Introduction

It is a defining feature of any liberal and democratic political system that policy reflects the will of the people (see, e.g., Dahl Reference Dahl1956; Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967; Przeworski Reference Przeworski2010). The match between public preferences and public policy cannot be expected to be perfect and instantaneous. In some cases – for example, when it comes to possible infringements of fundamental human rights or the repression of minorities – it might not even be normatively desirable. However, no political system that allows for gross, sustained and systematic differences between what the public wants and what policies the government delivers can be considered liberal and democratic (cf. Rehfeld Reference Rehfeld2009: 214).

Therefore, it is important to assess how strong the link between public opinion and public policy is in order to obtain a comprehensive and nuanced picture of the quality of democracy in Europe. Yet, our knowledge about the link between public opinion and the public policies in place across European democracies is still limited. Previous studies have investigated a large number of countries but along very general dimensions, like left‐right (Powell Reference Powell2006; Golder & Stramski Reference Golder and Stramski2010; Blais & Bodet Reference Blais and Bodet2006; Golder & Lloyd Reference Golder and Lloyd2014; Ferland Reference Ferland2016), government spending (Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012) or broad policy areas (Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008; Soroka & Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). We contribute to this literature with a study of the link between public opinion and policy that simultaneously includes a large number of European countries, uses data on concrete policy outcomes and covers a relatively large number of different policy areas. Specifically, we compare public opinion towards 20 specific policy issues with the status of these policies in 31 European countries in a cross‐sectional design. Instead of relying on aggregate or indirect measures of policy, we determine the actual state of policy for specific policy issues within broader policy domains in each country. This approach has the advantage of not requiring the assumption that citizens’ policy preferences neatly map onto a single dimension, such as left‐right or liberalism (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012), and allows us to measure opinion and policy on the same specific issues (Berry et al. Reference Berry, Portney and Thomson1993; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Wlezien Reference Wlezien2017).

The second aim of this study is to examine whether the opinion‐policy link varies with some of the political institutions that differentiate the political systems found across Europe. It is widely believed that political institutions can fundamentally affect the quality of democratic governance. Yet, in many cases, opposing theoretical expectations exist about the nature and direction of an institution's influence. For instance, electoral systems with proportional representation (PR) rules are more likely to produce multi‐party governments, which can make legislating in line with public opinion difficult (Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009; Coman Reference Coman2015). At the same time, governments in majoritarian systems might not always have the incentives to follow the median voter either (Persson & Tabellini Reference Persson and Tabellini2004; Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008; Milesi‐Ferretti et al. Reference Milesi‐Ferretti, Perotti and Rostagno2002).

Similarly, the horizontal separation of powers embodied in institutions like bicameralism or rules allocating considerable discretion to the executive vis‐à‐vis the legislature may influence the opinion‐policy nexus in contingent ways, which do not make them generally better or worse at producing a strong link between opinion and policy. On the one hand, veto players can act as safeguards to protect the public from policies that only serve a minority (Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012). On the other hand, they can also prevent governments from enacting policies that are congruent with public opinion (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995; Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008). Hence, the provisional conclusion that emerges from the theoretical predictions of the existing literature, as well as the empirical findings, is that institutions can steer policy simultaneously towards and away from public opinion. Therefore, rather than arguing that specific institutions affect congruence in a single direction, we suggest that countries with different institutional set‐ups may exhibit little to no net systematic differences in the strength of the relationship and congruence between opinion and policy. The exception is the vertical separation of powers through multilevel government in federalist systems and European Union member states, where a lower clarity of responsibility might lead to public opinion being less well reflected in policy (Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012).

Our sample of 31 countries features significant variation along this set of institutional dimensions, while the 20 policy issues are of differing salience and from various policy types and areas. This allows us to explore the potential impact of institutions on a diverse set of issues, extending previous research examining the association between institutions and the opinion‐policy link among a small number of countries (Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008), among many countries but with respect to overall government spending (Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012) or at the subnational level (Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012).

We find a strong and statistically significant positive relationship between public support for a policy and the likelihood that the policy is in place. Moreover, in two‐thirds of the cases, we observe that policy is congruent with the opinion of the majority of citizens. Thus, the opinion‐policy link and level of congruence observed in the European countries are not perfect, yet relatively high compared to the American states (cf. Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012). At the same time, we find no association between the two aspects of the opinion‐policy linkage that we study and any of the institutional features we analyse, apart from the number of chambers in parliament. We are led to conclude that the different and often opposing ways in which electoral systems, the horizontal division of powers and the vertical separation of powers can be expected to affect policy representation may cancel out in the aggregate. The study thus contributes with new empirical insights to the debate on the impact of political institutions on the opinion‐policy linkage and the quality of democracy more generally.

The opinion‐policy nexus

Due to the centrality of the link between public opinion and policy to the core concept of representative democracy, a range of studies have used multiple approaches and data sources to examine it. They have investigated how closely public opinion matches different indicators of public policy, such as the degree of policy liberalism, government agendas, budgetary spending or specific policy issues (e.g., Page & Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1983; Erikson et al. Reference Erikson, Wright and McIver1993; Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995; Monroe Reference Monroe1998; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2009, Reference Lax and Phillips2012). The vast majority of research on the opinion‐policy linkage focuses on single or small numbers of countries (e.g., Burstein Reference Burstein2014; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Monogan et al. Reference Monogan, Gray and Lowery2009; Stimson et al. Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Romeijn and Toshkov2018; Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995; Soroka & Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2004) and often uses aggregate indicators of policy (Stimson et al. Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995; Erikson et al. Reference Erikson, Mackuen and Stimson2002) or analyses broad policy areas, such as labour and employment or defence (e.g., Jennings & John Reference Jennings and John2009; Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995; Bevan & Rasmussen Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2017). Recent years have witnessed an increase in the number of studies that take a comparative approach, often investigating the role of political institutions. However, they rely on broader measures of policy than specific policy issues (e.g., Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012; Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008; Kang & Powell Reference Kang and Powell2010) or focus on one policy area, such as immigration or social welfare (e.g., Eichenberg & Stoll Reference Eichenberg and Stoll2003; Brooks & Manza Reference Brooks and Manza2006; Peters & Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2014; Morales et al. Reference Morales, Pilet and Ruedin2015).

The problem with looking at a single policy area is that we might not be able to generalise findings about the opinion‐policy linkage and the impact of political institutions and other cross‐country differences to other policy areas as they may differ for different policy domains and issues of varying salience. Meanwhile, the use of broad policy categories or dimensions does not consider the possibility that the preferences of citizens and political elites’ over specific policies within broader policy areas are not necessarily consistent. In Golder and Ferland's (Reference Golder, Ferland, Herron, Pekkanen and Shugart2017) words, a ‘strong positive correlation between policy adoption and state ideology says little about whether implemented policies are congruent with citizens’ preferences because we do not know how broad measures of state ideology should be translated into preferences for actual policies’ (cf. also Burstein Reference Burstein2014; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012).

Several studies overcome this problem by comparing public opinion with policy change or with existing legislation across a range of specific policy issues. This approach also allows examining how the opinion‐policy linkage varies with issue characteristics. Yet, since these studies have generally been restricted to a single country (cf. Brettschneider Reference Brettschneider1996; Brooks Reference Brooks1987, Reference Brooks1990; Burstein Reference Burstein2014; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Gilens & Page Reference Gilens and Page2014; Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Monroe Reference Monroe1979, Reference Monroe1998; Page & Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1983; Petry & Mendelsohn Reference Petry and Mendelsohn2004),Footnote 1 it is difficult to assess the applicability of their findings in other contexts. In order to simultaneously achieve the aims of making observations that are – to a certain extent – generalisable across both countries and issues, and of avoiding a potential mismatch between public opinion and policy, we examine variation in the opinion‐policy linkage across a large set of specific policy issues and a high number of national contexts.

We focus on two aspects of the opinion‐policy linkage: the relationship between public opinion and policy and congruence between them. The former refers to the idea that changes in public opinion should be reflected in corresponding changes in policy. This relationship is often understood in a dynamic way, with policy being responsive to changes in public opinion (Achen Reference Achen1978). Yet, it is equally possible that a high correlation between opinion and policy exists because citizens have adapted their preferences to information and arguments provided to them by political elites (Esaiasson & Holmberg Reference Esaiasson and Holmberg1996; Holmberg Reference Holmberg, Rosema, Denters and Aarts2011). This conceptual understanding is reflected in our methodological design: By examining the relationship between public opinion and policy measured at the same point in time across countries, we allow the causality between public opinion and policy to flow in both directions. In addition to the relationship between opinion and policy, we study congruence, which indicates whether the policy in place has the support of a majority of the population. Both aspects of policy representation capture important normative intuitions about the concept, are empirically distinct (Achen Reference Achen1978), and need to be analysed separately (Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012).Footnote 2

The impact of political institutions

In addition to assessing the link between opinion and policy in Europe, we are interested in the extent to which, and why, it varies across countries. Political institutions are among the most prominent factors hypothesised to affect the opinion‐policy linkage. The main institutional characteristics assumed to play a role in existing studies are electoral systems and the horizontal and vertical separation of powers in a country (Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012). While several studies have examined the effects of these institutions, they often conduct an analysis of policy responsiveness over time for a set of broader policy areas and in a limited number of countries (Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008; Soroka & Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010; see also Wlezien and Soroka (Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012) and Kang and Powell (Reference Kang and Powell2010) who cover many countries but only one dimension of public spending). In addition, several of the studies interested in assessing the impact of electoral institutions focus on left‐right congruence between citizens and governments rather than on the link between public opinion and policy outputs (e.g., Blais & Bodet Reference Blais and Bodet2006; Ferland Reference Ferland2016; Golder & Stramski Reference Golder and Stramski2010; Golder & Lloyd Reference Golder and Lloyd2014; Powell Reference Powell2009). The expectations and findings of these previous studies vary quite substantially, which is partly due to the different ways in which they conceptualise and measure representation. We adapt the expectations about the effects of institutions on representation to the opinion‐policy link across a set of concrete policy issues in a cross‐national design.

Electoral systems

The impact of electoral institutions on representation has been examined by looking at both ideological congruence and policy responsiveness. In the past, it was widely believed that PR systems generate a better match between public opinion and policy than majoritarian or plurality systems. After all, the system was designed with the aim of achieving a high level of vote‐seat proportionality and, hence, guarantee the representation of as many views in society as possible (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1984). Yet, while earlier studies provided support for this expectation (see Huber & Powell Reference Huber and Powell1994; Powell Reference Powell2000, Reference Powell2006; McDonald et al. Reference McDonald, Mendes and Budge2004), there is now widespread agreement that, through different mechanisms and if certain conditions are met, PR and majoritarian systems generate governments that represent citizens similarly well (Blais & Bodet Reference Blais and Bodet2006; Ferland Reference Ferland2016; Golder & Stramski Reference Golder and Stramski2010; Golder & Lloyd Reference Golder and Lloyd2014; Powell Reference Powell2009; see also Golder & Ferland Reference Golder, Ferland, Herron, Pekkanen and Shugart2017). However, this literature conceptualises and measures representation in terms of congruence between the left‐right positions of citizens and the government rather than between citizens’ policy preferences and policy outputs (cf. Kang & Powell Reference Kang and Powell2010), which may be understood as coming later in the ‘chain’ of representation. While the ideological orientation of the government might be a powerful predictor of legislation, there are additional mechanisms through which electoral system characteristics may influence both the ability and the willingness of governments to change or maintain policy in line with the wishes of the public (cf. Coman Reference Coman2015; Golder & Ferland Reference Golder, Ferland, Herron, Pekkanen and Shugart2017).

An important factor is the policy‐making dynamics of multi‐party governments, which are more likely to emerge in PR systems where higher numbers of parties tend to enter parliament. Government coalitions require compromise (Müller & Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm2000). In such systems, it can be difficult to reach agreement and implement policy that would improve the representation of the public majority but hurt the constituencies of some coalition partners (Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012, Reference Wlezien and Soroka2015). In the words of Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009), coalition governments increase the ‘institutional friction’ that hinders policy change. Coman (Reference Coman2015) illustrates these dynamics with the example of spending cuts that are desired by the overall public but whose burden none of the coalition partners wants their constituencies to bear. But the issue also pertains to other types of policy where the government parties disagree and use their veto powers (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995).

What is more, single‐party governments have a higher clarity of responsibility than multi‐party governments (Fisher & Hobolt Reference Fisher and Hobolt2010; Powell & Whitten Reference Powell and Whitten1993). If citizens can more easily determine which party is to praise or blame for a policy or its absence, and reward or punish it at the next election, government parties have a stronger incentive to bring policy in line with public opinion by adjusting legislation or by convincing the public of their policies. As a result, one might expect policy to reflect public opinion better under majoritarian than PR rules, even if governments represent the median voter equally well in both systems (Coman Reference Coman2015; Golder & Ferland Reference Golder, Ferland, Herron, Pekkanen and Shugart2017). Support for such a prediction can for example be found in Wlezien and Soroka's (Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012) work, which demonstrates that electoral system proportionality has the potential to decrease the strength of the link between spending preferences and actual spending.

Yet, there are also factors that might weaken the opinion‐policy link in majoritarian systems. Since in single‐member district (SMD) systems seat shares are increased by winning pluralities in additional districts rather than gaining additional votes in ‘safe seats’, parties looking for re‐election often have an incentive to please voters in a few pivotal districts rather than the nationwide median voter (Persson & Tabellini Reference Persson and Tabellini2004; Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008). There is also evidence that SMD systems incentivise politicians to cultivate a personal rather than a party vote, resulting in representatives catering to the more narrow interest of their districts rather than those of the national public (Milesi‐Ferretti et al. Reference Milesi‐Ferretti, Perotti and Rostagno2002).Footnote 3 In line with such a view, Hobolt and Klemmensen (Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2005) found that the government's policy intentions were less responsive to public opinion in the British plurality system than in the Danish proportional system.

We are thus faced with different and partly opposing arguments for why majoritarian or PR systems might foster stronger opinion‐policy linkages, and it is not entirely clear which side in the debate assembles more powerful mechanisms. This leaves the option that, in the aggregate, we may find no net differences in the strength of the opinion‐policy linkage between the different electoral systems.

Horizontal division of powers

Similar counteracting pressures are likely to exist with regard to the horizontal division of power between the executive and the legislative branches of government. It may be easier to adopt policy that reflects public opinion in systems where the legislature is more powerful. Legislatures in parliamentary systems face fewer constraints when passing laws desired by the public than those in (semi‐)presidential systems, in which checks and balances are generally stronger (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995). Using a similar argument, Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009) posit that the requirement that laws enjoy the support of both president and parliament may be another source of friction hampering the adoption of policy. Particularly – though not exclusively – in cases where the presidency and the parliament are controlled by different parties, presidential and semi‐presidential systems can experience gridlock (Monroe Reference Monroe1998). In fact, even parliamentary systems display variation in the division of powers between legislative and executive (as a result of, for instance, differences in the government's ability to influence the legislative agenda and the degree of parliamentary scrutiny), which may lead to differences in the opinion‐policy link.

However, a strong horizontal division of powers may not only affect the opinion‐policy linkage in a negative manner. Similarly to veto players within government coalitions, requirements to obtain executive‐legislative agreement can affect positively the opinion‐policy linkage by blocking policy changes that are not desired by the public (cf. Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008). For example, Wlezien and Soroka (Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012) find that weaker executive discretion strengthens the link between the public's spending preferences and actual spending. Hobolt and Klemmensen (Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008) provide a similar explanation for their finding of high responsiveness in the United States. Whether a stronger horizontal division of power weakens or strengthens the opinion‐policy link in a specific case thus likely depends on whether the public desires a policy change or favours the status quo. With such counteracting pressures, there might thus be no net effect of the horizontal distribution of power on the opinion‐policy linkage.

A similar argument applies to bicameral and unicameral systems: an upper chamber with (strong) veto powers can generate ‘friction’ and thwart policy change that is in the interest of the public (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009), but it can also prevent unpopular decisions – especially if the two chambers are controlled by different parties (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995). Again, whether a more extensive division of powers is beneficial for stimulating a strong linkage between opinion and policy is thus contingent on situational factors, providing the possibility that we find no net differences in the strength of the opinion‐policy link between the different systems.

Vertical division of powers

In complex systems of multilevel governance it should be more difficult for voters to assign responsibility for policy as it is often unclear which government level deals with a particular issue (see also Jones et al. Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009). This lowers the pressure on governments to respond to the public's wishes as they are less likely to be punished for it (Soroka & Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2004; Wlezien & Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012). The opinion‐policy link at the national level might thus be weaker in countries with federal systems. Similarly, the representation of public opinion in national policy that is not affected by EU legislation is likely to be lower in countries that are members of the EU, since the division of competences between the EU and the national level is not always clear‐cut. The blurring of responsibilities may thus act as a strain on responsiveness not only in EU policy making itself (Alexandrova et al. Reference Alexandrova, Rasmussen and Toshkov2016) but also in the spheres of national policy making analysed here. As a result, it can be expected that the opinion‐policy linkage is weaker in countries which have a federal, as opposed to a unitary, system and in countries that are members of the EU.

Data and method

In order to investigate the link between public opinion and policy, we collected public opinion data and mapped policy for 20 policy issues in 31 European countries.Footnote 4 Our unit of analysis is a policy in a country. Since we aimed at analysing the same policy issues across countries, we systematically screened a set of cross‐national public opinion surveys conducted among representative samples in at least 15 European countries, such as the Eurobarometer, European Social Survey and European Election Study, to single out questions about respondents’ preferences concerning specific policy issues. We selected 20 items in the period between 1998 and 2013 that cover a broad range of different policy areas, including, among others, economic, health, defence and retirement policy, and which met our selection criteria. These criteria included, among others, that an item referred to a specific policy issue rather than a broad policy area (e.g., smoking bans in bars and pubs rather than health policy; military involvement in Afghanistan rather than defence policy) with national competence, that the response scale indicated respondents’ agreement or disagreement, and that it was possible to determine whether the policy was in place when the survey was conducted (i.e., questions asking about preferences for future changes in policy were excluded).Footnote 5 The 20 policy issues, together with the year, the survey and the number of countries in which the item was asked, are listed in the Appendix at the end of the article.

Although the set of policies covers a diverse range of policy areas, it does not constitute a random sample from the universe of policy issues. This universe is extremely difficult to define, and so far Burstein's (Reference Burstein2014) is the only study of public opinion and policy that attempts it. Yet, while Burstein's interpretation of the set of all bills introduced in Congress as the universe of potential policies may be valid in the United States, it is not easily transferrable to the European context. In many European countries, governments have traditionally initiated the majority of laws and these proposals often have a high chance of being adopted (Andeweg & Nijzink Reference Andeweg, Nijzink and Döring1995). Thus, information about potential policies with low chances of adoption is difficult to acquire. Furthermore, it would be virtually impossible to obtain public opinion data on a randomly selected sample of policy issues for a large number of countries. Selecting policy issues based on their availability in surveys is thus the best viable method for the moment for a cross‐national study as ours.

While there is certainly a risk that the results obtained on the basis of our sample cannot be generalised to other policy issues, this risk should be relatively low for several reasons. First, the issues cover a range of policy areas. Second, they vary strongly in salience, which has been shown to be an important predictor of the opinion‐policy link (Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Monroe Reference Monroe1998; Page & Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1983). Third, it is unlikely that the sample is biased due to an underlying logic that guides the inclusion of items in the surveys, as we rely on many different surveys. Moreover, this point is more relevant with respect to national surveys, where the selection of questions may be driven by current policy debates. While this may be the case for some of our policies, such as military involvement in Afghanistan, it is unlikely to be the case for many of them.Footnote 6

Measuring policy and public opinion

After selecting the policy issues, we mapped the state of public policy in the countries included at the time when the survey was conducted. Information was obtained from relevant documents issued by government agencies, international organisations, nongovernmental organisations, news outlets and academics. We first coded the policy status for each issue into an ordinal scale with the number of levels reflecting the potential variation in policy. These scales were then transformed into a harmonised scale with three levels, where 0 indicates that the policy was not in place, 1 that it was partly in place and 2 that it was fully in place. As an example, the scale for the smoking ban in bars and pubs reflects the differences in smoking regulation across Europe: 0 = no ban, 1 = partial ban with many or some exceptions (e.g., for small premises or smoking rooms) and 2 = complete ban.

This ordinal measure of policy is used as the dependent variable in the analysis of the relationship between degrees of policy and public support. To analyse whether an increase in public support for a policy is related to a higher probability of the policy being in place, the policy measure is regressed on a variable that indicates the proportion of respondents in a country who were in favour of the policy among those who indicated a preference in favour or against it.Footnote 7 In order to test the hypothesised effects on the relationship between public opinion and policy, we interact public opinion with the respective variable.

In a second step, we investigate opinion‐policy congruence. This is operationalised as a dummy variable indicating whether policy was in line with the preferences of the majority of the citizens who expressed an opinion. In order to construct this variable, the original ordinal policy scales were collapsed into two categories: ‘policy in place’ or ‘no policy in place’. The policies coded as ‘partly in place’ were recoded as either ‘in place’ or ‘not in place’ depending on the particular issue, as shown in Online Appendix B, which provides information on the original scales and their transformation into the three‐level and binary measures. The resulting congruence variable is dichotomous and takes the value 1 if (a) the policy is in place and the majority of the public is in favour or (b) the policy is not in place and the majority of the public is against it. Descriptive information about policy, public opinion and congruence can be found in Online Appendix C.

Independent variables

The independent variables in our study are a range of indicators of the political institutions whose effects we seek to analyse. In line with Wlezien and Soroka (Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012), we measure the proportionality of the electoral system by using the effective number of parliamentary parties (ENPP), developed by Golder (Reference Golder2010) and extended by Bormann and Golder (Reference Bormann and Golder2013). We use the value from the last national election that took place prior to the year in which the public opinion data was collected.Footnote 8 Next, we use two alternative measures of the executive‐legislative balance. The first is a set of three regime type dummies indicating whether a country has a presidential, semi‐presidential or parliamentary system (Cheibub et al. Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010).Footnote 9 We also use a more nuanced index of the legislature's influence over the executive, drawn from the Parliamentary Powers Index (Fish & Kroenig Reference Fish and Kroenig2009). Its components are seven dimensions of the national legislature's power – for instance, whether it can by itself impeach the president or replace the prime minister. It ranges from 0 to 9, with higher values indicating stronger influence. Our third measure of the horizontal division of powers is a dummy indicating whether a legislature is unicameral or has two chambers.

Finally, we measure the vertical division of powers with two variables: the first indicates whether a country was a member of the European Union when public opinion and policy were measured and the second whether the country was unitary or federal or had a hybrid structure in which some central government powers were delegated to the regional level. The sources of all variables and each country's values are listed in Online Appendix D.

Moreover, we control for the media salience of an issue, since the existing literature provides evidence that it strengthens the link between opinion and policy (e.g., Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012). If a policy issue is salient in the public debate, and particularly in the news media, the public will have access to more information in order to form policy preferences. In turn, political decision makers will receive more information about public opinion on salient issues on which they can base their decisions. The heightened visibility of and public attentiveness to policy makers’ (in‐)actions on these issues may also increase the pressure on them to be responsive or to convince the public of their policies (cf., e.g., Page & Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1983). We measure media salience through the proportion of articles in the Financial Times’s coverage of Europe devoted to the policy issue over a three‐year period, ending in the year in which the survey was conducted. Since most issues had very few articles devoted to them while a few were extremely salient (especially nuclear energy), we use the natural logarithm of the measure. The Financial Times certainly does not pay equal attention to the public and political debates in all European countries. However, in light of the difficulty of collecting data on the salience of the specific policy issues within each country, we believe that it constitutes a sufficiently valid proxy of the relative salience of the policy issues across countries. In addition, it can be argued that even if it were possible to measure media coverage of all 20 issues in the 31 European countries, such a measure would be endogenous to policy adoption as issues would be more salient where they were on the government agenda (Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012).Footnote 10

We nevertheless construct an alternative measure to test the robustness of the results. This is an indicator of public rather than media salience and is based on respondents’ answers to the ‘most important problem’ (MIP) question posed by the European Election Study in each country. This measure is problematic, however, in that it links the specific policy issues in our sample to the very broad policy areas into which the responses are categorised. It is thus not a good indicator of the salience of the specific policy issue (e.g., respondents might consider the environment to be an important issue but not specifically whether plastic waste should be banned from landfills). Moreover, it does not indicate the degree of information transmission between the public and policy makers through the media, which is a crucial aspect of the causal mechanisms we proposed. We therefore use the media salience indicator in the models reported but provide details about the construction of the MIP measure and estimates of the models in Online Appendix F.

In the congruence models, we also include a measure of the size of the opinion majority, whether in favour or against the policy (Lax & Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012). It accounts for the expectation that policy is more likely to be line with the majority of the public, the larger the majority. Finally, we include the year in which public opinion and policy were measured in order to control for a potential time trend in the opinion‐policy link as well as the fact that the more recent surveys tend to include more Central and Eastern European countries. All continuous independent variables are grand‐mean centred.

Results

The relationship between opinion and policy in Europe

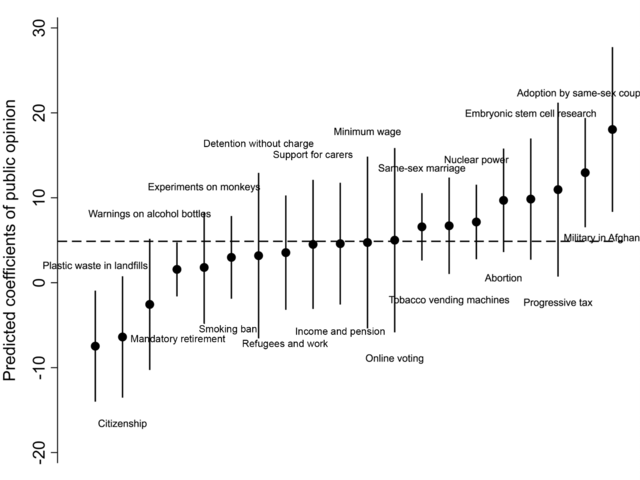

Our cases are clustered within both policy issues and countries. In order to determine whether there are dependencies between the cases within a cluster for which we should account in our models, we first estimated multilevel ordered logit regression models with policy as the dependent variable and public opinion as the only independent variable.Footnote 11 In model 1, Table 1, we report the random variances of the intercept and the slope of public opinion at the level of policy issues. First of all, we find that public support for a policy is statistically significantly associated with the probability of the policy being in place. Second, this relationship varies systematically across policy issues, as the random slope variance suggests. Figure 1 illustrates this variation by showing the predicted coefficients of public opinion on policy for each issue when we allow the slope for public opinion to vary between issues. On some issues, including ‘military in Afghanistan’ and ‘adoption by same‐sex couples’, policy is clearly more strongly related to public opinion than on other issues, such as ‘ban on plastic waste in landfills’, where the relationship is in fact negative. We obtain a significant likelihood‐ratio test comparing the model to an ordered logit regression without the random intercept and slope, which shows that the multilevel model with issues at the higher level has a significantly better fit.

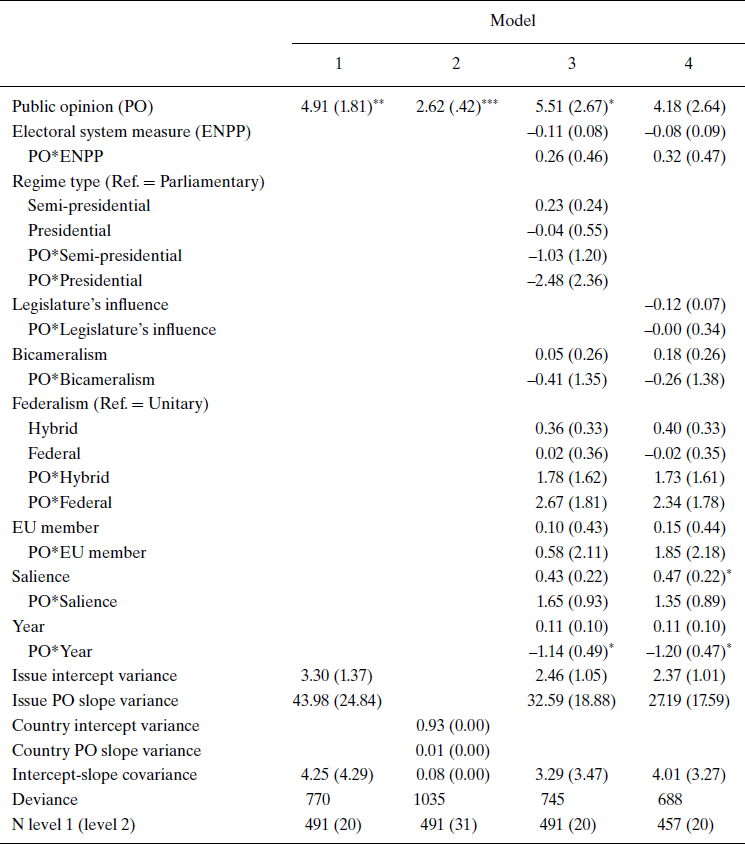

Table 1. Effects on the relationship between public opinion and policy

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 1. Predicted coefficients (log‐odds) of public opinion on the policy being in place for each issue, with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Notes: The dashed line indicates the mean coefficient across all issues. Coefficients are empirical Bayes predictions based on the coefficient of public opinion and its random slope variance in model 1, Table 1.

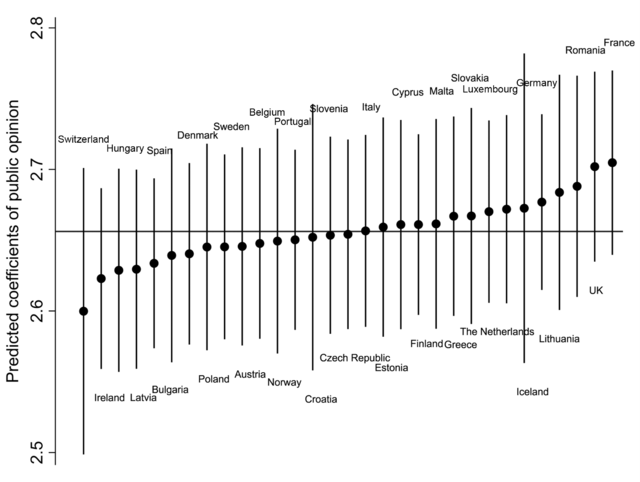

In model 2, we estimate the equivalent model with countries at the higher level and find that the slope variance is close to zero when we allow the relationship between public opinion and policy to vary between countries. This means that, as Figure 2 shows, the predicted coefficients of public opinion on policy are very similar across countries. The likelihood‐ratio test comparing model 2 to the equivalent model without the random variance components is insignificant.Footnote 12 In substantive terms, this means that there seems to be very little variation in the strength of the opinion‐policy linkage across countries.Footnote 13

Figure 2. Predicted coefficients (log‐odds) of public opinion on the policy being in place for each country, with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Notes: The dashed line indicates the mean coefficient. Coefficients are empirical Bayes predictions based on the coefficient of public opinion and its random slope variance in model 2, Table 3.

Despite this observation, we might find that the opinion‐policy relationship varies with political institutions when we control for the other institutions. In model 3, we test this by including interaction terms of each institutional indicator with the public opinion variable. We find that none of the institutions influences the relationship between public opinion and policy. This holds even when only including one indicator at a time (not shown). Only the control measure for the year significantly interacts with public opinion, suggesting that the opinion‐policy link has become weaker over time. This might, however, be due to the expansion of the country sample.

Model 4 is equivalent to model 3 but includes the measure of the legislature's influence instead of the regime type dummies. This variable does not seem to influence the relationship between opinion and policy either.Footnote 14 As a robustness check, we estimated a set of models equivalent to those in Table 1 but with a binary measure of policy (the one used to construct the congruence measure) and a multilevel logit specification. The results do not substantially differ except that the interaction term between public opinion and media salience is positive and significant at p < 0.05.Footnote 15

Explaining public opinion‐policy congruence in Europe

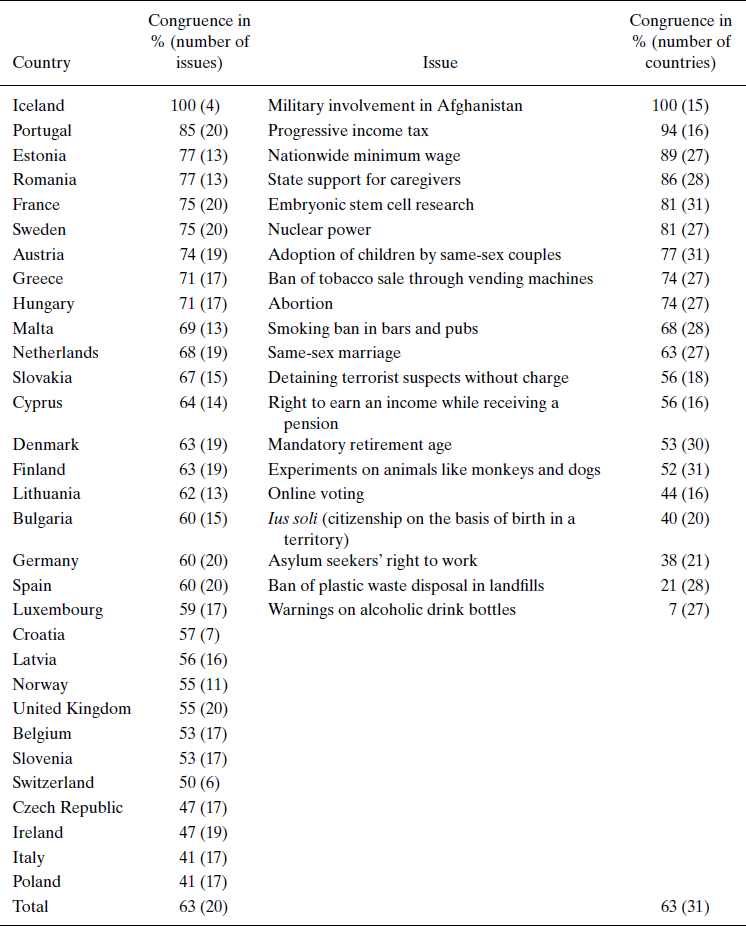

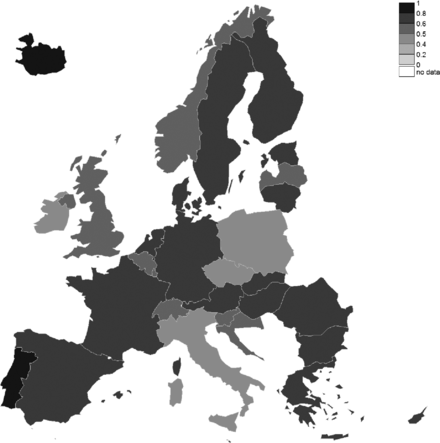

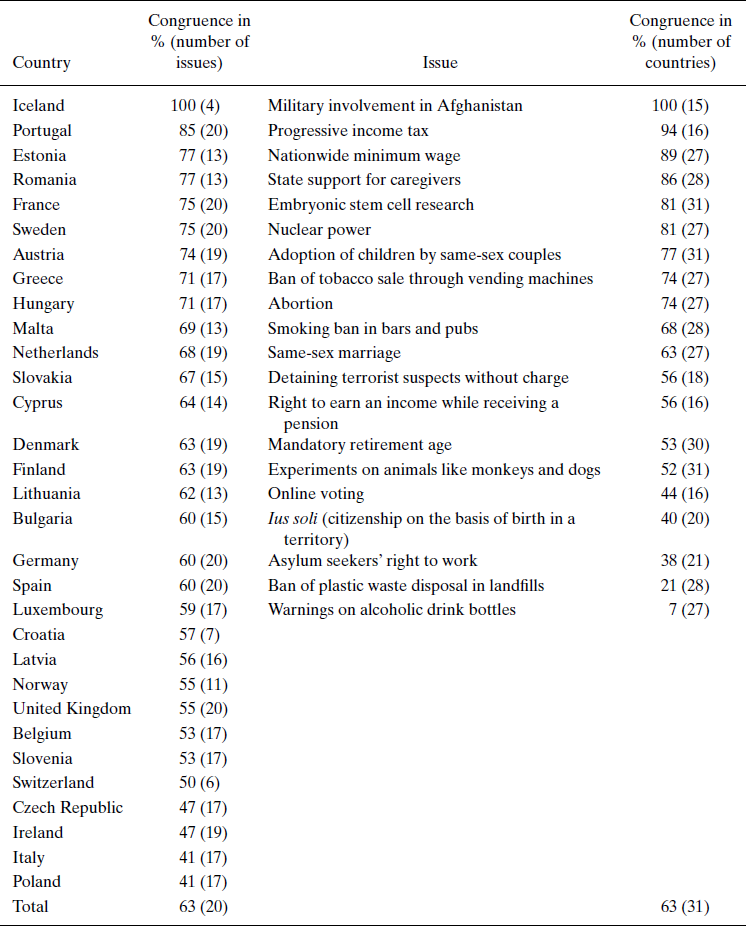

While it is reassuring that the likelihood of having a particular policy rises with public support, this is not a sufficient standard for policy to reflect the views of the citizens. We therefore examine to what extent existing policy is in line with the preferences of the majority and whether political institutions influence it. We find that in the majority (63 per cent) of cases, legislation is in line with the opinion of the majority of citizens (Table 2). A comparable study by Lax and Philips (Reference Lax and Phillips2012) on the American states found congruence only about half of the time. While Table 2 shows that congruence varies across countries (from 41 per cent of issues in Italy and Poland to 100 per cent in Iceland, which is however an outlier and for which we have information on only a small number of issues), the differences across issues are again more striking: in only 7 per cent of countries is the law on warnings on alcohol bottles directed at drivers and pregnant women congruent with public opinion, whereas congruence exists in 100 per cent of the countries for military involvement in Afghanistan. Figure 3 underlines that there are no clear patterns in congruence with regard to the different regions in Europe.

Table 2. Congruence by country and policy issue

Figure 3. Congruence levels across Europe.

Notes: Darker shades indicate higher opinion‐policy congruence (cf. Table 2). The mean level is 63 per cent (Denmark and Finland), the minimum is 41 per cent (Italy and Poland) and the maximum is 100 per cent (Iceland).

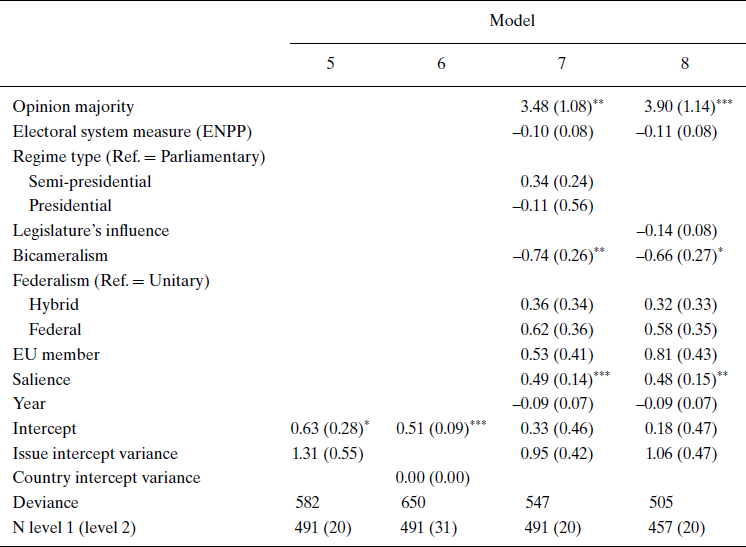

This observation is confirmed by the results of multilevel logistic regression analyses with random intercepts at the levels of issues and countries, respectively (Table 3). While a substantial degree of variation in congruence can be accounted for by policy issues (model 5), a negligible share of it is related to countries (model 6), mirroring our findings in the analysis of the opinion‐policy relationship. Thus, even though there is clearly some degree of variation in congruence across countries, as Table 2 shows, it does not appear to be systematic. It would therefore appear that countries’ institutional configurations have no net impact on whether policy corresponds with the majority opinion. However, in order to test whether individual political institutions affect it we again need to control for the others.

Table 3. Effects on public opinion‐policy congruence

Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

As models 7 and 8 show, none of them do except one: countries with a bicameral system have a lower likelihood of opinion‐policy congruence than countries with only one legislative chamber. This finding suggests that the checks and balances present in bicameral systems might make it more difficult for governments to provide the policies that the public wants. The average predicted probability of congruence (based on model 8), with the covariates at their observed levels, is 69 per cent in unicameral systems, whereas it is only 57 per cent in bicameral systems. We also find that policy is more likely to reflect the opinion of the majority of the public the larger the majority; this corresponds with the finding that the likelihood of policy being enacted (not enacted) is correlated with the degree of support in favour of (against) it. Finally, congruence is more likely the more salient a policy issue is in the news media.Footnote 16

Conclusion

Whereas the quality of democratic governance in Europe and elsewhere has been subject to much criticism, our study finds a positive, large and statistically significant association between public opinion and policy on a range of issues across the European continent. Moreover, in close to two‐thirds of all cases policy is congruent with the majority opinion. Even though democratic politics is about more than the extent to which policies on specific issues reflect the wishes of the public, these results offer reassurance regarding the state of democratic governance in Europe. They indicate that the political institutions and practices in place are able to ensure, one way or another, that public opinion and policy do not deviate too much and too often from one another.

Importantly, we do not find systematic variation across the 31 countries we study in the extent to which policy is correlated with public preferences or in the likelihood of congruence between opinion and policy. In contrast, we find significant differences in policy representation across the 20 policy issues that we study, which are only partly accounted for by the differences in overall media salience between the issues. The low country‐level variation in the opinion‐policy link is intriguing because our sample of countries features both established and relatively young democracies from all corners of the European continent – from Norway to Portugal and from Ireland to Bulgaria. These countries display a lot of variation in terms of political institutions, which are often assumed to have important effects on the opinion‐policy link. Yet, apart from a relationship between the number of legislative chambers and congruence between policy and the majority opinion, we did not find evidence that institutions condition the opinion‐policy linkage.

While there is increasing agreement that different electoral rules can generate high levels of left‐right congruence between the government and the citizens (Golder & Lloyd Reference Golder and Lloyd2014; Blais & Bodet Reference Blais and Bodet2006; Ferland Reference Ferland2016; Powell Reference Powell2009), our results suggest that the policies in place also reflect public opinion to similar degrees in more and less proportional electoral systems. It thus appears that the factors that might obstruct responsive policy making in PR systems, such as the need to bargain, veto points and a low clarity of responsibility in multi‐party governments, are balanced out by incentives to cater to specific constituencies rather than the median voter and other potential factors in majoritarian systems.

Moreover, in systems where the legislature has more power over the executive, this presence of a veto player might hinder policy change that responds to public opinion, but at the same time it can prevent unpopular policies. Whether the public prefers policy change or the status quo might thus be decisive, and on the aggregate these dynamics might cancel each other out. Surprisingly, even the vertical division of powers does not appear to affect the opinion‐policy linkage, although we expected that governments in countries with multilevel structures, and hence a lower clarity of responsibility, would have lower incentives to bring policy and public opinion in line. We thus conclude that policy may be in line with public opinion in a variety of different institutional contexts. Yet, this certainly does not mean that the quality of democracy does not vary across Europe. Even though correspondence between public opinion and policy is an important aspect of representative democracy, it is not sufficient if the procedural aspects of the democratic political process are not respected.

Our results indicate that at any given point of time there might be no net differences in the aggregate opinion‐policy linkage and congruence between countries with different institutions. Hence, while the institutions might have various well‐defined effects, the results of their operation might not be different, on average, in the sample of countries that we have. It should also be acknowledged that institutions that produce year‐to‐year relationships between opinion and policy are not necessarily the same as institutions that co‐occur with concurrent opinion‐policy correspondence analysed in this study. Future research should therefore investigate the causes of the differences in opinion‐policy linkage between issues as well as the patterns and relationships we observed in more detail – for example, by analysing whether and how institutions and issue characteristics influence the different causal links between opinion and policy. Longitudinal research designs and in‐depth case studies searching for direct evidence of policy makers listening to the public and the public adjusting its preferences to policy have great potential to address such questions (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Romeijn and Toshkov2018). Importantly, such work could also consider whether not only individual institutions but also specific configurations of institutions affect the linkage between opinion and policy.

Moreover, it should be recognised that, beyond the difficulty of measuring comparative institutions, it is possible that the mechanisms through which institutional and issue characteristics influence this linkage vary between subsets of countries and issues. For instance, in countries where an institution has become consolidated and exerted its effects over many years, its potential to link opinion and policy might be different than in newly established democracies or countries where institutional changes took place recently. The fact that our sample is inclusive in terms of both issues and countries might also partly explain why our findings differ from those of some previous studies. Wlezien and Soroka (Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012), for instance, who find effects of electoral system proportionality and executive power, include a smaller number of postcommunist countries. It is also possible that because we look further down the policy‐making process than, for example, work that looks at agenda responsiveness, more institutional mechanisms may come into play and neutralise each other. Future research aiming at disentangling the potential countervailing effects of institutions should take such contingencies into consideration.

Acknowledgements

Our research received financial support from Sapere Aude Grant 0602‐02642B from the Danish Council for Independent Research and VIDI Grant 452‐12‐008 from the Dutch NWO. We received excellent comments on earlier versions of this article from Phillipp Genschel, Frederik Hjorth, Will Jennings, Ann‐Kristin Kölln, Lars Mäder and Chris Wlezien as well as from the participants at the annual meetings of the European Political Science Association and the American Political Science Association in 2015. We are also grateful for comments received during the workshop ‘Beyond the Democratic Deficit’ at the European University Institute, 14–15 May 2015; the workshop ‘Responsiveness: Identifying New Research Focuses and Methods’, 26 May 2015 in Gothenburg; and the SPS Departmental Seminar at the EUI on 24 April 2017. Finally, we are grateful for the efforts which Cæcilie Venzel Nielsen and several other student assistants put into coding our data.

Appendix: Policy issues, year, survey and number of countries covered

Notes: EB = Eurobarometer; ISSP = International Social Survey Programme; EES = European Election Study; EVS = European Values Study; ESS = European Social Survey.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

ONLINE APPENDIX A: The relationship and congruence between public opinion and public policy

ONLINE APPENDIX B: Policy scales

ONLINE APPENDIX C: Descriptive information on public opinion, policy, and congruence

ONLINE APPENDIX D: Values on institutional variables by country

ONLINE APPENDIX E: Estimations with alternative electoral system measures

ONLINE APPENDIX F: Salience measure based on the ‘most important problem’ item

ONLINE APPENDIX G: Marginal effects plots of interactions

ONLINE APPENDIX H: Specifications with country fixed effects

ONLINE APPENDIX J: Congruence models excluding opinion majority