1 Introduction

The problem of deciding when two algebraic structures are isomorphic is fundamental to algebra and computer science. It encompasses issues of decidability and complexity, and it tests the limits of our theories and algorithms. An initial tactic in deciding isomorphism is to identify substructures that are invariant under isomorphisms because doing so reduces the search space. We first discuss groups, where the literature is most developed (see, e.g., [Reference Eick, Leedham-Green and O’Brien7, Reference Brooksbank, O’Brien and Wilson9, Reference Maglione21, Reference Wilson35]), but our results apply to monoids, loops, rings, and nonassociative algebras.

A subgroup H of a group G is characteristic if

![]() $\varphi (H)=H$

for every automorphism

$\varphi (H)=H$

for every automorphism

![]() $\varphi :G\to G$

; it is fully invariant if

$\varphi :G\to G$

; it is fully invariant if

![]() $\psi (H)\leqslant H$

for every homomorphism

$\psi (H)\leqslant H$

for every homomorphism

![]() $\psi :G\to G$

. We use the language of categories, following [Reference Riehl28], and a type of natural transformation to describe our main results (details are given in Section 5.1).

$\psi :G\to G$

. We use the language of categories, following [Reference Riehl28], and a type of natural transformation to describe our main results (details are given in Section 5.1).

Definition 1.1. Let

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

be a category, and let

$\mathsf {A}$

be a category, and let

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

be a subcategory with inclusion functor

$\mathsf {B}$

be a subcategory with inclusion functor

![]() $\mathcal {I}:\mathsf {B}\to \mathsf {A}$

. A counital is a natural transformation

$\mathcal {I}:\mathsf {B}\to \mathsf {A}$

. A counital is a natural transformation

![]() $\iota :\mathcal {C}\Rightarrow \mathcal {I}$

for some functor

$\iota :\mathcal {C}\Rightarrow \mathcal {I}$

for some functor

![]() $\mathcal {C}:\mathsf {B}\to \mathsf {A}$

. The class of all such counitals is denoted

$\mathcal {C}:\mathsf {B}\to \mathsf {A}$

. The class of all such counitals is denoted

![]() $\text {Counital}(\mathsf {B},\mathsf {A})$

. For an object X of

$\text {Counital}(\mathsf {B},\mathsf {A})$

. For an object X of

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

, the X-component of

$\mathsf {B}$

, the X-component of

![]() $\iota $

is the morphism

$\iota $

is the morphism

![]() $\iota _X: \mathcal {C}(X) \to \mathcal {I}(X)$

in

$\iota _X: \mathcal {C}(X) \to \mathcal {I}(X)$

in

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

.

$\mathsf {A}$

.

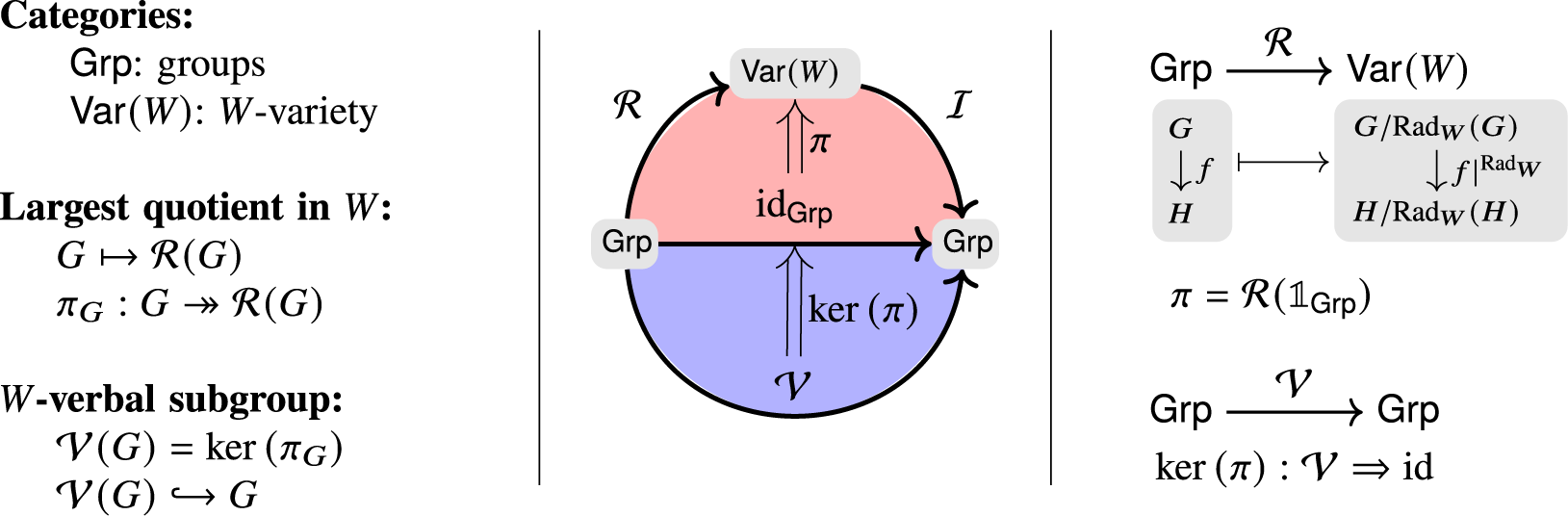

A special case of our results, for the category of groups, can be stated as follows.

Theorem 1. For the category

![]() $\mathsf {Grp}$

of groups and subcategory

$\mathsf {Grp}$

of groups and subcategory ![]() of groups and their isomorphisms, the following equalities of sets hold:

of groups and their isomorphisms, the following equalities of sets hold:

Theorem 1 contrasts a “recognizable” description of characteristic (fully invariant) subgroups with a “constructive” one. For a fixed group G, the sets on the left are of the form

![]() $\{H\mid P(G,H)\}$

, where P is the appropriate logical predicate that allows us to recognize when a subgroup H belongs to the set; those on the right are of the form

$\{H\mid P(G,H)\}$

, where P is the appropriate logical predicate that allows us to recognize when a subgroup H belongs to the set; those on the right are of the form

![]() $\{f(\iota ) \mid \iota \in \text {Counital} (\ldots , \mathsf {Grp})\}$

, where

$\{f(\iota ) \mid \iota \in \text {Counital} (\ldots , \mathsf {Grp})\}$

, where

![]() $f(\iota )=\mathrm {Im}(\iota _G)$

allows us to construct members of the subset by applying a function. Also, the descriptions on the left are “local” since they reference just a single parent group, whereas those on the right are “global” since they apply to the ambient categories.

$f(\iota )=\mathrm {Im}(\iota _G)$

allows us to construct members of the subset by applying a function. Also, the descriptions on the left are “local” since they reference just a single parent group, whereas those on the right are “global” since they apply to the ambient categories.

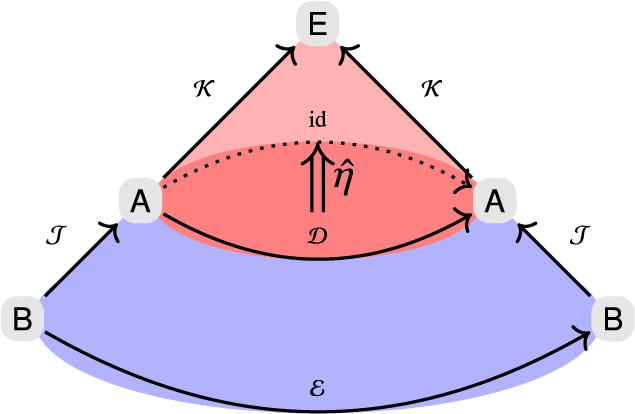

The characterization of characteristic subgroups by natural transformations allows one to recast the lattice theory of characteristic subgroups into the globular compositions of natural transformations as explored in [Reference Baez4, Reference Power27]. We now explore other implications of Theorem 1.

1.1 Constraining isomorphism by characteristic subgroups

Characteristic subgroups constrain isomorphisms in the following sense:

Fact 1.2. Let G be a group with characteristic subgroup

![]() $H\leqslant G$

. If

$H\leqslant G$

. If

![]() $\alpha ,\beta :G\to \tilde {G}$

are isomorphisms, then

$\alpha ,\beta :G\to \tilde {G}$

are isomorphisms, then

![]() $\alpha (H)=\beta (H)$

.

$\alpha (H)=\beta (H)$

.

It is therefore useful for an isomorphism test to locate characteristic subgroups of a group G: every hypothetical isomorphism from G to

![]() $\tilde {G}$

must then assign such a subgroup H to a unique corresponding subgroup

$\tilde {G}$

must then assign such a subgroup H to a unique corresponding subgroup

![]() $\tilde {H}$

of

$\tilde {H}$

of

![]() $\tilde {G}$

. This raises at least two issues. First, if the task is to construct isomorphisms, then we should assume that

$\tilde {G}$

. This raises at least two issues. First, if the task is to construct isomorphisms, then we should assume that

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

is not yet known. How then do we verify that H is characteristic? Is there an alternative definition of the characteristic property that does not directly reference

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

is not yet known. How then do we verify that H is characteristic? Is there an alternative definition of the characteristic property that does not directly reference

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

? A second issue is how to determine the possible

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

? A second issue is how to determine the possible

![]() $\tilde {H}\leqslant \tilde {G}$

when we know only that H is characteristic in G. For familiar characteristic subgroups such as the center

$\tilde {H}\leqslant \tilde {G}$

when we know only that H is characteristic in G. For familiar characteristic subgroups such as the center

![]() $\zeta (G)$

this is possible because the definition is already global to all groups. Hence, a hypothetical isomorphism

$\zeta (G)$

this is possible because the definition is already global to all groups. Hence, a hypothetical isomorphism

![]() $\alpha :G\to \tilde {G}$

must satisfy

$\alpha :G\to \tilde {G}$

must satisfy

![]() $\alpha (\zeta (G))=\zeta (\tilde {G})$

, and typically

$\alpha (\zeta (G))=\zeta (\tilde {G})$

, and typically

![]() $\zeta (G)$

and

$\zeta (G)$

and

![]() $\zeta (\tilde {G})$

can be constructed without explicit knowledge of

$\zeta (\tilde {G})$

can be constructed without explicit knowledge of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

or

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

or

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(\tilde {G})$

. However, the following family of examples, first explored by Rottlaender [Reference Rottlaender29], exhibits groups whose characteristic subgroups have no known global definition, so it is difficult to utilize Fact 1.2.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(\tilde {G})$

. However, the following family of examples, first explored by Rottlaender [Reference Rottlaender29], exhibits groups whose characteristic subgroups have no known global definition, so it is difficult to utilize Fact 1.2.

Example 1.3. Let p be a prime and

![]() $m<p$

a positive integer. Let

$m<p$

a positive integer. Let

![]() $q\equiv 1\bmod {p}$

be a prime and denote by

$q\equiv 1\bmod {p}$

be a prime and denote by

![]() $\mathbb {F}_q$

the field with q elements. Let

$\mathbb {F}_q$

the field with q elements. Let

![]() $\theta \in \operatorname {\mathrm {GL}}_m(\mathbb {F}_q)$

, with

$\theta \in \operatorname {\mathrm {GL}}_m(\mathbb {F}_q)$

, with

![]() $\theta ^p=1$

, be diagonalizable with m eigenvalues

$\theta ^p=1$

, be diagonalizable with m eigenvalues

![]() $a_1,\ldots ,a_m$

, each different from

$a_1,\ldots ,a_m$

, each different from

![]() $1$

, satisfying the following property: if there exists

$1$

, satisfying the following property: if there exists

![]() $u\in \{1,\dots , p-1\}$

with

$u\in \{1,\dots , p-1\}$

with

![]() $a_i^u=a_j$

for all

$a_i^u=a_j$

for all

![]() $i\neq j$

, then

$i\neq j$

, then

![]() $p\nmid (u^k-1)$

for

$p\nmid (u^k-1)$

for

![]() $k\in \{1,\dots , m\}$

. For

$k\in \{1,\dots , m\}$

. For

![]() $m=2$

, this requires

$m=2$

, this requires

![]() $a_1\ne a_2^{\pm 1}$

.

$a_1\ne a_2^{\pm 1}$

.

The cyclic group

![]() $C_p$

of order p acts on the vector space

$C_p$

of order p acts on the vector space

![]() $V=\mathbb {F}_q^m$

via

$V=\mathbb {F}_q^m$

via

![]() $\theta $

. The condition on

$\theta $

. The condition on

![]() $\theta $

means that each eigenspace in V is a characteristic subgroup of the semidirect product

$\theta $

means that each eigenspace in V is a characteristic subgroup of the semidirect product

![]() $G_\theta =C_p\ltimes _\theta V$

determined by

$G_\theta =C_p\ltimes _\theta V$

determined by

![]() $\theta $

, and exactly m of the

$\theta $

, and exactly m of the

![]() $1+q+q^2+\cdots +q^{m-1}$

order q subgroups of

$1+q+q^2+\cdots +q^{m-1}$

order q subgroups of

![]() $G_\theta $

are characteristic. Two such groups

$G_\theta $

are characteristic. Two such groups

![]() $G_\theta $

and

$G_\theta $

and

![]() $G_\tau $

may be isomorphic even if the eigenvalues of

$G_\tau $

may be isomorphic even if the eigenvalues of

![]() $\theta $

and

$\theta $

and

![]() $\tau $

are different. For example, this occurs when

$\tau $

are different. For example, this occurs when

![]() $\tau =\theta ^j$

for some j coprime to p. Thus, the correspondence between characteristic subgroups of

$\tau =\theta ^j$

for some j coprime to p. Thus, the correspondence between characteristic subgroups of

![]() $G_\theta $

and

$G_\theta $

and

![]() $G_\tau $

is not a priori clear.

$G_\tau $

is not a priori clear.

One of the goals of this work is to reinterpret the definition of a characteristic subgroup in a way that is independent of automorphisms and which is unambiguously defined for all groups. We do this by formulating the characteristic condition on the entire category of groups, thereby providing a categorification of the property of being characteristic. Moreover, our formulation pairs well with – and indeed is motivated by – the necessities of computation (see Section 1.3). To address this, we employ methods from theorem checking, specifically type-theoretic techniques [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, Reference Pierce26, 34]; these have recently become accessible through systems such as Agda [2], Coq [11], and Lean [Reference de Moura and Ullrich23].

1.2 A local-to-global problem

Our approach is to transform the local characteristic property of subgroups into an equivalent global property of the category of all groups and their isomorphisms. Calculations now take place within the category instead of within individual groups, which opens up new ways to search for characteristic subgroups. Our approach also facilitates an a priori verification of the global characteristic property, rather than the usual a posteriori check that requires knowledge of automorphisms. The process is analogous to proving that

![]() $\zeta (G)$

is characteristic without employing specific properties of G. Our methods extend to every characteristic subgroup, even those discovered via bespoke calculations.

$\zeta (G)$

is characteristic without employing specific properties of G. Our methods extend to every characteristic subgroup, even those discovered via bespoke calculations.

The traditional model of a category

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

involves both objects and morphisms. By sometimes focusing only on morphisms, we work with categories as an algebraic structure with a partial binary associative product on

$\mathsf {A}$

involves both objects and morphisms. By sometimes focusing only on morphisms, we work with categories as an algebraic structure with a partial binary associative product on

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

– given by composition of its morphisms – and with identities

$\mathsf {A}$

– given by composition of its morphisms – and with identities ![]() an object in

an object in

![]() $\mathsf {A}\}$

. It is partial because not every pair of morphisms is composable, in which case the product is undefined. This perspective yields an algebraic framework for our computations.

$\mathsf {A}\}$

. It is partial because not every pair of morphisms is composable, in which case the product is undefined. This perspective yields an algebraic framework for our computations.

The morphisms of a category can act on the morphisms of another category either on the left or the right. Although several interpretations of “category action” appear in the literature [Reference Bergner and Hackney5, §2], [25], [Reference Freyd and Scedrov14, 1.271–274], there is no single established meaning. Our formulation uses partial functions that are purposefully undefined for some inputs; see Section 2.5 for a precise definition. Let

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

,

$\mathsf {A}$

,

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

, and

$\mathsf {B}$

, and

![]() $\mathsf {X}$

be categories. A left

$\mathsf {X}$

be categories. A left

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

-action on

$\mathsf {A}$

-action on

![]() $\mathsf {X}$

is a partial function, where

$\mathsf {X}$

is a partial function, where

![]() $a\cdot x$

is defined for some morphisms a of

$a\cdot x$

is defined for some morphisms a of

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

and x of

$\mathsf {A}$

and x of

![]() $\mathsf {X}$

, that satisfies two conditions inspired by group actions. The first is that

$\mathsf {X}$

, that satisfies two conditions inspired by group actions. The first is that

![]() $(a\acute {a})\cdot x=a\cdot (\acute {a}\cdot x)$

, whenever defined, for all morphisms

$(a\acute {a})\cdot x=a\cdot (\acute {a}\cdot x)$

, whenever defined, for all morphisms

![]() $a,\acute {a}$

of

$a,\acute {a}$

of

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

and x of

$\mathsf {A}$

and x of

![]() $\mathsf {X}$

. The second is that

$\mathsf {X}$

. The second is that ![]() ; to simplify notation we write

; to simplify notation we write ![]() . As in the theory of bimodules of rings, an

. As in the theory of bimodules of rings, an

![]() $(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-biaction on

$(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-biaction on

![]() $\mathsf {X}$

is a left

$\mathsf {X}$

is a left

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

-action and a right

$\mathsf {A}$

-action and a right

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

-action on

$\mathsf {B}$

-action on

![]() $\mathsf {X}$

such that for every morphism a in

$\mathsf {X}$

such that for every morphism a in

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

, b in

$\mathsf {A}$

, b in

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

, and x in

$\mathsf {B}$

, and x in

![]() $\mathsf {X}$

,

$\mathsf {X}$

,

whenever both sides of the equation are defined. For

![]() $(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-biactions on categories

$(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-biactions on categories

![]() $\mathsf {X}$

and

$\mathsf {X}$

and

![]() $\mathsf {Y}$

, an

$\mathsf {Y}$

, an

![]() $(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-morphism is a partial function

$(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-morphism is a partial function

![]() $\mathcal {M}:{\mathsf {Y}}\to \mathsf {X}$

such that

$\mathcal {M}:{\mathsf {Y}}\to \mathsf {X}$

such that

whenever

![]() $a\cdot y\cdot b$

is defined for morphisms a in

$a\cdot y\cdot b$

is defined for morphisms a in

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

, b in

$\mathsf {A}$

, b in

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

, and y in

$\mathsf {B}$

, and y in

![]() $\mathsf {Y}$

.

$\mathsf {Y}$

.

We write

![]() $\mathsf {A}\leqslant \mathsf {B}$

to indicate that

$\mathsf {A}\leqslant \mathsf {B}$

to indicate that

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

is a subcategory of

$\mathsf {A}$

is a subcategory of

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

, and denote the identity functor of

$\mathsf {B}$

, and denote the identity functor of

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

by

$\mathsf {A}$

by

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {A}} : \mathsf {A} \to \mathsf {A}$

. A counit is a counital of the form

$\operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {A}} : \mathsf {A} \to \mathsf {A}$

. A counit is a counital of the form

![]() $\eta : \mathcal {C}\Rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {A}}$

. The following specialization of one of our principal results to groups describes how characteristic subgroups relate to counits and morphisms of category biactions.

$\eta : \mathcal {C}\Rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {A}}$

. The following specialization of one of our principal results to groups describes how characteristic subgroups relate to counits and morphisms of category biactions.

Theorem 2. Let G be a group and

![]() $H\leqslant G$

with inclusion

$H\leqslant G$

with inclusion

![]() $\iota _G:H\hookrightarrow G$

. There exist categories

$\iota _G:H\hookrightarrow G$

. There exist categories

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

and

$\mathsf {A}$

and

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

, where

$\mathsf {B}$

, where ![]() , such that the following are equivalent.

, such that the following are equivalent.

-

(1) H is characteristic in G.

-

(2) There is a functor

$\mathcal {C} : \mathsf {A} \to \mathsf {A}$

and a counit

$\mathcal {C} : \mathsf {A} \to \mathsf {A}$

and a counit

$\eta :\mathcal {C}\Rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {A}}$

such that

$\eta :\mathcal {C}\Rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {A}}$

such that

$H = \operatorname {\mathrm {Im}}(\eta _G)$

.

$H = \operatorname {\mathrm {Im}}(\eta _G)$

. -

(3) There is an

$(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-morphism

$(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-morphism

$\mathcal {M}:\mathsf {B}\to \mathsf {A}$

such that

$\mathcal {M}:\mathsf {B}\to \mathsf {A}$

such that  .

.

We emphasize that the category

![]() $\mathsf {B}$

in Theorem 2 need not be a subcategory of

$\mathsf {B}$

in Theorem 2 need not be a subcategory of

![]() $\mathsf {Grp}$

; see Section 8 for an example. Moreover, our results apply to characteristic substructures of varieties of algebraic structures, which include monoids, loops, rings, and nonassociative algebras. This generalization (Theorem 2-cat) and its dual version (Theorem 2-dual) are proved in Section 6. We now illustrate how natural transformations arise from characteristic substructures.

$\mathsf {Grp}$

; see Section 8 for an example. Moreover, our results apply to characteristic substructures of varieties of algebraic structures, which include monoids, loops, rings, and nonassociative algebras. This generalization (Theorem 2-cat) and its dual version (Theorem 2-dual) are proved in Section 6. We now illustrate how natural transformations arise from characteristic substructures.

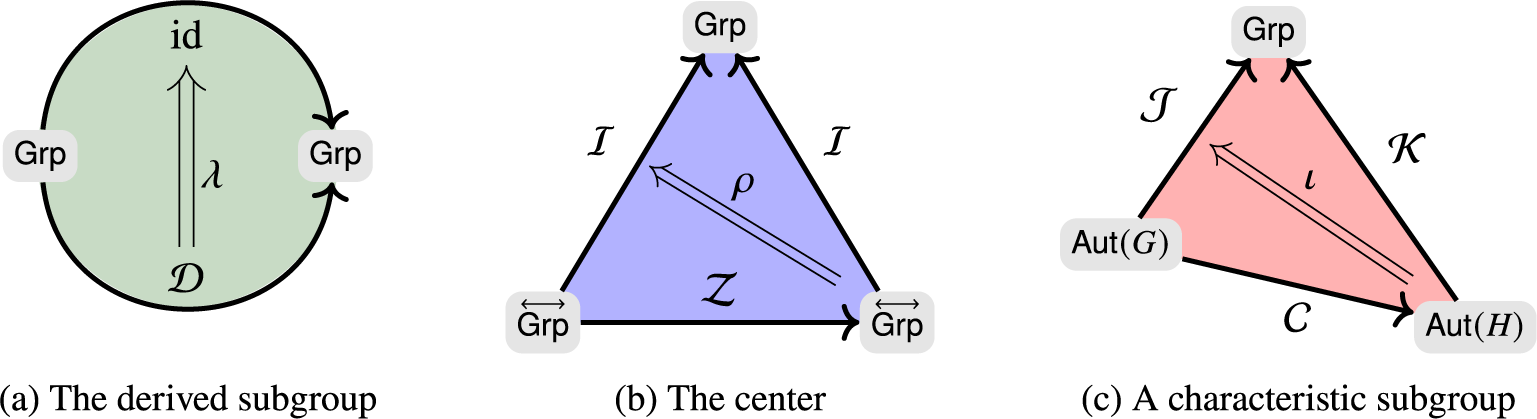

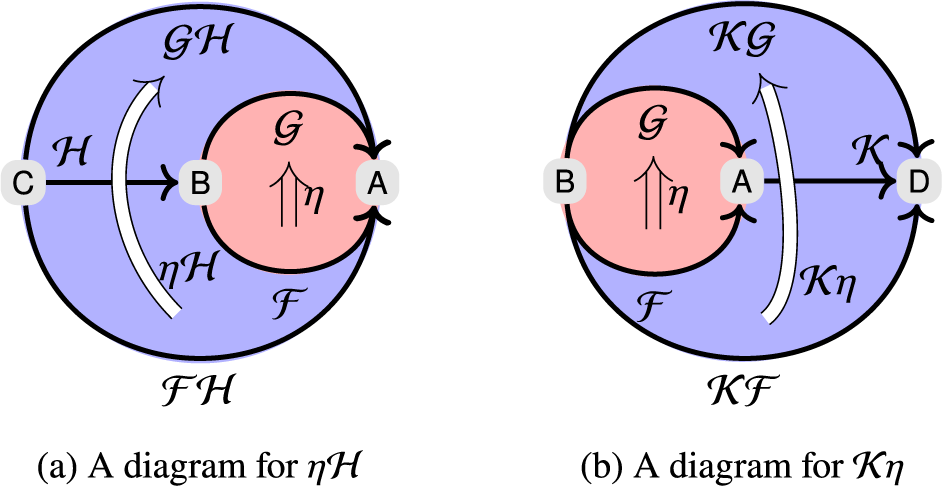

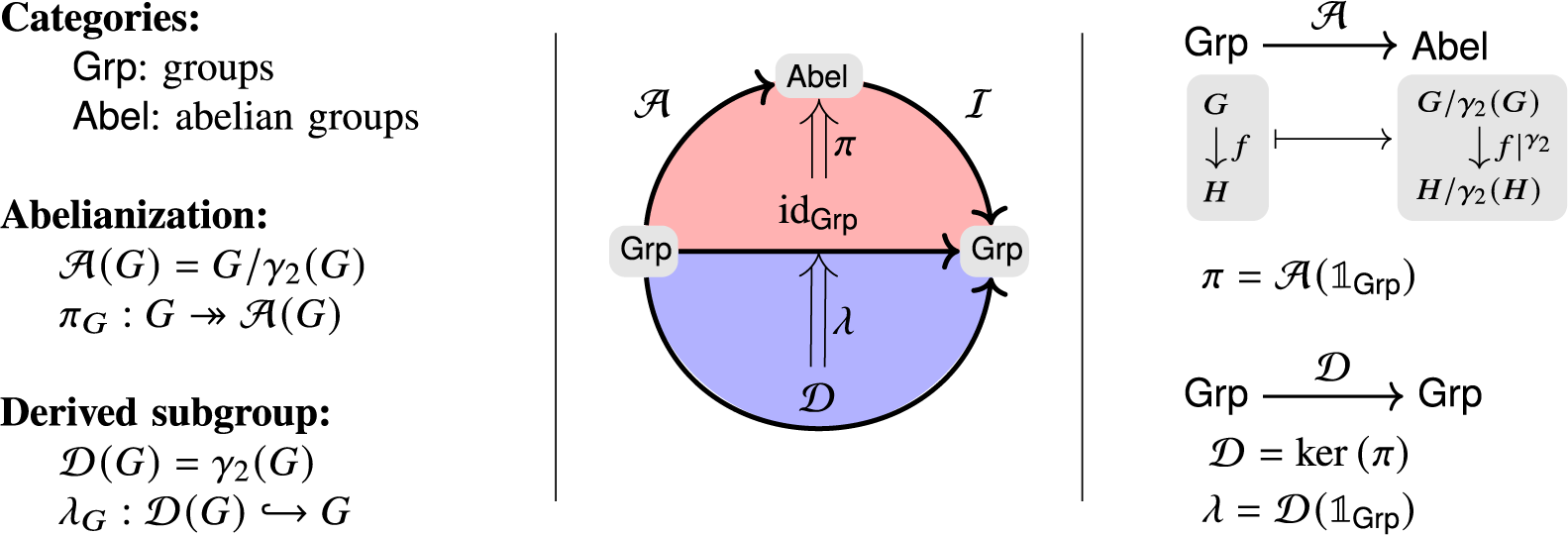

Example 1.4. The derived subgroup

![]() $\gamma _2(G)$

of a group G determines the inclusion homomorphism

$\gamma _2(G)$

of a group G determines the inclusion homomorphism

![]() $\lambda _G:\gamma _2(G)\hookrightarrow G$

and a functor

$\lambda _G:\gamma _2(G)\hookrightarrow G$

and a functor

![]() $\mathcal {D} : \mathsf {Grp} \to \mathsf {Grp}$

mapping groups to their derived subgroup and mapping homomorphisms to their restriction onto the derived subgroups. For every group homomorphism

$\mathcal {D} : \mathsf {Grp} \to \mathsf {Grp}$

mapping groups to their derived subgroup and mapping homomorphisms to their restriction onto the derived subgroups. For every group homomorphism

![]() $\varphi : G \to H$

, observe that

$\varphi : G \to H$

, observe that

![]() $\lambda _H\mathcal {D}(\varphi ) = \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {Grp}}(\varphi )\lambda _G$

, so

$\lambda _H\mathcal {D}(\varphi ) = \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {Grp}}(\varphi )\lambda _G$

, so

![]() $\lambda : \mathcal {D} \Rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {Grp}}$

is a natural transformation.

$\lambda : \mathcal {D} \Rightarrow \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{\mathsf {Grp}}$

is a natural transformation.

The center

![]() $\zeta (G)$

of G yields the inclusion homomorphism

$\zeta (G)$

of G yields the inclusion homomorphism

![]() $\rho _G:\zeta (G)\hookrightarrow G$

. To define a functor with object map

$\rho _G:\zeta (G)\hookrightarrow G$

. To define a functor with object map

![]() $G\mapsto \zeta (G)$

, we must restrict the type of homomorphisms between groups since homomorphisms need not map centers to centers. (Consider, e.g., an embedding

$G\mapsto \zeta (G)$

, we must restrict the type of homomorphisms between groups since homomorphisms need not map centers to centers. (Consider, e.g., an embedding

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/2\hookrightarrow \text {Sym}(3)$

.) Since every isomorphism maps center to center, we restrict to

$\mathbb {Z}/2\hookrightarrow \text {Sym}(3)$

.) Since every isomorphism maps center to center, we restrict to ![]() , defining a functor

, defining a functor ![]() mapping

mapping

![]() $G\mapsto \zeta (G)$

and mapping each homomorphism to its restriction. If

$G\mapsto \zeta (G)$

and mapping each homomorphism to its restriction. If ![]() is the inclusion functor, then

is the inclusion functor, then

![]() $\rho : \mathcal {I}\mathcal {Z}\Rightarrow \mathcal {I}$

is a natural transformation.

$\rho : \mathcal {I}\mathcal {Z}\Rightarrow \mathcal {I}$

is a natural transformation.

1.3 Applications to computation

Part of the motivation for our work comes from computational challenges that arise in contemporary isomorphism tests in algebra. One of these is to develop new ways to discover characteristic subgroups. Standard constructions – such as the commutator subgroup, the center, and the Fitting subgroup – can be applied to any group. However, these subgroups often contribute little to resolving isomorphism. Many ideas have been introduced to search for new structures; see, for example, [Reference Eick, Leedham-Green and O’Brien7, Reference Brooksbank, O’Brien and Wilson9, Reference Maglione21]. Often these involve detailed computations with individual groups, and their application is ad hoc. Indeed, a primary motivation for this study is to systematize the disparate techniques currently used to search for characteristic subgroups.

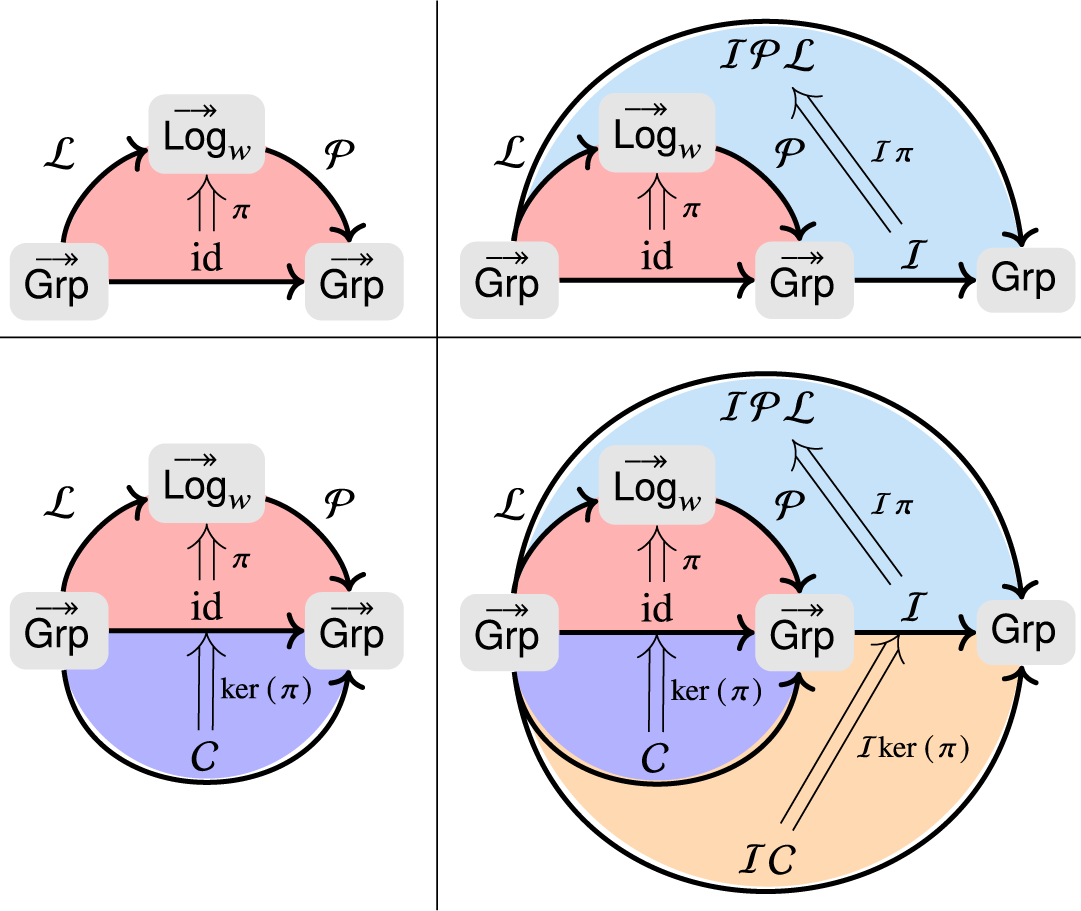

Theorem 2 provides the framework for a systematic search for characteristic subgroups. An

![]() $(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-morphism generalizes the familiar and much studied category theory notion of adjoint functor pairs. We show in Section 4.6 that category actions offer a flexible way to implement the behavior of natural transformations in a computer algebra system. To exploit the full power of the categorical interpretation of characteristic subgroups, we work in a suitably general algebraic framework that allows a seamless transfer of information from one category to another. The familiar examples from Sections 7 and 8 demonstrate how to identify characteristic structure in a category and transfer it back to groups.

$(\mathsf {A},\mathsf {B})$

-morphism generalizes the familiar and much studied category theory notion of adjoint functor pairs. We show in Section 4.6 that category actions offer a flexible way to implement the behavior of natural transformations in a computer algebra system. To exploit the full power of the categorical interpretation of characteristic subgroups, we work in a suitably general algebraic framework that allows a seamless transfer of information from one category to another. The familiar examples from Sections 7 and 8 demonstrate how to identify characteristic structure in a category and transfer it back to groups.

A second challenge concerns reproducibility and comparison of characteristic subgroups. Algorithms to decide isomorphism between groups G and H often, as a first step, generate lists of characteristic subgroups for G and H, respectively. To exploit these lists, any hypothetical isomorphism

![]() $G\to H$

must map the first list to the second (Fact 1.2). We observed in Example 1.3 that it is not always possible to determine a ‘canonical ordering’ of characteristic subgroups such that this is guaranteed. In practice, some constructions employ randomization or make labeling choices that vary from one run to the next. These variations can limit the utility of characteristic subgroups in deciding isomorphism.

$G\to H$

must map the first list to the second (Fact 1.2). We observed in Example 1.3 that it is not always possible to determine a ‘canonical ordering’ of characteristic subgroups such that this is guaranteed. In practice, some constructions employ randomization or make labeling choices that vary from one run to the next. These variations can limit the utility of characteristic subgroups in deciding isomorphism.

Our proposed solution is to develop algorithms that return the natural transformation (or a morphism of biactions) from Theorem 2 instead of the characteristic subgroup itself. This will allow us, in principle, to extend the reach of a specific characteristic subgroup of a given group to an entire category, in much the same way that the commutator subgroup and center behave. The natural transformation can then be applied to a group

![]() $\tilde {G}$

to produce a characteristic subgroup

$\tilde {G}$

to produce a characteristic subgroup

![]() $\tilde {H}$

that corresponds to H in the sense of Fact 1.2: every isomorphism

$\tilde {H}$

that corresponds to H in the sense of Fact 1.2: every isomorphism

![]() $G\to \tilde {G}$

necessarily maps H to

$G\to \tilde {G}$

necessarily maps H to

![]() $\tilde {H}$

, so allowing a meaningful comparison of characteristic subgroups.

$\tilde {H}$

, so allowing a meaningful comparison of characteristic subgroups.

A third challenge is verifiability: in a computer algebra system, subgroups are often given by monomorphisms which are defined on a given generating set. The construction of such a monomorphism usually invokes computations that prove the claimed properties (such as homomorphism or characteristic image). We present our work in a framework that combines these computations, data, and proofs, by employing an intuitionistic Martin-Löf type theory; such a model also allows machine verification of proofs. In this setting, if a computer algebra system returns a counital

![]() $\iota $

, then this counital comes with a “type” that certifies that each morphism

$\iota $

, then this counital comes with a “type” that certifies that each morphism

![]() $\iota _G$

of

$\iota _G$

of

![]() $\iota $

yields a characteristic substructure.

$\iota $

yields a characteristic substructure.

1.4 Structure of this paper

In Section 2, we discuss the required background for our foundations (type theory). In Section 3, we first review varieties of algebraic structures and then show how to model categories as terms of the variety of abstract categories.

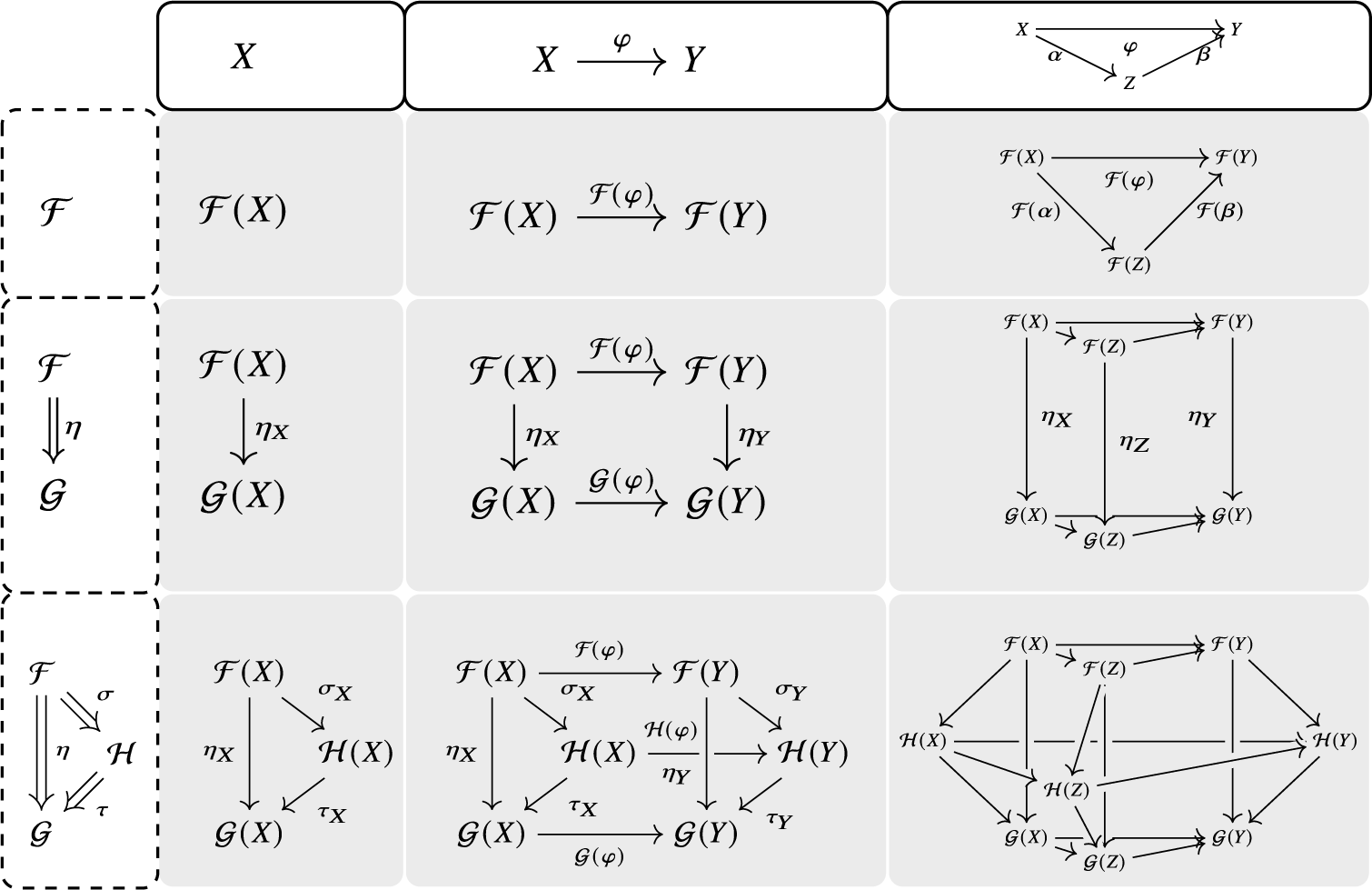

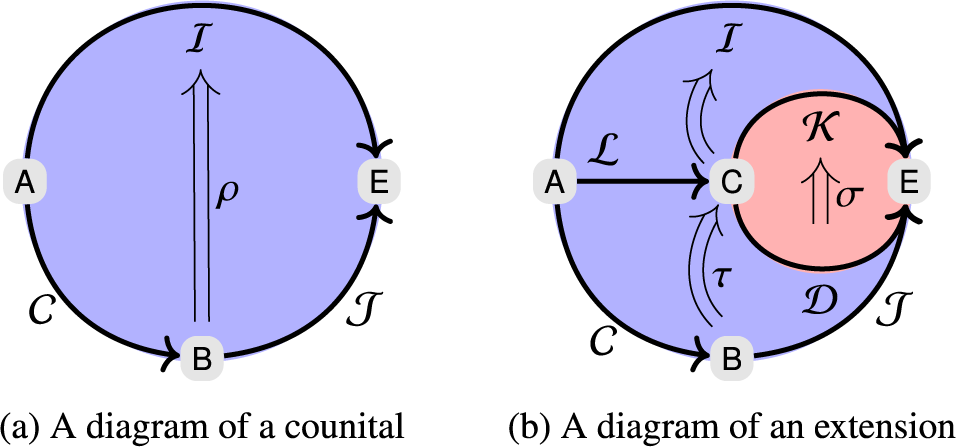

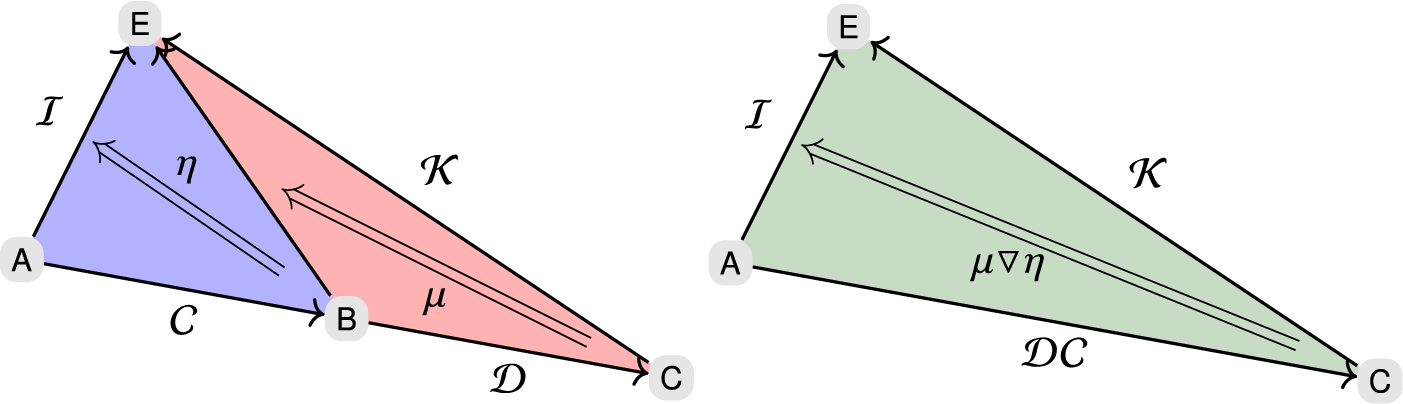

Section 4 studies category actions. In particular, we define capsules (category modules) and describe a computational model for natural transformations as category bimorphisms (Proposition 4.10). This also allows us to describe counitals (Theorem 4.11) and adjoint functor pairs (Theorem 4.13) in the language of bicapsules and bimorphisms.

In Section 5, we explain how characteristic structures can be described by counitals. The functors involved in this construction are defined on categories with one object, but Theorem 5.4 – which we call the Extension Theorem – allows us to extend these functors to larger categories. This theorem is the essential ingredient for proving our main results. We also generalize Theorem 1 to varieties of algebras (Theorem 1-cat).

In Section 6, we generalize Theorem 2 to varieties of algebras (Theorem 2-cat). We show that characteristic substructures can be described as certain counits, and as bimorphism actions on capsules. We also prove the dual version of this result for characteristic quotients (Theorem 2-dual).

In Section 7, we use our framework to provide categorical descriptions of common characteristic subgroups, including verbal and marginal subgroups.

In Section 8, we describe a cross-category translation of counitals and explain, in categorical terms, how a counital for a category of groups can be constructed from a counital for a category of algebras.

In Section 9, we report on an implementation of some of the concepts introduced in this work.

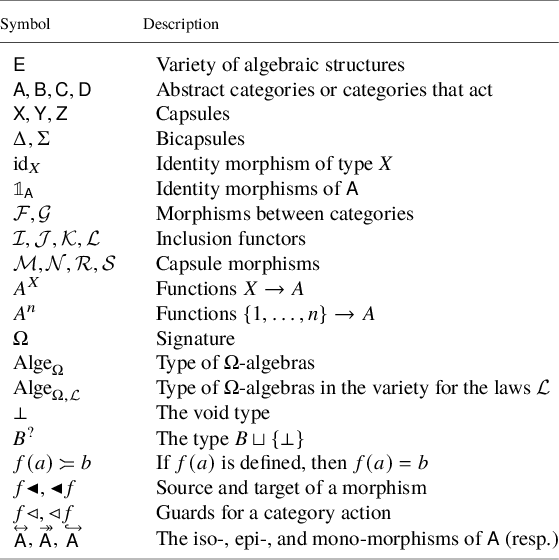

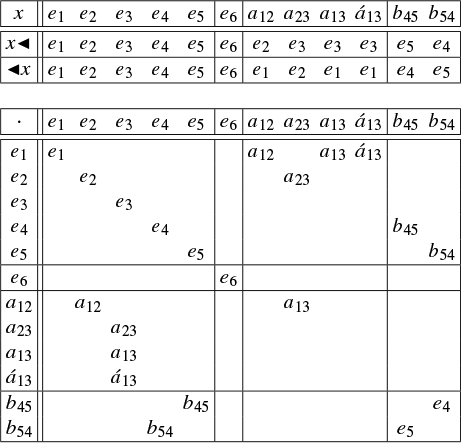

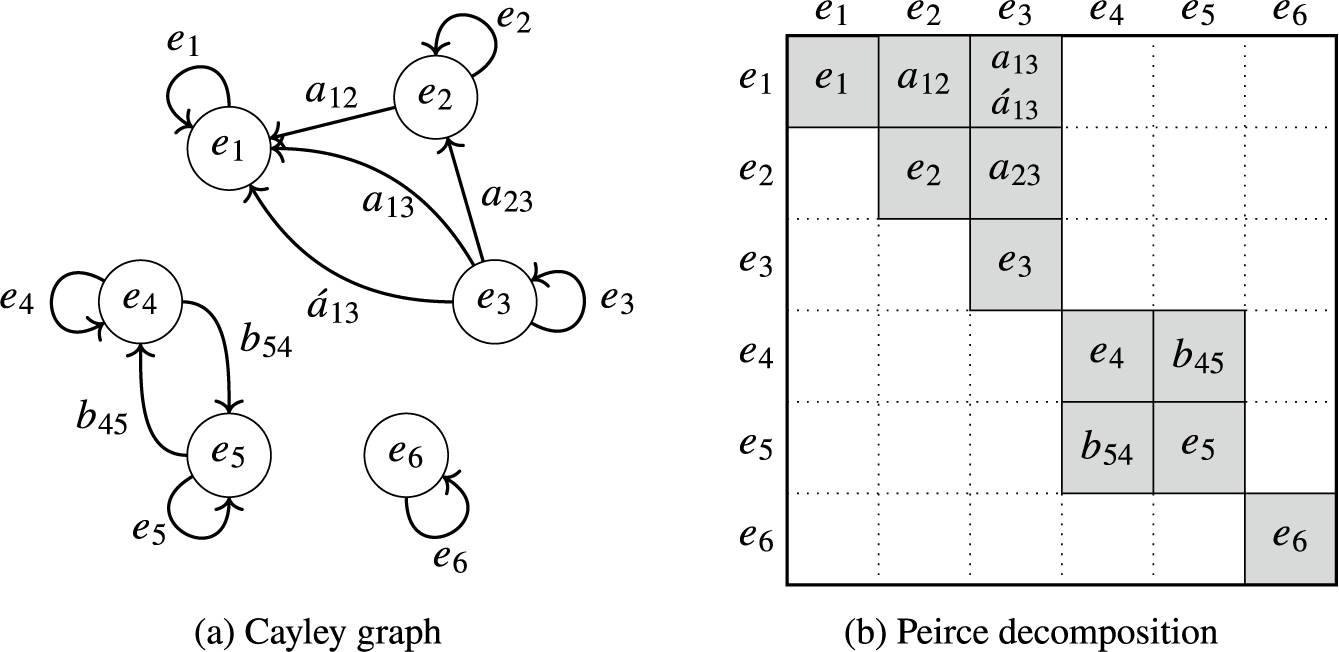

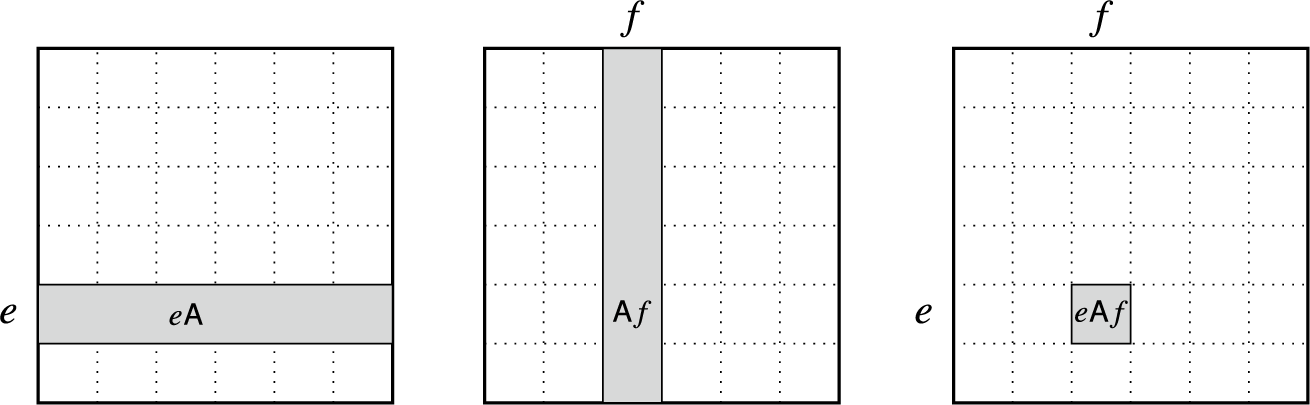

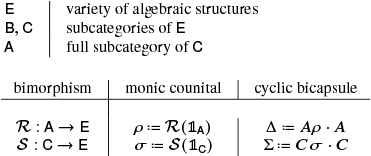

Table 1 summarizes notation used throughout the paper.

Table 1 A guide to notation.

2 Type theory and certifying characteristic structure

The emergence of randomized methods in computational algebra has elevated the significance of certification. Certificates are used to upgrade Monte Carlo algorithms to Las Vegas algorithms, where every output (other than failure) is correct [Reference Holt, Eick and O’Brien12, §3.2.1]. Usually this certification occurs a posteriori, which can present an intractable obstacle. Suppose an algorithm constructs a characteristic subgroup H of a group G with inclusion

![]() $\iota \colon H\hookrightarrow G$

. To certify that H is characteristic, we must verify that

$\iota \colon H\hookrightarrow G$

. To certify that H is characteristic, we must verify that

An obstacle to certification is that the algorithm may not know

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

explicitly. The very construction of

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

explicitly. The very construction of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

is often one of the key reasons to find characteristic subgroups in the first place. What is needed is a priori certification.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

is often one of the key reasons to find characteristic subgroups in the first place. What is needed is a priori certification.

Of course, certain constructions yield subgroups of G which are guaranteed to be characteristic; these include

![]() $\zeta (G)$

and

$\zeta (G)$

and

![]() $\gamma _2(G)$

. Their constructions, and the reasons they produce characteristic subgroups, apply to all groups. A careful examination of these reasons on the categorical level leads to the key insight of this paper: there is a uniform categorical description of the characteristic property. As we shall see, this insight ultimately leads to the possibility of a priori certification.

$\gamma _2(G)$

. Their constructions, and the reasons they produce characteristic subgroups, apply to all groups. A careful examination of these reasons on the categorical level leads to the key insight of this paper: there is a uniform categorical description of the characteristic property. As we shall see, this insight ultimately leads to the possibility of a priori certification.

To put this into practice, we develop a constructive version of our main results using type theory language. Specifically, we use an intuitionistic Martin-Löf type theory (MLTT), a model of computation capable of expressing aspects of proofs that can be machine verified. An advantage of this approach is that certificate data can be verified by practical type-checkers. An MLTT employs the “propositions as types” paradigm (Curry–Howard Correspondence), where types correspond to propositions and terms are programs that correspond to proofs. The remainder of this section is a concise treatment of type theory from [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, Chapters 10–13], [34, Chapter 3].

2.1 Types

Informally, types annotate data by signaling which syntax rules apply to the data. We write

![]() $a:A$

and say “a is a term of type A” or “a inhabits A”. For example,

$a:A$

and say “a is a term of type A” or “a inhabits A”. For example,

![]() $a: \mathbb {N}$

signals that a can only be used as a natural number. A type A is inhabited if there exists at least one term

$a: \mathbb {N}$

signals that a can only be used as a natural number. A type A is inhabited if there exists at least one term

![]() $a:A$

and uninhabited if no term of type A exists. The void type

$a:A$

and uninhabited if no term of type A exists. The void type

![]() $\bot $

has no inhabitants by definition. Deciding whether a type is inhabited or not is computationally undecidable [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, pp. 66–67]. Therefore, in computational settings, types are permitted to be neither inhabited nor uninhabited. Type annotations enable us to use symbols according to their logical purpose; for example,

$\bot $

has no inhabitants by definition. Deciding whether a type is inhabited or not is computationally undecidable [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, pp. 66–67]. Therefore, in computational settings, types are permitted to be neither inhabited nor uninhabited. Type annotations enable us to use symbols according to their logical purpose; for example,

![]() $a:A$

is analogous to

$a:A$

is analogous to

![]() $a\in A$

, but type theories do not have the axioms of set theory.

$a\in A$

, but type theories do not have the axioms of set theory.

Types are introduced from two sources. Some are predefined by the context: they are given a priori, such as the type of natural numbers

![]() $\mathbb {N}$

. Others are created using type-builders: these construct new types from existing ones. We use both

$\mathbb {N}$

. Others are created using type-builders: these construct new types from existing ones. We use both

![]() $A\to B$

and

$A\to B$

and

![]() $B^{A}$

to denote the type of functions, and set

$B^{A}$

to denote the type of functions, and set

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Dom}} (A\to B) = A$

and

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Dom}} (A\to B) = A$

and

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Codom}} (A\to B) = B$

. If n is a natural number, then an inhabitant of type

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Codom}} (A\to B) = B$

. If n is a natural number, then an inhabitant of type

![]() $A^n$

can be interpreted as an n-tuple

$A^n$

can be interpreted as an n-tuple

![]() $(a_1,\ldots ,a_n)$

with each

$(a_1,\ldots ,a_n)$

with each

![]() $a_i: A$

, or alternatively as a function

$a_i: A$

, or alternatively as a function

![]() $\{1,\ldots ,n\}\to A$

. There is a unique function

$\{1,\ldots ,n\}\to A$

. There is a unique function

![]() $\bot \to A$

(akin to the uniqueness of a function

$\bot \to A$

(akin to the uniqueness of a function

![]() $\varnothing \to A$

), so

$\varnothing \to A$

), so

![]() $A^0$

is a type with a single inhabitant – it is not void.

$A^0$

is a type with a single inhabitant – it is not void.

The notation

![]() $\prod _{i: I}A_i$

together with projection maps

$\prod _{i: I}A_i$

together with projection maps

![]() $\pi _i: \left (\prod _{i: I}A_i\right ) \to A_i$

is used for Cartesian products, and

$\pi _i: \left (\prod _{i: I}A_i\right ) \to A_i$

is used for Cartesian products, and

![]() $\bigsqcup _{i: I} A_i$

together with inclusion maps

$\bigsqcup _{i: I} A_i$

together with inclusion maps

![]() $\iota _i : A_i \to \bigsqcup _{i: I} A_i$

is used for disjoint unions. (The tradition in type theory is to use

$\iota _i : A_i \to \bigsqcup _{i: I} A_i$

is used for disjoint unions. (The tradition in type theory is to use

![]() $\sum _{i: I}A_i$

instead of

$\sum _{i: I}A_i$

instead of

![]() $\bigsqcup _{i: I} A_i$

, but this conflicts with algebraic uses of

$\bigsqcup _{i: I} A_i$

, but this conflicts with algebraic uses of

![]() $\Sigma $

.)

$\Sigma $

.)

2.2 Propositions as types

In set theory, propositions are part of the existing foundations. In type theory, propositions coevolve with the theory as special types. A proposition P in logic is associated to a type

![]() $\hat {P}:\mathrm {Type}$

. (Only in this section do we distinguish propositions P in logic from propositions as types with the notation

$\hat {P}:\mathrm {Type}$

. (Only in this section do we distinguish propositions P in logic from propositions as types with the notation

![]() $\hat {P}$

.) If the type

$\hat {P}$

.) If the type

![]() $\hat {P}$

is inhabited by data

$\hat {P}$

is inhabited by data

![]() $p:\hat {P}$

, then the term p is regarded as a proof that P is true. For example, an implication

$p:\hat {P}$

, then the term p is regarded as a proof that P is true. For example, an implication

![]() $P \Rightarrow Q$

(here

$P \Rightarrow Q$

(here

![]() $\Rightarrow $

means “implies” with weakening and contraction laws) can be proved by means of a function

$\Rightarrow $

means “implies” with weakening and contraction laws) can be proved by means of a function

![]() $f:\hat {P}\to \hat {Q}$

, where

$f:\hat {P}\to \hat {Q}$

, where

![]() $\hat {P}$

and

$\hat {P}$

and

![]() $\hat {Q}$

are the respective types associated with P and Q, because it suffices to assume P and derive a proof of Q. Likewise, if we assume that there is a term

$\hat {Q}$

are the respective types associated with P and Q, because it suffices to assume P and derive a proof of Q. Likewise, if we assume that there is a term

![]() $p:\hat {P}$

and apply the function f, then it produces a term

$p:\hat {P}$

and apply the function f, then it produces a term

![]() $f(p):\hat {Q}$

.

$f(p):\hat {Q}$

.

In classical logic, it is only the existence of a proof for a proposition that is relevant. Analogously, in type theory,

![]() $\hat {P}:\mathrm {Type}$

is a mere proposition, written

$\hat {P}:\mathrm {Type}$

is a mere proposition, written

![]() $\hat {P}:\mathrm {Prop}$

, if it has at most one inhabitant.

$\hat {P}:\mathrm {Prop}$

, if it has at most one inhabitant.

Consider the function

![]() $\hat {P}:A\to \mathrm {Prop}$

. Now

$\hat {P}:A\to \mathrm {Prop}$

. Now

![]() $(\forall a\in A)(P(a))$

and

$(\forall a\in A)(P(a))$

and

![]() $(\exists a\in A)(P(a))$

are expressed by terms of type

$(\exists a\in A)(P(a))$

are expressed by terms of type

![]() $\prod _{a:A}\hat {P}_a:\mathrm {Prop}$

and

$\prod _{a:A}\hat {P}_a:\mathrm {Prop}$

and

![]() $\|\bigsqcup _{a:A} \hat {P}_a\|:\mathrm {Prop}$

, respectively, where

$\|\bigsqcup _{a:A} \hat {P}_a\|:\mathrm {Prop}$

, respectively, where

![]() $\|A\|$

truncates a type to a single term if it has any terms [34, §3.7]. The negation of a proposition P is

$\|A\|$

truncates a type to a single term if it has any terms [34, §3.7]. The negation of a proposition P is ![]() , which accords with functions of type

, which accords with functions of type

![]() $\hat {P}\to \bot $

. For additional details, see [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, Chapters 12–13], [34, Chapter 3].

$\hat {P}\to \bot $

. For additional details, see [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, Chapters 12–13], [34, Chapter 3].

2.3 Equality

In Zermelo set theories, all data are sets and there is a single notion of equality afforded by the Axiom of extensionality: two sets are equal if, and only if, they have the same elements. In type theory, terms and types are separate entities, and this single axiom is replaced by several distinct notions of equality more representative of computational behavior. Each type theory is built on a rewriting system (such as a

![]() $\lambda $

-calculus or combinatory logic). Employing the language of [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, §1D and §2D], we judge data as equal if their normal forms in this rewriting system coincide; and

$\lambda $

-calculus or combinatory logic). Employing the language of [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, §1D and §2D], we judge data as equal if their normal forms in this rewriting system coincide; and ![]() followed by some sentences M means that “within the given scope M, the variable s should be substituted by the data t”.

followed by some sentences M means that “within the given scope M, the variable s should be substituted by the data t”.

Type theories include axioms that allow equality after taking normal forms to count as (

![]() $definitional$

) equality–the type theory sees no difference between the data [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, p. 193]. For example, if we build the type

$definitional$

) equality–the type theory sees no difference between the data [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, p. 193]. For example, if we build the type

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/n$

which depends on a term

$\mathbb {Z}/n$

which depends on a term

![]() $n:\mathbb {N}$

, then some type systems judge that

$n:\mathbb {N}$

, then some type systems judge that

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/(m+m)$

is equal to

$\mathbb {Z}/(m+m)$

is equal to

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/2m$

because

$\mathbb {Z}/2m$

because

![]() $m+m$

and

$m+m$

and

![]() $2m$

have the same normal form. But the function

$2m$

have the same normal form. But the function

![]() $\gcd (m,2m)$

is more complicated and its normal form may differ from m. Hence, the type system does not judge

$\gcd (m,2m)$

is more complicated and its normal form may differ from m. Hence, the type system does not judge

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/\gcd (m,2m)$

as equal to

$\mathbb {Z}/\gcd (m,2m)$

as equal to

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/m$

; neither does it assert they are not equal; instead it withholds judgment.

$\mathbb {Z}/m$

; neither does it assert they are not equal; instead it withholds judgment.

To construct an equality that mimics set theory, Per Martin-Löf developed a notion of propositional equality that imitates the Leibniz Law [Reference Feldman13]:

where

![]() $P(x)$

runs over all predicates of a single variable x. For every type A and terms

$P(x)$

runs over all predicates of a single variable x. For every type A and terms

![]() $s,t:A$

, we define an auxiliary type

$s,t:A$

, we define an auxiliary type

![]() $s=_A t$

, where terms are proofs that s equals t, with the rule that, given a function

$s=_A t$

, where terms are proofs that s equals t, with the rule that, given a function

![]() $f:A\to B$

, there is a function

$f:A\to B$

, there is a function

For example, a proof

![]() $p: (\gcd (m,2m) =_{\mathbb {N}} m)$

can be transported along a path to

$p: (\gcd (m,2m) =_{\mathbb {N}} m)$

can be transported along a path to

![]() $q: (\mathbb {Z}/\gcd (m,2m) =_{\mathbb {Z}/m} \mathbb {Z}/m)$

allowing programs to treat these types as equal. Thus, computational evidence enhances the reach of equality, see [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, §3.5], [34].

$q: (\mathbb {Z}/\gcd (m,2m) =_{\mathbb {Z}/m} \mathbb {Z}/m)$

allowing programs to treat these types as equal. Thus, computational evidence enhances the reach of equality, see [Reference Hindley and Seldin18, §3.5], [34].

For readability we often omit the subscript A in

![]() $s=_A t$

. By slight abuse of notation, writing “

$s=_A t$

. By slight abuse of notation, writing “

![]() $s=t$

” as a logical statement in text should be interpreted as “the type

$s=t$

” as a logical statement in text should be interpreted as “the type

![]() $s=_At$

is inhabited”.

$s=_At$

is inhabited”.

2.4 Subtypes and inclusion functions

Sets are a special case of types: we write

![]() $S:\mathrm {Set}$

for a type S if the type

$S:\mathrm {Set}$

for a type S if the type

![]() $s=_S t$

is a mere proposition for all

$s=_S t$

is a mere proposition for all

![]() $s,t:S$

. Let A be a type. If

$s,t:S$

. Let A be a type. If

![]() $P : A \to \mathrm {Prop}$

, then

$P : A \to \mathrm {Prop}$

, then

is the subtype of A defined by P. We also write this as ![]() . Terms of type B have the form

. Terms of type B have the form

![]() $\langle a, p\rangle $

for

$\langle a, p\rangle $

for

![]() $a:A$

and

$a:A$

and

![]() $p:\mathrm {Prop}$

, where p is a proof that

$p:\mathrm {Prop}$

, where p is a proof that

![]() $P(a)$

is inhabited. We sometimes use set theory notation to improve readability when describing a subtype. For more details, see [34, §3.5]. For a typed function

$P(a)$

is inhabited. We sometimes use set theory notation to improve readability when describing a subtype. For more details, see [34, §3.5]. For a typed function

![]() $f:A\to B$

, the image

$f:A\to B$

, the image

![]() $\{f(a)\mid a:A\}$

is shorthand for

$\{f(a)\mid a:A\}$

is shorthand for

![]() $\{b:B\mid (\exists a:A)(f(a)=b)\}$

.

$\{b:B\mid (\exists a:A)(f(a)=b)\}$

.

Subtypes have an associated inclusion function

![]() $\alpha :B\to A$

where

$\alpha :B\to A$

where ![]() . A subtlety is that if

. A subtlety is that if

![]() $C\subset B$

with inclusion map

$C\subset B$

with inclusion map

![]() $\beta :C\to B$

, then the composition

$\beta :C\to B$

, then the composition

![]() $\alpha \beta :C\to A$

is injective but does not show directly that

$\alpha \beta :C\to A$

is injective but does not show directly that

![]() $C\subset A$

. A term of type

$C\subset A$

. A term of type ![]() , with

, with

![]() $Q : B\to \mathrm {Prop}$

, has the form

$Q : B\to \mathrm {Prop}$

, has the form

![]() $\langle \langle a,p\rangle ,q\rangle $

, which differs from terms of type B. A small modification addresses the fact that the relation

$\langle \langle a,p\rangle ,q\rangle $

, which differs from terms of type B. A small modification addresses the fact that the relation

![]() $\subset $

is not strictly transitive. Define a subtype

$\subset $

is not strictly transitive. Define a subtype ![]() , where

, where ![]() , and inclusion

, and inclusion

![]() $\gamma : C' \to A$

. Now construct a map

$\gamma : C' \to A$

. Now construct a map

![]() $\sigma : C\to C'$

given by

$\sigma : C\to C'$

given by

where

![]() $a:A$

and

$a:A$

and

![]() $\langle p,q\rangle : R(a)$

. Thus,

$\langle p,q\rangle : R(a)$

. Thus,

![]() $\alpha \beta =\gamma \sigma $

, and the composition

$\alpha \beta =\gamma \sigma $

, and the composition

![]() $\alpha \beta $

is equivalent to

$\alpha \beta $

is equivalent to

![]() $\gamma $

. Hence,

$\gamma $

. Hence,

![]() $\subset $

is transitive up to this equivalence.

$\subset $

is transitive up to this equivalence.

2.5 Partial functions

In type theory, functions are ultimately programs so they may fail to halt. Since our concern lies with algebraic obstacles rather than decidability, we confine our model to algebras that have decidable operations, such as polynomial and integer operations, look-up tables, and strongly normalizing rewriting systems. Thus, all functions are total: given an input, they produce an output. However, it is helpful to identify inputs we regard as “undefined,” or “leading to errors.” For example, a division operator may allow

![]() $0$

as an input and return an error token as output. We call such functions partial functions and regard them as “undefined” at such inputs.

$0$

as an input and return an error token as output. We call such functions partial functions and regard them as “undefined” at such inputs.

To accommodate such partial operations, we extend types by adjoining the symbol

![]() $\bot $

(the void type) to represent “undefined”. For a type A, we define

$\bot $

(the void type) to represent “undefined”. For a type A, we define

with inclusion

![]() $\iota _A:A\hookrightarrow A^?$

. For

$\iota _A:A\hookrightarrow A^?$

. For

![]() $a:A^?$

, we write

$a:A^?$

, we write

![]() $a:A$

in this setting as shorthand for “there exists

$a:A$

in this setting as shorthand for “there exists

![]() $a':A$

such that

$a':A$

such that

![]() $a=\iota _A(a')$

.” This allows us to define an endofunctor Q on the category of types that maps a morphism

$a=\iota _A(a')$

.” This allows us to define an endofunctor Q on the category of types that maps a morphism

![]() $f:A\to B$

to

$f:A\to B$

to

![]() $f^?:A^?\to B^?$

, such that

$f^?:A^?\to B^?$

, such that

![]() $f^?(a)=f(a)$

for

$f^?(a)=f(a)$

for

![]() $a:A$

and

$a:A$

and

![]() $f^?(\bot )=\bot $

. The canonical projection

$f^?(\bot )=\bot $

. The canonical projection

![]() $\mu : QQ \Rightarrow Q$

, with components

$\mu : QQ \Rightarrow Q$

, with components

![]() $\mu _A: (A^?)^? \to A?$

, is a natural isomorphism. Hence, it suffices to work with single applications of Q, and

$\mu _A: (A^?)^? \to A?$

, is a natural isomorphism. Hence, it suffices to work with single applications of Q, and

![]() $\bot $

will serve as the designated symbol for undefined elements throughout.

$\bot $

will serve as the designated symbol for undefined elements throughout.

This discussion also motivates a notion of “directional equality” similar to that in [Reference Freyd and Scedrov14, 1.12]. For

![]() $a,b: A^?$

, define

$a,b: A^?$

, define

By slight abuse of notation, for function terms

![]() $f,g : A^?\to B^?$

we denote function extensionality also by

$f,g : A^?\to B^?$

we denote function extensionality also by

![]() $f=g$

, that is, we define

$f=g$

, that is, we define

2.6 Certifying that the trivial group is characteristic

As an illustration, we present a type verifying the characteristic property of the trivial subgroup. Let

![]() $G : \mathrm {Group}$

be a group with identity

$G : \mathrm {Group}$

be a group with identity

![]() $1:G$

. Let

$1:G$

. Let ![]() be the subtype of G representing the trivial subgroup. Recall that terms of H have the form

be the subtype of G representing the trivial subgroup. Recall that terms of H have the form

![]() $\langle x, p\rangle $

, where

$\langle x, p\rangle $

, where

![]() $x:G$

and p is a term of type

$x:G$

and p is a term of type

![]() $x=1$

, and there is a map

$x=1$

, and there is a map

![]() $\iota :H\to G$

,

$\iota :H\to G$

,

![]() $\langle x,p\rangle \mapsto x$

. If

$\langle x,p\rangle \mapsto x$

. If

![]() $h,k:H$

, then

$h,k:H$

, then

![]() $\iota (h)=\iota (k)=1$

, and, by (2.2), for every

$\iota (h)=\iota (k)=1$

, and, by (2.2), for every

![]() $\varphi :\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

there is an invertible function of type

$\varphi :\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

there is an invertible function of type

The latter function depends on h and k, but we suppress this dependency to simplify the exposition. Let

![]() $\mathrm {idLaw}(\varphi ) : \varphi (1)=_{G} 1$

be a proof that

$\mathrm {idLaw}(\varphi ) : \varphi (1)=_{G} 1$

be a proof that

![]() $\varphi :\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

fixes

$\varphi :\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

fixes

![]() $1:G$

. Using (2.5), we define the term

$1:G$

. Using (2.5), we define the term

$$\begin{align*}\mathrm{idMap}(\varphi) : \prod_{h:H}\left\|\bigsqcup_{k:H} \varphi(\iota(h)) =_G \iota(k)\right\| \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\mathrm{idMap}(\varphi) : \prod_{h:H}\left\|\bigsqcup_{k:H} \varphi(\iota(h)) =_G \iota(k)\right\| \end{align*}$$

that takes as input

![]() $h:H$

and produces

$h:H$

and produces

![]() $\langle 1,\mathrm {idLaw}(\varphi )\rangle : \left \|\bigsqcup _{k:H} \varphi (\iota (h))=_G \iota (k)\right \|$

. Therefore we obtain the term

$\langle 1,\mathrm {idLaw}(\varphi )\rangle : \left \|\bigsqcup _{k:H} \varphi (\iota (h))=_G \iota (k)\right \|$

. Therefore we obtain the term

$$ \begin{align*} \mathrm{idMap} & : \prod_{\varphi:\operatorname{\mathrm{Aut}}(G)}\prod_{h:H}\left\|\bigsqcup_{k:H} \varphi(\iota(h))=_G \iota(k)\right\|, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathrm{idMap} & : \prod_{\varphi:\operatorname{\mathrm{Aut}}(G)}\prod_{h:H}\left\|\bigsqcup_{k:H} \varphi(\iota(h))=_G \iota(k)\right\|, \end{align*} $$

which certifies that H is characteristic in G; compare to (2.1). Recall that in MLTT, types correspond to propositions, and terms are programs that correspond to proofs. Thus, the term

![]() $\mathrm {idMap}$

is not an exhaustive tuple listing

$\mathrm {idMap}$

is not an exhaustive tuple listing

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

, but a program (function) that takes as input

$\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

, but a program (function) that takes as input

![]() $\varphi :\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

and

$\varphi :\operatorname {\mathrm {Aut}}(G)$

and

![]() $h:H$

, and produces

$h:H$

, and produces

![]() $k:H$

and

$k:H$

and

![]() $p: \varphi (\iota (h)) =_G \iota (k)$

.

$p: \varphi (\iota (h)) =_G \iota (k)$

.

3 Algebraic structures and varieties

To interpret characteristic structure as computable categorical information, we treat categories as algebraic structures. (Computational categories should not be confused with categorical semantics of computation.) For our purpose, it suffices to use operations that may only be partially defined, so categories are important examples, as are monoids, groups, groupoids, rings, and nonassociative algebras. We give an abridged account and refer to [Reference Cohn10, §II.2], [Reference Adámek and Rosický1, Chapter 3] for details.

3.1 Intentional and extensional formulations of algebra

It is natural to ask if algebraic structures such as groups and rings, that are introduced in standard texts such as [Reference Hungerford19] using extensional set theory, have logically consistent intentional formulations in foundations such as MLTT. While it is not within our purview to consider alternative foundations of algebra, we briefly compare type-theoretic formulations of groups with their long-standing and rigorous treatment in computational algebra.

Although systems such as GAP [15], Macauley [Reference Grayson, Stillman and Eisenbud16], Magma [Reference Bosma, Cannon and Playoust8], and SageMath [31] are not designed to use types robustly, they nevertheless facilitate a treatment of groups that is more intentional than extensional. In these systems, groups can be represented in many different ways, but for practical reasons they are generally not treated as sets of elements. For instance, a group G may be specified by a generating set Y of permutations. Algorithms such as the product replacement [Reference Holt, Eick and O’Brien12, §3.2.2] can then be used to select “random” elements of G as words in Y. However, basic questions such as membership – does a permutation belong to G? – often require clever algorithms to answer [Reference Holt, Eick and O’Brien12, Chapter 4].

Even the question of whether two elements in a group are equal is often not immediate. (There are models, such as finitely presented groups, where this question is not decidable.) In standard models for computation with groups, effective equality testing is usually available, but it is not always done by simply asking if two pieces of data are identical. For example, do elements a and b of

![]() $G=\langle Y\rangle $

coincide in

$G=\langle Y\rangle $

coincide in

![]() $G / \zeta (G)$

? Equivalently, is

$G / \zeta (G)$

? Equivalently, is

![]() $ab^{-1} \in \zeta (G)$

? Even if we do not know generators for

$ab^{-1} \in \zeta (G)$

? Even if we do not know generators for

![]() $\zeta (G)$

, we can answer the latter question efficiently by deciding whether

$\zeta (G)$

, we can answer the latter question efficiently by deciding whether

![]() $ab^{-1}$

commutes with every element of Y. In this sense, asking whether

$ab^{-1}$

commutes with every element of Y. In this sense, asking whether

![]() $a=b$

in computational algebra (where a program settles the question) is closer to writing

$a=b$

in computational algebra (where a program settles the question) is closer to writing

![]() $a=b$

in type theory (where evidence is provided by a proof) than it is to the (trivial) question in set theory (cf. Section 2.3).

$a=b$

in type theory (where evidence is provided by a proof) than it is to the (trivial) question in set theory (cf. Section 2.3).

3.2 Operators, grammars, and signatures

Informally, a grammar is a description of rules for formulas.

Definition 3.1. An operator is a symbol with a grammar, which we describe using the Backus–Naur Form (BNF) [Reference Pierce26, p. 24]. The valence of an operator

![]() $\omega $

, written

$\omega $

, written

![]() $|\omega |$

, is the number of parameters in its grammar. A set

$|\omega |$

, is the number of parameters in its grammar. A set

![]() $\Omega $

of operators is a signature.

$\Omega $

of operators is a signature.

Example 3.2. A signature for additive formulas specifies three operators:

The bivalent addition

![]() $(+)$

depends on terms to the left and right; zero (

$(+)$

depends on terms to the left and right; zero (

![]() $0$

) depends on nothing; and univalent negation (

$0$

) depends on nothing; and univalent negation (

![]() $-$

) is followed by a term.

$-$

) is followed by a term.

It is easy to reject

![]() $+-+\,2\,3\,7$

since it is not meaningful. However, we might write

$+-+\,2\,3\,7$

since it is not meaningful. However, we might write

![]() $2+3-7$

intending

$2+3-7$

intending

![]() $(2+3)+(-7)$

; the BNF grammar <Add> accepts only the latter.

$(2+3)+(-7)$

; the BNF grammar <Add> accepts only the latter.

The purpose of the signature is to formulate important algebraic concepts such as homomorphisms. To declare that a function

![]() $f:A\to B$

is a homomorphism between additive groups, we use the signature of Example 3.2 as follows:

$f:A\to B$

is a homomorphism between additive groups, we use the signature of Example 3.2 as follows:

3.3 Algebraic structures

An algebra is a single type with a signature [Reference Cohn10, §II.2].

Definition 3.3. An algebraic structure with signature

![]() $\Omega $

is a type A and a function

$\Omega $

is a type A and a function

![]() $\omega \mapsto \omega _A$

, where

$\omega \mapsto \omega _A$

, where

![]() $\omega :\Omega $

and

$\omega :\Omega $

and

![]() $\omega _A:A^{|\omega |}\to A$

. A homomorphism between algebraic structures A and B, each having signature

$\omega _A:A^{|\omega |}\to A$

. A homomorphism between algebraic structures A and B, each having signature

![]() $\Omega $

, is a function

$\Omega $

, is a function

![]() $f:A\to B$

such that, for every

$f:A\to B$

such that, for every

![]() $\omega :\Omega $

and

$\omega :\Omega $

and

![]() $a_1,\ldots ,a_{|\omega |}:A$

,

$a_1,\ldots ,a_{|\omega |}:A$

,

As in Section 2.2, we extend these propositions to types as follows:

Terms of type

![]() $\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega }$

are

$\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega }$

are

![]() $\Omega $

-algebras.

$\Omega $

-algebras.

For example, consider the additive group signature from Example 3.2. The underlying structure of an additive group can be described by a type (set) A together with assignments of the operators in Add such as (<Add> + <Add>) to

![]() $+_A : A\times A\to A$

. The nullary operator 0 is then identified with a term

$+_A : A\times A\to A$

. The nullary operator 0 is then identified with a term

![]() $0:A$

.

$0:A$

.

3.4 Free algebras and formulas

We now extend signatures to include variables that allow us to work with formulas.

Definition 3.4. Let

![]() $\Omega $

be a signature and let X be a type whose terms are variables. The free

$\Omega $

be a signature and let X be a type whose terms are variables. The free

![]() $\Omega $

-algebra in variables X, denoted by

$\Omega $

-algebra in variables X, denoted by

![]() $\Omega \langle X\rangle $

, is the type of every formula in X constructed using the operators in

$\Omega \langle X\rangle $

, is the type of every formula in X constructed using the operators in

![]() $\Omega $

.

$\Omega $

.

Example 3.5. To describe formulas in variables

![]() $x,y$

and z, we extend the additive signature

$x,y$

and z, we extend the additive signature

![]() $\Omega =\texttt {Add}$

of Example 3.2 as follows:

$\Omega =\texttt {Add}$

of Example 3.2 as follows:

Here,

![]() $x+y$

and

$x+y$

and

![]() $(-x)+(0+z)$

have type

$(-x)+(0+z)$

have type

![]() $\texttt {Add}\langle X\rangle $

, but

$\texttt {Add}\langle X\rangle $

, but

![]() $x-$

and

$x-$

and

![]() $x+7$

do not. The operations on the formulas

$x+7$

do not. The operations on the formulas

![]() $\Phi _1(X),\Phi _2(X):\texttt {Add}\langle X\rangle $

are:

$\Phi _1(X),\Phi _2(X):\texttt {Add}\langle X\rangle $

are:

Thus,

![]() $\texttt {Add}\langle X\rangle $

is the free additive algebra, but it lacks laws such as

$\texttt {Add}\langle X\rangle $

is the free additive algebra, but it lacks laws such as

![]() $x+y = y+x$

and

$x+y = y+x$

and

![]() $x + (-x) = 0$

. We explain how to impose these laws in Section 3.5.

$x + (-x) = 0$

. We explain how to impose these laws in Section 3.5.

Fact 3.6. Let A be an

![]() $\Omega $

-algebra and

$\Omega $

-algebra and

![]() $a:A^X$

, where X is a type whose terms are variables. There is a unique homomorphism

$a:A^X$

, where X is a type whose terms are variables. There is a unique homomorphism

![]() $\mathrm {eval}_a:\Omega \langle X\rangle \to A$

that satisfies

$\mathrm {eval}_a:\Omega \langle X\rangle \to A$

that satisfies

![]() $\mathrm {eval}_a(x) = a_x $

.

$\mathrm {eval}_a(x) = a_x $

.

Consequently, we write ![]() for formulas

for formulas

![]() $\Phi :\Omega \langle X\rangle $

and

$\Phi :\Omega \langle X\rangle $

and

![]() $a:A^X$

.

$a:A^X$

.

Remark 3.7. The construction in Fact 3.6 is categorical in nature, and we use it in Section 7 to construct characteristic subgroups. The category of

![]() $\Omega $

-algebras has objects of type

$\Omega $

-algebras has objects of type

![]() $\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega }$

together with homomorphisms. The pair of functors (given only by their object maps)

$\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega }$

together with homomorphisms. The pair of functors (given only by their object maps)

forms an adjoint functor pair between the categories of types and

![]() $\Omega $

-algebras; see Section 4.5 for related discussion.

$\Omega $

-algebras; see Section 4.5 for related discussion.

3.5 Laws and varieties

Let

![]() $\Omega $

be a signature. We now describe the variety of

$\Omega $

be a signature. We now describe the variety of

![]() $\Omega $

-algebras whose operators satisfy a list of (equational) laws such as the axioms of a group. Let X be a type for variables. A law is a term of type

$\Omega $

-algebras whose operators satisfy a list of (equational) laws such as the axioms of a group. Let X be a type for variables. A law is a term of type

![]() $\Omega \langle X\rangle ^2$

. We index laws by a type L, so they are terms

$\Omega \langle X\rangle ^2$

. We index laws by a type L, so they are terms

![]() $\mathcal {L}: L \to \Omega \langle X\rangle ^2$

and are written

$\mathcal {L}: L \to \Omega \langle X\rangle ^2$

and are written

![]() $\ell \mapsto (\Lambda _{1,\ell }, \Lambda _{2,\ell })$

.

$\ell \mapsto (\Lambda _{1,\ell }, \Lambda _{2,\ell })$

.

An

![]() $\Omega $

-algebra

$\Omega $

-algebra

![]() ${A}$

is in the variety for the laws

${A}$

is in the variety for the laws

![]() $\mathcal {L}: L \to \Omega \langle X\rangle ^2$

if

$\mathcal {L}: L \to \Omega \langle X\rangle ^2$

if

We write

![]() $\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega ,\mathcal {L}}$

for the type of all

$\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega ,\mathcal {L}}$

for the type of all

![]() $\Omega $

-algebras in the variety for the laws

$\Omega $

-algebras in the variety for the laws

![]() $\mathcal {L}$

; this is a subtype of

$\mathcal {L}$

; this is a subtype of

![]() $\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega }$

. The category of

$\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega }$

. The category of

![]() $\Omega $

-algebras in the variety for

$\Omega $

-algebras in the variety for

![]() $\mathcal {L}$

has object type

$\mathcal {L}$

has object type

![]() $\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega ,\mathcal {L}}$

and morphism type

$\mathrm {Alge}_{\Omega ,\mathcal {L}}$

and morphism type

with

![]() $\mathrm {Hom}_{\Omega }(A,B)$

as in Definition 3.3.

$\mathrm {Hom}_{\Omega }(A,B)$

as in Definition 3.3.

Example 3.8. The signature

![]() $\Omega $

for groups is the following:

$\Omega $

for groups is the following:

The variety of groups uses three laws, indexed by ![]() with variables

with variables ![]() , where, for example,

, where, for example,

Thus,

![]() $\Lambda _{1,\texttt {asc}}(g,h,k)=g(hk)$

and

$\Lambda _{1,\texttt {asc}}(g,h,k)=g(hk)$

and

![]() $\Lambda _{2,\texttt {asc}}(g,h,k)=(gh)k$

, and associativity is imposed on the

$\Lambda _{2,\texttt {asc}}(g,h,k)=(gh)k$

, and associativity is imposed on the

![]() $\Omega $

-algebra G by requiring a term (“proof”) of type

$\Omega $

-algebra G by requiring a term (“proof”) of type

$$\begin{align*}\prod_{g:G}\prod_{h:G}\prod_{k:G} g(hk)=_G (gh)k. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\prod_{g:G}\prod_{h:G}\prod_{k:G} g(hk)=_G (gh)k. \end{align*}$$

Encoding

![]() $1x=x$

and

$1x=x$

and

![]() $x^{-1} x=1$

as additional laws gives a complete description of the variety of groups. Laws need not be algebraically independent: for example,

$x^{-1} x=1$

as additional laws gives a complete description of the variety of groups. Laws need not be algebraically independent: for example,

![]() $x1=x$

and

$x1=x$

and

![]() $xx^{-1}=1$

are often also encoded.

$xx^{-1}=1$

are often also encoded.

For clarity, henceforth we write laws as propositions. For example, we write

![]() $g(hk)=(gh)k$

rather than terms of a mere proposition type.

$g(hk)=(gh)k$

rather than terms of a mere proposition type.

3.6 Categories as algebraic structures

We cannot always compose a pair of morphisms in a category: composition may be a partial function. Hence, the morphisms need not form an algebraic structure under composition. We address this limitation by identifying precisely when the operators yield partial functions.

Example 3.9. The type of each function is given as

Technically, to quantify over all types, we shift to a larger universe

![]() $\text {Type}_1$

; see Remark 3.17. For

$\text {Type}_1$

; see Remark 3.17. For

![]() $f:A\to B$

and

$f:A\to B$

and

![]() $g:\mathrm {Fun}$

, define

$g:\mathrm {Fun}$

, define

where

![]() $f\circ g$

is the usual composition of functions. The condition

$f\circ g$

is the usual composition of functions. The condition

![]() $f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }=\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } g$

guards against composing noncomposable functions (one can think of

$f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }=\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } g$

guards against composing noncomposable functions (one can think of

![]() $f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }=\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } g$

as saying “what enters f must match what exits g”). Note that

$f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }=\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } g$

as saying “what enters f must match what exits g”). Note that

![]() $\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } (f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft })=\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{A}=\operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{A}=f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }$

, and similarly

$\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } (f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft })=\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } \operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{A}=\operatorname {\mathrm {id}}_{A}=f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }$

, and similarly

![]() $(\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } f)\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }=\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } f$

.

$(\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } f)\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }=\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } f$

.

The definitions in (3.1) motivate an algebraic structure on

![]() $\mathrm {Fun}^?$

. We define the composition signature:

$\mathrm {Fun}^?$

. We define the composition signature:

Definition 3.10. Let

![]() $\Omega $

be the composition signature of (3.2). An abstract category

$\Omega $

be the composition signature of (3.2). An abstract category

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

is an

$\mathsf {A}$

is an

![]() $\Omega $

-algebra on a type C satisfying the law

$\Omega $

-algebra on a type C satisfying the law

in variables

![]() $f,g,h$

, together with the following source–target laws and

$f,g,h$

, together with the following source–target laws and

![]() $\bot $

-sink laws:

$\bot $

-sink laws:

$$ \begin{align*} \mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} (f\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft}) & = f\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} & (\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} f) f & = f & \mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} (fg) & = \mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} (f (\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} g))\\ (\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} f)\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} & = \mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} f & f (f\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft}) & = f & (fg)\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} & = ((f\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft})g)\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} (f\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft}) & = f\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} & (\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} f) f & = f & \mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} (fg) & = \mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} (f (\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} g))\\ (\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} f)\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} & = \mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} f & f (f\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft}) & = f & (fg)\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} & = ((f\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft})g)\mathbin{\blacktriangleleft} \end{align*} $$

We refer to the operators

![]() $(-)\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }$

and

$(-)\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }$

and

![]() $\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } (-)$

in Definition 3.10 as guards. Note that

$\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } (-)$

in Definition 3.10 as guards. Note that

![]() $\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } f=\bot $

or

$\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } f=\bot $

or

![]() $f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }=\bot $

if, and only if,

$f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft }=\bot $

if, and only if,

![]() $f=\bot $

; this follows from the laws

$f=\bot $

; this follows from the laws

![]() $ (\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } f) f = f$

and

$ (\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft } f) f = f$

and

![]() $f(f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft })=f$

.

$f(f\mathbin {\blacktriangleleft })=f$

.

Conventional categories can be treated as abstract categories. First, the morphisms of the category can be packaged as a disjoint union into a common type A, which possibly requires an enlarged universe. Then we use

![]() $A^?$

as the carrier type for the abstract category

$A^?$

as the carrier type for the abstract category

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

, where the nullary operator

$\mathsf {A}$

, where the nullary operator

![]() $\bot :\Omega $

is identified with the term

$\bot :\Omega $

is identified with the term

![]() $\bot $

in

$\bot $

in

![]() $A^?$

; see (2.3). We write

$A^?$

; see (2.3). We write

![]() $a:\mathsf {A}$

to indicate that a is a term of the carrier type

$a:\mathsf {A}$

to indicate that a is a term of the carrier type

![]() $A^?$

. Henceforth, we assume that all abstract categories have carrier types of the form

$A^?$

. Henceforth, we assume that all abstract categories have carrier types of the form

![]() $A^?$

.

$A^?$

.

A useful subtype of an abstract category

![]() $\mathsf {A}$

is the type of identities:

$\mathsf {A}$

is the type of identities:

Since