The personalization of politics refers to the process in which the political role of individual actors gains importance at the expense of political groups over time (Rahat & Kenig, Reference Rahat, Kenig, Rahat and Kenig2018). This process has major implications for the way political representation works. A centralized process of personalization entails that party leaders gain importance over time, which can lead to a ‘presidentialization’ of politics where the prime minister gains more autonomy over the prime minister's party and cabinet (Poguntke & Webb, Reference Poguntke and Webb2005). Decentralized personalization revolves around individual politicians instead of their leaders (Balmas et al., Reference Balmas, Sheafer and Shenhav2014). This process shifts the focus of representation from being party‐based to being more trustee‐ or delegate‐based (Önnudóttir, Reference Önnudóttir2016). Specifically, decentralized personalization entails politicians becoming less partisan, because their personal features gain importance at the expense of their party, and it is likely to result in more delegate‐based representation when district voters are the gatekeepers of political careers.Footnote 1

Decentralized behavioural personalization can thus be expressed as a strengthened linkage between voters and individual politicians. A more personalized linkage may be revealed in the behaviour of politicians (trying to cultivate a personal reputation among voters) or in the behaviour of voters (motivating politicians to cultivate a personal reputation by factoring them into their vote choice). Yet, decentralized personalization occurs in more arenas than just the behavioural. It also occurs, for example, in media coverage of politics and in institutional reforms (Rahat & Sheafer, Reference Rahat and Sheafer2007). These different types of decentralized personalization are generally believed to interact with each other. In particular, a highly prominent and long‐standing argument in political research is that more personalized electoral systems – that is, electoral systems with more candidate‐centred (s)election rules – lead to more personalized behaviour among politicians (André et al., Reference André, Depauw and Martin2015; Bräuninger et al., Reference Bräuninger, Brunner and Däubler2012 Friedman & Friedberg, Reference Friedman and Friedberg2021; Carey & Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995; Itzkovitch‐Malka & Hazan, Reference Itzkovitch‐Malka and Hazan2017; Rahat & Sheafer, Reference Rahat and Sheafer2007; Shomer, Reference Shomer2016) and voters (Chiru, Reference Chiru2018; Dodeigne & Pilet, Reference Dodeigne and Pilet2021; Shugart et al., Reference Shugart, Valdini and Suominen2005; Söderlund, Reference Söderlund2016).

Yet, demonstrating a causal relationship going from electoral systems to behaviour is challenging. One approach in the literature reviewed above has been to cross‐sectionally compare the degree of behavioural personalism between different politicians and voters who face different electoral rules at one point in time. However, causation inherently suggests that changes in electoral rules over time (i.e., personalization of the electoral system) should be followed by changes in behaviour over time (i.e., behavioural personalization), and this is difficult to assess in a strictly cross‐sectional analysis. Another approach has been to analyze whether country‐wide electoral reforms are associated with behavioural personalization. This design clearly includes a temporal component, but it still leads to selection bias if the same unobserved variables that result in personalization of the electoral systems also result in behavioural personalization. For example, the personalization of politics in each arena could potentially be a function of broader structural changes. Indeed, some view the personalization of politics as an overall process of individualization in society where group membership becomes less important (Bennett, Reference Bennett2012; Karvonen, Reference Karvonen2010). This process of societal individualization could both lead to the adoption of personalized electoral rules and to personalized political behaviour, and at different speeds in different countries, regions and parties. The resulting statistical association between candidate‐centred electoral reforms and behavioural personalization would be positive, but not a function of a direct causal relationship.Footnote 2

The purpose of this paper is to adjudicate between these different possibilities. Specifically, we ask: What happens to the relationship between electoral systems and behaviour when we can account for the most likely sources of selection bias? We do so by using a unique variation in electoral rules within subnational elections in Denmark from 2005 to 2021. In these elections, some candidates are elected on open lists, while others are elected on de facto closed lists (Tromborg, Reference Tromborg2021).Footnote 3 Furthermore, the list types vary within local party organizations over time. This makes it possible to isolate the relationship between electoral rules and behavioural personalization while accounting for systematic differences between parties, districts and voters that could lead to selection bias. Furthermore, we can control for broader national individualization trends using time fixed effects.

The design does not eliminate selection issues completely. We cannot account for changes that occur within local parties between elections, and these changes may be important for determining both the choice of electoral rules and observed behaviour. However, our design substantially reduces the magnitude of possible selection bias compared to previous studies by allowing us to simultaneously control for the most likely sources of such bias – namely, features of the parties involved, the districts where the elections take place and the national political context in different time periods. In other words, if there is a statistical association between electoral rules and personalized behaviour – as opposed to a direct causal relationship – because certain parties, districts or time periods are characterized by a more individualized culture, then the association should disappear once we control for these three variables.

Using data on voters’ personal preference votes and political candidates’ public position taking in a Voting Advice Application (VAA), we replicate the long‐standing result that more candidate‐centred electoral rules are associated with behavioural personalism and personalization when we make simple uncontrolled comparisons of politicians and voters in different districts and over time. However, when we make more controlled comparisons with fixed effects, the association disappears. Put differently, when we take the most likely sources of selection bias into account, we find no evidence that candidate‐centred electoral rules lead to behavioural personalization. This suggests that the personalization of electoral systems is a symptom of broader individualization trends rather than a root cause of behavioural personalization. The factors that lead to behavioural personalization seem to also lead to candidate‐centred electoral rules. While we do not mean to suggest that institutions never matter – we think they often do – this indicates that we need to look beyond electoral systems if we want to fully understand why behavioural personalism and personalization occurs among voters and politicians.

Empirical context

Our empirical focus is local governments in Denmark, a decentralized welfare state where local public spending comprises about a third of GDP. Local governments are run by city councils that are elected every 4 years. Elections are high‐stakes affairs with a 70 per cent turnout and only a moderate degree of nationalization in election outcomes (Hjorth & Hopkins, Reference Hjorth and Hopkins2022). The electoral system is proportional with one multi‐member district per municipality, and district magnitude varies from 9 to 55. Local elections are dominated by nationally competitive parties that receive 90 per cent of the votes. We focus our analyses on the nine nationally competitive parties (defined as parties who had representation in Parliament between 2005 and 2021). We therefore omit smaller parties that only run in one or a few municipalities. To distinguish the national party organizations from their local organizations (including the local candidates), we use the term ‘local party’ to describe the latter. Ideally, we would also have wanted to include non‐national parties, at least for comparison. However, there are both conceptual and data issues, which make these parties difficult or impossible to include. First, these parties do not have a strong national reputation that local candidates can defect from. Second, there is limited data on these parties. While Statistics Denmark publishes detailed local election results for the national parties, they do not separate out votes for non‐national parties. As we use this data for one of our two dependent variables, it would not be possible to consistently include them.

Voters in Danish elections cast a single vote and have the option to choose either a party list or a specific candidate on a party list. Seats are first assigned to party lists using a proportional divisor method. Seats are then assigned to candidates in one or two ways. If the local party uses an open list, then the seats cast for a party go to the candidates from this party who received the most preference votes. If local parties run on a flexible list, then the party has set a preference for which candidates it prefers, and the seats assigned to the party go to those who are highest on this list, unless a candidate reaches the personal vote threshold for breaking the party's list (e.g., if there are 20 seats in a district, then a candidate needs 5 per cent of all votes). This threshold is extremely high, which is why the flexible list option can be classified as a de‐facto closed list. In fact, from 2005 to 2021, the period we study, it did not happen once. Crucially for our purposes, parties can (and often do) change list types from election to election. By studying the effect of electoral rules at the local government level in Denmark, we can thus analyze within‐party, within‐district and over‐time variation in how personalized the electoral rules are.

To be sure, this design does not work if party leaders choose the list based on the pre‐existing degree of personalism among their candidates or voters. This is unlikely to be a major concern in the Danish case. The rules for choosing the type of local party list are generally inclusive, meaning that the institutional choice is typically a function of the collective preferences of the regular dues‐paying members from the local party. Such local party members are less likely than party leaders to act strategically (May, Reference May1973). It is also worth mentioning that there has been a clear pattern of electoral system personalization in local Danish politics. Since the open list was introduced in Danish elections in 1985, its popularity has steadily increased from 48 to 80 per cent in 2021 (as indicated in Statistics Denmark's periodical Statistical Information on Population and Elections)Footnote 4. Given that regular party members make the electoral rule choice within their local parties, this development is consistent with the idea that the individualization of society at large is driving the personalization of electoral rules (and, possibly, also behavioural personalization).Footnote 5

Finally, it can be argued that the Danish case is a most likely case for observing effects of electoral rules on behaviour, but this is actually not entirely clear. On the one hand, some theoretical models (e.g., Carey & Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995; Farrell & McAllister, Reference Farrell and McAllister2006) suggest that Denmark should be considered a most likely (or at least a highly likely) case because open list multimember districts should be characterized by a higher degree of personal vote‐seeking incentives (and hence personalism) than single member districts, and closed list multimember districts should be characterized by the lowest possible degree of such incentives.Footnote 6 If this is true, then the largest possible effects should be present in the Danish case if personalization of electoral rules does, in fact, influence behavioural personalization. On the other hand, there is other research suggesting that single‐member districts provide the highest possible degree of personal vote‐seeking incentives (e.g., Tromborg & Schwindt‐Bayer, Reference Tromborg and Schwindt‐Bayer2022), and single member district elections do not occur in Danish politics. Whether or not the Danish case is a most likely case, we consider it a useful case because of its unique variation in electoral rules and available data sources to measure behavioural personalism and personalization for a large number of observations.

Research design and data

We construct a panel dataset that combines data on the electoral rules that each local party used in past elections and data on behavioural personalism and personalization among political candidates and voters. We omit elections from before 2005 because of a large municipal reform that amalgamated a large number of municipalities. This gives us 4,411 local party‐year observations from 2005 to 2021. We explore the relationship between personalization of the electoral system and behavioural personalization among voters and candidates using a series of local party fixed effects models. This allows us to test whether candidates from, and voters of, a local party changed their behaviour if the party switched from a flexible to an open list (or vice‐versa) between elections. Data on electoral rules were found in Statistics Denmark's periodical Statistical Information on Population and Elections, which can be downloaded from https://www.dst.dk/en.

Our first dependent variable measures political candidates’ efforts to distinguish themselves from their party's issue positions (i.e., personalism and personalization at the level of politicians). To measure the positions of candidates and parties, we take advantage of the fact that a major independent Danish political news website (www.altinget.dk) issued a candidate Voting Advice Application (VAA) during the 2013, 2017 and 2021 municipal elections. Candidate VAAs are online surveys in which candidates running for an election are asked to position themselves on a number of relevant political issues, usually on a 1–5 or 1–4 Likert response scale.Footnote 7 Afterwards, voters can go online, position themselves on the same issues, and receive a candidate recommendation based on their issue congruence with their district candidates. The candidate responses allow us to obtain a comparable measure of candidate divergence from the party's typical response for all candidates who participated in the VAA. This includes responses from 13,436 candidates, corresponding to roughly 70 per cent of all candidates.

We use these candidate positions to operationalize the first dependent variable in three different ways. The first operationalization relies on the party's modal candidate position to a VAA issue as the typical party position. Specifically, we calculate the average distance between a local party's candidates to the party's modal answer for each VAA issue and then generate a mean deviation score for each local party across issues. One disadvantage of this operationalization is that on the few issues where a party's candidates are polarized, the party's modal response might not be much more typical than a non‐modal response. To account for this, our second operationalization follows the same procedure, but uses the party's mean position as the typical party position. Our third operationalization follows the same procedure as the second, but uses the local party's average position as the typical party position. Candidates who did not respond to the VAA are treated as missing (i.e., they do not count toward a local party's divergence score, and they are omitted from the candidate‐level analyses reported in Table 2). The three different operationalizations return similar results as shown in Table 1 and Table 2 below.

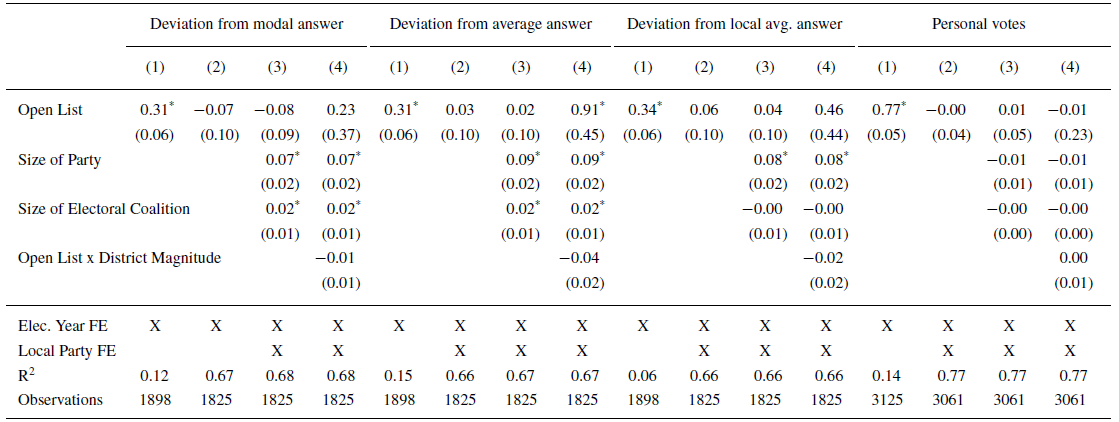

Table 1. The effect of electoral rules on personalization

Notes. Local party clustered standard errors in parentheses. See section ‘Research design and data’ for details on the dependent variables.

* p < 0.05

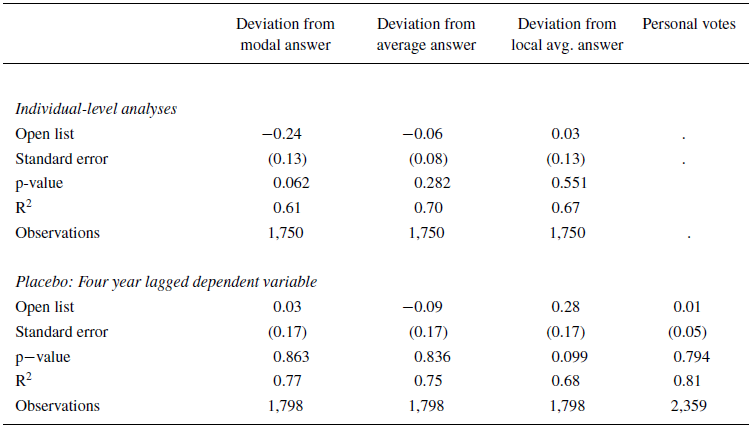

Table 2. Is the null effect of electoral rules robust?

Note. Local party clustered standard errors in parentheses. See section ‘Research design and data’ for details on the dependent variables. All models include Local Party and Election Year FE.

Our second dependent variable tracks whether voters’ factor individual politicians into their vote choice. We measure this as the proportion of all votes for a local party that are candidate preference votes in a specific election. This tracks behavioural personalism and personalization among voters because it reflects whether voters see politics mostly as competition between parties (if they only place a party list vote), or whether they also condition their vote on individual politicians within parties (if they vote for an individual candidate on a party's list). The data on candidate preference votes is from the Danish Electoral Database, which provides data coverage for all five elections in the period from 2005 to 2021. Summary statistics are provided in the Supporting Information Appendix A.1.

Results

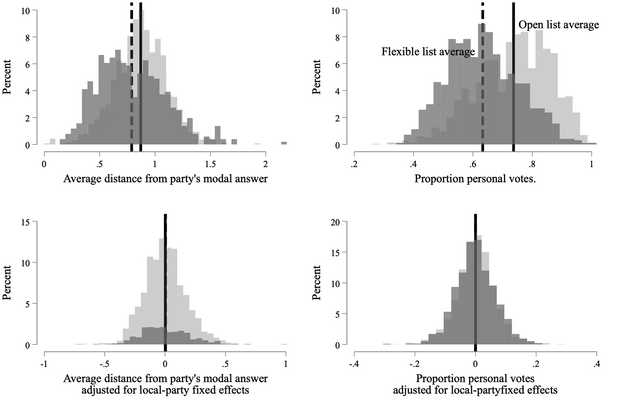

Figure 1 shows how our two indicators of personalism and personalization are distributed for parties that run on open and closed lists, respectively. Observations are at the local party level, and we use deviations from each party's candidates’ modal answer to measure deviations from the party's policy platform (i.e., our first operationalization of local candidate divergence from the party). Consistent with previous research, we find that candidates who run on an open list distinguish themselves more when we make uncontrolled comparisons (top panels) and that voters are more likely to pay attention to individual candidates on open lists. However, once we take district and party type into account using local party fixed effects (bottom panel), there is practically no difference in behavioural personalization for candidates or voters in open versus flexible list contexts.Footnote 8 In other words, the differences in and personalization among candidates and voters are not driven by personalization of the electoral rules, but by underlying differences between parties and districts. We speculate more about what these differences might be in the concluding section.

Figure 1. Electoral rules and behaviour among candidates and voters.

In Table 1 we present the results from a set of linear regression models, which estimate the effect of party list type on our different operationalizations of personalism and personalization. We estimate this model using ordinary least squares, clustering the standard errors at the local party level. To ease interpretation, all dependent variables have been standardized to have a standard deviation of 1. This means that regression coefficients can be interpreted as the standard deviation change in the dependent variable (e.g., number of personal votes cast) associated with a change from a closed to an open list.

In column one, we present results from models with only time‐period fixed effects that do not take differences between districts and parties into account. This is not sufficient to make the association between electoral rules and behaviour disappear. However, after adding local party fixed effects in the second column, we find no evidence of such effects. The estimated effect for personal votes is the most precisely estimated, and here, the 95 per cent confidence interval excludes an effect of running on an open list that is higher than 0.1 standard deviation of personal votes. For our modal deviation measure, the 95 per cent confidence interval excludes an effect that is higher than 0.15 standard deviations. This suggests that the difference identified in the bivariate models is a result of some form of selection into which local parties adopt closed or open electoral rules. Of course, there are still factors we cannot control for, namely factors that vary within local parties over time. This is a shortcoming of this observational study; however, we can control for some factors. In Table 1 we therefore also present a model which controls for party size and the size of the electoral alliance the party is a part of.Footnote 9 However, this has no impact on the results.Footnote 10

In evaluating these results, it is important to note that the basic inferential strategy in this paper is not to rely on observable control variables but instead to use a fixed effects approach. This means that we effectively control for all time‐invariant observable and unobservable characteristics at the municipality and party level. Variables such as party type, municipal size and district magnitude are all controlled for by design, because they do not change from election to election. This does not mean that these variables are not important, nor that they are not relevant control variables. However, we cannot include them as control variables, because they are already taken into account by the fixed effects.

Even if factors such as district magnitude cannot be confounding our results, they may moderate the effect of list type. This might be the case if our null effect is masking a positive effect in places where many candidates are competing for attention. This would be in line with some prior research, which suggests that district magnitude could moderate the effect of list type on decentralized behavioural personalization at both the candidate and voter levels (Carey & Shugart, Reference Carey and Shugart1995; Shugart et al., Reference Shugart, Valdini and Suominen2005). To explore this contention, we include an interaction between list type and district magnitude in the final column of Table 1. However, we find no consistent evidence of such an interaction effect, suggesting an absence in the effect at both high and low levels of district magnitude.

Robustness checks

In Table 2, we also re‐estimate these models at the individual level, substituting the local party fixed effect for an individual fixed effect. This means we cannot analyze the personal votes variable which we only have at the local party level, but we can look at individual candidate deviations from the party platform as recorded in the VAA. Specifically, we can identify 875 candidates who ran in 2013 and 2017 for parties that changed from open to flexible lists or vice versa. In line with the previous models, we find no evidence of party list type effects once we take differences between candidates into account.

Table 2 also reports the results of a placebo test. Specifically, we predict personal votes and deviations from the party platform in the past (4 years ago) using present electoral rules. This placebo helps us rule out that parties go from closed to open list in response to personalization (i.e., reverse causality). That is, one reason we might not identify an effect of changes from a closed to an open list, is that parties only do it in response to an election where their politicians are charged with being too much alike and do not get any personal votes (or, conversely, that local parties shift to a closed list when they determine that there is too much deviation from the party line). If this was the case, it might look like there is no effect on personalization, but that is because parties offset low personalization by going from closed to open lists. Our placebo suggests that this is not the case. As can be seen from Table 2, the estimates are close to, and statistically indistinguishable from, zero. There is no indication of reverse causality.

Conclusion

Using municipal level data from Denmark with important variation in list type, this research note has analyzed the long‐standing argument in institutional research that personalization of the electoral system leads to decentralized behavioural personalization among voters and politicians. The results suggest that – at least in the Danish case – the relationship is an artifact of selection bias; institutional decision makers select open party lists in contexts where the political environment is also favourable towards behavioural personalism. Yet, when the same candidates and voters go from a flexible to an open list, behavioural personalization does not follow, nor the other way around.

These results indicate that to fully understand behavioural personalization, we need to move beyond focusing on the role of electoral systems. That is not to say that electoral rules do not matter. Other rules, such as district magnitude or candidate and leadership selection rules, may very well shape relationships between voters and their representatives – and personalization of the electoral system could lead to behavioural personalization in other national contexts than the one we study. Furthermore, it is possible that informal institutions within parties matter as well (e.g., the norms surrounding party discipline and unity). Additionally, while our design accounts for cross‐sectional sources of bias as well as national time trends, we are not able to account for strategic and non‐strategic events that occur within local parties between elections. That being said, the results should urge us to be cautious in interpreting simple associations between electoral systems and behavioural personalism and personalization as direct evidence of a causal relationship.

If personalization of electoral rules is not the only, and perhaps not even the most important, determinant of behavioural personalization, then what are the other key sources? Karvonen (Reference Karvonen2010, p. 4) argues that ‘… the personalization of politics may be viewed as part of an overall process of individualization of social life’. This is an interesting thesis, which suggests that different types of political personalization are a function of broader cultural changes to society, which are also likely to happen at different speeds in different countries, regions and for different groups. If true, this would explain why the statistical association between electoral rules and behaviour disappears once we control for national time trends (using election year fixed effects in a single country) as well as for regions and party groups (using local party fixed effects). Yet, whether this explanation is, in fact, true is an empirical question, and we believe that an important goal for future research should be to disentangle precisely what the societal changes are that do (and do not) result in different types of personalization. One potentially useful way to achieve this goal would be to use process tracing in cases that are typical of both personalization of the electoral system and of behavioural personalization to help understand the mechanisms behind these developments.

Acknowledgements

For valuable feedback the authors would like to thank Helene Helboe Pedersen as well as panel members at the 2021 ECPR workshop on VAA's. We would also like to thank Jacob Nyrup for sharing data from the 2013 VAA.

Data Availability Statement

Data and the reproducible code for the analysis are available on OSF Registries through the following link: https://osf.io/hnbjq/.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: