Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major global health threat that undermines decades of medical progress. It limits effective treatment options, leading to increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. 1 In 2019, 4.95 million deaths were associated with bacterial AMR, including 1.27 million deaths directly attributable to bacterial AMR. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly those in the Western African region, are among the most affected, with an AMR burden estimated at 27.3 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. Reference Murray2 Excessive and inappropriate antimicrobial use (AMU) remains a primary driver of AMR. In some LMIC hospitals, up to 90% of inpatients receive antibiotics, many without clear indication or adherence to guidelines. Understanding prescribing patterns through systematic surveillance is therefore essential to guide antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) interventions. Reference Versporten, Zarb and Caniaux3–Reference Umeokonkwo, Oduyebo and Fadeyi5 To address this misuse, surveillance of AMU is crucial, as it provides a better understanding of how antimicrobials are used, investigates current practices, and highlights areas for improvement. 1,Reference Pasquale, Trienski and Olexia6 Point prevalence surveys (PPSs) are widely recognized surveillance methods that provide valuable information on antimicrobial prescribing practices and other relevant factors in hospitalized patients, with limited resources required. Reference Dean, Lawson, Jacklin, Rogers, Azadian and Holmes7–Reference Pauwels, Versporten, Vermeulen, Vlieghe and Goossens10 The Global Point Prevalence Survey (Global-PPS) of Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance (Global-PPS, www.global-pps.com) is a standardized methodology that aims to assess the global prevalence of antimicrobial prescription, healthcare-associated infections, and resistance in hospitals and healthcare centers worldwide. It is designed to be feasible also in countries with low resources, support, and expertise. This methodology, developed by the University of Antwerp, has been used to assess AMU in more than 1,600 unique institutions across 100 countries worldwide. 11 The first Global-PPS survey was conducted in 2015 among 53 countries and revealed that AMU varied widely between continents and countries, reaching three-quarters of inpatients treated in some African countries. In 2017, Burkina Faso, a West African nation, adopted its National AMR Action 12 and highlighted its commitment to the global fight against AMR by ensuring effective AMR surveillance and optimizing the antimicrobial prescription in hospital settings. This study, to the best of our knowledge, represents the first effort to evaluate antimicrobial prescribing practices in selected primary, secondary, and tertiary hospitals in Burkina Faso.

MEthodology

Study design

A multicentre PPS on AMU was conducted using the standardized, freely available Global-PPS protocol and web-based data collection platform (www.global-pps.com). The survey was carried out between February and June 2019 across participating hospitals. In each ward, data were collected on a single designated day, including all inpatients occupying a bed at 8:00 a.m. on the day of the survey. Due to logistical and staffing constraints, hospitals conducted their surveys on different days within this period, although the standardized methodology ensured data comparability across sites. Trained general practitioners, acting as local investigators, were responsible for data collection and entry into the secure Global-PPS online system. Training sessions were organized to ensure consistent application of definitions and procedures across hospitals.

Data were collected on key variables, including patient demographics (age, sex), type and route of antimicrobial used, indication for therapy, and classification of infection as either community-acquired (CAI) or healthcare-associated infection (HAI). Prescriptions for surgical and medical prophylaxis were also recorded.

The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) classification, developed by the World Health Organization, was used to categorize prescribed antibiotics in this study. This framework groups antibiotics according to their spectrum of activity, risk of promoting AMR, and recommended clinical use: Access antibiotics are first- or second-line agents for common infections with a lower resistance risk; Watch antibiotics have broader spectra and higher resistance potential, requiring closer monitoring; and Reserve antibiotics are last-resort treatments for suspected or confirmed multidrug-resistant infections and should be used sparingly under strict stewardship oversight.

Additionally, a predefined set of antimicrobial quality indicators was assessed, including documentation of the indication and stop/review date, the availability of local prescribing guidelines, and compliance with these guidelines. Built-in validation checks within the Global-PPS platform and centralized oversight ensured the accuracy and completeness of the collected data.

Study settings

This first Global-PPS in Burkina Faso was conducted across eight hospitals located in six cities, including the two main urban centers, Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso. The study included the main public hospitals in the western and southern parts of the country (4 health regions) and one specialized hospital in the central region (Ouagadougou), as shown on the map (Figure 1). The healthcare structure in Burkina Faso, comprising 49 primary, nine secondary, and six tertiary hospitals, illustrates the uneven distribution of diagnostic and human resources, with primary and secondary hospitals facing the greatest constraints.

Figure 1. Map of Burkina Faso showing the surveyed hospitals (KABORE D., 2023). DH, district hospital; RH, regional hospital; SSUH, Sourô Sanou University Hospital; CDGUH, Charles de Gaulle University Hospital.

Together, the selected hospitals accounted for approximately 12% of all national hospital beds, providing a meaningful though not exhaustive snapshot of AMU across the country. The sample included:

-

Two tertiary hospitals (Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso), one of which was a specialized pediatric and neonatal hospital.

-

Three secondary-level hospitals (Banfora, Dédougou, and Gaoua) serve as regional referral centers.

-

Three primary-level hospitals, including two in Bobo-Dioulasso and one in Dano, represent the first line of hospital-based healthcare delivery.

All hospitals had facilities for basic biochemistry and hematology testing, while only the secondary and tertiary hospitals were equipped with microbiology services, including bacterial culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. However, at the time of the survey, none of the hospitals had an active AMS program in place.

This selection reflects the diversity of hospital infrastructure and diagnostic capacities in Burkina Faso’s public health system and allows the survey to highlight variations in AMU across healthcare levels

Data analysis

All data were entered directly into the Global-PPS web-based application and anonymized before analysis. The dataset included hospital-, ward-, and patient-level information from all eight participating hospitals, with no data excluded.

Data were extracted from the Global-PPS platform and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (version 2019). Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations, as appropriate. The prevalence of AMU was defined as the number of inpatients receiving at least one antimicrobial agent divided by the total number of inpatients surveyed on the day of data collection.

Comparisons of categorical variables between hospitals and ward types were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when expected cell counts were <5. All analyses followed standard Global-PPS methodology to ensure consistency and comparability across sites.

Results

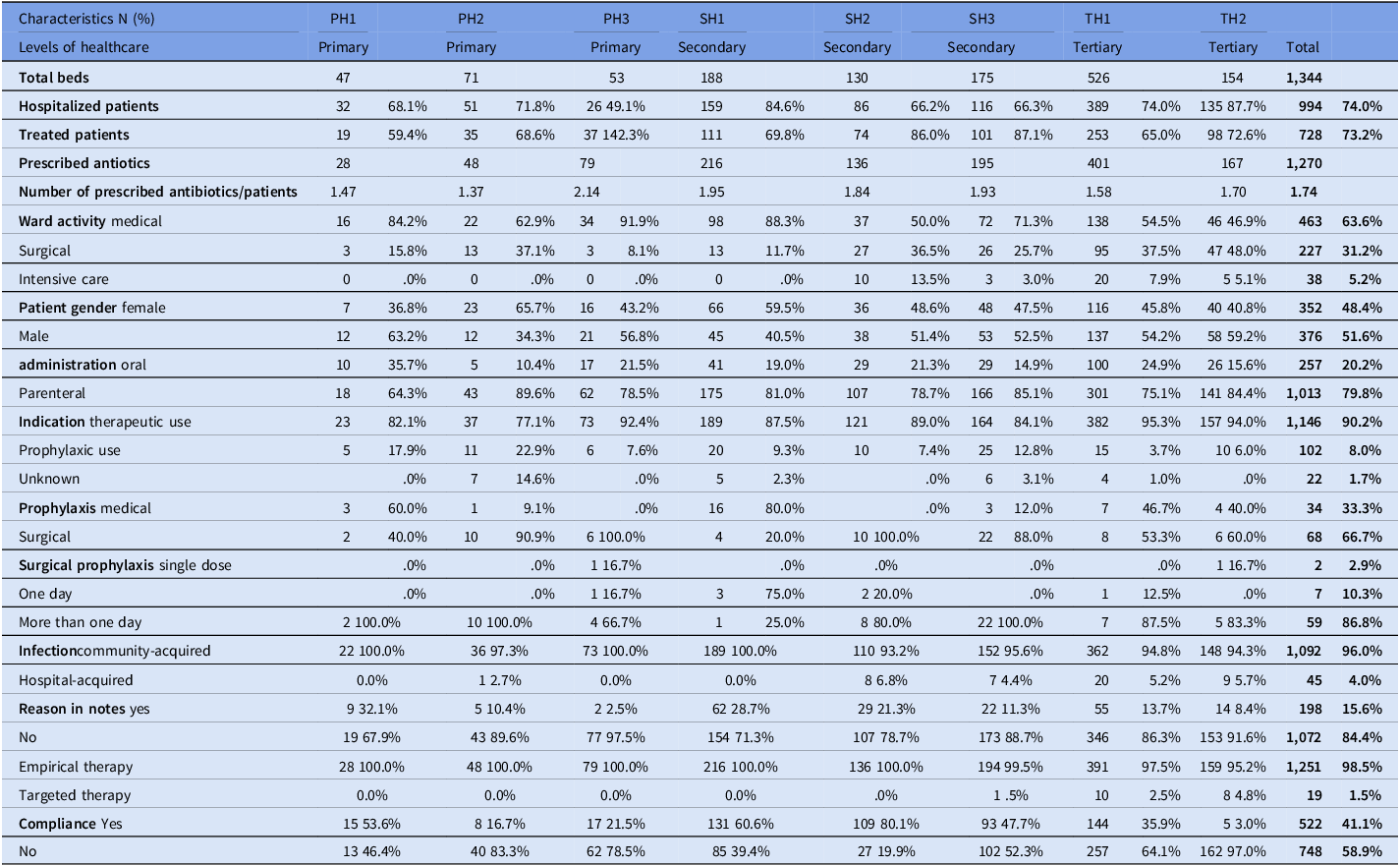

Characteristics of participating hospitals and eligible patients

On the day of the survey, a total of 1,344 beds and 994 inpatients were surveyed across all eight (8) hospitals, accounting for a bed occupancy of 74.0%. The patients treated with at least one antimicrobial had an average age of 18 years and a median age of 7 years.

Prevalence of antimicrobial use

A total of 729 out of 994 patients received at least one antimicrobial during the day of the PPS (73.3%). The prevalence of AMU varied according to hospital care levels: 71.6% (range 59.4%–92.3%) in primary, 79.2% (range 69.8%–87.1%) in secondary, and 69.7% (range 65.0%–83.0%) in tertiary facilities. Despite these differences, the variation was not statistically significant (p-value = .461). Additionally, no statistically significant correlation was found between bed occupancy rate and prevalence of AMU (p-value = .424) as summarized in Tables 1 and 6.

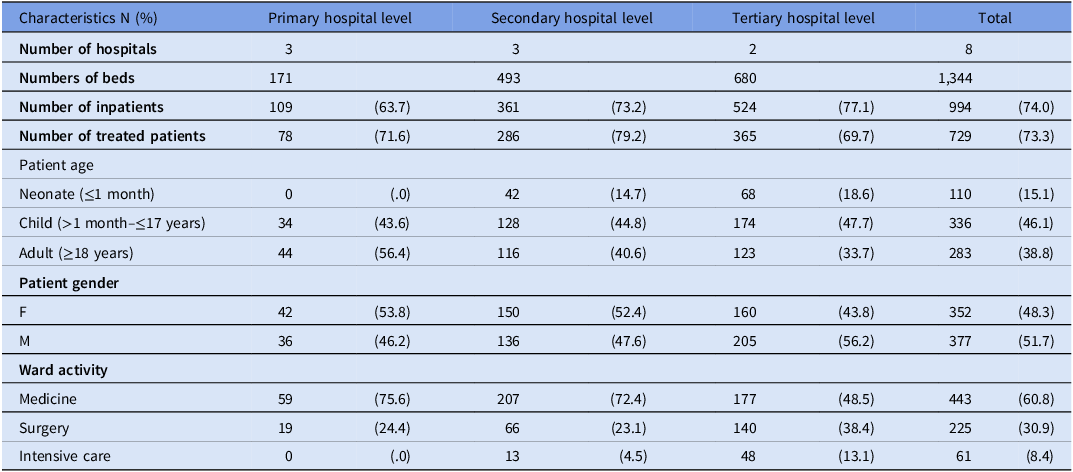

Table 1. Characteristics of wards and patients (treated with at least one antimicrobial) per hospital tier level

Table 1 provides a summary of the patients surveyed based on the tiered level of the hospital. The study included a higher number of children than adults or neonates. Tertiary hospitals had a larger proportion of neonates (18.6%) and children (47.7%) surveyed compared to primary hospitals, where adults were more commonly encountered (56.4%). The wards where patients were surveyed varied depending on the hospital-tiered level. Patients in intensive care wards (IC) constituted the smallest proportion of those surveyed, with only 4.5% and 13.1% of patients in secondary and tertiary hospitals, respectively.

Reason for prescribing antimicrobials

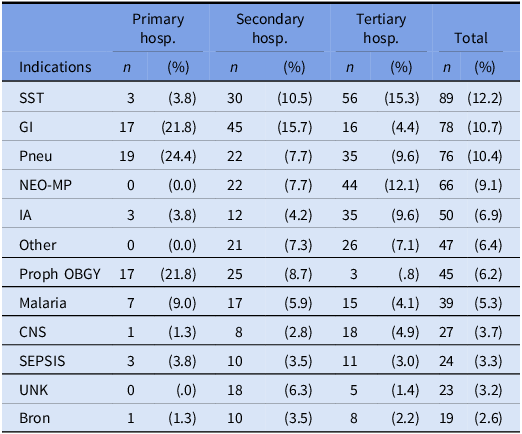

Across all hospitals, the most reported reasons for prescribing antibiotics (ATC J01) were skin and soft tissue infections (12.2%) and gastrointestinal infections (10.7%). However, there were slight variations between the hospital care levels, with pneumonia or lower respiratory tract infections being the most common reason in primary care hospitals (24.4%) and medical prophylaxis for newborn risk factors being the second most common reason in tertiary hospitals (12.1%) (Table 2). Overall, therapeutic use accounted for 90.2% of antimicrobial prescriptions, with CAI infections being the main type of infection leading to AMU (95.7%). Surgical prophylaxis of >1 day (SP3) was common in all hospitals, accounting for up to 86.8% of all prescriptions for surgical prophylaxis (Table 6).

Table 2. Top 12 indications of antimicrobial use per hospital tier level

SST, skin and soft tissue; GI, gastrointestinal infections; Pneu, pneumonia or lower respiratory tract infections; NEO-MP, Drug is used as medical prophylaxis for NEWBORN risk factors; IA, intraabdominal sepsis including hepatobiliary; Proph OBGY, prophylaxis for obstetric or gynaecological surgery; CNS, infections of the central nervous system; UNK, completely unknown indication; Bron, bronchitis; Hosp, hospital.

Commonly used antimicrobials

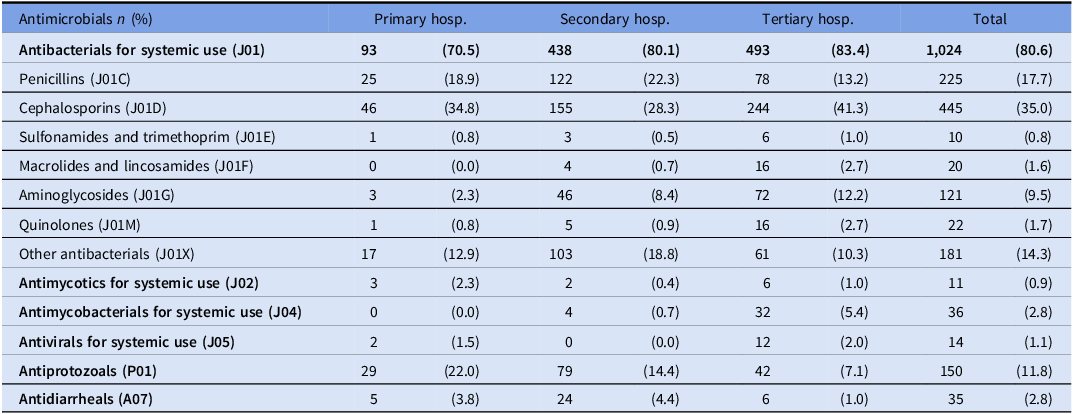

Out of all antimicrobials, antibacterials for systemic use accounted for 80.6% of prescriptions. Cephalosporins (J01D) and Penicillin (J01C) were the most prescribed antibiotic classes across all the different hospital levels, comprising 35.0% and 17.7% of prescriptions, respectively (Table 3). According to the WHO AWaRE classification, antibiotics of the Access category were the most frequently prescribed and accounted for 52% of all prescriptions, while antibiotics in the Watch category were the second most frequently prescribed (48%), representing 37%, 49%, and 57% of prescriptions in secondary, primary, and tertiary hospitals, respectively. No antibiotics from the Reserve category were prescribed in any of the surveyed hospitals (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Antibiotic use according to WHO AWaRe classification. PH, primary hospital; SH, secondary hospital; TH, tertiary hospital.

Table 3. Class of antimicrobial used according to the three healthcare levels

Hosp, hospital.

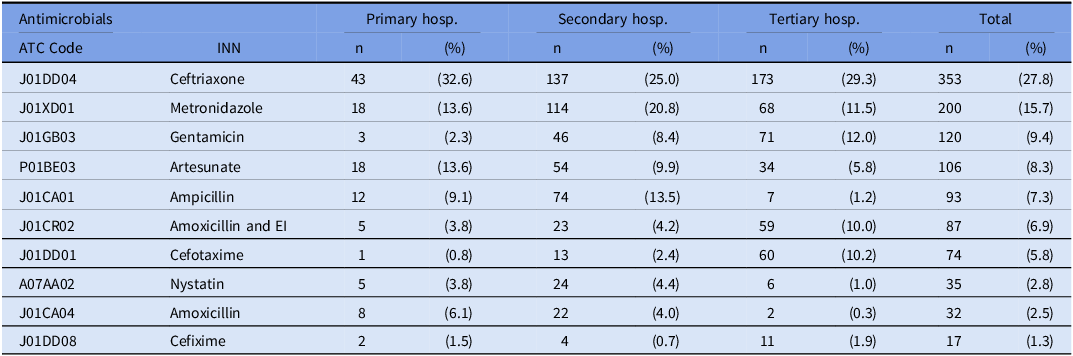

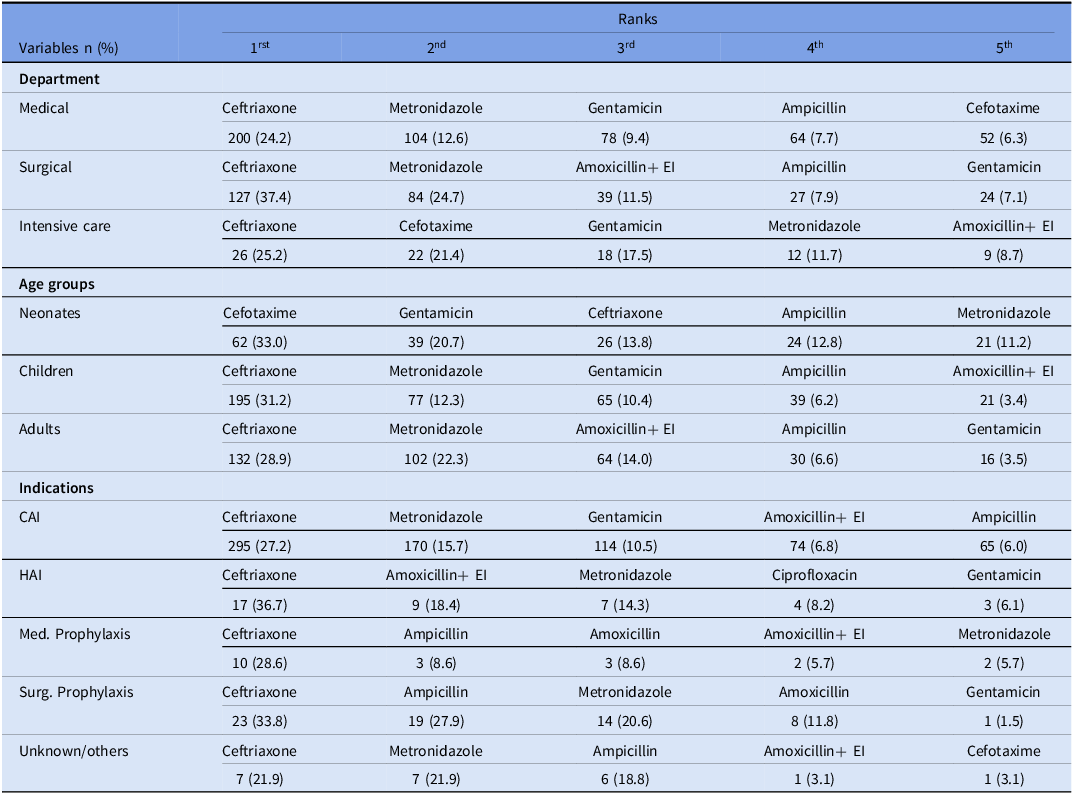

Common antibiotics according to the department, the age, and the indications

The top three most prescribed antibiotics were ceftriaxone (27.8%), metronidazole (15.7%), and gentamicin (9.4%) as presented in the following table (Table 4). Ceftriaxone was found to be the most frequently used antibiotic for therapy and prophylaxis, with a proportion ranging from 27.2% to 36.7% of prescriptions, averaging 24.2% in medical departments and 37.4% in surgical departments (Table 5). In addition to the top three antibiotics, a relatively high usage of ampicillin (7.3%) and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (6.9%) was observed. Cefotaxime was commonly used in neonate patients (33.0%) and the ICU (21.4%).

Table 4. Top 10 antimicrobials per tiered level

ATC, anatomical therapeutic chemical; EI, enzyme inhibitor; Hosp, hospital; INN, International Nonproprietary Names.

Table 5. Top 5 antibiotics according to department, age, and indications

EI, enzyme inhibitor; CAI, community-acquired infection; HAI, healthcare-associated infections; Med. Prophylaxis, medical prophylaxis; Surg. Prophylaxis, surgical prophylaxis.

Quality indicators for prescribing

During the survey, quality indicators were recorded for all prescriptions using specific criteria, as shown in the table below (Table 6). A stop/review date was not documented in the medical records for 93.0% of the antimicrobial prescriptions. The indications were not documented in 15.5% of the prescriptions. Guideline compliance for prescriptions was observed in 40.2% of cases, and varied widely among the eight hospitals, ranging from 3.0% in one tertiary hospital to 78.7% in one secondary hospital. Empirical therapy accounted for 98.3% of all prescriptions.

Table 6. Overall antimicrobial use prevalence N = 1,270

PH, primary hospital; SH, secondary hospital; TH, tertiary hospital.

Discussion

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) remains a pressing global challenge, exacerbated by the overuse and misuse of antibiotics in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face disproportionate challenges due to limited resources, inadequate diagnostic capacities, and unregulated access to antibiotics. Reference Murray2,Reference Pasquale, Trienski and Olexia6,Reference Ouedraogo, Pierre, Bañuls, Ouédraogo and Godreuil13,Reference Da, Somé and Carine14

This first national Global-PPS in Burkina Faso revealed an alarmingly high prevalence of AMU, with 73.3% of hospitalized patients receiving at least one antimicrobial (69.7%–79.2% across facilities). These rates are more than double the global average (34.4%) and markedly higher than those in high-income countries (23.7%–62%) Reference Versporten, Zarb and Caniaux3 and neighboring Ghana (55%), Reference D’Arcy, Ashiru-Oredope and Olaoye9 though similar to Nigeria (70.7%) Reference Umeokonkwo, Oduyebo and Fadeyi5 and parts of Asia (up to 85.7%). Reference Versporten, Zarb and Caniaux3 These high AMU rates reflect systemic pressures, i.e, empirical treatment due to limited diagnostics, insufficiently trained personnel, and weak stewardship oversight, particularly in primary and secondary hospitals. These findings underscore the urgent need to strengthen hospital governance, prescriber education, and laboratory support to promote rational antibiotic use. Reference Ouedraogo, Pierre, Bañuls, Ouédraogo and Godreuil13,Reference Sana, Kaboré, Ouédraogo, Traoré, Saybou, Saybou and Semdé15,Reference Yehouenou, Nagalo, Kabore and Ouedraogo16

Most antibiotics (95.7%) targeted CAI infections, predominantly skin/soft-tissue (12.2%), gastrointestinal (10.7%), and pneumonia (10.4%). These findings mirror trends in Egypt Reference Talaat, Saied and Kandeel17 and other LMICs, where CAIs dominate due to the burden of infectious diseases linked to poor sanitation and hygiene. Reference Umeokonkwo, Oduyebo and Fadeyi5,Reference Ouedraogo, Pierre, Bañuls, Ouédraogo and Godreuil13 Parenteral administration was predominant, reflecting clinical habits common in resource-limited settings. Reference D’Arcy, Ashiru-Oredope and Olaoye9

Ceftriaxone, metronidazole, and gentamicin were the most frequently prescribed antibiotics, consistent with regional studies. Reference Enimil, Agbedinu and Yeboah18,Reference Haseeb, Faidah and Algethamy19 Beta-lactams were the dominant class, as reported elsewhere, Reference Versporten, Zarb and Caniaux3,Reference Umeokonkwo, Oduyebo and Fadeyi5,Reference D’Arcy, Ashiru-Oredope and Olaoye9,Reference Porto, Goossens, Versporten and Costa20,Reference Panditrao, Shafiq and Chatterjee21 though over-reliance on these drugs raises concern, given the rising resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. The heavy reliance on Watch-group antibiotics, such as ceftriaxone, despite national guidance restricting its use in primary care, reveals gaps in prescriber adherence and enforcement of stewardship policies. Encouragingly, Reserve-group antibiotics were rarely used, likely due to their high cost and limited availability in the absence of national health insurance. Strengthening regulatory enforcement and promoting adherence to national guidelines remain crucial to preserve antibiotic efficacy.

Quality indicators further revealed suboptimal prescribing practices: nearly all prescriptions lacked review or stop dates, and 15% lacked documented indications. Guideline compliance averaged only 40%, varying by hospital level. Interestingly, adherence tended to be higher in lower-level facilities. Variations across hospital levels may reflect differences in clinician experience and case complexity. While general practitioners in primary and secondary hospitals often rely more strictly on standard protocols, tertiary clinicians managing complex cases may deviate due to the lack of specialized local guidance.

A key barrier identified was the limited use of microbiological diagnostics, with 98.5% of prescriptions empirically based. Despite laboratory capacity in tertiary and some secondary hospitals, utilization remained low due to test costs, lack of insurance coverage, and frequent pretreatment with antibiotics that compromise culture results. To address this, the National AMR Action Plan (2024–2027) prioritizes upgrading laboratories, piloting microbiology units in primary care, and expanding the national AMR surveillance network from 15 to 26 sentinel sites. 22 These actions aim to enhance diagnostic-guided therapy and strengthen evidence-based stewardship. Reference Ouedraogo, Pierre, Bañuls, Ouédraogo and Godreuil13,Reference Sana, Kaboré, Ouédraogo, Traoré, Saybou, Saybou and Semdé15,Reference Yehouenou, Nagalo, Kabore and Ouedraogo16

Following this initial survey, several national AMS initiatives have been rolled out. These include the National Antibiotic Prescription Guideline (first released in 2021, revised in 2023), integrating WHO AWaRe principles, and the National Action Plan for Rational Antimicrobial Use in Hospitals. 12,23 These guidelines have been tailored to local epidemiology and informed by data from the national laboratory-based AMR surveillance network. 24 Prescribers from secondary and tertiary hospitals have received training on applying the national guidelines and integrating the AWaRe classification into their decision-making processes. Additionally, since 2017, an average of 500 healthcare professionals across Francophone West and Central Africa have been trained during an Inter-University Diploma course on AMR (www.diu-antibio.org/), organized annually by national universities and partners. Approximately half of these participants have come from all healthcare levels of the Burkinabe healthcare system, ensuring broad capacity building for evidence-based prescribing decisions. In parallel, Pharmaceutical and Therapeutic Committees have been institutionalized in all tertiary and secondary hospitals, some extending to primary care, to oversee AMS implementation and individualized drug dispensation. The national pharmaceutical regulatory authority now conducts annual antimicrobial consumption surveys to monitor progress. A second round of the Global-PPS is ongoing and will evaluate progress and guide corrective actions.

Implementation of the first PPS faced expected challenges. Initial apprehension among clinicians, concerned that results might expose poor practices, was mitigated by Ministry of Health endorsement and strong engagement of hospital managers. Mobilizing young general practitioners as data collectors and using the standardized Global-PPS online platform facilitated efficient data collection and validation. However, funding constraints limited geographic coverage and individualized feedback. Key findings were instead disseminated through quarterly national AMS meetings, ensuring that results informed national interventions.

Despite limitations, ie., non-random sampling, regional concentration, and inclusion of only ∼ 12% of national hospital beds, this survey provides baseline data for Burkina Faso’s AMS strategy. It has directly influenced policy design, stewardship training, and laboratory strengthening. Repeat PPS rounds, currently underway, will assess progress in stewardship implementation and identify persistent barriers to rational antibiotic use.

Overall, this first nationwide survey revealed extensive AMU in Burkinabe hospitals, largely empirical and driven by system-level constraints. Nonetheless, it has catalyzed policy reforms, guideline development, and stewardship actions that lay a foundation for sustained improvements in antimicrobial rationalization. Repeating the PPS will be essential to measure progress and ensure continued momentum toward responsible antibiotic use essential for long-term containment of AMR in Burkina Faso.

Data availability statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Global-PPS repository and can be accessed upon reasonable request to the coordination team at the University of Antwerp.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the technical staff and the management of all 8 surveyed hospitals, and the General Practitioners recruited for the data collection.

Author contributions

A.V.: developed the concept and the protocol; A.N.: Coordinated the implementation of the project, analyzed the data, and developed the first draft of the manuscript; O.D.K.: contributed to the first manuscript writing; O.S.M.: Contributed to the data collection and analysis; A.-S.O.: Initiated the project and was the scientific advisor of the study; All authors reviewed the manuscript and made corrections. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

The Global-PPS of Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance was supported by bioMérieux. The study funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. For this specific study, the financial resources were used to support the data collectors and logistic fees.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

Administrative authorization for the survey was granted by the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso, under reference number N°2019/0718/MS/SG/ANRP/CeDIM. This study did not require formal approval from an institutional ethics committee because it involved no direct patient contact and utilized fully anonymized data collected as part of routine hospital care.