On 26 August 1970, a small group of French women carrying a banner declaring ‘[t]here is someone more unknown than the Unknown Soldier: his wife’ attempted to lay wreaths on the tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arc de Triomphe in a carefully orchestrated and highly provocative symbolic gesture. It was one of the earliest public demonstrations carried out by the post-1968 French feminist activists who were to form the core of the Mouvement de libération des femmes (Women’s Liberation Movement).Footnote 1 Widely reported in the press (journalists were informed in advance), this theatrical action was designed, according to one of the participants, ‘to denounce [women’s] oppression in a spectacular and humorous fashion’.Footnote 2 Fifty years after the ceremonies for the Unknown Warrior had taken place in Paris and London, this new generation of feminists cast the tomb as the ultimate symbol of the hegemony of masculinist culture, as a synecdoche for the oppression, belittling and silencing of women under patriarchy. Although the context and politics were very different, a similar sense of dissatisfaction with what was understood as women’s exclusion from war commemoration was evident in the campaign for the British ‘Women and World War II’ memorial unveiled in 2005.Footnote 3 In a press release, Betty Boothroyd, former speaker of the House of Commons who galvanised the campaign, stated how proud she was ‘to finally see a memorial to the wonderful women who contributed so much to the war effort’, adding that John Mills’ sculpture would ‘make a symbolic and dramatic tribute’.Footnote 4 The chosen location of the memorial in Whitehall, its design and positioning boldly mirroring those of the Cenotaph, guides the public to interpret the memorial as a corrective to the perceived absence of women from Edwin Lutyen’s 1920 national war memorial. This intention is summed up in the response of Edna Storr, one of the trustees of the memorial and a former Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) worker: ‘It’s a wonderful sculpture. Best of all, it’s going next to the Cenotaph. We are going to stand side by side, with the men, where we belong.’Footnote 5

Historians have concurred that First World War memorials and other commemorative discourses constructed a male-dominated vision of gender roles that either excludes or offers a highly restricted interpretation of women’s contributions and experiences during the war. John Gillis concludes for example that ‘for the women who had contributed so much to the world’s first total war effort, there would be no monuments.’Footnote 6 Daniel Sherman, taking a Foucauldian understanding of the oppressive and insidious nature of patriarchal power structures as a theoretical framework, argues in similar vein that French interwar war memorials and their unveiling ceremonies, planned and designed by committees dominated by men, functioned to express and to attempt to allay the anxieties of a nation threatened by the perceived erosion of traditional gender roles in wartime. Taking his lead from Mary Louise Roberts’ analysis of interwar French novels, memoirs and journalism by ex-servicemen that criticise perceived changes in social mores,Footnote 7 Sherman summarises that ‘commemoration served to reinscribe gender codes that World War I had disrupted in France … [it] played out, in gendered terms, a pervasive cultural unease in which nothing less than the masculine cast of politics and of national citizenship was at stake.’Footnote 8 Sherman thus argues that both men and women were calcified into a limited number of allegorical roles that functioned to differentiate the sexes according to pre-war gender imperatives: ‘Men were active, heroic, resourceful […] women were grieving, suffering, emotional’.Footnote 9

But did commemorative culture in the wake of the First World War operate exclusively as an oppressive force, ‘sculpturally consigning post-war women to conventionally gendered roles’?Footnote 10 Clearly, the principal female function in commemorative discourse in both Britain and France was as the bereaved wives and mothers of servicemen, echoing not only their primary relation to the deaths being commemorated but equally a traditional understanding of women’s role as domestic.Footnote 11 Yet, as I argue in this chapter, women’s relationship to commemoration in the interwar years was more proactive, more dynamic and more varied than has frequently been suggested. The grieving widow or mother was not the only version of female identity found on war memorials and represented in unveiling ceremonies. Further, not only did thousands of women actively respond to and participate in the rites and rituals of commemoration, but women also instigated, planned, designed and sculpted memorials and ceremonies, shaping rather than being shaped by interwar commemorative culture. In so doing, women were presented as war veterans in two ways. First, some war memorials were designed to commemorate the sacrifices of whole communities to the war effort, and not only the sacrifices of the dead. In these memorials to ‘total war’, women were included in the evocations of those who had been on active service, and who therefore deserved the respect and recognition of their community and country. Second, memorials that commemorate women who died or who were killed in the war often presented the deaths of such women as war deaths, thereby aligning them with the deaths of servicemen. The discourse of sacrifice in the service of the nation had implications for the relationship of these women to the state, especially in France where an inscription of ‘mort pour la patrie’ (‘died for the fatherland’) necessarily evokes the tenets of Republican citizenship.

Over the past twenty years, the historiography of First World War commemoration has sometimes constructed what is essentially a false dichotomy between the private/psychological and public/political meanings and uses of war memorials. In this chapter, I take memorials to be public and politicised sites that mediated private grief; one does not and cannot exclude the other.Footnote 12 Both Sherman’s study of France and Alex King’s study of Britain reveal the diverse motivations inherent in the planning and erection of war memorials, reminding us that these enterprises ‘entailed assembling resources and creating a large audience, … [offering] funds which could be put to philanthropic uses, a market for artists, a platform for politicians’.Footnote 13 Commemoration in the interwar period was mostly done by committee, and necessitated frequent negotiation and compromise between the various stakeholders involved, including ex-servicemen, local organisations and businesses, the bereaved, donors, fund-raisers, municipal and sometimes national authorities, religious leaders and urban planners and developers.Footnote 14 Jay Winter has shown how women responded privately to war memorials as mourners, the ceremonies acting as rites de passage on route to what Winter refers to, deploying a Freudian optic, as the ‘necessary art of forgetting’.Footnote 15 What has been less discussed, however, is the extent to which women as well as men exploited the public opportunities that commemoration offered, taking up as they did so a variety of roles: as wealthy patrons influencing the aesthetics and ideological messages of memorials, as volunteers or charity workers furthering or publicising philanthropic causes, as members of a profession remembering colleagues and promoting their achievements or, occasionally, as suffragists, lending weight to arguments that sought to claim full citizenship for women.

In this chapter I discuss two different aspects of women’s relationship to commemoration: the meanings ascribed to female figures in memorials and ceremonies, and interventions by individual women in the planning, designing and sculpting of war memorials. These aspects are frequently interlinked, as women’s interventions often resulted in the construction of alternative visions of womanhood to those that cast women as mourning mothers or as allegorical embodiments of an abstract quality or nation. These alternative visions of women as having actively served in the war necessarily evoked claims for memory and recognition that were often grounded in the political or ideological beliefs of the instigators, funders or designers of the memorial.

Women as Citizens

Despite the predominance of women cast as bereaved mothers, wives or sisters in monuments and ceremonies, women appeared in other guises in commemorative discourse in the interwar years, some of which complemented and some of which competed with their primary roles as mourners. The nurse was the most familiar and most acceptable symbol of female service and sacrifice during the war.Footnote 16 In the cultures of commemoration in the interwar period it retained its position as the dominant way in which women’s contribution to the war effort was represented in both Britain and France. The nurse was set up as an idealised role model that had broad appeal, being easily subsumed into dominant conceptions of femininity while also being positioned as a female equivalent of mass male mobilisation.Footnote 17 Many evocations of the wartime nurse thus drew on traditional understandings of women’s rights and roles, and offered reassuringly domesticated versions of mobilised women on active service during the war. Yet within the cultures of commemoration, representations of the wartime nurse frequently had different, even competing, objectives. While some drew on conceptions of nursing as an extension of women’s maternal or domestic role in order to make their wartime service embody abstract values such as humanity, civilisation, reconciliation and healing, others positioned nurses as citizens, their work being understood in this context as an admirable example of an individual’s fulfilment of civic or patriotic duty to the nation.

Certain evocations of the nurse in the interwar years effectively combine the roles of nurse and grieving woman, the nurse depicted as a pietà with a dead or wounded soldier presented as a Christ figure. This is particularly the case in France, where interwar commemoration was permeated, as Annette Becker notes, by the ‘religious and mystical realm … when Judeo-Christian catechisms were entwined with the secular gospels of patriotism’.Footnote 18 The war memorial in Charlieu (Loire) (Figure 1.1) is of this type. Sculpted by Christian-Henri Roullier-Levasseur and unveiled in 1922, it features a nurse wearing a First World War uniform and cradling a dead French soldier, his helmet by his side. This rare appearance of a realist sculpture of a uniformed nurse on a French memorial is perhaps explained by the fact that the Mayor of Charlieu was Jean Louis Vitaud, who had worked as a doctor in the French army during the war.Footnote 19 A similar depiction of a nurse caring for a dying soldier can also be found on a plaque in the Eglise Saint-Louis des Invalides in Paris that is dedicated to French Red Cross nurses. In the foreground, a uniformed nurse is bandaging the wounds of a prostrate soldier while in the background a ruined French village burns. Despite their contemporary dress, the nurses in these memorials are recognisable as Marian figures, the ancient Stabat Mater dolorosa. A nurse is also central to the 1922 memorial in Saintes (Charentes-Maritime), sculpted by Emile Peyronnet, in which a bent-headed nursing sister supports a prostrate soldier. Here, the nurse embodies a maternalist vision of the French Republic, caring and grieving for its dead, as well as offering a powerful depiction of the healing power of womanhood in the wake of war.Footnote 20

Figure 1.1 War memorial, sculpted by Christian-Henri Roullier-Levasseur, Charlieu (Loire), 1922.

In Britain, however, nurses who appear on First World War memorials tend to be positioned in similar poses to soldiers, rather than in maternal, nurturing or grieving mode. In this way, they served to embody the sacrifices and contributions made by women to the war effort, a feminised version of masculine war service. Some of these memorials overtly positioned them as citizens who have been on active service, despite the fact that very few women were named on the list of the fallen. The war memorial in Bold Venture Park, Darwen, Lancashire, for example, sculpted by Louis Roslyn and unveiled in 1921, features a tall square pedestal with bronze reliefs on three of its sides representing a soldier, sailor and a nurse, while at the top of the pedestal stands a winged figure representing Victory.Footnote 21 The nurse is in First World War uniform, but unlike the French examples she is not evocative of religious iconography. Her sleeves are rolled up, she is carrying the tools of her trade like the soldier carries his rifle, and she wears a medal as proof of the value of her service to the state. Her dress, pose and gaze mirror those of the war-weary men on the other reliefs. It is possible that Roslyn was influenced by George Frampton’s 1920 memorial to Edith Cavell, as the word ‘Humanity’ is engraved below the nurse, expressing a specifically female brand of wartime sacrifice, whereas beneath the male military figures is the word ‘Freedom’.

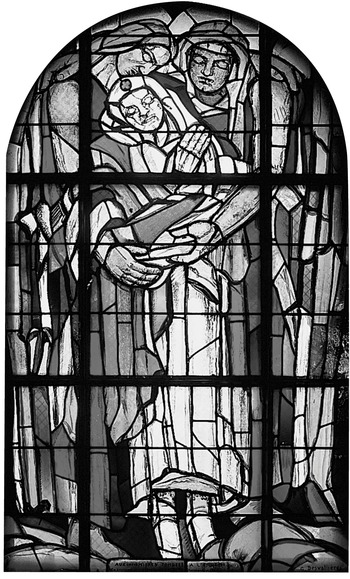

A similar conception of nursing as the feminised version of male military service, although this time understood in terms of a Catholic conception of martyrdom, is found in the stained-glass windows of the memorial chapel at the national ossuary in Douaumont in France, painted and designed by George Desvallières in 1927 (Figure 1.2).Footnote 22 All of the windows in the chapel revolve around the theme of sacrifice and redemption, with two of them devoted to a nurse and a soldier who are presented as sainted martyrs, ascending to heaven in the arms of angels. Having converted to Catholicism in 1904, in 1919, Desvallières set up the Atelier d’art sacré, with painter Maurice Denis, with the aim of revitalising religious art.Footnote 23 Male and female sacrifice embodied in the figures of soldier and nurse is also present in the frieze Desvallières painted for the private chapel of Jacques Rouché at Saint-Privat, which he completed in 1925. In ‘Dieu le père’ (‘God the Father’) (1920), Jesus holds a protecting cloak over a French soldier (modelled on Desvallières’ dead son, Daniel) and nurse who kneel side by side, while the Virgin Mary welcomes them into heaven.Footnote 24 The nurse in the stained-glass window memorialises three French nurses killed when their hospital was shelled in 1917, but the nurse has a greater symbolic function.Footnote 25 As Jean-Philippe Rey notes, in Desvallières’ redemptive vision the idealised nurse–soldier couple becomes representative of humanity: ‘The sacrifice of the soldiers becomes the remedy for sin. The communion of saints is restored, the chosen couple (poilu and nurse) intercedes on behalf of the inhabitants of the earth.’Footnote 26 Desvallières himself was explicit about the meaning of his depiction of the soldier and nurse in this respect: ‘On the left and on the right, the great Angels accompany the Ascension of our Saviour, lifting in their powerful arms the two heroes of the war: the Soldier who died for his country, and the Nurse, who sacrificed herself for those who suffered and died.’Footnote 27 Thus, while the nurses who appear on Roslyn’s Darwen memorial and in Desvallières’ religious art are placed within different conceptions of sacrifice – civic and religious – in both cases, the sexes are not placed in a hierarchical relationship, but side by side. Men and women are understood as having been united by a collective spirit of sacrifice. The nurse’s and the soldier’s contributions are therefore presented as having some degree of equivalence, and as metonymically standing in for the sacrifices made by the broader community of those on active service.

Another British memorial that offers a vision of collective sacrifice in its presentation of ‘total war’ is located in St Mary’s Church Memorial Gardens in Rawtenstall, Lancashire (Figure 1.3). This memorial, also sculpted by Louis Roslyn, features a tapered granite obelisk with bronze reliefs beneath which show various figures including soldiers, sailors, airmen, a farmer, a miner, a nurse, a woman and child, a fisherman, a medical orderly, a railwayman and a labourer. In this vision of wartime life, each member of the community offers his or her own form of service and sacrifice, propping up the four ‘pillars’ of the servicemen who are strategically placed at the four corners of the frieze. It was instigated by a wealthy local woman, Carrie Whitehead, who also unveiled it in 1929 (Figure 1.4).Footnote 28 There had been prolonged debate in Rawtenstall as to what form the memorial should take. Initially, a memorial swimming bath was proposed ‘as a suitable and useful War Memorial’. This fell through, and local authorities received letters from both the British Legion and Carrie Whitehead proposing alternatives.Footnote 29 It is clear from the 1929 unveiling ceremony that it was Whitehead’s vision that won through. Her speech underlined the ways in which the committee intended the memorial to represent the sacrifices of a whole community – including women – during the war:

The War Memorial Committee has erected this tribute of honour not only for the men who have left us but for all who took part in winning safety for our Empire. The architect who has designed it has had our desires in view. There is nothing sad in the colour of the granite, nor in the artistic shading of its bronze, the figures carved round it are full of life as they march along. … This tribute of honour has a threefold link. It is erected in honour of those who made the supreme sacrifice, it is erected in honour of those who fought for us and got back, some, thank God, physically fit, some halting and maimed and blinded who will suffer on for our sakes, all the days of their lives, and it is erected in honour of all who worked strenuously at home to help to win the war: to the miners, the munition workers, the land workers, the manual and textile workers, the matrons, sisters, nurses and girls who worked in our hospitals, and to the women the men left behind them to carry on in their homes …, the women who did their bit day and night to keep the home fires burning.Footnote 30

Figure 1.3 War memorial, sculpted by Louis Roslyn, Rawtenstall, 1929.

Figure 1.4 Carrie Whitehead.

In this example, it is not just the procession and audience at the unveiling that functions to represent all facets of a community, but the iconography of the memorial itself. Carrie Whitehead was elected to the town council in 1920 as Rawtenstall’s first female councillor, and in the 1930s became Alderman and served on the magistrate’s bench and as Mayor.Footnote 31 She was deeply involved in community life, serving on multiple committees, as did many unmarried and childless women of her class. Although she was not an active suffragist, the war memorial reflects her belief in the importance of women’s contributions in wartime, and its inscription deliberately emphasises the fact that the memorial is erected to honour the sacrifices of male and female civilians as well as those of servicemen: ‘A tribute of honour to the men who made the supreme sacrifice/ to the men who came back/ and to those who worked at home/ to win safety for the Empire’.

It is apparent from her speech that Whitehead was aware that the committee’s decision might be controversial, and she defended the memorial from accusations of disrespect for the dead. Other commentators, while not rejecting its meanings completely, were quick to emphasise elements that shore up more traditional understandings of gendered roles in wartime. The newspaper report published a letter from the local vicar that placed the emphasis back upon the widow and child as embodiments of bereavement:

If the artist’s idea was to remind future generations … of four years of close and solid cooperative effort, when class distinctions were well-nigh swept away in face of a common danger and for the sake of a common cause … then indeed the artist has admirably achieved his purpose. … I am particularly glad that the mother and child are represented, for it was my lot to witness their long anxiety and lonely grief, and the noble part they played.Footnote 32

The journalist reporting on the ceremony was careful to stress the superiority of the dead serviceman’s sacrifice, ‘the gallant dead who are the most alive of all [Rawtenstall’s] citizens’, while commenting that ‘the most poignant group were the widows and children of the fallen.’ As the discussions of the Rawtenstall memorial show, evocations of women’s sacrifice in wartime could relate both to their bereavement and to their efforts as paid or unpaid war workers. Memorials that emphasise collective struggle and sacrifice tend to pay attention to both of these aspects, offering as they do so a broad definition of service that encompasses a wide variety of wartime activities, including those carried out by women and other non-combatants.

An emphasis on active service and communal sacrifice in wartime, this time on a national scale, is also central to the Scottish National War Memorial in Edinburgh Castle, which was finally unveiled in 1927 after being first mooted as a possibility during the war, and to the enormous painting of more than 5,000 French and Allied figures entitled the ‘Panthéon de la guerre’ (‘Pantheon of the War’), begun in Paris in 1914 and first exhibited two weeks before the Armistice. Both are interesting examples of patriotic and militarist memorials that sought to carve out a space for women’s contributions – albeit within carefully designated and controlled parameters – within their commemorative discourse. The Scottish National War Memorial was the brainchild of the Duke of Atholl, who dominated the committee, and largely reflects his nationalist-Unionist and Presbyterian beliefs.Footnote 33 Its genesis lay initially in Atholl’s anger at an announcement made in 1917 by Commissioner for Works Sir Alfred Mond that the National War Memorial in London would be a site ‘in which he was sure that Highland Regiments would be proud to put their trophies and be memorialised’.Footnote 34 The memorial aims to be comprehensively inclusive, embracing Scottish contributions to the war effort made by all Scots both at home and abroad. This was partly for financial reasons: the memorial cost more than £100,000, and propaganda and fund-raising efforts ‘played on the shared sense of Scottishness throughout the diaspora’.Footnote 35 But its inclusivity also serves to emphasise a shared sense of the losses borne and service rendered by a whole nation.

The theme of collective sacrifice resonates throughout the iconography of the memorial, with bays in the Hall of Heroes dedicated not only to the twelve Scottish regiments and to Scots who were killed serving in other regiments, but also to non-combatants and to various auxiliary services, including women’s services. In the bay dedicated to non-combatants, the viewer is even asked to ‘[r]emember also the humble beasts that served and died’, with an accompanying panel depicting canaries and mice, and a frieze featuring the heads of various transport animals, both by sculptor Phyllis Bone.Footnote 36 At the heart of the memorial is an octagonal shrine with a bronze frieze sculpted by Alice Meredith-Williams, who also sculpted the bronze panels to the Women’s Services and Nursing Services in the south-west bay of the Hall of Heroes. This detailed frieze is reminiscent of Roslyn’s Rawtenstall memorial, in that it reproduces a series of figures performing different war-related tasks, incarnating the collective efforts necessitated by total war. The Scottish example, however, containing seventy-four figures, includes a greater variety of combatant, auxiliary and non-combatant roles, from members of the Russian Expeditionary Force wearing snowshoes and of the Imperial Camel Corps in shorts and sun helmet, to chaplains, munitions workers, signallers, drivers, pipers and air mechanics, all carrying symbolic tools of their trades. The female figures include nurses and members of the main auxiliary services, the WAAC, Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) and Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF). The women may come last in the procession, but their realist uniforms, poses and positioning mirror those of the men they stand alongside. The inscription in the shrine – ‘The souls of the righteous are in the hands of God. There shall no evil happen to them. They are in peace.’ – strongly suggests to the viewer that this is a procession of the glorious dead, resuscitated by the remembrance of the living. Angus Calder argues that the procession ‘moves like a herd of doomed creatures’, equating them to Wilfred Owen’s ‘those who die as cattle’.Footnote 37 Yet the theme of redemption and resurrection is omnipresent in the Scottish National War Memorial, suggested in particular by Charles d’Orville Pilkington Jackson’s statue entitled ‘Réveillé’ over the doorway of the Hall of Honour, which represents purification through sacrifice. The prominence of this statue serves to distance Meredith-Williams’ frieze from Owen’s bleaker vision.Footnote 38 If the theme of redemption through sacrifice is familiar to interwar commemoration, the inclusion of male and female non-combatants in the frieze, and the fact that in the memorial more generally evocations of combatants are accompanied not only by those of male and female auxiliaries but also by scenes from the home front such as factory work and air raids, troubles a simple hierarchy in which grateful civilians pay homage to sacrificial servicemen. Combatants and non-combatants, men and women, are included in the procession of the ‘glorious dead’ by virtue of their efforts in wartime; all are situated as deserving of national gratitude and commemoration.Footnote 39 This desire for inclusion was repeated in the unveiling ceremony, in which the Duchess of Atholl wore her VAD uniform and presented the women’s Roll of Honour, followed by uniformed representatives of different women’s services.Footnote 40

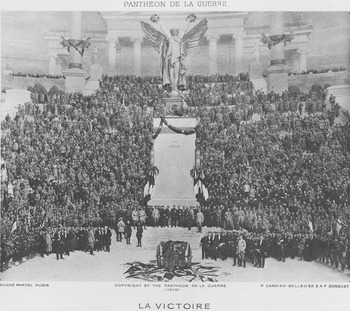

There are interesting parallels between the frieze in the Scottish National War Memorial and the ‘Panthéon de la guerre’ memorial painting, which was produced by twenty artists under the leadership of Pierre Carrier-Belleuse and Auguste-François Gorguet. Billed as the ‘world’s largest painting’, the ‘Panthéon’ was an enormous cyclorama of the war featuring about 5,000 individual full-length portraits of men and women from the Allied nations. It was unveiled to great public acclaim by President Raymond Poincaré on 19 October 1918 in a special building constructed near the Hôtel des Invalides.Footnote 41 The largest section of the painting featured a ‘Temple of Glory’ devoted to France’s heroes. René Bazin’s preface to the catalogue when the work was first exhibited describes the scene in terms of a ‘Sacred Union’ of French men and women rising up in unison to defeat an old enemy: ‘For four years, a magnificent multitude has risen up from our towns and countryside, a mass of young people, relatives and friends, who have suffered and struggled to such an extent that the enemy, who had been preparing for war for a long time, did not succeed in their aim to bring the Fatherland to its knees.’Footnote 42 The portraits of the French heroes were placed on an enormous staircase and organised according to rank, with generals and other civilian leaders occupying the base (Figure 1.5). While the majority were servicemen, several women were included in their number. The roll call of French heroines included the usual suspects of nurses, resistant nuns and brave employees of the French postal service who defied the enemy advance. Names lauded by the press and decorated by the state, such as Emilienne Moreau, Edith Cavell, Louise de Bettignies, Soeur Julie and Jeanne Macherez, all featured.Footnote 43 The Pantheon painters did not stray far from propagandists in their choices of which women deserved recognition as war heroines.Footnote 44

Figure 1.5 ‘Panthéon de la guerre’, Staircase of Heroes, 1918.

Directly facing the Staircase of Heroes was a war memorial, on the top of which was a cenotaph held aloft by four French infantry soldiers in bronze. At the base of the memorial, and dwarfed by its size and scale, knelt a weeping widow cloaked in black, head bowed, grieving and paying tribute. Here, then, was woman as the embodiment of a nation in mourning for all its dead heroes, whether officially recognised as such or not, her wreath bearing the inscription ‘Aux héros ignorés’ (‘To the unknown heroes’). Yet it remains significant that she was not the only female figure in the painting. Opposite her were scores of women whom the painters designated as exceptional, and who took their place on the staircase deserving of civilian praise and gratitude like the servicemen (many of whom had been killed in action) that they stood beside.

The ‘Panthéon de la guerre’ should be understood as a ‘home-front-based view of the war’, which ‘lost credibility as combatants started narrating their own trench experiences’.Footnote 45 Unlike the Scottish National War Memorial, it was begun in the early days of the war, and its aesthetic and ideological messages became less palatable in the interwar years. But like Roslyn’s memorial in Rawtenstall and Meredith Williams’ frieze in Edinburgh, the ‘Panthéon de la Guerre’ depicted women as actively involved in the war effort in order to construct an ‘imagined community’ of citizens who had suffered and sacrificed together, and who were subsequently united in mourning for their dead. This vision was summed up in the text written by Charlotte Carrier-Belleuse, daughter of the painter and secretary of the ‘Panthéon’, which was produced to accompany a coloured slide show that toured the country in 1919. Her narrative guided the audience to perceive all French citizens as unified in their sacrifices and glories. As the first slide was shown, for example, the narrator would read the following words, as if addressing the painted subjects being described:

Here is the imposing crowd: generals and soldiers with your decorated chests, civilians, victims of your devotion, eminent prelates …, women, young girls, valiant nurses who cared for your wounded on the very battlefields; all of you, the heroes of France, enter this Temple of Glory triumphantly, Victory is smiling proudly and opening her golden arms to you. For her, you have selflessly spilled your generous blood, here she is, superb, shining down, lighting up your foreheads with her dazzling splendour and scattering laurel leaves at your feet.Footnote 46

Members of the audience were invited not only to pay their respects to their heroic countrymen and women but were equally interpellated themselves as French citizens who may have also served or sacrificed family members during the war, and who deserved a place in the Victory parade. Of course, this vision of unity was far removed from the schisms and discord that were often a feature of interwar debates not only about the meanings and hierarchies of ‘war sacrifice’, but also about the ways in which the war should be remembered and commemorated. It also failed to address the fact that the continued disenfranchisement of the ‘heroines of France’ necessarily set them apart from their male counterparts. In terms of the gendered meanings of war commemoration, however, all of the examples discussed in this section carved out a space not only for women as mourners, grieving and paying tribute to the war dead but equally for women’s active contributions to the war effort. This use of female figures in commemorative discourse extended women’s role beyond that of civilians bereaved, and placed them firmly in the realm of a community of active citizens who had also served.

Women as Veterans

The memorials that constructed a vision of a community united in collective sacrifice still distinguished, though, between the kinds of service carried out and sacrifices offered by men and by women. Nurses were praised for the way in which they extended their ‘devotion’ and ‘humanity’ beyond the home front to the front itself. They were presented as having acted out to the full a specifically female brand of service to their nation, supporting, nurturing and healing the servicemen who were often designated symbolically as their sons or brothers. Other First World War memorials, however, and particularly those that commemorated the relatively few women who were killed on active service during the war, presented women not as feminised citizens but as female veterans, as more direct equivalents of dead servicemen.Footnote 47

Women who were killed in the war proved valuable commodities in forms of political communication designed to tarnish the enemy, as the examples of martyr-heroines Edith Cavell and Louise de Bettignies that I discuss in Chapter 2 demonstrate. Helen Gwynne-Vaughan, Chief Controller in France of the WAAC, makes this point in her memoirs when describing the media response after nine members of the corps were killed during a bombing raid in 1918: ‘When I got back to my headquarters I found a group of journalists in the mess all wanting a story and prepared to execrate the enemy for killing women.’Footnote 48 During the war, women’s deaths were also reported widely in the press, emphasising in the reports a community united in its shared sacrifices. In Britain, nurses and mercantile marine stewardesses had a high profile; in France, ‘invasion heroines’ dominated the early years, before being replaced with nurses and prisoners of war in the later war years as the press’ favoured female victims.

Many women who died, especially nurses or those who worked for the British auxiliary services, were given full military funerals. In Britain, there was a debate in late 1917 between the Army Council and the War Office as to whether members of the WAAC were entitled to a government-funded military funeral, but despite some resistance from the War Office it was agreed that WAACs should have the right to funded funerals.Footnote 49 After the war, however, the commemoration of women who had died on war service took different forms and served different purposes. While to some extent, like all commemorations, interwar memorials and ceremonies functioned as a focus for private grief, those exclusively devoted to female deaths were equally, and in some cases primarily, vehicles for public messages about women and their contribution to the war. Some used women’s deaths as a means of flagging up the sacrifices and importance of certain professions or voluntary groups who had served in the war, while others used the possibilities offered by the ‘ultimate sacrifice’, the ‘blood tax’ paid by a few women, in order to proclaim publicly the validity of all women’s claims to full citizenship.

While nurses sometimes featured in national commemorations of the dead, there were also memorials instigated by nursing organisations themselves, both volunteer and professional, commemorating the deaths of their members. The commemorative discourse in these memorials combined private mourning with public affirmation of the women’s deaths as honourable war deaths, underlining the organisations’ sacrifices and devotion to the nation, and thereby implicitly demanding public recognition and gratitude. A French example of this kind of memorial to nurses was unveiled in 1923 after having been commissioned by one of the three organisations that made up the French Red Cross, the Union des Femmes de France (UFF) (Union of Women of France). The sculptor was Berthe Girardet, who had herself nursed for the UFF during the war, and who produced several commemorative pieces in the interwar years.Footnote 50 It was unveiled in the headquarters of the UFF in Paris, and comprised a bas-relief featuring a group of nurses, with two plaques listing forty-eight UFF members who had died during the war. UFF president Mme Henri Galli described the bas-relief in the following terms during the commemoration ceremony: ‘With profound artistry fed by superior intelligence, and with religious sensibility, [Mme Girardet] has been able to reproduce the solemn dignity and the intense interior life exuded by these faces … which, as if they had haloes, have the character of religious icons.’Footnote 51 These Red Cross nurses thus embraced, at least to some extent, dominant conceptions of nurses as transhistorical incarnations of saintly womanhood. The 1923 ceremony, however, which took place during a monthly meeting of the UFF nurse–veterans’ association, functioned equally to shore up the identity of the Red Cross nurses as veterans. The president’s speech directly aligned the nurses’ deaths with the ‘supreme sacrifice’ made by soldiers:

The emotions that bring us together today are sorrow and grief, but also pride, and we reverently pay homage to the memory of these valiant women who paid with their life for the fervent sense of altruism, heroic devotion and superior and patriotic virtues that they possessed. … Let the memory of the generosity of the nurses’ lives that you grieve for …, of the good that they did, … and finally the memory that they too served France as her heroic defenders, that they carried out the noblest of missions, let these poignant memories relieve your suffering.Footnote 52

The discourse here is familiar from unveiling ceremonies for war memorials that took place in every town and village in France and Britain in the years following the Armistice, in which the grieving audience was ‘urged to convert its grief to pride’, except that the subjects of grief, gratitude and glorification were women rather than male combatants.Footnote 53

It is a discourse that was repeated in other commemorative activities for First World War nurses that took place after the Armistice. The 1919 report by board member Colonel de Witt-Guizot on the activities of the Société de Secours aux Blessés militaires (SSBM) (Society to Aid Wounded Soldiers) used overtly military language and nationalist imagery when evoking the wartime deaths of the Society’s nurses:

If I could I would invite you to stand, shout ‘Attention’ and call for the playing of the Last Post. … To honour their memory I want the General Secretary to establish a ‘Roll of Honour’ which, when read in schools and in family homes, will remind our children that French women spilled blood for them on the sacred ground of their homeland … and future generations will pass on their names, wreathed in glory.Footnote 54

Similarly, the newspaper article recounting the unveiling ceremony of the Irish Nurses’ Memorial, in Arbour Hill Garrison Chapel, Dublin, in 1921, was entitled ‘What Sacrifice May Teach’, and the Rev C. A. Peacocke’s sermon, while praising the Irish nurses for ‘showing the highest qualities of womanhood’, equally asked the congregation to ‘go away strengthened, helped and lifted up’ after seeing in the memorial ‘a wonderful record of service, of character, of fortitude, of the highest and best gifts that God gave to man and woman’.Footnote 55

Many commemorations of female nurses who died on war service contained in this way a blend of traditional images of nurses as icons of womanhood with a discourse that set up their deaths as quasi-military sacrifices for the defence of the nation, or of civilisation itself. During the service held for the unveiling of the Scottish Nurses’ War Memorial at St Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh in 1921, for example, General Sir Francis Davis simultaneously praised the ‘sympathy and magic touch’ of the nurses as ‘ministering angels’, while stating that the memorial should serve as an example to future generations, asserting: ‘These ladies did not earn their crown in the day of battle. They earned it in the patient discharge of their duty, some killed by enemy action, victims of the malice of our foes’.Footnote 56 In France, the report of the unveiling of the ‘Monument à la memoire des infirmières’ (‘Monument to the Memory of Nurses’) in Berck-sur-Mer (Pas de Calais), unveiled in 1924, recognised the ‘sublime role’ and ‘unceasing devotion’ of the nurses while emphasising that they had ‘fallen on the field of honour’, and noting that the ceremony ended with ‘the tricolor, the flag of glory and gratitude, that covered the monument being slowly raised’.Footnote 57 The equation of nurses killed in the war with the male war dead is equally discernible in a statue designed by Maxime Réal del Sarte, a prolific nationalist sculptor of war memorials and Joan of Arc devotee, for the ‘Monument national aux infirmières françaises tuées à l’ennemi’ (‘National Monument to French Nurses Killed in Action’) in Pierrefonds (Oise).Footnote 58 This 1933 statue featured an androgynous pietà figure with outstretched arms supporting the body of a dead nurse, whose arms are also outstretched and who is dressed in medieval clothing reminiscent of Joan of Arc. Its design reverses in gender terms many pietàs that feature on French war memorials, including some examples by Réal del Sarte himself, in which the body of a Christ-like French infantryman is supported in the protective embrace of a Mary or Joan of Arc figure.Footnote 59

While military authorities and veterans tended to prioritise transcendent feminine virtues in memorials to nurses killed in the war, nursing organisations themselves tended to place the emphasis more on the risks to life and health of wartime nursing in a bid to underscore the value of their service to the state. In 1922, the British Military Nurses Memorial Committee, chaired by Matron-in-Chief Sarah Oram, commissioned a statue for St Paul’s cathedral by sculptor Benjamin Clemens entitled ‘Bombed’ (that was ultimately not accepted by the cathedral authorities due to lack of space), a commission that suggests a desire for a representation of nursing work that emphasised front-line risk.Footnote 60 The sculpted figures on the Scottish nurses’ memorial in St Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh are also interesting in terms of the meanings with which they are charged. The stylised female figure on the left is kneeling, her head bowed, carrying a wreath, while the warrior-like female figure on the right holds her head upright and carries a dagger in her hand. Above the statues are a list of the Scottish members of the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) and Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR) killed in the war. The iconography of this memorial pointed to the dual role of the nurses, both as mourners paying tribute to their lost colleagues and the men they nursed, and as active participants who risked death.

In sum, although it is true, as Sherman notes, that in the majority of commemorative activities ‘unlike dead soldiers women … could serve as models only as remembering subjects paying tribute to men’, the ceremonies that commemorated women who had been killed in the war challenged, whether directly or indirectly, an understanding of war service and sacrifice based exclusively on gender.Footnote 61 In raising the dead nurses to the level of lost combatants, the nursing organisations were, on one hand, attempting to comfort bereaved families, and, on the other, making public, political gestures. Judith Butler argued in relation to the commemoration of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York that ‘the obituary functions as the instrument by which grievability is publicly distributed. It is the means by which a life becomes, or fails to become, a publicly grievable life, an icon for national self-recognition, the means by which a life becomes noteworthy.’Footnote 62 This insight is relevant to the interwar context in which certain individuals and organisations were claiming lost female lives as ‘publicly grievable’ sacrifices for the nation.

The impulse to recognise the deaths of women war workers as equivalent in status and meaning to those of combatants was particularly evident in national monuments to women killed in the war that were erected in France and Britain. The ‘Monument à la gloire des infirmières française et alliées victimes de leur dévouement’ (‘Monument to the Glory of French and Allied Nurses, Victims of Their Devotion’) was unveiled in Rheims in 1924. Its committee was presided over by eighty-eight-year-old Juliette Adam, well-known feminist and femme du monde who had converted to Catholicism in the early 1900s.Footnote 63 The iconography of Denys Puech’s sculpture clearly drew on the familiar, Catholic-inspired French vision of nurses as grieving pietàs over the dead Christ/poilu (Figure 1.6). If the figures placed the nurse in a familiar position of idealised maternal devotion, however, the memorial’s inscription aligned the work of nurses with that of soldiers: ‘On land and sea, they shared the soldier’s dangers. They braved, in shelled and torpedoed hospitals, enemy fire, contagion and exhaustion. In relieving suffering, they aided victory. Let us honour them. They will forever live in the memory of their proud and grateful nations.’ The design and inscription were undoubtedly influenced by the sentiments of the committee’s chair, Juliette Adam, reflecting her religious faith and her fervent patriotism as well as her continued support for women’s rights, including the right to vote. The genesis of the Rheims nurses’ memorial was not sparked by private grief but by the committee’s, and particularly Adam’s, desire to express publicly a combination of religious, nationalist and feminist beliefs.

Figure 1.6 ‘Monument à la gloire des infirmières françaises et alliées victimes de leur dévouement’, Rheims, sculpted by Denis Puech, 1924.

A strident Germanophobe, Adam wrote in a letter at the outbreak of the war that ‘[c]ertain words are ringing in my head: France, Fatherland, Alsace-Lorraine’, and her speech at the unveiling ceremony reiterated her revanchiste sentiments, expressing the wish that the monument should be a ‘call to arms for future nurses’ as she felt that the hopes of pacifists were illusory given her experiences in two wars against the same enemy.Footnote 64 If one of her aims was to celebrate France’s victory against the ‘old enemy’ and warn against future attacks, another was to promote feminist causes, particularly female suffrage, through the glorification of women’s war work and war deaths. Like the majority of French feminists, and particularly in her later years, Adam espoused moderate Republican reformist feminism, adhering to the rhetoric and ideology of ‘separate spheres’ in order to argue for the need to recognise women’s particular contribution to the state.Footnote 65 Her speech, like the monument’s inscription, draws on traditional understandings of nurses’ ‘feminine’ virtues, describing the ‘courageous devotion’ of the ‘heroic victims’, while at the same time underlining the equivalence of their sacrifice to that of male combatants. One way in which the latter is done is through the compilation of a ‘Livre d’or’ (‘Roll of Honour’) listing 979 names of Allied nurses who died in France, with an accompanying inscription on the monument stating that ‘[t]he town of Rheims will faithfully keep in its archives the Roll of Honour of these noble women who fell on the field of honour.’Footnote 66

Thomas Laqueur argues that the extensive naming of the dead of the First World War, particularly significant for the hundreds of thousands of cases of missing bodies, was ‘an enormous and unprecedented part of … the memorials of the war’. Naming a soldier (and especially a common soldier who might normally have expected to be buried anonymously in a common grave) was to individualise, to commemorate and to dignify him without necessarily limiting the meaning of his death to a specific ‘cause’, to resort ‘to a sort of commemorative hyper-nominalism’.Footnote 67 Recording, inscribing and sacralising the names of women who had died as a result of war service was thus a way of integrating their deaths within the mainstream of First World War commemoration. In the case of the Rheims monument, other officials followed Adam’s lead and embraced her categorisation of the nurses as ‘mort[es] pour la France’. Sub-Prefect of Rheims M. Mennecier, for example, declared ‘on behalf of the government’ in his speech that:

Today, perhaps for the first time, but forever more, we will proclaim together in front of this monument, illuminated like other monuments by the glory of sacrifice, that it is right and necessary to unite in our gratitude, as they have already been united in immortality, the names of soldiers killed in action with the names of these admirable nurses who also, and in their thousands, responded to the call to arms, risked life and limb in order to carry out their duties.Footnote 68

Thus, while the iconography of the Rheims memorial to Allied nurses positioned them as ‘ministering angels’, the ‘livre d’or’ and other inscriptions placed their deaths squarely within the framework of military commemoration.

A similar desire to construct women as veterans deserving of gratitude and recognition can be seen in a British memorial to women killed in the Great War that was unveiled in York Minster in 1925. The memorial consisted of the restoration of the ‘Five Sisters’ Window’ and the erection of an oak screen with a Roll of Honour naming 1,513 women from Britain and the Dominions who died as a result of war service.Footnote 69 The fund-raising for the memorial was carried out by two women, Helen Little, a colonel’s wife who was involved in nursing work in Egypt during the war, and Almyra Gray, a suffragist, former president of the National Council for Women Workers (which became the National Council of Women) (NCWW), local magistrate and social reformist.Footnote 70 The memorial was in part agreed to by the Chapter and Dean of York Minster because of the desperate need for funds to restore the stained glass windows, which had been removed and buried because of the threat of bombing in 1916.Footnote 71 The women carried out the fundraising independently, and raised the £3,500 needed in nine weeks.Footnote 72 The publicity material, as for many memorials, emphasised the extent to which the memorial could be a unifying force for women from different social classes, highlighting donations from Princess Mary at one end of the spectrum, and ‘an aged woman pensioner [who] gave a week’s pension’ at the other.Footnote 73 Through Almyra Gray’s international connections, forged through her work with the NCWW, the memorial committee also organised ceremonies to be carried out simultaneously in Canada, South Africa and Australia, thereby emphasising the contributions of what Gray referred to as the ‘Imperial sisterhood’.Footnote 74

Like Adam, Little and Gray were motivated by a combination of religious, patriotic and feminist beliefs in their desire to erect a memorial to women who died in the war. In a letter to The Times published at her request after her death in 1933, Helen Little narrated a vision that she claimed lay behind the memorial project:

On November 30, 1922, I had the following vision: I was going into Evensong and entered by the South Transept door as usual. Just as I reached the choir door in the dim light I saw two little figures in white standing hand in hand in the middle of the North Transept: one beckoning to me, the other pointing upwards to the window. I moved towards them, and then recognised my two little sisters, both of whom had died as children. As I followed the little pointing finger I saw the window move slowly backwards as if on hinges, revealing the most exquisite garden … a number of girls and women … came gliding up the garden in misty grey-blue garments. They came nearer and nearer … I looked down and saw that both my little sisters were pointing upwards to the window. I had risen in my sleep, and was standing when I woke, and cried out, my words being heard by my husband – ‘The Sisters’ Window for the Sisters’.Footnote 75

Little’s mystical vision is redolent of the rise in popularity of spiritualism, and the many cultural representations of the ‘return of the dead’ that were produced during the interwar period. Such representations functioned, as Martin Hurcombe notes, ‘not … to reassure the living but to unsettle and to challenge them’, embodying a ‘metaphor of redemptive sacrifice that suggests the debt owed to the war dead and, by association, to … veterans’.Footnote 76 Little’s dead sisters in the vision functioned to remind her (and by extension the memorial’s viewers) of the sacrifices made by, and the debt owed to, the ghostly ‘girls and women’ who died in the war. She stressed the duty of living women to remember these dead ‘sisters’, a duty that was effectively fulfilled via the inscription on the painted Roll of Honour: ‘This screen records the names of women of the Empire who gave their lives in the war 1914–1918 to whose memory the Five Sisters’ Window was restored by women.’

At the same time, as Hurcombe argues, representations of the returning war dead implied by extension a debt of gratitude to all veterans, in this case specifically to female veterans. This was a vital function of both the Rheims and York memorials, whose erection was about the debts society owed to the living as well as to the dead women war workers. The Five Sisters’ Memorial in particular flagged up the dual roles of women, as mourners carrying out acts of remembrance, and as active participants, united in Little’s vision in a kind of mystical universal sisterhood. The public aims of the York memorial were openly acknowledged by the memorial committee. In the same letter, for example, Little stated:

During the early part of the war I was present when the first trainloads of wounded arrived at Cairo from Gallipoli, and was witness to the untiring devotion under great difficulties of the nurses and other women who gave themselves up, entirely regardless of their own health, in some cases with fatal results, to alleviate the suffering of the men. After the war was over, when memorials on all sides were being erected to our brothers, I often thought that our sisters who also made the same sacrifice appeared to have been forgotten.

Here, she expressed the desire to endow female sacrifices with the same status as male sacrifices, implying that war commemoration in the 1920s had been hitherto inadequate in its acknowledgement of the part played by women.

The glorification of female war work was no doubt one of the reasons the scheme appealed so readily to suffragist and social activist Almyra Gray, who mobilised ‘mayoresses, teachers, nurses, the Branches of the National Council of Women, members of Women’s Institutes, organized Units and many others’ to great effect.Footnote 77 The two women also went to great lengths to compile as full a list as possible of the dead, corresponding with numerous government departments in Britain and in the Dominions.Footnote 78 The unveiling ceremony on 26 June 1925 was designed to highlight similarities between male and female service and sacrifice. While the Duke of York unveiled the York municipal war memorial erected to the 1,162 men of York killed in the war, the Duchess of York did the same for the Five Sisters’ Window memorial in the Minster. The Duke of York inspected troops and addressed veterans; the Duchess of York inspected guards of honour composed of seventy female VADs of the North Riding of York British Red Cross Society and fifty Girl Guides.Footnote 79 The address by Cosmo Lang, Archbishop of York, underscored this message in his address, making a direct reference to the 1918 Representation of the People Act as another ‘great memorial’ to women’s war service: ‘Through [the window’s] pure and delicate colours there now shines and will ever shine the light of service and self-sacrifice which ennobled the women of our land and Empire in the dark days of the Great War. … Their loyalty, efficiency and devotion have already won a great memorial in the gift to women of full citizenship of the Empire.’Footnote 80

Conclusion

Hundreds of thousands of women actively participated in the rites and rituals of commemoration. For some, memorials to both men and women were focuses of private mourning for friends and relatives. The York Minster archives, for example, contain letters from relatives of the named women, expressing their pride and gratitude for the public commemoration of their loved ones.Footnote 81 For others, memorialisation constituted an opportunity to make a bold public statement about women’s value to the state as volunteers or workers during a period of crisis, and to demand the recognition and rewards this deserved. The latter role was generally confined to a small majority of socially and politically elite women, and thus reflected their political and class interests as well as their religious or ideological beliefs. Juliette Adam, Helen Little and Almyra Gray were all elite women whose roles on war memorial committees were motivated at least in part by a drive to include women in the ranks of the ‘glorious dead’, and thereby stake a claim for the importance of women’s sacrifices for the nation during the war.

As the examples in this chapter demonstrate, moreover, it was not only committed suffragists or feminist activists who manifested a desire to construct women as honourable citizens or as veterans deserving of civilian gratitude, equating their war activities with those of the millions of male combatants who died. Indeed, the Duchess of Atholl, who was intimately involved along with her husband in the decision to commemorate women’s services as part of the Scottish National War Memorial, was a noted anti-suffragist before the war and opposed equal suffrage in 1924.Footnote 82 It is true that in both nations feminists regularly turned to women’s war service as possible leverage in their women’s rights campaigns. Yet the rhetoric in the unveiling ceremonies of memorials to dead nurses, including that of French Republican politicians, church and army officials, many of whom were anti-feminist, also aligned these women to male combatants and demanded the gratitude and respect of viewers and attendees. In both nations, women’s deaths, like those of militarised men, were frequently placed within a patriotic, Christian-inflected understanding of sacrifice. The women were presented as having died, Christ-like, to save not only their nation, but civilisation itself.Footnote 83 It is important to acknowledge that for all the rhetoric of women’s quasi-military sacrifice there was clearly no equivalent risk in women’s war work – not only were the numbers killed a fraction of those of male combatants, but the relative risk to life (the ‘blood tax’) was also low.Footnote 84 However, female service and sacrifice was not absent from interwar commemoration. Women in the interwar period often enacted a living image of female service, by parading in uniforms at unveiling ceremonies.Footnote 85 Memorials were erected to women who had died on active service, thereby raising their deaths to the level of ‘supreme sacrifice’. In so doing, they implicitly elevated the activities of surviving women workers, particularly nurses who could claim an element of risk and who fell within pre-existing understandings of women’s sphere of influence, to the level of patriotic service for the nation, thereby aligning them with veterans.

First World War memorials were multilayered sites in which notions of women’s sacrifice intersected with other social, political and religious discourses – imperialism, Christianity, patriotism and feminism – that inflected the versions of female service and citizenship that the memorials attempted to express.Footnote 86 The existence of competing and sometimes contradictory messages in memorials is inherent in their nature. The conversion of individuals into abstract generalisations meant that it was possible to interpret the figure of a nurse, for example, in a number of different ways: as martyr, as embodiment of a nation, as pietà, as essence of womanhood, as a health professional or as a female combatant. The extent to which the memorial to women in York Minster was acceptable to a wide range of ideological and political positions is shown by the guest list to its unveiling, which reads like a ‘Who’s Who’ of British women’s war service. Alongside Quaker pacifist Ruth Fry were those fighting for improvements in women’s professional lives, such as nurse leaders and female doctors, as well as the leaders of the women’s auxiliary services and other organisations that had been prominent in the war. Yet church leaders and male members of the military and political establishment were also present at the service.Footnote 87 Although their individual reactions are not recorded, the very presence of such a diverse congregation supports the proposition that the rhetoric of female sacrifice and service could be recast to suit the ideological and political positions of a wide range of men and women in the interwar years.