1. Introduction

In recent years, many countries have seen an expansion in the role of financial actors in their health systems. This trend is driven by several factors, including an aging population, the resilience of the health sector to economic downturns, opportunities for consolidation in fragmented markets, the potential for increased efficiency in care delivery, as well as structural and policy shifts – namely, the growing market orientation of health systems, permissive regulatory environments, and an increasing willingness to extract or repurpose community health assets for profit (Bruch et al., Reference Bruch, Roy and Grogan2024; Healthcare Private Equity Market 2023, 2024; Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Paris, Joshi and Dedet2025). Most notably, there has been a remarkable rise in private equity (PE) investments in health care, reaching a record $61 billion in asset value in 2023 (Healthcare Private Equity Market 2024, 2025). While for-profit privatisation in healthcare is not a new phenomenon in many high-income countries, the current wave of ‘financialization’ marks a potentially transformative shift of public and private health care entities into saleable and tradable assets to primarily benefit the financial sector (Bruch et al., Reference Bruch, Roy and Grogan2024). This shift is paralleled by rising penetration of supplementary, complementary and substitutive private health insurance, even across countries with universal health care systems, where it is predominantly favoured by higher-income groups seeking faster or more specialised care outside the public system (Kullberg et al., Reference Kullberg, Blomqvist and Winblad2025; Tynkkynen et al., Reference Tynkkynen, Alexandersen, Kaarbøe, Anell, Lehto and Vrangbӕk2018).

The growing influence of PE in healthcare raises important questions about the potential consequences for patient care and access, healthcare costs, and overall health system sustainability in diverse national contexts. In general, PE firms invest in health care entities to drive investor returns over short investment periods, often within three to seven years. PE investments are frequently structured as leveraged buyouts, in which a substantial portion of the purchase price is funded with debt that is placed on the acquired company’s balance sheet, leaving the health care entity, rather than the PE firm, responsible for repayment. The growth of PE investments is particularly salient in the context of health care. In certain sectors such as outpatient clinics, PE firms are alleged to embark on a pattern of ‘stealth consolidation’ by making individual acquisitions that escape regulatory scrutiny but whose cumulative effect might still be large (Australia, 2024; FTC Challenges Private Equity Firm’s Scheme to Suppress Competition in Anesthesiology Practices Across Texas, 2023; Buri et al., Reference Buri, Heinonen and Pietola2024). In other health care sectors such as hospitals and elder care, PE firms have used financial strategies such as sale-leaseback arrangements, whereby PE firms sell the real estate assets of the acquired entity and lease them back to the acquired entity in exchange for rental payments. This strategy allows firms to unlock capital while retaining operational control, raising concerns about the long-term financial stability of health care institutions. At present, there are no systematic reporting or disclosure requirements for PE acquisitions in health care (Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Schulmann, Tille, Rice, Mercille, Timans, Allin, Dottin, Syrjälä, Sotamaa, Keskimäki and Rechel2025). Consequently, policymakers and regulators do not have a systematic understanding of the trends and effects of PE involvement in health care.

Given these concerns, in recent years, a nascent literature has emerged to examine PE acquisitions in health care, largely focused on the United States. PE in healthcare has been a subject of debate, particularly in the U.S., where studies have shown PE’s profit-driven approach can drive increases in healthcare costs with implications for patients and health care workers (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023; R. Scheffler et al., Reference Scheffler, Alexander, Fulton, Arnold and Abdelhadi2023; Singh, Aderman, Song, Polsky, et al., Reference Singh, Aderman, Song, Polsky and Zhu2024; Singh, Reddy, & Zhu, Reference Singh, Reddy and Zhu2024; Singh, Song, et al., Reference Singh, Song, Polsky, Bruch and Zhu2022; Singh, Zhu, et al., Reference Singh, Zhu, Polsky and Song2022a). PE’s abbreviated investment timeline and profit incentives have also raised concerns that PE may deter long-term investments in care delivery needed for high-quality patient outcomes (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Howell, Yannelis and Gupta2021; Kannan et al., Reference Kannan, Bruch and Song2023). Within the US, these concerns have been the basis of multiple federal and state investigations into the impact of PE in health care (Assistant Secretary for PublicAffairs (ASPA), 2024; Markey & Braun, Reference Markey and Braun2024; R. Scheffler & Blumenthal, Reference Scheffler and Blumenthaln.d.; Senate Budget Committee Digs into Impact of Private Equity Ownership in America’s Hospitals | U.S. Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, n.d.).

While the existing research has remained largely focused on the US, early evidence suggests that PE firms have made substantial inroads in health care in countries with various approaches to the regulation, financing, and delivery of health care (Singh, Brown, et al., Reference Singh, Brown and Papanicolas2025). However, despite anecdotal evidence of PE investments in health care across many high-income countries, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic research has examined the extent of these trends outside of the US. Country-specific studies of PE-investment are sparse, reinforcing a need for more country-specific evidence to inform researchers, policymakers, and regulators about the extent of PE penetration within the market, the distribution of investment across geographic areas, and the types of health care segments affected.

In this context, the objective of our study is three-fold: first, we combine novel data sources to provide an overview of the trends in PE investments in healthcare across selected high-income countries that form the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). We examined both the number of PE deals in health care as well as the amount of capital invested by PE firms across key healthcare sectors – such as hospitals, outpatient clinics, and elder care. By doing so, we identify patterns of financialisation that will be important for policymakers and regulators to monitor. Second, using fixed effects regressions we conducted an exploratory analysis to determine the broader economic environment that is associated with PE activity in health care, considering factors such as per capita income, the proportion of health spending derived from the private sector, and demographic characteristics. Finally, we reviewed the grey literature to identify notable PE deals in selected OECD countries that serve as illustrative examples of the operational, financial, and social implications of these investments, as well as the regulatory context within which investments take place.

In doing so, this paper aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse on the financialisation of health care (Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Paris, Joshi and Dedet2025). As governments grapple with healthcare financing and delivery challenges, understanding the extent of PE penetration in individual countries will enable policymakers and regulators to determine to what extent this is a problem to be monitored. Second, this work will provide a foundation for a comparative analysis of PE’s role in diverse health care systems to enhance our understanding of how different regulatory environments and health system structures interact with private investment in health care to influence patient health.

2. Literature review

The existing research on PE investment in healthcare is small but growing and largely limited to reporting from the US (see Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023 for a broad review). A key challenge faced by researchers conducting empirical studies on this topic is the lack of systematic disclosure or reporting requirements for PE transactions that limits the ability of researchers to assemble a dataset of sufficient detail and scope to credibly identify PE investments. Nonetheless, a nascent literature examining PE investments in health care has emerged. Below we summarise key findings from empirical English language studies published in peer-reviewed academic journals as of May 2025. Academic literature was identified by searches of Google Scholar, PubMed, ProQuest, and EBSCO Host databases using the keywords ‘private equity’, ‘real estate investment trust’, ‘REIT’, ‘leveraged buyout’, and ‘LBO’ in combination with ‘long-term care’, ‘long-term care’, ‘nursing homes’, ‘care homes’, ‘healthcare’, ‘health care’, and ‘OECD’. Grey literature was identified through Google and company websites using the same keywords.

2.1. PE investments in health care: evidence from the US

In the United States, as of 2023, PE firms have acquired 5% of nursing homes (Office, Reference Officen.d.), 8% of hospitals (PESP Private Equity Hospital Tracker, n.d.). In addition, approximately 5%–13% of physicians are estimated to be working in PE-acquired outpatient (physician) practices (Abdelhadi et al., Reference Abdelhadi, Fulton, Alexander and Scheffler2024; Singh, Bejarano, Torabzadeh, Whaley, et al., Reference Singh, Bejarano, Torabzadeh, Whaley and Borkar2025; Singh, Cantor, Brown, & Whaley, Reference Singh, Cantor, Brown and Whaley2025; Singh, Radhakrishnan, et al., Reference Singh, Radhakrishnan, Adler and Whaley2025; Singh, Reddy, & Whaley, Reference Singh, Reddy and Whaley2024; Singh, Zhu, et al., Reference Singh, Zhu, Polsky and Song2022b). PE’s abbreviated investment timeline and profit incentives has raised concerns that PE may deter long-term investments in care delivery needed for high-quality patient outcomes (R. M. Scheffler & Abdelhadi, Reference Scheffler and Abdelhadi2023). In addition, mounting evidence links PE investments in health care to consolidation in outpatient settings and to financial restructuring practices – such as the separation of real estate and operations in hospitals and long-term care facilities – that have contributed to asset depletion, facility closures, and in some cases, adverse patient outcomes. These concerns have been the basis of multiple federal and state investigations into the impact of PE in health care (Haryanto, Reference Haryanto2022; HB4130 2024 Regular Session – Oregon Legislative Information System, n.d.; Hearing Details - Joint Committee on Health Care Financing, n.d.; ‘Peters Seeks Information About Private Equity Run Emergency Departments and Impact on Patient Care’, n.d.; Private Capital, Public Impact, 2024; Senate Budget Committee Digs into Impact of Private Equity Ownership in America’s Hospitals | U.S. Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, n.d.; R. Scheffler & Blumenthal, Reference Scheffler and Blumenthaln.d.; R. M. Scheffler et al., Reference Scheffler, Alexander and Godwin2021, Reference Scheffler, Alexander and Godwin2021; Singh & Brown, Reference Singh and Brown2023; Subbiah & Scheffler, Reference Subbiah and Scheffler2025).

Research on PE in health care in the US has found that PE acquisitions of outpatient practices targeted specialties such as dermatology, gastroenterology, and ophthalmology and resulted in increased health care spending and patient utilisation (Abdelhadi et al., Reference Abdelhadi, Fulton, Alexander and Scheffler2024; Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Fulton, Abdelhadi, Teotia and Scheffler2025; Braun et al., Reference Braun, Bond, Qian, Zhang and Casalino2021; La Forgia et al., Reference La Forgia, Bond, Braun, Yao, Kjaer, Zhang and Casalino2022; Singh, Aderman, Song, Polsky, et al., Reference Singh, Aderman, Song, Polsky and Zhu2024; Singh, Radhakrishnan, et al., Reference Singh, Radhakrishnan, Adler and Whaley2025; Singh, Song, et al., Reference Singh, Song, Polsky, Bruch and Zhu2022, Reference Singh, Song, Polsky and Zhu2025; Singh, Zhu, et al., Reference Singh, Zhu, Polsky and Song2022b). In other settings related to elder care, PE acquisition in nursing homes is associated with changes to staffing levels and mixed effects on outcomes for residents (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Yun, Casalino, Myslinski, Kuwonza, Jung and Unruh2020; Gandhi et al., Reference Gandhi, Song and Upadrashta2020; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Howell, Yannelis and Gupta2021; Huang & Bowblis, Reference Huang and Bowblis2019) while PE acquisition of hospitals is associated with improvements in financial outcomes and changes to offered services based on profitability (Bhatla et al., Reference Bhatla, Bartlett, Liu, Zheng and Wadhera2025; Bruch et al., Reference Bruch, Gondi and Song2020; Cerullo et al., Reference Cerullo, Yang, Roberts, McDevitt and II2021, Reference Cerullo, Yang, Maddox, McDevitt, Roberts and Offodile2022; Kannan et al., Reference Kannan, Bruch and Song2023).

The impact of PE acquisitions on patient outcomes is setting specific. Some studies have found worsening quality following PE acquisition, finding a 25% increase in hospital-acquired adverse events (Kannan et al., Reference Kannan, Bruch and Song2023) and an 11% rise in mortality in PE-owned nursing homes (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Howell, Yannelis and Gupta2021). Others, such as Cerullo et al., Reference Cerullo, Yang, Maddox, McDevitt, Roberts and Offodile2022, found improvements in mortality following myocardial infarction at PE-acquired hospitals, though no gains were seen for other conditions or metrics.

Finally, recent studies have highlighted the implications of PE acquisitions for the health care workforce. Bruch et al., Reference Bruch, Foot, Singh, Song, Polsky and Zhu2023, found increased use of advanced practice providers (e.g., nurse practitioners) in PE-owned practices, likely reflecting cost cutting strategies. A study by Singh, Bejarano, Torabzadeh, Borkar, et al., Reference Singh, Bejarano, Torabzadeh, Borkar and Whaley2025, found that PE-acquired ophthalmology practices saw a 265% increase in physician turnover and a shift in staffing, with greater reliance on non-physician providers. While the study also documented clinician growth post-acquisition, the high churn raises concerns about continuity of care and long-term workforce stability (Berquist et al., Reference Berquist, Klarnet and Dafny2025; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Bejarano, Torabzadeh, Borkar and Whaley2025).

2.2. PE investments in health care: a global perspective

Despite its importance, empirical research on PE investments in health care in countries outside of the US remain limited. In contrast to the growing evidence base on PE investments in health care in the US, we identified only 9 peer-reviewed articles on PE investments in health care outside of the US (excluding commentary/opinion pieces and the grey literature). Among these 9 studies, 4 studies highlighted the growth of PE investments in outpatient clinics in Australia, Finland, Sweden, and Ireland and 4 studies highlighted the trends in PE investments in elder care, focusing on investments in Sweden and the UK (see Appendix Table 1).

Outpatient practices have emerged as an attractive investment target across several countries. In Australia, PE investments have targeted fragmented and high-margin sectors like general practice and oncology, completing 75 deals worth AUD 24.1 billion between 2008 and 2022 (Berquist, Reference Berquist2024). To date, PE investments in health care in Australia have proceeded with minimal regulatory scrutiny and the long-term implications of these investments for access and quality of care remain unexamined (Australia, 2024). In Sweden, a 2010 reform introduced patient choice and opened primary care to private ownership. By 2020, 40% of clinics were privately operated, and one-third backed by international PE firms (Winblad, Reference Winblad2023). Despite the growth in PE-owned clinics, research on the effects of such acquisitions remains limited. The one exception is a study that examined 200 PE deals or ‘stealth consolidation’ (i.e., deals often structured to avoid merger scrutiny) in Finland between 2008–2020, (Buri et al., Reference Buri, Heinonen and Pietola2024). The study found PE acquisitions led to 10%–20% price increases through chain-wide price harmonisation – even without increasing market concentration – highlighting the different mechanisms PE firms may deploy to increase prices at target facilities.

In other countries such as Germany, The Netherlands, and Ireland, PE investment is growing although detailed data and studies remain scarce. In Germany, PE investments have grown substantially in outpatient medical centres (Medizinische Versorgungszentren or MVZs), with estimates suggesting that nearly one-fifth were under PE ownership by 2020 (Rechel et al., Reference Rechel, Tille, Groenewegen, Timans, Fattore, Rohrer-Herold, Rajan and Lopes2023). In The Netherlands, commercial GP chains – some PE-backed – now operate 45 to 230 of the country’s 4,874 practices, replacing traditional self-employed models with salaried employment (Commercial Chains in General Practice. | Nivel, n.d.). In Ireland, international investors have financed and leased public primary care centres under long-term contracts, raising concerns about the long-run fiscal implications of these arrangements for the state, raising questions about long-term value for the public sector (Rechel et al., Reference Rechel, Tille, Groenewegen, Timans, Fattore, Rohrer-Herold, Rajan and Lopes2023, O'Neill & Mercille, Reference O'Neill and Mercille2025).

In addition to outpatient practices, elder care facilities have also attracted PE investments in selected countries. In England, research studies have examined PE-acquired care homes, finding lower quality at PE-acquired care homes relative to not-for-profit care homes (Patwardhan et al., Reference Patwardhan, Sutton and Morciano2022). However, evidence on quality implications of PE acquisitions of elder care facilities remains mixed and may have limited generalisability. For example, in Sweden, one study found marginal quality differences between public, non-profit, and PE-owned nursing homes (Winblad et al., Reference Winblad, Blomqvist and Karlsson2017).

Overall, the empirical literature on the effects of PE investments in health care raises concerns about adverse effects on competition, costs, and the clinical workforce. However, much of the existing research is based on the United States. Country-specific studies of PE-investment are sparse, reinforcing a need for more country-specific evidence to inform policymakers about the extent of PE penetration within the market, the distribution of investment across geographic areas and regulatory structures, and the types of health care segments affected to inform policy on this issue.

3. Data & methods

Our primary source of data on PE transactions is a proprietary list of acquisitions in the health care sector compiled by PitchBook, a financial database that tracks mergers and acquisitions across industries and has been used by several other studies examining PE investments in health care (Abdelhadi et al., Reference Abdelhadi, Fulton, Alexander and Scheffler2024; Bhatla et al., Reference Bhatla, Bartlett, Liu, Zheng and Wadhera2025; Braun et al., Reference Braun, Yun, Casalino, Myslinski, Kuwonza, Jung and Unruh2020; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Howell, Yannelis and Gupta2021; Kannan et al., Reference Kannan, Bruch and Song2023; Offodile et al., Reference Offodile, Cerullo, Bindal, Rauh-Hain and Ho2021; R. Scheffler et al., Reference Scheffler, Alexander, Fulton, Arnold and Abdelhadi2023; Singh, Song, et al., Reference Singh, Song, Polsky, Bruch and Zhu2022). PitchBook compiles information from a combination of public and proprietary sources, including regulatory filings, press releases, news reports, investor presentations, and voluntary disclosures from PE firms, portfolio companies, and limited partners. While PitchBook maintains global coverage, data completeness is highest in regions with English-language financial reporting – particularly the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. Coverage in other regions, including Europe and Asia, has expanded in recent years through localised data collection and partnerships (How PitchBook Collects Data, n.d.). Given that there is no single data source that tracks the complete universe of PE acquisitions, a limitation of this data is that it might under-report some PE acquisitions. In particular, it is likely that PitchBook data underestimates deal count and valuation, most notably of smaller transactions.

We obtained data on PE investments from 2013–2023 from PitchBook via a data use agreement in January 2025. This data from PitchBook included the name and a description of the acquired firm, geographic location of the acquired firm, a description of the deal, and the announcement date of the deal. We included PE transactions in the following sectors: ‘Clinics and outpatient services’, ‘Elder and Disabled Care’, ‘Hospital and inpatient services’, ‘Laboratory services’, and ‘Other’. Data from the OECD served as our primary data source for country-specific variables, including income per capita, health expenditures as a percent of GDP, out-of-pocket expenditures as a percent of health expenditures, and population size.

Using data from PitchBook, we calculated two variables for every country in our sample from 2013–2023: the total number of reported PE deals and the total amount of capital invested. Given the lack of systematic disclosure requirements for PE transactions, many deals did not have reported deal valuation (see appendix Table 2 for proportion of deals without disclosed deal valuation). Thus, we estimated the total amount of capital invested as the sum of reported deal values and imputed deal values. To calculate imputed deal values for deals without a reported deal value, we relied on the median deal value within each country-year pair.

In exploratory analysis, we developed regression models to examine the growth of PE at the extensive and intensive margin. First, to examine the extensive margin, we examined the factors associated with moderate to high degree of PE activity across countries. The dependent variable was a binary variable equal to 1 for countries with over 50 reported deals during our study period, and 0 otherwise. In sensitivity analysis, we varied the threshold to examine countries with over 30 reported deals as well as over 100 reported deals.

The independent variables included a country’s income, health expenditures as a share of total GDP, the percentage of a country’s health expenditures that are paid out-of-pocket, and population size. To account for variation in health system design across countries, we categorised each country’s health system into three mutually exclusive categories: Market-Based/Hybrid, Tax-Based, and Social Health Insurance (SHI). To do so, we relied on OECD data on the percentage of total health expenditures accounted for by the government, social health insurance, and compulsory and voluntary private schemes.

Second, we examined the intensive margin by examining the factors associated with the number of PE deals in health care. To do so, we estimated fixed effects regressions in exploratory analysis to examine the association between country-specific variables and the number of reported PE deals. Previous studies have shown overall economic growth to be a strong predictor of health expenditures (Baltagi & Moscone, Reference Baltagi and Moscone2010; Newhouse, Reference Newhouse1977). As such, we expect a country’s income to be positively related to the number of reported deals and total capital invested.

In addition to income, we include three measures that account for the health coverage and demographics of a country: health expenditures as a share of total GDP and the percentage of a country’s health expenditures that are paid out-of-pocket. To account for country demographics, we controlled for the size of the population in each country. We expect the share of health expenditures that are paid out-of-pocket to be negatively associated with the number of reported deals. This is because we hypothesise that PE firms might prefer to invest in sectors with predictable revenue streams, either through third-party payers and/or amenable to contracting and margin improvements. Such conditions are less common where households pay a large share of costs out of pocket.

The unit of analysis for regression analysis was the country-year. Country fixed effects were included to account for time-invariant unobservable heterogeneity across countries. In sensitivity analysis, we examined the robustness of results to the exclusion of country fixed effects, models with only calendar year fixed effects, and models with both country and year fixed effects. Across all specifications, we clustered standard errors by country as model errors across years for a given country are likely correlated.

4. Limitations

Several limitations are worth noting. First, our data may not have captured all PE acquisitions given the lack of systematic reporting and disclosure requirements for PE investments. Second, deal valuation was not disclosed for several deals and our imputation approach to estimate total capital invested (imputed) are rough approximations and might underestimate the true extent of PE activity. Given this, we consider data on the number of deals to be more reliable than deal valuation. Third, there are important limitations to the PitchBook data. While PitchBook maintains global coverage, data completeness is highest in regions with English-language financial reporting. In addition, PitchBook data might underestimate smaller transactions. Fourth, data from the OECD was not systematically reported for some years and countries. As a result, our exploratory regression analysis might not be adequately powered to detect all associations of interest. Fifth, our regression analysis is exploratory in nature and, as such, we were unable to examine the role of country-specific or sector-specific regulatory factors that can incentivise or deter PE investments. Future research can separately examine country-specific factors that shape PE activity, including regulatory environment, payment policies, investment environment, to name a few. Finally, PitchBook data were only available through 2023, precluding analysis of recent acquisitions, the role of the COVID-19 pandemic, effects of subsequent buyouts, and other trends that might exacerbate observed trends.

5. Results

5.1. Trends in PE investments in OECD countries

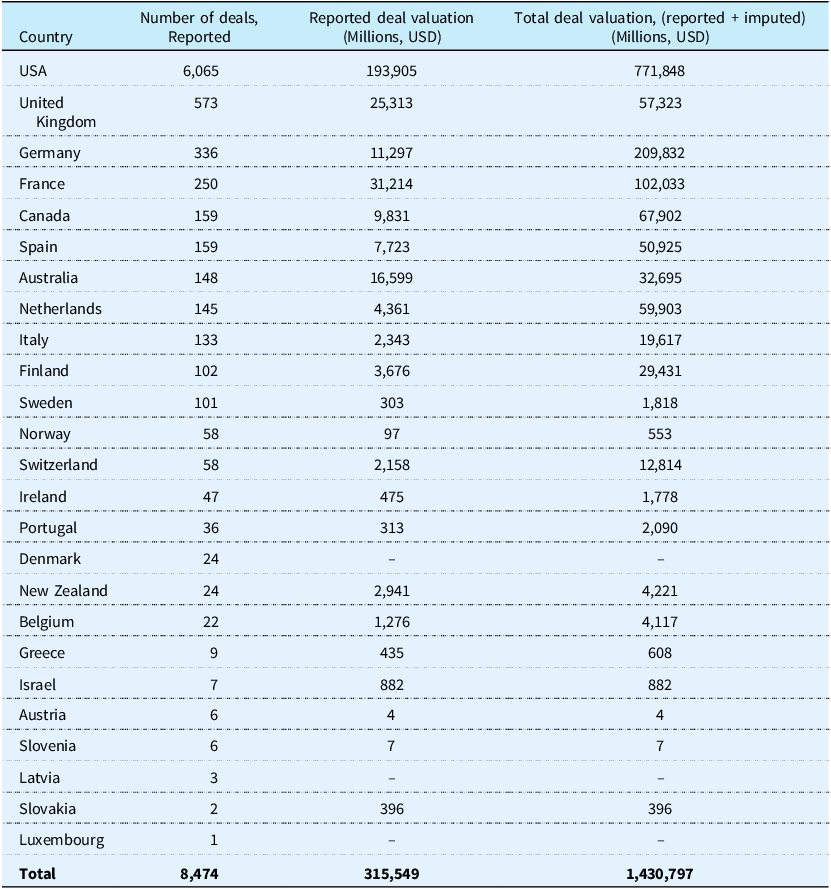

Among 38 OECD countries, we identified 8,474 reported PE deals in 25 countries with total deal valuation (i.e., the sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation) exceeding $1.4 trillion during 2013–2023 (Table 1). The largest number of reported deals in our sample were in the United States (6,065 deals in 2013–2023). The top three countries with the largest number of reported deals outside the US were the United Kingdom (573 deals and $771 billion in capital invested), Germany (336 deals and $209 billion in capital invested), and France (250 deals and $102 billion in capital invested). Thirteen countries had no reported PE deals: Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Iceland, Japan, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland, South Korea, Turkey. For the remainder of the analysis, we focused on countries with at least 50 deals between 2013–2023: Australia, France, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom, USA, Canada, Finland, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden.

Table 1. Reported private equity deals and deal valuation in selected OECD countries, 2013–2023

Notes/Sources: Authors’ calculation of data obtained from PitchBook. Number of reported deals includes reported private equity deals between 2013–2023 in the following sectors: “Clinics and outpatient services,” “Elder and Disabled Care”, “Hospital and inpatient services,” “Laboratory services”, “Managed Care”, “Practice Management (Healthcare)”, and “Other Healthcare Services.” Reported deal valuation represents the disclosed sum of capital invested by PE firms across all reported deals. Given the lack of systematic disclosure requirements for PE deals, many deals did not have reported deal valuation. Total deal size is estimated as the sum of reported deal value and imputed deal value, where the imputed deal values is calculated as the median deal value within each country and year. Given the lack of systematic reporting requirements for private equity deals, the total number of deals, particularly the number of smaller deals, may be an underestimate. ‘–’ represents no reported information. The following countries have been excluded from the table as they were reported to have no private equity deals in health care: Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Iceland, Japan, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland, South Korea, Turkey.

Figure 1 shows that across evaluated countries, reported PE investments in health care steadily increased since 2013, accelerating around the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2021. At the same time total capital invested (sum of disclosed and imputed valuation) peaked in 2022. Appendix Figures 1–13 show variation in the number of reported PE deals and capital invested by PE firms across countries. While the number of PE deals appear to be consistently reported across countries, many countries do not have sufficient reporting on deal valuation (Appendix Table 2).

Figure 1. Growth in reported PE deals and capital invested in health care and elder care in selected OECD countries, 2013–2023. Notes/Sources: Authors’ calculation of data obtained from PitchBook. Number of reported deals includes reported private equity deals between 2013–2023 in the following sectors: “Clinics and outpatient services,” “Elder and Disabled Care”, “Hospital and inpatient services,” “Laboratory services”, “Managed Care”, “Practice Management (Healthcare)”, and “Other Healthcare Services.” Analysis is limited to 13 countries with at least 50 reported deals during 2013–2023, excluding the United States: Australia, France, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Canada, Finland, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden. Given the lack of systematic disclosure requirements for PE deals, many deals did not have reported deal valuation. Total deal size is estimated as the sum of reported deal value and imputed deal value, where the imputed deal values is calculated as the median deal value within each country and year. Given the lack of systematic reporting requirements for private equity deals, the total number of deals, particularly the number of smaller deals, may be an underestimate.

Further, Figure 2 shows different growth trajectories in reported PE deals across the countries our sample. Consistent with Table 1, the countries that appear to have experienced the fastest growth in reported PE deals since 2013 are the United Kingdom, Germany, and France.

Figure 2. Trends in reported PE deals in health care and elder care in selected OECD countries, 2013–2023. Notes/Sources: Authors’ calculation of data obtained from PitchBook. Number of reported deals includes reported private equity deals between 2013–2023 in the following sectors: “Clinics and outpatient services,” “Elder and Disabled Care”, “Hospital and inpatient services,” “Laboratory services”, “Managed Care”, “Practice Management (Healthcare)”, and “Other Healthcare Services.” Analysis is limited to 12 countries with at least 50 reported deals during 2013–2023, excluding the United States. Given the lack of systematic reporting requirements for private equity deals, the total number of deals, particularly the number of smaller deals, may be an underestimate.

While PE activity is significant and growing across high-income countries, there is wide variation in the sectors that attract PE investments. Figure 3 highlights variation in the sectors that have attracted the largest number of deals within each country during our study period. For example, outpatient clinics have attracted the largest share of PE deals in many countries followed by deals in elder care (e.g., UK). PE acquisition of hospitals emerges as a notable share of overall deal volume in selected countries such as France, Germany, and Spain.

Figure 3. Reported PE deals by country and sector, 2013–2023. Notes/Sources: Authors’ calculation of data obtained from PitchBook. Number of reported deals includes reported private equity deals between 2013–2023 in the following sectors: “Clinics and outpatient services,” “Elder and Disabled Care”, “Hospital and inpatient services,” and “Laboratory services”. Analysis is limited to 13 countries with at least 50 reported deals during 2013–2023: Australia, France, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Canada, Finland, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden, and the USA. Given the lack of systematic reporting requirements for private equity deals, the total number of deals, particularly the number of smaller deals, may be an underestimate.

Figure 4 summarises the involvement of domestic and foreign PE firms in health care investments in our countries of interest. Domestic PE firms are defined as PE firms that are headquartered in the same country as the investment target. Conversely, foreign PE firms are defined as PE firms headquartered in a different country than the investment target. Figure 4 highlights a few key findings. First, all countries in our sample receive PE investments from both domestic and foreign PE firms. Second, most PE investments are made by domestic PE firms in five countries – 68.0% PE deals in Australia are backed by Australian PE firms, 68.3% PE deals in Canada are backed by Canadian PE firms, 60.9% deals in France, 64.1% deals in the UK, and 90.3% deals in the US. Third, PE firms headquartered in the US and UK comprise a large share of PE deals in health care globally. US-based PE firms comprise greater than 10.0% of deals in several countries outside the US, including Australia (11.4%), Canada (19.4%), Germany (11.7%), and Spain (12.7%). Similarly, UK-based PE firms comprise greater than 10% of deals in France (11.3%), Italy (25.2%), The Netherlands (12.3%), and Spain (12.0%). Finally, Germany is the only country in our sample for which no single PE firm accounts for at least 25% of deal volume.

Figure 4. Domestic and foreign PE firms investing in health care in selected OECD countries, 2013–2023. Notes/Sources: Authors’ calculation of data obtained from PitchBook. The horizontal axis summarises the number of reported private equity deals in each country. The colours represent the country where PE firms are headquartered. Number of reported deals includes reported private equity deals between 2013–2023 in the following sectors: “Clinics and outpatient services,” “Elder and Disabled Care”, “Hospital and inpatient services,” “Laboratory services”, “Managed Care”, “Practice Management (Healthcare)”, and “Other Healthcare Services.” Analysis is limited to 12 countries with at least 50 reported deals during 2013–2023.

5.2. Country-specific trends in PE investments in health care

5.2.1. Australia

PE investments in health care in Australia steadily increased from 2013, increasing from 6 deals to a cumulative 148 deals between 2013–2023 (Appendix Figure 1). Over the same period, PE firms have invested approximately 32.7 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for the largest proportion of PE deals in health care (45%), followed by elder care (20%) (Appendix Figure 14). Hospitals and laboratory services accounted for 11% and 10% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.2. Canada

PE investments in health care in Canada increased from 9 deals to a cumulative 159 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2021 (Appendix Figure 2). Over the same period, PE firms have invested approximately 67.9 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for nearly two-third of all PE deals in health care (65%) followed by elder care (7%) (Appendix Figure 15). Hospitals and laboratory services accounted for 4% and 6% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.3. Finland

We identified 102 reported PE investments in health care in Finland between 2013-2023, with deal volume peaking between 2015–2017 (Appendix Figure 3). Between 2013–2023, PE firms have invested approximately 29.4 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for nearly two-third of all PE deals in health care (56%) followed by elder care (25%) (Appendix Figure 16). Hospitals and laboratory services accounted for less than 3% of deal volume each.

5.2.4. France

PE investments in health care in France increased from 15 deals to a cumulative 250 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2021 (Appendix Figure 4). Over the same time period, PE firms have invested approximately 102.0 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for the largest proportion of PE deals in health care (27%), followed by laboratory services (24%) (Appendix Figure 17). Hospitals and elder care accounted for 16% and 15% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.5. Germany

PE investments in health care in Germany increased from 13 deals to a cumulative 336 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2021 (Appendix Figure 5). Over the same time period, PE firms have invested approximately 209.8 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for over half of all PE deals in health care (51%), followed by elder care (14%) (Appendix Figure 18). Hospitals and laboratory services accounted for 12% and 9% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.6. Italy

PE investments in health care in Italy increased from 2 deals in 2013 to a cumulative 133 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2023 (Appendix Figure 6). Over the same time period, PE firms invested approximately 19.6 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for nearly half of all PE deals in health care (47%) followed by laboratory services (29%) (Appendix Figure 19). Hospitals and elder care accounted for 5% of deal volume each.

5.2.7. The Netherlands

PE investments in health care in The Netherlands increased from 3 deals in 2013 to a cumulative 145 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2022 (Appendix Figure 7). Over the same time period, PE firms invested approximately 59.9 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for nearly two-third of all PE deals in health care (59%) followed by laboratory services (6%) (Appendix Figure 20). Elder care and hospitals accounted for 5% and 3% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.8. Norway

PE investments in health care in Norway ranged from 2 deals to a cumulative 58 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2016 (Appendix Figure 8). Over the same time period, PE firms have invested approximately 553 million dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for nearly two-thirds of all reported PE deals in health care (64%), followed by elder care (21%) (Appendix Figure 21). Hospitals accounted for approximately 2% of total deal volume. There were no reported PE deals of laboratory services.

5.2.9. Spain

PE investments in health care in Spain increased from 6 deals in 2013 to a cumulative 159 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2023 (Appendix Figure 9). Over the same time period, PE firms have invested approximately 50.9 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for half of all PE deals in health care (50%) followed by elder care (15%) (Appendix Figure 22). Hospitals and laboratory services accounted for 14% and 6% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.10. Sweden

PE investments in health care in Sweden increased from 15 deals in 2013 to a cumulative 101 deals between 2013–2023 (Appendix Figure 10). Over the same period, PE firms have invested approximately 1.8 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for half of all PE deals in health care (60%) followed by elder care (11%) (Appendix Figure 23). Hospitals and laboratory services accounted for 4% and 1% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.11. Switzerland

We identified a cumulative 58 deals between 2013–2023 (Appendix Figure 11). Over the same period, PE firms have invested approximately 12.8 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for the majority of all reported PE deals in health care (60%), followed by laboratory services (17%) (Appendix Figure 24). Hospitals accounted for approximately 2% of total deal volume. Elder care and hospitals accounted for 10% and 5% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.12. United Kingdom

PE investments in health care in the United Kingdom have increased from 34 deals to a cumulative 573 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2022 (Appendix Figure 12). Over the same period, PE firms have invested approximately 57.3 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for over one-third of all PE deals in health care (36%), followed by elder care (29%) (Appendix Figure 25). Hospitals and laboratory services accounted for 4% and 6% of deal volume, respectively.

5.2.13. United States

PE investments in health care in the US have increased from 192 deals to a cumulative 6,065 deals between 2013–2023, with deal volume peaking in 2021 (Appendix Figure 13). Over the same time period, PE firms have invested approximately 577 billion dollars in health care (sum of disclosed and imputed deal valuation). Between 2013–2023, outpatient clinics accounted for nearly two-third of all PE deals in health care (60%), followed by elder care (10%) (Appendix Figure 26). Hospitals and laboratory services accounted for 5% and 3% of deal volume, respectively.

5.3. Exploratory analysis of factors associated with the number of deals

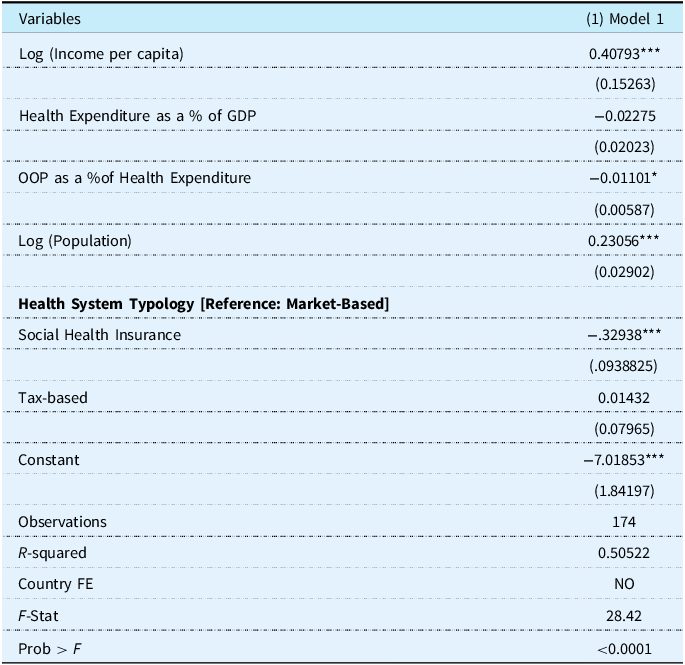

To examine the extensive margin, we used regression analysis to examine the factors associated with a country experiencing high PE penetration, defined as a binary variable equal to 1 for countries with over 50 reported PE deals in our study period and 0 otherwise. We find that income per capita and population size have a positive and significant association with high PE penetration. Conversely, the share of health expenditures paid out-of-pocket have a negative and significant association with high PE penetration (Table 2). Relative to countries with a market-based health system, countries with a social health insurance system have lower likelihood of high PE penetration. Results are consistent after varying the threshold of ‘high PE penetration’ to examine countries with over 30 reported deals as well as over 100 reported deals (Appendix Table 3).

Table 2. Association of likelihood of high PE penetration with country-specific factors

Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Notes/Sources: Authors’ calculation of data obtained from PitchBook and the OECD from 2013–2023. Analysis includes all OECD countries. The dependent variable takes a value of 1 for 13 countries with at least 50 reported deals during 2013–2023: Australia, France, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Canada, Finland, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden, and the USA. The dependent variable is the log-transformed number of reported private equity deals. The independent variables are log-transformed income per capita, health expenditure as a proportion of GDP, out-of-pocket spending as a proportion of health expenditures, log-transformed population size, and health system type (Market-based/Hybrid, Social Health Insurance, and Tax-Based).

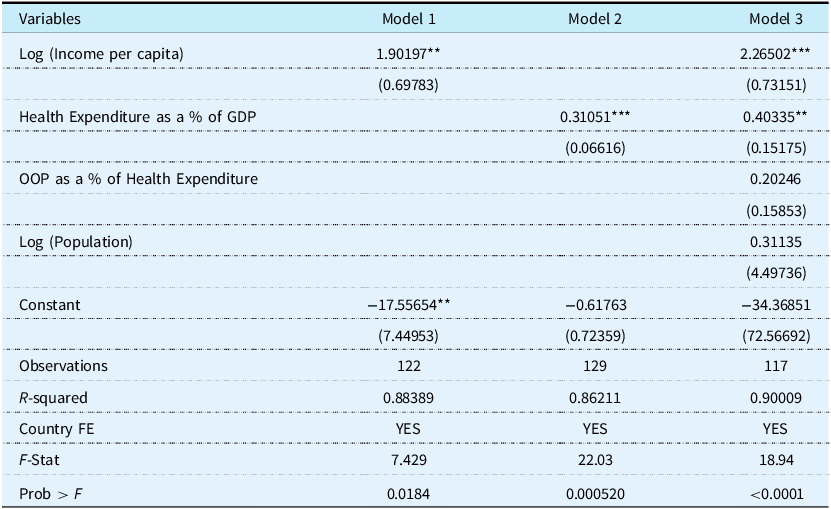

The estimates from our intensive margin regression analysis are presented in Table 3. The R2, measure of fit, was 0.88, which signals a good fit (Model 1). In Model 1, both the dependent variable and independent variable are log-transformed, thus the coefficient on income can be interpreted as an elasticity. In Model 1, a coefficient of 1.90 implies that a 1% increase in income per capita is associated with a 1.90% increase in the number of reported PE deals.

Table 3. Association of the log-transformed number of private equity deals with country-specific factors

Robust standard errors in parentheses: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Notes/Sources: Authors’ calculation of data obtained from PitchBook and the OECD from 2013–2023. Analysis is limited to 13 countries with at least 50 reported deals during 2013–2023: Australia, France, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Canada, Finland, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden, and the USA. The unit of analysis is the country-year. The dependent variable is the log-transformed number of reported private equity deals. The independent variables are log-transformed income per capita, health expenditure as a proportion of GDP, out-of-pocket spending as a proportion of health expenditures, and log-transformed population. The unit of analysis is the country-year. All regressions include country fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the level of the country.

In Model 2, a coefficient of 0.31 implies that a one unit increase in the share of GDP accounted for by health expenditures is associated with a 36% increase in the number of reported PE deals (i.e., exp (0.31) = 1.36). These findings are consistent after accounting for the population size of the country as well as the proportion of out-of-pocket spending (Model 3). After accounting for population size (Model 3), a 1% increase in income per capita is associated with a 2.26% increase in the number of reported PE deals (p < 0.01) and a one percentage point increase in health expenditure as a % of GDP is associated with a 49% increase in the number of reported PE deals (p < 0.05) (exp(0.403) = 1.49). Across all sensitivity analyses, there is a positive and significant association between the size of the health sector (i.e., health expenditure as a % of GDP) and the number of reported PE deals (Appendix Table 4).

Further, to better visualise results, we plotted the fitted values obtained from Model 3 against observed values of the number of reported PE deals and income per capita (both in logs). Results are summarised in Figure 5. For the US, UK, Germany, and France, the observed value is greater than the predicted (fitted) value, suggesting that the regression model might be underestimating the actual outcome for these countries. In other words, the reported PE deal volume in these countries is likely influenced by country-specific idiosyncratic features not captured by our model, such as regulatory environment, payment policies, contracting practices, to name a few.

Figure 5. Observed and fitted values of log-transformed number of reported private equity deals and income per capita (log). Notes/Sources: Authors’ calculation of data obtained from PitchBook and the OECD from 2013–2023. Analysis is limited to 13 countries with at least 50 reported deals during 2013–2023: Australia, France, Germany, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Canada, Finland, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden, and the USA. The unit of analysis is the country-year. Fitted values are obtained from Model 3 in Table 3. The dependent variable is the log-transformed number of reported private equity deals.

6. Illustrative examples of notable deals across countries

This section highlights illustrative examples of PE deals across countries (see Appendix Table 5 for a summary). The examples represent sectors with the highest PE activity in a given country. A specific deal is chosen based on the frequency of the PE firm and/or platform company appearing in the dataset, along with transaction value, if available. Country-specific case studies were developed primarily from desk research, drawing on multiple sources including company profiles from PitchBook, peer-reviewed studies, industry and consultancy reports, government documents, and credible news media. We were unable to identify research studies or systematic data on patient or health care workers affected by the transactions described below.

6.1. United States: private equity ownership of steward health care

6.1.1. Acquisition overview

Steward Health Care, a private hospital company based in the United States, was formed in 2010 when the PE firm Cerberus Capital Management bought six struggling hospitals in Massachusetts from the non-profit Caritas Christi Health Care system through a leveraged buyout. (‘Massachusetts Passes Healthcare Oversight Legislation in Response to Steward Health Care Crisis’, 2025). As part of the deal, Cerberus promised major capital investments, but these were financed through large loans that the hospitals – not Cerberus – were responsible for repaying. Over the next decade, Steward expanded rapidly, eventually operating over 30 hospitals across the country, making it one of the largest for-profit hospital systems in the U.S. (The Steward Health Care Report | U.S. Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts, n.d.).

In 2016, Steward executed a $1.2 billion sale-leaseback deal with Medical Properties Trust (MPT), transferring the real estate of nine Massachusetts hospitals and committing to long-term rent payments. In 2020, Cerberus sold its ownership to a management/physician-led group headed by Dr. Ralph de la Torre (‘Massachusetts Passes Healthcare Oversight Legislation in Response to Steward Health Care Crisis’, 2025). In 2021–2022, Steward continued to rely on real estate and debt financing, including a recapitalisation of Massachusetts hospitals backed by MPT and Apollo Global Management. Meanwhile, Massachusetts regulators repeatedly criticised Steward for refusing to submit audited financial statements for years, even as concerns about its solvency grew (Steward Health News, n.d.). In 2024, Steward filed for bankruptcy with $6.6 billion of its $9 billion in reported liabilities driven by long-term lease liabilities. Amidst Steward’s financial turmoil, between 2014 and 2024, at least eight Steward hospitals closed, eliminating over 1,500 beds and more than 4,400 jobs (The Steward Health Care Report | U.S. Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts, n.d.). Moreover, Steward’s bankruptcy resulted in closures or emergency state takeovers of several hospitals. These hospitals played a key role in local healthcare access, and their instability raised serious concerns about delayed treatments, safety risks, and long-term disruptions in care, especially in underserved communities (Bankrupt Steward Health to Close Two Massachusetts Hospitals | Reuters, n.d.).

6.1.2. Regulatory context

Steward’s challenges drew increasing attention from state authorities, especially in Massachusetts, where several of its hospitals were located. As the company’s financial and operational issues became more visible, state officials investigated Steward’s management and took emergency steps to protect access to care. In January 2025, the Senate Budget Committee released a bipartisan report summarising findings from a federal investigation on PE acquisitions of hospitals and health systems (Senate Budget Committee Digs into Impact of Private Equity Ownership in America’s Hospitals | U.S. Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, n.d.). In the report, national data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services cited in the Senate Committee report showed that Steward hospitals had longer emergency room wait times, higher rates of patients leaving without care, and worse outcomes for common conditions like heart failure.

At present, there are no comprehensive oversight measures or regulations to monitor the involvement of PE firms or real estate investment trusts (REITS) at a national level. However, some states are debating action to hold PE firms accountable. In particular, in response to the Steward saga, in January 2025 Massachusetts Governor signed a new law to expand the regulation of PE investments within the Massachusetts healthcare sector (Bill H.5159, n.d.; Shemano & Lipsky, Reference Shemano and Lipsky2025). The law effectively bans leaseback agreements between hospitals and REITs through the state’s licensing authority, targeting the strategy used by PE firm Cerberus Capital that caused Steward Health Care’s financial woes – a strategy that can saddle acquired facilities with high lease payments and has caused similar hospital and nursing home bankruptcies such as HCR Manor Care’s bankruptcy in 2018 (Bankrupt Prospect Medical Unveils Deals for RI, PA Systems, n.d.; Gov Shapiro Plan Protect PA Health Care Private Equity Wake of Crozer Closure, n.d.; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Howell, Yannelis and Gupta2021; Rucinski & Roumeliotis, Reference Rucinski and Roumeliotis2018).

6.2. United Kingdom: the collapse of four seasons health care under private equity

6.2.1. Acquisition overview

Four Seasons Health Care was once one of the largest care home operators in the UK, running around 340 care homes and 17,500 beds. In 2012, Four Seasons Health Care was bought by Terra Firma Capital Partners, a UK-based PE firm, for £825 million ($1.29 billion) (‘Terra Firma Completes Acquisition of Four Seasons Health Care’, n.d.). After Terra Firma’s takeover, Four Seasons struggled with massive debt, lower government funding, and financial instability. Many of its residents had their care paid for by local government authorities, but as the UK government reduced social care funding (austerity cuts), these payments did not keep up with the rising costs of running care homes. At the same time, Four Seasons was paying very high interest rates on its debt, over 12% per year, making it difficult to remain profitable. By 2015, the company’s credit rating was downgraded, making it harder to borrow additional money, and by 2017–2018, Terra Firma had lost control of the company to its lenders (Jarett, n.d.).

Despite attempts to stabilise the business, Four Seasons collapsed into bankruptcy in April 2019, becoming one of the most significant failures in the UK’s elder care sector. As part of its restructuring process, it attempted to sell around 185 care homes that it owned, while other care homes it rented faced possible closure or takeover by other operators (Jarett, n.d.). The collapse affected 17,000 elderly residents and 22,000 employees (Davies, Reference Davies2019).

Four Seasons Health Care had a complex ownership structure with over 187 linked companies, some registered in offshore locations like Guernsey, making financial oversight difficult (Jarett, n.d.). UK regulators, including the Care Quality Commission (CQC), were responsible for monitoring large care home operators, but they were unable to prevent Four Seasons from collapsing. A report published by the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity outlines how PE investors affected the operations of Four Seasons Health Care, including through reduced staffing, delayed maintenance, and service reductions.

6.2.2. Regulatory context

The collapse of Four Seasons raised broader concerns about whether existing regulations are adequate to curb risky financial practices in elder care. Attempts at reform, including the Care Act 2014 and the Care and Support (Business Failure) Regulations 2015, sought to improve oversight of social care providers (Care Act Factsheets, n.d.). However, these attempts appear to be designed to monitor providers and ensure continuity of care if they collapse, rather than to regulate their financial practices. Moreover, government funding reductions affected the Act’s implementation, forcing local councils to ration care, while staff shortages and minimal reinvestment further weakened the sector, leaving providers vulnerable to financial collapse (Burn et al., Reference Burn, Redgate, Needham and Peckham2024).

In the UK, Four Seasons was not alone in facing financial difficulties – other major care providers, including HC-One, Barchester Healthcare, and Care UK, also underwent sales processes due to financial pressures, rising costs, and high levels of debt. These sell-offs reflect the broader instability within the UK’s elder care sector, where PE-backed firms struggled to balance financial sustainability with quality care.

6.3. Germany: Ufenau capital partners’ acquisition and expansion of corius group

6.3.1. Acquisition overview

Corius Group (formerly DermaClin Deutschland) was acquired by a Swiss PE firm, Ufenau Capital Partners, in 2017 in a leveraged buyout deal valued at around 27 million euros. Following Ufenau’s investment, Corius Group expanded into the largest dermatological and phlebological practice network in Germany, Switzerland, and The Netherlands. The company currently operates 87 locations (52 in Germany, 20 in The Netherlands, and 5 in Switzerland) and employs around 300 doctors (CORIUS – The Future of Dermatology, n.d.).

Beyond Corius, the PE firm, Ufenau Capital Partners, was involved in over 50 add-on healthcare transactions over the past five years. The firm primarily invests across the DACH region (Germany, Austria, Switzerland) and the Benelux region (Belgium, The Netherlands, Luxembourg).

6.3.2. Regulatory context

A key tactic used by PE–led MVZs is its targeted marketing to aging physicians, (The Future of Private-Equity-Led Medical Care Centers | Deloitte Germany, n.d.) leveraging Germany’s capital gains exemption (up to €45,000 for sellers aged 55+), (Steuerberater, n.d.) which incentivises older doctors to sell, further accelerating consolidation. To comply with German regulations, Corius – like other healthcare platform entities – exclusively acquire MVZs or converts private practices into MVZs (In Our CORIUS FAQ You Will Find Answers to Your Questions, 2023). MVZs were originally designed for multispecialty care but now permit single-specialty models, enabling consolidation within specific fields such as dermatology or dentistry. Moreover, PE investment in MVZs – including specialty networks such as Corius – has grown rapidly, with an estimated 750 out of 3,800 MVZs (around 20%) in Germany owned by PE funds as of 2020.

In the dental sector, MVZ ownership is subject to quota and shareholder restrictions: for example, hospitals may own dental MVZs only up to 10 percent (or 5 percent in oversupplied areas, 20 percent in undersupplied ones) of dental service capacity in a planning region, and new dental MVZ expansions are constrained by regional quotas.(Legislative Changes Impacting Private Equity Investment in the German Health and Care Market, 2019) These restrictions were aimed at preventing the large-scale roll-up of dental practices under single ownership. In contrast, dermatology MVZs currently remain governed by the general MVZ framework without equivalent dental-specific quotas or restrictions in Germany, making dermatology an attractive specialty for PE investment (Legislative Changes Impacting Private Equity Investment in the German Health and Care Market, 2019).

6.4. France: Elsan’s acquisition of compagnie stéphanoise de santé (c2s) group

6.4.1. Acquisition overview

In October 2020, Elsan, a private outpatient and inpatient healthcare provider in France underwent a leveraged buyout by a consortium of investors. Elsan has since grown into France’s largest private healthcare provider. The company was formed in 2015 through the merger of Vedici and Vitalia, two major private hospital groups. In 2017, Elsan acquired MédiPôle Partenaires, a large private hospital group, further reinforcing its leadership in private healthcare. In June 2021, Elsan, acquired Groupe C2S from its previous PE-affiliated owner, Eurazeo (Our Group, n.d.). France’s competition authority, the Autorité de la Concurrence, approved the acquisition of C2S by Elsan, determining that it did not create unfair market dominance in key healthcare sectors (The Autorité de La Concurrence Clears the Takeover of C2s Clinics by the Elsan Group, 2021).

As of September 2025, Elsan is affiliated with 212 healthcare centres and 7,500 doctors across France, serving both urban and regional areas. Of these, around 110 (52%) are outpatient clinics and health centres, offering multispecialty services such as surgery, cardiology, oncology, ophthalmology, dermatology, and home hospitalisation.

6.4.2. Regulatory context

At present, France does not impose sector-specific restrictions on PE ownership in healthcare, allowing firms to invest freely in private hospitals and clinics. However, recent policy developments point to growing limits in certain areas – especially medical laboratories, where the government is considering profit caps for large PE backed groups after audits revealed unusually high profits compared with public reimbursement rates (Healy, Reference Healy2025).

Many private healthcare providers rely on state-set tariffs and reimbursement rates, limiting the ability of PE-backed providers to increase the cost of health care services. Instead, PE investments raise concerns that PE-backed providers can prioritise lower-risk or more profitable patients, restricting care access among vulnerable populations.

6.5. Canada: dentalook and the rise of corporate dentistry in Canada

6.5.1. Acquisition overview

Dentalook, a dental service organisation (DSO) in Canada, became the dental platform of Newlook Capital, a Canadian private equity firm, in 2019. Since then, the company has aggressively expanded through a buy-and-build strategy, acquiring multiple clinics across Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta. By November 2024, Dentalook had completed 33 acquisitions, growing its network to over 75 dentists and serving more than 80,000 patients, while maintaining full ownership of its practices (Are Canadian Dental Practices the next Growth Asset?, n.d.).

Dentalook’s rapid expansion reflects the broader growth of the Canadian dental industry, fuelled by technological advancements, increased availability of dental insurance, and strong consumer demand. Two-thirds of Canadians have supplementary private insurance for dental care, making the sector attractive to PE investors (Feldman & Kenney, Reference Feldman and Kenney2024). The introduction of high-margin treatments has enabled general dentists to perform orthodontic procedures traditionally handled by specialists, increasing revenue opportunities for DSOs and PE-backed practices.

The Canadian dental sector is increasingly characterised by larger, multi-dentist clinics. Dentists are increasingly joining DSOs rather than opening independent practices, as the cost of education, equipment, and practice ownership continues to rise. This shift is particularly evident among recent graduates, who are taking longer to establish their own practices than in previous decades (Consolidation of the Canadian Dental Practice Continues – Oral Health Group, n.d.). DSOs like Dentalook offer an alternative to independent practice ownership.

6.5.2. Regulatory context

Dentalook’s rapid expansion under PE ownership reflects the increasing role of PE investment in Canadian dentistry, a sector that falls outside the scope of public insurance coverage. The Canada Health Act prohibits private insurance that duplicates publicly covered services. The existence of complementary private insurance for dental services might make dentistry an attractive target for PE investors. At present, there are no sector-specific restrictions on PE acquisitions of dental practices beyond professional licensing requirements, which can be navigated through the use of DSOs (‘Roll up in Health Care Sector Grows as Private Equity, Strategic Players See Opportunity – Lexpert’, n.d.; ‘The Latest in Canadian Health Clinic Acquisitions’, n.d.).

PE investments in Canadian healthcare nevertheless remain subject to general regulations governing foreign investments. One such example is the Investment Canada Act (Innovation et al., n.d.), under which acquisitions above a certain threshold by non-Canadians are subject to government review to ensure they provide a ‘net benefit to Canada’ and, in some cases, meet national security requirements. Provincial securities laws – such as Ontario’s Securities Act regulate how investors raise funds and manage capital, but do not limit investor participation in healthcare (Investment Funds | OSC, 2026).

As corporate dentistry continues to grow, the role of PE in Canadian healthcare transactions has become a topic of debate (Feldman & Kenney, Reference Feldman and Kenney2024). Some critics argue that Canada should move towards a publicly funded dental care system integrating dental care into Canada’s universal healthcare system, expanding the use of salaried dental professionals, and reviving public dental clinics to reduce reliance on corporate dentistry.

6.6. Spain: private equity in Spain’s fertility sector: KKR’s acquisition of generalife and regulatory implications

6.6.1. Acquisition overview

On November 10, 2021, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR), a US-based PE firm, acquired GeneraLife Clinics through a leveraged buyout, marking the exit of Investindustrial, a London-based PE firm. The deal significantly expanded KKR’s footprint in the European fertility sector, an industry experiencing increasing PE investment due to strong demand for reproductive health services. As of 2023, GeneraLife operates 46 clinics across seven countries, employs over 800 professionals, and performs approximately 30,000 fertility treatments annually (Investindustrial - GeneraLife, 2022).

GeneraLife expanded through acquisitions across Spain, Italy, the Czech Republic, Sweden, and Portugal, consolidating its presence in the European fertility market. Spain has been central to GeneraLife’s strategy, not just due to its high domestic demand, but also because it is a leading hub for cross-border reproductive care, attracting around 50% of international patients in Europe. The country’s favourable regulatory environment, which allows a wider range of assisted reproduction treatments compared to other European nations, has made it a preferred market for expansion. In 2023, the company continued its growth trajectory with the acquisition of Fiv4 (Oviedo, Spain), further strengthening its presence in northern Spain.

6.6.2. Regulatory context

Mergers and acquisitions in Spain’s private healthcare sector are regulated by the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) and are subject to sector-specific licensing and foreign investment controls. Foreign direct investment (FDI) in healthcare falls under Royal Decree 571/2023, which took effect on September 1, 2023, imposing mandatory government approval for non-EU investors acquiring more than 10% of a Spanish company, in strategic sectors such as healthcare (Spains New Foreign Direct Investment Regulations, n.d.). Additionally, under Spanish Competition Law, companies must notify the CNMC before executing a transaction if it results in a market share of 30% (or 50% if the target’s revenue is under 10 million euros) (The CNMC Imposes Gun Jumping Fines for Failure to Notify Transactions Meeting the Spanish Market Share Threshold, n.d.). Failure to comply with these merger notification requirements is classified as a serious violation (Article 62.3 LDC), carrying potential fines of up to 5% of the company’s annual revenue.

In January 2024, the CNMC fined KKR Génesis Bidco S.L. L.U. €1,138,870 for failing to notify its January 2022 acquisition of GeneraLife, a violation known as ‘gun jumping’ (C/1407/23 - KKR / GENERALIFE | CNMC, 2023; KKR | CNMC, 2024). KKR’s failure to comply breached Article 9.1 of the Spanish Competition Act (Ley de Defensa de la Competencia), which mandates prior notification of qualifying transactions. KKR only submitted the required notification in August 2023, following CNMC intervention. The CNMC subsequently approved the acquisition in December 2023 during Phase I of the merger control process and KKR acknowledged the violation and leveraged a 40% fine reduction, ultimately paying 683,322 euros to settle the case (Callol, Reference Callol2024).

6.7. Sweden: acquisition of capio and its changing corporate ownership

6.7.1. Acquisition overview

Capio, a leading pan-European healthcare provider, operates hospitals, specialist clinics, and primary care units across Sweden and other European countries. The provider was acquired in 2006 through a SEK 17 billion (≈ $2.3 billion) leveraged buyout by a consortium of PE firms.

Under PE ownership, Capio focused on scaling primary care, acquiring health centres, diagnostic facilities, and chronic disease treatment centres. The company went public in 2015 through a $280.5 million IPO before being acquired by Ramsay Générale de Santé in 2018 for $904.91 million (SEK 8.19 billion) (Big Capio Shareholders Back $900 Million Ramsay Takeover | Reuters, n.d.). In its corporate-backed phase (2018–2022), the focus shifted towards high-demand specialty outpatient care, particularly ophthalmology, dermatology, orthopaedic surgery, radiology, and rehabilitation services. Capio has established one of Sweden’s largest primary care networks, operating over 100 local health centres (vårdcentraler) and serving an estimated 900,000 registered patients, covering approximately 10% of Sweden’s population (AB, n.d.).

6.7.2. Regulatory context

Capio’s transformation from a PE-backed primary care consolidator to a corporate-backed outpatient provider reflects broader trends in Sweden’s healthcare privatisation and regulation. The 2010 Swedish primary care reform led to a surge in private providers competing for public funding, with PE firms playing a significant role in driving consolidation (Anell, Reference Anell2011). By 2020, approximately 40% of Sweden’s 1,200 primary care centres were privately owned, with one-third controlled by international PE firms (Winblad, Reference Winblad2023).

Swedish healthcare remains publicly funded. Privately operated facilities, including those owned by PE-backed companies, must adhere to national regulations under the Swedish Health and Social Care Inspectorate (IVO) (Healthcare Rules and Regulations, 2019). This ensures standardised patient fees and service requirements across public and private providers. Additionally, transactions surpassing SEK 1 billion ($95 million) in combined revenue, or SEK 200 million ($19 million) per party, are subject to regulatory review by Sweden’s Competition Authority. Foreign healthcare investments also face greater scrutiny. These regulatory measures aim to prevent risk selection, ensuring that private providers, including Capio, do not selectively prioritise lower-risk patients for financial gain.

Despite strict regulations, concerns persist about PE-backed healthcare providers engaging in financial practices that may undermine service quality. Research in Sweden’s private health care sector indicates that PE firms often engage in tax avoidance through offshore tax havens, diverting public funds to service debts, and implementing aggressive cost-cutting measures (Dahlgren, Reference Dahlgren2014; Karlsson & Lilja, n.d.; Winblad, Reference Winblad2023). These strategies have fuelled public and political debates over the role of private capital in Sweden’s universal healthcare system.

6.8. Australia: acquisition of QScan: a case of radiology expansion in Australia

6.8.1. Acquisition overview

Quadrant Private Equity, a Sydney-based PE firm, acquired QScan through a leveraged buyout in May 2017. QScan is a leading diagnostic imaging provider in Australia, operating across 40 locations in multiple states and employing over 150 radiologists (Qscan | Medical Imaging and Radiology Specialists, n.d.). Following the initial PE acquisition, QScan embarked on a roll-up strategy, acquiring several independent radiology providers. In July 2018, QScan acquired Berera Radiology, followed by Universal Medical Imaging in August 2018; the company continued its expansion by acquiring South East Radiology in July 2019 and Alpenglow Australia in October 2019.

Quadrant exited its investment in December 2020, and QScan was acquired by Infratil Limited and HRL Morrison & Co, both New Zealand–based infrastructure investment firms. The transaction valued Qscan at over AUD 700 million, with Infratil acquiring a 56.25% stake for AUD 289.6 million (Completion of Acquisition of Qscan, 2020).

6.8.2. Regulatory context

The rise in PE investments in Australia has attracted growing scrutiny. There is a specific concern that rising PE investments might increase foreign control over Australian healthcare assets, exposing policymakers to potential investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) claims under international trade agreements. These mechanisms allow foreign investors to challenge regulatory changes that might reduce their expected profits, potentially limiting the ability of governments to implement healthcare reforms (Hensher, Reference Hensher2024).

Meanwhile, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has raised alarms over serial acquisitions and consolidation, particularly in pathology and radiology, where PE firms often employ ‘roll-up’ strategies – acquiring multiple smaller providers to gain market dominance (Australia, n.d.). To address consolidation concerns, new merger control laws are expected to take effect in January 2026 and will introduce mandatory reporting for transactions meeting financial thresholds, replacing the previous voluntary notification system in Australia (Commission, 2025). Deals must now be approved by the ACCC if the combined turnover of the buyer and target exceeds AUD 200 million (USD 130 million) or if the buyer alone has an Australian turnover above AUD 500 million (USD 330 million) (Australia’s New Mandatory Merger Regime Is Taking Shape, n.d.).

7. Discussion

The growing role of the financial sector in health care has resulted in policy debates about potential benefits and pitfalls of these trends for patient care, healthcare costs, and health system sustainability. PE in healthcare has been a subject of debate, particularly in the U.S., where studies have shown mixed effects on patient care and rising healthcare costs as a result of PE’s short-term emphasis on profitability. While there is evidence of emerging PE investments in health care in high-income countries, to the best of our knowledge, research has remained largely focused on the US. In this context, we provide the first cross-national evidence of growing PE investments in OECD countries. We offer several key takeaways. First, we find that PE investments in health care have emerged in several high-income countries, ranging from countries with a market-based health system such as the United States; to countries with a National Health Service where tax-funded health care systems predominate and the regulation and provision of health care services is largely determined by the government (E.g., UK and Sweden); to countries characterised by National Health Insurance that rely on private provision of services by for-profit actors (e.g., Australia and Canada), to countries with social insurance models (e.g., Germany and France).

Second, we show that while PE activity is significant and growing across high-income countries, there is wide variation in the sectors that attract PE investments. For example, in the UK, PE firms have steered clear of hospital investments given that 90 percent of hospital care is provided by publicly owned providers for fixed prices. Instead, PE firms have invested in sectors characterised by private provision of health care services and have been attracted to sectors that provide services separate from the NHS, such as elder care. Moreover, PE firms’ propensity to invest in sectors with limited public regulation and financing is apparent in other countries as well. For example, in Canada, PE firms avoid investing in hospitals, which are predominantly publicly owned not-for-profit organisations and or funded by the provincial or territorial government. By contrast, PE investments have targeted Canadian outpatient clinics that provide eye care, imaging, and dental services, similar to the US. Outpatient clinics have also attracted PE investments in several countries including Australia, Germany, Sweden, The Netherlands, to name a few.

Third, we document the prevalence of domestic and foreign PE firms in health care across all evaluated countries. Rising PE ownership of health care facilities inherently results in increasing levels of foreign ownership. Others have argued that PE ownership has the likelihood to expose policy makers to claims from foreign owners and shareholders for reflective losses – potentially lost income and profits linked with policy reforms – under international investor state dispute settlement mechanisms included in many international trade agreements (Hensher, Reference Hensher2024; The Impact of Investment Treaties on Companies, Shareholders and Creditors, 2016).