1. Introduction

In an era marked by frequent economic shocks and growing demands on public services, the design of effective fiscal frameworks is critical to ensuring fiscal sustainability and productive public investment. While attention has typically focused on national-level fiscal rules, institutions and processes, we argue that the design of subnational fiscal frameworks plays an equally significant role in determining how in practice tax, public spending and investment decisions and hence fiscal sustainability operate at the subnational level.

Authors, including contributors to this volume, have argued that the UK’s current fiscal framework is overly centralised and insufficiently flexible (Chadha et al., Reference Chadha, Küçük and Pabst2021). We agree. But any debate over options for reform at a national level should consider what lessons are emerging about how devolution of fiscal powers is operating at the regional level. Subnational (i.e. devolved) governments are increasingly responsible for a significant share of public spending—accounting for over half in most OECD countries (OECD, 2022)—and thus, the precise design of their fiscal capacity is fundamental to their ability and incentives to deliver both a well-performing regional economy and public services.

To illustrate how devolved fiscal frameworks impact fiscal sustainability, we examine the case of Scotland and its devolved fiscal powers. Over the last decade, the Scottish Government has taken on greater responsibilities for tax and spending, while operating within a specific fiscal framework. It has to try to achieve fiscal sustainability while confronting key long-term challenges, such as demographic change, climate change (particularly the transition to net-zero) and the emergence of new technologies such as AI (Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2024).

As we will argue, a key feature of Scotland’s fiscal framework is the limited scope for borrowing. This has several important implications when analysing fiscal sustainability. First, conventional measures of sustainability such as the debt-to-GDP ratio are not applicable. Second, because the Scottish Government must effectively balance its budget annually, fiscal sustainability challenges materialise immediately in the annual budget process rather than gradually through rising debt ratios. This requires the Scottish Government to address short-term budget pressures simultaneously with longer-term structural challenges. An additional implication of the fiscal framework is that the Scottish Government’s fiscal sustainability depends on both its policies and those of the UK Government. Consequently, the ability of the Scottish Government to achieve fiscal sustainability depends crucially on how the UK Government tries to manage its fiscal sustainability.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In Section 2, we provide an overview of fiscal devolution in Scotland and discuss the Scottish fiscal framework, which underpins the taxation, spending and borrowing arrangements of the Scottish Government. Given what we said above about the close link between fiscal sustainability and the annual budget process, we need to explain details that are relevant to that annual budget process. In Section 3, we discuss how this framework shapes the nature and form of debates over fiscal sustainability in Scotland. In Section 4, we illustrate the practical implications of this by drawing upon recent work by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) in relation to demographics and health. Section 5 provides some conclusions.

2. The Scottish budget and fiscal framework

The evolution of the fiscal arrangements for the Scottish Government reflects a broad trajectory of devolution within the UK, shaped by successive political agreements and constitutional reform. The Scotland Act 1998, following the 1997 devolution referendum, established the devolved Scottish Parliament with control over a range of spending policy areas, including health, education, and justice. Most of these powers were ‘transferred’ from the old Scottish Office to the new Scottish Parliament. Funding largely mirrored that pre-devolution departmental structure, with a block grant—determined by the Barnett formula—acting as the principal funding mechanism (Roy and Eiser, Reference Roy, Eiser, Mitchell and Johnston2019).

Initial tax powers were limited, primarily confined to local taxation—business rates and council tax—and a power to vary the UK basic rate of income tax (the so-called tartan tax). This power was never used. Over time, debates over Scotland’s fiscal powers grew, culminating in two new Scotland acts following, respectively, the Calman Commission (2009) and the Smith Commission (2014), the latter formed in the aftermath the Scottish independence referendum.

2.1. Scotland’s new fiscal powers

The Calman Commission recommended an early expansion of devolved fiscal powers, including partial devolution of income tax and control over Stamp Duty Land Tax and Landfill Tax, all implemented via the Scotland Act 2012. More extensive reforms followed with the Smith Commission, which advocated that the Scottish Parliament should be responsible for raising approximately 50% of its own budget, thereby significantly increasing fiscal autonomy. This was legislated through the Scotland Act 2016, granting the Scottish Parliament new powers over tax and social security.

These two acts have led to several notable changes on taxation. Two which have already been implemented areFootnote 1:

-

• Income Tax on non-savings, non-dividend (NSND) income: the Scottish Government now sets its own rates and bands, though the personal allowance remains reserved to the UK Government.

-

• Land and Buildings Transaction Tax and Scottish Landfill Tax: full devolution of policy responsibilities, with the revenues collected by a new Scottish agency, Revenue Scotland. These new taxes replace the equivalent taxes in the UK (Stamp Duty and Landfill Tax, respectively).

On spending, there were only modest reforms to areas of general public spending. Much more significant changes, however, were related to the devolution of several key social security payments. These payments included those related to:

-

• Child, adult and pension-age disability payments, payments to support carers and support for winter fuel costs. A range of smaller payments, including those related to elements of employability, support for funeral costs, etc., were also devolved.

Alongside this, the Scottish Government also now has the power to implement new social security payments that do not exist elsewhere in the UK.

Next we set out how the Scottish Government has used these new powers.

2.1.1. Tax

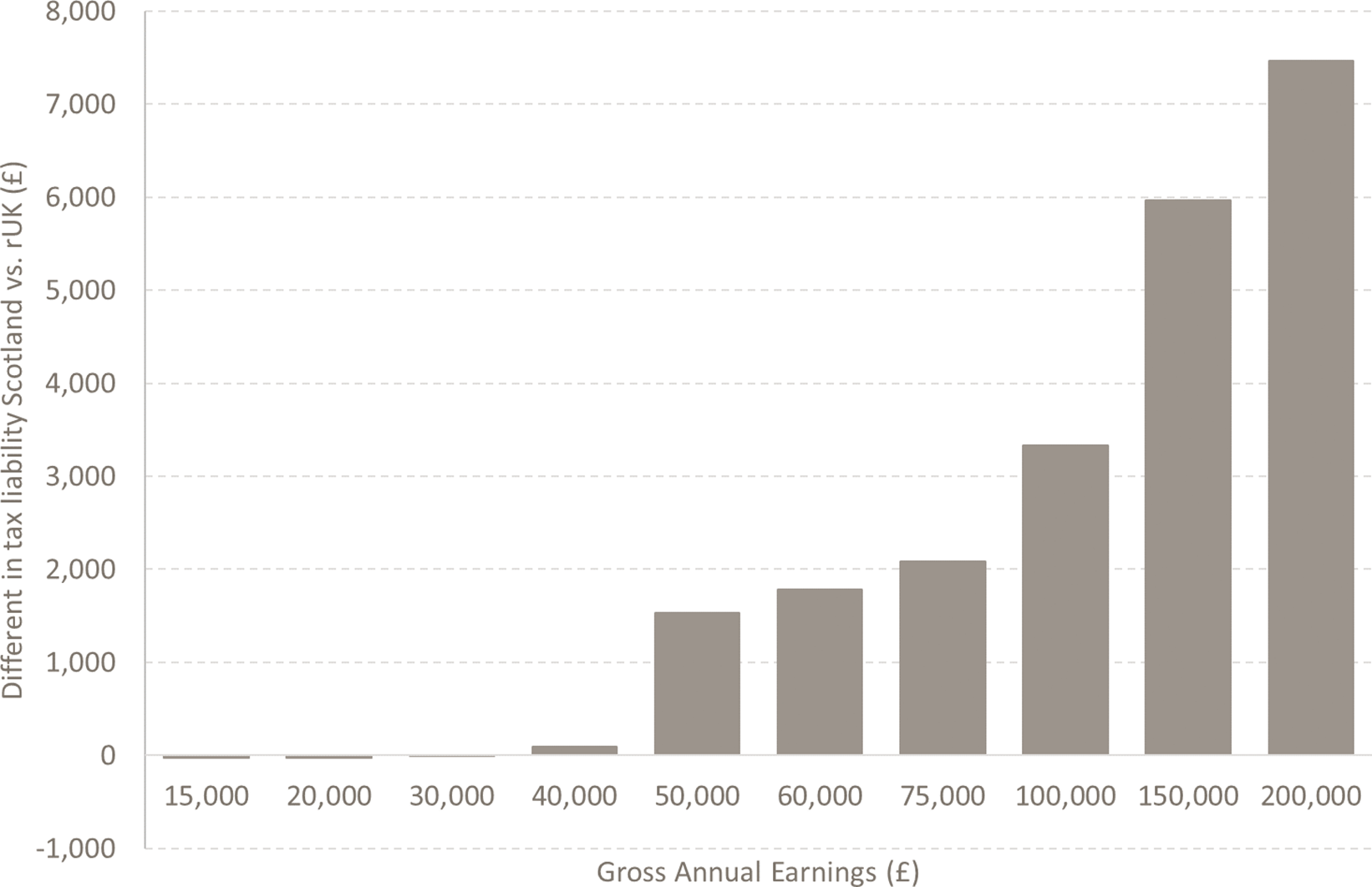

The Scottish Government has introduced a new income tax system, with six bands that include a lower ‘starter rate’ for low earners and higher rates for top earners. As a result, lower earners in Scotland pay slightly less than someone with the same income would pay under the UK tax system, while higher earners pay more. As of April 2025, the maximum saving made by low earners is just under £30 per annum. In contrast, under the Scottish income tax system, someone earning £50,000 pays around £1,500 per year more in tax (around 4% of their after-tax income), with someone on £100,000 paying over £3,000 more (around 5% of after-tax income)—see Figure 1. The Scottish Government has also implemented more progressive property taxes and provided broader relief for small businesses (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Mitchell and Roy2022a).

Figure 1. Differences in tax liabilities between Scotland and the rest of the UK, 2025/26 (£).

Source: Authors’ own calculations.

2.1.2. Spending

The Scottish Government has, arguably, been more ambitious in establishing a different system for social security than on taxation. New benefits have been created, an example being the Scottish Child Payment, introduced with the aim of reducing child poverty. This payment is not available elsewhere in the UK. Other welfare payments have been expanded beyond what is available in the rest of the UK. For example, in its December 2024 Budget, the Scottish Government introduced a policy to mitigate the effects of the two-child limit in Universal Credit, and they have also offered more generous means-testing for pensioner winter heating payments. Finally, the Scottish Government has also introduced a new approach to administering payments. The aim has been to make benefit access more inclusive and administratively straightforward. For example, those claiming disability benefits can produce a wider range of evidence, and be supported in interviews, which contrasts with the system operated by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) elsewhere in the UK.

2.2. The fiscal framework and interdependencies

Underpinning the transfer of greater fiscal powers was the 2016 Fiscal Framework Agreement. This has evolved a little over time, and currently it has the following components.

2.2.1. Resource funding and spending

This refers to the annual ongoing flows of money into and out of the Scottish budget. It accounts for around 90% of the total budget. On the funding side, there are three components.

The first is the block grant. This remains, by far, the largest single component of funding each year. As an illustration, the total resource funding for 2025–26 was around £52bn with the block grant accounting for just over £41bn. The growth of this block grant is determined by the Barnett formula whereby Scotland receives a population share of changes in comparable spending by various Whitehall departments on areas such as health and education that are devolved to Scotland. This makes the major component of the Scottish Government’s resource funding heavily dependent upon decisions taken by the UK Government.

The second component of funding is the revenue that the Scottish budget brings in from devolved taxes. For 2025–26, it is forecast that total devolved tax revenue would be £24.6bn (£21.6bn excluding non-domestic rates), of which around £20.5bn was projected to come from income tax.

The third component of funding comes from what are called block grant adjustments (BGAs). There are two such adjustments. On the tax side, the block grant is reduced by an amount that reflects what would have been raised had Scottish taxpayers continued to operate under the UK tax systemFootnote 2. In 2025–26, this adjustment was projected to reduce the block grant by just over £20.4bn. This means that, in net terms, devolved Scottish taxes add around £1bn to the Scottish budget. This amount that can vary from year to year and can be negative as well as positive. For social security, the block grant is increased by an amount that reflects the amount that would have been paid out in Scotland under the UK social security system as administered by DWP. As a result of the more expansive policies on social security now set by the Scottish Government, in 2025–26, devolved social security spending in Scotland was projected to be just over £6.9bn. However, the associated BGA was just over around £5.6bn. This means that £1.3bn was required to be funded from other areas of spending or through higher taxes. This gap reflects spending arising from all three of the factors referred to above in Section 2.1: the spending on the Scottish Child Payment and other payments not operating in UK; the cost of mitigating policies such as the two-child limit that operate in the UK; and the cost of additional successful applications that arise in Scotland because of the different ways in which payments are now applied for and delivered.

Once the total funding flowing into the Scottish Budget has been determined, the Scottish Government can then allocate it across the different categories of spending according to its own priorities. The fact that a certain amount of money in the block grant arose as a Barnett consequential of spending by the UK Government on, for example, education, does not mean the Scottish Government has to spend that sum on education. Nor does the fact that a certain amount of money flows into the budget through the BGA process for social security mean that that sum of money must be spent on social security in Scotland. This gives the Scottish Government a considerable degree of spending autonomy.

However, one constraint faced by the Scottish Government—like any government—is that the amount that actually ends up being spent on social security is demand-led. That is, once the government has set the eligibility criteria and the amounts of money that are to be paid to people in certain circumstances, the total amount that is actually spent in a given year depends on how many and which type of individuals make a claim and the decisions made by administrators about what award to make. In this context, one degree of control on total spending that it does have is how far to uprate benefits in line with the forecast for inflation for the budget year ahead. In contrast, changing eligibility criteria, while possible, is harder to do in the short run.

2.2.2. Fiscal transfers between years

A crucial feature of the Scottish fiscal framework is that there are very tight limits on borrowing. For resource spending purposes, the Scottish Government can only borrow for forecasting errors related to tax or social security. This means that the Scottish Government may find that, even if it sets a budget in which forecast spending matches forecast income, outturn figures can move out of balance because of forecast errors in the block grant, Scottish tax revenues, BGAs or social security expenditure. When this happens, it may borrow only to cover those specific forecast errors and only within the limited amounts permitted by the fiscal framework. The current limit for such borrowing is up to £600m annually, capped at £1.75bn in 2023/24 prices (Scottish Government, 2023)Footnote 3. What the Scottish Government cannot do is plan to cope with resource structural deficits by planning to borrow against the possibility of future budget surpluses.

Finally, there is further limited scope for smoothing year-to-year fluctuations through a Scottish reserve into which the Scottish Government can put surplus income into each year. It can then draw down these monies in future years. This Scotland reserve is capped at £700m in 2023/24 prices.

Drawing this all together, we can see that, to all intents and purposes, the Scottish Government must effectively try to run a balanced budget and, if anything, needs to plan to underspend.

2.2.3. Capital funding and spending

This accounts for around 10% of the Scottish budget.

The Scottish Government receives funding via a capital block grant determined as a population share of the growth in equivalent capital spending by the UK Government. So, when, in its Autumn 2024 Budget, the UK Government announced a significant increase in capital spending, this meant that the amount of funding available to the Scottish Government for capital projects also rose significantly. The Scottish Government also has limited borrowing powers to fund capital spending. Currently, these are up to £450m per annum, capped at £3bn in 2023/24 prices (Scottish Government, 2023).

2.3. Further institutional features

There have been a series of important other institutional developments to accompany this process of devolution. The Scottish Government now drafts an annual budget bill, typically introduced in December, accompanied by a medium-term financial strategy, typically in May. These are informed by independent forecasts from the SFC, and indeed, the Scottish Government is required by law to set its budget based on the SFC forecasts. The budget includes forecasts of devolved tax revenues, anticipated block grant funding and spending allocations across portfolios.

Fiscal risks from tax revenue forecasts and social security spending—both subject to reconciliation processes against outturn data—make both short- and long-term budget management complex (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Mitchell and Roy2022b). While that is true for many governments, what makes the issue particularly complex for the Scottish Government is that there are two sets of forecasters involved. While the SFC forecasts the revenue derived from devolved Scottish taxes, the forecasts of the associated BGAs are based on forecasts produced by the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR)—the independent fiscal forecaster for the UK Government. The same is true in relation to social security spending.

Therefore, what matters for the volatility of the forecast levels of net tax revenue and net expenditure on social security is not just the accuracy of the forecasts produced by both the SFC and the OBR, but the correlation between the errors.

2.4. Summary and interdependencies

We can see that, acting as a devolved (or subnational) government within a particular fiscal framework, the parameters within which the Scottish Government plans and sets its budget are highly dependent on decisions by the UK Government.

First, the decision that the risks from various UK-wide macroeconomic shocks will be absorbed solely by the UK Government through its borrowing powers has left the Scottish Government having to effectively balance its budget year on year.

Second, the major component of funding for the Scottish Government, the block grant, is dependent on decisions made for UK Government departments, though adjusted to take account of differences in overall population dynamics between Scotland and the rest of the UK.

Third, through the BGA mechanism, what matters is how Scotland performs relative to the rest of the UK on tax and social security. While this can give the Scottish Government powerful incentives to use its fiscal and other powers to grow the economy and ultimately its tax base faster than that of the UK, it also faces the risk of losing net revenue if, including for factors beyond its control, it fails to do so. Equally, it faces picking up the costs of decisions on social security introduced with the aim of producing a more compassionate system, but this leads to higher payments and successful applications.

3. The Scottish Fiscal Commission and fiscal sustainability in a devolved framework

We now set out some key issues that arise when assessing fiscal sustainability in the context of a devolved government working within a particular fiscal framework. To do so, we draw upon the work of the SFC. By way of background, the SFC is the independent fiscal institution for Scotland. Established by the Scottish Fiscal Commission Act 2016, it is tasked with providing independent and official forecasts of the Scottish economy, devolved tax revenues and devolved social security expenditure. In recent years, it has expanded its work to include long-term fiscal analysis. Following recommendations from the Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Constitution Committee, the SFC is committed to producing fiscal sustainability reports (FSRs).

The idea behind such reports is to assess the long-term fiscal sustainability of current government policies when they and the economy are exposed to various drivers such as population growth/decline; population ageing; technological changes, such as AI; and climate change, which play out over long periods of time. While these factors may be at work over the short-term five-year forecasts that typically accompany budget forecasts, their effect may be too small to detect or for policy to respond to. By projecting forward the impact of these drivers over a longer period—say 50 years—it gives policymakers a warning of the long-run impact of these forces and the time to plan any necessary structural change of policy.

While FSRs are often discussed in the context of national governments, there are some crucial aspects of undertaking such reports for subnational governments that have not received sufficient attention. Drawing once again on the particular context of Scotland, we point to four major issues.

First, traditional assessments at the national level—such as those undertaken by the OBR for the UK—assess fiscal sustainability primarily on measures such as the trajectory of public debt relative to GDP. However, such approaches are not applicable in the devolved Scottish context, since, as pointed out in the previous section, the Scottish Government is required to operate within a broadly balanced budget. In response, the SFC has developed a bespoke sustainability metric tailored to this institutional environment: the annual budget gap (ABG). This is defined as the difference between projected funding and projected devolved spending (expressed as a fraction of devolved spending). This is calculated for each year of a 50-year horizon, allowing the SFC to assess both the average level of the ABG—both sign and magnitude—and its trajectory over time to be assessed. The simplicity of this approach belies its analytical power. It allows policymakers to visualise when existing revenue and expenditure policies will become misaligned and by how much.

Second, and relatedly, when the debt-to-GDP ratio is used as a measure of fiscal sustainability, there is scope for governments to choose when to act by way of policy correction if it seems its current policies are not fiscally sustainable. All that is at risk is the possibility that the debt burden becomes larger. However, since the ABG is closely linked to the requirement that the Scottish Government has to effectively balance its budget, there is an immediacy to taking corrective policy action if it seems the ABG is going to quite quickly become negative and large in absolute value. This is not present in the case of national governments.

Third, given the significant interdependencies between Scottish and UK Government fiscal decisions that we pointed out earlier, it follows that, in undertaking a FSR for Scotland, one has to take the current policies of both the Scottish and UK Governments as given. This means that the sustainability or otherwise of current Scottish Government policies will depend crucially on current (and future) UK Government policies. In reality, there is an in-built asymmetry here: the fiscal sustainability of the Scottish Government is inherently linked to the policies of the UK Government, whereas the linkages in the opposite direction are more at the margin.

Fourth, if it turns out that the current UK policies are not fiscally sustainable and future UK Governments take steps to try to achieve sustainability, then the impact on the sustainability of Scottish Government policies—as measured by the trajectory of the ABG—can depend crucially on how the UK Government tries to restore sustainability. If, for example, it tries to restore sustainability by raising taxes, then there is a different impact on the Scottish ABG if it were to base this upon income tax—thereby raising the income tax BGA—than if it were to raise a non-devolved tax, such as national insurance contributions. Similarly, if it chose to spend less on health and education, as opposed to pensions, this would have a direct impact on the block grant flowing to the Scottish Government.

4. Fiscal sustainability, health and demographics

To illustrate how devolved fiscal frameworks impact questions of fiscal sustainability at a sub-central level, we examine how issues of health and population ageing feed through to Scottish fiscal policy. For this, we draw upon recent work of the SFC in its latest FSR published in April 2025.

The methodology underpinning the SFC’s analysis begins with long-term projections of key drivers of public spending and revenue over time, including population size and composition, productivity growth, life expectancy, etc. It then projects how these factors affect Scottish Government revenues, including devolved taxes, and spending in major areas such as health, education and social security. Importantly, it also incorporates BGAs and Barnett formula-based funding of the block grant, which link Scottish revenues and spending capacity to UK-wide fiscal trends. This reflects the interdependencies between Scottish and UK fiscal decisions as generated by the fiscal framework.

4.1. Drivers of fiscal sustainability (health)

The fiscal sustainability of a country or region is intimately interlinked via two principal health channels, each of which presents unique challenges and implications for public policy and long-term budgetary planning.

First, the health of the population influences fiscal sustainability by affecting the economic potential of the workforce and the level of social security spending. Poor health can reduce labour force participation and increase the number of individuals reliant on disability-related benefits. Second, fiscal sustainability is shaped by the demands that poor health places on public expenditure, particularly through health and social care systems.

Scotland’s health performance presents a complex picture of long-term challenges and persistent inequalities. Life expectancy in Scotland has improved over the past few decades, with female life expectancy at birth reaching 80.8 years and male life expectancy at 76.8 years as of 2021–23 - See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Life expectancy, Scotland and England, 1990/92 to 2020/22.

Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2025.

However, Scotland continues to lag behind England by around two years for both sexes. More concerning is the stagnation in life expectancy since 2010, attributed to rising avoidable mortality, a growing burden of disease and potentially diminishing returns from previous public health gains. Healthy life expectancy—representing the number of years people live in good health—has actually declined in Scotland over the last decade. As of 2019–21, males could expect to live only 60.4 years in good health, and females 61.1 years, with Scotland falling behind England in this metric as well. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated some concerning trends in the population health of Scotland, including in mental health and wellbeing. A significant further issue is the extent of health inequalities in Scotland. The gap between the most and least deprived areas is stark. Those in the most deprived areas can expect to die 12 years earlier and experience poor health 25 years earlier than those in the least deprived areas. These disparities are wider than those in England, underscoring the influence of deprivation and socioeconomic factors on public health.

Beyond the underlying dynamics of public health, several structural factors drive health spending growth over the long term. For example, expenditure on healthcare like all public services tends to grow over time as public demand for high-quality health services through time leads to pressure on real wages, staffing levels and expectations of newer and more successful therapies. The growth in chronic conditions, not linked to age, has been well documented (Health Foundation, 2023), and this adds to demand. There are also factors which mean that the costs of healthcare often grow at rates higher than in other areas. For example, healthcare is a labour-intensive sector with relatively low potential for productivity growth. While the wider economy can typically adopt labour-saving technologies over time, healthcare delivery (e.g. GP consultations) can often remain resistant to such efficiencies. This is known as the Baumol effect. Finally, it is often the case that technological improvements—such as innovations in diagnostics, treatments and pharmaceuticals—end up increasing health spending by expanding demand rather than acting as a substitute for existing treatments.

4.2. Drivers of fiscal sustainability (demographics)

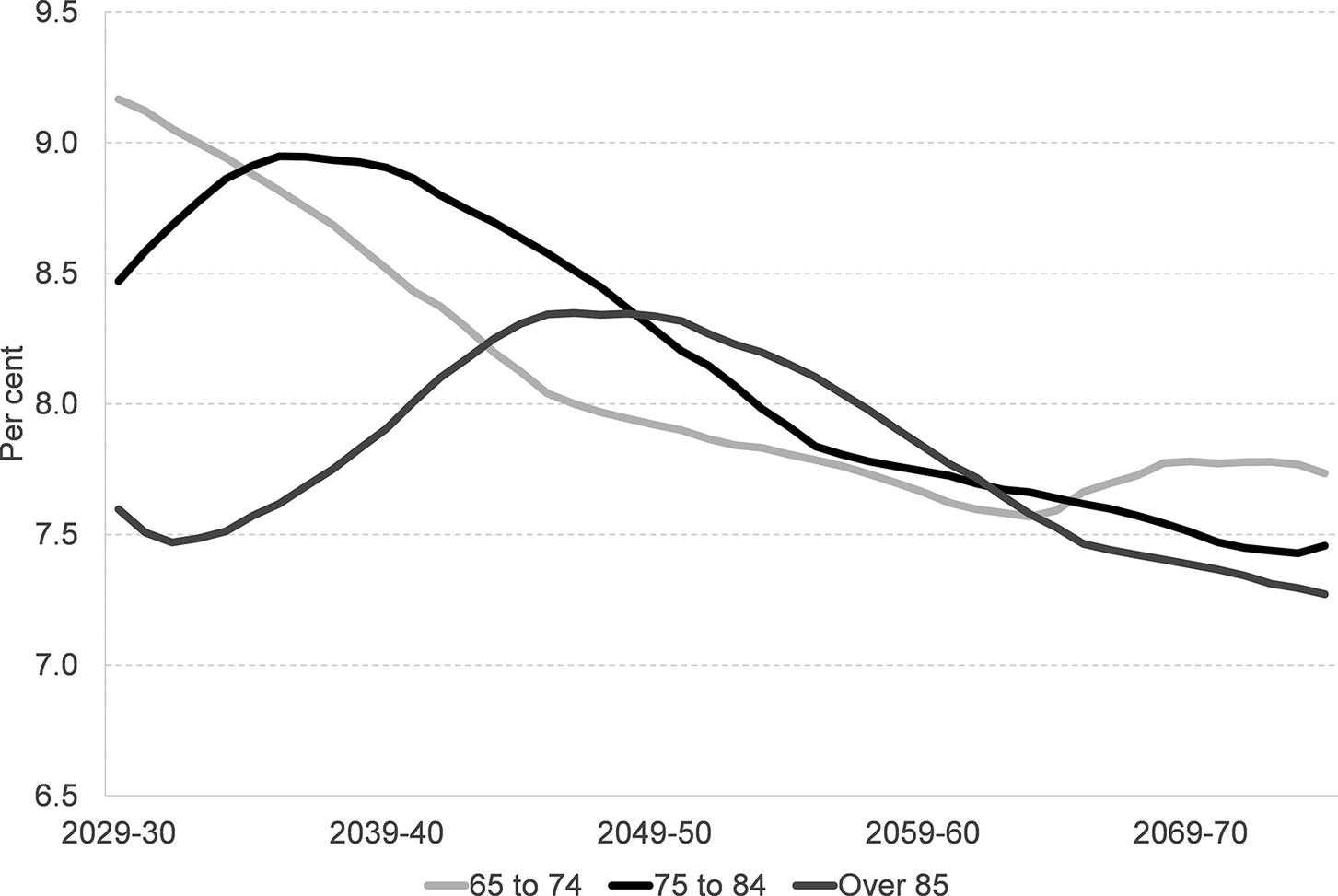

An ageing population has profound implications for public finances. Older populations require more health and social care services. This demographic shift also impacts labour supply, reducing the number of working-age individuals who can contribute to tax revenues. An increasing dependency ratio—the number of dependents (under 16 and over 65) per 100 working-age people—puts pressure on income tax revenues and other sources of funding. Figure 3 presents the age profile of health spending in Scotland, showing that the most significant cost pressures arise from individuals over the age of 70.

Figure 3. Resource health spending by age in Scotland, 2029–30

Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2025.

Projections for Scotland indicate that the country’s population will grow modestly over the next two decades but will eventually plateau, driven primarily by net international migration, while birth rates are projected to remain low. Crucially, population growth in Scotland is expected to lag behind the UK average. But the implications of population ageing are particularly pronounced in the Scottish context. Spending on healthcare, as illustrated in the SFC’s age-specific health spending profiles, increases exponentially with age, particularly after age 70. Between now and 2049–50, the share of those aged over 75 years in the Scottish population is expected to increase substantially. Figure 4 shows that this will increase the share of the UK elderly population living in Scotland.

Figure 4. Projected share of the UK over-75 population—Scotland vs UK.

Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2025.

4.3. Implications for fiscal sustainability

Bringing these elements together, alongside the definition of the ABG outlined above, allows us to assess the long-term fiscal sustainability of the Scottish budget.

First, it is possible to look at the relative implications for fiscal sustainability. Here, what matters is how different fiscal factors impact Scotland compared to the rest of the UK. As an illustration, holding funding by the UK Government for its own health and demographic spending demands at current levels, the SFC analysis projects that an ABG for the Scottish Government will open up several billion pounds. This pressure is front-loaded as the next several decades reflect the period in which Scotland’s demographic pressures exceed those of the rest of the UK, leading to higher per capita health and social care needsFootnote 4.

Second, just as the Scottish budget faces clear risks, these must be understood within the broader UK fiscal context. The OBR projects that the current trends in UK fiscal policy are not sustainable. Based on demographic projections for the UK as a whole, UK net debt is projected to rise from 98% of GDP to 274% over the next 50 years. As highlighted, under Scotland’s fiscal framework, UK-level decisions have direct implications for the Scottish budget via the block grant and BGAs. Assuming that UK Government spending will continue to rise in line with demand, without adjustments for long-term sustainability, is not plausible. Therefore, it is possible to construct a scenario where the UK Government consolidates its fiscal position—via tax increases and spending cuts—and this would result in reductions in funding to the Scottish Government. Under such scenarios, the SFC estimates that the Scottish Government’s ABG becomes materially much larger, implying much more significant spending cuts or tax rises.

This final point highlights—once again—the interdependencies between the UK and Scottish fiscal positions, even under a system of fiscal devolution. Given constraints on borrowing, and the importance of the block grant for the Scottish Government’s funding position, how future UK Governments choose to tackle issues of national long-term fiscal sustainability will have significant implications for devolved fiscal policy choices.

The fiscal framework also has indirect implications on fiscal sustainability, often in what might appear to be—at least at first glance—somewhat counterintuitive outcomes (Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2023)).

For example, one might suppose that a faster growth population might be universally good for tackling issues of long-term fiscal sustainability. But the characteristics of the method used to calculate the BGAs—the index-deduction per capita method—mean that tax BGAs are more sensitive to demographic change than Scottish tax revenues are to the same demographic change. With faster population growth, Scottish tax revenues grow more quickly, mainly because of the larger pool of Scottish taxpayers, but the BGAs increase much more rapidly due to the impact of greater population growth in Scotland relative to elsewhere in the UK. At the same time, a larger population leads to increased pressure on public spending. The net effect, therefore, is a larger ABG.

Similarly, faster productivity growth may also be a typical suggestion for how to help tackle challenges of long-term sustainability. But, here again, the Scottish fiscal framework provides the opportunity of potentially counterintuitive results. While faster productivity growth raises overall tax receipts, Scotland receives only a fraction of these gains because many major taxes remain reserved. However, public spending—which is larger than the taxes that are devolved—is also likely to increase. This gap between devolved spending and devolved taxation means that, all else remaining equal, the ABG widens with faster productivity growth in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK.

5. Conclusions

This paper has argued that fiscal frameworks should not be considered solely through a national lens. As demands on public finances increase—driven by demographic change, persistent health inequalities and rising structural pressures, including in defence—the design and operation of subnational fiscal frameworks become central to any discussion of fiscal sustainability and public investment.

Scotland offers an interesting case study. The Scottish fiscal framework, while conferring important fiscal powers on the Scottish Government, also embeds deep interdependencies with the wider UK fiscal system. These interactions—including through the Barnett formula and new BGAs—mean that fiscal sustainability for the Scottish Government cannot be fully understood without reference to decisions made at the UK level.

The Scottish Government now bears significant responsibility for managing long-term fiscal risks in key devolved areas such as health and social security. This shift marks an important evolution in the accountability and capacity of devolution in the UK. Yet it also highlights the increased exposure of devolved administrations to demographic and economic pressures that they may have only limited ability to influence.

As we have shown, health outcomes and population ageing are now among the most important determinants of Scotland’s fiscal outlook. Scotland faces relatively slower population growth than the UK as a whole, an ageing demographic profile and poorer health outcomes relative to the UK average. These trends are projected to drive up spending and dampen revenues.

Nevertheless, the largest driver of Scotland’s fiscal trajectory remains UK-level policy decisions. The ability of the UK Government to sustainably fund public services across the UK is critical to Scotland’s long-term position. This makes the interdependence between UK and devolved fiscal frameworks not just a technical matter of budgeting, but a strategic concern for policymakers across all levels of government.

In conclusion, national fiscal framework reform must be cognisant of the implications for devolved governments. Equally, any discussion of further devolution—whether in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland or the English regions—must address the question of how long-term fiscal sustainability is managed across multi-tiered systems. Devolved governments need both the tools and the flexibility to respond to long-term fiscal risks, but also a framework that reflects their role in a shared and interdependent fiscal system.