Introduction

Converse famously argued that most individuals do not possess ideologically coherent and stable belief systems, which he suggested were primarily reserved for a small segment of the population with high political awareness (Converse, Reference Converse2006). In the seminal research, the lack of psychological constraints, which make a structured belief system, was often seen as a situation to rectify. Alignment of beliefs into coherent ideologies was seen as an improvement that facilitates orientation in politics and enhances the information environment, thereby helping people make choices more consistent with their preferences (Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010a; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Patel, Fahmy and Kaufman2014).

Recent research takes a more critical view of ideological alignment‐a condition in which person's many beliefs are highly interconnected. Instead of focusing on the ideology of the masses, many scholars concentrated on partisans and observed the troubling effects of tight ideological worldviews. Since then, ideological alignment has been shown to fuel political stereotyping and faulty generalizations (Agadullina & Lovakov, Reference Agadullina and Lovakov2018; Busby et al., Reference Busby, Howat, Rothschild and Shafranek2021) or to trap partisans in information silos (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Lawall and Tilley2024; Mutz, Reference Mutz2002). The most troubling consequence of ideological alignment, however, is the increasing animosity between different partisan camps, or affective polarization (Homola et al., Reference Homola, Rogowski, Sinclair, Torres, Tucker and Webster2023). Ideological alignment of partisans, studied only in the American settings so far, created challenges to reconcile the two comprehensive albeit radically opposing narratives (Abramowitz, Reference Abramowitz2022; Hare, Reference Hare2022; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010b).

Despite this extensive research, we are yet to understand whether such broad ideological rifts exist among European partisans, and how they are distributed across multiple opposing partisan camps. Given the seminal nature of this line of research, I address this gap at the broadest possible level and ask: Are all ideologically distinctive partisan camps equally ideologically aligned? Is the ideological contention between partisan camps asymmetrical, with one pole being more ideologically aligned than the other?

I combine several strains of the literature to propose a new thesis: That partisan camps on the ideological right are less constrained in their beliefs than those on the ideological left. This claim applies to various types of issues and extends to European party groups (such as factions in the European Parliament) as well as parties within individual national contexts. In this study, I perform a robust and broad test of the asymmetry hypothesis. Based on this newly outlined theoretical framework, I also draw an important implication for conflict between partisans. I argue that the extent of mutual disagreement depends on the ideological alignment within partisan camps at ideological extremes – the poles of ideological contention. I explain how the number of issues on which partisans disagree depends on the level of constraint within the partisan camp with the lowest belief constraint. Thus, when the partisan camp at one pole is more constrained in beliefs than the other, the extent of conflict depends on the alignment within the less ideologically coherent camp.

Employing a robust methodological framework that includes multiple operationalizations of key variables and extensive checks, I find evidence of ideological asymmetry in alignment across 15 European countries, seven European party families and 131 parties. The analysis uses multilevel regressions complemented by an innovative belief network estimation approach. The research incorporates data from the fourth and eighth waves of the European Social Survey (ESS; 2008, 2016), which include attitudes on additional economic issues, and utilizes the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015) and Manifesto Project data (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020) for ideological positions of partisan camps.

The paper is structured as follows. First, in the literature review, I summarize two research avenues suggesting asymmetry in ideological alignment and find a basis for additional hypotheses based on party ideological cues. The Methodological section introduces all variables of interest and measurement strategies. The Results section is divided into an analysis of the asymmetry hypothesis and an examination of additional propositions from prior research. In the test of the main hypothesis, I begin at the level of individual partisan camps (within countries), focusing on the ends of ideological scales, and then proceed at the level of European party families (across countries). Finally, I develop broader theoretical implications of these findings, discussing the differences in partisan disagreement under asymmetry. I conclude my findings for researchers and pundits, while also acknowledging the study's limitations.

Asymmetry in ideological alignment

Two main avenues of previous research suggest that European partisans on one side of the ideological spectrum may be more constrained in their beliefs: the research on belief cross‐pressures and the research on social underpinnings of parties which result in varying clarity of party ideologies. Both types of literature take a different perspective and propose different underlying mechanisms. They converge, however, on the prediction of asymmetry, with partisans on the left ideological pole being more constrained in their beliefs than those on the right, though the exact nature of this mechanism extends well beyond the scope of this study.

Cross‐pressured individuals and asymmetry in alignment

The first research avenue takes the perspective of an individual and examines what drives alignment with particular partisan camps. It argues that motivations differ between the ideological right and left, resulting in higher opinion heterogeneity within the right‐wing camp and, consequently, lower ideological alignment. This research suggests that many individuals are cross‐pressured across their various policy preferences and, when in doubt, favour a right‐leaning stance (Baldassarri & Goldberg, Reference Baldassarri and Goldberg2014; Gidron, Reference Gidron2022) either to manage uncertainty or to cope with dissonance created by conflicting policy preferences (Jost, Reference Jost2017). Additionally, partisans in different camps may vary in their awareness of a broader ideology, which connects this research to the second research avenue.

Parties tend to take consistent positions across economic and sociocultural issues, leaving some quadrants (such as the authoritarian left in Western Europe) unoccupied. However, there are voters who combine these beliefs more freely and are thus not well represented in such a party competition. These voters face a cross‐pressure between their economic and sociocultural beliefs (Federico et al., Reference Federico, Fisher and Deason2017; Kurella & Rosset, Reference Kurella and Rosset2017). Under such circumstances, as demonstrated by Gidron (Reference Gidron2022), they often favour views aligned with the ideological right, regardless of the specific dimension of concern (Baldassarri & Goldberg, Reference Baldassarri and Goldberg2014). This results in an extraordinarily heterogeneous partisan camp on the ideological right, as it includes individuals with beliefs that are often inconsistent with the ideology.

The same mechanism, however, can extend beyond the one particular scenario of cross‐pressures between economic and sociocultural stances. As shown in the United States, people often label themselves as conservative even if they do not actually hold conservative positions. Such attachments are largely symbolic, reflecting cultural or psychological motivations. Although these self‐identified conservatives appear to align with a particular party, they are often minimally ideologically aligned, holding many liberal beliefs as well (Ellis & Stimson, Reference Ellis and Stimson2012; Mason, Reference Mason2018). Psychological research also shows that when encountering ambivalence or uncertainty, individuals who tend to avoid uncertainty lean disproportionately towards the ideological right (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Napier, Thorisdottir, Gosling, Palfai and Ostafin2007). Similarly, conservatism is often evoked as a response to perceived threats that need to be managed. Overall, support for the ideological right appears to asymmetrically reflect psychological needs for order and certainty rather than intrinsic values (Jost, Reference Jost2017). As a result of these phenomena, the ideological right camp is likely more heterogeneous in beliefs and therefore less ideologically aligned.

Alternatively, some partisan camps may simply be more ideologically aware than others. This awareness involves not only belief in congruence between the partisan and the party but also knowledge of the party's ideological positions and justification of partisanship on ideological grounds (Lelkes & Sniderman, Reference Lelkes and Sniderman2016). Although Republicans are the more ideologically aware group in the United States, supporters of ideologically right parties in Europe appear to be less ideologically aware, particularly regarding broader ideological awareness. In an experiment, Kirkizh et al. (Reference Kirkizh, Froio and Stier2023) required supporters of various parties to choose between candidates proposing different preferred policies. While other partisans seemed to value multiple issues, radical right partisans focused primarily on a single preference central to their beliefs: restrictive immigration policies. In contrast, on the left ideological pole, preference intensity was more diffused, suggesting that a broader set of issues is central to these partisan camps.

Cleavages and party ideologies

The second research avenue focuses on the clarity of party ideology towards voters. Rather than individual‐level explanations, it considers studies showing that the ideology of parties on the ideological right may be narrower and more inconsistent, as right‐wing parties often compete for heterogeneous coalitions, particularly on economic issues. Consequently, such parties may rely on fewer key issues and reactive support when these issues become prominent. Other research, however, questions this asymmetry in reactive support and cross‐pressures in party programs, making it a somewhat weaker explanation for asymmetry.

Partisans are more likely to align their beliefs with the party line when comprehending party ideology. They also need to receive information about the party's position to internalize it. Reception is generally moderated by political awareness, enabling those attentive to politics to have a clearer understanding of what party ideology entails. Consequently, their beliefs are also more consistent (Jewitt & Goren, Reference Jewitt and Goren2016; Lupton et al., Reference Lupton, Myers and Thornton2015). A party with an ideology that clearly signals to partisans where the party stands provides an excellent basis for ideological alignment (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2001).

There is some evidence of significant asymmetry in party ideologies. In globalized societies (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2008), parties on the ideological left pole exhibit the most consistent ideology both within and across economic and sociocultural issues. Parties of the ‘New Left’ (radical left and green) adopted a strong set of libertarian socialist positions in addition to their pro‐welfare stances, as they rely mostly on a highly educated support base (Oesch & Rennwald, Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). In contrast, parties on the ideological right have to build a broad coalition from a working class that favours redistribution (Elchardus & Spruyt, Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2012) and small business owners who favour lower taxation (Oesch & Rennwald, Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). According to this view, both economic and sociocultural views attract voters to the radical left, while only a limited set of sociocultural policies draws interest to the radical right, who rely on the support of a heterogeneous coalition whose members differ in their economic interests. This inconsistency on the right may lead to lower ideological clarity and reduced alignment of partisans with the party on ideological grounds (Dassonneville et al., Reference Dassonneville, Fournier and Somer‐Topcu2023).

As a consequence, the emergence of broader ideologies is less frequently observed on the right. Several studies indicate that radical right parties give a strong emphasis on immigration, while other issues are de‐emphasized or intentionally left undefined (Rovny, Reference Rovny2013). This results in support that reflects the prominence of migration policies at the right ideological pole rather than a well‐defined ideology. The political context, including factors such as the prevailing welfare state and immigration patterns, plays a critical role in shaping the ideologies espoused by the radical right and their supporters (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2009; Bustikova, Reference Bustikova2014). Even for other parties, the success of the radical right primarily highlights the importance of immigration, allowing them to adopt more conservative immigration policies (Abou‐Chadi & Krause, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Krause2020) without necessarily fostering broad ideological disagreements or a comprehensive competing narrative (Izzo, Reference Izzo2023).

There is, however, some evidence that questions certain accounts of asymmetry based solely on party ideology. Contrary to the thesis of reactive support on the political right, Dennison and Kriesi (Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023) show that support for parties on the left also depends on the salience of specific issues, namely environmental issues and unemployment. Additionally, unlike partisans on the right, left‐wing supporters face a unique paradox. The open‐border policy can strain welfare spending, resulting in a ‘progressive's dilemma’. Such pressures may lead some camps to adopt a set of inconsistent policies, such as libertarianism combined with welfare chauvinism. However, this primarily affects left‐wing parties positioned closer to the ideological centre (Harris & Römer, Reference Harris and Römer2023) and not on the poles of ideological contention.

There appear to be at least two ways in which partisan camps on the ideological right pole may be somewhat less constrained than those on the ideological left pole. This asymmetry could affect economic and sociocultural issues or combinations thereof, even if the same partisan camps do not necessarily align across these different ideological scales. However, the reviewed literature suggests that there may be a deeper ideological asymmetry than previously assumed (ref. Gidron, Reference Gidron2022), extending within economic and sociocultural ideological domains and cutting across various issues.

Ideological asymmetry hypothesis: Ideological alignment is weaker among supporters of parties on the ideological right pole than the ideological left pole.

Other ideological characteristics of parties

There are many characteristics of a party's standing beyond whether it is closer to the left or right ideological pole that may shape ideological alignment within the partisan camp. If they affect ideological alignment, parties may exacerbate ideological conflict without actually changing their ideological positions. Since they offer an alternative way for partisan camps to differ in their levels of belief constraint independent from party ideology itself, these additional attributes of party ideology should also be studied.

In the first part, I focus on instances where the economic or sociocultural ideological standing of parties remains unclear – referred to as ideological position blurring. Through frequent shifts, ambiguity or by avoiding certain topics, parties may intentionally evade defending unpopular ideological positions (Koedam, Reference Koedam2021). In the second part, I examine instances where a party incorporates issues into its program that other parties have neglected – referred to as programmatic nicheness. Previous research suggests that niche parties (Meguid, Reference Meguid2023), unlike mainstream parties, may be more effective at shaping the opinions of their supporters (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Leiter2012). Although the empirical evidence in this context remains limited, it is a theoretically compelling argument that highlights the importance of issue emphasis among competing parties relative to one another.

These strategies may attenuate the perceived extremity of a party's ideological positions when it is electorally advantageous. However, as a side effect, they may also alter ideological alignment within partisan camps. Such an effect could be anticipated based on the same mechanism of cue‐taking outlined above (Lupu, Reference Lupu2013).

Ideological position blurring

When competing on issues, parties often obscure their stances on those issues that do not yield electoral benefits and could be costly to alter (Koedam, Reference Koedam2022; Rovny & Edwards, Reference Rovny and Edwards2012; Tavits, Reference Tavits2007). This could be done in multiple ways. They may avoid discussing these issues, maintain ambiguous positions or frequently change their stances, thereby confusing the public (Koedam, Reference Koedam2021). Conversely, such a strategy can lead to a loss of brand clarity and, consequently, diminish party identification (Dassonneville et al., Reference Dassonneville, Fournier and Somer‐Topcu2023; Lupu, Reference Lupu2013).Footnote 1 Although it may often fail, it is possible to identify when blurring succeeds – it is when even experts, who listen to speeches, read statements, and follow the news, cannot reliably place a party on an ideological scale. Thus, blurring is often captured by measuring uncertainty in assessments of a party's ideological positions.

In practice, uncertainty regarding a party's ideological positions may not originate from a conscious strategy. It can also stem from other factors, such as internal inconsistencies within the party. Party leaders, members of parliament or regional representatives may provide conflicting views on issues, thereby adding to the confusion. Nevertheless, these involuntary situations of a divided party base often pressure party elites into adopting a conscious strategy of ambiguity when they are expected to formulate comprehensive party ideologies (Han, Reference Han2022).

Position blurring hypothesis: Ideological alignment is stronger among supporters of parties with clearer ideological positions.

Programmatic nicheness

Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Ezrow and Leiter2012) document that the alignment between policy views and partisan identity functions more effectively for certain parties than for others. They show that support bases of green, communist, or radical right parties tend to align more closely with new ideological positions when these parties undergo position shifts. They propose that this phenomenon is partly attributable to the ideological extremity of these parties. More importantly, they also argue that the niche programmatic appeals of these parties attract policy‐focused supporters, which facilitates this alignment.

The latter argument presents an alternative perspective on the ideological space. It suggests that not only does a party's own ideological position matter, but its programmatic focus relative to the programmatic focus of other parties within the party system may also influence the ideological alignment of partisans. For the purposes of this argument, nicheness can be defined as the programmatic integration of a set of issues neglected by other parties (Bischof, Reference Bischof2017; Meyer & Miller, Reference Meyer and Miller2015).Footnote 2 Being a niche party implies the programmatic distinctiveness but does not necessarily entail extreme positions or overly narrow party programs, as niche parties may also integrate mainstream issues into their ideological frameworks.

Even though the evidence for the potential effect of nicheness on ideological alignment is largely anecdotal and weaker than that supporting previous hypotheses, it represents an alternative perspective that warrants empirical testing. If relative programmatic focus does indeed matter, it would open new avenues for understanding the programmatic influences on ideological alignment. For instance, parties might de‐emphasize one ideological dimension compared to other parties to foster alignment on another dimension‐shifting ideological alignment through targeting issues with particularly high issue yield (Sio & Weber, Reference Sio and Weber2014), that are outside of the main ideological contention.

Programmatic nicheness hypothesis: Ideological alignment is stronger among supporters of parties that are programmatically distinct from the mainstream (niche parties).

Analysing belief constraint among partisans

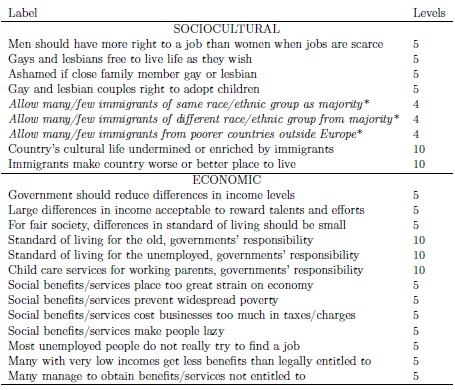

I analyse the attitudes of partisans and how well these attitudes align with the ideological pole closest to their party's position. For the cross‐sectional analysis, I require survey data that include as many cultural and economic attitude items as possible, along with questions on partisan identity. I use the fourth and eighth rounds of the ESS (2008 and 2016), which include an additional module with more economic attitudes than the core survey. To measure ideological alignment, I use positions on thirteen economic issues (redistribution, social benefits, market regulation) and seven cultural issues (gender, morality, immigration). The attitude scales were transformed so that higher values represent more conservative/right‐wing positions on cultural and economic issues (for more descriptive statistics on alignment by attitude, see Online Supplement A2). All attitudes used are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Attitudes used for ideological alignment.

Note:* The three immigration questions are recoded using a composite scale due to the low number of levels, alpha = 0.88 indicates high reliability of this scale

Data were gathered from 15 European democracies, incorporating at least one country from each European region. I selected all European countries for which data was available and included all parties that could be matched with data on party positions. I acknowledge some limitations of my design; for instance, whether certain issues are classified as economic or sociocultural can be contested. Therefore, I reproduce the main analysis by selecting only the items that load reliably onto the same (economic or sociocultural) factor (see Online Supplement B1). The results and conclusions do not change substantially with this robustness testing.

Due to the focus on partisan conflict, the analysis is limited to respondents who identify with a political party. I, therefore, excluded moderates and unaffiliated individuals from the survey, leaving a sample of 23,586 respondents (of whom 12,048 are from the eighth wave) across 131 parties. On average, partisans represent 43 per cent of the sample within each respective country. However, there are substantial differences across parties, which are summarized in the second part of Online Supplement A4. I included all parties that could be matched with the data on party positions. Despite this limitation, the overwhelming majority of parties are included. The parties encompassed in the analysis represent, on average, 90 per cent of the vote share within their respective countries (or 94 per cent of the seat share in parliaments; see Online Supplement A4 for country‐specific results).

The ideological position of the respondent's party is estimated using the CHES, Footnote 3 (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015), which provides expert assessments for party positions on both ideological dimensions of interest (economic left‐right scale and the cultural scale ranging from Green, Alternative, Libertarianism (GAL) to Traditionalism, Authoritarianism and Nationalism (TAN), commonly referred to as the GAL‐TAN scale). Positions on a 10‐point economic ideological scale are used to measure the economic beliefs of partisans, and positions on a 10‐point sociocultural (GAL‐TAN) scale are used for sociocultural beliefs. The sample of analysed parties is highly diversified across both ideological dimensions and in the combination of positions across these two dimensions (see Online Supplement A1). The combination of CHES data with individual‐level surveys has a distinctive advantage since CHES correlates most strongly with how people perceive the positions of individual parties (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow, Gordon, Liu and Phillips2019; Dassonneville et al., Reference Dassonneville, Fournier and Somer‐Topcu2023). Finally, for the programmatic nicheness variable, which reflects issue emphasis in party programs, I use data from the Manifesto Project (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020).

Dependent variable: Ideological alignment among partisans

Ideological alignment in this paper is defined as a configuration of political views that is broadly consistent with the ideological orientation of a preferred party. This conceptualization is in line with previous literature on belief constraint and partisan allegiances (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Tucker and Duell2013; Converse, Reference Converse2006; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010a; Slothuus & de Vreese, Reference Slothuus and Vreese2010). The chosen approach does not consider the source of alignment, which could stem either from individuals adhering to party elites or from shifts in issue salience that lead partisans to realign their allegiances (Dennison & Kriesi, Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010b; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Regardless of the causal direction, the sorting process may involve partisans adopting party ideology or altering their identity to resolve dissonance between personal and party ideologies.

There are at least two approaches to studying ideological alignment. One focuses on the internal coherence of partisan groups, while the other examines the ideological organization of individual beliefs. Both perspectives are socially significant and align with theoretical expectations. The coherence of partisan groups facilitates attitude generalization and, consequently, stereotyping of other partisan camps (Agadullina & Lovakov, Reference Agadullina and Lovakov2018; Busby et al., Reference Busby, Howat, Rothschild and Shafranek2021), ultimately contributing to affective polarization. A lack of diversity within partisan groups can have other detrimental effects, potentially fostering echo chambers where beliefs become radicalized (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Lawall and Tilley2024; Mutz, Reference Mutz2002). However, ideological thinking at the individual level is equally concerning. Current research indicates that partisan animosity is rooted in substantive disagreements (Dias & Lelkes, Reference Dias and Lelkes2022; Orr & Huber, Reference Orr and Huber2020). Ideological conflict represents a significant discrepancy between comprehensive narratives, leading to extended troubling conflicts (Hare, Reference Hare2022; Layman & Carsey, Reference Layman and Carsey2002).

Each conceptualization requires a distinct operationalization of the dependent variable. I propose two different measurements to capture both types of ideological alignment, demonstrating that ideological asymmetry extends to both. The degree of ideological alignment at the individual level could be measured by the number of attitudes aligned with partisan identity (Baldassarri & Gelman, Reference Baldassarri and Gelman2008; Bougher, Reference Bougher2017), emphasizing the extent of alignment and its reach across various political attitudes. At the group level, alignment addresses the ideological organization of beliefs as a network modelled for a group of party supporters. Ideological interconnectedness within group beliefs is a measure that aligns with early descriptions of belief constraint as the ability to predict other beliefs when knowing at least one belief (Converse, Reference Converse2006; Jewitt & Goren, Reference Jewitt and Goren2016). This approach focuses on the strength of existing associations as a means to analyse the internal coherence of partisan camps. Thus, the dependent variable is measured as (a) the number of aligned attitudes and (b) the interconnectedness of belief systems. The first is used in all the analyses, the second could be only used with a categorical predictor – party families.

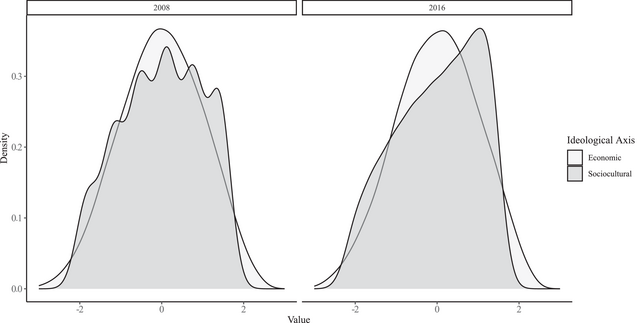

… as the number of aligned attitudes

In the first operationalization of the dependent variable, I pursue a measurement that does not incorporate the extremity of attitudes or parties' positions through a score of issue alignment (Bougher, Reference Bougher2017). The beliefs are transformed depending on whether they fall on either the progressive (left‐wing) or conservative part of the belief continuum (e.g., they favour or oppose an extensive welfare state). The score of alignment tells us on how many issues a partisan is aligned with their party's ideological position (on either economic or sociocultural axis) minus the number of issues on which the partisan has a diverging opinion. Footnote 4 When the respondent did not provide any answer or said she did not know, the response was coded as 0. More information on the computation of the ideological alignment is in Online Supplement A2. Because the number of economic (N = 15) and sociocultural (N = 7) attitudes differ, I standardize the dependent variable in the models. The alignment distribution on both ideological dimensions is shown below (see Figure 1). Although the ideological alignment on sociocultural attitudes is, on average, higher and the distribution positively skewed, there is still significant variance. I model ideological alignment on each ideological dimension through three‐level varying intercept models (with parties as a second‐level variable and countries as a third‐level variable).

Figure 1. Distribution of ideological alignment on economic and sociocultural axes.

Note: Kernel density plots with a two kernel bandwidth, N = 23,586 respondents, who indicated they feel close to a particular party, in 15 countries.

… as the interconnectedness of beliefs

The previous measurement may obscure important information about the nature of ideological alignment by taking individual beliefs as independent items, which is not a realistic assumption. Attitudes are often organized in structures where individual elements interact dynamically in a sense that change in one attitude influences the others (Turner‐Zwinkels & Brandt, Reference Turner‐Zwinkels and Brandt2022). Therefore, I cannot entirely omit the relationships between individual attitudes, especially when partisans could be expected to organize beliefs differently depending on their preferred party or country's political context. Hence, the second operationalization emphasizes the strength of connections among attitudes within partisan subpopulations. Given the multiple levels of bootstrapping involved (see below), it is too computationally demanding to model belief networks for every partisan group and make comparisons across all such groups. Therefore, I use party families, which are clusters of parties with similar ideologies, as subpopulations. I rely on expert assessments from the CHES dataset to categorize individual parties into families. I then pool together the supporters of parties within each family for analysis. My focus is on parties whose ideologies can be positioned on both ideological scales, excluding families of regionalist, confessional and unclassifiable parties.

A conception of belief consistency influences the operationalization of ideological alignment by correlating individual attitudes. Belief consistency (or constraint) is defined as the success we would have by knowing one individual's attitude in predicting other individuals' attitudes (Converse, Reference Converse2006). As I have limited the analysis to those identifying with some political party, consistency is also a measure of ideological alignment. More attitudes can be predicted based on partisan identity if organized in a system with higher belief consistency. For this purpose, I employ a belief network system approach that examines the interrelationships of attitudes and compares these systems (Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Sibley and Osborne2019). In the analysis, I compute partial correlations (indicate unique pairwise associations) between all pairs of attitudes for each subpopulation of interest. Because there are 20 different attitudes that could be paired, there could be up to 190 connections (![]() ) within each system. In such belief system estimation, it is necessary to differentiate between meaningful associations and those that are not statistically different from zero using some measurement of uncertainty. Consistently with previous research, I use partial Spearman correlations and the extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC) glasso method (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Hastie and Tibshirani2008; Foygel & Drton, Reference Foygel and Drton2010) to identify significant connections. Footnote 5 The LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) method identifies substantial connections in the network. The EBIC works as a tuning parameter to determine how much regularization is needed given the model selection criterion (considering sample size, etc.). A combination of both of these approaches facilitates the identification of a best‐fitting network, where only significant correlations are considered (Epskamp et al., Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried2018).

) within each system. In such belief system estimation, it is necessary to differentiate between meaningful associations and those that are not statistically different from zero using some measurement of uncertainty. Consistently with previous research, I use partial Spearman correlations and the extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC) glasso method (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Hastie and Tibshirani2008; Foygel & Drton, Reference Foygel and Drton2010) to identify significant connections. Footnote 5 The LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) method identifies substantial connections in the network. The EBIC works as a tuning parameter to determine how much regularization is needed given the model selection criterion (considering sample size, etc.). A combination of both of these approaches facilitates the identification of a best‐fitting network, where only significant correlations are considered (Epskamp et al., Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried2018).

The belief network is estimated for a subpopulation defined by party families. In every network, I describe the number of statistically significant connections. More connections indicate that we can predict more attitudes in such a network. However, additional tests are required to compare belief networks because techniques to identify significant edges are sensitive to sample size (Epskamp et al., Reference Epskamp, Borsboom and Fried2018). Luckily, such bootstrapping‐based methods are available. Based on 1000 permutations, I perform global expected influence invariance tests for pairs of network systems at stake given the tested hypothesis. Footnote 6 This statistical test provides a reliable examination of differences in belief consistency and measure of uncertainty in comparing belief network systems.

This gives me the second outcome variable. The global expected influence (also GEI) is a sum of all significant partial correlations Footnote 7 in the network and another measure of belief consistency. To compute its score, all positive correlations are summed and then all negative correlations are subtracted from that value. Insignificant correlations do not contribute to this score because they signify the disconnection and independence of each belief, indicating a lack of ideological alignment. Negative correlations also represent a lack of meaningful alignment, as they reflect connections that are contrary to ideological alignment (i.e., some conservative beliefs being linked to liberal beliefs). These connections do not contribute to the deepening of partisan conflict; instead, they would mean partial agreement with the opposing camp. A significantly higher global expected influence indicates higher belief consistency for the subgroup.

Levels of analysis

In the empirical sections, I start with the study of ideological alignment within countries. This is, however, not the only level of analysis. Partisans in all the studied countries (except the United Kingdom) are also part of the European Union, and their parties participate in cross‐national politics, including in the European Parliament and other forums. Therefore, in addition to examining alignment at the national level, I also incorporate a cross‐European perspective, focusing on differences among programmatically similar groups of parties. This level ensures that what is found for average countries also extends to European politics as a whole.

Within countries: Individual partisan camps

The primary arena for political contention is undoubtedly at the national level. Accordingly, I examine and test the asymmetry hypothesis for average partisans within an average country, focusing on their ideological alignment. Since the independent variable – parties' ideological placement – is measured on a continuous scale, I limit the analysis to the first operationalization of the dependent variable. To measure the ideology of partisan camps, I use expert assessments of party positions from the CHES dataset, specifically their placement on the left‐right axis for economic issues and the GAL‐TAN axis for sociocultural issues.

On this level, I also test the other two hypotheses. Consistently with previous studies, position blurring is operationalized as a standard deviation of expert assessments of party ideological positions (Rohrschneider & Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2012). The more perceptions of party ideology differ, the greater the successful blurring of its ideological position. Although the author warns about some limitations of this way of measuring blurring, it is highly correlated with alternative measures that were proposed (Han, Reference Han2022).

I employ a continuous measurement of ideological nicheness based on a minimal definition of the concept (Meyer & Miller, Reference Meyer and Miller2015), which is programmatic distinctiveness of the party within the party system. I prefer this over alternative understandings (Bischof, Reference Bischof2017) because it is not as strongly predicted by ideological differences across party families and, therefore, is empirically more distinct from the inquiry into ideological content. The distribution of continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables is summarized in Table 2. There is a substantial variance in all of these variables. In the case of party families, where I use only 2016 data for belief network estimation, I also add descriptive statistics for just one of the survey waves (in parentheses). As I elaborate in Online Supplement A1, the predictors are only weakly correlated across the sociocultural and economic dimensions.

Table 2. Predictors: Distributions and frequencies.

Note: The Regionalist, Confessional, and No Family party families are excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the shares do not add up to 100 per cent. The descriptives for the 2016 data, which are used for belief network modelling, are provided in parentheses.

Cross‐European: Party families

Second, I focus on the cross‐European level, grouping parties into families sharing distinct programmatic characteristics. For that purpose, I use CHES‐designated party families, which triangulate several sources, including previous classifications, party's self‐identification and membership in factions of the European Parliament (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Leiter2012; Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015). Party families are compared based on their order on a single ideological dimension ranging from the far right to the new left, as often construed by voters (Zollinger, Reference Zollinger2024). Primarily, I distinguish between left‐wing party families (radical left, green and socialist) and other party families that are ideologically defined (excluding regionalist or confessional parties).

Recent research have revealed that some party families are composed of more ideologically similar parties than others (de la Cerda & Gunderson, Reference Cerda and Gunderson2024). The same study, however, suggests higher heterogeneity within party families on the left, whose supporters tended to be more ideologically aligned in the previous analysis. This makes using party families a more conservative test of the asymmetry hypothesis.

Nevertheless, to ensure the robustness of the asymmetry hypothesis, I also focus on extreme poles of economic and ideological continua. Therefore, the second approach eschews classification into party families in favour of utilizing poles of ideological contention.

Results

The results are presented beginning with the asymmetry hypothesis, followed by the blurring hypothesis and the programmatic nicheness hypothesis. In testing the asymmetry hypothesis, I begin with the poles of ideological contention and specific party positions within countries and then proceed to the broader level of party families, analysing belief networks and alignment across issues. In all but the cross‐country section, I use partisan issue alignment as the outcome variable. This is because all predictors, except for party families, are continuous, and belief networks cannot be efficiently estimated for continuous scales.

Asymmetry in ideological alignment within countries

First, I study ideological alignment within countries. For this analysis, I am using the two‐dimensional approach, distinguishing between economic and sociocultural ideologies. Given that certain partisan groups may exhibit higher levels of knowledge or sophistication, I incorporate a set of political and demographic controls, including political interest, education, and gender. I utilize data from both points in time (2008 and 2016) to also examine changes over time previously described. To test for asymmetry, I include quadratic polynomial terms for the ideological positions of political parties. For comparability, both dependent variables were standardized across models.

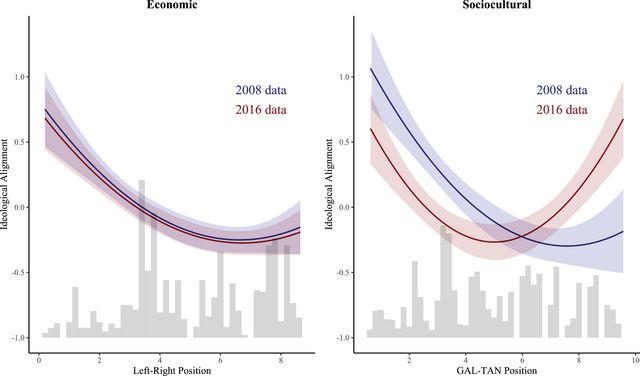

Figure 2. Ideological asymmetry in ideological alignment.

Note: Models were fitted with quadratic polynomials for ideological positions and interaction for the time variable. I used multi‐level models with a structure of three levels: countries, parties and partisans. Models also include varying slopes for the time variable.

Focusing on ideological alignment on economic issues, there is a substantial ideological asymmetry in both survey waves spanning over eight years. The difference (B = −0.32, SE = 0.07) when moving by one point on a 10‐point ideological scale is meaningful and corresponds to one‐and‐a‐half attitudes that are disconnected from an ideology. The spline is close to linear, although the quadratic term effect is statistically significant (B = 0.024, SE = 0.008). No effect is significantly different between the two survey waves.

Ideological alignment on sociocultural issues in 2008 follows the same pattern, with the ideological asymmetry being even more substantial when considering both dependent variables in their standardized forms ![]() . The average ideological alignment to the right of the centre

. The average ideological alignment to the right of the centre ![]() or at a centre‐right position

or at a centre‐right position ![]() changes slightly, with supporters of the extreme right aligning as closely as their centrist counterparts. In contrast, the scenario significantly shifts with the more recent data from 2016, which indicates high ideological alignment at both ideological extremes. The first notable change is a somewhat lesser alignment between the two waves on the extreme left, and though this difference

changes slightly, with supporters of the extreme right aligning as closely as their centrist counterparts. In contrast, the scenario significantly shifts with the more recent data from 2016, which indicates high ideological alignment at both ideological extremes. The first notable change is a somewhat lesser alignment between the two waves on the extreme left, and though this difference ![]() is noteworthy, it is not statistically significant due to the heterogeneity across parties and countries. Most importantly, the 2016 data reveal a shape reminiscent of a parabolic spline, indicating a bimodal distribution in alignment. The predicted ideological alignment at the lower end of the GAL‐TAN scale, specifically at position 0.6, is 0.6, which is comparable to the prediction at the upper end of the same scale, where it is 0.7 at position 9.6. The observed difference is suggestive of ideological realignment on sociocultural issues within the right‐wing spectrum of parties between 2008 and 2016.

is noteworthy, it is not statistically significant due to the heterogeneity across parties and countries. Most importantly, the 2016 data reveal a shape reminiscent of a parabolic spline, indicating a bimodal distribution in alignment. The predicted ideological alignment at the lower end of the GAL‐TAN scale, specifically at position 0.6, is 0.6, which is comparable to the prediction at the upper end of the same scale, where it is 0.7 at position 9.6. The observed difference is suggestive of ideological realignment on sociocultural issues within the right‐wing spectrum of parties between 2008 and 2016.

The observed changes in the sociocultural dimension suggest a diminishing asymmetry on these issues. Given the limitations of the data, it is, however, impossible to conclude, if this represents a longer trend. The found difference is consistent with two possible explanations. Either supporters of existing conservative and radical right parties became more aligned in their beliefs with conservative ideology, or the party systems changed with a rise of new challenger parties, such as radical right parties, newly occupying the pole on the utmost conservative ideological right (Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016; Rovny & Edwards, Reference Rovny and Edwards2012).

Regardless of a specific mechanism in place, this change means the emergence of a well‐defined conservative ideology on the right‐wing extreme between 2008 and 2016. Although this change is only limited to sociocultural views on gender, morality or immigration and does not extend to economic matters, it might be sufficient for a more comprehensive narrative essential for broader ideological conflicts in the future (Izzo et al., Reference Izzo, Martin and Callander2023).

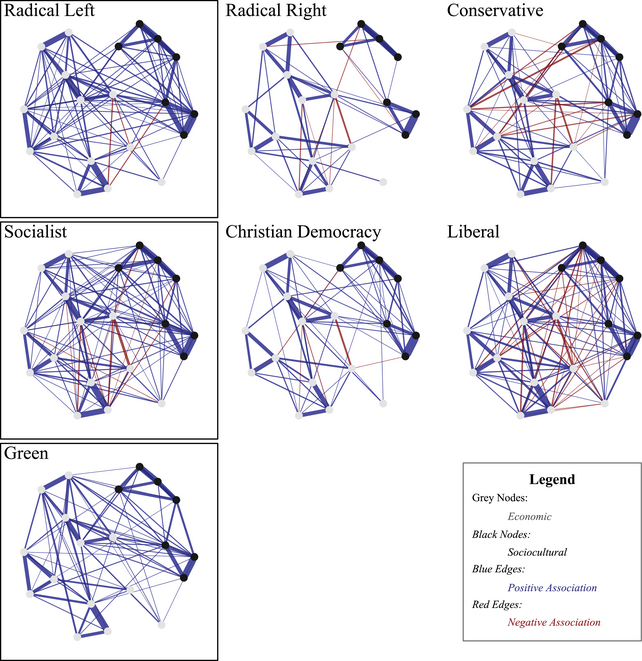

Asymmetry in ideological alignment across countries

Second, taking a more holistic approach, I estimate and measure belief network systems for partisans based on families of parties of their choice with the most recent data (2016). I then compare the properties of these networks across seven partisan subpopulations corresponding to supporters of seven types of parties (from radical left to radical right). Subsequently, I compute the global expected influence – by summarizing all associations within the belief system – and employ a bootstrapping technique to test the significance of these differences. This comparison is always done for a pair of party families. Because of my interest in left‐wing families, I use the three left‐wing party families as baseline categories, and I compare them to every other family (labelled as a reference family). The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Belief network comparisons: Interconnectedness of beliefs for party families

Note: Global Expected Influence (GEI) is a measurement of the interconnectedness of belief networks. It is measured as the sum of all edge weights (partial correlations). The differences between the interconnectedness of individual networks were bootstrapped with 1000 iterations for significance testing. Differences significant on conventional levels are highlighted in bold. More information is in the Methods section.

First, this method shows strong evidence of ideological asymmetry. Beliefs of supporters of left‐wing party families are much more ideologically aligned and consistent than supporters of other parties. The interconnectedness of beliefs (measured as GEI) among left‐wing party families is about 10 to 47 per cent higher than in the latter (depending on the specific party family). The greatest difference (47 per cent) is between the radical left and the radical right pole, as we would expect based on their positions along the ideological continuum. Moreover, with just one exception, all of these differences across networks are statistically significant and follow the same trend. The closer the party camp is to the ideological right pole, the lower is its ideological alignment.

Belief network approaches provide more insights than a single statistic regarding network interconnectedness. The global expected influence effectively summarizes networks characterized by both positive and negative associations. Nevertheless, we might also ask how many belief associations are non‐zero in a particular system or how much interconnectedness was subtracted due to the presence of negative ties. Consequently, I visualize belief networks for all partisan subpopulations in Figure 3. These networks were regularized, ensuring that identical nodes were plotted in the same positions. I focus exclusively on meaningful connections; therefore, ties that were not statistically significant are omitted. Within these networks, nodes represent distinct political issues. The nodes visualized in lighter grey are economic issues, while those in black are sociocultural issues. The edges connecting the nodes provide two kinds of information: the width of an edge reflects the strength of the association, and the blue colour denotes positive edges (indicating more alignment), whereas the red colour represents negative associations (indicating less ideological alignment). In Online Supplement C1, you can find all of these networks with annotated nodes to explore any connection in detail.

Figure 3. Belief network systems visualizations.

The belief networks for those who support left‐wing progressive parties (highlighted in black frames) exhibit some differences, even visually. First, they display a larger number of significant connections, appearing more dense or interconnected. Each of the three belief networks has between 41 per cent and 61 per cent significant connections (more than 78 out of 190 possible edges). In contrast, the three right‐wing belief networks only have between 27 per cent and 45 per cent of significant edges. The cases of the radical right and the Christian democratic party families are exceptional, featuring a very low number of meaningful associations. This low number of associations could be attributed to a small sample size; however, the number of partisans in both groups, ![]() and

and ![]() , is higher than that for two left‐wing party families,

, is higher than that for two left‐wing party families, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Additionally, in cases such as conservative parties, many of these connections are negative – and therefore, inconsistent with ideological alignment (20 per cent of all significant ties). The Liberal party family represents a unique case; its belief network includes 110 significant ties, of which 28 per cent are negative. On the left, however, very few of the associations are negative. Partisan camps on the left are constrained in their progressive beliefs.

Alignment of economic and sociocultural ideologies

Using the second outcome variable, the number of aligned attitudes, I aim to replicate the findings of differences across party families. Rather than focusing on all issues, I now differentiate between economic and social issue domains and study alignment for these two types of issues separately.

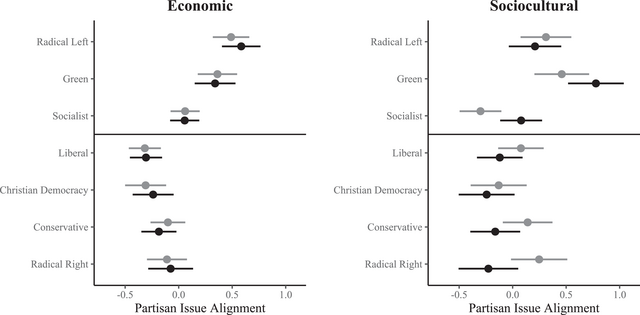

This analysis again reveals evidence of ideological asymmetry (see Figure 4). This asymmetry persists across two points in time, eight years apart. First, let us focus on the predicted values of ideological alignment on economic issues. When measured by the number of ideologically aligned beliefs, left‐wing party families exhibit greater alignment among their supporters. For instance, supporters of the Green parties (B = 0.36, SE = 0.07 in 2016; B = 0.34, SE = 0.14 in 2008) and the radical left parties (B = 0.49, SE = 0.07 in 2016; B = 0.58, SE = 0.13 in 2008) show a significantly higher alignment on economic issues than average. Specifically, Green party supporters exhibit two additional ideologically aligned economic attitudes above average, while radical left supporters show about two and a half. In contrast, supporters of all right‐wing and centrist parties tend to exhibit about one ideologically disconnected attitude below average.

Figure 4. Party family differences in predicted numbers of aligned issues.

Note: Predictions based on 2008 data are visualized in black, and predictions based on 2016 data are in grey. The dependent variables were standardized.

On the sociocultural dimension, although asymmetry is still present, it could only be confirmed in 2008. On the left, partisans remain more aligned on sociocultural issues, with radical left supporters showing an alignment of approximately one additional attitude (B = 0.21, SE = 0.18) and Green supporters showing alignment on approximately three more attitudes (B = 0.78, SE = 0.19) compared to the average. The pattern changes in 2016, with a significant dealignment among Green parties (a change of −0.32 SDs, or more than one attitude aligned) and ideological realignment on the right. Supporters of conservative parties have, on average, more than one additional attitude aligned (a change of 0.3 SDs), and a similar trend is observed in the radical right camp (a change of 0.25 SDs). The following analysis, which employs party positions, could further elucidate this change.

Limited effects of other ideological characteristics

Ideological position blurring

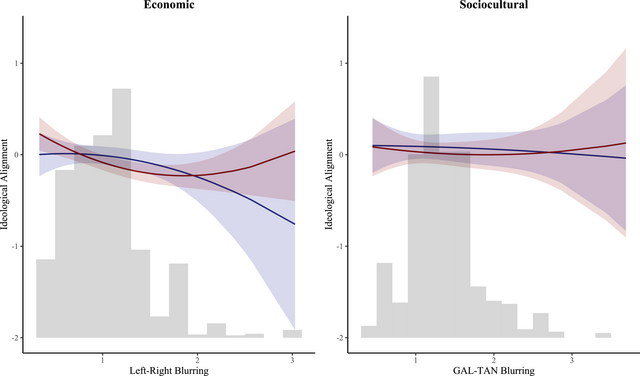

One of the findings concerning ideological asymmetry in party positions suggests that radical right parties often strategically conceal their stances on economic issues (Rovny, Reference Rovny2013). Consequently, it is plausible that right‐wing parties deliberately obscure their, often less popular, positions (Izzo, Reference Izzo2023) to evade electoral repercussions. In contrast to positions themselves, the hypothesized effect of ideological position blurring links ideological alignment to an intentional party strategy to obscure their ideological stance. This operationalization employs the standard deviations in coder responses. The analysis employs the same dependent variable (partisan ideological alignment) and the same modelling strategy as in the previous case. As shown in Figure 5, there is only limited evidence supporting this hypothesis.

Figure 5. Marginal effects of position blurring.

Note: Multilevel models were fitted with quadratic polynomials for blurring and interaction for the time variable. Survey data from 2008 are in blue and the data from 2016 are in red.

Position blurring significantly and negatively affects ideological alignment on the economic dimension (B = −1.1, SE = 0.33). However, this effect is confined to more recent data (no significant effects were detected in 2008), and the effect is not linear (![]() = 0.28, SE = 0.11). While some degree of position blurring decreases ideological alignment, there is no evidence that it affects ideology at its extremes. Nevertheless, the detected effect is statistically significant, and the effect magnitude is non‐trivial.

= 0.28, SE = 0.11). While some degree of position blurring decreases ideological alignment, there is no evidence that it affects ideology at its extremes. Nevertheless, the detected effect is statistically significant, and the effect magnitude is non‐trivial.

Conversely, no effect of position blurring was detected on sociocultural issues in either 2008 (B = −0.1, SE = 0.4) or 2016 (B = −0.45, SE = 0.42). The residual variations across countries, parties and between waves are considerable. However, despite this uncertainty, the predicted differences remain quite small, particularly when compared to the magnitude of ideological asymmetry discussed in the previous section.

The average intercept is close to zero across these models, indicating that the predicted alignment for supporters of a party that does not engage in blurring its economic ideology (such as the People's Party in Spain) is about average. To find a comparable party with only one additional ideologically disconnected belief (out of 13), it would typically be necessary to look at a party with 1.3 standard deviations in expert assessments of its economic ideology. Often, such parties have little economic focus. For example, single‐issue parties like the Scottish National Party or the Pirate Party in Germany engage in this level of economic position blurring. Thus, while the significance of position blurring on economic issues is confirmed, it is limited.

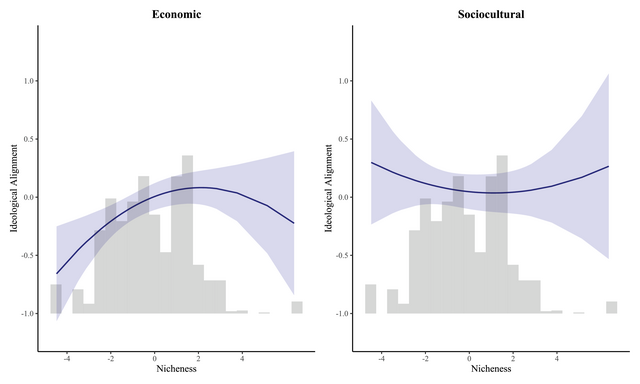

Programmatic nicheness

To test the nicheness hypothesis, I combined data from the CHES and the Manifesto Project, which resulted in a reduction of the dataset (2280 observations were dropped). The reduction primarily affected non‐parliamentary parties with few respondents; specifically, 26 per cent of the parties (28 parties in total) were dropped, but these represent only 19 per cent of the observations. I focus only on data from the 2016 round of surveys since the coding instructions by the Manifesto Project changed in 2010. The operationalization of nicheness I employ quantifies how a party's policy profile deviates from the positions of other parties along the same policy dimension (Meyer & Miller, Reference Meyer and Miller2015), reflecting the extent to which the party emphasizes non‐mainstream issues. As a result, these parties appear more principled and policy‐focused.

However, the data do not support the presumed influence of programmatic nicheness as depicted in Figure 6. The analysis reveals a statistically significant (B = 0.7, SE = 0.03) yet non‐linear effect of nicheness on economic ideological alignment. Nevertheless, deviations from the mainstream that are higher than average tend to be detrimental rather than supportive of alignment. While these findings do not conclusively affirm the impact of nicheness on ideological alignment regarding economic policies, they align with the general elite cues paradigm. Specifically, when parties are minimally distinctive ideologically (such as the Center Party in Finland, the Polish Democratic Left Alliance or the Flemish Christian Democracy), their positions become more ambiguous, potentially leading to reduced alignment among their supporters. In contrast, on the sociocultural issue domain, there is no significant effect of nicheness (B = −0.02, SE = 0.04), possibly supporting the notion that the sociocultural dimension is more principled and clearer (Tavits, Reference Tavits2007). Overall, these results suggest that the role of nicheness is modest, primarily affecting the least distinctive parties and ideological alignment within the economic ideological dimension.

Figure 6. Marginal effects of ideological nicheness.

Note: I matched the ESS data with the Manifesto project data for this model. The descriptive statistics on dropped cases can be found in the Supporting Information. Averages for radical right parties are highlighted in the plot. Only the survey data from 2016 were used and depicted in blue.

Conclusions

In an extension of previous findings, I reaffirm the asymmetry in ideological alignment between the ideological right and left. This asymmetry could be found when considering European politics as a whole as well as the politics of individual countries. The two dependent variables also ensure that this holds true for the ideological alignment of individuals as well as partisan groups (in the context of cross‐country analysis). The only exception to this is the symmetry in the ideological alignment of partisans observed in more recent data (2016) on the sociocultural dimension and corresponding issues. In that area, ideological alignment became symmetric between the two poles. Furthermore, these results also suggest the limited relevance of other ideological factors, such as nicheness or ideological position blurring, that parties may use in competition. The variables matter only marginally (i.e., at extreme levels of nicheness or blurring) and only on economic issues. Overall, these findings indicate a persisting asymmetry but also reveal intriguing differences between economic and sociocultural ideologies.

This finding is derived at the macro level and with limited consideration of individual contexts. Yet, it carries important implications for several areas of research interest. In particular, in the next section, I discuss an important theoretical implication for the nature of partisan disagreement. This significance lies in the fact that only the less constrained ideological side sets the extent of such substantive conflict – a point on which I elaborate in more detail. Given the asymmetry across the economic ideological dimension, the deepening of conflict between partisans depends more on the increase in constraint on the right than on the left.

Implications of asymmetry for partisan disagreement

Disagreement among partisans on issues is an important source of division (Algara & Zur, Reference Algara and Zur2023; Orr et al., Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023), which often hinges on an assumption, that partisan camps are internally ideologically aligned (Homola et al., Reference Homola, Rogowski, Sinclair, Torres, Tucker and Webster2023). Using a simple theoretical justification, I outline how asymmetry in ideological alignment between opposing poles changes such disagreement.

Ideological contention can be imagined as one or more continua with two opposite poles. For partisan disagreement, these poles correspond to divergent partisan groups, along with their opposing political views and beliefs. Both stand strongly on the opposite sides but might differ in ideological alignment. Among supporters of some parties, there is broad consensus on many issues, while in other camps, partisan identity poorly reflects the beliefs of its constituents (Dassonneville et al., Reference Dassonneville, Fournier and Somer‐Topcu2023; Gidron, Reference Gidron2022). For substantial partisan disagreement to occur, it is necessary that partisan camps on poles of ideological contention are sufficiently constrained in their beliefs (DiMaggio et al., Reference DiMaggio, Evans and Bryson1996). First, if beliefs of individuals do not align well within a particular partisan camp, it may appear less homogeneous. Opposing partisan groups cannot easily grasp and generalize the stances of a group with many disjointed beliefs (Agadullina & Lovakov, Reference Agadullina and Lovakov2018; Busby et al., Reference Busby, Howat, Rothschild and Shafranek2021). When such groups lack alignment, politics becomes hard to navigate.

More importantly, when more issues are interlinked within partisan camps, the disagreement between parties deepens (Layman & Carsey, Reference Layman and Carsey2002). This is because instead of disagreement on single policies, the contention becomes ideological and transcends across many issues. With low alignment, on the other hand, disagreement remains limited, as both camps are bound together by very few positions they share. As a result, fewer people from both partisan camps would disagree with each other. Also, their disagreement would be limited to the issue at stake, since those disagreeing groups would be heterogeneous in their other beliefs.

This reasoning assumes that ideological alignment is symmetric between both opposing sides. But how much does the disagreement change if one side is more constrained than the other? Using the scenario with two opposing camps, the situation when one camp is less aligned is not different from the situation when both camps are less aligned. The disagreement between the two camps is limited to issues on which the less aligned camp bundles as a part of its ideology. Although one camp is substantially constrained in political views, the disagreement cannot extend too many issues because the other camp is too heterogeneous (Schattschneider & Adamany, Reference Schattschneider and Adamany1975). When present, however, asymmetry in ideological alignment implicates that the deepening of partisan conflict depends more on belief realignment at a particular ideological pole.

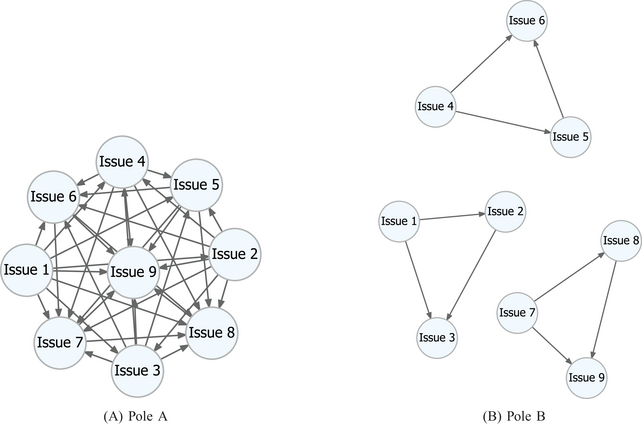

Let me illustrate this with a hypothetical scenario. Imagine two opposing partisan camps with divergent views on public policies (see Figure 7). One camp is highly constrained, with beliefs across issues interconnected (Pole A), while the other is less constrained, with some beliefs decoupled from others (Pole B). This difference in belief constraint across poles creates a scenario of asymmetry in ideological alignment. Now, suppose Issue 1 comes to the forefront of the political agenda. For partisans at Pole A, an interaction with the differently minded Pole B could trigger disagreement not only on Issue 1 but also on Issues 2 and 3, which are linked to it. However, this disagreement should not spill over to other issues, as at Pole B, some partisans may hold congruent views on Issues 4–6 or Issues 7–9, which are disconnected from the issue at hand. As long as one pole remains less constrained in beliefs, disagreement across the camps will be limited. The extent of political conflict depends on the interconnectedness of the less constrained pole. In asymmetric scenarios, the formulation of a more comprehensive ideology on the less connected pole determines the degree of partisan polarization.

Figure 7. Ideological alignment and partisan conflict: An illustration.

Note: Belief networks in this illustration could correspond either to the aggregate (group‐level) cohesiveness of parties at the two opposing poles or to the differences in alignment among average individuals within both camps. Regardless of the level, the argument for partisan disagreement remains valid.

This may be demonstrated in a specific policy. Let us say Pole A is an economically left‐wing partisan camp and Pole B is an economically right‐wing partisan camp, and Issue 1 is that of public debt. If right‐wing supporters connect the issue of public debt to their beliefs on taxation or welfare, but not to environmental regulation or public education, the conflict with the left‐wing pole will remain limited to a few issues and thus contained, regardless of the ideological alignment on the left. Unless an ideology emerges on the right that links these issues together, the extent of partisan conflict would not surpass moderate levels.

Suggestions for future research

There are significant implications of these findings for future research in several areas. For scholars studying ideological and affective polarization, there are multiple pertinent findings. First, the finding of asymmetry in ideological alignment parallels other asymmetries found in likes and dislikes of other partisans (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023). Although this study cannot provide an explanation for that effect, it suggests several possibilities. One possibility could be the reliance of radical right parties on the sociocultural dimension, where, according to these findings, beliefs are more symmetrically aligned across both opposing poles. Therefore, disagreement between opposing sides may extend more easily than on the economic dimension. The second pertinent finding is the belief in coherence within the camp on the ideological left. While such alignment can be viewed positively as a capability to understand politics and make an informed vote choice (Converse, Reference Converse2006; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Patel, Fahmy and Kaufman2014), it also raises concerns about the effects of group homogeneity, such as the propensity to receive and process information within ideological echo chambers (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Lawall and Tilley2024), which may ultimately foster intolerance towards differing views and increase polarization (Mutz, Reference Mutz2002). Third, there is the finding of diminishing asymmetry in ideological alignment on sociocultural beliefs, indicative of emergent ideological conflicts over ‘new politics’ issues. This might be a sign of troubling development as it suggests an extension of political conflict to this domain, reducing belief pluralism and exacerbating public opinion polarization (DellaPosta, Reference DellaPosta2020; Layman & Carsey, Reference Layman and Carsey2002). Future research may examine if this change is constitutive of a longer trend, or simply a situation specific to two unusual years for European politics (2008, 2016).

For those researching party politics, the substantial differences across ideological dimensions provide a ground for further exploration. Although I did not find overwhelming evidence for the effects of position blurring and programmatic nicheness on ideological alignment, the results suggest some impact on the economic ideological dimension. The finding of limited effect contrasts with some previous findings which indicate that supporters of niche parties might undergo an exacerbated process of sorting (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006, Reference Adams, Ezrow and Leiter2012). The position blurring research suggests that in cases of high blurring, ideological alignment should be more complicated (Han, Reference Han2022; Rovny, Reference Rovny2012), which is not conclusively supported either. However, some support for these effects was found concerning economic issues, though it is not clear why these findings do not extend to the sociocultural dimension.

Although this research focuses on European countries, it also contributes to the debate in the United States. Lelkes and Sniderman (Reference Lelkes and Sniderman2016) show that Republicans are more aware of and engaged with their party's ideology than Democrats. This may stem from the Republican elite's reluctance to align with the median voter on race or immigration issues, while the Democratic party has become a ‘big tent’ accommodating various social groups (Grossmann & Hopkins, Reference Grossmann and Hopkins2015). This discrepancy highlights that ideological asymmetry is not inherently tied to the left or right but depends on elite behavior, actor strategies, and contextual differences in ideology organization (Malka et al., Reference Malka, Lelkes and Soto2019).

Finally, this study is relevant for pundits, democracy promoters and anyone interested in alleviating partisan conflict. It shows that the formulation of comprehensive ideologies on the right is the most likely way for partisan conflict to deepen and spread across more issues. These changes may be more dependent on the homogeneity of partisan camps on the right. As demonstrated by sociocultural issues, some of this change may already be underway. As I show here, party ideological features might be of lesser importance. Instead, the observed asymmetry across various contexts suggests shared structural explanations. Although specific mechanisms are not tested here, addressing potential economic and cultural grievances (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2008) or bridging the education gap (van Noord et al., Reference Noord, Spruyt, Kuppens and Spears2023) – to name only some options‐could help prevent greater cohesiveness on the right.

Limitations

Although aiming for high robustness of results, I acknowledge some limitations of the current study design. First, this study does not address the underlying mechanisms or causality of change. Specifically, it does not explore the reasons for asymmetry in alignment, which may be influenced by differences in the programmatic appeals of parties or other factors, such as varying levels of activism across partisan groups. The observational data, primarily allowing for cross‐sectional comparisons, are not well‐suited to differentiate between established theories of alignment. These theories include mechanisms such as elite cues (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2001; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010a) or shifts in issue salience (Dennison & Kriesi, Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023). Additionally, although the data cover a range of sociocultural policies (e.g., gender, immigration, morality), they omit some newer political issues that may be relevant, such as minority rights or freedom of speech. Also, I do not focus on another aspect that matters for the relevance of this argument – which is how many people are partisan in a specific country. These numbers differ across contexts and provide an important aspect of conflict extension within the mass population (Schattschneider & Adamany, Reference Schattschneider and Adamany1975). Furthermore, I cannot conclusively explain the disappearance of asymmetry on sociocultural issues. The observed differences might result from within‐party program adjustments (Abou‐Chadi & Krause, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Krause2020) or the emergence of new challenger parties from the radical right, which exhibit similar effects (Bischof & Wagner, Reference Bischof and Wagner2019). Future research should aim to address these limitations by focusing on more granular longitudinal data in specific countries, thereby elucidating the nature of these changes and mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Marc Jacob, Leo Carella, Markus Wagner, Andrew Roberts, James Adams, Ruth Dassonneville, Sean Westwood and many others for their valuable feedback on the early drafts of this paper. This work was presented at the Networks of Political Beliefs Workshop within the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, the ECPR General Conference 2023, and the Midwest Political Science Association Conference 2024. This manuscript was proofread with the assistance of AI tools (GPT‐4). Finally, I appreciate the comments of the editors and anonymous reviewers. This publication was written at Masaryk University with the support of the Specific Research Grant provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic. This work was also supported by the Czech Science Foundation (GA22‐33158S).

Open access publishing facilitated by Masarykova univerzita, as part of the Wiley ‐ CzechELib agreement.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

This study utilizes publicly available datasets. Specifically, it employs the CHES data from 2006 and 2014, as well as the cumulative trend file covering 1999‐2019 (DOI: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102420). Additionally, it incorporates data from the ESS rounds conducted in 2008 (DOI: 10.21338/ess4e04_5) and 2016 (DOI: 10.21338/ess8e02_2), as well as the Manifesto Project Dataset (DOI: 10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2016b). All the code and data are available in the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/tadeascely/one_more_constrained.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure 1: Positions on Both Ideological Axes (two‐dimensional density plot), correlation = 0.47

Figure 2: Position Blurring on Both Ideological Axes (two‐dimensional density plot), correlation = 0.08

Table 1: Dependent Variable: Items

Table 2: Convergent Validity of Ideological alignment (strength of partisanship)

Table 3: Convergent Validity of Ideological alignment (ideological extremity)

Table 4: Representativeness of Included Parties

Table 5: Share of Partisans Among ESS Respondents

Table 6: Lost Cases Party Families Frequencies

Table 7: Factor Loadings with Reduced Set of Items

Table 8: CFA Goodness‐of‐fit Measures

Table 9: Robust Models ‐ Positions

Figure 3: Predictions for Robust Models

Table 10: Party Inconsistency Model Estimates

Data S1