On June 30, 2003, the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro inaugurated its 22nd Military Police Battalion in Complexo da Maré, a sprawling cluster of favelas in the northern zone of the city, dominated by powerful drug-trafficking gangs since the 1980s. The installation of the Battalion was part of an aggressive public security campaign intended to reassert the authority of the Brazilian state in these territories. Rio’s O Globo newspaper compared the inauguration to a scene from the several month-old Iraq War as helicopters flew overhead, dropping 60,000 pamphlets on Maré’s residents, announcing, “Peace is arriving! A new life for Maré!” and asking for their assistance in the state’s campaign against gangs. Footnote 1 After more than a decade of repeated attempts by the Brazilian state to weaken drug-trafficking gangs and win over the “hearts and minds” of local populations, gangs continue to dominate Complexo da Maré to this day.

Despite the highly organized forms of violence that Rio de Janeiro and many other urban contexts in Brazil have suffered over the last several decades, the country remains a “peaceful” and democratic one. It will be found in no datasets on political violence and few discussions of the relationship between violence and politics within political science. Instead, Brazil’s violence is understood to be criminal and not political in nature. And yet, for the residents of Complexo da Maré and millions of other Brazilians, organized crime and its violence is very much a political phenomenon as criminal organizations negotiate (sometimes violently) with the state over not just the control of the drug trade or access to illicit markets but over who is the dominant authority on a local level: who controls violence, provides order, and makes the rules that govern society.

Brazil is not an isolated case. Organized crime has emerged as an important political player in numerous countries by building highly resilient organizations, accumulating vast resources, Footnote 2 and marshalling the effective use and threat of violence. Criminal violence can be highly organized in nature and often involves fundamental aspects of competitive state-building, qualities that demand greater attention from scholars of comparative politics and international relations. Yet because we have isolated the study of political violence to armed groups that are formally motivated by their ambitions pertaining to the state, we lack the conceptual and theoretical vocabulary to describe how and why violent criminal organizations matter for politics in the contemporary world. I seek here to develop such a language, what I term criminal politics.

Political science must expand its focus to include organizations ranging from drug-trafficking cartels, urban gangs, mafias, vigilante groups, militias, prison gangs, and smuggling networks, among others. I argue that criminal organizations, like other non-state armed groups, have developed variously collaborative and competitive arrangements with states that determine levels of violence and the nature of political authority and order in many subnational contexts. Building on Paul Staniland’s “armed politics” framework, I propose a simple conceptual typology of organized crime-state relations that spans outright confrontation to arrangements in which the two become virtually indistinguishable through the process of integration. Footnote 3 While the typology I propose neither theorizes the causes of these outcomes nor professes to be exhaustive, it seeks to map the existing variation in crime-state relations. By doing so, I hope to break down some of the disciplinary barriers that have prevented organized crime from being viewed as political and to stimulate further research that incorporates these organizations into the literature on politics and violence.

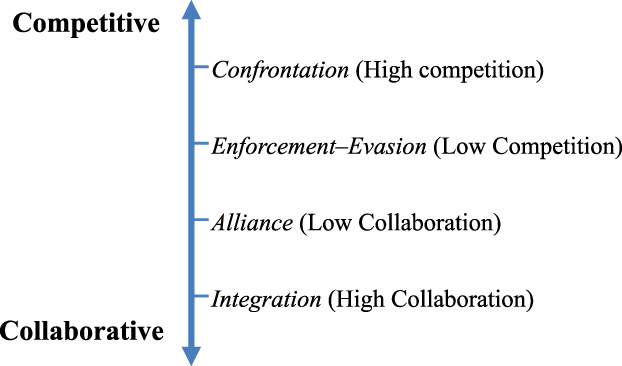

In the first of five parts I contend that the dominant paradigm in the study of political violence that has neatly separated political from criminal is neither conceptually nor theoretically justified. I show that distinguishing between the two has become increasingly difficult as illicit networks and criminal actors shape the patterns of violence in most contemporary conflicts. Next, building on recent work at the intersection of several social science disciplines, I argue that organized criminal violence should be considered, like other types of political violence, a competitive form of state-building. Developing the conceptual language and analytical framework to integrate these phenomena follows. I argue for an integrated approach to the study of politics and violence that incorporates both political and criminal non-state armed groups within a larger continuum of violent processes. To this end, I distinguish between four crime-state arrangements that vary from confrontation (high competition), enforcement-evasion (low competition), alliance (low collaboration), to integration (high collaboration). I then describe the dynamics of these arrangements and use empirical examples from around the world to demonstrate the utility of such an approach. I conclude by suggesting several avenues for future research that build on the criminal politics framework and that can further illuminate not only existing scholarship on political violence but the relationship between violence and politics more generally.

Conceptualizing Violence in Armed Conflict

In recent years, the literature on political forms of violence has expanded dramatically as scholars have engaged in increasingly methodologically sophisticated and theoretically driven research, yielding fascinating insights and revolutionizing the way we understand civil war, terrorism, genocide, communal riots, and electoral violence. Many of these same scholars have also recognized that the mutually exclusive categories that distinguish various forms of violence rely on rather vague criteria. Jeffrey Isaac, for instance, declared the dominant paradigm within the study of political violence that has separated war from peace and conflict-related from criminal is no longer valid. Footnote 4 Nicholas Sambanis has argued that it is empirically difficult if not impossible to distinguish between civil war, coup, politicide, and criminal violence. Footnote 5 These sentiments are echoed by Christopher Blattman and Edward Miguel in their exhaustive review of the civil war literature when they argue the distinction between the various forms of political instability—civil wars, interstate wars, coups, communal violence, political repression, and crime—“has largely been assumed rather than demonstrated.” Footnote 6 In addition, Stathis Kalyvas has argued that the stated objectives of state and non-state armed groups and popular understandings of the causes of political violence seldom match onto how and why violence is used on the ground, Footnote 7 even suggesting that much political violence may have more in common with criminality in that it is neither motivated by politics nor collective in nature. Footnote 8 More generally, Paul Brass argues against top-down categorizations of violence because they reflect more the interpretations by authorities, media, politicians, and even scholars than the inherently political nature of a violent event itself. Footnote 9

Building on these frustrations, I argue that the continuing exclusion of organized criminal violence from the literature on political violence is neither empirically nor theoretically justified and constitutes a missed opportunity for scholars to situate traditional forms of political violence “within a broader set of processes that combine politics and violence.” Footnote 10 The political violence literature has separated organized crime from other non-state armed groups by claiming that the former is motivated by the accumulation of resources while the latter are driven by some larger political or ideological goal—secession, revolution, or policy change. Footnote 11 This simple distinction, however, dramatically overemphasizes the degree to which non-state armed groups are committed to their political projects as many seem more interested in gathering resources and accumulating wealth than they are in real political change or state capture.

Following the end of the Cold War, insurgencies and rebel groups have increasingly turned to criminal activities including resource extraction, looting, and the production and sale of illicit goods to support their organizations. Footnote 12 It may be that non-state armed groups are merely finding the most reliable and plentiful way to achieve their political goals or that ideological and identity-related frames continue to be adopted for more instrumental reasons. Footnote 13 It may also be that engaging in such criminal activities in itself changes the objectives of these organizations or offers them forms of political capital that would be otherwise unavailable. Footnote 14 While the effect of resources on the nature of political violence is an ongoing topic of debate, the empirical reality is that the political and criminal motivations and behaviors of armed groups in conflict are not mutually exclusive and are incredibly difficult if not impossible to parse out.

In this vein, Eli Berman and Aila Matanock, in the Annual Review of Political Science, accept that the objectives of political non-state armed groups are various and can include the control of territory, policy concessions or the capture of economic rents. Footnote 15 This assertion is corroborated by recent research on civil wars in which we observe a multitude of armed groups that are not primarily engaged in conflict over the control of the state. On the one hand, the fragmentation of insurgent groups has led to the proliferation of armed actors that often compete with one another and are not all equally committed to state capture. Footnote 16 Similarly, on the side of the state, 81% of modern conflicts involve pro-government militias, Footnote 17 many of whom “shift their loyalties and may pursue agendas that are at odds with the interests of the state.” Footnote 18

Such dynamics are particularly evident in recent conflicts in North Africa and the Middle East that contain a kaleidoscope of armed groups operating on the periphery of weak states and conflict zones where disorder and insecurity provide them space to operate and the opportunity to control territory and generate illicit revenues. Footnote 19 For example, in Syria, the number of non-state armed groups has exploded to more than 1,000 Footnote 20 with some of these groups relying heavily on criminals for their recruits. Footnote 21 Moreover, in Nigeria, Somalia, and Mali, several prominent groups (Boko Haram, Al Shabbab, and the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa) espouse radical Islamist ideologies but are involved in numerous criminal activities and illicit markets that belie rigid ideological motivations. Footnote 22

In other conflict contexts, distinguishing between criminal and political violence has been made increasingly difficult because states and other non-state armed groups have formed strategic relationships with criminal organizations to help them defeat common enemies and gain access to resources and illicit markets, as well as trafficking routes. For instance, in Afghanistan, the Taliban forged alliances with drug-trafficking networks that not only provided them access to illicit markets but also significant forms of political capital among poppy farmers. Footnote 23 During more than three decades of civil war, the Guatemalan military maintained numerous strategic alliances with criminal organizations that allowed the regime to exterminate its opponents through third parties. Footnote 24 This is reminiscent of several African conflicts in which state leaders outsource their monopoly of violence to criminal organizations, foreign networks, and mercenaries. Footnote 25 In addition, on the borderlands between Colombia, Venezuela, and Peru, criminal organizations have developed various “arrangements of convenience” with rebel groups and state actors. Footnote 26 Finally, in the former Yugoslavia, criminals and hooligans transformed themselves into paramilitary organizations that provided support to the Croatian and Serbian militaries during the conflict. Footnote 27 Such cases are not outliers but appear to be the norm and have made characterizing the violence occurring in these conflict contexts extremely difficult.

Recognizing the complexity of these environments, Staniland contends that political violence scholars have incorrectly understood civil wars to be a “straightforward struggle for a monopoly of violence.” Footnote 28 Instead, he recognizes that civil wars often include a “dizzying array” of armed actors that actively and passively cooperate for mutual benefit even while engaging in direct military hostilities. According to Staniland, such “bargains, compromises, and clashes” between states and non-state armed actors about order, authority, and violence are characteristic not just of conflict contexts but in situations as diverse as Chicago’s housing projects, Italy’s mafias, elections in the Philippines, and arrangements between police and criminals virtually everywhere. Footnote 29 I take this claim seriously.

Conceptualizing Organized Criminal Violence

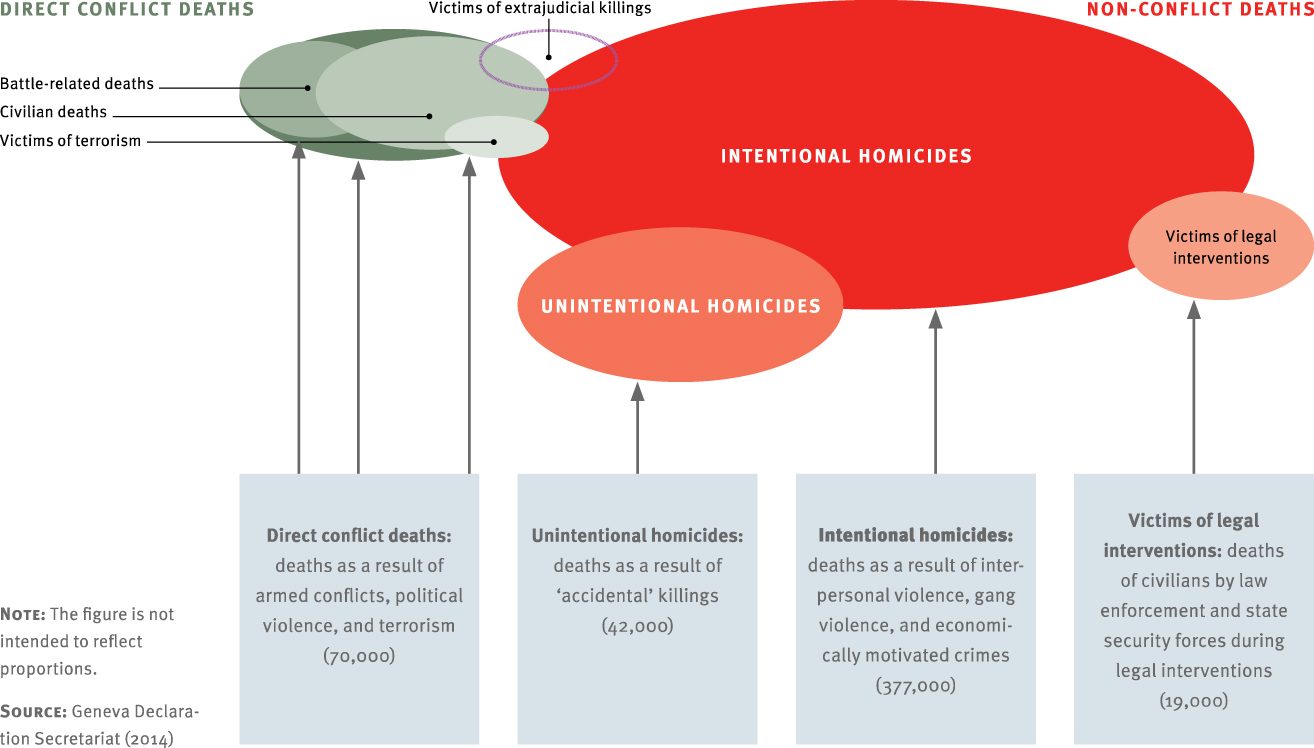

In recent years, organized criminal violence has surpassed traditional forms of political violence as the leading cause of instability in much of the world. According to a Geneva Declaration report, from 2007–2012, there were on average 70,000 yearly direct conflict deaths—battlefield and civilian casualties during an armed conflict or terrorist attack—while intentional homicides from non-conflict settings averaged 377,000 deaths over that same period. Footnote 30 Figure 1 is a visual representation of this data. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has also estimated that 26% of violent deaths in eleven countries in the Americas, 14% in six Asian countries, and 6% in nine European countries are directly caused by organized crime, likely resulting in more violent deaths per year than armed conflict. Footnote 31 Moreover, of the fourteen most violent countries in the world from 2004–2009, only five would be considered conflict settings. In fact, despite the fact that Iraq was in the midst of a deadly civil war, El Salvador was, proportionally, the most violent context in the world for this period. Footnote 32

Figure 1 Distribution of the victims of lethal violence per year, 2007–2012

Note: Reprinted with the permission of the Small Arms Survey.

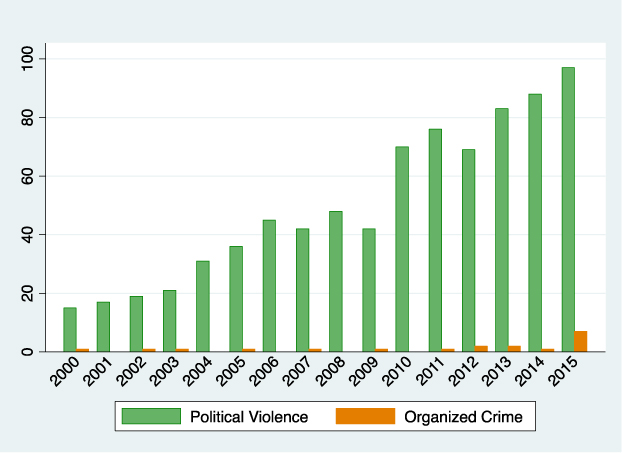

Notwithstanding its increasing relative importance, political science has mostly continued to ignore organized criminal violence. To demonstrate this lack of attention, I conducted a search in ten top political science journals for articles published on topics related to organized crime, gangs, cartels, vigilante groups, trafficking organizations, and mafias since 2000 (refer to figure 2). Footnote 33 I found only 19 such articles for this entire period. As for traditional forms of political violence—civil war, rebellion, insurgency, and terrorism—a similar search resulted in 799 article citations, growing from just 15 in 2000 to nearly 100 in 2015 even though the occurrence of political violence has diminished considerably since its peak in the early 1990s. Footnote 34 This disparity is increasingly unjustified.

Figure 2 Citations in ten top political science journals

Figure 3 Typology of crime–state relations

Despite this lack of attention within political science, for some time scholars working at the intersection of several social scientific disciplines have viewed criminal violence not as a mere blip on the state’s path to the monopolization of violence but as an essential form of competitive state-building, a characteristic often attributed to purely political forms of violence. Most famously, Charles Tilly theorized the origins of European nation-states to be the result of violent competition between criminal-type organizations. Footnote 35 In later work, he argued that all forms of collective violence (ethnic conflict, criminal violence, riots, and others) are fundamentally tied to processes of claim making and collective action within different types of states. Footnote 36 In an edited volume, Diane Davis and Anthony Pereira build on Tilly’s work by highlighting the role a wide range of irregular armed forces (paramilitaries, vigilantes, terrorists, and militias) play in state formation trajectories. Footnote 37 Gangs, cartels, mafias, and other criminal organizations can easily be added to this list.

Such dynamics are a prominent feature of most contemporary Latin American states. For instance, Vanda Felbab-Brown contends that

it is important to stop thinking about crime solely as an aberrant social activity to be suppressed, but instead think of crime as a competition in state-making. In strong states that effectively address the needs of their societies, the non-state entities cannot outcompete the state. But in areas of sociopolitical marginalization and poverty—in many Latin American countries, conditions of easily upward of a third of the population—non-state entities do often outcompete the state and secure the allegiance and identification of large segments of society. Footnote 38

Desmond Arias and Daniel Goldstein, similarly, argue that high levels of violence throughout the region are inextricable from the establishment and maintenance of the region’s democratic regimes as numerous states “coexist with organized, violent non-state actors and stand side-by-side with multiple forms of substate order.” Footnote 39 Such dynamics are not, however, exclusive to Latin America. In several African contexts, Adrienne LeBas argues that local forms of order implemented by ethnic militias and vigilante groups map directly onto the political strategies and aims of elites. Footnote 40 Peter Andreas has also traced the central role of illicit markets and actors in the American fight for independence as well as the numerous wars and violent processes that have fundamentally shaped the United States’ institutions over the course of its history. Footnote 41 Instead of viewing organized criminal violence as merely epiphenomenal to the ongoing process of state formation, these scholars have put it front and center.

Perhaps the relationship between organized criminal violence and state-building is most self-evident in post-conflict environments. The transition from war to peace is conventionally thought to signify the end of competitive state-building and the beginning of a more stable domestic environment. This binary distinction, however, elides the various ways in which violence continues or is transformed during these transitions. For instance, many former combatants and military personnel never fully demobilize, joining the state security apparatus or criminal organizations as a path to continue violent and illegal activities, gain access to resources, and ensure high levels of impunity. In several Central American countries with histories of political conflict, members of the security apparatus acted as informal powerbrokers, allowing impunity and violence to continue despite transitions to electoral democracy. Footnote 42 In Colombia, following peace negotiations in the early 2000s, former paramilitaries remobilized as criminal organizations, engaging in many of the same violent and illegal activities as before. Footnote 43 These examples are indicative of the trajectory of numerous armed groups that fail to demobilize and have evolved into criminal organizations following conflicts. Footnote 44 While such criminal organizations and their violence may seldom be viewed as a direct threat to central governments, they can be equally instrumental to the formation and evolution of state institutions and should be understood as such.

The transition to democracy has also produced, not resolved, competitive state-building dynamics in many cases. For instance, José Miguel Cruz asserts that the explosion of criminal violence in many Latin American states is inseparable from the transition to democracy as state actors throughout the region have allowed or directly collaborated with criminal and extralegal actors in their search for higher levels of political legitimacy. Footnote 45 Similarly, the rise of the Russian mafia during that country’s transition to democracy involved what Vadim Volkov has referred to as violent entrepreneurs—former military and public security officers—forming their own criminal organizations and private protection firms that undermined the state’s own monopoly of violence. Footnote 46 This is not, however, just a recent phenomenon. Diego Gambetta argues that the Sicilian mafia’s formation in the middle of the nineteenth century can be traced to demands for “private protection” amid the larger transition from feudal political institutions to a formal property-rights regime. Footnote 47 At the time, the newly unified Italian state “had to fight to establish itself and its law as the legitimate authority and a credible guarantor . . . It also had to compete with a rival, an entrenched, if nebulous, entity which had by then shaped the economic transactions as well as the skills, expectations, and norms of native people.” Footnote 48 The Sicilian mafia, once thought to be an aberration, continues to operate in the region to this day, proving itself a resilient form of social organization whose structure and functions have been replicated across much of the world.

We can most clearly observe organized crime’s state-building activities at the micro-level. In areas where they operate, organized crime often seeks to control violence to protect and expand their economic interests, facilitate transactions, and ensure the safety of members. With this control of violence and its possible monopolization, criminal organizations are then forced to deal with residents whose outright or tacit support they require to avoid enforcement and to defend their territories from rival criminal organizations. In this regard, nearly all criminal organizations will implement at least a very basic system of governance after consolidating territorial control, which is an oft-noted dynamic of politically-oriented armed groups as well. Footnote 49

Many criminal organizations go on to develop more significant ruling structures and institutions to deal with various aspects of resident life, in some cases providing elaborate systems of law and justice and significant forms of social welfare. For instance, Graham Denyer Willis has argued that the Primeiro Comando do Capital in São Paulo, “sits at the heart of the governance of the urban conditions of life and death” by offering an alternative system of law and justice for populations that have been heavily criminalized by the state. Footnote 50 Dennis Rodgers details how Nicaragua’s pandillas impose order in urban neighborhoods and create strong community-level identities and allegiances that constitute what he terms “social sovereignty.” Footnote 51 In the American context, Sudhir Venkatesh has similarly described how Chicago gangs can become a “community institution” by providing “positive functions” to local neighborhoods. Footnote 52 Most systematically, Arias has outlined how criminal groups in Rio de Janeiro, Medellin, and Kingston have developed localized armed regimes that include the provision of security, policymaking, and civic organizing. Footnote 53

Scholars from a variety of disciplines have attempted to understand the implications of these local relationships, often noting how both criminal organizations and political non-state armed groups provide security and authority in the absence of a capable state. Footnote 54 In this vein, Sambanis has argued that organized violence, in all of its guises, shares important underlying mechanisms such as demand for looting, desire for political change, opportunity to mobilize, and the mechanisms that lead to claim making and resource extraction. Footnote 55 Similarly, Diane Davis has suggested the use of the concept “fragmented sovereignty” to help us understand how criminal organizations are forming the foundation of “new imagined communities of allegiance and alternative networks of commitment or coercion that territorially cross-cut or undermine old allegiances to a sovereign national state.” Footnote 56 Despite the fact that criminal organizations do not engage in such state-building activities for the explicit purpose of taking over or breaking away from the state, the consequences of these actions matter not only for understanding global violence but the institutional trajectory of numerous states. And yet political science continues to lack a conceptual framework for incorporating these insights into the literature on politics and violence. This is the task of the following section.

Criminal Politics: A Typology of Crime-State Relations

In recent years, several scholars have proposed new categories and concepts to reflect the changing nature of global violence. Footnote 57 These attempts are noteworthy in their willingness to reimagine the neat categories that, until now, have separated forms of violence. But I would like to chart a different path forward by outlining an organizational-level approach that seeks to locate political and criminal violence within the same conceptual terrain. Here I borrow from Staniland’s concept of “armed politics,” which focuses on the various state-armed group interactions that occur in the midst of civil war. Footnote 58 Building his conceptual framework on recent advancements in the state-formation literature that refute the commonly held assumption of states as “homogenizing, monopolizing Leviathans,” Staniland recognizes that most states have strategically developed both competitive and collaborative arrangements with various non-state armed groups within their territories. Footnote 59 This approach is relevant to the study of organized crime in two key respects.

First, criminal organizations are found in virtually every country and, like other non-state armed groups, maintain a similarly broad and complex array of relations with the state. They have confronted state security forces directly, assassinated politicians, bureaucrats, and judges, and coerced numerous state agents while, in other circumstances, they have negotiated with, infiltrated and been supported by political parties, state agencies, and public security apparatuses. This variation is an oft-noted feature of research on organized crime. For instance, Arias has shown how criminal organizations develop localized armed orders in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas by variously competing or collaborating with the state. Footnote 60 Eduardo Moncada has outlined how the collaborative and competitive dynamics between armed groups, business elites, and the state account for public security and development outcomes in Cali, Medellín, and Bogotá, Colombia. Footnote 61 In northern Peru, Orin Starn found that extra-legal peasant patrols maintained various relations with the state that involved “manipulation, as well as confrontation, interdependence as well as mistrust, and cooperation as well as conflict.” Footnote 62 In the Russian context, Volkov argues that following the dissolution of the Soviet Union a proliferation of violent entrepreneurs in that country competed and collaborated with the state over the regulation and monopolization of violence. Footnote 63 This variation is perhaps best expressed by Paolo Borsellini, an assassinated Italian Anti-mafia prosecutor: “Politics and mafia are two powers on the same territory; either they make war or they reach an agreement.” Footnote 64

Second, an “armed politics” approach to organized crime also offers an opportunity to more clearly integrate these organizations within the study of politics and violence. Instead of segregating armed groups according to their putative motivations, we should understand the accumulation of the means of violence, even if not for the purpose of complete territorial hegemony, as an inherently political project. It is, at its foundation, about the projection of power and in direct conflict with any state’s alleged monopoly of violence. All violent organizations across the criminal/political spectrum are engaged in strategic interactions with the state that determine the “rules of the game” and the nature of political authority in any given context. The use, threat, and control of violence is inherent to this process. While I do not dispute the fact that there are important differences between violent organizations of various types, I seek to bridge the disciplinary and conceptual divides that have long separated these actors and their violence.

Building on the “armed politics” framework, I propose the concept criminal politics, which focuses on interactions between states and violent organizations that are motivated more by the accumulation of wealth and informal power and which seldom have formal political ambitions pertaining to the state itself. Footnote 65 Distinguishing between crime-state arrangements is essential to account for levels of violence, local security dynamics, development trajectories, and the functioning of political institutions, as well as the nature of political order and authority in areas where organized crime operates. As a first step toward mapping these relations, I propose a simple typology.

First, I identify confrontation as the most competitive arrangement. These are contexts in which criminal organizations directly target and kill state agents and in which the state uses highly repressive tactics in its effort to destroy or subdue these organizations. I differentiate these relations from the much more common enforcement-evasion arrangements in which criminal organizations do not use violence directly against state agents but also do not collaborate with the state. In these contexts, the state enforces against organized crime using traditional public security mechanisms, refraining from the most coercive means to do so while criminals attempt to evade these efforts. On the collaborative side of the spectrum, the category of alliance refers to contexts in which organized crime maintains formal or tacit agreements that limit enforcement and allow both the state and organized crime to mutually benefit. Integration, meanwhile, refers to the highest form of collaboration in which organized crime is directly incorporated into the state apparatus, allowing criminals to engage in violent and illegal activities with impunity.

This typology shares much in common with Staniland’s “armed orders” in which he distinguishes between hostilities, limited cooperation, and alliance arrangements. It departs, however, in three important ways. Footnote 66 First, within “armed politics,” the incorporation of a non-state armed group into the state (often through the process of demobilization) constitutes an end to the autonomous organization. Organized crime, on the other hand, often maintains its autonomy even while it is incorporated into the state apparatus as integration is most often achieved through rampant corruption or formal electoral processes and not demobilization. Second, although criminal politics may involve some direct violence between states and criminal organizations it never includes all-out war for territorial hegemony, a distinguishing characteristic of inter and intra-state war. Thus, criminal politics does not include the most competitive forms of relations, reserved for non-state armed groups that seek to take over or break away from the state. Third, criminal politics only restricts its scope to cohesive organizations Footnote 67 that engage in illicit activities for profit Footnote 68 and for which violence is a constitutive feature. Footnote 69 The focus on violence differentiates this approach from the larger literatures on contentious politics or social movements in that the use of violence determines the nature of these organizations’ relationships to their members, local populations, the state, and other political and economic actors in society. Finally, the organizational component differentiates criminal groups from individual criminals and diffuse or transient groups that come together for short periods of time to engage in violence, such as hooligans, riot crowds, or looters though there may be some informal organizational structure to these groups. Footnote 70

Before analyzing these relationships in greater depth, there are several important distinctions I will make regarding the scope of criminal politics. First, unlike other attempts to apply the concept of war or insurgency directly to episodes of large-scale criminal violence, Footnote 71 the intention here is to include criminal organizations and their violence within the broader category of political violence. Second, states are complex, multi-faceted organizations and organized crime can collaborate with some actors and agencies within the state apparatus while simultaneously competing with others. In this regard, high levels of collaboration do not, in every case, prevent the possibility of violence and, conversely, competitive relationships can include some low-level forms of collaboration. While this complicates distinguishing between various arrangements, the use of violence against the state as a matter of policy precludes the possibility of sufficiently high-level collaboration with state agents, otherwise criminals would not need to resort to outright violence. For analytical parsimony, I have simplified the state in this typology but this is an area that is worth future investigation. Moreover, low-level collaboration between state agents and criminals do not distinguish between collaborative and competitive arrangements as most criminal organizations will engage in this behavior opportunistically. Instead, collaborative arrangements are characterized by the ability of organized crime to integrate members of the state apparatus into their organization directly or to come to agreements (both tacit and formal) with high-level public security officials, politicians, bureaucrats, and judges that prevent enforcement and the need for confrontation. Finally, crime-state relations are often fluid, shifting back and forth between these various arrangements over time. In some cases, arrangements can be short-lived as relations shift in quick succession while other arrangements can persist for decades. The typologies to follow address these dynamics.

Confrontation

We can view organized crime that directly targets the state and its agents with violence as the most competitive form of crime-state interaction. Criminal organizations have done so not to take over the state or break away from it but to influence state policy regarding enforcement, to assert their local dominance, and to maintain their access to resources from illicit markets. Several examples will serve to demonstrate the nature of these confrontations.

Perhaps the best example of confrontation has occurred in Mexico following former president Felipe Calderón’s military offensive against nearly a dozen regionally concentrated drug-trafficking cartels in 2006. The result of this crackdown is well-known as Mexico suffers from what some have referred to as a “criminal insurgency” in which cartels have targeted state security forces, politicians, public officials, prosecutors, and judges while also confronting each other and terrorizing the citizenry. Footnote 72 Even though violence against state forces comprises just a small percentage of the total deaths, Footnote 73 such confrontations precipitated even larger violent processes as the state targeted cartel leaders, fragmenting these organizations and producing extreme violence in many regions. Footnote 74 Until 2014, these dynamics had resulted in an estimated 60,000–70,000 homicides, levels of violence not reached in most civil war environments. Footnote 75

The Mexican case demonstrates the utility of focusing on the variety of relationships that organized crime maintains with the state as confrontation between the cartels and the Mexican state followed a much longer period of stable collaboration. For more than seven decades, the Partido Revolucionário Instititucional (PRI) monopolized all political offices within the country, allowing politicians to offer protection to criminals and exert a high degree of control over the country’s drug-trafficking cartels. But beginning in the late 1980s, the PRI gradually lost its stranglehold on the Mexican political system. Footnote 76 Due to increasing party competition and alternation, Footnote 77 the disruption of patronage networks, Footnote 78 and the breakdown of coordination within and across government agencies, Footnote 79 the PRI was no longer able to exert the same degree of control over the cartels and, amid rising levels of inter-cartel violence, this eventually led to outright confrontation. We can observe similar confrontational dynamics in several other cases.

For instance, Benjamin Lessing has compared the dynamics in Mexico to two other significant cases of confrontation between the Colombian state and the Medellin cartel from 1983–1994 and between the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro and the Comando Vermelho gang faction from 1985 to the present. He has termed these episodes “wars of constraint” in which organized crime, in an effort to provide themselves high levels of impunity, uses violence against the state to directly influence policies and their enforcement. Moreover, he argues that the choice to confront the state by criminal organizations was in response to unconditional and repressive enforcement strategies. Footnote 80

We can add several other cases to this category. First, the Primeiro Comando do Capital (PCC) of São Paulo has engaged in several episodes of outright confrontation with the state. In 2006, to influence elections in that year, PCC members rebelled in more than 70 prisons, taking control of these institutions and killing 43 public security agents. Footnote 81 In another wave of violence in 2012, PCC members killed dozens of off-duty police over the course of several months in reaction to police killings of PCC members. Footnote 82 The PCC’s confrontations with the state, however, were short-lived and returned to a less violent yet still competitive status quo in which outright violence against state agents was eschewed. In a similar dynamic, since the early 1990s and the breakdown in previously collaborative arrangements, the Cosa Nostra of Sicily have sporadically confronted the state by assassinating police commissioners, mayors, judges, and Parliament members to influence enforcement policies and electoral outcomes. Footnote 83 Finally, following the end of an 18-month negotiated truce, the El Salvadoran state and two transnational gangs (Barrio 18 and Mara Salvatrucha 13) have been engaged in what some have referred to as the “Dialogue of Death” in which gangs target judges, prosecutors, policemen, and members of the armed forces while the state has increased its repressive measures even going so far as to declare the gangs “terrorist organizations.” Footnote 84 As these examples make clear, confrontation is seldom a long-lasting or stable equilibrium but is more often characterized by intermittent or periodic episodes of violence. Like the other arrangements, there appears to be no definitive trajectory by which confrontation is arrived to. It can be the outcome of escalating lower-level competition or the breakdown of more collaborative arrangements. Moreover, the return to a less-violent equilibrium can result in any one of the other arrangements.

Enforcement-Evasion

Episodes of confrontation, however, continue to be rare. Most competitive relations between the state and organized crime, which I refer to as enforcement-evasion arrangements, are characterized by a state that uses traditional enforcement mechanisms to combat organized crime to which criminals respond by attempting to evade enforcement. On the one hand, Lessing makes the clearest distinction between criminal organizations that confront the state and those that prefer to “hide and bribe,” as the latter seek to avoid enforcement by nonviolent corruption and bribery of politicians, judges, bureaucrats, and security agents. Footnote 85 While “hiding and bribing” may sound more like a collaborative arrangement, the vast majority of criminal organizations are unable to buy off federal judges or influence the formation of policy to the same degree as Pablo Escobar or Mexico’s cartels and rely much more heavily on hiding to avoid enforcement. Even in the case of Rio de Janeiro in which the Comando Vermelho faction has frequently confronted the state and terrorized the city, two other powerful factions, Terceiro Comando Puro and Amigos dos Amigos have mostly avoided confrontation but continue to maintain more competitive relations with the state as they have been unable to meaningfully penetrate the state apparatus. Only in rare cases have these factions moved into more collaborative territory and their competitive relations are primarily characterized by enforcement-evasion dynamics. Footnote 86

Angelica Duran-Martinez has also distinguished between confrontational and evasive arrangements. Footnote 87 She argues that the cohesiveness of the public security apparatus in several Mexican and Colombian municipalities effectively prevented organized crime from penetrating the state’s institutions, deterred confrontations through the threat of credible enforcement, and forced criminals to hide much of their violence. However, she notes that if and when the state takes a more aggressive stance toward organized crime “the incentive to hide violence disappears” and criminals may choose “to retaliate against or pressure the state.” Footnote 88

While the enforcement practices of states have prevented more confrontational relationships, they have simultaneously incentivized the emergence and expansion of organized crime. Low-level competitive dynamics of enforcement and evasion are common throughout much of the world as marginalized and socially excluded populations have either been neglected by the public security apparatus or been on the receiving end of targeted enforcement policies. In many of these contexts, we observe the emergence of criminal organizations that engage in violence but are also known to control violence and insecurity on a local level. Residents in these areas often view the state as a negligent or repressive presence and criminal organizations as a competing source of authority or a means through which some residents can gain access to resources in impoverished communities. In these contexts, criminal organizations can often depend on the cooperation of local communities to effectively evade enforcement.

In the American context, gangs exist in nearly every major urban center. While we may think of urban contexts as spaces where the state has a more secure monopoly of violence, the reality is that many individuals from marginalized and disadvantaged populations suffer high levels of state repression and are susceptible to many different forms of violence. To explain the rise of criminality and the emergence of street gangs in these urban communities, sociology has developed a dominant “social disorganization” theory that ties such outcomes to the dysfunction of social institutions that traditionally controlled violent criminality. Footnote 89 Whatever their origins, the relations these organizations maintain with the state are clearly on the competitive end of the spectrum. Even though they have mostly refrained from using direct violence against the state, gangs in the US context endure high levels of enforcement and have largely been unable to penetrate the state apparatus. Footnote 90 In turn, they rely on the cooperation of marginalized communities to avoid enforcement. In this regard, Russell Sobel and Brian Osoba argue that gangs are often seen as “protective agencies” by residents and are in direct competition with the state for their loyalty. Footnote 91 John Hagedorn has also argued that gangs form more competitive relations with the state when their racial or ethnic groups are excluded from legitimate power, where the state is unable to control space, and where gangs are located in defensible spaces. Footnote 92

These dynamics are also prevalent for urban gangs in places as diverse as Indonesia, Russia, Kenya, South Africa, China, and France Footnote 93 but are particularly noticeable in Latin America, where these types of organizations have proliferated. Footnote 94 While organized crime does not maintain uniformly competitive relations with the state, they often arise from similarly excluded, marginalized, and criminalized populations. In fact, many of these groups have formed or are connected through prison systems where inmates often experience extremely high rates of abuse and insecurity. Forming gangs or joining already existing ones is one of the primary ways for prisoners to gain access to security and scarce resources in these environments. Footnote 95 Mass incarceration and heavy-handed public security policies have only strengthened these organizations as they have expanded their power and reach through these institutions. Footnote 96 In this way, enforcement-evasion arrangements can often be a prelude to more confrontational interactions (refer to the PCC, Comando Vermelho, and El Salvador examples provided earlier).

Alliance

On the collaborative end of the spectrum, I distinguish between two primary types. The first is alliance which denotes cooperation between organized crime and the state for mutual benefit that can be tacit or formal in nature. The distinguishing feature separating types of collaborative arrangements is the degree to which these organizations are integrated into the state itself. In the case of integration, which I will detail, members of the criminal organization are directly incorporated into the state apparatus. Alternatively, in alliance arrangements there is little or no incorporation and they remain entirely separate entities yet continue to cooperate. This is often a feature of crime-state relations in areas where the state has historically exerted little control or where the state is already competing with other non-state armed groups and is either incapable or unwilling to take a more active role, preferring to use criminal groups to combat these organizations and supplement their control and authority.

Alliance is a common feature in contexts in which criminality and impunity have become rampant. In several Mexican states, vigilante organizations called Autodefensas emerged in response to the violent and brutal tactics of drug-trafficking cartels and the inability of the state to curtail violence and provide for citizen security. Initially, they maintained tacit agreements with the state that mostly prevented enforcement Footnote 97 though some of these groups eventually confronted Mexican federal police and military forces when they attempted to disarm them. Footnote 98 In northern Peru in the late 1970s, peasant patrol organizations, Rondas Campesinas, emerged in response to rampant theft of livestock and eventually evolved into an entire informal legal system. Many of these groups were supported and authorized by local state officials even as others were harassed, imprisoned, and tortured by police. Footnote 99 Finally, in Rio de Janeiro, death squads, vigilante groups, and lynch mobs initially organized in the 1970s and 1980s in response to rising levels of violence to which the state largely turned a blind eye. Footnote 100

As the preceding examples make clear, alliance arrangements often involve non-state armed groups that seek to supplement the state’s monopoly of violence. Such arrangements have been frequently documented in the United States, Brazil, South Africa, and Central America. In the American context, there is a long and controversial history of racially-motivated vigilante groups that the state has either ignored or, in some cases, endorsed directly, Footnote 101 which can also be observed in contemporary militias and border patrol groups. Footnote 102 In South Africa, vigilantism has been known to take on a similarly racial dynamic Footnote 103 but, in other cases, vigilante groups have mobilized to fight rampant criminality or assert their own particular notions of justice, Footnote 104 oftentimes with the authorization of state officials to do so. Footnote 105 Similarly, in São Paulo and numerous other urban centers in Brazil, private security firms have expanded dramatically in recent decades, engaging in a variety of extra-legal forms of violence, and often operating in dubious legal standing, which the Brazilian state has mostly chosen to ignore. Footnote 106

However, it is not just pro-government armed groups that form alliances with states. In Colombia, the BACRIM (short for bandas criminales), an assortment of former paramilitaries turned drug traffickers have formed strategic alliances with both the state and rebel forces that have facilitated their expansion to 209 of the country’s 1,123 municipalities. Footnote 107 In Central America, transnational prison gangs have engaged in high-level formal negotiations with states to reduce (or hide) their violence. Footnote 108 Finally, in the early 1990s, the Russian mafia, at least initially, faced little oversight or enforcement by the Russian state. It is estimated that this led to the emergence of an estimated 1,641 separate criminal organizations. Footnote 109 Many of these groups would go on to develop “collaborations and alliances” with the Russian state with some eventually assimilating directly into the state itself. Footnote 110 This trajectory is indicative of numerous organized crime-state collaborations. While some alliances can prove long-lasting, many are tenuous agreements that shift into either more competitive arrangements or towards integration.

Integration

The most highly collusive relationships between organized crime and states occur when these organizations make more than common cause and become intimately intertwined. In such cases, organized crime gains access to political influence, information, and networks in their efforts to expand their illicit activities and defeat rivals while also avoiding law enforcement. State actors, on the other hand, seek access to financial, electoral, and political resources that criminal organizations have accumulated. Integration is especially common in two areas within the state apparatus: political parties and the public security apparatus. These collaborations have often resulted in state institutions that, while formally under the control of the state, are subject to the pervasive influence of organized crime.

In some cases, it has more clearly been the state that exerts its influence over criminal organizations by controlling and penetrating illicit networks. This dynamic has been linked especially to the PRI’s 71-year reign in Mexico during which it was able to effectively control the country’s drug cartels. David Shirk and Joel Wallman argue that this period could be understood “not as criminals corrupting the state but criminals as subjects of the state.” Footnote 111 Others have even referred to the Mexican state during this era as a giant protection racket. Footnote 112 Mexico, however, is just one of many such cases including Manuel Noriega’s tenure as Panama’s president, Peru under Alberto Fujimori, several post-conflict regimes in Guatemala, Footnote 113 as well as other cases from around the globe that include Bulgaria, Guinea-Bissau, Montenegro, Burma, Ukraine, North Korea, Afghanistan, and Venezuela. Footnote 114 In some other cases, integration is less obviously dominated by the state as these relationships can emerge from the plata o plomo (“bullet or bribe”) choice that criminals present to state agents. Footnote 115 In Nigeria, we can observe both causal directions as politicians have recruited gangs of criminals to help them terrorize their political opponents and ensure electoral victories while, in other places, “godfathers” have the upper hand and bend politicians to their will. Footnote 116 In the end, however, the direction of causality is often difficult to identify because both the state and organized crime benefit significantly from these relationships. Footnote 117

Regardless of the direction of causality, integration arrangements are not difficult to find, especially in electoral democracies. Footnote 118 In Rio de Janeiro, a 2008 public commission found that numerous politicians in the city’s parliament were directly linked to police-connected militias, which had used territorial control and the threat of violence in hundreds of the city’s favelas to gain huge voting constituencies. Footnote 119 In Italy, the Cosa Nostra openly endorsed an estimated 40–75% of elected officials in Western Sicily from 1950 to 1992. Footnote 120 Similarly, the Neapolitan Camorra have pervasively influenced politics within the Campania region to the point that 71 separate municipal administrations have been dissolved due to rampant corruption. Footnote 121 In Guatemala’s eastern region, an estimated 70% of electoral campaign funds come from organized crime and drug traffickers while 90% of all such funds in Honduras come from similar sources. Footnote 122 In Mexico, according to a Senate commission, cartels impose their will in 195 of Mexico’s municipalities through pervasive infiltration of political institutions, maintaining what the report refers to as “total hegemony.” Footnote 123 Finally, in the 1990s and 2000s, two high-profile scandals, referred to as Proceso 8000 and Parapolítica, demonstrated the extraordinary and pervasive influence of drug-trafficking cartels and narco-paramilitary organizations throughout Colombia’s executive and legislative branches. Footnote 124

Similarly, the public security apparatus has been an institution that organized criminals have had significant success in infiltrating. In Mexico, several military generals, as many as 34 high-ranking public security officials, and even the head of the federal anti-drug agency in the 1990s were all found to be working for cartel organizations. Footnote 125 In other prominent cases, according to a Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs report, more than two dozen military generals and nearly 100 senior military officials were under investigation for links to organized crime. Footnote 126 A former Guatemalan vice president admitted that organized criminals “had gained effective control of six of the state’s twenty-two departments.” Footnote 127 In Colombia, drug-trafficking paramilitary organizations have even been referred to as the “sixth division” because they were so “fully integrated into the army’s battle strategy, coordinated with its soldiers in the field, and linked to government units via intelligence, supplies, radios, weapons, cash, and common purpose that they effectively constitute a sixth division of the army.” Footnote 128 Finally, in 2009, a cell of high-ranking Honduran police officials assassinated the country’s antidrug czar on orders from a local drug-trafficking kingpin and then, two years later, murdered another top aide. Footnote 129 These high-profile cases demonstrate the need for political science to take seriously not just the most violent episodes of criminal violence but also how these organizations have deteriorated the legitimacy and authority of the state through more collaborative means.

Conclusion

I have called for a dramatic expansion of the literature on the politics of violence to include criminal politics. By re-conceptualizing violent criminal organizations as political actors, political science can begin to appreciate the transformative and often destabilizing effects these organizations are having on numerous countries. In this effort, I have outlined an organizational approach that includes four distinct relationships between organized crime and states. Such a framework can help explain levels of violence and the nature of political authority in areas where organized crime operates and offers new insights into the relationship between violence and politics more broadly. Criminal politics should not, however, only be of interest to scholars of political violence situated at the intersection of comparative politics and international relations. Rather, as I have argued earlier, this agenda has broad applicability for understanding ongoing processes of state formation and state-building especially as they pertain to uneven outcomes of governance, development, and political accountability in many states, as well as to the diverse institutional trajectories of post-conflict societies. Criminal politics can also inform research on migration, urbanization, public goods provision, social movements, and the study of marginalized populations nearly everywhere.

Future Research

I propose three avenues of future research that build on this framework. First, we must seek to better understand the evolution of crime-state relations. Distinguishing between the arrangements that criminal actors maintain with the state is an important first step, but investigating why these relations vary over time and space is a much larger task. Existing research agendas on the Mexican drug war and other cases of confrontation have gone some distance in understanding when and where criminal organizations are more likely to engage in large-scale violence, but other comparative cases should be added to this growing body of research. In this vein, one of the primary efforts should be to improve and expand datasets that disaggregate criminal violence within and across states so that we can better understand the mechanisms leading to the emergence of violent criminal organizations, as well as when and where they confront state agents and engage in other types of violence. Footnote 130 In addition, building on existing work from civil war contexts, qualitative studies should employ novel comparative approaches to investigate the micro-dynamics of these relations. Footnote 131

Second, problematizing the relationship between different forms of violence, as well as reevaluating what constitutes these categories, should become hallmarks of the study of politics and violence. Compartmentalization has blinded us to the ways in which various forms of violence are interrelated. Recently, several political scientists have begun to break down these barriers. For instance, Elisabeth Wood and Dara Cohen have developed a research agenda focusing on how sexual violence maps onto wartime dynamics, Footnote 132 Regina Bateson has delineated the connections between wartime violence and postwar vigilantism in Guatemala, Footnote 133 and Sarah Daly has expertly outlined how former paramilitary organizations in Colombia continue to engage in many of the same types of violence for criminal ends. Footnote 134 These findings reinforce the interconnected nature of forms of violence and should encourage scholars to stop thinking of violence as occurring in self-contained silos that do not spill over into other categories.

Such innovations in our understanding of politics and violence have serious implications for post-conflict societies. Conflict resolution and reconciliation mechanisms have traditionally fixated on preventing the reinitiation of political conflict and a return to authoritarian practices but have mostly failed to recognize criminal violence as a “priority problem.” Footnote 135 Little attention has been paid to the various ways in which criminal violence can explode during and after such transitions. These issues are particularly pressing in the case of Colombia, where peace negotiations with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) have concluded and the country is on the cusp of an end to their 50-year civil war. How effectively these negotiations and future transitional justice mechanisms prevent the remobilization of FARC elements or deal with the numerous criminal groups that may step in to replace them remains to be seen, but these considerations are fundamental to lasting peace in the region. Footnote 136

While political science has only recently begun to break down the barriers between forms of violence, for some time other social science disciplines have recognized their interrelated nature. For instance, Tilly argued that all forms of collective violence, ranging from barroom brawls to military coups, are shaped by a similar set of relational processes involving groups and individuals making claims amid shifting social inequalities and in which state actors are nearly always involved as “monitors, claimants, objects of claims, or third parties to claims.” Footnote 137 To be sure, different forms of violence have distinct mechanisms leading to their occurrence, but Tilly persuasively argues for a more holistic understanding in which different forms of violence are overlapping and share underlying mechanisms. In this vein, Randall Collins has developed a micro-sociological theory of violence that focuses not on individuals or groups but on violent situations, arguing that humans are physiologically averse to violence and are often overcome with tension and fear in these situations. Footnote 138 To engage in violence, then, individuals must “circumvent the confrontational tension/fear, by turning the emotional situation to their own advantage and to the disadvantage of their opponent.” Footnote 139

Other recent contributions to this literature come from the Latin American region. For instance, Javier Auyero, Agustín Berbano de Lara, and María Fernando Berti, building on a long tradition of anthropological research in this area, Footnote 140 argue that public and private forms of violence are much more closely related than has conventionally been understood. Footnote 141 They demonstrate how collective and individual forms of violence should not be studied as “separate entities” because they are concatenated, mutually causal, and horizontally connected. Focusing on the temporal linkages between types of violence, Rodgers argues that, in the Central American context, “although past and present forms of brutality might at first glance seem very different, contemporary urban violence can in fact be seen as a structural continuation—in a new spatial context—of the political conflicts of the past.” Footnote 142 In a similar fashion, I have focused primarily on organized criminal violence, a concept that incorporates a huge range of violent acts, but which, I argue, must be understood in relation to and in conversation with other forms of organized violence.

Finally, the violence that organized crime commits is just part of the story. Many criminal organizations also engage in governance in the areas where they operate, often more effectively than the state. In this regard, further research should focus on how and why organized criminals implement their own forms of order and even, in certain cases, provide significant public goods and services to local communities. These phenomena should be studied in a comparative fashion and mapped onto crime-state relations to help us understand their variation, as well as how such criminal governance can mediate, reinforce, or deteriorate the relationship between states and their own citizens.

This is perhaps the area of research that can most fruitfully incorporate scholarship from numerous disciplines. On the one hand, the emerging rebel-governance literature has developed a framework for understanding how and why armed groups in the midst of war establish institutions to deal with civilian populations. Footnote 143 Future work on how and why criminals govern should incorporate these findings as well as the scholarship from criminology, sociology, and anthropology that delves into the nature of legitimacy and authority in areas where criminal organizations operate. Such an interdisciplinary emphasis presents significant opportunities for scholars of comparative politics to expand their empirical research to organizations and contexts normally beyond their purview (e.g., the United States) while also offering scholars of organized crime within other disciplines, some of whom have complained of an “intellectual impasse” in these fields, Footnote 144 the occasion to situate their research within a larger comparative framework and universe of cases.

Policy Implications

Criminal politics has important consequences for policy. First, criminal organizations affect political systems beyond just engaging in violent crime or illicit activities. Their accumulation of the means of violence, although rarely used to directly challenge the sovereignty of the state, has serious consequences for states. The term “criminal,” however, is often employed by political elites to delegitimize or downplay the seriousness of these organizations and their violence—a practice common for political non-state armed groups as well—and generally calls forth a set of “tough on crime” or “law and order” policies. Such categorizations, however, are self-serving and should be viewed with suspicion as they often serve to mask more serious problems of high-level corruption or, alternatively, a willingness to curtail the human rights of significant segments of a state’s citizenry. Problematizing the relationships these organizations maintain with the state and how and why they use violence is a necessary antidote to such sweeping categorizations.

Policy responses must also be attuned to the externalities of merely dealing with criminality with higher levels of enforcement and repression. The “War on Drugs” and mass incarceration policies in the United States and their export to numerous other developing countries have failed to achieve their purpose and, in many cases, only expanded and strengthened organized crime while deteriorating the rule of law. Some states have even borrowed the most repressive and violent tactics from counterinsurgency campaigns to address high crime rates, exemplified most recently in the Philippines’ crackdown on the drug trade and in Sri Lanka’s response to the explosion of criminal violence following the end to that country’s civil war. Footnote 145 Moreover, aggressively pursuing the leaders of organized crime through decapitation or kingpin removal strategies has been largely counter-productive, leading to even higher levels of violence as criminal groups fragment and leave power vacuums into which new or splinter criminal organizations insert themselves. Footnote 146 The massive social and human costs of such policies should encourage political scientists to approach these topics with not only a sense of urgency but extreme care.

The criminal politics approach, by stressing the highly-organized nature of criminal violence and the competitive state-building aspects of these organizations, should further encourage scholars and policymakers to eschew purely enforcement-oriented policies and focus on a multi-pronged approach to combating these organizations and their violence. As Kalyvas has persuasively argued, “an effective counter-criminal strategy, like an effective counterinsurgency, must include the collection of fine-grained information—rather than the blunt and indiscriminate application of military force—and the provision of competent local governance in the context of a policy of institution building.” Footnote 147 Some states have already taken such steps by implementing “hearts and minds”-style public security programs like Rio de Janeiro’s Police Pacification Units (UPPs), which mix military interventions with infrastructure improvements and community policing. Initially, the UPPs seemed like a promising path forward, though a lack of political will and massive budget deficits following Rio’s mega-events have led to the hollowing out of this flagship program. As a result, security situations in many of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas have deteriorated. Footnote 148 On the other hand, several Latin American states have experimented with negotiating directly with organized crime to reduce violence. Of course, such policies are not a panacea and face considerable obstacles. For one, according to José Miguel Cruz and Angelica Duran-Martinez, such negotiations can serve to strengthen organized crime by reducing the visibility of violence but not its actual occurrence. Footnote 149 Moreover, they argue that the success of such strategies is highly contingent on a centralized criminal leadership and continuity in state-level politics. The experience of El Salvador is instructive in this regard as violence plummeted during the country’s 18-month truce between transnational gangs but has exploded following the breakdown in negotiations, precipitating even higher levels of violence. Footnote 150

Recent drug legalization efforts have also been heralded as a path to dealing with organized crime and violence in many parts of the world. A much larger wave of legalization would, no doubt, harm the interests and revenue of many criminal organizations but it is overly optimistic to imagine that such a shift will also bring an end to repressive public security practices and mass incarceration policies. It is also likely that organized crime, comprised of highly strategic and flexible organizations, will respond to any new policy environment by expanding their illicit practices in other directions to continue to take advantage of their accumulation of the means of violence. Moreover, given the benefits of maintaining more collaborative relations with organized crime, it is unclear whether many states and their agents are truly interested in or capable of ending these arrangements. Nonetheless, it is difficult to imagine combating organized criminal violence without serious reform of existing criminal justice systems and dismantling the global drug prohibition regime.

Overall, due to the enormous variation in the types of criminal organizations, their relations with the state, and local dynamics, the criminal politics framework proposes no blanket policy prescriptions to address organized criminal violence. Effectively combating, or at least managing, these organizations and their violence will require more fine-grained policies and data collection. In this light, shifting our analytical focus to understand how and why organized crime engages with states and their agents, the mechanisms through which they have been able to pervasively influence politics, and how they have managed, in certain cases, to outcompete the state for the allegiance of local populations should encourage scholars and policymakers to pursue such research paths.

Finally, by more openly recognizing the similarities in state responses to political and criminal violence, there is significant opportunity for policy innovation. The militarization of policing and the incorporation of counterinsurgency tactics in how states deal with criminal violence (or with what they consider to be violent populations) is manifest. Footnote 151 For instance, in Rio de Janeiro, this convergence is exemplified by the military occupation of Complexo da Maré in the lead up to the 2014 World Cup. In April of that year, 2,500 Brazilian marine and army personnel, previously part of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (UNSTAMIH), were permanently stationed to this cluster of favelas. The acting general of the occupation force, while acknowledging the difference between the two contexts, pointed out their common mission: to prevent violence to allow for the development of services and infrastructure. Footnote 152 For more than a year, Brazilian soldiers carried out 24-hour patrols in armored vehicles and tanks, set up numerous security checkpoints, and engaged in countless searches, seizures, and confrontations with gang members. Despite losing their territorial hegemony, local gangs continued to operate in the area and antagonize occupation forces by transforming the structure and activities of their organizations. For their part, residents were caught between these opposing forces and sources of authority that sought their tacit if not explicit allegiance.

How can we begin to understand the dynamics involved in Maré’s occupation without seriously considering the ways in which this period resembled counterinsurgency operations in numerous conflicts around the globe? Scholars must be more cognizant of how using state-centered security approaches to address criminal violence has produced contexts that closely resemble conflict environments in which state security forces confront non-state armed groups in the midst of civilian populations. The continuing exclusion of such contexts from the political violence literature, however, will only further prevent states from crafting effective public policy to reduce violence and increase stability and order. Places like Complexo da Maré are not the exception but, increasingly, the rule. Many of today’s contested territories and battle lines are drawn around neighborhoods, city blocks, street corners, and even prison cells. We, therefore, must expand our empirical lens to such contexts if we are to have a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between politics and violence in the contemporary world.