Introduction

Non-profit organizations face the critical challenge of attracting and retaining talent—individuals who choose to work with them despite typically low wages and a lack of other incentives, such as job security, that the government sector may offer. Given this, an important academic and practitioner question is: what factors motivate job seekers to prefer positions in non-profits compared to governmental organizations? Extant literature highlights the role of intrinsic motivation in driving job seekers towards non-profits (Reference Becchetti, Castriota and DepedriBecchetti et al., 2010, Reference Becchetti, Castriota and Tortia2013; Reference Borzaga and TortiaBorzaga & Tortia, 2006). However, we have limited knowledge of why some individuals are motivated to work in sectors that help alleviate others' pain but are low paying (Reference Borzaga and TortiaBorzaga & Tortia, 2004; Reference Borzaga, Depedri and TortiaBorzaga et al., 2014). We present a brief literature review regarding the drivers of preferences towards non-profits versus government jobs in Table 1.

Table 1 Review of literature table

References |

Objective |

Theory |

Dependent variable |

Factors affecting choice |

Sample |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ng and McGinnis Johnson (Reference Ng and McGinnis Johnson2020) |

Identify determinants of choice between public and private sector |

Public sector motivation |

The choice between non-profits and private sector organizations |

Education debt |

Developed country |

Education debt diminishes the impact of public sector motivation on the choice of working for non-profits |

Li and Horta (Reference Li and Horta2022) |

Pursuing jobs in non-profits versus public sector organizations |

Public service motivation |

Preference for non-profits over government job |

How personal attributes and motivations affect choice |

Developed market |

Individuals concerned with the political landscape prefer to work for non-profits over government jobs |

McGinnis Johnson and Ng (Reference McGinnis Johnson and Ng2016) |

Determining job switching intentions of those working in non-profits |

Two-Factor hygiene-motivation |

Sector-switching intentions among millennial, non-profit workers |

Compensation and perceptions of equitable pay |

Developed market |

Pay influences sector-switching intentions |

Knapp et al. (Reference Knapp, Smith and Sprinkle2017) |

To determine the turnover intention of non-profit employees |

Job characteristics and perceived organizational support |

The turnover intention of non-profit employees |

Perceived organizational support and skill variety, task identity, and significance |

Developed market |

Perceived organizational support reduces turnover intention |

Piatak (Reference Piatak2017) |

To determine if non-profit sector employees have more sector switching intention than private sector employees |

Donative labor |

Sector switching intention |

Employment in public, private, and non-profit sectors |

Developed Market |

Non-profit employees are less likely to switch sectors during stable economic conditions |

Ballart and Rico (Reference Ballart and Rico2018) |

Determinants of student career choice |

Not a public sector motivation |

The choice between non-profits and the public sector |

Compassion, self-sacrifice, and public sector motivation |

Developed market |

Compassion and self-sacrifice increased preference for non-profits |

Suh (Reference Suh2018) |

Sector switching intention among public sector employees |

Job satisfaction |

Intrinsic versus extrinsic rewards |

Job satisfaction, job match |

Developed market |

Intrinsic job rewards, especially job reputation, increase the preference of public sector employees towards non-profits |

To recruit and retain a workforce effectively, non-profits need to understand the values that make working for them meaningful for job seekers. While extrinsic motivations are paramount for some, this is not universal. A 2015 survey found that 28% of US citizens did not value money or status in their career preferences (Imperative, 2015). A global survey of LinkedIn users suggested that purpose was more important than money for 23% of Saudi Arabians and 53% of Swedish citizens (Reference Hurst, Pearce, Erickson, Parish, Vesty, Schnidman and PavelaHurst et al., 2016). These findings show that the drivers behind career choice may vary from country to country. In emerging markets like India, non-profits’ recruitment of staff may be particularly problematic, given Indians’ preference for jobs in government organizations, owing to the job security they offer in a resource-scant and poverty-stricken country (Reference BoukamchaBoukamcha, 2022).

Despite the growing importance of non-profits, several gaps in the literature exist. First, studies exploring jobseekers’ career preferences or sector attractiveness for non-profits over the government sector have primarily relied on motivation theory or organizational characteristics (Reference Clerkin and CoggburnClerkin & Coggburn, 2012). However, while individuals’ intrinsic values motivate them to pursue a task, the current literature does not explain the underlying attributes that steer them toward non-profits rather than governmental employment. Accordingly, it is not known whether individuals’ prosocial traits—such as spiritualism or religiosity—influence their career preferences for working for non-profits (Reference Saroglou, Pargament, Exline and JonesSaroglou, 2013).

Second, studies that explore jobseekers’ preferences for working for non-profits do not shine a light on how Human Resource Management (HRM) practices, such as opportunities for helping others, influence an individual's career and sector preferences. Extant studies explored how HRM practices influence employee behavior at the workplace, such as green HRM training enhancing sustainability practices or high commitment HRM practices influencing employee job attitude (Reference Innocenti, Pilati and PelusoInnocenti et al., 2011; Reference Usman, Rofcanin, Ali, Ogbonnaya and BabalolaUsman et al., 2023). However, researchers have not explored their impact on career preferences, but rather focus on person-organizational cultural fit aspects (Reference Guillot-Soulez and SoulezGuillot-Soule & Soulez, 2014).

Third, in emerging economies like India, high levels of poverty and a lack of social security affect jobseekers' concern for job security, financial stability, and post-retirement benefits when making career choices (Reference Akosah-Twumasi, Emeto, Lindsay, Tsey and Malau-AduliAkosah-Twumasi et al., 2018). Since governmental organizations are more likely to offer these benefits (Reference Bloom, Mahal, Rosenberg and SevillaBloom et al., 2010), job seekers’ career preferences are toward such organizations. Sectors with minimal job security, pay benefits, or career growth opportunities are less likely to be preferred by job seekers (Reference Rao-Nicholson and MohyuddinRao-Nicholson & Mohyuddin, 2023).

Employees of non-profits often suffer from precarious employment and are suspicious of HR systems (Reference BaluchBaluch, 2017). However, studies exploring jobseekers' drivers to choose non-profits over governmental organizations in emerging markets are lacking. Exploring the drivers behind this choice is vital in countries like India, where government jobs are widely considered as ideal (Reference VasavadaVasavada, 2012).

The importance of non-profit organizations, also known as the third sector, for fulfilling community objectives is continuing to increase (Reference WangWang, 2022). Specifically, these organizations contribute to the economy and help realize the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (Reference BhandariBhandari, 2022). Therefore, evaluating the individual traits that motivate jobseekers to apply for positions in non-profits is critical for a better understanding as to how to improve non-profits’ recruitment practices, which affect their performance and, in turn, their contribution to realizing sustainable development goals.

Fourth, although researchers have explored the effect of workplace spirituality, defined as spirituality driven by organizational values, on employee job outcomes (Reference Baskar and IndradeviBaskar & Indradevi, 2023), little attention has been given to how an individual's spirituality and associated religiosity influence their career and sector preferences and the underlying mechanisms by which spirituality and religiosity influence career choices. Human resource managers should understand not only job candidates’ person-organization and person-job fit, but also their personal values and career choice fit (Reference Chan and HeddenChan & Hedden, 2023). Understanding the latter is critical because, for effective recruitment and retention of employees, job seekers should choose not only a value-congruent organization but also a congruent profession or career.

Our paper has two objectives in relation to these gaps in the extant HRM literature. First, to explain how individuals’ spiritual intelligence and religiosity drive their career preferences and sector attractiveness, especially the appeal of non-profits versus the governmental sector. Second, to identify mediating mechanisms that lead jobseekers to prefer to work in non-profits rather than the governmental sector.

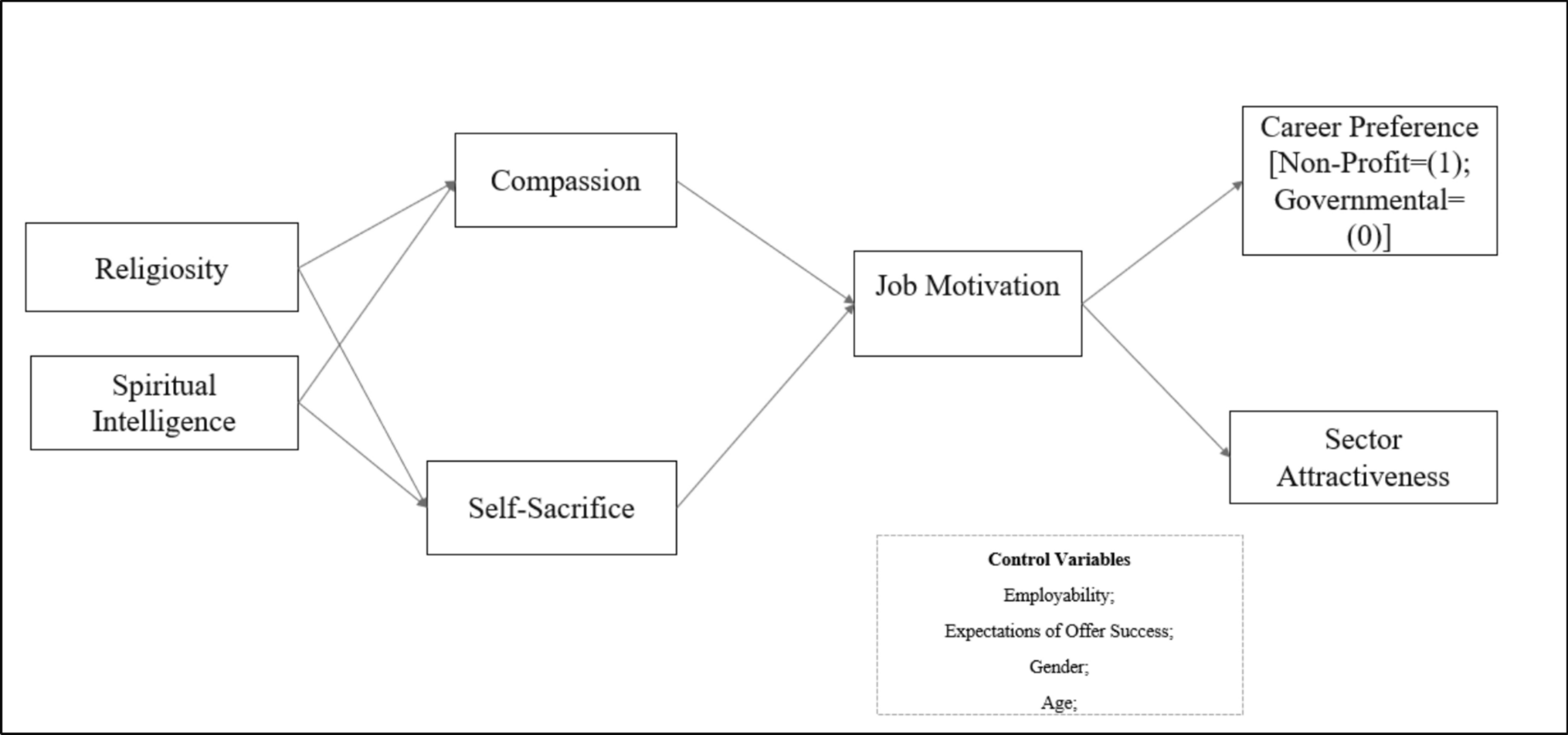

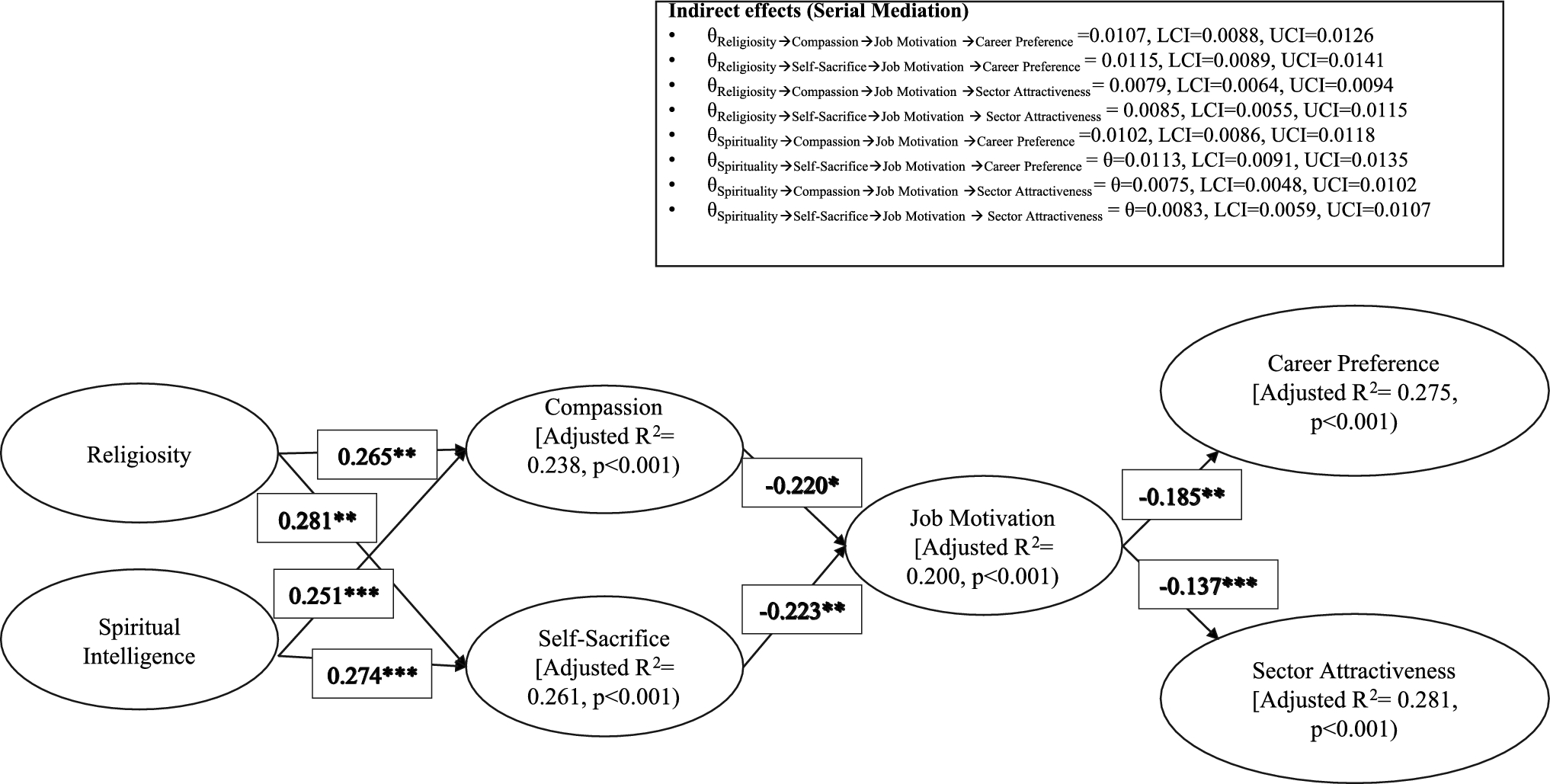

In this study, leveraging personal development and self-determination theories (Reference Davis, Day, Lindia, Lemke, EB, Worthington and SchnitkerDavis et al., 2023; Reference Ryan and DeciRyan & Deci, 2018), we theorize that spiritual and religious individuals are more likely to prefer working for non-profits over governmental organizations. This preference occurs because religious and spiritual individuals possess stronger traits of self-sacrifice and compassion that motivate them to take a job that offers more non-material incentives than material incentives, leading to a preference for working in non-profits over governmental organizations. This implies that compassion and self-sacrifice mediate the effects of spiritual intelligence and religiosity on job motivation; while job motivation mediates the effect of self-sacrifice and compassion on career preference and sector attractiveness. Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework.

Fig. 1 Conceptual framework

We contribute to the HRM literature in several ways. First, we explain the role of spiritual intelligence and religiosity in driving job-seeking decisions, building on the extant research that primarily examines the role of spirituality in influencing employees’ commitment to an organization (Reference Kalantarkousheh, Sharghi, Soleimani and RamezaniKalantarkousheh et al., 2014). By examining the role of spirituality and religiosity in attracting potential applicants to the non-profit sector, we thus contribute to HRM literature regarding the factors that affect recruitment.

Second, extant research explored individuals’ career choices between non-profits and the governmental sector based on motivational factors (Reference McGinnis Johnson and NgMcGinnis Johnson & Ng, 2016; Reference Winter and JacksonWinter & Jackson, 2016). However, we know less about how the inherent traits of spirituality and religiosity affect compassion and self-sacrifice, and their effect on job motivation (Reference Young and BerlanYoung & Berlan, 2021). While the extant HRM literature recognizes the importance of prosocial traits, this is more from the perspective of voluntary giving, philanthropy, or donation rather than employment (Reference Hsieh, Weng, Pham and YiHsieh et al., 2022).

Third, the underlying mechanism that motivates individuals to seek employment in non-profits over governmental organizations remains unclear. We explore the serial mediating role of compassion and self-sacrifice that drives job motivation, thereby extending the HRM literature to identify how prosocial attributes contribute to selecting a career in non-profits (Reference Haar and RocheHaar & Roche, 2010).

Finally, HRM researchers have mainly conducted studies in the context of developed markets, while evidence from emerging markets like India is lacking (Reference Cordes and VogelCordes & Vogel, 2022; Reference LeRoux and FeeneyLeRoux & Feeney, 2013). Institutional voids and a risk-averse environment distinguish India and many other emerging economies from developed countries (Reference Khanna and PalepuKhanna & Palepu, 2000). Given India's importance on the global stage, where several international non-profits are working toward eliminating poverty, understanding Indians’ job preferences is a significant challenge (Reference JansonsJansons, 2015).

Governmental Sector in Emerging Markets

Extant research suggests that individuals with high public service motivation forgo financial rewards to pursue intrinsic work satisfaction when working for non-profit organizations (Reference Georgellis, Iossa and TabvumaGeorgellis et al., 2011). Globally, the government and voluntary sectors tend to pay less than the private sector for comparable qualifications, but offer greater opportunities to contribute to society (Reference Lee and SabharwalLee & Sabharwal, 2016). However, economic realities are harsher in emerging markets: universal social security benefits often do not exist, unlike in most developed markets. The main advantage of working in the governmental sector is job security, which grants a steady income (Reference Kim and KelloughKim & Kellough, 2014). Government jobs also bring less risk of becoming unemployed, given the complex legal procedures that must be followed to remove a person from their job (Reference DongDong, 2017). Government employment in India also offers benefits equivalent to social security through pensions and health care (Reference Saha, Roy and KarSaha et al., 2014). Given the benefits of joining the governmental sector, such as consistent income, retirement benefits, job security, and the opportunity to serve society, employment in this sector is typically very attractive to job seekers. However, in emerging markets, the governmental sector faces the challenge of non-transparent practices, such as bribery. Bribes and informal payments may be substantial in some countries (Reference Olken and PandeOlken & Pande, 2012).

The Non-profit Sector in Emerging Markets

Certo and Miller (Reference Certo and Miller2008) define non-profits as organizations aimed at “the fulfillment of basic and longstanding needs such as providing food, water, shelter, education, and medical services to those members of society who are in need” (p. 267). Non-profits use their business sense in a non-commercial manner to better serve underserved and marginalized segments of society that are incapable of helping themselves (Reference Peredo and McLeanPeredo & McLean, 2006). Non-profits are typically funded via government sources, grants, and donors; however, these revenue sources can be unstable, so employment in non-profits is typically more precarious than in the governmental sector (Reference Burde, Rosenfeld and SheafferBurde et al., 2017). Nonetheless, non-profits are potent actors in eradicating poverty (Reference Ghauri, Tasavori and ZaefarianGhauri et al., 2014), empowering women (Reference Datta and GaileyDatta & Gailey, 2012), aiding those at the bottom of the pyramid (Reference Azmat, Ferdous and CouchmanAzmat et al., 2015), and fostering institutional change – important and urgent tasks in emerging markets (Reference NichollsNicholls, 2008).

In this paper, we first present a brief literature review, followed by the development of hypotheses. After explaining the data and methods, we present the discussion and conclusion and highlight this study's theoretical contributions and managerial implications.

Theory and Hypothesis Development

Self-determination Theory

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) explains how intrinsic motivations affect individuals’ choices. SDT argues that intrinsic motivation is driven by individuals’ psychological needs for autonomy (‘acting with a sense of volition and choice’), competence (‘feeling effective in one's interactions with the social environment’), and relatedness (‘belongingness to groups, communities, or organizations’) (Reference Deci, Ryan, Deci and RyanDeci & Ryan, 2002, p. 7).

For spiritual and religious individuals, autonomy involves performing societal duties voluntarily and not in response to extrinsic motivations such as financial incentives (Reference Kuvaas, Buch, Weibel, Dysvik and NerstadKuvaas et al., 2017). As such, individuals derive satisfaction from serving society; their intrinsic motivation aligns with working for non-profits with a similar mission. By attracting spiritual and religious individuals, non-profits should also generate feelings of belonging among such individuals (Reference Gans-Morse, Kalgin, Klimenko, Vorobyev and YakovlevGans-Mors et al., 2021).

By helping society through working with non-profit organizations, spiritual and religious individuals draw a sense of belonging from communities and non-profits. However, this sense of belonging is less likely occur from working in the governmental sector, given that bureaucratic procedures do not drive spiritual and religious individuals. Corrupt bureaucracy may create more hindrances, resulting in dissatisfaction and alienation (Reference Ahmad, Kaliannan and MutumAhmad et al., 2023). Overall, SDT suggests that spiritual and religious employees will be driven towards working in non-profits due to their intrinsic job motivation; they enjoy the work and identify with the job goals. Thus, rewards such as job security, better pay, and financial stability—the perks governmental organizations offer—may be less relevant to spiritual and religious individuals.

Religiosity

Religiosity is a belief in God and a commitment to the rules and principles that individuals believe God has set out for them (Reference McDaniel and BurnettMcDaniel & Burnett, 1990). All religions encourage giving, and Lama (Reference Lama2007) suggests that “the development of human society is based entirely on people helping each other.” In Christianity, church attendance doubles an individual's willingness to volunteer and donate (Reference LeBaron, Kelley, Hill and GalbraithLeBaron et al., 2021).

Religious individuals believe they have a debt they need to pay back to God by helping others and volunteering for social welfare work (Reference EinolfEinolf, 2011). Religious people will likely express gratitude to God and derive satisfaction from this (Reference Krause and HaywardKrause & Hayward, 2015). One way to do this is by following religious teachings that encourage service to society through self-sacrifice and compassion for others (Reference Saroglou, Pichon, Trompette, Verschueren and DernelleSaroglou et al., 2005). Compassion refers to concern for the suffering and misfortune of others and mitigate the pain others suffer (Reference Dutton, Worline, Frost and LiliusDutton et al., 2006). Self-sacrificing implies putting the needs and interests of others above self-goals and interests. Religious teachings also advocate engagement in volunteering and acting generously to others, thus self-sacrificing certain comforts of life to help fellow human beings in need (Reference Stirrat and PerrettStirrat & Perrett, 2012).

Congregations learn about the meanings of sacred texts delivered through readings and sermons in religious services. Listening to and understanding these texts helps individuals understand the value of helpful behavior (Reference Sosis and AlcortaSosis & Alcorta, 2003). Attendees better understand religious principles, which may activate self-sacrificing and compassionate tendencies towards underprivileged members of society. Studies suggest that collective participation in rituals like religious meetings strengthens the tendency to be compassionate towards the needs of others and be self-sacrificing to serve others (Reference Dollahite, Layton, Bahr, Walker and ThatcherDollahite et al., 2009; Reference Van Cappellen, Toth-Gauthier, Saroglou and FredricksonVan Cappellen et al., 2016). Being aware of the compassionate needs of others to become closer to God will likely motivate spiritual and religious individuals to serve others.

Overall, as religions preach that individuals should be compassionate and sacrifice their self-interest, religious beliefs are likely to drive religious individuals to be compassionate towards others and consider the interests of others, thus becoming self-sacrificing. Hence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

The religiosity of job seekers is positively associated with (a) compassion and (b) self-sacrifice.

Spiritual Intelligence

Spiritual intelligence is the ability of individuals “to access higher meanings, values, abiding purposes, and unconscious aspects of the self and to embed these meanings, values, and purposes in living a richer and more creative life” (Reference ZoharZohar, 2005, p. 46). In the context of employment, according to Duchon (2000), spirituality refers to “the recognition that employees have an inner life that nourishes and is nourished by meaningful work that takes place in the context of community” (p. 137). Spirituality has three key traits: 1) the meaningfulness and purposefulness of work, implying that spiritually intelligent people take jobs that serve a transcendental purpose; 2) belonging to the community; and (3) congruence and self-identification with organizational goals, values, and missions (Reference Bayighomog and AraslıBayighomog & Arasli, 2019).

Spiritual intelligence is distinct from religiosity. Astin et al. (Reference Astin, Astin and Lindholm2011) suggest that religiousness involves adherence to faith-based beliefs (and practices), involving participation in ceremonies and rituals related to the nature of an entity that is believed to have created the world. Spirituality, in contrast, is more about the inner, reflective life and affective experiences, a sense of who we are as individuals, the purpose of life, and the nature of meaningful work (Ciulla, Reference Ciulla, Yeoman, Bailey, Madden and Thompson2019). Understanding and responding to others’ sufferings is a critical source of meaningful work for spiritually intelligent people (Reference Thompson, Harris and BordereThompson, 2016).

Furthermore, it is not only important to respond to the sufferings and pains of others, but it is also critical that this response is prioritized above meeting one's own needs, i.e., sacrificing personal interests to help alleviate the pain of others (Reference Thompson, Harris and BordereThompson, 2016). However, these personal needs are generally material interests. It is not difficult for spiritually intelligent beings to give up material interests as they draw satisfaction from non-material rewards, pursuing acts that provide a sense of meaning, purpose, and direction to their life. Thus, spiritually intelligent beings tend to be more self-sacrificing and compassionate.

Spiritually intelligent individuals believe in the introspection of the mind and spirit and the importance of human relationships within society (Reference VaughanVaughan, 2002). As they navigate relationships, they realize that by alleviating the pain of others, they can benefit society, which is likely to give them deep satisfaction at multiple levels of consciousness (Reference VaughanVaughan, 2002). Thus, to achieve this innate satisfaction of living a richer and more meaningful life, spiritually intelligent people regard the interests of others as paramount, thus becoming more self-sacrificing and compassionate. This implies that as spiritual intelligence enhances an individual's tendency to search for a true purpose in life, it increases their compassion and sacrificing tendencies to put others’ interests before themselves.

To summarize, spiritual intelligence enhances individuals’ compassion and self-sacrificing for others, so that they can derive more meaning from their work by serving the interests of others. Compassion and a self-sacrificing attitude foster greater awareness of the needs of others, and this awareness makes spiritual individuals respond to the needs of others (Reference Saslow, John, Piff, Willer, Wong, Impett, Kogan, Antonenko, Clark, Feinberg, Keltner and SaturnSaslow et al., 2013). Hence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

The spiritual intelligence of jobseekers is positively associated with (a) compassion and (b) self-sacrifice.

Impact of Compassion and Self-sacrifice on Job Motivation

Individuals who sacrifice their own interests and are compassionate towards the needs of others when making career choices are less likely to be motivated by material incentives provided by jobs such as promotions and higher pay (Reference Scheffer, Cameron and InzlichtScheffer & Cameron, 2022). Spiritually intelligent and religious individuals, owing to their self-sacrificing and compassion for others, while pursuing jobs, are more motivated by non-material rewards such as the ability to volunteer to help others. They derive satisfaction from alleviating the pain of others and thus seek true meaning and significance of life and better connect with God.

Spiritual and religious individuals are also not motivated by jobs offering retirement benefits. Individuals high on spiritual intelligence and religiosity, owing to willingness for self-sacrifice and compassion for others, experience a sense of meaning and purpose through continuous service to society rather than retirement in older age (Reference Dang and ZhangDang & Zhang, 2022). They do not believe in having material wealth support and believe in sharing their material wealth with others rather than possessing retirement benefits for self-interest.

Moreover, self-sacrifice and compassion increase religious and spiritual individuals' perceived self-worth, lessen anxiety about old age, and increase hope about future life (Reference Zahedi Bidgol, Tagharrobi, Sooki and SharifiZahedi Bidgol et al., 2020). Finally, owing to self-sacrifice and compassion, religious and spiritually intelligent individuals will have less inclination and motivation for stable and safe jobs if they do not offer enriching opportunities for enhancing societal welfare. Overall, the compassion and self-sacrifice of religious and spiritual individuals drives them to seek jobs that offer opportunities for selfless engagement rather than material incentives (Reference CarbonnierCarbonnier, 2015). Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Jobseekers’ employment motivation is influenced by (a) compassion and (b) self-sacrifice.

Job Motivation and Career Preference and Sector Attractiveness for Non-profit versus Governmental Sectors

Generally, individuals prefer a career aligned with their intrinsic motivational values (Reference Niessen, Weseler and KostovaNiessen et al., 2016). For example, individuals motivated by compassion for others, self-sacrificing their own material interests, are less likely to be incentivized by jobs that offer extrinsic motivational benefits such as higher salaries and job security than intrinsic motivational rewards such as the satisfaction they gain from helping others. This intrinsic motivation, where salary is not a motivational factor, will likely benefit non-profits that offer typically lower wages than the governmental sector. Governmental rules and regulations prohibit non-profits from distributing net earnings to members, officers, or trustees. This constraint deprives non-profits from offering superior extrinsic incentives, such as higher salaries and auxiliary benefits, to employees (Reference CalabreseCalabrese, 2012).

Unlike governmental sector organizations, non-profits are usually founded by individuals or small groups based on their interests in a particular social mission (Reference Bromley and MeyerBromley & Meyer, 2017). Non-profits historically have evolved in response to voices from the margins that identified the limitations of government services (Reference YoungYoung, 2000). Moreover, well-funded government organizations will likely offer extrinsic benefits to employments such as opportunities for career advancement, higher salary, pension plans, and family-friendly policies. In contrast, non-profit organizations will likely offer intrinsic motivational rewards such as enriching, job responsibilities and the ability to contribute positively to society. Accordingly, individuals prefer working for non-profit organizations when intrinsic motivation drives their job motivation. In contrast, when extrinsic rewards drive job motivation, they will likely be interested more in working for government organizations.

Empirical evidence suggests that non-profit employees are more likely than government employees to draw satisfaction from helping others through volunteerism, thus making a difference in people's lives (Reference Rotolo and WilsonRotolo & Wilson, 2006). Survey evidence from Light (Reference Light2002) reported that 60% of non-profit employees regarded their primary motivation to work being satisfaction derived from the ability to help others, compared to 30% of government employees with the same response. Hence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4

Jobseekers’ job motivation determines (a) career preference and (b) sector attractiveness between non-profits and the governmental sector.

Self-sacrifice, Compassion and Job Motivation as Serial Mediators

Extant literature suggests that spirituality and religiosity positively influence employee job-related outcomes such as job performance (Reference Moon, Youn, Hur and KimMoon et al., 2020). However, we propose that spirituality and religiosity are related to career selection outcomes through the mediating effect of the personal traits of compassion and self-sacrifice as parallel mediators and job motivation as a serial mediator. The logic of the serial mediation effect of personal traits and job motivation on the relationships between employees’ spirituality and religiosity and career choice is based on self-determination theory (Reference Deci, Olafsen and RyanDeci et al., 2017).

Religious and spiritually intelligent employees searching for meaning in life and developing a close connection with God become more compassionate towards others. They are willing to sacrifice personal material goals to take action to mitigate the sorrow and misery of others (Reference EmmonsEmmons, 2003). SDT, which motivates individuals to seek jobs that offer superior intrinsic than extrinsic rewards, guides job seeking behavior for spiritually intelligent and religious individuals (Reference Hashmi, Shu, Haider, Khalid and MunirHashmi et al., 2021). Given traits in compassion and self-sacrifice, such individuals are likely to be motivated by jobs that offer strong intrinsic rewards, achieved by alleviating the sorrows and the plight of others rather than extrinsic rewards such as opportunities for growth, pay, and job stability. Thus, spirituality and religiosity drive individuals to become more compassionate and self-sacrificing as they search for the true meaning of life and connection with God.

Compassion and self-sacrifice traits, in turn, motivate spiritual and religious employees to take jobs where material rewards, such as high pay or scope of professional growth, are limited but non-material rewards, such as satisfaction from helping others, are ample (Reference Liu, Tang and ZhuLiu et al., 2008). Since the non-profit sector offers greater intrinsic rewards through ample opportunities to help others, compared to government organizations, spiritual and religious individuals' internalized values of compassion and self-sacrifice are likely to motivate individuals to take a job whose core attribute is based on helping others. Moreover, individuals who seek work in non-profits are less likely to be concerned about wages or market-based pay rates as tangible incentives for their jobs (Reference Murnighan, Kim and MetzgerMurnighan et al., 1993). Overall, spiritual and religious individuals, owing to self-sacrifice and compassion for others, are more likely to be motivated by job aspects that allow them to benefit society, i.e., through the non-profit sector. Hence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5a

The relation between spirituality and (a) career preference and (b) sector attractiveness between the governmental vs. non-profit sector is parallel mediated by compassion and self-sacrifice and sequentially mediated by job motivation.

Hypothesis 5b

The relation between religiosity and (a) career preference and (b) sector attractiveness between the governmental vs non-profit sector is parallel mediated by compassion and self-sacrifice and sequentially mediated by job motivation.

Data and methods

In this study, we test and validate a serial mediation relationship between individuals' spirituality and religiosity (i.e., predictors) and career preference (i.e., a preference for working for non-profits versus the governmental sector) and sectoral attractiveness (i.e., outcome variables). Specifically, individuals' compassion and self-sacrifice are parallel mediators between individuals' spirituality and religiosity and job motivation. Job motivation mediates the relationships between compassion and self-sacrifice and career preference and sectoral attractiveness.

We surveyed jobseekers in India who were active in the job market. We obtained a list of email addresses for these individuals from a job placement agency with offices across India. First, we emailed invitations to participate in the study to 2,977 individuals, explaining the objective and assuring complete anonymity; approximately 42% agreed to participate. Next, we sent the individuals who had accepted the invitation another email with a link to the questionnaire, and the respondents were again assured complete anonymity. A filter question was asked: “Which of the following employment sectors would you most prefer to work in?” The response categories were “governmental sector (public, state, or local),” “non-profit sector,” and “private sector.” If an individual responded “private sector,” the questionnaire was terminated (Reference BrightBright, 2016).

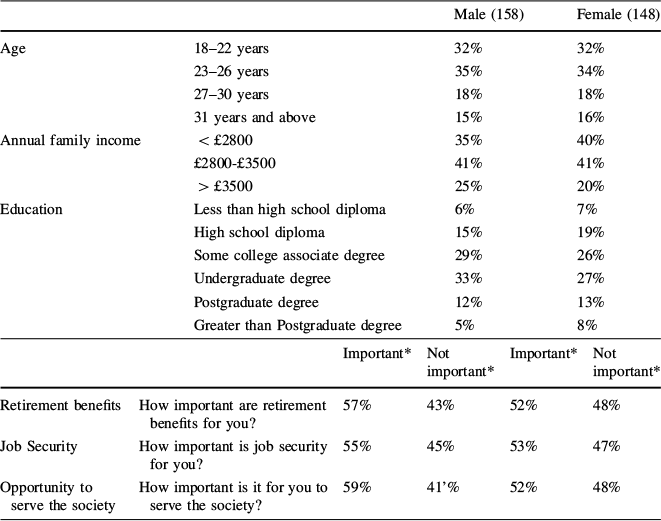

Over two months, we received responses from 338 individuals (female = 163). The response rate of 27% was comparable to the response rate of previous studies (e.g., Bright [Reference Bright2016] reported a 26% response rate). Our final sample size after removing incomplete questionnaires was 306 (female = 148). The sample was representative of the population of India, where the male-to-female ratio in 2020 was 108.18:100. The sample's median age (28.6 years) and mean annual family income (£2954.30) were also representative of the Indian population. Table 2 profiles the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 2 Demography of the sample (N = 306)

Male (158) |

Female (148) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

Age |

18–22 years |

32% |

32% |

23–26 years |

35% |

34% |

|

27–30 years |

18% |

18% |

|

31 years and above |

15% |

16% |

|

Annual family income |

< £2800 |

35% |

40% |

£2800-£3500 |

41% |

41% |

|

> £3500 |

25% |

20% |

|

Education |

Less than high school diploma |

6% |

7% |

High school diploma |

15% |

19% |

|

Some college associate degree |

29% |

26% |

|

Undergraduate degree |

33% |

27% |

|

Postgraduate degree |

12% |

13% |

|

Greater than Postgraduate degree |

5% |

8% |

Important* |

Not important* |

Important* |

Not important* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Retirement benefits |

How important are retirement benefits for you? |

57% |

43% |

52% |

48% |

Job Security |

How important is job security for you? |

55% |

45% |

53% |

47% |

Opportunity to serve the society |

How important is it for you to serve the society? |

59% |

41'% |

52% |

48% |

*A five-point likert scale was “1” being not at all important to “5” being very important.”

Common Method Bias and Social Desirability Bias

Studies employing single-survey questionnaires suffer from common method bias. Following Podsakoff et al.'s (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003) guidelines, we employed the following steps to check and control for this. First, the respondents were assured complete anonymity. Second, the order of the questions was randomized. Third, employing a single-factor model revealed a very poor fit (chi-square/df = 10.29, RMSEA = 0.440, SRMR = 0.216, CFI = 0.591, TLI = 0.508), providing evidence that common method bias had a minimal influence on the study variables. Fourth, we placed several filler questions in the questionnaire to achieve psychological separation and a marker variable, as recommended by Lindell and Whitney (Reference Lindell and Whitney2001) and Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The seven-item social capital investment scale (Reference Chen, Wang, Wegner, Gong, Fang and KaljeeChen et al., 2015) provided the marker variables. These steps and the outcomes suggest that common method bias was not an issue in this study.

Next, we checked for the influence of social desirability bias (Reference De VellisDe Vellis, 1991; Reference Richins and DawsonRichins & Dawson, 1992). First, we employed Crowne and Marlowe's (Reference Crowne and Marlowe1960) 10-item social desirability scale. Sample scale items were: “I'm always willing to admit to when I make a mistake” and “I always pay attention to the way I dress.” The study participants responded to each scale item on a “True” or “False” dichotomous scale. Our analysis revealed that calculated social desirability, sector attractiveness, and career preference correlations were weak and insignificant. These findings indicate that social desirability did not significantly influence career choice and sector attractiveness responses.

Measures

Dependent Variable

The dependent variables are career preference and sector attractiveness. We collected the respondents’ career preferences by asking, “Which of the following employment sectors would you most prefer to work in?” The response categories were “governmental sector (public, state, or local)” and “non-profit sector” (Reference BrightBright, 2016). We coded preference for a government job as 0 and preference for a non-profit job as 1. In our sample, 56% of respondents preferred a government job, with the remainder preferring to work in a non-profit.

We adapt Highhouse et al.'s (Reference Highhouse, Lievens and Sinar2003) 15-item scale to measure sector attractiveness, a higher-order construct of three dimensions: general attractiveness, intentions to pursue, and prestige. Sample items include: “For me, the non-profit sector compared to the governmental sector would be a good place to work,” and “I would accept a job offer in the non-profit sector compared to governmental sector.” We measured each scale item using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The Cronbach's alpha of the three dimensions was between 0.83 and 0.88.

Independent Variables

The independent variables are religiosity and spiritual intelligence. We measured these by adapting the approach of Wilkes et al. (Reference Wilkes, Burnett and Howell1986), who used four items to assess an individual's religiosity: “church attendance,” the “importance of religious values,” “confidence in religious values,” and “self-perceived religiousness.” In India, multiple religions co-exist, so we replaced “church attendance” with “attending religious services.” The first three items based on the Wilkes et al. (Reference Wilkes, Burnett and Howell1986) scale were measured using the statements: “I attend religious services regularly,” “Spiritual values are more important to me than material things,” and “If Indians were more religious, this would be a better country.” These three scale items were measured using a five-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. We measured self-perceived religiousness by asking respondents to evaluate their feelings of religiousness and to characterize themselves as: “Very religious,” “Moderately religious,” “Slightly religious,” “Not at all religious,” or “Anti-religious.” The scale's Cronbach's alpha was 0.82.

Another independent variable is spiritual intelligence. We assessed this using Howden's (Reference Howden1992) 28-item Spirituality Assessment Scale. Sample items included: “I have a general sense of belonging,” “I feel a kinship to other people,” and “I rely on an inner strength in hard times.” All the scale items were rated on a five-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The Cronbach's alpha of the scale was 0.89.

Mediator Variables

The mediator variables of the study were self-sacrifice, compassion, and job motivation. We measured self-sacrifice and compassion using Perry's (Reference Perry1996) Public Service Motivation (PSM) scale. In the 21-item PSM scale, Peery (Reference Perry1996) measured self-sacrifice and compassion constructs using 16 items, eight corresponding to self-sacrifice and eight to compassion. Sample self-sacrifice items include: “Making a difference in society means more to me than personal achievements” and “I feel people should give back to society more than they get from it.” Sample compassion items include: “I am rarely moved by the plight of the underprivileged [reverse coded]” and “Most social programs are too vital to do without.” We measured each scale item using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The internal consistency reliability of the self-sacrifice and compassion scales were 0.85 and 0.84, respectively.

We assessed job motivation using Lee and Wilkins (Reference Lee and Wilkins2011) seven-item scale. Here respondents rated the importance of varying factors in making decisions on taking a job, such as “Opportunity for advancement within the organization's hierarchy,” “Salary,” “The organization's pension or retirement plan,” “Desire for increased responsibility,” ““Family-friendly” policies,” “Ability to serve the public and the public interest,” and “Volunteering.” We measured each scale item using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The internal consistency reliability of the scale was 0.81.

Control Variables

Since extant research identifies that demographic characteristics influence career preferences (Reference LeRoux and FeeneyLeRoux & Feeney, 2013), we controlled for gender and age. Specifically, extant research has found women to be associated more with a preference for working with nonprofits (Reference LeeLee, 2014). Similarly, older people are significantly associated with nonprofits (Reference Wei, Donthu and BernhardtWei et al., 2012). We dummy-coded gender, with men coded “0” and women coded “1.” Age was measured as the natural logarithm of the number of years since birth.

We also controlled for employability and expectation of offer success, given that ideal’ and ‘realistic’ jobseeker preferences between governmental and non-profit organizations may diverge, depending on if the respondent believes that they have skills to be employed and are likely to get a job offer (Reference Lotko, Razgale and VilkaLotko et al., 2016; Reference TuluTulu, 2017). We measured employability using eight items of the 16-item scale of Rothwell and Arnold (Reference Rothwell and Arnold2007). Sample employability items include: “I have good prospects in the non-profit sector compared to the governmental sector because non-profit sector employers will value my personal contribution,” and “Even if there was downsizing in a non-profit sector employer, I am confident that I would be retained.” The Cronbach's alpha of the scale was 0.75.

Finally, we measured expectations of offer success by adapting the single-item scale of Barbulescu and Bidwell (Reference Barbulescu and Bidwell2013). Accordingly, we asked respondents: “Suppose you apply for a job in the non-profit sector compared to a public sector company. How likely is it you get an offer?”.

Results

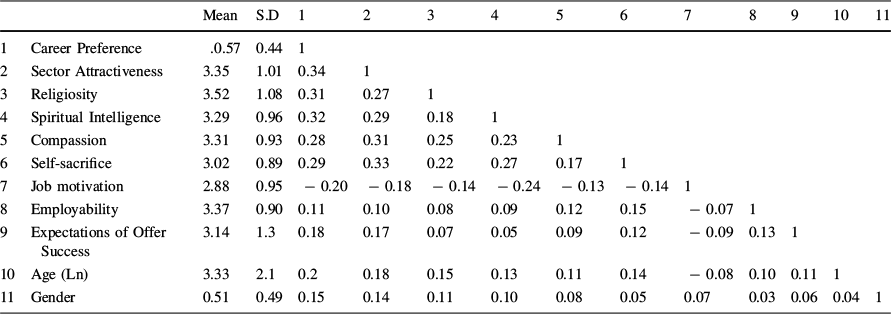

We present descriptive statistics for the variables in Table 3. The correlations of spirituality and religiosity with compassion (rspirituality = 0.23, p < 0.001; rreligiosity = 0.25, p < 0.001) and self-sacrifice (rspirituality = 0.27, p < 0.001; rreligiosity = 0.22, p < 0.001), compassion and self-sacrifice with job motivation (rcompassion = − 0.13, p < 0.05; rself-sacrifice = − 0.14, p < 0.05), and job motivation and career preference (r = − 0.20, p < 0.0001) and sector attractiveness (r = − 0.18, p < 0.01) were positive and significant. These initial results provide preliminary evidence regarding our stated hypotheses.

Table 3 Correlation matrix and descriptive statistics

Mean |

S.D |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Career Preference |

.0.57 |

0.44 |

1 |

||||||||||

2 |

Sector Attractiveness |

3.35 |

1.01 |

0.34 |

1 |

|||||||||

3 |

Religiosity |

3.52 |

1.08 |

0.31 |

0.27 |

1 |

||||||||

4 |

Spiritual Intelligence |

3.29 |

0.96 |

0.32 |

0.29 |

0.18 |

1 |

|||||||

5 |

Compassion |

3.31 |

0.93 |

0.28 |

0.31 |

0.25 |

0.23 |

1 |

||||||

6 |

Self-sacrifice |

3.02 |

0.89 |

0.29 |

0.33 |

0.22 |

0.27 |

0.17 |

1 |

|||||

7 |

Job motivation |

2.88 |

0.95 |

− 0.20 |

− 0.18 |

− 0.14 |

− 0.24 |

− 0.13 |

− 0.14 |

1 |

||||

8 |

Employability |

3.37 |

0.90 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.12 |

0.15 |

− 0.07 |

1 |

|||

9 |

Expectations of Offer Success |

3.14 |

1.3 |

0.18 |

0.17 |

0.07 |

0.05 |

0.09 |

0.12 |

− 0.09 |

0.13 |

1 |

||

10 |

Age (Ln) |

3.33 |

2.1 |

0.2 |

0.18 |

0.15 |

0.13 |

0.11 |

0.14 |

− 0.08 |

0.10 |

0.11 |

1 |

|

11 |

Gender |

0.51 |

0.49 |

0.15 |

0.14 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.04 |

1 |

***r > 0.19p < 0.001; **r = 0.15–0.18p < 0.01, *r = 0.12–0.14p < 0.05; #, r = 0.1–0.11p < 0.10

We also found that the control variables of gender (β = 1.19, p < 0.05) and age (β = 1.08, p < 0.05) have a positive and significant effect on career preference. Specifically, women and older individuals prefer to work for non-profits. Further, gender (β = 1.23, p < 0.05) and age (β = 1.17, p < 0.05) have a positive and significant effect on sector attractiveness.

Estimation Strategy

We used PLS-SEM employing SMARTPLS (Version 4.0) to test the hypotheses. PLS-SEM is suitable for the present study because of the following considerations. Firstly, PLS-SEM is ideally suited to research projects that seek to test theories of construct relationships (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle and Gudergan2017). The present study examines the relationships between religiosity and spirituality and career preference and sector attractiveness, mediated by compassion, self-sacrifice, and job motivation. Second, Richter et al. (Reference Richter, Cepeda-Carrión, Roldán Salgueiro and Ringle2016) and Rigdon (Reference Rigdon2016) argued in favor of PLS-SEM when testing complex models. This is the case with this study, which incorporates both parallel and serial mediation. In addition, sector attractiveness is a second-order construct. Thirdly, extant research in areas closely related to the present study used PLS-SEM to test hypothesized models (e.g., Reference Huang and HsiehHuang & Hsieh, 2011). Finally, the present study also met the minimum sample size criterion of 100 participants. The present study utilizes responses from 306 job seekers. Employing a two-stage approach to PLS-SEM, we first use CFA to evaluate the measurement model and then examine the structural model to test the hypothesized relationships.

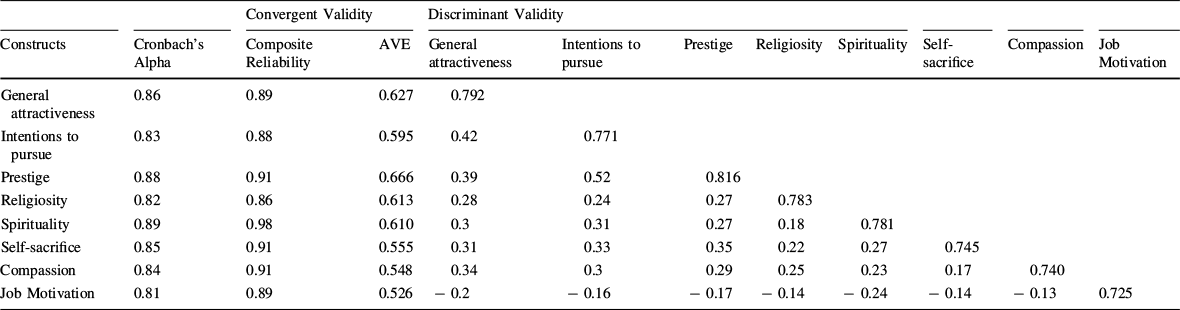

Measurement Model

Table 4 presents the muti-item focal constructs’ reliability and validity. Each item's loading was greater than the recommended cut-off of 0.40. Also, the constructs' internal consistency (i.e., Cronbach's alpha) coefficients ranged between 0.81 and 0.89, greater than the recommended cut-off of 0.60 (Reference Malhotra, Nunan and BirksMalhotra et al., 2017).

Table 4 Reliability and validity statistics

Convergent Validity |

Discriminant Validity |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Constructs |

Cronbach's Alpha |

Composite Reliability |

AVE |

General attractiveness |

Intentions to pursue |

Prestige |

Religiosity |

Spirituality |

Self-sacrifice |

Compassion |

Job Motivation |

General attractiveness |

0.86 |

0.89 |

0.627 |

0.792 |

|||||||

Intentions to pursue |

0.83 |

0.88 |

0.595 |

0.42 |

0.771 |

||||||

Prestige |

0.88 |

0.91 |

0.666 |

0.39 |

0.52 |

0.816 |

|||||

Religiosity |

0.82 |

0.86 |

0.613 |

0.28 |

0.24 |

0.27 |

0.783 |

||||

Spirituality |

0.89 |

0.98 |

0.610 |

0.3 |

0.31 |

0.27 |

0.18 |

0.781 |

|||

Self-sacrifice |

0.85 |

0.91 |

0.555 |

0.31 |

0.33 |

0.35 |

0.22 |

0.27 |

0.745 |

||

Compassion |

0.84 |

0.91 |

0.548 |

0.34 |

0.3 |

0.29 |

0.25 |

0.23 |

0.17 |

0.740 |

|

Job Motivation |

0.81 |

0.89 |

0.526 |

− 0.2 |

− 0.16 |

− 0.17 |

− 0.14 |

− 0.24 |

− 0.14 |

− 0.13 |

0.725 |

Next, we examined the reliability and validity of the focal constructs. The composite reliabilities of the study's constructs ranged between 0.86 and 0.91, indicating construct reliability. Furthermore, the AVE of the constructs ranged between 0.526 and 0.666 and were greater than the cut-off threshold of 0.50 recommended by Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). Thus, the constructs possess convergent validity. Finally, the square root of each AVE was greater than the construct correlations, demonstrating satisfactory discriminant validity.

Structural Model

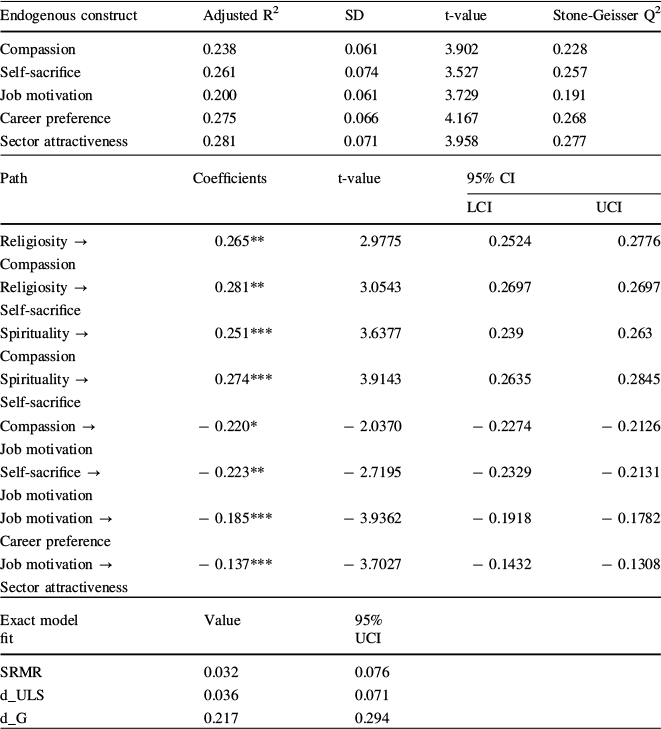

Using SMART PLS, we checked the full model's exact fit. The fit statistics (SRMR = 0.032; d_ULS = 0.036; d_G = 0.217), as reported in Table 5, were less than 0.95 quantiles of the bootstrap discrepancies. Thus, at alpha = 0.05, we had no evidence to reject the model, indicating a good fit. Also, the VIFs ranged between 1.38 and 2.70, indicating that collinearity was not a concern in the present study.

Table 5 Structural model-path coefficients (based on bootstrap = 5000 Re-Sample) (n = 306)

Endogenous construct |

Adjusted R2 |

SD |

t-value |

Stone-Geisser Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Compassion |

0.238 |

0.061 |

3.902 |

0.228 |

Self-sacrifice |

0.261 |

0.074 |

3.527 |

0.257 |

Job motivation |

0.200 |

0.061 |

3.729 |

0.191 |

Career preference |

0.275 |

0.066 |

4.167 |

0.268 |

Sector attractiveness |

0.281 |

0.071 |

3.958 |

0.277 |

Path |

Coefficients |

t-value |

95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

LCI |

UCI |

|||

Religiosity → Compassion |

0.265** |

2.9775 |

0.2524 |

0.2776 |

Religiosity → Self-sacrifice |

0.281** |

3.0543 |

0.2697 |

0.2697 |

Spirituality → Compassion |

0.251*** |

3.6377 |

0.239 |

0.263 |

Spirituality → Self-sacrifice |

0.274*** |

3.9143 |

0.2635 |

0.2845 |

Compassion → Job motivation |

− 0.220* |

− 2.0370 |

− 0.2274 |

− 0.2126 |

Self-sacrifice → Job motivation |

− 0.223** |

− 2.7195 |

− 0.2329 |

− 0.2131 |

Job motivation → Career preference |

− 0.185*** |

− 3.9362 |

− 0.1918 |

− 0.1782 |

Job motivation → Sector attractiveness |

− 0.137*** |

− 3.7027 |

− 0.1432 |

− 0.1308 |

Exact model fit |

Value |

95% UCI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

SRMR |

0.032 |

0.076 |

||

d_ULS |

0.036 |

0.071 |

||

d_G |

0.217 |

0.294 |

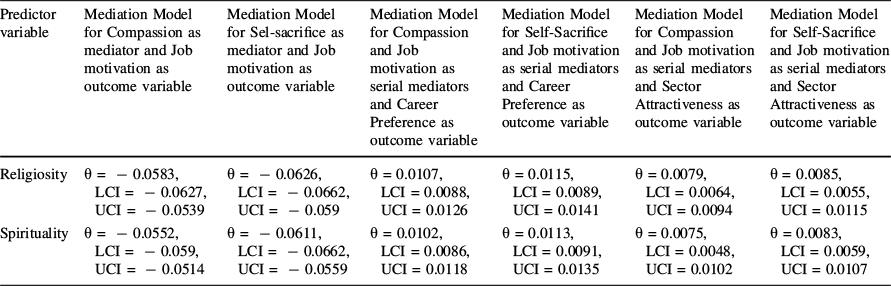

Tables 5 and 6 and Fig. 2 present the mediation analysis. Table 5 reveals that the adjusted R2 and Q 2 values for compassion (adjusted R2 = 0.238, p < 0.001; Q 2 = 0.228), self-sacrifice (adjusted R2 = 0.261, p < 0.001; Q 2 = 0.257), job motivation (adjusted R2 = 0.200, p < 0.001; Q 2 = 0.191), career preference (adjusted R2 = 0.275, p < 0.001; Q 2Finanacial = 0.268) and sector attractiveness (adjusted R2 = 0.281, p < 0.001; Q 2 = 0.277) are greater than the thresholds suggested by Falk and Miller (Reference Falk and Miller1992) of a 10% level of significance and positive, respectively. These statistics indicate the model's predictive relevance.

Table 6 Indirect Effects (n = 306)

Predictor variable |

Mediation Model for Compassion as mediator and Job motivation as outcome variable |

Mediation Model for Sel-sacrifice as mediator and Job motivation as outcome variable |

Mediation Model for Compassion and Job motivation as serial mediators and Career Preference as outcome variable |

Mediation Model for Self-Sacrifice and Job motivation as serial mediators and Career Preference as outcome variable |

Mediation Model for Compassion and Job motivation as serial mediators and Sector Attractiveness as outcome variable |

Mediation Model for Self-Sacrifice and Job motivation as serial mediators and Sector Attractiveness as outcome variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Religiosity |

θ = − 0.0583, LCI = − 0.0627, UCI = − 0.0539 |

θ = − 0.0626, LCI = − 0.0662, UCI = − 0.059 |

θ = 0.0107, LCI = 0.0088, UCI = 0.0126 |

θ = 0.0115, LCI = 0.0089, UCI = 0.0141 |

θ = 0.0079, LCI = 0.0064, UCI = 0.0094 |

θ = 0.0085, LCI = 0.0055, UCI = 0.0115 |

Spirituality |

θ = − 0.0552, LCI = − 0.059, UCI = − 0.0514 |

θ = − 0.0611, LCI = − 0.0662, UCI = − 0.0559 |

θ = 0.0102, LCI = 0.0086, UCI = 0.0118 |

θ = 0.0113, LCI = 0.0091, UCI = 0.0135 |

θ = 0.0075, LCI = 0.0048, UCI = 0.0102 |

θ = 0.0083, LCI = 0.0059, UCI = 0.0107 |

Fig. 2 Structural model

Hypotheses 1 and 2 proposes that an individual's religiosity and spirituality are positively associated with compassion and self-sacrifice. An analysis of the results in Table 5 confirms the assertion of positive and significant relationships of religiosity and spirituality with compassion (β = 0.265, p < 0.01; β = 0.251, p < 0.001) and self-sacrifice (β = 0.281, p < 0.01; β = 0.274, p < 0.001). Thus, the analysis supports the first two hypotheses.

Next, the results in Table 5 reveal that job motivation is negatively and significantly associated with compassion (β = − 0.220, p < 0.05) and self-sacrifice (β = − 0.223, p < 0.01). Job motivation construct comprised questions concerning career growth, financial stability, and promotion opportunities. As can be observed from our theorization, more compassionate individuals are willing to sacrifice personal needs to help others are less likely to be motivated by pay, promotion, and growth, implying a negative relationship with job motivation factors. We, therefore, present evidence in support of the third hypothesis. Further, the indirect effects of individuals’ religiosity and spirituality on job motivation through compassion (θReligisity→Compassion→Job Motivation = − 0.0583, LCI = − 0.0627, UCI = − 0.0539; θSpirituality→Compassion→Job Motivation − 0.0552, LCI = − 0.059, UCI = − 0.0514) and self-sacrifice (θReligisity→Self-sacrifice→Job Motivation = − 0.0626, LCI = − 0.0662, UCI = -0.059; θSpirituality→Self-sacrifice→Job Motivation = − 0.0611, LCI = − 0.0662, UCI = − 0.0559) are statistically significant.

Hypothesis 4 predicts the association between job motivation and the outcome variables: career preference and sector attractiveness. From Table 5, we can see that an individual's job motivation negatively and significantly influences career preference (β = − 0.185, p < 0.001) and sector attractiveness (β = − 0.137, p < 0.001), thereby providing support for the fourth hypothesis. Specifically, the more the job motivating factors of career growth and promotion opportunities, drive an individual, the less likely they are to prefer a career in non-profits over the governmental sector.

Furthermore, the indirect effect of religiosity on career preference (non-profit versus governmental sector) through compassion and job motivation in series was significant (θ = 0.0107, LCI = 0.0088, UCI = 0.0126). Also, the indirect effect of religiosity on career preference (non-profit versus government) through self-sacrifice and job motivation in series was significant (θ = 0.0115, LCI = 0.0089, UCI = 0.0141). We obtain similar results for the indirect effect of religiosity on sector attractiveness through compassion and job motivation in series (θ = 0.0079, LCI = 0.0064, UCI = 0.0094) and the indirect effect of religiosity on sector attractiveness through self-sacrifice and job motivation in series (θ = 0.0085, LCI = 0.0055, UCI = 0.0115).

The indirect effect of spirituality on career preference (non-profit versus government) through compassion and job motivation in series was significant (θ = 0.0102, LCI = 0.0086, UCI = 0.0118). Also, the indirect effect of spirituality on career preference (non-profit versus government) through self-sacrifice and job motivation in series was significant (θ = 0.0113, LCI = 0.0091, UCI = 0.0135). We obtain similar results for the indirect effect of spirituality on sector attractiveness through compassion and job motivation in series (θ = 0.0075, LCI = 0.0048, UCI = 0.0102) and the indirect effect of spirituality on sector attractiveness through self-sacrifice and job motivation in series (θ = 0.0083, LCI = 0.0059, UCI = 0.0107). Overall, the analysis supports all hypotheses. Table 6 presents the indirect effects.

Robustness

As a matter of robustness, we replicated the study with college students (n = 249), including undergraduates (n = 116) and postgraduates (n = 133). Although the beta coefficients of the explanatory variables changed, the overall statistical significance of the results remained unchanged.

We also conducted a study with a sample of employees (n = 223) working in non-profits (n = 104) and the government (n = 119). However, this time our dependent variable changed. For those working in non-profits, we asked, “How likely are you to switch from working in a non-profit to the governmental sector and vice versa?” (Reference McGinnis Johnson and NgMcGinnis Johnson & Ng, 2016). Those high on the explanatory variables spiritual intelligence and religiosity, exhibited a preference for switching from the governmental sector to non-profits and were less likely to switch from non-profits to government jobs.

In a third robustness study with job seekers (n = 201), we adapted Highhouse et al.'s (Reference Highhouse, Lievens and Sinar2003) sector attractiveness scale, evaluating the attractiveness of one sector at a time, i.e., the non-profit sector, compared with the governmental sector. Although the beta coefficients changed, the overall significance of the results remained the same. Individuals high on spiritual intelligence and religiosity reported a positive association with sector attractiveness when the sector was non-profits and a negative association when the sector was governmental.

Discussion

The ability of non-profit organizations to achieve their goals and broader societal objectives depends on their ability to recruit and retain appropriate staff (Reference Garbe and DuberleyGarbe & Duberley, 2021; Reference Walk, Schinnenburg and HandyWalk et al., 2014). Non-profits must compete against other sectors for employees, and globally, HRM has often proved challenging for third-sector organizations. In emerging economies like India, where employment in government organizations is often highly desirable, the challenge is even more acute. Given the unfavorable environment for non-profits in India, we consider the recruitment and retention problems they face by introducing and validating a conceptual framework that explains the factors that motivate job seekers to prefer employment in non-profits.

Drawing on self-determination theory, we explore the role of spiritual intelligence and religiosity. Our findings enhance our understanding of what drives jobseekers to choose non-profits over the government. Specifically, SDT explains the intrinsic job motivational tendencies of spiritual and religious individuals to seek meaningful work through employment in non-profits Our study can help HRM researchers appreciate the significance of spirituality and religiosity, propelling job seekers toward the non-profit sector in emerging markets.

Spiritual and religious employees care about positive social welfare effects and are more likely to prefer non-profits over government organizations. Even in societies where government employment offers better job security and stable working practices (Reference GoldenGolden, 2015), spiritual and religious individuals may still prefer to work for non-profits, as found in our study. Our findings are thus consistent with Miller-Stevens et al. (Reference Miller-Stevens, Taylor and Morris2015), who report differences in the spiritual and religious values of employees working in non-profits and local government.

We found that compassion and self-sacrifice mediate the relationship between spirituality and religiosity and job motivation to work for non-profits over government organizations. Specifically, our findings suggest that more spiritual and religious individuals are more likely to be motivated by a job that yields societal benefits and may prefer to work for non-profits.

Contributions to the Literature

Our study adds to the HRM literature concerning the non-profit sector. First, we explain how the spirituality and religiosity of jobseekers influence job motivating factors, which influence career choice decisions. Likewise, we extend SDT: while extant researchers have applied this to explain how individuals make career choices (Reference Sheldon, Holliday, Titova and BensonSheldon et al., 2020), they do not detail the underlying mechanisms through which job seekers make such decisions.

By exploring the prosocial traits of spiritualism and religiosity, we shine a light on those traits that drive individuals to choose employment in non-profits over the government. Extant literature emphasizes the role of prosocial motivation (Reference Andersen and KjeldsenAndersen & Kjeldsen, 2013) but does not unpack this, considering the influence of spirituality, and religiosity. By hypothesizing and validating the effects of these traits, we contribute to the literature that helps to explain individuals’ job preferences.

The present study addresses the underexplored question as to why do spiritual and religious individuals prefer to work in one sector over another? In addressing this gap, our study suggests that such individuals value the opportunity to contribute to society and are likelier to work in non-profits owing to compassion and a self-sacrificing attitude towards others. Our findings thus expand understanding of the reasons behind the preference of some jobseekers for employment in non-profits over the governmental sector despite the latter's much better material rewards, such as financial stability and pensions (Reference AgrawalAgrawal, 2012).

We also extend the prior literature, which reports mixed results regarding the effect of religiosity on human behavior. Some studies suggest that it has adverse impacts, such as a lack of citizenship behavior (Reference Kutcher, Bragger, Rodriguez-Srednicki and MascoKutcher et al., 2010), while others report positive effects (Reference Zafar, Altaf, Bagram, Hussain, Tabassum Riaz, Nadim and ChaudhryZafar et al., 2012). Studies from faith-based organizations suggest that religious belief helps to motivate spiritual and religious behavior. For instance, Nichols (Reference Nichols1988), studying international humanitarian relief, noted, “It was religious motivation that inspired relief workers to travel halfway around the world and serve their fellow human beings” (p. 234). Our study extends this reasoning, suggesting that religiosity makes spiritual and religious individuals even more interested in working for non-profits because of their greater compassion and willingness to sacrifice personal interests, leading them to prioritize jobs that generate social benefits, rather than the material rewards of career growth, job stability, and other financial incentives.

We also extend the literature on spiritual intelligence and job motivation. Extant studies suggest that spiritual motivation influences job performance at work. Our findings suggest that spirituality also determines work and career preference outcomes. Furthermore, extant literature explores the role of job motivation as a mediator of different outcomes (Reference Moksnes, Løhre, Lillefjell, Byrne and HauganMoksnes et al., 2016; Reference Niwako, Julie and MikaNiwako et al., 2011), but not spiritualism, religiosity, and non-profit versus government choice perspectives.

Finally, we add to the recruitment and retention literature concerning non-profits. Non-profit managers often report that hiring and retaining professional staff is a significant challenge (Reference Gamble, Thorsen and BlackGamble et al., 2019). Extant literature addresses this problem by highlighting internal organizational factors, such as the importance of generating a shared identity (Reference Warburton, Moore and OppenheimerWarburton et al., 2018). Although the role of prosocial traits has been explored in the talent management literature (Reference Merrilees, Miller and YakimovaMerrilees et al., 2020), a holistic framework examining the role of prosocial traits such as spirituality and religiosity and associated parallel and sequential mediating effects has not been previously explored. Studies exploring talent recruitment have relied mainly on qualitative data to address the issue but recognize the need for quantitative evidence (Reference Edeigba and SinghEdeigba & Singh, 2022).

Implications for HRM in Non-profits

Our findings generate actionable insights for human resource managers in non-profits. Our findings suggest that spiritual and religious individuals are more likely to prefer to work for non-profits, so non-profits should target their recruitment efforts toward them. In job vacancy advertisements, non-profits should promote rewards consistent with spirituality and religiosity instead of emphasizing material compensation, which is the usual practice (Reference Shuls and MarantoShuls & Maranto, 2014). This is because material rewards may not motivate spiritual and religious individuals to pursue job vacancies, owing to limited opportunities to exercise compassionate and self-sacrificing traits for alleviating the pain of others. Moreover, spiritual and religious individuals, owing to self-sacrificing and compassion traits, also care less about retirement and pension benefits while selecting a job. Benefits to others are often not presented in job advertisements but are important for recruitment of staff by non-profits.

As spiritual intelligence and religiosity motivates individuals to work for non-profits, the latter may want to reconsider the mechanisms through which they recruit staff. Rather than relying on employment agencies, a common practice, non-profits could consider advertising positions through religious networks, such as church newsletters or spiritual societies.

Considering spiritual intelligence and religiosity traits, our findings suggest that non-profits can enhance their recruitment by targeting spiritual and religious job candidates. Non-profits may identify spirituality and religiosity through personality tests (Reference Hilbig, Glöckner and ZettlerHilbig et al., 2014). Alternatively, organizations may conduct situational interviews to evaluate a candidate's actions in a given situation, and thus indirectly gauge spiritual and religious values (Reference Klehe and LathamKlehe & Latham, 2006).

Furthermore, the descriptive statistics indicate that spirituality, religiosity, and age correlate significantly (i.e., there are statistically significant correlations between age, spirituality, and religiosity), implying that an individual's proclivity toward non-profit work and philanthropic behavior increases with age. Non-profit managers generally focus on hiring recent college graduates (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Huh, Cho and Auh2015), but this may be a mistake. Such managers may benefit from focusing less on those freshly entering the job market. As people age, they are more likely to wish to give back to society, thus developing spiritual and religious tendencies (Reference Sparrow, Swirsky, Kudus and SpaniolSparrow et al., 2021).

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

In this study, we relied on self-reported data, whereby job seekers expressed their preference for employment in a non-profit rather than their actual behavior. Future studies may benefit from going beyond self-reported preferences. Similarly, different types of non-profits, including faith-based and secular ones, serve society differently (Reference FlaniganFlanigan, 2010), so future studies may explore whether religious and spiritual individuals are driven to work more for certain types of non-profits. Future studies could also explore whether prosocial traits enhance job satisfaction among those recruited to and employed in non-profits, whether these factors affect the length of employment or churn, and whether employees are likely to receive better performance appraisals once employed, owing to better job performance.

Furthermore, we conducted our study in one country. Cross-country comparisons could be undertaken to assess whether cultural differences influence individuals’ choice of non-profit versus government jobs. We also explored serial mediators, but multiple parallel mediators may influence spiritual, religious, and career preference and sector attractiveness relationships. Future studies could explore this.

Finally, we considered two intrinsic traits of individuals: spiritual intelligence and religiosity. However, it is possible that macro-environmental contextual pressures also influence this mediated relationship between spirituality, religiosity, and career preference. Consequently, future studies could consider the effect of contextual variables in greater depth.

Data Availability

Due to the nature of the research and ethical reasons, supporting data is unavailable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors confirm that there has been no conflict of interest with any party or organization.