine-tuning. Third, ConfliBERT models are open and extensible, so these results align with other recent and related political science work and developing standards (Barrie, Palmer, and Spirling Reference Barrie, Palmer and Spirling2024; Burnham et al. Reference Burnham, Kahn, Wang and Peng2024).Footnote

1

We ran the generative LLMs locally using the Ollama backend, a framework that provides the instruction-tuned model variants that are standard for task-based research, not the raw base models. For efficiency, these models were deployed with 4-bit quantization, a common practice that explains the low memory footprint in our results while representing a typical trade-off between performance and computational cost. This setup ensures our comparison is against LLMs as they are practically applied by researchers.

We begin with a short review of ConfliBERT, a domain-specific, pre-trained, and then fine-tuned model for the analysis of conflict texts. We then discuss how this model can be compared to newer, larger LLMs that are generative and thus more costly in terms of computational time and initial resource setup. Finally, we discuss and present the relative performance of the various models.

2 ConfliBERT as an Extractive Domain Tool

For political science applications, we want to use a tool like ConfliBERT to accomplish three key information extraction and summarization tasks that are part of “coding event data”: 1) filtering politically relevant information in a corpus, 2) identifying events, and 3) encoding their attributes. The first is well-solved in multiple ways using tools such as support vector machines, topic models, or dictionary-based methods (Beieler et al. Reference Beieler, Brandt, Halterman, Simpson, Schrodt and Alvarez2016). The second, event identification, is crucial to create valid and reliable event datasets. These form the backbone of many quantitative analyses in the field. But this identification often requires iterations and revisions, requiring speed and computational efficiency as well as accuracy. Perhaps the most challenging aspect in this text processing is the third—the detailed annotation of event attributes. This is the “who,” “what,” “to whom,” “where,” and “when” of each identified event. This requires not just NER, but also understanding the roles these entities play in the event and the relationships between them.

Transformer architectures and LLMs show considerable promise across these event coding and text analysis tasks. For example, Parolin (Reference Parolin, Hu, Khan, Osorio, Brandt and D’Orazio2021), Parolin et al. (Reference Parolin, Khan, Osorio, Brandt, D’Orazio and Holmes2021), and Parolin et al. (Reference Parolin2022) explore the use of general (non-domain specific) Transformer models for cross-lingual, multi-label, and multi-task classifications in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Base models, such as pre-trained BERT, were incorporated, adapted, and extended for different event coding tasks by changing the attention layers and recalibrating the parameters (Parolin et al. Reference Parolin, Khan, Osorio, Brandt, D’Orazio and Holmes2021). These innovations led to improvements in the accuracy, precision, recall, and

![]() $F_1$

of the classifications over original BERT and RoBERTa models across languages (Parolin et al. Reference Parolin, Khan, Osorio, Brandt, D’Orazio and Holmes2021, Table III).

$F_1$

of the classifications over original BERT and RoBERTa models across languages (Parolin et al. Reference Parolin, Khan, Osorio, Brandt, D’Orazio and Holmes2021, Table III).

We address how the filtering and extraction of annotations for conflict reports can be done with ConfliBERT, a domain-specific model that we pre-trained using the BERT architecture.Footnote 2 Unlike BERT and the many other general-purpose LLMs pre-trained on all sorts of text data, ConfliBERT is pre-trained with domain-specific texts about political conflict, violence, and international relations.Footnote 3 Our curated corpus of 33.7 GB of text consists of an expert domain corpus and a mainstream media corpus. The expert domain corpus (2,293 MB) contains political conflict texts and professional sources related to diplomacy, such as the United Nations, intergovernmental organizations (INGOs), think tanks, and government agencies. The mainstream media corpus contains the (a) Mainstream Media Collection (MMC) (20 GB), a corpus collected from 35 news agencies worldwide, (b) Gigaworld corpus (8,818 MB), which includes media coverage from seven international English newswires from 1994 to 2010,Footnote 4 (c) Phoenix Real-Time (PRT) event dataset (2,425 MB), which combines data from over 400 news agencies worldwide, and (d) Wikipedia’s political events articles (2,845 MB), which were extracted from the 2021 Wikipedia dump (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022). To remove texts unrelated to our domain, documents were filtered for relevance where appropriate.

ConfliBERT has previously been shown to perform better than BERT models (cased and uncased) based on macro

![]() $F_1$

statistics 1) across training set sizes (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022, Figure 2) and 2) across relevant tasks in multiple test datasets related to political conflict and violence—such as 20News, GLOCON, GTD, SATP, InsightCrime, India Police Events, CAMEO codebook examples, MUC-4, and re3d—which are used across political science, national security, and NLP comparisons. Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022, Table 3 and Figure 1) establish ConfliBERT’s superiority against a baseline of BERT (Devlin et al. Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2018) for these datasets. For binary classification (BC) and NER, ConfliBERT was better than BERT (based on using cased and uncased models) using

$F_1$

statistics 1) across training set sizes (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022, Figure 2) and 2) across relevant tasks in multiple test datasets related to political conflict and violence—such as 20News, GLOCON, GTD, SATP, InsightCrime, India Police Events, CAMEO codebook examples, MUC-4, and re3d—which are used across political science, national security, and NLP comparisons. Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022, Table 3 and Figure 1) establish ConfliBERT’s superiority against a baseline of BERT (Devlin et al. Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2018) for these datasets. For binary classification (BC) and NER, ConfliBERT was better than BERT (based on using cased and uncased models) using

![]() $F_1$

and macro

$F_1$

and macro

![]() $F_1$

statistics for weighted precision and recall.Footnote

5

$F_1$

statistics for weighted precision and recall.Footnote

5

The performance of ConfliBERT has been validated and independently established by 1) Häffner et al. (Reference Häffner, Hofer, Nagl and Walterskirchen2023) who find it superior to dictionary-based classifiers for conflict prediction, 2) the complete fine-tuning of the ConfliBERT model by Wang (Reference Wang2024) for similar tasks, 3) Croicu (Reference Croicu2024) give additional and independent evidence of the model’s strong performance relative to known alternatives for different conflict texts and related tasks, and 4) Croicu and von der Maase (Reference Croicu and von der Maase2025) use of the model as part of a classification pipeline for a refined version of the UCDP GED data.

ConfliBERT builds on insights from the NLP literature and introduces 1) domain-specific pre-training, 2) fine-tuning training corpora from the conflict/political science domain, and 3) specific downstream tasks, such as BC, multi-label classification, and NER. It uses a transformer language model architecture and large amounts of politically relevant news texts as training data (Devlin et al. Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2018). Similar to BERT, the pre-trained models minimize loss on masked token prediction, next sentence prediction, or both tasks. The pre-training for these models is either continuous or from scratch. Continuous means that it uses weights from another LLM as the starting point and tunes by minimizing loss on our domain corpus. Scratch means that we do not begin with the pre-learned weights, so learning only from the domain corpus.

We re-cast the problems of the political science domain into those more commonly seen in the information and computer science domains of NLP and inferences. This trades human annotation and classification costs for computational resources, which grow more powerful and cheaper. However, we need to bridge the way social scientists think about information extraction with how computational linguists and information scientists think about information extraction. Specifically, they focus on labeling spans of text corresponding to linguistic or contextual entities. In contrast, we focus on event attributes, their modality, and characteristics (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Simon, Velldal, Øvrelid, Hürriyetoğlu, Tanev, Thapa and Uludoğan2024). As a domain-specific, pre-trained LLM, ConfliBERT can help identify and categorize key features of political events from text without a fully specified ontology of actors or their interactions. These ontologies are required for dictionary-based approaches (Boschee et al. Reference Boschee, Lautenschlager, O’Brien, Shellman, Starz and Ward2015).

Similar domain-specific BERT models have been shown to outperform generic BERT models in other scientific fields, such as biomedical (SCIBERT, Beltagy, Lo, and Cohan Reference Beltagy, Lo and Cohan2019), material sciences (MatSCIBERT, Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Mohd Zaki, Krishnan and Mausam2022), legal (LegalBERT, Chalkidis et al. Reference Chalkidis, Fergadiotis, Malakasiotis, Aletras and Androutsopoulos2020), finance (FinBERT, Araci Reference Araci2019), clinical notes (ClinicalBERT, Huang, Altosaar, and Ranganath Reference Huang, Altosaar and Ranganath2020), and patent texts (patentBERT, Lee and Hsiang Reference Lee and Hsiang2019). The benefits of the domain-specific approach of ConfliBERT extend to other languages as well. Recent extensions of the English language ConfliBERT model to ConfliBERT-Spanish (Yang et al. Reference Yang2023) and ConfliBERT-Arabic (Alsarra et al. Reference Alsarra2023) address the lack of non-English trained LLMs and permit the use of ConfliBERT’s classification abilities to these two additional languages. Both are political conflict domain-specific LLMs without machine translations to English. Yang et al. (Reference Yang2023) pre-train and fine-tune ConfliBERT Spanish.Footnote 6 Compared to two Spanish-based models, mBERT and BETO—in all three tasks NER, binary, and multi-class classification—ConfliBERT Spanish outperformed the generic Spanish language models (Yang et al. Reference Yang2023, Table II). Alsarra et al. (Reference Alsarra2023) introduce the same approach in ConfliBERT Arabic, a language-specific LLM that outperform competing models in the majority of cases on Arabic datasets that contained political, conflict-related, and international content (Alsarra et al. Reference Alsarra2023, see Tables 3 and 4).Footnote 7 On datasets that did not primarily contain these specific topics, regular BERT models performed better than ConfliBERT Arabic. Its non-English variants, ConfliBERT-Spanish outperforms BERT variants like mBERT and BETO (Yang et al. Reference Yang2023); and, ConfliBERT-Arabic does the same relative to AraBERT (Osorio et al. Reference Osorio2024).

3 The Event Coding Problem

In conflict event data research, scholars break down texts into key attributes: actors (sources and targets), actions, locations, and dates.Footnote 8 With actor coding, there are two broad approaches that, with the exception of training data, eschew human coding: mining past data to propose new groups or categories of actors (Solaimani et al. Reference Solaimani, Salam, Khan, Brandt and D’Orazio2017b) and machine learning or transformer approaches using BERT-based and other models (Alsarra et al. Reference Alsarra2023; Dai, Radford, and Halterman Reference Dai, Radford and Halterman2022; Halterman et al. Reference Halterman, Bagozzi, Beger, Schrodt and Scarborough2023; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022; Parolin et al. Reference Parolin2022; Yang et al. Reference Yang2023). Prior work codes actions using sparse parsing with human-annotated dictionaries (Osorio et al. Reference Osorio, Reyes, Beltrán and Ahmadzai2020; Schrodt Reference Schrodt2001), whereas newer approaches handle new ontology or action extensions through up-sampling (Halterman and Radford Reference Halterman and Radford2021), natural language inference (NLI) (Croicu Reference Croicu2024; Dai et al. Reference Dai, Radford and Halterman2022; Halterman et al. Reference Halterman, Bagozzi, Beger, Schrodt and Scarborough2023; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022; Lefebvre and Stoehr Reference Lefebvre and Stoehr2023; Parolin et al. Reference Parolin2022), or zero-shot (ZS) prompts (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Parolin, Khan, Osorio, D’Orazio, Ku, Martins and Srikumar2024). Geographic coding in earlier work relied on the location inferred from the actors to identify where the event occurred. Some approaches to determine location use sparse parsing (Osorio et al. Reference Osorio, Reyes, Beltrán and Ahmadzai2020), word embedding and NER (Halterman Reference Halterman2017; Imani et al. Reference Imani, Chandra, Ma, Khan and Thuraisingham2017; Imani, Khan, and Thuraisingham Reference Imani, Khan and Thuraisingham2019, e.g.,), and even BERT (Halterman et al. Reference Halterman, Schrodt, Beger, Bagozzi and Scarborough2023). For date or time coding of events, researchers generally parse the byline of the news report to acquire the publication date (Osorio et al. Reference Osorio, Reyes, Beltrán and Ahmadzai2020), but the publication and the event occurrence dates are not always the same. A recent approach is to apply BERT technology to extract date information from the news story (Halterman et al. Reference Halterman, Schrodt, Beger, Bagozzi and Scarborough2023). All of these information extraction approaches are prone to various errors (Brandt and Sianan Reference Brandt and Sianan2025), and the latest methods attempt to reduce them using BERT-alike language models.

ConfliBERT provides a domain-level solution to these coding tasks. For most generative and extractive tasks, an LLM needs broad pre-training. These training steps generate huge costs in terms of 1) training data and its acquisition, 2) human/expert time, and 3) computational complexity to combine and produce the relevant model. In a domain-specific application, several choices make these challenges much more feasible for a social science tool like ConfliBERT. First, creating an extractive LLM or a BERT LLM (or even, for that matter, a simple predictive or generative suggestion model) can be done much more rapidly and cheaply. Since there is domain knowledge and insight provided in the initial training steps, steps 1 and 2 above for training a generic LLM are greatly scaled back, resulting in a superior model in a shorter period of time. Second, ConfliBERT can then be augmented or expanded (which we demonstrate below) to focus on harder tasks, such as ontology extension (Radford Reference Radford2021), actor detection and recognition (Solaimani et al. Reference Solaimani, Salam, Khan, Brandt, D’Orazio, Lee, Lin, Osgood and Thomson2017a, Reference Solaimani, Salam, Khan, Brandt and D’Oraziob), and image processing applications (Steinert-Threlkeld Reference Steinert-Threlkeld2019; Wen et al. Reference Wen, Sil and Lin2021).

The extraction of actors, action events (verbs), and additional information from texts for political science and international relations studies of conflict are accommodated in three different NLP tasks. The three main tasks that ConfliBERT addresses are:

-

Classification Which texts contain relevant information about politics, conflict, and violence? We give examples of this below based on data from the BBC and re3d text corpora. These are:

-

1. binary classifications: yes/no questions;

-

2. multi-label classifications: in a series of reports about protests, which types of protest are present (labor, peaceful, violent, etc.)?

-

-

Named Entity Recognition What are the “who” and “whom” that characterize the event? These are most typically the linguistic subjects and objects of the sentences and clauses, subject to textual disambiguation and co-referencing. But making sense of them becomes a task for a political scientist to identify the source/initiator of a political event toward a target or other political actor. We give an example below using texts about terrorist attacks from the GTD. We use NER to identify both traditional entities (Persons and Locations) and event-specific roles (Victims and Perpetrator Organizations). This approach is sometimes referred to as role-aware NER or event argument extraction and shares similarities with semantic role labeling. For this study, we train a single NER model to identify all entity types. We acknowledge that a more complex approach could involve training distinct models for each event type to resolve role ambiguities (e.g., an entity as a “victim” in one event and an “accuser” in another), an avenue we leave for future work.

-

Masking/Coding new entities and/or events is the extension of any ontology of new kinds of events. This can include teaching a model which events are new ones, ones to be excluded, or newly emergent actors and their roles.

The first two of these tasks may be viewed as a supervised learning problem and handled with statistical or machine learning algorithms. In this setting, the model is trained to learn and predict patterns based on repeated past examples or interactions. For example, D’Orazio et al. (Reference D’Orazio, Landis, Palmer and Schrodt2014) use support vector machines to classify texts on international conflict. This and similar approaches rely heavily on training data and may have trouble predicting out-of-sample when new patterns and types of conflict emerge. ConfliBERT improves on previous approaches like this by using longer embedded patterns of related text and its ability to comprehend context. It is able to accomplish this in situations where 1) the events or entities to be classified are rare and there are few examples to learn from or 2) where there is a class imbalance and the event or entity is not necessarily rare, but there are few relative to more common ones.

The last task is harder, but can begin with an LLM or a BERT-like model. To determine whether an event is similar to a prior one (or a related class or actor), we can provide examples that omit the thing to be predicted (masking or hiding it) and then assess how well the model performs. This problem can apply to new actors and events and the determination of whether the model/coder is correct relies on the domain knowledge of the social scientist. Further, the identification of new actors is often a masking task for which BERT-alike models are designed.Footnote 9

These tasks could be done with extractive LLM models like ConfliBERT or could use newer generative models. The next section explores these choices and how they can be compared across several examples.

4 ConfliBERT Examples

ConfliBERT is an engine or baseline for extracting information about political texts. It 1) sorts political violence texts from other ones (classification), 2) identifies possible political actors and entities (since it was trained to do so and does NER with this knowledge), and 3) provides for masking and question and answer (QA) tasks for coding. Clearly, the process and methodology here can be adapted to use other methods beyond BERT (other options and more recent LLMs are explored below). It can then be extended in domain areas/expertise, as well as scope conditions to include new languages, etc., via masking, fine-tuning, or other extensions. In this section, we illustrate how these three main tasks can be accomplished by the model before turning to specific comparisons to other models in the next section.

An example of the first task is the BC of news articles to determine their relevance to gun violence. Using a dataset comprising BBC news articles and the 20 Newsgroups corpus, we trained ConfliBERT to discern whether a given news item pertains to gun violence incidents. This fine-tuning task is significant for both domestic and international conflict studies, since it shows how to filter rapidly large volumes of news data about something like gun violence-related events. The ability to quickly identify relevant articles from a diverse news corpus can significantly enhance researchers’ capacity to track and analyze (gun-related) conflicts in real-time.

For this BC task, ConfliBERT distinguishes between gun violence-related and non-gun violence-related incidents. Consider these examples:

Example 1 Input: “Two Lashkar e Jhangvi LeJ militants Asim alias Kapri and Ishaq alias Bobby confessed to killing four Rangers in Ittehad Town of Karachi, the provincial capital of Sindh.”

Output: Gun Violence Related (1)

Input: “More than a week after a woman Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-Maoist) cadre was killed in an encounter in the forests of Lanjigarh block in Kalahandi District, the Maoists identified her as Sangita and called a bandh (general shutdown) in two Districts in protest against the killing.”Output: Gun Violence Related (1)

The second task expands on this BC to a more nuanced multi-class classification of attack types. Employing the GTD to train ConfliBERT, it can classify attacks into nine distinct categories, including bombing/explosion, armed assault, assassination, and various forms of hostage-taking. Here are examples from the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) dataset:

Example 2 Input: “Islamic State (IS) in the latest issue of its online magazine Dabiq claimed that the five of the nine Gulshan café attackers were suicide fighters

![]() $\ldots $

The mujahidin held a number of hostages as they engaged in a gun battle with apostate Bengali police and succeeded in killing and injuring dozens of disbelievers before attaining shahadah.”

$\ldots $

The mujahidin held a number of hostages as they engaged in a gun battle with apostate Bengali police and succeeded in killing and injuring dozens of disbelievers before attaining shahadah.”

Output: Armed Assault

Input: “The ongoing construction work of an interstate bridge on Pranhita River on Maharashtra-Telangana border was thwarted by the Naxalites [Left Wing Extremists, LWEs] who set an excavator on fire and also damaged other equipment at the construction site at Gudem in Aheri taluka (revenue unit) of Gadchiroli District on April 26.”

Output: Facility/Infrastructure Attack

Input: “Three boys sustained injuries when a landmine went off in Atmar Khel area of Baizai tehsil (revenue unit) in Mohmand Agency of Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) on June 18.”

Output: Bombing/Explosion

The third task ConfliBERT addresses is NER, crucial for extracting structured information from unstructured text, enabling more detailed and systematic analyses of conflict actors and targets. Using event reports (from MUC-4), which contain annotations of terrorism events, we fine-tune ConfliBERT to identify and classify entities, such as Organizations, Physical Targets, Victims, and Individuals. Here is an NER classification example using text from SATP:

Example 3 Input: “A senior Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) [ORG] worker identified as Sohail Rasheed [PERSON], 30, was shot dead near his home in Naeemabad [LOC] in Korangi Town [LOC] of Karachi [LOC], the provincial capital of Sindh [LOC], on June 19 [DATE].”

Output:

Organization: Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM)

Victim: Sohail Rasheed Physical Target: Not specified

Location: Naeemabad, Korangi Town, Karachi, Sindh

Date: June 19

The versatility in these tasks suggests potential applications in fields, such as international relations, security studies, and public policy. Providing a tool that can simultaneously categorize events, identify key actors and targets, and filter relevant information from large text corpora, ConfliBERT offers a powerful means of analyzing the complex landscape of modern conflicts.

ConfliBERT was pre-trained in 2021 on data that at this point is nearly four years old (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022). So a question is, how well does it do with more contemporaneous events and data? Consider the following example that has been processed using the interface at https://eventdata.utdallas.edu/conflibert-gui/ or https://huggingface.co/spaces/eventdata-utd/ConfliBERT-Demo:Footnote 10

Example 4 Input: Former President Donald Trump, the 2024 presumptive Republican presidential nominee, was escorted off the stage by Secret Service after gunshots were fired at his rally in Butler, Pennsylvania. Mr. Trump was injured from the incident, with blood appearing on the right side of his face. This occurred two days before the start of the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee. The Butler County, Pennsylvania, district attorney told the Associated Press that a shooter was dead and a rally attendee was killed.

Output:

Organization: “secret service”, “republican national convention”, “the associated press”, “district”

Person: “former president donald trump, the 2024 presumptive republican presidential nominee”, “attorney”

Temporal: “two day”

Location: “butler, pennsylvania”, “milwaukee”, “butler county, pennsylvania”

The outputs for each of the coding tasks are:

-

Binary Classification for Political Violence “Positive: The text is related to conflict, violence, or politics (Confidence: 99.85%).”

-

Multilabel Classification “Armed Assault (Confidence: 98.40%)/Bombing or Explosion (Confidence: 5.39%)/Kidnapping (Confidence: 0.44%)/Other (Confidence: 0.95%).”

The only notable classification question is the placement of the “district attorney” as a person or organization. Such an error can easily be corrected with additional fine-tuning about legal actors and titles. This would then affect the comparability of later downstream performance metrics.

The scalability of this approach is particularly noteworthy. Once trained on these diverse tasks, ConfliBERT can be rapidly deployed to process large volumes of new data, enabling real-time or near-real-time analysis of emerging conflicts. This capability is invaluable for researchers and policymakers who need to quickly assess and respond to evolving conflict situations.

5 Evaluating ConfliBERT versus Other LLMs

The focus here is on ConfliBERT’s efficacy in the two critical NLP tasks of BC and NER compared to recent developments like generative AI LLMs. Gauging ConfliBERT’s comprehension and extraction of information from conflict-related texts can be benchmarked against more recently created baselines from much larger LLMs like Gemma 2, LLama 3.1, and Qwen 2.5. The goal is to assess the quality of an LLM like ConfliBERT and compare it to larger, more costly, and more computationally expensive alternatives.

We do this initially for two datasets that were used in the earlier comparisons of ConfliBERT to BERT: the BBC News Dataset and re3d.Footnote 11 The BBC News dataset is used for the BC task (Greene and Cunningham Reference Greene and Cunningham2006) and consists of 2,225 news articles, with 1,490 records for training and 735 for testing. The articles cover five categories: business, entertainment, politics, sport, and technology. For the conflict classification task, the dataset articles are relabeled as either conflict-related (1) or not conflict-related (0) by expert coders who analyzed each article’s content and context. The BBC News dataset provides a diverse range of news articles, thus testing ConfliBERT’s performance in sorting conflict-related content across various domains. The BC task mimics real-world scenarios where analysts must quickly identify political conflict-relevant information from a stream of news articles.

Once such articles or reports are identified via BC, political actor and action classification are the next relevant NER tasks. To compare ConfliBERT and more recent alternatives on this task, the re3d dataset is used (Relationship and Entity Extraction Evaluation Dataset https://github.com/dstl/re3d/). These data are specifically designed for defense and security intelligence analysis, focused on the conflict in Syria and Iraq, and providing domain-specific content across various source and document types with differing entity densities. The entities of interest include organizations, persons, locations, and temporal expressions. Ground-truth labels were established by annotators using a hybrid process.Footnote 12 The re3d dataset is valuable to evaluate ConfliBERT’s and LLMs’ extraction of relevant entities from conflict-related texts.

5.1 Methodology

Across the two datasets in this section, the performance of a task is done using versions of 1) ConfliBERT, 2) Meta’s Llama 3.1 (8B), 3) Google’s Gemma 2 (9B), and 4) ConflLlama (8B). Note that these are the most recent versions of these LLMs in mid-2024. To run the generative LLMs, we utilized the Ollama platform, which facilitates local model inference. This framework ensures that we are using the instruction-tuned variants of the models by default, which is the standard and appropriate choice for task-based applications like classification and NER. For computational efficiency on standard research hardware, Ollama deploys these models with 4-bit quantization. This practical choice significantly reduces memory usage but may also impact model precision. This methodological setup allows for a multi-faceted comparison. We evaluate our domain-specific, supervised extractive model (ConfliBERT) against:

-

• State-of-the-art generative LLMs used in a zero-shot capacity (Llama 3.1 and Gemma 2), reflecting a common and accessible workflow for researchers.

-

• A generative LLM that has also undergone supervised, domain-specific fine-tuning (ConfLlama), helping to distinguish the effects of model architecture versus training paradigm.

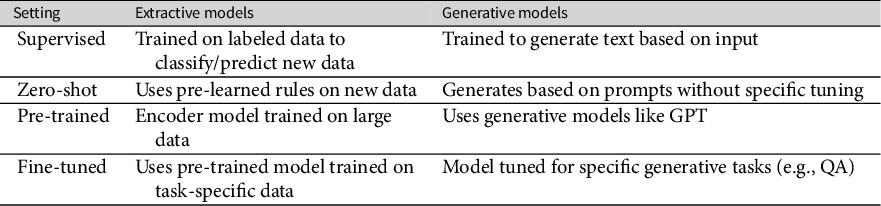

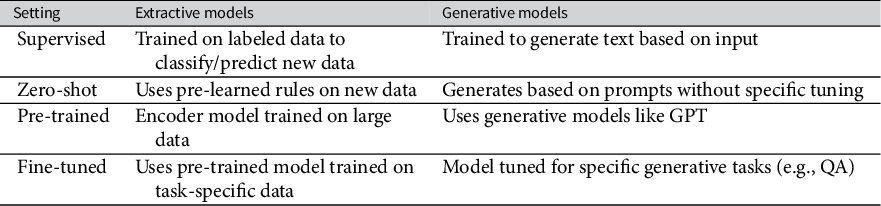

The comparisons conducted within the scope of this article therefore assess ConfliBERT’s performance against both readily accessible LLMs and a more tailored generative counterpart. A general comparison of these different approaches is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 A comparison of extractive vs. generative LLMs across settings.

The generative LLMs utilized in this article represent some of the most recent available models. The models and approaches include:

-

Meta’s Llama 3.1 is the latest version of the Llama series of language models (Dubey et al. Reference Dubey2024). With 7 billion parameters, it strikes a balance between computational efficiency and performance. For the purpose of this comparison, we used the base model and a ZS approach.

-

Google’s Gemma 2 has 9 billion parameters, represents a significant advancement in the field of LLMs (Team Gemma et al. 2024), offering robust performance across a wide range of NLP tasks while maintaining a relatively compact size. Similar to the Llama 3.1 comparison, we used a Gemma 2 base model, and applied a ZS approach.

-

Alibaba’s Qwen 2.5 has a large pre-training corpus focused on math and coding. Another key improvement, especially in the context that we are using the model for, is the greater accuracy in generating structure outputs (as JSON objects). Qwen 2.5 was also utilized in its base model variant, using a ZS approach.

-

ConfLlama based on LlamA-3 8B, was specifically fine-tuned on the GTD using QLoRA with a learning rate of 2e-4 and LoRA rank of 8. The model was trained with gradient checkpointing enabled and 4-bit quantization, achieving convergence with loss reduction from 1.95 to approximately 0.90 (Meher and Brandt Reference Meher and Brandt2025). We employ both

$Q4_{K_{M}}$

and

$Q4_{K_{M}}$

and

$Q8_{0}$

quantizations for comprehensive performance analysis. Additional details about ConflLlama’s architecture, training methodology, and prompt engineering are provided in Appendix C. In contrast to the base model variants of Llama 3.1, Gemma 2, and Qwen 2.5, the ConflLlama model is a fine-tuned model.

$Q8_{0}$

quantizations for comprehensive performance analysis. Additional details about ConflLlama’s architecture, training methodology, and prompt engineering are provided in Appendix C. In contrast to the base model variants of Llama 3.1, Gemma 2, and Qwen 2.5, the ConflLlama model is a fine-tuned model.

Various performance metrics quantify how well the models classify an event or its key attributes (e.g., actors, actions, locations, and dates). These metrics essentially compare the ground truth with what the machine extracts to produce a numerical result. This distance between the two demonstrates the degree of congruence, and the goal for event data scientists is to achieve 100% congruence across multiple possible sources of error (Althaus, Peyton, and Shalmon Reference Althaus, Peyton and Shalmon2022; Brandt and Sianan Reference Brandt and Sianan2025). For BC, the precision, recall, and the F

1 score are reported. The focus here is the

![]() $F_1$

statistic, the geometric mean of the precision and recall of the classifications, combining both attributes. The NER tasks are evaluated using token-level precision, recall, and macro

$F_1$

statistic, the geometric mean of the precision and recall of the classifications, combining both attributes. The NER tasks are evaluated using token-level precision, recall, and macro

![]() $F_1$

score, which assesses the model’s ability to correctly label each token (including the “O” tag for non-entities).

$F_1$

score, which assesses the model’s ability to correctly label each token (including the “O” tag for non-entities).

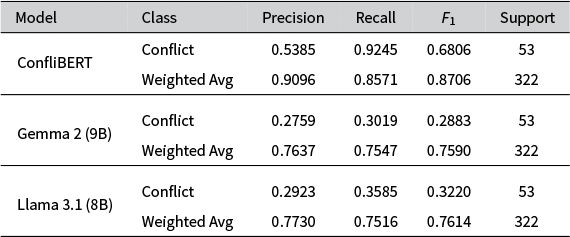

5.2 Binary Classification

To evaluate its performance, ConfliBERT was fine-tuned on the training split of the BBC News dataset for this BC task.Footnote

13

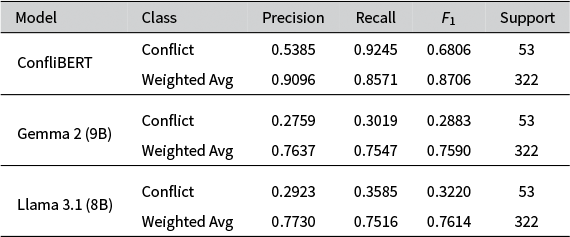

Table 2 shows the BC performance for the BBC News and re3d texts. ConfliBERT has high recall for conflict-related texts, suggesting a strong ability to identify relevant content. ConfliBERT’s disparity between precision and recall for the conflict class indicates that it flags more texts as conflict-related. Meanwhile, Gemma 2 and Llama 3.1 lack the nuanced understanding required for the specific task. Their performance remains poor and they consequently have lower

![]() $F_1$

scores. While Llama 3.1 is marginally better at detecting conflict-related content compared to Gemma 2, it still struggles significantly with this classification task.

$F_1$

scores. While Llama 3.1 is marginally better at detecting conflict-related content compared to Gemma 2, it still struggles significantly with this classification task.

Table 2 Performance metrics for binary classifications of BBC texts.

Gemma 2 and Llama 3.1 show a bias towards classifying texts as non-conflict compared to ConfliBERT—evident from their poor performance on the conflict class. This imbalance suggests that general LLMs may overfit the majority class (non-conflict), potentially due to class imbalance in the training data or limitations in their ability to capture the nuanced features that distinguish conflict-related texts. The performance of Gemma 2 and Llama 3.1 shows that for a basic classification task, a domain-specific model that focuses on a local context is likely superior to a larger more general model when put to the same task. We turn to the issue of further fine-tuning the Llama, Gemma, and related models below.

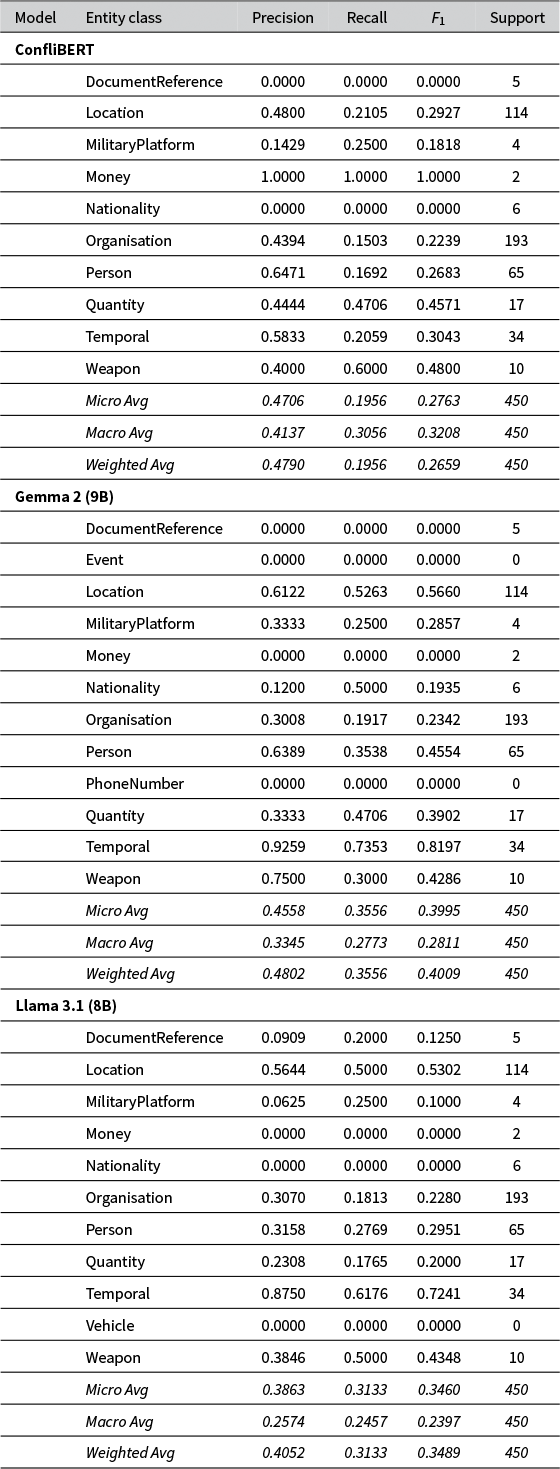

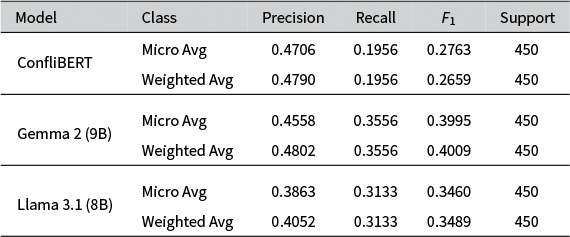

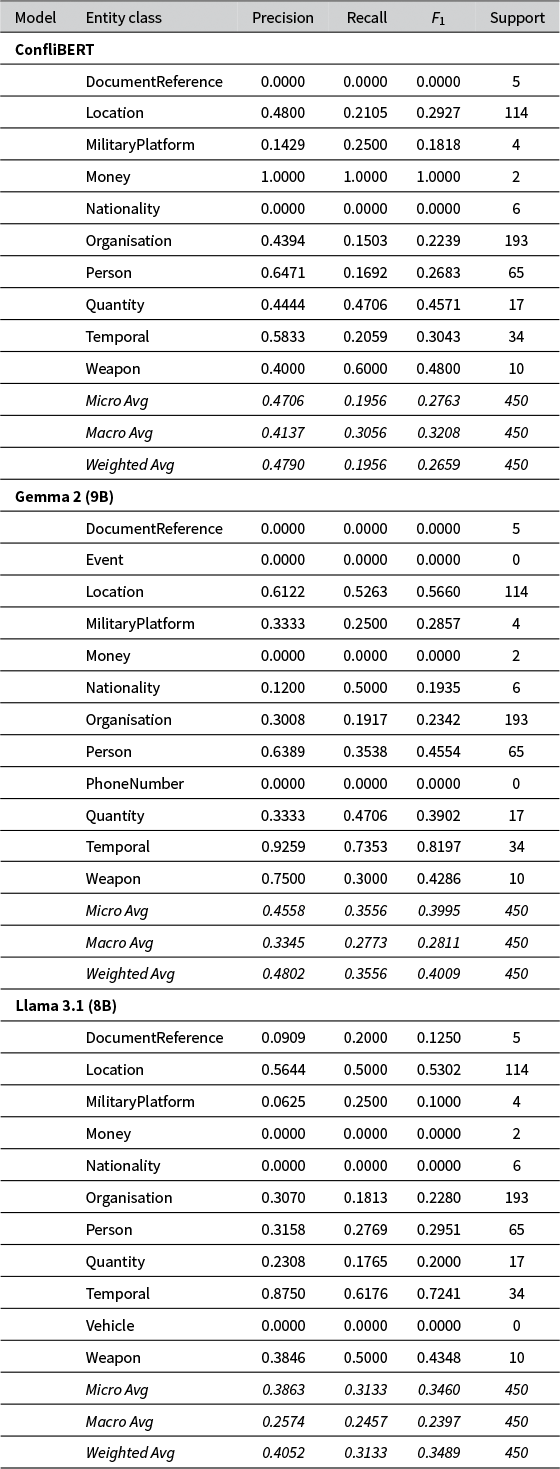

5.3 Named Entity Recognition Results

For this task, the fine-tuned ConfliBERT model was compared against two general-purpose LLMs, Gemma 2 and Llama 3.1, using the re3d dataset. The models’ performance was evaluated using a strict entity-level

![]() $F_1$

score, which requires a model to identify the exact span of tokens and the correct label for an entity to be considered a true positive. This provides a meaningful measure of practical performance than token-level accuracy. To ensure a fair comparison, the LLMs were guided by an instructed prompt that defined all valid entity types and specified a structured JSON output (see Appendix B).

$F_1$

score, which requires a model to identify the exact span of tokens and the correct label for an entity to be considered a true positive. This provides a meaningful measure of practical performance than token-level accuracy. To ensure a fair comparison, the LLMs were guided by an instructed prompt that defined all valid entity types and specified a structured JSON output (see Appendix B).

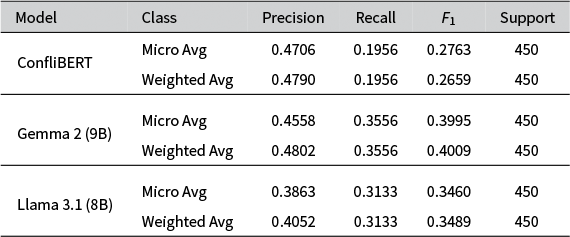

The overall results of the models for re3d are summarized in Table 3. They reveal a critical trade-off between the comprehensive recall of the LLMs and the precision of the specialized model. While Gemma 2 achieves the highest weighted average

![]() $F_1$

score (0.4009), this is largely driven by its higher recall. ConfliBERT’s strength lies in its precision and reliability. It achieved the highest precision score on key, frequent entities like Person and was perfect in its Money classifications. Most importantly, ConfliBERT exhibited perfect discipline by adhering strictly to the required entity schema, producing zero invalid labels.

$F_1$

score (0.4009), this is largely driven by its higher recall. ConfliBERT’s strength lies in its precision and reliability. It achieved the highest precision score on key, frequent entities like Person and was perfect in its Money classifications. Most importantly, ConfliBERT exhibited perfect discipline by adhering strictly to the required entity schema, producing zero invalid labels.

Table 3 Performance metrics for named entity recognition of re3d texts.

In contrast, both generative LLMs failed to adhere to the explicit constraints of the prompt. Despite being provided with a definite list of valid categories, Gemma 2 “hallucinated” non-existent labels like “Event” and “PhoneNumber,” while Llama 3.1 invented a “Vehicle” category. This failure to follow instructions, even with a detailed prompt, makes them unreliable for automated coding systems where data integrity is paramount. Details of these other categories are in Appendix A.

While the LLMs are capable of finding more potential entities, their lack of discipline presents a significant challenge. For specialized domains like political conflict analysis, where precision and the reliability of the output schema are critical, ConfliBERT’s performance represents a much stronger and more practical showing. It proves to be a more robust tool, effectively distinguishing signal from noise without introducing a new layer of error from fabricated categories.

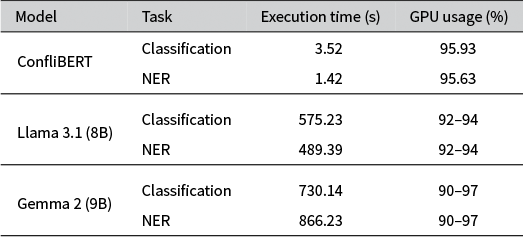

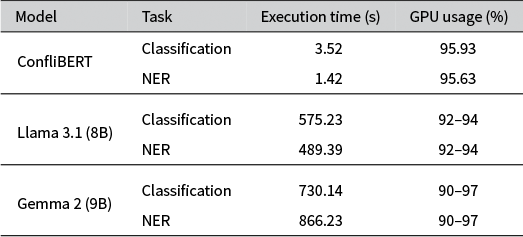

5.4 Computational Performance Comparison

For both the BC task using the BBC News data and the NER task with the re3d, we recorded the execution time.Footnote 14 Table 4 presents the timings for each model and task combination. The most striking difference is the execution time: for classification, ConfliBERT took only 3.52 seconds, while Llama 3.1 (Gemma 2) took 575.23 (730.14) seconds. For NER, ConfliBERT completes the task in 1.42 seconds, compared to 489 (866) seconds for Llama 3.1 (Gemma 2). The speed of ConfliBERT can be attributed to its parallel architecture for processing input data. ConfliBERT’s superior performance stems from its ability to process inputs in parallel. BERT-based models, like ConfliBERT, can efficiently batch multiple inputs and process them simultaneously. Generative LLMs, like Gemma and Llama, typically process inputs sequentially so each text requires a separate request to the model, introducing additional computational overhead. While we parallelize these models by batching multiple task requests, there are context-length constraints on processing the texts that differ across the models.

Table 4 Performance metrics for ConfliBERT, Llama 3.1, and Gemma 2 models.

6 Classifying Texts about Terrorist Attacks

Some pre-training of the generative LLMs could bring their performance up to or exceeding the performance of ConfliBERT (see Wang Reference Wang2024). Fine-tuning a model like ConfliBERT involves training task-specific parameters on top of the base text representations. This is a critical process for adapting the model to new domains or extending its capabilities. This asks for a comparison of ConfliBERT with more recent generative LLMs with pre-training on political conflict texts. Critical is replicability and service as a baseline comparison for event feature classification across new LLMs. This example replicates a common problem: one has identified political conflict-related texts (or prior dataset to be extended) and organized them (say in a CSV, JSON, or other database) for analysis with standard NLP to extract the relevant event information. This then leaves open the choices of the LLM and the pre-training. As an illustration, consider the short texts in the GTD (LaFree and Dugan Reference LaFree and Dugan2007).Footnote 15 GTD is a good choice because it 1) is a comprehensive open-source database of terrorist events, 2) contains the conflict classification tasks (what kind of attack is in the event?), 3) provides consistent, well-structured texts for NLP tasks, and 4) is classified by experts: one knows from the codebook and the dataset who perpetrated the terrorist attacks, the nature of the attacks and the types of victims. One cannot use these texts for the BC task, but they are suitable for evaluating models’ NER and event multi-label classifications.

The task here is predicting the categorization of terrorist attacks from each GTD text description, comparing the various LLMs’ codings to the original (human) GTD annotations of the terrorist attack types. ConfliBERT is compared to the aforementioned Llama and Gemma varieties, a larger LLM (Qwen 2.5), and a fine-tuned variant of Llama that we denote as ConflLlama.Footnote

16

The training prompts for the generative LLMs are given in Appendix B. The selection of evaluation metrics (ROC, accuracy, precision, recall, and

![]() $F_1$

score) follows standard practices in conflict event classification (Schrodt and Van Brackle Reference Schrodt and Van Brackle2012).

$F_1$

score) follows standard practices in conflict event classification (Schrodt and Van Brackle Reference Schrodt and Van Brackle2012).

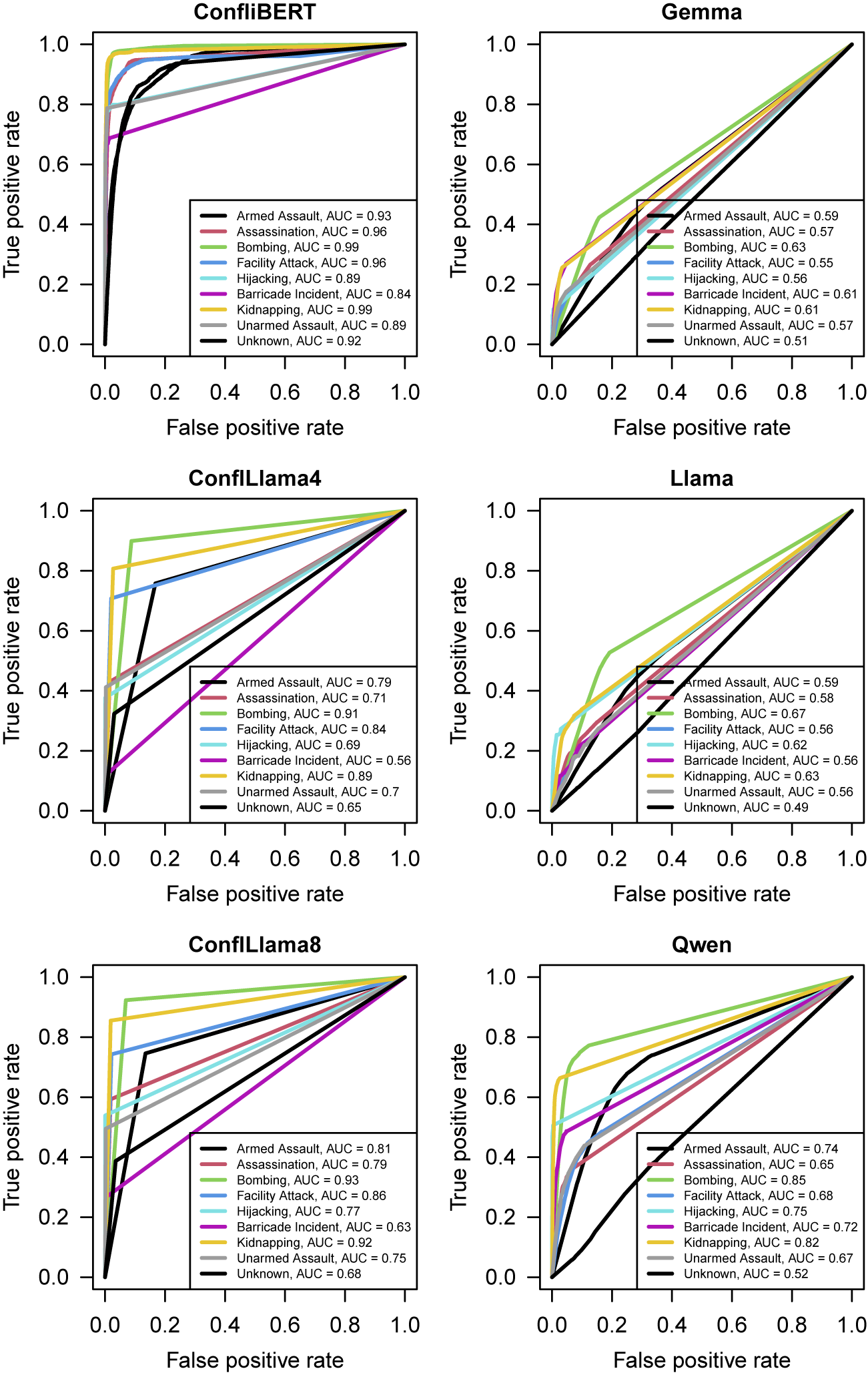

For testing and evaluation, GTD data from 1970 to 2016 are used to train the LLMs and they are tested with data from 2017 to 2020. Most of the GTD events have no texts for 1970–1997, so this is mainly based on training texts from 1998 to 2016. The LLM coded texts produce sets of BCs of each of the nine GTD event types across 37,709 texts recorded in GTD using each of the six models (ConfliBERT, ConflLlama4, ConflLlama8, Gemma, Llama, and Qwen). The first three of these are ones we produce, the latter three are “off the shelf” from Ollama.

6.1 Basic Classification Results

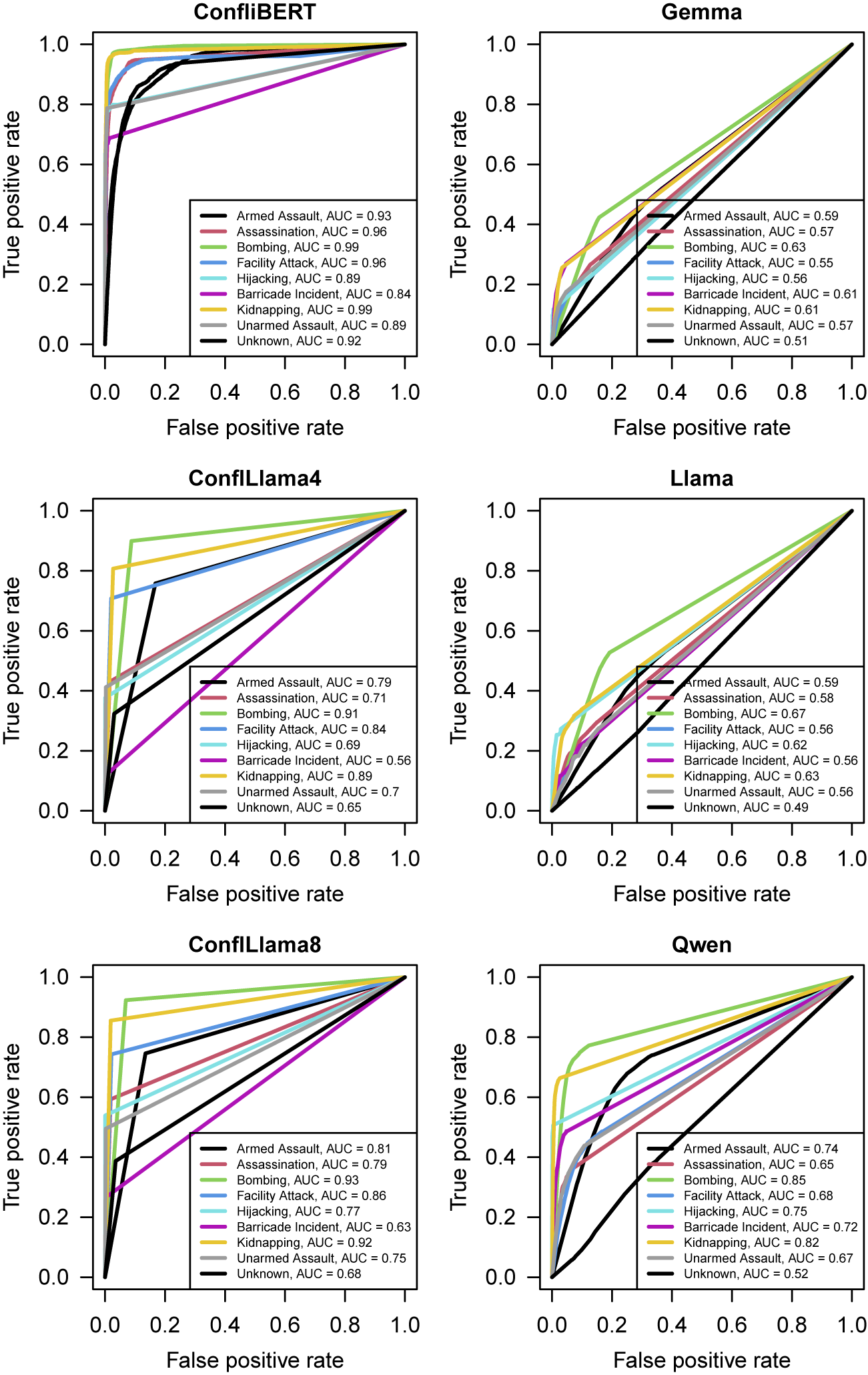

Figure 1 shows the comparative analysis of model performance differences across the LLM architectures. Here, the left column presents receiver-operator characteristic curves (ROCs) for the conflict-trained LLMs, while the right column presents the same for the general (non-conflict data trained), generative LLMs. The results in the right column are closer to a

![]() $45^{\circ }$

line, indicating nearly random classification performance by event-type. The area under the curve (AUC) for each event type is in the lower right.Footnote

17

Across models, the higher accuracy of the ConfliBERT is evident and generally best for events about bombings and kidnappings (the green and gold lines) across the models—the most common kinds of attacks.

$45^{\circ }$

line, indicating nearly random classification performance by event-type. The area under the curve (AUC) for each event type is in the lower right.Footnote

17

Across models, the higher accuracy of the ConfliBERT is evident and generally best for events about bombings and kidnappings (the green and gold lines) across the models—the most common kinds of attacks.

Figure 1 ROC and AUC for each LLM and event type.

Note: Curves along the northwestern edge are better.

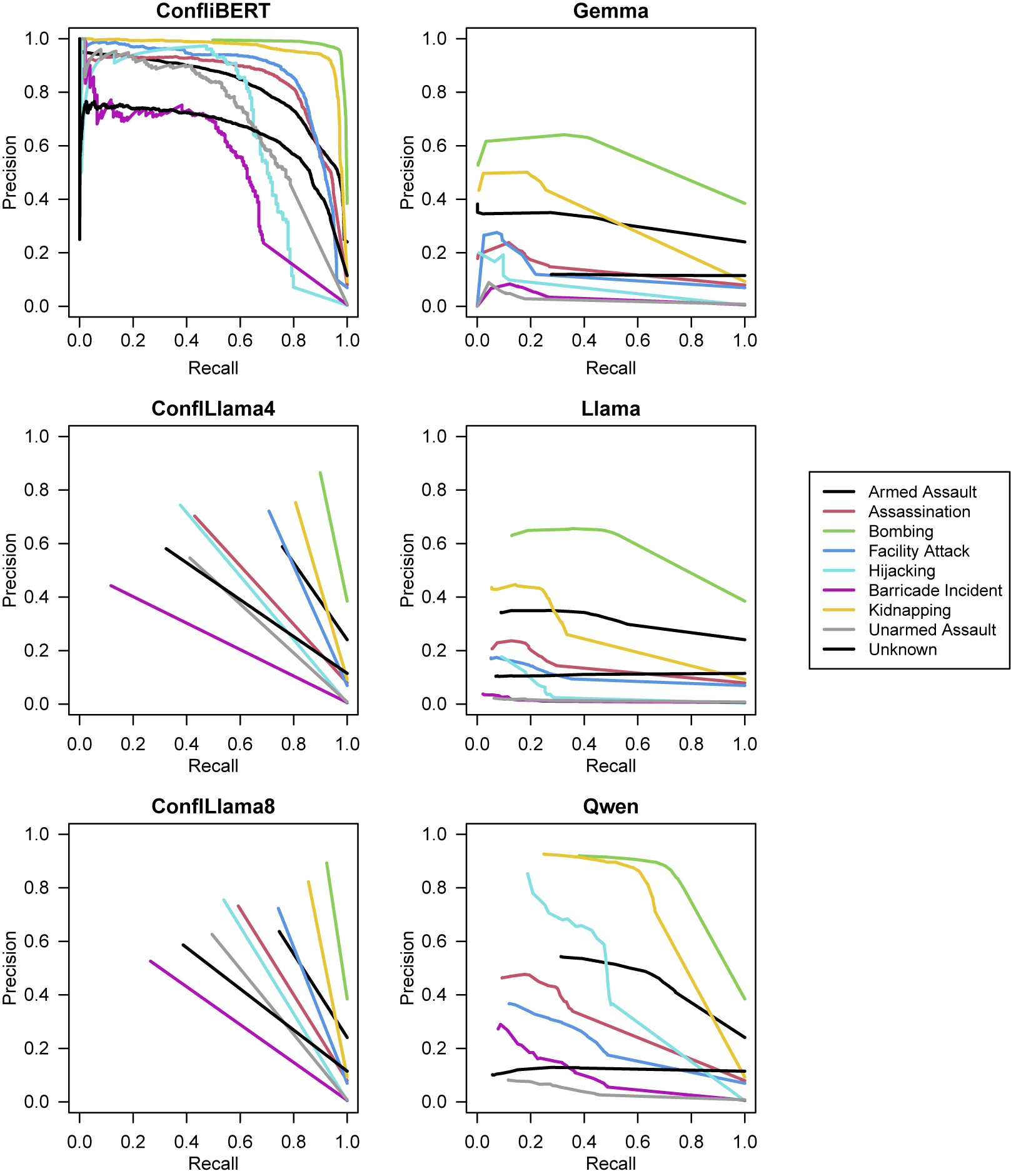

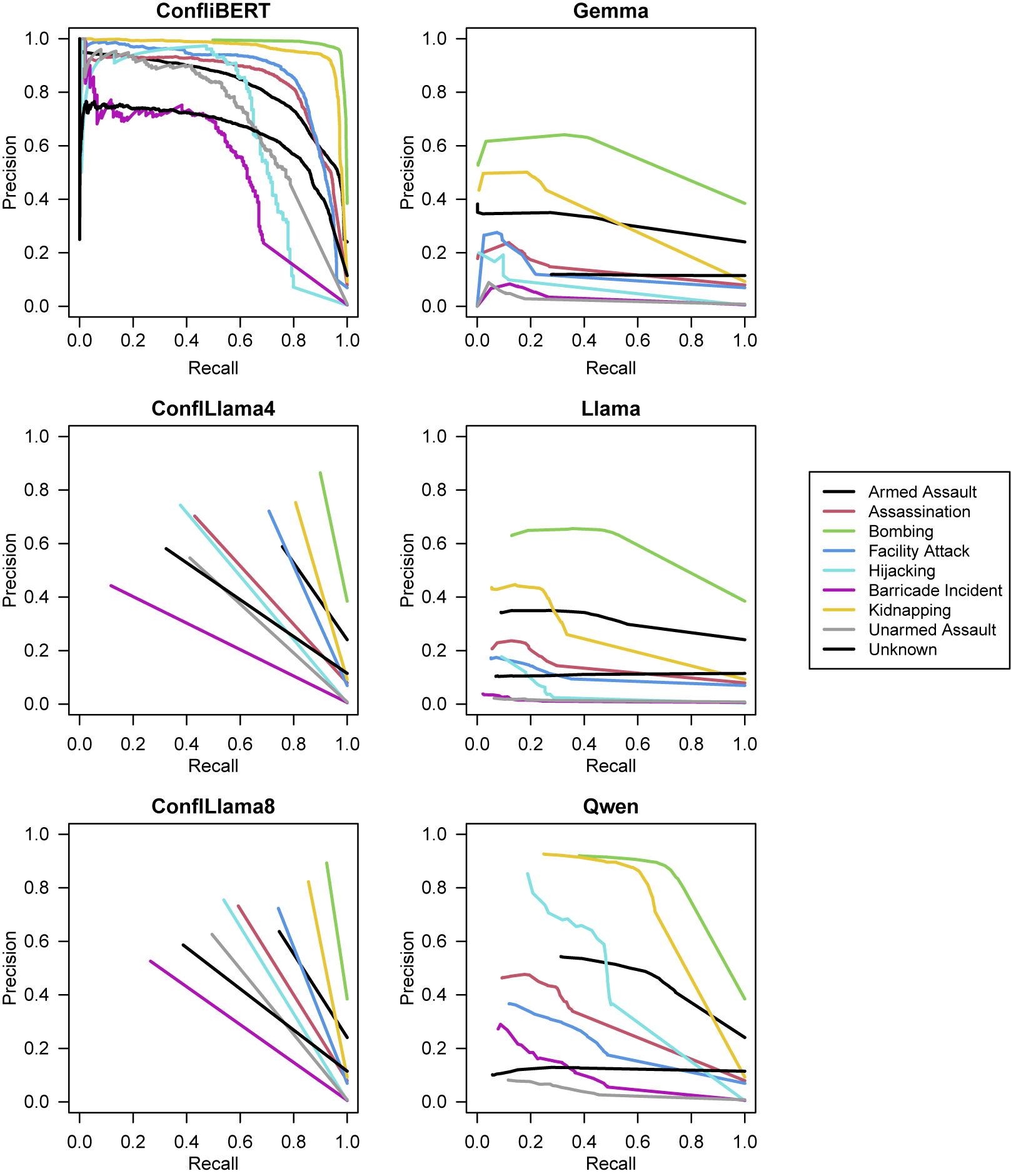

One criticism of only using an accuracy to compare models is that it is inflated by predicting the dominant class for imbalanced problems like the classifications here. Figure 2 shows the models’ precision–recall curves, in parallel with Figure 1. The best precision–recall curves are those that follow the top, northeastern edge of the plot.Footnote 18 ConfliBERT has the highest precision–recall combinations for similar events (i.e., for the same colored lines). Of the larger generative AI models, only the more recent and much larger Qwen model comes close to ConfliBERT and ConflLlama in precision and recall performance, but only for kidnappings and bombings.

Figure 2 Precision–recall curves for each LLM and event type.

Note: Curves along the northeastern edge are better.

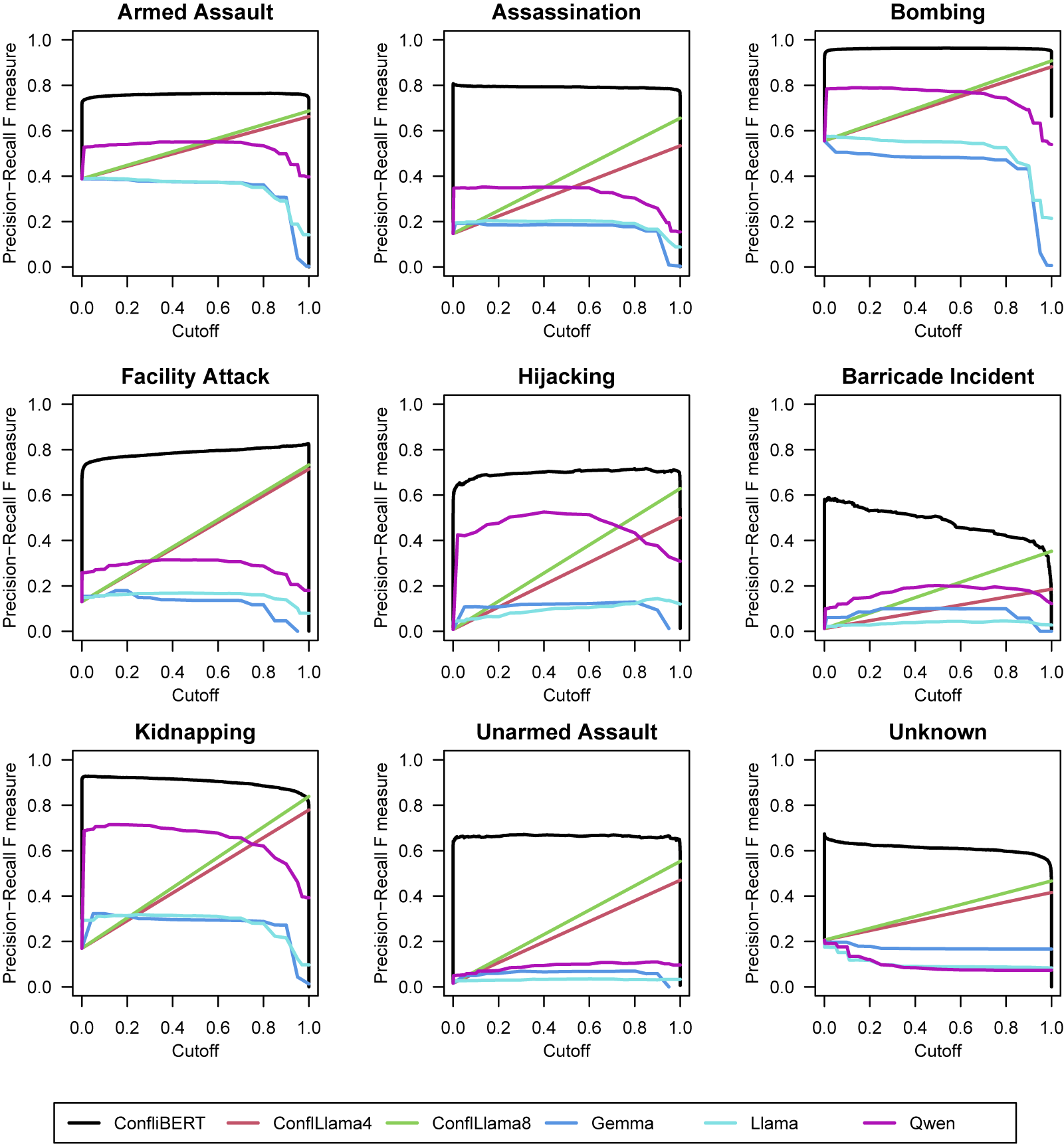

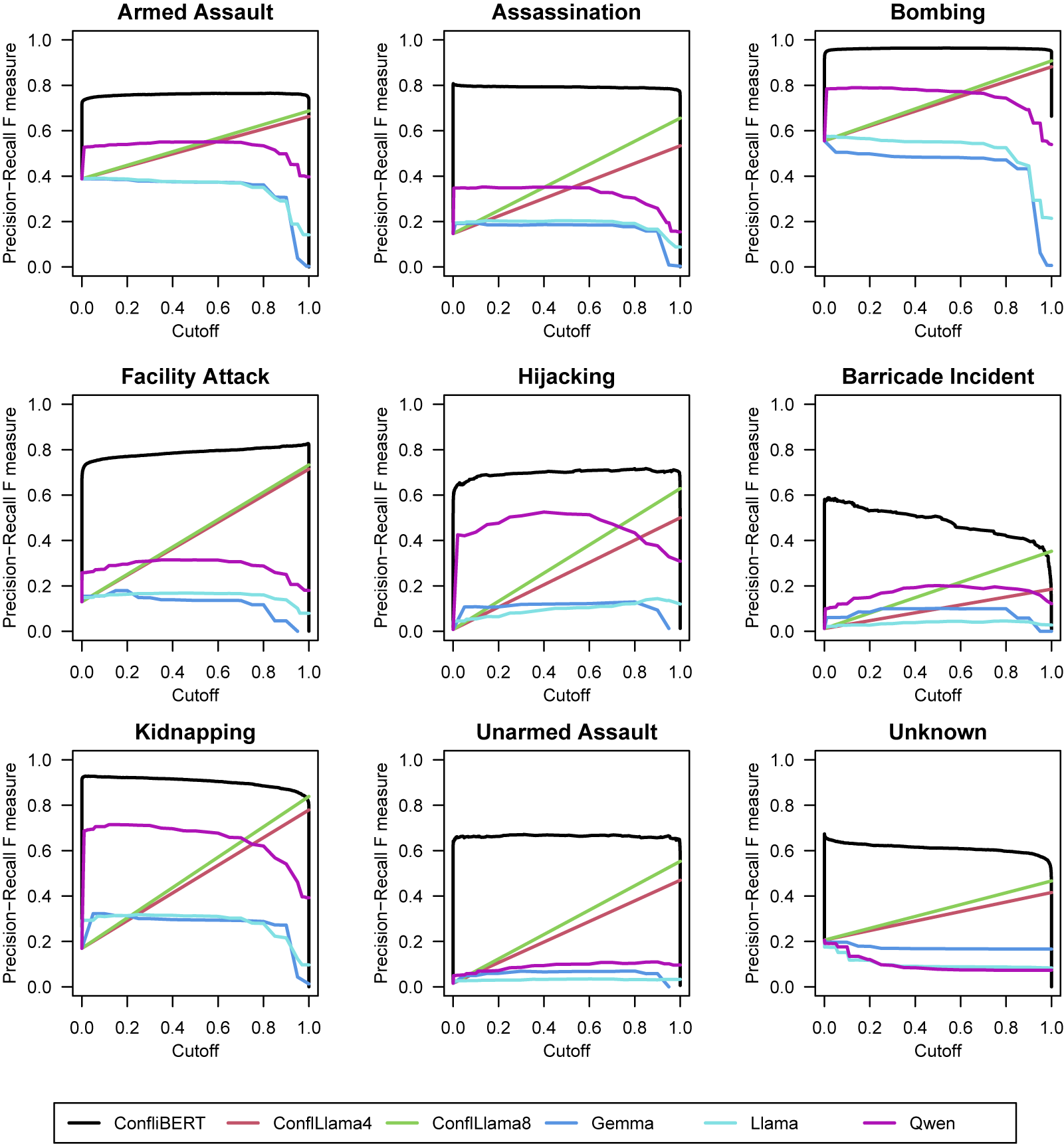

Precision–recall curves are a function of the cutoff used to classify a prediction as a match to GTD. Choosing the wrong cutoff, one may miss the benefits of a model to detect events (and mis-state their precision and recall in Figure 2). Figure 3 presents the

![]() $F_1$

score for the precision–recall as a function of the chosen cutpoint for the correct classification for each event type. Unlike Figures 1 and 2, these are grouped by types of events, so the colors used indicate the models here. Ideally, the values should be high across the cutpoints, like those for ConfliBERT. ConfliBERT and Qwen have the best

$F_1$

score for the precision–recall as a function of the chosen cutpoint for the correct classification for each event type. Unlike Figures 1 and 2, these are grouped by types of events, so the colors used indicate the models here. Ideally, the values should be high across the cutpoints, like those for ConfliBERT. ConfliBERT and Qwen have the best

![]() $F_1$

scores, followed by ConflLlama. These results align with previous findings suggesting that domain-specific fine-tuning often outperforms larger, general-purpose models (Gururangan et al. Reference Gururangan2020). Like in other specialized domains, ConfliBERT’s strong performance can be attributed to its training on conflict-related data.

$F_1$

scores, followed by ConflLlama. These results align with previous findings suggesting that domain-specific fine-tuning often outperforms larger, general-purpose models (Gururangan et al. Reference Gururangan2020). Like in other specialized domains, ConfliBERT’s strong performance can be attributed to its training on conflict-related data.

Figure 3

![]() $F_1$

scores across cutoffs for each event type model.

$F_1$

scores across cutoffs for each event type model.

Note: Higher curves are better.

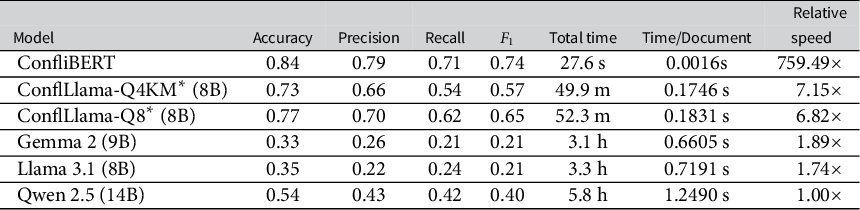

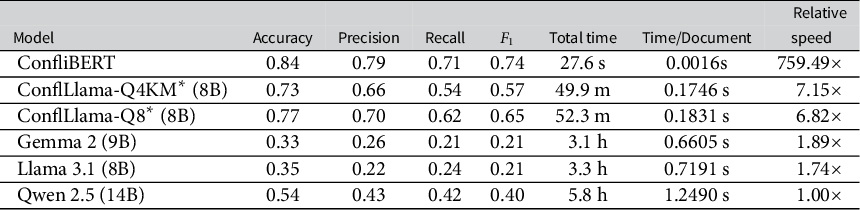

For the GTD conflict-related text analysis tasks, ConfliBERT outperforms the baseline competitors across all metrics as shown in aggregate in Table 5. Its considerable speed improvements over larger models also reflect broader trends in NLP research emphasizing the importance of computational efficiency (Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Dodge, Smith and Etzioni2020).Footnote 19 For the fewer than 40K sentences evaluated here, this is remarkably fast, yet for a larger document processing-training problem, the more general generative LLMs like Gemma, Llama, and Qwen are likely computationally prohibitive. While general-purpose LLMs continue to improve, these results reinforce previous findings that specialized models can achieve superior performance in domain-specific tasks while maintaining significantly lower computational requirements (Strubell, Ganesh, and McCallum Reference Strubell, Ganesh and McCallum2019).

Table 5 Model performance comparison (macro averages).

Note:

![]() $^*$

ConflLlama timing measurements were performed on Delta HPC resources and are not directly comparable to other models’ timing metrics.

$^*$

ConflLlama timing measurements were performed on Delta HPC resources and are not directly comparable to other models’ timing metrics.

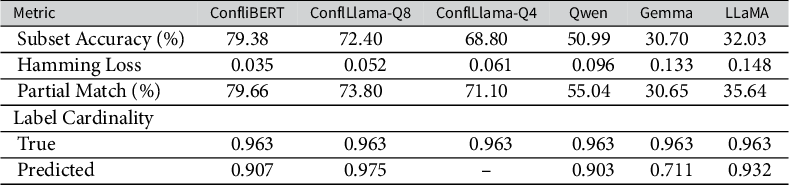

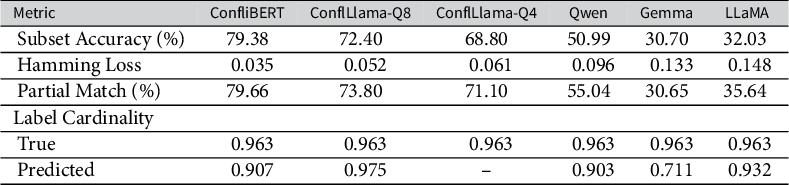

6.2 Multi-Label Classification Performance

Incidents that involve more than one event type are documented with multi-label classifications in the GTD. This occurs say when an incident includes an armed attack or assault in the course of a kidnapping. Multi-label classification is important in conflict event coding, as real-world events often exhibit characteristics of multiple attack types (Radford Reference Radford2021). Less than 10% of the post-2016 (the test period) data has multi-label events. Multi-label classification results, presented in Table 6, demonstrate ConfliBERT’s ability to handle complex event categorizations. The model achieved a subset accuracy of 79.38% and the lowest Hamming loss (0.035), indicating superior performance in scenarios where events may belong to multiple categories. The close alignment between predicted label cardinality (0.907) and true label cardinality (0.963) suggests that the model has effectively learned to capture the multiple classification complexity of conflict events without over- or under-predicting.

Table 6 Multi-label classification metrics.

The performance of ConfliBERT across all metrics suggests several important implications for conflict event classification. First, the results demonstrate that ConfliBERT with domain-specific fine-tuning can substantially outperform larger, general-purpose models, even when the latter have significantly more parameters (Gururangan et al. Reference Gururangan2020). The model’s strong performance on rare event types is particularly noteworthy, as it addresses a common challenge in conflict event classification. This suggests that the fine-tuning process successfully captures the nuanced characteristics of different attack types, even with limited training examples.

6.3 Validity Comparisons

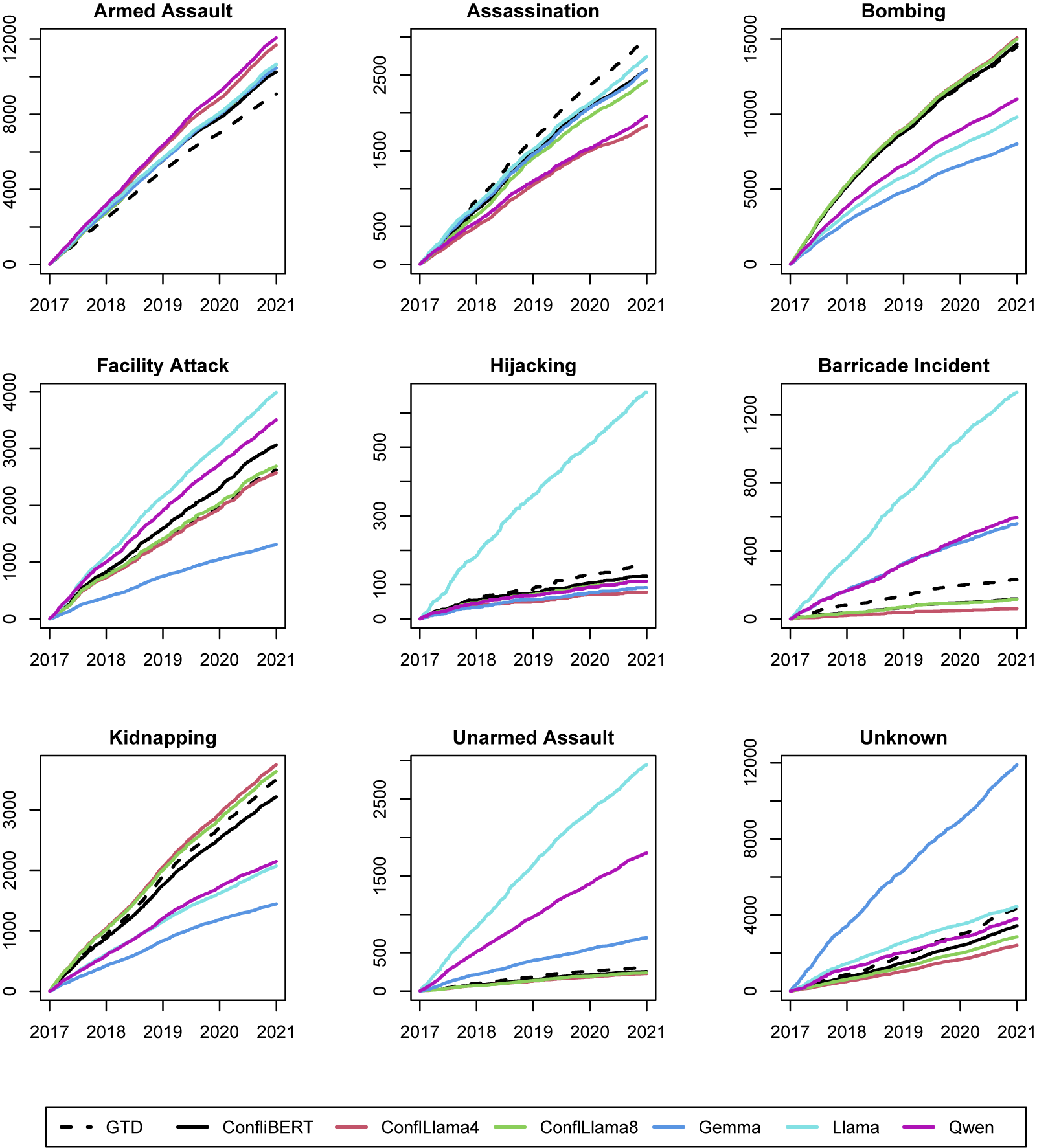

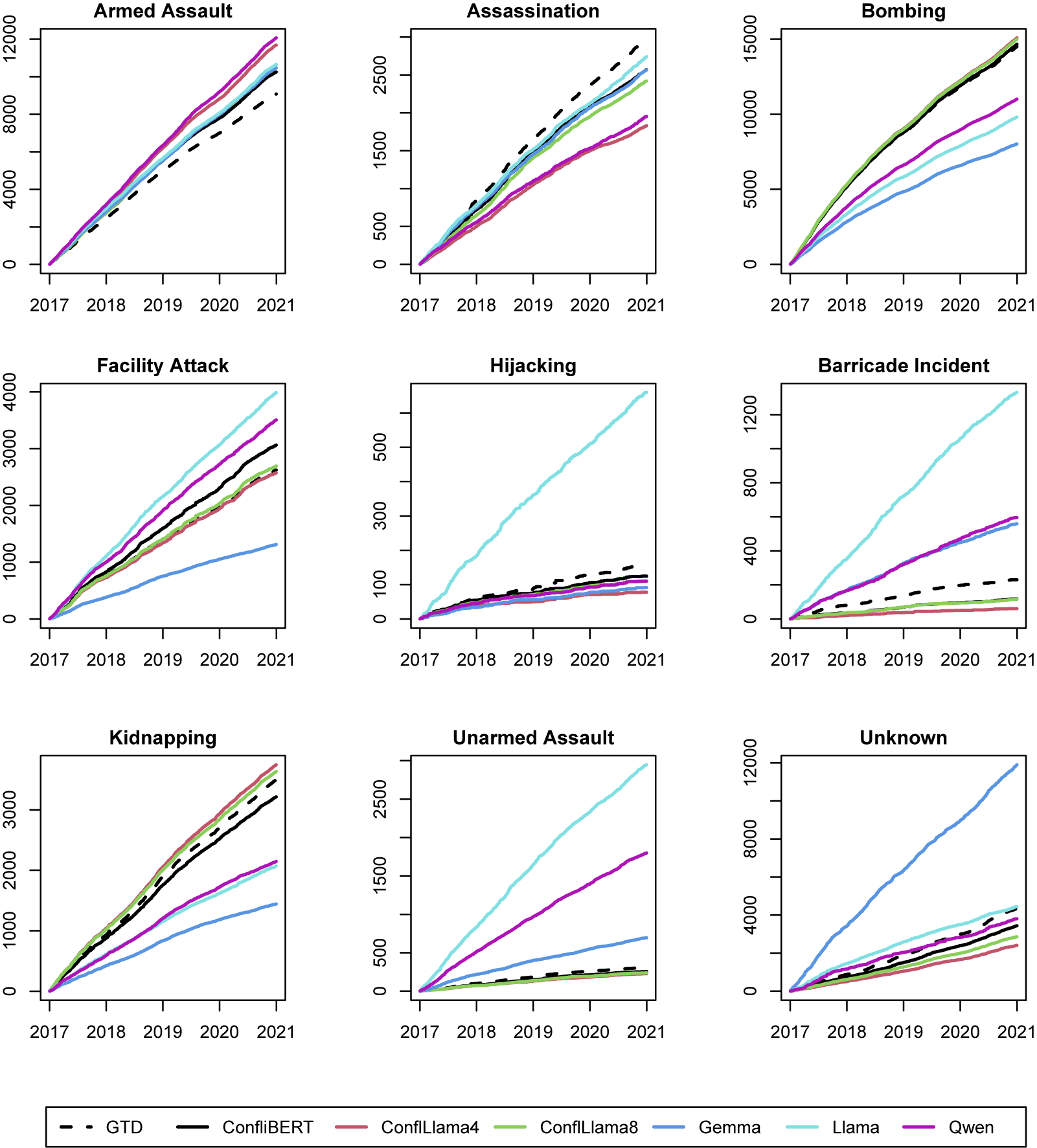

Another assessment of the classification differences from the LLMs is to consider how their distributions change over the event types. At any one point in (recent) time, it may not be evident how the (mis-) classification of a given type of events affects inferences. But if there were systemic biases in LLM classification, they are more evident as more types over events are collected—an inherently time-series process for these data. This is particularly relevant in say a changepoint analysis of the drivers of trans-national terrorism like that addressed in Santifort, Sandler, and Brandt (Reference Santifort, Sandler and Brandt2013, Figures 1–3), who use cumulative sums of terrorist event type classifications over time that would be severely biased upward or downward by LLM mis-classifications like those documented above.

Figure 4 shows the cumulative time series of the number of each type of GTD terrorist event from 2017 to 2020 as a dashed line. LLMs whose classifications are above this line are over-predicting/over-classifying the number of events of a given type, while those under the dashed line are the reverse. A few immediate patterns jump out: the non-conflict pre-trained LLMs under classify bombing events (uppermost-right plot)—so Gemma, Llama, and Qwen. Second, the Llama, Qwen, and Gemma models generally do poorly with the rarest event types (hijackings, barricade incidents, and unarmed assaults), but their performance includes over and under predictions relative to GTD’s human-coded data.

Figure 4 Cumulative number of predicted events, 2017–2021, by type and model.

The reason such deviations and the relative performance of the LLMs matters here is that it will effect downstream time-series analyses since systematically mis-measured event types will lead to incorrect time-series dynamics and inferences that would confound those in works like Santifort et al. (Reference Santifort, Sandler and Brandt2013). This builds on a key point since it shows that even using more data and more sophisticated methods for encoding texts, the issues of aggregation over time will still be important and affect inferences (Shellman Reference Shellman2004).

7 Conclusion

Conflict research and event data have a fruitful history of incorporating NLP approaches to advance methods of unstructured data processing (Beieler et al. Reference Beieler, Brandt, Halterman, Simpson, Schrodt and Alvarez2016; Schrodt Reference Schrodt2001, Reference Schrodt2012). This work continues along that path. The adoption of NLP techniques like those employed by ConfliBERT improves how political scientists can extract and study events and political interactions. These tools offer the potential to analyze larger volumes of text data, enabling more comprehensive studies. They can reduce bias in event coding by applying consistent criteria across large datasets, identify patterns and trends that might be missed by human coders, and enable near-real-time analysis of political events as they unfold. While LLMs generally hold this potential, the approach in ConfliBERT incorporates domain-specific knowledge, resulting in superior performance and even faster data processing for text classification and summarization tasks.

There are a series of conclusions to be drawn from this analysis. The results leverage the existing infrastructure of BERT-alike LLMs and conflict researchers’ expertise to advance scholarship on conflict processes and international security. The contribution is that domain-specific knowledge—the things international and civil conflict scholars know—should be part of the information extraction process used to 1) filter relevant reports (BC), 2) identify events, and 3) annotate their attributes (NER). A BERT-based model plus domain knowledge is able to do this in a way that is better on several metrics as documented in Section 5.

ConfliBERT has several advantages over comparable contemporaneous methods for machine coding events. First, it is easily deployed and replicable as a method since it is open source and can be deployed on conventional hardware. Second, it is significantly better on comparable, relevant quality metrics and faster than rival or even newer generative AI methods that used decoder technologies with graphical processing units (GPUs). Third, it can be rapidly deployed to detect new event data and their characteristics.Footnote 20 This means it can be tuned and adjusted as needed for new cases, data, and texts. This allows users to improve the extraction, coverage (geographically, and as we show, linguistically), across new data and training domains. Fourth, this means that additional downstream tasks, such as recoding texts, extracting additional variables or features, etc., are all much faster and easier than what has historically been the case. We show this in our examples, where differences are seen in the classifications of terrorist event types in the GTD dataset across the LLMs. ConfliBERT and domain-specific models provide much better results compared to generalist LLMs like Gemma, Llama, and Qwen. Fifth, ConfliBERT continues to maintain its superior performance when compared to the most recent encoder models, such as ModernBERT (see Appendix D).

Beyond an infrastructure outline for political scientists to engage with texts about conflict and violence, there are several other contributions of note here. First, ConfliBERT builds on a known ontology (CAMEO/PLOVER) (Schrodt Reference Schrodt2012) for coding events and provides a set of tools for continuing to do so. This allows for additional fine-tuning of the models and a flatter development and learning curve. Unlike current large-scale general LLMs, this allows researchers to openly and quickly work in this area (the span from ConfliBERT in Hu et al. (Reference Hu, Carpuat, Marneffe and Ruiz2022) to the recent paper by Osorio et al. (Reference Osorio2024) is less than 36 months.)

Second, the typical social science conflict researcher need not build their own ConfliBERT: one can fine-tune or extend this model since it is open and available for use via our website and Hugging Face. About 200 GB of combined training data are invested in ConfliBERT, ConfliBERT Spanish, and ConfliBERT Arabic. Additional classifications and training based on new ideas, texts, actors, etc., can be added and evaluated. We have done this in the efforts to extend beyond event coding just in English by working not just with a language and domain-specific dictionary approach (Osorio and Reyes Reference Osorio and Reyes2017), but a general BERT-like model in Spanish (Yang et al. Reference Yang2023) and Arabic (Alsarra et al. Reference Alsarra2023). This shows how the domain-specific approaches can bring old codebooks and ontologies into the LLMs (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Parolin, Khan, Osorio, D’Orazio, Ku, Martins and Srikumar2024). So prior domain knowledge about regions, languages, and events can be part of how LLMs are used to encode and understand new texts and data.

Third, this approach is sometimes better than using larger LLMs. Unlike large generative LLMs, an encoder model like ConfliBERT better fits what a social scientist needs, which is data extraction, organization, and (predictive) classification. Section 5 shows this in terms of performance metrics like accuracy, precision,

![]() $F_1$

, etc. It is also faster to use ConfliBERT. While the initial LLM training for ConfliBERT and its language variants took thousands of GPU hours, the work in Section 5.4 only takes hours of computing time on current laptops. Deploying this on a real data problem is scalable and feasible: it is 300–400 times faster than using a proprietary LLM for NER and 150–200 times faster for BC.

$F_1$

, etc. It is also faster to use ConfliBERT. While the initial LLM training for ConfliBERT and its language variants took thousands of GPU hours, the work in Section 5.4 only takes hours of computing time on current laptops. Deploying this on a real data problem is scalable and feasible: it is 300–400 times faster than using a proprietary LLM for NER and 150–200 times faster for BC.

Finally, there are problems that can be addressed, such as learning about and connecting events and actors. One area of interest is extending ontologies and NER to recognize and learn about new events and actors—who is the next leader, insurgent, or what are they doing? This is related to a literature on continual learning and catastrophic forgetting in LLMs. There is work in this area that can be applied and used to aid models like ConfliBERT as well (e.g., Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Li, Khan, Thuraisingham, Goldberg, Kozareva and Zhang2022). This would also be useful for extending text-as-data methods across networks of texts, languages, etc.

Appendix A NER Performance by Entity Type for re3d

Table A1 Full per-class performance metrics for named entity recognition models for re3d.

Appendix B LLM Prompts

ConfliBERT and ConflLlama are fine-tuned specifically for terrorist event classification, without explicit prompting for output classifications given input event texts. For the general-purpose LLMs (e.g., Gemma, Qwen, and Llama), the following structured prompt is used:

We follow key principles on effective LLM prompting (Liu, Zhang, and Gulla Reference Liu, Zhang and Gulla2023; Wei et al. Reference Wei2022). Its structured format with explicit probability requirements builds on research showing that quantitative outputs improve model classification tasks (Brown et al. Reference Brown2020). The multi-label approach, allowing up to three categories, reflects the complex classification task and the original GTD structure—allowing direct comparisons. The JSON output format facilitates consistent parsing and evaluation, addressing challenges in systematic event coding. This standardization enables direct comparison with both human annotations and across models, while maintaining interpretability.

For the NER task, we employed a similar structured approach:

For BC, we used this simplified format:

Appendix C ConflLlama: Implementation Details

C.1 Fine-Tuning Approach

ConflLlama employs a supervised fine-tuning approach on GTD data, but importantly, it uses a generative text completion methodology rather than a classification head. Unlike ConfliBERT’s encoder-based classification framework, ConflLlama was fine-tuned to generate attack type labels directly as text using a next-token prediction objective—this is distinct from both additional pretraining and instruction fine-tuning approaches.

The model was fine-tuned using parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT), specifically through quantized low-rank adaptation (QLoRA). In this approach, the entire base Llama-3 8B model remains frozen and quantized to 4-bit precision, with only the low-rank adaptation matrices being trainable. These adaptation matrices were applied to specific components of the transformer architecture: query, key, and value projections in the attention mechanism (q_proj, k_proj, v_proj, and o_proj), as well as gate projections and feed-forward components (gate_proj, up_proj, and down_proj). The LoRA adaptation used a rank of 8 and an alpha scaling factor of 16, with no dropout applied during training. This configuration resulted in training only approximately 0.5% of the model’s parameters (roughly 41.9 million parameters), substantially reducing computational requirements while allowing effective domain adaptation.

The fine-tuning objective utilized standard language modeling cross-entropy loss over the output tokens (next-token prediction), focusing on the tokens in the “Attack Types:” section of our template. We did not implement any custom classification-specific loss functions or add classification heads to the model. Training progress was monitored through the language modeling loss, which showed convergence from an initial value of approximately 1.95–0.90 over the course of training. Unlike classifier models, where metrics such as accuracy or

![]() $F_1$

score might be tracked during training, our generative approach meant that the primary training signal was the language modeling loss itself, with classification metrics calculated only during evaluation phases.

$F_1$

score might be tracked during training, our generative approach meant that the primary training signal was the language modeling loss itself, with classification metrics calculated only during evaluation phases.

Our training implementation used an AdamW optimizer with 8-bit quantization, a learning rate of 2e-4 with linear decay, and gradient accumulation steps of 8 for an effective batch size of 8. Memory efficiency was further enhanced through gradient checkpointing, allowing the model to fit within the constraints of a single A100 40 GB GPU while maintaining performance. The model was trained for 1,000 steps, which was sufficient for convergence on the GTD dataset.

C.2 Prediction Methodology

Unlike traditional classification models that output probability distributions over fixed classes, ConflLlama generates the attack type labels as actual text strings. The prediction process works through a structured format where the event description is provided within a prompt template, after which the model generates text to complete the prompt. The generated text is then parsed to extract the predicted attack type labels, which are compared with the ground truth for evaluation purposes.

This generative approach offers significant advantages for multi-label classification tasks. By producing text rather than class probabilities, ConflLlama naturally accommodates cases where multiple attack types apply to a single event. Furthermore, this methodology potentially allows the model to adapt to new classification schemes through additional fine-tuning, as it does not rely on a fixed classification architecture with predetermined output classes.

C.3 Prompt Templates

C.3.1 Training and Evaluation Prompt

For consistent training and evaluation, we employed a structured prompt template that clearly delineates between the input event description and the expected output classification. The template takes the following form:

During the training phase, both the event details and attack types were provided to the model, allowing it to learn the association between descriptions and classifications. During evaluation, only the event details were provided, and the model generated the attack types based on its fine-tuned knowledge.

C.3.2 Prompt Engineering

The selection of an appropriate prompt template is crucial for model performance. We examined multiple prompt variations to identify the most effective format. Alternative formulations included a direct classification request: “Classify the following terrorist event into its attack type(s): Event: {summary} Attack Type(s):” as well as a more elaborate expert-framed request: “You are an expert in terrorism analysis. Based on the following event description, identify all applicable attack types from the GTD schema: {summary}.”

Through empirical testing, we observed only marginal performance differences between these prompts, with variances of approximately

![]() $\pm $

1.5% in

$\pm $

1.5% in

![]() $F_1$

score. Notably, after fine-tuning was complete, the exact prompt wording had substantially less impact than would be expected in ZS models, as the language model had already adapted to the fundamental task structure during training.

$F_1$

score. Notably, after fine-tuning was complete, the exact prompt wording had substantially less impact than would be expected in ZS models, as the language model had already adapted to the fundamental task structure during training.

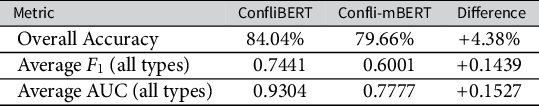

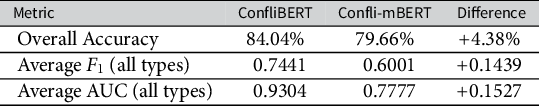

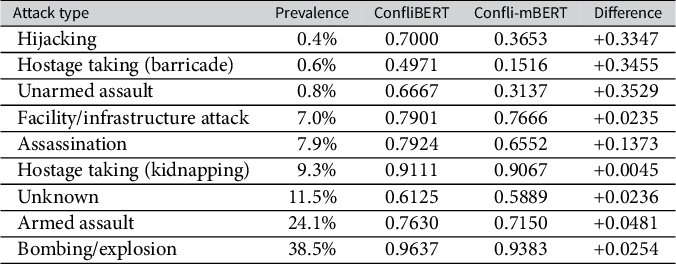

Appendix D ConfliBERT versus ModernBERT

To evaluate whether newer-generation BERT architectures offer performance advantages for terrorism event classification, we fine-tuned ModernBERT on the same GTD used for ConfliBERT training, creatingFootnote 21 Confli-mBERT.

ModernBERT offers several advantages over other BERT architectures: a larger pre-training corpus (2 trillion tokens), modern architectural improvements (Rotary Positional Embeddings and Local-Global Alternating Attention), enhanced long-context understanding (8,192 tokens native window),Footnote 22 and more efficient inference through Flash Attention. Despite these theoretical advantages, ConfliBERT consistently outperformed Confli-mBERT across most metrics:

Table D1 Overall performance metrics.

The performance gap between models showed a strong negative correlation with class prevalence (

![]() $r = -0.83$

), with ConfliBERT demonstrating significantly better handling of rare attack types:

$r = -0.83$

), with ConfliBERT demonstrating significantly better handling of rare attack types:

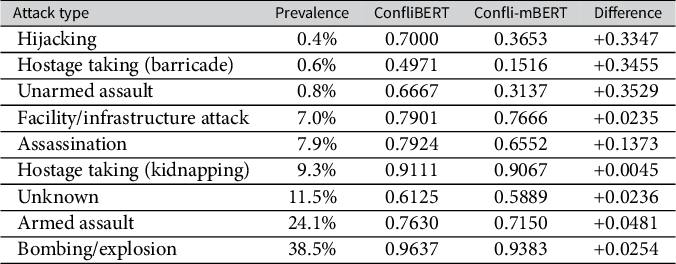

Table D2 Performance on rare vs. common attack types (

![]() $F_1$

score).

$F_1$

score).

This analysis demonstrates that for specialized domain classification with significant class imbalance, domain-specific pre-training is more valuable than general language understanding. ConfliBERT’s architecture is better suited for handling rare event classes, and newer language model architectures do not automatically translate to better performance on specialized classification tasks. Class imbalance handling appears more important than model size or architectural sophistication. These findings challenge the assumption that newer, larger language models inherently perform better across all tasks, emphasizing the continued importance of domain-specific models for specialized applications.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions have been presented at the virtual Methods in Event Detection Colloquium (September 2024), TexMeth 2025 at the University of Houston (February 2025), the 66th Annual Convention of the International Studies Association, Chicago, Illinois (March 2025), and the APSA Virtual Research Group on Advancing the Use of Computational Tools in Political Science (April 2025). Thanks for the suggestions and feedback go to Scott Althaus, R. Michael Alvarez, Ben Bagozzi, Mike Colaresi, Rebecca Cordell, Ryan Kennedy, Hyein Ko, Shahryar Minhas, Philip Schrodt, Nora Webb Williams, Chris Wlezien, and the PA editors and reviewers.

Data Availability Statement

Replication code for this article is available at Brandt et al. (Reference Brandt2025). Replication data and code can be found at Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KDO5AM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: All authors. Methodology: P.B., S.A., V.D., D.H., L.K., S.M., and J.O., Data curation: S.A. and S.M. Data visualization: P.B. Funding acquisition: P.B., S.A., V.D., L.K., and J.O. Writing original draft: P.B., S.A., V.D., D.H., S.M., and M.S. All authors approved the final submitted draft.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by grants from the U.S. NSF 2311142; used Delta at NCSA/University of Illinois through allocation CIS220162 from the Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program, which is supported by NSF 2138259, 2138286, 2138307, 2137603, and 2138296. This material is based upon High Performance Computing (HPC) resources supported by the University of Arizona TRIF, UITS, and Research, Innovation, and Impact (RII). S.A. would like to extend his appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding his work through the ISPP Program (ISPP25-16). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF, NCSA, or the affiliated university resource providers.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical Standards

The research meets all ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements of the study country.