1. Introduction

Rapid developments in artificial intelligence (AI) have exacerbated the debate regarding the implications for strategic-level decision-making (Basuchoudhary, Reference Basuchoudhary2024; Erskine & Miller, Reference Erskine and Miller2024; Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2025).Footnote 1, Footnote 2 Central to this debate is a quandary relating to user trust in AI. Given well-documented biases, such as automation and confirmation bias, decision makers must balance skepticism of AI with over-confidence in decision support algorithms (Gerlich, Reference Gerlich2024; Johnson, Reference Johnson2022). Klingbeil, Grutzner and Schreck (Reference Klingbeil, Grutzner and Schreck2024) refer to this as the tension between “algorithmic aversion” and “algorithmic appreciation.” Indeed, critics caution that AI will deskill humans and supplant their agency, leading to unintended consequences including crisis escalation, civilian casualties, and accountability and responsibility gaps for these outcomes (Cummings, Reference Cummings2006; Erskine, Reference Erskine2024; Johnson, Reference Johnson2023a, Reference Johnson2023b; Novelli, Taddeo & Floridi, Reference Novelli, Taddeo and Floridi2023; Sparrow, Reference Sparrow2016). Proponents of AI emphasize greater agency for machines during war, especially because AI will arguably create the need for more, not less, human judgment (Basuchoudhary, Reference Basuchoudhary2024; Goldfarb & Lindsay, Reference Goldfarb and Lindsay2022; Schwarz, Reference Schwarz2025). Advocates also contend that advancements in AI will lead to “human-machine teaming” (HMT) that optimizes countries’ decision-making during war (Arkin, Reference Arkin2010; Drennan, Reference Drennan and Jackson2018; Scharre, Reference Scharre2015).

Despite these predictions, it is unclear what shapes military servicemembers’ trust in AI, thus encouraging them to overcome their skepticism for HMT. Indeed, scholars have yet to systematically explore this topic, especially in terms of strategic-level deliberations. This oversight is puzzling for multiple reasons. First, understanding servicemembers’ attitudes of trust for AI is critical. They test, field, and manage the use of AI-enhanced military technologies, including those used for strategic-level decision-making (Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020; Lee & Zo, Reference Lee and Zo2017; Riza, Reference Riza2013; Wojton, Porter, Lane, Bieber & Madhavan, Reference Wojton, Porter, Lane, Bieber and Madhavan2020; Zwald, Kennedy & Ozer, Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025). Second, policymakers, scholars, and military practitioners agree that servicemembers’ trust is integral to HMT (Johnson, Reference Johnson2022; Mayer, Reference Mayer2023; Ryan, Reference Ryan2018). Finally, Kuo (Reference Kuo2022), Horowitz and Khan (Reference Horowitz and Khan2024), and Lindsay (Reference Lindsay2023) show that innovation can lead to novel technologies that underdeliver given poor user trust, thus exposing vulnerabilities that new capabilities are designed to redress.

Given this oversight, the purpose of this article is to address an important but understudied question. What shapes military attitudes of trust in AI used for strategic-level decision-making? To study this question, I use a conjoint survey experiment among an elite sample of senior officers from the United States (US) military to assess how varying features of AI shape servicemembers’ trust in the context of strategic-level decision-making.Footnote 3 The US has the technological wherewithal and financial resources to integrate AI into strategic-level deliberations (Bode, Huelss, Nadibaidze, Qiao-Franco & Watts, Reference Bode, Huelss, Nadibaidze, Qiao-Franco and Watts2023). More importantly, US political and military officials have experimented with AI during strategic-level deliberations (King, Reference King2024; Probasco, Reference Probasco2024; Woodcock, Reference Woodcock2023), which has implications for interoperability with allies and partners (Arai & Matsumoto, Reference Arai and Matsumoto2023; Blanchard, Thomas & Taddeo, Reference Blanchard, Thomas and Taddeo2024; Lee & Zo, Reference Lee and Zo2017; Lin-Greenberg, Reference Lin-Greenberg2020). American servicemembers, then, are a useful barometer for practitioners’ beliefs toward AI used for strategic-level decision-making.

I find that servicemembers’ trust in partnering with AI during strategic-level deliberations is based on a tightly calibrated set of considerations, including technical specifications, perceived effectiveness, and international oversight. The use of AI for non-lethal purposes, and with heightened precision and a degree of human control, positively shapes servicemembers’ trust in terms of strategic-level decision-making. Trust in AI is also favorably shaped by servicemembers’ utility-maximizing decision-making, wherein they attempt to balance harms imposed on civilians and soldiers with mission success. This finding contradicts the limited analyses of military attitudes toward AI, often driven by qualitative and non-falsifiable methods, wherein scholars claim servicemembers uncritically defer to machines for decision-making (Verdiesen, Reference Verdiesen2017). Regulatory oversight, particularly that levied internationally, also moderates servicemembers’ trust in AI, with such supervision increasing faith in AI.

I also find that trust can be a feature of heterogeneity across military ranks, though to a limited degree, suggesting strong professional enculturation among senior officers. I find that servicemembers who endorse congressional approval for AI trust it more in terms of strategic-level decision-making. This also suggests that while servicemembers may be nonpartisan, they are politically attuned, which has implications for civil–military relations regarding accountability and responsibility for outcomes shaped by the military’s use of AI. Blame for a failed war predicated on the military’s use of AI, for example, would likely carry consequences for political and military leaders who adopted a machine’s recommendations for policy and strategy, ranging from censure to removal from office and command (Croco & Weeks, Reference Croco and Weeks2016).

My analysis makes several contributions. First, I introduce novel data from an elite sample of senior US military officers relating to their attitudes of trust for AI, thus responding to scholars who emphasize the need for attitudinal studies across the military (Dotson & Stanley, Reference Dotson and Stanley2024; Salatino, Prevel, Caspar & Bue, Reference Salatino, Prevel, Caspar and Bue2025; Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025). This also advances a genre of experimental political science research among elites while bridging it with senior military officers, who exercise influence over the formulation of policy and strategy (Casler, Reference Casler2024; Kertzer & Renshon, Reference Kertzer and Renshon2022).

Second, given this rare data, I provide the first evidence for how varying features of the use, outcomes, and oversight of AI shape servicemembers’ attitudes of trust, thus helping them overcome skepticism that risks undermining the intended benefits of AI during future conflict. While this evidence provides new leverage over servicemembers’ attitudes of trust in AI used for strategic-level decision-making, thus connecting my study to the concerns of this special issue, it is likely that servicemembers’ beliefs are also relevant to their partnership with machines at other tactical and operational levels of war (Riza, Reference Riza2013). Research shows that servicemembers differentiate between AI used on the battlefield and in the war room (Erskine & Miller, Reference Erskine and Miller2024; Lushenko & Sparrow, Reference Lushenko and Sparrow2024), relating to what some experts refer to as “autonomy in motion” and “autonomy at rest” (Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025). This suggests that servicemembers reflect on the design features of novel technologies, as well as their operational and normative implications, when assessing the merits and limits of adopting these capabilities within the military.

Thus, servicemembers’ attitudes of trust in AI, as captured in this study, are likely scalable in terms of tactics, campaign planning, and strategy, even considering that the use of AI presents unique challenges across all levels of war, such as over trust regarding decisions to kill (Holbrook, Holman, Clingo & Wagner, Reference Holbrook, Holman, Clingo and Wagner2024), hallucinations or errors defined as “illusory inference” (Barassi, Reference Barassi2024, p.8), and crisis escalation (Lamparth & Schneider, Reference Lamparth and Schneider2024). The scalability of military attitudes of trust in AI is especially relevant for the elite sample of officers that I survey. They are responsible for integrating tactical operations into operational plans pursuant to strategic outcomes, such as deterrence and war termination. This implies that senior officers may draw on a common set of factors when determining their trust in AI used at these various levels. Similarly, research suggests that the scalability of military attitudes toward AI may also hold in cross-national contexts. Miron et al. (Reference Miron, Sattler, Whetham, Auzanneau and Kolstoe2025) explore the attitudes of senior British officers enrolled at the Joint Services Command and Staff College, including the Advanced and Higher Command and Staff Courses. They show that senior British officers also draw on a defined set of factors, largely consistent with the ones I investigate in this study, when determining their attitudes toward the use of AI for tactical, operational, and strategic decision-making.

Finally, I adopt innovative techniques to run my conjoint analysis. I build on studies that also use conjoint surveys to adjudicate the complexity of public attitudes toward the use of force abroad. These studies often find that a countervailing set of normative and instrumental beliefs shape overall attitudes toward the use of force abroad, contradicting monocausal explanations for the legal, moral, or ethical factors that are thought to inform public opinion in this context (Dill, Howlett & Muller-Crepon, Reference Dill, Howlett and Muller-Crepon2023; Dill & Schubiger, Reference Dill and Schubiger2021; Maxey, Reference Maxey2025). Similarly, I show that conjoint survey experiments are effective in capturing the directionality and intensity of attitudes, especially for complex, dynamic, and multidimensional concepts like servicemembers’ trust in partnering with AI-enhanced capabilities for strategic-level deliberations (Cvetkovic, Savela, Latikka & Oksanen, Reference Cvetkovic, Savela, Latikka and Oksanen2024; Dotson & Harper, Reference Dotson and Harper2024; Ham, Imai & Janson, Reference Ham, Imai and Janson2024; Laux, Wachter & Mittelstadt, Reference Laux, Wachter and Mittelstadt2024; Stantcheva, Reference Stantcheva2023).

This article unfolds in four parts. First, I canvass the literature on public attitudes for drones and AI to inform testable expectations for servicemembers’ trust in AI. I do not develop a new theory. Rather, I integrate and test mechanisms that may shape servicemembers’ trust in AI, which is useful to advance research on the implications of AI for strategic-level decision-making. Thus, I replicate an approach adopted by Maxey (Reference Maxey2025), Lushenko (Reference Lushenko2024), and Dill and Schubiger (Reference Dill and Schubiger2021). Next, I introduce my research design. Following this discussion, I outline my results. I conclude with the implications of my findings for research, policy, and military modernization, which combine to encourage more study to inform the measured adoption of AI during crisis escalation and future conflicts.

2. Trust and AI

The emergence of AI suggests movement toward what some experts call “centaur warfare” (Scharre, Reference Scharre2016).Footnote 4 This shapes HMT in two directions. For “human on the loop” capabilities, such as semi-autonomous drones, humans supervise recommendations made by algorithms. According to Schwarz (Reference Schwarz2025, p. 54), this approach suggests that a user is “in a position to make a conscious and informed decision about the appropriate use of the system; that he or she has adequate information about the target, the system itself and the context within which it will be used; that the system is predictable, transparent and reliable; that it has been adequately tested to operate as intended; that operators have been trained; and that there is the potential for timely human action and intervention.” For “human off the loop” capabilities, such as the US Air Force’s Loyal Wingman, systems operate without human oversight, and ostensibly in accordance with commanders’ priorities, rules of engagement, and international humanitarian law (Lushenko, Reference Lushenko2024).

These approaches assume that servicemembers are willing to partner with AI, demonstrating trust without potentially understanding how technology works due to poor transparency and explainability. Indeed, some AI-enabled capabilities are characterized as a “black box,” since their algorithmic functions are too complex to understand (Wiener, Reference Wiener1960). This means that users take a leap of faith in using these AI systems that they do not understand (Kreps, George, Lushenko & Rao, Reference Kreps, George, Lushenko and Rao2023). To be sure, servicemembers are trained to operate within a chain of command. They can also be vulnerable to automation and confirmation bias where they defer to AI given its assumed reliability and discount evidence that contradicts its recommendations. Even given these “non-standard revealed preferences” or biases, there is no guarantee that servicemembers will trust AI. Servicemembers can be so skeptical of AI that they incessantly intervene in its decision-making, thus undermining the perceived benefits of AI (Constantiou, Joshi & Stelmaszak, Reference Constantiou, Joshi, Stelmaszak, Constantiou, Joshi and Stelmaszak2024). The historical record suggests that these biases can cause preventable errors during conflict, including tragic ones resulting in civilian casualties (Dell’Acqua et al., Reference Dell’Acqua, McFowland, Mollick, Lifshitz-Assaf, Kellogg, Rajendran and Lakhani2023).

Yet scholars mostly explore public support for semi-autonomous drones that are sometimes augmented with AI (Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025). A handful of studies also investigate soldiers’ attitudes toward these drones (Lin-Greenberg, Reference Lin-Greenberg2022; Macdonald & Schneider, Reference Macdonald and Schneider2019). Thus, there is little systematic evidence relating to military attitudes toward AI, especially in terms of trust and at the strategic level of war, which is where leaders debate using force abroad (Wojton et al., Reference Wojton, Porter, Lane, Bieber and Madhavan2020). Indeed, Zwald et al. argue that trust “has received little analytical attention” in the scholarship on AI (Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025, p.4), which other researchers also echo (Klingbeil et al., Reference Klingbeil, Grutzner and Schreck2024).

For example, retired US Army Lieutenant General Robert Ashley, formerly Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, merely intones that “[t]rust remains essential, especially as decision cycles are shorter the closer you are to the fight” (Reference Ashley2024). Similarly, Johnson plainly assumes that AI will automatically “instill trust in how it reaches a particular decision about the use of military force” (Reference Johnson2022, p.458). Still other experts conflate servicemembers’ trust in partnering with AI with their “justified confidence” in doing so (Gonawela, Reference Gonawela2022). This position coincides with the global campaign, led in part by the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons and Group of Governmental Experts, to consolidate norms or standards of behavior surrounding what some analysts refer to as “meaningful human control” and “appropriate human judgement” over the use of AI during military operations (Huelss & Bode, Reference Huelss and Bode2022). While the latter term emphasizes commanders’ capacity to adjudicate the merits and limits of using novel technologies outfitted with AI, the former relates to unique temporal and spatial characteristics of specific AI-enabled operations (Roff, Reference Roff2024, Reference Roff2016).

These two terms are often used interchangeably and it is unclear how to best measure them in the context of decision-making. In a recent report on military AI, for instance, the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defense cautioned that “meaningful human control, exercised through context-appropriate human involvement, must always be considered across a system’s full lifecycle” (2024, p.5). Further, these two terms share little international consensus and lack broad advocacy for adoption within international humanitarian law (Ferl, Reference Ferl2023).

Consistent with the limited extant research that explores public and military attitudes toward AI (Kreps et al., Reference Kreps, George, Lushenko and Rao2023; Lushenko & Sparrow, Reference Lushenko and Sparrow2024), I circumvent this conceptual and empirical morass to investigate user trust in AI. Of course, trust is also a highly contested concept, even though it has been characterized as “a lubricant for social systems” (Arrow, Reference Arrow1974, p.23). As such, I adopt an operational definition of trust that draws from behavioral economics. Trust refers to the decision to use a technology based on the perception that it will reliably perform as expected (Evans & Krueger, Reference Evans and Krueger2009), which some scholars refer to as “calibrated trust” (Dotson & Harper, Reference Dotson and Harper2024), “evaluative trust” (Devine, Valgardsson, Jennings, Stoker & Bunting, Reference Devine, Valgardsson, Jennings, Stoker and Bunting2025), “performance trust” (Kohn et al., Reference Kohn, Cohen, Johnson, Terman, Weltman and Lyons2024), “predictability-based trust” (Roff & Danks, Reference Roff and Danks2018), and “structured trust” (Klingbeil et al., Reference Klingbeil, Grutzner and Schreck2024). Trust, then, is a function of anticipated vulnerability and expected performance rather than perceptions of legitimacy or rightful conduct, which may be the case for trust in terms of other interpersonal contexts, such as politics or litigation (Ben-Michael et al., Reference Ben-Michael, Greiner, Huang, Imai, Jiang and Shin2024; Devine, Reference Devine2024; Devine et al., Reference Devine, Valgardsson, Jennings, Stoker and Bunting2025; Simon, Reference Simon2020; Uslaner, Reference Uslaner2017; Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025).

Though novel, this operational definition of trust is based on several assumptions. It assumes that people have the neurological pathways to trust machines’ actions as they do humans’ behaviors, which research suggests they may not (Hoff & Bashir, Reference Hoff and Bashir2015; Montag et al., Reference Montag, Klugah-Brown, Zhou, Wernicke, Liu, Kou and Becker2023). At the same time, research also shows that notwithstanding its impressive predictive power, AI underperforms compared to humans in terms of creativity (Hasse, Henel & Pokutta, Reference Hasse, Henel and Pokutta2025) and decision-making (Deco, Perl & Kringelback, Reference Deco, Perl and Kringelback2025), and that HMT produces fewer desirable outcomes than if the most capable humans or AI acted alone (Klingbeil et al., Reference Klingbeil, Grutzner and Schreck2024; Vaccaro, Almaatouq & Malone, Reference Vaccaro, Almaatouq and Malone2024). As such, trust may constitute a false positive in terms of servicemembers’ expectations that AI will reliably perform and produce optimal results for decision-making. In other words, users’ trust in AI may be tantamount to their (over)reliance on the capability. These insights also help explain why users sometimes trust AI by proxy, wherein their trust in AI is a function of observing how other humans interact with machines (Dotson & Harper, Reference Dotson and Harper2024). While user trust in AI may be based on expected outcomes, then, it may also be performative, suggesting that anticipated social behaviors can also condition the uptake of new capabilities. Such social desirability bias is likely to exercise a powerful effect across the military. Leaders set cultures, shaped by informal and formal norms, that regulate and constitute subordinates’ behaviors, in this case the adoption of AI (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2025).

However, the definition of trust I adopt has several advantages. First, it is measurable and testable in an experimental setting. Second, it comports with research in Science and Technology Studies on user trust in emerging capabilities (Abbas, Scholz & Reid, Reference Abbas, Scholz and Reid2018; Siegrist, Gutscher & Earle, Reference Siegrist, Gutscher and Earle2005). Similarly, it echoes an operational definition of user trust in AI adopted by the US Department of Defense (2022) that is, for better or worse, leading global efforts for the responsible military use of AI. Fourth, it further reflects that trust is contextual, shifting based on factors that can shape user experience. Indeed, Dotson and Harper (Reference Dotson and Harper2024), Troath (Reference Troath2024), and Zwald et al. (Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025) argue that user trust in machines is context dependent and therefore contingent, which echoes research by political scientists who incorporate biological approaches into their investigations of social attitudes, including trust (Hatemi & McDermott, Reference Hatemi and McDermott2011). Finally, it emphasizes considerations of vulnerability and expectation, which have also been shown to shape public opinion toward AI and are assumed to do so among strategic-level decision makers (Lee & See, Reference Lee and See2004; Zhang, Reference Zhang, Bullock, Chen, Himmelreich, Hudson, Korinek, Young and Zhang2022). Johnson, for instance, claims that “as the reliability of the information improves so the propensity to trust machines increases” (Reference Johnson2022, p.444). Below, I discuss mechanisms that scholars have identified linking public attitudes to drones and AI, enabling me to derive testable hypotheses about the implications for servicemembers’ trust in AI.

2.1. Mechanisms

The platform of use may shape servicemembers’ trust in AI. Macdonald and Schneider (Reference Macdonald and Schneider2019) find that soldiers’ preference for drones covaries with operational risk, wherein they support the use of manned over unmanned aerial capabilities when combat troops are under fire. This preference is likely to be compounded by the emergence of capabilities that result in manned-unmanned teams, especially considering their novelty and the propensity for humans to blame machines for mistakes in the context of HMT (Horowitz et al., Reference Horowitz and Lin-Greenberg2022; Lin-Greenberg, Reference Lin-Greenberg2022; Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025). To be sure, AI used for strategic-level deliberations are encumbered to perform a more taxing range of cognitive tasks, even though the outcomes for policy, strategy, and course-of-action development are still only probabilistic assessments of what the inputted data, including war plans, doctrine, and threat estimates, would suggest given perfect information (West & Allen, Reference West and Allen2018). Yet the vividness of ground combat, resulting from servicemembers’ physical proximity to violence that is increasingly publicized via social media (Ford & Hoskins, Reference Ford and Hoskins2022), implies that decision makers may demonstrate more trust in ground-based technologies integrated with AI rather than those operated in other—air and space—domains, though the degree of human oversight may vary across these operational environments as well. Indeed, Yarhi-Milo’s (Reference Yarhi-Milo2014, p.16) research shows that leaders “give inferential weight to information in proportion to its vividness,” which is acute during ground combat and may shape servicemembers’ trust in AI at comparatively higher degrees than if it is used to inform decisions across other domains.

Technical properties may also shape servicemembers’ trust in AI used for strategic-level decision-making. Lushenko (Reference Lushenko2023), Zwald et al. (Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025), and Lin-Greenberg (Reference Lin-Greenberg2022) find that citizens and security analysts hold similar preferences for non-lethal uses of AI. Kreps et al. (Reference Kreps, George, Lushenko and Rao2023) also show that precision and autonomy can shape public attitudes toward AI. Greater levels of accuracy and lower levels of machine control enhance public support, which other studies corroborate (Cvetkovic et al., Reference Cvetkovic, Savela, Latikka and Oksanen2024). In the context of fully autonomous weapons systems, Rosendorf, Smetana and Vranka (Reference Rosendorf, Smetana and Vranka2023) also find that Americans’ attitudes of support are mostly moderated by error-proneness, with target misidentification reducing approval the most. Military personnel, who are accustomed to operating in high-risk environments (Anestis, Green & Anestis, Reference Anestis, Green and Anestis2019), are likely to hold similar if not more pronounced views, particularly given the unproven nature of newer technologies (Nadibaidze, Bode & Zhang, Reference Nadibaidze, Bode and Zhang2024). Their trust in AI may be enhanced when it is used for seemingly benign purposes, is more accurate, and does not operate fully autonomously, affording greater human oversight.

Research suggests that the perceived effectiveness of military capabilities, in both normative and material terms, can also condition public support for the use of force (Dill & Schubiger, Reference Dill and Schubiger2021; Maxey, Reference Maxey2025). Rosendorf, Smetana and Vranka (Reference Rosendorf, Smetana and Vranka2022), Arai and Matsumoto (Reference Arai and Matsumoto2023), and Rosendorf et al. (Reference Rosendorf, Smetana and Vranka2023) show that this is consistent for AI. Servicemembers may share these beliefs, especially for AI used at the strategic level of war. First, Pfaff, Lowrance, Washburn & Carey (Reference Pfaff, Lowrance, Washburn and Carey2023, p.9) argue that servicemembers’ trust in AI is a function of preventing “potential harm to non-combatants and friendly forces.” Military personnel are trained to protect civilians during war. This constitutes a legal, moral, and strategic obligation, since civilians’ attitudes are critical to the durability of operations (Silverman, Reference Silverman2019). Servicemembers are also trained to protect each other, which is imperative during a protracted conflict characterized by high casualties. Indeed, while Hammes (Reference Hammes2023) and Riesen (Reference Riesen2023) argue that the military has a duty to use AI to minimize civilian casualties, Asaro (Reference Asaro and Liao2020, p.216) contends effective AI “maximize killing ‘bad guys’ while minimizing the killing of ‘good guys.’” Second, the contribution of AI to mission accomplishment is also likely to shape the military’s trust. This is because servicemembers are conditioned to believe “winning matters” and make decisions based on the expected utility of certain actions weighed against the risks, which is an inherently moral calculation that machines cannot make (Basuchoudhary, Reference Basuchoudhary2024; Leveringhaus, Reference Leveringhaus2018; Schwarz, Reference Schwarz2025). Thus, servicemembers’ trust in AI may be shaped by its perceived effectiveness in terms of collateral damage, force protection, and mission accomplishment.

Studies further suggest that public support for AI is not shaped by variation in regulation (Kreps et al., Reference Kreps, George, Lushenko and Rao2023), though citizens prefer when military technologies are used according to international law (Kreps, Reference Kreps2014). Servicemembers’ trust for AI is likely to be similar, especially considering they are trained to abide by international humanitarian law. For example, one recent study finds that servicemembers expect semi-autonomous drones to be used according to international law (Lushenko & Carter, Reference Lushenko and Carter2025). Further, servicemembers support drone strikes in the absence of a politicization of the targeting process, meaning they prefer when the US Congress delegates the authority to plan, prepare, and conduct operations to the military. This belief reflects Huntington’s (Reference Huntington1957) understanding of “objective” civilian control of the military. This pattern of civil–military relations is characterized by a bargain wherein the military’s autonomy for decision-making in war is exchanged for its abstention from politics. In the context of HMT, this understanding suggests servicemembers’ trust in AI is likely strongest when regulatory oversight is the broadest, or set internationally, which may also be useful to diffuse accountability for unintended consequences, especially civilian casualties.

Finally, while competition can shape public attitudes for the use of force abroad (Snidal, Reference Snidal1991), as well as trade (Drezner, Reference Drezner2008), the results are ambiguous for drones. Lushenko (Reference Lushenko2024) finds that an understanding of international competition does not shape public support for drones’ trade. On the other hand, Horowitz (Reference Horowitz2016) shows that international competition can enhance public support for the development and use of fully autonomous capabilities. Public support also increases for the use of these capabilities when they protect soldiers, suggesting an interaction effect between autonomy and purpose. A renewal of great power competition, as reflected in the US’ national security strategy, implies that servicemembers will likely demonstrate more trust in AI when it is incorporated into strategic-level decision-making if perceived adversaries are also using AI. This perspective reflects what some analysts claim is an AI “arms race” among the great powers (Scharre, Reference Scharre2021), with the victor ostensibly enjoying a first-mover advantage that imparts security and economic benefits, though the evidence for the payoffs of such “leading sector” innovation is debatable (Ding, Reference Ding2024; Horowitz, Reference Horowitz2018).

2.2. Expectations

This discussion suggests testable hypotheses for servicemembers’ trust in AI used during strategic-level deliberations. Generally, I anticipate that variation in the technical properties of AI, as well as shifts in its perceived effectiveness, oversight, and proliferation, will shape servicemembers’ trust in unique ways. These anticipated effects are annotated in Table 1.

Table 1. Expectations

Note: Anticipated positive (✓) and null (-) effect per attribute level. Table created by the author.

First, in terms of technical properties, I posit that servicemembers’ trust in AI will be strongest when it is incorporated into ground-based technologies (H1), is used non-lethally (H2), is highly accurate (H3), and does not operate fully autonomously (H4). Second, in terms of effectiveness, I anticipate that servicemembers’ trust for AI at the strategic level of war will be strongest when AI reduces risk to both civilians (H5) and friendly forces (H6) the most while maximizing the prospects for mission accomplishment (H7). Third, in terms of oversight and proliferation, I expect that servicemembers’ trust in AI will be strongest when it is adopted according to international regulations (H8) and is used by perceived adversaries (H9). These list hypotheses drive my conjoint survey design, allowing me to respond to experts who encourage the use of experiments to determine what shapes military trust in AI (Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025).

3. Research design

To test my expectations, I administered a single-module conjoint survey experiment in October 2023 among senior officers attending the US Army and Naval War Colleges. My approach is broadly consistent with political science research that also uses cross-over or cross-subject survey designs to generate empirical data (Suong, Desposato & Gartzke, Reference Suong, Desposato and Gartzke2024). My rare and elite sample, representative of senior military officers attending these premier institutions, is also helpful to draw unique insights into how servicemembers trust AI. It also affords strong statistical power given my within-subject survey design, which is not typical for experiments that use elite samples (Casler, Reference Casler2024). In other words, I have the requisite number of observations to run my analysis, especially given my repeated measure design where the outcome is measured more than once across all respondents, in this case nine times per respondent based on the number of AI attributes I explore.

This respondent pool is also a hard test for my expectations. First, I oversample field-grade officers who have decades of military service, meaning they have more operational and practical experience than junior officers with fewer years of service.Footnote 5 Second, these officers are older, with a majority ranging from 36 to 55 years old. Finally, these are senior officers, from which the US military will draw its generals and admirals, implying that they are responsible for managing the integration and use of AI during future conflict. Though they may have no choice but to adopt AI given direction from policymakers and the military brass, their seniority gives them latitude to decide on technology development, training, and integration pathways (Rosen, Reference Rosen1994). Despite or because of this responsibility, which is further shaped by organizational norms that encourage a conservative approach to capability development, especially when new technologies threaten existing cultures and missions across the military, these officers may be primed to distrust AI (Rosen, Reference Rosen1988).

Operationalizing the arguments above, I use Strezhnev, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto’s (Reference Strezhnev, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) Conjoint Survey Tool to concretely vary nine attributes along with their levels, using a uniform distribution of randomization where the attributes vary equally based on their number of levels. Admittedly, this approach may result in seemingly unrealistic combinations of attribute levels, such as the use of AI for communication relay that results in civilian casualties (Cuesta, Egami & Imai, Reference Cuesta, Egami and Imai2022). Yet this approach approximates the lack of information and uncertainty that characterizes military planning, which is exacerbated by the “black box” phenomenon of AI. In other words, a uniform distribution of randomization may enhance the mundane realism and ecological validity of my scenarios (Lin-Greenberg, Reference Lin-Greenberg2023).

First, I vary the platform, toggling between ground-based, aerial-based, and space-based AI, thus reflecting the most germane operational domains as well as an anticipated area of operations (Melamed, Rao, Willner & Kreps, Reference Melamed, Rao, Willner and Kreps2024). Second, I vary the purpose of AI between non-lethal and lethal missions, which senior political and military officials routinely debate. Third, I vary precision and autonomy of AI, replicating spectrums of accuracy and oversight introduced in studies of public attitudes for AI (Kreps et al., Reference Kreps, George, Lushenko and Rao2023; Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025). Similarly, I vary the levels of civilian and friendly casualties on the basis of Dill and Schubiger’s (Reference Dill and Schubiger2021) study, which are designed to approximate realistic outcomes while informing soldiers’ risk ratio, defined as a belief in the “acceptable” number of civilians to soldiers killed during combat (Sagan & Valentino, Reference Sagan and Valentino2020). I also draw on Dill and Schubiger’s (Reference Dill and Schubiger2021) study to vary the level of contribution to mission accomplishment, ranging from low to medium to high. Finally, I vary the regulation of AI between no regulation, domestic regulation, and international regulation, as well as vary the other adopters of AI, including US adversaries (China and Russia), allies (Turkey and France), and partners (Israel and Saudi Arabia).

In sum, I provide respondents nine conjoint tasks that vary nine attributes and levels therein, which is within the threshold for respondent fatigue (Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins & Yamamoto, Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2018). Jost and Kertzer (Reference Jost and Kertzer2023) and Suong et al. (Reference Suong, Desposato and Gartzke2024) note that higher cardinality allows for richer theoretical testing and comparative analysis while also accounting for confounding. Consistent with these and other studies (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015; Musgrave & Ward, Reference Musgrave and Ward2023), my approach is advantageous because it aids causal identification, captures the complexity of trust outcomes, enhances statistical power, and mitigates social desirability bias. Conjoint surveys are also advantageous when researchers are working with smaller and elite samples, which is the case for my study (Suong et al., Reference Suong, Desposato and Gartzke2024). Respondents in my study are presented with randomized scenarios for AI, which reflect a repository of thousands of attribute-level pairings, and offer their feedback. Though I am cautious not to over-generalize the results, I introduce the first evidence for how servicemembers trust AI used for strategic-level decision-making given variation in its use, outcomes, oversight, and proliferation.

Respondents first read a randomized scenario in which they reflect on a fictional but realistic war where the US Army uses AI under different circumstances and with different results. Initially, they are instructed to “Consider a large war involving the United States, in which US Army forces adopt a new AI-enabled military technology against a peer adversary.” This set-up reflects the realities of large-scale combat operations between countries in which ground forces are decisive to strategic outcomes, especially considering the critical occupation task they perform. Next, respondents are informed “This new capability is used under the following circumstances and with the following outcomes.” After receiving this experimental treatment, I ask respondents to measure their trust in AI using a five-point Likert scale—one denotes “strong distrust” and five denotes “strong trust.”Footnote 6 I rescale this dependent variable from zero to one (Dill et al., Reference Dill, Howlett and Muller-Crepon2023; Dill & Schubiger, Reference Dill and Schubiger2021). I analyze the data by calculating marginal means and average marginal component effects (AMCE), using an ordinary least squares regression with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors clustered on respondents.

The AMCE is a useful statistic because it captures multidimensional preferences in terms of directionality and intensity. Indeed, researchers argue that “trust is complex and multidimensional” (Fields, Reference Fields2016), which my survey design reflects. The AMCE represents how much the probability of servicemembers’ trust in AI would change on average if one attribute switched levels (Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins & Yamamoto, Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2023). My baseline attributes consist of an aerial-based platform, which constitutes a predominant use of AI, such as that incorporated in drones; strike operations, which represent the most contestable purpose of remote capabilities; moderate precision, the lowest defined degree of precision in this experimental setting; mixed-initiative autonomy that retains a degree of human control, which research shows is critical to public support for both drones and AI; the lowest number of civilian casualties and friendly forces saved, 0–2, thus benchmarking military attitudes of trust in AI against minimal outcomes for collateral damage and force protection; medium contribution to mission success, considering respondents may cluster on lower and higher possibilities of accomplishment; no regulatory oversight reflecting servicemembers’ demonstrated interest in some oversight of AI; and Saudi Arabia, which closely cooperates with the US though it is not a treaty ally.

I also incorporate variables in the regression framework that research suggests can moderate attitudes toward AI, such as political ideology. Given the nature of these normative and instrumental factors, and the shorter survey length, I gather them posttreatment to minimize bias (d’Urso & Bogdanowicz, Reference d’Urso and Bogdanowicz2025; Sheagley & Clifford, Reference Sheagley and Clifford2023; Stantcheva, Reference Stantcheva2023). At the same time, I review respondents’ feedback to an open-ended question asking them to explain their attitudes of trust in AI, which provides me further leverage over their propensity to partner with machines for strategic-level decision-making. There was no word limit and respondents could comment freely, since the data were de-identified.

Finally, I fulfill assumptions of conjoint designs (Hainmueller, Hopkins & Yamamoto, Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) while adopting several innovative techniques to mitigate potential bias. I account for respondents’ attentiveness by including an attention check (Ternovski & Orr, Reference Ternovski and Orr2022). I also approximate attentiveness based on respondents’ survey completion time (Read, Wolters & Berinsky, Reference Read, Wolters and Berinsky2022), using one and ten minutes as the lower and upper bounds (Bowen, Goldfien & Graham, Reference Bowen, Goldfien and Graham2022). Likewise, I calculate intra-respondent reliability by repeating the same scenario before and after the nine conjoint tasks and determining the percent agreement between respondents’ answers (Clayton, Horiuchi, Kaufman, King & Komisarchik, Reference Clayton, Horiuchi, Kaufman, King and Komisarchik2023). As a final measure, I calculate respondents’ trust for AI given five hypothetical capability profiles. This latter approach is inspired by a “nested” marginal means method (Dill et al., Reference Dill, Howlett and Muller-Crepon2023) and allows me to determine how servicemembers’ trust in AI can be moderated by seemingly unrelated but substantively important attribute levels. My results are robust when controlling for attentiveness and reliability, which is high at 87 percent, and reinforced by my textual analysis and simulations (see Supplementary Information (SI)).

4. Findings

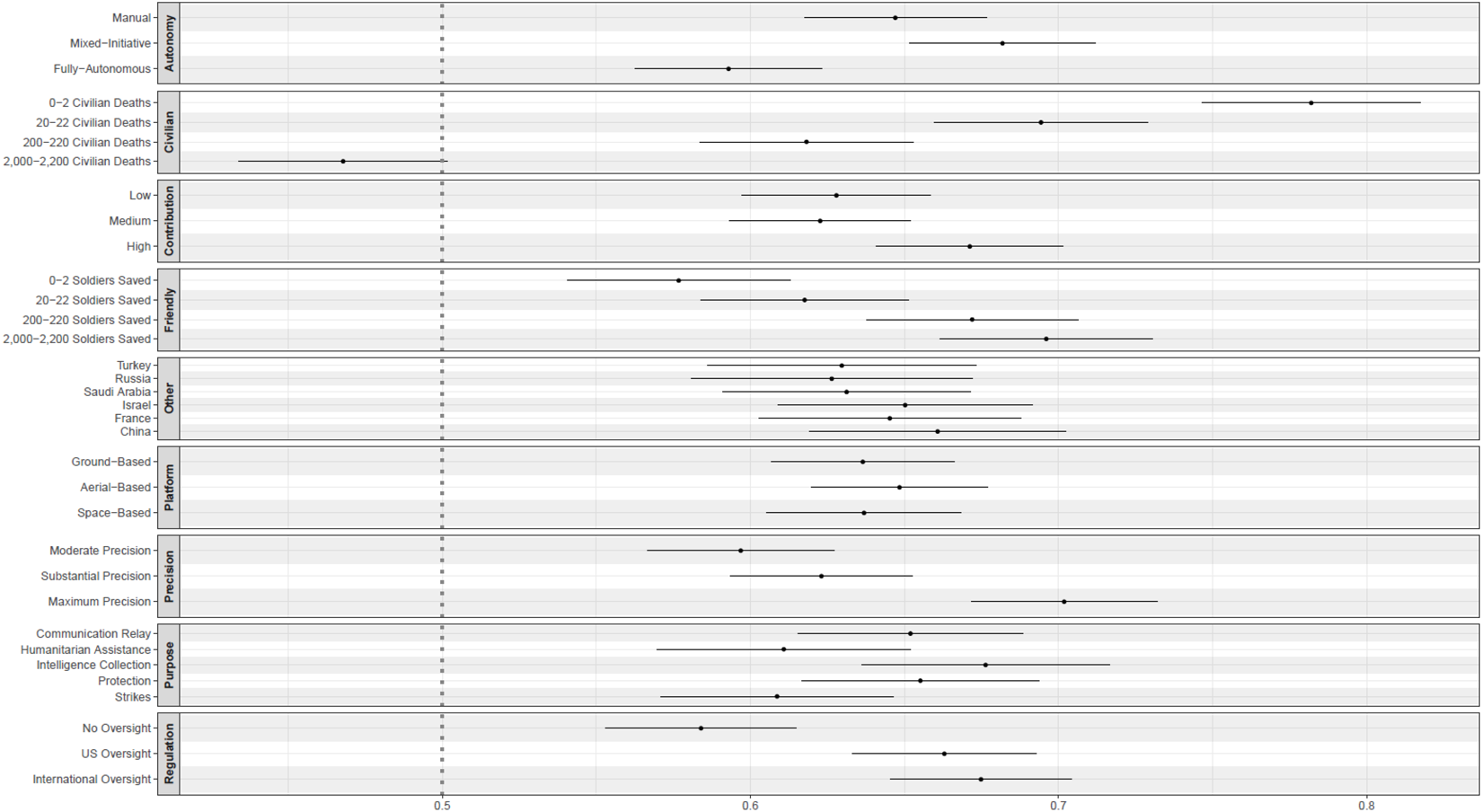

My findings suggest that servicemembers’ attitudes of trust in AI are shaped by three main considerations, including several technical specifications (H2, H3, and H4), perceived effectiveness (H5, H6, and H7), and especially international regulation (H8). First, respondents were most trusting of AI used for non-lethal purposes, with maximum precision, and with some degree of human oversight, that is, without full-autonomy. Model 1 in Table 2 shows the highest degree of servicemembers’ trust when AI is used for protection (β = .05, p < .10) and intelligence collection (β = .07, p < .05).Footnote 7 This latter result is consistent in Model 2, which adds controls. Respondents’ marginal mean willingness to trust AI was also highest for protection (.66, 95% CI: .62–.69) and intelligence collection (.68, 95% CI: .64–.72), and these outcomes were statistically different from the use of AI for strikes (Fig. 1). Indeed, consistent with other respondents’ explanations of their trust in AI during strategic-level deliberations, one servicemember noted, “I also trust it more for operations other than strikes, like humanitarian relief.”

Figure 1. Marginal means. Note: marginal means for the servicemembers’ trust in AI. Horizontal bars present 95 percent confidence intervals about each point estimate. Figure created by the author.

Table 2. AMCEs

Note: Robust standard errors, clustered on respondent, are in parentheses. Table created by the author.

+ p < 0.1,

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01

*** p < 0.001.

I also find strong support for the anticipated effect of precision on servicemembers’ trust for AI during strategic-level deliberations. They are less trusting of AI used with lower levels of precision, though trust is still high. I find that AI used with maximum precision, the highest degree of accuracy, is associated with the greatest probability of servicemembers’ trust. This is identical in Model 1 (β = .11, p < .001) and Model 2 (β = .11, p < .001) of Table 2.

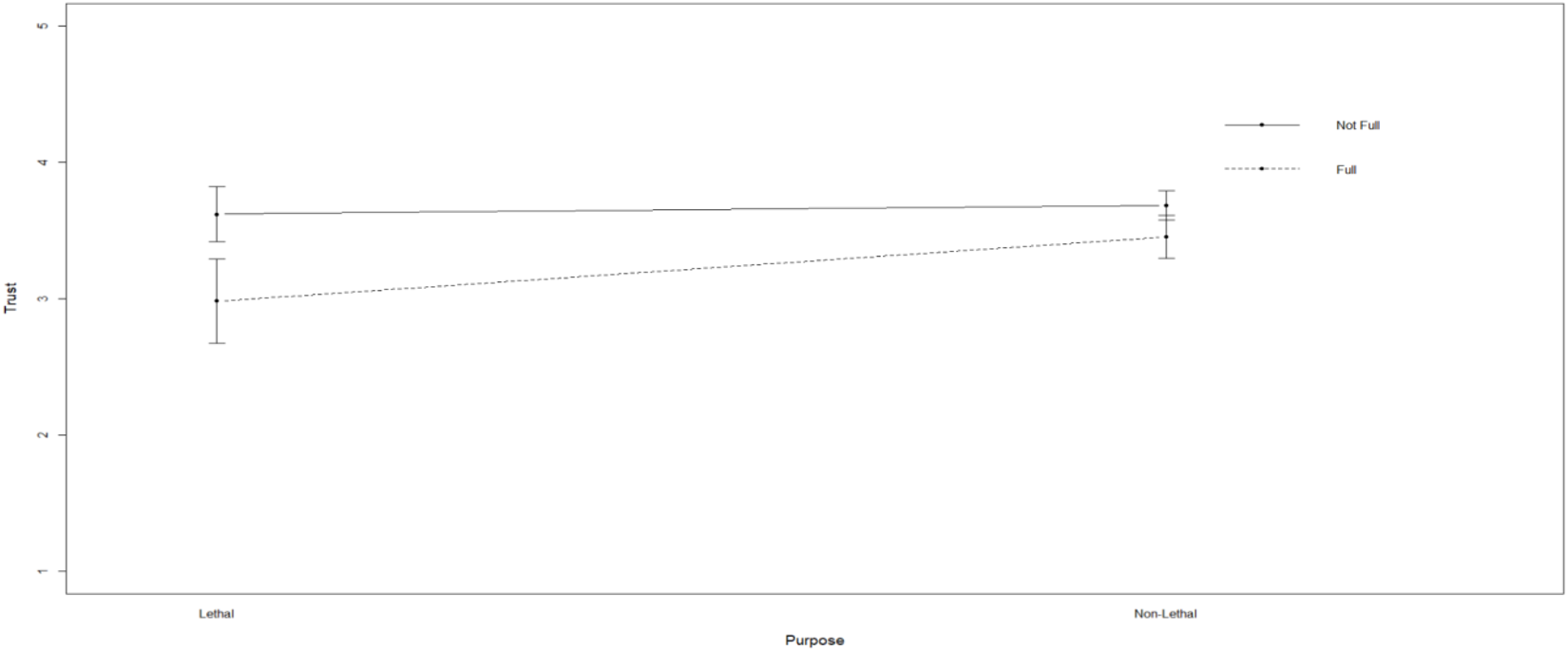

As reflected in Figure 1, respondents’ marginal mean willingness to trust AI was also highest for maximum precision (.70, 95% CI: .67–.73), followed by substantial precision (.62, 95% CI: .59–.65), and decreased under moderate precision to .59 (95% CI: .56–.63). Respondents’ marginal mean willingness to trust AI under the highest form of precision was also statistically different from lesser forms for precision, and respondents explained that greater precision, implying fewer false positives, shaped their overall trust in AI, especially when understood in terms of lethal operations. One respondent explained that for “strike systems without a human to hold accountable, I want to see precision above 95 percent accuracy.” This reinforces an interaction effect between autonomy and purpose (Horowitz, Reference Horowitz2016; Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025). In Figure 2, I interact fully autonomous AI-enhanced military technologies with their use for strikes, meaning I condition the level of autonomy on the purpose, and find that this reduces respondents’ trust (β = −.12, p < .01). At the same time, the use of AI with mixed-initiative autonomy for non-lethal purposes like intelligence collection (β = .10, p < .10), communication relay (β = .11, p < .05), and protection (β = .11, p < .05) can increase servicemembers’ trust, further reinforcing my overall finding (see SI).

Figure 2. Interaction effect of autonomy and purpose. Note: interaction effect of autonomy and purpose for servicemembers’ trust in AI. Vertical I-bars present 95 percent confidence intervals about each point estimate. Figure created by the author.

Another technical specification, then, can also shape servicemembers’ trust in AI used during strategic-level deliberations—autonomy. Though they acknowledge the desire to augment human judgment with some AI, servicemembers do not endorse fully outsourcing decision-making to machines, corroborating the findings of a recent study (Lushenko & Sparrow, Reference Lushenko and Sparrow2024). One respondent said, “I distrust autonomous systems that lack human oversight.” Another cautioned, “I will never fully trust AI, no matter how good it is. However, I realize that I must counter-balance that with the reality that AI is a big part of our future.” Still another respondent added, “we must never become beholden to AI’s fully autonomous systems. Human interaction is vital and AI should not have the final GO/NOGO decision.” This tension helps explain why the lowest probability of servicemembers’ trust in AI is associated with fully autonomous capabilities, as reflected in Models 1 (β = −.09, p < .001) and 2 (β = −.09, p < .001) of Table 2.

Servicemembers’ countervailing beliefs in human oversight of AI also helps explain why their marginal mean willingness to trust AI was lowest for fully autonomous systems (.59, 95% CI: .56–.62) and highest for mixed-initiative systems (.68, 95% CI: .65–.71), with these outcomes being statistically distinct. Respondents also discount their trust in AI that is operated manually, and the results are statistically different from higher/full and lower/mixed forms of autonomy. This finding further reflects servicemembers’ tension in appropriately calibrating oversight of AI.

Second, I find that the perceived effectiveness of AI can also shape military attitudes of trust. When controlling for other factors, an understanding of risk and contribution to mission accomplishment exercise the strongest effects in terms of servicemembers’ trust for AI. The lowest probability of servicemembers’ trust in AI is associated with the greatest risk to civilians (β = −.31, p < .001) and lowest protection of soldiers (β = .04, p > .10). As reflected in Table 2, servicemembers’ trust in AI is shaped by a similar threshold of civilian casualties and soldiers saved—200–220. While the magnitude of effect is similar and in opposite directions, servicemembers’ trust is also more dependent on collateral damage, namely civilian casualties. At the same time, respondents discount their marginal mean willingness to trust AI when the risk to civilians is highest (.47, 95% CI: .43–.50) and the protection of soldiers is lowest (.58, 95% CI: .54–.61). One respondent noted that trust reflected the “ratio of civilian casualties to US soldiers saved. I distrust fielding any system that can cause 1k–2k civilian casualties to save 0–2 soldiers. However, I am willing to accept civilian casualties if it saves at least as many US soldiers.” Similarly, one respondent explained that trust was primarily a function of the “estimated civilian deaths compared to the estimated military deaths.”

Overall, this logic reflects a recognition that soldiers assume a higher liability to be harmed during conflict, even when operations are conditioned by AI that is thought to better protect them. The results suggest servicemembers seem to expect friendly casualties during war, in this case at least 20–22 soldiers, which equates to two squads or half a platoon for a US Army Infantry Company. This finding contradicts theorists who claim that drones, as well as other remote warfare technologies on the horizon, have resulted in post-heroic war (Renic, Reference Renic2020) that “erode moral constraints” (Renic & Schwarz, Reference Renic and Schwarz2023, p.323), especially a duty of care to protect civilians during war (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2025). It also contradicts pundits who claim that experts considering the moral implications of novel technologies are misguided, or guilty of mortgaging advantages due to presumably inconsequential normative considerations (Deptula, Reference Deptula2023; Hammes, Reference Hammes2023).

On the other hand, servicemembers demonstrate more trust in AI that makes the greatest contribution to mission accomplishment. Consistent with other feedback, one respondent noted that “at least medium contribution to the overall mission (prefer, high)” was instrumental to trust. Indeed, high contribution to mission accomplishment is associated with the greatest probability of military trust in AI for strategic-level decision-making in both Models 1 (β = .05, p < .05) and 2 (β = .04, p < .05) of Table 2. Servicemembers’ marginal mean willingness to trust AI is also greatest for the highest degree of contribution to mission accomplishment (.67, 95% CI: .64–.70). I also find that the implications of risk and effectiveness on overall attitudes is more pronounced when these two considerations are interacted. Regardless of any degree of contribution to mission accomplishment, servicemembers discount their trust in AI that results in greater than 20–22 civilian deaths. Similarly, servicemembers only typically trust AI that provides a high contribution to mission accomplishment and saves more than 200–220 soldiers, which equates to a US Army Infantry Company (see SI).

Third, I find that servicemembers’ trust in AI can also be conditioned by regulatory oversight, especially internationally. One respondent argued that “a lack of oversight also significantly lowered my trust.” Another stated that “though I trust US regulation/oversight, it’s important for international oversight to ensure compliance to international laws rather than US domestic law.” As such, international regulatory oversight was associated with the greatest probability of military trust in AI used for strategic-level decision-making in Model 1 (β = .09, p < .01) of Table 2, and this is consistent with the magnitude of effect and statistical significance in Model 2 (β = .10, p < .001). Servicemembers’ marginal mean willingness to trust AI was identical for international regulatory oversight (.67, 95% CI: .64–.70) and US regulatory oversight (.66, 95% CI: .63–.69), and these differences in oversight were not statistically significant. Even when AI promised to enhance mission success, servicemembers show more trust with greater degrees of regulatory oversight, showing another important interaction effect (see SI).

I find less support for my other expectations. My results suggest that servicemembers’ trust in AI is not shaped by the platform (H1) as well as other adopters (H9), though respondents’ marginal mean willingness of trust hovered around .65 for these attributes. First, servicemembers do not differentiate between the platform in terms of their marginal mean willingness to trust AI. Also, variation in the platform does not meaningfully shape the probability of servicemembers’ trust in AI used for strategic-level decision-making. One respondent, for example, stated the “domain was unimportant” for trust.

Second, some respondents “felt less confident when adversaries used the technology,” especially China. One respondent noted, “I also looked at if China has adopted it, they may have adopted counters to it as well which could compromise the tech.” Yet international competition, suggesting fears of an AI arms race, did not shape servicemembers’ trust in AI. Though virtually 100 percent of respondents identified China and Russia as adversaries of the US, and virtually 100 percent of respondents identified France and Israel as US allies or partners, the propensity to trust AI is similar regardless of which country also adopted the capability.

Finally, I further study variation in servicemembers’ trust due to other considerations that can also moderate attitudes (Fisk, Merolla & Ramos, Reference Fisk, Merolla and Ramos2019), resulting in one additional finding. Controlling for other factors, I find that military trust for AI at the strategic level of war can be shaped by congressional approval. Congressional authorization for the use of AI enhances servicemembers’ trust (β = .14, p < .10). This finding reinforces my overall results for the implications of regulatory oversight on military attitudes of trust and reflects servicemembers’ deference to political authorities, whose approval for the military use of AI may help shield commanders from blame when accidents happen and mistakes are made. This outcome also echoes research showing that Americans support the use of drones when they are perceived to comply with domestic and international law (Schneider & Macdonald, Reference Schneider and Macdonald2016), with servicemembers also emphasizing the adoption of AI that aligns with domestic and international law in terms of their trust (Lushenko & Sparrow, Reference Lushenko and Sparrow2024).

5. Discussion

Military leaders claim that AI is decisive to success during future wars (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2023). Embedded within this characterization of the trajectory of war is an assumption that servicemembers will trust partnering with AI, on both the battlefield and in the war room. In other words, scholars often assume that servicemembers will suspend their skepticism of AI, which my results suggest they maintain. In a recent article, Mark Milley and Eric Schmidt, formerly Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and the CEO of Google, pontificated that “soldiers could sip coffee in their offices, monitoring screens far from the battlefield, as an AI system manages all kinds of robotic war machines” (Reference Milley and Schmidt2024). This is an understandable assumption considering the hierarchical nature of the military, wherein personnel reflexively obey orders and act in accordance with structures of power and norms when they are not directly following guidance. However, as Ferguson (Reference Ferguson2025, p.44) argues, this assumption also reflects an “extraordinary” tendency of US political and military leaders to exaggerate the impacts of technology. Indeed, my results suggest that military trust in AI is not a foregone conclusion, even when considering the potential for cognitive biases and consideration of international competition. Rather, servicemembers’ trust is complex, dynamic, and multidimensional, painting a more nuanced picture of military attitudes than observers recognize, especially among senior leaders that champion the movement toward AI-enabled warfare.

Based on an elite sample drawn from the US military, I provide the first experimental evidence for how varying features of AI can shape servicemembers’ trust in partnering with it in terms of strategic-level decision-making, which will be useful to understand military beliefs about AI used at other tactical and operational levels of war. My results suggest that trust is a function of a tightly calibrated set of considerations that relate to how AI is used, for what outcomes, and with what oversight. It is impossible to predict whether defense officials will develop AI in ways that maximize servicemembers’ trust. My survey data is also cross-sectional, some AI profiles may appear unrealistic, and my survey instrument does not approximate the stressors of crisis decision-making, such as limited sleep and anxiety. Thus, I do not explore how military attitudes of trust for AI might change over time, especially as AI matures, as well as the implications of unique operating environments and generational differences for servicemembers’ trust (Galliott, Reference Galliott, Roach and Eckert2020; Libel, Reference Libel2025; Lushenko & Sparrow, Reference Lushenko and Sparrow2024; Salatino et al., Reference Salatino, Prevel, Caspar and Bue2025). While research shows that high initial user trust in AI erodes over time due to under-performance and errors (Glikson & Woolley, Reference Glikson and Woolley2020), it also suggests that members of “Gen Z,” born between 1997 and 2007, are skeptical of AI (Merriman, Reference Merriman2023).

Nevertheless, this first evidence for the complexity of servicemembers’ trust has three implications for research on attitudes toward emerging technologies in war. First, scholars should extend my study, investigating the extent to which the type of conflict, domain of operations, political and military objectives, and specific targets shape trust among military personnel. As reflected by Lin-Greenberg’s (Reference Lin-Greenberg2023) study of crisis escalation due to the proliferation of drones, it may be the case that these factors also moderate servicemembers’ trust in AI used to augment decision-making at different levels. Second, should scholars disagree that the military attitudes of trust in AI that I explore in this experimental setting are scalable across tactical, operational, and strategic levels of war, they can append my survey instrument to expose servicemembers to randomized treatments that are explicitly shaped against strategic-level deliberations, such as those informing deterrence or war termination.

Third, scholars should further study heterogeneity in attitudes of trust across different ranks and generations of military personnel, as well as investigate how shifts in the decision-making level and type of oversight for AI can shape servicemembers’ trust (Libel, Reference Libel2025; Lushenko & Sparrow, Reference Lushenko and Sparrow2024). Finally, though scholars show that results from conjoint surveys have high external validity (Suong et al., Reference Suong, Desposato and Gartzke2024), this is still an outstanding question in the context I study. Other scholars also share this concern, but we lack empirical evidence for how cultural differences, for instance, may shape military attitudes of trust for AI (Arai & Matsumoto, Reference Arai and Matsumoto2023; Galliott & Wyatt, Reference Galliott and Wyatt2022; Lin-Greenberg, Reference Lin-Greenberg2023; Miron, Reference Miron, Sattler, Whetham, Auzanneau and Kolstoe2025; Neads, Farrell & Galbreath, Reference Neads, Farrell and Galbreath2023; Rosendorf, Smetana, Vranka & Dahlmann, Reference Rosendorf, Smetana, Vranka and Dahlmann2024; Zwald et al., Reference Zwald, Kennedy and Ozer2025). Most studies of public and military opinion for AI are reductionist and Barassi notes “[t]he real problem is that we simply do not have generalized data that can account for the cultural diversity and complexity of human life” (Reference Barassi2024, p.9). Thus, determining the cross-national validity of my findings is also important given policymakers’ and military leaders’ emphasis on interoperability with allies and partners during future conflicts (Kreps, Reference Kreps2011).

For policymakers and military leaders, my results also suggest several key take-aways. Policymakers and military leaders should temper their expectations for the implications of AI on war. Put differently, they should prepare to be “disappointed” by AI (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2025; Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2023). New battlefield technologies may represent more of an evolution, rather than revolution, of war (Kreps & Lushenko, Reference Lushenko2023). While the wars in Gaza and Ukraine suggest important changes in the way militaries fight, they also reflect key continuities (Biddle, Reference Biddle2023, Reference Biddle2024). Strategic success during war is still a function of countries’ will to sacrifice soldiers’ lives and taxpayers’ dollars to achieve military objectives that support national aims, which is a moral judgment that only countries’ human leaders can make (Basuchoudhary, Reference Basuchoudhary2024; Leveringhaus, Reference Leveringhaus2018; Schwarz, Reference Schwarz2025). In other words, while AI may be shifting the character of war, or how it is fought, it is not shifting the nature of war, or why it is fought. War is, and will remain, a clash of wills designed to achieve key military objectives that support overall aims, which are set by political leaders. Similarly, my results show the need for more testing and experimentation of AI, especially decision-support algorithms that enhance intelligence and logistics (Tomic, Posey & Lushenko, Reference Tomic, Posey, Lushenko, Klug and Leonard2025). In doing so, policymakers and military leaders should align warfighting concepts, doctrine, and regulations and policies that govern AI to reflect servicemembers’ attitudes, which promises to engender more trust.

Finally, if servicemembers’ trust in AI for strategic-level decision-making is, in part, shaped by international oversight, it could be increased by explanations from policymakers and military leaders for how policy on autonomous capabilities coincides with or diverges from international laws and norms informing their use (Bode & Hueless, Reference Huelss and Bode2022). This is crucial since the evolving use of AI is shaping the norms and laws that govern its adoption. Thus, while considering servicemembers’ expectations for AI, policymakers and military leaders can address broader questions surrounding countries’ adoption of AI during crisis escalation and war (Roach & Eckert, Reference Roach and Eckert2020). Fortunately, the Biden administration announced a “Political Declaration on the Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy” in February 2023, which it started to implement before President Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2025. This declaration reinforces existing policy on the lawful use of AI, namely the Department of Defense’s Directive 3000.09. It also synchronizes the efforts of other countries to establish “a set of norms for responsible development, deployment, and use of military AI capabilities,” as reflected through a promising international forum called “Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Military” (Assaad, Saunders & Liivoja, Reference Assaad, Saunders and Liivoja2024).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cfl.2025.10019.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jennifer Alessio, Zena Assaad, Amelia Arsenault, Ryan Badman, Toni Erskine, Gustavo Flores-Macías, Emily Hitchman, Tuukka Kaikkonen, Sarah Kreps, Max Lamparth, Jerry Landrum, Erik Lin-Greenberg, Stephen Miller, John Nagl, Michael Posey, Kanaka Rajan, Ondrej Rosendorf, Jennifer Spindel, Kristin Mulready-Stone, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article. I would also like to thank participants of workshops convened at the University of New South Wales (Sydney) in November 2023, Cornell University in February 2024, American Political Science Association in February 2024, US Naval War College in February 2024, Australian National University in June and July 2024, Hill School in November 2024, Mila-Quebec AI Institute in December 2024, US National Defense University in January 2025, International Studies Association in March 2025, and British International Studies Association in June 2025 for their helpful feedback.

Funding statement

The author declares none.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Government, Department of Defense, or Department of the Army.

Paul Lushenko is an Assistant Professor at the US Army War College, Professorial Lecturer at The George Washington University, and Senior Fellow at Cornell University’s Brooks School Tech Policy Institute and Institute of Politics and Global Affairs. He is also the author of three books, including The Legitimacy of Drone Warfare: Evaluating Public Perceptions.