1.1 Introduction

Is it possible to capture an overarching continuity that connects Kelsen’s first monograph – Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri (1905), still to this day unavailable to Anglophone readersFootnote 1 – to his most famous and extensively mined works in legal theory and jurisprudence? Is there a fil rouge that binds together the very early years of ‘the most brilliant jurist of the twentieth century’Footnote 2 and the core of his lifelong meditation on sovereignty, democracy, and international law? In other words, does it make sense to read his debut as a legal scholar – a meticulously researched yet scholastic analysis of a prominent work in medieval political philosophy – as an anticipation of concerns and ideas that Kelsen would systematically develop in later and truly original books, such as Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts (1920) and Die Reine Rechtslehre (1934), and, in particular, two major writings of his early American years – Law and Peace in International Relations (1942) and Peace Through Law (1944)?

Without falling into the danger of anachronistic readings or forcing upon Kelsen’s intellectual journey any of the four mythologies (of doctrines, coherence, prolepsis, and parochialism) famously detected and chastised by Quentin Skinner,Footnote 3 this chapter unearths and explores the ancestry of Kelsen’s signature writings. In doing so, it tries to ask – and test – whether his first, least influential, volume anticipated certain key themes that would come to define his international pacifism and legal cosmopolitanism, which were at the core of the English works that he published from the early 1940s through the early 1950s, including The Law of the United Nations. A Critical Analysis of Its Fundamental Problems (1950) and Principles of International Law (1952), completed on his retirement from the University of California at Berkeley.

Going back to Kelsen’s very first book is neither a question of historiographical fetishism nor a dry exercise in legal antiquarianism. Rather, it is an exciting opportunity to read those pages from a new angle, asking whether and to what extent we can discern, in the flow of its analysis, an embryonic formulation of notions, thoughts, and frameworks that Kelsen would articulate over the following decades. Ostensibly, little can be found in this work of the scholar that would later challenge early twentieth-century jurisprudence and develop his ‘Pure Theory of Law’. However, my chapter suggests that Kelsen’s later work, with its rebuttal of the dogma of sovereignty and its emphasis on the primacy of international law,Footnote 4 pushed in new directions two concepts at the core of Dante’s De Monarchia: the unity of law, on the one hand, and the pursuit of a global legal system, on the other, that can defuse the ticking bomb of conflict and thus pave the way to a pacified world order (civitas maxima). Both elements fascinated the young Kelsen and left an enduring mark that is today worth revisiting and contextualising to recover his first steps as a political and legal theorist.

1.2 Kelsen before Kelsen: History and Historiography of an Intellectual Ancestry

Decidedly understudied,Footnote 5 Kelsen’s earliest monograph did not figure prominently in what was, for decades, the most authoritative biography of the Austrian jurist (at least until the recent publication of the colossal volume by the director of the Kelsen Institut in Vienna, Thomas Olechowski).Footnote 6 In fact, Rudolf MètallFootnote 7 devotes very little space to Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri, partly echoing Kelsen himself, whose 1927 Selbstdarstellung recalled very succinctly how the first work that he had penned and published while still a doctoral studentFootnote 8 was purely ‘of a historical-dogmatic nature’.Footnote 9 In his later and longer Autobiographie (1947),Footnote 10 Kelsen explained in more detail the genesis of his infatuation with Dante’s workFootnote 11:

Then, in one of Professor Leo Strisower’s lectures on the history of the philosophy of law (the only course I took regularly), I learned that the poet Dante Alighieri had also written a work on the philosophy of the state, De Monarchia. I read that work and I immediately began to think about describing Dante Alighieri’s doctrine of the state (Staatslehre), reconnecting it to the main paradigms in the state philosophy of his time. I asked Strisower whether he thought such a work advisable, but Strisower strongly advised against it, evoking the endless literature on Dante and reminding me that, first, I had to finish my studies. However, I was not deterred, especially since in the literature on Dante I had not found any monographs on the poet’s doctrine of the state; moreover, I told myself that it was better to try my hand at a work that interested me, even though I might have never published it, rather than to lose all passion for the study of law and the state by limiting myself to studying only for the sake of passing exams. Indeed, that work of mine was published in 1905, before I had even obtained my doctorate, in the series of the ‘Wiener Staatswissenschaftliche Studien’, enjoying a relatively success. It is, however, the only book of mine that has not received any negative criticism. It was well received also in Italy. However, it was unquestionably nothing more than a scholastic work with no ambition for originality ([S]icherlich nicht mehr als eine unoriginelle Schülerarbeit).Footnote 12

Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri was released the same year that Kelsen converted to Roman Catholicism (he was agnostic but did so strategically to prevent his academic ambitions from being crushed by prejudice against his Jewish ancestry). First published in 1905 in a volume of the prestigious Viennese series on the theory of the state,Footnote 13 it was reissued a few months later as a self-standing book of 152 pages.Footnote 14 Its preface made crystal clear the distinctively legal – rather than literary or philological – nature and purpose of the project.

If one casts a glance at the German literature on Dante, one will observe that those who have been interested in the Poet are mainly literary historians and philologists. Even the history of philosophy has established with solicitude Dante’s place in the development of the philosophical discourse of the Middle Ages. […] However, the political position of Dante has not so far been systematically studied from a legal point of view or examined in a sufficiently critical manner; the same applies to his general doctrine of the State, which underlines his political philosophy. The following work has set itself the task of filling this gap. I tried to pursue two goals with my book: on the one hand, to clarify his doctrine of the State starting from a thorough analysis of his grand vision of the world and of life; on the other, to put on the map Dante’s position in the history of the doctrine of the State in the Middle Ages.Footnote 15

In the German-speaking world, Kelsen’s book would become a reference point for the study of Dante’s political thought. The Görres-Gesellschaft – a learned society founded in 1876 to promote scholarship in Roman Catholic Germany and abolished by the Nazis in 1941 – extensively drew on it for the five-page entry on Dante in revised editions of their political dictionary (Staatslexicon).Footnote 16 The first academic to signal it to an Italian readership was the jurist and historian Arrigo Solmi, who reviewed it in 1907 in the ‘Bulletin of the Italian Dante Society’. He criticised the ‘otherwise laudable’ book for its attempt to distil ‘an organic vision of political science’ from a work focused exclusively on universal monarchy (the empire). For Solmi, Kelsen’s misunderstanding of the very nature of De Monarchia significantly affected the overall accuracy and success of his interpretation.Footnote 17

Kelsen’s book then fell into a prolonged oblivion until legal philosopher Vittorio Frosini shed new light on it in the context of an important essay titled ‘Kelsen and Dante’ in 1974. He emphasized Kelsen’s ambitious attempt to offer a reconstruction of the poet’s political thought as a wholeFootnote 18 by connecting De Monarchia to other political writings by Dante – from Book IV (the last and longest) of Convivio (1304–1307) to his letters on public affairs, such as those ‘To the Princes and Peoples of Italy’ (October 1310, written in the context of Henry VII’s Italian campaign), ‘To the Florentines’ (March 1311), and to Henry VII himself (April 1311).

Kelsen focused primarily – though (as noted by Frosini) not exclusively – on De Monarchia for legitimate reasons. Written in Latin between 1313 and 1320 (during the same years when Dante was composing Paradise),Footnote 19 it was – and still largely is – considered the most systematic theorisation of universal monarchy in the broader horizon of medieval political philosophy (as well as the most notorious due to Dante’s global reputation as the author of the Divine Comedy). It was also a work that, in the early twentieth century, had not yet been under the magnifying glass of German scholars,Footnote 20 conventionally privileging other representative figures of medieval political thought such as William of Ockham and Marsilius of Padua (two thinkers who had both died in Munich and written extensively on the conflict between the papacy and the empire). The young Kelsen understood the negative repercussions of this gap in the German literature (despite the existence of three German translations of De Monarchia, which he would reference in Die Staatslehre: 1559; 1845; 1872). Surprising for today’s readers, the neglect in which Dante’s book on world monarchy had fallen for several centuries was not surprising at all in the early twentieth century given its tortuous Rezeptionsgeschichte. Deemed a dangerous source of heretical thought, De Monarchia was condemned by Pope Paul IV and included in 1564 in the Index librorum prohibitorum – a continuously amended list of books prohibited by the Roman Catholic Church. It remained a banned reading on various iterations of the Index until it was removed in 1881 under Pope Leo XIII (the famous author of the encyclical Rerum Novarum and a committed disciple of Thomism and Aquinas, whose work he promoted and revived as the true foundation of the Catholic Church through the Editio Leonina). The condemnation by the Catholic Church inevitably cast on De Monarchia a spell that endured for centuries and led to its prolonged oblivion abroad, including in Germany.

The initial part of Kelsen’s book is devoted to an analysis of the historical and political situation of the thirteenth century, approached in gradually decreasing concentric circles. First, it describes the international situation, characterised by the struggle between the two major universal authorities of the time – the papacy and the empire. Second, it focuses on the Italian situation, pervaded by factional conflict. Finally, it undertakes a detailed scrutiny of the political conditions of Florence, which, as Kelsen recalls, Burckhardt considered ‘the first modern state in the world’. Kelsen also mentions the active political position of Dante in his native city until his ban and exile, which represents the painful personal background of the genesis of De Monarchia. Against this backdrop, the stateless Dante developed his vision of a globally pacified humanity within the borders of a universal and – most importantly – temporal monarchy as the only antidote to papalist claims and the endless factionalism that he had witnessed and personally experienced. Peace – for himself, for Florence, for Italy, and for the world at large – was Dante’s strongest desire – indeed, the central concept of his political philosophy in De Monarchia.Footnote 21

The first two chapters of Kelsen’s book succinctly but thoroughly chart this intricate context, which is of vital importance for understanding the genesis of De Monarchia and its driving impetus. After the large-scale overview of thirteenth-century factional politics in Chapter 1, Kelsen dedicates Chapter 2 to an erudite analysis of the main trajectories of late Medieval ‘state doctrine’, precisely to let readers understand the context and originality of Dante’s arguments.Footnote 22 The remaining eight chapters excavate the foundations of Dante’s state doctrine – its origins, purposes, form, and legacies; the relationships between the emperor and his subjects and between temporal and spiritual powers; and the political and legal features of Dante’s recipe for a world empire, rooted in Greek, Roman, and Christian intellectual traditions. Kelsen concludes with a survey of the sources of Dante’s state doctrine and its afterlives in later medieval jurisprudence: for him, De Monarchia represents the apogee of the medieval worldview and paves the way to legal modernity, identified with the ideas of Bodin.

Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri is indeed an unusual monograph for those who are used to Kelsen’s style and methodology; it is a diligent work of historical, political, and legal analysis that largely eschews the razor-sharp normativity of his later publications. It is also the first work in which Kelsen manifested an embryonic interest in questions of world older and global peace, long before he would systematically mine these topics over the following decades. Even more surprising, considering his commitment to scientific objectivity, methodological purity, and value neutrality typical of the German Neo-Kantian school, is the early Kelsen’s enquiry into the politics of Dante’s theory. As Oliver Lepsius has recently argued, ‘On Monarchy offered him the opportunity to address the political background of epistemological positions’; it provided him not only with ‘a lesson in medieval epistemology and political philosophy’ but also with a ‘training ground for the criticism of ideologies’.Footnote 23

1.3 Dante before Kelsen: World Government through and beyond Aristotle

Calling for a world government in the form of a temporal and universal monarchy, Dante’s De Monarchia outlines what, with Ernst Bloch, one could describe as a ‘concrete utopia’ – that is, a praxis-oriented vision of an alternative future rooted in an experiential critique of current and everyday configurations of power.Footnote 24 It is a work that ambitiously sits at the crossroads of theory and practice, growing out of its author’s first-hand, prolonged, and painful experience of political factionalism in the daily life of medieval Florence and Italy in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. In fact, Dante had been deeply involved in the politics of his native city and had participated directly in the vicissitudes of the Florentine Republic since the age of twenty-four (the same age Kelsen was when he wrote his book on Dante).Footnote 25 He belonged to the Florentine Guelphs (the supporters of papal primacy over public affairs, hegemonic since 1266) and, as such, participated in the famous Battle of Campaldino (1289), which not only secured Guelph dominance in Florence but also initiated the split, within the pro-papal faction, between Black and White Guelphs. Dante was a leading member of the latter, demanding limitations on the extent of the pope’s mounting ambitions over Florence and holding multiple political and diplomatic posts (including his election to the city council of the Priors in 1300) after his entry into the Florentine public arena in 1295.Footnote 26 In late 1301, while on an ambassadorial mission to Rome, he learnt that the exiled Black Guelphs had seized the city through a coup d’état, deposed the Priors, confiscated the property and burnt to the ground the houses of the Whites. This sudden turnabout was made possible by the new alliance between Pope Boniface VIII, the French (with Charles of Valois, brother of King Philip IV, dreaming of an imperial crown and thus aiding the papal cause for strategic purposes), and the exiled Black Guelphs. In early 1302, Dante was sentenced first to exile and then to death ‘in contumacia’ (i.e., without him being at court). Despite multiple attempts to make it back to his beloved Florence, he would never see his hometown (and family) again, dying in exile in 1321 and having his ban lifted by a decree of the Florentine city council only in 2008 (sic!).

The pages of De Monarchia eloquently bear evidence of Dante’s political passion and personal anguish. Indelibly burned by the fire of internecine divisions, civil unrest, and factional vengeance, he wrote a treaty exactly to process the traumatic experience – personal and collective – of losing everything and to outline a vision that could offer a way out of despair in the present and restore hope for the future.

Dante’s political theory of empireFootnote 27 rests on one fundamental axiom: the world should be governed by one sovereign, whose rule would ensure unity and peace for the multiple constellations of polities otherwise unravelled by civil war and conflict. In calling for a world monarchy (empire), Dante creatively merged ideas from different intellectual and philosophical traditions, giving a distinctively Christian twist to Stoic cosmopolitanism and making it suitable to the overarching Aristotelian framework of his political thought. As Alessandro Passerin d’Entrèves pointed out in his pioneering book Dante as a Political Thinker (1965), the three cornerstones of the poet’s political vision are Civitas, Ecclesia, and Imperium – three blocks in the construction of human society that bear some resemblance to the three steps in the unfolding of human gregariousness famously theorised by Aristotle in Book I of Politics (household, village, and city). In Dante’s view, a global empire is the ideal remedy for the fragmented landscape of kingdoms and republics that ceaselessly wage war one against the other; it also promises to conjoin political freedom (from both factions at home and foreign powers abroad) and justice as the antithesis of the inescapable corruption of regime types.Footnote 28

These two goals – as Aristotle had taught and as Dante reiterates – are deeply intertwined. It is precisely the lack of freedom that undermines governments, no matter how artfully designed, derailing them from the pursuit of the common good, precipitating them in a condition of oppression by the ruler(s), and making political power instrumental to private and/or factional interests. Grounding the need for a world empire is, for Dante, once again a quintessentially Aristotelian notion: humanity has its own goal, purpose, end – its telos. To perform this task, which is to actualise by means of reason the human potential for arts and sciences according to God’s plan, world peace is essential. Quarrelsome and, thus, short-lived, governments make human flourishing unattainable domestically and impossible globally. Human culture requires the full coordination of humanity as a whole – beyond individuals and communities – within a world order that minimises the incendiary eruption of conflict and the disruptive – and destructive – repercussions of warfare on multiple scales. Here, Dante dexterously revisits the cosmopolitanism of the ancient Greek Stoics through the lenses of Cicero and Marcus Aurelius: he finds humankind’s kinship in the shared potential for rationality (intellectus possibilis), making reason – the divine element in each of us – the foundation of law (ius) rooted in nature and theorising justice as the normal condition of life among humans. At the same time, he shares with Augustine the idea that peace is the foundation and justification of all forms of government. Accordingly, to overcome civil war and ensure planetary peace among the citizens of the universal community (what Dante calls humana civilitas), one global sovereign – a single world ruler – is needed. This sovereign’s jurisdiction and sovereignty have priority over – and indeed encompass – those of lesser rulers and their respective regimes.

As Prue Shaw has pointed out,Footnote 29 while the premises of Dante’s argument are Aristotelian and rooted in the framework of Ptolemaic astronomy, the deductions that he draws from them are distinctively his own. Just like any whole consists of and is superior to its parts, humanity, too, must rise above and embrace each of its constituent elements (ranging from families and villages to cities and kingdoms), replicating the same principles of oneness and unity that operate throughout the entire cosmos and resemble the distinctive qualities of its Creator. Dante then proceeds to apply to the microcosm of humankind the same logic that governs the macrocosm of the Primum Mobile (i.e., the outer sphere in the geocentric model of the universe): one single law, emanating from one single Maker, should regulate the motion of humans on a global scale.

To escape the quicksand of endemic conflict, it is vital that the world ruler attends to his lawgiving and peacekeeping tasks through a disinterested approach to politics and, most importantly, through an unbiased understanding of the relationship between means and ends. The unparalleled political power bestowed upon him should never be instrumental to the self-centred goal of his own aggrandisement; rather, it should be conducive to the autonomy, happiness, and self-fulfillment of human individuals and collectives alike. Once again drawing on Aristotle, Dante warns about the shortcomings of three defective regime types – tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy – equally corrupted by the self-interestedness of their respective rulers (the one, the few, and the many). He celebrates kingship for its ability to most closely resemble the natural order envisioned and enacted by God; for the ability of the monarch to refrain from the destructive drive of greed (cupiditas); and for his commitment to channel the fervours of appetition and volition into the pursuit of justice.

The Aristotelian foundations of De Monarchia are also evident in the terminology that Dante employs and in the methodological construction of his arguments. Owing extensively to ‘the Philosopher’ are the principles of causation, potentiality, and order that underpin Dante’s political vision (especially in Book I), as well as his emphasis on the importance of proceeding from first principles, reaching universal conclusions syllogistically and scrutinising the fallacious logic of possible counterarguments (including fallacia accidentis, fallacia secundum non causam ut causam, fallacia secundum quid et simpliciter, and the erroneous construction of syllogisms).Footnote 30

What is significant about De Monarchia is how it mobilises ideas of Scholastic theology to develop a distinctively secular argument for world monarchy against the universalist pretensions of the papacy to exercise ultimate control over all secular states (as in the papalism defended by Boniface VIII or Giles of Rome’s De Ecclesiastica Potestate, c. 1302).Footnote 31 This project starts already with the opening of Book I. Dante emphasises that ‘the Higher Nature’ (i.e., the first Mover, God) has gifted all men ‘with a love of truth’ – a passage that closely resembles the opening statement of Dante’s prior work, Convivio,Footnote 32 which in turn was echoing the beginning of Aristotle’s Metaphysics. In support of this statement, Dante offers a profusion of Biblica images to argue that humans have a duty to make the most of their potential for knowledge and thus actively contribute to the flourishing of future generations. Imprinted by their Maker with a natural proclivity towards knowledge (as the wax-and-seal metaphor suggests more extensively in Book II), humankind managed to coexist peacefully, albeit briefly, only when a universal monarchy ruled over the entire world according to God’s plans. As the conclusion of Book I points out, it was the time when Caesar Augustus, the first Roman emperor, reigned for almost half a century (27 BC–14 AD) and Jesus was born. While an empire also existed in Dante’s time, acknowledged by the papacy and claiming to be the successor of the Roman Empire, the source of imperial authority remained disputed. Accordingly, as Dante argues in Book II, the challenge ahead consists not in the construction of an empire but in the guarantee of its secular nature.

While Book I offers a philosophically grounded account of humans’ place in the broader horizon of cosmic order, Book II provides a selective reading of key chapters and figures in Roman history – from the city’s origins to the empire of Augustus. Dante follows in the footsteps of historians (e.g., Orosius and Livy) but draws especially on the works of classical poets, such as Lucan’s Pharsalia and Virgil’s Aeneid. The intellectual hegemony of Virgil in Book II – equivalent to that of Aristotle in Book I – is indicative of the overall project of Dante in this specific portion of De Monarchia, namely, a Christian hermeneutics of the Roman past and, at the same time, a secular interpretation of Christ’s redemption of humankind. In Dante’s account, the birth and death of Jesus become intelligible only when set against the backdrop of pagan history – that is, not merely in Biblical terms but as events that granted full legitimacy to Rome’s empire and that, accordingly, set the stage to rethink – both in theory and in practice – the form and scope of political institutions. As Dante contends, God’s will made Roman history unfold the way it did. Each chapter – 3 to 5 – of Book II presents and unpacks one argument in support of this view. The first is the natural distinction or nobility of the Romans. Syllogistically resting on two premises (major one: the noblest race should rule over the others; minor one: the Romans descended from Aeneas), the distinguished ancestry of the Roman gens ensured their excellence and, in turn, laid the grounds for their rightful lordship on a global scale, as Dante argues drawing eclectically on Aristotle, Livy, Juvenal, Virgil, and the New Testament. Second, several extraordinary events occurred at critical junctures of Roman history and should be interpreted as miracles, confirming that the glorious empire of Rome was not a contingent accident but, rather, a divinely ordained plan.Footnote 33 Third, the heroic behaviours of great Roman citizens – from Cincinnatus and Fabritius to Camillus and Cato – exemplified the civic mindedness and selflessness that elevated Rome and ensured its global hegemony in the pursuit of universal peace (once again, Dante projects Aristotle’s theory of causes onto Roman history). To revive this glorious past and refurbish the short-lived harmony that the world once enjoyed under Augustus, it is imperative to honour a natural principle: humankind should fall under the authority of the worthiest nation.

The first two books of De Monarchia set the stage for the core of the treatise, presented in Book III, namely, the relationship between the two universal authorities of the era – the pope and the emperor (the ‘two great lights’, in the words of Genesis) – and their respective claims to hegemony. Honouring the classical rules of dialectic and disputation, Dante critically engages with each of the arguments (scriptural, historical, and from reason) supporting the two sides. In his own words, he operates like a gladiator armed with a shield and adamantly fighting in the pursuit of truth against the blatant lies of papal polemicists, especially those brandishing the pope’s decretals as the only legitimate source to solve the dispute.Footnote 34 To prove, once and for all, the autonomy of ‘the Roman Prince’ from ‘the Roman Pope’, Dante resorts to an ingenious strategy: he suggests a thought experiment, imagining what (absurd) consequences would follow if the papists’ (flawed) assumptions were true (reductio ad absurdum). Specifically, he challenges the conventional hierocratic argument at the core of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century papist propaganda, namely, that the two great lights (duo magna luminaria) mentioned in the opening book of the Old Testament (one greater: the sun; one smaller: the moon) are allegories of the spiritual and the temporal powers and that, just like the sun sheds light on the moon, the authority of the vicar of God on Earth (the pope) is prior to the emperor’s.

In Dante’s account, the papalists’ interpretation of this scriptural passage is biased in terms of both the chronology and the logic of creation. Man, in fact, was created two days after God made the sun and the moon on the fourth day; therefore, envisioning a remedy before the Fall of man would entail the priority of accidents over substance (again in Aristotelian terms). Dante also nuances the astronomical argument of his opponents – the sun is not responsible for the moon’s existence or movement (based on Aristotelian-Ptolemaic cosmology) but allows it to shine more effectively – precisely to suggest a conciliatory approach to the coexistence of temporal and secular authorities.Footnote 35

Among the historical arguments advanced by papal apologists, the most incendiary one concerned the controversial ‘donation of Constantine’ – a (forged)Footnote 36 document that, at least since the eleventh century, was routinely referenced as marking the origins of the temporal authority of the Church.Footnote 37 A child of his time, Dante takes for granted the historical authenticity of the document but questions its validity on the basis of two related arguments: on the one hand, Constantine’s (lack of) authority to suddenly dispose as he pleased of territories and prerogatives that had traditionally belonged to the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire; on the other hand, the pope’s (lack of) authority to accept the (alleged) gift that he had received. Through his donation, in fact, Constantine violated the unity and indivisibility of imperial rule and thus acted against ‘human right’ (contra ius humanum), that is, ‘the foundational principle of the empire’ (the Church is Christ), prescribing one imperial government for all humankind. Not only does Dante point out that ‘nobody has the right to do things because of an office he holds which are in conflict with that office’, so that ‘to divide the empire would be to destroy it’; he also reminds his readers, including his antagonists, that ‘all jurisdiction is prior to the judge who exercise it (omnis iurisdictio prior est suo iudice), for the judge is appointed for the sake of the jurisdiction, and not vice versa’.Footnote 38

Finally, once again weaving together Aristotle (Ethics) and the Scriptures (Matthew and Luke), Dante uncovers another substantial flaw in the arguments of papal supporters, namely, that the Church was ‘utterly unsuited’ to receive the (alleged and illegitimate) donation. As he indicates in Book III of De Monarchia, a donation is legitimate only when there is ‘a suitable disposition not just in the giver, but in the recipient as well’ – or, in Aristotelian terminology (Ethics, IV), when it is present at the end of both the ‘agent’ and the ‘patient’.Footnote 39 Since ecclesiastical authorities are expressly forbidden to receive temporal goods, no bestowal of political power upon the pope would be legitimate.

1.4 In the Mirror of the Past: Kelsen and Dante between Conflict and the Quest for Global Peace

How can we make sense of the fact that the twenty-four-year-old Kelsen was instantly and stubbornly seduced by a work as dated and supposedly unattractive to young readers as Dante’s De Monarchia? Before answering this important question, it is worth noting that significant historical and existential analogies connect the turbulent biographies of the two thinkers, despite the approximately six hundred years that separated them.

As Monica Garcìa-Salmones Rovira has emphasised in her study on international legal positivism,Footnote 40 Dante (1265–1321) and Kelsen (1881–1973) lived and wrote in times of profound ruptures and transitions. The former was a child of the medieval pre-state age, a citizen of a republic torn apart by factional conflicts, and a witness to the fragmentation of the Italian peninsula into a multiplicity of independent municipalities, principalities, and kingdoms. The latter was a son of the Habsburg monarchy and lived at the dawn of the reflection on Internationalism,Footnote 41 when the Westphalian international order designed in the mid seventeenth century was beginning to crumble and the cataclysm of the First World War was looming on the horizon. Dante and Kelsen painfully experienced the political and cultural disintegration of their respective territories: both were literal outcasts, coping with the experience of ‘statelessness’ and thus trying to imagine a political and legal framework that could overcome fragmentation and ensure peace (although, in the case of the Austrian jurist, emigration occurred long after he had written and published his book on Dante). Coping with rootlessness, they turned their respective work into an opportunity to pragmatically think through the systemic causes of their exile (in the case of Dante) or escape (in that of Kelsen). They both realised that only when peace is guaranteed and maintained can humans coexist across differences (domestically) and borders (internationally) and thus set the premises for their individual, collective, and cosmopolitan flourishing.

Nevertheless, despite these important affinities as humans, Dante and Kelsen also presented significant differences as thinkers, especially in terms of the intellectual visions that they developed in response to analogous challenges. Dante’s project is robustly built upon classical and medieval foundations, evident in the constant dialectic between the temporal and the spiritual elements that underwrites his entire work. The earthly global monarchy is to be understood as one part of the divine state encompassing heaven and earth at once – a microcosm of the whole universe governed by the supreme ordering principle of unity (principium unitatis) under the lordship of God. Within this system, the world monarch exercises temporal authority over the entire human race, while the pope has the exclusivity of spiritual authority; both the emperor and the pope stand below God, the origin and ultimate foundation of law and justice. In contrast, Kelsen relies on a secularised worldview that makes him highly sceptical of theology and anything that falls beyond scientific logic. However, he glimpses in Dante a project that not only is emblematic of the medieval Weltanschauung but also anticipates important developments in legal and political thought and practice. As the young Austrian jurist puts it in one of the most significant passages of the book: ‘It is for this reason that Dante’s doctrine of the State arouses our interest, for the fact that, in it, Dante, medieval man of Scholasticism, fights against Dante, modern man of the Renaissance’.Footnote 42

Kelsen’s early interest in Dante is plausibly also conditioned by the distinctive situation of the Austro-Habsburg Empire, a geopolitical entity situated in the heart of the European continent and populated by a constellation of heterogeneous and often centrifugal identities (cultural, linguistic, religious).Footnote 43 The vivid observation of the challenges of pluralism as well as the possibility of coexisting under a unified legal framework might have motivated his historical inquiry and arguably coloured his reading of De Monarchia. Although Kelsen was never an imperialist, his later ideal of a universal legal order presents interesting affinities with Dante’s project of a world monarchy. Already in the early 1900s, for the future author of Die Reine Rechtslehre, legal unity seems to be the key to solving the puzzle of compliance. For him, as his future publications will explain, a legal system of governance is inevitably coercive, in the sense that it must always provide for sanctions in response to breaches of its norms (law differs from morality precisely because it entails sanctions).Footnote 44 International law is no exception to the notion that any system of law is essentially coercive (the main difference is that, in the former, the authority to use coercion is less centralised than it is in a municipal legal system). From this perspective, the old Dante and the young Kelsen converge in their analogous of ‘peace through law’, seeking to bring order and peaceful stability by means of a supra-state dimension that starts from legality itself.

A further element that might have fascinated the young Kelsen is Dante’s idea of the emperor as the supreme judge presiding over the universal legal order and neutralising the intrinsic contentiousness of politics. Faced with a fragmented and highly conflictual landscape, Dante believes that it is vital to identify an impartial authority – the imperator – capable of settling disputes between contending entities.Footnote 45 Owing to the emperor’s officium, the world is saved from expanding hegemonic projects that would precipitate it into a condition of permanent conflict. Dante’s emperor guarantees global peace because he alone can bring political pluralism to legal unity – a form of harmony that, according to the framework of De Monarchia, reflects the perfection of the unity of heaven. As the late Paolo Grossi explained,Footnote 46 it is the notion of autonomy, more than sovereignty, that lies at the heart of the medieval universe and its organic pluralism: the emperor lords over a broad constellation of socio-political realities, each subordinated to his authority yet possessing its autonomous juridical status according to the specific role that it plays in society.Footnote 47 The (liberal) distinction between state and society, public and private was yet to come, and the social order consisted of a cascade of loyalties among multiple levels, tied to each other by oaths of allegiance and underwritten by divine justice.Footnote 48 Within the Christian civitas maxima, multiple institutions coexisted that exercised power according to different scopes of authority and thus eschewed the later antithesis between individual freedom and collective order so familiar to modern readers. The relational co-dependency of estates and their equal subordination to the emperor placed significant constraints on the breadth and depth of their prerogatives. Accordingly, they retain a sovereignty of government over their own subjects – dictating suitable laws, administering justly, and adjudicating disputes in their respective communities – but must exercise it considering the general principles mandated by the emperor for the communal purpose of peace. Failing to do so is tantamount to usurping imperial prerogatives, violating their duty of loyalty (fidelitas) to the emperor, and thus disfiguring the divinely ordained order of things.

Kelsen would revisit this question in the face of disputes among modern states. Constituting a major hindrance to the project of legal cosmopolitanism is the sovereigntist belief that, on the chessboard of global politics, two independent states are neither subordinated to each other nor subject to a third, superior authority (à la Hobbes or à la Austin) – or, even more radically, that the factual presence of an international sphere does not necessarily entail the existence of any system of international law since state sovereignty is unreconcilable with willing subjection to a law that is imposed externally. This argument leads states to act as if they were unconstrained in their actions towards each other. For Kelsen, the problem lies precisely in the absence of a third, superior jurisdictional authority that settles interstate disputes impartially, has the authority to impose sanctions, and can ultimately restore justice. From this perspective, Dante believes that it is imperative to have an ultimate – and secular – guarantor of universal peace. The young Kelsen recuperates Dante’s call for an emperor as the supreme authority over partial powers and enhances his jurisdictional role: ‘As the head of his universal peace-making state’, Kelsen writes, ‘Dante pictured the emperor as the supreme judge of peace’.Footnote 49 In fact, global peace requires a global authority with the power to decide, and Dante’s judge-emperor performs precisely this task, in the interpretation by the Austrian jurist:

The emperor stands to the imperium like a judge stands to the jurisdictional power. The imperium is indeed the supreme jurisdictional power (imperium est jurisdictio, omnem temporalem jurisdictionem ambitu suo comprehendens), and the emperor is nothing but its vessel; he is, in fact, appointed to practice it and thus is instrumental to it, not the other way around (ad ipsum Imperator est ordinatus et non e converso) […]. Therefore, any change of this supreme jurisdictional power by the emperor qua emperor – that is, as a vessel of this very imperium - would be totally inadmissible (quod imperator ipsam permutare non potest in quantum imperator).Footnote 50

1.5 Dante and Kelsen on Sovereignty, Law, and Systemic Unity

Sceptics of Dante’s vision and of Kelsen’s sympathetic reading and interpretation might object that it possibly verges on an authoritarian scenario: in the absence of counterweights to his will, the emperor would easily turn from a global ruler into a global tyrant. In anticipation of the hazard of despotic drifts, Dante consistently emphasises that the emperor must ensure and maintain peace according to impartial and neutral standards of justice.Footnote 51 Dante’s emperor is neither an absolute sovereign nor a decisionist president tasked with constitutional guardianship. His power does not coincide with that of the state; he is its mere executor. The sovereign is accountable to standards of natural law that he has a moral duty to observe; he is the organ – and thus the guarantor – of the supreme jurisdictional power, not the source of power itself.

Indeed, the limitation of the emperor’s prerogatives by law represents an important kernel in Kelsen’s exegesis of De Monarchia. He meticulously dissects the poet’s arguments about the illegitimacy of the Donation of Constantine, emphasising how the emperor has no authority to divide the imperiumFootnote 52 (not even when it is meant as a gift to the Church), since such a division would entail its very destruction (cum ergo scindere imperium esset destruere ipsum). Kelsen thus emphasises that, for Dante, the emperor holds a simple officium monarchiae (or officium deputatum imperatori) – in other words, he is ‘employed’ in the service of humanity, for which he is subject to rights and duties: ‘The imperium stands above the emperor; the latter is only a servant, an instrument of the imperium; his position in regard to state power is an office, which certainly authorizes him, but to the same extent also obligates him’.Footnote 53 Already a few pages prior, analysing a passage from Book I, chapter 12 of De Monarchia, Kelsen makes it clear that the sovereign must operate, in Dante’s words, as ‘a servant of the collective’ (minister omnium), appointed for their good and bound by the law (echoing an argument that Dante had already illustrated in Book IV of Convivio). ‘This element’, he notes, ‘reveals the modernity of Dante’s teaching, which is reminiscent of Frederick the Great’s Anti-Machiavel’.Footnote 54

Are there connections between the Dantean and the Kelsenian understanding of sovereignty? Martti Koskenniemi believes that there are. In his classic From Apology to Utopia, he distinguishes two legal approaches to the notion of sovereignty: on the one hand, an early, ‘pre-classical’ doctrine postulated the existence of a set of rights and duties anterior to, and thus with normative priority over, the sovereignty of the prince, setting the perimeter for his liberties and powers; on the other hand, classical lawyers developed a largely opposite vision, making each state’s liberty their starting point and conceptualising interstate conduct as the result of adherence to principles functional to its preservation.Footnote 55 Koskenniemi underscores an affinity between Dante’s and Kelsen’s accounts: in both cases, the legitimacy of action – whether by the prince, the state, or international actors – is given solely by the legal order. However, it is also vital to emphasise a key difference between the two authors: Dante’s concept of law is committed to a substantive theory of natural law, whereas Kelsen claims that positive law can take any content. According to the Austrian jurist, the conditions for the legitimate use of force set by a positive system of international law need not conform to any specific set of a priori moral standards – they are contingent. Importantly, for Kelsen, the construction of a peaceful global order requires overcoming individual state sovereignty in the international arena. Sovereign states, in fact, will inevitably gravitate towards imperialist projects based on the alleged uniqueness of their own jurisdiction and, in turn, the reluctance to acknowledge the validity of other states’ legal systems.

As Kelsen makes clear in his systematic publications, sovereignty is – from the perspective of legal equality among states – nothing but an imperialist dogma that must be eradicated if one is to proceed on the path of universal peace and global legal unity.Footnote 56 This, too, Dante seems to suggest – according to Kelsen – when he entrusts the resolution of disputes among equally sovereign peers to the judge-emperor, who is himself subject to the law. One of the most authoritative references that Kelsen draws upon in his historical-political study of De Monarchia is, in fact, Dante Alighieri’s Leben und Werk (1865) by F. X. von Wegele, who praised Dante’s vision as the ‘Rechtstaat der Menschheit’, the rule of law of all mankind, a cosmopolitan project founded on the values of peace, justice, and freedom.Footnote 57 To pursue this goal, Dante’s world government also sets for itself a ‘cultural purpose’ (‘Kulturzweck’, in Wegele’s words), with ‘Rechtstaat’ and ‘Kulturstaat’ as two sides of the same coin (in Wegele’s interpretation, Dante was among the first medieval thinkers to recognise the idea of the modern cultural state). Critical of Dante’s vision of a ‘Kulturstaat’, Kelsen argues that the author of De Monarchia went too far in defining the teleological character of the state, giving it broader tasks than it should have. Through this critique, it is possible to glimpse the Kelsenian preference for a purely legal definition of the state, understood as Rechtsordnung.

Kelsen specifically addresses the question of sovereignty in chapter 7 of Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri, which is devoted to the relationship between the prince and the people in De Monarchia (‘Fürst und Volk’). Notably, these pages include Kelsen’s very first attempt to think through the concept of sovereignty in his published scholarship, long before his systematic treatment of the subject in Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts (written during the First World War but published in 1920). Accordingly, they retain an important and, thus far, under-appreciated value for anybody interested in a contextual study of the trajectory of Kelsen as a political and legal thinker. Once it is established that, for Dante, imperium is legally constrained and the sovereignty of the emperor is best understood as a concessio ad usum, the question that intrigues the young Kelsen, as a reader and interpreter of Dante, concerns its origin: does the sovereignty of the world ruler emanate from God, or does it stem from the people?Footnote 58

Despite the modernising exegesis proposed by Die Staatslehre,Footnote 59 Kelsen points out that in the context in which Dante was writing – a time when everything was believed to follow a divine plan – the key question was not whether political authority is produced by God but whether secular authorities are subject to the Church and the pope. Theorising the role of the universal sovereign as minister omnium, Dante emphasises that he must respond to the needs of the collective – neither to those of a portion alone nor to his own. According to Kelsen, the poet would even go as far as to theorise a right of resistance on the part of the community in cases of blatant violations of this golden rule.Footnote 60 Unlike the emperor’s, the sovereignty of the law as a global normative code is supreme when it is exercised in the service of the collective. Dante describes it as indivisible, unitary, and inalienable – three qualities that would become a staple of early modern theories of statehood, starting most notably with Bodin’s and Hobbes’, as Kelsen explicitly points out when unpacking the features of Dante’s notion of a global state and anticipating themes that he would develop in his discussion of sovereignty in the final pages of Das Problem der Souveraenität:

Defining this unquestionably modern notion of the state are several important features. First, Dante underscores the unity of state power (imperio in unitate Monarchiae consistente); then he underlies its indivisibility, inalienability, and inability to destroy itself. It is also independent externally, as demonstrated by the rejection of the only possible earthly authority (the Pope’s) over the imperium comprising all kingdoms and countries. The sum of all these attributes of the imperium presents us with that characteristic of state power which modern state doctrine designates as sovereignty.Footnote 61

The connection – indeed, almost the equation – between (global) state and (global) law fascinates the twenty-four-year-old Kelsen. In the fourth from last chapter of Die Staatslehre, he writes: ‘Within the horizon of this conception of the relationship between state and law, the acceptance of a determination of supreme state power by law is natural. To Dante, the fullness of power is legally bound. Its unity, indivisibility, and inalienability are requirements of law’.Footnote 62 As is well known, Kelsen would make the identification of law and state one of the signature elements of his Reine Rechtslehre, detailing that the system of the domestic law of states is partial in relation to the universality of the international legal system.Footnote 63 Drawing new attention to Kelsen’s interpretation of Dante, Koskenniemi has recently stressed the affinities between the two authors in this regard:

The emperor may not work against the law because his very office is constituted by the law and for its realization: ‘all jurisdiction is prior to the judge who exercises it … the emperor, precisely as emperor, cannot change it, because he derives from it the fact that he is what he is.’ Dante had completely accepted—so Kelsen—the Germanic idea of the internal relationship between statehood (in this case imperial statehood) and the law, each constituting and conditioning the other.Footnote 64

In other words, it is possible to suggest that the future Kelsen – that is, the champion of the equivalence of state and law as a legal system – is embryonically present in the early work on Dante, as is the principle of the unity of legal science that would later provide the foundations for Kelsen’s Stufenbaulehre – that is, the systematic account, at the core of the Pure Theory of Law, of a hierarchy of norms wherein those on a higher level authorise the creation of those on a lower level and the Grundnorm at the top guarantees the system’s unity.Footnote 65

Another fascinating element in Kelsen’s first steps as a political and legal theorist is his suggestion that underwriting Dante’s vision is a methodological search for the unity of the system. The imperial ideal of De Monarchia, the young jurist posits, is not the outcome of a blindly ideological stand but stems from a ‘scientific’ argumentation that deduces the need for a world monarchy from its unrivalled ability to ensure peace on a global scale. The young Kelsen appreciates the logical architecture and the emphasis on unity at the core of the medieval world, of which Dante is a distinguished representative: ‘The system of the medieval Weltanschauung had in Dante’s works its most lucid and consequential realization. All the merits of this system, its depth of thought, its rigorously logical coherence stand out clearly in the clear light of a great personality. The whole universe is here ideally reconstructed in a conceptual construction with grandiose architecture’.Footnote 66

These lines reveal that Kelsen had already started thinking about the possibility of developing a coherent logical system free of contradictions as early as 1905. Kelsen’s Dante, as noted by Jochen Von Bernstorff, is driven by the ideal of a unitary system and of a rigid logical consistency that foreshadows that of Kelsen himself.Footnote 67 There are obviously important differences between the two thinkers in this regard. Kelsen sets out to systematically articulate the project of a universal legal community under a binding jurisprudential system; for this reason, he inevitably departs from Dante’s call for a dual-track system of global government, wherein the Church rules over spiritual matters, the state over temporal ones, and both subject themselves to divine lordship. In contrast, the later Kelsen will notoriously defend legal monism, emphasising that there is only one kind of law (positive law), that international law and the multiple state legal systems come together in a unified normative system, and that – as seen before – international law has priority over state law within this monistic framework.

1.6 Kelsen’s Legal Cosmopolitanism and Pacifism after Dante

In 1940, thirty-five years after the publication of his book on Dante, Kelsen fled Europe – specifically Geneva – to rebuild his life and academic career in the United States. The events that had prompted his decision and the ones that he witnessed as an émigré scholar – from the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Cold War, from the Nuremberg Trials to the planning and materialising of the United NationsFootnote 68 – revived his personal and intellectual interest in questions that he already addressed in 1905 through the lenses of De Monarchia, and thus from a more historical and less involved angle. Already throughout the 1930s, while in Geneva, where he had moved in 1933 after being dismissed from his professorship at the University of Cologne, Kelsen had been working and teaching on international law at the Graduate Institute for International Studies (and, concomitantly between 1936 and 1938, at the University of Prague, where he was forced to resign due to growing anti-Semitism). Despite having to quickly learn French for his lectures, he wrote prolifically on the relationship between international law and state law, the nature and challenges of customary international law, and the revision of the Covenant of the League of Nations. In 1934 he published a short study on ‘the technique of international law and the organization of peace’ (in German and French) as well as his monumental Reine Rechtslehre, which devoted significant attention to his theory of international law. However, the transatlantic phase of his life gave renewed impetus to his long-time interest in cosmopolitanism and world peace.

The construction of a peaceful global order by means of international law and organisations, as part of the overall rebuilding of liberal constitutional democracy in the aftermath of totalitarianism, became the signature concern of his American years. In the inaugural Oliver Wendell Holmes lecture seriesFootnote 69 that he was invited to give at Harvard Law School in 1940–1941 (and published in 1942 under the title Law and Peace in International Relations), he pursued two goals. As International Court of Justice Judge Hersch Lauterpacht pointed out in his positive yet critical review,Footnote 70 the first four lectures (‘The Concept of Law’, ‘The Nature of International Law’, ‘International Law and the State’, ‘The Technique of International Law’) offered ‘the most authoritative exposition’ in English of Kelsen’s views on conceptual questions and analytical jurisprudence; the last two lectures (‘Federal State or Confederacy of States?’, ‘International Administration or International Courts?’) zoomed in on more practical issues, calling for an association of states as the first step in the construction of a legal order as well as for an international court of compulsory jurisdiction on all disputes.

In 1944, one year before he became a full professor, Kelsen published Peace through Law, detailing a formula for a pacified world order. Part I of the book pivoted around the creation of a world court authorised to solve international conflicts and ensure peace through ‘individual responsibility for violations of international law’; in Part II, he suggested that individual statesmen take personal responsibility, both moral and legal, for war crimes and other violations committed by their country. The following year, Kelsen published General Theory of Law and State (with the extensive chapter 6 of Part II dedicated to ‘National and International Law’); again in 1945, upon the conferral of his American citizenship, he became legal adviser to the UN War Crimes Commission in Washington, handling technical questions in the preparation of the Nuremberg Trials (some of which he would address in his essay ‘Will the Judgment in the Nuremberg Trial Constitute a Precedent in International Law?’, 1947). Building on these works and tasks, he deepened his interest in the UN as an institution of peace keeping and global cooperation, with a focus on the Security Council and related questions of membership, sanctions, and functions. The result of this research was the 900-page monograph The Law of the United Nations – significantly subtitled A Critical Analysis of Its Fundamental Problems, published in 1950 under the auspices of the London Institute of World Affairs and reissued several times until 1966 (with the inclusion of his 1951 supplement ‘Recent Trends in the Law of the United Nations’) – and eventually the 460-page Principles of International Law, released the year of his retirement in 1952.

Peace through Law specifically exemplified Kelsen’s ability to pursue his own legal vision without losing sight of the complexities and contingencies of political reality. Acknowledging the difficulties involved in the long-term project of a world federation, he opted for a more realistic and shorter-term programme consisting of three steps: a ‘Permanent League for the Maintenance of Peace’ (initially bringing together only the countries that had victoriously fought the Second World War); an International Court of Justice (providing a judicial solution to disputes among League state members); and a police force tasked with the application of the Court’s sentences. While combining elements drawn from Wolff’s Jus Gentium Methodo Scientifica Pertractatum (1749) and Kant’s Zum ewigen Frieden (1795), Kelsen’s proposal offered elements of originality – for instance, the emphasis on the Court as an impartial judge tasked with the neutralisation of international political conflict (a mid twentieth-century equivalent of Dante’s judge-emperor).Footnote 71 As one can observe, the extensive work that the Austrian jurist produced in the aftermath of the Second World War pushed in significantly new directions ideas that he had started considering through the prism of Dante while still a doctoral student.

1.7 Conclusion

In his introduction to the recent collection of essays International Law and Empire. Historical Explorations, Koskenniemi has drawn the attention of historians of legal and political ideas to the importance – historical, conceptual, and normative – of Kelsen’s first book, illustrating the overlooked analogies between Dante’s De Monarchia and the Reine Rechtslehre. He has also underscored the plausible influence that Dante’s call for the unity of humankind – logically derived and hierarchically arranged – had on the neo-Kantian Kelsen. In worlds and eras populated by contending authorities and similarly plagued by endemic conflict, the two authors were driven by a similar project: ‘[l]ike Kelsen, Dante, too, operated his reductio ad unum as a peacekeeping device’.Footnote 72 For both Dante and Kelsen, the empire envisioned and theorised in De Monarchia meant ‘law’s empire’ – that is, primacy of the legal system. It might sound daringly inappropriate to use this iconic formula, considering that Dworkin never subscribed to any view remotely resembling Kelsen’s monism and that his Law’s Empire systematised his critique of Hart (a towering figure – just like Kelsen – in the geography of twentieth-century legal positivism). However, it might not be entirely inappropriate to suggest that the young Kelsen – as a reader and interpreter of Dante – precociously combined the skills of both Judge Hermes and Judge Hercules – the two ideal-types of jurists at the core of Dworkin’s 1986 volume: on the one hand, attention to historical context and respect for original legal meaning, mediating – just like the God Hermes – between past and present, between the dead and the living; on the other, the surprising ability, at the age of twenty-five, to undertake the Herculean task of dissecting the architectonics of De Monarchia, thinking through and beyond Dante’s philosophy of the state while also laying the groundwork for the intellectual project of a lifetime.

2.1 Introduction

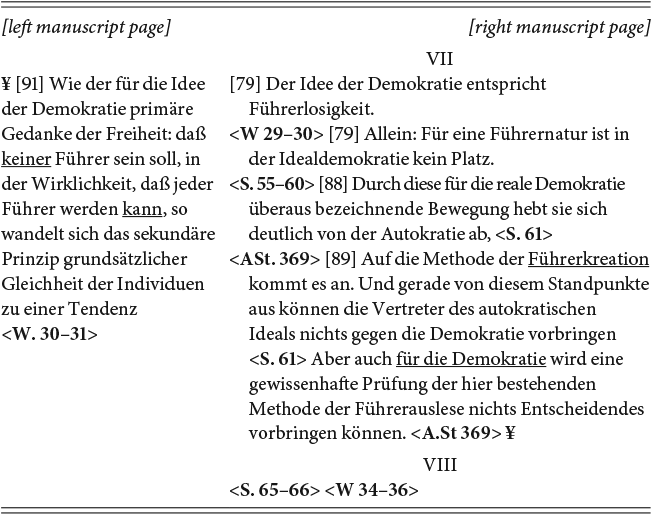

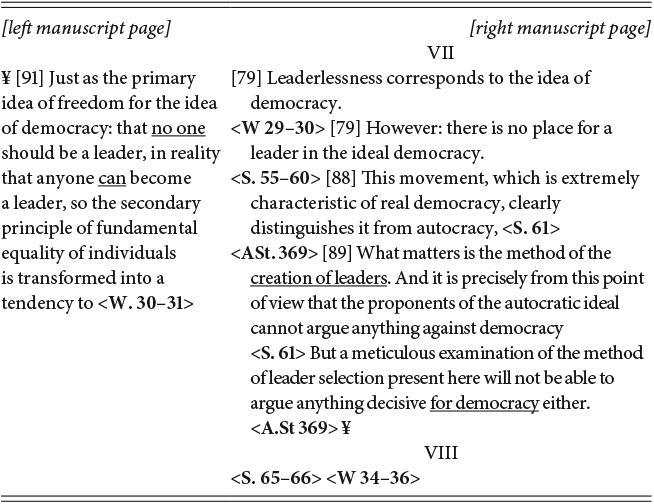

The political theory of Hans Kelsen, developed during the 1920s and early 1930s, represents a sustained attempt to provide a coherent theory of constitutional multiparty democracy for European interwar democracies.Footnote 1 Kelsenian political theory arose in the particular context of the creation of the Austrian First Republic, as a constitutional multiparty democracy, resulting from the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919).Footnote 2 This was combined with the debate, within Austrian social democracy over the character of the new state and the form of state intervention in its economy.Footnote 3 Thus, from its inception, Kelsenian political theory is distinguished by the elaboration of a theory of constitutional multiparty democracy that explicitly articulated itself within and against the wider political dynamics of this European interwar period.

The gradual weakening of European interwar democracies and, in particular, the transformation of a significant proportion of the democracies created after the end of the First World War into nondemocratic regimes during the 1930s, revealed the fragility of European interwar democracy. This fragility, which marked the conclusion of Kelsen’s political theory of this period, was not, however, unacknowledged by Kelsen.Footnote 4 It is a fragility that is specifically thematised by Kelsen in ‘La dictature de parti’ (1935).Footnote 5

It is this work of Kelsen that is the initial, detailed focus of the chapter in order identify the distinctively Kelsenian understanding of the underlying fragility of interwar, multiparty democracies and the capacity for this fragility to enable their internal transformation into a one-party state: the party dictatorship. The initial focus upon the distinctive Kelsenian thematisation of the fragility of interwar democracies is then broadened through a comparative examination of the contemporaneous early work of Franz Neumann, The Rule of Law: Political Theory and the Legal System in Modern Society (1936).Footnote 6 Neumann’s approach, in distinction to that of Kelsen, situates the origin and fragility of interwar democracy in a broader historical and conceptual analysis of the emergence of the notion of the Rechtstaat and the fragility of the Weimar Republic, as a social Rechtstaat, as the basis for the installation of the one-party state under National Socialism. The comparative examination enables the critical reflection upon the Kelsenian approach to be compared with that of the early work of a later member of the Institute for Social Research (Frankfurt School) and to establish the degree of affinity between these two critical reflections and their respective conceptual frameworks.Footnote 7

This comparative examination emphasises that for both Kelsen and Neumann, the collapse of the interwar democracies revealed a fragility in democracy that is to be comprehended as extending beyond the confines of a strictly historical or conjunctural approach. Democracy, in the form of a representative democracy composed of political parties, includes rather than excludes fragility. Thus, in representative democracy, there remains an inherent fragility whose exacerbation and limitation become the common focus of their critical reflections.

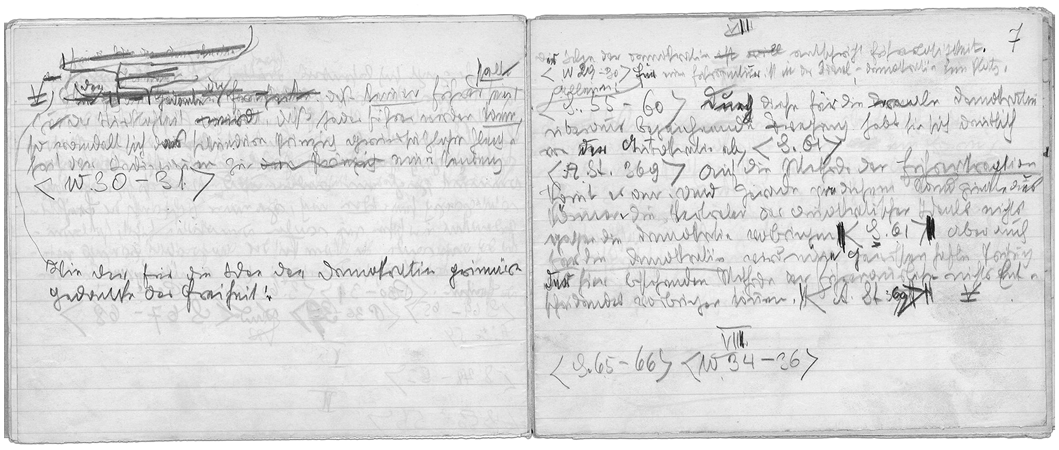

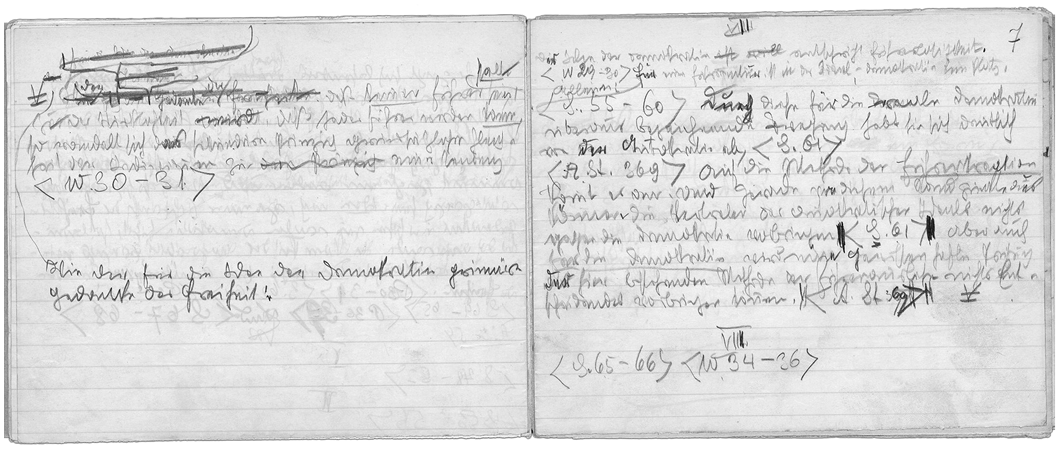

2.2 Kelsen: From Democracy to Autocracy

Kelsen’s ‘La dictature de parti’ (1935), presented as a report to the Institut International de Droit Public, was conceived from its inception as an explication of the gradual weakening of European interwar democracies and their increasing tendency to transform into nondemocratic regimes.Footnote 8 As a report, the format of the analysis presumes a position of detached explication, which, therefore, intersects with a broader methodological orientation. This approach is predicated upon ensuring the detachment from the recourse to or assertion of values in the analysis, which are designated as inherently subjective, in order to commence from a non-subjective foundation. The Kelsenian analysis commences not from democracy as the assertion of a subjective value but from the non-subjective foundation of democracy as the existing system of European, interwar multiparty democracy. From this foundation, the analysis then focuses upon instances where this form of multiparty democracy has been transformed into a party dictatorship.Footnote 9 Hence, it traces the internal transformation of an existing political system, and it is the description and characterisation of this transformation that provides the explication of the fragility of European interwar democracy.

The existing political system of European interwar multiparty democracies was characterised by the formation of a common willFootnote 10 from ‘the free play of different groups of interests constituted by political parties’.Footnote 11 The will of the democratic state arises solely from the formation of this common will, and it is formed through a procedure of democratic will formation in which the opposed interests of political parties are reconciled, and in this reconciliation, the common will is generated as a process of compromise. The state, as a democratic state, is distinguished by its procedure − the creation of commonality from the plurality of opposed interests of the political parties − which rests upon the continued reproduction of compromise. It is the fragility of this procedure − the absence of compromise and the assertion of the interest of a particular party as the common will − which, for Kelsen, contains the ‘risk of transformation into its opposite, into autocracy’.Footnote 12

The risk, rather than the expression of a merely conceptual possibility, is held to have had its initial, contemporary realisation in the ‘new form’ of autocracy resulting from the ‘socialist revolution which broke out in Russia, following the [first] world war’Footnote 13 and its opposed analogue of Italian fascism.Footnote 14 The designation of these two opposed party dictatorships, as Bolshevism and fascism, had by the 1930s, ceased to be confined to a particular state; each had become a ‘generic term’ describing the existence of the dictatorship of the proletarian party and the dictatorship of the bourgeois party, respectively.Footnote 15 Thus, the party dictatorships, in the form of the autocratic regimes in Russia, Italy, and Germany, become the subject of a descriptive explication that has a wider heuristic purpose: a typology and differential categorisation of modern autocracy in comparison with the political system of European interwar multiparty democracy.Footnote 16

The transformation of a political system of multiparty democracy into the dictatorship of a single party involves the forcible seizure of power by one party, the subsequent exclusion and suppression of all other existing political parties and the prevention of the organisation of new parties.Footnote 17 The capacity of this party to seize power requires that it has itself, within the framework of the preceding multiparty democracy, already undergone a preparatory transformation. The forcible seizure of power requires that the party has the capacity to exercise military force.Footnote 18 The further process of transformation is therefore differentiated by whether the seizure of power is the result of a revolution − Russia − or of an effective transfer of power by the existing institutions of the democratic political system − Italy and Germany.

The forcible transformation is accompanied by the complete disappearance of ‘the clear separation, characteristic for democracy, between the organization of the parties and the organization of the state’.Footnote 19 The organisation of the party which has assumed the position of a party dictatorship extends to the conferral of ‘state posts of any importance’: the party dictatorship creates a state party in which ‘the organization of this party is the sole determinant of the will of the state’.Footnote 20 The character of this organisation differs in accordance with the degree to which ‘the preceding formal organization of the state finds itself subordinated to the organization of the party’.Footnote 21 Russian Bolshevism engaged in a complete subordination of this preceding formal organisation to the party, distinguishing it from the ‘juxtaposition’Footnote 22 of the preceding formal organisation of the state and the party under Italian and German fascism. The primacy of the party, under Italian and German fascism,Footnote 23 was ensured by the dual role of the leader as both party leader and leader of the government − a unity of state and party through ‘personal union’.Footnote 24

These two typologies of subordination are then reflected in the approach to the preceding juridical organisation of the multiparty democracy as a constitutional order. The underlying commonality of the three-party dictatorships was to render their transformation of the preceding constitutional order − republican (Russia, Germany) or constitutional monarchy (Italy) − into an empty juridical form. The preceding constitutional order was retained as a façade for the organisation of the party and its ‘possibilities for expansion’.Footnote 25 The differentiation between the three-party dictatorships is drawn between that of Russian Bolshevism, whose constitutional façade was produced through the abolition of the preceding constitutional order and the promulgation of a new constitution,Footnote 26 and that of Italian and German fascism, whose constitutional façades involved the preservation of significant aspects of the preceding constitutional order.Footnote 27

The hollowing out of the juridical character of the constitutional order, within which the party dictatorship determines and exercises the will of the state, is the corollary of ‘the total suppression of political and personal liberty’.Footnote 28 The liberty of European interwar democracy, differentiated into political and personal spheres, is to be understood in the specifically Kelsenian sense of types of liberty which arise through their expression as legal norms of positive law within the particular domestic legal system of each European interwar democracy. The normative framework of positive law, which expresses these liberties guarantees the domains of political and personal liberty and, through this guarantee, prevents the institutions of the democratic state and the political parties from encroaching arbitrarily upon these domains. The guarantee is that provided by an entirely positive system of legal norms, which is neither the state’s self-delimitation, created by a state sovereignty which precedes the law, nor the translation of a preceding subjective right into an objective system of legal norms.Footnote 29 These domains of liberty, as demarcated by the legal norms of an autonomous legal system of positive law, are situated beyond the dualisms of state and law and subjective right and objective law. The transformation into an autocratic nondemocratic political system is the suppression − overt abrogation or loss of practical effect − of these legal norms of positive law.

Within this suppression of political and personal liberty, Kelsen considers that the primary focus of active suppression is upon political liberty, with a more differentiated approach to personal liberty. The suppression of political liberty and, in particular, that of political participation as a member of other political parties who, in turn, are elected through a process of universal suffrage is undertaken through the substitution of the dictatorship of one party. The party dictatorship, should it decide to preserve or maintain a legislative body, ensures that it is composed either ‘exclusively, or in an overwhelming majority’Footnote 30 of the members of its party. Political participation and a process of election are replaced with the prerequisite of membership of this one party and the reduction of the process of election to one of the selection and nomination of party members or those considered loyal to the party. The notion of democracy is thereby either rendered merely ideological or entirely eliminated. Under Bolshevism, in which the party dictatorship was presented as the representative of a class − the proletariat − which ‘aims at the suppression of class oppositions and consequently as the establishment of prefect freedom’, democracy ceased to be a political system and has become ‘a collective ideal’.Footnote 31 Under fascism, in both its Italian and German variants, democracy was entirely eliminated and replaced with the party dictatorship as ‘representative of the entire people unified in the nation’.Footnote 32 Insofar as the fascist party dictatorships sought to retain and present the appearance of consent, recourse was made to plebiscites. The further distinction between the Italian and German variants is, for Kelsen, German fascism’s adoption of racism as an integral element in the determination of the unification of the nation.Footnote 33

In relation to personal liberty, Kelsen considers this from the perspective of those elements of this liberty which comprise ‘the freedom of mind essential to every democracy’.Footnote 34 Here, the mind should be understood non-metaphysically as the potential for an individual’s formation of sense, meaning, and value and for its further development and expression as individual and public opinion. It is public opinion which surrounds the formal space of multiparty democracy, and it is their reciprocal interaction which shapes the political programme and interests represented by each party, the operation of universal suffrage and the selection of the party or parties of government or opposition − and, more indirectly, the character of the compromise, which determines the common will of the democratic state. The suppression of these elements thus concerns the freedom of expression in the form of freedom of the press and freedom of opinion.Footnote 35

In contrast, the freedom of religion is, for Kelsen, comparatively less affected.Footnote 36 For Bolshevism, it entailed, in place of simple legal prohibition, the privatisation of religion − the separation of a secular, atheistic one-party state and its institutions from religion.Footnote 37 For fascism, in both its Italian and German variants, an explicit, formal accommodation with religion, in the form of Christianity, was established. Christianity and its religious observance and practice were tolerated insofar as they acknowledged and supported both fascist party dictatorships. This acknowledgement and support, in relation to German fascism, were also predicated upon the acceptance and active articulation of the party dictatorship’s antisemitism.Footnote 38

This suppression, by the party dictatorships, of the space of political and personal liberty of European interwar multiparty democracies had a concomitant effect upon the formal, legal equality of those within these states, which were transformed into party dictatorships. The effect was one of the dissolution of this formal, legal equality and its replacement with generalised legal inequality: the reduction of rights to a hierarchy of statuses combined with the continued capacity for their reduction or removal and, within this hierarchy, the designation of individuals or groups with no status.Footnote 39

The imposition of generalised legal inequality was accompanied by an insistent attempt to attain a degree of equality in the form of ‘a uniformity of mind’, in which Bolshevism and fascism differed only in their ideological orientation of this uniformity.Footnote 40 The uniformity of mind is reinforced by the primacy accorded within and beyond the institutions of the party state to the ‘principle of authority’, with the attendant emphasis upon the ‘duty of discipline and blind obedience to superiors’.Footnote 41 This, in turn, has a wider effect upon schooling, higher education, and the freedom of scientific inquiry, particularly in the social sciences, which are all now organised and directed to ‘blindly serve the interest of state power’.Footnote 42

The central divergence between the two types of party dictatorship centred upon their approach to the material equality of their populations after the transformation of their preceding democratic political system. This resulted from the divergent character of their relationship to the economy and ‘the opposition between the socialist economic order which Bolshevism strives to realize and the capitalist economic order which fascism endeavours to maintain’.Footnote 43