Introduction

The issue of terrorism: Terrorism, typically driven by ideological, political, or religious motives, involves indiscriminate acts of violence committed by individuals or organized groups, aimed at instilling widespread fear and insecurity (López Calera, Reference López Calera2002). According to the Global Terrorism Index (GTI), published by the Institute for Economics & Peace (2025), terrorism remains a global menace, with 66 countries affected and 7,555 terrorism-related deaths recorded in 2024. While its incidence varies across time and regions, the true impact is considerably greater when including not only the deceased but also injured individuals and the wider circle of affected families and witnesses.

In Europe, terrorist attacks rose from 34 in 2023 to 67 in 2024. The European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT) recorded 58 incidents that year, 34 of which were completed (Europol, 2025). Zooming in on Spain, the country ranks 63rd in the GTI (Institute for Economics & Peace, 2025). Spain has a long and complex history in this regard: By 2011, there were 5,795 documented direct victims and approximately 20,000 when including affected family members (Rodríguez-Uribes, Reference Rodríguez Uribes2013), and although the threat level fluctuates over time, terrorism remains a concern.

These data underscore that terrorism continues to pose a serious challenge globally—including in Spain—and remains a pressing issue requiring sustained attention and adequate resources.

Psychopathological consequences of terrorism in the adult population: While most individuals exposed to terrorist attacks do not develop psychopathology (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Jones, Fox, Copello, Jones and Meiser-Stedman2021; García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021), a significant proportion do, particularly direct victims, followed by indirect victims—especially relatives of those injured or killed (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021). Compared to the general population, terrorism victims show higher rates of emotional distress and psychological disorders (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Gutiérrez2016, Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021; Rigutto et al., Reference Rigutto, Sapara and Agyapong2021).

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is among the most common trauma-related conditions. Approximately 39% of direct victims develop PTSD within the first 6 months after the attack, with a prevalence of 33% between 6 and 12 months (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Gutiérrez2016). In the most recent long-term study involving Spanish victims—at least as far as we know—conducted an average of 21.5 years post-attack, PTSD remained the most prevalent diagnosis among direct victims, with a point prevalence of 35.8% (Gutiérrez, Reference Gutiérrez2016).

Beyond PTSD, direct victims frequently experience other disorders. Depressive disorders affect 20–30%, and anxiety disorders occur in 6–17% (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021). Among Spanish victims, point prevalence rates were 25% for depressive disorders and 51.1% for anxiety disorders (Gutiérrez, Reference Gutiérrez2016).

Relatives of injured or deceased individuals show particularly high PTSD rates among indirect victims: 29% within the first 6 months post-attack and 17% between 6 and 12 months (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Gutiérrez2016, Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021). Similar rates were found among Spanish relatives of people injured or deceased after terrorist attacks: 17.8% and 22.4%, respectively (Gutiérrez, Reference Gutiérrez2016). These individuals also show elevated rates of depression—approximately 40% in general samples (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021; Rigutto et al., Reference Rigutto, Sapara and Agyapong2021), and 15.5% to 21.2% in Spanish long-term data (Gutiérrez, Reference Gutiérrez2016). Data on anxiety in this group are scarce. A systematic review (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021) reported anxiety prevalence rates between 0.7% and 11% among indirect victims, without specifying figures for relatives. Gutiérrez (Reference Gutiérrez2016) is the only study, to our knowledge, providing such information: 37.2% and 44.2% of relatives of injured and deceased victims, respectively, reported anxiety disorders more than two decades after the attacks.

Both direct and indirect victims are at increased risk of chronic psychopathology compared to other trauma populations (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Gutiérrez2016, Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021; Rigutto et al., Reference Rigutto, Sapara and Agyapong2021). Long-term reductions in quality of life have also been observed (Serralta-Colsa et al., Reference Serralta-Colsa, Camarero-Mulas, García-Marín, Martin-Gil, España-Chamorro and Turegano-Fuentes2011; Gutiérrez, Reference Gutiérrez2016). Given the enduring psychological impact and the continued threat of terrorism in many parts of the world, addressing these issues remains a global priority requiring sustained attention and resources.

Psychopathological consequences of terrorism in children and adolescents: Children and adolescents warrant particular attention when examining the psychological consequences of terrorism, as exposure to such events poses a significant risk to their mental health. As in adults, PTSD is the most frequently reported condition in young victims (Arnaiz et al., Reference Arnaiz, Sanz and García-Vera2020). Guffanti et al. (Reference Guffanti, Geronazzo-Alman, Fan, Duarte, Musa and Hoven2016), studying both direct and indirect child victims, reported a PTSD prevalence of approximately 11% 6 months post-attack. Also, a systematic review by Arnaiz et al. (Reference Arnaiz, Sanz and García-Vera2020) estimated an average prevalence of 13% among children exposed to terrorist attacks.

Although PTSD is the most extensively researched outcome, minors may also develop symptoms of anxiety, depression, and acute stress (Kar, Reference Kar2019), with internalizing symptoms generally more common than externalizing ones (Pereda, Reference Pereda2013). However, prevalence data for disorders other than PTSD in this population remain scarce. Munson (Reference Munson2002), for example, identified a range of frequent affective symptoms in children exposed to terrorism, including sadness, social withdrawal, excessive fear of failure or rejection, guilt, interpersonal and academic difficulties, anger, and hostility. In relation to anxiety, Fremont (Reference Fremont2004) highlighted common symptoms such as avoidance behaviors, somatic complaints, irrational fears, sleep disturbances, and tantrums.

Importantly, the psychological impact of terrorism during childhood and adolescence can persist over time and become chronic (Kar, Reference Kar2019; Prieto et al., Reference Prieto, Sanz, García-Vera, Fausor, Morán, Cobos, Gesteira, Navarro and Altungy2021). Exposure at an early age has been associated with up to a sixfold increase in the risk of developing depression in adulthood (Kar, Reference Kar2019).

Factors that influence the development of child and adolescent psychopathology after a terrorist attack: However, living through a terrorist attack or experiencing trauma in general is not the only necessary condition for developing a psychological disorder. There are several risk factors that increase the propensity to develop psychopathology or that influence its emergence after suffering this type of event. According to Comer and Kendall (Reference Comer and Kendall2007), it is necessary to pay attention to how the minors experienced the attack, their personal characteristics, and those of their environment.

Regarding how minors experienced the attack, it has been found that when they were the direct victims, they have a greater risk of developing psychological disorders (Bonde et al., Reference Bonde, Utzon-Frank, Bertelsen, Borritz, Eller, Nordentoft, Olesen, Rod and Rugulies2016; Comer & Kendall, Reference Comer and Kendall2007). Children who were direct victims show higher prevalences of PTSD (59%) than those who were indirect victims (21%) (Arnaiz et al., Reference Arnaiz, Sanz and García-Vera2020). In addition, the fact of suffering intense reactions of fear or a feeling of helplessness and insecurity during the event or very close to it is a determining factor for the development of psychopathology in minors (Comer & Kendall, Reference Comer and Kendall2007).

These reactions can be worsened by the feeling that a loved one is or has been in danger or by the loss of that loved one during the attack. Thus, the risk of suffering from PTSD, depressive disorders, and/or anxiety increases when the minors are direct victims of the attack or when, without being direct victims, they are highly exposed to it (e.g., through the media) but also if a loved one was exposed to the attack (Guffanti et al., Reference Guffanti, Geronazzo-Alman, Fan, Duarte, Musa and Hoven2016; Pfefferbaum et al., Reference Pfefferbaum, Devoe, Stuber, Schiff, Klein and Fairbrother2005; Yahav, Reference Yahav2011).

In addition to the factors most closely related to the terrorist attack, minors’ individual characteristics, such as age and gender, are important. Research suggests that, depending on the age at which the trauma is experienced, the likelihood of suffering from disorders like PTSD could vary. However, studies show contradictory data in this regard. The review of Comer and Kendall (Reference Comer and Kendall2007) describes how younger children, between 4 and 5 years old, present more symptoms after the trauma than children between 6 and 12 years. However, review studies such as that by Arnaiz et al. (Reference Arnaiz, Sanz and García-Vera2020) found that children up to 7 years of age have lower prevalences of PTSD than older children, whereas Prieto et al. (Reference Prieto, Sanz, García-Vera, Fausor, Morán, Cobos, Gesteira, Navarro and Altungy2021) did not observe statistically significant differences in diagnoses among children as a function of age.

Regarding gender, the literature seems to be more consistent, indicating that females have a greater tendency to present post-traumatic stress, anxious, and depressive symptoms after terrorist events than males, regardless of whether they were direct or indirect victims (Comer & Kendall, Reference Comer and Kendall2007; Kar, Reference Kar2019; Munson, Reference Munson2002).

Finally, among the important factors to consider is the context of the child and adolescent population and its importance in developing disorders. Meta-analyses on risk factors for the diagnosis of PTSD in general, such as the one carried out by Brewin et al. (Reference Brewin, Andrews, Valentine, Bromet, Dekel, Green, King, King, Neria, Son and Schultz2000), also indicate that the development of the disorder does not depend only on the degree of exposure to the trauma or the child’s individual characteristics. An important risk factor involves the family and adverse childhood experiences. The adversities derived from maladaptive family functioning seriously affect the children (Brewin et al., Reference Brewin, Andrews, Valentine, Bromet, Dekel, Green, King, King, Neria, Son and Schultz2000; Dorrington et al., Reference Dorrington, Zavos, Ball, McGuffin, Sumathipala, Siribaddana, Rijsdijk, Hatch and Hotopf2019; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Koenen, Bromet, Karam, Liu, Petukhova, Ruscio, Sampson, Stein, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Borges, Demyttenaere, Dinolova, Ferry, Florescu, de Girolamo, Gureje, Kawakami and Kessler2017).

Such maladaptive family functioning is common in families where one of the parents has suffered a trauma or has some psychopathological diagnosis (Essex et al., Reference Essex, Klein, Cho and Kraemer2003; Mardomingo et al., Reference Mardomingo, Mascaraque, Parra, Espinosa and Loro2005; Punamäki et al., Reference Punamäki, Qouta and Peltonen2017). Children of parents with psychopathology have up to 13 times more risk of suffering from mental disorders than those whose parents have no type of diagnosis (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Stevens, Mortensen, Murray, Walsh and Pedersen2010). In addition, past parental trauma is associated with higher levels of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and somatization in their children (Punamäki et al., Reference Punamäki, Qouta and Peltonen2017).

Terrorism—a potentially traumatic event that can produce PTSD and other emotional disorders—can also affect family functioning, causing suffering in children and adolescents that can shape their evolutionary history (Stoddard et al., Reference Stoddard, Gold, Henderson, Merlino, Norwood, Post, Shanfield, Weine and Katz2011). Some studies have found a relationship between parents’ development of PTSD and depression after a terrorist attack and their children’s behavioral problems (Slone & Mann, Reference Slone and Mann2016; Yahav, Reference Yahav2011). In addition, studies of children who were direct victims of terrorist attacks and who developed post-traumatic symptoms have found evidence that parental emotional reactions worsened them (Holt et al., Reference Holt, Jensen, Dyb and Wentzel-Larsen2017).

The impact of parental trauma on the children is so significant that some authors refer to the concept of “family trauma,” expressed as a phenomenon that is inherited from parents to children and that generally increases the children’s vulnerability to suffer severe psychological consequences or disorders even if they themselves have not suffered the trauma (Burchert, Reference Burchert, Stammel and Knaevelsrud2017). This term is related to the so-called historical trauma (Brave Heart-Jordan, Reference Brave Heart-Jordan1995), but the latter occurs in a broader social context, alluding to the entire community. Historical trauma is a collective trauma caused by an event that occurred at a certain past moment and impacted a large group of people, causing a social and even a historical gap, which entails psychic and emotional consequences for the survivors and the subsequent generations (Bohigas et al., Reference Bohigas, Carrillo, Garzón, Ramírez and Rodríguez2015; Brave Heart-Jordan, Reference Brave Heart-Jordan1995).

The presence of family trauma in the scientific literature on the subject is such that, given the role played by the main figures in the care of children and adolescents, the creation of a new diagnostic category, “developmental trauma disorder,” was proposed. It would describe the consequences of early and repeated exposure to trauma (Baita, Reference Baita2012; Spinazzola et al., Reference Spinazzola, van der Kolk and Ford2021), but it is not included in the reference diagnostic manuals.

Previous research has shown that victims of terrorism may differ in certain aspects from victims of other types of traumatic events, particularly in terms of psychopathological outcomes (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Moreno, Sanz, Gutiérrez, Gesteira, Zapardiel and Marotta-Walters2015; Serralta-Colsa et al., Reference Serralta-Colsa, Camarero-Mulas, García-Marín, Martin-Gil, España-Chamorro and Turegano-Fuentes2011). It has also been established that minors are especially vulnerable to traumatic events when these impact the family system (Kar, Reference Kar2019; Yahav, Reference Yahav2011). Furthermore, some studies have explored the short-term influence of parental psychopathology on their children following terrorist attacks or other traumatic events. However, to our knowledge, no study to date has investigated whether this influence persists into the offspring’s adulthood. The present study seeks to address this gap by exploring the long-term psychological effects on individuals who grew up in families affected by terrorism—including those who were children or not yet born at the time of the attack—where parental psychopathology was present. In doing so, this work aims to contribute new insights into the intergenerational impact of terrorism over the long term.

Thus, the purpose of this study is to examine the potential tendency for individuals who were children at the time of the attack—including those who were either minors or not yet born—to develop psychopathology in adulthood, depending on whether their parents developed disorders following exposure to a terrorist attack.

Given that previous research on trauma has identified parental psychopathology as a risk factor for the development of psychopathology in offspring (Essex et al., Reference Essex, Klein, Cho and Kraemer2003; Mardomingo et al., Reference Mardomingo, Mascaraque, Parra, Espinosa and Loro2005; Punamäki et al., Reference Punamäki, Qouta and Peltonen2017), we hypothesize that individuals whose parents developed psychological disorders as a result of a terrorist attack will be more likely to present psychopathological symptoms in adulthood. Furthermore, we expect that such effects will persist over the long term.

Method

Participants

This study is part of a larger one carried out by the “Universidad Complutense de Madrid” in collaboration with the Association of Victims of Terrorism (AVT) of Spain, which monitors and treats victims of terrorism.

To estimate the minimum sample size required to detect statistically significant results with adequate power, the software Epidat 4.2 (Hervada Vidal et al., Reference Hervada Vidal, Naveira Barbeito, Santiago Pérez, Mujica Lengua, Vázquez Fernández, Manrique Hernández, Silva Ayçaguer and Bacallao Gallestey2016) was used. Given the lack of previous studies on the long-term influence of terrorism-related parental psychopathology on their children, reference was made to similar research in other populations, such as Holocaust survivors.

In the study by Yehuda et al. (Reference Yehuda, Bell, Bierer and Schmeidler2008), it was found that 46.3% of adult children whose Holocaust-survivor mothers had developed PTSD presented a mood disorder, corresponding to a significant odds ratio (OR) = 3.06 compared to a control group. Furthermore, when both parents had PTSD, 31.4% of their children developed PTSD themselves, with an estimated OR = 3.21.

Taking these effect sizes as a reference and setting a significance level of (α = .05) and statistical power of (1 − β = .80), the calculations indicated that at least 59 participants per group (case and control) would be required to detect group differences in mood disorders, and 74 and 75 participants, respectively, for detecting differences in PTSD prevalence.

These estimates represent the minimum effect sizes needed to ensure sufficient statistical power, assuming the effect truly exists. While trauma contexts differ, the study by Yehuda et al. (Reference Yehuda, Bell, Bierer and Schmeidler2008) offers a valid precedent for estimating intergenerational risk, as both situations involve significant trauma exposure and long-term psychological consequences.

For this particular study, we used a sample made up of different families. At the time of evaluation, all participants were of legal age and associated with the AVT. Therefore, they had been direct or indirect victims of terrorist attacks, so we considered the wounded, the relatives of the injured, and the relatives of those who died in these attacks.

To recruit the participants, we first contacted 1,587 adults associated with the AVT by telephone. The people contacted were evaluated in two phases: In the first phase, we conducted a telephone interview, aimed at making initial contact with the participants and facilitating a second in-person interview, and the participants completed a series of questionnaires, which included: the Spanish version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, specific version (PCL-S) (Vazquez et al., Reference Vázquez, Pérez-Sales. and Matt2006); the Spanish version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II, short form (BDI-II-SF) (Sanz et al., Reference Sanz, García-Vera, Fortún and Espinosa2005); and the Spanish version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory for Primary Care (BAI-PC), a short form of the BAI (Sanz et al., Reference Sanz, García-Vera and Fortún2012).

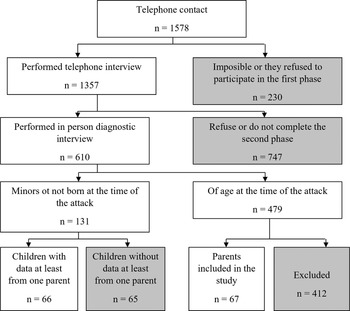

In the second phase, we proposed to perform a structured diagnostic interview in person, specifically the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I Disorders, clinician version (SCID-I-CV; First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1999), to detect possible psychological disorders among the participants (Figure 1). Of the 1,587 people contacted, 1,357 agreed to participate in the first phase, and of them, 601 also underwent the diagnostic interview in person.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the recruitment of the participants.

Participants of the present study were selected from the already general collected data, if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

- Having been a minor or not having been born when the attack occurred.

-

- At least one of their parents had also been interviewed by telephone and in person; therefore, the pertinent information was available.

Regarding the first inclusion criterion, it is important to note that participants who had not yet been born at the time of the attack were included because the focus of the study is not on direct exposure to the event, but rather on the experience of growing up in a family affected by terrorism-related parental psychopathology. This approach enables the assessment of the long-term and intergenerational effects of such trauma. Furthermore, the inclusion of these participants allows for a more comprehensive and representative sample of individuals raised within these impacted family environments.

Of the sample of 601 people, 131 participants were identified who were minors or had not been born at the time of the attack. Of these 131 children, 66 were finally selected, whose parents had participated in both phases of the study evaluation.

Given that this study aims to consider families, it is important to note that the participants were included if there were data from at least one parent. In this way, some people among the 66 participants may have had information about one or both parents. It is also important to note that among these 66 people, some participants were siblings and, therefore, shared the same parents within the sample. Thus, in total, we analyzed the data of 67 parents who, as mentioned, could be parents of one or more of the 66 children that make up the sample.

Despite the sample size estimations, the final sample did not reach the calculated optimal size.

Nonetheless, given the uniqueness and relevance of the population studied, the research was conducted acknowledging the reduced statistical power and with appropriate caution in the interpretation of the results.

Variables and Instruments

Next, the instruments used to collect information on the relevant variables of the study are described, which, in this case, were sociodemographic characteristics, features related to the attack, and the participants’ diagnoses.

Sociodemographic and Attack-Related Variables

This information was collected through a semi-structured interview created specifically for this purpose and based on the general module of the Spanish version of the SCID-I-CV (First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1999) and the interview to evaluate trauma by Foa et al. (Reference Foa, Hembree and Rothbaum2007).

Current and Past DSM-IV-TR Diagnoses (Post-Traumatic Stress, Depressive, and Anxiety Disorders)

This information was collected by administering modules A (on affective episodes) and F (on anxiety disorders and others) of the Spanish version of the SCID-I-CV (First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1999) to the participants.

As the SCID-I-CV (First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1999) is a diagnostic scale, evidence of inter-rater reliability is important. Considering the diagnoses included in the present study (depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and PTSD), we found that the inter-rater reliability for affective disorders ranged from κ = .66 to .81, for anxiety disorders between κ = .60 to .83, and for PTSD, κ = .77 (Lobbestael et al., Reference Lobbestael, Leurgans and Arntz2011). Regarding the interpretation of these indices, all of them reflect good (.61–.80) or very good concordance (.81–1.00) (Altman, Reference Altman1990). Moreover, although limited information is available on the validity of this diagnostic interview, it has been compared to the LEAD procedure (longitudinal expert assessment using all available data; Spitzer, Reference Spitzer1983), showing that it is valid for diagnosing mental disorders according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2002).

Ethical Considerations

Before starting the interviews, the participants were asked to sign the informed consent form so that we could collect and use the data for research purposes, guaranteeing their total anonymity and explaining the study’s objectives. In addition, we informed them that the procedure was voluntary and that they could leave the study if they wished, having the right to access, rectify, and delete their data. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at Universidad Complutense de Madrid (October 10, 2011). The study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Procedure

After the participants agreed to participate, telephone interviews were conducted to gather sociodemographic and clinical data about the attack. Secondly, the structured diagnostic interview (SCID-I-CV; First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1999) was performed in person to make a diagnosis, also following the criteria of the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2002).

Both interviews were administered individually by health psychologists with specific training in the assessment and treatment of victims of terrorism.

Design

The present study uses a nonexperimental or ex post facto design, as there is no manipulation of variables or random assignment because it deals with events that have already occurred. In addition, it is a correlational study that attempts to retrospectively determine a possible relationship between two variables because these variables have already occurred.

Thus, the criterion and the predictor of this study were coded to respond to the research question: Do the children of victims of terrorism who grew up in families where the parents presented psychopathology in the past tend to develop more psychological disorders throughout life?

The study considers a predictor variable with two levels, which, in turn, constitute the comparison groups:

-

1. Being the child of parents with past psychopathology associated with a terrorist attack.

-

2. Being the child of parents without past psychopathology associated with a terrorist attack.

Likewise, the criterion variable was defined by the existence or nonexistence of a clinical diagnosis (PTSD, depressive disorders, and/or anxiety disorders) in the children at the time of the interview.

Statistical Analysis

First, frequency analyses were performed to account for the main sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the parents and the children analyzed in this study.

As the present design has limitations and does not allow for establishing causal relationships, two types of preliminary analyses were performed to interpret the results of the main analysis adequately: (1) confounding variables analyses and (2) a group equivalence analysis.

As stated, preliminary analyses were conducted to identify and control for potential confounding variables that could influence the presence of psychopathology in the children. These variables included: (1) birth status (i.e., whether or not the participant had been born at the time of the attack), (2) type of victim (i.e., whether the participant was injured, a relative of someone injured, or a relative of someone deceased), and (3) sex.

The “birth status” variable was included due to the specific nature of the sample: The study examines long-term effects of growing up in families affected by terrorism. Therefore, it was important to determine whether being born after the attack—but raised in a trauma-impacted environment—had a differential effect on later psychopathology, at least in our sample.

“Type of victim” was considered because, although all participants were children of parents directly affected by terrorism, their or their parents’ level of exposure (injured or deceased) may have influenced the intensity of trauma experienced within the family system. In some cases, children may have also been directly exposed to the attack. Prior research has highlighted the relevance of trauma severity, justifying the inclusion of this variable.

Sex was included as well, given consistent findings of gender-based differences in psychological outcomes following terrorism.

To assess whether these confounders were independently associated with child psychopathology, chi-square analyses were conducted using each of them as independent variables and psychopathology as the dependent variable.

Additionally, given the nonexperimental nature of the study, it was necessary to ensure comparability between the groups of children with and without parental psychopathology. For this purpose, we tested group equivalence across the same variables using Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical data, independent-samples t-tests for continuous data, and the Fisher–Freeman–Halton (FFH) exact test when expected cell counts fell below 5, using SPSS’s Exact Tests module.

The main analysis was then performed, consisting of a Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2), in which the following groups were compared: children of parents with past psychopathology and children of parents without past psychopathology, in terms of the presence and type of current and past psychopathology in the children.

Finally, we calculated the effect size expressed as an OR. This index provides information on the odds that a psychological disorder will occur given exposure to parents suffering from psychopathology, compared to the odds of the psychological disorder occurring in the absence of that exposure, that is, when parents did not suffer from psychopathology.

To interpret the magnitude of the ORs, we followed the cut-off values proposed by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Cohen and Chen2010), where an OR of 1.68 indicates a small effect, 3.47 a medium effect, and 6.71 a large effect. Accordingly, ORs between 1.68 and 3.47 are interpreted as small to medium effects, those between 3.47 and 6.71 as medium to large effects, and ORs of 6.71 or greater as large effects.

All analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 27 program and using a significance criterion of .05.

Results

Sample Description

Regarding the children, the sample was mostly female (59.1%), with a mean age of 32.17 years (SD = 7.25) at the time of the assessment and 5.92 years (SD = 4.98) at the time of the attack. Notably, eight participants had not yet been born when the attacks occurred; however, they were included because the focus of this study is not on direct exposure, but rather on the effects of growing up in a family environment affected by terrorism-related parental psychopathology. Their inclusion also contributes to a more comprehensive and representative sample of individuals raised in such contexts.

Most children were Spanish nationals (89.4%), single (54.5%), and employed (63.6%). On average, diagnostic interviews were conducted 24.87 years (SD = 8.5) after the attacks—primarily carried out by the Basque terrorist group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) (77.3%). The participants were mostly relatives of injured victims (45.5%), followed by relatives of the deceased (39.4%) and direct victims (15.2%).

Regarding psychological support, two-thirds (66.7%) had never received help, and 71.2% were not receiving help at the time of assessment. Among those who had received support, psychological therapy was the most common, both in the past (30.3%) and at the time of the interview (21.2%), followed by pharmacological and other types of support. Some received a combination of treatments.

In the parents’ group (n = 67), 62.7% were women. Their average age at the time of the interview was 58.82 years (SD = 7.86) and 33.29 years (SD = 8.18) at the time of the attack. The majority were Spanish (89.6%), married (64.2%), and involved in domestic tasks (43.3%). On average, 24.08 years (SD = 7.89) had passed between the attack and the interview.

Most parents had been affected by attacks perpetrated by ETA (79.1%). In terms of victim type, 38.8% were direct victims, 31.3% were relatives of the injured, and 29.9% were relatives of the deceased. Over half had received some form of psychological or psychiatric support in the past (50.7%), while at the time of the interview, 56.7% were not receiving any. Pharmacological treatment was the most common form of support, both historically (40.3%) and currently (37.3%).

A summary of the main sociodemographic and trauma-related characteristics of both groups is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and attack-related characteristics of parents and children

Note: NA = not available. †In the case of help (past and current), the different options could be combined.

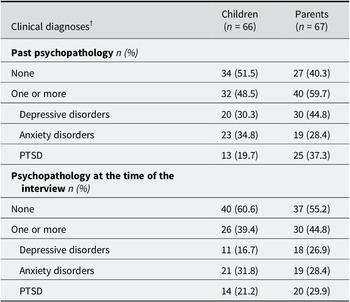

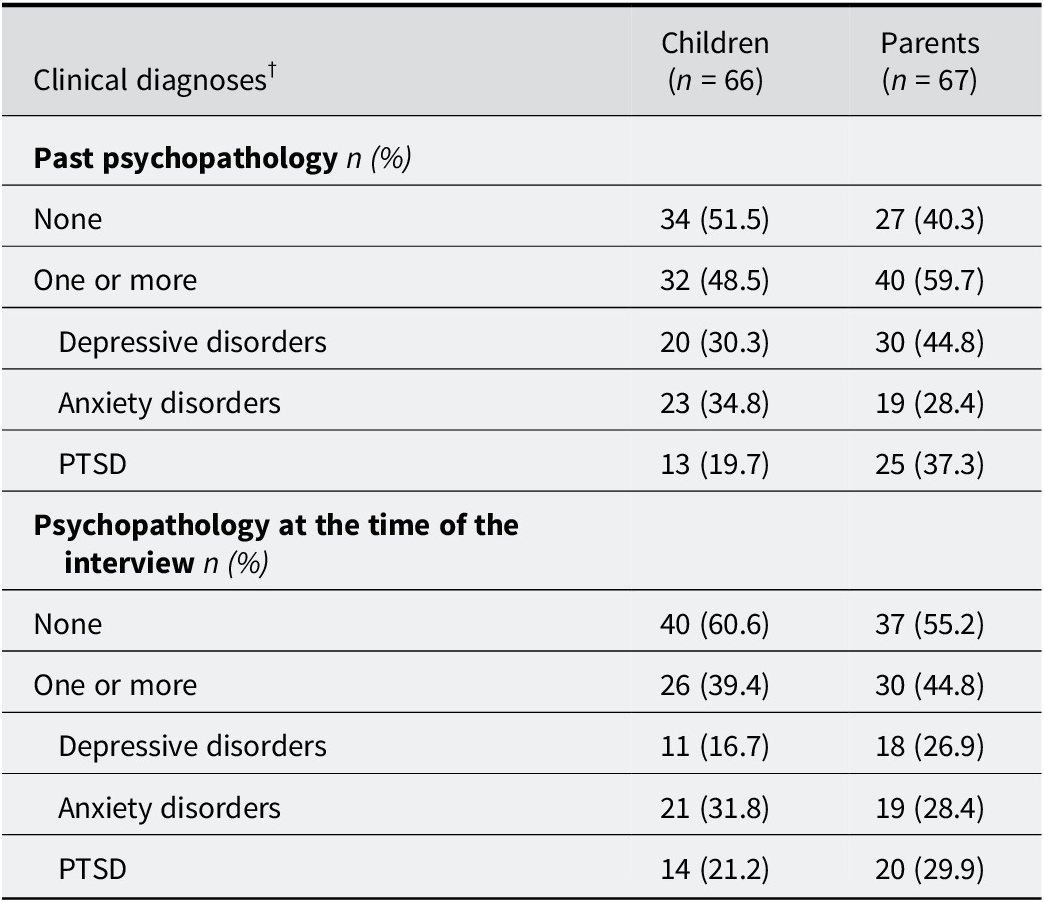

Table 2 presents the clinical profiles of the participants in this study. The diagnostic interview enabled us to assess both current psychopathology and past disorders developed following the attacks. It should be noted that some participants received multiple diagnoses, and comorbidity between disorders was observed in certain cases

Table 2. Past clinical diagnoses and diagnoses at the time of evaluation

Note: † There could be comorbidity between disorders among the participants.

As shown in Table 2, most of the children had no history of mental health disorders (51.5%) and no current diagnosis at the time of assessment (60.6%). However, 48.5% had received at least one diagnosis in the past, and 39.4% met criteria for one or more disorders at the time of the interview. Among these, anxiety disorders were the most frequently reported, both historically (34.8%) and currently (31.8%).

For the parent group, most had received a diagnosis at some point in the past (59.7%), although the majority were not experiencing any disorder at the time of the interview (55.2%). Depressive disorders were the most prevalent historical diagnosis (44.8%), while PTSD emerged as the most common current disorder (29.9%).

Overall, between one-third and one-half of the sample had experienced psychopathology at some point, whether in the past or present. These prevalence figures align with previous findings on populations affected by terrorism (Baldomero et al., Reference Baldomero, Arrate, Pérez-Rodríguez and Baca-García2004; García-Vera & Sanz, Reference García-Vera and Sanz2016; García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Gutiérrez2016, Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021), reinforcing the representativeness of the current sample.

Preliminary Analysis of Confounding Variables

As specified above, we performed preliminary analyses on three variables that could be conditioning the presence or absence of disorders both in the past and the present in the sample of children: having been born or not when the attack took place, the sex, and the type of victim.

Born versus Unborn

The chi-square test results are presented in Table 3. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups—participants who were minors at the time of the attack and those not yet born—regarding past diagnoses (χ2 = 0.008, p = .92, OR = 1.07, 95% CI [0.24, 4.70]) or current diagnoses at the time of assessment (χ2 = 0.429, p = .51, OR = 1.63, 95% CI [0.37, 7.21]). Likewise, no significant differences emerged between groups based on the type of disorder.

Table 3. Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2) according to the presence and type of past or present disorder between born and unborn children

Note: † There could be comorbidity between disorders among the participants. χ2 = chi-square test; df = degrees of freedom; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = confidence interval; LL: lower limit; UL: upper limit.

Therefore, within this sample, psychopathology does not appear to be influenced by whether the participant was born at the time of the attack.

Type of Victim

All children in this study were relatives of direct victims of a terrorist attack; however, their parents may have been injured or killed during the event. Additionally, some children may have been direct victims themselves. Thus, it is important to examine whether present or past psychopathology differs across the groups in this sample—namely, injured children, children of injured parents, and children of deceased parents. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2) according to the kind of past or present disorder among injured people, relatives of the injured and relatives of the deceased

Note: † There could be comorbidity between disorders among the participants. I = injured; RD = relative of the deceased; RI = relative of the injured. χ2 = chi-square test; df = degrees of freedom; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

No statistically significant differences were found in past diagnoses (χ2 = 0.627, p = .84) or current diagnoses at assessment (χ2 = 2.121, p = .34) according to victim type. Similarly, no significant group differences emerged in relation to disorder type.

To report the OR-related findings, the three victim types (injured individuals, relatives of deceased victims, and relatives of injured victims) were compared pairwise. Even though no statistically significant differences were found, a trend in the data suggests that being injured in a terrorist attack is associated with a 1.75 times higher likelihood of having experienced a psychological disorder at some point in life compared to being a relative of a deceased victim, and 1.74 times compared to being a relative of an injured victim (small effect sizes). Similarly, injured victims are 2.83 and 2.59 times more likely to present long-term psychological disorders than relatives of injured and deceased victims, respectively (small to moderate effect sizes). Regarding specific diagnoses, individuals injured in a terrorist attack are 3.67 and 3.33 times more likely to have experienced PTSD at some point in life than relatives of deceased and injured victims, respectively (moderate effect sizes). They are also 2.22 and 4.33 times more likely to present long-term PTSD than the respective comparison groups (moderate effect sizes). These findings are aligned with the existing literature.

In any case, psychopathology in this sample does not appear to vary by victim status. Nonetheless, victim type will be controlled for in subsequent analyses to ensure it does not confound the results.

Sex

In this sample, no statistically significant sex differences were found for psychopathology diagnosed in the past (χ2 = 1.097, p = .29, OR = 1.69, 95% CI [0.62, 4.58]). However, significant differences emerged for current psychopathology (χ2 = 5.643, p = .01, OR = 3.68, 95% CI [1.22, 11.1]) (see Table 5). Regarding these values, women were 3.68 times more likely than men to present current psychopathology, which represents a moderate effect size (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Cohen and Chen2010).

Table 5. Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2) according to kind of past or present disorder between men and women

Note: †There could be comorbidity between disorders among the participants; χ2 = chi-square test; df = degrees of freedom; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

* Statistically significant result (p < .05).

In terms of concrete psychopathology type, women of this sample are 1.98 and 3.06 more likely to have PTSD and anxiety disorders, respectively, than men (for present PTSD: χ2 = 1.119, p = .29, OR = 1.98, 95% CI [0.55, 7.14]; and for present anxiety disorders: χ2 = 3.725, p = .05, OR = 3.06, 95% CI [0.95, 9.78]).

This finding is also consistent with previous research.

However, despite this significant datum, when examining the type of disorder, no statistically significant differences were found between sexes, although for anxiety disorders, the values were very close to the relevant statistical significance.

In any case, in the present study, the participants’ sex should be considered when comparing the groups and performing the main analysis.

Preliminary Analyses of the Differences in Sociodemographic Characteristics between the Comparison Groups (Children of Parents with Past Psychopathology versus Children of Parents without Past Psychopathology)

As the study aims to determine a possible tendency to develop pathology after growing up in a family where the parents presented psychopathology, two comparison groups were proposed:

-

1. Children of parents with past psychopathology (n = 46)

-

2. Children of parents without past psychopathology (n = 20)

For these groups to be compared in the study, at least, their sociodemographic characteristics must not show statistically significant differences. In addition, it is important to know if the variables are distributed similarly between the two groups. The results obtained are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2) and Student’s t-test by comparison group and sociodemographic characteristics

Note: †In the case of help (past and current), the different options could be combined; χ2 = chi-square test; df = degrees of freedom; t = Student’s t-test; FFH: Fisher–Freeman–Halton exact test. FFH was used for contingency tables larger than 2 × 2 due to low expected frequencies. The statistical test reported is the observed χ 2 value used in the computation of FFH; OR = odds ratio

* Statistically significant result (p < .05).

When performing these tests to analyze the distribution of the variables in the sample, no statistically significant differences were found in any of the sociodemographic variables except for marital status. Sex was one of the sociodemographic variables without differences, but its behavior was of special relevance because, as seen, it showed statistically significant differences in terms of the participants’ present psychopathology. As there was no essential difference between the two comparison groups in the main analyses, the effect of sex on the participants’ psychopathology at the time of evaluation would be balanced and would not require additional control in the main analyses.

To analyze whether civil status—the only sociodemographic variable that produced significant group differences—acted as a confounding variable in this sample, we analyzed its influence on present and past psychopathology, and no statistically significant differences were found (past psychopathology: χ2 = 3.354, p = .51/present psychopathology: χ2 = 2.975, p = .56).

Having verified that the variables are equally distributed between the two groups and having controlled for the most relevant variables, the groups could be compared. Therefore, the main analysis was carried out.

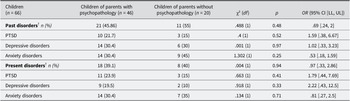

Main Analysis

In this case, no statistically significant differences were found in terms of having a present disorder depending on whether or not the participants were the child of a parent who had past psychopathology (χ2 = 0.004, p = .94). Nor were there any statistically significant differences according to the type of disorder (see Table 7).

Table 7. Pearson’s chi-square tests (χ2) by comparison group and type of present or past psychopathology

Note: †There could be comorbidity between disorders among the participants. χ2 = chi-square test; df = degrees of freedom; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

In addition, we analyzed possible differences in past psychopathology depending on the comparison groups, finding none (χ2 = 0.488, p = .48). The same was true when attending to the type of disorder.

The results of the main analysis are summarized in Table 7.

As described above, ORs were calculated to measure the effect size in this study.

In this case, we found an OR = .97 for present disorders in general. This value is close to 1, so it suggests a difference that is of no practical relevance. This effect size can be considered trivial and weak (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Cohen and Chen2010) and supports the fact that the differences found were not statistically significant. The same is true for past disorders (OR = .69).

However, when broken down by disorders, somewhat higher ORs are observed for present depressive disorders (OR = 2.22, 95% CI [0.43, 12.5]) and present PTSD (OR = 1.79, 95% CI [0.44, 7.69]).

This means that if a person was a victim of terrorism (direct or indirect) and had a parent who suffered psychopathology as a result, that person is 2.22 times more likely to have present depressive disorders and 1.79 times more likely to have PTSD in the long term. However, according to Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Cohen and Chen2010) these OR results are considered small to moderate. Even though these values did not reach statistical significance, the findings may suggest that significance could be achieved with a larger sample size, particularly within the group presenting psychopathology.

Conclusions

Although the immediate and long-term consequences of terrorist attacks on adults and children have been widely studied, far less is known about their impact on entire families—especially over extended periods.

The present study aimed to address this gap by examining individuals who, as children, had one or both parents develop psychopathology following a terrorist attack. Specifically, we investigated whether these individuals, now adults and approximately 25 years removed from the attacks, presented any form of psychopathology, depending on whether their parents had developed it. While extensive literature supports the intergenerational transmission of psychological disorders, and although no previous studies have explored this question in terrorism-exposed populations, we hypothesized a similar pattern would emerge.

However, our findings revealed no statistically significant associations between parental psychopathology and the offspring’s lifetime history of psychological disorders. Similarly, no associations emerged in relation to the offspring’s mental health in adulthood, over the long term.

These nonsignificant findings on the association between parental post-terrorism psychopathology and offspring mental health outcomes in adulthood contrast with most previous studies on intergenerational transmission of trauma-related disorders, which have generally found such an association.

For instance, several studies report that children of parents who developed PTSD or depression following a terrorist attack are more likely to exhibit similar symptoms, particularly in the short term (Comer & Kendall, Reference Comer and Kendall2007; Kar, Reference Kar2019; Pfefferbaum et al., Reference Pfefferbaum, Devoe, Stuber, Schiff, Klein and Fairbrother2005; Yahav, Reference Yahav2011). Similar trends are also found in broader clinical populations. Mardomingo et al. (Reference Mardomingo, Mascaraque, Parra, Espinosa and Loro2005), for example, reported that parental depression increases the risk of depressive symptoms in their children during adulthood.

Other studies have examined the impact of secondary or vicarious trauma—defined as trauma transmitted to individuals who have not directly experienced the traumatic event. King and Smith (Reference King and Smith2016) conducted a systematic review on long-term consequences in children of war veterans with PTSD. Unlike the present findings, they found that parental PTSD was associated with long-term post-traumatic symptoms in the offspring. However, it is important to note that war-related trauma is often prolonged and cumulative, potentially leading to more severe effects than isolated terrorist attacks (Arnaiz et al., Reference Arnaiz, Sanz and García-Vera2020; Slone & Mann, Reference Slone and Mann2016).

In the same vein, the study by Yehuda et al. (Reference Yehuda, Bell, Bierer and Schmeidler2008), which focuses on Holocaust survivors, deserves mention due to its similarities with the present research, as it examines the long-term influence of parental disorders on their children, finding statistically significant results and, moreover, small to moderate effect sizes.

Notably, not all research supports the transmission hypothesis. For example, Burchert et al. (Reference Burchert, Stammel and Knaevelsrud2017) found no evidence that children whose parents had post-trauma mental disorders showed increased levels of psychopathology themselves—findings more aligned with the results of the current study.

Overall, the discrepancy between our results and much of the existing literature may be due to the sample size and statistical power issue, other differences in sample characteristics, the nature and duration of the traumatic events, or the long-term time frame used in this study. These factors may buffer or mediate the intergenerational transmission of trauma and warrant further investigation.

As observed, much of the literature supports a strong theoretical link between parental trauma and its impact on children, evidencing that trauma disrupts children’s developmental processes and can cause long-lasting effects if not properly addressed (Munson, Reference Munson2002).

As the participants in this study were around 5 years old on average at the time of the attacks, it is important to note that older children, who possess autobiographical memory, are likely to experience a more explicit cognitive impact of trauma. However, even younger children—who typically lack such memory before about age 4 (Ortega & Ruetti, Reference Ortega and Ruetti2014)—are also affected, as they respond sensitively to environmental changes and disruptions in caregiver interactions.

Consequently, even if children of traumatized parents do not always meet criteria for psychopathological diagnoses, family dynamics can be affected in ways that create difficulties for the child. For instance, children may assume caregiving roles inappropriate for their age—known as “parentification” or “role reversal”—placing significant pressure on them and affecting their relationships and future family formation (Catherall, Reference Catherall and Figley1998; Letzter-Pouw et al., Reference Letzter-Pouw, Shrira, Ben-Ezra and Palgi2014). Future research should examine this phenomenon in families affected by terrorist attacks.

Therefore, it is crucial to provide a stable, supportive environment that balances care continuity without overprotection, as children’s adaptation depends heavily on their contextual support (Punamäki et al., Reference Punamäki, Qouta and Peltonen2017; Comer & Kendall, Reference Comer and Kendall2007).

Although our results did not reach statistical significance, effect sizes suggest children of parents with past psychopathology were 2.22 times more likely to develop depressive disorders and 1.79 times more likely to have PTSD in adulthood. Unfortunately, no terrorism-related studies report effect sizes for such outcomes. However, in the general clinical population, Mardomingo et al. (Reference Mardomingo, Mascaraque, Parra, Espinosa and Loro2005) found that parental depression can increase offspring’s risk of adult depression by up to five times.

Considering the literature and comparing it with the results obtained, we should reflect on the limitations of this study that may have influenced the lack of confirmation of the working hypothesis.

In this regard, as noted in the Method section, an a priori power analysis based on the Yehuda et al. (Reference Yehuda, Bell, Bierer and Schmeidler2008) study, as it is comparable, indicated that a minimum of 59 participants per group would be required to detect significant differences in mood disorders, and 74–75 per group for PTSD, assuming (α = .05) and 80% power. However, the present study included 46 participants in one group and 20 in the other. This reduced sample size limits the statistical power of the analyses, increasing the likelihood of failing to detect a true effect, if it exists. Although these results should be interpreted with caution—this being the study’s main limitation—it is important to note that the sample is highly specific and difficult to access. The findings nonetheless offer valuable preliminary insights and may help guide future research with larger samples.

Also, in the “Variables and Instruments” subsection of the Method section, we emphasize that the information on the participants’ past disorders was measured retrospectively, which is a methodological problem for several reasons. First, it is possible that the interviewees were acquiescent and over-represented symptoms that they may not have had or, if they had existed, may not have been severe enough to represent a psychological disorder. Secondly, the memory of the event may be far from the reality of the incidents because, as previously reported, the average age of the group of children was around 5 years old when the attacks occurred, at which time, memory is still fragile and not well consolidated (Ortega & Ruetti, Reference Ortega and Ruetti2014). Finally, the fact of collecting the information retrospectively makes it difficult to establish cause–effect relationships between terrorist attacks and the psychopathology developed by the participants because years ago, there may have been other predisposing and precipitating factors of the disorders.

Another factor to be considered that is closely related to the study’s retrospective nature is the measurement instrument used to make the diagnosis. The SCID-I-CV (First et al., Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams1999) allows for adequate collection of information about past affective disorders and episodes, but it does not systematically measure other types of past disorders, such as PTSD and anxiety, making them more difficult to track. Although the psychologists who carried out the assessments were trained to carry out this tracking, there may have been shortcomings in this regard.

In addition to these limitations, the representativeness of the sample must be considered, as all participants in this study are victims associated with the AVT. A common criticism of research on terrorism victims is that most studies rely on data from victims belonging to associations, thereby excluding those who choose not to participate and potentially limiting representativeness of the general population. However, our analyses of confounding variables yielded findings consistent with existing scientific literature conducted with victims who did not necessarily belong to any victims’ association, revealing a higher prevalence of psychopathology among injured victims compared to relatives and among women compared to men.

Likewise, despite the efforts to analyze the influence of possible confounding variables to increase the study’s internal validity, the design used is not experimental, so unequivocal cause–effect relationships cannot be established between the studied variables, nor can we rule out some degree of association between the variables, even if the data are not statistically significant.

Despite the limitations of the present study, the long-term distress experienced by some victims of terrorism, as well as the chronicity of disorders among them, has been widely documented and acknowledged. Receiving social support following such events represents an important variable in the recovery and well-being of victims, as the absence of this support has been associated with the high and very long-term prevalence of psychopathology among terrorism victims (García-Vera et al., Reference García-Vera, Sanz and Sanz-García2021; Gutiérrez, Reference Gutiérrez2016).

For this reason, in the frequency analysis, we included variables indicating how many participants had received or were currently receiving support at the time of assessment.

In this regard, interventions such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT) have demonstrated effectiveness (Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Sanz, Garcia-Vera, Gesteira, Gutiérrez, Zapardiel, Cobos and Marotta-Walters2019) and efficacy (Gesteira et al., Reference Gesteira, Garcia-Vera, Sanz and Shultz2025) in promoting recovery among victims of terrorism.

It is also remarkable that, given that between 82% and 85% of terrorism victims who develop PTSD tend to recover spontaneously over time (Cukor et al., Reference Cukor, Wyka, Mello, Olden, Jayasinghe, Roberts, Giosan, Crane and Difede2011; Morina et al., Reference Morina, Wicherts, Lobbrecht and Priebe2014; Neria et al., Reference Neria, Olfson, Gameroff, DiGrande, Wickramaratne, Gross, Pilowsky, Neugebaur, Manetti-Cusa, Lewis-Fernandez, Lantigua, Shea and Weissman2010), the reasons behind this improvement remain unclear. These findings prompt reflection on the protective factors present in the lives of those affected, which may enable a more favorable course and progress throughout life. Regarding children and adolescents who experience such difficult situations, they appear especially vulnerable to severe psychopathological sequelae; however, some studies also highlight protective factors and resilience within this younger population (Durodié & Wainwright, Reference Durodié and Wainwright2019; Yahav, Reference Yahav2011).

Among these protective factors, the literature mentions the availability of attachment figures (Slone & Mann, Reference Slone and Mann2016), social support, personality traits such as extraversion and openness to experience, and having lived in a safe environment without prior trauma (Yahav, Reference Yahav2011).

Given the undeniable existence and significance of protective factors, these must be considered when discussing psychopathology, as their presence and the subsequent recovery over time reduce the chronicity of mental health problems and improve quality of life. Furthermore, expanding research in this direction is crucial for advancing prevention efforts.

Also, regarding future lines of research, one of the issues to consider is the scarcity of studies on the prevalence of disorders other than PTSD in victims of terrorism, especially in relatives. There have been hardly any articles referring to the prevalence of anxiety disorders in indirect victims and even fewer referring to families.

Although PTSD is the disorder most closely linked to trauma and one of the most severe consequences of trauma, it would also be interesting to know the scope of terrorism on other types of disorders or difficulties in daily life that, without being so severe, also require actions aimed at reducing the damage and recovering the normal balance of day-to-day life.

It would also be advisable to try to recruit participants who have been victims of terrorism but who do not belong to associations to be able to compare these studies with those that include associated victims and thus contribute to the generalization of the findings.

In addition, some authors indicate the need to develop longitudinal research, which informs on the long-term consequences suffered by families hit by terrorism (Kar, Reference Kar2019) and replication and follow-up research, which allows updating the existing data and contrasting the information provided by authors who investigated the consequences of events practically right after they had occurred (Durodié & Wainwright, Reference Durodié and Wainwright2019). This is mainly to reduce unnecessary medical, psychological, and psychiatric interventions and to avoid iatrogenesis because when stress does not reach psychopathological levels, it requires a series of interventions different from those implemented for more severe disorders (North, Reference North2010).

Lastly, it would be recommended, if larger samples were available, to use multilevel modeling or latent class analysis to explore intergenerational effects of trauma with greater nuance.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, we highlight the importance of this research work, as, to date, it is the first study on the long-term consequences that parents’ psychopathology can have on their children, specifically in victims of terrorism.

Thus, despite the differences between terrorism and other types of traumatic events, the results of this study do not reveal a specific impact of parental pathology on children, at least in victims of this kind of event. However, a slight trend in this direction in the data was found, which must be verified by other studies.

However, the fact that no differences were found could indicate that most victims, especially minors, recover over time, especially if they did not experience the attack personally. Without ignoring the large-scale suffering caused by these events, this highlights the need to promote human beings’ resilience in the face of adversity and send a message of hope for recovery. We should give more importance to the study of protective factors in the face of these experiences and, thus, reduce fear in the general population because fear is terrorism’s most powerful weapon.

Data availability statement

Due to concerns about the anonymity and confidentiality of the study participants, the data are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación; the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad; the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, the Spanish Association of Victims of Terrorism, and the Universidad Complutense.

Author contribution

S.P.B. contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing the original draft. C.G. was responsible for conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, validation, and writing (review and editing). J.S. was involved in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, validation, and writing (review and editing). M.P.G.-V. contributed to data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, and writing (review and editing).

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Grant No. PSI2011-26450); the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Grant No. PSI2014-56531-P); the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (Grant Nos. PGC2018-098387-B-I00 and PID2023-150340NB-I00), and the Spanish Association of Victims of Terrorism (Grant Nos. 270-2012, 283-2013, 53-2014, 100-2014, 192-2014, 40-2015, 134-2015, and 22-2016).

Competing interests

The authors declared none.