The British Library may have been created on 27 July 1972. At least, that is the date on which the British Library Act was passed, formally dividing the institution of the Library from the British Museum.Footnote 1 The two had been together since June 1753 when the Museum was founded, its original three constitutive departments being the Department of Manuscripts, Medals, and Coins; the Department of Printed Books; and the Department of Natural Productions and Artificial Curiosities. The books were never marginalised in this organisation. Until 1898 the director had had the title of Principal Librarian. But come the late twentieth century, it no longer seemed suitable to present the two institutions as part of the same thing, and so, following an extensive administrative review process which had begun in December 1967, the new Library was founded.

The British Library was to bring together previously disparate collections and organisations. The British Museum collections would have the National Central Library, the National Lending Library of Science and Technology, and the British National Bibliography added to them, creating ‘a comprehensive collection of books, manuscripts, periodicals, films and other recorded matter, whether printed or otherwise’.Footnote 2 Having been legally established, however, this new Library remained physically within the Museum building for another quarter-century; it was not until 1997 that the flagship building still in use opened on Euston Road, the objects were divided, and the books moved into their own space. There would be further divisions to come: today around 70 per cent of the material owned by the British Library is stored in Boston Spa in Yorkshire.

This process of combination and dispersion – of things being brought together and taken apart, both institutionally and physically – is not unusual when it comes to the history of libraries. In fact, it is quite the opposite. Libraries, it turns out, are unstable things with uncertain edges. The board of the British Museum discovered this in 1972, as curators argued over which of the two newly divided institutions the illuminated manuscripts held by the Department of Oriental Antiquities ought to belong to. The Trustees of 1753 who had taken the collection of Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753) which ran to well over 70,000 objects and transformed it into the Museum ran into the same problem when it came to his collection of dried plants stored in bound paper volumes: Were these to be treated as books, or to be stored alongside the other botanical specimens? And long before his collection was bought by the nation and formalised into a public institution, Sloane himself could be found repeatedly changing his mind about how to categorise his annotated books (manuscript or print?) and where he ought to put his prints and drawings. No matter how firm a line you think you are able to draw between ‘library object’ and ‘non-library object’, it seems, the items themselves will resist you.

Despite this history of mutability, scholarship rarely grapples with the implications of the fact that such an important national institution was constructed upon shifting ground. We are resistant to the idea of the foundational library as unstable: too much relies on it. However, over the past twenty years or so the fields of bibliography and of book history have expanded and productively challenged the idea of ‘the book’; we are now accustomed to seeing it as ‘a subject that is, in the best sense, in flux’.Footnote 3 If the book is no fixed thing – if it is a broader and more porous category of object, or metaphor, than we might expect – than surely neither is the library. It is worth saying at this stage that this is less an original insight than it is an acknowledgement of the insistent refrain of rare books curators and librarians, who remind us that ‘libraries are often perceived as fixed and immutable places, but the reality could not be more different.’Footnote 4 Rather than obeying a straightforward boundary, collection spaces – including those which bear the labels ‘museum’ and ‘library’ – have long been understood by those who work within them to be things characterised by fluctuation, potential, and change.Footnote 5

Hans Sloane’s Library Collection and the Production of Knowledge takes the book historian’s idea of the book’s fluidity and asks what that means for its presence within collections. I am particularly interested in what it means to own and use books (and the differences between those relationships) and in the ways that material and institutional factors shape the way we view such items. I am interested, too, in the way that this is often characterised more by chance than anything else, and the fact that when we say chance we so often mean (in all its broad and frustratingly personal senses) materiality. Anyone who owns books knows this: the size of a book means you must shelve it in a particular place, ruining your carefully designed system. The provenance means you prioritise a copy’s manuscript annotations more than its printed content (it’s personally signed by the author!). A friend borrows a book, and it slips out of your possession forever, a ghost record in your personal library that they promise they will give back one day.

The specific case study that forms this book is that of the personal library of Hans Sloane and its close connections to the institution known as the British Library. Sloane and his collections will be properly introduced and explored in detail in Chapter 1. Before we get there, however, I want to use this introduction to briefly think through some of the strands behind what a ‘library’ collection looked like in the early modern period. This is less of a definitive history and more of a suggestive tour, through which I hope to introduce some of the main themes and questions which will run throughout the book. It could not be exhaustive: the history of libraries in the centuries leading to Sloane is a long and – if you’ll forgive the pun – storied one, with far too many branches to do full justice to here.Footnote 6 Any good, thorough account might begin with the ancient Great Library of Alexandria, infamously burnt down, which had become by the early modern period a common symbol of lost knowledge(s). Thomas Browne, for instance, remarked in his Religio Medici, ‘I have heard some with deepe sighs lament the lost lines of Cicero; others with as many groanes deplore the combustion of the library of Alexandria; for my owne part, I think there be too many in the world.’Footnote 7 The fact that the library of Alexandria was not in fact fully destroyed in the fire (which was set by Julius Caesar’s soldiers) did not matter: the image of the library is most powerful when we understand it as something material and hence susceptible.

There is an additional, slightly peculiar ambiguity in Browne’s framing here, which at least one early reader attempted to address. The manuscript copy of Religio Medici owned and annotated by Dean Christopher Wren (1589–1658), now in the National Library of Wales, introduces the word ‘bookes’ so that Browne’s sentence becomes ‘I think there be too many bookes in the world’ as opposed to ‘too many libraries’.Footnote 8 This amendment makes a certain amount of sense, pointing to the wider cultural anxiety that the introduction of print was facilitating a destabilisation of knowledge. However, it is worth resisting Wren’s reading, too. What if Browne did mean to argue that there were ‘too many’ libraries? And why might this have been a problem?

Following the expansion of print and Henry VIII’s destruction of the monasteries, which caused the movement of books and libraries out of the Church space into private ownership, the period from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries saw a dramatic re-evaluation of English libraries. Jennifer Summit has argued that it is the fifteenth century which ought to be called an ‘“age of libraries” … not because it was the first time books were systematically collected, but because it was during this time that the “library” became a place’.Footnote 9 Following her interests in the afterlives of medieval manuscripts, Summit sees this first iteration of the early modern library space as one which was as concerned with the construction and nurturing of a coherent past as it was with the advancement and creation of future knowledge. She offers the early modern library as a space for the preservation, or maybe even storage, of the past rather than one of knowledge production for the future. So, for example, in The Faerie Queene, Spenser describes Eumenestes’ library as decrepit:

Although Guyon and Arthur do in this case find something valuable in the library, it is less due to organisation or library paraphernalia than it is to happenstance. This is not a navigable library space. Instead, they both ‘chaunce’ upon a book, a word which suggests at least an element of luck:

We see something similar in Francis Bacon’s The Advancement of Learning, where libraries are not only described as ‘the shrines where all the relics of the ancient saints, full of true virtue and that without delusion or imposture, are preserved and reposed’ but explicitly contrasted with ‘new editions of authors, with more correct impressions, more faithful translations, more profitable glosses, more diligent annotations, and the like’.Footnote 12 It is not just that the library, for Bacon, looks back to the past – it is that it is a space of inertia thrown into sharp relief by the production of modern print.

By the end of the period, however loosely defined, the early modern library had become something very different. It might therefore be considered to be something coming into existence, testing and redefining its own rules. Although there were significant classical precedents for the storage and use of large quantities of texts in order to produce knowledge, the reality of what it meant to own books from the late fifteenth century onwards looked completely different to anything that had come before, as it became for the first time both affordable and feasible for individuals to purchase multiple books. There was no shared consensus on what a library was or what it contained: Samuel Pepys seems to have waited until he owned around 500 books before he felt comfortable calling his collection a library.Footnote 13 In this period, too, the idea of the ‘study’ and ‘library’ were becoming distinct, and university libraries, country house libraries, and individual libraries all took on their own unique characters and histories – replete, of course, with their own additional social anxieties.Footnote 14 We might think here about the opening of Doctor Faustus, as Christopher Marlowe’s protagonist asks for books he cannot access from his study. Kevin Windhauser has read this scene as a reflection on the contemporary anxiety that ‘overdependence on the private study’ would limit ‘the range of knowledge’ readers could encounter; he points out that Faustus uses Mephistopheles to acquire books that could easily be sourced from ‘a library or even bookshop’.Footnote 15

The mass movement of books out of (primarily Church and university) institutions and into private hands – a movement that, by end of the period, would be being partially reversed as private collectors such as Sloane, Matthew Parker, and Thomas Bodley established important public or national collections – meant that new consideration was being given to the question of what a library ought to contain, and how one ought to organise it. The resulting need to organise knowledge suddenly brought with it new metaphorical and material implications. This change can be followed with reference to the writing and production of library tracts: it is remarkable how much of this content is given to the construction of the library space in both physical and metaphorical terms, often above and beyond concerns of content. Recent critical focus has often prioritised the latter: Eric Garberson, for example, thinks about the early modern library as a space which not only allows and mediates access to, but also crucially represents, the knowledge which it embodies. In this reading, the library space is characterised by its ability to do exactly that which Henri Lefebvre considers impossible: it makes coextensive ‘knowledge objectified in a product’ and ‘knowledge in its theoretical state’.Footnote 16 It is therefore something simultaneously metaphorical and real. The prioritisation of an ‘essentially conceptual’ framework means that Garberson cannot quite prove how this idea of the metaphorical, symbolic order affected the physical layout of the real library except by arguing that it did, or may have done, or could have done – whether or not it did is deemed to be ultimately unimportant.Footnote 17 Both Summit’s and Garberson’s work is important in positioning the early modern library within the wider scholarly conversations about the spatialisation of memory within which it clearly belongs, and I do not wish to argue against it. Instead, the rest of my introduction will prioritise the other aspects of the space: its insistent materiality.

In Samuel Quiccheberg’s Inscriptiones (1565), usually considered to be the first early modern museological treatise, we are given a sense of the way in which the physical organisation of space was becoming definitive for this new set of collections. Quiccheberg offers concrete guidelines for the ideal princely collection – an encyclopaedic and organised set of objects, including (of course) a library.Footnote 18 He relies on the language of cartography and geography to describe the physical layout of the library, as if it can only be understood in relation to the physical body.Footnote 19 This focus on space is shared by Gabriel Naudé’s Advis pour dresser une bibliothèque (1627), which was translated into English by John Evelyn and which offers practical and administrative guidelines for how to order a library; its near contemporary, Claude Clement’s Musei sive bibliothecae (1628), similarly focuses primarily on the question of what architecture is appropriate to the library. Clement’s full title reveals just how interested he is in the space and ornamentation of the library beyond its practicality alone:

Building, Equipping, Care, and Use of Books in the Public and Private Museum or Library, in Four Books. With an Appendix Containing a Precise Description of the Royal Library of St. Lawrence at the Escorial, and a Laudatory Address in Allegorical Style on the Love of Literature. A Work Filled with Sacred and Secular Learning of Many Kinds; Practically and Attractively Ornamented with a Mosaic of Moral and Literary Precepts, Architectural and Artistic Suggestions, Inscriptions and Emblems, Records of Ancient Philology and Oratorical Figures. By Father Claude Clement of Ornans in the Duchy of Burgundy, of the Society of Jesus, Royal Professor of Classical Learning in the Imperial College at Madrid.Footnote 20

The difficulty here in differentiating between rhetorical ‘Ornament[s]’, ‘Mosaic[s]’, ‘Inscriptions and Emblems’, and architectural ones reveals not only how interconnected early seventeenth-century writing is with these images, but the extent to which Clement is framing the library space as a symbolic one – something to be read as much as the books it contains. Naudé’s treatise similarly reveals him to have been just as alert to the nuances and needs of space as earlier thinkers were. As Evelyn put it in his 1661 translation, ‘the consideration of the place which ought to be made choice of to correct and establish a Library in, would well take up as long a discourse as any’.Footnote 21 This location, he goes on, should ideally be ‘in a part of the house the most retired from the noise & disturbance’: the tract’s main advice is to place your library somewhere quiet, non-odorous and with ‘free light’. Windows are good; a ‘spacious Court or small Garden’ is better. (Strikingly similar is the OED’s current first definition of a library which has it as ‘a place set apart to contain books for reading, study, or reference’.Footnote 22) For Naudé, the library space is primarily considered in terms of exclusion rather than inclusion. The need for reflection which characterises the processes of reading, writing, and learning has frequently manifested in a corresponding architectural separation: books are things to be kept spatially and therefore conceptually distinct.

How true is this? Whilst we might still recognise it as an ideal model in the abstract, visiting any library today challenges this idea. Public libraries are the locations for reading and knitting groups and ‘rhyme time’ sessions for babies and toddlers; they offer internet access and are (increasingly rare) warm, inside spaces which the customer doesn’t have to pay to spend time in. My own local library now includes a weekly sexual health clinic, registration services, and a battery recycling point; librarians hold sessions on CV writing, interview skills, and language courses. University libraries have similarly taken on a range of public and social roles, incorporating coffee shops and computers and rebranding themselves as social hubs, until it can seem like the books are secondary at best. The idea of the library as a silent place solely defined by books seems outdated – if it ever existed. I want to suggest that this is not a new phenomenon, that the library might aspire to the ideal of being something ‘set apart’, but that in fact – as Sloane’s library tells us – it often bleeds out beyond its edges. Moreover, it might not always be clear whether the space you are in should be considered a library at all. So, what happens when we begin with other things?

Books in Collections, 1599–1795

If you had time to waste in London in the early eighteenth century, you might have found yourself visiting an establishment in Chelsea known as Don Saltero’s Coffee House. Part coffee-house, part barbershop, and part museum, Saltero’s – which existed into the nineteenth century, although its collection of items was dispersed between 1799 and 1825 – was founded by a man named James Salter (d. 1728), a former traveling servant of Hans Sloane. Salter had been the recipient of some of Sloane’s unwanted or surplus curiosities, which he built upon as the basis of his own collection and began displaying. Salter’s inclinations tended towards the curious and unique even though, as Angela Todd notes, they could easily have been displayed as a scientific collection had the collection’s emphasis been changed.Footnote 23 It was sold as eclectic. One printed advertisement for Don Saltero’s announces that

This technique proved very successful in attracting attention – who can resist the promise of a monster? – although not all of it was positive. Issue 34 of The Tatler, for instance, saw Richard Steele describing Saltero’s at length as being ‘the Coffee-house where the Literati sit in Council’, a collection compromised of nothing but ‘Ten thousand Gimcracks’.Footnote 25

To those familiar with the work of Arthur MacGregor and Oliver Impey, and more recently Jeffrey Chipps Smith and Surekha Davies (among many others), Salter’s collection takes the form of an immediately recognisable model.Footnote 26 It is best described as a cabinet of curiosity, or Wunderkammer, a collection of objects whose guiding principles were rarity, diversity, and uniqueness – items with a story to tell. This is the ideal collection being prescribed by Quiccheberg. The borders of such collections were porous – depending on the interests and resources of the collector, a cabinet of curiosity might include shells, taxidermied animals, works of art, and even cannons. As Barbara M. Benedict has shown, these cabinets were connected with a sense of ‘wonder’; as Ken Arnold and Paula Findlen tell us, they can also be understood as proto-museums where research was being actively undertaken and knowledge formed. Broadly defined collection spaces were key to the process of knowledge formation in the Renaissance. Nicholas Popper describes the way that ‘Wunderkammern, libraries, notebook miscellanies, and botanical gardens, [and] public and private archives in early modern Europe’ were all understood to be ‘sites of a profound commitment to empiricism and innovative modes of collecting, organizing, and retrieving knowledge’.Footnote 27 These collections can be understood as performative ones: as they represented knowledge, they simultaneously created it. They often aimed to be representative of whole systems of knowledge, microcosms of God’s universe.

Exploring the printed Catalogue of the rarities to be seen at Don Saltero’s Coffee-house in Chelsea. To which is added, a complete list of the donors thereof – extant editions of which were published between 1729 and 1795 – reveals an array of curiosities, some of which seem more plausible than others. A rhinoceros horn sits in the same glass case as a working ‘model of a mill with an overshot wheel, which works with sand’ as well as prints of a lizard, a flying squirrel, and a warrant for Charles I’s beheading; meanwhile, Cromwell’s sword, two poisoned daggers, and a curious print ‘that changes, viz. a man into a woman’ are just some of the curiosities hung ‘over the bar’.Footnote 28 Just as the collection’s reception reveals the appetite of the eighteenth-century public for curiosities, its catalogue reveals the importance of a good story in making such artefacts legible and interesting. More often than not this story is one of provenance. Even the most quotidian item can become exceptional with a good tale. An acorn is something unremarkable; ‘an acorn from Turkey’ is something potentially interesting and valuable. The value of these items – although it is perhaps notable that when they were eventually sold at auction they made very little – lies in the stories that Salter told about them, regardless of the truth.Footnote 29 Steele notes that Salter

shows you a Straw-Hat, which I know to be made by Madge Peskad, within three Miles of Bedford; and tells you, it is Pontius Pilate’s Wife’s Chamber-Maid’s Sister’s Hat. To my Knowledge of this very Hat, it may be added, that the Covering of Straw was never us’d among the Jews, since it was demanded of ’em to make Bricks without it. Therefore this is really nothing, but under the specious Pretence of Learning and Antiquity, to impose upon the World.Footnote 30

Today, this sort of collecting can seem inherently esoteric. In their much-cited work The Origins of Museums, Impey and Macgregor reflect on the difficulty of saying anything decisive about such cabinets. ‘There are no difficulties in describing what might be found in a cabinet of curiosities’, they comment, ‘but the task of seizing and classifying the philosophical bonds which linked the aims of collectors all over Europe is more problematic.’Footnote 31 Curiosity, in all its inherent expansiveness and novelty, ultimately conclusively stands only for itself – and for its collector.

This is not to say that they hold no value. Salter’s collection is particularly illuminating for my purposes because of what it reveals about books. Looking through his catalogue, we read about a ‘Turkish almanack’, ‘letters in the Malabar language’, ‘Chinese book of philosophy’, and ‘a Prayer-book, and a singing psalm-book, as 2 volumes bound together, in a very curious and uncommon manner’. Today we would probably expect to find these items in a library. In this collection, however, there is no distinction between sets of objects; an English-language Bible is kept in the same case as a snake’s egg and ‘a piece of a nun’s skin’.

When it comes to the history of libraries, studies of contemporary early modern book collectors – familiar names might include Samuel Pepys, Robert Hooke, and John Evelyn – often engage only tangentially with collectors such as Salter. Unlike such men, Salter was not a bibliophile. From what we can tell, he does not seem to have been more (or differently) interested in the books or prints or letters listed in his catalogue than he was in the dried fish, bones, or ‘Queen Elizabeth’s work-basket’. This makes it difficult to know how we can productively integrate these books into our work on library history. Sometimes I suspect there is almost a sense of offence at the idea: If he didn’t treat his interactions with books seriously, why should we? We are inclined to try to draw a firm line between two historical lineages – libraries and cabinets – that lead up to our modern-day libraries on one hand and museums on the other. Books within collections of objects (or, perhaps, books as collected objects) don’t quite fit into this dichotomy; they complicate the stories that we can tell about book collecting and reading. On the other hand, collections such as Salter’s do fit relatively neatly into the narrative about the development of museums, which has frequently located the turning point as coming at the beginning of the eighteenth century. This narrative moves us flawlessly from sixteenth-century Italian private cabinets of curiosity through the seventeenth-century establishment of professionalised institutional collections, such as the museums belonging to the Royal Society and the Oxford Ashmolean, before finally ending up at the public model of the late Enlightenment museum recognisable as the immediate forerunner to our institutions today.Footnote 32

I think that dividing early modern collections too starkly along these lines is unhelpful. It ignores what we know – what Quiccheberg tells us – which is that there was no such clear-cut historical division between museum collection and library. It also recolours such collections with the light of inevitability, making it more difficult to see the impact of decisions that could have been made differently; this will be particularly relevant when we return to the British Museum and Hans Sloane. Don Saltero’s is a helpful example because the collection no longer exists beyond its catalogue: the fact that it was dispersed allows us to grasp it as it was rather than as it is today.

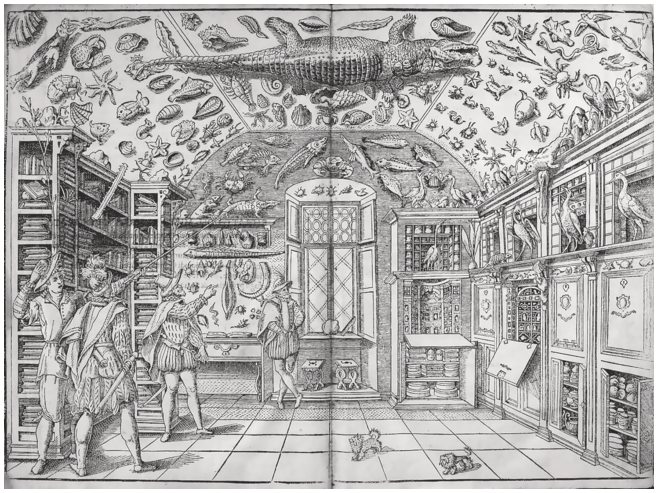

As a visual complement to the textual work done by Salter’s catalogue in re-blurring our delineations between book and object, I offer two famous illustrations of cabinets of curiosities: the engraving illustrating Ferrante Imperato’s Dell’historia naturale (1599) (Figure I.1) and the 1668 painting by Joseph Arnold of the Die Kunstkammer der Regensburger Großeisenhändler und Gewerkenfamilie Dimpfel. Looking at these and paying attention not to the crocodile on the ceiling or the strange assemblages of cannons, globes, and a lion, but instead to the position of the books in each, we can begin to see how they are treated within these assorted spaces. The sixteenth-century cabinet shown in the engraving is practically paradigmatic, the model of a Renaissance collection: the perfectly ordered specimens radiating across the ceiling, the uncannily lifelike stuffed birds perched on shelves which are themselves further subdivided into trays, the viewpoint stretching back so that it is made clear to the viewers that everything here, contained within the room, has its place. The only disruptive elements to this organised microcosm are the live ones: two tiny lion-like dogs, possibly exotic Pekingese lap-dogs, trot on the floor as if they are merely waiting for their chance to ascend into the stillness above, whilst four humans point in wonder. Or, more precisely, three humans: a fourth, possibly the owner, stands aside, his body folded in an unnatural posture. At a glance he almost looks like just another specimen. It appears that humans, too, have their place in the universal order.

Figure I.1 Frontispiece engraving from Ferrante Imperato, Dell’historia naturale (Naples, 1599).

Figure I.1Long description

An engraving of a room filled with a variety of species. The ceiling has a big crocodile in the center, with various reptiles, fishes, marine animals, and shells around and on the walls. Different birds and reptiles are arranged on shelves. Two small dogs are walking on the floor. Shelves on all sides are filled with books and other objects. Four men in royal attire are observing the room, and one among them holds a long stick to point at the species. Two stools are placed near the long window between the shelves.

Then, to one side, there are bookshelves. There is an immediate difference here: the books are not neat. One sits ajar at the top of the left-hand shelf; it seems that others have been left awkwardly piled. Unlike the static, fixed specimens, these books are to be consulted, handled, and read. It is their existence alongside – physically alongside, in the same room – the specimens which allows those specimens to be understood. In case this were not obvious, one book lies open, in between the pointing man and the leaning one; the specimen above it seems almost to point down, insisting we acknowledge the book in action. There is no internal evidence to suggest whether this book was simply one of the items of collection in use, or an organisational tool such as a catalogue or index. Perhaps the engraver was suggesting how Imperato’s book might itself be kept and used. Perhaps, more simply, the presence of the books is to be thought of not as a separate point at all but as an organic part of the cabinet: unnoticed by the visitors, overshadowed by the giant crocodile on the ceiling, but necessary, part of the work the collection is doing.

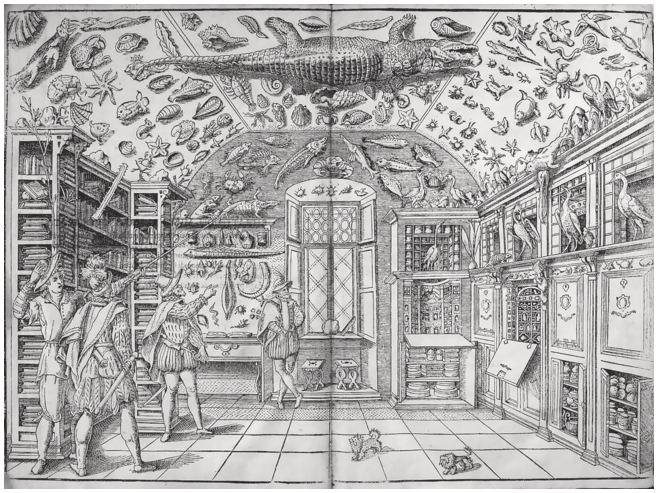

The second image was created almost seven decades later: it is a painting of the Dimpfel family’s Kunstkammer. This image might be thought of as occupying the other end of the cabinet spectrum to Imperato. Its focus is primarily art, wonder, and curiosity, rather than an attempt at a perfectly ordered, scientific-knowledge-adjacent microcosm. Cannons lie in rows opposite exquisitely displayed shells, whilst paintings, pieces of china, and globes decorate the walls. Unlike the previous image, there are no humans visible, but this is still clearly a room to be used: there is a desk in the centre of the room, books haphazardly piled, and a manuscript open, quill and ink by its side. Has someone, perhaps, been studying?

As in the woodcut, the shelved books are untidy. Some of them are shelved spine-out and others spine-in: it was common to display identifying information on the fore-edge rather than the spine until around the early eighteenth century, when book storage moved decisively upright onto shelves rather than being kept horizontally, on shelves or in chests. One small book balances precariously on top of what looks to be a vellum-bound set of folios. As with the Imperato image, the overall impression is one of disorder. The books bear all the signs of use missing from the otherwise still display of curiosities, artefacts, and memento mori which they accompany.

Thinking about these two images together suggests that books were unquestionably part of the cabinet of curiosities as it stood in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. There is no separate library ‘space’ visible in these images that we could isolate with clear or confident boundaries. As I have drawn out, however, the books within this context do sit slightly marked by difference, carefully positioned by both artists as objects to be used rather than simply looked at. They do not simply represent knowledge; that knowledge must be accessed. The implication is that in order to properly look at the curios, it is necessary also – as simultaneously as could be possible – to read about them, so that knowledge can be gleaned both first- and second-hand. In both collections, the books are peripheral and moved into the centre of the room only when in use. Moreover, both the artists are insistent that the shelved books display signs of having been noticeably, and presumably recently, used – so recently that there hasn’t been a chance to tidy them up before allowing visitors (or the viewer) to see them. There is therefore some tension between the book and the object, or at least a desire to indicate that the books are there for a slightly different (however complementary) purpose. They may be part of the collection, but that does not mean that they are the same as the other objects within it.

The Use of Books

In 1545–49, Conrad Gessner published the bibliography known as the Bibliotheca universalis – the ‘universal library’.Footnote 33 This alphabetical listing of over 10,000 titles (in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew) was Gessner’s attempt at recording and harnessing the overwhelming flurry of printed material that is so often taken today to characterise the early sixteenth century. Gessner was motivated by the simultaneous anxieties of creation and loss: the more things that were published, and the more manuscripts which were lost to natural and artificial disasters, the more the idea of someone owning everything became less and less plausible, and the more knowledge threatened to slip out of our grasp. As Paul Nelles has shown, Gessner’s work in cataloguing (both in the Bibliotheca and the later Pandectae, which cross-referenced books in terms of their content) was ‘rooted in a very dynamic relationship with the printed page’.Footnote 34 He was interested in disassembling the book for what it contained both metaphorically and literally, suggesting readers could cut up not only their own manuscript notes into slips – a common process for ordering knowledge, as Ann Blair has shown – but their printed books as well (although he was forced to acknowledge that to do so would require two copies).Footnote 35

I think that we accept the metaphor that Gessner uses in his title too easily. A bibliography is not a library. The two were related: printed bibliographies were often used as finding aids or makeshift catalogues for libraries, and the word bibliotheca has the flexibility to apply to both if we take it to mean a collection of books in any form. Theca means ‘box’ or ‘case’, so the etymological origin of biblio-theca moves from material description (‘a case of books’) to a metaphorical one (‘a collection of books’) and then – I am arguing – to a material one again (‘a library’). It is particularly common to find smaller private or institutional English libraries of the period using the 1620 Catalogus universalis librorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana, a printed catalogue of the Bodleian’s holdings arranged alphabetically by author, to record their own holdings (sometimes interleaving it, as the Bodleian itself did, and sometimes simply annotating it with their own system of shelf marks).Footnote 36 But – at least in part – it must be the case that the benefit of a bibliography is the way it overcomes the material problems of a library. A bibliography treats any given book as if it’s bibliographically perfect and as if all books are equal. It assumes that all users are equal, too. One of the important claims of this book is that part of the fluidity we now accept that makes up the productively unstable definition of what a book ‘is’ or what ‘makes’ a book can be located within an individual’s interaction with the item, and that such an interaction is mediated by its institutional or systemic presentation. Or, to put it more simply: what makes a book a book depends on both who is looking and where the thing they’re looking at is situated, how it’s talked about.

To illustrate the first part of what I mean here, I want to take a throwaway comment made by T. A. Birrell, who begins an essay discussing the composition of seventeenth-century gentlemen’s libraries with the claim that ‘this paper is concerned with reading, not collecting. If a man buys a book for any other purpose than reading it, or intending to read it, he is a collector, not a reader.’Footnote 37 As my emphases here indicate, the apparent ease of Birrell’s collector/reader dichotomy is in fact predicated around an unknowable force: somebody’s intention. It also carries the assumption that this intention is an unchanging thing. But as soon as we think about how this would play out in the real world we should begin to question this. What if the man made the purchase intending for someone else to read the book in question, perhaps at some distant point in the far-imagined future? Would it matter how distant, how unspecified? What if he bought a book intending to read it himself but only if the conditions later become possible (if, say, he managed to learn to read the language of the text fluently)? As for that phrase ‘any other purpose’ – what about books which are dipped into but perhaps not thoroughly read, such as those which are consulted, cross-referenced, annotated, and referred to over a period of time? Would that be reading? What if this man bought a book with the intention of looking primarily at the images within it, treating the text only as a secondary resource of little importance? What if he later changed his mind and read the text avidly, this time paying little or no attention to the illustrations? What if the man’s intention was simply to own that book in case a situation arose at which point it would, could, or should be read, whether by him or somebody else? Any interaction with a book requires a scale of hypotheticals. It can be readable and unreadable, usable and unusable, depending on who is looking at it and why.

Understanding this allows us to challenge one of the continuous problems that studies of individual and historic libraries run into: the fact that ownership cannot be taken as an unproblematic stand-in for reading. This has become a truism with the result that reading and ownership often seem to occupy a hazily uncertain relationship to each other. Nobody wants to make claims about things we cannot know. ‘Book-collecting behaviour does not relate in any simple way to reading behaviour; nor do records of book ownership accurately reflect access to texts. The distinction between ownership and access is particularly apparent in the early modern period because of widespread habits of reading aloud and communal reading,’ Kate Loveman writes in her study of Samuel Pepys library.Footnote 38 This is all true. On the other hand, we might point out, it is common sense that someone’s ownership of books and their reading are probably related in some way, even if one cannot (and should not) be taken to map directly onto the other. If we ignore this, we risk entrenching the idea that a study of a book’s materiality and the acknowledgement of its physical existence should be in some sense separate from any consideration of its content. We divide text from book too firmly.

Arising primarily from the work done within material text scholarship, literary criticism has moved away from the idea that reading a book functions entirely independently from any other interactions one can have with it – writing, pressing, scribbling, staining, cutting. Once again, in practice, there is a degree of common sense at work in the ideas here that mostly plays out unacknowledged in the academic literature. If you are talking about the printing or variant history of an early modern play, then a copy-specific focus on a physical edition clearly matters; if you are writing on a contemporary, mass-printed novel, it probably matters less (until something particularly interesting happens to a particular copy to make it unique, or enough time passes to make it valuable). That being said, material considerations matter even when they are not explicitly foregrounded. We all read books in the real world (and – as Lisa Maruca points out, in real human bodies), whether that’s in libraries, on screens, or through headphones.Footnote 39 And we are all affected by the way something is presented in a library search engine, whether we are aware or not of the history of decisions behind that presentation. There is a relationship between a book and its entry in a bibliography just as there is between a book and its online catalogue description, but these are not unbiased relationships.

We are becoming accustomed to the idea that neither reading nor otherwise interacting with books is an activity which happens within a vacuum.Footnote 40 Again, I would argue that this is common sense. Our use of books has always occupied a fluid, in-between state: they are sometimes primarily textual, sometimes decorative, and sometimes entirely visual. But when it comes to writing or thinking about this fact, we have been slower in being able to theorise it. This is changing as book historians become more comfortable with acknowledging the wider interactions books have in the world. For example, Jason Scott-Warren argues that ‘even the most fleeting encounter with a text (hearing it discussed, seeing it in a shop window) counts as a reading’.Footnote 41 In this case these ‘reading[s]’ are sensory encounters with a book which occur irrespective of the textual work they contain, although they are likely to be mediated by it (a Bible, for instance, is most likely to be encountered in a religious setting; a popular work of fiction might be more frequently happened across in social settings). But there is, understandably, an anxiety here with how far such thinking might go. Materiality is one thing, and we can learn things about paper technologies and binding, what ink is made of, how books were created and bought and sold, and who was buying and annotating and passing them on. How are we to think seriously, in any sort of sustained, rigorous, academic way, about the factors of chance, use, individual decisions, or common sense?

The end of the early modern period in England, broadly characterised, provides an especially productive place to think through these questions. Libraries and collections were changing in this period; the public library and museum as we know them today were still to come. By following the contents of a single collection of books from its earliest development as a private library in the late seventeenth century through to its establishment as a national, public library, we can see the construction of these rules and ideas in process, and all the features of chance – individual decisions, material circumstances – which have shaped its reception and influence today. To undertake this work, there could be no more productive or influential case study than the foundational collection of the British Library – that belonging to Hans Sloane. His collection was so vast that it is able to support a detailed exploration of the unstable early modern library space in ways which have broader importance for our understanding of early modern book objects, institutional categorisations, and the production of knowledge. Accordingly, in Chapter 1, I offer a brief biography of Sloane, beginning with a reflection on his currently unstable position within the institutions he helped found. I move on to give a history and overview of his collecting habits, and finally offer a detailed analysis of the two main tools I used to navigate the project: Sloane’s own catalogues and the British Library’s digital reconstruction of his collections.

I then move to a series of case studies, each of which approaches the question of where books and objects within the collection meet from various angles, always taking one or two items from Sloane’s collection as their linchpin. In Chapter 2, I examine horti sicci and ask how important it is for a library object to look and be bound like a book: Do collections of dried plants in folio codices belong in a library? Is a book simply a bound item, with a cover, with a spine? This chapter looks forward to the establishing of the Natural History Museum (which, similarly to the British Library, opened as a separate institution in 1881) and also engages substantially with the connections between early modern books, literature, and botany; it ends with a detailed discussion of plant names in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, showing how the library space can be extended metaphorically to support literary analysis. Continuing this botanical focus, Chapter 3 moves to a more theoretical discussion about manuscripts and annotation, asking when print is and is not an important defining feature for a library; the case study here centres around eight copies of John Ray’s Catalogus plantarum, all of which Sloane owned, and all of which offer their own manuscript additions and value. (In Jorge Luis Borges’ short story ‘The Library of Babel’ we find the claim that ‘in all the Library, there are no two identical books’; here, I ask if that is true, and think about what the value of duplication within a collection might be.)Footnote 42 Chapter 4 moves away from plants and takes as its focus foreign-language books, as I ask what it means to own books you can’t read. Here, I use the wide selection of polyglot and foreign-language texts in Sloane’s collection to think about the difference between a book that you can’t read and one which no one can read. This chapter culminates in an exploration of the various universal languages of the seventeenth century and other constructed languages, or ‘conlang’. Finally, Chapter 5 brings us back to the establishment of the British Museum, focusing on Sloane’s prints and drawings. I ask how visual information sits within the library and what challenges a picture book might offer to our primarily textual understanding of what makes a book a book. If a book is to be read, must it contain some form of text? And what happens if it is dissembled and the images removed and sent elsewhere?

As will become clear, the aim of these studies is not to give a complete overview of Sloane’s library. It would be impossible to do so. Instead, I hope to have chosen a revealing and thought-provoking set of objects that unsettle the idea of a library and shine some light into the interesting corners of Sloane’s, defining it through the concept of potential rather than exclusion. Although the chapters offer insights that will be useful to a wide range of readers across disciplines, particularly in the histories of botanical sciences, languages, institutions, and early modern literature, I will end this introduction by acknowledging that these areas of focus were chosen primarily due to my own personal interests. As we will see, I don’t think it’s unscholarly to believe that that, after all, is the point.