Introduction

Communication lies at the core of organizational functioning, and without it, an organization cannot exist (Cooren & Martine, Reference Cooren, Martine, Jensen, Craig, Pooley and Rothenbuhler2016; Schoeneborn et al., Reference Schoeneborn, Kuhn and Kärreman2019). Despite its fundamental role, most research to date has focused on for-profit organizations, leaving a significant knowledge gap in the context of non-profit entities such as professional associations (Fernandez & Castellanos, Reference Fernandez and Castellanos2024; Potnis et al., Reference Potnis, Gala, Seifi, Warraich, Lamba and Reyes2024; Tschirhart & Gazley, Reference Tschirhart and Gazley2014). Nevertheless, effective internal communication is equally vital in these settings because it fosters collaboration, supports professional development, and enhances the organization’s overall impact.

Professional associations are organizations of competent professionals seeking common advancement (Merton, Reference Merton1958), defined as “organizing bodies for fields of professional practice” (Hager, Reference Hager2014, 40S). These associations represent a significant subset of nonprofit organizations and are an indispensable component of professionalism (Friedman & Afitska, Reference Friedman and Afitska2023). They serve to safeguard the interests of their members while advocating for the public interest by ensuring professional competence and ethical conduct (Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013). In these associations, the recipients of internal communication are not employees, but members formally employed elsewhere. Professional associations like the Medical Chamber have member-oriented communication similar to internal communication due to their unique structure. Members play an active role in the association, including evaluating candidates, managing branches and member networks, and participating in the governing body (Hager, Reference Hager2014). They are internal stakeholders who influence the organization through participation, leadership, and decision-making (Friedman & Afitska, Reference Friedman and Afitska2023). Professional associations rely on members for benefits co-production (Hager, Reference Hager2014, 41S). Members are integral to governance and value creation, so their communication needs are internal. We will, therefore, use the concept of internal communication to refer to the structured communication processes that connect professional associations with their members.

The nature of professional medical associations and the status of their members present unique challenges for these organizations in the communication sense. This is particularly true given that members are expected to engage without being financially compensated for their efforts (Friedman & Afitska, Reference Friedman and Afitska2023) and even pay membership fees that are an essential source of funding for the association (Gazley & Dignam, Reference Gazley and Dignam2010; Oh & Ki, Reference Oh and Ki2019). In such settings, effective communication is crucial for motivating, engaging and aligning members with the organization’s activities, goals and ethical and professional standards (e.g., Miao et al., Reference Miao, He, Pan and Huang2024; Potnis et al., Reference Potnis, Gala, Seifi, Warraich, Lamba and Reyes2024; Wang & Ki, Reference Wang and Ki2018).

The existing literature on professional associations covers various topics essential for maintaining organizational coherence and smooth functioning. These include charitable giving (Hung & Hager, Reference Hung and Hager2020), member engagement and motivation (Wang & Ki, Reference Wang and Ki2018), volunteerism (Nesbit & Gazley, Reference Nesbit and Gazley2012), membership benefits (Garrison & Cramer, Reference Garrison and Cramer2021), retention (Ki, Reference Ki2018), commitment (Rodríguez-Rad & del Rio-Vázquez, Reference Rodríguez-Rad and del Rio-Vázquez2023), professionalization (Fernandez & Castellanos, Reference Fernandez and Castellanos2024), and various factors that shape organizational identification (Miao et al., Reference Miao, He, Pan and Huang2024). However, limited attention has been given to the relationship between associations and their members, particularly regarding the role of communication and its outcomes (Miao et al., Reference Miao, He, Pan and Huang2024; Rodríguez-Rad & del Rio-Vázquez, Reference Rodríguez-Rad and del Rio-Vázquez2023; Wang & Ki, Reference Wang and Ki2018).

Just as effective internal communication is vital for businesses, it also plays a crucial role in professional associations. It contributes to greater member satisfaction and positively influences their perceptions and behaviors. Since these associations are established to serve their members, satisfaction with internal communication is paramount (Potnis et al., Reference Potnis, Gala, Seifi, Warraich, Lamba and Reyes2024). Satisfaction with internal communication is not only a key dimension of internal communication itself (Sinčić Ćorić et al., Reference Sinčić Ćorić, Pološki Vokić and Tkalac Verčič2020), but it is also fundamental to an organization’s overall well-being and effectiveness (Downs & Adrian, Reference Downs and Adrian2004). To ensure optimal functioning, associations must foster a sense of commitment and identification among their members, a goal that can be advanced by satisfactory internal communication (Miao et al., Reference Miao, He, Pan and Huang2024; Rodriguez-Rad & Del Rio-Vazquez, Reference Rodríguez-Rad and del Rio-Vázquez2023).

The aim of this study is to examine the impact of satisfaction with internal communication on membership satisfaction, professional identification, and identification with professional association. It provides new insights into how effective internal communication enhances member–organization relationships, distinguishing it from the more commonly studied employee–organization dynamic. Additionally, it contributes to the organizational identification literature by demonstrating how internal communication can support multiple identification targets, including identification with the profession—an aspect particularly relevant to professional associations (Wang & Ki, Reference Wang and Ki2018). Finally, the study integrates various psychological concepts into a single framework, offering a deeper understanding of the underexplored context of professional associations.

Conceptual Background and Hypotheses

Internal Communication Satisfaction

Internal communication is an essential management function aiming to facilitate communication within organizations (Tkalac Verčič et al., Reference Tkalac Verčič, Verčič and Sriramesh2012). This communication can flow in various directions, including horizontal exchanges among peers, downward communication from superiors to subordinates, and upward communication from subordinates to superiors (Tkalac Verčič et al., Reference Tkalac Verčič, Galić and Žnidar2021). Internal communication channels encompass a variety of formats, including face-to-face channels (e.g., employee meetings), Intranet, print media, teleconferencing, electronic communication (e.g., emails), as well as social media (Men, Reference Men2015).

Satisfaction with internal communication is a result of internal communication practices within the organization (Carrière & Bourque, Reference Carriere and Bourque2009). It is defined as employees’ satisfaction with various aspects of communication in interpersonal, group, and organizational contexts (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Chuanig and Hsieh2009) and is an important factor influencing organizational members’ perceptions and behaviors. It encompasses individuals’ satisfaction with relationships and information flow within the organization (Downs & Hazen, Reference Downs and Hazen1977). Understanding satisfaction with internal communication is essential, as it directly affects organizational and individual outcomes.

Employees are more likely to be satisfied with their work if they perceive that they receive adequate informational support within the workplace (Kalemci Tuzun, Reference Tuzun2013). Consistent with this notion, research has established a positive correlation between internal communication satisfaction and several key outcomes. These include enhanced employee engagement (Welch, Reference Welch2019), increased employer attractiveness (Tkalac Verčič et al., Reference Tkalac Verčič, Galić and Žnidar2021), improved job performance (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Chuanig and Hsieh2009), greater organizational trust (Pološki Vokić et al., Reference Pološki Vokić, Rimac Bilušić and Najjar2021), higher employee commitment (Ammari et al., Reference Ammari, Kurdi, Alshurideh, Obeidat, Hussien and Alrowwad2017), elevated job satisfaction (Enyan et al., Reference Enyan, Bangura, Mangue and Abban2023; Nikolić et al., Reference Nikolić, Vukonjanski, Nedeljković, Hadžić and Terek2013), stronger organizational identification (Krywalski Santiago, Reference Krywalski Santiago2020), and increased overall life satisfaction (Sinčić Ćorić et al., Reference Sinčić Ćorić, Pološki Vokić and Tkalac Verčič2020). Conversely, Hargie et al. (Reference Hargie, Tourish and Wilson2002) discovered that low communication satisfaction was linked to diminished commitment, elevated absenteeism, and elevated employee turnover.

Membership Satisfaction

Discrepancy theory focuses on the difference between what is expected or desired and what is actually experienced. It examines how these gaps (i.e., discrepancies) influence perceptions, emotions, and overall satisfaction (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Klein, Saunders, Dwivedi, Wade and Schneberger2012). In the context of professional associations, members’ attitudes are influenced by how well their perceptions of the association align with their expectations (Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013). In other words, when the association offers benefits that meet or exceed their expectations, members are more likely to be satisfied and willing to renew their memberships (Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013, p. 496). Thus, membership satisfaction refers to a member’s positive attitude toward the professional association and the value it provides (Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013). This value, which can be personal, professional, tangible or symbolic, is shaped by the perceived alignment between the services offered and communicated by the association and members’ needs and expectations (Ki & Wang, Reference Ki and Wang2016; Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013).

For professional associations, which typically do not offer financial compensation like other organizations, providing both tangible and symbolic benefits is essential for meeting members’ expectations (Wollebaek, Reference Wollebaek2009). Tangible benefits may include information dissemination, professional development opportunities such as conferences, networking, mentoring, and career advancement resources (Akimova & Medvedeva, Reference Akimova and Medvedeva2020; Fisher, Reference Fisher1997; Garrison & Cramer, 2020; Goldman, Reference Goldman2014; Henczel, Reference Henczel2014). While financial benefits may also be provided (Soito & Jankowski, Reference Soito and Jankowski2023), the primary goal is offering meaningful non-financial rewards. In this context, professional associations rely on effective communication to demonstrate the value of membership.

The literature emphasizes the importance of meeting the expectations of internal stakeholders as key to organizational success (e.g., Akeshova, Reference Akeshova2023; Ford & Heaton, Reference Ford and Heaton2000). Hecht’s theory of discriminative fulfillment (1978a, 1978b) suggests that satisfaction results when expectations are met, with the discriminative stimulus (the expectation) being fulfilled through environmental reinforcement. A member’s satisfying communication encounters within an organization lead to their overall satisfaction with the organization. In this context, communication with various aspects of the organization acts as the discriminative stimulus, triggering response behaviors that receive positive reinforcement (Taylor, Reference Taylor1997). Taylor (Reference Taylor1997) applied this theory to non-profit organizations, noting that open, rewarding communication fosters satisfaction by fulfilling the expectations of members. This framework is applicable to professional associations that must demonstrate the value of membership to their members, and this can be accomplished via communication.

Therefore, based on the above, we hypothesize:

H1

The higher the satisfaction with internal communication, the higher the satisfaction with membership in the professional association.

Organizational and Professional Identification

While internal communication within an organization can provide tangible benefits to members, one of the key symbolic benefits is a sense of belonging and identification with the organization (Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013). Membership in a professional group is not just an occupational label; it also allows individuals to define themselves and connect with a social group (Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013). Social identity theory suggests that individuals define themselves based on group membership and the value they attach to it (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel and Tajfel1978, 63). In professional associations, identification with both the association and the profession is particularly significant. Strong psychological attachment to the professional association is essential for fostering a successful, mutually beneficial relationship (Rodríguez-Rad & del Rio-Vázquez, Reference Rodríguez-Rad and del Rio-Vázquez2023). Additionally, professional associations help maintain professional identity and uphold the profession’s standards (Friedman & Afitska, Reference Friedman and Afitska2023). Professional identity is crucial for behavior, success, and well-being, and professional associations play a key role in shaping and maintaining it (van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Querido, Wijnen-Meijer, van Dijk and Ten Cate2020).

Identification with a professional association can be viewed as a form of social identification (Ashforth & Mael, Reference Ashforth and Mael1989), providing individuals with a sense of self-definition (van Knippenberg & Sleebos, Reference Van Knippenberg and Sleebos2006) and a connection to the organization as a social unit (Karanika-Murray et al., Reference Karanika-Murray, Duncan, Griffiths and Pontes2015; Podnar & Golob, Reference Podnar and Golob2015). Research consistently shows that individuals with strong organizational identification are more motivated to engage with their group both directly and indirectly and perform beyond their immediate tasks (e.g., Finch et al., Reference Finch, Abeza, O’Reilly and Hillenbrand2018).

Studies have also established a link between organizational identification and overall satisfaction with the organization, including job satisfaction (Pham, Reference Pham2020). According to social identity theory, identification fulfills needs for security, belonging, and self-improvement and provides a sense of “purpose.” Researchers, including Karanika-Murray et al. (Reference Karanika-Murray, Duncan, Griffiths and Pontes2015) and Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Park and Koo2015), have demonstrated a significant positive relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction. Based on these findings, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2

The stronger an individual’s identification with a professional association, the higher their satisfaction with membership in that association.

Professional identity, related to identification with a professional association, is a key component of an individual’s social self (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2020). While there is no universally agreed-upon definition of professional identity (Terum & Heggen, Reference Terum and Heggen2016), it can be understood as the extent to which an individual identifies with their profession and its core characteristics (Van Maanen & Barely, Reference Van Maanen and Barley1984). Professional identity encompasses traits, beliefs, values, and skills that define individuals in their professional roles and distinguish them from other professions (Maginnis, Reference Maginnis2018). For this study, professional identification is defined as an individual’s sense of connection to their profession and the extent to which they identify with its characteristics (Bartels et al., Reference Bartels, Peters, de Jong, Pruyn and van der Molen2010). Identification with a profession can confer status, rewards, and career advancement opportunities (Ashforth & Johnson, Reference Ashforth, Johnson, Hogg and Terry2001) and serve as a source of collective strength (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2020).

Van Oeffelt et al. (Reference van Oeffelt, Ruijters, van Hees, Simons, Black, Warhurst and Corlett2018) developed a model of professional identification that includes professional knowledge and learning as key components of the professional self. Effective internal communication by the professional association can be a critical tool for disseminating the association’s values and goals, as well as for helping members to internalize the profession’s core values (Forouzadeh et al., Reference Forouzadeh, Kiani and Bazmi2018). Bartels et al. (Reference Bartels, Peters, de Jong, Pruyn and van der Molen2010) also demonstrated that internal communication influences professional identification. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3

The higher the satisfaction with internal communication, the stronger the individual’s identification with the profession.

Internal communication fosters a sense of higher-order organizational identification, such as corporate identification, among employees (Krywalski Santiago, Reference Krywalski Santiago2020). Empirical evidence indicates that communication satisfaction is positively related to organizational identification across various professions, including teachers, managers, insurance employees, academics, and sports science students (Derin & Tuna, Reference Derin and Tuna2017; Kalemci Tuzun, Reference Tuzun2013; Nakra, Reference Nakra2006; Ozturk & Soyturk, Reference Ozturk and Soyturk2021; Yildiz, Reference Yıldız2013).

Internal communication plays a crucial role in strengthening employees’ identification with their organization (Nakra, Reference Nakra2006). When employees perceive that they have contributed to the development of shared meaning within the organization, they are more likely to experience a sense of belonging and commitment. Furthermore, positive communication experiences are linked to other organizational concepts, such as organizational commitment and belongingness, which further enhance employee identification (e.g., Ammari et al., Reference Ammari, Kurdi, Alshurideh, Obeidat, Hussien and Alrowwad2017; Carriere & Bourque, Reference Carriere and Bourque2009; Derin & Tuna, Reference Derin and Tuna2017). Empirical studies have also demonstrated a positive relationship between communication climate and organizational identification (Bartels et al., Reference Bartels, Pruyn, de Jong and Joustra2006, Reference Bartels, Peters, de Jong, Pruyn and van der Molen2010; Neill et al., Reference Neill, Men and Yue2020). Based on the above, we propose:

H4

The higher the satisfaction with internal communication, the stronger the individual’s identification with the professional association.

Satisfaction with internal communication has both a direct and indirect effect on membership satisfaction, with identification with a professional association acting as a mediator. Satisfactory internal communication is key to organizational identification, as it aligns employees’ values and goals with those of the organization and helps to reduce uncertainty about their role within the organization (Nakra, Reference Nakra2006). On the other hand, organizational identification—representing a symbolic membership value (Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013)—is found to be related to several positive outcomes, such as job satisfaction (Karanika-Murray et al., Reference Karanika-Murray, Duncan, Griffiths and Pontes2015). To summarize, when members are satisfied with internal communication, they identify more strongly with the association, which subsequently enhances their overall satisfaction with membership.

H5

Identification with a professional association mediates the relationship between satisfaction with internal communication and satisfaction with membership.

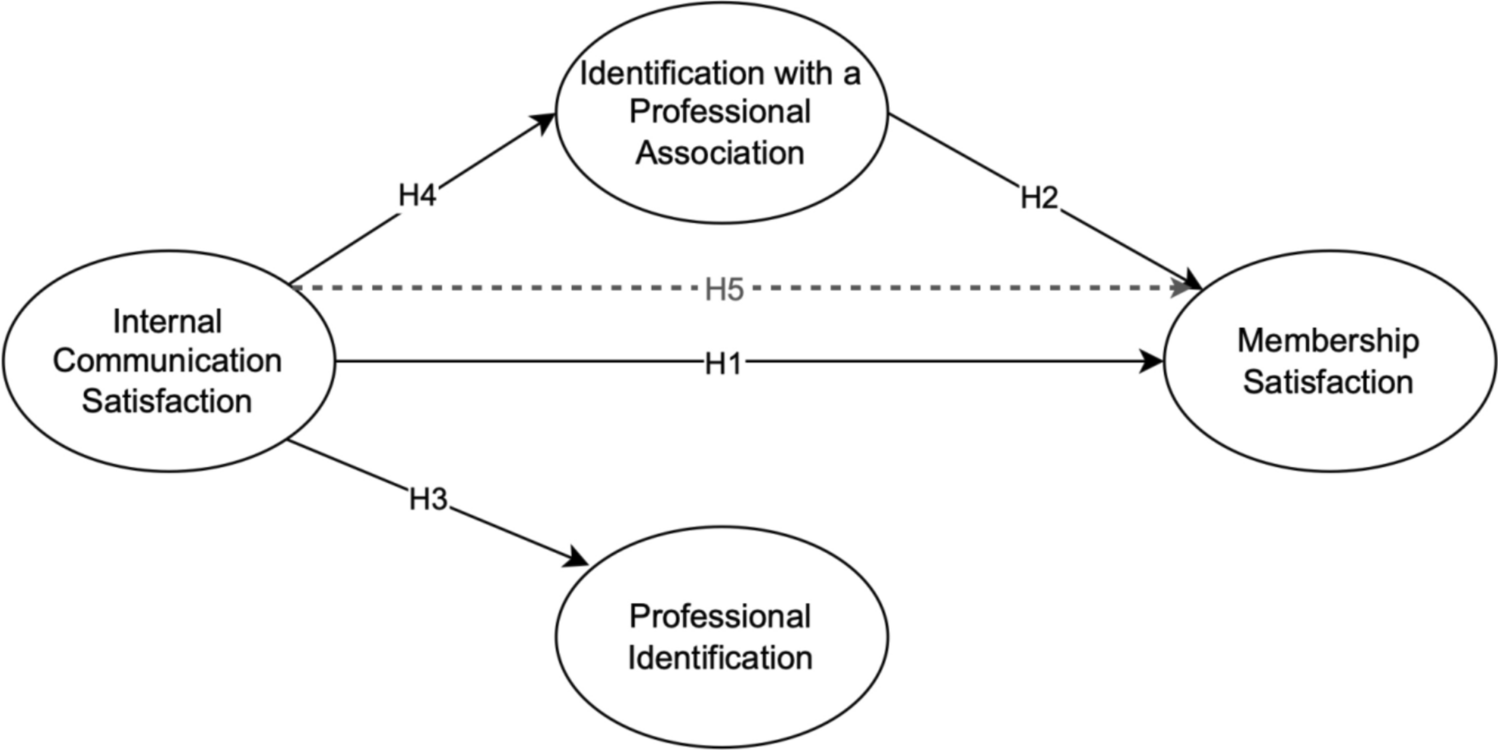

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of this study, summarizing all hypotheses derived from the literature review and illustrating the proposed relationships between internal communication satisfaction, membership satisfaction, professional identification, and identification with the professional association. The mediation relationship is illustrated with a dashed arrow.

Fig. 1 Conceptual model and hypotheses

Methodology

Sample, and Data Collection

An online survey was conducted among 10,285 members of the Slovenian Medical Chamber, a mandatory professional association for physicians and dentists in Slovenia, with over 11,000 members. Membership is required by law for those practicing medicine, similar to other European countries like Germany, Austria, Poland, and France (Bautista & Lopez-Valcarcel, Reference Bautista and López-Valcárcel2019). The Chamber represents physicians, upholds professional standards, and regulates the medical profession in Slovenia, including licensing, internships, and providing professional supervision. It also promotes member involvement in governance, with elected leadership, including a president who is a practicing physician.

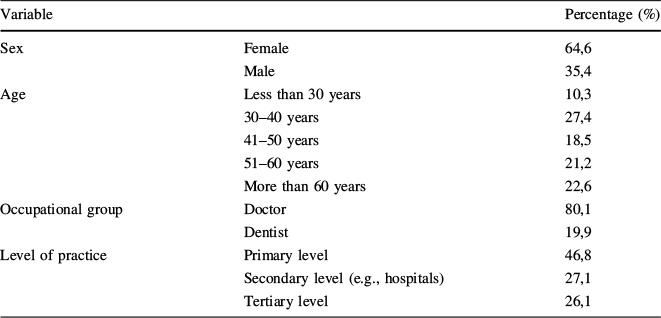

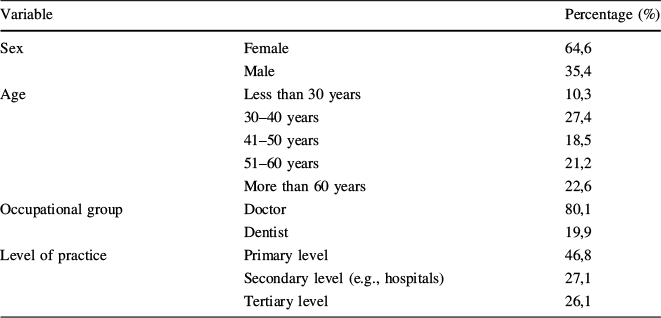

A total of 1,214 members responded to the survey (11.8% response rate), with 956 completing the questionnaire in full. The survey was distributed to all active Chamber members who have opted in to receive the Chamber newsletter. The final sample is representative of the Chamber’s overall membership, with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. The sample demographics closely match the Chamber’s overall membership. Respondents were predominantly female (64.6%) and aged 30 to 40 (27.4%), followed by those over 60 (22.6%) and 51 to 60 (21.2%). The smallest group was physicians under 30 (10.3%). Among physicians, 48.8% were specialists, while 78% of dentists were primary care providers (Table 1).

Table 1 Sample characteristics

|

Variable |

Percentage (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Sex |

Female |

64,6 |

|

Male |

35,4 |

|

|

Age |

Less than 30 years |

10,3 |

|

30–40 years |

27,4 |

|

|

41–50 years |

18,5 |

|

|

51–60 years |

21,2 |

|

|

More than 60 years |

22,6 |

|

|

Occupational group |

Doctor |

80,1 |

|

Dentist |

19,9 |

|

|

Level of practice |

Primary level |

46,8 |

|

Secondary level (e.g., hospitals) |

27,1 |

|

|

Tertiary level |

26,1 |

|

Measures

The research instrument included multi-item construct indicators, all measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Satisfaction with internal communication was assessed using items developed by the authors in consultation with the chamber’s public relations director. Membership satisfaction was measured with a scale adapted from Alpern et al. (Reference Alpern, Canavan, Thompson, McNatt, Tatek, Lindfield and Bradley2013). Identification with a professional association was measured using an adaptation of corporate identification (Podnar & Golob, Reference Podnar and Golob2015). Professional identification was assessed using the Professional Identity Questionnaire (PIQ) adapted from Barbour and Lammers (Reference Barbour and Lammers2015), and the version used by Toben et al. (Reference Daan, Van der Vossen, Anouk and Kusurkar2021) for medical students. In addition to these variables, perceived external prestige (PEP) was included as a control variable to account for its potential influence on identification with the professional association. PEP measures members’ perceptions of how their professional association is viewed externally and was captured with items based on Mael and Ashforth’s (Reference Mael and Ashforth1992) instrument. All adapted indicators were reviewed by two independent researchers. The items for all variables and their correlations can be found in Appendices.

Perceived External Prestige as a Control Variable

As mentioned above, PEP refers to an individual’s perception of the organization’s reputation in society (Smidts et al., Reference Smidts, Van Riel and Pruyn2001). Given its established influence on organizational identification, we introduce PEP as a control variable to isolate the effects of satisfaction with internal communication and professional identity. According to social identity theory (Dutton et al., Reference Dutton, Dukerich and Harquail1994), individuals derive pride from belonging to organizations that are highly regarded, as this enhances their sense of self. Furthermore, individuals are more likely to identify with organizations that are viewed positively by others, as this reinforces the uniqueness of their own identity and self-image (Terry, Reference Terry, Hogg and Terry2001). The greater the PEP, the greater the potential for individuals to enhance their self-esteem through identification with the organization (Mishra, Reference Mishra2013; Smidts et al., Reference Smidts, Van Riel and Pruyn2001). Empirical studies have consistently demonstrated a positive relationship between PEP and organizational identification (e.g., Podnar, Reference Podnar2011; Sušanj Šulentić et al., Reference Sušanj Šulentić, Žnidar and Pavičić2017). Accordingly, in order to isolate the effects of other predictors of identification with the professional association, PEP is included as a control variable.

Data Analysis

We used SmartPLS 4.0 Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) software to test the reflective research model. Given the limited theoretical development on satisfaction with internal communication, professional identity, and professional associations, PLS is well-suited for this study as it is effective in the early stages of theory development (Tsang, Reference Tsang2002).

Following Leguina’s (Reference Leguina2015) two-step approach, we first assessed the outer model for convergent and discriminant validity. The data were checked for missing values, outliers, normality, and multicollinearity. We began by evaluating the measurement model, including all indicators. After conducting an initial PLS-SEM analysis, we removed indicators with factor loadings below 0.7, as they contributed minimally to the model’s explanatory power and risked biasing parameter estimates (Aibinu & Al-Lawati, Reference Aibinu and Al-Lawati2010). After refining the model, we assessed reliability using Fornell and Larcker’s (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981) composite reliability measure, which is preferred over Cronbach’s alpha in PLS analysis (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006), although both were calculated. Convergent validity was confirmed, with all average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeding 0.50, as recommended by Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). We also tested discriminant validity using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT).

Next, the inner model was evaluated to test the hypotheses. Using bootstrapping with 5,000 subsamples, we assessed the R2 coefficient and tested the path coefficients, t-statistics, p values, effect sizes, and the indirect effect of identification with the professional association on membership satisfaction through satisfaction with internal communication. Hypotheses were confirmed if the p value was below the 0.05 significance level.

To enhance the robustness of our model and account for alternative explanations, we included a control variable, PEP, which helps reduce error variance and improves the precision of our estimates (De Battisti & Siletti, Reference De Battisti, Siletti, Arbia, Peluso, Pini and Rivellini2019). We tested two models: a primary model without the control variable and a control model incorporating PEP. Testing a primary model and a control model separately while using the PLS-SEM approach allowed us to see the unique effects of internal communication satisfaction and PEP without being forced into a fixed order of variable entry, as hierarchical regression would require. This gave us a clearer picture of how satisfaction with internal communication influences identification and membership satisfaction while accounting for external prestige effects. In addition, PLS-SEM makes it easier to assess indirect effects and mediation, which helps us to interpret the results in a more meaningful way.

To ensure that multicollinearity does not bias our results, we assessed the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all predictor variables (see Appendix 1). The VIF values for internal communication satisfaction and PEP were well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5 (Hager, Reference Hager2014). These results indicate that multicollinearity is not a significant problem and that both constructs contribute uniquely to the model.

Results

Reliability and Validity of the Proposed Measurement Models

All variables exhibited an approximately normal distribution, as indicated by skewness and kurtosis coefficients within the range of − 1 to + 1. The variance inflation factor (VIF) calculation demonstrated that multicollinearity is not a significant issue (see Appendix 1).

The reliability coefficients of all composite factors were well above the threshold of 0.7, with values ranging from 0.868 to 0.946. The coefficients Alpha ranged from 0.798 to 0.929 and AVE values were between 0.623 and 0.780 (see Appendix 1) thus the research model can be considered sufficiently reliable.

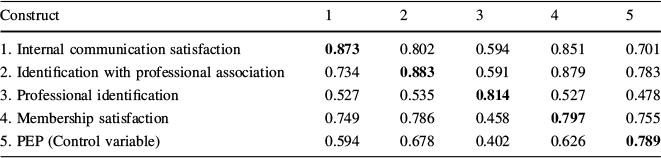

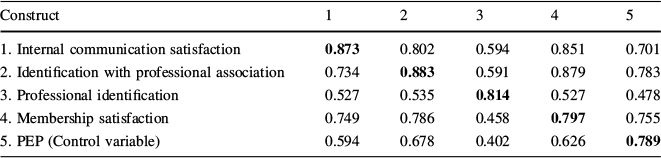

The HTMT ratios for discriminant validity were all deemed acceptable, as they were below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.90 (Henseler et al., Reference Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt2015). The Fornell–Larcker criterion values demonstrated that zero-order correlations did not exceed the AVE squared root values indicating reasonable construct validity across the measures (see Table 2).

Table 2 Fornell–Larcker criterion, zero-order correlations and HTMT

|

Construct |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Internal communication satisfaction |

0.873 |

0.802 |

0.594 |

0.851 |

0.701 |

|

2. Identification with professional association |

0.734 |

0.883 |

0.591 |

0.879 |

0.783 |

|

3. Professional identification |

0.527 |

0.535 |

0.814 |

0.527 |

0.478 |

|

4. Membership satisfaction |

0.749 |

0.786 |

0.458 |

0.797 |

0.755 |

|

5. PEP (Control variable) |

0.594 |

0.678 |

0.402 |

0.626 |

0.789 |

HTMT values are shown above the diagonal, the square root of AVE is presented in bold on the diagonal, and zero-order correlations are presented below the diagonal

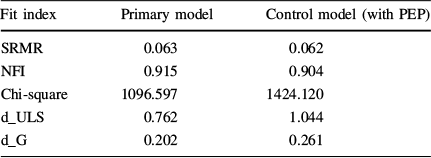

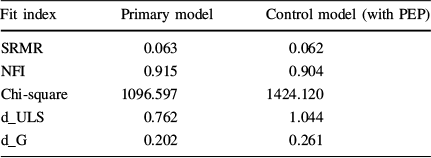

Lastly, the model fit was assessed with SRMR, NFI, Chi-Square, as well as d_ULS and d_G values (Henseler et al., Reference Henseler, Hubona and Ray2016). Both models—primary and control—indicated a good overall fit, with no major concerns related to the model’s ability to represent the data (see Table 3).

Table 3 Model fit indices for estimated models

|

Fit index |

Primary model |

Control model (with PEP) |

|---|---|---|

|

SRMR |

0.063 |

0.062 |

|

NFI |

0.915 |

0.904 |

|

Chi-square |

1096.597 |

1424.120 |

|

d_ULS |

0.762 |

1.044 |

|

d_G |

0.202 |

0.261 |

Hypotheses Tests

The results show that both membership satisfaction and identification with the professional association have high R2 values, indicating that the independent variables explain a substantial portion of the variance in the dependent variable. Specifically, satisfaction with internal communication and identification with the professional association together account for a large portion of the variance in membership satisfaction (R2 = 0.682). Additionally, satisfaction with internal communication alone explains approximately 54% of the variance in identification with the professional association (R2 = 0.538). Lastly, satisfaction with internal communication accounts for more than 27% of the variance in professional identification (R2 = 0.278), indicating a moderate effect.

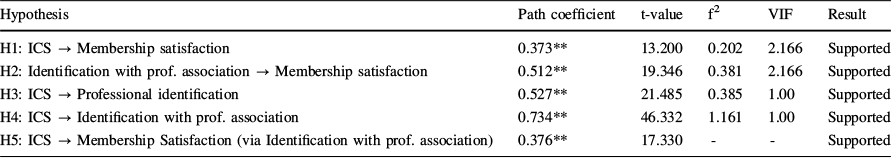

To assess the hypotheses, we examined the magnitude, statistical significance, and direction of the path coefficients (β). As shown in Table 4, all path coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Table 4 Model path analysis, VIF and effect size

|

Hypothesis |

Path coefficient |

t-value |

f2 |

VIF |

Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H1: ICS → Membership satisfaction |

0.373** |

13.200 |

0.202 |

2.166 |

Supported |

|

H2: Identification with prof. association → Membership satisfaction |

0.512** |

19.346 |

0.381 |

2.166 |

Supported |

|

H3: ICS → Professional identification |

0.527** |

21.485 |

0.385 |

1.00 |

Supported |

|

H4: ICS → Identification with prof. association |

0.734** |

46.332 |

1.161 |

1.00 |

Supported |

|

H5: ICS → Membership Satisfaction (via Identification with prof. association) |

0.376** |

17.330 |

- |

- |

Supported |

**p < .001; ICS internal communication satisfaction; H5 path coefficient shows indirect effect

The strongest effect was found between satisfaction with internal communication and identification with the professional association (β = 0.734). Satisfaction with internal communication also had a significant effect on professional identification (β = 0.527). Similarly, identification with the professional association significantly related to membership satisfaction (β = 0.512). In contrast, the effect of satisfaction with internal communication on membership satisfaction was moderate (β = 0.373).

We tested the mediating role of identification in the relationship between satisfaction with internal communication and membership satisfaction. The results revealed a moderate indirect effect, (β = 0.376, p < 0.001, t = 17.330), which is barely noticeably larger than the direct effect between satisfaction with internal communication and membership satisfaction as reported above. This indicates partial mediation, where both direct and indirect paths contribute to the overall relationship (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). The total effect of internal communication satisfaction on membership satisfaction was found to be β = 0.749.

Control Model

A second model including a control variable PEP was estimated to assess the impact of external prestige (De Battisti & Siletti, Reference De Battisti, Siletti, Arbia, Peluso, Pini and Rivellini2019). The inclusion of the control variable slightly increased the R2 value. With both internal communication satisfaction and PEP included, the variance explained in identification with the professional association is R2 = 0.628, compared to the primary model without PEP (R2 = 0.538).

Additionally, the path between satisfaction with internal communication and identification with the professional association became slightly less significant when the control variable was included (β = 0.511, p < 0.001 vs. β = 0.734, p < 0.001 in the primary model). However, this change was minimal and does not substantially alter the core conclusions, suggesting that the primary model remains robust, with the control variable contributing additional explanatory power.

Discussion

This study provides new insights into the role of internal communication within professional associations, highlighting its influence on both professional identification and membership satisfaction. While previous research (e.g., Enyan et al., Reference Enyan, Bangura, Mangue and Abban2023; Kang & Sung, Reference Kang and Sung2017; Nikolić et al., Reference Nikolić, Vukonjanski, Nedeljković, Hadžić and Terek2013; Pološki Vokić et al., Reference Pološki Vokić, Rimac Bilušić and Najjar2021) has demonstrated that effective internal communication enhances organizational outcomes, our findings extend this by showing its direct impact on both member satisfaction and identification with the association.

By confirming that satisfaction with internal communication is a key factor in shaping members’ perceptions of value, this study advances the theoretical understanding of membership outcomes. Drawing on discrepancy theory (Markova et al., Reference Markova, Ford, Dickson and Bohn2013) and discriminative fulfillment theory (Hecht, Reference Hecht1978a, Reference Hecht1978b), we show that communication satisfaction is not only about material benefits, but also about how well it meets members’ broader expectations and needs. Specifically, our findings suggest that internal communication bridges the gap between members’ expectations and their actual experiences. When communication meets or exceeds expectations, it reinforces members’ perceptions of value and fosters satisfaction. Moreover, consistent with discriminative fulfillment theory, effective internal communication strengthens professional identity by reinforcing members’ roles and fulfilling their psychological needs, further enhancing satisfaction with membership.

Beyond satisfaction, our study highlights the role of internal communication in fostering professional identification. While members benefit from tangible resources such as information and career opportunities, our findings suggest they also derive value from the intangible sense of belonging and shared professional identity. Effective communication helps members internalize the values and goals of the association (Forouzadeh et al., Reference Forouzadeh, Kiani and Bazmi2018), reinforcing their connection to the profession. While previous studies have established the link between communication and organizational identification, few have explored its role in shaping professional identity—an identification that extends beyond the association to the broader profession. Our study addresses this gap, showing that when members are satisfied with internal communication, they are more likely to integrate the profession’s goals and values into their own professional self-concept.

In addition, our findings reveal the mediating role of identification with the professional association in the relationship between internal communication satisfaction and membership satisfaction. This highlights the importance of identity formation within professional associations. By demonstrating that professional identification partially mediates this relationship, our study provides a more in-depth understanding of how communication builds value for members (e.g., Wang & Ki, Reference Wang and Ki2018).

Methodologically, this study advances research on professional associations by utilizing a two-model comparison. This approach allows us to distinguish between the direct effects of satisfaction with internal communication and the moderating influence of PEP, providing a more detailed understanding than traditional regression-based techniques. Additionally, by demonstrating the robustness of our findings across two models, we provide stronger empirical support for the role of satisfaction with internal communication in shaping both identification and membership satisfaction. This methodological strategy enhances our understanding of these well-established relationships by allowing for a more precise examination of the interplay between communication, identification, and PEP within professional associations.

Lastly, our inclusion of PEP as a control variable confirms its influence on professional identification, aligning with social identity theory (Dutton et al., Reference Dutton, Dukerich and Harquail1994). Members’ perceptions of their association’s prestige shape their emotional attachment and identification, a finding consistent with prior research (e.g., Mael & Ashforth, Reference Mael and Ashforth1992). Moreover, our results illustrate the dynamic interplay between internal communication, external prestige, and identification in the context of professional associations, further strengthening our understanding of these relationships.

Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

Theoretically, this study deepens our understanding of how internal communication shapes organizational and professional identities, particularly within the nonprofit sector. Unlike employees in traditional organizations, members of professional associations are not formally employed yet remain a critical internal public whose perceptions of and satisfaction with internal communication significantly impact the association’s success. Our findings contribute to the model of professional identification (van Oeffelt, 1997) by showing that internal communication serves as a key driver of both organizational and professional identification.

From a practical standpoint, professional associations should prioritize internal communication as a strategic tool to enhance member satisfaction and foster identification with the organization and profession. Associations should view their members as active stakeholders who derive both tangible and intangible value from their membership. Clear, consistent communication can help convey the association’s values, promote professional learning, and strengthen members’ emotional connection to the organization.

To maximize engagement, associations should implement communication strategies that go beyond merely addressing informational needs. Instead, they should actively reinforce professional identity and alignment with the profession’s broader goals. By doing so, they can cultivate a stronger sense of belonging, enhance member satisfaction, and ultimately strengthen the association’s long-term success.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, self-selection bias may have influenced the sample, as participants who were more engaged with association activities might have different perspectives than non-participants. Additionally, the findings may not be generalizable to all professional associations, particularly those with different legal structures. Since the study focused on doctors and dentists in a small European country, its results may not apply directly to other regions or professions. Future research could explore cross-cultural contexts to expand on these findings.

We acknowledge two important methodological limitations. First, while the instrument used to measure satisfaction with internal communication showed good reliability and validity in this study, future research could further refine and validate it by testing it in different samples or contexts. Second, while our two-model approach helps distinguish the effects of satisfaction with internal communication and PEP more clearly, it also has some trade-offs. Unlike hierarchical regression, which adds predictors sequentially, our approach does not explicitly test the incremental variance explained by each predictor. In addition, while PLS-SEM is well suited for structural modeling and mediation analysis, it lacks traditional goodness-of-fit indices commonly used in covariance-based SEM. Future research could build on our findings by incorporating alternative modeling approaches, such as multi-group analysis or longitudinal designs, to further validate these relationships.

Another limitation is the low member engagement often noted in the literature (e.g., Wang, Reference Wang2022). Future studies could examine how factors like motivation, engagement, and commitment relate to satisfaction with internal communication.

Finally, in highly specialized professions like medicine, multiple forms of identification (organizational, professional, and association-based) may overlap and influence one another. Questions about the hierarchical structure of these identities, their impact on psychological well-being, and their interactions remain unsolved. Future research focused on these issues would provide valuable insights into the complexities of professional identification.

Conclusion

This study highlights the critical role of satisfaction with internal communication in shaping member satisfaction, professional identification, and identification with professional associations, particularly in the context of the Medical Chamber of Slovenia. The results show that satisfactory internal communication not only increases members’ satisfaction with their association, but also strengthens their identification with both the professional association and the broader medical profession. Furthermore, the study highlights the mediating role of professional association identification in the relationship between internal communication satisfaction and member satisfaction, providing a richer understanding of how communication fosters value for members.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the President of the Medical Chamber of Slovenia, Prof. Dr. Bojana Beović, the General Secretary, Tina Šapec, and the Head of the PR Department, Andreja Basle, for their assistance in obtaining the data.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Appendix 1. CFA item loadings and reliability statistics

|

Variable |

Item |

Loadings |

VIF |

Cronbach Alpha |

AVE |

CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Internal communication satisfaction |

0.895 |

0.762 |

0.927 |

|||

|

The association provides me with important information necessary for doing my job |

0.882 |

2.777 |

||||

|

I trust the association to always keep me informed about all important matters in the field of medicine |

0.906 |

3.141 |

||||

|

I am satisfied with the communication of the association |

0.860 |

2.241 |

||||

|

The association’s communication (weekly bulletin, mailings, website, Isis magazine) is effective |

0.842 |

2.135 |

||||

|

Identification with the professional association |

0.929 |

0.780 |

0.946 |

|||

|

I am proud to be a member of the association |

0.897 |

3.226 |

||||

|

The values of the association, of which I am a member, are very similar to my own values |

0.870 |

2.791 |

||||

|

I feel that the future of the association is also my future |

0.882 |

3.134 |

||||

|

I can easily identify with the association |

0.919 |

4.028 |

||||

|

I would proudly wear the association’s name or logo in public (e.g., on a t-shirt, cap, etc.) |

0.845 |

2.437 |

||||

|

Professional identification |

0.872 |

0.663 |

0.907 |

|||

|

I believe I am a member of the medical profession |

0.739 |

1.504 |

||||

|

I am happy to belong to the medical profession |

0.836 |

2.544 |

||||

|

I positively identify with members of this profession |

0.865 |

2.840 |

||||

|

Being a member of the medical profession is very important to me |

0.829 |

2.120 |

||||

|

I feel I share certain characteristics with other members of this profession |

0.795 |

1.959 |

||||

|

Membership satisfaction |

0.856 |

0.635 |

0.897 |

|||

|

I receive the right amount of support and professional assistance from the association |

0.847 |

2.276 |

||||

|

With the help of the association’s professional training, I have gained new knowledge and skills necessary for performing my work |

0.773 |

1.732 |

||||

|

I am satisfied with the rules by which the association regulates the performance of my work based on public authorizations and legislation |

0.791 |

1.787 |

||||

|

Membership in the association offers me opportunities for career advancement |

0.745 |

1.654 |

||||

|

For the membership fee, I receive all the necessary help and support I need |

0.823 |

2.080 |

||||

|

Perceived external prestige |

0.798 |

0.623 |

0.868 |

|||

|

I believe that people in my community (family, friends, neighbors…) have a very good opinion of the association |

0.857 |

1.935 |

||||

|

I feel that people perceive membership in the association as prestigious |

0.777 |

1.616 |

||||

|

I feel that parents would be proud if their children were members of the association |

0.774 |

1.596 |

||||

|

I believe the association does not have a good reputation in my community. (R) |

0.746 |

1.466 |

Appendix 2. Correlation matrix of measurement items

|

ICS1 |

ICS2 |

ICS3 |

ICS4 |

OI1 |

OI2 |

OI3 |

OI4 |

OI5 |

PI1 |

PI2 |

PI3 |

PI4 |

PI5 |

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

MS4 |

MS5 |

PEP1 |

PEP2 |

PEP3 |

PEP4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ICS1 |

1.000 |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ICS2 |

0.771 |

1.000 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

ICS3 |

0.669 |

0.692 |

1.000 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

ICS4 |

0.639 |

0.685 |

0.634 |

1.000 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

OI1 |

0.585 |

0.640 |

0.612 |

0.578 |

1.000 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

OI2 |

0.548 |

0.607 |

0.583 |

0.521 |

0.738 |

1.000 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

OI3 |

0.537 |

0.574 |

0.542 |

0.492 |

0.727 |

0.712 |

1.000 |

||||||||||||||||

|

OI4 |

0.578 |

0.629 |

0.616 |

0.532 |

0.773 |

0.748 |

0.795 |

1.000 |

|||||||||||||||

|

OI5 |

0.504 |

0.549 |

0.536 |

0.506 |

0.705 |

0.649 |

0.665 |

0.726 |

1.000 |

||||||||||||||

|

PI1 |

0.390 |

0.412 |

0.399 |

0.422 |

0.402 |

0.341 |

0.368 |

0.380 |

0.351 |

1.000 |

|||||||||||||

|

PI2 |

0.319 |

0.358 |

0.319 |

0.357 |

0.372 |

0.307 |

0.312 |

0.324 |

0.355 |

0.516 |

1.000 |

||||||||||||

|

PI3 |

0.344 |

0.404 |

0.332 |

0.386 |

0.398 |

0.353 |

0.358 |

0.408 |

0.390 |

0.527 |

0.748 |

1.000 |

|||||||||||

|

PI4 |

0.364 |

0.424 |

0.369 |

0.393 |

0.454 |

0.402 |

0.400 |

0.437 |

0.413 |

0.481 |

0.617 |

0.631 |

1.000 |

||||||||||

|

PI5 |

0.345 |

0.391 |

0.347 |

0.367 |

0.417 |

0.380 |

0.391 |

0.423 |

0.412 |

0.431 |

0.555 |

0.628 |

0.631 |

1.000 |

|||||||||

|

MS1 |

0.572 |

0.601 |

0.627 |

0.516 |

0.630 |

0.558 |

0.561 |

0.612 |

0.510 |

0.298 |

0.277 |

0.286 |

0.316 |

0.308 |

1.000 |

||||||||

|

MS2 |

0.567 |

0.584 |

0.512 |

0.539 |

0.579 |

0.522 |

0.505 |

0.563 |

0.496 |

0.295 |

0.286 |

0.310 |

0.362 |

0.338 |

0.593 |

1.000 |

|||||||

|

MS3 |

0.542 |

0.545 |

0.543 |

0.442 |

0.582 |

0.547 |

0.571 |

0.614 |

0.516 |

0.298 |

0.280 |

0.291 |

0.302 |

0.324 |

0.589 |

0.486 |

1.000 |

||||||

|

MS4 |

0.434 |

0.433 |

0.429 |

0.387 |

0.517 |

0.433 |

0.509 |

0.532 |

0.489 |

0.234 |

0.205 |

0.239 |

0.281 |

0.281 |

0.497 |

0.506 |

0.495 |

1.000 |

|||||

|

MS5 |

0.505 |

0.550 |

0.564 |

0.454 |

0.618 |

0.569 |

0.538 |

0.633 |

0.563 |

0.295 |

0.290 |

0.307 |

0.334 |

0.331 |

0.656 |

0.491 |

0.569 |

0.543 |

1.000 |

||||

|

PEP1 |

0.455 |

0.462 |

0.455 |

0.398 |

0.542 |

0.506 |

0.523 |

0.585 |

0.506 |

0.257 |

0.205 |

0.282 |

0.323 |

0.344 |

0.460 |

0.441 |

0.418 |

0.385 |

0.478 |

1.000 |

|||

|

PEP2 |

0.382 |

0.403 |

0.374 |

0.355 |

0.456 |

0.359 |

0.423 |

0.466 |

0.428 |

0.225 |

0.171 |

0.221 |

0.263 |

0.242 |

0.354 |

0.326 |

0.375 |

0.342 |

0.356 |

0.554 |

1.000 |

||

|

PEP3 |

0.398 |

0.399 |

0.360 |

0.338 |

0.475 |

0.419 |

0.458 |

0.482 |

0.452 |

0.207 |

0.230 |

0.242 |

0.325 |

0.303 |

0.390 |

0.393 |

0.384 |

0.380 |

0.403 |

0.561 |

0.507 |

1.000 |

|

|

PEP4 |

0.447 |

0.445 |

0.452 |

0.406 |

0.493 |

0.437 |

0.416 |

0.492 |

0.473 |

0.252 |

0.205 |

0.263 |

0.260 |

0.298 |

0.420 |

0.407 |

0.414 |

0.334 |

0.377 |

0.536 |

0.434 |

0.386 |

1.000 |

ICS internal communication satisfaction; OI identification with the professional association; PI professional identification; MS membership satisfaction; PEP Perceived external prestige