A vast literature has documented the influence of retrospective evaluations on electoral behavior. Whether measured at the aggregate or individual level, the explanatory power of retrospective voting—particularly economic voting—has been consistently demonstrated across diverse political and social contexts. The logic is straightforward: when the economy performs well, voters tend to reward the incumbent party in the next election; when it performs poorly, they punish it (Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981). Yet during periods of sustained economic growth or in the face of non-economic crises, other factors can become equally powerful determinants of vote choice (Singer Reference Singer2011). This is evident in elections held during wars (Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier Reference Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier2008) or following natural disasters (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017). For some voters, depending on their personal experiences and grievances, non-economic considerations may be particularly salient, leading them to evaluate the incumbent government accordingly (Ley Reference Ley2017).

Elections held during the COVID-19 pandemic present a unique challenge for studying public opinion. In a pandemic, voters are expected to hold incumbents accountable based on their own health and that of their family, friends, and fellow citizens—a task arguably less complex than evaluating the state of the economy (Shino and Smith Reference Shino and Smith2021) or national security during wartime (Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier Reference Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier2008). Yet recent research on economic voting suggests that even in more ordinary contexts, the link between objective conditions and retrospective evaluations often weakens in polarized party systems (Hellwig and Singer Reference Hellwig and Singer2023; Ellis and Ura Reference Ellis and Daniel Ura2021). In other words, retrospective evaluations are not always shaped by economic reality but by whether the president belongs to the voter’s partisan team (Donovan, Key, and Lebo Reference Donovan, Kellstedt, Key and Lebo2022). Do voters also evaluate government performance during a pandemic through a partisan lens? If so, do they discount even the deaths of close relatives and friends—particularly in a context of high mortality—when judging their government based on expressive benefits rooted in partisanship?

The majority of studies in American and Comparative Politics have focused on the electoral consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic—for example, the relationship between retrospective evaluations and vote choice (Guntermann and Lenz Reference Guntermann and Lenz2022; Neundorf and Pardos-Prado Reference Neundorf and Pardos-Prado2022; Mendoza and Sevi Reference Mendoza Aviña and Sevi2021) or the “rally-around-the-flag” effects on presidential approval (Klobovs Reference Klobovs2021; Pignataro Reference Pignataro2021; Sosa-Villagarcía and Hurtado Lozada Reference Sosa-Villagarcía and Hurtado Lozada2021; Hegewald and Schraff Reference Hegewald and Schraff2024). By contrast, this study seeks to understand how retrospective evaluations of government performance during a pandemic are formed. While such evaluations can influence vote choice and presidential approval—and often compete with other salient issues such as the economy, corruption, or insecurity—this study focuses on a more direct and clearly defined outcome: citizens’ evaluations of the government’s performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it examines whether the pandemic’s most consequential effects—such as the death of close relatives, friends, or fellow citizens—are associated with how voters assess the government’s response, particularly in contexts of high COVID-19 mortality. As Morris (Reference Morris2023) argues, a government’s response, or lack thereof, can signal to citizens that the lives of their loved ones are not valued, generating political consequences. This dynamic is likely to be especially pronounced in contexts where governments failed to mitigate the effects of the pandemic.

Mexico offers a valuable case for examining how individual experiences shape evaluations of government performance during a pandemic. The country registered one of the highest COVID-19 mortality in the world—measured both by excess deaths and cumulative deaths (Our World in Data 2021; Msemburi et al., Reference Msemburi, Karlinsky, Knutson, Aleshin-Guendel, Chatterji and Wakefield2023). Despite the severity of the pandemic, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador AMLO engaged in the politics of death by explicitly refusing to monitor the spread of the virus through widespread testing (Martin Reference Martin2022), thereby downplaying the number of confirmed cases and deaths. López Obrador consistently minimized both the severity of the crisis (De la Cerda and Martinez-Gallardo Reference De la Cerda, Martinez-Gallardo, Ringe and Renno2022) and the importance of preventive measures—saying, for instance, that “you have to hug each other, nothing is going to happen” (Rojas Reference Rojas2020) and that he would “put on a mask when there is no corruption [in Mexico]” (Páramo Reference Páramo2020). When AMLO was criticized for not wearing a mask and for continuing to attend political rallies while hugging supporters, Hugo López-Gatell—the Undersecretary of Health and pandemic czar—defended him, declaring that “the President’s strength is moral, not a source of contagion” (Natal Reference Natal, Fernandez and Machado2021).

López Obrador’s government also refused to implement strong policies to mitigate COVID-19, such as restricting air travel, mandating mask use, and enforcing other social distancing measures (Sánchez Talanquer et al., Reference Sánchez Talanquer, Eduardo González Pier, Lucía Abascal Miguel, del Río and Gallalee2021). When the pandemic reached its peak mortality levels, he implicitly attributed the high death rates to the population’s underlying health conditions, as Mexico has one of the highest prevalences of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension in the world (Infobae 2020). Even as hospitals were overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients—forcing many to be turned away and die at home (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2020)—López Obrador continued to insist that no one “was left without a hospital bed, without a ventilator, without a doctor” (Cambaji 2021). A recent independent commission estimated that approximately 300,000 of the 800,000 excess deaths were a direct consequence of the Mexican government’s failed response to the health crisis (Raziel Reference Raziel2024).

Even in this context of exceptionally high mortality rates, this study finds that partisanship—more than the loss of family members or close friends during the pandemic—is the main predictor of voters’ retrospective evaluations of the government’s response to COVID-19. Using data from the 2021 Mexican Election Study (Beltrán et al. Reference Beltrán, Cornejo and Ley2021), the analysis shows that partisans who identify with opposition parties (out-partisans) and report the death of a close friend or relative from COVID-19 are significantly more likely to evaluate the government’s response negatively. In contrast, MORENA partisans, the party of López Obrador (co-partisans), are no more likely to evaluate the government’s response negatively, even when they experience similar losses. For these voters, the death of close relatives or friends has no significant effect on evaluations of the co-partisan government’s performance. This relationship remains robust after controlling for blame attribution, levels of political information, and a range of sociodemographic that could shape how voters form retrospective evaluations.

To test causality, this study employs an original survey experiment and finds that even when respondents are explicitly informed about the scale of the pandemic—e.g. the high number of COVID-19 deaths and the large excess mortality in Mexico—MORENA partisans do not worsen their evaluations of their co-partisan government. These results strongly suggest that MORENA supporters’ reluctance to punish the incumbent is not driven by a lack of information, but rather by partisanship itself. Indeed, when respondents were asked to estimate the number of people who died in Mexico during the pandemic, partisanship again emerged as the strongest predictor—even after controlling for information levels, education, and personal loss due to COVID-19. MORENA partisans significantly underestimated the number of COVID-19 deaths, even after being presented with official mortality figures. By contrast, out-partisans were responsive to the treatment—they lowered their evaluations of the government’s performance—and estimated the national death toll more accurately.

This article’s findings have important implications for the study of public opinion, adding nuance to our understanding of the how voters engage in retrospective evaluation. First, this is not a case in which partisans acknowledge poor performance but tolerate it and continue to support their co-partisan candidate—as most literature has focused (Anduiza et al. Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013; Botero et al. Reference Botero, Cornejo, Gamboa, Pavao and Nickerson2015). Rather, it is a case in which partisans fail to acknowledge poor performance altogether, even in the context of a problematic—and openly negligent—pandemic response, as in Mexico under the AMLO administration (Aruguete et al. Reference Aruguete, Calvo, Cantú, Ley, Scartascini and Ventura2023; Bell-Martin and Díaz Domínguez Reference Bell-Martin and Domínguez2021; Dunn and Laterzo Reference Dunn and Laterzo2021; De la Cerda and Martinez-Gallardo Reference De la Cerda, Martinez-Gallardo, Ringe and Renno2022). Second, previous research often infers democratic accountability from the fact that retrospective evaluations influence vote choice. This study, on the other hand, cautions that such conclusions can be problematic, particularly when the perceived management of a crisis (e.g. voters’ retrospective evaluations) is largely endogenous to partisanship. When retrospective evaluations are filtered through partisan loyalties, voters have fewer incentives to negatively assess the performance of a co-partisan government. As a results, retrospective voting does not always function as a mechanism of democratic accountability when voters rely on partisan retrospection. This holds true not only for traditional performance issues such as the economy, public security, or corruption, but even in the face of a major public health crisis: co-partisans may be willing to overlook the deaths of family members and close friends when judging the performance of their co-partisan government.

At the same time, this article contributes to the study of political behavior in Latin America. While previous research has examined how partisan loyalties shape perceptions of COVID-19 risk in Mexico (Aruguete et al. Reference Aruguete, Calvo, Cantú, Ley, Scartascini and Ventura2023; Bell-Martin and Díaz Domínguez Reference Bell-Martin and Domínguez2021), this article analyzes how retrospective evaluations are formed during major health crises. As recent literature on Latin American democracies emphasizes (Lupu Reference Lupu2015; Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2022), voters increasingly interpret political events through a partisan lens: partisan loyalty—rather than objective conditions—drives individual opinions, even in the context of severe health crises such as COVID-19 in Mexico.

Retrospective Voting, COVID-19, and Elections

The retrospective voting literature argues that voters evaluate government performance by holding incumbents accountable (Key Reference Key1966). According to this perspective, voters retrospectively assess whether incumbents have performed poorly or well by calculating changes in their own welfare (Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981). Most of this research has focused on the logic of economic voting (Anderson Reference Anderson2007). As rational actors, voters tend to support the incumbent party under favorable economic conditions and turn to the opposition when the economy deteriorates. Under certain circumstances, however, voters may shift their attention to non-economic issues (Singer Reference Singer2011; Ley Reference Ley2017). For instance, when elections occur during natural disasters, wars (Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier 2008; Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Mitchell and Welch1995), or corruption scandals (Singer Reference Singer2013), these events can generate new needs, fears, or grievances among the electorate. This dynamic is evident in recent studies of the COVID-19 pandemic: as the salience of the economy declines, public opinion increasingly focuses on health outcomes (Singer Reference Singer2021). Although such crises are often beyond the government’s direct control, public opinion may still evaluate the government’s response and hold incumbents accountable.

In the most recent wave of global elections, findings have been largely mixed. For example, several studies in the United States show that increases in COVID-19 cases negatively affected Donald Trump’s vote share (Baccini, Brodeur, and Weymouth Reference Baccini, Brodeur and Weymouth2021). Specifically, voters who personally knew someone who contracted COVID-19 were less likely to vote for Trump—particularly those who knew someone who had died from the virus (Mendoza Aviña and Sevi Reference Mendoza Aviña and Sevi2021). By contrast, other research finds that Trump received more votes in counties with higher COVID-19 death rates (Algara et al. Reference Algara, Amlani, Collitt, Hale and Kazemian2024). At the same time, attitudes toward President Trump were strongly correlated with how the pandemic affected voters’ own health and the health of their family and friends (Singer Reference Singer2021).

Across Europe, however, several studies document a “rally-around-the-flag” effect: incumbents often benefited from lockdown measures, as visibility of governing authorities boosted their popularity (Giommoni and Loumeau Reference Giommoni and Loumeau2022). Similarly, the growing salience of patriotism and national unity helped incumbent governments benefit from “rally-around-the-flag” effects (Schraff Reference Schraff2021). For example, in England, COVID-related deaths were associated with increased support for the incumbent government (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Pack and Mansillo2021). In Latin America, some presidents also experienced a “rally-around-the-flag” effect (e.g., Peru). However, approval ratings for other presidents did not change significantly and instead followed pre-pandemic trends (e.g. Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, Sosa-Villagarcía and Hurtado Lozada Reference Sosa-Villagarcía and Hurtado Lozada2021).

In the case of Mexico, Table A1 and Figure A1 in the Appendix present retrospective voting models based on data from the 2021 Mexican Election Study (Beltrán et al. Reference Beltrán, Cornejo and Ley2021), conducted shortly after the midterm elections. The logistic regressionsFootnote 1 estimate the probability of voting for MORENA, the incumbent party. Consistent with retrospective voting theory, positive evaluations of the economy and of the government’s response to the pandemic are associated with a higher likelihood of voting for the incumbent. The probability of voting for MORENA increases as respondents’ evaluations shift from negative to positive—rising from 0.45 to 0.62 (+17 percentage points) for the economy and from 0.46 to 0.60 (+14 percentage points) for the pandemic. In line with previous research, however, evaluations of public insecurity and corruption are not significantly associated with support for the president’s party (Altamirano and Ley Reference Altamirano and Ley2020).

Following traditional interpretations of retrospective voting, one might conclude that the Mexican government was held accountable for its perceived management of COVID-19: when the government’s response to the pandemic is evaluated positively, voters support the incumbent party in the subsequent election; when it is evaluated negatively, they punish it. But what if voters’ perceptions of the government’s pandemic response are not grounded in objective information and are instead largely endogenous to partisan attachments? What if voters do not evaluate the incumbent government more negatively even after the deaths of loved ones, family members, and close friends—particularly when the government’s performance during the pandemic was problematic? When retrospective evaluations become detached from factual information—especially during a public health crisis—partisanship can distort the accountability mechanism at the core of retrospective voting. Citizens may ignore objective evidence about executive performance, including high COVID-19 mortality and government negligence, and instead base their evaluations on partisan loyalty. The following sections explore this possibility in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Natural Disasters, Pandemics, and Partisan Retrospection

Most research on the COVID-19 pandemic has focused on its electoral consequences or on the “rally-around-the-flag” effects associated with presidential approval. Yet an important question remains: how does the public form its retrospective evaluations, particularly in a context of high mortality? Traumatic events affect not only those who experience them directly (e.g., natural disasters, mass shootings, or pandemics) but also family members, friends, and others with close personal ties to the victims (Pfefferbaum et al. Reference Pfefferbaum, Gurwitch, Mcdonald, Leftwich, Sconzo, Messenbaugh and Schultz2000; Marsh Reference Marsh2023). Because such events often involve exposure to death or near-death experiences, they can trigger powerful psychological responses—such as fear, anger, and increased distrust—with political implications for turnout (Marsh Reference Marsh2023), political engagement (Soss and Jacobs Reference Soss and Jacobs2009), and electoral behavior. Most theories of voting behavior assume that voters evaluate governmental actions affecting their well-being and reward or punish incumbents accordingly (Key Reference Key1966; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981). During natural disasters, citizens therefore expect governments to respond effectively and take action to mitigate harm (Gerber Reference Gerber2007). When governments fail to do so, voters are expected to evaluate their performance negatively.

Recent literature, however, adopts a more skeptical view. Rather than portraying voters as an “attentive electorate” (Heersink et al. Reference Heersink, Jenkins, Olson and Peterson2020) that systematically incorporates information about political events into their evaluations, Achen and Bartels (Reference Achen and Bartels2017) argue that most voters engage in “blind retrospection,” failing to accurately assess the performance of elected officials. In some cases, voters even punish incumbents for events entirely beyond their control—such as shark attacks in New Jersey (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017)—or focus narrowly on outcomes that occur immediately prior to an election. This pattern of voter behavior ultimately weakens the accountability mechanism that retrospective voting is intended to sustain.

Another challenge is that citizens do not evaluate elected officials solely on the basis of past performance. Instead, they often process information through a partisan lens (Bartels Reference Bartels2002; Zaller Reference Zaller1992)—e.g. partisan retrospection (Heersink et al. Reference Heersink, Jenkins, Olson and Peterson2020)—which makes them less likely to punish a co-partisan government for poor performance. Indeed, there is growing evidence that the link between economic conditions and retrospective evaluations has weakened in polarized party systems such as the United States (Hellwig and Singer Reference Hellwig and Singer2023; Ellis and Ura Reference Ellis and Daniel Ura2021) and the United Kingdom (Bisgaard Reference Bisgaard2015). In these contexts, retrospective evaluations are shaped less by economic reality than by whether the executive belongs to one’s partisan team (Donovan, Key, and Lebo Reference Donovan, Kellstedt, Key and Lebo2022). Do voters also evaluate government performance through a partisan lens during a pandemic? If so, are they willing to overlook the deaths of close relatives or fellow citizens when assessing their government’s performance? Previous research shows that voters often tolerate poor performance and refrain from punishing incumbents during economic downturns (Bartels Reference Bartels2002; Evans and Andersen Reference Evans and Andersen2006) or corruption scandals (Anduiza et al. Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013; Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2022). If this pattern extends to pandemics, voters may tolerate high mortality rates and avoid lowering their evaluations of government performance. Such behavior yields no instrumental benefits but is instead driven by in-group loyalty (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1979).

Recent studies of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States show that opinions about government policy responses varied sharply by partisanship (Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Barry Ryan2021; Shino and Smith Reference Shino and Smith2021) and influenced behaviors such as mask-wearing and social distancing (Gadarian et al. Reference Gadarian, Goodman and Pepinsky2021; Grossman et al. Reference Grossman, Kim, Rexer and Thirumurthy2020). As a result, Republican-leaning counties in the United States experienced significantly higher COVID-19 mortality—an estimated 72.9 additional deaths per 100,000 residents compared to Democratic-leaning counties (Sehgal 2022).

With some exceptions (Byers and Shay Reference Byers and Shay2022), most studies of the pandemic focus on the final link in the accountability process—such as vote choice or presidential approval—while paying less attention to how voters’ retrospective evaluations are formed during a health crisis. If partisan retrospection is widespread during a pandemic, voters have little incentive to punish poor government performance. Partisan bias constrains what would otherwise be a natural tendency toward convergence in political views following shared experiences (Bartels Reference Bartels2002). Although different partisan groups are exposed to similar political and economic conditions, they often evaluate these conditions in systematically different ways due to partisan bias (Bartels Reference Bartels2002; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). In their study, Byers and Shay (Reference Byers and Shay2022) find that knowing someone diagnosed with COVID-19 reduced approval of President Trump’s handling of the pandemic. Although their analysis focuses primarily on whether voters who personally knew someone infected with the coronavirus reported more negative retrospective evaluations, it represents an important advance in understanding how such evaluations are formed. Building on this work, the present article examines whether voters who endured the most severe experiences during the pandemic—such as the death of loved ones, family members, or close friends—evaluate government performance more negatively, particularly in a polarized party system like Mexico.

The main hypothesis of this study focuses on the accountability mechanism underlying voters’ retrospective evaluations. If the Mexican public behaves as an attentive electorate, individuals who experienced the most severe consequences of the pandemic should be especially likely to report negative evaluations of the government’s response. In polarized contexts, however, voters are more likely to rely on partisan retrospection and to form judgments consistent with their partisan loyalties. This tendency is likely to be exacerbated when partisan elites downplay the severity of the coronavirus—as in the cases of Donald Trump in the United States (Mehlhaff et al. Reference Mehlhaff, Tarillo, Vanegas and Hetherington2024), Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil (Bertholini Reference Bertholini2022), and AMLO in Mexico (Dunn and Laterzo Reference Dunn and Laterzo2021)—leading voters to adopt partisan cues when interpreting the pandemic. Consequently, retrospective evaluations of the government’s handling of the pandemic are expected to reflect partisan loyalty more than objective assessments of performance (Heersink et al. Reference Heersink, Jenkins, Olson and Peterson2020), potentially moderating even the effects of direct experience such as the loss of family members or close friends.

H1: Co-partisans of the incumbent government who lost a family member or close friend to COVID-19 are less likely to evaluate the government’s response to the pandemic negatively than out-partisans who experienced similar losses.

The second set of hypotheses examines how voters engage with the politics of death—specifically, whether (1) voters lower their retrospective evaluations of the government’s response to the pandemic when they are explicitly informed about the high mortality rates, and (2) whether voters accurately assess the severity of the pandemic or instead rely on partisan bias. These two aspects are critical because the accountability mechanism underlying retrospective voting assumes that voters are aware both of government actions and of the gravity of the crisis. When provided with such information, voters are expected to form either positive or negative evaluations of government performance. However, it is also possible that some voters do not worsen their assessments of the incumbent government simply because they are unaware of its poor performance. In this case, voters’ retrospective evaluations would be shaped not by partisan bias but by a lack of information. Indeed, studies in American politics show that although the COVID-19 pandemic deeply disrupted people’s lives—and many knew someone who had contracted or died from the virus—many voters still lacked basic knowledge about key aspects of the crisis, such as presidential candidates’ positions on COVID-related policies (Guntermann and Lenz Reference Guntermann and Lenz2022).

For this reason, Hypothesis 2 tests whether voters lower their retrospective evaluations of the incumbent government once they are explicitly informed about high COVID-19 death rates. If voters fail to evaluate the incumbent’s performance more negatively even after receiving such information, it would suggest that partisan bias—rather than a lack of information—drives their perceptions. Another relevant factor in countries with high COVID-19 mortality is voters’ awareness of the actual number of deaths. It is plausible that some voters refrain from evaluating the government’s response negatively because they underestimate the true scale of the pandemic. This dynamic is particularly important in contexts where partisan elites have downplayed the pandemic’s severity, as was the case in Mexico. Accordingly, Hypothesis 3 examines whether government co-partisans engage in motivated reasoning by underestimating the number of COVID-19 deaths, even when presented with official figures. Such behavior would align with the literature on misinformation and fact-checking, which shows that while partisans sometimes update their beliefs when exposed to new information (Wood and Porter Reference Wood and Porter2018), they often fail to revise their views even when confronted with factual evidence (Nyhan, Reifler, and Ubel Reference Nyhan, Reifler and Ubel2013). Building on this discussion, the article’s final set of hypotheses is as follows:

H2: Co-partisans are less likely than out-partisans to evaluate the incumbent government’s performance negatively when informed about high COVID-19 mortality.

H3: Co-partisans are more likely than out-partisans to underestimate the number of COVID-19 deaths, even after being presented with official excess mortality figures.

While this study focuses on the differences between co-partisans and out-partisans, a substantial proportion of voters—particularly in Latin America (Lupu Reference Lupu2015; Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2023)—do not hold partisan attachments. Expectations for independents, however, are less clear. On the one hand, the government’s objective performance should matter more to independents given their lack of partisan ties (Kayser and Wlezien Reference Kayser and Wlezien2011). Because they are not aligned with either incumbent or the opposition, independents can, in principle, evaluate government performance without engaging in motivated reasoning. As Kayser and Wlezien (Reference Kayser and Wlezien2011) argue, independents are true “floating voters,” more responsive to short-term forces such as government performance. On the other hand, independents tend to report lower levels of education, are less engaged in civic life, and express less interest in politics (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964; Lupu Reference Lupu2015), which may reduce their incentives to gather information or to hold governments accountable for poor performance. For these reasons, this study remains agnostic about how independents respond to personal experiences with death and to information about COVID mortality in Mexico.

The next section examines the case of Mexico, where President López Obrador sought to downplay the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic. These efforts likely politicized public perceptions of the crisis, shaping voters’ reactions through their partisan attachments.

The COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico

Mexico is an especially interesting case given its high death toll from the coronavirus pandemic—measured by both excess and cumulative deaths (Our World in Data 2021; Msemburi et al. Reference Msemburi, Karlinsky, Knutson, Aleshin-Guendel, Chatterji and Wakefield2023)—and the elite rhetoric that actively downplayed the virus’s deadliness. Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the presidency in the historic 2018 election, a victory driven by widespread rejection of the country’s major parties and fueled by affective polarization—particularly negative partisanship toward the National Action Party (PAN) and Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which many voters increasingly viewed them as indistinguishable (Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2023). López Obrador framed MORENA’s rise to power as a moral triumph of “the people” over the “corrupt,” “conservative,” and “neoliberal” elites associated with past PAN and PRI governments. During the 2018 campaign, he pledged to fight corruption, prioritize the poor, and advance an “authentic” democracy that embodied “the people” and the “popular will.”

Once in office, López Obrador not only continued his populist rhetoric dividing Mexican society between “the people” and a “corrupt elite,” but also advanced a type of populism that was inclusionary in both symbolic and material terms (Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilar, Cornejo and Monsiváis-Carrillo2025). Consistent with other cases of inclusionary populism (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013), AMLO’s political rhetoric and socioeconomic agenda centered on “the poor.” Although his administration adopted austerity measures that defunded key areas such as public healthcare, education, and science (Sánchez Talanquer Reference Sánchez Talanquer2021), it simultaneously expanded direct cash transfer programs targeting vulnerable groups, including students, single mothers, young professionals, and the elderly. These transfers were frequently framed as personal benefits from the president himself or as part of the “Fourth Transformation.” In addition, AMLO’s administration substantially increased the minimum wage after years of stagnation, making it a central pillar of his economic policy agenda.

At the same time, however, López Obrador governed with an illiberal style (Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2023; Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2023) and consistently weakened mechanisms of democratic accountability (Ibarra del Cueto Reference Ibarra del Cueto2023). He undermined the independence of electoral institutions (Petersen and Somuano Reference Petersen and Somuano2021), attacked key constitutional checks such as the Supreme Court (Ríos Figueroa Reference Ríos Figueroa2022), and expanded the role of the military, blurring the boundaries between civil and military authority (Ley and Aparicio Reference Ley and Aparicio2025). When AMLO took office in 2018, Mexico was classified as an electoral democracy. By the time he left office, it had become an active case of autocratization according to major democracy indices like the V-Dem project (Aguilar et al., Reference Aguilar, Cornejo and Monsiváis-Carrillo2025).

During the pandemic, as Aruguete et al. (Reference Aruguete, Calvo, Cantú, Ley, Scartascini and Ventura2023) argue, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador “illustrates an example of an erratic, negationist response to the pandemic similar to the cases of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Donald Trump in the United States.” The Mexican government’s response was slow, underfunded, lax, and, at best, insufficient (De la Cerda and Martinez-Gallardo Reference De la Cerda, Martinez-Gallardo, Ringe and Renno2022). Measures such as school closures and calls for social distancing were implemented days after other Latin American countries and roughly fifty days after the World Health Organization declared a global health emergency (Sánchez Talanquer et al. Reference Sánchez Talanquer, Eduardo González Pier, Lucía Abascal Miguel, del Río and Gallalee2021). Mexico also provided the lowest level of discretionary fiscal support in Latin America, including income support for those who lost their jobs, targeted transfers, and tax relief (de la Cerda and Martinez-Gallardo Reference De la Cerda, Martinez-Gallardo, Ringe and Renno2022). The scarcity of resources allocated to mitigate COVID-19 was not an anomaly but rather consistent with the government’s broader austerity agenda, often described by Lopez Obrador himself as “Franciscan austerity” (Ibarra del Cueto Reference Ibarra del Cueto2023; Sánchez Talanquer Reference Sánchez Talanquer2021).

Although the pandemic was not as overtly politicized in Mexico as in some other countries—for example, there were no explicit partisan campaigns against vaccines or social distancing—the Mexican public nonetheless received contradictory signals from President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his government (Dunn and Laterzo Reference Dunn and Laterzo2021; Cavalcanti Reference Cavalcanti2021). While the Secretary of Health urged citizens to “stay home” throughout the pandemic, President López Obrador repeatedly downplayed the seriousness of the virus, declaring that “the coronavirus is not even equivalent to influenza” (Párraga Reference Párraga2020) and that “the pandemic fit us like a glove” (nos vino como anillo al dedo, in Spanish) (Martínez Reference Martínez2020). He encouraged Mexicans to “live life as usual,” urging them to continue going to restaurants (El Universal 2020). During one of the pandemic’s peaks in June 2020, AMLO contradicted his government’s own guidance, stating, “We have to overcome not only the pandemic but also our fears, our anxieties […] We all have fears and anxieties, but we do need to go out” (Infobae 2020b). He continued holding political rallies—at times even kissing supporters (González Díaz Reference González Díaz2020)—and publicly claimed he did not need to worry about contracting the virus because he was protected by religious amulets (El Universal 2021).

For most of 2020, the Mexican government projected that a worst-case scenario would result in approximately 60,000 deaths. President López Obrador repeatedly declared that the pandemic was coming to an end—claiming that “we have flattened the curve” (se aplanó la curva, in Spanish) (Infobae 2020)—yet government projections consistently failed to anticipate the crisis’s actual trajectory. When COVID-19 deaths reached the government’s own “catastrophic” projection of 60,000, AMLO implicitly blamed the population’s underlying health conditions. In December 2020, the Mexican government falsified hospital occupancy data to justify keeping commercial activities open during the Christmas season. Only days later, however, authorities were forced to impose a shutdown in Mexico City following a record surge in COVID-19 cases. The health system quickly became overwhelmed—hospitals ran out of beds and medicines, and even a black market for oxygen emerged (Natal Reference Natal, Fernandez and Machado2021).

The AMLO administration also appointed political allies to manage the COVID-19 crisis, which, as De la Cerda and Martinez-Gallardo (Reference De la Cerda, Martinez-Gallardo, Ringe and Renno2022) observe, led to policy decisions that often diverged from scientific consensus. Hugo López-Gatell—the undersecretary of health appointed to lead Mexico’s pandemic response—advocated for herd immunity (Morán Reference Morán2021), claimed that asymptomatic transmission was unlikely (Sánchez Talanquer et al. Reference Sánchez Talanquer, Eduardo González Pier, Lucía Abascal Miguel, del Río and Gallalee2021), and endorsed the use of ivermectin in Mexico City, where the local government led by Claudia Sheinbaum promoted its distribution (Etcetera 2022). López-Gatell also downplayed the effectiveness of face masks, even as late as the summer of 2021 (El Financiero 2021), and minimized the need to vaccinate children (Infobae 2021). The Mexican government did not formally recommend mask usage until very late in the pandemic and did so only cautiously, in part to avoid contradicting President López Obrador, who had repeatedly expressed skepticism about the utility of masks (De la Cerda and Martinez-Gallardo Reference De la Cerda, Martinez-Gallardo, Ringe and Renno2022). The federal government—and López Obrador personally—rejected an independent report estimating that approximately 300,000 of Mexico’s more than 800,000 excess deaths were directly attributable to the government’s failed pandemic response (Raziel Reference Raziel2024). López Obrador dismissed the findings, stating: “This study was done in a way to harm us. It is a vile act of politicking. It’s a filthy pamphlet” (Raziel Reference Raziel2024).

Given partisan elite messaging, the government’s inadequate response, and Mexico’s extraordinarily high COVID-19 mortality, one might expect the public to have rejected the federal government’s handling of the pandemic. Surprisingly, however, President López Obrador’s approval ratings remained largely unaffected by his government’s performance despite the pandemic’s severe consequences. As Figure 1 shows, presidential approval did not decline during the first and second COVID-19 waves preceding the 2021 midterm elections. While López Obrador did not experience a “rally-around-the-flag” effect comparable to those observed in countries such as Canada, Australia, or Germany, his approval ratings remained relatively stable—ranging from 59 to 65 percent between the onset of the pandemic and the midterm elections (Oraculus 2021). Although the midterm election results were not as strong as the government had hoped, they fell far short of a public repudiation of its policies (De la Cerda and Martinez-Gallardo Reference De la Cerda, Martinez-Gallardo, Ringe and Renno2022). MORENA’s coalition maintained its majority in the Chamber of Deputies and captured 15 governorships—many of which had previously been held by the opposition. In 2024, MORENA’s presidential candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum, was elected with approximately 60 percent of the vote—the highest share since Mexico’s democratic transition in 2000.

Figure 1. COVID-19 Cases/Deaths and Presidential Approval in Mexico.

Source: Oraculus’s Presidential Approval Poll Aggregator (Oraculus 2021).

The next section analyzes voters’ retrospective evaluations of the government’s response to the pandemic and how these evaluations may be moderated by partisan attachments. Although Mexico’s party system continues to exhibit higher levels of partisanship than the regional average, the emergence of MORENA has fundamentally reshaped partisan alignments among a significant segment of the electorate. Partisan loyalties remained relatively stable from the country’s democratic transition in 2000 until the 2015 midterm elections, when priistas constituted the largest partisan group. Since 2018, however, morenistas have become the largest partisan group, according to the Mexican Election Study (Beltrán et al. Reference Beltrán, Cornejo and Ley2021). In 2021, 31 percent of respondents identified with MORENA, 9 percent with the PAN, 9 percent with the PRI, 1 percent with the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD)—López Obrador’s former party—and 8 percent with smaller parties. Additionally, 39 percent identified as independents.

In other words, since 2018, MORENA partisanship has rapidly become the most salient partisan identification in Mexico. As in the past—during the PRI’s hegemonic era—partisanship is once again increasingly anchored in a class cleavage. MORENA has consolidated a similar electoral coalition than the PRI’s voter base: less-educated, lower-income, and older voters. However, unlike the PRI, MORENA’s support does not rely disproportionately on rural voters and includes a significant share of higher-income citizens. Moreover, recipients of welfare programs created under the López Obrador administration are especially likely to identify as morenistas, further reinforcing the class-based nature of MORENA’s partisanshipFootnote 2 (Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2025).

Moreover, MORENA partisanship has successfully activated strong in-group loyalty, shaping voters’ attitudes and electoral behavior despite the party’s relatively recent emergence. While MORENA initially inherited much of the PRD’s partisan base and was closely tied to López Obrador’s personal leadership, it has since built a robust party organization and brand, functioning as a strong psychological predisposition. Recent studies find that MORENA partisanship influences retrospective evaluations of the economy (Singer Reference Singer2025), security voting (Ley and Moscoso Reference Ley and Moscoso2025), perceptions of democracy and populism (Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2023), and presidential approval (Beltrán Reference Beltrán2025), among other attitudes. This evidence suggests that MORENA partisanship, as a cue, has strong heuristic value (Brader et al. Reference Brader, Tucker and Duell2013), helping voters form political opinions and ultimately influencing vote choice. Importantly, MORENA partisanship has remained strong even after the AMLO administration, now under the leadership of Claudia Sheinbaum. In 2024, 37 percent of voters identified as morenistas, according to the 2024 Mexican Election Study (Beltrán et al. Reference Beltrán, Castro Cornejo, Altamirano and Singer2024).

Recent studies also show that while MORENA partisanship is still evolving, it is no longer merely a political heuristic that helps voters navigate the political landscape. Instead, it has developed into a social identity—one that has intensified affective polarization (Béjar Reference Béjar2024; Castro Cornejo et al. Reference Castro Cornejo2025). The rise of a populist leader who consistently divides society into Manichean camps—“the people” versus “the corrupt elites”—(Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilar, Cornejo and Monsiváis-Carrillo2025) has reshaped the electorate and generated a new political cleavage. According to the Mexican Election Study (Beltrán et al. Reference Beltrán, Cornejo and Ley2021), the 2021 midterm election recorded the highest levels of affective polarization in Mexico up to that point (see Figure A2 in Appendix)—eventually surpassed only by the 2024 presidential election. This polarization was driven largely by MORENA partisans’ highly negative views of the PRI and PAN. This suggests that polarization in Mexico is rooted less in ideological disagreement than in the expressive benefits derived from partisanship. As a result, electoral competition is no longer only about evaluating the incumbent government; it is also about reinforcing in-group loyalty and out-group animosity.

Observational Data

This research analyzes data from the 2021 Mexican Election Study, which incorporated Module 6 of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) and was designed to examine voting behavior in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The 2021 Mexican Election Study (Beltrán et al. Reference Beltrán, Cornejo and Ley2021), is a nationally representative, face-to-face survey conducted two weeks after the midterm elections. As previously discussed, most studies focus on how voters’ retrospective evaluations of the government’s pandemic response affect vote choice or presidential approval—where the COVID-19 pandemic competes with other salient issues such as the economy, corruption, or insecurity. In contrast, this study focuses on a more straightforward dependent variable: evaluations of government performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. By doing so, the analysis seeks to minimize the influence of other issues on the dependent variable:

Thinking about the performance of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s goverment, in general, how good or bad do you think his government has been over the last year in controlling the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic: a very good job, a good job, a bad job, a very bad job?

The following models are reported across partisan groups, including co-partisans of the MORENA government and out-partisans (e.g., supporters of the PAN, PRI, and minor opposition parties), as each partisan group has different incentives when evaluating the government’s response to the pandemic. To assess whether COVID-19 mortality shapes retrospective evaluations, the key independent variable captures whether respondents reported having a close friend or family member who died from COVID-19. In the 2021 Mexican Election Study, 48 percent of respondents reported that a family member or friend had died from the corona virus.Footnote 3 All questions wordings appear in Table A2 in the Appendix.

The models also include control variables such as presidential approval, López Obrador’s feeling thermometer, left–right ideology, employment status, and several sociodemographic factors (age, gender, and level of education) to ensure that third variables are not driving the results. Similarly, they control for whether respondents contracted COVID-19 or experienced the pandemic’s economic effects—particularly job loss or a significant decline in income—to account for alternative ways through which the crisis migh affect evaluations. By the end of November 2020, more than 13 million people in Mexico had lost their jobs due to the pandemic (3.6 million formal jobs and around 10 million informal ones), affecting approximately 30 percent of households (Natal Reference Natal, Fernandez and Machado2021). The models further control for blame attribution—whether respondents believe Mexico’s high death rate is primarily due to government policy failures or individual responsibility—and for levels of political information, measured using an additive index based on three general questionsFootnote 4 about the Mexican political system.

Finally, because the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic varied across states, the models include dummy variables for states with (1) very high, (2) high, (3) medium, and (4) low mortality rates.Footnote 5 Tables C1, C2, and C3 in Appendix C report alternative operationalizations, including specifications with dummy variables by geographical region and by MORENA’s electoral strength. The models also control for the extent of public policies adopted to contain the pandemic at the state level (e.g., school closures, shutdowns of non-essential businesses, stay-at-home orders, etc.) using the University of Miami COVID-19 Observatory Policy Index. The alternative model specifications do not significantly change the results presented in this section.

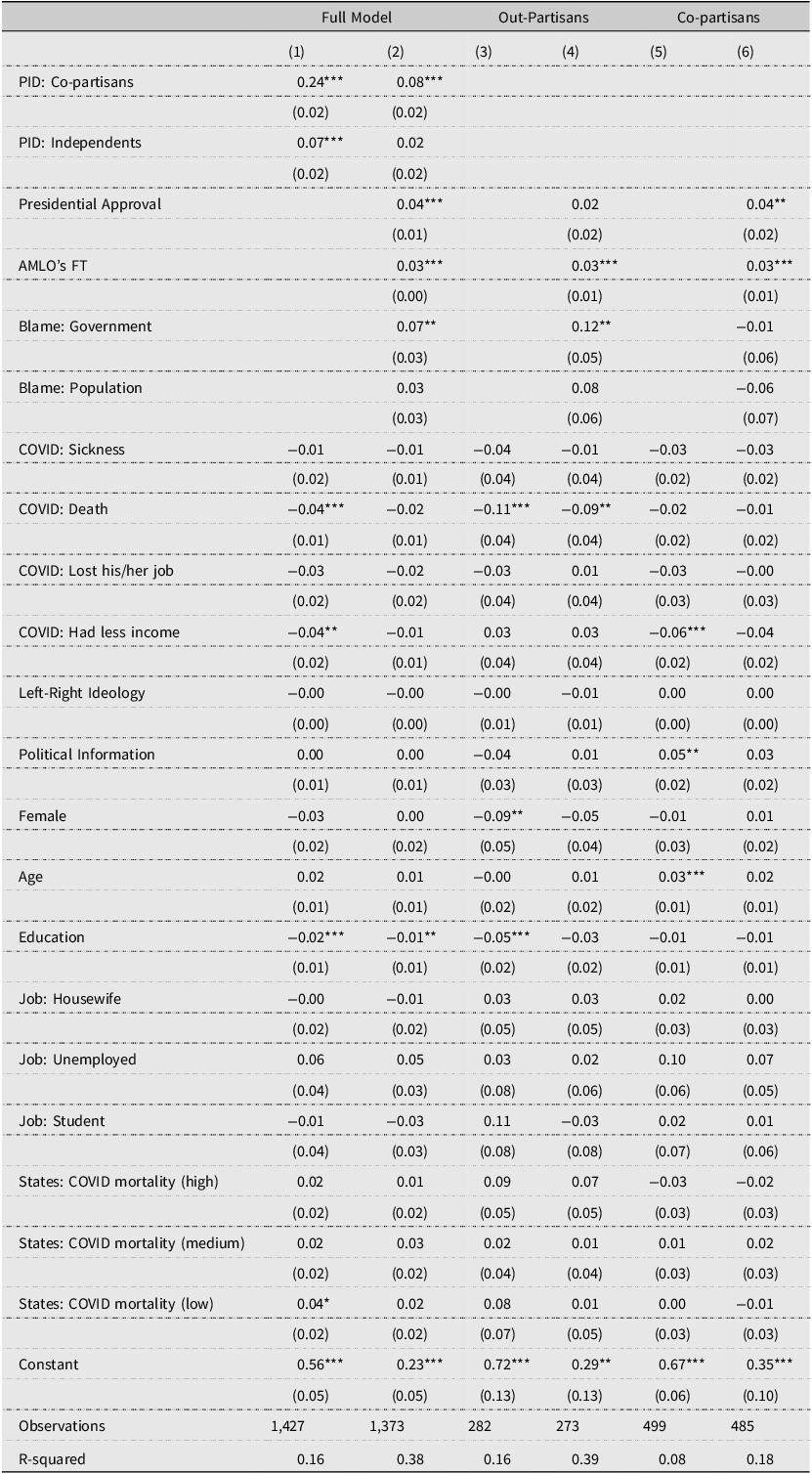

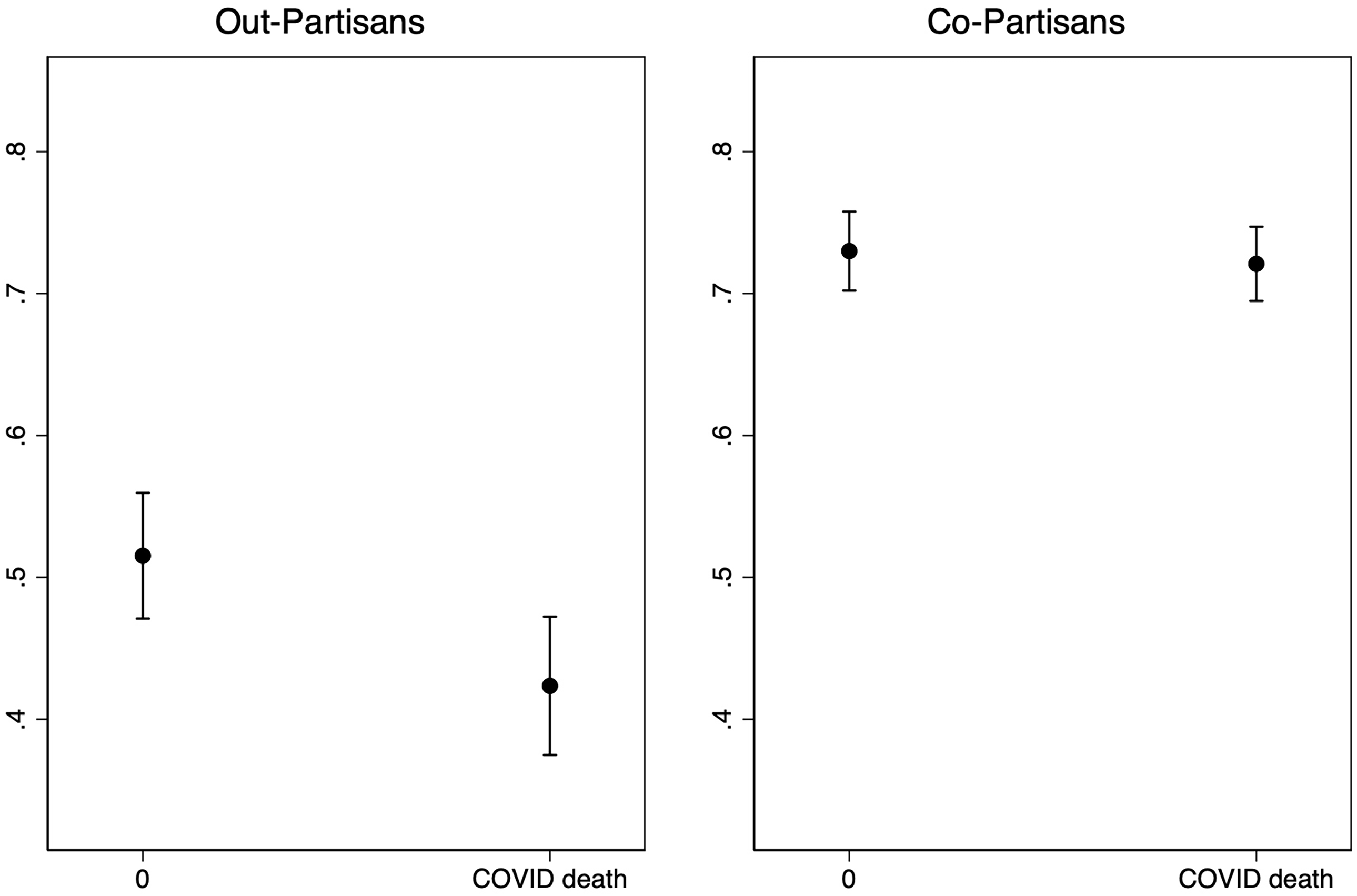

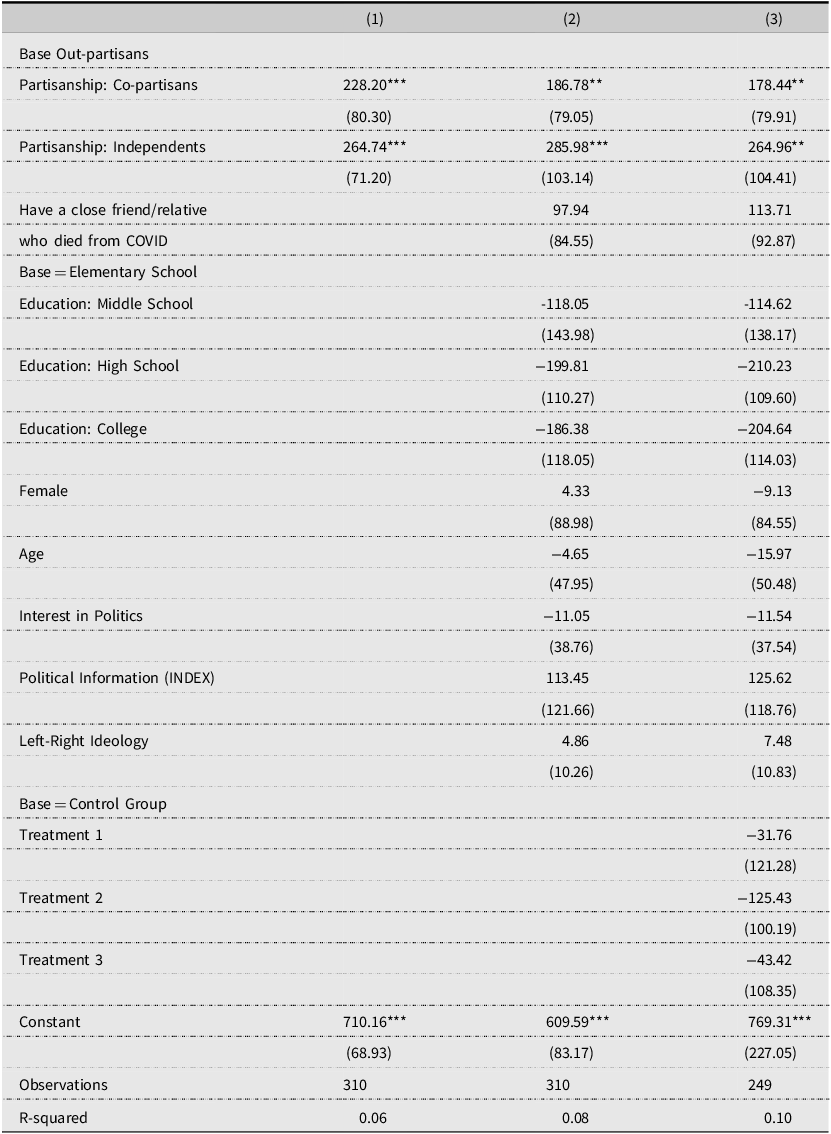

Table 1 illustrates the central role of partisanship in shaping voters’ evaluations of the government’s response to the pandemic. Out-partisans were significantly more likely to evaluate the government’s response negatively when they reported experiencing a COVID-related death among close contacts—a decrease of 11 percentage points (p < 0.05; see Figure 2, Models (4) and (6) in Table 1). This pattern does not hold among co-partisans. MORENA supporters who experienced the death of relatives or close friends do not evaluate the government’s COVID-19 response differently from those who reported no such losses. The models in Table 1 control for AMLO’s feeling thermometer, presidential approval and blame attribution, and also present alternative specifications excluding these controls to ensure that the results are not driven by model specification. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, although co-partisans experienced the same personal consequences as out-partisans, these negative experiences do not translate into more critical evaluations of government performance. Co-partisans and out-partisans thus face different incentives when evaluating the incumbent. Together, these findings suggest that co-partisans’ retrospective evaluations are largely detached from actual government performance.

Table 1. OLS Models. Probability of Reporting a Positive Evaluation of the Incumbent’s COVID-19 Response (Across Partisan Groups)

Reference categories: Out-partisan (Party ID), Center (Region), Employed (Job), Very high mortality (States)

Robust Standard errors in parentheses ***p<0.01, **p<0.05

Figure 2. Probability of Reporting a Positive Evaluation of the Incumbent’s COVID-19 Response.

Table C4 in Appendix C reports the results for independents. Similar to MORENA partisans, independents do not appear to evaluate the government COVID-19 response more negatively when they report the death of a close family member or friend. Unlike MORENA partisans, however, independents report significantly more negative evaluations when they experience job loss during the pandemic (p < 0.05; see Table C4, Model 2). In other words, among independents, there is some evidence of accountability, but it is directed toward the economic rather than the health-related consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. MORENA partisans who lost income during the pandemic appear to lower their evaluations, but this effect is sensitive to model specification and loses statistical significance once political variables are included (Model 6). Table C4 in Appendix C and Figure 3 (see below) further compare independent voters who express a good opinion of MORENA (27 percent of independents rate MORENA between 8 and 10 on a 0–10 feeling thermometer) with MORENA partisans who report similarly positive feelings toward their party (77 percent of MORENA partisans). This comparison strongly suggests that partisan bias makes MORENA identifiers less willing to critically evaluate their co-partisan government. Although both groups express highly favorable views of MORENA—the key difference being that one group identifies as morenista and the other does not—independents penalize the government when they report the death of a close friend or relative due to COVID-19, whereas MORENA partisans do not report more negative evaluations of the government’s response under the same circumstances.

Figure 3. Probability of Reporting a Positive Evaluation of the Incumbent’s COVID-19 Response.

These findings underscore the limits of accountability under conditions of strong partisanship. While out-partisans and, under certain circumstances, independents report more negative evaluations of the incumbent government in response to the health consequences of the pandemic, MORENA partisans remain largely unresponsive—even when personally affected by COVID-19 related deaths. Although these results highlight the central role of partisanship in shaping evaluations of the government’s COVID-19 performance, they cannot establish causality. The following section therefore presents experimental evidence to assess whether partisan bias influences voters’ evaluations of the incumbent government in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Experimental Data

This study fielded an original, nationally representative telephone survey in Mexico in August 2024. The survey was conducted by the polling firm BGC Beltrán and Asocs. and included a sample of 1,000 respondents. To examine the politics of death during the pandemic, the survey incorporated an experiment in which respondents were randomly assigned to one of four groups. Each treatment group was presented with information about the number of deaths caused by COVID-19 in Mexico. While it is neither possible—nor ethical—to manipulate whether respondent’s relatives or friends have died, the experiment provided participants with official government statistics documenting Mexico’s high COVID-19 mortality between 2020 and 2022. Consequently, the experimental design adopts a sociotropic perspective on COVID-19 deaths—focusing on national outcomes—rather than an egotropic one centered on personal experiences, as in the observational analysis presented in the previous section.

The first treatment group was informed about the official COVID-19 death count in Mexico during the pandemic (335,000 deaths). However, due to the lack of widespread COVID-19 testing in Mexico, this official count does not accurately capture the true mortality burden. Indeed, even the Mexican government acknowledged that COVID-related deaths could be up to 70 percent higher than the official figures (de la Cerda and Martinez-Gallardo Reference De la Cerda, Martinez-Gallardo, Ringe and Renno2022). To address this limitation, the second treatment presented respondents with the estimated number of excess deaths that occurred between 2020 and 2022. Specifically, this group was informed of the government’s estimate of 640,000 excess deaths during the pandemic. The third treatment group received the same information as the second group but with additional contextual information—a comparison of Mexico’s excess death rate with that of other countries. By contrast, the control group was not provided with any information about COVID-19 deaths.

-

Now, speaking about the COVID-19 pandemic that occurred between 2020 and 2022 …

-

CONTROL: No information

-

TREATMENT 1: According to federal death records, it is estimated that around 335,000 people died from the coronavirus across the country between 2020 and 2022.

-

TREATMENT 2: According to excess mortality data compiled by the federal government, it is estimated that around 640,000 people died during the pandemic across the country between 2020 and 2022.

-

TREATMENT 3: According to data from the federal government, it is estimated that around 640,000 people died during the pandemic due to excess mortality across the country between 2020 and 2022, making Mexico country with the fifth highest number of deaths in the world.

After reading the information about the COVID-19 deaths in Mexico, respondents were asked the following question, which serves as the first dependent variable in this section:

In your opinion, on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means the federal government did a VERY BAD job and 10 means a VERY GOOD job, how would you rate the federal government’s performance in controlling the consequences of the COVID pandemic? (Remember that you can choose any number between 0 and 10.)

Randomly assignment to treatment conditions ensures that, on average, respondents exposed to different treatments are equivalent in both observable and unobservable characteristics. Any systematic difference in ther dependent variable between the treatment and control groups therefore provides an estimate of respondents’ evaluations of the government after receiving information about the COVID-19 death rate. Overall, Treatment 2 was slightly unbalanced by gender, and Treatment 3 by education level compared to the control group (see Table C5 in Appendix C). Table 2 presents the results of the experiment controlling for education and gender, while Table C6 in Appendix C reports the regression models without control variables. The results are substantively identical across both specifications.

Table 2. OLS Models. Effect of Treatments on Evaluations of the Incumbent’s Response to the Pandemic BASE CATEGORY=CONTROL GROUP

Robust Standard errors in parentheses, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05

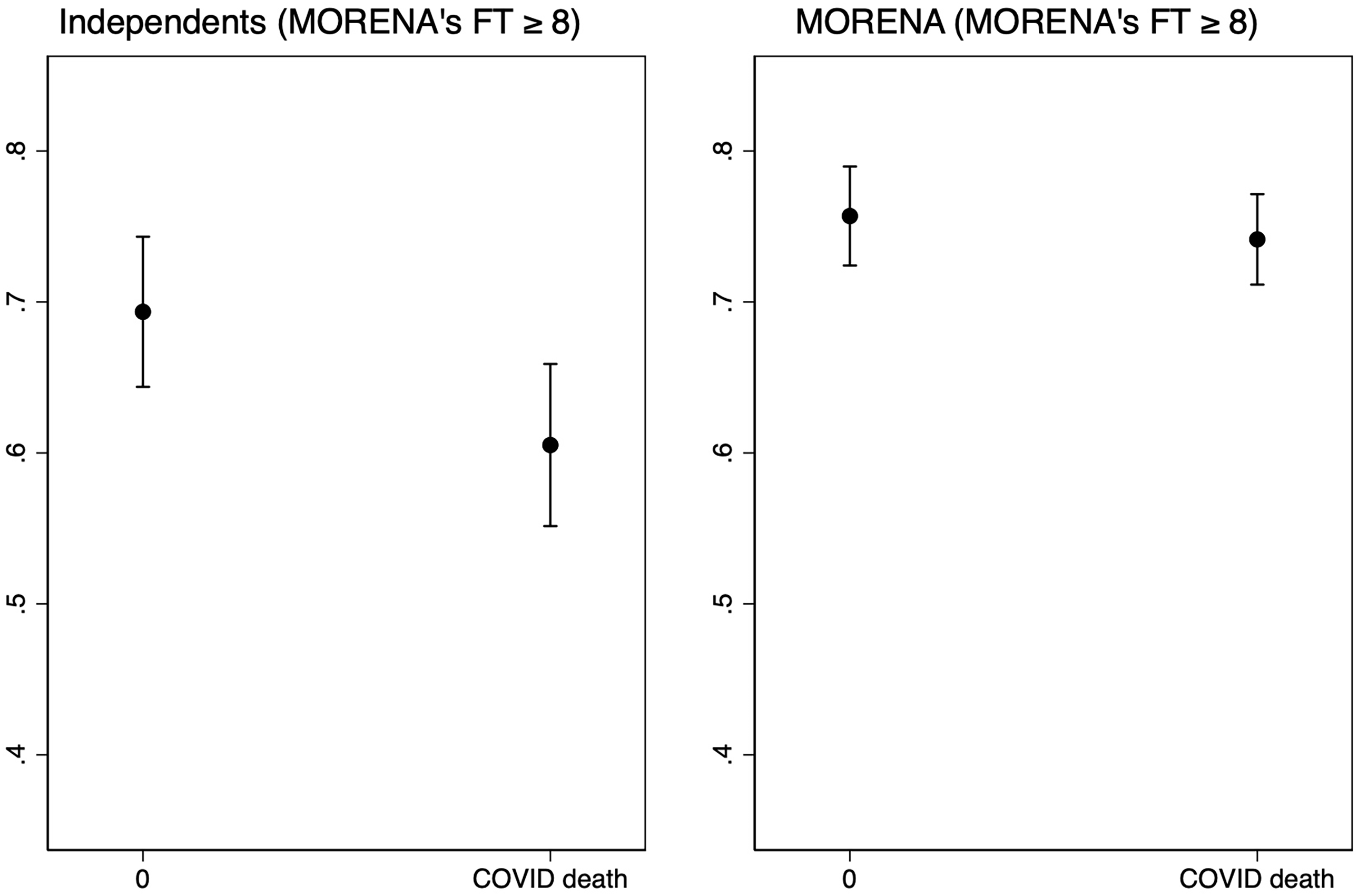

Because responses to each treatment are expected to vary by partisanship, the analysis presents results for the full sample, for out-partisans (voters who identify with the PAN, PRI, or other minor opposition parties), and for co-partisans of the government (MORENA partisans). Table C7 and Figure C1 in Appendix C reports models with interaction terms instead of split samples; the results are substantively identical. The dependent variable in the following models captures respondents’ retrospective evaluations of the government’s performance during the pandemic, measured on a 0–10 scale, where 0 indicates that respondents consider the government’s performance “very bad” and 10 indicates “very good.” Table 2 reveals a pattern consistent with Hypothesis 2. MORENA partisans do not lower their evaluations of the AMLO administration. They continue to report highly positive assessments of their co-partisan government (an average score of 8.2 on the 0–10 scale across the three treatment groups, compared to 8.6 in the control group; see Figure 4), even when presented with information about the high number of COVID-19 deaths (Table 2, p > 0.05).

Figure 4. Evaluations of the Government’s Response to the Pandemic.

Only out-partisans lowered their evaluations when informed about COVID-19 deaths in Mexico. Although they already viewed the government’s pandemic performance somewhat negatively (control mean = 5.5), their evaluations declined further when exposed to information about total deaths (Treatment 1 mean = 3.5, p < 0.01) and excess deaths (Treatment 2 mean = 3.3, p < 0.05). The difference between Treatments 1 and 2 is not statistically significant, suggesting that the effect is driven by the priming of high mortality rather than by the specific figures (335,000 vs. 640,000). Treatment 3, which emphasized that Mexico had the fifth-highest death toll globally, did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p = 0.109).

Overall, these results indicate that co-partisans of the incumbent government are largely immune to information about Mexico’s high COVID-19 mortality. Even when reminded of the country’s severe mortality figures, MORENA partisans remain unwilling to critically evaluate their co-partisan government. In contrast, out-partisans lowered their evaluations when exposed to new mortality information. While Treatments 1 and 2 significantly affected out-partisans’ evaluations, Treatment 3 did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p = 0.109), contrary to Hypothesis 2. Several factors may account for this result. First, the vignette used in Treatment 3 was considerably longer than those in Treatments 1 and 2, potentially reducing respondents’ attention and the treatment’s effectiveness. This aligns with Brutger et al. (Reference Brutger, Kertzer, Renshon, Tingley and Weiss2023), who find that adding contextual detail to experimental vignettes can attenuate treatment effects by making treatment information harder to recall. Second, as often observed in survey research, respondents may focus more heavily on the final portion of questions due to recency effects. If so, the cross-national comparison may have been more salient and less persuasive than the mortality figures themselves. Indeed, the Mexican government frequently dismissed international comparisons, citing the country’s large population and high comorbidity rates. Together, these factors likely recuced responsiveness to Treatment 3.

Figure 4 also presents results for independents. On average, independents evaluated the government’s pandemic response somewhat negatively (control mean = 5.1), but the experimental treatments did not affect their assessments; they did not further lower their evaluations when exposed to information about COVID-19 deaths. Unlike the observational findings in the previous section, where some evidence of accountability emerged among independents, the experiment shows no such pattern. This may reflect weaker incentives to punish the government, as independents do not oppose the MORENA administration to the same extent as out-partisans. Moreover, independents’ generally lower levels of political engagement may further reduce their willingness to hold the government accountable for poor performance.

To better understand why the treatment conditions did not affect MORENA partisans’ responses, Table 3 presents respondents’ perceptions of the severity of the pandemic. In the second part of the survey, respondents were asked to provide a spontaneous estimate of how many people they believed had died from COVID-19 in Mexico during the pandemic:

Based on what you know or have heard, about how many people do you believe died in Mexico during the pandemic between 2020 and 2022 (please mention a number)?

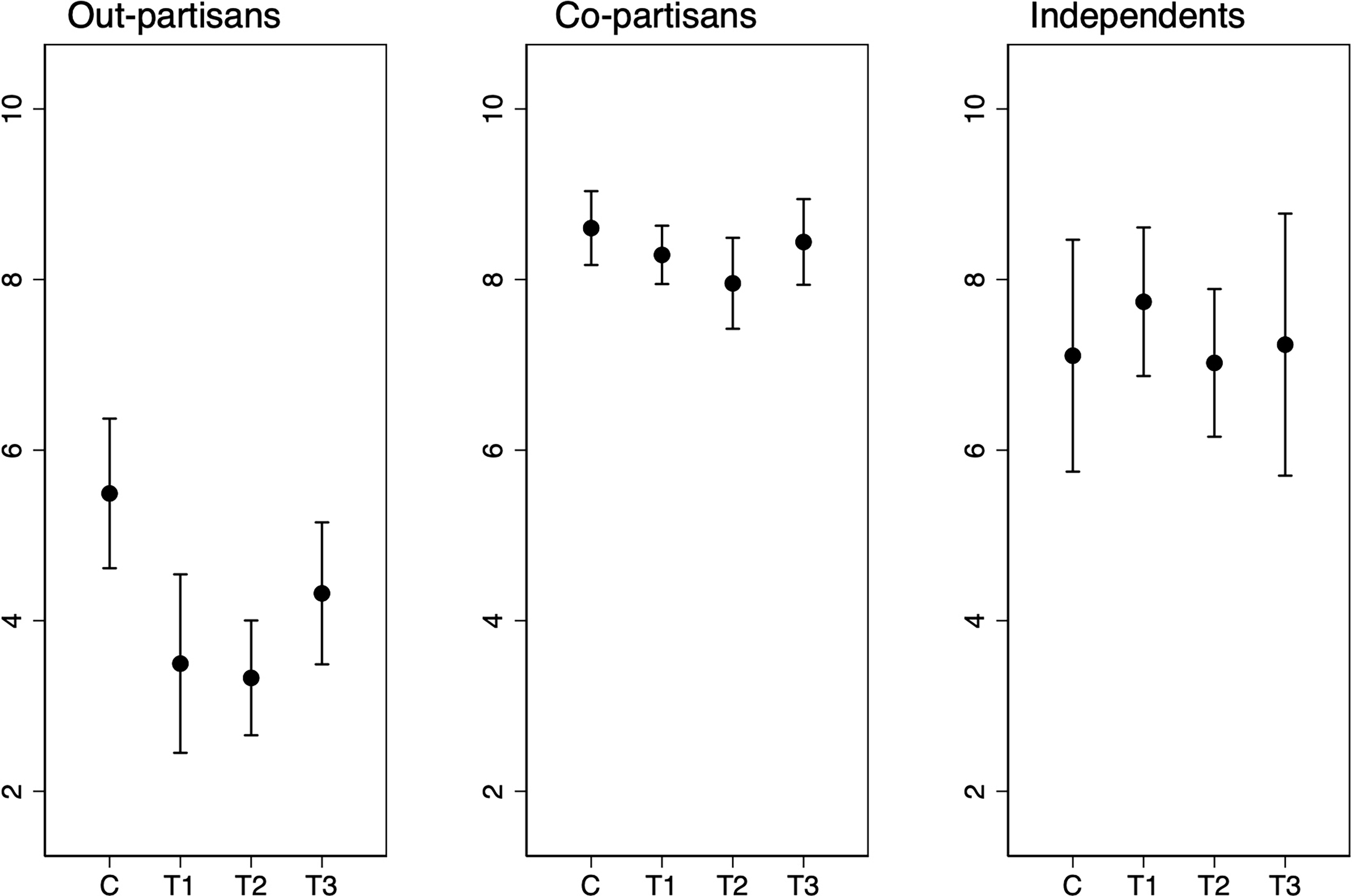

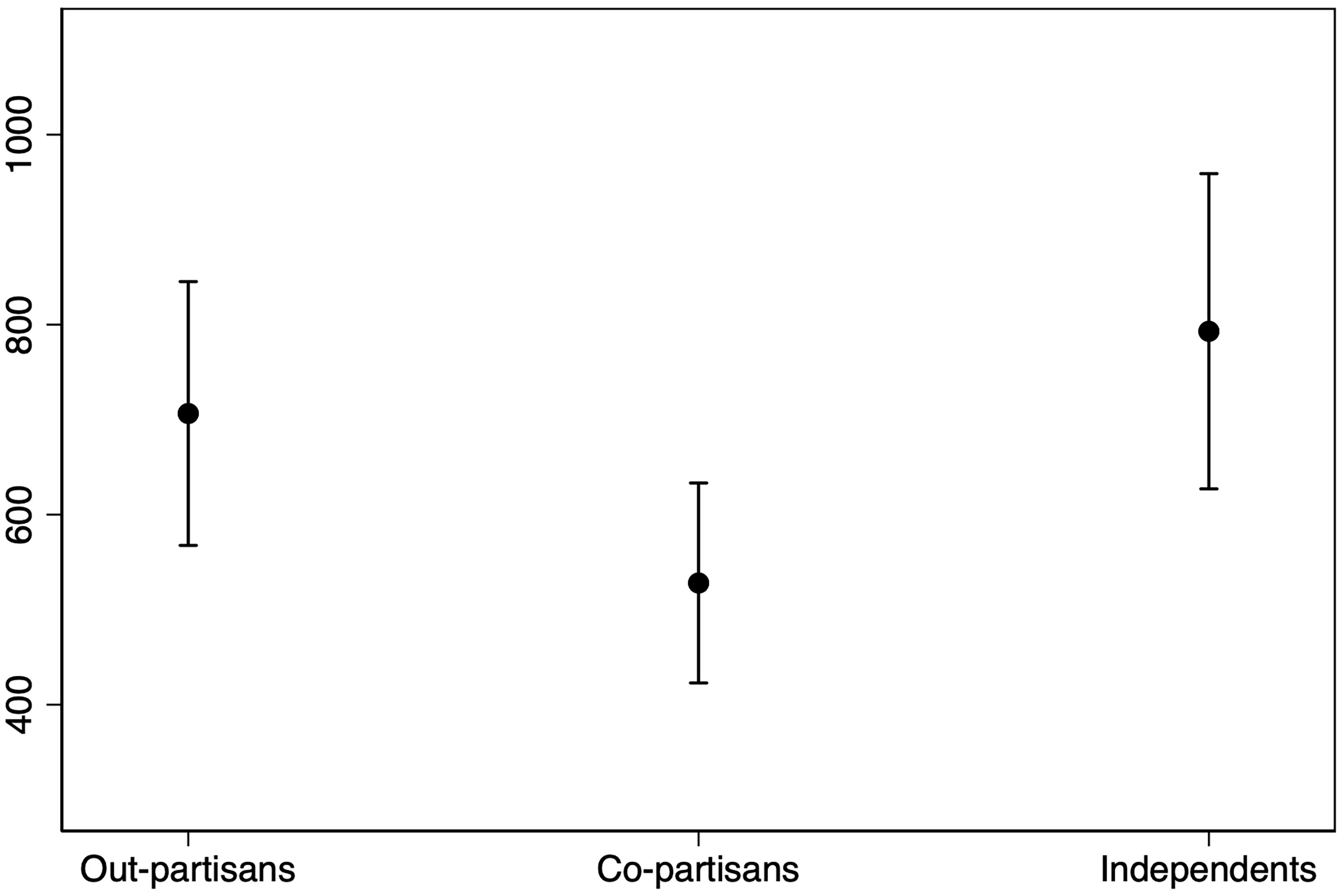

Table 3. OLS models. Total COVID Deaths in Mexico (Respondents’ Estimate) (Unit = Thousands of Deaths)

Robust Standard errors in parentheses, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05

Two important points should be highlighted regarding this question. First, to provide respondents with a baseline, it was asked immediately after a question stating that the official estimate of excess deaths in Mexico was approximately 640,000.Footnote 6 This item was administered to all respondents, regardless of whether they had previously been assigned to Treatment 1, 2, 3, or the control group. Thus, if partisan bias shapes respondents’ estimates of total deaths, it would persist even after exposure to the official excess mortality figure. Second, given the difficulty of the question, a high nonresponse rate is unsurprising: about two-thirds of respondents reported that they “did not know” or preferred not to answer. Nevertheless, the one-third who did respond provide informative insights into perceptions of the pandemic’s mortality. Their estimates ranged from 34 to 3 million deaths, with an average of 649,860—remarkably close to the official figure of 640,000 provided by the survey interviewers. Notably, response rates varied across partisan groups: 54 percent of out-partisans did not answer, compared with 74 percent of government co-partisans. This difference strongly suggests that some MORENA partisans were aware of Mexico’s high mortality rate but chose not to respond, likely reflecting an unwilligness to acknowledge negative outcomes associated with their co-partisan government’s handling of the pandemic.

The key independent variable in the following models is partisanship, separating co-partisans (MORENA identifiers) and out-partisans (supporters of the PAN, PRI, or minor opposition parties) since they are likely to hold different perceptions of the pandemic’s death toll in Mexico. The models also control for whether respondents reported the death of a close friend or relative due to COVID-19,Footnote 7 as well as for sociodemographic variables such as age, education, and gender. Additionally, they control for interest in politics and levels of political information, as more politically engaged respondents may be better prepared to provide accurate estimates. Finally, the models include dummy variables for each experimental treatment condition to which respondents were previously exposed, ensuring that prior exposure to information about COVID-19 deaths does not influence respondents’ subsequent mortality estimates.

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 5, partisanship strongly predicts perceptions of COVID-19 mortality. Co-partisans of the incumbent government significantly underestimate the severity of the pandemic compared to both out-partisans (p < 0.05) and independents (p < 0.05). On average, MORENA partisans estimated 530,000 deaths—about 170,000 fewer than out-partisans (700,000), 260,000 fewer than independents (790,000), and 110,000 fewer than the official excess mortality estimate (640,000) cited at that time of the survey. These effects remain statistically significant after controlling for respondents’ personal experience with COVID-19 related deaths, political interest, levels of political information, education, and prior exposure to the experimental treatments. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, MORENA partisanship functions as a partisan filter, leading co-partisans to dismiss official mortality figures and downplay the pandemic’s toll. Although out-partisans and independents reported higher estimates than the official figure, the difference between their means is not statistically significant. This suggests that out-partisans are not systematically overreporting mortality; rather, their estimates closely resemble those of independents who lack partisan incentives to inflate mortality numbers. Finally, it is important to note that while the survey referred to deaths ocurring between 2020 and 2022, the National Institute of Statistics (INEGI) later reported excess deaths approaching 800,000 following the peak of the pandemic. Although these updated figures received less media attention, some respondents may have been aware of them, which likely explain the higher estimates observed in the data.

Figure 5. Total COVID Deaths in Mexico (Respondents’ Estimate).

Conclusions

As Achen and Bartels (Reference Achen and Bartels2017) argue, retrospection can be a powerful mechanism of democratic accountability, but only if voters are able to discern and set aside irrelevant factors affecting their subjective well-being. This article shows, however, that partisanship plays a central role in shaping voters’ evaluations of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Co-partisans and out-partisans of President López Obrador behave in markedly different ways. Out-partisans who reported the death of a close friend or relative from COVID-19 were significantly more critical of the government’s handling of the pandemic, whereas this association is absent among MORENA partisans. Moreover, experimental evidence shows that even when reminded of the high death toll—including both total and excess mortality—MORENA partisans did not lower their evaluations of the government and continued to underestimate the pandemic’s severity, even when presented with official statistics.

These findings underscore how partisan loyalty can override factual information, thereby limiting the capacity of retrospective voting to function as an effective mechanism of accountability. While much of the existing research on the pandemic has focused on the final stage of the accountability process—where evaluations of the government’s response compete with other salient issues such as the economy, corruption, and public security—this article instead isolates retrospective evaluations of the pandemic itself, minimizing the influence of competing factors. In other words, this is not a case of partisans tolerating poor performance; rather, it is a case of partisans failing to acknowledge poor performance altogether, despite the AMLO administration’s problematic—if not openly negligent—response to the pandemic.

This study contributes to the literature on public opinion and democratic accountability by showing that retrospective evaluations in Mexico are largely endogenous to partisanship. Although there is a strong association between voters’ perceptions of the government’s pandemic response and their vote choice in the midterm elections (Table A1 and Figure A1 in the Appendix), this association does not necessarily constitute evidence of democratic accountability. MORENA partisans engage in partisan retrospection, discounting negative information about the pandemic when forming their evaluations of government performance. These results are consistent with with findings in the economic voting literature, which increasingly demonstrate that retrospective evaluations in polarized party systems often diverge from objective indicators of performance and are instead shaped by partisan or affective commitments (Hellwig and Singer Reference Hellwig and Singer2023). This dynamic highlights a central challenge for democratic governance: when partisan loyalties override factual information, elections may reward or punish governments for reasons unrelated to their actual performance.

While the presence of a populist leader who explicitly politicized the pandemic makes Mexico a particularly likely case for partisan rationalization, the mechanisms identified here are not unique to this context. They likely extend to other countries in Latin America and beyond—especially where partisan elites politicize events and voters rely heavily on partisan cues to interpret political events. Thus, these findings have broader implications that extend beyond the pandemic, applying to evaluations of economic management, anti-corruption efforts, public insecurity, and violence. In affectively polarized party systems with moderate to high levels of partisanship (e.g., Brazil, Uruguay) or strong political identities (e.g., Moralismo in Bolivia, Uribismo in Colombia, Mileísmo in Argentina) (de la Cerda Reference De la Cerda2025), similar processes of partisan retrospection and resistance to factual information may likewise undermine electoral accountability. The Mexican case, therefore, serves as an illustrative example of how polarization and populist rhetoric can weaken the link between government performance and voter evaluation, revealing broader dynamics that characterize many contemporary democracies.

An interesting pattern—or lack thereof—emerges among independents. In theory, because they are not aligned with either the incumbent or opposition parties, independents should be less prone to partisan rationalization and better able to evaluate government performance objectively (Kayser and Wlezien Reference Kayser and Wlezien2011). In the observational analysis, independents who experienced income losses during the pandemic rated the government more negatively, consistent with performance-based accountability. Yet, in the experiment, information about total COVID-19 deaths had no significant effect on their evaluations. One explanation is that independents respond more strongly to personal (egotropic) losses than to sociotropic information about national mortality. Another possibility is that independents constitute a more heterogeneous group than partisans. For example, independents with highly favorable views of MORENA were more likely to evaluate the government negatively when reporting the death of a close friend or relative, but this pattern disappears when the full group of independents is considered. Future research should examine the conditions under which independents are more likely to punish poor government performance—particularly given their lower levels of political engagement and information levels relative to partisans.

Although this article focuses on partisan biases in retrospective evaluations, future research should also investigate the nature and origins of these biases. Specifically, future studies should assess whether policy-driven attachments (e.g., AMLO’s pro-redistribution programs) amplify or mitigate voters’ biases when evaluating government performance, or whether such biases are themselves primarily the product of partisan loyalties. Furthermore, while partisanship emerges as the strongest predictor of retrospective evaluations in the observational analysis—outperforming ideology and blame attribution—it is possible that, in the survey experiment, MORENA partisans dismissed the country’s high death rate for reasons beyond partisanship, such as minimizing the government’s perceived responsibility. While Mexico’s pandemic response was highly centralized at the federal level—particularly in comparison to other countries—and accompanied by explicit elite cues from the president that consistently downplayed the severity of COVID-19, many co-partisans may nontheless believe the government implemented the best possible strategy. As a results, they may resist negative reassessments of government performance even when presented with factual information. Future research should therefore examine more closely the conditions under which partisans are willing—or unwilling—to hold their co-partisan governments accountable.

Finally, it is important to note that both surveys analyzed in this study were conducted a few weeks after election day—a period in which partisanship is highly activated by political campaigns. Although surveys conducted immediately after elections may overestimate partisan bias, this is also the moment when democratic accountability should matter most, as voters assess incumbent performance when deciding whether to reward or punish the governing party. Nevertheless, future studies should examine public evaluations of government performance during non-electoral periods, when partisan activation is weaker, to asses whether the patterns identified here persist outside the electoral context.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2025.10044

Acknowledgments

I thank Ulises Beltrán and Sandra Ley for their important contributions to this project as part of the 2021 Mexican Election Study. I also thank participants of the Política y Gobierno Workshop at CIDE and the Political Science Research Workshop at the University of Massachusetts Lowell for their valuable feedback, particularly Matthew Singer, Joshua Dyck, Angélica Durán-Martínez, Ardeth Thawnghmung, Deina Abdelkader, and Minnie Minhyung Joo. All mistakes remain my responsibility. University of Massachusetts-Lowell IRB: 24-109-COR-EXM.

Competing interests

The author declares none.