1. Introduction

In nineteenth-century France, over one million individuals lived as domestic servants, largely unseen yet omnipresent within bourgeois homes. Imagine thirteen-year-old Marie, a maid-of-all-work in Paris in 1880. Rising before dawn in her freezing mansarde, she navigates silently through dark corridors, preparing the household for the day. Her life, dominated by gruelling, endless tasks, is guided by strictly enforced rules, including those meticulously regulating how masters and servants communicate – a reflection of profound social divisions. Despite comprising approximately 3% of the population, this workforce is under-researched, with only four monographs studying the nineteenth century, two of which are from the 1970s, and little linguistic study. This significant scholarly gap leaves crucial questions unanswered about everyday communication practices that upheld rigid class structures.

This article examines an underexplored aspect of historical politeness: politeness formulae in master-servant interactions in nineteenth-century France. It hypothesizes that politeness formulae, or conventionalized linguistic expressions, grew more common in the last quarter of the nineteenth century due to a crisis in domestic service. As servants increasingly assert autonomy and demand better conditions and pay, contemporary advice literature instructed employers to adopt polite language, not merely to protect servants’ dignity but also to secure their services in a competitive labour market. This study traces conventionalized formulae reflecting changing attitudes toward class hierarchy and authority.

The study works with prescriptive literature focusing on servant management. The primary research question investigates the advice to replace or pair traditional imperatives for issuing orders with politeness formulae. Unlike typical quantitative studies on politeness formula, this study adopts a qualitative approach to extract and analyse these expressions, which offer unique linguistic data within a prescriptive metadiscourse on politeness.

The article follows this structure. First, I review the theoretical background, covering three waves of politeness theory: Brown and Levinson’s (Reference Brown and Levinson1987 [1978]) linguistic strategies; discursive perspectives emphasizing negotiation and evaluation; the recent integrative model recognizing politeness as both scripted and context-sensitive. Terkourafi’s (e.g. Reference Terkourafi2001, Reference Terkourafi2002, Reference Terkourafi, Kühnlein, Hannes and Zeevat2003, Reference Terkourafi2005a, Reference Terkourafi, Marmaridou, Nikiforidou and Antonopoulou2005b) frame-based approach introduced the concept of conventionalization, the process whereby a linguistic structure acquires politeness as its default meaning due to frequent use in specific contexts. Next, I justify using prescriptive sources. These texts uniquely reflect the conventionalization of politeness formulae: while prescribing behaviours derived from exemplary practices, they simultaneously shape future interactions.

Following this, I present the corpus and methodology, detailing etiquette and conduct books and servant manuals. I discuss their editorial success, historical scope, and present my approach of extracting politeness formulae. The historical context of domestic service in France is then examined, emphasizing the harsh realities servants faced daily and the socio-economic conditions behind the crisis of domestic service. This discussion of broader societal dynamics contextualizes the linguistic analysis that follows.

At the core of this study, I map the prescribed politeness formula. The analysis of the resulting formulary identifies a consistency in linguistic patterns, particularly the presence of formulae such as voulez-vous?, voudriez-vous? and je vous prie, in the final decades of the century. Findings show these scripts responded to shifting servant-employer dynamics, reflecting greater recognition of servants’ ‘face’ and autonomy. I repeat the analysis for servant-master and master-master interactions, resulting in three distinct sets of directives.

This study advances historical pragmatics, showing how linguistic practices relate to broader transformations in social structure, labour relations, and class tensions in nineteenth-century France.

2. Theory

2.1 The three waves of politeness theory

Politeness research has developed through three waves. The first treated politeness as a set of face-saving linguistic strategies. The second emphasized how participants perceive and discuss politeness, focusing on metapragmatic commentary and folk conceptions. The current wave integrates both views, balancing conventional meanings with context-dependent interpretations.

The first wave of politeness theory, developed in Brown and Levinson (Reference Brown and Levinson1987 [1978]) and Leech (Reference Leech1983), built on Grice’s maxims (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) to conceptualize politeness as a universal strategy for mitigating face-threatening acts. Linguistic forms such as honorifics, indirect speech or diminutives were seen as inherently polite, which were strategically used to preserve social harmony. However, the model was criticized for overemphasizing universality and minimizing cultural and contextual variation. In response, the second wave – influenced by Eelen (Reference Eelen2001) and Watts (Reference Watts2003) – adopted a discursive perspective, arguing that politeness is not intrinsic to language but negotiated in interaction based on hearer evaluation, social norms and interpersonal relationships. This wave emphasized metapragmatic discourse, including folk descriptions and explicit (im)politeness commentary (e.g., ‘Hey! That was not very polite!’). Second-wave research highlighted the variability and subjectivity of politeness, framing it as socially constructed and emergent in interaction. However, its emphasis on situated and dynamic interpretations made it difficult to identify stable linguistic patterns across communicative contexts.

Currently, third-wave approaches seek to reconcile the earlier perspectives by emphasising that politeness encompasses both relatively stable, default interpretations and emergent, co-constructed meanings. As Haugh and Culpeper (Reference Haugh, Culpeper, Ilie and Neal2018) argue, a comprehensive theory of politeness must account for this dual nature – recurrent and recognizable, but also situated and interactionally negotiated. The third wave revived interest in typical linguistic patterns of language use – on the three waves see Culpeper and Hardaker (Reference Culpeper, Hardaker, Culpeper, Haugh and Kádár2017). Both Coulmas’ (Reference Coulmas1979) notion of conversational routines as prepatterned speech and Watts’ (Reference Watts2003) category of ‘politic language’ – language use conforming to social expectations – closely align with Terkourafi’s frame-based model (e.g. Reference Terkourafi2001, Reference Terkourafi2002, Reference Terkourafi, Kühnlein, Hannes and Zeevat2003, Reference Terkourafi2005a, Reference Terkourafi, Marmaridou, Nikiforidou and Antonopoulou2005b). Terkourafi argues that politeness derives from repeated linguistic patterns, linking it to predictability within established social contexts, called frames.

The frame-based approach theorizes conventionalization as a three-way relationship between an expression, a context and a speaker. An expression becomes “conventionalised for some use relative to a context for a speaker if it is used frequently enough in that context to achieve a particular illocutionary goal to that speaker’s experience” (Terkourafi and Kádár, Reference Terkourafi, Kádár, Culpeper, Haugh and Kádár2017: 182). The regular co-occurrence of a polite expression with a particular frame in the speaker’s direct experience makes politeness its default or “unchallenged” meaning (Terkourafi, Reference Terkourafi2005a: 248, Reference Terkourafi, Marmaridou, Nikiforidou and Antonopoulou2005b). Given regularity, speakers develop pre-existing knowledge of which expressions to use in specific contexts (Terkourafi, Reference Terkourafi2002: 197). Another term for a conventionalized linguistic expression is a politeness formula (Culpeper, Reference Culpeper2011: 120, 126-132). Conventionalization, Culpeper explains, is a historical process where expressions, through repeated use, gradually acquire stable associations with (im)politeness contexts (Reference Culpeper, Demmen, Bax and Kádár2011: 127). Over time, their use becomes non-strategic or automatic (Terkourafi, Reference Terkourafi2024: 114).

How can scholars access the conventionalization of language usage? Quantitative, corpus-based studies help map recurrent usages through frequency counts and statistics (e.g., Culpeper and Demmen, Reference Culpeper, Demmen, Bax and Kádár2011; Jucker, Reference Jucker2020; Jucker and Landert, Reference Jucker and Landert2023 for historical corpora). Here, I propose a qualitative method, constructing an inventory of politeness formula metapragmatically mentioned (Jucker, Reference Jucker2020: 20) in prescriptive metadiscourse using conduct and etiquette books (the two subgenres are compared in Section 3.1). My method builds on the insight that conventionalization happens not only through direct experience, but also through mediated channels (Culpeper Reference Culpeper2011: 131). Metadiscourse, even when not overtly prescriptive, “may enter public consciousness” and create “structured understandings” of language use, not only about what “it is usually like”, but also on what it “ought to be like” (Jaworski, Coupland and Galasiński, Reference Jaworski, Coupland, Galasiński, Jaworski, Coupland and Galasiński2004: 3, original emphasis; Culpeper, Reference Culpeper2011: 131-132). For instance, the imperative Portez ceci à monsieur le comte (‘bring this to his Lordship’) is presented as normal in such sources for commands from a mistress to a servant.Footnote 1 Prescriptive rules of the format ‘do not say X; instead, say Y’ blur the distinction between the use and the mention of politeness (Jucker, Reference Jucker2020: 20): X and Y are linguistic usages, which are metapragmatically mentioned. These formulaic data are unique because they are both a usage and a mention, almost always embedded in a rule. Rules, as Culpeper (Reference Culpeper2011: 103-134) explains, are a type of metapragmatic comment – imperative statements or authoritative prescriptions about what should (or should not) happen in a given context, shaped by social norms and conventions. Conduct and etiquette books, indeed, chain together such rules, some regulating verbal behaviour and some containing linguistic formulae.

Given the theoretical relevance of politeness formula for the third-wave model, can we further justify their extracting from conduct and etiquette books? To what extent do these texts reflect real-life usage?

2.2 The theoretical relevance of prescriptive sources

Books on good manners are not purely first-order or folk discourses merely conveying the subjective viewpoint of an author. Examining Giovanni Della Casa’s Galateo, a highly influential Renaissance conduct book from 1558, Culpeper (Reference Culpeper2017) argues that, while it contains first-order evaluations of politeness – being prescriptive, subjective, moralizing, and elite-biased – it also reflects second-order discourse, the external, objective perspective of the politeness researcher. Authors of such books are not just participants in the practices they rationalize, but also perspicacious observers and interpreters of social norms (Culpeper, Reference Culpeper2017: 198). As Culpeper (Reference Culpeper2017) and Alfonzetti (Reference Alfonzetti, Paternoster, Held and Kádár2023) note, viewing conduct books solely as a participant discourse is reductive. Terkourafi (Reference Terkourafi2011) goes further, asserting that first-order and second-order politeness accounts cannot be kept apart as descriptive and prescriptive norms, linked as they are by a cyclical process:

Prescriptive norms […] never materialize out of thin air; the process is never an entirely top-down or bottom-up one. Rather, prescriptive norms historically follow and reflect descriptive ones, while at the same time constraining future practices and so feeding back into the descriptive norms that gave rise to them in the first place. (ibid: 176).

Prescriptive norms historically follow and reflect descriptive ones while simultaneously constraining future practices. I align with Terkourafi’s view that conduct and etiquette writers reproduce exemplary usage, which they prescribe authoritatively. Their higher social standing legitimizes and helps perpetuate existing usage, a view shared by Taavitsainen and Jucker (Reference Taavitsainen, Jucker, Jucker and Taavitsainen2020: 7), who note that conduct writers “employ what they take to be exemplary behaviour of some people as a model for others to follow, and to the extent that people follow this advice, the prescriptive rules become the basis of description of what people actually do” (see also Paternoster, Reference Paternoster2022: 16-17).

In sum, I take conduct and etiquette books to both reflect and shape politeness norms. Their value, which is at the same time descriptive and prescriptive, lies in bridging folk and academic understandings of social interaction (see Sifianou, Reference Sifianou2024 on epistemic benefits of studying this middle ground).

2.3 Asymmetrical interactions in historical pragmatics

Section 2.1 distinguished between strategic, face-saving politeness (volition) and non-strategic, scripted politeness (discernment). Volition, associated with Western practices, involves strategic choices based on face imposition (Brown and Levinson, Reference Brown and Levinson1987 [1978]; Leech, Reference Leech1983). In contrast, Asian languages tend to rely on pre-negotiated use of honorifics as determined by the social context (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Ide, Ikuta, Kawasaki and Ogino1986; Matsumoto, Reference Matsumoto1988; Ide, Reference Ide1989 on Japanese wakimae or ‘discernment’). Recent scholarship (Kádár and Mills, Reference Kádár and Mills2013; Claudel, Reference Claudel2021) challenge this strict dichotomy, viewing it instead as a continuum, given that some Western formal contexts also require discernment politeness and vice versa. Discernment has also been applied to historical (im)politeness. In their founding volume, Culpeper and Kádár (Reference Culpeper and Kádár2010) linked historical European deference devices to discernment. However, Kerbrat-Orecchioni (Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Bax and Kádár2011) upheld Brown and Levinson’s universalistic claims for the French classical age, although she acknowledged the ceremoniousness of its “over-elaborate formulae”, marked by a rigid etiquette “that should be adopted towards one’s superiors and subordinates” (ibid: 139-140). Looking further back, Denoyelle (Reference Denoyelle and Somolinos2013a: 154) highlights the link between French medieval hierarchy and directive types, emphasizing the important role of social position – other studies on French historical directives are Kremos, Reference Kremos1955; Frank, Reference Frank2011; Denoyelle, Reference Denoyelle and Lagorgette2013b; Gerstenberg and Skupien-Dekens, Reference Gerstenberg and Skupien-Dekens2021. Likewise, Held (Reference Held2010) described medieval French and Italian petition-writing as a deferent discernment, reinforcing conformity to social order over individual facework.

The role of social rank in historical politeness is highlighted by Ridealgh and Jucker (Reference Ridealgh and Jucker2019) for sources from strict hierarchical cultures. They define discernment as quasi-mandatory linguistic behaviour that is appropriate to the context and reflects the speaker-addressee relationship. Similarly, Ridealgh and Unceta Gómez (Reference Ridealgh and Unceta Gómez2020) affirm that in rigid social structures, superior-to-inferior communication – orders, insults, threats – is expected rather than impolite. Their study highlights the structured power dynamic of discernment, where deference is expected from inferiors, while superiors exercise Potestas, illustrated e.g. for master-servant interaction in Roman comedy. Both studies present discernment as scripted, rank-and-context-based behaviour rather than face-driven.Footnote 2 Simply put, the difference between volition and discernment is the following: volition reduces an imposition (a Face Threatening Act); discernment is dictated by social position and contextual appropriateness. While modern Japanese and historical discernment share a non-strategic and automatic nature, the latter is more mandatory due to stricter hierarchies. The difference, I surmise, is a question of degree, reinforcing the idea that volition and discernment exist on a continuum.

A highly relevant study is Biscetti (Reference Biscetti2015), who examines the master-servant dynamic in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English conduct books, exploring power asymmetries and tensions. While concentrating on threats and reproaches, which presuppose “wide power gaps”, she acknowledges that “commands are the most prototypical speech acts characterising a master’s role” (ibid: 288). This research aligns with mine: in the first half of the eighteenth century, Biscetti reports a shift towards greater empathy for servants, driven by an increasingly free labour market and evolving politeness norms. This new politeness aimed to preserve both master and servant face, moving away from strict hierarchical submission. At the dinner table in front of guests, e.g., imperious commands towards servants are to be replaced with this formula: “Sir, pray let me have a Glass of Beer or Wine, &c.” (ibid: 296). According to Biscetti (ibid: 302), citing Leech (Reference Leech1983), indirectness is seen as “milder” because it gives the hearer more options for non-compliance. Below, I explore to what extent the use of politeness formulae affords the servant genuine optionality.

This article focuses on the nineteenth century, a period of transition marked by the rise of the middle classes at the expense of the aristocratic élite, although scholars have noted linguistic change is slow. Culpeper and Demmen (Reference Culpeper, Demmen, Bax and Kádár2011: 53) provide a key framework for studying nineteenth-century politeness, linking the perception of the individual self and privacy as positive values in Victorian Britain to increased geographical and social mobility, industrialization, rapid urbanization and population growth, alongside romanticism and liberalism. Their study traces the emergence of ability-oriented conventional indirect requests with can you and could you. Now the most common formulae to make a request in English, it is absent before 1760 (ibid: 51). While non-imposition formulae developed in the nineteenth century in line with the new ideology of individualism, their rise was modest, a finding confirmed by Jucker for data in American English (Reference Jucker2020: 160-183).

3. Sources and Method

3.1 Sources

As mentioned, this study uses conduct and etiquette books, two subgenres of advice literature, usually called civilités and manuels de savoir-vivre in French tradition (Fisher, Reference Fisher1992; Rouvillois, Reference Rouvillois2020 [2006]). Conduct books teach basic manners for daily life – church, school, work, visits, dining, conversation – targeting mostly young readers from the lower middle class. To enable this readership to distinguish itself from the working class, they offer an inclusivist discourse on self-improvement through a moralizing, mainly Catholic lens. French etiquette books, in contrast, detail the complex social conventions of the elite, shedding the overt moralizing tone of conduct books. Their intended reader is an adult member of the upper-middle class, who has benefitted financially from industrialization and seeks to acquire the codes of fashionable behaviour to access high society.Footnote 3

Conduct books emerged in early modern Europe. A defining work was Erasmus’ De civilitate morum puerilium, from 1530, written for the French prince Henry of Burgundy. Conceived as a language teaching manual, it guided children on manners for church, school and family life, emphasizing bodily control and deference to superiors. French Catholic conduct books reinforced this moral and religious framework, notably seventeenth-century Saint François de Sales’ Introduction à la vie dévote, and early-eighteenth-century Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle’s Les Règles de la bienséance, both enduring bestsellers, with La Salle’s work reissued as late as 1875 (Fisher, Reference Fisher1992: 186). For the eighteenth century, Bérenguier (Reference Bérenguier2016) highlights conduct books for girls, with a focus on modesty, limited self-education, marriage and motherhood. During the nineteenth century, civilités only evolved slowly, blending Catholic and Rousseauist influences (Fisher, Reference Fisher1992). With the Third Republic’s introduction of compulsory primary schooling, conduct books became school texts. Ironically, “most of the books recommended are Catholic”, as the schoolbook publishing industry remained dominated by Catholic publishers” (ibid: 200; see Paternoster, Reference Paternoster2022: 38-44 for an overview). Conduct authors were mainly men: teachers, headmasters, or catholic priests.

Over 350 books on good manners, split evenly between conduct and etiquette books, circulated in France in the latter half of the century alone, a true “explosion” (Fisher, Reference Fisher1992: 45). Etiquette books are a nineteenth-century innovation, with the first French example published in Paris in 1808. Etiquette books appear sporadically until the 1850s, after which the genre rose exponentially (ibid: 54). Compared to the shorter, affordable conduct books, etiquette books sometimes exceeded 600 pages. Etiquette manuals were typically authored and read by women. Many aristocratic names and pennames signalled a readership from the “established or upper bourgeoisie, if not the aristocracy” (ibid: 80). Both genres were published across France, providing publishers with a steady income. Fisher also identifies a hybrid form blending moral instruction with practical etiquette, particularly in books for young girls. (ibid: 189). The successful guide by Clarisse Juranville (Reference Juranville1879) is a typical example, as is Boitard (Reference Boitard1851).

Conduct and etiquette books define politeness in fundamentally different ways. Paternoster and Saltamacchia (Reference Paternoster, Saltamacchia, Pandolfi, Miecznikowski, Christopher and Kamber2017: 269-272) argue that nineteenth-century Italian conduct books frame politeness through the Gospel’s Great Commandment “love thy neighbour as thyself” (Matthew 22:35-40; Mark 12:28-34), which underpins the golden rule: “do to others as you would have them do to you” (Matthew 7:12; Luke 6:31). French conduct books adopt a similar view, deriving specific rules from this overarching principle (Paternoster, Reference Paternoster2022: 104-107). Etiquette books, by contrast, lack a unifying principle and rules need to be memorized for prompt recall. Paternoster (Reference Paternoster2022: 337-338) defines etiquette as a tendentially amoral system of conventions and rituals governing upper-class behaviour, varying with time and place. Highly compulsory, etiquette serves as a gatekeeping mechanism, protecting access to elite circles and reinforcing social hierarchy through complicated, detailed scripts, which are structured around recurring social events (e.g., visits, dinners, balls, court presentations). Its rigid and intricate nature often induces unease in learners, mitigated by ease and tact.Footnote 4

Nineteenth-century French conduct and etiquette books are both well represented in digital libraries. Most texts were sourced from Gallica.fr, the digital library of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.Footnote 5 The current study uses 24 etiquette books (1808-1910), a self-built corpus of public-domain texts used in Paternoster (Reference Paternoster2022: 75-76), with the addition of Baroness Staffe (189125 [1889]), a highly successful publication.Footnote 6 The etiquette corpus contains only four sources for the decades spanning 1800-1870, when this new subgenre was slowly emerging, while 20 sources cover the decades in which it peaked. This is an important imbalance limiting diacronic analysis.

An additional nine conduct books were analysed to assess variation in identified formulae. The results confirmed consistency, though further expanding this corpus may yield additional formulae. Conduct sources span 1806-1904, but the selection is, as for etiquette books, top heavy, with six published after 1870. The same limitation applies. However, the disparity follows the editorial fortunes of the two subgenres, quickly accelerating after 1870.

Complementing the 33 comprehensive guides are ten specialized manuals on domestic service. The distinction between conduct and etiquette applies here as well. Two authors address mistresses on servant management: Dufaux de La Jonchère (Reference Dufaux de La Jonchère1884), who frequently quotes her earlier etiquette book (Reference Dufaux de La Jonchère1878–Reference Dufaux de La Jonchère1884?), and M. G. Belèze (Reference Belèze1860), on household management. Two other sources address both servants and mistresses: what the servant needs to know coincides with what the mistress needs to know for the purpose of training: anonymous Les bons domestiques; Manuel des jeunes ménagères (n.d.) and Mme Celnart (Reference Celnart1836), who also authored an earlier etiquette book (Reference Celnart1834 6 [1832]). Anonymous Le guide du domestique (1849) and Milon (Reference Milon1873 2) provide detailed, technical instructions for male and female servants. All of these are etiquette sources contrasting with four conduct guides for the pious servant from the first part of the century.Footnote 7 This selection achieves a more even distribution across the century.

3.2 Method

Using corpus linguistics to identify linguistic forms associated with a given speech act is a challenging task, given that speech acts are inherently defined by their communicative function, not by fixed linguistic expressions. Jucker (Reference Jucker2024b: 18-25) provides an overview of the two main methods used to search large corpora, both historical or contemporary: searches using typical linguistic patterns or routinized expressions (‘sorry’, ‘please’, ‘hi’) on one hand; searches based on meta-illocutionary expressions mentioning the speech act (‘apologise’, ‘thank’, …) on the other. With the former, a list of search items can be obtained, e.g., by manual pilot sampling (or seed sampling) in a small corpus (Landert, Reference Landert, Suhr, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen2019). However, identifying genuinely creative or emergent uses in such large datasets requires a different approach: one could search meta-illocutionary expressions in the hope that the actual speech act manifests itself in the immediate vicinity (Jucker Reference Jucker2024b: 24-25). Another method is to apply a fine-grained manual annotation of specific speech acts within a small corpus (ibid.: 17-19). For historical pragmatics, interactive sources are mainly literary, and findings may reflect literary style rather than ordinary language use.

This article proposes a different, qualitative approach to access routine expressions associated with polite orders: the development of a formulary for master-servant interaction based on advice literature. The method builds on Paternoster and Saltamacchia (Reference Paternoster, Saltamacchia, Pandolfi, Miecznikowski, Christopher and Kamber2017), who inventoried numerous formulae for apologies, disagreement, requests, besides impoliteness formulae, found in nineteenth-century Italian conduct books. While not ubiquitous, these formulae appear regularly. Mapping them for different speech acts found in advice literature, both diachronically and contrastively, is a future research goal. This study serves as a pilot, testing a single context, language and century. I introduce the term ‘formulary’ for the inventory of extracted formulae. The term is not novel. Medieval epistolary handbooks routinely assembled formularies – lists of greetings and closings for different correspondents and situations – that function as inventories of pragmatic routines (Lanham, Reference Lanham2004 [1975]). Classicists use the label in a similar way: Greek and Egyptian Magical Formularies (Faraone and Torallas Tovar, Reference Faraone and Torallas Tovar2022) is an edition and translation of papyri consisting solely of incantation formulae. I repurpose the historiographical genre label ‘formulary’ for analytical use in (historical) pragmatics, to name a scholarly inventory of speech-act formulae extracted from prescriptive sources by a speech-act analyst.

The formulary aims to be exhaustive for master-servant interactions across these 43 sources. It is based on close reading and manual collection of formulae, which are primarily found in chapters on servant management. For the specialisted manuals I read sections on master-servant interactions. To increase recall, searches were performed within the searchable PDFs using meta-illocutionary terms commonly found in the prescriptive rules to refer to the speech act ‘order’ – such as commander, ordonner (‘to command’), commandement, ordre (‘order’), as well as demander, exiger (‘to demand’), and demande (‘demand’).Footnote 8 I also searched by synonymes of domestique ‘domestic’: serviteur, servante, bonne, valet, femme de chambre in conduct and etiquette books. These manual searches were conducted in the hope of finding formulae in the vicinity. For the specialized manuals, the searches by synonymes of domestique gave too many false positives – in other words, the search was lacking precision. Similarly, a search with maître ‘master’ and maîtresse ‘mistress’ yielded low precision because it gave an excessive number of false positives for the three text genres. These supplementary searches identified a small number of additional formulae located in miscellaneous sections and in chapters on correspondence. Formulae selection followed a straightforward approach: all available expressions were included for three minimal frames: master-servant commands, servant-master requests, and master peer requests. The formulary is available for further verification in large-scale historical corpora like Frantext.

4. Servants in Nineteenth-Century France: From Self-Effacement to Face?

The study of nineteenth-century French domestic service was pioneered by Guiral and Thuillier (Reference Guiral and Thuillier1978) and Martin-Fugier (Reference Martin-Fugier1979), who highlighted the harsh realities of domestic labour and employer-servant dynamics, though relying heavily on anecdotal and literary sources.Footnote 9 More recent work by Piette (Reference Piette2000) and Beal (Reference Beal2019, Reference Beal, Poutrin and Lusset2022) incorporates archival records and quantitative analysis.

The scholarship agrees on the harsh conditions endured by domestic servants. Bourgeois households depended on them to escape material drudgery yet were uneasy about their intimate presence, leading to tight control over their lives: Beal (Reference Beal2019: 99-130) describes this as quadrillage, a grid-like, capillary regime of surveillance: emotional (forced smiles), bodily, and moral. Live-in servants worked from dawn to late at night, often beyond, with every hour accounted for. In Paris, strict spatial separation confined servants to tiny, unheated attic rooms (mansardes) on the sixth floor – cramped, poorly ventilated, with no running water or privacy. Those in less wealthy households often slept in broom closets. The scarcity of resources in many families led to tensions over food. Hygiene was a constant struggle as servants were denied bathroom access. Their bodies were also controlled: women wore uniforms with caps to cover their hair; men had to shave (Martin-Fugier, Reference Martin-Fugier1979: 27-32). Servants were expected to be nearly invisible, even losing their first names to generic replacements like Marthe or Marie (ibid: 55). Without workplace rights, dismissal was often instantaneous and devastating, pushing many young women into destitution or prostitution. Fear of losing employment forced many to endure harsh discipline, humiliation, and even corporal punishment (Beal, Reference Beal, Poutrin and Lusset2022). The sick were rarely cared for and usually dismissed outright. In sum, servants were defined by total self-effacement, being effectively treated as mere machines (see also Section 5.1), a view implicitly reinforced by the rules that take the imperative mode as self-evident. Given the immense workload, the lack of privacy, and the need for absolute obedience, Guiral and Thuillier (Reference Guiral and Thuillier1978: 13) claim that from the perspective of domestic service, the social hierarchy in France was, “in some ways, similar to a caste-based society”.Footnote 10

This began to change with the so-called crisis of domestic service or crise de la domesticité, when rapid servant turnover became a central concern for employers. For Beal (Reference Beal2019: 112) a climate of increasing tension began to emerge from the 1870s, caused by a republican discourse advocating democratisation with the events of 1870-1871. In the 1880s, it was a constant topic in social discourse. By 1900, employers perceived the industry to be in crisis; even in 1910, complaints about recruitment and retention persisted (Martin-Fugier, Reference Martin-Fugier1979: 33-38; Piette, Reference Piette2000: 329). Piette (Reference Piette2000: 328-367) analyses servant shortage for a Belgian context, with strong parallels to France. Traditionally, young rural women filled these roles, but by the 1880s migration from the countryside was slowing as rural working conditions improved – an effect compounded by a surge in demand (also discussed by Martin-Fugier, Reference Martin-Fugier1979: 36). This surge was fuelled by the growing aspirations of the petty bourgeoisie (artisans, shopkeepers, office clerks…), eager to mimic wealthier households, making a servant a status symbol rather than a necessity. Many stretched their finances to hire at least one maid-of-all-work, who was then overworked and underpaid, prompting frequent resignations. Aware of their leverage, domestics began negotiating higher wages. Many also left for factories or shops, which offered defined hours, legal protections, better pay and greater independence.

The crisis changed workforce dynamics. Servants were increasingly unwilling to accept substandard conditions. Beal (Reference Beal2019: 131-150) describes this shift as Eigen-Sinn, a growing sense of self (after Lüdtke, Reference Lūdtke1993), akin to workers’ search for autonomy and individuality on the factory floor through forms of resistance and obstinacy (see also Beal, Reference Beal2021 on servant grumpiness as a challenge to dependence). Through Eigen-Sinn, servants developed a positive sense of self, which may be interpreted as the acquisition of an individual ‘face’, in the broad meaning of the socio-cultural constraint by which people want to be treated in accordance with the way they see themselves as a person (Held, Reference Held2025).

Frustrated with the present, employers romanticized the past, longing for the ideal servant – faithful, obedient, and devoted (Piette, Reference Piette2000: 262-264). While Catholic writings had long promoted this ideal, the clergy now framed it as a solution to the crisis, urging domestics to see their work as a moral duty requiring humility and sacrifice benefitting superiors whose status was divinely ordained (Martin-Fugier, Reference Martin-Fugier1979: 139-144). This model-servant ideal extended beyond religious discourse, permeating advice literature, which historians often quote as evidence of a shifting interpersonal dynamic. Employers were encouraged to play a moral and educational role toward their servants. A form of maternalistic authority emerged, where mistresses were urged to treat domestics with kindness (bienveillance), Christian charity and fraternal love: “The duty of politeness towards inferiors is now among the obligations of the mistress of the house.” (Piette, Reference Piette2000: 375). Piette posits a causal link between the crisis of domestic service and this new emphasis on politeness as a solution. The perfect mistress – polite and patient – would keep good servants: “The mistress of the house has only herself to blame if she is not well served” (ibid: 376).

The analysis demonstrates that sources with politeness formulae overlap with the years of the so-called crisis.

5. Rules and Formulae

An important premise in this analysis is that, while gender often shapes patterns of discourse, no noticeable gender-based differences were observed. The rules consulted make no explicit distinction between male and female speakers or recipients, suggesting a shared normative framework. Accordingly, when I use the term ‘master’, it should be with ‘mistress’ subsumed under it. Similarly, ‘servant’ is used inclusively to refer to both male and female domestics.Footnote 11

5.1 Generic rules for master-servant interaction

Servant management for masters followed two distinct principles: one based on moral justification, the other on an instrumental approach.

Throughout the century, conduct sources – rooted in Catholic ideology – consistently invoked the Golden Rule for all social interactions, including those between masters and servants. L’Abbé Busson (Reference Busson1842: 128), an abbot, underscores this in his chapter Devoirs envers les maîtres, urging servants to be loyal in accordance with “le précepte de la charité du prochain” (‘the precept of charity towards one’s neighbour’). Later works continue to emphasize fraternity and shared humanity between masters and servants. Catholic priest Champeau (Reference Champeau1877 4/1864: 142) instructs masters to treat their servants as “vos frères en Jésus-Christ” (‘your brethren in Jesus Christ’). Raymond (Reference Raymond1873 8: 79-80), a secular author, similarly invokes the Golden Rule, condemning mistresses who “ne se font pas faute de tourmenter, souvent même d’humilier” (‘do not hesitate to torment, often even to humiliate’) those in their service: servants are not “une machine à servir” (‘a serving machine’) but “une créature” (‘a creature of God’). Juranville (Reference Juranville1879: 78) reinforces this, describing servants as “nos frères, pétris du même limon que nous” (‘our brethren, fashioned from the same clay as ourselves’). By the late nineteenth century, as the crisis of domestic service intensified, this discourse persisted. Salva (Reference Salva1898: 131) insists that all are equal before God.

Etiquette books, though less explicitly religious, echo similar sentiments. For Mme de Waddeville (Reference Waddeville1887 7: 289) servants are our equals for both civil and religious law. Hence, while education, luck, or wealth create social distance, “il est de notre devoir de ne point aggraver ce que cette condition a de pénible” (‘it is our duty not to aggravate the hardships inherent in this condition’). Clément (Reference Clément1879: 43) and La Marquise de Pompeillan (Reference Pompeillan1898: 118) also frame inequality as circumstantial rather than essential.

Conduct books and etiquette books, thus, share a common premise: servants deserve respect because they too are human. While most sources frame this as a moral obligation, a minority take a transactional view, treating politeness as a tool for securing better service. This goal-oriented reasoning appears primarily in texts published after 1870, aligning with the domestic service crisis. Boissieux (1877:16) directly links the need for politeness formulae (Table 1) to the goal of good service:

Si vous voulez être bien servi et toujours obéi, évitez toute familiarité avec ceux qui vous servent. Parlez-leur toujours poliment, et, en leur donnant vos ordres, soyez clairs et précis. (‘If you want to be well served and always obeyed, avoid all familiarity with those who serve you. Always speak politely to them, and when giving your orders, be clear and precise.’)

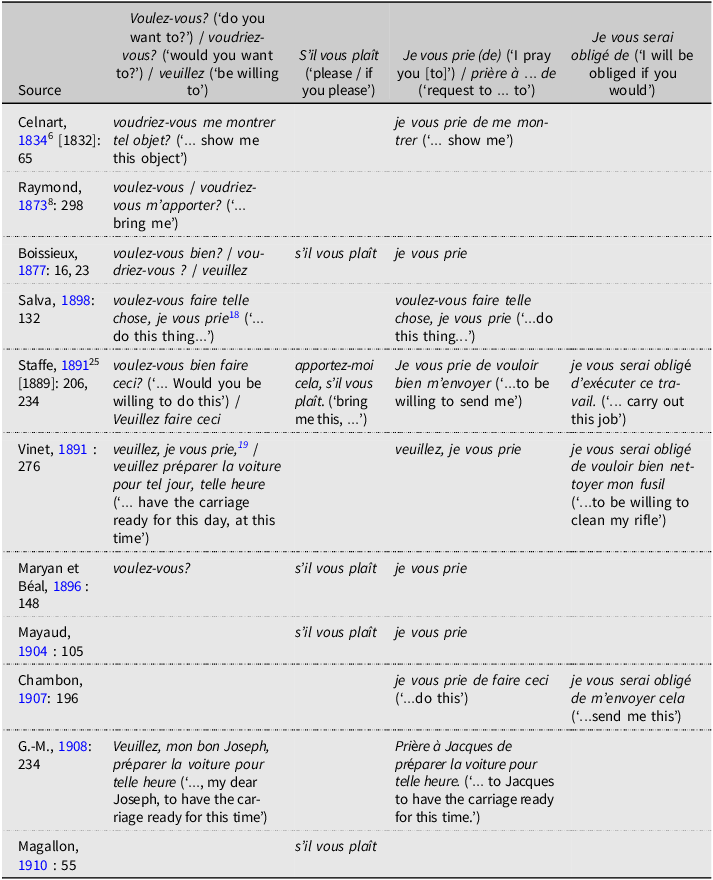

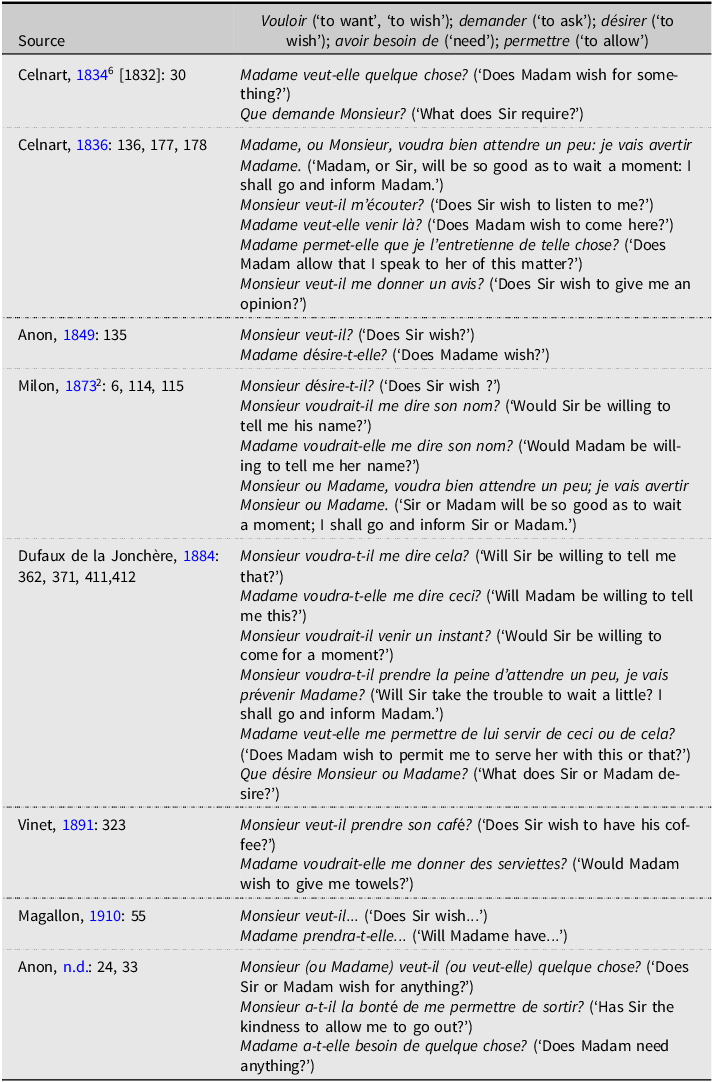

Table 1. Politeness formulary for master commands to servants

Dufaux de la Jonchère (Reference Dufaux de La Jonchère1878–Reference Dufaux de La Jonchère1884?6: 45) advises: “Ne les rudoyez pas; l’ordre donné avec douceur est toujours mieux saisi et mieux exécuté.” (‘Do not be rough with them; an order given with kindness is always better understood and better executed.’). She reiterates this in her servant management manual (Reference Terkourafi1884: 225), adding that politeness has a greater impact than one might assume. Staffe (Reference Staffe1891 25 [1889]: 206) argues that respect elicits respect: “Nous ne pouvons donc exiger leur respect que si nous les traitons avec bienveillance et considération.” (‘We can only demand their respect if we treat them with kindness and thoughtfulness.’). Similarly, Madame A. de La Fère (Reference La Fère1889 7: 132) – notably a male etiquette author using a female pseudonym – claims: “Plus vous serez bienveillants envers vos subordonnés, mieux vous serez servis par eux.” (‘The kinder you are to your subordinates, the better they will serve you.’). The idea is repeated by George Vinet (Reference Vinet1891: 214): “La politesse vis-à-vis d’eux est encore le meilleur moyen […] du moins de s’en faire respecter et servir selon son goût, […].” (‘Politeness towards them is still the best way […] at least to be respected by them and served according to one’s taste.’). Note that La Fère sees the use of kindness as an effective means to attach one’s servants to the household since a good one is precious: “Un bon domestique est chose précieuse; vous vous les attacherez par des égards.” (‘A good servant is a thing most precious; you will secure their loyalty through considerateness.’) (La Fère, Reference La Fère1889 7: 132; quoted verbatim in Vinet, Reference Vinet1891: 215).

This transactional approach reflects the shift in power dynamics discussed above. As servant turnover increased, politeness was no longer exclusively seen as a moral duty, but also as a means to secure loyalty.

5.2 Language rules for master-servant interaction

Many sources go beyond generic calls for politeness, outlining specific language rules. Although specific formulae are often lacking, prosody plays a key role in these rules. Some manuals formulate the rules negatively. Mme Celnart (Reference Celnart1834 6 [1832]: 28) warns against issuing commands “avec hauteur et dureté” (‘with haughtiness and harshness’, similar in Dash, Reference Dash1868 2: 48). Burani (Reference Burani1879: 27) also advises that orders should not be given “d’une voix brusque ni d’une façon emportée” (‘in a brusque or impulsive manner’). Other sources combine proscription with prescription. Orval (Reference Orval1901 6: 306) instructs that orders should be given “d’un ton bienveillant, sans hauteur ni morgue ridicules, mais avec précision” (‘in a benevolent tone, without haughtiness or ridiculous arrogance, but with precision’). The advice for a kind prosody is common in later sources; however, some sources abundantly precede the 1870s, the decade when the crisis of domestic service emerges: Celnart Reference Celnart1836; Busson, Reference Busson1842; De Meilheurat, Reference Meilheurat1852; Belèze, Reference Belèze1860. A few go even further, advocating not just a gentle tone but also the use of polite formulae. Raymond (Reference Raymond1873 8: 214) insists that children must be taught to issue orders “non seulement avec un ton doux, mais en employant des formules polies” (‘not only with a gentle tone but also using polite phrases’). She specifies the formulae in a subsequent chapter on improper language usage.

Across the century, the message is consistent: there is a widespread expectation that masters modulate their tone when issuing commands.Footnote 12

5.3 Formulae for master-servant interactions

The imperative remains conventional. Two reeditions of La Salle’s famous conduct book in the latter half of the century (Reference La Salle1857: 91, Reference La Salle1875: 91) assert that “les termes impératifs, qui indiquent l’ordre, ne peuvent être à l’usage qu’à l’égard des domestiques” (‘imperative terms, indicative of commands, may properly be employed only towards servants). La Salle’s (Reference La Salle1857: 91, Reference La Salle1875: 91) examples are: “Faites cela, allez en un tel endroit, donnez-moi cela.” (‘Do this, go to such-and-such a place, give me that’). Note that the verb uses the formal second-person plural, which I take to signal social distance (see also below). Likewise, La Fère evaluates imperatives as conventional for ‘inferiors’ and equals:

Évitez les impératifs qui ne conviennent qu’avec les inférieurs et quelquefois avec les égaux: Donnez-moi, par exemple; Veuillez me donner, est encore un ordre; […]. (‘Avoid imperatives suitable only for inferiors and occasionally equals: “Give me,” for instance; even “Be willing to give me” remains a command.’). (La Fère, Reference La Fère1889 7: 235)

This twentieth-century source lists formulae with the imperative as the appropriate form for an order: “Portez ceci à monsieur le comte”; “Demandez ses ordres à madame” (‘Carry this to his Lordship’; ‘Inquire as to madam’s commands’, Orval, Reference Orval1901 6: 148).Footnote 13

Others recommend specific politeness formulae. The following quotes include formulae within rules to show the immediate context. This conduct book emphasizes a kind prosody and advises either pairing the imperative with a politeness formula or replacing it with voulez-vous? (‘do you want?’):

Une femme bien élevée ne donnera jamais un ordre sec et bref, sur un ton de commandement, sans l’accompagner d’un: je vous prie, – voulez-vous, – s’il vous plaît. (‘A well-bred woman will never give a short, curt order in a commanding tone, without accompanying it with: “I pray you – do you want – if you please”.’). (Maryan and Béal, Reference Maryan and Béal1896: 148)

The next source considers the imperative impolite, recommending its replacement with a question, followed by je vous prie (‘I pray you’):

C’est ainsi qu’un homme poli ne commandera qu’avec des formules polies. Il dira à son domestique: “Voulez-vous faire telle chose, je vous prie”, et non: “Faites ceci ou cela.” (‘Thus, a polite man will only command with polite formulae. He will say to his servant: “Do you want to do this thing, I pray you”, and not: “Do this or that”.’). (Salva, Reference Salva1898: 132)

This later source also advises the use of s’il vous plaît (‘if you please’), noting that a politeness formula (alongside merci to thank) does not weaken authority:

[…] un “s’il vous plaît” n’atténue pas la valeur d’un ordre et un “merci” ne rabaisse nullement celui qui le prononce pour reconnaître un petit service. (‘an “if you please” does not diminish the value of an order, and a “thank you” in no way diminishes the one who uses it in recognition of a small service.’). (Magallon, Reference Magallon1910: 55)

Finally, some slightly more elaborate formulae are recommended for written notes, here specifically to an artisan:

Quand on écrit à un ouvrier qui a l’habitude de travailler pour vous, […] on commencera ainsi: Monsieur Lombard, Veuillez, je vous prie, ou: je vous serai obligé de vouloir bien nettoyer mon fusil pour tel jour; […]. (‘When writing to an artisan who is used to working for you, […] one starts as follows: “Mr Lombard, Be willing, I pray you, or: I will be obliged if you would be so good as to clean my rifle for such and such a day”; […]’). (Vinet, Reference Vinet1891: 276)

Other language advice regards the use of the formal vous pronoun and the use of the servant’s first name:

Ne tutoyez pas vos domestiques; cet usage n’est plus dans nos moeurs. Appelez-les par leur nom de baptême. (‘Do not address your servants with tu ‘thou’; this custom is no longer in our manners. Call them by their Christian name.’). (Boissieux, 1877: 16).

Table 1 shows the formulary for polite commands to servants. Note that Celnart’s (Reference Celnart1834 6 [1832]) formulae address a shop assistant, those in Vinet (Reference Vinet1891) and Chambon (Reference Chambon1907) regard written notes to artisans, tradespeople and servants, as well as these in Staffe (Reference Staffe1891 25 [1889]: 234): “Je vous prie de vouloir bien m’envoyer”; “Veuillez faire ceci; je vous serai obligé d’exécuter ce travail”. The ones found in Raymond (Reference Raymond1873 8) are said to be for equals and unspecified inferiors.

Eleven out of 43 sources contain one or more politeness formulae, in total 30 separate ones. While the imperative remains conventional, politeness formulae appear in a non-negligible number of sources. The 30 single occurrences cover only four types of politeness formulae – only three for spoken interaction. This high degree of consistency suggests a link to real-life, descriptive rules: if the formulae were purely invented, I would have expected more variation. All formulae identify as non-imposition politeness, which Brown and Levinson (Reference Brown and Levinson1987 [1987]) called negative politeness aimed at preserving face wants linked to autonomy. For the first-wave model the indirect phrasing would make an utterance intrinsically polite: the more indirectness (using a question instead of an imperative), the more polite. Before turning to an analysis of these linguistic expressions as instances of conventionalized usage, I first consider their strategic dimension, that is, their potentially mitigating function.

-

1. Blum-Kulka et al. (Reference Blum-Kulka, House and Kasper1989: 54–55) identify voulez-vous? and voudriez-vous? as conventionally indirect requests that question the hearer’s willingness to act, noting that this is characteristic of French. However, Ruytenbeek (Reference Ruytenbeek2020) argues that ‘can/could you?’ in French is also highly conventionalized for requests. The conditional voudriez appears three times and introduces greater optionality. According to Leech (Reference Leech1983), phrasing a request as a question increases optionality, offering the hearer an apparent choice and minimizing imposition. Two sources reinforce this effect by adding bien, also to verify willingness.Footnote 14 Expressions with vouloir appear in eight sources, making them the most frequently recommended politeness formulae for this context alongside je vous prie. The imperative veuillez does not express optionality, acting more like an entreaty, like je vous prie. It is also widely used in correspondence, particularly in closing formulae.

-

2. S’il vous plaît appears in five sources, either with a comma or as a standalone formula. While not always explicitly paired with an imperative, it is understood to soften an otherwise impolite imperative. Held (Reference Held, Paternoster, Held, Kádár and Issue2023) traces the evolution of polite requests with plaire à quelqu’un (‘to be agreeable, pleasing to someone; to suit someone’). Like voulez-vous?, s’il vous plaît (literally ‘if it pleases to you’) reduces imposition by verifying willingness in order to obtain agreement (ibid: 57). Originally expressing submissiveness in a dependent person, the conditional clause was then pragmaticized as a parenthetical mitigator (ibid: 57). Gerstenberg and Skupien-Dekens treat it as a politeness marker for a mid-seventeenth-century corpus of diplomatic letters, where it “is, syntactically, deletable, which supports its interpretation as a pragmatic marker” (Reference Gerstenberg and Skupien-Dekens2021: 18). The expression is already parenthetical in the seventeenth century.

-

3. Je vous prie appears in eight sources and is as frequently recommended as vouloir-based formulae. Mainly used parenthetically (with a comma or as a standalone formula), it also appears three times as a main verb, in an early source, 1834, and in later sources, 1891 and 1907. This suggests its pragmaticalization was still in progress. Gerstenberg and Skupien-Dekens (Reference Gerstenberg and Skupien-Dekens2021) identify je vous prie as the most common introduction of a directive in their corpus of diplomatic letters. However, due to its syntactic embedding in prier de (‘pray to [do something]’), it does not yet function as a fully pragmaticized politeness marker (ibid: 18). Prier originally meant ‘to beg’. To signal the distinction with fully impositive performatives like ‘to command’ and ‘to order’, Culpeper and Archer (Reference Culpeper, Archer, Jucker and Taavitsainen2008) classify verbs such as ‘to beg’, ‘to beseech’, ‘to entreat’ as hedged performatives, given a power dynamic where “the speaker is ‘requesting’ from a position of powerlessness, relative to the hearer” (Fraser, Reference Fraser, Cole and Morgan1975: 197). Thus, je vous prie expresses humility. It is also frequently recommended in letter closings, where it is used both parenthetically and as a main verb. The nominal construction Prière à … de … ‘request to … to …’ is recommended for written notes to a servant who is new in service, as opposed to the other formula found in G.-M. (Reference G.-M.1908), which is specifically recommended for a dedicated, long-serving servant.

-

4. Je vous serai obligé de appears in three sources, where it is consistently recommended for written notes to servants, artisans or tradesmen, which explains its more elaborate form. Typical of administrative language, the formula is conventionally indirect and conveys speaker humility. The future tense strongly and pre-emptively expresses the speaker’s awareness of a future debt, creating indebtedness, which puts the speaker under the obligation to reciprocate. Note that obligé ‘obliged’ comes from Latin ob-ligare ‘to bind, tie’ and carries the sense that the speaker is metaphorically bound to the hearer.

-

5. Finally, some expressions accumulate formulae: voulez-vous faire telle chose, je vous prie in Salva (Reference Salva1898); veuillez, je vous prie and je vous serai obligé de vouloir bien, both in Vinet (Reference Vinet1891).

Overall, the first two formulae are hearer-orientated, emphasizing optionality by verifying the hearer’s willingness to act, while the latter are speaker-orientated, expressing relative powerlessness. In the master-servant context, these formulae paradoxically verify the willingness of the servant – as if compliance were optional – and imply the powerlessness of the master, a counterintuitive dynamic given the historical context (Section 4). From a discernment perspective (Section 2.3), commands in the imperative represent traditional Potestas, where high-power rank determines linguistic choices without the need for face negotiation. However, the formulae in Table 1 show that face concerns have been acknowledged at some point in time. What initially would have been an ad hoc, strategic use to mitigate an order, which was increasingly perceived as a face-threat, has developed into a more stable, conventional use (to the point of being included in an instructional manual). For the formulae in Table 1 politeness has become a default meaning: they are, so to say, moving into a more automatic, discernment usage. My approach cannot be used to capture these earlier, strategic usages (it can only claim they must have existed before a certain date), but Table 1 contains an embryonic outline of a potential pathway.

In Table 1, early formulae appear in service encounters (Celnart, Reference Celnart1834 6 [1832]), while the examples with je vous serai obligé de appear in written notes to tradespeople and artisans.Footnote 15 This may indicate a diachrony whereby formulae that may already have been conventionalised as requests in external service interactions entered private homes once servants came to be viewed as paid service providers: while a master has direct authority over his own servants, with external tradespeople, the interaction is more of a transactional nature, with possible refusal and negotiation. All the same, expressions with vouloir (‘to want’) are conventionalized for service interactions in small shops in present-day France (Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Kerbrat-Orecchioni and Traverso2008: 118). More research is needed to confirm this derivation. That said, this raises the question of the type of directive involved: do politeness formulae transform the command into a request? I argue that they do not, because the servants have no right of refusal.

From a Cognitive Linguistics perspective, Ruytenbeek (Reference Ruytenbeek2019) examines the relationship between directive forms and the ontology of the speech act. Briefly, just as not every imperative is a command (it can be an offer), not every politeness marker (e.g. optionality expressions) turns an order ipso facto into a request. Ruytenbeek (ibid: 217) illustrates this with a conventionally indirect request: “Could you bring us something to wipe up the mess?”. In a high-to-low-status interaction – a boss addressing an employee – the sentence functions as a command rather than a genuine request (ibid: 217). The key factor is corporate hierarchy, where the employee is expected to comply: the presence of a certain “degree of optionality” in a directive does not necessarily diminish “the degree of obligation” placed on the addressee (ibid: 215). After listing politeness formulae Staffe (Reference Staffe1891 25 [1889]: 206) assures that linguistic politeness, actually, ensures obedience, stating: “Le domestique obéit toujours avec empressement et bonne volonté quand on lui ordonne de faire une chose en prenant un ton de douceur et de politesse.” (‘The servant always obeys with alacrity and good will when commanded to perform a task in a tone of gentleness and courtesy.’). She labels the speech act as ordonner (‘to order’). Other rules containing politeness formulae (see examples above) use the metalabels commander, ordonner (‘to command’), commandement, ordre (‘order’), as well as demander, exiger (‘to demand’), and demande (‘demand’).Footnote 16 Magallon (Reference Magallon1910: 55, quoted above) also states that a politeness formula does not reduce the force of an order. Note that most of the sources in Table 1 are from 1873 onwards, the decade in which the crisis of domestic service develops.

Pinto’s (Reference Pinto2011) distinction between truth-based sincerity (here, the master’s goal of being obeyed) and a procedural, rapport-based sincerity (about conveying politeness) helps further clarify the relation between obligation and optionality. Even if masters are not sincerely offering optionality, they can still be sincere in using politeness to preserve the face of the servant and their own face, that is, to manage the servant’s feelings and being seen as considerate (Jucker [Reference Jucker2020: 191] uses Pinto’s [Reference Pinto2011] distinction in the context of dissimulation). The servant, bound by contractual obligation, will perform the task, but politeness ensures he/she feel valued for it – a win-win dynamic.

Piette’s (Reference Piette2000) hypothesis – that politeness towards servants emerged in response to the service crisis – is supported by linguistic data. However, recommendations for a kind prosody go back further in time. This suggests additional factors beyond labour dynamics, such as broader socio-cultural shifts: the emergence of the middle class is marked by an increasing valorization of individualism, which goes hand in hand with a move away from rigid class distinctions. Thus, attributing politeness formulae solely to the service crisis somewhat oversimplifies their development. The crisis may have accelerated a process already underway.

At this point, it is useful to compare the top-down directives in Table 1 with two closely related contexts, servants’ speech to masters and masters requesting favours from peers. Both contexts use very different formulae to issue directives and it shows an enduring compartmentalization of formulae according to contexts and social status.

5.4 Formulae for servant-master interactions

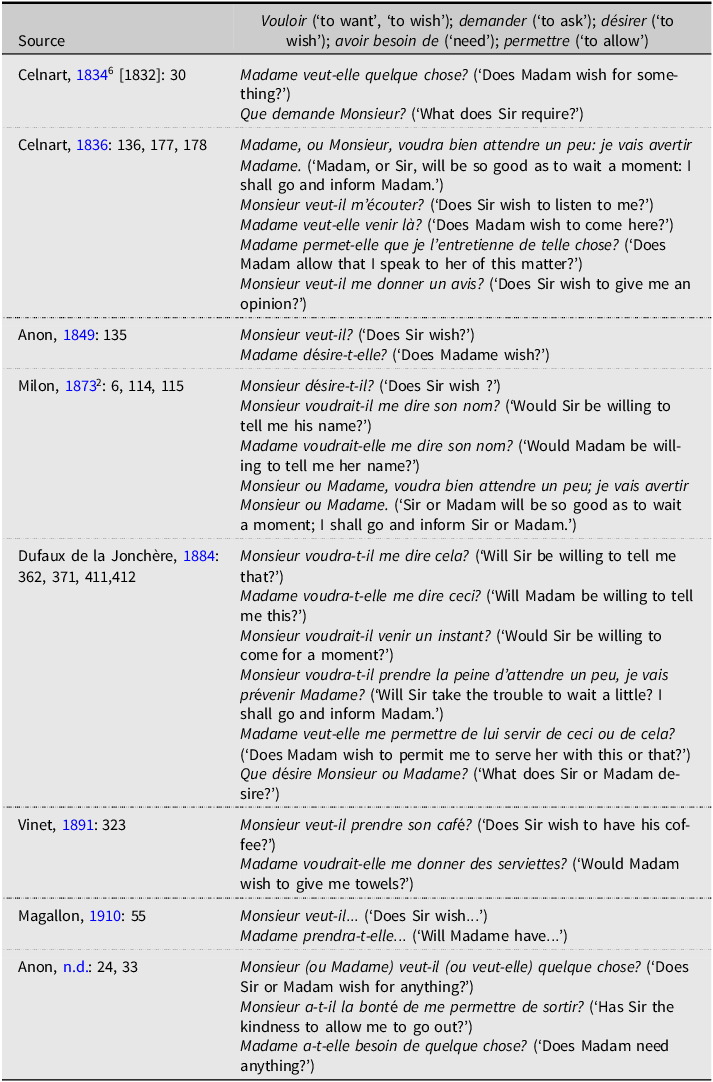

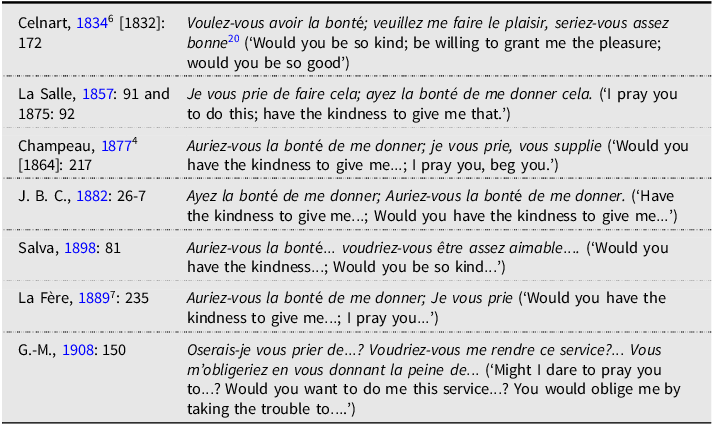

Table 2 lists formulae for servant-master interaction. While a commonly recommended formulae for master-servant interaction is the conventionally indirect question voulez-vous? or voudriez-vous?, formulae for servants requesting information regarding their masters’ wishes also use vouloir, though with a key difference. Servants use the verb in the third person, with the titles Monsieur and Madame:

Les domestiques ne parlent à leurs maîtres qu’à la troisième personne; en d’autres termes, ils ne disent jamais “Monsieur, voulez-vous me permettre cela? Madame, voulez-vous m’expliquer ceci?” (‘Servants address their masters only in the third person; in other words, they never say “Sir, do you want to alllow me this?” or “Madam, do you want to explain this to me?”’). (Dufaux de La Jonchère,Reference Dufaux de La Jonchère1884: 363)

Table 2. Politeness formulary for servant requests to masters

The formulae in Table 2 appear mainly (but not exclusively) in the specialized manuals, which provide a better coverage of the nineteenth century.

Celnart (Reference Celnart1836: 177) forbids imperatives in servant speech, even when not used as commands: servants must avoid “employer des tours de phrase qui ressemblent au commandement, tels que: Écoutez-moi. Venez-là. – Il faut venir déjeûner, dîner, etc.” (‘employing turns of phrase resembling commands, such as: “Listen to me. Come here. – One must come to breakfast, to dinner”, etc.’). Similarly, Champeau (Reference Champeau1877 4 [1864]: 127) states: “L’impératif ne convient point dans la bouche des inférieurs et rarement dans celle des égaux.” (‘The imperative is not fitting in the mouth of inferiors and is seldom appropriate even among equals.’). Imperatives are the master’s prerogative. As a result, master-servant and servant-master formulae for directives were mutually exclusive. Masters used imperatives, while servants used questions (with vouloir, désirer, demander, avoir besoin de) to request information about their master’s wishes and needs, with vouloir appearing in the present, future, and conditional. Permettre is hedged by the question format, asking permission to make a request benefiting the servant. Requests for guests to wait are further mitigated with un peu, bien, prendre la peine, and the grounder je vais avertir/prévenir monsieur ou madame. Even from the 1870s, when some sources recommend masters and servants use both vouloir, the formulae remain distinct because of title use and verb form.

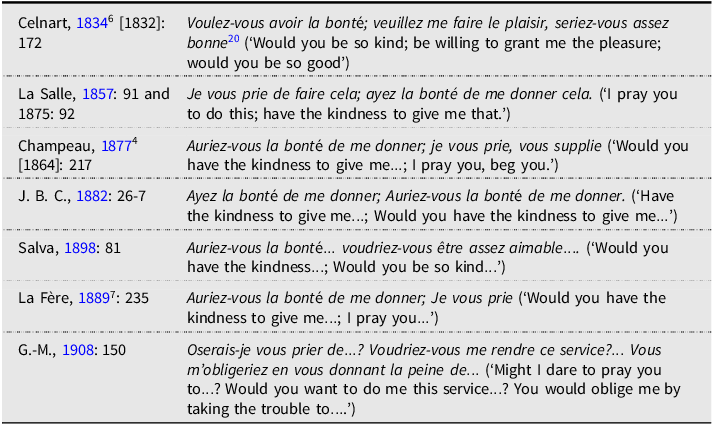

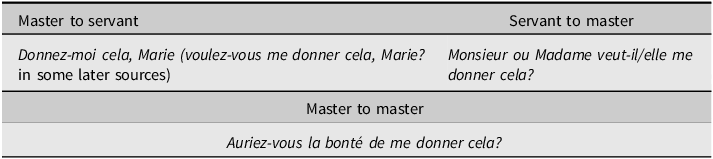

The politeness formulae for peer requests in Table 3 (prototypical due to the symmetrical relationship) largely differ from the asymmetrical ones in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 3. Politeness formulary for master peer requests

Note that Raymond’s formulae in Table 1 were intended for both equals and inferiors. Otherwise, aside from je vous prie (common, also, as letter closing), peer request formulae are preceded by preparatory interrogatives: conventionally indirect hearer-elevating commitment-seeking devices, which are mostly in the conditional, presuppose willingness. The imperative ayez appears twice. The hearer is elevated by a compliment: he/she is good, indulgent, amiable, obliging, which make refusal harder. As for Tables 1 and 2, the consistency between the formulae, especially with bonté, convincingly points towards a good degree of conventionalisation. Only G.-M. (Reference G.-M.1908) diverges, using speaker-orientated, humility-expressing formulae.Footnote 17 While voulez-vous?, voudriez-vous?, and veuillez – found in Table 1 for master-servant interactions – also appear in Table 3, they do so within longer commitment-seeking formulae. While more indirect than the findings in Table 1 given the accumulation of formulae, they are not more polite: they are conventionalised for a different context. Nowadays, such formulae are considered formal and business-like.

Voulez-vous, recommended for masters addressing servants, is the object of an intriguing ban for peer usage in formal dining. Anais, comtesse de Bassanville (Reference Bassanville1867: 240-241), forbids it for food offers:

Si un homme offre quelque chose à sa voisine, il ne doit pas lui dire Madame, voulez-vous telle chose? mais Me permettrez-vous, madame, de vous offrir telle chose? car la première formule est réservée aux domestiques. (‘If a gentleman offers something to his neighbour, he must not say, “Madam, do you want such a thing?” but rather, “Will you allow me, Madam, to offer you such a thing?” for the former phrasing is reserved for servants.’).

As voulez-vous is reserved for superiors addressing servants, it would risk offence with a female guest. Though the banned formula pertains to a food offer, the rule underscores how certain formulae are deeply tied to class distinctions, making their misuse a social blunder (on the stigma of etiquette blunders see Paternoster, Reference Paternoster2022: 235-280).

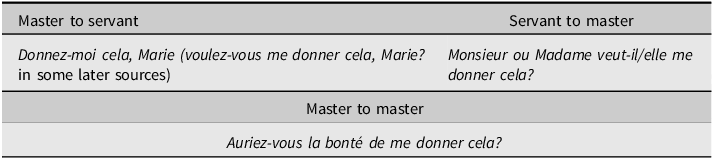

In sum, directive formulae benefitting the speaker (commands, request) reflect rigid class distinctions as if compartmentalised in sealed caissons – Paternoster (Reference Paternoster2023b) also uses the term compartmentalization. Traditionally, linguistic formulae for masters and servants remained rigidly distinct: imperatives were reserved for masters – softened by kind prosody – while servants were strictly banned from using them. Only from the 1870s do politeness formulae emerge, yet differences in pronouns, address titles and verb forms keep the two sets strictly apart. Moreover, the two sets of asymmetrical formulae remain also distinct from the ones routinely used among peers. Table 4 visualises the compartmentalization.

Table 4. Formulae for asymmetrical and symmetrical speaker-benefitting directives

Table 4 shows three distinct sets of formulae for three different contextual frames reflecting discernment politeness where linguistic choices are dictated by context and power dynamics. This supports Guiral & Thuillier’s characterisation of nineteenth-century France domestic service as reflecting a “société des castes” (Reference Guiral and Thuillier1978: 13), but extending it to language use.

Last, but not least, the very presence of prefabricated formulas in conduct, etiquette, and specialized advice literature supports the frame-based theory (Terkourafi, Reference Terkourafi2001, Reference Terkourafi2002, Reference Terkourafi, Kühnlein, Hannes and Zeevat2003, Reference Terkourafi2005a, Reference Terkourafi, Marmaridou, Nikiforidou and Antonopoulou2005b). Frame-based theory posits that speakers navigate social interactions through prepatterned linguistic choices, where default politeness emerges from repeated contextual use. The internal consistency of these formulae across sources provides strong empirical support for their real-life conventionalization for three different contextual frames. Since their pedagogical goal is to codify existing norms, authors would have had little reason to introduce arbitrarily invented formulas. They observed linguistic regularities, incorporating them into prescriptive discourse, because they understood that these formulae had the potential to facilitate social life for their readers. In 1890, a mistress struggling with rapid servant turnover could have raised wages or/and turned to various manuals for guidance on retaining her staff. Some recommended kindly spoken imperatives, others politeness formulae. But if she leaned towards the latter, she would have found consistency across sources (as we now know), reinforcing the idea that these formulae were the norm. This perceived uniformity may have encouraged her to adopt the polite forms, further cementing their codification and spread.

6. Concluding Remarks

This study has introduced a new method: extracting politeness formulae from prescriptive literature, providing a structured approach to the study of conventionalized language use in historical pragmatics that does not rely on large-scale linguistic corpora alone. I have shown that etiquette books, conduct books and specialized guides contain rich metapragmatic data – politeness rules alongside conventionalised expressions. The introduction of the term “formulary” provides a way to conceptualise and categorize these linguistic formulae, distinguishing them from politeness strategies by anchoring them in discernment and frame-based theory.

One key takeaway is that politeness formulae for master-servant interactions in nineteenth-century France reflect a shift in asymmetrical discourse, which appears to have been accelerated by the domestic labour market becoming increasingly free. While previous research (Piette Reference Piette2000) has linked the rise of politeness in domestic service to its crisis years, my sources confirm this for politeness formulae, but they also suggest that the call for a kind prosody was emerging a lot earlier. Rather than reflecting a genuine reduction in social stratification, these formulae operated more as paying lip service to equality: by masking Potestas (‘authority’) under a veneer of politeness, they allowed employers to frame their authority in more palatable terms while still maintaining control. I have argued that these politeness formulae do not change the command in a prototypical request, and the imperative remains largely conventional, even though the recommendation is for a kind prosody. Discernment is upheld thanks to compartmentalization of formulae for different power dynamics.

By applying recent theorization on discernment and conventionalization, this study has further demonstrated that etiquette and conduct books are useful tools for historical (im)politeness research. These sources contain numerous formulae not just for commands, but also for offers, apologies, advice, assertions, compliments, greetings and so on, making them highly valuable linguistic repositories. Given their prescriptive nature, they provide an explicit account of what was perceived as normative language use in various social contexts.

At the same time, this study acknowledges the limitations of corpus selection. The overrepresentation of sources from the later decades of the nineteenth century reflects the editorial success of the genre, but it limits diachronic analysis, making it difficult to precisely trace the diachrony of politeness formulae. Additionally, while conduct and etiquette books offer prescriptive norms, early conventionalization of the formulary (which here was inferred from consistency) requires further corroboration with other historical corpora.

While such a comparison lies beyond the scope of the current study, I fully agree that this is a fruitful avenue for future research, which would offer a valuable complementary perspective. By establishing an inventory of politeness formulae, the formulary introduced in this study provides a ready-made list of search terms for future corpus-based research, allowing scholars to systematically investigate the spread and evolution of these formulae over time. One advice text confirms a descriptive use of a prescriptive formula noted in Table 1. The formula is used in a conduct book by La Comtesse Dash (Reference Dash1868 2), whose rules for master-servant interaction only concern a ban of a harsh and haughty tone (Section 5.2). In a chapter called L’étiquette (‘Etiquette’) the author advises concealing frustration when servants make clumsy mistakes. She illustrates this with a story. At an informal dinner, the servant accidentally spills a dark sauce on a young officer’s brand new and costly white uniform. Furious and ready to strike with his napkin, the officer catches his colonel’s eye, realizes the consequences, and instantly composes himself. He calmly hands his napkin to the servant, saying in a charming manner: “Voulez-vous bien essuyer mon dolman, – s’il vous plaît?” (‘Would you be so kind as to wipe my dolman, please?’) (Dash Reference Dash1868 2: 104). Everyone laughs while his wit and restraint impress the colonel and his wife, who later gifts him a beautifully embroidered new uniform. This anecdotal example, though drawn from a conduct book, illustrates the kind of descriptive evidence that frequency-based corpus research can offer.

Combining qualitative extraction methods in prescriptive politeness metadiscourse with theoretical models of discernment, Potestas, and frame-based conventionalization, this approach furthers the integration of pragmatic theory with historical accounts of what politeness is and does.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.