Introduction

The prevalence of common mental disorders continues to stand as a critical public health challenge of global significance (Have et al., Reference Have, Tuithof, Dorsselaer, Schouten, Luik and de Graaf2023). Mental disorders were among the top 10 leading causes of burden globally (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022), with age-standardized disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) increasing by 16.4% for depressive disorders and 16.7% for anxiety disorders between 2010 and 2021(GBD 2021 Diseases and injuries Collaborators, 2024). Based on data from the Global Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2021, one study reported the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in China across provincial administrative units (Tian et al., Reference Tian, Yan, Xiong, Zhang, Peng, Zhang, Zhou, Liu, Zhang, Ye, Zhao and Tian2025). Substantial gaps in prevalence data of mental health conditions persist globally, particularly in low-income countries (Abdalla & Galea, Reference Abdalla and Galea2024; Casella et al., Reference Casella, Kousoulis, Kohrt, Bantjes, Kieling, Cuijpers, Kline, Kotsis, Polanczyk, Stein, Szatmari, Merikangas, Mneimneh and Salum2025). In data-sparse regions, substantial reliance on modeling approaches was necessitated, resulting in expanded uncertainty intervals for the estimates (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators, 2016). The regional mental health survey was still needed in view of the distinct epidemiological characteristics.

The National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China has designated the years 2025–2027 as the “Years of Pediatric and Mental Health Services”(National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, 2024). According to previous reports, mental health issues in China are associated with a range of challenges, including limited access to mental health care, stigma, and a lack of public awareness (Li, Stanton, Fang, & Lin, Reference Li, Stanton, Fang and Lin2006; Liang, Mays, & Hwang, Reference Liang, Mays and Hwang2018; Xiang, Ng, Yu, & Wang, Reference Xiang, Ng, Yu and Wang2018; Xu, Rüsch, Huang, & Kösters, Reference Xu, Rüsch, Huang and Kösters2017; Yin et al., Reference Yin, Wardenaar, Xu, Tian and Schoevers2020). Despite these concerns, comprehensive, up-to-date epidemiological studies on mental health in China remain scarce. The most recent nationwide survey of mental disorders in China was conducted between 2013 and 2015 (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu, Yu, Yan, Yu, Kou, Xu, Lu, Wang, He, Xu, He, Li, Guo, Tian, Xu, Xu and Wu2019), while the latest epidemiological survey of mental disorders in Beijing, the capital city, was completed in 2010 (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yan, Ma, Guo, Tang, Rakofsky, Wu, Li, Zhu, Guo, Yang, Li, Cao, Li, Li, Wang and Xu2015). Recent large-scale surveys in China have primarily focused on screening for mental symptoms (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Wu, Liu, Fan and Wang2025; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Lu, Que, Huang, Liu, Ran, Gong, Yuan, Yan, Sun, Shi, Bao and Lu2020; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Tan, Li, Huang, Zheng, Hou and Wang2022) rather than providing a definitive diagnosis. Given the considerable differences in prevalence trends and clinical significance between these two approaches, this distinction is crucial. The results of two censuses conducted a decade apart reveal that Beijing’s permanent resident population experienced a decline in the male-to-female ratio, accelerated population aging, a rising proportion of ethnic minorities, an increase in residents with tertiary education, and further advancement in urbanization (Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics, 2021). The prevalence of mental disorders in the general population is dynamic and influenced by multiple factors, yet accurately predicting the direction and magnitude of these changes remains challenging. An updated and region-specific survey is urgently needed to accurately assess the prevalence of mental disorders in Beijing.

Previous epidemiological studies on mental disorders have faced several methodological constraints. First, reliance on two-step screening approaches (initial screening followed by diagnostic assessment) may compromise prevalence accuracy due to threshold effects and low diagnostic confirmation rates (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Wong, Hussain, Tsoi, Ma, Chau, Ma, Lai, Chu, Lo, Ho, Leung, Yiu, So, Sham, Hung and Leung2025; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Lu, Zeng, Yang, Liao, Hou, Zheng and Wang2025; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Dong, Ding, Hou, Tan, Ke, Jia and Wang2023; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding, Pang, Li, Zhang and Wang2009; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Stevelink, Gafoor, Lamb, Carr, Bakolis, Docherty, Dorrington, Gnanapragasam, Hegarty, Hotopf, Madan, McManus, Moran, Souliou, Raine, Razavi, Weston, Greenberg and Wessely2023; Yin et al., Reference Yin, Phillips, Wardenaar, Xu, Ormel, Tian and Schoevers2017); second, exclusive use of non-specialist interviewers potentially reduces diagnostic precision (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Feng, Liu, Wu, Li, Zhang, Yang and Zhang2023; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Li, Chen, Shelley and Tang2023); third, restrictive sampling based on household registration (hukou) fails to capture urban migrant populations (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yan, Ma, Guo, Tang, Rakofsky, Wu, Li, Zhu, Guo, Yang, Li, Cao, Li, Li, Wang and Xu2015); fourth, systematic exclusion of insomnia disorder from diagnostic assessments, despite its inclusion in national health priorities (The Leading Group for Promoting Healthy China Initiative, 2019); finally, since the publication of the Chinese DSM-5, no large-scale national survey has comprehensively assessed mental disorders using these criteria, with the sole exception being a study limited to somatic symptom disorder in general hospital settings (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Wei, Fritzsche, Toussaint, Li, Cao, Zhang, Zhang, Chen, Wu, Ma, Li, Ren, Lu and Leonhart2021). This gap raises concerns about the cultural adaptability of current diagnostic frameworks in China. These limitations highlight the need for more representative and methodologically robust investigations.

The Beijing Government and health-related authorities are paying increased attention to mental health and need to address the gaps regarding the prevalence of mental disorders, identify psychosocial correlates for these disorders, and describe the utilization of health care services by individuals with the disorders. Given this background, the Beijing Municipal Health Commission initiated the Beijing Mental Health Survey (BMHS) project in 2021 to fill the gaps in mental health research specific to Beijing. We investigated six common mental disorders in Beijing adults: depressive disorders, bipolar and related disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, insomnia disorder, and alcohol-related disorders. By utilizing a comprehensive sampling strategy and involving qualified mental health professionals in data collection, the BMHS seeks to provide an accurate and detailed picture of the mental health landscape in Beijing.

This study’s findings are particularly relevant in the context of China’s ongoing mental health initiatives. The results from the BMHS will contribute to the development of more effective mental health policies, interventions, and resource allocation strategies in Beijing and serve as a model for other rapidly growing urban areas in China as well as all over the world.

Methods

Study design and sample

The BMHS was a cross-sectional epidemiological survey. The survey included community residents from mainland China aged 18 years or older who had lived for at least 6 months over the 12 months before the survey at sampled addresses across the 16 districts of Beijing. This survey imposed no restrictions on participants’ household registration places (i.e. hukou). The sampling frame excluded individuals with hearing impairment, those who were pregnant at the time of the survey.

The sample was obtained using a four-stage non-proportional stratified sampling approach. First, the Probability Proportionate to Size Sampling (PPS) method was used to draw 70 subdistricts or towns from all 16 districts of Beijing. Second, three communities or villages were randomly selected from each subdistrict or town, resulting in a total of 210 sampling units. Third, a systematic sampling procedure was used to choose 70–80 households from each community or village. Fourth, the Kish complete random table was used for the random selection of the individual in each household. Supplementary household sampling was performed in target communities using the original systematic method when over 12 originally selected households were missed or rejected, with replacement multiples of 12.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval No.: MR-11-23-010737). All survey procedures complied with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Written informed consent for the collection and use of personal data was obtained from all participants prior to the interview. Participants were also informed of their right to withdraw from this survey at any time without penalty.

Survey measures and data collection

The survey was conducted in one-step procedure and the interviews were carried out by qualified mental health professionals directly. Data collected included the household information questionnaire, the Chinese version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Research Version (SCID-5-RV) (Phillips, Chen, & Cai, Reference Phillips, Chen and Cai2021), and an electronic structured questionnaire (demographic information, help-seeking preferences, and the Depression Knowledge Questionnaire). The authors of SCID-5-RV deliberately conducted jump checks for this investigation due to the selection of different modules. This interview allows for multiple current and lifetime diagnoses, ranked according to their clinical significance. The timeframes used to assess prevalences of current disorders were defined in SCID-5-RV as follows: past 1 month for major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, panic disorder (PD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); past 3 months for insomnia disorder; past 6 months for agoraphobia, social phobia (SOP), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD); past 12 months for alcohol use disorder; and past 2 years for persistent depressive disorder. Lifetime diagnoses were determined based on participants’ experiences over their entire lives before the interview.

Individuals with lifetime diagnoses were asked whether they had sought help and received any treatment for their mental problems following the onset of symptoms. Those who responded affirmatively were further asked to provide details regarding the type of help and treatment received. Help-seeking behaviors were categorized into four categories: (1) the specialty mental health service category, including services provided by any mental health professional, such as psychiatric outpatient departments, inpatient units, and psychotherapy institutions.; (2) the general medical service category, encompassing care from any health professional outside of mental health or psychology departments in general hospitals, as well as practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine or Western medicine; (3) the traditional service category, which included help from Qigong practitioners, folk healers, or religious institutions (e.g. temples); and (4) the informal support category, comprising support from relatives, friends, colleagues, neighbors, and online. Treatment categories were classified into three categories, corresponding to the first three help-seeking categories described above.

A cohort of 113 psychiatrists successfully completed a rigorous standardized training program and subsequently passed a structured simulated-interview examination to ensure diagnostic consistency. A randomly selected subset of 2595 SCID-5-RV assessments (24.1% of the total) was re-administered by a blinded interviewer following the initial evaluation. Among these, 58 (2.8%) were discordant for the primary diagnosis, and 94 (3.6%) showed discrepancies for other diagnoses. The kappa value for any diagnosis was 0.863, indicating good diagnostic consistency. Furthermore, all principal diagnostic categories (depressive, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, insomnia, and alcohol-related disorders) demonstrated substantial reliability, with kappa values greater than 0.75 (Supplementary Table S1). The use of a single-blinded interviewer may limit generalizability; nonetheless, the high kappa value demonstrates general diagnostic reliability. Participants could choose a face-to-face interview or an online video interview in BMHS (Cong, Zhang, Shang, & Wang, Reference Cong, Zhang, Shang and Wang2024). Computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) and paper-and-pencil interviewing (PAPI) were applied in this survey at the same time. Strict data security systems were implemented, and all the project team members’ data security awareness was enhanced to ensure data protection. The audio recordings made by tablet computers during interviews were only used for data quality control and could be accessed on the secure server only by the study supervisors. Data were stored on a secure server accessible only to authorized personnel.

The study implemented a multi-tiered quality control system for on-site supervision. Real-time monitoring was achieved through synchronous data and recording uploads with backend management, enabling immediate feedback and corrective oversight. After rigorous quality checks (including double data entry, data logic checks, audio record checks, and telephone checks), we ensured over 95% of interviews met protocol standards, with only negligible errors remaining.

Statistical analysis

The target sample size was based on reliably estimating the point prevalence of depression, which had a reported prevalence of 3.31% in the 2003 survey in Beijing (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Li, Xiang, Guo, Hou, Cai, Li, Li, Tao, Dang, Wu and Deng2007). Assuming a prevalence (p) of 3.31%, a relative error (ε) of 15%, a design effect (deff) of 2.1, and a non-response rate of 30%, based on the following formula, the required sample size was 10,500 individuals. (Elashoff & Lemeshow, Reference Elashoff, Lemeshow, Ahrens and Pigeot2005)

The final weight for each participant was the result of multiplying the sampling design weight, non-response weight, post-stratification weight, and trimming of weight. The sampling design weight was the product of the sampling weights from the first three steps of sampling. Non-response weight was calculated as the reciprocal of predicted non-response probability, which was derived from a logistic regression model. The post-stratification weighting for BMHS was adjusted for population characteristics based on the 7th census data of Beijing in 2020(Office of the Leading Group of the State Council for the Seventh National Population Census, 2022), which was defined by living area (urban and rural), sex (male and female), and age group (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, ≥70 years). To ensure the validity of the post-stratification adjustments in the BMHS, we conservatively trimmed extreme weight values using 5% and 95% trimming cutoffs.

The lifetime and 1-month prevalence of mental disorders were estimated using both unweighted and weighted data. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Standard errors (SEs) were used to quantify the magnitude of sampling error. Weighted chi-square tests were conducted to evaluate differences in the point prevalence of any of the six studied mental disorders across socio-demographic factors, including gender, age, and place of residence (urban vs. rural). Collected data were used to describe weighted care seeking and treatment of people with lifetime mental disorders. In this study, the urban–rural classification followed the criteria issued by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, which defines urban areas as cities and towns with a high concentration of non-agricultural residents and developed infrastructure, while rural areas comprise villages and townships where agriculture remains prevalent.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of the BMHS sample

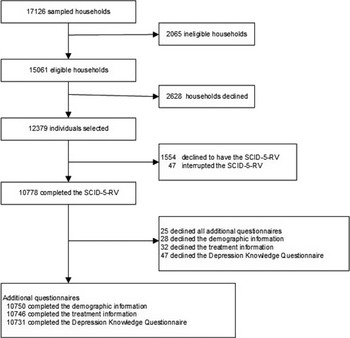

From October 8, 2021, to December 12, 2021, 12,379 individuals from the 15,061 eligible households were interviewed. Among them, 10,778 (87.1%) individuals finished the Diagnostic interview (Figure 1). The implemented field methodology facilitated a relatively high response rate.

Figure 1. Study profile. SCID-5-RV, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Research Version.

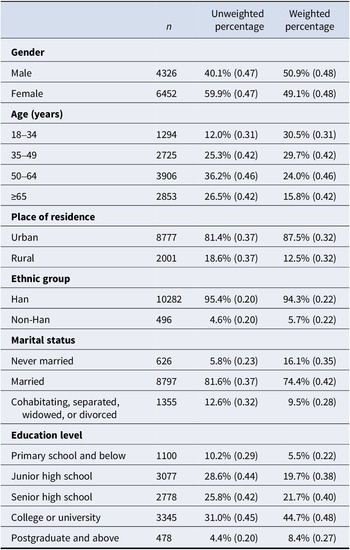

Weighted demographic composition in this study sample was close to the population composition in the 7th census in Beijing, revealing that the study sample in BMHS is of good representability and generalizability to the situation in Beijing. The sample included 49.1% women; 53.1% having a college degree or above, and 87.5% living in urban areas (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the BMHS sample

Note: Data are % (SE) unless otherwise stated. Sample consisted of the entire BMHS sample (n = 10,778). BMHS, Beijing Mental Health Survey.

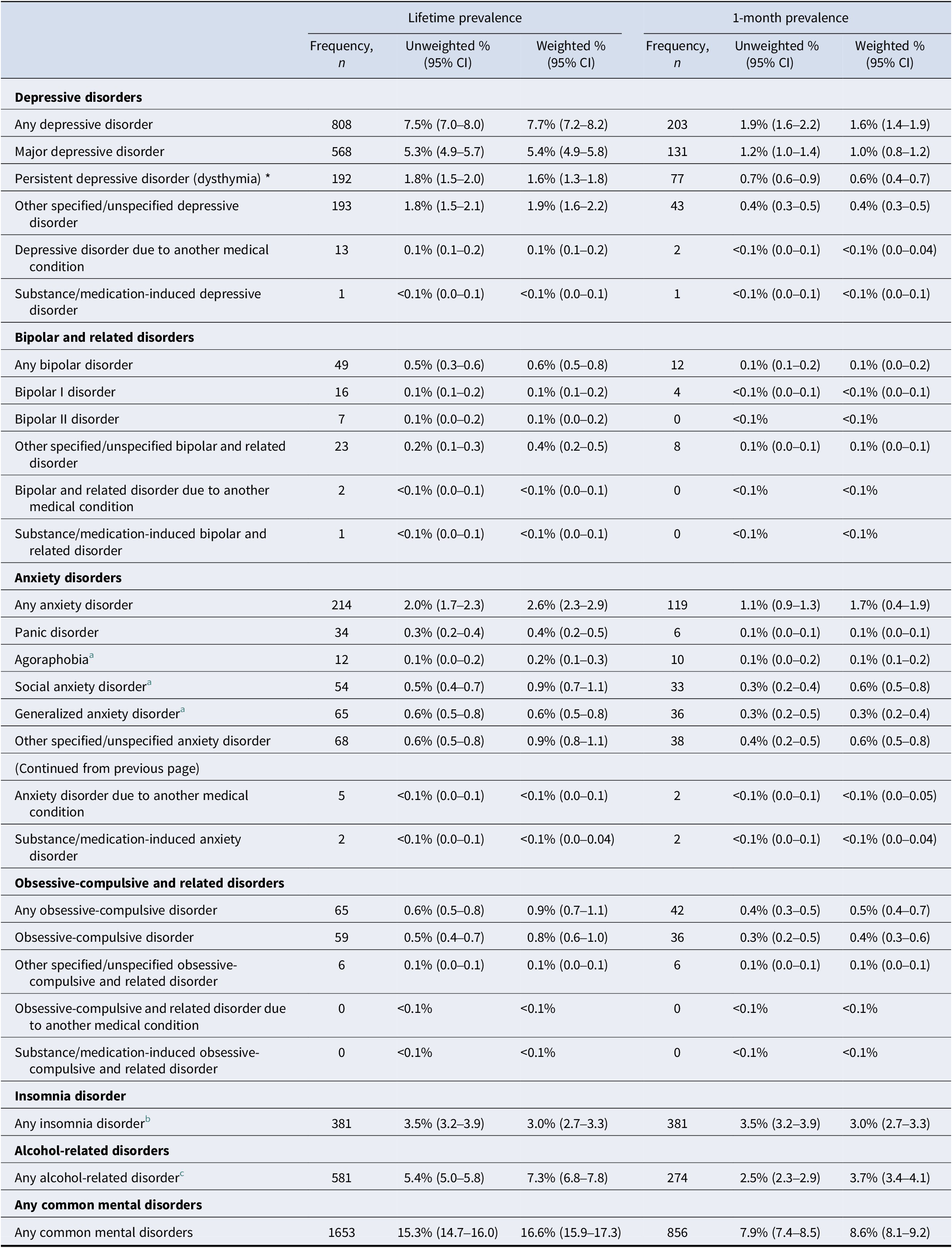

Prevalence of DSM-5 disorders

The weighted lifetime prevalence of any of the six studied mental disorders was 16.6%, indicating that one in six individuals had met diagnostic criteria for at least one mental disorder during their lifetime (Table 2). Depressive disorders and alcohol-related disorders were the most prevalent categories (7.7% and 7.3%, respectively), followed by insomnia disorder (3.0%) and anxiety disorders (2.6%). Bipolar and related disorders demonstrated the lowest weighted lifetime prevalence (0.6%), with obsessive-compulsive and related disorders slightly higher (0.9%). The most prevalent specific disorder was major depressive disorder (5.4%).

Table 2. Unweighted and weighted lifetime and 1-month prevalence of common mental disorders in Beijing

Note: Prevalence 95% CI could not be calculated when the frequency was equal to 0. The point prevalence is used for most diseases to obtain point prevalence estimates unless otherwise stated. *The point prevalence of persistent depressive disorder (Dysthymia) was estimated within 2 years from the date of the survey.

a The point prevalence of Agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorder† were estimated within 6 months from the date of the survey.

b The point prevalence of insomnia disorder was estimated within 3 months from the date of the survey. The lifetime prevalence of insomnia disorders was not investigated.

c The point prevalence of alcohol-related disorder was estimated within 12 months from the date of the survey.

The weighted 1-month prevalence of any of the six studied mental disorders was 8.6%, indicating that over one-twelfth of individuals met diagnostic criteria for at least one current mental disorder at the time of assessment. The most prevalent disorder category was alcohol-related disorder (3.7%), followed by insomnia disorder (3.0%), anxiety disorders (1.7%), and depressive disorders (1.6%). Bipolar and related disorders demonstrated the lowest weighted 1-month prevalence (0.1%), with obsessive-compulsive and related disorders slightly higher (0.5%).

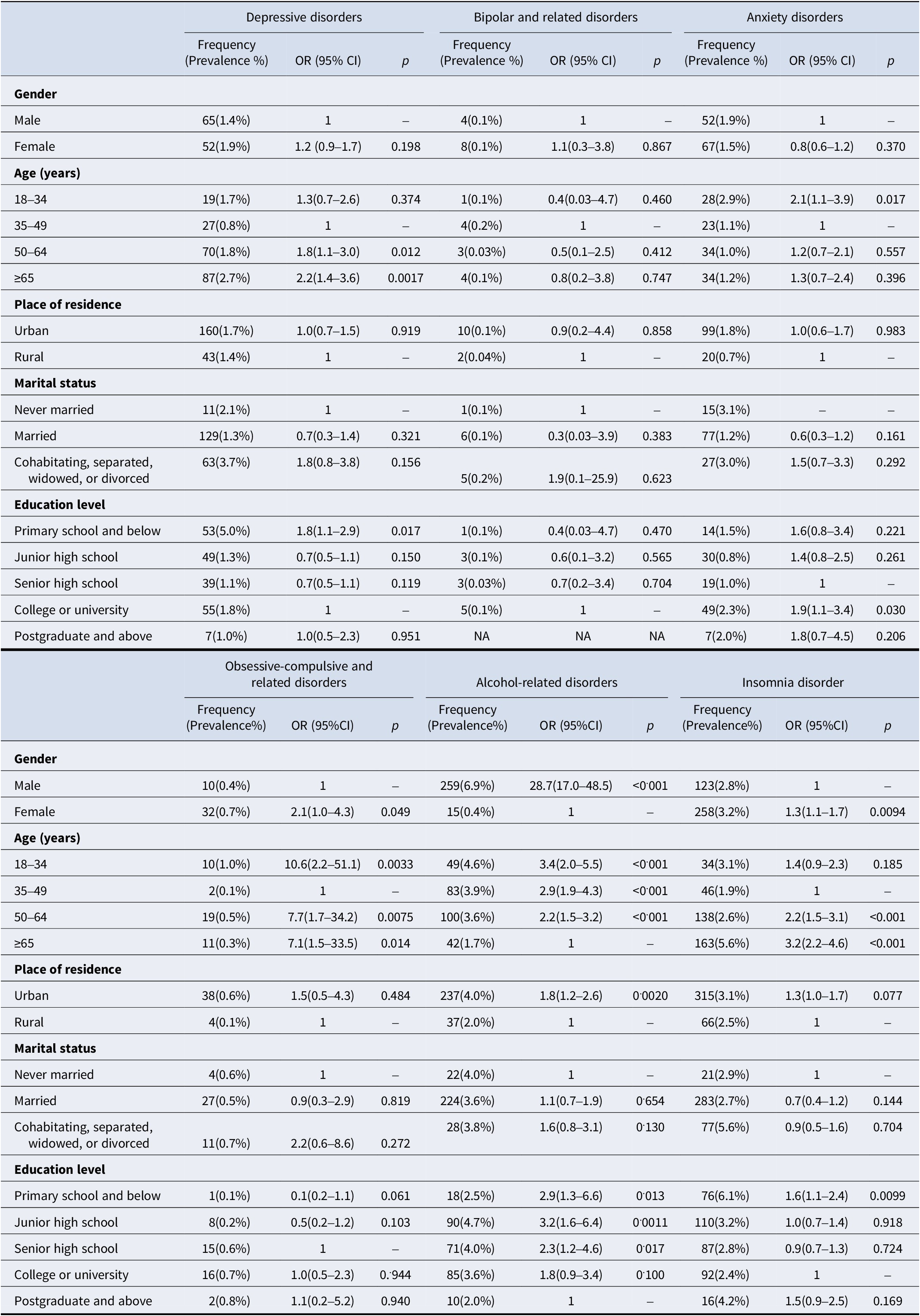

Association between socio-demographic characteristics and 1-month DSM-5 disorders

Women were more likely to have any of the six studied mental disorders than men (Table 3). While the 1-month prevalence of insomnia disorder and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders was higher in women, that of alcohol-related disorders was higher in men.

Table 3. The 1-month prevalence of mental disorders by sociodemographics

Note: Prevalence 95% CI could not be calculated when the frequency was equal to 0. NA, not applicable.

For individuals aged 18–34 years, the 1-month prevalence of anxiety disorders (2.9% vs 1.0–1.2%), obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (1.0% vs 0.1–0.5%), and alcohol-related disorders (4.6% vs 1.7–3.9%) was significantly higher than that in other age groups. Compared with other age groups, individuals aged 35–49 years demonstrated a significantly lower 1-month prevalence. Individuals aged 50–64 years consistently demonstrated the second-highest 1-month prevalence for most mental disorders across all age groups. Individuals aged ≥65 years exhibited significantly higher 1-month prevalence of both depressive disorders (2.7% vs 0.8–1.7%) and insomnia disorder (5.6% vs 1.9–3.1%) compared with younger age groups.

Urban residents exhibited a significantly higher 1-month prevalence of alcohol-related disorders compared to their rural counterparts, whereas no statistically significant urban–rural disparities were observed in the current prevalence rates of other mental health disorders.

No significant differences in the 1-month prevalence of mental disorders were observed across marital status groups in multivariate analysis.

Individuals with a primary school education or below exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of depressive disorders (OR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.1–2.9) and insomnia disorders (OR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.1–2.4) compared to those with a college or bachelor’s degree (reference group). Individuals with a college or bachelor’s degree showed a significantly higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (OR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.1–3.4) compared to those with only a senior high school education (reference group). Alcohol use disorder prevalence showed an inverse educational gradient, with the highest rates among those with junior high school education (OR = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.6–6.4), followed by primary school or below (OR = 2.9, 95% CI: 1.3–6.6) and senior high school education (OR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.2–4.6), using postgraduate education as the reference.

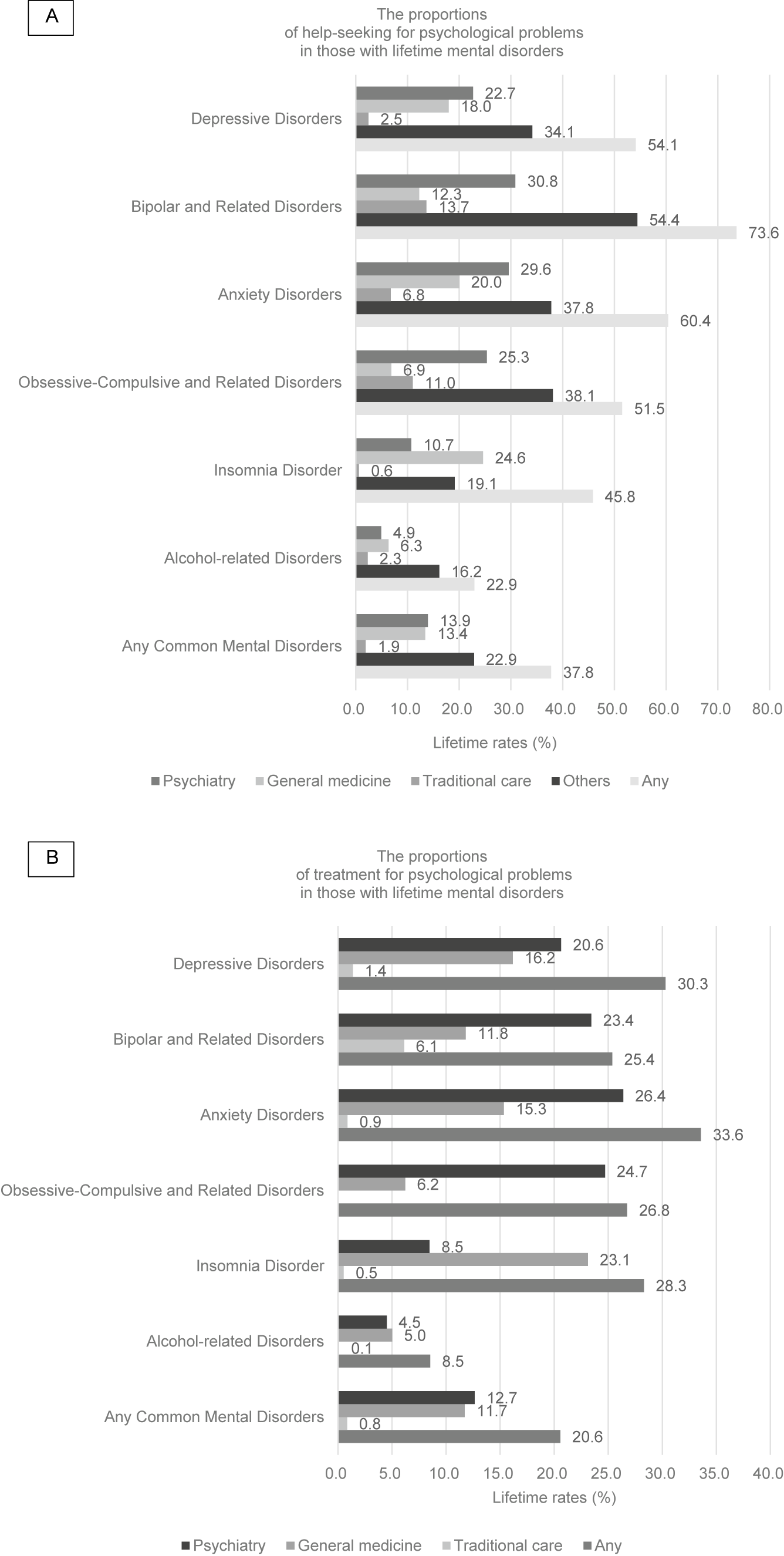

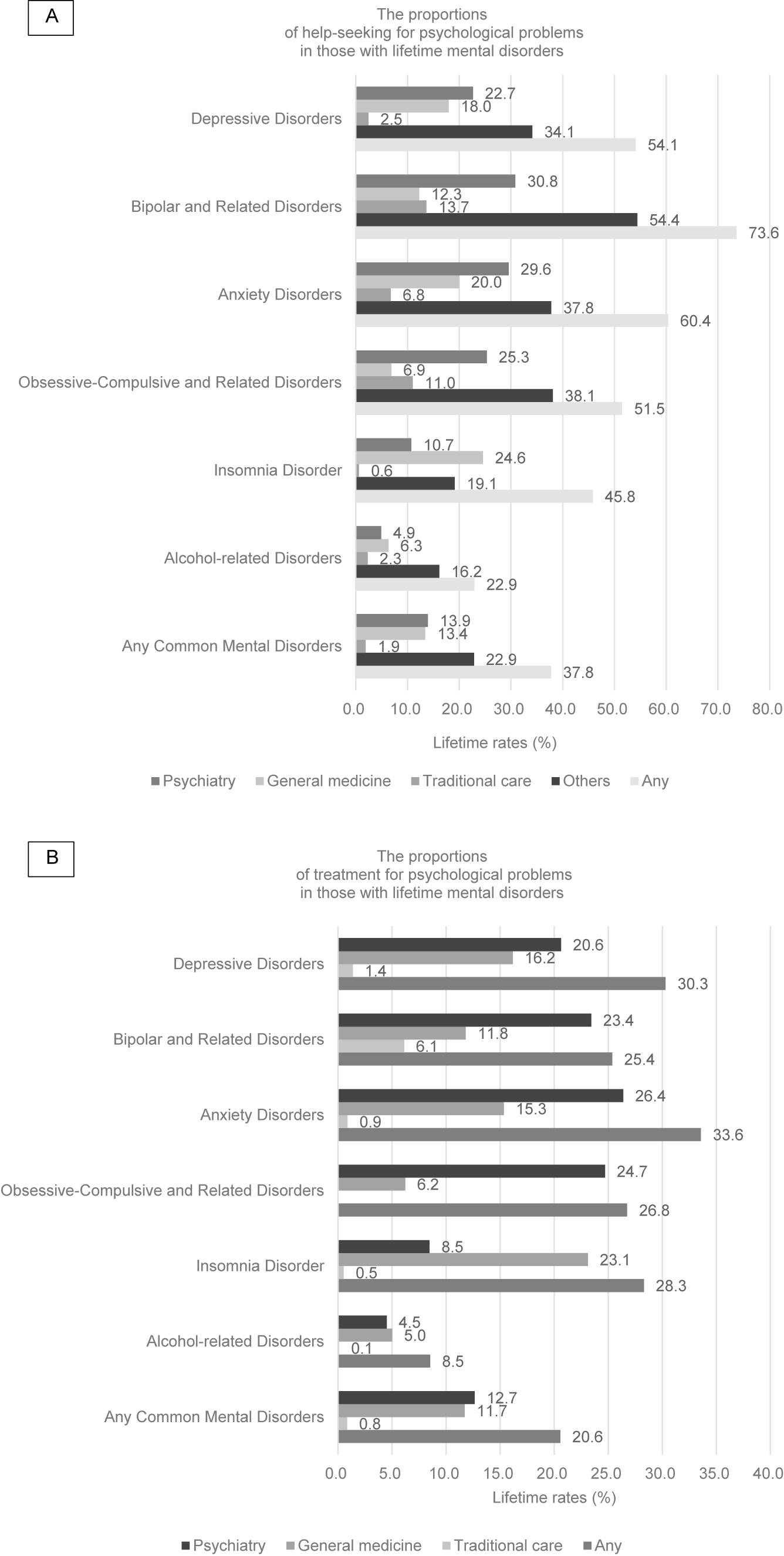

Lifetime help-seeking and treatment

Of the individuals with any of the six studied lifetime mental disorder, exhibited a treatment gap, with over 60% never seeking help and 75% never receiving treatment (Figure 2). Help-seeking patterns revealed a predominant reliance on informal support over professional services among individuals with lifetime mental disorders. Specifically, professional service utilization was low: 13.9% (95% CI: 12.3–15.5%) sought specialty mental health services, and 13.4% (95% CI: 11.9–15.0) sought general medical services. In contrast, informal support was the most frequent help source (22.9%, 95% CI: 20.9–24.8).

Figure 2. The proportions of help-seeking and treatment for psychological problems in those with lifetime mental disorders.

Clinically meaningful variations in help-seeking pathways were evident among different mental health conditions. Individuals with depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorders showed a significantly greater likelihood of utilizing mental health specialty services compared to general medical services. Conversely, those with insomnia disorder and alcohol use disorder were more likely to seek general medical services than specialty mental health services. The treatment utilization priorities for different mental disorders consistently demonstrated this pattern.

Among individuals with lifetime mental disorders, professional treatment utilization was markedly low. Only 12.7% (95% CI: 11.1–14.2%) received specialty mental health treatment, while merely 11.7% (95% CI: 10.2–13.2) received treatment in general medical settings, collectively indicating that <25% obtained professional care. Notably, individuals with alcohol-related disorders demonstrated the lowest rates of help-seeking and utilization of health care services.

Discussion

We present the first large-scale, representative mental health survey from China - a critical low- and middle-income countries (LMCs) context - featuring psychiatrist-administered DSM-5 clinical interviews, providing benchmark prevalence and treatment metrics.

The prevalence of mental disorders in our study was higher than those reported in the three previous large-scale surveys of mental disorders in Beijing (Guo, Zhu, & Huang, Reference Guo, Zhu and Huang1994; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yan, Ma, Guo, Tang, Rakofsky, Wu, Li, Zhu, Guo, Yang, Li, Cao, Li, Li, Wang and Xu2015; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Li, Xiang, Guo, Hou, Cai, Li, Li, Tao, Dang, Wu and Deng2007). The lifetime prevalence of mental disorders obtained in the BMHS was similar to that of the first nationwide survey of mental disorders in China (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu, Yu, Yan, Yu, Kou, Xu, Lu, Wang, He, Xu, He, Li, Guo, Tian, Xu, Xu and Wu2019; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding, Pang, Li, Zhang and Wang2009), but slightly lower than that of the survey in 2009, which used SCID in four city-provinces of China (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding, Pang, Li, Zhang and Wang2009). This was because the BMHS study included insomnia, a common mental disorder, which had not been reported in previous surveys. Based on the analysis of 2021 GBD data (Tian et al., Reference Tian, Yan, Xiong, Zhang, Peng, Zhang, Zhou, Liu, Zhang, Ye, Zhao and Tian2025), the weighted point prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in the Beijing population was lower than that observed in the Chinese population. The prevalence in our study was lower than that observed in Islamic countries during the same period (Khaled et al., Reference Khaled, Alhussaini, Alabdulla, Sampson, Kessler, Woodruff and Al-Thani2024a, Reference Khaled, Al-Thani, Sampson, Kessler, Woodruff and Alabdulla2024b). Comparability between our study results and earlier findings is limited due to differences in diagnostic criteria, instruments, survey methods, investigated disorders, and sampled populations.

The reasons for the different prevalence among surveys may be as follows. First, the sample population had different characteristics. For example, the majority of the survey sample in BMHS was urban population (87.5%), which was different from previous survey groups with a larger proportion of rural population. In the 2009 survey in four city-provinces of China, 71% of the study sample lived in rural areas (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding, Pang, Li, Zhang and Wang2009). Besides, the previous three Beijing surveys in 1991, 2003, and 2010 had restricted household registration to Beijing (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Zhu and Huang1994; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Xiang, Cai, Li, Xiang, Guo, Hou, Li, Li, Tao, Dang, Wu, Deng, Wang, Lai and Ungvari2009; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Ma, Guo, Xu, Wu, Li, Zhu, Guo, Yang, Liu, Li, Cao, Li, Li and Wang2017). Second, methodological factors, such as targeted disorders, diagnostic criteria, instruments, and survey models, resulted in the prevalence differences. Third, the occurrence of most mental disorders is highly related to psychosocial factors, while the past few decades have seen social changes such as rapid economic development, the rising divorce rate, and the high urbanization rate. Finally, with the popularization of public mental health education and the continuous improvement of mental health literacy among community residents, their willingness to report psych-psychological symptoms and self-recognition of mental disorders are constantly improving.

The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders reported in this study was lower than that of the China Mental Health Survey because this survey did not include specific phobia, which accounted for over one-third of the prevalence of anxiety disorders (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu, Yu, Yan, Yu, Kou, Xu, Lu, Wang, He, Xu, He, Li, Guo, Tian, Xu, Xu and Wu2019), while the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder were separated from anxiety disorders in DSM-5 to form independent diagnostic classifications. The lifetime prevalence of the alcohol-related disorder reported in this study was higher than that in the China Mental Health Survey because there was no strict limit on the specific amount of alcohol consumed in the SCID-5-RV, while some of the symptoms that meet the diagnostic criteria are common in Chinese alcohol culture especially in social drinking.

The sociodemographic factors associated with mental disorders identified in this study are consistent with those of previous epidemiological studies (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Xu, Huang, Li, Ma, Xu, Yin, Xu, Ma, Wang, Huang, Yan, Wang, Xiao, Zhou, Li, Zhang, Chen, Zhang and Zhang2021; Yin et al., Reference Yin, Xu, Tian, Yang, Wardenaar and Schoevers2018; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Rao, Cui, Li, Li, Ng, Ungvari, Li and Xiang2019). Previous studies have indicated a higher 12-month prevalence of depressive disorders among divorced individuals compared to those who are married (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Xu, Huang, Li, Ma, Xu, Yin, Xu, Ma, Wang, Huang, Yan, Wang, Xiao, Zhou, Li, Zhang, Chen, Zhang and Zhang2021). In contrast, the present study did not detect a statistically significant difference in the 1-month prevalence of depressive disorders across marital status groups. This discrepancy may be attributable to the differing assessment periods (12 months vs. 1 month). In particular, within the Chinese context, divorce constitutes a significant life decision, often involving prolonged deliberation. Formal divorce is not granted until 30 days after the initial application is submitted to the marriage registration authority. Consequently, the use of a standard internationally recognized diagnostic tool with a restricted time frame in this study may have been inadequate to capture the full extent of divorce’s impact on mental health. Further targeted research is warranted to explore this relationship more comprehensively. Enhance interventions for key groups by developing targeted strategies. Special attention should be given to addressing insomnia disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and depression within the female population. For the elderly, focus on combating depression and alleviating feelings of loneliness. Additionally, prioritize the mental health challenges faced by residents in rural areas.

The results suggest that while help-seeking rates and treatment rates for mental disorders are higher in Beijing than nationally (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Xu, Huang, Li, Ma, Xu, Yin, Xu, Ma, Wang, Huang, Yan, Wang, Xiao, Zhou, Li, Zhang, Chen, Zhang and Zhang2021), they remain substantially lower than those in developed countries like the United States and those in Europe (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer, Borges, Bromet, Bruffaerts, Girolamo, Graaf, Gureje, Haro, Karam, Kessler, Kovess, Lane, Lee, Levinson, Ono, Petukhova and Wells2007).(McHugh et al., Reference McHugh, Whitton, Peckham, Welge and Otto2013; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Zhou, Li, Wang, Yang, Gong, Xu, Zhang, Yang, Bueber, Phillips and Zhou2024) This may be attributed to community residents’ inadequate awareness of mental health symptoms, leading them to dismiss the necessity of diagnosis and treatment(Rajan et al., Reference Rajan, Behera, Patra, Singh and Patro2024; Werlen, Puhan, Landolt, & Mohler-Kuo, Reference Werlen, Puhan, Landolt and Mohler-Kuo2020). Additionally, stigma surrounding mental health could deter individuals from seeking professional help (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Shang, Yan, Zhao, Qi, Huang, Li, Sun, Han, Zhang, Li, Ma, Tian, Zhou, Zhang and Wang2024). Although the number of mental health professionals has increased compared to previous years, a shortage persists in rural areas (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Zhou, Li, Wang, Yang, Gong, Xu, Zhang, Yang, Bueber, Phillips and Zhou2024). Digital health interventions have the potential to improve the efficacy and accessibility of mental health services for people with mental health problems (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Eisner, Nicholas, Wilson and Bucci2025; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Fang, Jiao, Xiang, Ma, Zhang, Liu, He, Li, He and Lei2025; Merchant, Torous, Rodriguez-Villa, & Naslund, Reference Merchant, Torous, Rodriguez-Villa and Naslund2020; Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, Granell, Díaz-Sanahuja, Van Woensel, Bretón-López, Mira, Castilla and Casteleyn2020). The COVID-19 pandemic may have exerted opposing influences on both the incidence and treatment of mental disorders, potentially contributing to the observed gap between prevalence and treatment rates (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhang, Li, Chen and Wang2023). Chinese and Western medicine providers were combined into a single category for analysis due to the research instrument’s lack of interdisciplinary specialties, which prevented a clear distinction, and the desire to align with previous major Chinese epidemiological surveys for better comparability (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Xu, Huang, Li, Ma, Xu, Yin, Xu, Ma, Wang, Huang, Yan, Wang, Xiao, Zhou, Li, Zhang, Chen, Zhang and Zhang2021; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding, Pang, Li, Zhang and Wang2009; Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Ma, Huang, Zhang, Hou, Tai, Yan, Yu, Xu, Wang, Xu, Li, Xu, Xu, Wang, Yan, Xiao, Li, Liu and Zhou2025).

There are several structural and cultural barriers that contribute to the observed mismatch between increased access and stable prevalence. First, existing evidence indicates that public mental health literacy—particularly knowledge and beliefs regarding treatments—remains limited. Notably, lower mental health literacy is positively associated with a higher incidence of mental disorders, underscoring its potential as a strategic target for promoting psychological well-being throughout the lifespan (Cong et al., Reference Cong, Shang, Yan, Zhao, Qi, Huang, Li, Sun, Han, Zhang, Li, Ma, Tian, Zhou, Zhang and Wang2024; Li & Reavley, Reference Li and Reavley2020; Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Wang, Ding, Tan and Zhou2024). Second, despite patients’ preference for psychological treatment over pharmacotherapy (McHugh et al., Reference McHugh, Whitton, Peckham, Welge and Otto2013), China—including urban centers such as Beijing—continues to experience a shortage of adequately trained mental health professionals capable of delivering psychotherapy or counseling (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Zhou, Li, Wang, Yang, Gong, Xu, Zhang, Yang, Bueber, Phillips and Zhou2024). Third, treatment non-adherence was prevalent among patients with mental disorders, primarily due to lack of insight, inadequate family support, long treatment duration, medication side effects, financial constraints, and perceived illness stigma (Chai, Liu, Mao, & Li, Reference Chai, Liu, Mao and Li2021). Finally, the establishment of mental health treatment control and promotion centers, both in Beijing and nationwide, reflects ongoing efforts to standardize and improve the quality of mental health services. These initiatives are expected to improve both the utilization of professional treatment and the implementation of evidence-based interventions, thereby enhancing recovery among patients with mental disorders and reducing the overall prevalence of these conditions in the population.

Limitations

Recognizing the limitations of this survey is important when interpreting the findings. First, no causal inference could be obtained, and recall bias might be inevitable due to the nature of cross-sectional epidemiological surveys and psychiatric interviews. Second, the scope of this survey does not include certain mental disorders of research interest due to common practical constraints such as budgetary limitations, timeline restrictions, and available personnel, as well as considerations related to respondents’ acceptance of interview content and duration. Strategic prioritization of addressing missing data further influenced the selection of conditions included. The specific individualized reasons for the exclusion of certain diseases are as follows: The estimates for nicotine use disorder comprised a majority of regular daily smokers (Volkow & Blanco, Reference Volkow and Blanco2023). More than half of Chinese men older than 18 years were smokers (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yang, Wang, Jiang, Huang, Zhao, Zhang, Li, Liu, Li, Wang, Wu, Li, Chen and Zhou2022), prompting the national healthcare system to maintain a dedicated tobacco control department that conducts regular surveys and implements evidence-based interventions. Additionally, to enhance comparability with previous large-scale epidemiological surveys in China (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu, Yu, Yan, Yu, Kou, Xu, Lu, Wang, He, Xu, He, Li, Guo, Tian, Xu, Xu and Wu2019; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding, Pang, Li, Zhang and Wang2009), the assessment of nicotine use disorders—which were not covered in those earlier studies—was likewise excluded from the present study. The schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders were not included in this survey, as prior epidemiological evidence indicates that their prevalence remains relatively stable over time (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu, Yu, Yan, Yu, Kou, Xu, Lu, Wang, He, Xu, He, Li, Guo, Tian, Xu, Xu and Wu2019) and that the majority of affected individuals are already enrolled in the basic public health service registry. PTSD was excluded from this survey due to its low population prevalence (less than 0.2% in China), which would require a sample size more than 10 times larger to achieve statistically representative estimates. Third, this study does not explore the influence of key sociocultural factors, such as socioeconomic status and migration, on mental disorders, which may limit a comprehensive understanding of their etiological roles. Finally, it is possible that those patients with severe mental disorders might have been more reluctant to participate than healthy residents, leading to an underestimation of the actual prevalence.

Conclusions

Depressive disorders and alcohol-related disorders remained the most common mental disorders among Beijing residents. However, the newly estimated prevalence of insomnia disorder also warrants greater attention. These findings suggest that government agencies should not only intensify efforts to improve public awareness but also develop comprehensive health promotion strategies to prevent their onset. Although mental healthcare resources in cities such as Beijing were relatively abundant compared to other Chinese cities or most urban centers in developing countries, rates of professional help-seeking and treatment uptake for mental disorders remain significantly low. This suggests that other municipalities should urgently address mental health service utilization within their regions to prevent more severe adverse outcomes resulting from widespread untreated conditions. The findings of the BMHS and interpretation of the results will contribute substantially to the understanding of mental health situations in major cities of the developing countries, provide valuable information for future mental health policy making, and rational allocation of health resources. The observed dissociation between treatment access expansion and epidemiological prevalence reduction suggests systemic barriers, including low professional treatment engagement and insufficient dissemination of evidence-based interventions. This necessitates multi-sectoral, policy-driven strategies combining population health initiatives with strengthened mental healthcare systems.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725102456.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Phillips and his colleagues from Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine, Shanghai (China), for providing the Chinese version of SCID-5-RV; Hanhui Chen from Mental Health Center of Tianjin Medical University and Zhiqing Wang from Guang’anmen Hospital for interviewer training.

Funding statement

The study was funded by the Sci-Tech Innovation 2030 - Major Project of Brain Science and Brain-inspired Intelligence Technology (grant No. 2021ZD0200600), Beijing Key Diseases Flow Control and Prevention grant (grant No. ZX035) and Prevention and Control of Major Infectious Diseases grant (grant No. XM202111).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.