1.1 Introduction

In November 2021, England’s Environment Agency (EA) internally reported that it would no longer be able to fulfill its implementation tasks. The EA, founded in 1995, is responsible for implementing and enforcing large parts of environmental legislation. Over the years, the workload of the EA increased heavily, mainly because it had been charged with implementing an increasing number of policies, such as new measures related to the fight against climate change. Because the agency’s resources did not rise in lockstep with its increasing workload but were instead reduced through repeated budget cuts, the EA eventually had to do “more with less.” Seeing itself in an “unsustainable position,”Footnote 1 the EA responded by radically assessing its tasks and reassigning priorities. In what was internally called the “incidence triage project,” the agency decided to ignore low- and no-impact environmental incidents and instead concentrated its capacities on higher risk incidents. The consequences of the EA’s new system of prioritization were widely considered severe: EA officers (anonymously) remarked that it was usually impossible to ascertain an incident’s risk level without attending to it, making the ex ante prioritization of incidents pointless. This prioritization also meant there was a lack of a credible threat of enforcement for many pollution incidents, which discouraged people from reporting these incidents in the first place. EA officers and observers did not hide their frustration with executive politicians who charged them with evermore tasks while failing to provide them with additional resources.

There are good reasons to believe that the “anecdotal” case of the EA points to a general, yet largely neglected, challenge characterizing governance in modern democracies: the phenomenon of continuous policy growth and its consequences for policy implementation. There is compelling evidence that democratic governments have constantly added new policies, rules, and programs to existing policy stocks to confront societal, economic, and ecological challenges (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019; Hinterleitner et al., Reference Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2023; Jakobsen & Mortensen, Reference Jakobsen and Mortensen2015). Yet, while more policies should, in principle, help address pressing problems and improve our lives, such improvements presume that new measures are adequately implemented in the first place. Regardless of how ambitious they are, more policies are, at best, a necessary but insufficient condition for policies to reach their goals. To be effective, policies need to be put into action. They need to be applied, monitored, and enforced. Doing so requires sufficient personnel, money, and organizational structures (Dasgupta & Kapur, Reference Dasgupta and Kapur2020).

Consequently, the production of evermore policies has important implications for organizations in charge of policy implementation, as policy growth directly translates into the accumulation of administrative burdens when it comes to the practical application of public policies (Bozeman, Reference Bozeman2000; Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2020). If new policies are adopted without the parallel expansion of implementation capacities, policy growth ultimately leads to the overburdening of sectoral implementation bodies. Bureaucratic overload, in turn, might seriously undermine the overall implementation effectiveness and hence policy performance.

Strikingly, the challenges that emerge from implementing growing policy stocks have not been discovered analytically, let alone be systematically addressed so far. On the one hand, there is a growing body of studies addressing the causes and patterns of policy growth, however, without explicitly concentrating on the consequences for policy implementation. On the other hand, the vast body of implementation research, which can look back on a long tradition, has come up with a rich collection of factors that might account for variation in implementation effectiveness, but completely ignored the phenomenon of policy growth in this regard.

In this book, we address this research gap. We analyze the consequences of policy growth for implementing public policies. We provide answers to two fundamental questions: First, being interested in the relationship between policy growth and the behavior of organizations in charge of implementation, we ask: To what extent does the growth of policy stocks and the associated growth of implementation burdens lead to an increase in organizational implementation problems? Rather than concentrating on the implementation of individual policies, we adopt an organizational perspective capturing the extent and proliferation of implementation problems for the aggregate of the policies within an organization’s portfolio. In this regard, we conceive of implementation deficits as “policy triage”; that is, the extent to which organizations make trade-offs in allocating their limited resources while carrying out their work. While policy triage comes in different forms in practice, we argue that any trade-off decision essentially entails that certain implementation tasks are neglected or delayed in favor of other duties.

Second, we are interested in the factors that explain variation in the degree of policy triage across implementation bodies and over time. How can we explain that implementation bodies differ in the prevalence of policy triage? Why is it that some organizations can absorb growing implementation burdens without facing problems of bureaucratic overload, while others have to resort to triage decisions? In this book, we suggest a novel theoretical argument that accounts for the variation in the prevalence of policy triage. More specifically, we claim that the latter is affected by the interplay of three factors, namely, (1) limitations for policymakers to shift the blame for implementation failures; (2) the potential of implementation bodies to mobilize for resource expansions; and (3) organizations’ commitment to optimize implementation effectiveness via internal reform efforts and “policy repair.” While the first two factors refer to the overload vulnerability of organizations in charge of implementation, the latter captures aspects of organizational overload compensation.

In this introductory chapter, we first show how the underlying study contributes to central debates and research gaps in Public Policy and Public Administration, including studies on government overload, policy growth, as well as policy implementation and street-level bureaucracy. Based on this assessment, we briefly present the main argument of this book before outlining the book’s structure and plan.

1.2 Government Overload, Policy Growth, Policy Implementation, and Street-Level Bureaucracy

In view of our underlying research focus, there seem to be at least three research areas related to this study. First, our focus on organizational overload complements earlier debates on “governmental overload” that evolved from the 1970s onwards. Second, our study contributes to a growing body of literature that emphasizes the growth (or accumulation) of sectoral policies and rules as a consistent trend characterizing governance in modern democracies. Third, by studying overload-driven patterns of organizational policy triage, this study provides novel insights for research on policy implementation and street-level bureaucracy.

1.2.1 Government Overload

This book resonates with debates on government overload and “ungovernability” that gained attention in the 1970s (Crozier et al., Reference Crozier, Huntington, Watanuki and Commission1975; King, Reference King1975; Rose, Reference Rose1979). At the core of this debate was the concern that democratic governments were increasingly incapable of meeting society’s expanding demands. As democratic policymaking came to be viewed as responsible for solving problems across nearly all areas of life, analysts feared that the growing pressures would hamper governments’ ability to make effective decisions. This, in turn, could erode their perceived legitimacy, potentially leading to democratic decline, indicating a bleak future for democratic government, which some observed underscored with dramatic language and doomsday scenarios (see Brittan, Reference Brittan1975: 129; Crozier et al., Reference Crozier, Huntington, Watanuki and Commission1975: 2; Schäfer, Reference Schäfer2009).

From the perspective of ungovernability theorists, the state becomes overwhelmed due to a mismatch between the demands placed on it and its capacity to meet them (Crozier et al., Reference Crozier, Huntington, Watanuki and Commission1975; Huntington, Reference Huntington1975). Government overload results from two main causes: First, there is a constant increase in demand for state intervention. In secularized states, aspirations for salvation were projected onto the state, which came to be seen as responsible for individual happiness in place of fate, personal effort, or divine intervention. As King (Reference King1975: 288) put it, “Once upon a time, man looked to God to order the world. Then he looked to the market. Now he looks to government.” This “politicization of happiness” (Matz, Reference Matz, Hennis, Wilhelm and Matz1977: 94) inevitably overwhelmed a state that was now held responsible for all personal misfortunes. Second, overload is reinforced by the competition among political parties, which drives them to make evermore ambitious promises to win votes. In a democracy, there is an incentive for parties and governments to respond to the demands of electorally significant groups.

Taken together, the crisis of democracy was thus seen as the inevitable result of a “revolution of growing demands” (Bell, Reference Bell1991: 32) that politics had stirred but could not satisfy (Held, Reference Held2006), leading to the expectation of ungovernability. Particularly during the 1970s, as analysts observed social unrest, economic crises, and rising public demands in Western democracies, democratic institutions were seen as increasingly incapable of producing effective policy responses accommodating conflicting and powerful interest groups.

Yet, these concerns have not fully materialized. Democratic governments have responded to diverse societal demands by expanding their involvement across many facets of life. In fact, despite – and partly due to – slowing economic growth, democracies have increased the volume of legislation and continuously added to their policy portfolios (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019). Contrary to the overload hypothesis, democratic governments maintained their capacities to take decisions and to respond to societal demands, leading some observers to acknowledge “the slow death of the overload thesis” (Roberts, Reference Roberts2014).

At the same time, however, the way governments managed overload challenges came with a pronounced shift in the focus of state activity from distribution and redistribution to regulation. The 1980s and 1990s witnessed the rise of the regulatory state (Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2014; Majone, Reference Majone1994). Rather than engaging in the public provision of services themselves, governments have increasingly relied on the regulation of privatized public enterprises and addressed the negative externalities of market activities through a growing bulk of social and environmental regulations. At the same time, regulatory activities were driven by the integration of global and European markets. Regulation not only allowed governments to address societal demands effectively but also partially avoided budgetary constraints and conflicts associated with distributional policies. This is mainly because the costs of regulatory policies occur at the level of those actors targeted by a policy (typically the private sector) and have only limited fiscal implications (Jordana & Levi-Faur, Reference Jordana, Levi-Faur, Jordana and Levi-Faur2004; Knill & Tosun, Reference Knill and Tosun2020).

However, although governments thus could escape the originally diagnosed overload problem, the ongoing accumulation of policies and regulations has introduced a new kind of overload. Unlike the concerns raised in the 1970s, this form of overload does not primarily challenge policymakers’ decision-making capacity; rather, it risks overwhelming administrative systems in charge of policy implementation. More precisely, we argue in this book that the problem of government overload is not a problem of lacking capacities to respond to societal demands and lacking capacities to achieve political decisions in the presence of strong distributional conflicts dominated by powerful particularistic interest groups (Olsen, Reference Olsen1991). Instead, government overload is rather a problem of sustained democratic responsiveness and the resulting accumulation of policies, which increasingly overburdens the administrative capacities for implementing these responses (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019, Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2022).

1.2.2 Policy Growth

The fact that – contrary to the original government overload hypothesis – sectoral policy stocks in modern democracies display remarkable patterns of pronounced growth has been systematically studied rather recently, with students of Public Policy (and adjacent disciplines) shifting their attention from the study of the formulation of individual policies to the aggregate patterns emerging from continuous policy adoptions (Kaplaner et al., Reference Kaplaner, Knill and Steinebach2025). A growing number of publications point to the prevalence of accumulation patterns in recent years, emphasizing that policy stocks are expanding over time across countries and sectors. The phenomenon of policy growth has been described and captured from different analytical angles, including the concepts of “policy accumulation” (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019), “rule growth” (Jakobsen & Mortensen, Reference Jakobsen and Mortensen2015), “policy layering” (Daugbjerg & Swinbank, Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2016), “policyscapes” (Mettler, Reference Mettler2016), or “legislative growth” (Kosti & Levi-Faur, Reference Kosti and Levi-Faur2019). Although these concepts display important differences in their analytical focus, they all observe that governments effectively adopt more rules and policies over time than they abolish.

Aside from providing detailed insights on patterns of policy growth across countries and sectors (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019), research has identified various drivers and factors affecting patterns of policy growth, which broadly resonate with the drivers identified as leading to governmental exhaustion in research on government overload (see preceding text). Policy growth is not only driven by vote-seeking politicians who aim to demonstrate their responsiveness to public and interest group demands by addressing the challenges citizens care about (Gratton et al., Reference Gratton, Guiso, Michelacci and Morelli2021). Policies are also governments’ main problem-solving tool because they allow them to deal “with issues and problems as they arise” (Orren & Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2017: 3).

However, while there are strong political incentives to produce new policies, it is hardly rewarding politically to dismantle existing policies, even when they have turned out to be ineffective. Policies, once adopted, create expectations and dependencies for their beneficiaries, and they are thus challenging to terminate or dismantle (Bardach, Reference Bardach1976; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Jordan, Green-Pedersen and Héritier2012; Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2020; Pierson, Reference Pierson1994).

Political incentive structures therefore result in governments typically adopting more policies than they eliminate over time, regardless of the policy sector in question. Yet, the effects of political incentives on policy growth are moderated by a range of variables, such as the patterns of vertical coordination between policy-producing and policy-implementing bureaucracies (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Knill and Fernández-i-Marín2017; Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2021b), the effects of party ideology (Jakobsen & Mortensen, Reference Jakobsen and Mortensen2015), as well as endogenous growth dynamics arguing that rules once adopted create a constant need for the development of additional laws and regulations (“rules breed rules”) (March et al., Reference March, Schulz and Xueguang2000; van Witteloostuijn & de Jong, Reference van Witteloostuijn and de Jong2010). Moreover, crisis events often constitute an “accumulation ratchet” (Knill & Steinebach, Reference Knill and Steinebach2022: 2). They trigger events of policy and rule growth, and these effects are not reversed once the crisis is over.

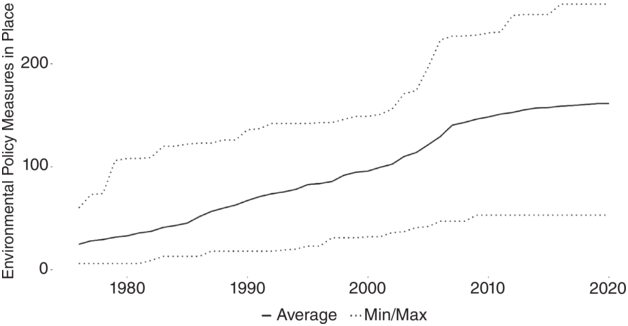

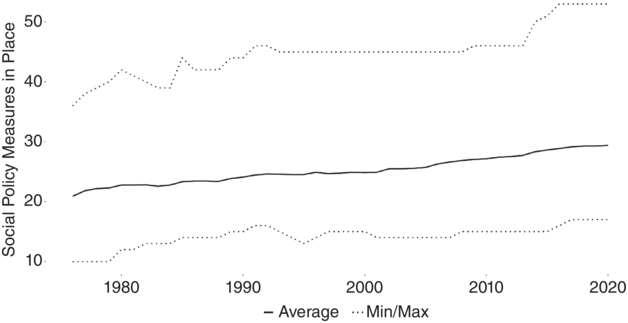

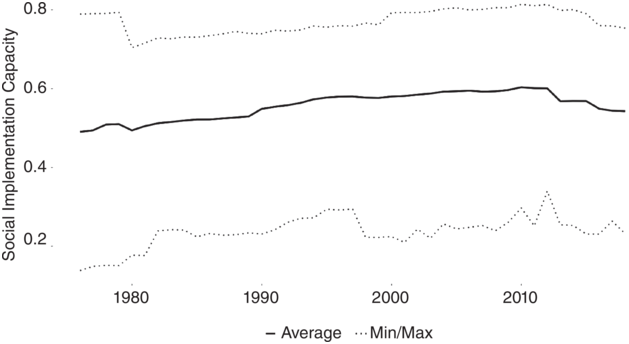

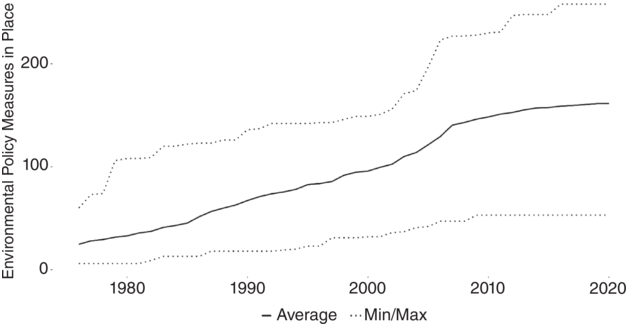

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 provide an empirical impression of the dynamics of policy growth over a period of more than four decades (1976–2020) for twenty-one Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countriesFootnote 2 (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019, Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2022; Fernández-i-Marín et al., Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2023a, Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2023b). The figures display how the number of environmental and social policies developed on average for the countries scrutinized during the observation period. For both policy areas, we see that there has been a constant increase in policies over time. While policy growth is more pronounced for the environmental field, which constitutes a relatively young and dynamic area, it is remarkable that we also observe substantive increases in the more mature and saturated field of social policy.

Figure 1.1 Environmental policy growth in twenty-one Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

Figure 1.2 Social policy growth in twenty-one Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

Yet, research on policy growth has mainly focused on the adoption of new programs, rules, and laws. The major concern has been policy outputs. Systematic investigations of the outcomes and impacts of this output growth, by contrast, have remained rather rare. The literature acknowledges that policy growth is not a problem per se. The production of (new) public policies often means that problems are addressed, public demands are satisfied, and potentially conflictual situations are regulated, if not solved (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Reher and Toshkov2019; Wlezien & Soroka, Reference Wlezien and Soroka2016). The production of environmental policies, for instance, helped to reduce air and water pollution substantially (Steinebach, Reference Steinebach2019, Reference Steinebach2022). However, the literature has also shown that this positive link between policy growth and policy performance is far from straightforward if policy growth is not backed by an expansion of administrative capacities for implementation. Limberg et al. (Reference Limberg, Steinebach, Bayerlein and Knill2021), for instance, find that new policies lead to improvements of sectoral policy performance only if they are matched by a simultaneous increase in administrative capacities. Likewise, Fernández-i-Marín et al. (Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2022) show that a widening “gap” between the policies up for implementation and available implementation capacities generally leads to a decrease in the effectiveness of public policies, implying that at some point additional policies make no difference whatsoever or, even worse, decrease overall sectoral policy performance.

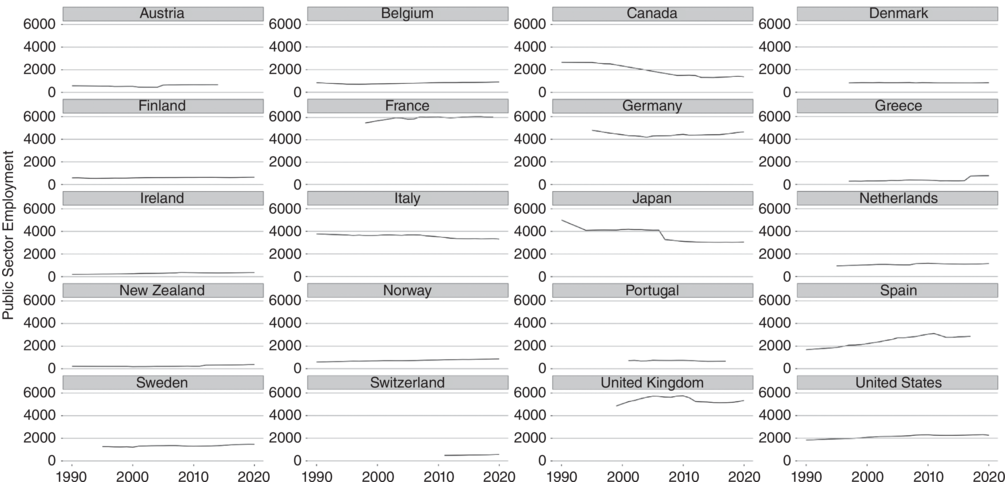

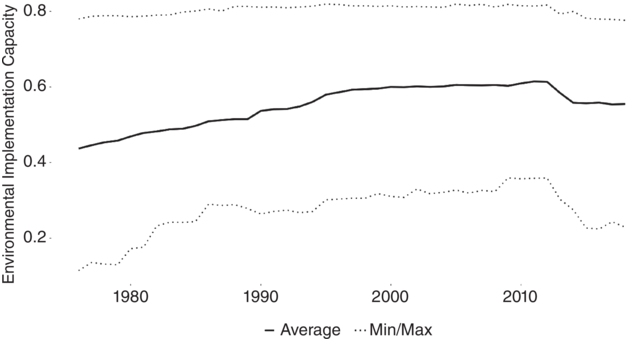

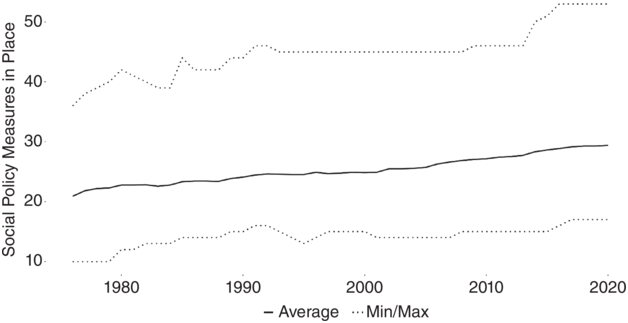

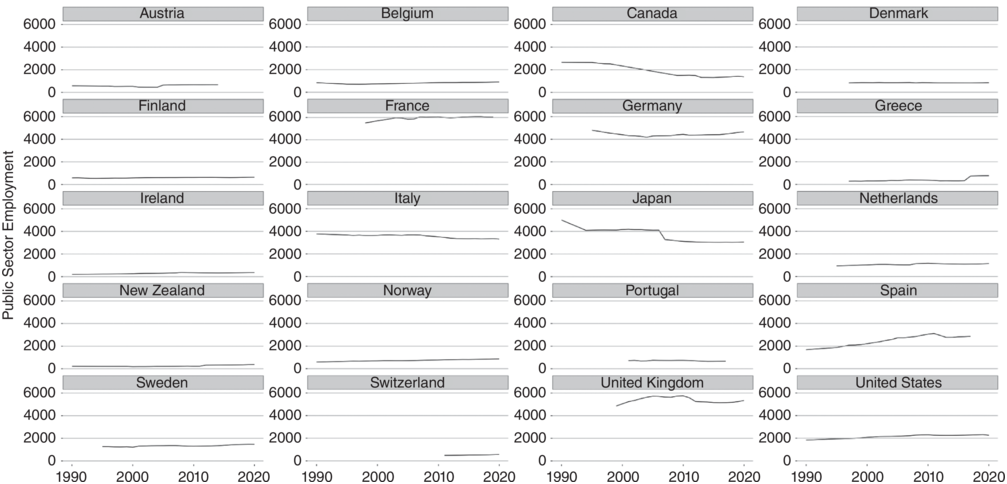

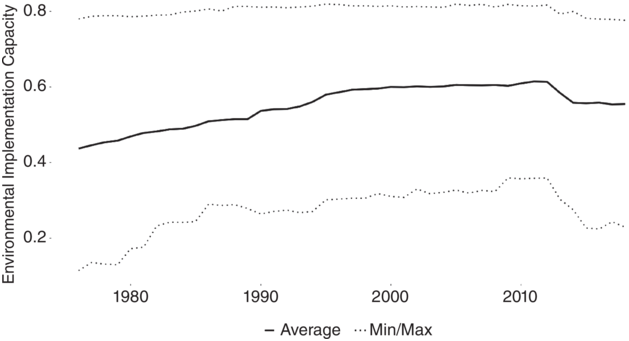

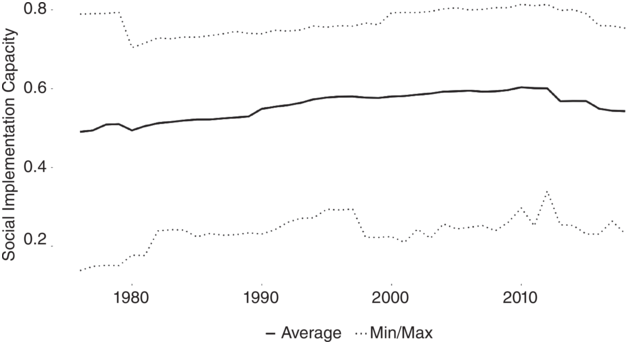

Figure 1.3 shows that such a scenario of a widening gap is entirely plausible. It provides information on the average development of public sector employment for twenty of the twenty-one OECD countries reported earlier (International Labour Organization, 2020).Footnote 3 Contrary to the rather dynamic growth of environmental and social policy stocks, there is a clear indication that public sector employment did not rise in lockstep with policy stocks. Instead, we see an overall trend of stagnation and even a slight decline, notwithstanding certain variations across the different countries. This overall impression is corroborated when taking a broader perspective on the development of sectoral administrative capacities more generally, taking account of the fact that public sector employment only captures a particular dimension of these capacities. When we look at different core dimensions of administrative capacity, as provided by a sector-specific administrative capacity index by Fernández-i-Marín et al. (Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2023a; see Figures 1.4 and 1.5), a similar pattern of stagnation emerges. Although both public sector employment data and the administrative capacity index only provide broad macro-level assessments and hence are only crude indicators of implementation capacities, these data nonetheless show that there is need for a more systematic assessment of the relationship between policy growth and available implementation capacities.

Figure 1.3 Public sector employment in twenty Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

Note: The figure displays the total employment number in general government for twenty OECD countries between 1990 and 2020. The numbers are presented in thousands, except for the United States, which are indicated in tens of thousands.

Figure 1.4 Environmental implementation capacity in twenty-one Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

Figure 1.5 Social implementation capacity in twenty-one Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

In sum, the phenomenon of constant policy growth has not remained unnoticed, and the existing literature has made some headway in understanding the patterns and drivers of evermore policies and rules. Yet, limited attention has been paid to the consequences of policy growth at the implementation stage. In addition, existing studies adopt a rather macro-conception of administrative capacities. In other words, the sectoral administrative capacities available are deemed (in)sufficient to handle large policy stocks – no matter where exactly the implementation burdens fall in a given sector. Yet, we know from the study on policy implementation that it makes a crucial difference who exactly is in charge of policy implementation and how the implementers deal (“cope”) with implementation stress and burden. As will be discussed in the following, the literature on policy implementation and street-level bureaucracy, in turn, suffers from distinctive blind spots when it comes to studying the link between policy growth and policy implementation.

1.2.3 Policy Implementation and Street-Level Bureaucracy

The central focus of implementation research is on the process of transforming political programs into concrete actions of administrative agencies in charge of execution, monitoring, controlling, and enforcing public policies (Knill & Tosun, Reference Knill and Tosun2020). In reality, there is often a lack of congruence between policy objectives and the transposition of these objectives. Implementing agencies do not always completely follow the initially agreed on policy objectives, and even if they do so, the results achieved may deviate from political expectations. These general discrepancies between initial objectives and actual results are discussed under the heading of implementation deficits.

Pioneered by Pressman & Wildavsky (Reference Pressman and Wildavsky1973), implementation research demonstrated already in the 1970s that great deviations and shifts in objectives can occur during the execution phase. While it has become conventional wisdom that the proper implementation of a policy is anything but trivial, research has not yet succeeded in sorting out the relative importance of the different explanatory factors accounting for the variation in policy success. Instead, it has created a long “checklist” of potential determinants (Winter, Reference Winter, Peters and Pierre2012). These include the choice and design of policy instruments (Fernández-i-Marín et al., Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Knill and Steinebach2021; Howlett & Ramesh, Reference Howlett and Ramesh2016; Jordan & Moore, Reference Jordan and Moore2022); the channels and venues through which central policymakers control the implementation process (Jensen, Reference Jensen2007); the institutional design of implementation structures (Lundin, Reference Lundin2007; Steinebach, Reference Steinebach2019); as well as administrative capacities (Börzel, Reference Börzel, Knill and Lenschow2000; Limberg et al., Reference Limberg, Steinebach, Bayerlein and Knill2021).

Although these studies have advanced our understanding of individual implementation processes, we lack a holistic perspective on the prevalence of implementation deficits at the organizational level of implementation bodies that systematically take account of interdependencies across different policies in organizational policy stocks. Given an organization’s constrained administrative capacities, effective implementation of a newly adopted policy “A” might come with the deficient implementation of already existing policies “B” or “C,” as implementers shift their priorities, thereby decreasing the overall organizational implementation performance. No matter whether implementation is analyzed top-down or bottom-up (Hupe & Hill, Reference Hupe and Hill2007), the focus on potential deficits remains policy oriented rather than organization oriented.

The general neglect of bureaucratic overload does not mean that implementation studies overall ignored the role of administrative capacities as a factor affecting implementation effectiveness. However, the analysis of administrative capacities suffers from several weaknesses. First, administrative capacities are typically discussed as a static factor, which is relatively stable over time; that is, changes in the sufficiency of the capacities given are not explicitly considered. Second, administrative capacities are analyzed at the macro-level for entire countries or policy sectors without acknowledging potential capacity variation across implementation bodies (Börzel, Reference Börzel2021; Fernández-i-Marín et al., Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Knill and Steinebach2021; Limberg et al., Reference Limberg, Steinebach, Bayerlein and Knill2021). Third, administrative capacities are merely conceived as a feature of the organizational design of implementation structures. The question here is on the most appropriate arrangements in order to ensure effective implementation rather than on problems of bureaucratic overload. This is in addition to debates whether public policies are typically implemented through a “single lonely organization” (Peters, Reference Peters2014: 132) or whether making a program work effectively requires the cooperation and coordination of multiple organizations (Michel et al., Reference Michel, Meza and Cejudo2022; Sætren & Hupe, Reference Sætren, Hupe, Ongaro and Van Thiel2018). The literature on collaborative governance analyzed the involvement of multiple actors from both the public and the private sector in policy implementation (Sager & Gofen, Reference Sager and Gofen2022; Thomann et al., Reference Thomann, Hupe and Sager2018). The central insight from this latter strand of research is that the implementation outcome of collaborative arrangements is ambiguous: Collaborative governance might facilitate policy implementation but also comes with some serious challenges in terms of governmental implementation capacities (Bertelli et al., Reference Bertelli, Clouser McCann and Travaglini2019).

While implementation research hence has remained rather blind to bureaucratic overload, research on street-level bureaucrats – who are perceived as crucial players influencing policy outcomes through their role as implementers of public policy – rests on overload as the/its central assumption (Cohen, Reference Cohen2021; Hupe, Reference Hupe, Van de Walle and Raaphorst2019). As Lipsky (Reference Lipsky2010) points out, street-level work is typically restricted by the scarcity of resources. Bureaucrats resort to coping practices to deal with overload, implying a divergence from initial policy objectives (Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Bekkers, Vink and Musheno2015). Coping strategies thus constitute a major source of implementation deficits and emerge as an unavoidable consequence of chronic overload (Gofen, Reference Gofen2014; Sager et al., Reference Sager, Thomann, Zollinger, van der Heiden and Mavrot2014). Yet, by simply assuming that street-level bureaucrats are overloaded, the research strand neither takes account of varying levels of overload nor does it assess the impact of changes in overload degree over time. Moreover, given its exclusive perspective on street-level bureaucrats, an actor-centered perspective prevails that provides little analytical leverage for assessing the implementation behavior at the meso-level of organizations.

1.2.4 Prevailing Research Gaps

In summary, we have seen that the topic of overload has a long career in studying challenges of democratic governance. Concerns of government overload and ungovernability were already raised during the 1970s, with the main expectation that democracies will increasingly struggle to take decisions to respond to the demands of their societies. Although these fears ultimately proved to be unwarranted, scholars who focused on government overload overlooked a crucial aspect: that the potential strain on democratic governments lies less in decision-making and more in the realm of implementation. While governments have successfully maintained their responsiveness to growing societal demands, this increased activity may simultaneously overburden the bureaucracies responsible for executing the expanding array of policies. In this book, we address this research gap and focus on the question to what extent and with which consequences democratic responsiveness creates government overload at the implementation level.

We have also seen that when scrutinizing the more recent literature that scholars of Public Policy and Public Administration have largely neglected the phenomenon of policy growth and its potential consequences on policy implementation. Studies on policy growth have been primarily concerned with examining patterns and causes rather than consequences of policy growth. Centrally, this is why existing research perspectives on policy implementation lack the necessary analytical sensors to capture potential problems of bureaucratic overload and organizational policy triage. These blind spots in implementation research result from two factors: First, implementation studies typically depart from a policy perspective concentrating on the implementation of individual policies in a given sample of countries. However, to provide an assessment of the effect of policy growth on implementation deficits, we require an organizational perspective that studies the implementation bodies’ performance in dealing with the overall stock of policies they are in charge of. Second, research has not systematically addressed the implementation challenges emerging from bureaucratic overload. Both aspects are addressed in this book.

1.3 Main Argument and Contributions: Organizational Policy Triage

The previous discussion has shown that the link between the phenomenon of policy growth and policy implementation has not been systematically detected and addressed by existing research. Studies of policy growth have not yet provided detailed insights on the impact of growing implementation burdens on implementation effectiveness that go beyond rather broad assessments of the relationship between accumulating policies and administrative capacities at the macro-level. Implementation research, by contrast, has not developed analytical sensors to capture the consequences of policy growth on policy implementation. The focus has been on studying individual policies rather than individual organizations. Hence, it does not allow for properly assessing trade-offs in organizations’ implementation efforts across different policies in their portfolio.

This book offers a novel approach to fill this research lacuna, bridging the gap between the macro-phenomenon of growing policy stocks, the microlevel analysis of implementation actors, and the implementation of individual policies. In doing so, we concentrate on the meso-level of implementation organizations. We study the extent to which these organizations are affected by bureaucratic overload emerging from policy growth, their behavioral routines in responding to overload, and the aggregate consequences of these actions for the implementation of policies in their areas of responsibility. Our units of analysis hence are organizations in charge of policy implementation in varying sectors.

We start from the proposition that implementing organizations vary considerably in the extent to which policy growth affects their implementation performance. Organizations are not only differently affected by growing policy stocks and hence differ in their risks of being overloaded but they also vary in how they can buffer and absorb overload challenges internally. In short, whether policy growth results in bureaucratic overload and thus deficient implementation varies between organizations.

To account for this variation, we focus on the interplay of three factors that can add to or substitute for each other in their effect on policy triage. First, political limitations for shifting the blame for implementation failures capture the extent to which policymakers have to take or may shift the blame for implementation failures stemming from bureaucratic overload. The extent to which policymakers can unload implementation burdens onto organizations can vary greatly, depending on the underlying institutional arrangements shaping processes of policy implementation. Depending on political blame-shifting limitations, implementation bodies are susceptible to varying degrees of being burdened.

Second, organizations might also vary in their opportunities to effectively mobilize for an expansion of their resources to deal with the growing burden load. For instance, implementation agencies might strongly vary in the strength of their political voice (in terms of articulating their positions) and their access to political decision-makers. Consequently, some organizations might be in a better position to gain additional resources for implementing growing policy portfolios than others.

Third, the commitment to overload compensation captures the extent to which implementation bodies are committed to absorbing and buffering overload to ensure the effective implementation of the policies in their portfolios; for example, by engaging in internal reforms or “policy repair” via the mobilization of organizational slack. We argue that such commitment cannot be taken for granted but depends on specific conditions. In particular, commitment toward overload compensation presumes organizational policy ownership; that is, bodies in charge of implementation appreciate the benefits of the policies in their portfolios and accept responsibility for them. In addition to policy ownership, policy advocacy strengthens organizational commitment to effective implementation. Policy advocacy focuses on the extent to which implementation bodies have developed organizational routines guided toward ensuring the quality, internal consistency, and effectiveness of their policies.

The configuration of these three factors determines whether the general trend of policy growth transforms into a growing gap between implementation burdens and available administrative capacities at the level of individual organizations. The more implementation bodies are at risk of being charged with additional tasks without parallel capacity expansions, and the lower their commitment is to compensate for this development internally, the more policy growth will fuel a proliferation of implementation deficits. By contrast, organizational implementation performance will remain largely unaffected by policy growth if implementation bodies are less vulnerable to being overloaded and display a higher commitment to overload compensation.

To assess the degree to which organizational overload results in reduced implementation performance, we rely on the concept of policy triage. Policy triage captures whether implementation bodies make trade-offs when allocating their (limited) resources to the different policies in their portfolios. Contrary to existing implementation research, we are not so much interested in the causes that determine the implementation effectiveness of individual policies. We rather focus on the overall performance of implementation bodies in handling the complete set of policies in their areas of responsibility. This way, we explicitly take account of trade-offs across different policies in an organization’s portfolio. Such trade-offs imply that organizations – implicitly or explicitly – prioritize specific tasks and policies up for implementation over others. Existing implementation research remains blind to such trade-offs, given its exclusive focus on single policies instead of policy stocks. Trade-offs across policies and implementation tasks will – as a matter of fact – necessarily increase with the scarcity of administrative capacities; that is, the higher the gap between implementation burdens and available capacities, the more organizations will resort to policy triage. In other words, when policy growth leads to bureaucratic overload, the prevalence of organizational policy triage will increase. In turn, such increases in organizational policy triage will undermine organizational implementation performance. The more agencies must weigh which policies to neglect in favor of other policies up for implementation, the lower the aggregate level of implementation effectiveness for an organization’s overall policy portfolio.

In developing and empirically testing the abovementioned argument, this book offers a systematic and novel analysis of the implementation challenges associated with the policy growth phenomenon identified as a general feature of democratic governance. In so doing, the first central contribution of this book is the introduction of novel analytical concepts. Essential here is the analytical shift from focusing on individual policies to organizations and their implementation performance. We study how implementation authorities handle their policy portfolios; we analyze implementation performance with regard to policy stocks rather than policies. Only this perspective allows capturing implementation trade-offs across policies – a phenomenon that existing research has not been able to identify analytically so far. A further innovation of our approach is the novel conception of implementation deficits as organizational policy triage. By shifting the analytical focus from individual policies to the implementation of entire organizational policy portfolios, we show that implementation problems – in particular, in constellations of growing bureaucratic overload – essentially emerge from the need to make trade-offs in organizational resource allocation. The concepts developed in this book complement policy implementation research by emphasizing cross-policy trade-offs emerging from organizational capacity limitations.

Second, this book opens up new theoretical ground. We provide a theoretical argument that accounts for the effects of policy growth on organizational implementation performance – a phenomenon that has not yet been studied, let alone theoretically explored. We can account for variation in policy triage across organizations. By focusing on implementation and taking account of political and organizational factors, we move beyond mere country-based accounts of implementation performance. We show that the extent to which organizational implementation performance suffers due to policy growth varies not only across countries but – most importantly – within countries.

Third, in empirical terms, we provide an encompassing comparative assessment of the impact of policy growth on implementation organizations in six European countries, namely, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, and Portugal. These countries display high diversity in terms of national administrative traditions, general administrative structures, and administrative capacities. Our focus is on the study of implementation processes in the sectors of environmental and social policy. As with our country selection, our choice of policy fields allows us to test our argument across a wide range of contextual conditions. More precisely, studying both environmental and social policy allows us to test our argument across (1) different policy types (regulatory versus redistributive policies); (2) fields with different degrees of maturity (environmental policy as a relatively young field compared to social policy); and (3) quite different requirements for implementation (public service provision in social policy versus authorization, inspection, and planning in environmental policy). Across all countries under study, we scrutinize a broad range of diverse implementation bodies, including central agencies and local authorities. This setup allows systematic comparisons of policy triage across implementation bodies within the countries and sectors and between the countries under study.

1.4 Structure and Plan of the Book

In the chapters to come, we first develop our conceptual and theoretical argument in more detail (Chapter 2). We present our concept of policy triage as a measure of organizational implementation performance. In the second step, we present our theoretical argument, linking policy growth and (variation of) organizational policy triage. Chapter 3 outlines how these conceptual and theoretical considerations can be studied empirically. We elaborate in greater detail on our case selection and the operationalization of dependent and independent variables. Moreover, we elaborate on our methodological approach to collect empirical information on organizational policy triage.

Chapters 4 to 9 provide in-depth empirical analyses of policy triage in six countries under study. In these chapters, the central focus is on the explanation of the variation of policy triage across different national implementation bodies. While these chapters demonstrate the relevance of our theoretical arguments for diverse implementation bodies within distinctive national settings, Chapter 10 shows that our theoretical argument also holds when we relax the condition of similar national settings and compare triage across countries. Finally, in Chapter 11, we present an overview of our key results and critically reassess our conceptual and theoretical approach in light of our empirical findings. We discuss theoretical implications and some limitations to our study and conclude by pointing out future avenues for research.