What is a Volk?

A Volk is the totality of people speaking the same language.

Mother Tongue, Fatherland

In 1812, Jacob Grimm fired the opening volley in a lifetime of hostilities with the Danish linguist Rasmus Rask. At stake was the status of German in Schleswig-Holstein and the status of the Danish language as such. Grimm asserted that the hegemony of German over Danish was a historical inevitability – ‘it would be foolish for a mere 1.5 million people to think that they could close themselves off from the unstoppable influx of a neighbouring, closely related language spoken by 32 million and set alight for practically all time by the greatest intellects’ – and he comforted the hapless Danes with the notion that ‘the domination of German letters is not a dishonour, as the dialect speakers of Lower Saxony and East Frisia can confirm’. He then concludes on a note of pathos. His assertion of linguistic patriotism was, he asserts, not only necessary (on the basis that the Danes were trying to oppress the German language in Schleswig-Holstein) but also a spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling: ‘Is it not right, o ye Germans, that you should cherish and value the language which you sucked in as an infant from your mother’s sweet murmurings, together with her milk?’1 And so the deep physical and emotional intimacy between an infant and a nursing mother justifies blatant linguistic irredentism; and the process of one language ousting another in Schleswig-Holstein, viewed from the moral high ground, is simultaneously justified (for German vis-à-vis Danish) and denounced (for Danish-vis-à-vis German).

Language is, as we saw in Chapter 5, a deeply rooted element of what makes humans human; but it is also the primal ambience for societal communication. As such, its public function and status have long been an object of intellectual reflection and public policy-making – going back to Francis I’s Ordinance of Villiers-Cotterêts of 1539 (followed by Du Bellay’s Défense et illustration de la langue françoyse of 1549) and Henry VIII’s ban on Gaelic in English-ruled Ireland in 1543. Since language is a shared thing, owned in common by all who use it, language policies are always a matter for public debate.2 In this chapter we shall trace how that public importance became a national one, a key issue in the self-distinguishing discourse of national identity.

Spelling reforms invariably elicit clashes: the ‘ABC war’ in 1820s Ljubljana, for instance. How should the Latin alphabet, used in Catholic–Slavic countries, render that widespread Slavic consonant that we hear at the beginning of the name of Tchaikovsky? The Cyrillic alphabet has a single letter for it, ч (Чайковский), but German needs four (‘Tschaikowsky’). For Slovenian literati (Slovenian was just finding its way into mass-circulation print) the choice went between the Hungarian solution <cs> (as in csardas), the Polish solution <cz> (as in Mickiewicz) and the Czech use of a diacritical hook (as in the name for that little hook, ‘haček’). Conservative Catholics resisted the haček because, invented as it had been by the humanist reformer Jan Hus (burnt at the stake as a heretic in 1415), it smacked of Protestantism. Thus this minute choice was heavily burdened with international, political and generational allegiances, and therefore heavily debated. In the event, the haček won out, witness the now-standard spelling of such names as Prešeren; but it still comes as a surprise, when reading early-nineteenth-century sources in emerging or subaltern languages, how fluid and variable the competing orthographies and alphabets were. The states that gained their sovereignty in the twentieth-century present their history and their historical figures in the spellings that were subsequently standardized, and thus they project the nationality that eventually crystallized out of historical contingencies back into the past, as if history had been experienced in the form in which contemporary nation-states remember it. The ABC war in fact took place in a city that called itself, at that time, by the German place-name Laibach; one of the participants, the philologist Kopitar, was then called Bartholomäus but now carries the given name Jernej. Again, the Slovak antiquary who spelled his own name as Schaffarik is now known as Šafařik of Šafárik (depending on whether he is invoked by his Czech or his Slovak heirs). The fluidity of the protonational past is hidden from view as it is anachronistically presented in the nationally crystallized form that emerged from it – as if it had ever been thus.3

Across Europe and across the centuries we encounter a public and intellectual investment in language standards, spelling norms and the purist rejection of foreign loanwords; the invocation of ‘mother’s milk’ by Grimm was in fact a quotation from the seventeenth-century language enthusiast Schottelius. The long process of state formation in post-1300 Europe is accompanied, throughout its course, by reflections on the state’s linguistic regime – whether non-state (‘minority’) languages are to be tolerated or discountenanced, and how to ensure public standards for the state language. In this lengthy process, a shift occurred between 1770 and 1810.4

Johann Gottlieb Herder realized that the formative anthropological role of language lay not just in its capacity for articulating and ordering our thoughts and facilitating human sapience but also in its capacity for diversification. Language is, in fact, a proliferation of different languages, each in their different ways articulating and ordering our thoughts and facilitating human sapience in different cultural communities – ‘nations’, as they were soon to be called. As we saw in Chapter 5, languages became the specific markers – carriers, even – of separate national identities.

Following the fall of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, German intellectuals realized that the most important remaining thing they, as ‘the German Nation’, still had in common was in fact the German language – we have encountered Arndt’s stance. As the lexicographer Campe phrased it in the preface to his 1807 German dictionary:

Let me in conclusion commit myself to the firm opinion that in this time, full of impending doom, or even in recent years circling towards absolute downfall, there is nothing more needful, urgent or meritorious for our lamented German nationality that the cultivation – the development, purification and consolidation – of our excellent language. The language is the only remaining tie which holds us together as a nation, is at the same time the only remaining reason to hope that the name of Germans will not altogether disappear from the annals of mankind; the only thing which renders the possibility of a future reunification into an independent polity conceivable.5

It became, following Fichte’s ‘Addresses to the German Nation’, a matter of pride that of all the Germanic tribes that had swarmed over the European landmass during the fifth-century migration period, the Germans had stuck to their ancestral language. The Vandals and Visigoths in Spain, the Ostrogoths and Longobards in Italy, the Franks and Burgundians in France: they all had adopted the Vulgar Latin of their conquered countries, in time switching over to Romance languages. Not so the Germans (with some tribes, as Grimm noted, still occupying their premigration homelands). That linguistic tenacity was seen as fidelity to the ancestral inheritance and as giving the Germans a moral edge over the French and Italians. ‘A nation that abandons its ancestral language is degenerate and anchorless’, Grimm wrote in 1830, meaning that it has lost its rootedness in its inherited identity and character. For the Grimms’ greatest enterprise, the dictionary of the German language (Deutsches Wörterbuch), the chosen motto was ‘Im Anfang war das Wort’ (‘In the Beginning was the Word’; Figure 6.1). That opening phrase of the Gospel according to John, as translated by Luther, was used both metaphysically and anthropologically. It referred to the Word as a Platonic logos but also, more specifically, to the German language as the very bedrock of a German identity – in line, again, with what we saw in Chapter 5.6

Figure 6.1 Title-page vignette for the Grimms’ Deutsches Wörterbuch (1854).

Grimm reverted to the register of Romantic–sentimental pathos in his inaugural lecture (1830) at the University of Göttingen. It was, ironically, delivered in Latin, but it presented an intellectual blueprint of his national commitment. The lecture is entitled De desiderio patriae. That translates as ‘Of homesickness’, which alerts us to one of the crucial turns of thought in this piece. Grimm conflates the notions of desire and love, desiderium and amor, and he leads us from one to the other deliberately and purposefully. For it is amor patriae, rather than desiderium, that presides over his closing sentence:

For in this time of turmoil and change through which there is foreshadowed for us, whether we are aware of it or not, the passage from our traditional ways into a new order, we must hold fast the pure and holy love of our country; for while that love lasts we may even yet be saved, unless the anger of Heaven itself should be against us. Let us then be united in the common purpose to guard like men the honour and liberty to which we are born, with eyes afire and hearts beating high whenever we hear spoken the beloved name of our native land.7

Love of the fatherland for Grimm is a primal instinct tugging at the heartstrings and inspiring homesickness when one is abroad. As an affect it is as intimate and as universal as that bond between infant and breast-feeding mother, and as such it proves that love of the fatherland is ‘naturally human’, neither a socially inculcated political virtue nor a matter of pragmatic expedience. It is the non-negotiable tie that links us to our Art, our collective nature, to those who are close and dear to us; it accompanies us throughout our life’s experiences. And it is intimately bound up with the native language, which in and of itself defines for the German speakers their own homeland. Grimm’s scholarly Latin contains a hard-edged, Arndt-like political conclusion: ‘But our own language, which is the surest foundation upon which our state can rest, we must cultivate and perfect, and not doubt that the limits of its life and power will also be the boundaries of Germany itself.’ And that would include, obviously, Schleswig-Holstein.

In 1848, as a delegate to the Frankfurt Nationalversammlung (National Assembly; see Figure 2.3), Grimm urged persistence in the flagging Schleswig-Holstein war against Denmark;Footnote * he threw his great scholarly prestige behind this belligerence. As he had elaborated in his own attempt at Völkergeschichte, his Geschichte der deutschen Sprache of 1848, and now brought forward in the National Assembly, the Danish dialects of Jutland betrayed a pre-Danish, German substratum in that territory. From that he concluded that a return of those territories into a greater Germany was historically preordained and inevitable. The Danish isles, he felt, were best left to Sweden. Holland, too, would ultimately find its way back to the German bosom from which it had regrettably detached itself a few centuries ago: ‘A reversal of the Dutch to the German language … I consider, over the next centuries, to be a probability which will redound to the benefit of all German peoples. … It stands to reason that the Netherlander would rather become German than French.’8 Language is, then, a cornerstone both of Romantic–sentimental anthropology post-Herder and of nascent nationalist ideology, oscillating between the tender recall of infancy and the hard-bitten demand for geopolitical expansion. Grimm’s meanderings between etymological antiquarianism, sentimental affect and territorial expansionism fully echo the Völkergeschichte and the political agenda of Ernst Moritz Arndt, who sat beside him in the Frankfurt National Assembly. Arndt had patented the territorialization of language in his song ‘What is the German’s Fatherland’, for which he was given a spontaneous, ovational vote of thanks by the Assembly delegates (see Chapter 9).9

This political territorialization of language, extrapolating from language (as a communicative ambience) to language area (a communicatively homogeneous homeland) and thence to state expansionism, is a fundamental characteristic of Romantic nationalism.10 In the second half of the nineteenth century, it forms the cornerstone of almost all manifestations of irredentism, when the presence, outside the state’s borders, of fellow nationals (usually identified as such by their language, more rarely by religion) inspires a policy of expanding the state so as to aim for maximum inclusion and to gather all members of the nation/language community into a single homeland. The nation’s division across different states is felt to be unnatural and undesirable. The geopolitical problems arising from this nostrum are obvious, and they play out along two axes. What to do with border zones, such as Schleswig-Holstein, where there is a mixed bilingual population? And what is, ultimately ‘a’ language? Where do different dialects group together into ‘a’ single language or else fall apart into separate ‘different’ languages? These issues were addressed by the vociferous identity politics of such men as Arndt and Grimm, and it is here that philologists, in particular, played a political role in the fluid years after Napoleon’s downfall.

Macro-nationalism and Pan-movements: German as a Sliding Scale

The Germanic language family has diversified into different standard languages over the past centuries. Norwegian has established itself, in two competing variants, as a language distinct from both Danish and Swedish; Faroese has claimed linguistic specificity on the coat-tails of the Icelandic national revival. In the Netherlands, an uneasy bi-stability has been maintained since 1840 between a common Netherlandic (written) standard and two main (orally based) variants, Flemish and Dutch; Luxembourgish and Afrikaans have become state languages in the course of the twentieth century, and regiolects such as Scots, West Flemish, Low Saxon and Limburgish have at different moments claimed a subsidiary distinctness and recognition. The particularism of minor variants requesting separate recognition can be juxtaposed with an opposite tendency: to group together large family groups as single, compound wholes. The followers of the two tendencies are known as ‘splitters’ and ‘lumpers’.11

The ‘lumpers’ in this process were the German philologists of the Romantic generation: Grimm, Arndt, Hoffmann von Fallersleben and their later adepts, Simrock and Dahn. They saw all variants as mere variations within a greater German language. When Grimm viewed the future convergence of Dutch into German as something beneficial for all German peoples, he apparently included the Dutch themselves in that aggregation of future beneficiaries. That, indeed, is characteristic of the elasticity with which Grimm uses the notion of ‘German’. We have seen an egregious example in the case of Hoffmann von Fallersleben in Chapter 4, where the ‘German’ language as used from Luther to Goethe (Hochdeutsch, ‘High German’) can also subsume ‘Niederdeutsch’ variants that are either regiolects (Low Saxon) or the languages of neighbouring states (Dutch and Flemish). A future merger of all these variants into a greater German whole is then presented as natural and proper – both linguistically and politically. Arndt in 1831 asserted it as the Germans’ ‘right and duty to see Holland and Switzerland joined to the ancient German lands in a new life’. Arndt hastens to add that there should be no forcible annexation or enforced union; but precisely how that reintegration process should be driven forward, and by whom, is glossed over in a contorted, weaseling word salad: ‘as Germany, a united whole, will present itself in such a new, rejuvenated guise, they [the Swiss and the Dutch] could not reasonably refuse acknowledging that as a matter of common sense they should accept an invitation to that effect.’ And he adds, with greater clarity and more menace: ‘But this should be held up to them, if necessary on the point of a rapier: that the Swiss can no longer hire themselves out as mercenaries to combat or even subjugate their fellow Germans, or that the Dutch should remain in a position to throttle and block the Rhine, that vital German artery.’12 In the Frankfurt National Assembly of 1848, much of the deliberation was taken up with geolinguistic questions concerning German borderlands such as the Low Countries, the southern Tyrol and, most of all, Schleswig-Holstein. It was in this context that Grimm asserted, on philological grounds, the right for Germany to include not only Schleswig-Holstein but all of Jutland and prophesied the future merger of Flanders and the Netherlands into the greater German whole.

That, then, is how the ‘lumpers’ use the term ‘German’ in an expansionist sense. Grimm uses it thus in the Deutsche Grammatik, the Geschichte der Deutschen Sprache and the Deutsche Mythologie, where it refers essentially to all the living German languages and dialects spoken on the European continent south of Scandinavia. In this scheme, German, as the centre and default of that linguistic continuum, becomes almost tantamount to ‘Germanic’. And what in the first half of the nineteenth century seemed like the visionary musings of Romantic poets and philologists became part of an expansionist policy, not only regarding Alsace-Lorraine in 1870–1871 but also in the direction of the Low Countries and Denmark, as the German war aims in the two World Wars make clear.

Broadly speaking, the opposition between lumpers and splitters maps onto the distinction between aggregationist and separatist nationalism; the former, aiming to unify large groups, lead into pan-movements such as Pan-Germanism or Pan-Slavism, while the latter tend to claim a separate status for smaller self-distinguishing nationalities such as Flemings or Slovenians. The two intersect, for Flemings are comprised in the larger Germanic category, Slovenians in the Slavic one, as nesting dolls are inside a matryoshka.

In this nesting matryoshka model, sometimes a wider, sometimes a narrower ethnolinguistic category is seen as the one that matters. In Flanders, some lumpers followed a Pan-German logic and placed themselves under the aegis of a greater German whole; other people saw Flemish as an independent, separate sibling language of Dutch; and some splitters even wanted to develop a separate linguistic standard for it based on the outlying dialects as spoken near Ypres. In Scandinavia, Danish anxieties over the possible loss of Schleswig-Holstein to an expanding Germany favoured a reframing of their identity as ‘Scandinavians’, drawing on the cultural kinship and (it was hoped) the political solidarity of Sweden–Norway. But amidst this Pan-Nordic unification ideal, in Norway a rivalry developed between two variants of a Norwegian language standard, and the leading Norwegian playwright Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson later embraced Pan-Germanism.13

So how and why do people, in formulating the relation between language and national identity, opt for one or another of the matryoshka’s nesting shells? How and why do they decide which linguistic differences are decisive and which are inconsequential?

Etic and Emic: Which Differences Matter?

Practically all new states that came into being around 1918 owed their independence to an ethnolinguistic national movement in the preceding decades. From Iceland to Bulgaria and from Finland and Norway to Luxembourg and Bohemia, advocacy for ‘national languages’ had dominated public consciousness-raising since the mid-nineteenth century. Everywhere, minority populations had claimed their status as distinct nations by asserting that what they spoke was a separate language.

Not, emphatically, dialects. ‘Dialects’ was a word colloquially used for subsidiary variants within a language, characterizing a regional variation at best, never a separate nationality. Languages, on the other hand, are demarcated by differences between one another, much as adjoining countries are, and each ideally maps onto its own nation-state. As philologists began to see relations in terms of branching family trees, the status of ‘a language’ derived in large part from having an early historical branch-off point. Lithuanian famously obtained great prestige from the recognition that its descent from Indo-European antedated and bypassed the spit into Slavic, Celtic, Germanic and Romance clusters. The stature of Catalan and Occitan was raised by their status as siblings, rather than offshoots, of French and Castilian Spanish, all of these claiming their own independent derivation from Vulgar Latin (see Chapter 10). The often-encountered formula that Irish, Albanian, Slovenian, Galego and Frisian are ‘ancient’ languages (which, strictly speaking, is nonsensical: how can one language be more ‘ancient’ than another, since all descend equally from the primal origins of human speech?) is a debased echo of this family tree schematization. ‘Ancient’ means, in fact, being an ‘early branch’: a variant whose taxonomic separateness was established early on, as attested by certain archaic (hence ‘authentic’, non-derivative) features.

But the discussion was anything but cut and dried. Linguistic descent is a tangled mycelium, not a neat pedigree. Linguists now roll their eyes at the very idea of distinguishing between the levels of ‘dialect’ and ‘language’. There is no clear-cut criterion that makes the taxon ‘language’ qualitatively or objectively different from the taxon ‘dialect’. As the oft-repeated quip has it, languages are dialects with an army and a navy:14 they are classified as such as a result of that contingent happenstance called state formation. The cases of Afrikaans and Luxembourgish bear this out. Local idioms, originally classed as dialects (a variant of Dutch among the Boers of Southern Africa, and ‘Moselle-Franconian’ in Luxembourg, respectively), they received state-initiated recognition as official languages in 1923 and 1975, in the context of their (relatively recent) state independence.

But while the distinction between a language and a dialect has no underlying, objective foundation (‘etic’, i.e. as part of specific, empirically measurable, language-intrinsic features), it does, as the recognition of Afrikaans and Luxembourgish shows, have a real-world presence. People attach a real-world meaning (‘emic’) to whatever causes them to apply that distinction.Footnote *

Where ‘a’ language begins or ends is historically floating and somewhat arbitrary, and ‘emic’ rather than ‘etic’. Witness the language that used to be called Serbo-Croatian. It embraces, as Slavicists know, a number of interpenetrating regiolects and dialect groups.Footnote ** Important divisions ran through the populations using this language/dialect cluster: between the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires (and Venice), between Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christianity, and between the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. There was only a limited history of communicative interaction between Belgrade, Ragusa (present-day Dubrovnik) and Zagrab/Agram (present-day Zagreb). Cross-communitarian interaction intensified in the nineteenth century, however, and crystallized in the Vienna Literary Agreement of 1850, when assorted intellectuals – each prominent in their respective communities, with Vuk Karadžić among them – signed a declaration asserting the unity of their dialects under a single standard. In the declaration’s preamble, the signatories express their dismay at the diffraction caused ‘not only by alphabets, but still by orthographic rules as well’.15

From this integrationist high point, the last half-century has witnessed a relapse into ‘splitting’ particularism. After the break-up of Yugoslavia, the Serbo-Croatian language lost its unitary status; Croatia and Serbia as separate successor states put forward separate linguistic standards for ‘their’ Croatian and Serbian languages. And with the further dismemberment of Serbia, we have witnessed how Bosnian and Montenegrin have cultivated a divergent linguistic standard from rump-Serbian: for example, by introducing new letters into their state-sanctioned alphabets.16

In all this contested fluidity, one linguistic aggregate remained firmly outside the Serbo/Croatian lumping and splitting: Slovenian. It profited from the philological trump card of the ‘early branch-off’ and independent descent from Old Slavonic, as demonstrated by its archaic and unique feature of the ‘dual number’. In 1808, Jernej Kopitar’s Grammatik der Slavischen Sprache in Krain, Kärnten und Steyermark grouped together the Slavic dialects spoken (and to some extent written) in Styria, Carniola, Carinthia and the Prekmurje region; and he proposed a new ethnonym for these populations: Slovenec. He also asserted the separate and indeed senior position of their language among the Slavic ones. It was, Kopitar argued, independently descended from Old Church Slavonic and had maintained a basic feature of the ancestral Ur-language: Slovenec alone had kept the archaic ‘dual number’, known to educated Europeans from its lingering traces in Homeric Greek and already noted in Kopitar’s 1808 grammar. The dualis, which refers to ‘a pair’ as something that is neither singular nor plural (as in trousers, scissors or twin siblings), has since remained a trump card in the particularism of Slovenian vis-à-vis neighbouring South-Slavic regiolects. Slovenian remained outside the Vienna Declaration on the unity of Serbo-Croatian. Its symbolic prestige ensured for Slovenia a separate status among the southern Slavs who united into Yugoslavia after 1918 and divorced out of Yugoslavia after 1991. If present-day Slovenia as a state can boast an army and an (admittedly diminutive) navy, this is due to the fact that Slovenian has long been recognized as ‘being a language rather than a dialect’ – on the grounds, ultimately, of its dualis.17 And so the dictum that ‘a language is a dialect with an army and a navy’ can be turned on its head: you get to have your own army and navy if you speak a language rather than a dialect.

Matryoshka Scalarity

Thus we encounter the competing forces of splitting (centrifugal particularism, Slovene) and lumping (centripetal aggregationism: Serbo-Croat, South-Slavic). One of the most intractable problems in the negotiations of linguistic identity was and is that of scalarity: how variants of language could be aggregated from the small local regiolect to the large macro-family.

The linguistic ‘family tree’ model saw the great linguistic families (Slavic, Germanic, Romance, Celtic) as great sub-trunks of the Indo-European tree, subdividing from the level of the family to that of ‘languages’ (branches) and then further into ‘dialects’ (boughs and twigs). But the distinction between these successive levels (trunk, branch, bough and twig; language family, language and dialect) was open to debate and subject to ideological agendas.

Accounts of the number of Slavic languages have varied wildly. In 1756, Andrija Kačić-Miošić enumerated eleven of them, erroneously including Albanian; the eminent Göttingen antiquary August Schlözer identified eight, including the obscure and extinct Polabian. In the early 1820s, the no less eminent philologist Josef Dobrovský saw all Slavic languages as dialect offshoots of one common, ancient language, Old Church Slavonic. He distinguished two main groups, with Russian being uneasily assigned to either one or the other. The now-current tripartite division of southern, western and eastern clusters was consolidated only later. Within these clusters, the taxonomy has remained tentative, with certain small variants (Sorbian) enjoying separate status and other pairs, such as Czech and Slovak, and Bulgarian and Macedonian, counted either together as one or separately as two, as the case might be, and some, such as Kashubian or Rusyn, either being overlooked (by outsiders) or else strenuously asserted (by their speakers).18

And so, as the outer twigs of the family tree were being uncertainly counted, there was a tendency to revert it all back to the tree-trunk. Were these variants not all part of a single macro-language? The Slovak Jan Herkel argued this in his Elementa universalis linguae Slavicae e vivis dialectis eruta (Buda 1826), proposing a common Slavic literary language and an ‘Unio in Litteratura inter omnes Slavos, sive verus pan-slavismus’ (A unified literacy for all Slavs, indeed a pan-Slavism). Other Slovak intellectuals, the poet Jan Kollár and the antiquarian Pavol Šafárik, had also opted for this linguistic holism; and so ‘Pan-Slavism’ was born. It manifested itself politically with a Pan-Slavic Congress in Prague in 1848, which got caught up in the revolutionary events of that fateful year (see Chapter 2); and it inspired the paintings of Alphonse Mucha a century later.

The complex history of Pan-Slavism can only briefly be summarized here.19 The initial stage culminated in the 1848 Prague Congress and ended when that congress, and the city of Prague, got embroiled in the armed conflicts around the 1848 revolutions. The pre-1848 Slavic activists (we have encountered Palacký, Šafárik and Kollár) consisted primarily of intellectuals in the Habsburg Empire. Opposing the Habsburgs’ imperial, arbitrary government, they mistrusted the autocracy of the Russian tsar even more; they were themselves mistrusted by the Hungarian nobility (who used ‘Pan-Slavism’ as a scare word) and to some extent by the more aristocratically minded Polish gentry of Galicia – although the 1831 uprising had unleashed a wave of Slavic solidarity. After the failure of the 1848 revolution, a regrouping of Slavic-minded activists looked to Russia, where at the same time a ‘Slavophile’ tendency was taking hold. Denouncing Western European influences, Slavophiles saw Russia as the natural leader of all Christian Orthodox Slavic nations. Pan-Slavism was revived in an 1867 congress held in Moscow and became noticeably more Russian-oriented. This Pan-Russianist tendency continued in force in the mid-twentieth century, spurred on by the German attack of 1941; a Pan-Slavic Committee was formed in Moscow in 1941 and published a monthly periodical from 1943. Following Russia’s victory, in 1945 a

Pan-Slav Congress in Sofia, which had been called by the victorious Russians, adopted a resolution pronouncing it ‘not only an international political necessity to declare Russian its language of general communication and the official language of all Slav countries, but a moral necessity.’ Shortly before, the Bulgarian radio had broadcast a message by the Metropolitan Stefan, vicar of the Holy Bulgarian Synod, in which he called upon the Russian people ‘to remember their messianic mission’ and prophesied the coming ‘unity of the Slav people’.20

Readers will easily discern here the roots of Vladimir Putin’s Ukrainian policies and the influential stance of the Russian Orthodox Church under its Metropolitan Kirill.

Although another Pan-Slavic Congress was held in Belgrade in 1946, chaired by Tito, Yugoslavia opted out of this frame in 1948. Instead, Tito fell back on an alternative, subsidiary pan-movement, South-Slavism or Yugo-Slavism. It had developed out of earlier antecedents (the ‘Illyrian’ movement of the 1830s; the successful self-positioning of Croatia under Jelačić after 1848) and had been marked by an ambivalent position astride Habsburg and Russian orientations – the former strongest in Catholic Slovenia and Croatia, the latter in Orthodox Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria.

The scalar vacillation in pan-movements was driven by the political application of linguistic lumping or splitting. Pan-Slavism assumes the ideal notion of a single Slavic macro-language, with merely secondary (dialectal) differences. Particular emancipation movements will accord even minor etic features a decisive emic (difference-making) importance and, as a result, multiply the number of self-distinguishing Slavic languages – as in the case of Slovak (which came to achieve a position of its own in the course of the nineteenth century) and, latterly, Montenegrin. Three of these Slavic languages would become, or remain, the official languages of independent states: Russian, Polish and Bulgarian. Eight (or seven, depending on how you count Serbo-Croatian) would become co-official languages of federal states: Czech and Slovak in Czechoslovakia; Slovenian, Macedonian and Serbian/Croatian in Yugoslavia; and (intermittently and grudgingly) Ukrainian and Belarusian in the USSR. Sorbian and other smaller variants would subsist as regional minorities. In the century after Versailles, newly self-distinguishing languages would begin to assert their presence, such as Rusyn (in the Carpathian borderlands where Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine meet).

Also in the century after Versailles, the political organization of the self-distinguishing nations and nation-states of Europe did, despite two World Wars and other upheavals, more or less settle down. The break-up of the Habsburg, Romanov and Ottoman Empires saw new states emerge, each with its language now constitutionally enshrined as the ‘national’ one.Footnote * After 1918, linguistic minorities in the new states of Central and Eastern Europe were given some protection under League of Nations regulations. In 1992 the Council of Europe established a Charter for Regional and Minority Languages to which most European states are signatories. As a result, all these minority languages now assert their individuality and their right to maintain themselves under the European charter, and in almost any European country there is an ongoing debate about linguistic diversity. Language is, in short, the mother of all identity politics issues.

Historical Permanence versus Social Outreach

It is not for nothing that philologists, who more than anyone else reflect on variations within languages and on differences and similarities between them, are at the forefront of the lumpers, tending to merge regions and nations into macro-groups (Pan-Slavism, Pan-Germanism, Pan-Celticism). Linguists and philologists are, if nothing else, masters of language. They deal with languages as dexterously as a magician does a deck of cards. For men such as Josef Dobrovský, Jernej Kopitar, Rasmus Rask and Jacob Grimm, Slavic or Germanic really were a single language. Icelandic, Old Saxon and Frisian were as insignificantly different for Rask as Church Slavonic, modern Russian and medieval Czech were for Dobrovský. They corresponded in whatever language came in handy, or (in the case of Kopitar) in a macaronic welter of mashed-up Latin, German and smatterings from various other idioms that all coexisted in his word-soaked brain.21

Such philologists see through centuries of language transformation as if these were merely superficial shifts of complexion. On the family tree of language relationships, they automatically trace the present-day leaves and twigs back to the primordial branches and trunk and even to the tree’s hypothetically reconstructed prehistoric root system. They read with X-ray eyes, discerning the ancient, skeletal roots of words through their modern appearances, immediately sensing how the English gate relates to the Nordic gata or the German Gasse, how the Gaulish name-ending -rix signified royal status, as in the Latin rex or the Gothic -ric, and how Theodoric of Verona could later, in German texts, come to be called Dietrich von Bern. The resemblance between English daughter, German Tochter, Greek θυγατηρ and Sanskrit duhitr would be as predictable to them as the multiplication table. Their expertise of deep linguistic scanning foreshortens the passage of time, as it were: for philologists the tribal Dark Ages were right next door, just a few sound-shifts away. And the tribes of yore were, for them, a recent past, still discernible in their traces. Surely any child could see that the tribe of the Catti mentioned in Tacitus map onto present-day Hessia, or Gaelic leabhar and Welsh llyfr were both derived from Latin liber, ‘book’, a mere millennium and a half ago.

At the ‘lumped’ aggregation level of the language family, historical and linguistic distances are both abolished, and macronationalism can see modern societies as the continuation of the tribal constituents of an original common ethnicity. This is why the ancient Cimbri and Teutones of Jutland are still a present force in the Völkergeschichte and the geopolitical thought of Jacob Grimm. The fifth-century Burgundians of the Nibelungenlied, domiciled between Xanten and Worms on the Rhine, are identified as a tribe that was midway in their migration towards the Bourgogne from their ancestral origin Bornholm (originally Burgundaholmr, obviously).

In looking at the function of language, philologists gravitated to a historicist rather than social emphasis: language is the thing that can be traced as a filiation across time, and it is the thing that ensures that successive generations belong to the same communicative tradition. In nineteenth-century language politics, the philologically inspired view would therefore aim for orthographic and lexical standards that did the greatest justice to the language’s historical antecedents and that would ensure the legibility of the literary heritage by modern readers.

An opposing view emerged around the mid-century; we encounter it particularly among popular educationalists, authors and activists. Their priority was to spread and facilitate literacy and to ensure that even people with low literacy rates and using modern sociolects and regiolects could easily learn a common standard. After 1848, a new generation of language activists drew their experience from social life, folklore and education, rather than from ancient manuscripts and archives. Their frame of reference was much more society-specific. In emphasizing the communicative, present-day bonding power of the language, they opted for standardizations that were more reformist and closer to the usage of present-day speakers, and for a stricter systematization of spelling rules so as to achieve higher literacy rates more easily.

These two opposing viewpoints played themselves out in language standardization debates all over Europe. The prototype is that of Greek, where originally a ‘purified’ (katharevousa) form of the historical language was cultivated, challenged later by a more ‘demotic’ alternative. In Serbia, conservative intellectuals defended the traditional language as liturgically endorsed in the Orthodox Church against the innovations proposed by Vuk Karadžić. In Ireland, the need to salvage and retrieve the old literary language opposed a turn towards the contemporary ‘speech of the people’ (cainnt na ndaoine).22

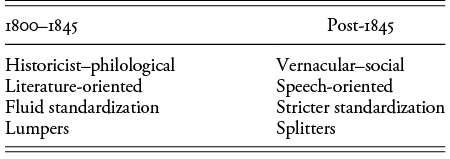

On the whole, it may be said that the philologically based, historicist standard came first, followed at a later stage by the demotic alternative. What is more, the historicist–philological standard tends to prevail among lumpers, favouring an aggregationist, more inclusive view of different variants, while modern demotic standards are more specifically prescriptive and favour ‘splitting’ with competing standardizations for different variants (e.g. Valencian and Balearic alongside Catalan), or competing lexical and orthographic standards (Slovak, Norwegian, Breton). These tendencies are shown schematically in Table 6.1.

| 1800–1845 | Post-1845 |

|---|---|

| Historicist–philological | Vernacular–social |

| Literature-oriented | Speech-oriented |

| Fluid standardization | Stricter standardization |

| Lumpers | Splitters |

The two coexist, of course, the latter being an overlay on the former, not its replacement. But on the whole, over the nineteenth century, language communities tended to diffract into increasingly fine-grained, smaller and hence more numerous aggregates. As the number of self-distinguishing languages (each with its own language area) has grown, the length of the borders between them has increased – and with it, the potential for problematic demarcations and borderline contestations.

The historical dimension declines in prominence, then, as the contemporary social one increases. What remains constant is the undiminishing importance of the territorial dimension, the automatic conceptualization of language as being tantamount to a ‘language area’ and the need to establish clear and fixed boundaries between these. That territorialism would become a cornerstone of the post-1918 nation-state system; and the state-resisting, state-breaking and state-aspiring forces of language assertion would remain a constant in the century after Versailles.

Celts, Aryans, Turanians: Max Müller and Race

Pan-movements such as Celticism were aggregationist from a minority position, rather than hegemonically expansionist or irredentist. The self-defining ‘Celts’, whether as speakers or as a ‘race’, never seriously contemplated turning their kinship into a serious nation-building programme – not even a language revival programme, for the Celtic languages are too tenuously related to be mutually intelligible; nor can they provide a shared communicative ambience. What they share is a sense of marginalization and cultural decline in their respective countries. Their political programme was, at best, to strengthen each other’s positions in their respective states by acts of cultural solidarity and the joint assertion of their independent descent and ‘ancient’ roots. This sense of deep linguistic–mythical roots is asserted, logically enough, in folkloristic displays involving folk dances, folk dress, bagpipes and music, annually at the Interceltic Festival in Lorient (Brittany). And there is a huge statue of the mythical figure Breogán, known from Irish Gaelic legend, in the harbour of La Coruña celebrating the Celtiberian roots of Galicia.23

Pan-Celticism began in the 1820s as a literary collaboration between Welsh and Breton intellectuals and poets. The learned clergyman Thomas Price supported the efforts of the Breton lexicographer Le Gonidec to make a Breton translation of the New Testament. The scheme was funded by the British Foreign Bible Society (BFBS), an association established in 1804 and dedicated to the Protestant mission of making the Scriptures directly available to (potential) believers everywhere, and in their own languages.Footnote * The aims of the BFBS did not envisage the stimulation of anything like a national consciousness or cultural nationalism and were conceived only in terms of Protestant evangelism. Even so, we see an opportunistic working relationship take place between BFBS sponsorship and many activists in ‘Phase A’ cultural consciousness-raising; among them were the Serbian Vuk Karadžić and the Breton Le Gonidec, but also the Albanian Fan Noli. They opportunistically made use of the BFBS agenda to bankroll their philological or literary interests. In Mérimée’s supernatural tale Lokis (1869), the narrator, Professor Wittembach (a spoof on the type of the pedantic German philologist) sets out for the Lithuanian countryside to prepare a new gospel translation into the obscure local language called ‘Zhumaitic’ or ‘Zhmoud’ – a language, as the knowledgeable Professor Wittembach observes, ‘possibly closer than even Lithuanian to Sanskrit’. Mérimée knew full well what he was lampooning; the background details he furnished to his tale were in fact well-informed. Professor Wittembach’s ‘Žmudaitic’ language is close to the local name for the dialect of Samogitia, an important Lithuanian region: Žemaitiu.24

Le Gonidec’s Bible translation, banned as it was by the Catholic authorities in Brittany, was no great success – anecdote has it that Price was reduced to fobbing off excess stock for use in Wales. But the notion of Breton–Welsh kinship took hold. Price, who was involved in the influential coterie around the Welsh-minded Lady Llanover near Abergavenny, launched, in the 1820, the idea of reviving an ancient Welsh literary festival, the eisteddfod. Thanks to the support of Lady Llanover and her network, the idea bore fruit; in fact it was the germination of what today is the highly prestigious and popular Welsh National Eisteddfod. And Price was mindful of his, and his country’s, Breton connections. In 1838, the year of Le Gonidec’s death, his successor La Villemarqué headed a Breton delegation to take part in that year’s Eisteddfod. La Villemarqué plagiarized Lady Charlotte Guest’s work on medieval Welsh poetry to produce his own fanciful Les bardes bretons du VIe siècle, and the notion of a Celtic–Arthurian unity between Wales and Brittany was firmly established. The Welsh institutions of the eisteddfod and the Gorsedd (a neo-bardic council) were copied in Wales and later also in the intermediate region of Cornwall, which likewise looked back upon a ‘Celtic’ past. The word ‘Celtic’ was in these years gaining currency as the technical appellation for the language family of which Breton, Welsh and Cornish formed part. The term had been retrieved from classical usage a century before to refer to the extinct Gaulish language and contemporary Breton.

The Gaelic languages were also included in this ‘Celtic’ complex: Gaelic in its Irish, Scots and Manx variants. It was only in the 1820s that philologists would establish that this Celtic language family did in fact form part of the Indo-European complex. Being ‘Celtic’, and as such an independently descended archaic western outrider of the Indo-European complex, hugely raised the status of Welsh, as we can see from the international, prestigious outreach of the 1830s Eisteddfods of Abergavenny. At these events, German scholars competed for essay prizes. Addresses were read out from Sir Walter Scott, Thomas Moore, Robert Southey and Lamartine; the Eisteddfod even reached out in 1838 to the Calcutta tycoon Dwarkanath Tagore (grandfather of the poet Rabindranath and instigator of the ‘Bengal Renaissance’), then visiting Britain, as a ‘fellow Aryan’. The hub for this international outreach was Christian Bunsen, Prussian ambassador in Britain as of 1842 and brother-in-law to Lady Llanover. Bunsen had philological interests, had learned Persian and Sanskrit and was aware that the westernmost and easternmost branches of the Indo-European ‘Aryan’ language complex were both under Britain’s imperial dominion.25

The Celtic languages were fully placed on the map in 1854, when the German scholar Johann Caspar Zeuss published his august Grammatica Celtica and the French critic and scholar Ernest Renan published La poésie des races celtiques. The latter book, and a visit to the Llandudno Eisteddfod of 1864, would inspire Matthew Arnold’s Oxford lecture series on ‘The Study of Celtic Literature’. By this time, the comparative philology of Celtic antiquity in Indo-European contexts was firmly established as a British imperial enterprise, and scholars noted the ethnographic and ancient legal similarities between Celts and Indians. One of these was the institution of the hunger strike. An ancient Irish bardic hunger strike was thematized in W. B. Yeats’s play The King’s Threshold of 1905; it would suggest a powerful political pressure tactic for Mahatma Gandhi, suffragettes and Irish nationalists.26

Hunger strikes were far from the minds of the Breton–Welsh Celticists of the mid-century as they toasted their benevolent cultural kinship at festive banquets. Pan-Celticism never developed a common separatism but merely acted as an echo chamber that strengthened the national movements in the various Celtic regions. And for the Pan-Celts taking cultural comfort in each other’s kinship and proximity, the Sanskrit word ‘Aryan’ only had the lustre of ancient Brahminic prestige and carried a sense that they, peripheral on the Atlantic fringe of Europe, were enmeshed in a great world civilization.

That sense of connection was fed by Bunsen and, though him, by his protégé Max Müller. Friedrich Max Müller was Mérimée’s Professor Wittembach in real life and probably the most celebrated adept of the Grimm school of comparative philology. A sanskritist and translator of the Rig-Veda (for which he could draw on the resources of the East India Company), he became (aided by Bunsen) a professor at Oxford; thanks to his public lectures and popularizing books on Indo-European languages and comparative mythology, his name became a household word. Like Bunsen, he made his career in a Victorian England that was deeply committed to its Anglo-Saxon connections with the ‘German cousins’; he was naturalized as a British citizen in 1855 and towards the end of his life was even appointed to the Privy Council.27

It was Müller, with his interest in comparative religion, who most famously worked out the deep connections between language, mythology and the cultural DNA of the ‘Aryan nations’. For Müller, mythology was in fact a form of language: natural occurrences such as rain, thunder and fertility were given names as proper nouns, but these were also personal names that could, as deities or personified forces of nature, explain their functions in a mythical narrative.

For mythologists and comparative religionists such as Müller the cultural unity of the Indo-Europeans was not just linguistic but also a matter of collective Weltanschauung, involving parallel gods and goddesses and similar reflections on relations between the physical and the metaphysical. And in turn this fed in to a more racial–ethnic view of what these nations were. We have seen how Ernest Renan spoke of ‘La poésie des races celtiques’; and the word ‘race’ was used more and more freely to refer to the ethnicity of the speakers of related languages (see also Douglas Hyde’s use of racial phraseology). It was, to be sure, often used loosely and metaphorically, not yet in the hard, genetic–biological sense that racists would come to deploy. Even so, scientific racism was gestating in these very decades, drawing on the comparative zoology of Darwin and on the white supremacism of Arthur de Gobineau (Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, 1835). In the year before Max Müller’s death, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, a French-educated Englishman who had married into the anti-Semitic Richard Wagner family, would bring these source traditions together into a hard-core racist theory (The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, 1899). Between them, they gave ‘Aryan’ (for Müller still a neutral term, shorthand for ‘Indo-European’) a very bad name indeed.28

By that time Müller had sharply distanced himself from the equation between language family and race. His famous denunciation is often quoted:

To me an ethnologist who speaks of an Aryan race, Aryan blood, Aryan eyes and hair, is as great a sinner as a linguist who speaks of a dolichocephalic dictionary or a brachycephalic grammar. It is worse than a Babylonian confusion of tongues – it is downright theft. We have made our own terminology for the classification of languages; let ethnologists make their own for the classification of skulls, and hair, and blood.29

But that bluster from the moral high ground is a tad self-serving. Müller is waxing wroth at things he himself had been very prone to. His own ‘Lectures on the Science of Language’ (1861–1864) had constantly mashed up linguistic and ethnic nomenclature, and it was precisely when discussing mythology that the two registers became inextricably entangled. Müller had propounded a cultural/mythological connection between the ‘Aryan races’ as much as a linguistic one: ‘a family likeness between the sacred names worshipped by the Aryans of India and the Aryans of Greece’. ‘In the hymns of the Rig-Veda we still have the last chapter of the real Theogony of the Aryan races.’30

Aryan races – ipse dixit. Müller is throwing stones from inside a glass house of his own making. In truth, the conflation between the family trees of languages and of races was in fact almost unavoidable, and in the decades around 1900 the discourse of ‘race’ drew indiscriminately on ethnography, social Darwinism and comparative linguistics. A deep proclivity towards racialism was at work in comparative philology, although those proclivities were operative elsewhere as well, and not all philologists fell for them – it would be reductive to suggest that ‘all roads lead to Auschwitz’. That being said, the entanglements between ideas of nationhood and notions of race run too deep, far and wide to be ignored.

As a Sanskritist, Müller did not use the term ‘Aryan’ lightly; he knew what it stood for in its original, Sanskrit and Vedic meaning; and he coined a different ethnonym (alongside ‘Semitic’, of course) to designate the Aryan’s defining other. That word he took from the ancient Iranian epic, the Shahnameh, in which the hostile territory to the north of Iran is identified as ‘Turan’. The name had been sporadically used in a territorial sense for the lands east of the Caspian Sea. The word will be known to most readers from the name of the opera character of Princess Turandot, for she features as such in the ancient Persian tale on which that opera’s libretto is ultimately based: as a princess from the Turanian north. The Caspian–Bactrian area north of Iran began to draw the attention of the British Empire around the mid-century, when the colonial spheres of imperial Russia and British India began to edge closer to each other and the two empires faced each other in the Crimean War.

As comparative linguistics elaborated the taxonomy of the Indo-European linguistic family tree, a concept was created to categorize non-member languages such as Finnish, Hungarian and Turkish. Tentative models for a Ural-Altaic group of languages were in the air, and on the basis of a suggestion from Bunsen, Max Müller in 1855 posited the existence of a ‘Turanian’ language family. The background of the Crimean War is evident from the title of Müller’s book: The Languages of the Seat of War in the East, with a Survey of the Three Families of Language, Semitic, Arian and Turanian. Müller included in his Turanian group ‘those languages spoken in Asia or Europe not included under the Arian and Semitic families, with the exception perhaps of the Chinese and its dialects’; he correlated their agglutinative grammar (the concatenation of subordinate clauses into long compound words) with their tribal–nomadic lifestyle, as distinct from ‘state or political languages’ with settled institutions and a more sentence-structured grammar.31 In short, he perpetuated precisely that conflation between language and race which he would later denounce in others. In 1870, Müller also gave a physiological–ethnological profile of the Turanian race: yellow-skinned, slant-eyed, with large jawbones.

‘Turanian’ became a very useful container term for languages that fell outside both the Indo-European and the Semitic clusters, largely in the penumbra of the Russian Empire. Müller asserted that languages as widely distinct as Hungarian and Finnish could be traced back conclusively to this common ‘Turanian’ source. This model got considerable traction in Hungary, which gained new confidence after its constitutional emancipation of 1867 and which was now preparing to celebrate the millennium of the arrival of the ancestral Magyars. The name of ‘Huns’ and of their leader Attila, abhorrent memories in most of Europe, for Hungarians recalled the proud martial days of their horse-riding tribal forebears; and their roaming origin in the plains of Central Asia fitted neatly into Max Müller’s Turan. Hungarian nationalists had sought refuge in Istanbul after the failure of the 1848 insurrections and returned after 1867; they, as well as students who, from anti-Slavic sentiment, felt sympathetic to the Ottoman side in the Russo-Turkish war of 1875–1878, were particularly drawn to the idea that the Turkic and the Magyar nations shared a common homeland in the steppes of Central Asia.32

Turkish-Hungarian connections were personified in Ármin Vámbéry. He had settled in Istanbul in the 1850s as a private tutor, had published a Turkish dictionary in 1858, and had become so deeply assimilated into Ottoman society that he was able to travel incognito between Trabzon, Tehran and Samarkand as ‘Reshit Efendi’ (1861–1863; he published his experiences as Travels in Central Asia, 1864). He was also used by the British Foreign Office as an agent to counteract Russian influence in the region. In later publications he defended a Turanian model whereby the Turks were the direct descendants (and the Hungarians a side branch) of the Turanian tribes of Central Asia (Uigurisch-Türkische Wortvergleichungen, 1870; Die Primitive Cultur des Turkotatarischen Volkes, 1879; Der Ursprung der Magyaren, 1882). The 1893 deciphering of the Orkhon inscriptions, discovered in Mongolia in 1889, as being in a form of Old Turkic provided a boost for the Turkish historical consciousness to look for their pre-Ottoman, tribal roots in Central Asia and ‘Turan’.

Young Turk reformers, organized in the Committee of Union and Progress (1906), occasionally referred to their ethnicity under its ‘Turanian’ appellation: thus Halide Edib Adıvar in her utopian-regenerationist novel Yeni Turan (‘Young/New Turan’, 1912). Since a number of the Young Turk activists had ties with the Turkic populations around the shores of the Caspian Sea and among the Tatars of Russia, the notion of a Turkish ethnicity did not stop at the Ottoman borders. Important go-betweens were the Baku-born, Russian-educated Azeri Hüseyinzade Ali (1864–1931), who later took the family name ‘Turan’, and Yusuf Akçura (1876–1935), of Volga-Tatar descent, raised in Turkey but a Turkic–Muslim activist in imperial Russia between 1904 and 1910 and, following his return from there, editor of the newspaper Türk Yurdu (‘Turkish homeland’, as of 1911). ‘Turanian’ became a term with which to refer to an ethnic Greater Turkey stretching beyond the Anatolian peninsula into Central Asia, and possibly, quite wistfully and romantically, into a de-territorialized and transhistorical ethnic ideal. Ziya Gökalp’s poem of 1911 became a classic.

Turan thus became something that Max Müller would have recognized: a myth – not just in the sense of a fictitious fancy inspiring politics, but in the ethnographic sense of deriving the nation’s deepest origins from primordial Ur-forces – of the legendary ancestral patriarch, Oghuz Khan, father of all the Turkic tribes from Tashkent to Anatolia. These ancestral legends were later complemented by a fancifully revived shamanistic religion, Tengrism.34

Turan was a poetic way of referring to what was in fact Pan-Turkism, attempting in post-Ottoman Turkey to connect with ethnic kin from Xinjiang to Turkestan. It inspired Enver Pasha’s support for the Basmachi rebellion in Turkestan in 1921–1924, and later the fanatical nationalism of the Grey Wolves. That ethno-nationalism is now mainstreamed in ultra-patriotic Turkish films and television series celebrating heroes from the olden days of the ancient Turkic tribes; and it is, more trivially, still behind the douze points solidarity between Turkey and Azerbaijan at Eurovision Song Contests. In Hungary, Turanism provided an attractive alternative to the Finno-Ugric linguistic model, since nationalistically minded Hungarians preferred to align themselves with the warlike, conquering, horse-riding races of Central Asia rather than with the placid, subjugated Finns. Hungarian decorative arts and design developed a specific Central Asian orientalist style, invoking yurt tents and Turkic motifs (Figure 6.2).35

Figure 6.2 Millennium Church, Csikszereda, Romania (designed by Imre Makovecz, completed in 2003).

Both in Turkey and in Hungary, Turanism – discredited though it is as a linguistic category – remains an inspiring identity frame for ethnic nationalists in search of Eurasian connections. The Central Asian ‘Nomadic Games’, hosted in 2018 by Kyrgyzstan, was attended by a roll-call of heads of state/government who represented not only a rogues’ gallery of despotic and/or corrupt regimes, but also the outline of a new, Turan-derived nativist alliance in the twenty-first century: Messrs Erdoğan of Turkey, Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan, Aliyev of Azerbaijan, Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan – and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán.36 Thus the logic of pan-movements can fold nativism into internationalist, (con)federative frameworks of mutual support.