Introduction

Should we view the environment as a political issue? We live in a world where depoliticization is increasingly championed, while politics is increasingly equated with acting in a way that is ideologically driven, blinded by beliefs, not guided by facts or science. Politics is regarded as a negative, an adversary to the social order (Felli, Reference Felli2015; Turhan & Gündoğan, Reference Turhan and Gündoğan2017). Reflecting this, there is an intense debate among environmentalists about whether technological change and market mechanisms are enough to repair environmental damages or whether we should aim for more comprehensive reordering, including radical shifts in production, consumption and finance (Clapp & Dauvergne, Reference Clapp and Dauvergne2005). Technocratic environmentalists, who rely on scientific and technological expertise to find solutions to global and local environmental challenges, call for keeping the politics out of the environment. They argue that science and technology should be the only basis for environmental policy-making and demand the use of data-driven policies and expert opinions to guide resource management. Others, however, hold that this sort of environmentalism is a neoliberal trap, pre-determining what environmental decisions can be taken and by whom (Accetti, Reference Accetti2021; Newell, Reference Newell, Scoones, Leach and Newell2015). It is contended that depoliticization of the environment and the weak representation of environmental issues in parliaments impede the growth of local environmental movements and their convergence into larger social movements (Özen, Reference Özen2018).

Like health, migration, and economics, the environment is one of the areas in which depoliticization is most clearly manifested (Meyer, Reference Meyer2020). With an understanding of politics as extending far beyond the activities of political parties and actions in parliamentary spaces, this research asks representatives of the environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) in the Aegean region of Turkey if they view the environment as a political issue and sought out their perceptions of the nexus between the environment and politics.

The data were collected through an online survey sent to ENGOs in the Aegean region of Turkey. Turkey was chosen as a case study because the country’s neoliberal transformation has been loaded with environmental conflicts (Adaman et al., Reference Adaman, Akbulut and Arsel2017). As a country with a semi-peripheral economy (Wallerstein, Reference Wallerstein1976), whose economic growth engine is tied to often controversial construction and energy projects, the struggle to defend life spaces, ecology, and small livelihoods spans numerous conflicts (Aksu et al., Reference Aksu, Erensü and Evren2016). The 2013 Gezi uprisings started as contestation over a few trees and later became one of the country’s most significant protests, constituting a remarkable example illustrating the inherently political nature of environmental contestation.

We selected the Aegean region because, despite its extraordinary environmental values, including rich biodiversity and coastal beauty, many environmentally destructive projects are being undertaken here. Furthermore, 21 per cent of the “environment, natural life and animal protection” associations in Turkey (2684 in total) are located in this region (DERBIS, 2022). Additionally, various local non-institutionalized environmental movements have arisen in the region to oppose projects such as hydropower, thermal power plants and mining.

By examining if the ENGO representatives in the Aegean region view the environment as political, this research aims to make a major empirical contribution to the literature. The literature on depoliticization, post-politics and re-politicization is theoretically well established (Beveridge, Reference Beveridge2017; Felli, Reference Felli2015); so too is the study of party-political views on the environment (Carter, Reference Carter2013; Wang & Keith, Reference Wang and Keith2020). Surveys are a particularly useful technique for understanding trends and behaviours in large samples, but there are few empirical studies using survey techniques to question the extent to which the environment is seen as politics. Moreover, although the number of studies on ENGOs’ relations with the state and with business is rising (Avcı, Reference Avcı2017; Paker et al., Reference Paker, Adaman, Kadirbeyoğlu and Özkaynak2013), their relations with Turkish political parties remain under-examined.

The article first outlines the literature on the meaning of politics and depoliticization and discusses the relationship between the environment and politics. After presenting the methodology, we address environmental activism in Turkey and the Aegean Region, and then present the results of the survey.

Politics

One understanding of politics is as activities related to statecraft and government institutions, the processes whereby decision-makers are appointed and replaced (Beveridge, Reference Beveridge2017). A second understanding sees politics as a form of activity marked by contestation. Contestation might originate from differences in interests, ideas and/or psychological tendencies (Kapani, Reference Kapani2002). As Lasswell (Reference Lasswell1958) puts it, politics is about “who gets what, when, and how”. It requires being in a community, together with others, and sharing a common space. The competing visions, interests and priorities within a community constitute politics. A third approach understands politics as sustaining the common good, as opposed to the contestation of individual interests. The purpose of politics is to establish a social system where everyone benefits (Kapani, Reference Kapani2002). This is similar to Aristotle’s conceptualization of politics, which focuses on how people should ideally live together in communities (Aristotle, Reference Barker1948). Duverger combines the two views, asserting that politics is both a power struggle and a tool for creating a social order that works to all people’s advantage. It is both what happens and what should happen. It includes both contestation and consensus (Duverger, Reference Duverger1967, 29). Ranciere (Reference Ranciere1999) adds to this understanding by emphasizing the role of dynamic, disruptive and democratic engagement by marginalized groups to redistribute material well-being and revise social norms and aspirations.

The debate about the meaning of politics is certainly not limited to the discussion above. For some, politics involves choice and capacity for agency; some describe it as collective activities and thought processes whereby human beings regulate their ways of existing and interacting (Accetti, Reference Accetti2021; Lefort, Reference Lefort1986). This article adopts Duverger’s conceptualization of politics, which recognizes what happens in terms of distribution of power, status, and material well-being in society as well as the normative dimension of how they should be. This conceptualization of politics extends far beyond the actions of political parties and activities in parliamentary spaces.

Civil society is a field of power relations where civil society forces relate to market powers and the state either to uphold or oppose (Cox, Reference Cox1999). Civil society, therefore, is political, and this makes it unfeasible for any member or activity of the civil society to be distanced from politics. Since, according to Duverger’s definition of politics, politics is both what happens and what should happen, civil society can be regarded as playing a role in everyday power struggles and in efforts to redesign society. Hence, because individuals and groups compete for resources, influence and control over various aspects of life, power dynamics are inherent in society. These power struggles can be observed in any relationships where individuals and groups seek to assert their interests and agendas. In such a context, it's entirely normal for a civil society organization to evaluate and comment on the actions of the ruling party or opposition parties.

Similarly, the environment is also political. It serves as a tangible arena where political dynamics unfold, allowing the emergence and deliberation of public concerns (Dikeç, Reference Dikeç2012). In a given environment, people relate to each other as fellow members of a shared polity (Jenkins & Ram, Reference Jenkins and Ram2021). Moreover, the environment itself is an object of political attention. Environmental policy choices have a direct impact on environmental protection and harm. The process of environmental policy-making is inherently political, influencing how societies distribute financial, economic and natural resources both globally and locally (Clapp & Dauvergne, Reference Clapp and Dauvergne2005, 2–3). Notably, the representation of the environment as an arena external to the social has important effects that hide the power and distributive related reasons of natural events and processes (Kenis & Lievens, Reference Kenis and Lievens2014).

Depoliticization and Its Reasons

Depoliticization can be defined as a retreat from the political, which is synonymous with deliberation, argumentation, democracy, contestation and participation. Depoliticization is about establishing incontestability and making alternatives seem nonviable. Post-politics and depoliticization are frequently used interchangeably. It is a consensual mode of governance where dissent is sidelined, and the values of the powerful dominate decision-making (Buller et al., Reference Buller, Dönmez, Strandring, Wood, Buller, Dönmez, Standring and Wood2019). Decision-making is pre-ordained: who can participate, what is possible and what is desirable is already known (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw2011). In Felli’s (Reference Felli2015) terms, depoliticization is characterized by “the power of the non-decision, the capacity of more powerful actors to ensure that some issues are not subject to debate.”

Depoliticization occurs in multiple ways—for example, public debate is limited, spaces of dissent are closed, state power increases. Some actors’ worldviews are deemed illegitimate, and their claims are labelled as “political” and rejected. The appearance of there being nothing in society beyond what is already ordained is created. The social order is not questioned. Despite the uneven distribution of power within society, issues are seen as not contestable. Problems are considered to be “manageable”. Broader contradictions and problems caused by various inequalities are reduced to policy problems. Citizens become consumers, and elections a mere mechanism for choosing between like-minded leaders to ensure the continuation of the system (Buller et al., Reference Buller, Dönmez, Strandring, Wood, Buller, Dönmez, Standring and Wood2019). Political categories of left and right are dismissed. Ideological confrontations are shelved. Alternative ideas are excluded, while decision-making is arranged around buzzwords such as “good governance” and “participation of stakeholders” (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw2011). There is no singular depolitical condition; depoliticization can take place in European, non-European, authoritarian, Global North and/or Global South contexts (Arantes, Reference Arantes2022; Felli, Reference Felli2015; Lawreniuk, Reference Lawreniuk2021).

The reasons for depoliticization are many. First, depoliticization masks the power inequalities behind social problems. With regard to environmental issues, a depoliticized understanding assumes that relying on advanced technology and expertise will achieve the best and most secure solution. For instance, energy issues are at the epicentre of both the global geopolitics and the climate crisis. Green-growth discourses reduce solutions to low-carbon technology use and greener capital accumulation. However, this approach ignores both current inequalities and inequalities that will occur due to low-carbon transition. It shelters power disparities caused by production relations (Turhan & Gündoğan, Reference Turhan and Gündoğan2017).

Second, discursive depoliticization helps to normalize certain outcomes and scenarios. A normalized phenomenon becomes more difficult to criticize and challenge. Hence, normalization facilitates social acceptance of a phenomenon without much protest or challenge. It hides the power relations behind the creation of social norms and expectations and promotes change only to the extent desired by the powerful (Buller et al., Reference Buller, Dönmez, Strandring, Wood, Buller, Dönmez, Standring and Wood2019).

Third, depoliticization can be a highly effective approach for governments and businesses seeking to relocate responsibility for controversial decisions (Bedirhanoğlu, Reference Bedirhanoğlu2022). They make those decisions seem non-political by manipulating public discourse about what is and isn’t political. Incorporating experts—economists, engineers, bureaucrats—into the decision-making process makes those decisions look less political and more “normal” and acceptable (Flinders & Wood, Reference Flinders and Wood2014). Responsibility for decisions is transferred from the real bearers to a “faceless bureaucracy”.

Fourth, according to Gramsci, the hegemony of the powerful prevails not only through coercion, but also through consent. While coercion is applied in marginal cases, in general consent is enough to ensure that people conform to commonsensical norms and ideas. Consent has an economic base, but is not limited to this base. It also signals the dominant position of particular ideas and their tendency to become intuitive, while alternatives are inhibited (Katz, Reference Katz2006). Hence, the depoliticization of an issue signals a hidden consent by society to the current global political-economic structure. In agreeing not to question the power-related reasons for a state of affairs, society submits to the hegemon. Thus, by perceiving the environment as a non-political issue, society agrees to be silent on the power relations behind socio-ecological problems. Herein lies the importance of questioning if, and to what extent, ENGOs, the environmental leaders of civil society, consider the issue of the environment to be political.

The Environment and Depoliticization

Whether or not the environment is perceived as a political issue influences which type of green transformation vision is pursued and the choice of appropriate policies. A post-political understanding of environmental affairs rejects the political aspect of environmental issues, favours a technocentric sustainability transformation, and acknowledges expert and/or market-based solutions. International financial institutions, such as the World Bank and the European Investment Bank, have followed this approach (European Investment Bank, 2022; World Bank, 2022). Controversies are unwelcome, apart from those between elites and technical experts over the choice of appropriate technologies, administrative details and timescales of implementation (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw2011).

On the other hand, acknowledging the environment as a political issue allows for questioning different conceptualizations of sustainable transformations—for example, technocratic versus eco-socialist. It recognizes the politics around knowledge production about the environment and allows for a larger, structural green transformation than tolerated by the technocratic or market-centric approaches. Understanding the politics behind environmental issues enables us to grasp how the current pathway is shaped, the losers and winners, and the reasons for inequalities (Newell, Reference Newell, Scoones, Leach and Newell2015). In that sense, while green economy and growth are ideas that facilitate green capitalist accumulation through expropriation and dispossession, a political reading of environmental issues enables the recognition of the destructive impacts of large-scale industrial life, mining, large dams, and so on (Turhan & Gündoğan, Reference Turhan and Gündoğan2017).

In addition, since rejecting the environment as a political issue hides the distribution of power-related reasons for environmental degradation, it disables people who can otherwise stand together against ownership-related causes of environmental harm. Environmental problems are not only technical problems. They can derive from capital accumulation strategies, state–business cooperation, growth fetishism and the creation of surplus value. In that sense, they are a problem of capitalism. If, while struggling against such problems, for the sake of claiming a post-political stance, democratic groups are asked to isolate themselves from their institutional identities and their other democratic demands, they become insignificant. Environmental problems disproportionately impact women, the poor and the labour class. When environmental problems are reduced to merely a local problem, their class- and gender-related origins are concealed. The possibility of allying with other movements, like labour and women’s movements, is hindered. Hence, depoliticization obstructs the constitution of a strong and effective environmental movement.

Why, then, do some ENGOs prefer to see the environment as a non-political issue or—at least—discursively claim to do so? There might be several answers. First, and most commonly, politicization can be understood as a negative and divisive thing hampering social participation, democracy and harmony. It can be seen as a phenomenon where certain parties dominate, and clientelism obstructs participation and limits opposition (Rumelili & Çakmaklı, Reference Rumelili and Çakmaklı2017). Due to this negative connotation of politics in the society in which the ENGOs operate, they might prefer to distance themselves and their activities from politics.

Moreover, politics is commonly understood to be limited, equated with engaging with political parties only—and political parties are often seen as institutions harbouring corruption and dishonesty. Due to the lack of democracy and power imbalances within parties, being ‘political’ is regarded as undesirable. Hence, in order to distance themselves from political parties, ENGOs might prefer to adopt an apolitical stance, enabling them to appeal to voters across a wide political spectrum. Thus, when environmental destruction threatens a community—for example, a mine polluting a village’s water supply—ENGOs might attract support from citizens who would be deterred by a ‘political’ environmental protest (Accetti, Reference Accetti2021; Felli, Reference Felli2015).

Methodology

The study is conducted through survey methodology and designed as exploratory research aiming to establish understanding rather than testing hypotheses. To develop the survey, the authors conducted an extensive literature review on environmental movements, civil society, post-politics and depoliticization, and analysed questionnaires used in similar survey-based research. The draft questions were tested on three environmental activists for clarity and appropriateness. The survey’s 27 questions (listed in Appendix) contained true/false, Likert-scale, multiple-choice and open-answer types. Surveymonkey was used to carry out the survey, and also helped to analyse the results.

The survey was sent to 304 ENGOs in the Aegean region of Turkey, including both institutionalized ENGOs and groups organized in the form of environmental movements. ENGOs in Balikesir and Çanakkale were also included, since these are coastal cities on the Aegean. To reach as many ENGOs as possible in the region, national and international databases—such as those of Turkey’s Ministry of Interior General Directorate of Civil Society Relations (DERBIS), the Association of Civil Society Development Information Center (STGM), the Environmental Justice Atlas, Ekoharita and Zehirsiz Sofralar Sivil Toplum Kuruluşları Ağı—were extensively mined, and social media—Facebook and Twitter—searches conducted.

Out of 304 ENGOs to which the survey was sent, 119 answers were collected between October 2021 and April 2022 (a 39 per cent response rate). After the first invitation, reminders were sent via e-mail and phone calls. There are no systematic differences between the respondent and non-respondent ENGOs. Although the response rate is below 50 per cent, it surpasses that of similar studies, reflecting the inherent challenges of engaging with local civil society actors. The survey was answered by representatives of ENGOs on behalf of the ENGOs. In the article, “representatives of ENGOs who participated in our survey” and “ENGOs who participated in our survey” are therefore used interchangeably. The respondents may have represented their own individual perceptions and the perceptions of the organization at different points in the survey depending on the questions (Appendix).

Environmental Politics in Turkey and the Aegean Region

Depoliticization has been widespread in the context of environmental issues in Turkey until recently. The reasons for this lie in the history of a country smashed by military coups and a repressive political atmosphere.

From the mid-1950s in particular, with rapid urbanization, industrialization and socio-economic transformation impacting agriculture, environmental problems began to emerge in Turkey, including soil, water and air pollution. Nevertheless, it was not until the late 1980s that ENGOs started to be established. The 1990s experienced some significant environmental movements—including the Bergama resistance against mining and opposition to the Yatağan and Aliağa thermal power plants and to the Akkuyu nuclear power plant—which increased environmental awareness (Adaman et al., Reference Adaman, Akbulut and Arsel2017). However, the repressive political atmosphere following the 1980 military coup constrained the spread of environmental movements. Various political parties and trade unions were shut down. The 1982 Constitution banned associations from pursuing political aims, with depoliticizing consequences. Article 33, for instance, stated: “Associations … cannot pursue political aims, cannot engage in political activities; they cannot receive support from political parties and cannot support them”; Article 135 similarly prohibited professional organizations from dealing with politics and acting in partnership with political parties (1982 Constitution of the Republic of Turkey, 2021).

Banning political parties and associations is commonly experienced in the aftermath of military coups in various countries such as Chile and Greece. However, in the Turkish case, the bans remained for a particularly long time; the Constitution was amended to remove them only in 1995, many years after the return to multi-party politics (1982 Constitution of the Republic of Turkey, 2021). The consequent hesitant social attitudes to engaging in politics have translated into a depoliticized perception of inherently political activities.

The Justice and Development Party (AKP), having come to power in 2002, has established the longest-ruling one-party government in Turkey’s history. Under its governance, real-estate speculation and intensification of the construction and energy sectors have become engines of growth, leading to unplanned and rent-seeking urban transformation. Several large-scale power plants and countless micro-hydro dam projects have been implemented (Adaman et al., Reference Adaman, Akbulut and Arsel2017; Aydın, Reference Aydın2019; Kurtiç, Reference Kurtiç2022; Özkaynak et al., Reference Özkaynak, Aydın, Ertör-Akyazı and Ertör2015). Despite its rich biodiversity and high environmental value, various environmentally destructive projects have also been planned for and implemented in the Aegean region. Examples include the Yatağan and Aliağa power plants; the Bergama, Uşak-Eşme and İzmir-Efemçukuru mining projects; the Çeşme project; and various wind turbines. For this reason, the region has seen a significant rise in the number of locally organized, small-scale environmental groups (Özen, Reference Özen2025).

Survey Data: Framework Description and Findings

Framework Description

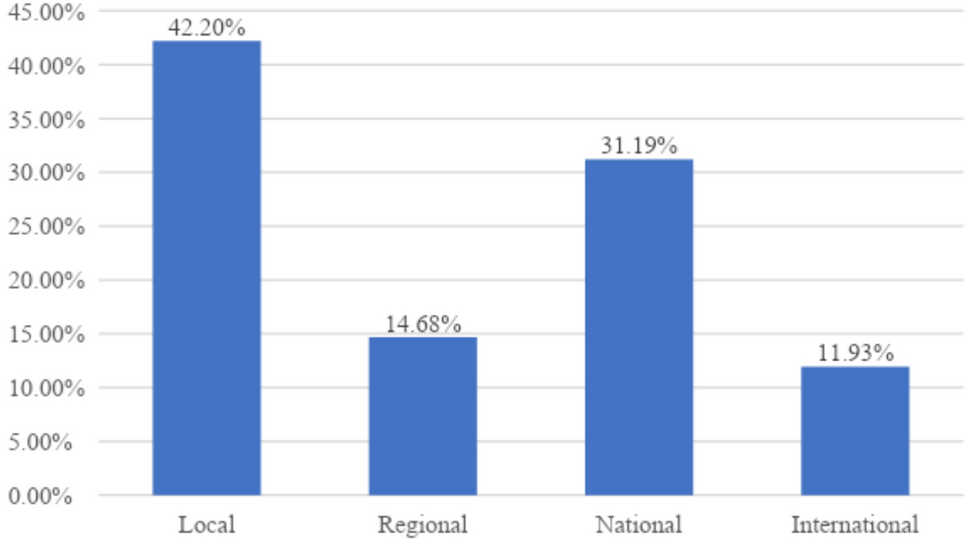

All results and figures in this section come from our survey and include all participating ENGOs (that is, they are not from a selected/representative sample). Our survey data confirm the rise in the number of ENGOs in the Aegean region after the 2000s. Figure 1 shows that two-thirds of the ENGOs participating in our survey were established after 2010, indicating rising environmental activism during the AKP period. Half of the ENGOs in the region are in Izmir (20 per cent), Muğla (18 per cent) and Çanakkale (12 per cent) (Fig. 2). Figure 3 further details the operational scale of the ENGOs: 42.2 per cent work locally, 31.19 per cent nationally, and 14.68 per cent regionally.

Fig. 1 Year of establishment of ENGOs

Fig. 2 Location of ENGOs

Fig. 3 Operational scale of ENGOs

Findings

We present our findings in three subsections depending on the questions we discuss: (a) ENGO participants, activities, philosophies, and solutions, (b) politics and political parties, and (c) depolitization.

ENGO Participants, Activities, Philosophies and Solutions

At the beginning of our survey, to assess whether the ENGOs have a uniform understanding of politics, we asked the ENGO representatives how they conceptualize politics. Most participants (52.5 per cent) think politics can be described as “activities that exist in all areas of social relations, dealing with by whom and how resources, power, and relations are distributed”. This is followed by the distribution of political power and government-focused descriptions, such as “making and changing general rules for managing people’s lives” (21.5 per cent); “organizing, directing and conducting government affairs” (13.7 per cent); and “the struggle for political power, relations with authority or power” (6.25 per cent).

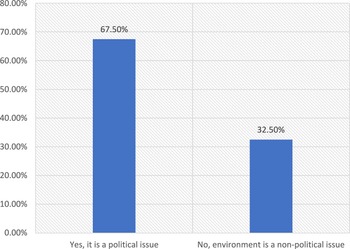

The ENGO representatives were then asked if they view the environment as a political issue: 67.5 per cent do so, whereas 32.5 per cent do not (Fig. 4). We found variance among these two groups in four respects: gender and political party membership, ENGO activities, environmental philosophies supported by the ENGO, and the environmental solutions they offer.

Fig. 4 Environment as a political issue. Question: Do you perceive the environment to be political?

The proportion of females in the ENGOs whose representatives regard the environment as politics is noticeably higher: 61 per cent, as opposed to 52 per cent of ENGO members whose representatives do not see the environment as a political issue (Fig. 5). While 41 per cent of ENGO members belong to a political party if the ENGO representative considers the environment a political issue, the percentage drops to 35 per cent in the ENGOs whose representatives do not see the environment as political. Hence, in the ENGOs with higher political party members, it is more likely that the representative will see the environment as an issue of politics. Furthermore, the ENGOs whose representatives take the environment as politics engage in protest activities suggestively more often (61 per cent) than the ENGOs whose representatives do not (40 per cent). This shows that the more an ENGO has a politicized understanding of the environment, the more often it engages in protest-based, resistance activities. This highlights a close link between the political conceptualization of the environment and adopting more activist strategies. These ENGOs are more inclined to emphasize systemic changes, advocating for policy reforms and broader societal transformations, whereas non-political ENGOs often focus on awareness campaigns.

Fig. 5 ENGO participant profile and environmental philosophies/approaches

We also seek to understand which environmental philosophies the ENGO representatives in our survey endorse. The respondents had to choose between three options: “eco-socialism”, “decentralization” and “love of nation”. Ecosocialism advocates equitable distribution of resources while protecting the environment. Decentralization refers to granting power and decision-making processes to local communities for more effective environmental protection. Love of nation can be understood as a deep sense of care and responsibility for one’s country and its natural surroundings. We found that the ENGOs whose representatives regard the environment as politics showed greater support for eco-socialism (72.6 per cent) and decentralization (82.6 per cent) than their non-political counterparts (57.6 and 72.6 per cent, respectively. The latter supported love of nation as a philosophy of environmentalism to a greater extent (86 per cent) than those representatives who believe the environment is political (70 per cent) (Fig. 5). These numbers reveal that political ENGOs tend to align with philosophies emphasizing systemic change and community empowerment. In contrast, non-political ENGOs gravitate towards a nationalist framework that prioritizes protecting the environment as part of a broader sense of national pride and identity.

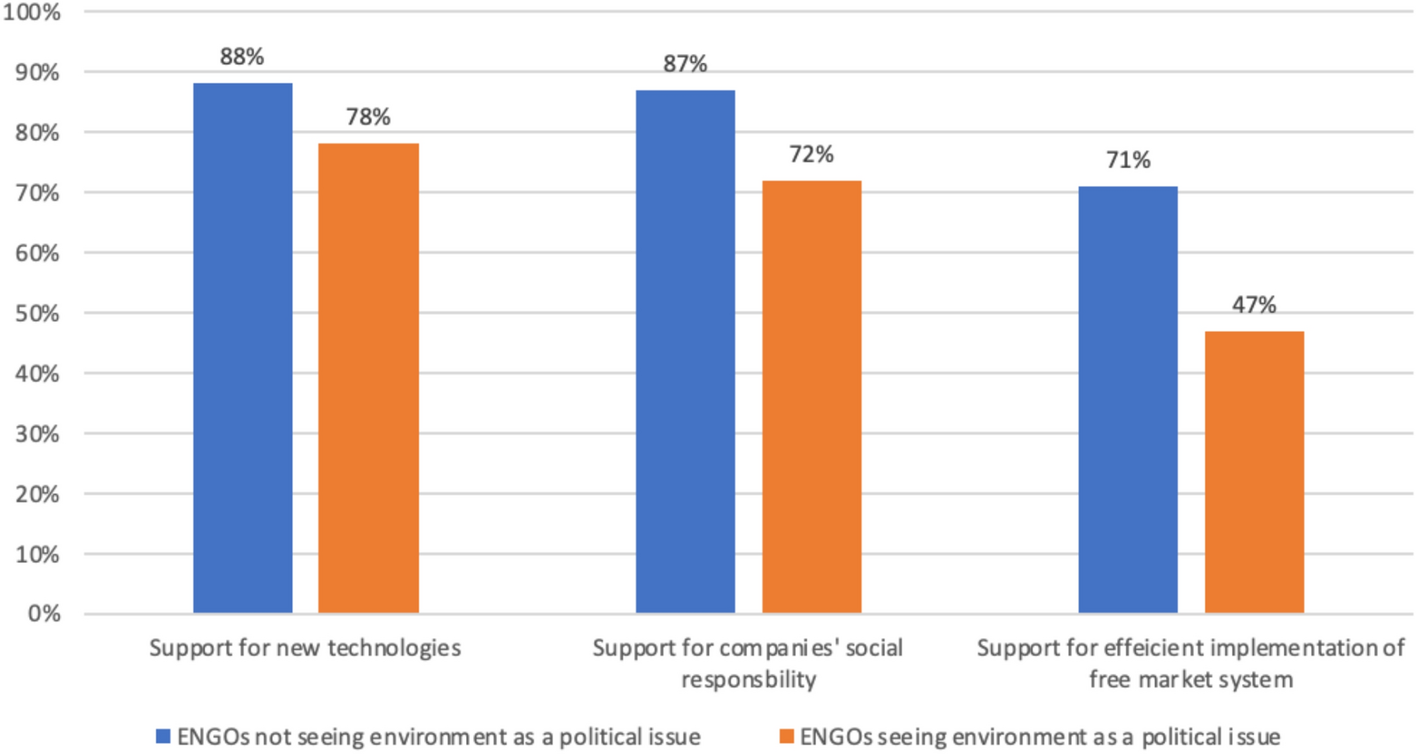

There is also variance among the environmental protection solutions offered by the ENGOs whose representatives see the environment as a political issue or not (Fig. 6). Both the ENGOs whose representatives see the environment as a political issue and those that do not support new technologies (78 per cent and 88 per cent) and companies’ social responsibility (72 per cent and 87 per cent) significantly. However, while efficient implementation of the free-market system is highly promoted by the ENGOs whose representatives do not take the environment as a political phenomenon (71 per cent), the level of support for this solution among the ENGOs whose representatives regard the environment as a political phenomenon is relatively lesser (47 per cent). This divergence indicates a fundamental ideological divide: those who view the environment as political issue are more likely to question market-driven solutions and prioritize alternatives. In contrast, ENGOs that do not see the environment as inherently political tend to favour market-based strategies, believing that economic growth and innovation can solve environmental problems more effectively.

Fig. 6 ENGO support for environmental solutions

Politics and Political Parties

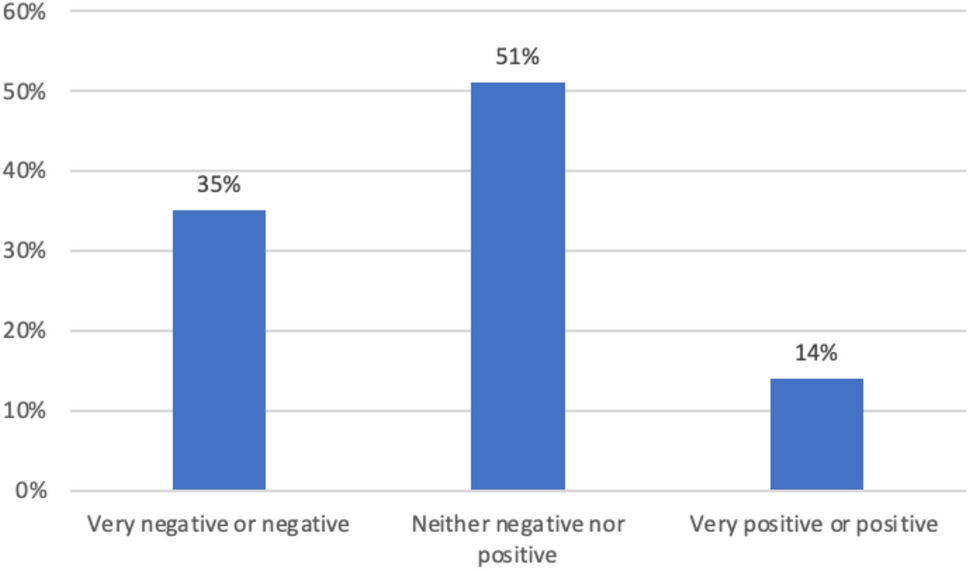

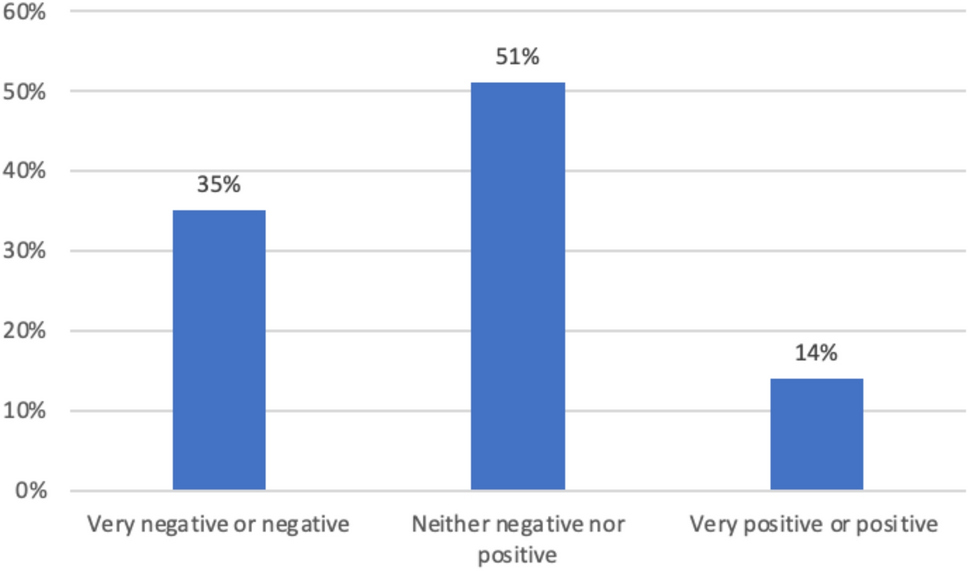

Our survey results suggest that a negative and prejudiced conceptualization of politics is quite widespread among ENGO representatives: 35 per cent of them have a “very negative” or “negative” view of political party membership, and 51 per cent are “neither negative nor positive” towards it; only 14 per cent are “positive” or “very positive” (Fig. 7). This confirms the antipathy towards political parties fostered by the oppressive atmosphere following the 1980 coup. It should also be noted that there is no ENGO representative who both sees the environment as not political and who thinks of being a party member as “positive” or “very positive”. This points to a deep-rooted distrust of political institutions within certain segments of the ENGO community, possibly reflecting a broader societal sentiment about politics.

Fig. 7 Support for the Idea of becoming a political party member

Nevertheless, 88 per cent of the ENGO representatives who regard the environment as a non-political issue still think that political parties should handle the issue of the environment (across the entire sample the percentage is 90 per cent). Hence, the ENGO representatives believe in the usefulness of political parties in safeguarding the environment. Although, at first glance, this could be a contradictory finding, it must be emphasized that political parties are still the strongest actors in shaping politics in Turkey. Hence, ENGO representatives put their hopes for more environmental protection on political party activism in this realm. Furthermore, 52 per cent of the respondents who do not see the environment as a political issue believe that environmentalist sentiment will grow stronger if political parties join environmental movements, and only 12 per cent of them think that political parties’ joining environmental activities will harm these activities.

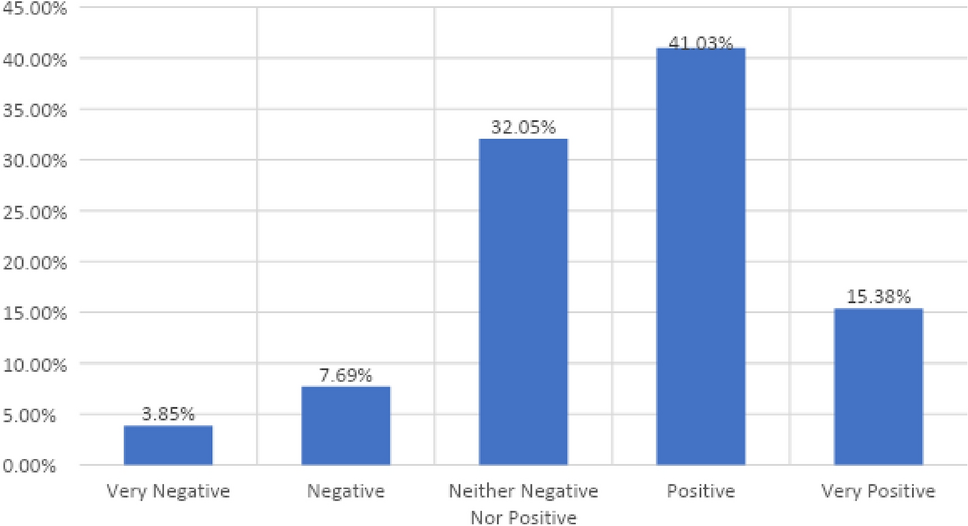

In other words, although these ENGO representatives do not see the issue of the environment as a political issue per se, most of them still believe that the environment is an issue that political parties should tackle and that environmentalism is a fight where there is room for political parties. Across the entire sample, 56.41 per cent of ENGO representatives believe that environmentalist sentiment would benefit from the involvement of political parties, and only 11.54 per cent believe the opposite (Fig. 8). The main reasoning behind this support is the capacity of political parties to effectively mobilize the masses against environmental threats. This highlights that even among those who prefer to keep environmentalism separate from politics, there is recognition of the critical role that political entities play in shaping public policy and addressing environmental challenges.

Fig. 8 Political parties and the environment. Question: How does the involvement of political parties influence environmental struggles?

We also asked about the type of political party needed for effectively dealing with environmental issues. Only 3 per cent of the ENGO representatives who favour environmental issues being tackled by political parties considered that a right-wing political party with environmental demands in its programme would be effective (Fig. 9). Although right-wing parties traditionally command greater support in Turkey than left-wing parties (Çarkoğlu & Hinich, Reference Çarkoğlu and Hinich2006), support for the left is slightly higher in the Aegean region, where this research was conducted. Furthermore, because our subjects are actors who commonly confront state and business activities in pursuit of environmental protection, it is unsurprising to find little support for the right.

Fig. 9 Ideology of the political parties preferred by the ENGOs

Concomitantly, we found greater belief that a left-wing party with environmental demands in its programme or a green party would tackle environmental issues more effectively (40.5% and 29%, respectively). This aligns with the general perception that right-wing parties, often associated with neoliberal economic policies and deregulation, may not prioritize environmental protection in the same way as left-wing parties. Relatively low levels of support for the establishment of green parties can primarily be explained by the electoral failures and short electoral lives they have so far experienced in Turkey (Sahin, Reference Sahin2015). ENGO representatives cited various problems with green parties: “the idea was not well explained to the public”; “they were not sufficiently integrated with the public”; “they were not organized strongly enough”; and “the socio-physiological and cultural structure in the country did not allow for the establishment of a successful green party”. In an “open answer”, some ENGO representatives, furthermore, felt that “environmentalism cannot be castrated by limiting it to one party” or that “environment and nature cannot have a party”, or that best placed to deal with the environment was “any party that can handle ecology and class issues together”.

Concerning the current handling of environmental matters by politicians in Turkey, most respondents believe that environmental issues are either poorly or very poorly handled (44% and 47%, respectively); with 8% neutral and only 1% considering that they are effectively handled (Fig. 10). We also asked about the environmental issues that politicians tackled best. While none was generally considered to be handled effectively, and the differences among the highest-ranking issues were minimal, the top three, according to the weighted average, were “forests” (38.2%), “renewable energy” (37.8%) and “dams and HES” (36%), while the three least effectively handled were “plastics” (30.6%), “urban planning, sprawl, and traffic” (29.8%) and “biological diversity” (27.6%) (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10 Politicians’ current treatment of environmental causes

Fig. 11 The effectiveness of politicians addressing certain environmental issues

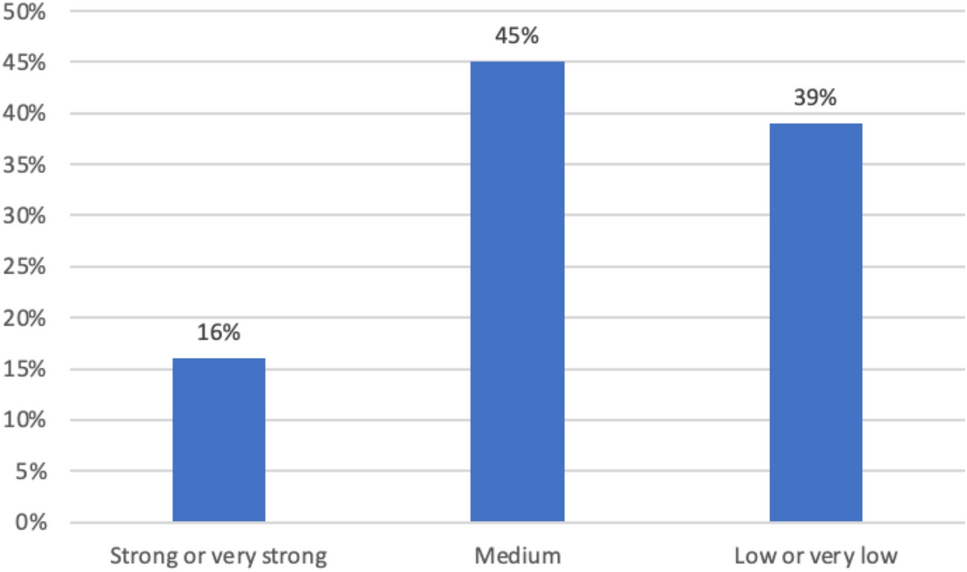

Our survey also reveals that relations between ENGOs and political parties remain poor. Only 16% of the ENGO representatives define their relations with politicians and political parties as “strong” or “very strong”; 45% describe their relations as “medium,” while the rest express their relations as “low” or “very low” (Fig. 12). This reflects a broader disconnect, where ENGOs view political parties as insufficiently committed to environmental causes or being influenced by other competing interests, leading to limited collaboration and trust. Additionally, the lack of strong ties suggests that ENGOs struggle to influence policy decisions through traditional political channels.

Fig. 12 Relations between ENGOs and political parties

Depoliticization

The survey responses confirm our expectations that the main reason for depoliticization and reluctance to participate in party politics is mistrust in political parties (Fig. 13). Nearly 40% of the respondents refer to corruption as the reason for not joining a political party. Given the growing corruption regarding the state-capital relationship in the country, this finding is not surprising (Soyaltin, Reference Soyaltin2017). This widespread distrust is likely fueled by perceptions of a deeply entrenched system in which political parties are seen as complicit in maintaining the status quo, often prioritizing the economic interests of their allies over environmental concerns. Around 25% see the parties as part of the established order, making it impossible to protect the environment through them, as they believe that these parties are either too compromised or beholden to powerful business interests that hinder meaningful environmental reform. About 20% consider that the political parties handle the environment inadequately, pointing to a lack of effective, long-term strategies, or policies that fail to address the urgency of environmental challenges. Another 20% contend that the environment should be tackled solely by civil society, reflecting a preference for grassroots, non-political action as a more viable path for environmental protection, free from the perceived corruption and inefficiency of formal political structures.

Fig. 13 Reasons for Non-Membership of Political Parties. Question: Why do you not become a political party member? (This question was asked only to the respondents who had never been a political party member)

This all raises an interesting dilemma: why do the ENGO representatives overwhelmingly (90% of them, as discussed above) support the involvement of political parties in environmental problems, but at the same time accuse them of corruption and of being part of the establishment which is serving the environment so badly?

There are at least three potential explanations. Firstly, as political parties are the primary actors in the political arena with the capacity to mobilize the masses and shape political agendas, ENGO representatives may hope for a greater impact when these parties utilize these powers to the good. Secondly, addressing environmental issues frequently involves uncovering rent-seeking activities associated with environmentally harmful projects. So, the reluctance of party elites to reveal their own rent-seeking activities may lie behind the lack of enthusiasm for environmental concerns evinced by most parties. Thirdly, 66% of the ENGO representatives in our sample have never been political party members. Their lack of knowledge and experience of party politics might affect both their ability to gauge the effectiveness of political parties in furthering environmental protection and their understanding of political corruption. Despite this argument, though, we should also note that as of 2024, over 65 million people are eligible to vote in Turkey, while the total number of party members revolves around 14 million, which corresponds to a member/voter ratio of 21%. Our survey data reveal that the member/voter ratio is still higher among the ENGO representatives than ordinary citizens.

Moreover, 61% of all survey participants believe that taking the environment to be a non-political issue might more easily promote societal consensus over environmental issues (Fig. 14). Hence, it might be the case that some ENGOs use depoliticization pragmatically to gain supporters who would otherwise not be attracted to environmental causes. By framing environmental protection as a neutral, universally beneficial issue, these ENGOs are likely to appeal to individuals across different political ideologies and classes. This strategy can help expand the reach of environmental movements, attracting supporters who may be wary of political affiliations but are still motivated by concerns for sustainability, health, or future generations. However, there is also a considerable portion of ENGO representatives (22%) who do not regard the environment as a political issue, but at the same time believe that this depoliticization does not help to create consensus over environmental issues. These representatives may see depoliticization as a superficial approach that overlooks the root causes of environmental challenges, which are often deeply intertwined with political, economic, and social structures.

Fig. 14 Depoliticization of the Environment for the Creation of Consensus. Question: Do you think the handling of the environment as a non-political issue increases consensus over environmental issues?

Conclusion

The post-political vision, in thrall to neoliberalism, regards the environmental domain as an issue to be managed by technical experts through consensual policy formation. It hides the unequal power relations behind the distribution of environmental goods and harms, and normalizes the outcomes preferred by the powerful. Depoliticization of the environment also prevents different politically aware groups—local environmental groups, labour and gender activists, and so on—from allying with each other, by concealing the ways in which environmental degradation is particularly damaging to them. It thereby inhibits the potential of broader environmental mobilization.

This article investigated the extent to which ENGO representatives in the Aegean region see the environment as political and examined their perceptions about the nexus between the environment and politics. We contribute to the depolitization literature through analysing a large sample, showcasing a variety of stances. We also contribute through an in-depth study of the Aegean region of Turkey, a country with a socio-political history characterized by military coups and a repressive political atmosphere. The study also reveals that even among ENGOs with differing views on the political nature of environmental issues, there is widespread consensus on the necessity of political party involvement, suggesting a unifying potential in addressing environmental challenges. Thus, the article contributes to the understanding of environmental activism in Turkey and beyond.

We find that in the Aegean region of Turkey, around one-third of ENGO representatives see the environment as a non-political issue (Please see Table 1 for a summary of the main findings). Hence, in the region, part of the ENGOs operate by seeing the environment as an issue of politics, while others think of it as a depoliticized topic. There is variance between the ENGOs whose representatives regard the environment as politics and those that do not, in respect of the gender and party membership of their supporters, their activities, their environmental philosophies, and the solutions they offer. The proportion of female participants and political party members in the ENGOs whose representatives consider the environment as politics is noticeably higher. These ENGOs engage in protest activities more often. They support eco-socialism and decentralization to a greater extent than those who do not regard the environment as a political issue. On the other hand, love of nation as a philosophy of environmentalism is more widespread among the ENGOs whose representatives do not see the environment as a political issue. Finally, while new technologies and companies’ social responsibilities are solutions promoted by both types of ENGO, there is a greater inclination to favour market-driven solutions among the ENGOs whose representatives view the environment as non-political.

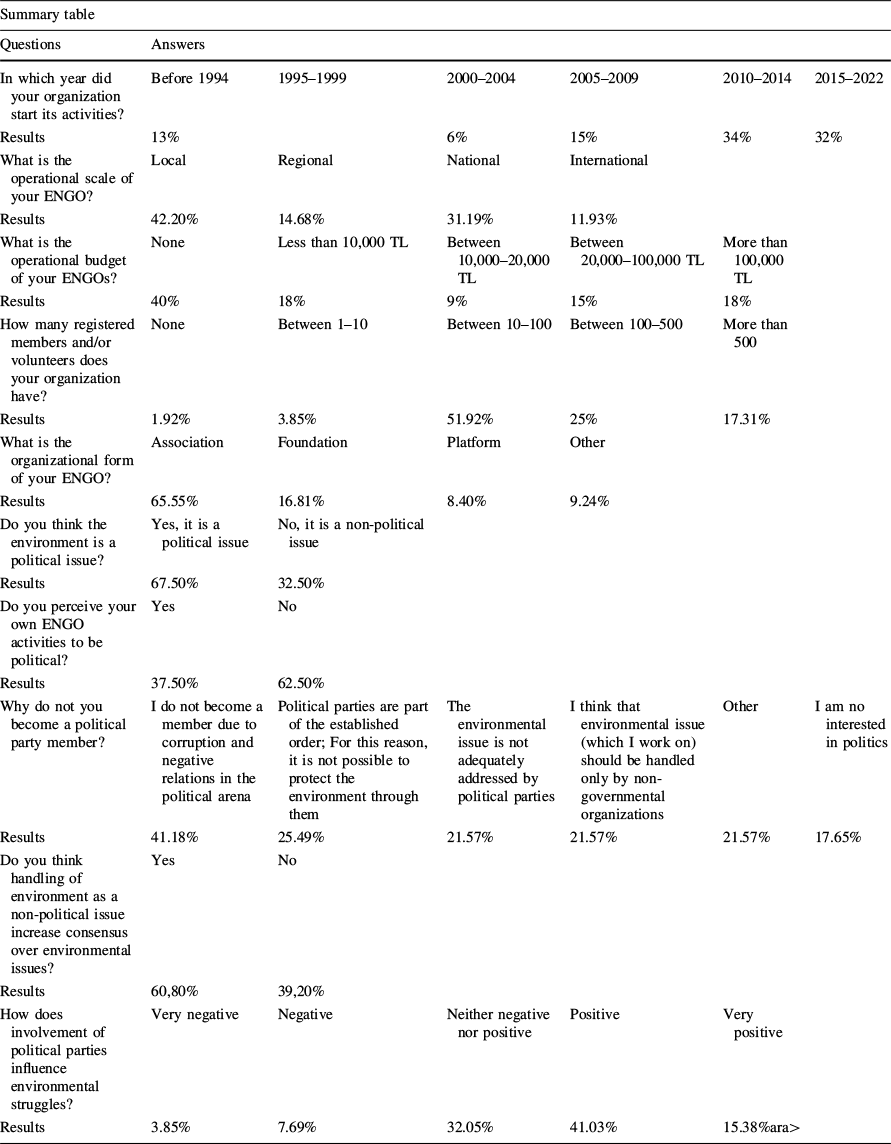

Table 1 Summary of some of the key findings

|

Summary table |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Questions |

Answers |

|||||

|

In which year did your organization start its activities? |

Before 1994 |

1995–1999 |

2000–2004 |

2005–2009 |

2010–2014 |

2015–2022 |

|

Results |

13% |

6% |

15% |

34% |

32% |

|

|

What is the operational scale of your ENGO? |

Local |

Regional |

National |

International |

||

|

Results |

42.20% |

14.68% |

31.19% |

11.93% |

||

|

What is the operational budget of your ENGOs? |

None |

Less than 10,000 TL |

Between 10,000–20,000 TL |

Between 20,000–100,000 TL |

More than 100,000 TL |

|

|

Results |

40% |

18% |

9% |

15% |

18% |

|

|

How many registered members and/or volunteers does your organization have? |

None |

Between 1–10 |

Between 10–100 |

Between 100–500 |

More than 500 |

|

|

Results |

1.92% |

3.85% |

51.92% |

25% |

17.31% |

|

|

What is the organizational form of your ENGO? |

Association |

Foundation |

Platform |

Other |

||

|

Results |

65.55% |

16.81% |

8.40% |

9.24% |

||

|

Do you think the environment is a political issue? |

Yes, it is a political issue |

No, it is a non-political issue |

||||

|

Results |

67.50% |

32.50% |

||||

|

Do you perceive your own ENGO activities to be political? |

Yes |

No |

||||

|

Results |

37.50% |

62.50% |

||||

|

Why do not you become a political party member? |

I do not become a member due to corruption and negative relations in the political arena |

Political parties are part of the established order; For this reason, it is not possible to protect the environment through them |

The environmental issue is not adequately addressed by political parties |

I think that environmental issue (which I work on) should be handled only by non-governmental organizations |

Other |

I am no interested in politics |

|

Results |

41.18% |

25.49% |

21.57% |

21.57% |

21.57% |

17.65% |

|

Do you think handling of environment as a non-political issue increase consensus over environmental issues? |

Yes |

No |

||||

|

Results |

60,80% |

39,20% |

||||

|

How does involvement of political parties influence environmental struggles? |

Very negative |

Negative |

Neither negative nor positive |

Positive |

Very positive |

|

|

Results |

3.85% |

7.69% |

32.05% |

41.03% |

15.38%ara> |

|

Political parties are commonly seen as corrupt and nepotistic entities by ENGO representatives. Most of them have never been political party members and believe that environmental matters in Turkey are very poorly handled by politicians. The relations between ENGOs and political parties remain weak. Nevertheless, a huge majority of the ENGOs (90%) think that political parties should engage in environmental matters and that a left-wing party with a strong environmental agenda carries the best hope for the future.

Undoubtedly, questioning the connection between the environment and politics and exploring whether ENGOs view the environment as political or not—as this article does—is itself a political act. It is so because this process encourages ENGO representatives to contemplate the relationship between their beliefs, actions and politics, and to publicize it, provoking their audiences to think about this too.

We recognize the existence of potentially different responses to our survey questions even within the same ENGO and acknowledge that our survey is limited by being confined to only one representative per ENGO. We also acknowledge the 39% response rate from ENGOs to our survey as a limitation and suggest that future studies be conducted with higher participation rates. One particularly interesting question for future research would be the extent to which globally active ENGOs that have consultative status with the United Nations perceive the environment to be a political issue and their understanding of the nexus between the environment and politics.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank to their research assistant Büşra Sarıkaya for her rigorous help, all environmental groups in the Aegean region of Turkey for their participation in the survey and Prof. Aykut Çoban for his thorough feedback and support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). The data in this study were collected with the financial support of Yaşar University.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no financial or other conflict of interest to report for this article.

Ethical approval

The questions used in the survey were approved by the Yaşar University’s Ethical Commission. All survey participants granted their approval for the use of the data in this research. The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Appendix: Survey Questions

-

1. What is the organizational form of your organization? (Multiple choice)

(Answer choices: Association—Foundation—Platform—Other)

-

2. In which year did your organization start its activities? (Free response)

-

3. What is the operational scale of your organization? (Multiple choice)

(Answer choices: Local–Regional-National–International)

-

4. In which cities does your organization operate? Please check all that apply. (Multiple choice)

(Answer choices: Izmir-Muğla-Manisa-Aydın-Çanakkale-Denizli-Balıkesir-Uşak-Afyonkarahisar-Kütahya).

-

5. Does your organization have an office? (Multiple choice and open answer)

Answer choices:

-

a. Yes, we have private office.

-

b. Yes, we have a joint office with other institutions.

-

c. Yes, we use an office allocated by the municipality.

-

d. Yes, we use the office allocated to us by a public institution.

-

e. No, we don't have an office, we work from home.

-

f. Other (Please provide more information).

-

-

6. How many registered members and/or volunteers does your organization have? (Multiple choice)

(Answer choices:1–10/ 10–100/100–500/more than 500)

-

7. What is the annual budget of your organization? (Please consider your most recent activity budget) (Multiple choice)

(Answer choices: None/less than 10.000 TL/10.000–20.000/20.000–100.000/more than 100.000)

-

8. What is the representation ratio of the groups listed below in your organization? Please mark one option for each line (Likert scale)

-

9. How often does your organization participate in any policy-making process related to the environment at the following levels? (including meetings, consultations, or information processes related to any policy-making) please mark one option for each line (Likert scale)

-

10 Please indicate how often your organization engages in the following activities. Please mark one option for each line. (Likert scale)

-

11 How close is your organization to the environmental approaches/ideologies listed below? Please mark one option for each line (Likert scale)

-

12 Which of the following "politics" definitions do you feel closer to? Please select 2 options (Multiple choice)

Answer choices:

-

a. Organizing, managing and conducting state affairs.

-

b. Political power struggle, relationships related to authority or power.

-

c. Managing people and societies.

-

d. Activities that exist in all areas of social relations and focus on who, how and in what way all kinds of resources, power and relationships are distributed.

-

e. Making and changing general rules to organize people's lives.

-

f. Issues that are outside of production but must be carried out on a social scale in order to sustain the production process.

-

g. Decision-making in any group, the distribution of power, resources and status among individuals.

-

h. Deception and manipulation.

-

i. None.

-

-

13. Do you think the environment is a political issue? (Multiple choice)

Answer choice:

-

a. Yes, it is a political issue.

-

b. No, it is an issue outside of politics.

-

-

14. Do you think your organization's environmental activities are a political activity? (Multiple choice) (Answer choices: Yes–No)

-

15. Do you think considering the environment as a depolitical issue increases social consensus on environmental issues (such as mining, building parks, air pollution)? (Multiple choice) (Answer choices: Yes–No)

-

16. How do you think the involvement of any political party in environmental activism affects this activism? (Likert-scale).

-

17. Do you think environmental demands/issues should be addressed by political parties? (Multiple choice) (Answer choices: Yes–No)

-

18. In your opinion, which types of political parties in Turkey can more effectively and successfully address environmental demands? (Multiple choice and open answer)

Answer choice:

-

a. Green party (A party that works especially on environmental issues)

-

b. A right-wing political party whose programme includes environmental issues

-

c. A left-wing political party whose programme includes environmental issues

-

d. It doesn't matter

-

e. Other (Please provide more information)

-

-

19. In your opinion, what is the reason for the lack of desired success in the Green Party experiences in Turkey so far? (Answering is not mandatory) (Open answer)

-

20. Are you a member of any political party or have you been a member before? (Multiple choice) (Answer choices: Yes–No)

-

21. How do you evaluate the idea of becoming a member of a political party? (Likert-scale)

-

22. What is the reason for not being a member of any political party? Please check all that apply. (Multiple choice and open answer)

Answer choices:

-

a. The environmental issue is not adequately addressed by political parties.

-

b. I work on the environment and I think this issue should only be addressed by non-governmental organizations.

-

c. I do not become a member due to corruption and negative relations in the political arena.

-

d. I have no interest in politics.

-

e. Political parties are part of the established order; Therefore, it is not possible to protect the environment through them.

-

f. Other (Please provide more information)

-

-

23. How competent do you think the issue of the environment is being handled by parties/politicians in Turkey? (Likert-scale)

-

24. In your opinion, to what extent are each of the following environmental issues being addressed by parties/politicians in Turkey? Please mark one option for each line. (Likert-scale)

-

25. How would you describe the relationship of your organization with political parties and representatives? (Likert-scale)

-

26. How often does your environmental organization engage with political parties/party representatives in Turkey in the following activities? Please mark one option for each line. (Likert-scale)

-

27. What are the importance levels of the following factors in solving environmental issues? Please mark one option for each line. (Likert-scale)