1 Introduction

An active area of research focuses on identifying minimal size conditions on a set that ensure it contains a similar copy of a given finite point configuration. Size may refer to positive upper density, positive Lebesgue measure, sufficient Hausdorff dimension, or to some other notion of magnitude. Finite point configurations include arithmetic progressions, simplexes, chains, trees, and more general graphs.

In this article, we focus on the occurrence of arithmetic progressions and triangles in compact subsets of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

for

$\mathbb {R}^d$

for

![]() $d\geq 1$

. We say that a point configuration

$d\geq 1$

. We say that a point configuration

![]() $P=(v^i)_{i=1}^k$

is realized in a set A if A contains a similar copy of P. Further, we say that P is stably realized in A if the set of t for which A contains a rotated and translated copy of

$P=(v^i)_{i=1}^k$

is realized in a set A if A contains a similar copy of P. Further, we say that P is stably realized in A if the set of t for which A contains a rotated and translated copy of

![]() $tP$

has nonempty interior.

$tP$

has nonempty interior.

Arithmetic progressions have been investigated in a variety of context. Szemerédi [Reference Szemerédi37] famously showed that any subset of the natural numbers with positive upper density contains arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions. A higher-dimensional variant was first obtained by Furstenberg and Katznelson [Reference Furstenberg and Katznelson12]; see also [Reference Bourgain6, Reference Lyall and Magyar25, Reference Ziegler43] for further developments.

In another direction, it is a consequence of the Lebesgue density theorem that any finite point configuration is stably realized in any subset of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

of positive Lebesgue measure. In particular, arithmetic progressions of arbitrary finite length are stably realized in sets of positive measure. One must exercise some caution though. Bourgain [Reference Bourgain6] showed that any subset of

$\mathbb {R}^d$

of positive Lebesgue measure. In particular, arithmetic progressions of arbitrary finite length are stably realized in sets of positive measure. One must exercise some caution though. Bourgain [Reference Bourgain6] showed that any subset of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^3$

with positive upper density contains the vertices of an equilateral triangle, as well as all sufficiently large scalings. This result, however, does apply to sufficiently large scalings of arithmetic progressions (see a counter example in [Reference Bourgain6, Example b]).

$\mathbb {R}^3$

with positive upper density contains the vertices of an equilateral triangle, as well as all sufficiently large scalings. This result, however, does apply to sufficiently large scalings of arithmetic progressions (see a counter example in [Reference Bourgain6, Example b]).

A topological variant, provided by the second listed author and Mcdonald [Reference McDonald and Taylor30], states that if B is a second category Baire space in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

(or in any topological vector space V), and

$\mathbb {R}^d$

(or in any topological vector space V), and

![]() $P \subset V$

is a countable bounded sequence, then P is stably realized in B. In particular, B contains arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions and all sufficiently small scalings.

$P \subset V$

is a countable bounded sequence, then P is stably realized in B. In particular, B contains arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions and all sufficiently small scalings.

A finer notion of size, Hausdorff dimension, is central in harmonic analysis and geometric measure theory. The celebrated Falconer distance problems ask how large the Hausdorff dimension of a compact set

![]() $E\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

,

$E\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

,

![]() $d\geq 2$

, needs to be to guarantee that its distance set

$d\geq 2$

, needs to be to guarantee that its distance set

has positive Lebesgue measure. Falconer demonstrated that

![]() $\dim _{\mathrm {H}}(E)>\frac {d}{2}$

is necessary and

$\dim _{\mathrm {H}}(E)>\frac {d}{2}$

is necessary and

![]() $\dim _{\mathrm { H}}(E)>\frac {d+1}{2}$

suffices [Reference Falconer9]; for more recent developments, see the introduction and references in [Reference Borges, Foster, Ou and Palsson5]. Resolving this gap – namely, establishing that the threshold

$\dim _{\mathrm { H}}(E)>\frac {d+1}{2}$

suffices [Reference Falconer9]; for more recent developments, see the introduction and references in [Reference Borges, Foster, Ou and Palsson5]. Resolving this gap – namely, establishing that the threshold

![]() $\frac {d}{2}$

suffices in Falconer’s conjecture – is a major open problem in harmonic analysis and geometric measure theory.

$\frac {d}{2}$

suffices in Falconer’s conjecture – is a major open problem in harmonic analysis and geometric measure theory.

Hausdorff dimension has further been used by a number of authors in analyzing the occurrence and abundance of finite point configurations. This includes, for instance, results on the interior of distance sets associated to chains [Reference Bennett, Iosevich and Taylor2], trees [Reference Borges, Foster, Ou and Palsson5, Reference Greenleaf, Iosevich and Taylor17, Reference Iosevich and Taylor19], necklaces [Reference Greenleaf, Iosevich and Pramanik15], and triangles [Reference Greenleaf, Iosevich and Taylor16, Reference Palsson and Acosta34]; results on the Lebesgue measure of distance sets associated to chains [Reference Ou and Taylor32] and triangles [Reference Greenleaf and Iosevich14]; conditions for the occurrence of equilateral triangles in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^3$

[Reference Iosevich and Magyar20] and the occurrence of arithmetic progressions (with additional assumptions involving Fourier dimension and supported measures) [Reference Chan, Łaba and Pramanik8].

$\mathbb {R}^3$

[Reference Iosevich and Magyar20] and the occurrence of arithmetic progressions (with additional assumptions involving Fourier dimension and supported measures) [Reference Chan, Łaba and Pramanik8].

Hausdorff dimension alone, however, is not enough to guarantee the existence of arithmetic progressions in subsets of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

. Keleti [Reference Keleti23] showed that given any distinct set

$\mathbb {R}^d$

. Keleti [Reference Keleti23] showed that given any distinct set

![]() $\{x,y,z\}\subset \mathbb {R}$

there exists a compact set in

$\{x,y,z\}\subset \mathbb {R}$

there exists a compact set in

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

of Hausdorff dimension

$\mathbb {R}$

of Hausdorff dimension

![]() $1$

which does not contain any similar copy of

$1$

which does not contain any similar copy of

![]() $\{x,y,z\}$

. Máthé demonstrated that full Hausdorff dimension is not enough in any dimension to guarantee the occurrence of

$\{x,y,z\}$

. Máthé demonstrated that full Hausdorff dimension is not enough in any dimension to guarantee the occurrence of

![]() $3$

-point arithmetic progressions (this follows from considering the zeros of the polynomial

$3$

-point arithmetic progressions (this follows from considering the zeros of the polynomial

![]() $P(x_1,x_2,x_3)= x_1-2x_2+x_3$

in Theorem 2.3 of [Reference Máthé27]). Hence, even if a set has full Hausdorff dimension, it may not contain a

$P(x_1,x_2,x_3)= x_1-2x_2+x_3$

in Theorem 2.3 of [Reference Máthé27]). Hence, even if a set has full Hausdorff dimension, it may not contain a

![]() $3$

-term arithmetic progressions.

$3$

-term arithmetic progressions.

Another important 3-point configuration is a triangle. Depending on the ambient dimension, Hausdorff dimension is sometimes enough to guarantee the realization of similar triangles. Given any

![]() $3$

-point set, constructions due to Falconer [Reference Falconer10] and Maga [Reference Maga26] show that there exists a set of full Hausdorff dimension in the plane that does not contain any similar copy. The situation is better, however, for triangles in Legesbue null sets in dimension three. Iosevich and Magyar [Reference Iosevich and Magyar20] prove that there exists a dimensional threshold

$3$

-point set, constructions due to Falconer [Reference Falconer10] and Maga [Reference Maga26] show that there exists a set of full Hausdorff dimension in the plane that does not contain any similar copy. The situation is better, however, for triangles in Legesbue null sets in dimension three. Iosevich and Magyar [Reference Iosevich and Magyar20] prove that there exists a dimensional threshold

![]() $s< 3$

so that if

$s< 3$

so that if

![]() $E\subset \mathbb {R}^3$

with

$E\subset \mathbb {R}^3$

with

![]() $\dim _H(E)>s$

, then E contains the vertices of a simplex V for any non-degenerate

$\dim _H(E)>s$

, then E contains the vertices of a simplex V for any non-degenerate

![]() $3$

-simplex V satisfying a volume condition. They also prove a more general result for k-simplices. Note the non-degeneracy assumption precludes arithmetic progressions.

$3$

-simplex V satisfying a volume condition. They also prove a more general result for k-simplices. Note the non-degeneracy assumption precludes arithmetic progressions.

One might hope that Hausdorff dimension combined with some other conditions on structure or size may be enough to guarantee the occurrence of arithmetic progressions. Łaba and Pramanik [Reference Łaba and Pramanik24] provide sufficient conditions based on Fourier decay and power mass decay for a closed set

![]() $E\subset \mathbb {R}$

to contain a nontrivial

$E\subset \mathbb {R}$

to contain a nontrivial

![]() $3$

-term arithmetic progression; see also [Reference Chan, Łaba and Pramanik8] for a generalization to higher dimensions and more general patterns. However, even sets in

$3$

-term arithmetic progression; see also [Reference Chan, Łaba and Pramanik8] for a generalization to higher dimensions and more general patterns. However, even sets in

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

with both maximal Fourier and Hausdorff dimension need not contain

$\mathbb {R}$

with both maximal Fourier and Hausdorff dimension need not contain

![]() $3$

-APs. Shmerkin [Reference Shmerkin35] demonstrated the dependence of the results in [Reference Łaba and Pramanik24] on the choice of constants by constructing Salem sets (sets of full Fourier dimension) that contain no arithmetic progressions.

$3$

-APs. Shmerkin [Reference Shmerkin35] demonstrated the dependence of the results in [Reference Łaba and Pramanik24] on the choice of constants by constructing Salem sets (sets of full Fourier dimension) that contain no arithmetic progressions.

The results of this section inform us that an alternative notion of size other than Hausdorff dimension is required to guarantee the existence arithmetic progressions in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

, as well as triangles in the plane.

$\mathbb {R}^d$

, as well as triangles in the plane.

In contrast, the results of the current paper are exciting in that they provide new insights for

![]() $3$

-point configurations, including arithmetic progressions, in subsets of the plane (see Section 2). With this, we turn to Newhouse thickness.

$3$

-point configurations, including arithmetic progressions, in subsets of the plane (see Section 2). With this, we turn to Newhouse thickness.

1.1 Newhouse thickness

In the 1970s, Newhouse introduced a notion of size known as thickness for compact subsets of the real line. His clever Gap Lemma gives conditions based on thickness that guarantee that a pair of compact sets intersect. Newhouse’s original motivation was the study of bifurcation theory in dynamical systems [Reference Newhouse31]. Since then, thickness has been used extensively in the fields of dynamical systems and fractal geometry, and even in numerical problem solving [Reference Astels1, Reference Boone and Palsson4, Reference Hunt, Kan and Yorke18, Reference Jung and Lai21, Reference McDonald and Taylor29, Reference Simon and Taylor36, Reference Yavicoli38, Reference Yavicoli and Yu41, Reference Yu42], and higher-dimensional notions of thickness have been introduced [Reference Biebler3, Reference Falconer and Yavicoli11, Reference Yavicoli40].

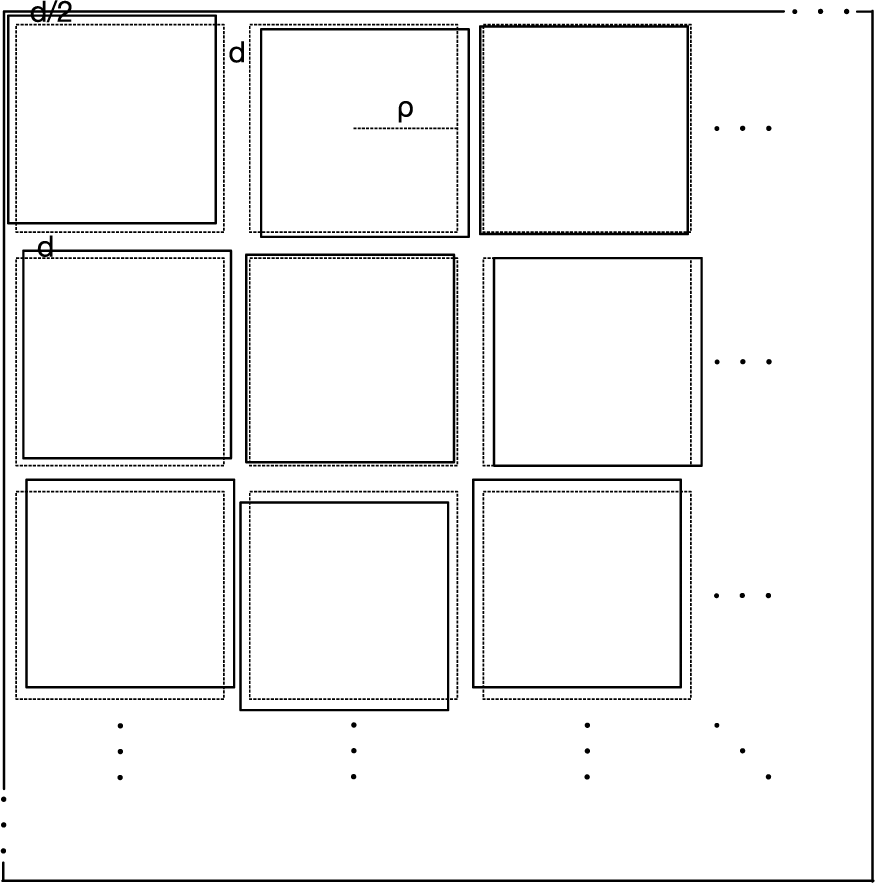

Newhouse thickness is a natural notion of size for compact sets. The complement of every compact set C in

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

is a countable union of open intervals. Discarding the two unbounded open intervals, we are left with a countable union of bounded, open intervals which we call gaps

$\mathbb {R}$

is a countable union of open intervals. Discarding the two unbounded open intervals, we are left with a countable union of bounded, open intervals which we call gaps

![]() $(G_n)$

. Without loss of generality, order the gaps by nonincreasing size. We can then construct C by removing, in order, the gaps

$(G_n)$

. Without loss of generality, order the gaps by nonincreasing size. We can then construct C by removing, in order, the gaps

![]() $(G_n)$

from the convex hull of C, denoted by

$(G_n)$

from the convex hull of C, denoted by

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {conv}}(C)$

. Observe that every time a gap

$\operatorname {\mathrm {conv}}(C)$

. Observe that every time a gap

![]() $G_n$

is removed, two intervals, one to the left of the gap,

$G_n$

is removed, two intervals, one to the left of the gap,

![]() $L_n$

, and one to the right of the gap,

$L_n$

, and one to the right of the gap,

![]() $R_n$

(we call these bridges). Newhouse thickness is computed by considering the ratios of the lengths of the bridges to the lengths of the gaps [Reference Newhouse31, Reference Yavicoli38].

$R_n$

(we call these bridges). Newhouse thickness is computed by considering the ratios of the lengths of the bridges to the lengths of the gaps [Reference Newhouse31, Reference Yavicoli38].

Definition 1.1 Let

![]() $C\subset \mathbb {R}$

be a compact set with convex hull I, and let

$C\subset \mathbb {R}$

be a compact set with convex hull I, and let

![]() $(G_n)$

be the open intervals making up

$(G_n)$

be the open intervals making up

![]() $I\setminus C$

, ordered in decreasing length. Each gap

$I\setminus C$

, ordered in decreasing length. Each gap

![]() $G_n$

is removed from a closed interval

$G_n$

is removed from a closed interval

![]() $I_n$

, leaving behind two closed intervals

$I_n$

, leaving behind two closed intervals

![]() $L_n$

and

$L_n$

and

![]() $R_n$

; the left and right pieces of

$R_n$

; the left and right pieces of

![]() $I_n\setminus G_n$

. The Newhouse thickness of C is defined by

$I_n\setminus G_n$

. The Newhouse thickness of C is defined by

$$ \begin{align*} \tau\left( C\right):= \inf_{n\in\mathbb{N}} \frac{\min\left\{|L_n|,|R_n|\right\}}{|G_n|}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \tau\left( C\right):= \inf_{n\in\mathbb{N}} \frac{\min\left\{|L_n|,|R_n|\right\}}{|G_n|}. \end{align*} $$

Example (A classic set with thickness 1) The middle-third Cantor set has thickness equal to

![]() $1$

. This set is constructed by removing the middle-third of the interval

$1$

. This set is constructed by removing the middle-third of the interval

![]() $|G_n|=\frac {1}{3^n}$

. At each stage, this process leaves left and right intervals of length

$|G_n|=\frac {1}{3^n}$

. At each stage, this process leaves left and right intervals of length

![]() $|L_n|=|R_n|=\frac {1}{3^n}$

.

$|L_n|=|R_n|=\frac {1}{3^n}$

.

The key fact on which the results of this article are based is that sets of sufficient Newhouse thickness contain arithmetic progressions. The following is from [Reference Yavicoli39, Proposition 20].

Proposition 1.1 (Yavicoli [Reference Yavicoli39])

Let

![]() $C\subset \mathbb {R}$

be a compact set with

$C\subset \mathbb {R}$

be a compact set with

![]() $\tau (C)\geq 1$

. Then, C contains an arithmetic progression of length

$\tau (C)\geq 1$

. Then, C contains an arithmetic progression of length

![]() $3$

.

$3$

.

This result says that compact subsets of the real line with thickness at least 1 contain a

![]() $3$

-point arithmetic progression. Note that larger thickness is required for longer progressions (see Remarks 2.6 and 2.7).

$3$

-point arithmetic progression. Note that larger thickness is required for longer progressions (see Remarks 2.6 and 2.7).

We generalize Proposition 1.1 and provide an analog in higher dimensions. The main results of this article are as follows; we:

-

(1) prove a more general version of Proposition 1.1 for convex combinations in

$\mathbb {R}$

(Proposition 2.1);

$\mathbb {R}$

(Proposition 2.1); -

(2) apply this to obtain similar copies of any triangle in Cartesian products in

$\mathbb {R}^2$

(Theorem 2.2);

$\mathbb {R}^2$

(Theorem 2.2); -

(3) prove a higher-dimensional analog that demonstrates the occurrence of arithmetic progressions and convex combinations in compact subsets of

$\mathbb {R}^d$

(Theorem 2.8);

$\mathbb {R}^d$

(Theorem 2.8); -

(4) obtain similar copies of any triangle in general compact sets in

$\mathbb {R}^d$

(Theorem 2.12).

$\mathbb {R}^d$

(Theorem 2.12).

1.2 The Gap Lemma

The main tool used to prove Proposition 1.1 is the Gap Lemma, which gives criteria for the intersection of two compact sets. Note that (ii) implies (i), but we list (i) for emphasis.

Lemma 1.2 (Newhouse’s Gap Lemma [Reference Newhouse31])

Let

![]() $C^1$

and

$C^1$

and

![]() $C^2$

be two compact sets in the real line such that:

$C^2$

be two compact sets in the real line such that:

-

(1)

$\operatorname {\mathrm {conv}}(C^1)\cap \operatorname {\mathrm {conv}}(C^2)\neq \emptyset $

;

$\operatorname {\mathrm {conv}}(C^1)\cap \operatorname {\mathrm {conv}}(C^2)\neq \emptyset $

; -

(2) neither set lies in a gap of the other set;

-

(3)

$\tau (C^1)\tau (C^2)\geq 1$

.

$\tau (C^1)\tau (C^2)\geq 1$

.

Then,

The Gap Lemma is useful in the study of patterns as patterns and intersections are directly connected. A set

![]() $E\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

contains a homothetic copy of a

$E\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

contains a homothetic copy of a

![]() $P=\{v^i\}_{i=1}^k$

if and only if there exists

$P=\{v^i\}_{i=1}^k$

if and only if there exists

![]() $t\neq 0$

so that

$t\neq 0$

so that

$$ \begin{align*}\bigcap_{i=1}^k \left( E- tv^i\right) \neq \emptyset.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\bigcap_{i=1}^k \left( E- tv^i\right) \neq \emptyset.\end{align*} $$

The Gap Lemma has played a role in the investigation of finite point configurations in a number of prior works. Simon and Taylor [Reference Simon and Taylor36] considered Cantor sets

![]() $K_1,K_2\subset \mathbb {R}$

satisfying

$K_1,K_2\subset \mathbb {R}$

satisfying

![]() $\tau (K_1)\cdot \tau (K_2)>1$

, and showed that for any

$\tau (K_1)\cdot \tau (K_2)>1$

, and showed that for any

![]() $x\in \mathbb {R}^2$

, the pinned distance set

$x\in \mathbb {R}^2$

, the pinned distance set

has non-empty interior. This work was later extended by McDonald and Taylor in [Reference McDonald and Taylor28] where they proved that the distance set of a tree T of

![]() $K_1\times K_2$

, defined by

$K_1\times K_2$

, defined by

has non-empty interior, where a tree is a finite acyclic graph. They continued this work in [Reference McDonald and Taylor29], where infinite trees and constant gap trees were investigated.

Progress has been made toward developing and applying higher-dimensional gap lemmas. Boone and Palsson [Reference Boone and Palsson4] obtain higher-dimensional chain results for thick set using a higher-dimensional notion of thickness introduced by Falconer and Yavicoli. Jung and Taylor [Reference Jung and Taylor22] investigate chains and trees using the containment lemma (which serves as a substitute to the gap lemma) and the distance set results introduced in [Reference Jung and Lai21].

Yavicoli proved that compact sets in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

generated by a restricted system of balls with significantly large thickness contain homothetic copies of finite sets [Reference Yavicoli40]. The current article offers an improvement to Yavicoli’s result for the specific setting of 3-point configurations by lowering the thickness threshold.

$\mathbb {R}^d$

generated by a restricted system of balls with significantly large thickness contain homothetic copies of finite sets [Reference Yavicoli40]. The current article offers an improvement to Yavicoli’s result for the specific setting of 3-point configurations by lowering the thickness threshold.

2 Main results

We investigate 3-point configurations in both

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

and in

$\mathbb {R}$

and in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

. Our first main results concern 3-point configurations on the real line. As an application, we demonstrate the existence of similar copies of any triangle in sets of the form

$\mathbb {R}^d$

. Our first main results concern 3-point configurations on the real line. As an application, we demonstrate the existence of similar copies of any triangle in sets of the form

![]() $C\times C$

when

$C\times C$

when

![]() $C\subset \mathbb {R}$

is compact and

$C\subset \mathbb {R}$

is compact and

![]() $\tau (C)\geq 1.$

These results appear in Section 2.1 and rely on the Newhouse gap lemma as a primary tool.

$\tau (C)\geq 1.$

These results appear in Section 2.1 and rely on the Newhouse gap lemma as a primary tool.

Our second main results concern the existence of arithmetic progressions and any other 3-point configuration in compact subsets of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

, including equilateral triangles. These results appear in Section 2.2 and rely on Yavicoli’s notion of thickness.

$\mathbb {R}^d$

, including equilateral triangles. These results appear in Section 2.2 and rely on Yavicoli’s notion of thickness.

2.1 3-Point configurations in

$\mathbb {R}$

& triangles in the plane part I

$\mathbb {R}$

& triangles in the plane part I

First, we demonstrate the following more general version of Proposition 1.1, which recovers the original result when

![]() $\lambda =\frac {1}{2}$

.

$\lambda =\frac {1}{2}$

.

Proposition 2.1 (Convex combinations in

$\mathbb {R}$

)

$\mathbb {R}$

)

Let

![]() $C\subset \mathbb {R}$

be a compact set with

$C\subset \mathbb {R}$

be a compact set with

![]() ${\tau (C)\geq 1}$

. Then, for each

${\tau (C)\geq 1}$

. Then, for each

![]() $\lambda \in (0, 1)$

, the set C contains a nondegenerate

$\lambda \in (0, 1)$

, the set C contains a nondegenerate

![]() $3$

-term progression of the form

$3$

-term progression of the form

In other words, any 3-point subset of the line is realized in C.

The proof of this result relies on demonstrating that

![]() $C\cap \left ( (1-\lambda ) C+ \lambda C \right )\neq \emptyset $

and is found in Section 4.

$C\cap \left ( (1-\lambda ) C+ \lambda C \right )\neq \emptyset $

and is found in Section 4.

As a consequence of Proposition 2.1 combined with the fact that the interior of the difference set

has non-empty interior, we have the following geometric consequence for triangles.

Theorem 2.2 (3-point configurations in

$C\times C$

)

$C\times C$

)

Let T denote any 3-point set in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^2$

. If

$\mathbb {R}^2$

. If

![]() $\tau (C) \geq 1$

, then

$\tau (C) \geq 1$

, then

![]() $C\times C$

contains a similar copy of T.

$C\times C$

contains a similar copy of T.

It follows from Theorem 2.2 that the Cartesian product

![]() $C\times C$

contains the vertices of a similar copy of any 3-point configuration whenever

$C\times C$

contains the vertices of a similar copy of any 3-point configuration whenever

![]() $C \subset \mathbb {R}$

is a compact set satisfying

$C \subset \mathbb {R}$

is a compact set satisfying

![]() $\tau (C) \geq 1$

. For emphasis, we state the result for equilateral triangles (see Figure 1).

$\tau (C) \geq 1$

. For emphasis, we state the result for equilateral triangles (see Figure 1).

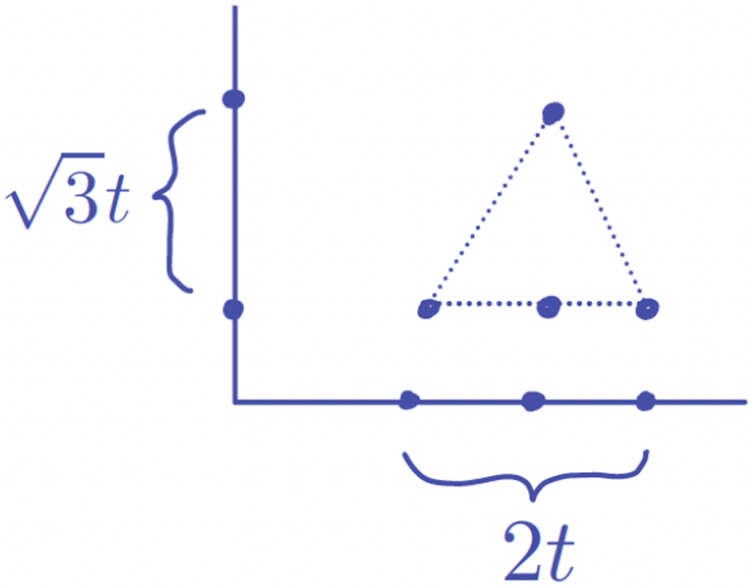

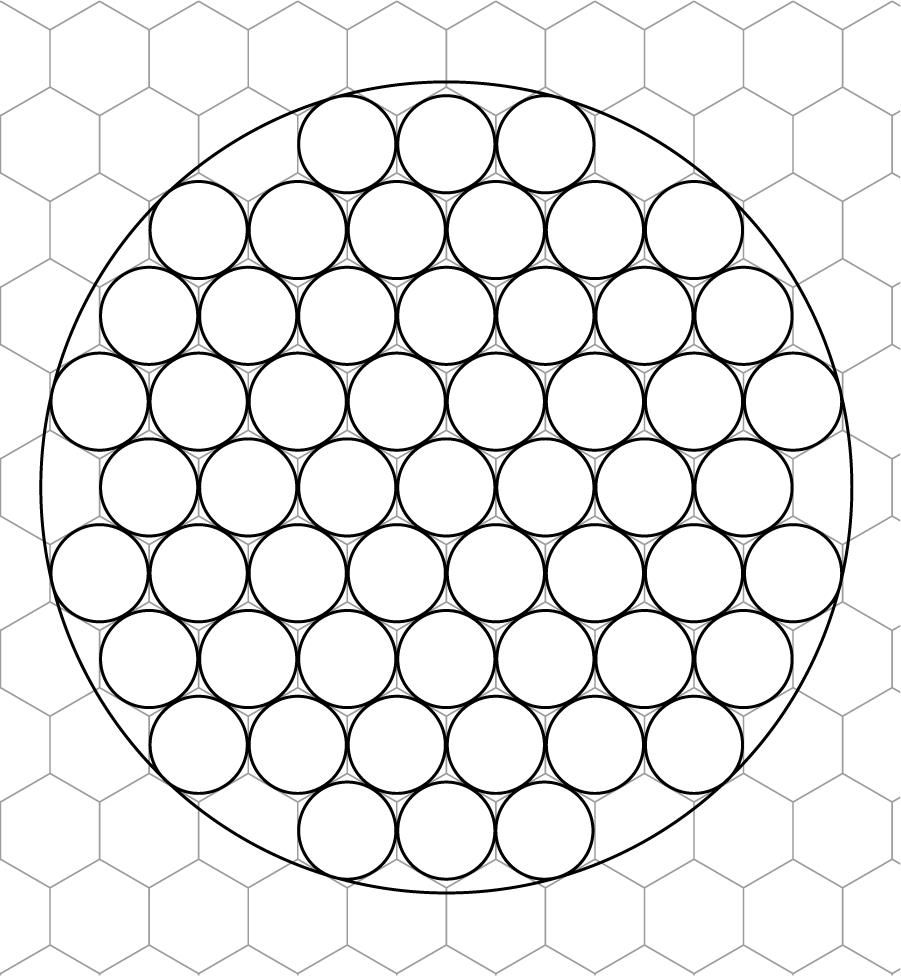

Figure 1: We see that

![]() $C\times C$

contains an equilateral triangle by combining two facts: (i) C contains an arithmetic progression

$C\times C$

contains an equilateral triangle by combining two facts: (i) C contains an arithmetic progression

![]() $\mathcal {A} = \{x, x+t, x+2t\}$

, where

$\mathcal {A} = \{x, x+t, x+2t\}$

, where

![]() $t>0$

can be taken arbitrarily small; (ii) the distance set

$t>0$

can be taken arbitrarily small; (ii) the distance set

![]() $\Delta (C)$

contains an interval

$\Delta (C)$

contains an interval

![]() $[0,\ell ]$

for some

$[0,\ell ]$

for some

![]() $\ell>0$

.

$\ell>0$

.

Corollary 2.3 If

![]() $\tau (C) \geq 1$

, then

$\tau (C) \geq 1$

, then

![]() $C\times C$

contains the vertices of an equilateral triangle.

$C\times C$

contains the vertices of an equilateral triangle.

The proofs for the results in this section appear in Section 4.

Remark 2.4 (Our result is a first of its kind in

$\mathbb {R}^2$

)

$\mathbb {R}^2$

)

Our Theorem 2.2 (and Theorem 2.12 below) are among the first in the literature to give explicit criteria for the occurrence of 3-point configurations in the plane, following the work of Chan–Łaba–Pramanik [Reference Chan, Łaba and Pramanik8] proving the existence of

![]() $3$

-term arithmetic progressions in some closed subsets of

$3$

-term arithmetic progressions in some closed subsets of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

with sufficient Fourier decay and power mass decay, respectively, and Yavicoli [Reference Yavicoli40] showing that subsets of

$\mathbb {R}^d$

with sufficient Fourier decay and power mass decay, respectively, and Yavicoli [Reference Yavicoli40] showing that subsets of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

of Yavicoli-thickness larger than

$\mathbb {R}^d$

of Yavicoli-thickness larger than

![]() $10^7$

contain

$10^7$

contain

![]() $3$

-point configurations.

$3$

-point configurations.

Remark 2.5 (Comparison between Newhouse thickness and Hausdorff dimension)

As mentioned above, Hausdorff dimension alone is not enough to guarantee the realization of similar triangles in subsets of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^2$

. Our result gives a class of compact Lebesgue null subsets of

$\mathbb {R}^2$

. Our result gives a class of compact Lebesgue null subsets of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^2$

and explicit criteria, mainly

$\mathbb {R}^2$

and explicit criteria, mainly

![]() $\tau (C)\geq 1$

, that guarantees the realization of a similar copy of any 3-point configuration in

$\tau (C)\geq 1$

, that guarantees the realization of a similar copy of any 3-point configuration in

![]() $C\times C$

. Because Hausdorff dimension and Newhouse thickness obey the following relationship [Reference Palis and Takens33] for

$C\times C$

. Because Hausdorff dimension and Newhouse thickness obey the following relationship [Reference Palis and Takens33] for

![]() $\tau (C)>0$

,

$\tau (C)>0$

,

$$ \begin{align*} \dim_H(C) \geq \frac{\log(2)}{\log(2+\frac{1}{\tau(C)})}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \dim_H(C) \geq \frac{\log(2)}{\log(2+\frac{1}{\tau(C)})}, \end{align*} $$

we can calculate a lower bound for the Hausdorff dimension of

![]() $C\times C$

using its thickness; i.e., since

$C\times C$

using its thickness; i.e., since

![]() $\tau (C)\geq 1$

, we know

$\tau (C)\geq 1$

, we know

![]() $\dim _H(C\times C)\geq 2\dim _H(C) \geq 2\frac {\log {2}}{\log {3}}$

.

$\dim _H(C\times C)\geq 2\dim _H(C) \geq 2\frac {\log {2}}{\log {3}}$

.

Remark 2.6 (Longer progressions)

For longer progressions, higher thickness is required. It is known that the middle-

![]() $\epsilon $

Cantor set

$\epsilon $

Cantor set

![]() $C_\epsilon $

does not contain arithmetic progressions of length

$C_\epsilon $

does not contain arithmetic progressions of length

![]() $\lfloor \frac {1}{\epsilon }\rfloor +2$

or larger. In particular, Broderick, Fishman, and Simmons [Reference Broderick, Fishman and Simmons7] proved that if

$\lfloor \frac {1}{\epsilon }\rfloor +2$

or larger. In particular, Broderick, Fishman, and Simmons [Reference Broderick, Fishman and Simmons7] proved that if

![]() $L_{\text {AP}}(S)$

denotes the maximal length of an arithmetic progression in a set

$L_{\text {AP}}(S)$

denotes the maximal length of an arithmetic progression in a set

![]() $S\subset \mathbb {R}$

, then for all

$S\subset \mathbb {R}$

, then for all

![]() $\epsilon>0$

sufficiently small and

$\epsilon>0$

sufficiently small and

![]() $n\in \mathbb {N}$

sufficiently large,

$n\in \mathbb {N}$

sufficiently large,

It is also not hard to see that

![]() $L_{\text {AP}}(C_\epsilon ) =2 $

for all

$L_{\text {AP}}(C_\epsilon ) =2 $

for all

![]() $\epsilon>\frac 13$

.

$\epsilon>\frac 13$

.

Further, using Newhouse’s gap lemma and symmetry,

![]() $L_{\text {AP}}(C_\epsilon ) \geq 4$

for all

$L_{\text {AP}}(C_\epsilon ) \geq 4$

for all

![]() $0<\epsilon \le \frac 13$

(this lower bound is attributed to Shmerkin and pointed out in [Reference Broderick, Fishman and Simmons7, Footnote 4]). Indeed, it follows by the gap lemma that there exists a

$0<\epsilon \le \frac 13$

(this lower bound is attributed to Shmerkin and pointed out in [Reference Broderick, Fishman and Simmons7, Footnote 4]). Indeed, it follows by the gap lemma that there exists a

![]() $t \in (C_\epsilon -\frac 12) \cap \frac 13(C_\epsilon - \frac 12)\neq \emptyset $

, and so we have

$t \in (C_\epsilon -\frac 12) \cap \frac 13(C_\epsilon - \frac 12)\neq \emptyset $

, and so we have

![]() $c_1, c_2 \in C_\epsilon $

so that

$c_1, c_2 \in C_\epsilon $

so that

By symmetry of

![]() $C_\epsilon $

about

$C_\epsilon $

about

![]() $\frac 12$

, we further have

$\frac 12$

, we further have

![]() $c_3, c_4 \in C_\epsilon $

so that

$c_3, c_4 \in C_\epsilon $

so that

which yields the desired

![]() $4$

-AP.

$4$

-AP.

Remark 2.7 (Sharpness of our result: the off-center Cantor set has thickness 1 and no

$4$

-AP)

$4$

-AP)

We now construct a set of thickness

![]() $1$

that contains no

$1$

that contains no

![]() $4$

-term arithmetic progressions. We call our construction the off-center Cantor set and denote it

$4$

-term arithmetic progressions. We call our construction the off-center Cantor set and denote it

![]() $C_a$

.

$C_a$

.

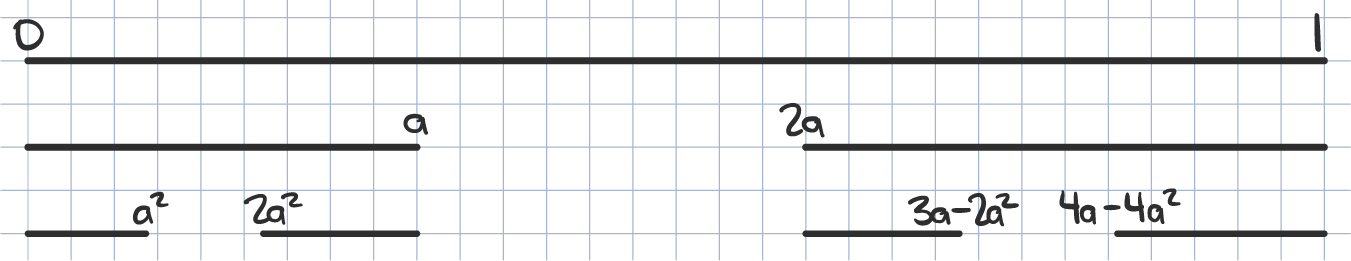

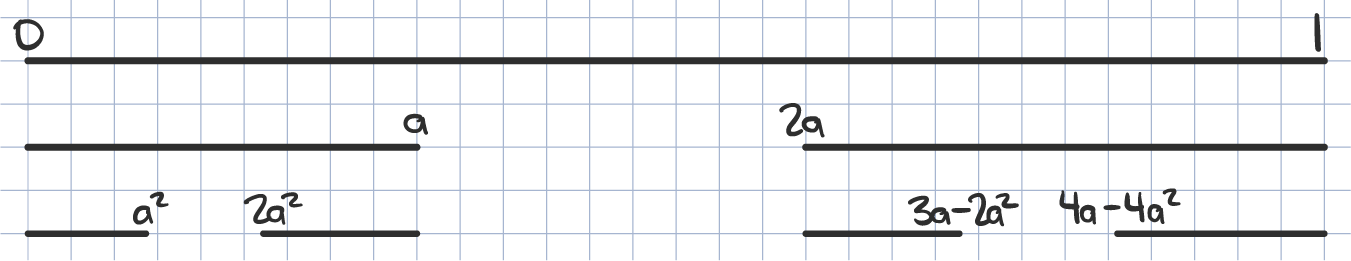

Let

![]() $0<a<\frac {1}{3}$

. We construct

$0<a<\frac {1}{3}$

. We construct

![]() $C_a$

iteratively, starting with

$C_a$

iteratively, starting with

![]() $[0,1]$

, by removing from each interval I an open interval of length

$[0,1]$

, by removing from each interval I an open interval of length

![]() $a|I|$

, call this open interval G. Then,

$a|I|$

, call this open interval G. Then,

![]() $I\setminus G$

is split into two closed intervals: the left interval L of length

$I\setminus G$

is split into two closed intervals: the left interval L of length

![]() $a|I|$

and the right interval R of length

$a|I|$

and the right interval R of length

![]() $(1-2a)|I|$

. Hence, we remove

$(1-2a)|I|$

. Hence, we remove

![]() $(a,2a)$

from

$(a,2a)$

from

![]() $[0,1]$

to obtain

$[0,1]$

to obtain

![]() $[0,a]\cup [2a,1]$

. From these intervals, we remove

$[0,a]\cup [2a,1]$

. From these intervals, we remove

![]() $(a^2,2a^2)$

and

$(a^2,2a^2)$

and

![]() $(3a-2a^2,4a-4a^2)$

to obtain

$(3a-2a^2,4a-4a^2)$

to obtain

![]() $[0,a^2]\cup [2a^2,a]\cup [2a,3a-2a^2]\cup [4a-4a^2,1]$

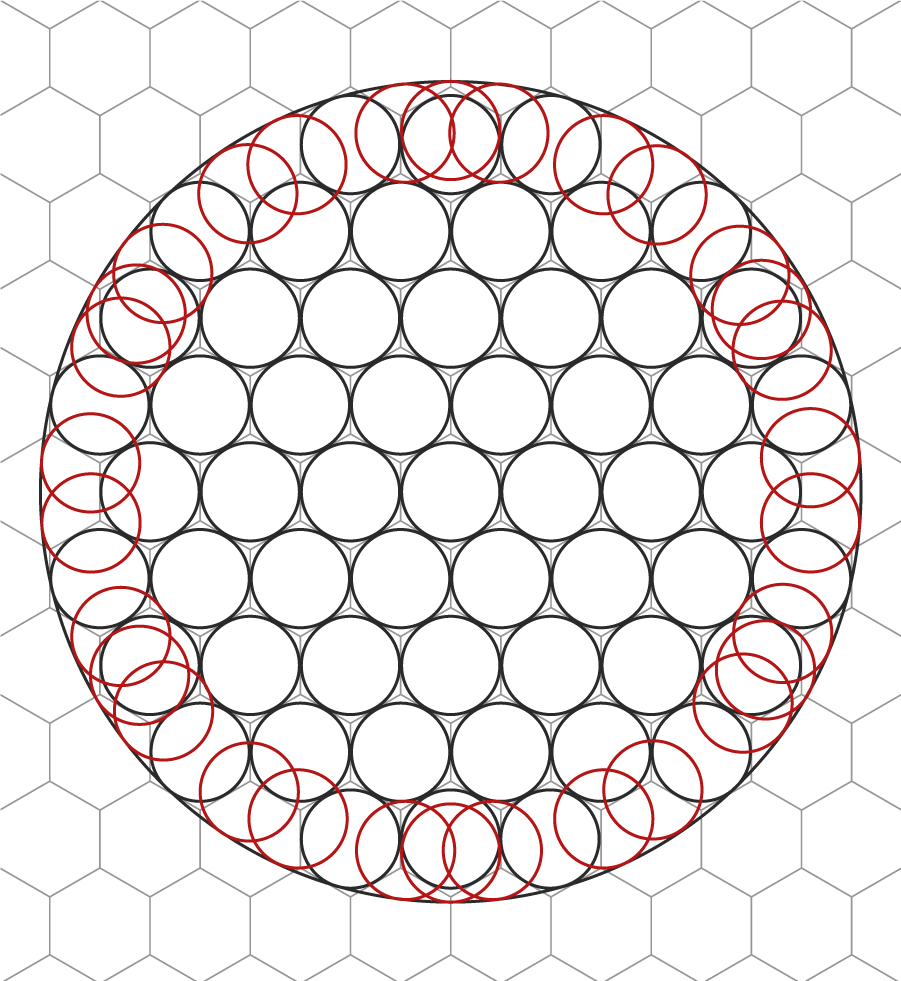

, and so on, as illustrated in Figure 2.

$[0,a^2]\cup [2a^2,a]\cup [2a,3a-2a^2]\cup [4a-4a^2,1]$

, and so on, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: First two iterations of off-center Cantor set

![]() $C_a$

for

$C_a$

for

![]() $a=\frac {3}{10}$

.

$a=\frac {3}{10}$

.

Observe that by construction

![]() $|L|=|G|< |R|$

; as this is true for every step in the construction of

$|L|=|G|< |R|$

; as this is true for every step in the construction of

![]() $C_a$

,

$C_a$

,

$$ \begin{align*}\tau(C_a) =\frac{\min\{|L|,|R|\}}{|G|}=1.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\tau(C_a) =\frac{\min\{|L|,|R|\}}{|G|}=1.\end{align*} $$

Thus,

![]() $C_a$

is a self-similar set of thickness

$C_a$

is a self-similar set of thickness

![]() $1$

.

$1$

.

We will now show

![]() $C_a$

does not contain any

$C_a$

does not contain any

![]() $4$

-term arithmetic progressions for

$4$

-term arithmetic progressions for

![]() $\frac {2-\sqrt {2}}{2}<a<\frac {3-\sqrt {3}}{4}$

. Assume to the contrary that

$\frac {2-\sqrt {2}}{2}<a<\frac {3-\sqrt {3}}{4}$

. Assume to the contrary that

![]() $C_a$

contains a

$C_a$

contains a

![]() $4$

-AP, call it

$4$

-AP, call it

![]() $P=\{x,x+y,x+2y,x+3y\}$

. Then, there exists some smallest interval in the construction of

$P=\{x,x+y,x+2y,x+3y\}$

. Then, there exists some smallest interval in the construction of

![]() $C_a$

that contains P but P is split over two levels in the next step of the construction. Because of the self-similarity of

$C_a$

that contains P but P is split over two levels in the next step of the construction. Because of the self-similarity of

![]() $C_a$

, we assume without loss of generality that P is contained in

$C_a$

, we assume without loss of generality that P is contained in

![]() $[0,1]$

but splits over

$[0,1]$

but splits over

![]() $[0,a]\cup [2a,1]$

.

$[0,a]\cup [2a,1]$

.

For P to be contained in

![]() $[0,1]$

and split over

$[0,1]$

and split over

![]() $[0,a]\cup [2a,1]$

, we must have

$[0,a]\cup [2a,1]$

, we must have

![]() $0\leq x\leq a$

,

$0\leq x\leq a$

,

![]() $y\geq a$

(otherwise the arithmetic progression cannot jump the gap

$y\geq a$

(otherwise the arithmetic progression cannot jump the gap

![]() $(a,2a)$

), and

$(a,2a)$

), and

![]() $x+3y\leq 1$

. Then, observe that

$x+3y\leq 1$

. Then, observe that

![]() $x+y\ngeq 2a$

because if it was then

$x+y\ngeq 2a$

because if it was then

a contradiction. We also have

![]() $x+y\notin (a,2a)$

; otherwise, P would not be contained in

$x+y\notin (a,2a)$

; otherwise, P would not be contained in

![]() $C_a$

. Thus, it must be the case that

$C_a$

. Thus, it must be the case that

![]() $x+y\in [0,a]$

. Because

$x+y\in [0,a]$

. Because

![]() $0\leq x\leq a$

,

$0\leq x\leq a$

,

![]() $y\geq a$

, and

$y\geq a$

, and

![]() $0\leq x+y\leq a$

, we conclude that

$0\leq x+y\leq a$

, we conclude that

![]() $x=0$

and

$x=0$

and

![]() $y=a$

, so

$y=a$

, so

![]() $P=\{0,a,2a,3a\}$

.

$P=\{0,a,2a,3a\}$

.

Notice that

![]() $0,a,2a\in C_a$

, so it remains to show

$0,a,2a\in C_a$

, so it remains to show

![]() $3a\notin C_a$

. By construction of

$3a\notin C_a$

. By construction of

![]() $C_a$

, the interval

$C_a$

, the interval

![]() $[4a-4a^2,1]$

is split by the gap

$[4a-4a^2,1]$

is split by the gap

![]() $(5a-8a^2+4a^3,6a-12a^2+8a^3)$

, and by the assumption that

$(5a-8a^2+4a^3,6a-12a^2+8a^3)$

, and by the assumption that

![]() $\frac {2-\sqrt {2}}{2}<a<\frac {3-\sqrt {3}}{4}$

, we know

$\frac {2-\sqrt {2}}{2}<a<\frac {3-\sqrt {3}}{4}$

, we know

![]() $3a\in (5a-8a^2+4a^3,6a-12a^2+8a^3)$

. Consequently,

$3a\in (5a-8a^2+4a^3,6a-12a^2+8a^3)$

. Consequently,

![]() $C_a$

cannot contain P. By self-similarity,

$C_a$

cannot contain P. By self-similarity,

![]() $C_a$

cannot contain any

$C_a$

cannot contain any

![]() $4$

-term arithmetic progressions.

$4$

-term arithmetic progressions.

In the next section, we introduce higher-dimensional variants of Proposition 2.1 (on 3-point configurations on the line) and Theorem 2.2 (on triangles in the plane) that do not depend on Cartesian product structure.

2.2 3-Point configurations in

$\mathbb {R}^d$

& triangles in the plane part II

$\mathbb {R}^d$

& triangles in the plane part II

In this section, we introduce results in dimensions

![]() $d\geq 2$

. Theorem 2.8 of this section yields conditions to guarantee the occurrence of arithmetic progressions and other linear 3-point configurations in

$d\geq 2$

. Theorem 2.8 of this section yields conditions to guarantee the occurrence of arithmetic progressions and other linear 3-point configurations in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

. Beyond linear combinations, Theorem 2.12 guarantees the occurrence of a similar copy of any 3-point configuration in higher dimensions.

$\mathbb {R}^d$

. Beyond linear combinations, Theorem 2.12 guarantees the occurrence of a similar copy of any 3-point configuration in higher dimensions.

Here, we use a higher-dimensional notion of thickness introduced by Yavicoli [Reference Yavicoli40]. We directly state the results of this section, and we delay formal introduction of Yavicoli thickness and the corresponding gap lemma to Section 3. We require the notion of a system of balls and r-uniformity, which will also be defined in Section 3.

Our first result says that a compact set C generated by a system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

in

$\{S_I\}_I$

in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

with Yavicoli thickness (Definition 3.2 below) satisfying

$\mathbb {R}^d$

with Yavicoli thickness (Definition 3.2 below) satisfying

for some

![]() $0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

contains a

$0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

contains a

![]() $3$

-point arithmetic progression; e.g., any

$3$

-point arithmetic progression; e.g., any

![]() $\frac {1}{4}$

-uniformly compact set of thickness greater than

$\frac {1}{4}$

-uniformly compact set of thickness greater than

![]() $4$

contains an arithmetic progression of length

$4$

contains an arithmetic progression of length

![]() $3$

.

$3$

.

The proof of this result is inspired by the proof of Proposition 1.1. For a compact set C, we take two disjoint subsets A and B and apply the Gap Lemma to show that

![]() $C\cap \left (\lambda A +(1-\lambda )B\right ) \neq \emptyset $

. The assumption that

$C\cap \left (\lambda A +(1-\lambda )B\right ) \neq \emptyset $

. The assumption that

![]() $0<r< \frac 12$

is used to apply the gap lemma in Theorem 3.2. Our proofs quickly diverge, though, as we lose the well-ordering of

$0<r< \frac 12$

is used to apply the gap lemma in Theorem 3.2. Our proofs quickly diverge, though, as we lose the well-ordering of

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

in higher dimensions and the higher-dimensional Gap Lemma has a number of additional assumptions to verify over the one-dimensional Gap Lemma.

$\mathbb {R}$

in higher dimensions and the higher-dimensional Gap Lemma has a number of additional assumptions to verify over the one-dimensional Gap Lemma.

In particular, our method views compact sets in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

as a sequence of nested balls, each generation of which is finite, and our method requires the existence of two first-generation children, call them

$\mathbb {R}^d$

as a sequence of nested balls, each generation of which is finite, and our method requires the existence of two first-generation children, call them

![]() $S_{1_A}$

and

$S_{1_A}$

and

![]() $S_{1_B}$

, out of the total

$S_{1_B}$

, out of the total

![]() $k_\emptyset $

first-generation children that are both disjoint from all first-generation children; these first-generation children

$k_\emptyset $

first-generation children that are both disjoint from all first-generation children; these first-generation children

![]() $S_{1_A}$

and

$S_{1_A}$

and

![]() $S_{1_B}$

are used to construct the sets A, B mentioned above. This requirement is explained in Section 3.1.

$S_{1_B}$

are used to construct the sets A, B mentioned above. This requirement is explained in Section 3.1.

Theorem 2.8 (Convex combinations in

$\mathbb {R}^d$

)

$\mathbb {R}^d$

)

Let C be a compact set in

![]() $(\mathbb {R}^d,\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}})$

generated by the system of balls

$(\mathbb {R}^d,\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}})$

generated by the system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

such that C is r-uniformly dense where

$\{S_I\}_I$

such that C is r-uniformly dense where

![]() $ 0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

. Let

$ 0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

. Let

![]() $\lambda \in (0,\frac 12]$

, and suppose that

$\lambda \in (0,\frac 12]$

, and suppose that

$$ \begin{align*}\tau\left( C,\{S_I\}\right) \geq \frac{2(1-\lambda)}{\lambda(1-2r)}.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\tau\left( C,\{S_I\}\right) \geq \frac{2(1-\lambda)}{\lambda(1-2r)}.\end{align*} $$

Suppose that there exist distinct first-generation children disjoint from all other children:

![]() $S_{1_A}$

and

$S_{1_A}$

and

![]() $S_{1_B}$

with

$S_{1_B}$

with

![]() $1\leq 1_A<1_B\leq k_\emptyset $

such that

$1\leq 1_A<1_B\leq k_\emptyset $

such that

![]() $S_{1_A} \cap S_i = \emptyset $

and

$S_{1_A} \cap S_i = \emptyset $

and

![]() $S_{1_B}\cap S_i =\emptyset $

for all

$S_{1_B}\cap S_i =\emptyset $

for all

![]() $i\neq 1_A,1_B$

where

$i\neq 1_A,1_B$

where

![]() $1\leq i\leq k_\emptyset $

. Then, C contains a

$1\leq i\leq k_\emptyset $

. Then, C contains a

![]() $3$

-point convex combination of the form

$3$

-point convex combination of the form

In particular, under the hypotheses above with

![]() $\lambda = \frac {1}{2}$

, we have the following.

$\lambda = \frac {1}{2}$

, we have the following.

Corollary 2.9 (

$3$

-term arithmetic progressions in

$3$

-term arithmetic progressions in

$\mathbb {R}^d$

)

$\mathbb {R}^d$

)

Let C be a compact set in

![]() $(\mathbb {R}^d,\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}})$

generated by the system of balls

$(\mathbb {R}^d,\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}})$

generated by the system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

such that C is r-uniformly dense, where

$\{S_I\}_I$

such that C is r-uniformly dense, where

![]() $ 0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

. Suppose that

$ 0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

. Suppose that

and suppose that there exist distinct first-generation children of

![]() $\{S_I\}$

disjoint from all other children. Then, C contains an arithmetic progression

$\{S_I\}$

disjoint from all other children. Then, C contains an arithmetic progression

![]() $\{a, \frac {1}{2}(a+b),b\}$

with

$\{a, \frac {1}{2}(a+b),b\}$

with

![]() $a\neq b$

.

$a\neq b$

.

Remark 2.10 Observe Theorem 2.8 has a thickness condition that depends on r and

![]() $\lambda $

, whereas the one-dimensional analog, Proposition 2.1, does not. In the higher-dimensional Gap Lemma 3.2, there are additional assumptions such as r-uniformity and the relationships in (ii) and (iii) which ensure the sets are interwoven. These additional assumptions lead to a thickness condition that depends on r and

$\lambda $

, whereas the one-dimensional analog, Proposition 2.1, does not. In the higher-dimensional Gap Lemma 3.2, there are additional assumptions such as r-uniformity and the relationships in (ii) and (iii) which ensure the sets are interwoven. These additional assumptions lead to a thickness condition that depends on r and

![]() $\lambda $

.

$\lambda $

.

Next, we prove a result on the existence of triangles in compact sets of sufficient Yavicoli thickness, but first we need a way to categorize all triangles.

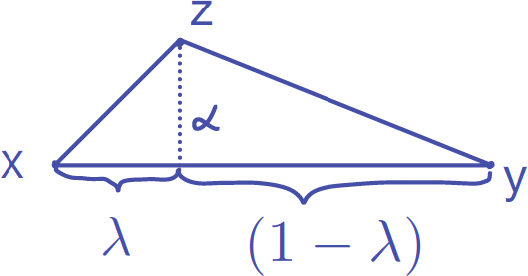

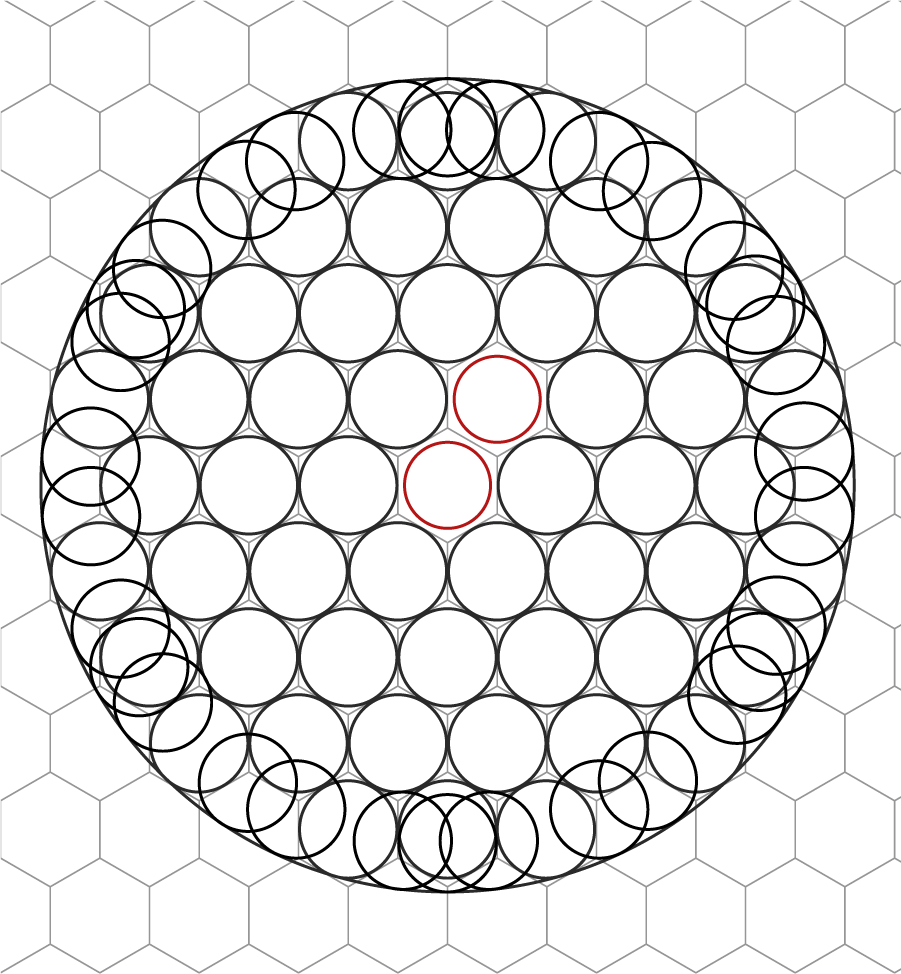

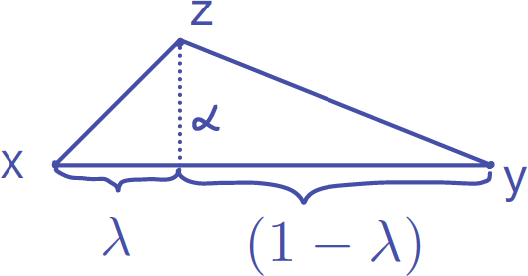

Definition 2.1 (Normalized triangle, Figure 3)

For

![]() $\alpha \geq 0$

,

$\alpha \geq 0$

,

![]() $\lambda \in (0,\frac 12]$

, we define

$\lambda \in (0,\frac 12]$

, we define

![]() $\mathcal {T}(\alpha ,\lambda )$

as the triangle consisting of the vertices

$\mathcal {T}(\alpha ,\lambda )$

as the triangle consisting of the vertices

![]() $\{x,y,z\}$

such that the angle at vertex z,

$\{x,y,z\}$

such that the angle at vertex z,

![]() $\theta _z$

, is the largest angle, and we normalize the longest side of the triangle, the side between vertices x and y, to be

$\theta _z$

, is the largest angle, and we normalize the longest side of the triangle, the side between vertices x and y, to be

![]() $1$

; i.e.,

$1$

; i.e.,

![]() $|y-x|=1$

. Let

$|y-x|=1$

. Let

![]() $\alpha $

denote the height of the triangle. The altitude from z bisects the line segment from x to y into two segments, and we denote their lengths by

$\alpha $

denote the height of the triangle. The altitude from z bisects the line segment from x to y into two segments, and we denote their lengths by

![]() $\lambda $

and

$\lambda $

and

![]() $(1-\lambda )$

.

$(1-\lambda )$

.

Figure 3: The triangle

![]() $T(\alpha ,\lambda )$

with vertices

$T(\alpha ,\lambda )$

with vertices

![]() $x,y,z$

, largest angle at z, height

$x,y,z$

, largest angle at z, height

![]() $\alpha $

, and base

$\alpha $

, and base

![]() $1$

.

$1$

.

Lemma 2.11 Let

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

be the vertices of any non-degenerate triangle in

$\mathcal {T}$

be the vertices of any non-degenerate triangle in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^2$

. Then, there exists an

$\mathbb {R}^2$

. Then, there exists an

![]() $(\alpha ,\lambda )$

in

$(\alpha ,\lambda )$

in

such that

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

is similar to the triangle

$\mathcal {T}$

is similar to the triangle

![]() $\mathcal {T}(\alpha ,\lambda )$

.

$\mathcal {T}(\alpha ,\lambda )$

.

The lemma is immediate upon scaling, rotating, and labeling the vertices appropriately; the above inequalities are a simple consequence of the Pythagorean theorem.

Theorem 2.12 (Triangles in

$\mathbb {R}^2$

)

$\mathbb {R}^2$

)

Let

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

denote the vertices of any triangle in

$\mathcal {T}$

denote the vertices of any triangle in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^2$

, and let

$\mathbb {R}^2$

, and let

![]() $\mathcal {T}(\alpha ,\lambda )$

be a triangle similar to

$\mathcal {T}(\alpha ,\lambda )$

be a triangle similar to

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

resulting from Lemma 2.11 for some

$\mathcal {T}$

resulting from Lemma 2.11 for some

![]() $\alpha $

,

$\alpha $

,

![]() $\lambda $

in

$\lambda $

in

![]() $\mathcal {R}$

. Let

$\mathcal {R}$

. Let

![]() $C\subset \mathbb {R}^2$

be a compact set generated by the system of balls

$C\subset \mathbb {R}^2$

be a compact set generated by the system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}$

in the Euclidean norm such that C is r-uniformly dense for some

$\{S_I\}$

in the Euclidean norm such that C is r-uniformly dense for some

![]() $0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

. Suppose there exists distinct first-generation children

$0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

. Suppose there exists distinct first-generation children

![]() $S_{1_A}$

and

$S_{1_A}$

and

![]() $S_{1_B}$

,

$S_{1_B}$

,

![]() $1\leq 1_A<1_B\leq k_\emptyset $

, contained in

$1\leq 1_A<1_B\leq k_\emptyset $

, contained in

![]() $\bar {B}\left (0,\frac {1}{2}\right )$

such that

$\bar {B}\left (0,\frac {1}{2}\right )$

such that

![]() $S_{1_A}$

and

$S_{1_A}$

and

![]() $S_{1_B}$

are disjoint from all other first-generation children; i.e.,

$S_{1_B}$

are disjoint from all other first-generation children; i.e.,

![]() $S_{1_A}\cap S_i=\emptyset $

for all

$S_{1_A}\cap S_i=\emptyset $

for all

![]() $i\neq 1_A$

, and

$i\neq 1_A$

, and

![]() $S_{1_B}\cap S_i=\emptyset $

for all

$S_{1_B}\cap S_i=\emptyset $

for all

![]() $i\neq 1_B$

. Further, suppose

$i\neq 1_B$

. Further, suppose

$$ \begin{align*}\tau\left( C,\{S_I\}\right) \geq \sqrt{\frac{\alpha^2+(1-\lambda)^2}{\alpha^2+\lambda^2}}\cdot \frac{2}{1-2r},\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\tau\left( C,\{S_I\}\right) \geq \sqrt{\frac{\alpha^2+(1-\lambda)^2}{\alpha^2+\lambda^2}}\cdot \frac{2}{1-2r},\end{align*} $$

then C contains the vertices of a similar copy of

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

.

$\mathcal {T}$

.

In other words, given any 3-point set

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

, any set C satisfying the hypotheses contains a similar copy of

$\mathcal {T}$

, any set C satisfying the hypotheses contains a similar copy of

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

. A key tool in the proof is the higher gap lemma due to Yavicoli (see Theorem 3.2); the hypothesis that

$\mathcal {T}$

. A key tool in the proof is the higher gap lemma due to Yavicoli (see Theorem 3.2); the hypothesis that

![]() $r\in (0,\frac 12)$

is an assumption of the Gap lemma.

$r\in (0,\frac 12)$

is an assumption of the Gap lemma.

Remark 2.13 We suspect this holds in higher dimensions, but there are technical complexities that arise.

For equilateral triangles,

![]() $\lambda =\frac 12$

and

$\lambda =\frac 12$

and

![]() $\alpha = \frac {\sqrt {3}}{2}$

, and the thickness assumption is simplified so that we have the following.

$\alpha = \frac {\sqrt {3}}{2}$

, and the thickness assumption is simplified so that we have the following.

Corollary 2.14 (Equilateral triangles in

$\mathbb {R}^2$

)

$\mathbb {R}^2$

)

Let

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

denote the vertices of an equilateral triangle. Let

$\mathcal {T}$

denote the vertices of an equilateral triangle. Let

![]() $C\subset \mathbb {R}^2$

be a compact set generated by the system of balls

$C\subset \mathbb {R}^2$

be a compact set generated by the system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}$

in the Euclidean norm such that C is r-uniformly dense for some

$\{S_I\}$

in the Euclidean norm such that C is r-uniformly dense for some

![]() $0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

. Suppose there exists first-generation children

$0<r<\frac {1}{2}$

. Suppose there exists first-generation children

![]() $S_{1_A}$

and

$S_{1_A}$

and

![]() $S_{1_B}$

,

$S_{1_B}$

,

![]() $1\leq 1_A<1_B\leq k_\emptyset $

, contained in

$1\leq 1_A<1_B\leq k_\emptyset $

, contained in

![]() $\bar {B}\left (0,\frac {1}{2}\right )$

such that

$\bar {B}\left (0,\frac {1}{2}\right )$

such that

![]() $S_{1_A}$

and

$S_{1_A}$

and

![]() $S_{1_B}$

are disjoint from all other first-generation children. Further, suppose

$S_{1_B}$

are disjoint from all other first-generation children. Further, suppose

then C contains the vertices of a similar copy of

![]() $\mathcal {T}$

.

$\mathcal {T}$

.

Remark 2.15 Above, we assume that

![]() $S_{1_A}$

,

$S_{1_A}$

,

![]() $S_{1_B}$

are contained in

$S_{1_B}$

are contained in

![]() $\bar {B}\left ( 0,\frac {1}{2}\right )$

, but this is not optimal. In the proof of Theorem 2.12, we will show that taking

$\bar {B}\left ( 0,\frac {1}{2}\right )$

, but this is not optimal. In the proof of Theorem 2.12, we will show that taking

![]() $S_{1_A}$

and

$S_{1_A}$

and

![]() $S_{1_B}$

in the larger ball,

$S_{1_B}$

in the larger ball,

![]() $\bar {B}\left ( 0, \frac {1}{2}+t_1-\frac {h_\emptyset (C) x}{2s_f}\right )$

, where the variables

$\bar {B}\left ( 0, \frac {1}{2}+t_1-\frac {h_\emptyset (C) x}{2s_f}\right )$

, where the variables

![]() $t_1, h_\emptyset (C)$

, and

$t_1, h_\emptyset (C)$

, and

![]() $s_f$

are defined in the proof, and

$s_f$

are defined in the proof, and

![]() $x=\max \left \{\frac {2r}{1-2r},0\right \}$

is sufficient.

$x=\max \left \{\frac {2r}{1-2r},0\right \}$

is sufficient.

Before, to guarantee the occurrence of a

![]() $3$

-AP, we needed

$3$

-AP, we needed

![]() $C\cap \left (\frac {A+B}{2}\right )\neq \emptyset $

for

$C\cap \left (\frac {A+B}{2}\right )\neq \emptyset $

for

![]() $A, B$

disjoint subsets of C. Now, to guarantee the occurrence of the vertices of an equilateral triangle, we need

$A, B$

disjoint subsets of C. Now, to guarantee the occurrence of the vertices of an equilateral triangle, we need

![]() $C\cap \left (H(A,B)\right )\neq \emptyset $

, where

$C\cap \left (H(A,B)\right )\neq \emptyset $

, where

![]() $H: \mathbb {R}^2\times \mathbb {R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^2$

is defined by

$H: \mathbb {R}^2\times \mathbb {R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^2$

is defined by

![]() $H(a,b) = \frac {a+b}{2} + \frac {\sqrt {3}}{2}(b-a)^{\perp }$

. This ensures that there’s some point

$H(a,b) = \frac {a+b}{2} + \frac {\sqrt {3}}{2}(b-a)^{\perp }$

. This ensures that there’s some point

![]() $a\in A$

,

$a\in A$

,

![]() $b\in B$

forming the base of our equilateral triangle and some point

$b\in B$

forming the base of our equilateral triangle and some point

![]() $c\in C\cap H(A,B)$

as the top vertex. The details are found in Section 5.3.

$c\in C\cap H(A,B)$

as the top vertex. The details are found in Section 5.3.

Remark 2.16 Theorem 2.12 offers a significant improvement over the following result of Yavicoli in the specific setting of triangles in the plane by lowering the required thickness threshold; however, for values of

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\lambda $

significantly close to

$\lambda $

significantly close to

![]() $0$

, Yavicoli’s result requires less thickness. Yavicoli proved that compact sets in

$0$

, Yavicoli’s result requires less thickness. Yavicoli proved that compact sets in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

generated by a restricted system of balls in the infinity norm with significantly large thickness contain homothetic copies of finite sets [Reference Yavicoli40]. In particular, let

$\mathbb {R}^d$

generated by a restricted system of balls in the infinity norm with significantly large thickness contain homothetic copies of finite sets [Reference Yavicoli40]. In particular, let

![]() $C\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

be a compact set with disjoint children. Take also constraints on the number of children

$C\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

be a compact set with disjoint children. Take also constraints on the number of children

![]() $N_0$

and the radii of the children. Then, C contains a homothetic copy of every set with at most

$N_0$

and the radii of the children. Then, C contains a homothetic copy of every set with at most

$$ \begin{align*} N(\tau):= \left\lfloor\frac{3}{4eK_2}\frac{\tau}{\log\tau}\right\rfloor \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} N(\tau):= \left\lfloor\frac{3}{4eK_2}\frac{\tau}{\log\tau}\right\rfloor \end{align*} $$

elements where

![]() $K_2$

is a large constant dependent on

$K_2$

is a large constant dependent on

![]() $N_0$

. In fact, we can take the conservative estimate of

$N_0$

. In fact, we can take the conservative estimate of

![]() $K_2=360,000$

which means we would need a thickness strictly greater than

$K_2=360,000$

which means we would need a thickness strictly greater than

![]() $10^7$

to guarantee the existence of any

$10^7$

to guarantee the existence of any

![]() $3$

-point configuration.

$3$

-point configuration.

2.3 Organization

In Section 3, we introduce systems of balls for compact sets, define r-uniformity, and introduce Yavicoli’s higher-dimensional thickness and gap lemma. We also discuss some relevant properties of this notion of thickness, including its behavior under taking subsets. In Section 6, we give some examples. Section 4 contains the proofs of the results of Section 2.1 that rely on Newhouse thickness, and the proofs of the results in Section 2.2 that rely on Yavicoli thickness appear in Section 5.

3 Yavicoli thickness in

$\mathbb {R}^d$

$\mathbb {R}^d$

In this section, we review the definitions and theorems related to thickness in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

as introduced by Yavicoli [Reference Yavicoli40], and we present the lemmas used in the proofs of Theorems 2.8 and 2.12. We begin with an observation about compact sets and the definition of a system of balls.

$\mathbb {R}^d$

as introduced by Yavicoli [Reference Yavicoli40], and we present the lemmas used in the proofs of Theorems 2.8 and 2.12. We begin with an observation about compact sets and the definition of a system of balls.

Definition 3.1 (Compact sets and systems of balls, [Reference Yavicoli40])

Given a word I (i.e., a finite or infinite), we denote by

![]() $\ell (I)\in \mathbb {N}_0$

the length of I. Observe that any compact set can be written as

$\ell (I)\in \mathbb {N}_0$

the length of I. Observe that any compact set can be written as

where

-

• each

$S_I$

is a closed ball in the norm

$S_I$

is a closed ball in the norm

$\|\cdot \|_\infty $

or

$\|\cdot \|_\infty $

or

$ \|\cdot \|_2$

and contains

$ \|\cdot \|_2$

and contains

$\{S_{I,j}\}_{1\leq j\leq k_I}$

, for

$\{S_{I,j}\}_{1\leq j\leq k_I}$

, for

$k_I \in \mathbb {N}$

; (No assumptions are made on the separation of the

$k_I \in \mathbb {N}$

; (No assumptions are made on the separation of the

$S_{I,j}$

.)

$S_{I,j}$

.) -

• for every infinite word

$i_1,i_2,\ldots $

of indices of the construction,

$i_1,i_2,\ldots $

of indices of the construction,  $$ \begin{align*} \lim_{n\rightarrow+\infty} \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}} S_{i_1,i_2,\ldots,i_n}=0; \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \lim_{n\rightarrow+\infty} \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}} S_{i_1,i_2,\ldots,i_n}=0; \end{align*} $$

-

• for every word I,

$S_I \cap C \neq \emptyset $

.

$S_I \cap C \neq \emptyset $

.

We use the notation

![]() $C\subset S_\emptyset = S_0$

and

$C\subset S_\emptyset = S_0$

and

![]() $k_\emptyset = k_0 \in \mathbb {N}$

. In this case, we say that C is generated by the system of balls

$k_\emptyset = k_0 \in \mathbb {N}$

. In this case, we say that C is generated by the system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

, or that

$\{S_I\}_I$

, or that

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

is a system of balls for C.

$\{S_I\}_I$

is a system of balls for C.

When considering thickness in higher dimensions, we no longer have interval bridges and gaps as we did in

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

. Instead, given a compact set

$\mathbb {R}$

. Instead, given a compact set

![]() $C\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

and a system of balls

$C\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

and a system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

, and given a fixed level (or generation) n in the construction, we fix a parent square

$\{S_I\}_I$

, and given a fixed level (or generation) n in the construction, we fix a parent square

![]() $S_I$

. We then consider the ratio between two quantities: the minimum radius over the children balls

$S_I$

. We then consider the ratio between two quantities: the minimum radius over the children balls

![]() $\{S_{I,i}\}$

and the radius of the largest disc that fits in

$\{S_{I,i}\}$

and the radius of the largest disc that fits in

![]() $S_I$

and avoids the set C (call this quantity

$S_I$

and avoids the set C (call this quantity

![]() $h_I(C)$

). Taking an infimum over all parents at level n, and then taking an infimum over all generations

$h_I(C)$

). Taking an infimum over all parents at level n, and then taking an infimum over all generations

![]() $n\geq 0$

gives a higher-dimensional notion of thickness.

$n\geq 0$

gives a higher-dimensional notion of thickness.

Definition 3.2 (Thickness of C associated to the system of balls

$\{S_I\}_I$

, [Reference Yavicoli40])

$\{S_I\}_I$

, [Reference Yavicoli40])

$$ \begin{align} \tau\left( C,\{S_I\}_I\right):=\inf_{n\geq 0}\inf_{\ell(I)=n}\frac{\min_i \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}}(S_{I,i})}{h_I(C)} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \tau\left( C,\{S_I\}_I\right):=\inf_{n\geq 0}\inf_{\ell(I)=n}\frac{\min_i \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}}(S_{I,i})}{h_I(C)} \end{align} $$

where

Note that

![]() $h_I(C)$

is geometrically interpreted to be minimal so that any ball of radius

$h_I(C)$

is geometrically interpreted to be minimal so that any ball of radius

![]() $h_I(C)$

or larger in

$h_I(C)$

or larger in

![]() $S_I$

must contain a point of C for a fixed word I.

$S_I$

must contain a point of C for a fixed word I.

Remark 3.1 The system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}$

is included as a parameter in the definition of thickness because both the numerator

$\{S_I\}$

is included as a parameter in the definition of thickness because both the numerator

![]() $\min _i \operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(S_{I,i})$

and denominator

$\min _i \operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(S_{I,i})$

and denominator

![]() $h_I(C)$

are dependent upon the system of balls used to describe the compact set. Let us examine two examples that illustrate this dependence.

$h_I(C)$

are dependent upon the system of balls used to describe the compact set. Let us examine two examples that illustrate this dependence.

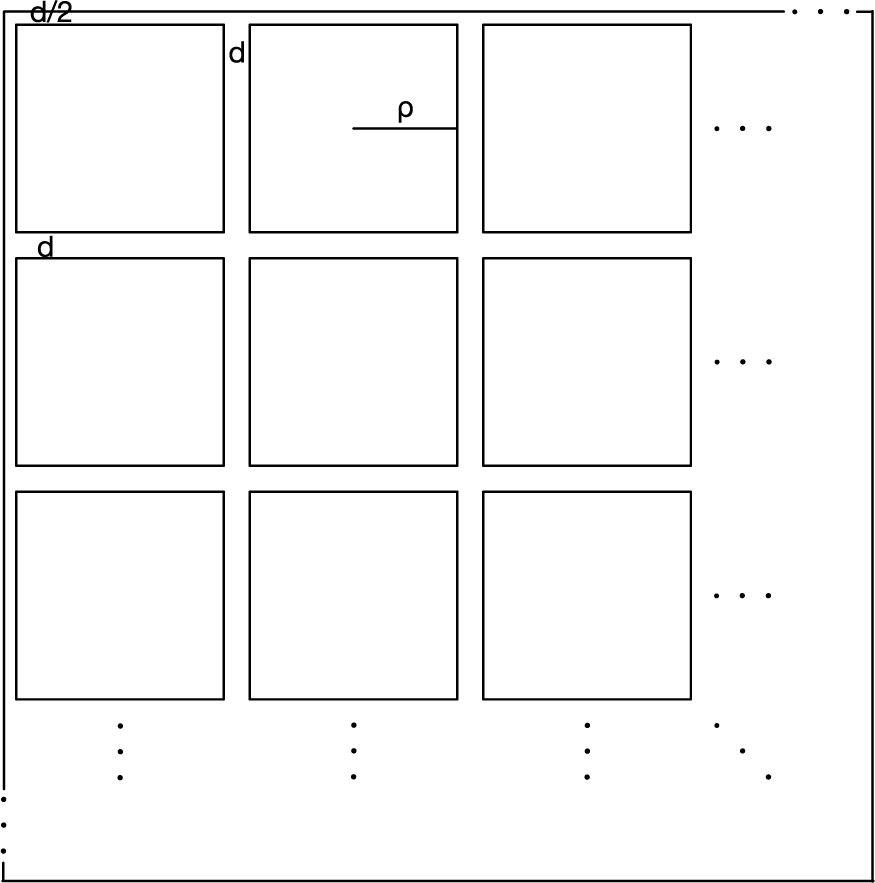

First, recall that any compact set C in

![]() $\bar {B}(0,1)$

can be generated by a system of balls constructed by using a system of dyadic squares. For example, in

$\bar {B}(0,1)$

can be generated by a system of balls constructed by using a system of dyadic squares. For example, in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^2$

, we could start with

$\mathbb {R}^2$

, we could start with

![]() $\bar {B}(0,1)$

, then partition

$\bar {B}(0,1)$

, then partition

![]() $\bar {B}(0,1)$

into four parts by

$\bar {B}(0,1)$

into four parts by

![]() $\bar {B}\left ( (-\frac {1}{2},\frac {1}{2}), \frac {1}{2}\right )$

,

$\bar {B}\left ( (-\frac {1}{2},\frac {1}{2}), \frac {1}{2}\right )$

,

![]() $\bar {B}\left ( (\frac {1}{2},\frac {1}{2}), \frac {1}{2}\right )$

,

$\bar {B}\left ( (\frac {1}{2},\frac {1}{2}), \frac {1}{2}\right )$

,

![]() $\bar {B}\left ( (-\frac {1}{2},\frac {1}{2}), -\frac {1}{2}\right )$

, and

$\bar {B}\left ( (-\frac {1}{2},\frac {1}{2}), -\frac {1}{2}\right )$

, and

![]() $\bar {B}\left ( (\frac {1}{2},-\frac {1}{2}), \frac {1}{2}\right )$

, and partition each

$\bar {B}\left ( (\frac {1}{2},-\frac {1}{2}), \frac {1}{2}\right )$

, and partition each

![]() $\bar {B}\left ( (\pm \frac {1}{2},\pm \frac {1}{2}), \frac {1}{2}\right )$

into four parts, and so on. If a dyadic square intersects C, include it in the system of balls

$\bar {B}\left ( (\pm \frac {1}{2},\pm \frac {1}{2}), \frac {1}{2}\right )$

into four parts, and so on. If a dyadic square intersects C, include it in the system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}$

; otherwise, exclude it. Notice that this means that each

$\{S_I\}$

; otherwise, exclude it. Notice that this means that each

![]() $S_I$

has radius

$S_I$

has radius

![]() $\frac {1}{2^{\ell (I)}}$

with

$\frac {1}{2^{\ell (I)}}$

with

![]() $k_I$

children where

$k_I$

children where

![]() $0\leq k_I\leq 4$

. Such a system

$0\leq k_I\leq 4$

. Such a system

![]() $\{S_I\}$

will necessarily generate any compact set

$\{S_I\}$

will necessarily generate any compact set

![]() $C\subset \bar {B}(0,1)$

. However, if C is not the entire compact ball, then any C generated by these dyadic balls will always have thickness at most

$C\subset \bar {B}(0,1)$

. However, if C is not the entire compact ball, then any C generated by these dyadic balls will always have thickness at most

![]() $1/2$

, as at some point in the construction we will have some

$1/2$

, as at some point in the construction we will have some

![]() $S_J$

which does not contain an element of C, so

$S_J$

which does not contain an element of C, so

![]() $h_J(C) \geq \frac {1}{2^{\ell (J)}}$

. Then

$h_J(C) \geq \frac {1}{2^{\ell (J)}}$

. Then

$$ \begin{align*}\tau\left( C, \{S_I\}\right) = \inf_{n\geq0}\inf_{\ell(I)=n} \frac{\min_i \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}}(S_{I,i})}{\max_{x\in S_I}\operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,C)} \leq \frac{1/2^{\ell(J)+1}}{1/2^{\ell(J)}} = \frac{1}{2}.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\tau\left( C, \{S_I\}\right) = \inf_{n\geq0}\inf_{\ell(I)=n} \frac{\min_i \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}}(S_{I,i})}{\max_{x\in S_I}\operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,C)} \leq \frac{1/2^{\ell(J)+1}}{1/2^{\ell(J)}} = \frac{1}{2}.\end{align*} $$

Hence, we can artificially force any compact set to have artificially small thickness. This illustrates that when constructing a system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

for a compact set C with thickness larger than

$\{S_I\}_I$

for a compact set C with thickness larger than

![]() $1$

we need to choose the balls in such a way that the smallest radius is larger than the largest distance to C.

$1$

we need to choose the balls in such a way that the smallest radius is larger than the largest distance to C.

Second, we recall an example from Yavicoli’s [Reference Yavicoli39], which considers the singleton set

![]() $\{0\}\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

. Intuitively, the thickness of a singleton point should be

$\{0\}\subset \mathbb {R}^d$

. Intuitively, the thickness of a singleton point should be

![]() $0$

. However, if we took the nested system of balls

$0$

. However, if we took the nested system of balls

![]() $\{S_{I_n}\}=\left \{\bar {B}\left ( 0,\frac {1}{n}\right )\right \}_{n\geq 1}$

, then

$\{S_{I_n}\}=\left \{\bar {B}\left ( 0,\frac {1}{n}\right )\right \}_{n\geq 1}$

, then

$$ \begin{align*}\tau\left( \{0\},\{S_{I_n}\}\right) &=\inf_{n\geq1}\inf_{\ell(I)=n} \frac{\min_i \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}}(S_{I,i})}{\max_{x\in S_I}\operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,C)} \\ &= \inf_{n\geq1} \frac{1/(n+1)}{1/n} = \frac{1}{2}.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\tau\left( \{0\},\{S_{I_n}\}\right) &=\inf_{n\geq1}\inf_{\ell(I)=n} \frac{\min_i \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}}(S_{I,i})}{\max_{x\in S_I}\operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,C)} \\ &= \inf_{n\geq1} \frac{1/(n+1)}{1/n} = \frac{1}{2}.\end{align*} $$

Including the assumption that our compact sets be r-uniform, defined below, minimizes the frequency of such examples. This condition is similar to the condition that Biebler [Reference Biebler3] needed to ensure that dynamical Cantor sets were “well-balanced,” which prevents compact sets from having artificially large thickness and forces the points of the compact set to be spread out “uniformly.” Please note that this uniformity is not a requirement for the one-dimensional Gap Lemma; e.g., consider the middle-third Cantor set.

Definition 3.3 (r-uniformity, [Reference Yavicoli40])

Given

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

a system of balls for a compact set C, we say that

$\{S_I\}_I$

a system of balls for a compact set C, we say that

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

is r-uniformly dense if for every word I, for every ball

$\{S_I\}_I$

is r-uniformly dense if for every word I, for every ball

![]() $B\subseteq S_I$

with

$B\subseteq S_I$

with

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(B)\geq r\,\operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(S_I)$

, there is a child

$\operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(B)\geq r\,\operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(S_I)$

, there is a child

![]() $S_{I,i}\subset B$

. We say a compact set C is r-uniformly dense if such a system exists.

$S_{I,i}\subset B$

. We say a compact set C is r-uniformly dense if such a system exists.

We now introduce the higher-dimensional Gap Lemma which will be a key tool used in Section 5.

Theorem 3.2 (Gap Lemma, [Reference Yavicoli40])

Let

![]() $C^1$

and

$C^1$

and

![]() $C^2$

be two compact sets in

$C^2$

be two compact sets in

![]() $(\mathbb {R}^d,\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}})$

, generated by systems of balls

$(\mathbb {R}^d,\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}})$

, generated by systems of balls

![]() $\{S_I^1\}_I$

and

$\{S_I^1\}_I$

and

![]() $\{S_L^2\}_L$

, respectively, and fix

$\{S_L^2\}_L$

, respectively, and fix

![]() $r\in \left (0,\frac {1}{2}\right )$

. Assume:

$r\in \left (0,\frac {1}{2}\right )$

. Assume:

-

(1)

$\tau \left ( C^1,\{S_I^1\}_I\right )\tau \left ( C^2,\{S_L^2\}_L\right ) \geq \frac {1}{(1-2r)^2},$

$\tau \left ( C^1,\{S_I^1\}_I\right )\tau \left ( C^2,\{S_L^2\}_L\right ) \geq \frac {1}{(1-2r)^2},$

-

(2)

$C^1\cap (1-2r)\cdot S_\emptyset ^2\neq \emptyset $

,

$C^1\cap (1-2r)\cdot S_\emptyset ^2\neq \emptyset $

, -

(3)

$\operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(S_\emptyset ^1)\geq r\, \operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(S_\emptyset ^2)$

,

$\operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(S_\emptyset ^1)\geq r\, \operatorname {\mathrm {rad}}(S_\emptyset ^2)$

, -

(4)

$\{S_I^1\}_I$

and

$\{S_I^1\}_I$

and

$\{S_L^2\}_L$

are r-uniformly dense.

$\{S_L^2\}_L$

are r-uniformly dense.

Then,

![]() $C^1\cap C^2 \neq \emptyset $

.

$C^1\cap C^2 \neq \emptyset $

.

Remark 3.3 While there are other higher-dimensional notions of thickness, see, for instance, [Reference Biebler3, Reference Falconer and Yavicoli11], we choose to use Yavicoli’s higher-dimensional notion of thickness as it is simpler to construct subsets A, B of C with thickness comparable to C.

3.1 Computing the thickness of a subset

We now consider how to compute the thickness of a subset of C given the thickness of C.

Let C be a compact set with a system of balls

![]() $\{S_I\}_I$

, and let

$\{S_I\}_I$

, and let

![]() $A:= S_{1_A}\cap C$

for some

$A:= S_{1_A}\cap C$

for some

![]() $1\leq 1_A\leq k_\emptyset $

be a compact set with a system of balls

$1\leq 1_A\leq k_\emptyset $

be a compact set with a system of balls

![]() $\{S_{1_A,I}\}_I$

.

$\{S_{1_A,I}\}_I$

.

While the definition of

![]() $h_I(C):=\max _{x\in S_I} \operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,C)$

is used in calculating the thickness of C, when we consider the thickness of first generation subsets of the form

$h_I(C):=\max _{x\in S_I} \operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,C)$

is used in calculating the thickness of C, when we consider the thickness of first generation subsets of the form

![]() $A=C \cap S_{1_A}$

for some

$A=C \cap S_{1_A}$

for some

![]() $1_A$

satisfying

$1_A$

satisfying

![]() $1\leq 1_A\leq k_\emptyset $

, we need

$1\leq 1_A\leq k_\emptyset $

, we need

![]() $h_{1_A}(A):=\max _{x\in S_{1_A,I}}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,A)$

to calculate the thickness of A:

$h_{1_A}(A):=\max _{x\in S_{1_A,I}}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,A)$

to calculate the thickness of A:

$$ \begin{align*} \tau\left( A,\{S_{1_A,I}\}_I\right):=\inf_{n\in\mathbb{N}_0}\inf_{\ell(I)=n}\frac{\min_i \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}}(S_{1_A,I,i})}{\max_{x\in S_{1_A,I}}\operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,A)}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \tau\left( A,\{S_{1_A,I}\}_I\right):=\inf_{n\in\mathbb{N}_0}\inf_{\ell(I)=n}\frac{\min_i \operatorname{\mathrm{rad}}(S_{1_A,I,i})}{\max_{x\in S_{1_A,I}}\operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,A)}. \end{align*} $$

In the proof of Theorem 2.8, we have implicit assumptions about

![]() $\max _{x\in S_I}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,C)$

but no assumptions about

$\max _{x\in S_I}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,C)$

but no assumptions about

![]() $\max _{x\in S_{1_A,I}}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,A)$

, so we use

$\max _{x\in S_{1_A,I}}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,A)$

, so we use

![]() $\max _{x\in S_{1_A}}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,C)$

to get an upper bound on

$\max _{x\in S_{1_A}}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,C)$

to get an upper bound on

![]() $\max _{x\in S_{1_A}}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,A)$

in Lemma 3.4. As in (3.2), define

$\max _{x\in S_{1_A}}\operatorname {\mathrm {dist}}(x,A)$

in Lemma 3.4. As in (3.2), define

$$ \begin{align} h_\emptyset(C) := \max_{x\in S_\emptyset} \operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,C) \quad \text{and} \quad h_{1_A}(A) &:= \max_{x\in S_{1_A}} \operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,A) \nonumber\\ &= \max_{x\in S_{1_A}} \operatorname{\mathrm{dist}}(x,S_{1_A}\cap C). \end{align} $$