Introduction

Even though the puzzle of one-party dominance inspired development of the literature with long tradition dating back to Duverger's (Reference Duverger, North and North1959) and Sartori's (Reference Sartori1976) seminal contributions, several weaknesses of this literature still limit our understanding of dominant parties and dominant party systems (DPS). Among the most relevant are the following issues: (1) conceptual ambiguities; (2) “inherited weaknesses” of the party system literature (Enyedi and Bértoa, Reference Enyedi and Bértoa2020, 18); and (3) a lack of theory testing in comparative research (Templeman, Reference Templeman2010, 4).

First of all, the literature suffers from a plethora of different conceptualizations of one-party dominance with many authors offering different criteria for identifying cases (see Bogaards, Reference Bogaards2004; Lindberg and Jones, Reference Lindberg, Jones, Bogaards and Boucek2010; Nwokora and Pelizzo, Reference Nwokora and Pelizzo2014). In addition, the authors often do not make clear differentiation between the party and the party system, an issue identified already by Sartori (Reference Sartori2005, 171).

Second, the literature suffers from what Enyedi and Bértoa (Enyedi and Bértoa, Reference Enyedi and Bértoa2020, 18) call the “inherited weaknesses”: (1) the bias towards studying certain regions and national-level party systems; (2) the bias toward studying certain historical periods; and (3) the lack of understanding of historical legacies such as authoritarianism and colonialism. These biases result in predominant focus on well-known cases of executive dominance from Europe (Italy, Sweden, Ireland, and Britain), Asia (Japan, Malaysia, and Taiwan), Latin America (Mexico), and Africa (South Africa), mostly for post-WWII era. This is evident in majority of important contributions such as Pempel (Pempel, Reference Pempel1990b), Giliomee and Simkins (Reference Giliomee and Simkins1999), Friedman and Wong (Friedman and Wong, Reference Friedman and Wong2008), and Carty (Reference Carty2022).

Finally, by “lagging behind” in comparative theory-testing (Templeman, Reference Templeman2010, 4), the literature offers limited comprehensive comparative insights into the symptoms and consequences of one-party dominance.

Motivated with the aim of advancing comparative, theory-testing research, which is founded in a clear conceptual framework, guided by a well-developed theoretical model suitable for both qualitative and quantitative methods, and supported by data on worldwide cases of executive dominance, the GDPS dataset was created. The dataset includes 187 cases of executive dominance in 106 independent countries from around the world for a period from 1900 until 2024. The collection of variables were identified based on the literature and structured to follow the phases of conceptually refined “evolutionary model” (Abedi and Schneider, Reference Abedi, Schneider, Boucek and Bogaards2010, 86) of DPS.

The research note proceeds as follows. In the first part, the theoretical basis and seminal contributions in the field which inspired the creation of the GDPS dataset are presented. The second part discusses the structure of the dataset and its linkage potential. Finally, the potential applications of the dataset, with the focus on some of the most important research topics in the field are examined. The note concludes with suggestions for further research.

Concepts and theory

One of the important early tasks in studying one-party dominance is to resolve the conceptual ambiguities in literature. As Templeman (Reference Templeman2012, 12) noted, these ambiguities revolve around two central issues: (1) what is the level of analysis (regime type, party, or party system); and (2) whether DPS occur in both autocracies and democracies or just in the latter. These conceptual ambiguities have a long history dating back to Sartori (Reference Sartori1976) who was among the first to make steps towards introducing conceptual rigor in the field but, as Nwokora and Pelizzo (Reference Nwokora and Pelizzo2014) noted more recently, even his framework on dominant parties and party systems needs improvement.

Despite conceptual ambiguities, recent contributions indicate that experts broadly agree on some key issues that can guide development of a clearer conceptual framework. Influential authors prefer “dominant party” and “dominant party system” over other terms like “predominance” (e.g., Templeman, Reference Templeman2010; Bogaards and Boucek Reference Bogaards and Boucek2010b; Carty, Reference Carty2022). Most of the authors also include cases of both single-party and coalition dominance, provided that the leading party remains the same through at least three electoral victories. Additionally, scholars generally accept the existence of DPS in both democratic and authoritarian regimes, if elections are contested by genuine opposition (e.g., Greene, Reference Greene2007; Templeman, Reference Templeman2012).

The conflation of the dominant party with the DPS needs to be resolved as well. By referring to Boucek's (Reference Boucek, Pennings and Lane1998) work on dimensions of dominance and Sartori's (Reference Sartori2005, 173) insights on system properties, we can distinguish between the two by acknowledging that while a party/coalition can dominate legislative and electoral arena by simply “outdistancing” its rivals (in Sartori's terms), only if that party/coalition dominates the government formation process for a certain period does a system emerge with two key properties: (1) the unimodal concentration of power, and (2) limited alternation in power (Nwokora and Pelizzo, Reference Nwokora and Pelizzo2014, 828). Mexico between 2012 and 2018 provides a good example of having a legislatively and electorally dominant party (Serra, Reference Serra2013) without the formation of DPS because of absence of executive dominance.

Taking into consideration the previous discussion, GDPS defines: (a) the dominant party as any party which “outdistances all the others” (Sartori, Reference Sartori2005, 171), be it in electoral, executive, or legislative arena (Boucek, Reference Boucek, Pennings and Lane1998); and (b) the dominant party system as a type of a party system which is established once the dominant party/coalition takes the highest executive office for at least three times in a row, after elections.

The GDPS operationalizes DPS drawing from several comparative contributions: Bogaards (Reference Bogaards2004), Lindberg and Jones (Reference Lindberg, Jones, Bogaards and Boucek2010), Anckar (Reference Anckar2009), Templeman (Reference Templeman2010), and Nwokora and Pelizzo (Reference Nwokora and Pelizzo2014). Bogaards (Reference Bogaards2004) requires legislative majority of a single party and a position of a president for at least three consecutive elections; Lindberg and Jones (Reference Lindberg, Jones, Bogaards and Boucek2010) demand that the dominant party holds at least 50% of the seats for at least three consecutive elections; Anckar (Reference Anckar2009) introduces qualified majority of cabinet seats and duration in office requirements; Templeman (Reference Templeman2010) requires at least one victory in a multi-party contested elections but demands at least 20 years in office; while Nwokora and Pelizzo (Reference Nwokora and Pelizzo2014) amend Sartori's framework to allow for coalitional, interrupted and alternating dominance.

While these authors disagree regarding some criteria, they share an important commonality: their cases include the dominant party which dominates the executive arena after having won at least three consecutive elections. To arrive at what Bogaards (Reference Bogaards2004, 175) would call “the simplest definition of party dominance” suitable for a large-N analysis, GDPS adopts a “lowest common denominator” approach for the following operationalization: the dominant party system is one in which the same party or unchanged coalition occupies the highest executive office in an independent country for a minimum of three consecutive elections in which the officeholder is determined. During the period of executive rule, at least one election must have permitted genuine opposition to participate.

This operationalization allows for identifying all variations of one-party dominance classified by Abedi and Schneider (Abedi and Schneider, Reference Abedi, Schneider, Boucek and Bogaards2010, 79–82) as: (1) single-party and coalitional, and 2) short-term (less than 18 years in power) and long-term (more than 18 years in power). Furthermore, even though it is very permissive regarding regime type, it still requires that executive dominance was confirmed in at least one contested election, and according to the constitution as suggested by Templeman (Reference Templeman2010). Scholars who would prefer stricter quality of democracy requirements or focusing on just one variant (e.g. single-party long-term), can easily build upon this operationalization and impose additional criteria regarding electoral democracy, term duration and variant of dominance by setting a threshold for the corresponding variables in the dataset.

When it comes to setting the dataset's theoretical foundations, one can identify several competing explanations: the “evolutionary model” (Abedi and Schneider, Reference Abedi, Schneider, Boucek and Bogaards2010, 86) of Pempel (Pempel, Reference Pempel1990b) and Giliomee and Simkins (Reference Giliomee and Simkins1999); resource theory (Greene, Reference Greene2007); game theory (Abedi and Schneider, Reference Abedi, Schneider, Boucek and Bogaards2010) and spatial models (Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy, Bogaards and Boucek2010). For GDPS, the model of Pempel (Pempel, Reference Pempel1990b) and Giliomee and Simkins (Reference Giliomee and Simkins1999) was chosen given its solid comparative background in both democratic and authoritarian regimes, extensive elaboration of DPS evolution, and wide potential for both qualitative and quantitative research. Its main weaknesses relate to the lack of clear operationalizations and consequently, poorly defined phases of demise and revival, which is where certain amendments will be required.

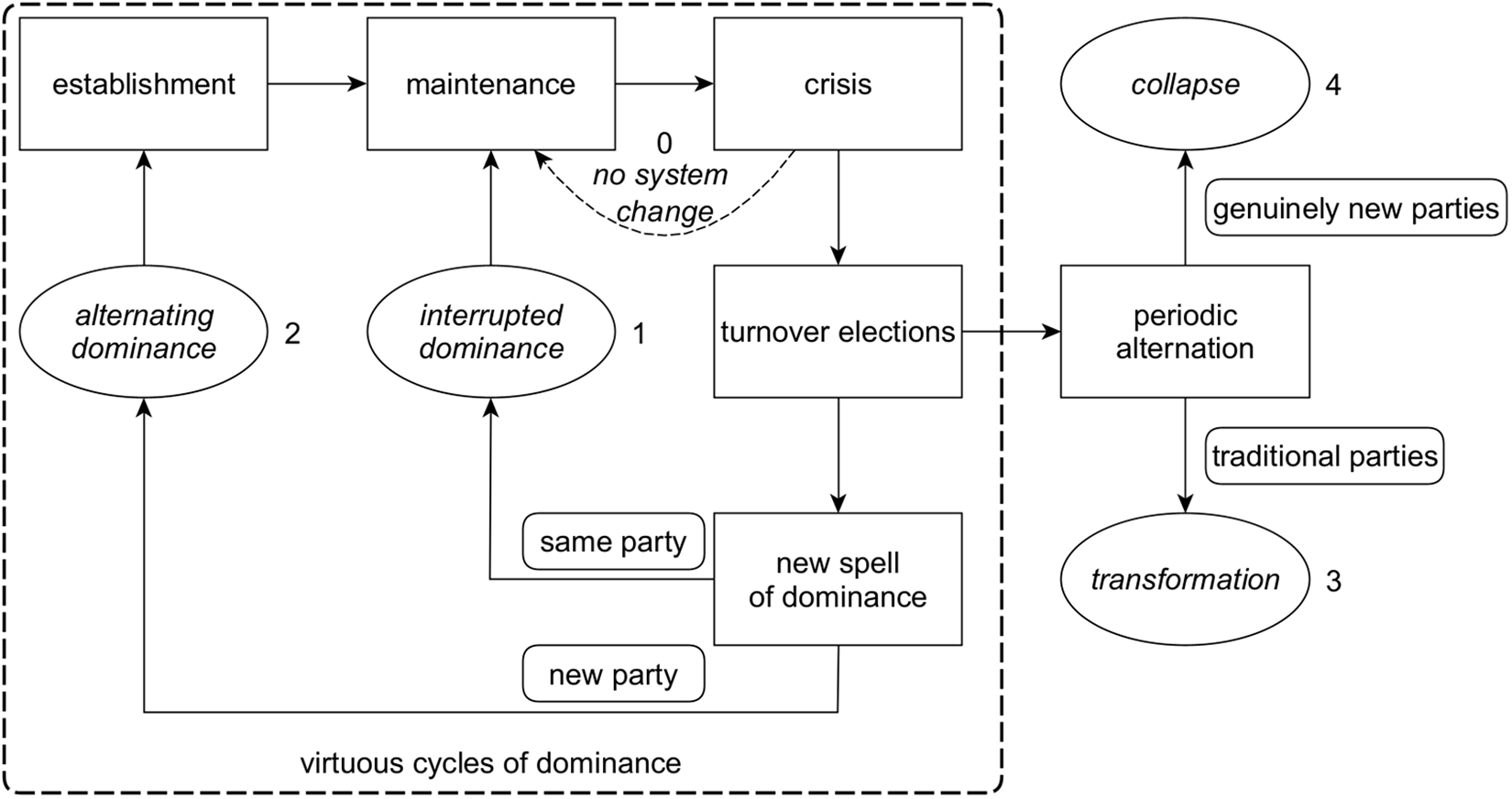

The model suggests that DPS develop through following phases: (1) establishment; (2) maintenance; (3) crisis, and (4) post-crisis. The establishment phase begins with the dominant party's first three consecutive victories, after which the system enters the maintenance phase which displays symptoms such as increased preference shaping (Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy, Bogaards and Boucek2010) and corruption (Pempel, Reference Pempel1990b). Over time monopolization of power erodes dominant party's support which leads the system into the crisis phase. While these phases have been explored elsewhere (e.g. Giliomee and Simkins, Reference Giliomee and Simkins1999; Friedman and Wong, Reference Friedman and Wong2008), more attention will be paid here to the post-crisis phase which has not been extensively defined in original works, and lacks party system change conceptual framework (Mair, Reference Mair1989; Smith, Reference Smith1989).

When the DPS enters crisis due to eroding popular support of the dominant party/coalition, anti-government protests and/or party splits (to give few examples), the party/coalition can try to adapt and keep winning (Friedman and Wong, Reference Friedman and Wong2008). If successful, this strategy can resolve the crisis and preserve the system while resulting in party-level changes (Friedman and Wong, Reference Friedman and Wong2008). Otherwise, a crisis may culminate in turnover elections, leading to varying degrees of systemic change:

1) The same party (or coalition) returns to power quickly, i.e. as soon as the next elections after the turnover elections and secures at least three consecutive terms in office after the elections. Based on Nwokora and Pelizzo (Reference Nwokora and Pelizzo2014), this smallest degree of system change is classified as interrupted dominance.

2) A new party (or coalition) manages to secure at least another three terms in office as soon as the next elections after the turnover election which, according to Nwokora and Pelizzo (Reference Nwokora and Pelizzo2014), is classified as alternating dominance.

3) Periodic alternation in government takes place which might or might not involve the former dominant party, but nonetheless involves mainly traditional parties (Seawright, Reference Seawright2012, 33), i.e. parties that have already contested elections before. This outcome, based on Sartori’s (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976/2005) framework, is classified as party system transformation.

4) Finally, based on the insights from the party system collapse literature (Morgan, Reference Morgan2011; Seawright, Reference Seawright2012), we know that a periodic alternation can take place in which the key role is played by the genuinely new parties (Sikk, Reference Sikk2005), while the dominant party either disappears or is reduced to electoral irrelevance. This is the greatest degree of party system change classified as DPS collapse.

In cases of outcomes (1) and (2), the DPS survives which represents Pempel's (Reference Pempel and Pempel1990a, 334–335) “virtuous cycles of dominance,” while in the cases of outcomes (3) and (4), it ceases to exist. The proposed theoretical model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The evolution and change of DPS. Note: numbers indicate degrees of party system change.

The dataset

The structure of the dataset is inspired by the refined evolutionary model, with variables being ordered according to establishment, maintenance, and crisis and post-crisis phases. The supplementary documentation provides details on how each case was identified and how complex situations (such as annulled elections and military interventions) were handled. The starting year was set to January 1900 to capture early cases of executive dominance in first institutionalized party systems that emerged at the end of 19th Century (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Bartolini and Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990), and although somewhat arbitrarily set, it presents a compromise between data availability limitations and a lack of more precise temporal agreement in the literature. To avoid regional biases, cases from all around the world have been identified and assigned to regions according to the United Nations Statistics Division (n.d.) criteria.

The variables included can be grouped as follows:

1) Democracy. Literature on authoritarian DPS (e.g. Greene, Reference Greene2007; Friedman and Wong, Reference Friedman and Wong2008) and their democratic counter-parts (e.g. Pempel, Reference Pempel1990b; Carty, Reference Carty2022) suggests that different aspects of democracy matter for different DPS variants. Therefore, data on electoral and liberal democracy from the LIED (Skaaning et al, Reference Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevičius2015) and V-DEM databases (Coppedge et al, Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, God, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Krusell, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Natsika, Neundorf, Paxton, Pemstein, Pernes, Rydén, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig, Wilson and Ziblatt2023) is included.

2) Economic growth. Contributions such as Greene (Reference Greene2007) and Pempel (Pempel, Reference Pempel1990b) indicate the importance of economic growth for the survival and demise of DPS. Therefore, data on GDP growth from World Bank, n.d.) is included.

3) Corruption. One of the most prevalent arguments in literature is that dominant parties breed corruption and that increased corruption eventually erodes dominance (e.g. Bogaards and Boucek Reference Bogaards and Boucek2010b; Pempel, Reference Pempel1990b). For this reason, data on corruption from the V-DEM database (Coppedge et al, Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, God, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Krusell, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Natsika, Neundorf, Paxton, Pemstein, Pernes, Rydén, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig, Wilson and Ziblatt2023) is included.

4) Population size. Anckar's (Reference Anckar2009) insights on executive dominance in small island states inspired the inclusion of the data on population size from “Our World in Data” platform (Global Change Datalab and Oxford Martin Programme on Global Development, n.d.).

5) Ethnic fractionalization. Scholarship on DPS in ethnically dived states such as Malaysia (Weiss and Suffian, Reference Weiss and Suffian2023) inspired the inclusion of the data on ethnic fractionalization from the HIEF database (Drazanova, Reference Drazanova2020).

6) Opposition fractionalization. Theoretical insights on divided opposition in DPS (Greene, Reference Greene2007; Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy, Bogaards and Boucek2010) inspired the inclusion of data on opposition fractionalization from the DPI2020 database (Cruz et al, Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2021).

7) Voter turnout. Dunleavy's (Reference Dunleavy, Bogaards and Boucek2010, 40) claims about the impact of voter turnout on the probabilities of re-establishing dominance inspired inclusion of data on voter turnout from IDEA (International IDEA, n.d.).

8) Electoral system. Theoretical insights on the effects of electoral system type on DPS (Pempel, Reference Pempel1990b; Boucek, Reference Boucek, Pennings and Lane1998) inspired inclusion of data on electoral system type from the IDEA database (International IDEA, n.d.).

9) Political system. Templeman's (Reference Templeman2010, 40) observation that survival rates of dominant parties in parliamentary and presidential regimes differ inspired including data on political system type from the DPI2020 database (Cruz et al, Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2021).

10) Party system change. Based on the literature on party system change (Mair, Reference Mair1989; Smith, Reference Smith1989) and party system collapse (Dietz and Myers, Reference Dietz and Myers2007; Morgan, Reference Morgan2011; Seawright, Reference Seawright2012), these variables contain data on government formation process for the period of three electoral cycles after the turnover elections and indicate what was the outcome of party system change in a given case.

The included variables can serve as useful empirical tools for theory testing, comparative hypothesis generation, and structured case selection. Though alternative variables and data sources could be proposed, the selection reflects a necessary trade-off between theoretical significance, data availability, and the practical need for a coherent, usable dataset. For easier insight into the dataset structure, a table with descriptive statistics for each variable is included in the Appendix.

It is important to note that, despite its potential, the GDPS dataset is limited to inclusion of only successful cases of dominance. In addition, while the 1900–2024 time span allows for inclusion of early cases, it can also introduce limitations regarding the availability and comparability of data across regions, particularly for pre-1945 cases and cases in small island states.

Dataset in practice

The GDPS Dataset can be utilized for much-needed theory testing. For example, scholars can examine the following pair of rival hypothesis: (1) Sartori's (Reference Sartori2005, 173–177) hypothesis about the fragility of DPS according to which DPS either transform or collapse quickly after the dominant party is defeated, and 2) Pempel's (Reference Pempel and Pempel1990a, 356–357) hypothesis about DPS longevity due to the “virtuous cycles of dominance.”

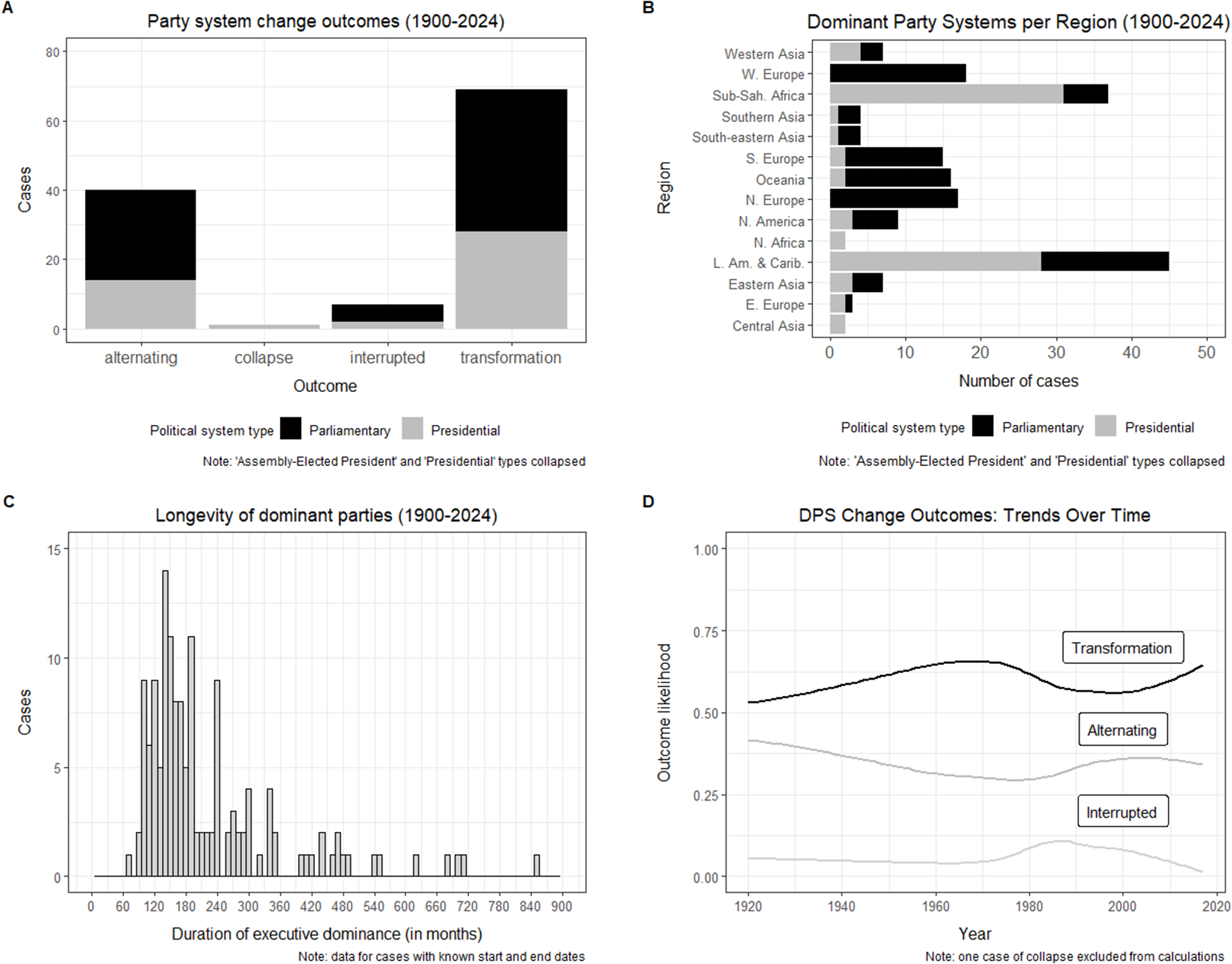

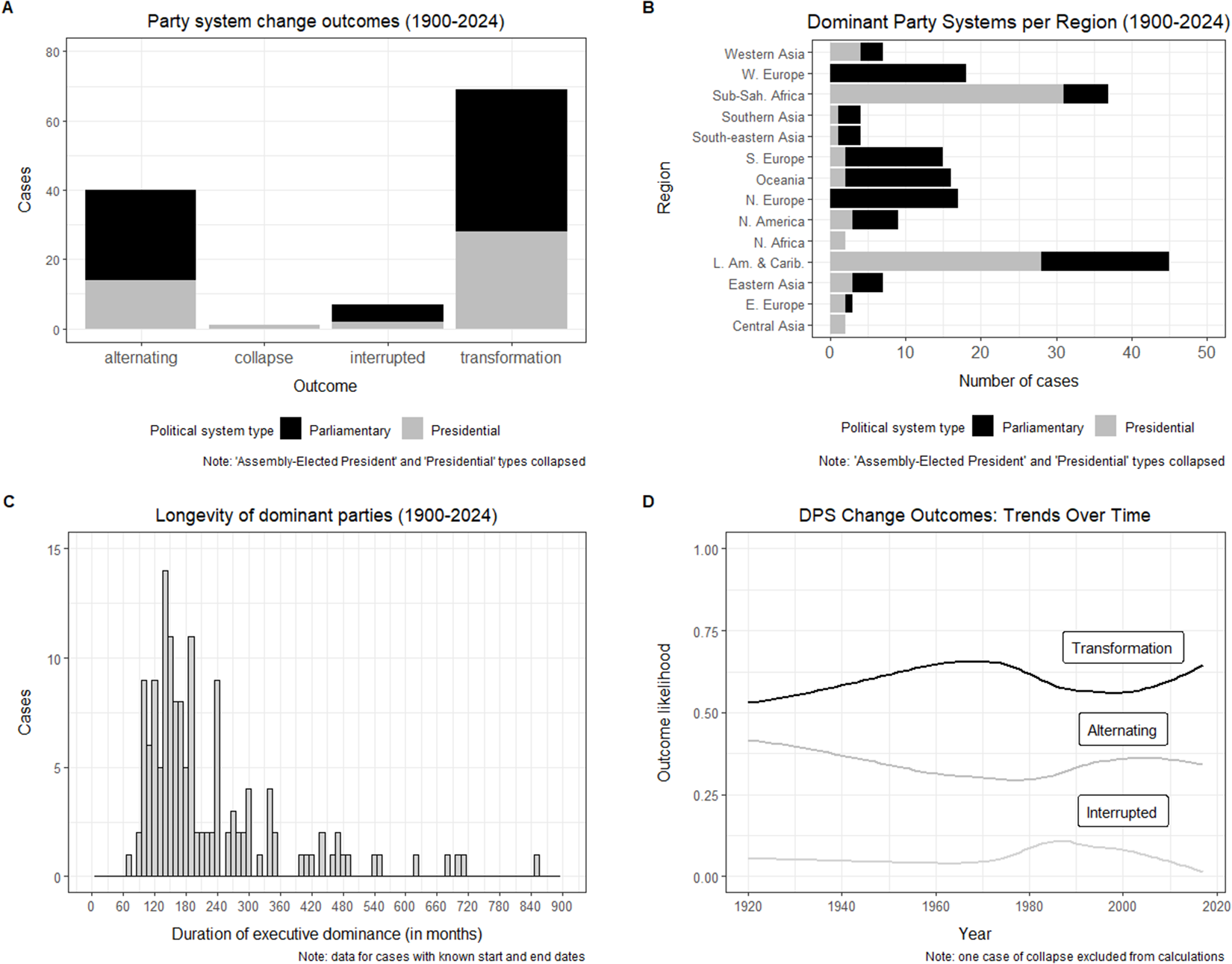

If we look at the outcomes of party system change (Figure 2, Plot A), we can see that DPS do indeed transform or collapse more frequently than survive after the turnover elections (70 cases out of 117). Additionally, we can see that over time the party system transformation is the most likely outcome compared to other outcomes of party system change (Plot D).

Figure 2. Empirical demonstrations of the GDPS dataset.

Future research can explore the puzzle of DPS change in a multi-variate setting or use the GDPS dataset to test a collection of hypotheses presented by Bogaards and Boucek (Bogaards and Boucek, Reference Bogaards, Boucek, Boucek and Bogaards2010a, 228), which are related to measurements, sources of one-party dominance and its consequences.

The dataset can also be utilized to explore regional patterns of dominance. For example, if we look at the global distribution of DPS (Plot B), we can see that two regions stand out by the number of cases: (1) Latin America and the Caribbean and (2) Sub-Saharan Africa. They also stand out by the number of cases of dominant parties in presidential systems. On the other side, all regions of Europe except Eastern Europe stand out by the number of cases of dominant parties in parliamentary systems.

If we focus on the longevity of dominant parties (Plot C), we can see that the shortest uninterrupted rule was just 70 months long (Progressive Conservative Party in Canada managed to secure three terms in office between 1957 and 1963) while the record holder is Mexico's PRI with 852 months in power, from 1929 until 2000. In line with Abedi and Schneider (Abedi and Schneider, Reference Abedi, Schneider, Boucek and Bogaards2010, 81), we can see that the duration of executive dominance is not normally distributed, further supporting their claim that arbitrary temporal cut-off points in the literature lack solid foundation.

Finally, the data on pre-1945 cases (not visualized here) reveal some interesting patterns. First, it is the presidential, not the parliamentary political system type that is omnipresent among the cases; and second, to paraphrase Bogaards (Reference Bogaards2004, 182), ‘dominant parties dominate in the Americas’ with 13 out of 20 pre-1945 cases belonging to the regions of Central, North, and South America.

Conclusion

Despite extensive research on DPS, comprehensive comparative analysis is hindered by conceptual ambiguities, regional biases, and the lack of theory testing. Inspired by the seminal contributions which made first steps in exploring DPS within the medium and large-N research design, the GDPS dataset offers scholars improved conceptual and theoretical framework, as well as a rich collection of data on cases of executive dominance from around the World. The proposed theoretical model can serve as a useful heuristic for qualitative research which would utilize process-tracing to explore the life cycle of DPS, while the data collected can aid both qualitative and quantitative research with the focus on important topics such as: democracy, corruption, and party system change. The empirical demonstrations show that the dataset can aid much-needed theory testing and the discovery of new temporal and spatial patterns.

Future research can improve the dataset by testing and refining the proposed model in process-tracing research, identifying new cases in autonomous regions and territories and/or in the so-called “de-facto” states (Ishiyama and Batta, Reference Ishiyama and Batta2012), and incorporating cases where there was no dominance to facilitate comparisons. It would be interesting to examine if the same symptoms of one-party dominance would appear in the expanded universe of cases, or some potentially different patterns would emerge depending on the level of the analysis.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Data

The GDPS dataset, codebook and the R code to create the four plots presented in this paper are available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2025.10068.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their time and effort – their detailed comments and constructive criticism helped me significantly improve the submitted manuscript. I would also like to extend my gratitude to my PhD supervisor, Matthew E. Bergman (Corvinus University of Budapest), for outstanding devotion, academic excellence in supervision and extensive support throughout my doctoral studies. Finally, and from the bottom of my heart, I would like to dedicate my work on dominant parties and party systems to my MA thesis supervisor, Prof. Robert Sata (Central European University).

Competing interests

The author declares none.