Introduction

The first mandate of President Macron was marked by innovations and unexpected developments. After his own election and his capacity to gather a solid majority in Parliament, the yellow vest movement and Covid-19 (Bendjaballah & Sauger Reference Bendjaballah and Sauger2021, Reference Bendjaballah and Sauger2022; Houard-Vial & Sauger Reference Houard-Vial and Sauger2020), normalization could have been expected for the next term. The year 2022 proved somewhat different. The presidential elections, held in April, started by the late entry into the campaign of President Macron, in a context of an exit from the pandemic and the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. It gave way to a campaign that generated little interest among voters. Following the re-election, once again, of Macron against Le Pen, the legislative elections in June led to a rare situation in the Fifth Republic, the absence of any absolute majority at the Assemblée nationale. This did not cause immediate political gridlock. The rationalization of the parliamentary process made it possible for the executive to advance its own agenda of reform. Article 49.3 of the Constitution, enabling the government to pass a bill without a formal vote in the Assemblée nationale, was used 12 times since Elisabeth Borne was appointed Prime Minister. It was used only once in the previous legislature.

The year 2022 proved also the continuity of the transformation of the French party system. Even if Zemmour, the new radical-right contender having surged in 2021, did not finally bring about much change, the opposite dynamic was visible in 2022 on the left. Most left-wing parties agreed to form a new electoral coalition, called Nupes (New Popular Green and Social Union, Nouvelle Union Populaire Ecologique et Sociale). This consolidated the emergence of three blocks of competition in France, the left, the center-right, and the radical right.

Election report

Presidential elections

Early in 2022, the scene of the presidential election to come in April was largely set. Most parties had already selected their candidates, who up until March were looking for the 500 mandatory signatures of local office holders to run for the election. Yet, an activist initiative called the “Primaire populaire” (People's Primary), which aimed to designate a common candidate for all left-wing parties from the outside of regular party organizations, launched an informal ballot in January. After long discussions, seven candidates were included in the ballot, three of whom had explicitly refused to take part in this selection (A. Hidalgo, already designated by the Socialist party; Y. Jadot, already designated by the green Europe Ecologie-Les Verts (EELV); and J. -L. Mélenchon, already designated by the radical left La France Insoumise [LFI]). The vote itself followed an innovative system based on an evaluation of each candidate by voters in accordance with their judgment on the candidate (from very good to insufficient). In the end, C. Taubira, former Minister of Justice (Hollande Presidency) and former member of the Radical Party, was endorsed with a clear margin over all other candidates. About a month later, however, she stepped out of the race.

On 7 March, the Constitutional Council confirmed that 12 presidential candidates had secured their mandatory 500 signatures, with no significant surprise. A third of them were women (A. Hidalgo, V. Pécresse, M. Le Pen, and N. Arthaud), three of them from the ranks of the most prominent parties. Despite high fragmentation, the number of 12 candidates remains limited with regard to the peak of 16 candidates in 2002.

The electoral campaign was in some ways derailed by Russia's invasion of Ukraine, on 24 February. Whereas the campaign started as an evaluation of Covid-19 crisis management by the executive, the war put a halt to it. It shifted the political agenda on foreign relations. Support for Ukraine was a near-consensus. Yet, possible connivence with Russia was heavily used against the Rassemblement national (RN), especially as the party was accused of having borrowed from a Russian bank and then of being still dependent on the country's support. Later, with the energy prices increasing, purchasing power and inflation came to the foreground of the campaign. Macron's support for Ukraine, and the feeling of a direct threat that was triggered in public opinion, led to a bump in support for the executive in a “rally around the flag” dynamic despite the threat not directly affecting national territory. However, the government's diplomatic efforts came at a cost, as Macron played the role of a head of state too consumed by diplomatic overtures to find time to campaign. He unveiled his campaign program just a few weeks before the first round of the election and held just one rally, in early April in Paris.

The first round of the French presidential election was held on 10 April. It saw the majority of votes going to three candidates: Macron (27.8 per cent), Le Pen (23.1 per cent), and Mélenchon (21.9 per cent) as displayed in Table 1. The gap with the fourth candidate is huge, with Zemmour scoring only 7.1 per cent, illustrating the rule that there are only three viable candidates in the first round of a majority run-off system (Cox Reference Cox1997). The appeal to tactical voting among left-wing candidates was particularly prominent, Mélenchon building successfully on his leading position in the block. Also remarkable is the sign of voters’ fatigue with party candidates, with abstention at 26.3 per cent, which is not a historical record but still close to the peak of 2002. Overall, the results of the first round illustrate the transformation of the French party system. The two long-standing blocks of opposition between left and right are over. Yet, if Macron is considered as the candidate of the center-right, this being more acute in 2022 than in 2017, the three blocks are exactly the same as they have been since the 1980s: a left-wing block, with the difference that the radical Mélenchon took over the lead of this block; a right-wing block, dominated by Macron and having managed to secure the realignment of part of the traditional center-left to it; and a radical right block, still dominated by Le Pen, and still gaining momentum as the fragmentation of this block in 2022 led to an overall increase of support, with about 30 per cent of the valid votes in 2022 if the votes achieved by both Le Pen and Zemmour are summed up. In this sense, the first round of the presidential election confirmed the liquidation of traditional government parties (most notably the Socialist Party and The Republicans (LR), with about 6 per cent altogether), whilst preserving the pattern of competition, now four decades old. Macron's gradual shift toward the positions of the traditional right is indeed an illustration of this. Notice as well that the balance of power among these blocks has come, once again, quite balanced, with about 30 per cent for the left (adding up traditional radical Trotskyist movements, the radical left of Mélenchon, the Greens, and what is left of socialism), 30 per cent for the radical right, and somewhat more than 30 per cent for the center/center-right.

Table 1. Elections for President in France in 2022

Note: All percentages for candidates’ scores have been computed on valid votes.

Source: Conseil Constitutionnel website (2023).

The second round was held on 24 April. Emmanuel Macron was re-elected, defeating Marine Le Pen with 58.5 per cent of the vote, while 28 per cent abstained from voting. The year 2022 is a much closer race than in 2017, when Macron gained 66 per cent of the vote. Contrary to 2017, Macron did not completely dominate the debate against Le Pen. And despite calls for resistance to the threat she was said to be representing, more and more voices questioned the wisdom of supporting, once again, Macron. In his victory speech, Macron did acknowledge this broad support. Yet, his politics of “at the same time” (i.e., looking both left and right) did not endure much, Macron embracing more and more the traditional position of the French center-right, in line with the liberal values he professed.

Three main conclusions are to be drawn up. The first one is the massive defeat of mainstream parties: Valérie Pécresse, from Les Républicains (The Republicans-LR), and Anne Hidalgo, from Parti Socialiste (PS), with, respectively, 4.8 per cent and 1.7 per cent of the vote, signaled the worst-ever results for their parties. Valérie Pécresse lost most of her party's right-wing voters to Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour. The more moderate voters chose Macron. Socialist voters preferred Jean-Luc Mélenchon as a more radical and more viable candidate. These two parties, which have long dominated the party system and political life, no longer score at the national level. They have, at least for the moment, been reduced to being local and regional parties.

Second, the radical right has surged to its best score and the mainstream center-left has been supplanted by a more radical force, around Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Having pursued his takeover of the political mainstream, Macron has opened space for radical forces. As a consequence, the fact that populist, anti-establishment parties come closer and closer to power does not come as a full surprise. Eric Zemmour, who obtained little more than 7 per cent, has not succeeded in smashing the right. However, for a first attempt, this score is not marginal. Marine Le Pen, on the other hand, has increased her electoral support by more than two points, compared to 2017, and is now the main opponent of Macron. Despite controversies over her closeness to Putin, Marine Le Pen succeeded in attracting voters by focusing in her speeches on the issue of the loss of purchasing power.

Third, a quarter of voters did not vote, attesting to high levels of indifference or even rejection of the policy strategies offered by the candidates. This rising abstention and protests (following the first round) has heightened scrutiny of a system that invests much attention on the figure of the president. By ensuring the president wins at least 50 per cent of the popular vote, France's two-round electoral system increasingly forces voters into “tactical” choices, which might fuel resentment and fatigue (Grossman & Sauger Reference Grossman and Sauger2017).

Legislative elections

Since the 2000 constitutional reform, legislative elections now follow the presidential election by a few weeks. Although this is not mandated by the Constitution, it is unlikely to change in the near future. French voters are then faced with a series of four consecutive ballots (Dupoirier & Sauger Reference Dupoirier and Sauger2010), all held under the principle of a majority run-off (at the national level or in local districts).

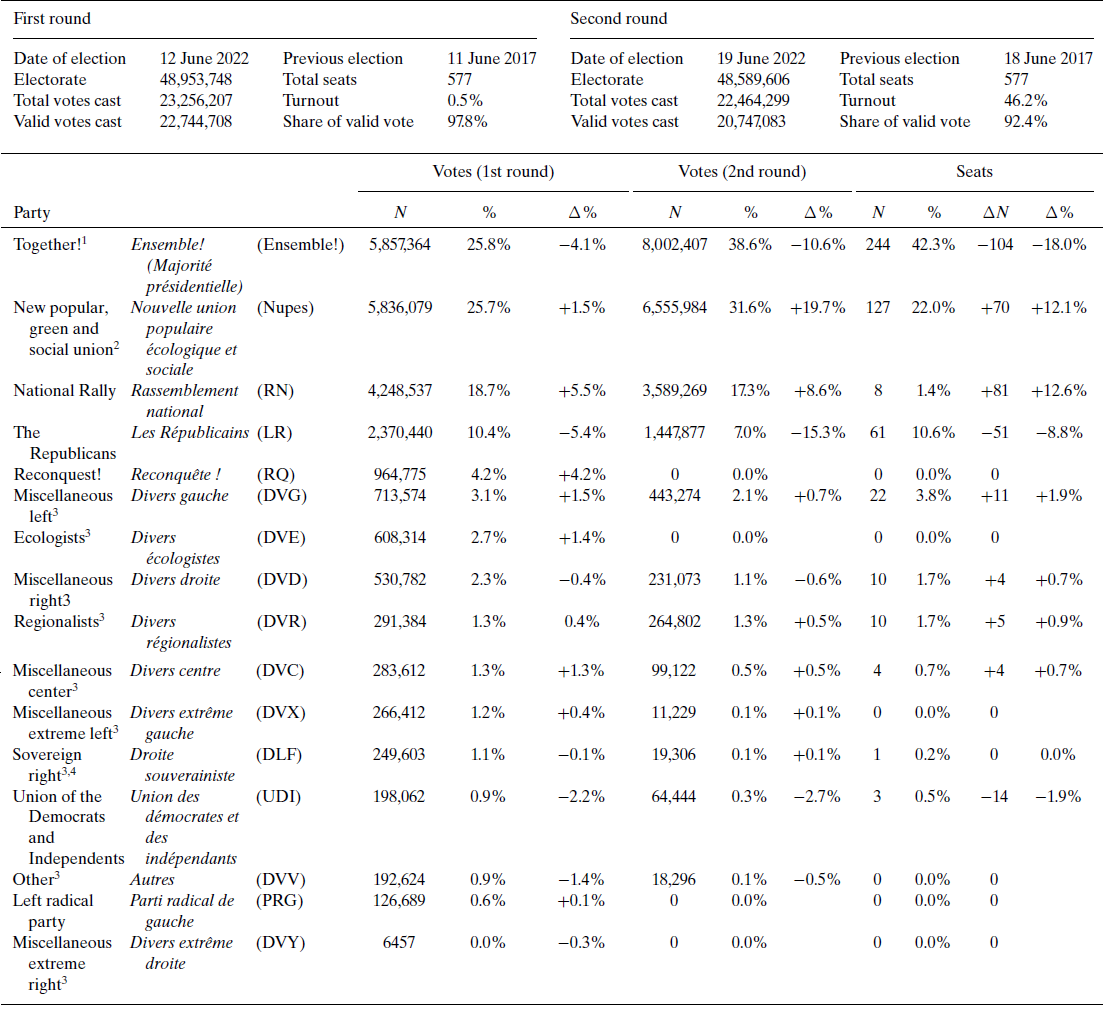

The parliamentary elections of 12 and 19 June confirmed Macron's fragility. As in 2017, fewer than half of the voters (46.5 per cent) cast a valid vote in 2022. And, crucially, Macron's coalition, named Ensemble!, lost more than 100 seats (Table 2). Macron won 244 seats—45 short of the 289 needed to govern with a majority. The left, meanwhile, more than doubled its number of seats thanks to a new electoral coalition, the Nouvelle Union Populaire Écologique et Sociale (Nupes). LR lost two-fifths of its 2017 votes. But the real winners of June 2022 were Le Pen's RN, which won 89 seats against eight in 2017. RN's candidates had always performed poorly so far, unable to capture seats except for the 1986 elections, which were held with a proportional rule, or in special local circumstances. Winning such a large number of seats, formally making the RN the second largest group in the National Assembly, was a symbol of the capacity of the party to now be a credible candidate for winning elections despite the majority rule. It has also had more direct consequences. For the first time since 1962, no clear majority emerged from the election. Neither the left-wing parties nor the RN was willing to cooperate with anyone to form a majority. The Republicans became the key actor for the possible support of a minority government led by Ensemble!. As there was no prospect of a stable parliamentary majority to govern France, questions arose about whether President Macron would be able to deliver on his agenda, particularly on controversial topics like pension reform.

Table 2. Elections to the lower house of Parliament (Assemblée nationale) in France in 2022

Notes:

1. Coalition of formerly LREM and MoDem, compared to the sum of both in 2017.

2. Left-wing coalition, compared to the sum of LFI, PS, PCF, and EELV in 2017.

3. Grouping of unrelated parties and candidates with close political orientations.

4. Compared to DLF in 2017.

Source: Ministry of Interior website (2023).

The results could be explained by many factors. First, the president did little/no campaigning. Second, the left joined their forces in the Nupes alliance to circumvent one of the constraining specificities of the French electoral system, that is, the high threshold required to qualify for the second round. Third, Les Républicains recovered, even if only partially, compared to the first round of the presidential election. Fourth, the strong performance by the radical right. Fifth, Macron's response to the good performance of its adversaries in the first round, especially Nupes and RN. Finally, the “front républicain,” which refers to a strategy by mainstream parties to ally against far-right politicians when electoral circumstances demand it, somehow broke down. Only 31 per cent to 35 per cent of Nupes voters backed the Ensemble! candidate against the RN in the second round. Forty-five per cent to 58 per cent abstained. As for Ensemble! voters, 16 per cent to 41 per cent backed a Nupes candidate against an RN opponent, and 48 per cent to 72 per cent refused to choose (see Durovic Reference Durovic2023).

Cabinet report

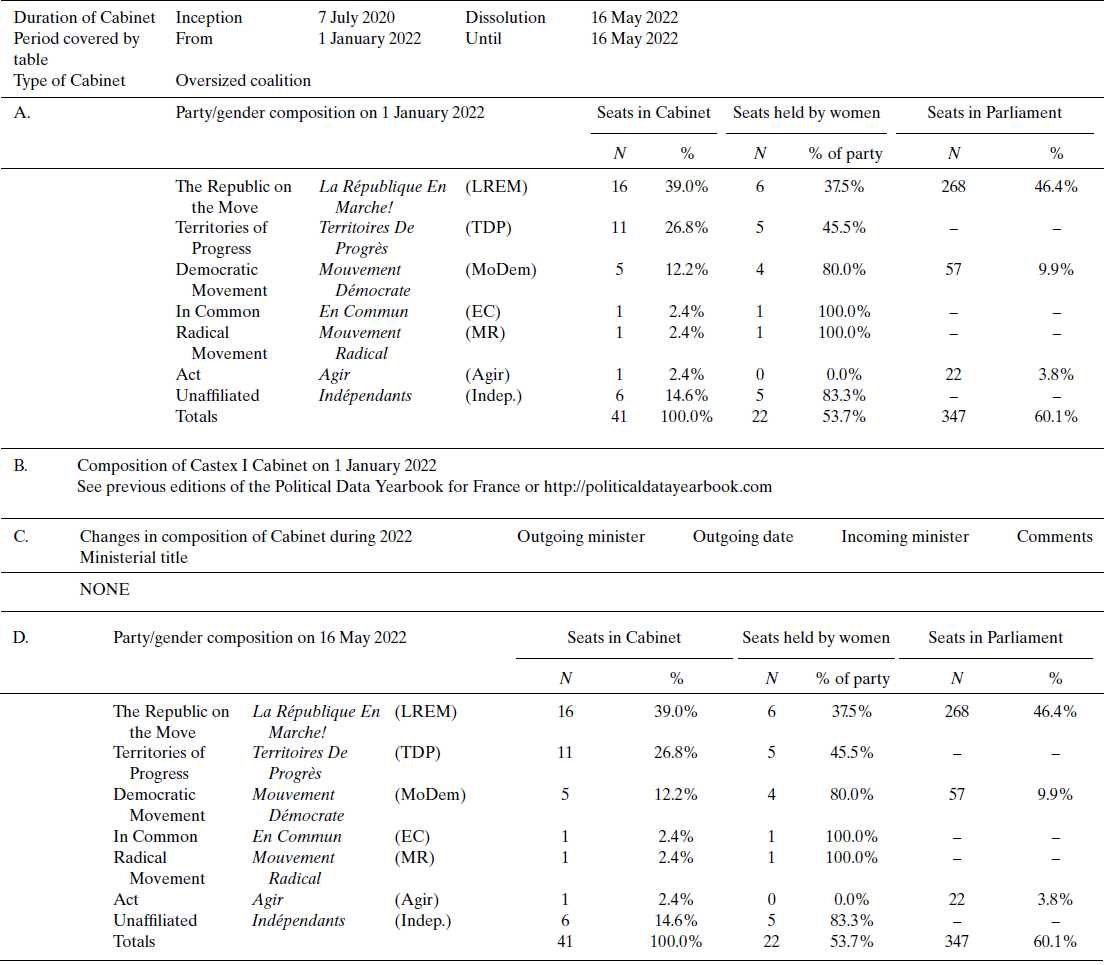

On 16 May, nearly one month after the presidential election's second round, Prime Minister Jean Castex resigned. That his government was not to be reconducted after the election was considered a given (see Table 3). President Macron appointed former Minister of Labour, Élisabeth Borne, to replace him. It was the second time a woman has held the top Cabinet job (after Edith Cresson under François Mitterrand presidency). Among the most significant nominations, the historian and head of the French National Immigration History Museum, Pap Ndiaye, was nominated as Minister for Education and Youth.

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Castex I in France in 2022

Source: Assemblée nationale website and Government website (2023).

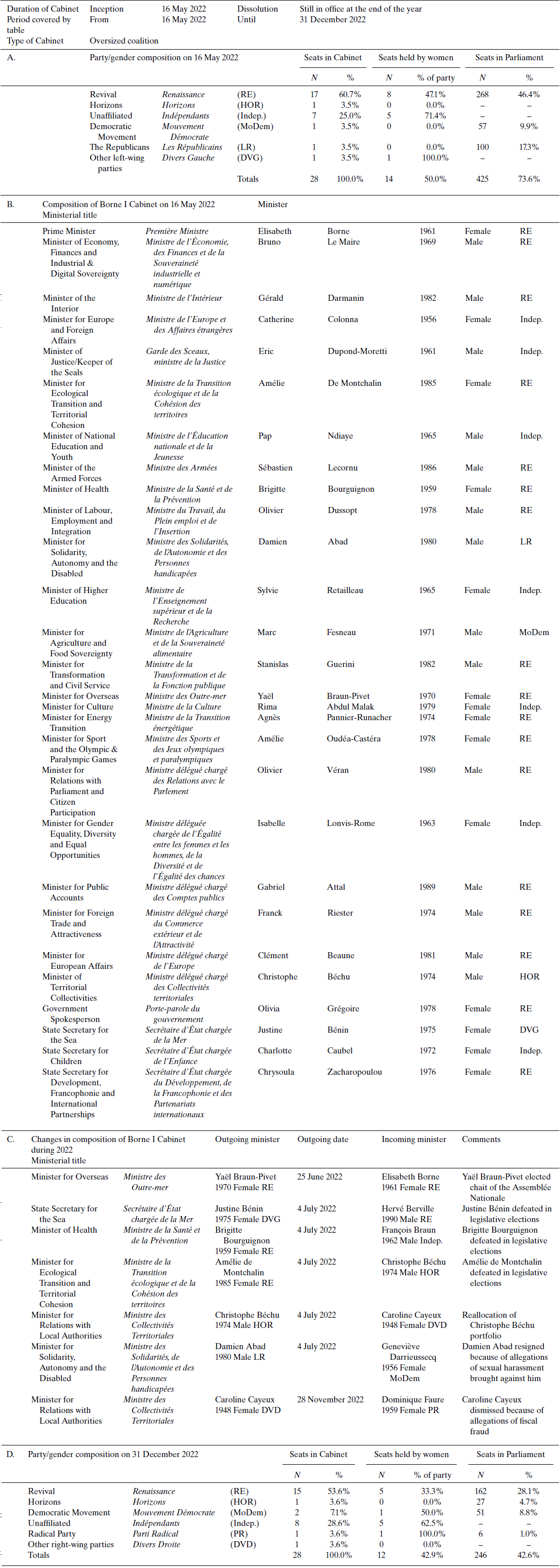

Following the legislative elections, a change in the composition of the government was announced on 4 July 2022. Damien Abad, the solidarity minister coming from Les Républicains, was sacked because of an investigation for attempted rape. Those three ministers who did not win in legislative elections also resigned.

But most of the other ministers remained in their positions (Gérald Darmanin kept his job at the interior ministry, Bruno le Maire remained Finance Minister, and Éric Dupond-Moretti stayed as Justice Minister).

Cabinet composition (see Table 4) shows the incapacity of the executive to widen its support at the National Assembly. The Republicans were attracted only on a personal basis, and the general overlook of the government is rather technical than political, with few figures with high visibility or long experience in politics.

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Borne I in France in 2022

Source: Assemblée nationale website and Government website (2023).

Parliament report

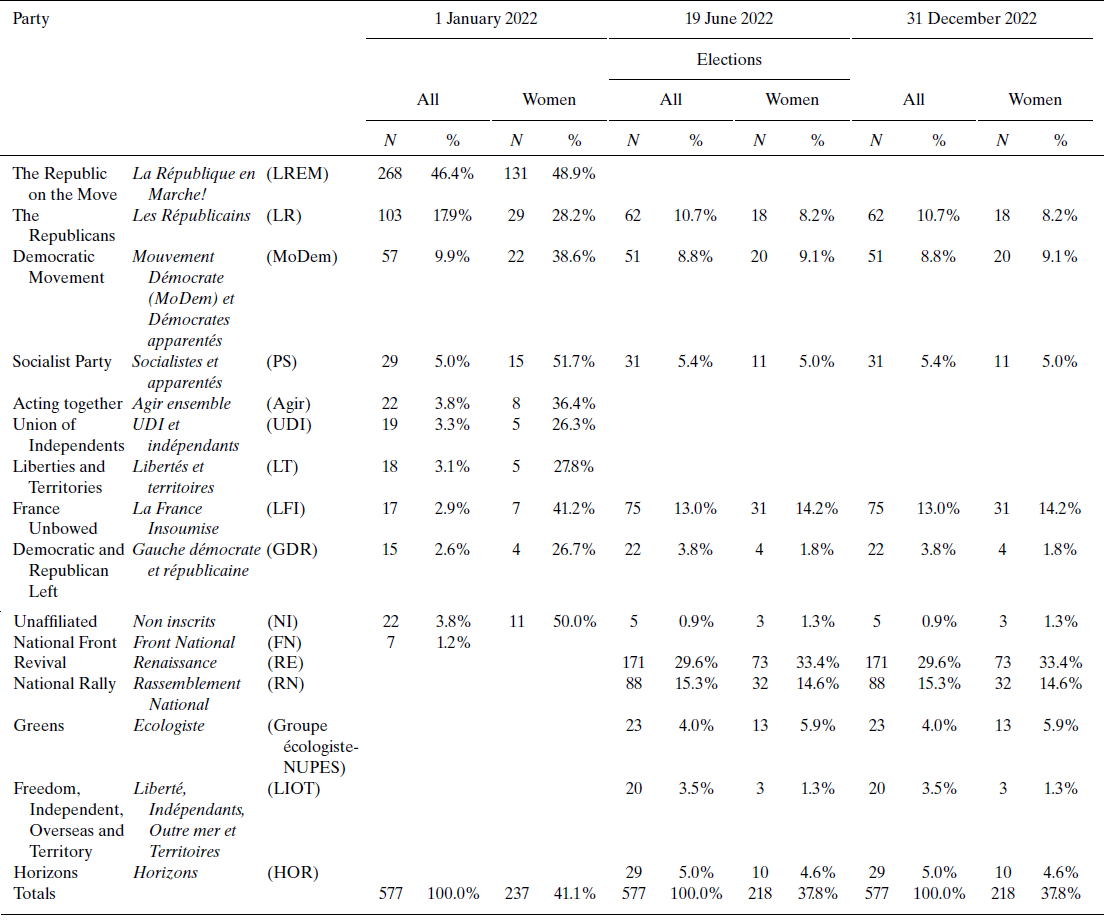

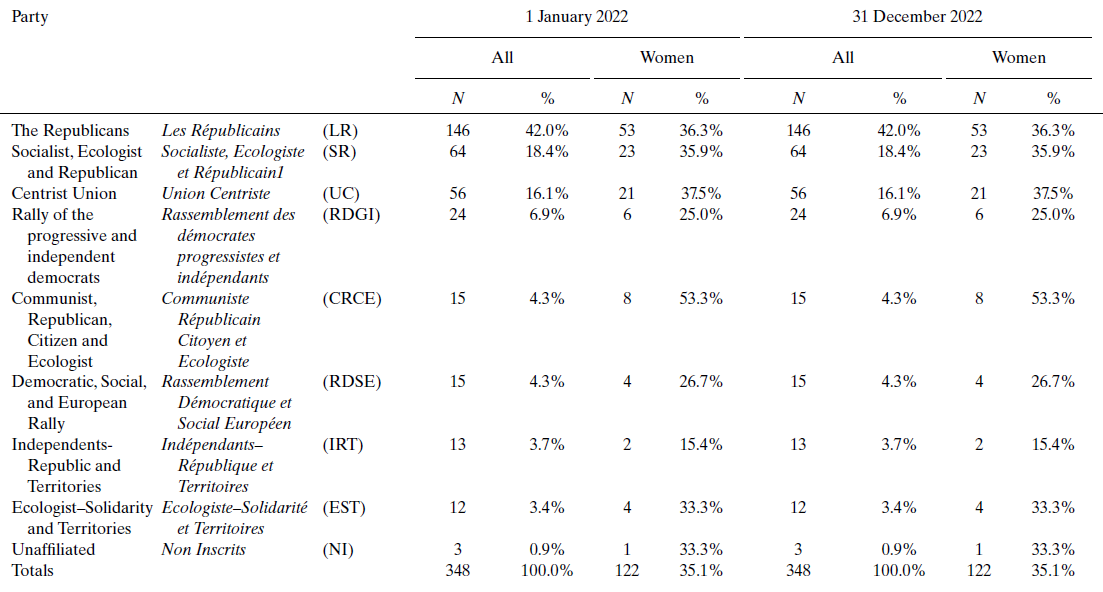

Tables 5 and 6 show the composition of both houses of Parliament in France in 2022.

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the National Assembly (Assemblée nationale) in France in 2022

Source: Assemblée nationale website (2023).

Table 6. Party and gender composition of the Senate (Senate) in France in 2022

Source: Senate website (2023).

Founded in October 2021 by former Prime Minister Édouard Philippe in order to attract center-right support for Emmanuel Macron for the 2022 presidential election, the party Horizons formed ahead of the legislative elections a coalition with two other main centrist parties—Democratic Movement (MoDem) and La République En Marche! (LREM)—to coordinate which candidates they run. Yet, this electoral coalition did not translate into a corresponding parliamentary party group at the National Assembly once political groups were formed. All participants set up their own group.

After defeating all other left-wing candidates in the first round of the presidential election, Mélenchon, leader of the radical left-wing party LFI, proposed an alliance to his left-wing rivals, that is, the Socialists, the Parti Communiste Français (PCF), and the Greens (EELV), as well as smaller parties such as Génération·s and Génération écologie. Called Nupes, the alliance was aimed at uniting the various parties of the left—as intended to do in 1972 the Common Programme (PS, PCF, and Mouvement des Radicaux de Gauche) and in 1997 the “Plural Left” (PS, PCF, Citizens’ Movement, and the Greens). Each party first signed a bilateral agreement with LFI. Then, all one-to-one agreements merged into a platform containing 650 policy proposals. LFI is very much the dominant force within the Nupes: With 325 candidates across France, Mélenchon's movement accounts for over 55 per cent of the Nupes’ candidates. This electoral coalition was not meant to be short-lived. Even if all the founding members launched their own group in the National Assembly, the label has still been in use since then. Of course, leadership within the coalition has remained highly disputed, with both the Socialists and the Greens worrying about Mélenchon's leadership.

Minority governments are not common in France, mostly because of the majority voting system. However, in June, when Emmanuel Macron lost his majority in the National Assembly, he failed to find a party willing to enter a coalition with his group, Ensemble!. Les Republicans (LR), whose program was close to Macron's, rejected a coalition offer but expressed their willingness to cooperate with the government on a bill-to-bill basis. Consequently, the relationship between the Parliament and the government became unpredictable. The direct consequence of this situation was the intense use of Article 49.3 of the Constitution, enabling the government to adopt bills without a formal vote in the Assemblée nationale, which was used 12 times in 2022 since the elections. Even though RN has in the past voted in favor of some of the motions of censure sponsored by the left, the left has always refused any form of direct cooperation with the radical-right party. This has made it possible for the government to navigate through its minority status without a clear and unified opposition. Yet, its capacity to use Article 49.3 to pass legislation has been limited mostly to budget bills, leading to increasing uncertainty as to the government's prospects of pushing forward its political agenda.

The formation of a RN group at the National Assembly led to intense discussions about the accommodation of this party in the governing structure of the Assembly. Conventions proved strong enough to grant the party access to offices in commissions and to the steering committee of the Assembly. Collaboration between RN and other groups was, however, limited.

Political party report

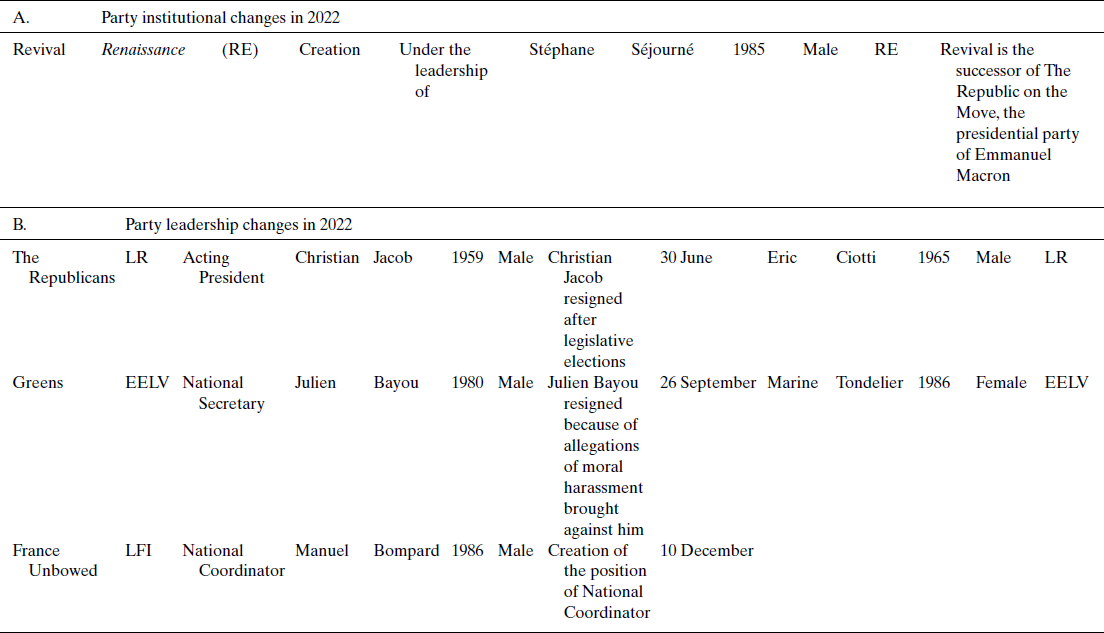

In the aftermath of the elections, many changes were observed (Table 7).

Table 7. Changes in political parties in France in 2022

Source: France Politique (2023).

In May, in view of the June legislative elections, the PS national council agreed to an alliance with the radical-left party LFI. The agreement includes a deal on the distribution of constituencies. The PS thus joined LFI, Europe Ecologie-Les Verts (EELV), and the Parti Communiste (PCF) in the alliance of the New Popular, Environmental and Social Union (Nupes) for the June elections.

In September, the head of France's “Greens” party stepped down after his former partner accused him of psychological abuse. His successor, Marine Tondelier, stepped in after winning the internal election in December.

In November, Jordan Bardella was officially elected as the new president of the RN, to succeed Marine Le Pen. Bardella, who had already been interim president for a year during Marine Le Pen's presidential campaign, won nearly 85 per cent of party members’ votes.

In December, Eric Ciotti, who embodies the most radical wing of Les Républicains, was elected president of the party.

Finally, Manuel Bompard was appointed coordinator of LFI, a new position created for him that was highly contested by many political figures within the party.

Institutional change report

No significant news is to be reported as concerns institutional change in France in 2022. The President has not given up on a reform that could include a return to seven-year presidential terms, but the prospect of tensions over the pensions’ reform and the weakening of his majority in the Assemblée nationale prevented him from embarking on an institutional reform.

Issues in national politics

As a consequence of the war in Ukraine, France experienced a rising cost of living and a high bump in energy prices. In July, inflation reached 6.1 per cent over one year,Footnote 1 a level not seen since 1985. In August, the government approved a 20-billion-euro package of measures to help struggling households face soaring energy and food prices. MPs also approved a gas price freeze and capped the increase in regulated power prices this year at 4 per cent.

At the end of September, employees at TotalEnergies and ExxonMobil oil refineries went on strike, asking for better wages amid rising inflation—which led to massive fuel shortages at service stations across France. The shortages were so big that the government was forced to intervene, requisitioning striking employees. In early November, the unions reached an agreement with management to increase salaries between 7 per cent and 10 per cent.

To conclude, the 2022 French elections (both presidential and legislative) produced a similar outcome to the 2017 elections, at least in two respects (Durovic Reference Durovic2023). First, the mainstream parties, LR and the Socialist party, who had been eliminated in the first round in 2017, have experienced even harsher defeats in 2022. Second, and in correlation to the first point, Marine Le Pen is now identified as the opposition figure, although the new Nupes gave some hopes to the left. The year 2022 has not, thus, represented any comeback to normal politics. It also leaves a number of questions open about the future of French politics. The extent to which a minority government is viable in the context of polarization is all but certain. Alternative options are slim. The unpopularity of the new government and the bleak electoral prospects of the governing party make it unlikely that President Macron chooses to dissolve the National Assembly rapidly. The way forward has thus to come through cooperation with other parties that have no reason to do so.

On a longer term, the 2022 elections have not provided clear perspectives about what can come after Macron, as he will not be able to run in 2027. The only spreading belief is that Marine Le Pen's turn is coming, sooner or later.