It was really a reputational issue. Kazakhstan wanted very much to be seen as a modern country, or it has aspirations for that. It wanted to be accepted.

Trafficking in persons was not a big priority for Kazakhstan’s government in the late 1990s. In 1999 the government’s National Commission on Women’s and Family Issues even declined to include trafficking in its list of priorities. However, after the 2001 TIP Report labeled Kazakhstan as Tier 3, interactions with the embassy spiked as high-level officials became concerned about this bad rating.

The use of public grades is a core element of scorecard diplomacy. This book argues that these grades are central in making countries receptive to broader diplomatic engagement. In a world more accustomed to “muscle diplomacy” this is odd. Why should meager grades make a difference, especially on issues that are not high profile? Why should countries care about a grade, especially if it is good enough to avoid consequences such as aid loss? And perhaps most puzzling: why should countries care what grades other countries get?

The answers to these questions lie in the concept of reputation. This chapter delineates the role of reputation in states’ behavior and explains how the features of scorecard diplomacy raise states’ concerns about their reputations. It argues that states care about their reputation not simply in terms of the credibility of their promises and threats, but more broadly in terms of how others perceive their performance. States want social recognition and governments care about their reputation vis-à-vis their citizens and the global community because this directly affects their standing and legitimacy to govern.Footnote 2

This desire means that others can seek to influence states by influencing their reputation. As others have noted, power “is a social process of constituting what actors are as social beings, that is, their social identities and capacities” to determine their fate.Footnote 3 While this has always been true, the digital age has made it cheaper to generate and disseminate criticism and accountability systems have become more transparent.Footnote 4 Thus, the ability to influence the reputation of states is an increasingly valuable tool.

Reputational concerns are only one of many factors that influence states. Sometimes it carries more weight than others. Reputational concerns won’t compel North Korea’s Kim Jong-un to resign or stop human rights repression in China, but it curbed the ability of the US to use torture and has tempered countries’ trade in weapons.Footnote 5 Furthermore, even if reputational concerns may not constrain China’s ability to repress human rights, it still imposes inconvenient costs that China must factor into its interstate relations.

This chapter has three parts. It first provides a broad definition of reputation and argues why it is valuable to states. It then creates a simple model to explain when states are more likely to worry about their reputation and act accordingly. Finally, it explains how scorecard diplomacy stimulates countries concern with their reputation.

***

The Concept of Reputation in International Relations

Some scholars argue that reputation matters “most in trade and security and least in environmental regulation and human rights”Footnote 6 because misbehaving governments know that while important allies or trade partners prefer to tolerate violations on soft issues like human rights rather than let misconduct spill over into higher priority areas like trade and security.Footnote 7

However, this pessimistic view rests on too narrow a use of the word reputation that equates reputation with “credibility of commitments,” or a reputation for resolve not to back down in the face of opposition.Footnote 8 Following this hard “reputation-as-credibility” logic, a reliable reputation enables states to gain from repeated cooperation with other states.Footnote 9 Reputation thus defined is about the predictability of a state’s actions and it signals a state’s military resolve or reliability as a partner on trade issues and so forth.Footnote 10 Indeed, reputation has become so synonymous with credibility of commitment that many use the terms almost interchangeably.Footnote 11 Even if reputation is defined more broadly as general beliefs about an actors’ behavior, its consistently applied narrowly to topics such as threats, retaliation, reliability as an ally, or treaty compliance, perhaps because the study of reputation came of age during the Cold War and the study of deterrence.Footnote 12 Some even call this the “rational dimension of reputation that is chiefly of interest to economists and most political scientists,” as if other dimensions of reputation are irrational or of less interest.Footnote 13 It is unfortunate that the concept of reputation has become shorthand for this narrower meaning.Footnote 14 As a result, much of the empirical research on “reputation” has focused on issues that involve iterated cooperation, such as security and economic issues.Footnote 15

A Broader Definition of Reputation

In the spirit of Malthus who advocated that scholars use words according to their common understanding, this book uses the word reputation broadly and more consistently with everyday usage.Footnote 16 Rather than being foremost or only about credibility of threats or promises, reputation here refers to the basic Merriam-Webster dictionary definition as the “the common opinion that people have about someone or something,” or “the overall quality or character as seen or judged by people in general.”Footnote 17 That is, a state’s reputation reflects how others view it or – where responsibility can easily be allocated – its officials.Footnote 18 Reputations are usually based on past behaviors and can be updated with new information that indicates changes in the track record.Footnote 19 Reputation in this broad sense is not just about keeping promises; it’s about perceptions of performance, both in terms of processes and outcomes across a range of issues. Thus, reputation is about character more broadly. Such a conceptualization that includes a notion of reputation as image or status has long existed. It is akin to what some now call “social reputation,” or “diffuse reputation or image,” which is the “the package of favorable perceptions and impressions that one believes one creates through status consistent behavior.”Footnote 20

Reputation is not a fixed property but is in the eye of the beholder. States can have reputations in relation to multiple actors: citizens, national elites, other governments, and the global community. These audiences may assess a state’s reputation differently depending on which standards they each use, what they know, or how they weigh the evidence.Footnote 21

Reputation, Behavior, and the Existing Normative Environment

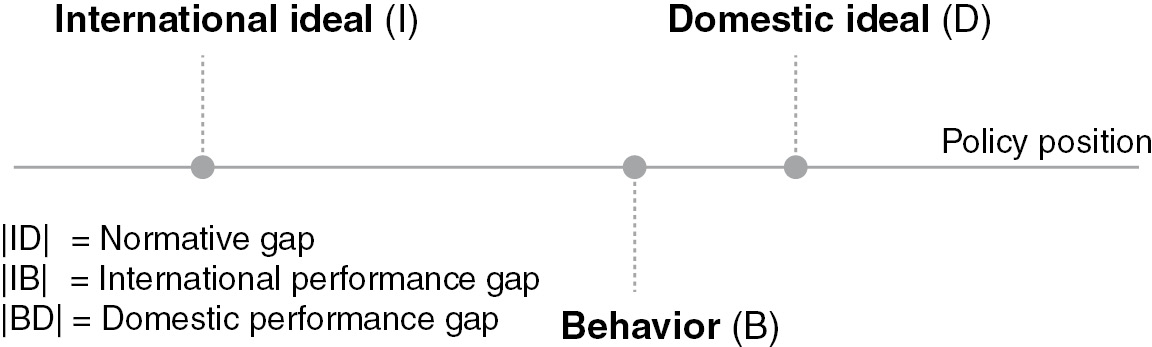

Widely accepted rules or practices that prescribe appropriate or desirable behavior are central to how states and governments assess each other, and how citizens assess their governments.Footnote 22 One can think of reputation in an idealized form. In Figure 2.1, point “I” represents the internationally defined ideal behavior along some spectrum. For example, this could be the degree of freedom of speech, policies to promote gender equality, or per capita carbon emissions. The ideal point could be embedded in an international agreement or in common practices. It could be about policy behavior, but it could also be about behavioral traits, such as generally abiding by the rule of law, or keeping international commitments. The more the global community agrees on and adheres to the ideal standards, the greater their weight and the more these standards act as prerequisites for international legitimacy.Footnote 23

Based on Figure 2.1, a country’s international reputation is the way the international community at large assesses the gap between ideal point “I” and the state’s actual behavior, “B.” The smaller the gap, the better the reputation. Countries have a “good” reputation when they approximate “I.” In reality of course, “I” might be more or less well established, and the understanding of “B” may vary with the level and quality of information, but the idea is that the international reputation is the assessment of the gap by international audiences, and this assessment is more favorable the smaller the gap.

Importantly, however, this reputation may or may not be the same as the one the government has at home. If the state subscribes to different ideals than the international community, domestic audiences may assess the state’s behavior differently. For example, in some countries a widespread acceptance of female circumcision differs from the more widely held international taboos. In Figure 2.1, “D” represents the domestic ideal point. If the international norms conflict with more locally held norms, then “I” and “D” will be far apart and the state may have a different reputation at home than abroad because of the assessment of the gap between the domestic ideal point and behavior differs.

This can place a government in a conundrum. Internationally it is concerned about the gap between its behavior and the international idea, |IB|, while domestically it is concerned about |BD|, the domestic performance gap. Naturally, “D” could also lie between “I” and “B,” in which case the direction of the gap is the same, representing less of a dilemma, but still leading to differential pressure domestically and internationally. Or “D” and “I” could coincide, in which case international criticisms ring true at home. In either case, reputations form relative to existing ideal points and behavior. Because there can only be one behavior, differing ideal points may pull government policies in opposite directions.

Importantly, ideal points need not be fixed. The very act of invoking certain ideals can be an exercise not only in rule enforcement but also in standard setting. That is, those assessing performance are simultaneously shaping the interpretation of what is acceptable performance. In this way, invoking norms is also an act of influencing the very definition of these standards and norms.Footnote 24 Invoking the norms and calling for their implementation can help institutionalize the norms and standards.Footnote 25 Indeed, information is powerful because it promotes accountability, but also because the producers of the information and assessments influence the definition and salience of ideas.Footnote 26

Multiple Reputations Across Issues

In accordance with this broader definition, countries not only have multiple reputations across different audiences, but also across different issues or traits.Footnote 27 For example, countries that stimulate positive economic growth, lead humanitarian rescue efforts, or advance international peace talks may earn a good reputation in the view of those who favor such policies. Conversely, countries that monopolize domestic markets, confiscate private property, or slash and burn its virgin forests might earn a poor reputation in view of those opposed to such practices. Generally, huge environmental disasters tarnish a government’s reputation as a competent and responsible caretaker. The selling of arms to human rights abusers brands a government as opportunistic in the eyes of most. Conduct in trade and war will brand a government’s reputation for credibility and resolve.

While states have multiple reputations, they also accumulate a general reputation based on their performance across many issues ranging from the provision of services and the stewardship of resources to various international matters. As others have noted, “to say that a state has a particular reputation implies that most observers hold the relevant belief about the state.”Footnote 28 In this sense, states may “acquire reputations as law-abiding global citizens.”Footnote 29

Importantly for whether countries are concerned about their reputation in a given issue area, many issues cannot be compartmentalized. If countries repeatedly disregard negative externalities they impose on their neighbors in different areas, for example, other states may worry that poor consideration for neighbors is a general quality.Footnote 30 In an age when states are considering much broader approaches to “human security,” this is increasingly true. Thus, the potential for spillovers remains for most issue areas. This means that a state’s overall reputation can be damaged by a poor performance in any issue area that reveals a fundamental disregard for qualities of broader universal values.Footnote 31 This can be true even if the issue area itself is rather narrow. For example, in 2005 when Mugabe razed local slums in “Operation Murambatsvina,” his reputation suffered generally, not only on the issue of local housing, or even human rights more generally, but also on his governance more broadly. He was widely seen as ruthless and power-obsessed and his state as edging ever closer to pariah status, as noted by a condemning report from the United Nations.Footnote 32 Just like bad news tends to dominate the media, so government failures that attract considerable attention tend to dominate their reputations. States therefore have reason to be concerned about their reputation in any given issue area that threatens to attract public attention.

Furthermore, as opposed to a purely credibility-based conceptualization of reputation, a broader performance and image-based conceptualization sees human rights as central, because it involves moral responsibility and justice, which are the fundamental building blocks of state “character.” Maintaining legitimacy requires states to conform to the international community’s minimal justice requirement.Footnote 33 Because of the substantive international support for human rights norms, countries that violate human rights struggle to maintain legitimacy.Footnote 34 Thus, states may value having a compliant reputation in areas such as human rights that undergird their overall character.

Why Care? The Value of a Good Reputation

A narrow definition of reputation stresses that states value their reputation because they want to gain from cooperation or be able to make credible threats in wartime. In the context of the latter one might allow that some leaders actually value a reputation for unpredictability, ruthlessness, and so forth. That is, some leaders might prefer a bad reputation – they actually wish for their behavior to be assessed as far from the international ideal point.

That said, a broader definition also stresses that governments and citizens value their reputation as part of their state’s identity or image, similar to how a citizen may desire to be viewed as law-abiding.Footnote 35 If states have a good reputation – if others assess their behavior as aligned with international ideals – this gives states and their governments a sense of belonging, facilitates cooperation with other states, and allows them to consider themselves as upright members of the international community.Footnote 36 A positive reputation can be a policy goal in itself, not merely a means to an end.Footnote 37 Indeed, at times states may value their reputation so highly that they are willing to forego other immediate or more concrete gains.Footnote 38

That states and elites care about their reputation in terms of image and broader legitimacy does not imply that states are not instrumental or strategic. States may adopt certain norms and behaviors to reap social benefits and avoid social costs; in this sense, they respond rationally to social incentives.Footnote 39 A good reputation can confer respect and influence, which enables states to accomplish other goals.Footnote 40 Thus, for states, concern about their image “is always in the national interest.”Footnote 41 In other words, a good reputation is just plain useful.

Favorable reputations boost states’ legitimacy, both internationally and domestically. “International legitimacy” is coveted because it is foundational to the state and international society and underscores the right to govern.Footnote 42 Even strong states and their leaders seek international recognition and may assign value to upholding norms that are widely accepted in the international community – a point that some have argued explains why many states joined in sanctions against South African apartheid.Footnote 43 The US, for example, has worried about anti-Americanism worldwide and has sought to manage its international reputation.Footnote 44

A favorable overall reputation is also useful domestically.Footnote 45 Citizens assess their states both for their procedural legitimacy and for the outcomes they produce. It is procedural reasons that have compelled states to invite international monitors to verify the legitimacy of electoral processes.Footnote 46 If citizens perceive their government as corrupt or irresponsible, they may lower their support for the government.Footnote 47 States and their elites may fear economic repercussions or worry about their own political survival.Footnote 48 Although most violations of international norms won’t topple the government, cumulative misconduct can erode its reputation over time. For example, the revelation of human rights violations by the US military in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq brought protests at home and undercut support for the president. Thus, governments need good reputations to maintain domestic support.

Although some dictators may seek to inspire fear by deviating from international norms, support is important for all regime types. Even authoritarian governments experience pressures to perform and are vulnerable to external criticisms, which is one reason so many of them hold “elections” and invite international election monitors to gain some sheen of legitimacy.Footnote 49 Indeed, because authoritarian states compromise on procedural legitimacy, some governments, such as Singapore and China, rely on a reputation of being able to deliver certain policy outputs to sustain their legitimacy.Footnote 50 For example, Singapore prides itself on its top placement in the Heritage Foundation’s Economic Freedom Index as a form of validation, which is why the government has worked so hard to maintain the top spot for decades and brags about it.Footnote 51 Indeed, some research has found that authoritarian states are more susceptible to public exposure of human rights violations than are democracies.Footnote 52 Naturally, authoritarian regimes may compare themselves with different “reference” states, but the principle remains if for some issues they wish to be viewed favorably by a peer group or by domestic constituents.

In addition to the benefits of domestic and international legitimacy, a good reputation also boosts status and standing in the international community. A state’s status refers to its position relative to a comparison group,Footnote 53 and denotes a more hierarchical structure of state relations. Higher social status and prestige are valuable as means to boost recognition and influence in international society or to attract investment or other benefits.Footnote 54

Although the discussion here has mostly focused on states and their governments, individual leaders and elites also have reasons to worry about their personal reputation. Most want to be respected by their citizens and leaders of other states with which they identify.Footnote 55 They want their country to compare well with other countries and they shun “the stigma of backwardness.”Footnote 56 Not withstanding those who actually desire a negative reputation for unpredictability or toughness, if leaders are sensitive to the international status markers of their state or to domestic legitimacy concerns, these might activate psychological desires for a positive self-image and for social approval.Footnote 57 Enhanced status has psychological benefits and elites may value these as part of their identity and fear being ostracized.Footnote 58 Johnston argues, “The most important microprocess of social influence … is the desire to maximize status, honor, prestige – diffuse reputation or image – and the desire to avoid a loss of status, shaming, or humiliation and other social sanctions.”Footnote 59

Thus, states and their elites may value their broader reputation for instrumental reasons and “strategically [adopt] popular policies out of social concern for their international reputations rather than out of any existing practice or norm internalization.”Footnote 60 This also means that governments or officials do not need to be persuaded or have internalized the norms and standards; all that matters is that they believe that others will view them as failing with respect to these norms, that others ascribe validity to these.Footnote 61 Political elites may become “trapped” by the prevailing rhetoric, unable to “craft a socially sustainable rebuttal,” and therefore “compelled to endorse a stance they would otherwise reject.”Footnote 62

In sum, states and their elites may care about their reputation for both normative and instrumental reasons. Such motivations are often both compatible and indistinguishable, depending on how one defines costs and benefits.Footnote 63 They likely operate in concert, either because individual policymakers respond to a combination of these, or because different policymakers in the same country respond differently. In either case, the values states place on their reputations are likely heterogeneous.Footnote 64 Indeed, the sources of concern may not fit as neatly into theoretical boxes as one might suppose. For example, do elites worry about possible consequences like sanctions because they fear losing the funding, or because sanctions are shameful? Some research suggests that sanctions can be used symbolically to influence states, and Arab states have done so at times.Footnote 65 Minor sanctions might be financially bearable; yet the stigma might be unacceptable. Similarly, cognitive dissonance may not just be about emotional stability; individuals may be concerned that others will spot and punish their hypocrisy.

For some reason, however, even scholars who acknowledge that intrinsic and instrumental logics are intertwined default to the instrumental logic and argue “what is at issue is the extent to which these mechanisms lead behavior to deviate from the ideal instrumental policy.”Footnote 66 The burden is always to show that something is not instrumental. From a policy perspective, however, what is at stake is when behavior deviates from norms.

Although these sources of concern can’t all be disentangled, this book will argue and document that reputational concerns are not limited to immediate credibility-based, material repercussions; they are also social and image-based in the sense that states care about being seen as in conformance with the norms in the society of states. This is important for scorecard diplomacy because it means that reputation can be elicited as a tool of influence with or without material leverage, and that it can be elicited across a broad range of issues, not only – as argued by others – “most in security and trade.”Footnote 67

When Do Reputational Concerns Operate? A Simple Model

When do broad reputational concerns arise and translate into policy? The answer to this question may vary with the nature of the issue. Conflict-focused research argues that reputational concerns vary with cultural values such as honor and standing and with the number and type of separatist movements or other challengers.Footnote 68 But reputations on war and resolve can often be identified with singular decisions that are likely attached to individual leaders and entail direct interstate interaction, as is also the case in international lending and repayment, for example.Footnote 69 This contrasts with issues such as human rights or environmental performance, which are more diffuse and focus on broader policies, performance, and implementation over time that often involves many actors. Here I present a simple model of three factors that the arguments above suggest will interact to generate reputational concerns on such broader issues and whether these then produce behavioral changes. These factors are sensitivity and exposure, which together drive the level of concern, and prioritization, which drives the translation of concern into policies, as discussed below.

Sensitivity

Reputational concerns depend on how sensitive a government is to any reputational pressures. Sensitivity depends on the salience of the possible practical stakes of low performance, both for states and political elites, as well how much the government sees itself as being in conflict with existing norms and expectations.

One source of sensitivity is what one might call instrumental salience: to the extent that reputational concerns are connected to the desire to obtain certain goals, their activation will depend partly on the salience of such goals. These are usually some form of international benefit such as aid, trade, tourism, and office holding in international institutions, or membership in international institutions. For example, when countries want cooperation from the international community, they seek external legitimacy more, as evident when Mexico was negotiating for the North American Free Trade Agreement and President Carlos Salinas was campaigning for the World Trade Organization presidency.Footnote 70 Thus, when such benefits are more salient, states will be more sensitive to the reputational damage that can block access to these benefits.Footnote 71

The extent to which individual elites face consequences may also vary. The more likely officials are to be held directly responsible for poor performance, they more likely they will be to worry about their personal careers. Policymakers may also worry that they or their party might be blamed for underperforming. Bureaucrats may worry about being singled out for inaction or mishandling.Footnote 72 Officials may worry about such practical consequences, even if citizens are not protesting. Rather, they may worry simply if they anticipate criticism.Footnote 73 If they fear that bad publicity can produce protest or lower their public approval ratings or job evaluation, they will be more sensitive.Footnote 74

Complementing instrumental salience, states will also be more sensitive to reputation if the underlying norms are salient. The normative salience depends foremost on how well established the international norms are. Norms encoded in legally binding treaties that most states have signed will be most compelling, whereas the least compelling will be those where considerable contestation remains. Some “norms” are not so much moral in character as ideological. For example, the international community is less likely to have consensus on business regulations than on torture. Even if a norm or expectation is well established, the normative salience of a given state also depends on whether the state and governmental elites identify with these. Certain countries may be comfortable deviating from some norms, even if they are well accepted internationally. For example, some countries may have different views on women’s rights that the state justifies based on religious grounds. Finally, the normative salience will depend on the extent to which actual behavior diverges from expectations. To return to Figure 2.1, the salience of norms depends on the gap between the domestic and international ideal points, and greater discrepancy between these and actual behavior stokes reputational concerns.

Public international commitments can be important in this context. If a state has committed to an international treaty that embodies a set of norms, its declared ideal point is close international norms that outside actors might invoke.Footnote 75 This makes the discrepancy between performance and the standards more damaging. On the other hand, if domestic norms differ markedly from international ones, the state will not be as harmed, at least domestically, for failing to live up to standards to which it does not subscribe. This decreases the sensitivity to reputational concerns.

This may lead one to conclude that democratic states are more likely to worry about their reputations because their domestic ideal is likely closer to the international ideal, or because citizens can protest more easily. However, this may vary across issue areas. Domestic ideal points can align well with international ideal points, even in autocracies. This may be especially true if the issue concerns state competencies to deliver services and protect its citizens, to which citizens of autocracies may feel as entitled or with which autocracies may mollify its citizens, a point that aligns well with Huntington’s notion of “negative legitimacy.” Pollution, for example, has become a huge domestic liability issue for China, around which domestic protests have festered. On the other hand, even democracies may veer from international norms. For example, while Australia has been criticized by the international community for its policy to turn back refugees at sea, the mood at home is one of agreement: many people do not want the large influx of refugees and the government has successfully stoked this sentiment to avoid domestic reputational damage for its non-compliance with international norms.Footnote 76

Normative salience also depends on the relationships between the target and the source of the norms. Because reputation is about legitimacy and identity, criticisms from a desired in-group carry more weight.Footnote 77 If states see themselves as having a certain identity, then they are sensitive to status markers from others who share this identity.Footnote 78 Thus, reputational concerns are likely greater when affinity to the actors eliciting the concerns is greater. Relatedly, because reputational concerns arise when information discredits performance, the authority of the source is important. Those advancing norms must be credible and trustworthy and must exemplify the norms they promote, which imbues them with what some call “normative power” to shape conceptions of norms.Footnote 79 The same might be true if the country has strained political relations with the source, in which case it’s easier to dismiss the criticisms as politically motivated. That noted, active efforts to discredit the source signal concern about reputational damage, underscoring the presence and weight of such concerns.

Finally, it may matter how good a country’s overall reputation is. For example, Norway is able to deviate from the international consensus on whaling without too much damage, because it has a lot of “reputational capital” to draw on. It is well regarded and can afford a light dent in its reputation on this issue. Still, reputations, particularly on issues like debt repayment or peacefulness, can easily be squandered, especially if they are accompanied by leadership changes so that others might infer that a structural change has occurred.Footnote 80

Exposure

Reputational concerns depend not only on how sensitive states are on the issue, but also on the availability and clarity of information and on the exposure that the relevant information brings about. The public element is crucial – reputation depends critically on “the extent to which a behavior is publicly observed.”Footnote 81 States may be missing the mark but suffer no reputational consequences if nobody knows about it. Clear information is essential for domestic and international actors to evaluate performance and pressure governments.Footnote 82 Exposure is the degree to which a country’s behavior, “B,” is actively brought into question. Exposure depends on the abundance and clarity of the information as well as on the attention by third parties and the media and focal events.

Active third parties such as NGOs or IGOs can bring attention to the issue in the media and in public discussion.Footnote 83 A large literature stresses the role of civil society in holding domestic governments accountable. Domestic interest groups may care about the international norms referenced and pressure governments to comply.Footnote 84 Societies with active civil societies may therefore be more susceptive to reputational concerns.Footnote 85

Similarly, large events in a country that focus attention on an issue might also increase the exposure of government officials to the criticisms and heighten the costs of inaction. Media play a particularly critical role. Even the threat of bad publicity may worry officials.Footnote 86 Underperformance or scandals can attract outsized attention.

Finally, if the source is unreliable or inconsistent, exposure will be diminished, and governments can dismiss criticism more easily and therefore lessen any reputational damage.Footnote 87

Prioritization

When states are sensitive and their performance exposed, they are likely to worry about their reputations. But whether these concerns translate into action depends on their prioritization. Even if a government is concerned about its reputation on a given issue, it may not be able to pay attention or change its behavior. Like others, government officials have limited capacity for attention and action. Agenda-setting theory suggests that when the agenda is crowded with high priority items – for example, all-consuming crime or drug problems as in Honduras – it’s harder to generate attention for other issues.Footnote 88

Furthermore, the individual agency of elites may influence prioritization. Elites may incur personal costs to change. Local issue champions who can act as “sympathetic interlocutors” can help rally domestic reformers and channel the exchange of information and ideas, but if they are absent or irregular, this can stifle progress.Footnote 89 If reforms could interfere with practices from which officials benefit, such as official corruption, opposition will be high, so even if reputational concerns are present, they may be squashed by such corruption. On the other hand, reform-minded elites – be they bureaucrats, government officials, or opposition politicians – can boost attention to the issue and any international criticisms to highlight the reputational concerns within the country. The more such bureaucrats worry and are in a position to make things happen in government, the more their concern matters, as has been pointed out by the literature on the importance of reform-minded teams within countries.Footnote 90

A country’s ability to address an issue will also be affected by its stability: distraction by internal or international wars or uprisings, or political turmoil, can undermine the attention of any government to address less pressing issues. Political instability may also undermine the personal stakes of elites who face uncertain futures and thus may be less motivated to advance their course. When time horizons shrink, investments in reputations are likely to be less valued.

Capacity is also crucial. Even if reputational concerns bring an issue on the agenda, lack of capacity to design or implement change can end good intentions. Such capacity-deficits are known to hamper international reform efforts as well as compliance with international human rights and environmental treaties.Footnote 91

Figure 2.2 illustrates how sensitivity and exposure influence reputational concerns, and how prioritization mediates whether these concerns translate into action.

How Does Scorecard Diplomacy Elicit Reputational Concerns?

Scorecard diplomacy shares some traits with international institutions, which embody norms and expectations and often provide mechanisms for information sharing.Footnote 92 Through these interactions, institutions can stoke reputational concerns.Footnote 93 Scorecard diplomacy operates as a type of quasi-institution that promotes information sharing and accountability, and facilitates comparisons of state performance. Like international institutions, scorecard diplomacy can set norms and expectations and provide transparency between citizens and their governments, as well as relative status markers between states. New information, such as indicators or rating and rankings, alters the base that actors use to assess performance.Footnote 94 Since scorecard diplomacy often evaluates states’ performance or criticizes governments, it is well suited to elicit reactions from civil society, media and the international community.

As discussed in the introduction, the scorecard diplomacy cycle incorporates several practical features: monitoring and grading, diplomacy and practical assistance, and third party pressures. The next section discusses how these tap into and elicit concerns about reputation.

The Role of Monitoring and Grading

Scorecard diplomacy engages reputations by using public monitoring and assessment. Importantly, it strategically packages and distributes information in a way that invokes relevant norms, and invites comparisons and judgment. It holds states to some behavior that is simultaneously promoted as ideal.

The grades are crucial. Scorecard diplomacy literally assigns periodic, and highly comparable, performance scores. The scores seek to boil down the distance between the international ideal point, “I,” and the state behavior, “B,” down to a grade. They thus become a direct representation of the reputational gab. Numbers, as often used for scorecard diplomacy, are frequently treated as authoritative and lodge themselves in people’s minds.Footnote 95 Because grades are easily understood representations of government performance and the gap with international standards, politicians may worry that a bad rating can lower their citizens’ confidence in their government’s legitimacy and thus its ability or right to rule.Footnote 96 Conversely, if a government suffers from poor legitimacy at home, positive international rankings can be a sign of “good housekeeping, which will add luster to the moral and political credentials” of the government’s reform efforts, as the chief of staff of the Philippine president said in 2009 about the MCC eligibility criteria.Footnote 97

Grades, ratings, and rankings are potent symbols that shape perceptions about performance. By reducing complexity they designate a preferred interpretation as meaningful. Symbols such as grades are powerful, because, as sociologist Beaulieu argued, humans are engaged in “symbolic struggles over the perception of the social world” and they exercise power by trying “to transform categories of perception and appreciation of the social world, the cognitive and evaluative structures through which it is constructed.”Footnote 98 Thus, the use of symbols such as grades to name and label is a political effort to shape perceptions of reality and powerful actors can use such symbols to impose their perspectives.Footnote 99 By categorizing, grades thus socially construct reference points for normative standards of appropriate conduct and encourage others to gauge state behavior against the reference norms. In this way, grades can stimulate the reputational concerns of states and shape perceptions of interest.Footnote 100

In addition to their symbolism, their comparative nature makes grades particularly well suited to elicit reputational concerns. Comparisons can shape and reinforce social identities.Footnote 101 States want to belong to a community, but they also seek to place as high as possible in a social hierarchy, which is why rankings are particularly status-oriented.Footnote 102 Thus, states are not only concerned with how they are viewed by other states, but also how they compare to other states. Grades can introduce a competitive element. When states are grouped they can compare themselves with others – a fundamental status exercise. Citizens may not understand the issue, but they understand that their country has been grouped with pariah countries, or has been put on a blacklist of sorts, or is performing worse than similar countries. Thus, by putting the “scores” front and center, scorecard diplomacy engages exactly the kind of out-group feeling that is foundational to theories of shaming.Footnote 103 Grades thus allow governments to reference their state’s standing within a certain category of states.Footnote 104 States might worry about their peer group for various reasons. For example, investors or other actors may use a country’s perceived peer groups to make decisions about investment.Footnote 105 Grades therefore allow comparisons that stimulate reputational concerns.

Furthermore, the recurrent nature of scorecard diplomacy – assessments are usually issued annually – reveals whether countries are on the right trajectory or whether performance is deteriorating. This iteration engages the country’s reputation both relative to others and to itself over time. Crucially, iteration activates anticipation. A country never actually has to be rated poorly to experience concerns about reputation; countries respond to the anticipation of another round of rating or ranking. Thus, similar to a straight “A” student concerned not to get a “B,” scorecard diplomacy can stimulate status maintenance behavior: once a country achieves a good rating, it wants to maintain it.Footnote 106 For example, when she was told in February 2005 that failure to pass an anti-TIP law could affect Ghana’s Tier 1 status, Ghana’s Minister of Women and Children Affairs exclaimed, “[W]e must keep Tier 1.”Footnote 107 Reiterative and public monitoring and grading is thus a form of systematic “deployment of normative information,” which creates an environment of continuous accountability.Footnote 108

Finally, the monitoring aspect is important. Monitoring signals social importance.Footnote 109 The philosopher Michel Foucault famously characterized monitoring as a form of control and thus power.Footnote 110 Research has also identified the famous “Hawthorne effect,” when individuals change their behavior in response to being aware of being observed, akin to what sociologists call reflectivity.Footnote 111 Election monitoring, for example, can improve the conduct of elections without any formal sanctions.Footnote 112

In sum, monitoring and grading have unique abilities to elicit reputational concerns.

The Role of Diplomacy

While ratings and rankings schemes differ in their degree of interaction with the targets, a fundamental feature of scorecard diplomacy is its engagement on the ground. Scorecard diplomacy takes advantage of the fact that the initial grading increases concerns, which makes policymakers more receptive to other efforts. The second step in the scorecard diplomacy cycle is therefore the ongoing diplomacy and practical assistance. Diplomacy can increase reputational concerns, because it gives international actors a chance to share information, to educate local elites, and to underscore the importance of the international norms. The reporting and meetings launch conversations with policymakers about how to define and frame the problem.

Individual level interaction is important. Even Morgenthau recognized the value of interacting with responsible officials who can be identified and held accountable.Footnote 113 As discussed earlier, drivers of reputational concerns such as the desire to belong to the in-group or fear of opprobrium operate foremost at the individual level. More recently political scientists have emphasized the interpersonal elements of social influence and socialization.Footnote 114 Borrowing from the neuropsychology, a study of face-to-face diplomacy suggests it may stimulate unique neurocognitive processes, because “[d]uring face-to-face interaction we move from private to shared experiences.”Footnote 115 This also aligns with literature in social psychology and sociology, which argues that shame, in particular, is felt in face-to-face encounters, leading people to avoid potentially embarrassing encounters.Footnote 116

New information shared in meetings and reports can influence policymakers’ causal beliefs about the roots of the problem or their understanding of its scope or possible solutions.Footnote 117 This can lessen the gap between the international and the domestic ideal point and thus increase the normative salience of outside criticisms.Footnote 118 The provision of new data and statistics can motivate states to act when they learn the scope of a problem, something that occurred in connection with the campaign against landmines.Footnote 119 Scorecard diplomacy may also shape views by requesting information from the domestic government. Research has found that engaging individuals directly in active data collection, processing, and dissemination can shape their cognitive framework,Footnote 120 in effect priming the international norms in local minds and thus increasing attention to performance on those norms. If elites change their beliefs and internalize new ones, that can be considered a form of socialization.Footnote 121 That said, beliefs are difficult to observe, and in any case not necessary for the dynamic to operate. Policymakers may simply realize that others view the issue as important and seek to behave more appropriately. This essentially moves the domestic ideal point “D” closer to the international ideal point “I,” which may increase reputational concerns as the gap between “I” and behavior “B” then grows.

Policymakers are particularly likely to seek information about policy alternatives because these often require detailed knowledge.Footnote 122 Policymakers surveyed about their attention to performance assessments mention such information as far more influential than financial incentives.Footnote 123 The availability heuristic also suggests that policymakers are more likely to adopt solutions that are placed on their radar.Footnote 124 This is perhaps why studies of diffusion have shown that countries often look to similar countries when designing and advocating for new policies at home.Footnote 125 Thus, diplomatic interaction that highlights policy solutions can increase attention to the problem and make policymakers more receptive to proposed solutions.

Diplomatic interaction and repeated requests for information may also stimulate new bureaucratic structures or habits that institutionalize attention to the issue area and facilitate ongoing learning about the problem and possible solutions. New administrative structures, in turn, can transform the capabilities of the states and foster bureaucratic expertise.Footnote 126 This matters, because new institutions can routinize behaviors and change domestic norms. Max Weber argued that habituation was an important mechanism for shaping behavior.Footnote 127 More common behaviors can become routinized because bureaucrats and politicians are “habit-driven actors.”Footnote 128

In sum, the individual diplomacy calls attention to the issue and shapes local views and ideal points. The more this occurs, the more concerned elites become with the issue and their related reputation.

The Role of Practical Assistance

Not all ratings and rankings are connected to extensive assistance, but those that are will be more likely to work. By funding the government or NGOs or IGOs, scorecard diplomacy can contribute to structures that might shape local norms and practices and thereby increase reputational pressures to live up to those standards. Funding for capacity building or training may introduce new solutions to problems and normalize certain behaviors. Even if the assistance itself may not be effective, it can empower recipients and broaden the set of voices that participate in the national discussion.Footnote 129 Diplomacy and assistance extend attention to the issue far beyond the peak attention it might receive surrounding the release of the report itself and provide ongoing opportunities for interaction, institution building and information transfers.Footnote 130 Thus, while structures are often thought to prevent change,Footnote 131 new exogenously introduced structures can explain change in local norms and practices.Footnote 132

Practical assistance or aid can also increase the instrumental salience of the grades. If ratings or rankings are linked to aid or other economic advantages, this resembles standard uses of conditionality or sanctions. Because a strong country like the US can obstruct the flow of economic benefits to other countries, elites may fear economic fallout for their country. The linkage of the Special 301 Report and US trade, for example, generated concerns about costs to trade with the US.Footnote 133 That said, scholars have long questioned the efficacy of direct economic leverage in achieving policy changesFootnote 134 and criticized them as impracticable and harmful.Footnote 135 Some successes nonetheless exist: Sanctions were widely credited with reforms in South Africa, some research has found that economic pressure can destabilize leaders, the European Union (EU) was able to incentivize reforms in candidate states by linking them to membership, and the US inclusion of human rights clauses in preferential trade agreements has been effective.Footnote 136 More recent work finds that ex post performance-based incentives such as the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s (MCC) use of performance indicators to award aid can induce reforms, although this so-called MCC effect may wear off over time if the conditionality is implemented inconsistently – a lesson that might well also apply to scorecard diplomacy more generally.Footnote 137 Thus, targeted economic pressure that credibly links policies with economic consequences should matter.Footnote 138

Because the assessments are repeated they may also produce anticipatory effects similar to the “hidden hand” of sanctions: the very threat of punishment may lead to efforts to avoid them.Footnote 139 If the rating is linked to punishments or rewards then the recurrent assessments represent an ever-present possibility of economic consequences. Even well performing countries fear the potential consequences of downgrades, a dynamic that has been played out in the Special 301 reports with their more concrete trade implication.Footnote 140

Even if the scorecard linkages to aid or trade are not explicit, elites may still worry about economic consequences of a poor reputation in a given area.Footnote 141 This may be true even in the human rights area, where shaming by international NGOs has been linked to lost investment for targeted states.Footnote 142 In Thailand, for example, the business community was concerned that the 2014 Tier 3 rating would harm trade, especially the fishing industry. This continued even after President Obama waived the sanctions threat.Footnote 143

The Role of Third Parties

Scorecards are designed to engage third parties and increase exposure. Because reputation is relative to existing norms and multiple audiences, the attitudes of other parties are important. Third parties can amplify reputational concerns because they reinforce the larger global set of norms and standards. Once scores are public, other actors such as NGOs, IGOs, and the media augment the visibility of the scores and thus increase exposure and subsequent reputational pressure. This can also trigger market pressures of various kinds. Third parties are not necessary to the success of scorecard diplomacy, but they boost the odds.

The media disseminates ratings or tiers easily, which increases the exposure that activates reputational concerns. For example, the media coverage following the US Special 301 reports about intellectual property rights has been described as media hysteria. Ratings are much simpler than narratives,Footnote 144 and thus easier to use as “psychological rules of thumb”Footnote 145 and to present in media stories. Importantly, media coverage can worry policymakers even if citizens don’t take to the streets. Even the anticipation of publicity and negative domestic reactions can pressure government officials.Footnote 146 Research has shown that elites in general pay much more attention to media than the general public, because they believe that the media does, in fact, affect public opinion.Footnote 147 Thus, negative media coverage can create pressure if it creates the expectation of protest or of lowering public approval.Footnote 148 Of course, domestic officials can also use the media to try to save face by rebutting or rejecting the content of the public scorecard. Indeed, it’s noteworthy if domestic elites feel pressured to do so in the first place. Governments are also not always successful at controlling the flow of information, and cannot control the international press, much of which now reaches citizens through the Internet. Thus, media, both international and domestic, can increase the reputational concerns of domestic elites.

IGOs and NGOs can also increase the exposure to scorecard diplomacy. Funding these actors allows them to carry out programs, and boosts their standing within society.Footnote 149 Their programs, in turn, increase attention to the issue and therefore the exposure of the state to any criticisms of its performance. This is the inverse of a tactic scholars have called the “boomerang” effect, in which domestic NGOs unable to pressure their own governments directly can harness the power of outsiders who then pressure the government of those NGOs.Footnote 150 In the case of scorecard diplomacy, NGOs are not necessarily unable to pressure their own governments, that is, it is not limited to unreceptive authoritarian settings. Furthermore, the pressure is initiated internationally in an ongoing – rather than ad hoc – fashion. Still, a similar dynamic can ensue: NGOs can use poor ratings to augment their pressure on their governments.

The reports may also provide NGOs with more specific substance with which to pressure the government. One global survey found that over half of civil society actors agreed they were empowered to advocate for reforms because the Millennium Challenge Corporation tied aid eligibility to measures of policy performance.Footnote 151 NGOs can also use scorecard diplomacy the way they mobilize around international legal commitments by using the commitments to hold officials accountable.Footnote 152 A study of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which declares countries to be in or out of compliance, has found that the EITI “improves the capacity of civil society to hold governments to account, whether governments like it or not.”Footnote 153 Thus NGOs can use scorecard diplomacy reports for information, but also directly for advocacy and to engage in conversations about problems and needs, all of which increases the governments’ exposure to the reputational concerns.

IGOs can also boost scorecard diplomacy. They have long been argued to play important roles in transnational advocacy.Footnote 154 Their work on the ground encourages information exchanges with the creators of scorecard diplomacy: IGOs may become sources for information into the regularized reporting, but they may also become primary consumers – and thus legitimizers – of that information, which increases the weight of the grades in the minds of policymakers. For example, organizations such as the United Nations (UN) and the IOM use the TIP Report as a source of information.Footnote 155

Other actors can also increase the consequences of scorecard diplomacy by incorporating scorecards or performance assessments into their own criteria for actions, as the Millennium Challenge Corporation has done for awarding aid. At other times, the link is more direct, for example, if the creators of scorecards fund other actors to engage in efforts that align with the basic goals. In this way, concerns about funding may increase, thus increasing the instrumental salience and, therefore, concerns about reputation.

Empirical Expectations

About the Production of Scorecard Diplomacy

The arguments in this chapter suggest a multitude of hypotheses and observable implications. On any given issue the actual set of these will vary with the available evidence and the context. In general, however, if scorecard diplomacy operates as proposed, then, in an information-rich environment, we should observe evidence of the conduct of diplomacy and the engagement of third parties. We should see active reporting and monitoring connected with diplomacy at meaningful administrative levels, and we should see media coverage of the reports, and involvement of NGOs and IGOs. NGOs, in particular, should use the report to pressure their governments.

Chapters 3 and 4 examine these behaviors in the context of human trafficking.

About the Verbal Reactions to Scorecard Diplomacy

Furthermore, if scorecard diplomacy generates concern about ratings as argued, then to the extent that it is possible to observe how countries react, we ought to see that those who fare the worst react more often, and in many instances react negatively. In an effort to minimize the normative salience of the criticism, attempts to discredit the creators of the scores might occur. There may also be contestation over the norms if international and domestic ideal points differ. Countries that get more exposure through media coverage, for example, might also react more.

This chapter has also stressed that countries’ reputational concerns are broad, that is, they are both instrumental and normative, and they include concerns about image and standing in the international community. While it may not always be possible to observe, countries might explicitly express such concern about their image or standing, even if they don’t face any aid or trade threats as a result of the score, or they may underscore such concerns by explicitly comparing their scores with those of other countries, especially those they consider peers. If the reference to international norms is important for states, we might also see that those that have publicly committed to the international norms underlying the scores might react more often. On the other hand, if countries worry about ratings because of aid or trade, we might see discussions in reaction to poor grades in particular, and countries whose aid is threatened might react more.

Chapter 5 examines these behaviors in the context of human trafficking.

About the Policy Responses to Scorecard Diplomacy

The goal of scorecard diplomacy, of course, is not just to get states riled up, but to get them to change their behavior, whether that be policies, regulations, programs, or whatever the relevant outcomes are. If states care about monitoring and grading, then we should observe that they respond when they are included in the monitoring scheme, when they get harsher grades, and when they are downgraded in their rating or ranking.

How would one know that these patterns are really due to the scorecard diplomacy? Here one can derive further observable implications. For example, since the ratings are supposed to affect change through concerns about reputation, then it might be possible to observe not only that scores relate to the level and nature of verbal reactions, but also that countries that react are more likely to change their behavior. Furthermore, if states are motivated by the prospect of a rise in their rating, if one has good information, then one might also be able to observe extra efforts by states to accomplish certain goals as the deadline for the next scorecard cycle approaches. Indeed, with very good access to information, one might even be able to observe that officials explicitly state that they are undertaking reforms with the hope of improving their scores.

Chapter 6 explores these behaviors in the context of human trafficking.

About the Factors Modifying the Policy Reactions to Scorecard Diplomacy

Finally, this chapter has presented a simple model for understanding when scorecard diplomacy is more likely to matter. Specifically, policy responses should depend on states’ sensitivity, exposure, and prioritization. Therefore, policy responses should be more likely when states are more sensitive, that is, if the country wants to boost its international image, if its norms align with the international norms, or if it faces economic repercussions of a low score. This sensitivity will be heightened the more credible the scorecard creator is. Policy responses should also be more likely when states are more exposed. That is, when third parties are actively attracting attention to the issue, or when local events bring attention to issues, and when scorecard diplomacy is credibly implemented in a country, giving it greater weight. Finally, states are more likely to change their behavior in response to scorecard diplomacy, the more they are able to prioritize the issue, such as when local officials take the issue on, when the government is stable and crisis free, or when domestic actors do not have large stakes in preventing change.

Chapter 7 examines these behaviors in the context of human trafficking.

Summary

This chapter has defined reputation as used in this book, explained its nature, and discussed why states and their governments value a good reputation. It has offered a simple model to explain the factors that modify whether states become concerned about their reputation on a given issue and whether they actually do something about it. Finally, it has considered how the features of scorecard diplomacy stimulate states’ concern for their reputation.

The argument takes its starting point in the claim that states are not merely concerned about their reputation in terms of the credibility of their threats and promises in keeping commitments or their resolve in war; rather, states care about their reputation about their broader performance across many issues as assessed by multiple audiences. A good reputation is important for states’ image and identity. Governments know that others – citizens, civil society, and other international and domestic actors – assess their performance relative to a set of standards and norms across a number of issues and that this assessment undergirds their legitimacy and status, both of which bolster their ability to govern and interact with other states.

States sustain a good overall reputation when they adhere to norms more broadly and adopt productive policies, yet, in a world of increasing publicity and accountability, their reputation can suffer even when they falter in a narrow area that attracts attention. Governments therefore worry about their reputations across multiple areas and generally prefer to satisfy the norms and ideals promulgated domestically and internationally. A few exceptions notwithstanding, even authoritarian governments have reasons to worry about their performance. Since the procedural foundation for their authority is weak, to suppress revolt they depend even more on successful performance in other areas.

Performance gaps arise when a state veers from established norms and expectations. How concerned a state becomes about this gap depends on several factors that influence its sensitivity and exposure to criticism. Sensitivity describes the weight that governments assign to the performance gap. Such gaps are more salient to a state if those promulgating the standards belong to a group with which it identifies and if the norms or ideals are well established. Nonetheless, if the domestic standards differ markedly, the international gap will be less salient and the state will be less concerned. Likewise, a state is more sensitive to performance gaps that might affect other objectives, for example, if the state is seeking some benefit that’s tied to the specific issue area. Exposure describes how much credible attention the performance gap gets. This depends both on the authority of the sources of criticisms, as well as the volume and quality of information about the government’s performance. Third parties can magnify the exposure.

States’ concern about their reputations gives the international community an opportunity to influence them. The use of scorecard diplomacy and similar efforts can garner attention and highlight the performance of a state over time and relative to peers. The repeated nature of this exercise makes countries concerned about current and future ratings. Its public nature lets other actors reinforce the norms, which increases the government’s reputational concerns. The use of monitoring and grading therefore can raise governments’ concern about their reputations, especially if the efforts are further supplemented by diplomatic engagement.

Whether concern translates into action depends on the priority the government can give it. States have crowded agendas, experience instability, and may lack capacity. Some states may assign a lower relative value to its reputation on a given issue when the domestic agenda is very crowded. Surely, when leaders gas their people, as has Syria’s president Bashar al-Assad, the reputational cost to them is considered tolerable in light of their other objectives. Getting from concern to action thus remains a context-dependent challenge. Nonetheless, without other sure-fire tactics to influence recalcitrant governments, it makes sense to attend to the question of reputation and how to stimulate concerns about performance. In the absence of military or strong coercion, reputational concern is a prerequisite for action, so it’s important to understand how it arises and can be stimulated. This book therefore moves on to examine what we can learn about reputation and scorecard diplomacy from the case of human trafficking.