Introduction

In light of a growing interest in learner-centered instruction, self-assessment has become a popular topic in second language (L2) education (Butler & Lee, Reference Butler and Lee2010; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2021). Self-assessment has been used for various educational purposes, including formative assessment (Matsuno, Reference Matsuno2009) and language placement (Summers et al., Reference Summers, Cox, McMurry and Dewey2019), and has appeared in national educational policy statements (Butler & Lee, Reference Butler and Lee2010) and language proficiency guidelines (ACTFL, 2012; CEFR, 2001). Self-assessment promotes learner agency, a key aspect of self-regulated learning, by encouraging L2 speakers to reflect on their performance and potentially identify their strengths and weaknesses, thereby helping them set goals and make choices to improve their language skills (Little & Erickson, Reference Little and Erickson2015). Self-assessment is also a positive force in L2 speakers’ language performance, with those who regularly engage in self-assessment improving in many aspects of speech, including fluency, pronunciation, and connected speech processes (Kissling & O’Donnell, Reference Kissling and O’Donnell2015).

The accuracy of self-assessment is important: Over- or underconfidence in one’s performance can impact the willingness to participate in L2 interaction (de Saint-Léger & Storch, Reference de Saint-Léger and Storch2009). However, for many L2 speakers, achieving accurate self-assessment, in the sense that a speaker’s self-evaluation is aligned with the assessment provided by others (e.g., teachers, trained assessors, raters, or fellow L2 speakers), can be challenging because L2 speakers are often unaware of their strengths and weaknesses (Strachan et al., Reference Strachan, Kennedy and Trofimovich2019; Teló et al., Reference Teló, Kivistö de Souza, O’Brien and Carlet2025). For instance, when evaluating speech comprehensibility (i.e., how easy it is to understand what someone is saying), listeners seem to draw on many linguistic features in L2 speakers’ speech (e.g., pronunciation, fluency, vocabulary, grammar), whereas L2 speakers themselves tend to pay attention to fewer such dimensions (Ortega et al., Reference Ortega, Mora and Mora-Plaza2022). If self-perception does not match external assessment, an individual might overlook or misinterpret the feedback received from others or might misallocate the time and effort devoted to improving a particular skill, reducing the effectiveness of learning.

To minimize the gap between L2 speakers’ self- and other-assessments, researchers have employed various peer- and self-assessment activities, which appear to be effective (Babaii et al., Reference Babaii, Taghaddomi and Pashmforoosh2016; Chen, Reference Chen2008; Dolosic et al., Reference Dolosic, Brantmeier, Strube and Hogrebe2016). However, most of this work has targeted measures of overall L2 oral proficiency or specific features of L2 speech such as segmental accuracy and speech rate. In fact, to date, little is known about the extent to which various pedagogical interventions are effective for improving L2 speakers’ self-assessed comprehensibility. In addition, although self-assessment is a metacognitive skill that enables people to monitor, evaluate, and control their own performance (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Hale, Grainger and Stewart2020; Flavell, Reference Flavell1979), it is far from clear how metacognition is related to self-assessments of L2 pronunciation. Therefore, our goal in this study was to examine the effectiveness of a pedagogical intervention designed to help L2 speakers self-assess their comprehensibility and to explore the extent to which their metacognitive skill was relevant to the effectiveness of this intervention.

Background literature

Compared to other language skills (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2021; Matsuno, Reference Matsuno2009; Suzuki, Reference Suzuki2014), speaking can be particularly difficult for L2 speakers to self-assess (Ross, Reference Ross1998), likely because they are often unaware of their own difficulties. For instance, when L2 German speakers self-assessed their overall pronunciation accuracy, they generally agreed with expert judges (in 85% of all cases); however, the same speakers found it difficult to identify the specific segments (i.e., vowels or consonants) that were problematic for them (Dlaska & Krekeler, Reference Dlaska and Krekeler2008). L2 immersion experience and explicit pronunciation instruction can be effective in helping speakers align their self-assessments with the evaluations by external listeners. For instance, after completing a short language immersion program, L2 speakers demonstrated a stronger association between their self-assessment of oral proficiency and their actual speaking performance, measured through speech rate (Dolosic et al., Reference Dolosic, Brantmeier, Strube and Hogrebe2016). Similarly, after receiving training in phonetics, L2 French speakers showed greater alignment between their self-assessment of several segmental and suprasegmental features in their speech and the evaluation of those features by external raters (Lappin-Fortin & Rye, Reference Lappin-Fortin and Rye2014).

Although L2 speakers’ self-assessment of specific aspects of L2 speech such as individual segments or speech rate can align with external ratings, speakers may find it difficult to self-assess a global dimension of L2 speech such as comprehensibility. Comprehensibility, which refers to listeners’ perception of how easy or difficult it is for them to understand L2 speech (Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro1997), is a key dimension of L2 pronunciation (Saito & Plonsky, Reference Saito and Plonsky2019) and a useful measure of listeners’ experience with L2 speech (Kennedy & Trofimovich, Reference Kennedy and Trofimovich2019). However, considering that global, holistic constructs are difficult to self-assess compared to more specific aspects of speech (Ross, Reference Ross1998), comprehensibility may be a particularly challenging target for self-assessment, not the least because it is related to multiple linguistic dimensions of L2 speech, including segmental and prosodic accuracy, fluency, lexical appropriateness, and grammatical complexity (Saito, Reference Saito2021; Trofimovich & Isaacs, Reference Trofimovich and Isaacs2012). For example, Trofimovich et al. (Reference Trofimovich, Isaacs, Kennedy, Saito and Crowther2016) examined how closely L2 English speakers could judge their comprehensibility in relation to external raters’ evaluations. Correlational analyses showed only a weak association (r = .18) between self- and other-assessments, revealing L2 speakers’ difficulty attaining self-assessments that are calibrated with external listeners’ judgments. In a replication of that study with L2 Korean speakers (Isbell & Lee, Reference Isbell and Lee2022), although self- and other-assessments of comprehensibility showed a moderate association (r = .54), individuals at the lower end of the externally assessed comprehensibility scale tended to demonstrate a greater discrepancy between self- and other-assessments compared to more comprehensible speakers, implying that low-comprehensibility speakers are especially prone to miscalibrated self-assessment.

Repeated practice of engaging in self-assessment appears to be a useful technique in helping L2 speakers align their self-assessments with external evaluations (Kissling & O’Donnell, Reference Kissling and O’Donnell2015; Lappin-Fortin & Rye, Reference Lappin-Fortin and Rye2014). For instance, Strachan et al. (Reference Strachan, Kennedy and Trofimovich2019) asked L2 speakers to perform two versions of a speaking task and self-assess their comprehensibility after each performance. Whereas there was no relationship between the speakers’ self- and other-assessments after the first task (r = .10), a weak association emerged after the second task (r = .40), likely because the speakers developed some awareness of their performance through repeated task practice and self-assessment. With a longer gap between the initial and subsequent self-assessment, Saito et al. (Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Abe and In’nami2020) showed a similar tendency for instructed Japanese learners of L2 English, such that there was no relationship between self- and other-assessed comprehensibility at the beginning of an academic term (r = .07), but a weak-to-medium association emerged by its end (r = .31). Notably, the learners who had engaged in more extracurricular L2 practice showed greater convergence between self- and other-assessed scores, suggesting that individual differences in speaker profiles may moderate the extent of alignment between self- and other-assessed comprehensibility.

Another useful intervention to help L2 speakers improve the alignment between self- and other-assessment is peer-assessment, which is believed to facilitate L2 speakers’ task engagement and contribute to “greater understanding of the nature and process of assessment” (Hansen Edwards, Reference Hansen Edwards and Kunnan2013, p. 734). In a Taiwanese EFL university course, Chen (Reference Chen2008) asked L2 speakers to make oral presentations, and their performance was evaluated twice by speakers themselves, peers, and the teacher on content, language, delivery, and manner (see also Patri, Reference Patri2002). Although self- and teacher-assessments initially diverged, the gap between self- and teacher-assessment narrowed after the speakers performed repeated peer-assessments, while also receiving feedback from peers and teachers over time. In an initial demonstration of the value of peer-assessment for L2 comprehensibility, Tsunemoto et al. (Reference Tsunemoto, Trofimovich, Blanchet, Bertrand and Kennedy2022) showed that L2 French speakers who engaged in peer-assessment during a 15-week speaking course showed greater alignment between their self-ratings of comprehensibility and the assessments provided by external raters compared to those L2 speakers who only self-assessed their performance repeatedly. These findings point to potential benefits of peer-assessment for helping L2 speakers narrow the gap between self- and other-assessments of L2 pronunciation.

Although pedagogical interventions such as those focusing on self- and peer-assessment may help L2 speakers align their self-evaluations of pronunciation skills with those provided by external raters, the extent of this alignment might depend on inter-individual differences among speakers. In their seminal work, Kruger and Dunning (Reference Kruger and Dunning1999) argued that over- or underconfidence in evaluating one’s performance (i.e., being overly lenient or strict) is caused by a lack of metacognitive skill. Metacognition refers to “knowledge concerning one’s own cognitive processes and products or anything related to them” (Flavell, Reference Flavell and Resnick1976, p. 232) and broadly includes a person’s understanding of their own cognitive abilities (metacognitive knowledge) and their use of various cognitive strategies (metacognitive regulation) such as planning, monitoring, and evaluation (Brown, Reference Brown and Glaser1978). In L2 research, metacognition has been examined extensively in relation to self-regulated learning and how it affects general learning outcomes (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Hale, Grainger and Stewart2020) or language performance in reading (Carrell, Reference Carrell1989), listening (Goh & Hu, Reference Goh and Hu2014; Vandergrift et al., Reference Vandergrift, Goh, Mareschal and Tafaghodtari2006), and vocabulary (Teng & Zhang, Reference Teng and Zhang2021). What remains unclear, however, is whether metacognition is relevant to L2 speakers’ self-assessment of various measures of pronunciation, especially their self-assessed comprehensibility.

Even though metacognition, which has typically been examined through participant self-reports, is a key ingredient of learning across multiple domains (see Craig et al., Reference Craig, Hale, Grainger and Stewart2020, for a review), there have been mixed findings regarding the metacognition–self-assessment links (Schraw, Reference Schraw1994). For instance, in some studies, a measure of metacognitive regulation predicted the extent to which students’ self-assessed scores were aligned with their actual academic test performance (Sperling et al., Reference Sperling, Howard, Staley and DuBois2004). In other research, however, neither metacognitive knowledge nor regulation was associated with how closely students’ self-assessments matched their academic performance (Schraw & Dennison, Reference Schraw and Dennison1994). More recently, focusing on vocabulary learning, Jang et al. (Reference Jang, Lee, Kim and Min2020) investigated how metacognition was related to the alignment between participants’ self-assessment of their performance and their actual scores on a vocabulary test. The researchers asked 75 Korean university students to study 44 word pairs in a language that they did not know (Hebrew). Taking part in three learning cycles, the students first attempted to memorize each presented word pair; afterwards, as the first word from each pair was shown on a computer screen, they estimated how well they remembered the associated target word and then provided it. The students’ self-assessments became more accurate over the learning cycles, and their metacognitive knowledge, which was assessed through a metacognitive awareness inventory (Schraw & Dennison, Reference Schraw and Dennison1994), was significantly associated with the accuracy of their self-assessed word recall, suggesting a possible link between metacognition and self-assessment.

The current study

Self-assessment has received extensive attention from both researchers and practitioners, likely because it enhances L2 speakers’ autonomy while enabling them to reflect on their performance and diagnose their strengths and weaknesses. Although L2 speakers’ self-assessment of specific skills, such as segmental and prosodic features, may show alignment with other-assessments (Dlaska & Krekeler, Reference Dlaska and Krekeler2008), especially after extensive training (Dolosic et al., Reference Dolosic, Brantmeier, Strube and Hogrebe2016) or explicit instruction (Lappin Fortin & Rye, Reference Lappin-Fortin and Rye2014), global dimensions of L2 speech, including comprehensibility, are difficult for L2 speakers to self-assess in the absence of targeted interventions (Saito et al., Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Abe and In’nami2020; Trofimovich et al., Reference Trofimovich, Isaacs, Kennedy, Saito and Crowther2016; Tsunemoto et al., Reference Tsunemoto, Trofimovich, Blanchet, Bertrand and Kennedy2022). In fact, the extent to which various pedagogical interventions, including peer-assessment practice, can help L2 speakers align their self-assessments with external judgements is underexplored. Finally, given that metacognition contributes to how well people evaluate their performance (Jang et al., Reference Jang, Lee, Kim and Min2020; Kruger & Dunning, Reference Kruger and Dunning1999), it is also unknown whether and to what degree metacognition moderates the effectiveness of pedagogical interventions targeting L2 speakers’ self-assessment.

To address these research gaps, we examined the effects of peer-assessment practice on the alignment between self-assessed and externally assessed comprehensibility. Whereas previous studies have targeted relatively extensive pedagogical interventions, for example, ranging in length from one month (Tsunemoto et al., Reference Tsunemoto, Trofimovich, Blanchet, Bertrand and Kennedy2022) to one academic term (Saito et al., Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Abe and In’nami2020), we focused on a shorter intervention, which is more feasible to implement in a classroom or through self-study, investigating its impact on L2 speakers’ self-assessment of comprehensibility. Furthermore, while self-assessment can be affected by various individual differences, such as L2 speakers’ language background (Trofimovich et al., Reference Trofimovich, Isaacs, Kennedy, Saito and Crowther2016), attitudes toward pronunciation (Isbell & Lee, Reference Isbell and Lee2022), and linguistic experience (Saito et al., Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Abe and In’nami2020), general metacognitive skills likely contribute to the quality of L2 speakers’ self-assessment (Jang et al., Reference Jang, Lee, Kim and Min2020; Schraw & Dennison, Reference Schraw and Dennison1994). Understanding the role of metacognition in self-assessment can thus offer insights into how L2 speakers develop skills needed for accurate self-assessment. Therefore, our goal in this study, conducted in an L2 English academic context, was to explore the extent to which a pedagogical intervention focusing on peer-assessment helps L2 speakers align their self-assessment of comprehensibility with external evaluations and to understand the relationship between L2 speakers’ metacognition and their self-assessment. This study was guided by the following questions:

-

1. Does engaging L2 speakers in a brief peer-assessment activity (through a stimulated recall procedure) lead to more calibrated self-assessments relative to the situation where L2 speakers only engage in repeated self-assessment?

-

2. Does metacognition predict the extent to which L2 speakers calibrate their self-assessments with those provided by external raters?

On the basis of prior research (Babaii et al., Reference Babaii, Taghaddomi and Pashmforoosh2016; Chen, Reference Chen2008; Patri, Reference Patri2002), we hypothesized that peer-assessment would have a stronger contribution than repeated self-assessment to narrowing the gap between L2 speakers’ self- and other-assessments. On the one hand, repeated self-assessment on its own does not always help university students align their judgments of academic performance with other-assessments (Lew et al., Reference Lew, Alwis and Schmidt2010). On the other hand, even when repeated self-assessment has been shown to lead to greater alignment between self- and other-assessments (Saito et al., Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Abe and In’nami2020; Strachan et al., Reference Strachan, Kennedy and Trofimovich2019), the resulting associations were weak at best, suggesting that repeated self-assessment alone (i.e., outside instruction, guidance, or additional exposure) may not be sufficient to minimize the gap between self- and other-assessments (Tsunemoto et al., Reference Tsunemoto, Trofimovich, Blanchet, Bertrand and Kennedy2022). Therefore, peer-assessment practice—operationalized here through an explicit focus on comprehensibility during a stimulated recall interview—was considered to be particularly effective as a way of helping L2 speakers become aware of their comprehensibility. Finally, despite the lack of systematic investigation of metacognition in relation to self-assessment of L2 pronunciation, following from prior research on general academic achievement (Schraw & Dennison, Reference Schraw and Dennison1994) and L2 vocabulary learning (Jang et al., Reference Jang, Lee, Kim and Min2020), we expected that L2 speakers’ metacognition would be related to their self-assessment, where stronger metacognitive skills predict more calibrated self-assessments.

Method

L2 Speakers

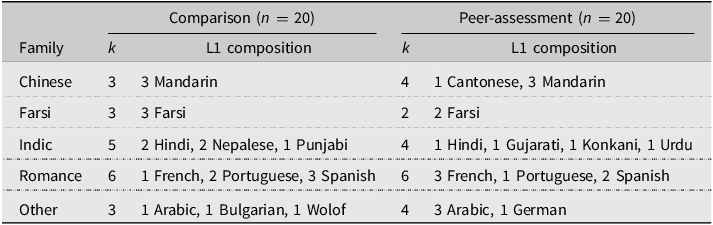

Participants (henceforth, L2 speakers) included 40 undergraduate (25) and graduate (15) international students from English-medium universities in Montreal studying various disciplines, including biology/chemistry (5), business (5), computer science (3), economics and marketing (11), engineering (5), fine arts (2), language and education (4), psychology (3), culture and religion, and urban studies (1 each). The speakers were recruited through pre-existing social media groups, email lists, and snowball sampling to ensure that they represented several different first language (L1) backgrounds, such as Chinese (e.g., Cantonese, Mandarin), Farsi, Indic (e.g., Hindi, Punjabi), and Romance (e.g., French, Spanish), so that the study’s findings could be generalized to a diverse group of L2 speakers. As degree-seeking students, the speakers had met the minimum English language requirement for admission to their university, which was a TOEFL iBT score of 75 (or equivalent). The 40 speakers were randomly assigned to two equal groups, which differed in the type of instructional treatment they received (baseline comparison vs. peer-assessment). Both groups included similar female-to-male ratios (14:6, 15:5) and a similar proportion of undergraduate versus graduate students (13:7, 12:8). In terms of the speakers’ L1 backgrounds, as shown in Table 1, the two groups were roughly matched in the frequency and distribution of various linguistic backgrounds represented in each group.

Table 1. L2 Speakers’ language backgrounds by group

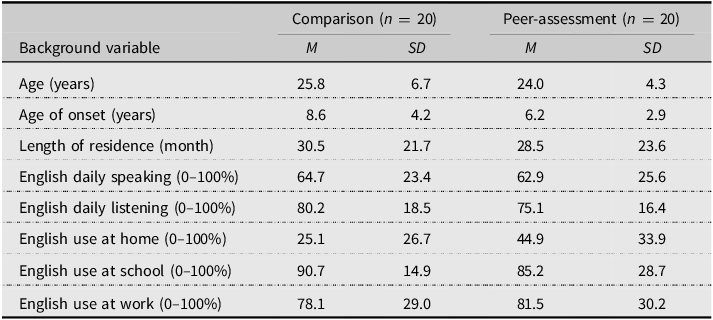

As summarized in Table 2, the two groups were also balanced in terms of various other speaker characteristics, including their age, age of onset for learning English, length of residence in Canada, and daily English use.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for L2 Speakers’ background characteristics

Experimental design

As shown in Figure 1 illustrating the study design, the two groups of L2 speakers engaged in similar experimental tasks, which included the recording of a speaking performance, providing the initial self-assessment of that performance (first self-assessment episode), completing a language background questionnaire and a metacognitive awareness questionnaire, and finally providing the final self-assessment of the same performance (second self-assessment episode) spending 40–60 minutes to complete all tasks. However, only the peer-assessment group engaged in a peer-assessment intervention through stimulated recall, whereas the comparison group completed a filler task. Thus, both groups provided two self-assessments of their performance, yet only the peer-assessment group additionally engaged in peer-assessment practice, which allowed for examining the effect of peer-assessment practice relative to the effect of repeated self-assessment (in the comparison group). The metacognitive awareness questionnaire was administered alongside the background questionnaire for practical reasons, namely, to create a reasonable time gap between the first and the second self-assessment episode without introducing additional study-irrelevant filler tasks.

Figure 1. Experimental design.

Target intervention

For the peer-assessment activity, the L2 speakers in the peer-assessment group listened to, evaluated, and discussed three preselected comparable audios recorded by the speakers in the comparison group (M = 55.7 seconds, SD = 9.5), who completed the experimental procedure first. The audios included responses to one of two task prompts (advertisement or motivation); the prompt audio chosen for discussion was different from that used by the speakers themselves for self-assessment (see below), to ensure that the speakers in the peer-assessment group oriented toward linguistic features relevant to comprehensibility rather than, for example, engaged in a comparison of the content of their own recording to that of their peers. The three chosen audios per prompt each illustrated a different comprehensibility level (low, mid, high), as determined by the researcher, and included various strengths (e.g., lack of segmental substitutions, fluent utterance delivery) or weaknesses (e.g., word stress errors, inappropriate intonation contours, undue pausing, slow delivery), depending on the level. Each of the three audios was also recorded by a speaker from a different L1 background (Arabic, Spanish, Wolof in response to the advertisement prompt; Bulgarian, Farsi, Hindi in response to the motivation prompt) to increase variability in speakers’ exposure to various linguistic dimensions relevant to comprehensibility.

The intervention involved two steps. In the first step, the speakers in the peer-assessment group listened to each audio and evaluated it for comprehensibility using a 100-point sliding scale after receiving a brief reminder about this construct. The scale did not contain numerical markings (to capture impressionistic judgments about speech), but the endpoints were clearly labeled (0 = hard to understand, 100 = easy to understand). Although comprehensibility has been typically measured through Likert-type scales (e.g., Isbell & Lee, Reference Isbell and Lee2022) and continuous scales with different resolutions such as 100 points versus 1000 points (e.g., Saito et al., Reference Saito, Trofimovich and Isaacs2017; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Trofimovich, Chen and McDonough2022), we chose the 100-point scale because it felt both intuitive to participants and matched the scale used in the metacognitive awareness questionnaire (see below). Because previous work revealed little impact of scale resolution on comprehensibility ratings (Isaacs & Thomson, Reference Isaacs and Thomson2013), this methodological decision was unlikely to have undue influence on our findings.

In the second step, the speakers engaged in a stimulated recall session with the researcher. They first summarized their initial impressions about the comprehensibility of the speaker in the audio. They then listened to the same audio again and explained specific reasons for their evaluation by pausing the recording to indicate what they were thinking about at each chosen location. For instance, the speakers commented about various linguistic features (e.g., verb tenses, hesitations) that impacted their assessment and more generally discussed speech content (e.g., information order) or the extent of their comprehension (e.g., how well they understood the speaker until a specific location in the audio). When the speakers did not spontaneously pause the audio, the researcher prompted them to stop and share their thoughts where there was a feature with relevance to comprehensibility (e.g., mispronunciation, filled pause, and grammar error), which generally happened 1–3 times per audio. The speakers were allowed to replay each audio as many times as necessary to recall their thoughts, and only three listened to each audio more than once. Of the three speakers who replayed the audio, one did not make any comments during the first listening, whereas the remaining two wished to hear a problematic sentence again before commenting on it. The same two steps were repeated for the remaining two peer-assessment audios, which were presented to the speakers in two counterbalanced orders. On average, the speakers made 8.3 comments (SD = 2.4) during the stimulated recall session, with approximately five comments (SD = 5.0) initiated by the speakers themselves. Because stimulated recall was used to orient the speakers toward various features of comprehensible speech, a detailed analysis of stimulated recall comments falls outside the scope of this study and these comments are not discussed further.

Instead of the peer-assessment activity, the speakers in the comparison group engaged in a filler task (a reading comprehension activity), selected to avoid exposing the speakers in this group to aural input. The speakers read a 604-word text adapted from a sample TOEFL practice test about meteorite impact and dinosaur extinction and then answered five multiple-choice comprehension questions related to the passage. For both groups, there was a short gap of approximately 15–20 minutes that separated the first and the second self-assessment episode. This gap lasted on average 20.0 minutes (SD = 4.3) in the peer-assessment group and about 15.6 minutes (SD = 5.2) in the comparison group.

Self-assessments

All L2 speakers, regardless of their group assignment, completed the same academic speaking task used for self-assessment and external assessment (see below). In this task, which was adapted from Tekin et al. (Reference Tekin, Trofimovich, Chen and McDonough2022), the speakers first read a 200-word text about either advertisement or motivation and then gave a one-minute oral summary of the text in response to a prompt (Appendix A). The speakers in both groups were assigned to each text randomly, with the only constraint that half of the speakers per group recorded their summary in response to the advertisement text, while the other half provided a summary for the motivation text. The two texts were comparable in word count (193 vs. 197), type–token ratio (0.52 vs. 0.56), and Flesch Reading Ease estimate (33.92 vs. 29.12), a readability metric assessed through Coh-Metrix (Graesser et al., Reference Graesser, McNamara and Louwerse2004). The speakers first spent 2 minutes reading the assigned text (with notetaking allowed), then had 30 seconds to prepare their response based on their notes before recording their summary. They were instructed to address the researcher as their interlocutor and were told that she would carefully listen to them without providing any verbal or nonverbal feedback. To provide self-assessments during the first and the second assessment episodes, the speakers listened to their own summary and self-assessed their performance for comprehensibility using the same 100-point sliding scale (0 = hard to understand, 100 = easy to understand). The initial slider position was always in the middle (corresponding to the rating of 50), and the speakers listened to the entire file before providing their assessment, with only one listening allowed.

Questionnaires

Besides the target intervention and the audio recordings used for the first and the second self-assessment, other materials included a background questionnaire and a metacognitive awareness questionnaire. The background questionnaire (Appendix B) elicited the speakers’ language and demographic profile (e.g., age, gender, field of study, languages known). The metacognitive awareness questionnaire (Appendix C) was a short version of the metacognitive awareness inventory (Harrison & Vallin, Reference Harrison and Vallin2018) composed of 19 items drawn from the original 52-item survey (Schraw & Dennison, Reference Schraw and Dennison1994). This instrument, which was validated in a sample of 622 participants using an iterative confirmatory factor analysis and item-response modeling, showed a better model fit but yielded comparable findings to those obtained from the full survey (Harrison & Vallin, Reference Harrison and Vallin2018). Of the 19 questionnaire statements, eight items targeted the knowledge dimension of metacognitive awareness (e.g., “I can motivate myself to learn when I need to”), and 11 items targeted the regulation dimension of metacognitive awareness (e.g., “I think about what I really need to learn before I begin a task”). Following the original instrument, which contained 100-millimeter bipolar scales (Schraw & Dennison, Reference Schraw and Dennison1994), the 19 statements were accompanied by 100-point scales anchored by endpoint descriptors (0 = not at all typical of me, 100 = very typical of me) so that all instruments in this study elicited ratings through scales of similar length.

Procedure

The speakers scheduled a one-hour individual meeting with the researcher (via Zoom) during which they completed an online survey administered through LimeSurvey (https://www.limesurvey.org). After checking the audio recording quality of the speaker’s computer, the researcher explained the purpose of the study, providing instructions for the summary task, along with the definition of comprehensibility (with examples). The speaker then listened to two additional recordings (30 seconds each) and practiced using the comprehensibility rating interface (2 minutes). Next, the speaker completed the speaking task, recording their summary of the assigned text through an online recorder, then downloaded the audio file to their own computer and shared it with the researcher via Zoom (6 minutes). Following this, the speaker listened to their own performance and provided the first self-assessment (2 minutes). After finishing the peer-assessment activity or the filler task, depending on the group (15–20 minutes), the speaker completed the background questionnaire, followed by the metacognitive awareness questionnaire (5 minutes). Finally, the speaker listened to their summary again and self-assessed their performance through the same scale, providing the second self-assessment (2 minutes). At the end of the session, the speaker answered a short debrief survey about their self-assessment experience (1 minute) and received instructions about how to claim remuneration for their participation ($25 CAD).

External assessments

The L2 speakers’ performance was assessed by 30 external raters (M age = 23.3, SD = 2.8), all recruited from the same student population as the speakers and presumed to represent their potential interlocutors. The raters (21 females, 9 males) were screened to exclude those with prior experience of teaching English or taking linguistic courses, so as to recruit a sample of nonexpert raters (Isaacs & Thomson, Reference Isaacs and Thomson2013; Saito, Reference Saito2021); however, linguistic diversity was encouraged, to emulate the composition of the student body in the English-medium universities from which the L2 speakers were recruited. The raters thus represented 15 L1 backgrounds, including English (12), Mandarin (3), Arabic, Spanish (2 each), Cantonese, Bengali, Farsi, French, Gujarati, Hindi, Nepalese, Russian, Slovak, Turkish, and Urdu (1 each). They had lived in Canada for about 12 years (SD = 9.6) and were pursuing undergraduate (24) or graduate (6) degrees in non-education and nonlinguistic disciplines (e.g., computer engineering, human relations, science, sociology, software engineering, neuroscience, and psychology). The L2-speaking raters had met the minimum English language requirement for admission to their university, which was a TOEFL iBT score of 75 (or equivalent).

The raters evaluated the speakers’ recordings in individual sessions through the same online interface used by the speakers for self-assessment. The 40 recorded audios were presented to the raters as full-length files to make the audio stimuli identical between the speakers and the external raters. The audios were comparable in length between the comparison group (M = 58.7 seconds, SD = 6.7) and the peer-assessment group (M = 57.4 seconds, SD = 7.1), and they were not edited in any way except removing dysfluencies (e.g., uhm) before the onset of speech and normalizing all files for peak amplitude (loudness). The raters first read the same definition of comprehensibility given to the speakers, then practiced assigning the ratings using two additional recordings (also used for practice by the speakers) before proceeding to rate the 40 target recordings presented in two sets defined by prompt type (advertisement, motivation), with the order of the two sets counterbalanced across the raters and a 5-minute break introduced between them. The recordings, which were presented in unique random order within each set, appeared as embedded audio files with a 100-point sliding comprehensibility scale under each file (i.e., same scale used by the speakers). As with self-assessments, the raters listened to the entire file before providing their rating, and only one listening per audio was permitted. After finishing the rating task, the raters completed a rater background questionnaire (Appendix D) and received instructions about how to claim remuneration for their participation ($30 CAD).

Data analysis

Following Isbell and Lee (Reference Isbell and Lee2022), to examine the alignment between self- and other-assessments of L2 comprehensibility, overconfidence and miscalibration scores were computed per speaker for the two self-assessment episodes. Overconfidence was derived by subtracting a rater-assessed score from the speaker’s self-assessed score. An overconfidence score of 0 indicates perfect alignment between self- and other-assessed comprehensibility. Scores above 0 imply overconfident self-assessment (with speakers providing higher ratings than external raters), whereas scores below 0 designate underconfident self-assessment (with speakers underestimating their comprehensibility relative to external assessments). Miscalibration was calculated by subtracting a rater-assessed score from the speaker’s self-assessment but expressing the value in absolute terms (i.e., regardless of whether the speaker is over- or underconfident). An ideal miscalibration score is 0, which indicates perfect alignment between self-assessments and external ratings, whereas values away from 0 imply increasing differences between self- and other-assessments, regardless of their directionality. Thus, the two scores provide complementary but distinct information, where miscalibration encompasses the magnitude of differences, whereas overconfidence additionally captures their directionality.

In terms of the metacognitive awareness inventory, Cronbach’s alpha was computed to check item consistency for each subscale. For the metacognitive knowledge subscale, the value was sufficiently high (α = .72) and generally comparable to the .80 reliability reported previously (Harrison & Vallin, Reference Harrison and Vallin2018); however, for the metacognitive regulation subscale, the value was poor (α = .48) and considerably lower than the previously reported estimate of .84 (Harrison & Vallin, Reference Harrison and Vallin2018). Therefore, in light of low reliability of the regulation subscale, only the knowledge subscale was used in further analyses, with mean scores computed per speaker by averaging their responses to the eight subscale items.

To examine the extent to which the peer-assessment intervention was associated with the alignment between the speakers’ self- and other-assessments, we computed a mixed-effects model in R (version 4.4.2, R Core Team, 2024) using the lme4 package (version 1.1–36, Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015). Because the research question focused on the magnitude of differences between self-assessed and externally assessed L2 comprehensibility and because the overconfidence and miscalibration scores provided partially overlapping information, with both measures yielding similar findings, we used only the miscalibration scores for statistical analyses. The outcome variable was the miscalibration scores from the second self-assessment (2nd miscalibration), with group dummy coded as a binary variable (0 = comparison, 1 = peer-assessment) and metacognitive knowledge used as a continuous variable, both entered as fixed-effects predictors. Because the speakers might have differed in extent of miscalibrated self-assessment as a function of their initial performance level (Isbell & Lee, Reference Isbell and Lee2022; Trofimovich et al., Reference Trofimovich, Isaacs, Kennedy, Saito and Crowther2016), we entered the miscalibration scores from the first self-assessment (1st miscalibration) as a fixed-effects predictor. To explore whether the treatment effect depended on joint contributions of the speakers’ group assignment and their initial miscalibration performance or metacognitive knowledge, we also included two interaction terms: between participant group and 1st miscalibration and between participant group and metacognitive knowledge.

Lastly, to capture additional pre-existing differences in participant experience, the amount of the speakers’ daily English speaking and listening, their English use (at home, at school, at work), and their length of residence in Canada were entered as control covariates. These variables served to account for potential differences in language exposure, especially because exposure appears to moderate the degree to which L2 speakers adjust their self-assessment relative to external evaluations (Saito et al., Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Abe and In’nami2020). In addition, speakers (40) and raters (30) were included as random-effects predictors. Whereas untransformed miscalibration scores served as the outcome variable, all continuous predictors were z-transformed. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were examined to check the statistical significance of each parameter (interval does not cross zero). The raw data and the model code are available at https://osf.io/pag7b/. Whereas the descriptive statistics were aggregated per speaker, mixed-effects models were fit using the full rating dataset.

Results

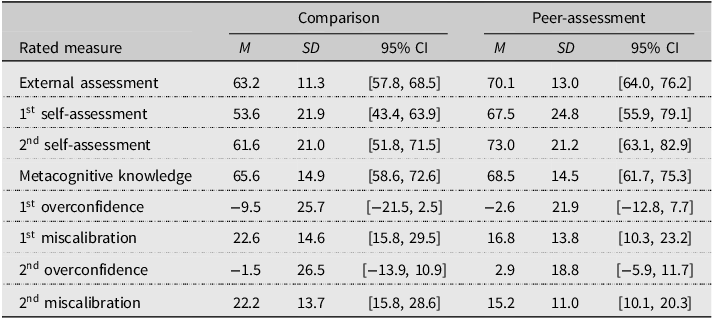

As summarized in Table 3, which provides descriptive statistics for the speakers’ comprehensibility ratings (speaker-level averages and aggregated across raters), the external raters judged the speakers to be moderately comprehensible with a mean score above the scale midpoint (on a 100-point scale), with a considerable range in both the peer-assessment group (41.23–88.63) and the comparison group (43.27–85.10). The speakers in the peer-assessment group received higher comprehensibility ratings than the speakers in the comparison group (M = 70.1 vs. 63.2). The speakers in the peer-assessment group also self-evaluated their comprehensibility higher than the speakers in the comparison group (M = 67.5–73.0 vs. 53.6–61.6). In terms of metacognitive knowledge, the speakers in the peer-assessment group had higher metacognitive knowledge scores than the speakers in the comparison group (M = 68.5 vs. 65.6), by a mean of 2.9 points on a 100-point scale.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics for comprehensibility ratings, metacognition scores, and overconfidence and miscalibration scores

In terms of the overconfidence scores (summarized in Table 3 and illustrated graphically in the top left panel of Figure 2), the speakers whose comprehensibility was assessed by the external raters roughly as high-intermediate (around 75 on a 100-point scale) were aligned in their self-assessments with the ratings provided by the external raters (overconfidence = 0). However, the speakers at the lower end of the comprehensibility scale tended to overestimate their performance, whereas those at the upper scale end tended to underestimate their comprehensibility relative to the external raters’ assessments. The miscalibration scores, which show absolute differences between self- and other-assessments (plotted in the top right panel of Figure 2), highlighted this U-shaped relationship between the speakers’ self- and other-assessments, where the magnitude of the self-assessment gap increased as scores drifted away from 75. Even though both groups followed a similar U-shaped pattern, the speakers in the peer-assessment group showed a stronger negative association between their miscalibration scores and the external raters’ evaluations (r = −.43) than the speakers in the comparison group (r = −.20). Put differently, the speakers with higher externally assessed comprehensibility ratings tended to show more calibrated self-assessments, and this relationship was more pronounced in the peer-assessment than the comparison group. Finally, the speakers who miscalibrated their performance in the first assessment episode continued to do so in the second episode, as indicated by the linear patterns in the two bottom panels of Figure 2 (with the overconfidence and miscalibration scores plotted in the left and right panels, respectively).

Figure 2. Scatterplots illustrating the relationship between externally assessed comprehensibility and speakers’ 2nd overconfidence and miscalibration scores (top panels) and between 1st and 2nd overconfidence and miscalibration scores (bottom panels), plotted separately by group (comparison, peer-assessment), with the boxplots representing the median and the interquartile range, and the smooth line and standard error estimates (shaded) showing the best-fitting trendline.

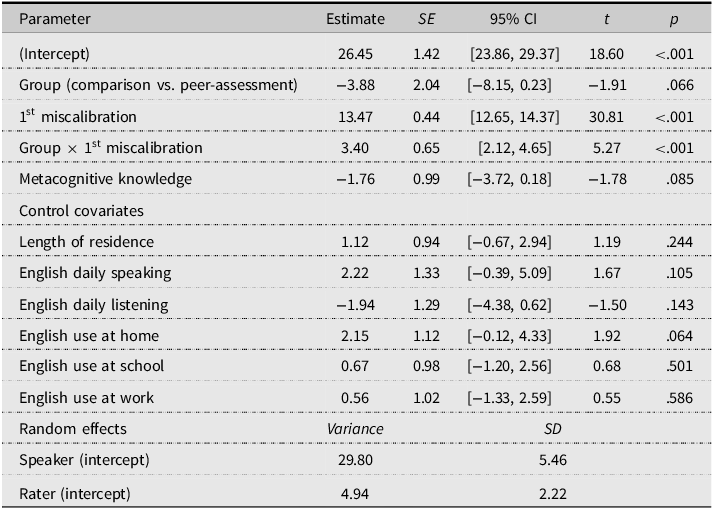

Table 4 summarizes the output of the final mixed-effects model examining the speakers’ miscalibration scores from the second self-assessment episode as a function of group (comparison vs. peer-assessment), 1st miscalibration, and metacognitive knowledge. The speakers’ miscalibration scores were qualified by a significant group × 1st miscalibration interaction, suggesting that the effect of group depended on the speakers’ initial performance. The inclusion of this interaction term resulted in an improved model fit relative to the model excluding this interaction, χ2(1) = 27.76, p < .001. However, the group × metacognitive knowledge interaction was not significant, suggesting that the effect of metacognitive knowledge was similar across the two participant groups. Because this interaction term resulted in no additional gain to model fit, χ2(1) = 0.08, p = .784, this interaction was removed from the analysis.

Table 4. Summary of mixed-effects model outcomes for 2nd self-assessment miscalibration

Note: 95% CIs were calculated through 1,000 bootstrapped iterations.

The significant group × 1st miscalibration interaction is illustrated in Figure 3. In terms of their predicted performance in the second self-assessment episode, the peer-assessment group exhibited a steeper slope than the comparison group, where the effect of peer-assessment depended on the speakers’ initial performance level. Considering that values closer to 0 imply more calibrated self-assessments, peer-assessment practice appeared to benefit the initially high-performing speakers (i.e., those with already good self-assessment skills), whereas the effect of peer-assessment practice seemed negligible or even negative for the initially low-performing speakers (i.e., those with initially poor self-assessment skills).

Figure 3. Predicted miscalibration scores in the second self-assessment episode (y-axis) as a function of the initial miscalibration scores (x-axis) for each group, with shaded areas showing 95% confidence intervals. Points represent individual speaker–rater observations.

To explore this relationship, we conducted post-hoc pairwise comparisons by computing estimated marginal means for the miscalibration scores. For interpretability, we divided the miscalibration scores from the first self-assessment episode into four quartile-based ranges, using the median values within each quartile as the reference points, which allowed us to compare group differences across the full observed score range while avoiding arbitrary cutoffs or extreme outliers. The speakers’ miscalibration scores from the second self-assessment episode were significantly smaller in the peer-assessment group than in the comparison group for the initially high-performers (top quartile, with the smallest initial miscalibration scores), Estimate = −6.49, SE = 2.09, 95% CI [−10.73, −2.24], t(34.5) = −3.10, p = .004. However, this difference was reduced and no longer statistically reliable for the initially mid-performers (both middle quartiles), Estimate < |2.02| SE < 2.33, t < |0.97|, p > .337, and in fact reversed for the initially low-performers (bottom quartile, with the largest initial miscalibration scores), Estimate = 6.39, SE = 2.84, 95% CI [0.76, 12.02], t(108.3) = −2.25, p = .026 (p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. See Appendix E for plotted estimated marginal means with 95% confidence intervals at each initial miscalibration level, and a figure illustrating the observed between-group differences).

Although the speakers with greater metacognitive knowledge tended to show smaller miscalibration scores (−1.8 points on a 100-point scale), metacognitive knowledge did not emerge as a significant predictor (see Table 4). None of the control covariates appeared to be significantly associated with the miscalibration scores. Fixed-effects predictors, along with covariates, accounted for approximately 66% of the variance in the miscalibration scores (marginal R 2 = .66), and together with random effects, they explained a combined 76% of the variance in the miscalibration scores (conditional R 2 = .76).

Discussion

We explored the degree to which a brief peer-assessment activity helps L2 speakers align their self-assessment of comprehensibility with external raters’ judgment, relative to the situation where speakers engage in repeated self-assessment. We also examined whether L2 speakers’ metacognition contributes to how well they calibrate their self-assessments with those provided by external raters. We found a significant interaction between the speakers’ group assignment (comparison vs. peer-assessment) and their miscalibration performance in the first self-assessment episode, implying that the effectiveness of peer-assessment depended on the speakers’ initial performance level. However, we found no clear evidence that a measure of the speakers’ metacognition contributed to the extent to which their self-assessed and external comprehensibility ratings were aligned.

Peer-assessment and self-assessment of comprehensibility

Our main goal was to determine if a brief peer-assessment activity could enhance alignment between L2 speakers’ self-assessments of comprehensibility and the evaluations of the same speakers by external raters. In the first self-assessment episode, both groups of L2 speakers were roughly comparable in their comprehensibility scores—regardless of whether they were provided by the speakers themselves or the external raters (see Table 3). Both groups also provided two self-assessments of their performance, suggesting that any awareness developed through the speakers’ experience of providing a repeated metacognitive judgment of self-evaluation was likely comparable for the two groups. Against this backdrop, it is noteworthy that the benefits of peer-assessment appeared to depend on the speakers’ initial miscalibration performance (expressed as the absolute difference between self- and other-assessments). Those who had initially demonstrated relatively strong performance appeared to benefit from peer-assessment the most, in the sense that their miscalibration scores decreased, or at the very least did not increase, after participating in peer-assessment practice. Notably, these relationships emerged after controlling for the speakers’ daily English use and exposure. Therefore, a tentative finding here is that a brief peer-assessment activity (about 15 minutes) might help L2 speakers—particularly those with already fairly strong calibration skills—provide self-assessment of comprehensibility that is further aligned with other-assessments.

Peer-assessment might be particularly useful because it raises L2 speakers’ awareness of various dimensions of their speaking performance relevant to comprehensibility. Positive effects of peer-assessment practice on self-assessment accuracy have been reported across various language skills (Chen, Reference Chen2008; Patri, Reference Patri2002), including L2 French comprehensibility (Tsunemoto et al., Reference Tsunemoto, Trofimovich, Blanchet, Bertrand and Kennedy2022). In this study, L2 speakers listened to three speech samples that illustrated low-, mid-, and high-level performances, evaluating them for comprehensibility, then engaged in a stimulated recall session in which they verbalized their thought processes while listening to each recording. Because these recordings featured content that was different from, but followed a task procedure that was similar to, their own performances, the speakers likely had sufficient cognitive resources to use for this awareness-raising task. In other words, the speakers—and especially those with already fairly strong calibration skills—could attend to the specific linguistic dimensions of speech relevant to comprehensibility, instead of, for instance, making sense of the demands of a different task or comparing their own performance to that of a peer for content or task achievement. Indeed, most speakers’ comments touched upon various speech features relevant to comprehensibility, including fluency, vocabulary, and grammar, implying that the speakers were developing awareness of how these dimensions are relevant to comprehensibility (Isaacs & Trofimovich, Reference Isaacs and Trofimovich2012).

However, there appeared to be no noticeable benefit of engaging in peer-assessment for the initially mid-performing speakers, and in fact, there was a negative (reversed) trend for the initially low-performing speakers. Just as less skilled individuals may not recognize their own problems because they lack the necessary skills to evaluate their performance (Kruger & Dunning, Reference Kruger and Dunning1999), the mid- and low-performers in this study might have had trouble deciphering the audio input or may have lacked the linguistic knowledge and awareness to notice the gap between their own performance and that of others. These findings are reminiscent of Matthew effects, typically found in literacy research (Pfost et al., Reference Pfost, Hattie, Dörfler and Artelt2014), where students with initial advantages such as in phonological awareness or spelling ability tend to benefit from instruction whereas students without such advantages tend to stagnate or fall behind. In this sense, our results are somewhat discouraging, as they imply that a brief peer-assessment practice might be insufficient or even disadvantageous for L2 speakers with initially poor self-assessment skills. In future work, it would certainly be worthwhile to understand which types of instructional interventions and at which levels of intensity or duration would be useful in helping initially poor performers improve their self-assessment.

On the positive side, however, for the initially more skilled self-perceivers, some of the benefits of peer-assessment practice might have reflected their exposure to a range of performance levels in comprehensibility. Just as trained and untrained listeners benefit from rater training, which reduces the influence of construct-irrelevant variance on assessments (Davis, Reference Davis2016), the more skilled L2 speakers may have similarly been aided by the intervention, which functioned as rater calibration as it exposed the speakers to several performances in addition to their own. The peer-assessment activity may have also functioned as a perspective-taking task, in which the speakers could adopt and alternate between the roles of a speaker and a listener. For instance, Taylor Reid et al. (Reference Taylor Reid, O’Brien, Trofimovich and Tsunemoto2020) asked raters to perform the same speaking task as the speakers to be assessed, on the assumption that task practice allows raters to become more familiar with the task and more aware of its requirements and challenges. The raters who engaged in task practice were indeed less susceptible to negative stereotypes about L2 learners, compared to the raters who did not perform the task, suggesting that taking on a different perspective helps reduce unwanted, task-irrelevant variability in rater assessments. Even though L2 speakers are not always aware of which speech features make them sound more or less comprehensible to a listener (Strachan et al., Reference Strachan, Kennedy and Trofimovich2019), peer-assessment may have similarly encouraged the more skilled L2 speakers to adopt a different perspective (in this case, a rater’s perspective) and to attend to similarities and differences between their own and their peers’ performances, resulting in self-assessments that were more aligned with external ratings. Put differently, evaluating peers’ performances that illustrate a range of comprehensibility levels while also taking on the rater’s perspective might have aided at least some L2 speakers in becoming more attuned to their own comprehensibility.

While peer-assessment activities can be implemented in different ways, such as through providing feedback to peers (Chen, Reference Chen2008), the reflexive nature of stimulated recall may have been particularly useful in raising the speakers’ awareness of comprehensibility. Stimulated recall requires people to verbalize their thought processes as they experience audio, text, or video materials (Gass & Mackey, Reference Gass and Mackey2017), and people often engage in self-explanation (Chi, Reference Chi and Glaser2000), which enhances their awareness (Swain, Reference Swain, Chalhoub-Deville, Chapelle and Duff2006), helping them experience greater engagement with, and gain a deeper understanding of, the targeted phenomena (Suzuki, Reference Suzuki2012). For example, in L2 pronunciation research, speakers demonstrating greater awareness of pronunciation, including through stimulated recall or think-aloud procedures, tend to show greater pronunciation accuracy (Azaz, Reference Azaz2017; O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2019). In this study, the peer-assessment group was asked to verbalize their thoughts as they were listening to sample performances by their peers. The overt focus on languaging, which refers to the practice of using language to discuss issues of language form (Fujisawa et al., Reference Fujisawa, Doi and Shintani2024; Swain, Reference Swain, Chalhoub-Deville, Chapelle and Duff2006), might have helped the speakers crystallize various linguistic features with relevance to comprehensibility, making them available for use during the second self-assessment. Nonetheless, the less-skilled L2 speakers in our sample might have found it challenging to verbalize their thought processes while processing linguistically rich stimuli (Brown, Reference Brown2011). Thus, a future study should explore whether more guidance provided before self-assessment, such as explicit instruction about specific speech features relevant to L2 comprehensibility, could help lower-skill learners attend to specific features of the speech.

Finally, peer-assessment may have been particularly useful for some speakers because it was combined with repeated self-assessment. In previous work, greater alignment between self- and other-assessments was observed when L2 speakers engaged in repeated self-assessment (Kissling & O’Donnell, Reference Kissling and O’Donnell2015; Lappin-Fortin & Rye, Reference Lappin-Fortin and Rye2014; Saito et al., Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Abe and In’nami2020; Strachan et al., Reference Strachan, Kennedy and Trofimovich2019). Along similar lines, in this study, the speakers who engaged in simulated recall may have enjoyed the double benefit from the repeated self-assessment, which increased their content and task familiarity and potentially also freed up processing resources, and from the peer-assessment intervention, which heightened their awareness of various linguistic dimensions of comprehensible L2 speech. Until individual contributions of repeated self- and peer-assessment are disentangled in future research, a tentative conclusion emerging here is that repeated self-assessment combined with an awareness-raising activity (e.g., peer-assessment followed by stimulated recall) predicts greater calibration of self-assessment for L2 speakers—particularly those with already fairly strong self-perception skills—over and above the effect of repeated self-assessment implemented alone. As for L2 speakers with initially weaker skills, they might stand to benefit from longer or more focused and more intensive interventions (Tsunemoto et al., Reference Tsunemoto, Trofimovich, Blanchet, Bertrand and Kennedy2022).

Metacognition and self-assessment of comprehensibility

This study’s second goal was to examine the degree to which individual differences in L2 speakers’ metacognition are relevant to their ability to align their self-assessments with the judgments by external raters. The current findings depart from those reported previously (Jang et al., Reference Jang, Lee, Kim and Min2020), in that metacognition—measured through the metacognitive awareness inventory (Harrison & Vallin, Reference Harrison and Vallin2018)—was generally not relevant to the alignment between L2 speakers’ self- and other-assessments, even though there was a trend toward better calibration for speakers with stronger metacognitive skills (see Table 4). One explanation for this discrepancy concerns the abstractness level of the self-rated dimension. Educational research has offered ample evidence that the use of concrete, task-specific criteria (e.g., through clear, specific assessment rubrics) leads to better alignment between self- and other-assessed performance compared to the use of abstract criteria (Panadero & Romero, Reference Panadero and Romero2014; Ross, Reference Ross1998). Reflecting this distinction, in Jang et al.’s (Reference Jang, Lee, Kim and Min2020) study, L2 speakers’ recall of concrete words was more strongly associated with metacognitive knowledge than their recall of abstract words. Considering that comprehensibility is likely an abstract construct underpinned by multiple linguistic dimensions (Saito, Reference Saito2021; Trofimovich & Isaacs, Reference Trofimovich and Isaacs2012), it might be harder to show a strong association between metacognition and comprehensibility, compared, for instance, to relationships between metacognition and specific linguistic dimensions of speech, such as segmental and word stress accuracy.

Compared to metacognitive regulation, which refers to a person’s control of various cognitive processes, a person’s metacognitive knowledge of cognitive abilities may also be less relevant to how closely self-assessments match performance. Because metacognitive regulation relates to how people self-monitor, control, and self-evaluate their performance, it seems reasonable that metacognitive regulation should be more strongly tied to self-assessment than metacognitive knowledge. For example, university students with greater metacognitive regulation (assessed through the metacognitive awareness inventory) tended to be more confident about their knowledge of lexical items and indeed received higher scores in a vocabulary test than students whose level of metacognitive regulation was lower (Teng, Reference Teng2017). Alternatively, it could be that self-assessment of global dimensions of L2 speech such as comprehensibility is not underpinned by either metacognitive knowledge or regulation, for example, as was the case for readers’ self-rated confidence in answering comprehension questions, where confidence judgments were unrelated to metacognitive knowledge or regulation (Schraw & Dennison, Reference Schraw and Dennison1994). Although we had to remove our measure of metacognitive regulation due to its low internal consistency, previous research has shown that university students became hesitant to endorse the statement “I try to translate new information into my own words (Item 13)” several weeks into taking a course, possibly because they had realized which strategies were necessary and which were less useful for succeeding in the course (Harrison & Vallin, Reference Harrison and Vallin2018). It is therefore plausible that regulation, or strategies used for learning, can be context- or task-dependent, and it remains for future work to establish links between self-assessed comprehensibility and metacognition.

Finally, the type of metacognition examined here through the metacognitive awareness inventory, such as whether a person has motivation or strategies for learning, may not be the most optimal tool for exploring the role of L2 speakers’ metacognition in pronunciation learning. For instance, compared to domain-general metacognition, task-specific metacognition, such as “I strategize ways to improve oral proficiency, and accent specifically” (Moyer, Reference Moyer2015, p. 405), may be more relevant to self-assessment of L2 speech, including comprehensibility. Therefore, future work may wish to target different instruments tapping into general and pronunciation-specific measures of metacognition (see Vandergrift et al., Reference Vandergrift, Goh, Mareschal and Tafaghodtari2006, for a listening-specific measure) in relation to L2 speakers’ self-assessment.

Limitations and future directions

Our findings must be treated as preliminary. Because the peer-assessment group tended to receive higher comprehensibility ratings from external raters and to self-evaluate their performance more positively than the comparison group (despite the absence of statistically significant between-group differences), various pre-existing differences might have impacted the findings. The first miscalibration scores were included in the final model as a control covariate to mitigate this problem; nevertheless, these findings must be replicated to clarify the role of peer-assessment in L2 speakers’ judgments of their own performance. Next, the metacognitive awareness instrument yielded a low internal consistency index for the metacognitive regulation items, which were thus excluded from the final analysis. Therefore, future work should disentangle possible contributions of domain-general versus pronunciation-specific metacognition, along with other individual difference variables (e.g., L2 use, perceived pronunciation value), to L2 self-assessment. Similarly, completing the metacognitive inventory between the two self-assessment episodes (see Figure 1) may have also encouraged at least some speakers to reflect on their first self-assessment experience or peer-assessment (for the peer-assessment group) and may have helped them provide more accurate self-assessments the second time around. Although we did not find statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of metacognitive knowledge, it remains for future work to determine whether the timing of when the metacognitive inventory is administered (i.e., before or after the target tasks are completed) may modulate the degree to which L2 speakers draw on metacognition to perform the task.

Last but not least, this study was motivated by the assumption that the alignment between self- and other-assessments of comprehensibility is desirable and that pedagogical interventions should minimize absolute differences between the two sets of ratings. Self-assessment accuracy, which is critical for self-directed learning (Little & Erickson, Reference Little and Erickson2015), has been linked to gains in L2 speakers’ pronunciation and fluency (e.g., Kissling & O’Donnell, Reference Kissling and O’Donnell2015). Nevertheless, neither this study nor the majority of previous research on L2 self-assessment explains why alignment is important or beneficial for L2 speakers. Even though people might have a “faulty” or miscalibrated view of themselves, for instance, by being overly confident in how they strategize their learning (Sato, Reference Sato, Li, Hiver and Papi2022), overconfident self-views can sometimes have a positive impact, in the sense that people might experience reduced communicative anxiety or might show increased desire to engage in L2 communication (MacIntyre et al., Reference MacIntyre, Noels and Clément1997), which would lead to extra communicative practice with potential benefits for language development. Thus, future work should examine whether and to what extent alignment between self- and other-assessments has real-world consequences for L2 speakers, for example, in terms of whether they recognize and benefit from listeners’ feedback, notice the strengths or weaknesses of their language skills, enjoy greater self-control, attain greater academic achievement, or show higher retention and completion rates in their coursework or studies.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that a brief peer-assessment activity was effective at helping L2 English speakers—particularly those with already fairly strong self-assessment skills—narrow the gap between their self-assessment of comprehensibility relative to external raters’ judgments. The study offered new insights regarding the role of individual differences in L2 speakers’ self-assessment, demonstrating that L2 speakers’ metacognitive knowledge—at least within the methodological constraints of this study—contributed little to their self-ratings of comprehensibility. These findings highlight potential value of brief instructional interventions for enhancing speakers’ awareness of comprehensible L2 speech and motivate future work focused on long-term, real-life consequences of L2 speakers’ self-assessment skills.

Replication package

All research materials, data, and analysis code are available at https://osf.io/pag7b/.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Concordia Applied Linguistics lab members Kym Taylor Reid, Lauren Strachan, Pakize Uludag, Rachael Lindberg, Oguzhan Tekin, Chen Liu, Yoo Lae Kim, Anamaria Bodea, and Thao-Nguyen Nina Le who provided valuable feedback on various aspects of this work. We are also grateful to Ryo Maie for his support with data analysis, and to three reviewers and the journal editor of Applied Psycholinguistics for their insightful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Funding statement

This research was supported through a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada grant to Pavel Trofimovich (430-2020-1134).