Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa is naturally endowed with many inland valleys, covering 85 million hectares (Rodenburg et al. Reference Rodenburg, Zwart, Kiepe, Narteh, Dogbe and Wopereis2014). While the uplands of inland valleys generally consist of good-quality agricultural soils, the valley fringes and bottoms have higher moisture availability, higher soil fertility, and higher crop and water productivity and are therefore considered to have an immense potential for crop production, notably rice-based systems (Giertz et al. Reference Giertz, Steup and Schönbrodt2012; Rodenburg et al. Reference Rodenburg, Zwart, Kiepe, Narteh, Dogbe and Wopereis2014). Rice is in high demand as a food crop in West Africa due to the increasing population and shifts in consumer preferences (Arouna et al. Reference Arouna, Soullier, del Villar and Demont2020).

Still, rice production within the West Africa region covers only 60 percent of consumption (Saito et al. Reference Saito, Vandamme, Johnson, Tanaka, Senthilkumar, Dieng, Akakpo, Gbaguidi, Segda, Bassoro, Lamare, Gbakatchetche, Abera, Jaiteh, Bam, Dogbe, Sékou, Rabeson, Kamissoko, Mossi, Tarfa, Bakare, Kalisa, Baggie, Kajiru, Ablede, Ayeva, Nanfumba and Wopereis2019). Moreover, inland valleys are highly underutilized for agriculture and rice production in West Africa, as only 10–15% of the inland valley area is used for agriculture (Balasubramanian et al. Reference Balasubramanian, Sie, Hijmans and Otsuka2007; Rodenburg et al. Reference Rodenburg, Zwart, Kiepe, Narteh, Dogbe and Wopereis2014) and less than 5% of suitable inland valleys are used for rice production (Danvi et al. Reference Danvi, Jütten, Giertz, Zwart and Diekkrüger2016). One of the reasons why inland valleys are underutilized for agriculture and rice production is excess water in parts of the inland valleys due to poor water control facilities, such as drainage systems and bunds (Rodenburg et al. Reference Rodenburg, Zwart, Kiepe, Narteh, Dogbe and Wopereis2014).

In addition, farming in inland valleys poses health risks (Rodenburg et al. Reference Rodenburg, Zwart, Kiepe, Narteh, Dogbe and Wopereis2014; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Tusting, Bottomley, Saito, Djouaka and Lines2022). It can increase exposure to water-borne diseases, river blindness, sleeping sickness, and malaria, particularly in early-stage rice fields where vector densities are six times higher than in non-rice fields (Assi et al. Reference Assi, Henry, Rogier, Dossou-Yovo, Audibert, Mathonnat, Teuscher and Carnevale2013; Rose et al. Reference Rose, Ali, Bakhsh, Ashfaq and Hassan2020; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Tusting, Bottomley, Saito, Djouaka and Lines2022). These health risks may discourage well-off farmers from engaging in inland valley farming and rice production practices in the inland valleys. However, little is known about the socio-economic factors and constraints that shape farmers’ adoption of inland valley farming and rice production.

This paper, therefore, has two objectives. First, it analyses the determinants of farmers’ decisions to practice agriculture in the highly productive fringes and bottoms of inland valleys.Footnote 1 Farmers that live in inland valleys typically live and farm crops and livestock in the uplands. The second objective is to analyze the barriers and drivers of the decision to grow rice in an inland valley conditional on the adoption of inland valley farming. We collected household-level survey data from 16 inland valleys in Côte d’Ivoire and 16 in Ghana. Both countries import a large share of their rice consumption and have designated inland valley farming as a vehicle for increased food security and reduced poverty (Demont Reference Demont2013). We applied a bivariate probit model to a sample of 742 randomly selected farmers (369 from Côte d’Ivoire and 373 from Ghana).

Most of the existing literature on the use of inland valleys for agriculture in West Africa analyses biophysical determinants that influence agricultural productivity, such as climate, soil types, soil fertility, rainfall, and slopes (e.g., Windmeijer and Andriesse Reference Windmeijer and Andriesse1993; Djagba et al. Reference Djagba, Sintondji, Kouyate, Baggie, Agbahungba, Hamadoun and Zwart2018; Hector et al. Reference Hector, Cohard, Seguis, Galle and Peugeot2018; Djagba et al. Reference Djagba, Zwart, Houssou, Tente and Kiepe2019; Dossou-Yovo et al. Reference Dossou-Yovo, Zwart, Kouyate, Ouedraogo and Bakare2019; Akpoti et al. Reference Akpoti, Dossou-Yovo, Zwart and Kiepe2021; Sawadogo et al. Reference Sawadogo, Dossou-Yovo, Kouadio, Zwart, Traoré and Gündoğdu2023). The few studies that include socio-economic characteristics in their analyses focus on differences between inland valleys, rather than differences between farmers, and include a very limited number of socio-economic factors (Erenstein Reference Erenstein2006, Giertz et al. Reference Giertz, Steup and Schönbrodt2012, Dossou-Yovo et al. Reference Dossou-Yovo, Baggie, Djagba and Zwart2017, Djagba et al. Reference Djagba, Sintondji, Kouyate, Baggie, Agbahungba, Hamadoun and Zwart2018). Erenstein (Reference Erenstein2006) studied intensification and extensification in wetlands in Côte d’Ivoire and Mali. The author used a one-page questionnaire to collect information of limited depth from one or more key informants in 472 lowland user groups. Dossou-Yovo et al. (Reference Dossou-Yovo, Baggie, Djagba and Zwart2017) develop a classification of inland valleys based on land use, biophysical and socio-economic data from 257 inland valleys. In each inland valley, socio-economic data were collected by means of a group meeting with 5 to 20 farmers. Djagba et al. (Reference Djagba, Sintondji, Kouyate, Baggie, Agbahungba, Hamadoun and Zwart2018) assessed the parameters that indicate high potential for the development of rice-based systems in 499 inland valleys in Benin, Mali, and Sierra Leone. An important common finding in these studies is that distance to the nearest market is an important factor in inland valley development. Hence, we include walking distance from home to the nearest market as one of the explanatory variables in our analysis.

Our contribution to the existing literature is in three major directions. First, we present the first comprehensive study of socio-economic characteristics of farmers in inland valleys. We use household-level data to analyze the factors that determine whether smallholder farmers adopt inland valley farming and rice production. A better understanding of inland valley farming and rice production can help farmers’ food security to reduce poverty levels in West Africa (Seck et al. Reference Seck, Touré, Coulibaly, Diagne and Wopereis2013; Tanaka et al. Reference Tanaka, Johnson, Senthilkumar, Akakpo, Segda, Yameogo, Bassoro, Lamare, Allarangaye, Gbakatchetche, Bayuh, Jaiteh, Bam, Dogbe, Sékou, Rabeson, Rakotoarisoa, Kamissoko, Mossi, Bakare, Mabone, Gasore, Baggie, Kajiru, Mghase, Ablede, Nanfumba and Saito2017). We use household-level survey data from four regions in two countries with rich information on socio-economic, farm and institutional characteristics. This allows us to extend the existing literature with an in-depth analysis of the determinants of inland valley farming and rice production. Furthermore, existing studies on the socio-economic determinants of the adoption of rice production were based on group interviews or small sample sizes per inland valley, which may lead to insufficient representation of various types of farm households in the data. Second, we empirically examine the determinants of farmers’ adoption of inland valley farming and, among adopters of inland valley farming, their decision to grow rice using probit models. Third, we focus on indicators for having access to capital. In particular, we provide new evidence on the role of owning perennial tree crops in agricultural production decisions.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section “Conceptual framework and estimation method” provides an overview of the conceptual framework, estimation strategy, and econometric model specifications. Section “Study area, data, and description of variables” presents the material and methods, including the study area, sampling procedure, survey design and hypothesized relationships of variables. Sections “Results” and “Discussion” present the results and discussion part. The final part presents the conclusions and policy implications.

Conceptual framework and estimation method

Conceptual and empirical framework

Smallholder farmers in West Africa typically produce both for the market and for own consumption. Farmers face constraints in input and credit markets due to a lack of employment opportunities in rural areas, high transaction costs and asymmetric information. Under such conditions, farm household decisions regarding labor supply and technology adoption are determined simultaneously and are best described by a conceptual model in which consumption and production decisions are non-separable (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Squire and Strauss1986; Janvry et al. Reference Janvry, Fafchamps and Sadoulet1991). Such a conceptual model should also account for differences in farmers’ endowments of physical, natural, financial, social, and human resources as well as in their preferences regarding production and consumption decisions.

Following Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Squire and Strauss1986), we assume that farmers maximize their utility subject to budget constraints. In addition, we assume that farmers are constrained by their endowments of physical, natural, financial, social and human resources. Farmers will adopt inland valley farming and rice production if this gives them higher utility than alternative options. The observed outcome of adoption decisions can be analyzed using a random utility model. According to random utility theory, farmer i will adopt technology j if the utility of adoption

![]() $U_{ij}^{\rm{*}}$

is greater than the utility from non-adoption. However, since the utility is unobservable, it can be expressed as a function of observable elements in the following latent variable model and related to household, farm, institutional, environmental and location variables:

$U_{ij}^{\rm{*}}$

is greater than the utility from non-adoption. However, since the utility is unobservable, it can be expressed as a function of observable elements in the following latent variable model and related to household, farm, institutional, environmental and location variables:

where

![]() $U_{ij}^{\rm{*}}$

is a dichotomous dummy variable that equals 1 if farmer i adopts and 0 otherwise; β is a vector of parameters to be estimated; xij is a vector of explanatory variables, and ϵij is normally distributed error term. In this paper, an adopter of inland valley farming is a farm household that (self-reportedly) involved in farming in the inland valleys in the previous 12 months. An adopter of rice production is a farm household that (self-reportedly) involved in rice farming in the inland valleys in the previous 12 months, only for those who are involved in inland valley farming.

$U_{ij}^{\rm{*}}$

is a dichotomous dummy variable that equals 1 if farmer i adopts and 0 otherwise; β is a vector of parameters to be estimated; xij is a vector of explanatory variables, and ϵij is normally distributed error term. In this paper, an adopter of inland valley farming is a farm household that (self-reportedly) involved in farming in the inland valleys in the previous 12 months. An adopter of rice production is a farm household that (self-reportedly) involved in rice farming in the inland valleys in the previous 12 months, only for those who are involved in inland valley farming.

Estimation strategy

In this study, we model farmers’ adoption decisions using two separate probit models. In the first probit model, we estimate the probability that a farmer adopts inland valley farming given the explanatory variables for the full sample and the model is specified as (Greene Reference Greene2008):

where

![]() ${{y}}_{{{1i}}}^{{*}}$

is a latent variable representing the probability to adopt inland valley farming. If

${{y}}_{{{1i}}}^{{*}}$

is a latent variable representing the probability to adopt inland valley farming. If

![]() ${{y}}_{{{1i}}}^{{*}}$

> 0, farmers adopt inland valley farming; otherwise, they do not adopt inland valley farming. x1i is a vector of explanatory variables;

${{y}}_{{{1i}}}^{{*}}$

> 0, farmers adopt inland valley farming; otherwise, they do not adopt inland valley farming. x1i is a vector of explanatory variables;

![]() $\beta^\prime$

presents vectors of estimable model parameters; and ϵ1i is a random error term assumed standard normal.

$\beta^\prime$

presents vectors of estimable model parameters; and ϵ1i is a random error term assumed standard normal.

In the second probit model, we estimate the probability of a farmer to grow rice for those farmers who responded ‘yes’ to the first question, given the explanatory variables:

where

![]() $\;y_{2i\;}^*$

represents the latent variable (unobserved). If

$\;y_{2i\;}^*$

represents the latent variable (unobserved). If

![]() $\;y_{2i\;}^*$

> 0, farmers choose rice crops; otherwise, they choose non-rice crops. x2i is a vector of explanatory variables;

$\;y_{2i\;}^*$

> 0, farmers choose rice crops; otherwise, they choose non-rice crops. x2i is a vector of explanatory variables;

![]() $\gamma \,^\prime$

presents vectors of estimable model parameters; and

$\gamma \,^\prime$

presents vectors of estimable model parameters; and

![]() $\;{\varepsilon _{2i}}\;$

is the residual associated with the model, also assumed standard normal. Both probit models are estimated by maximum likelihood (Greene Reference Greene2008). To account for potential correlation of unobserved factors within inland valleys, we compute cluster-robust standard errors. We estimate equations (1) and (2) using Stata 16.0 (StataCorp Reference StataCorp2019).Footnote 2

$\;{\varepsilon _{2i}}\;$

is the residual associated with the model, also assumed standard normal. Both probit models are estimated by maximum likelihood (Greene Reference Greene2008). To account for potential correlation of unobserved factors within inland valleys, we compute cluster-robust standard errors. We estimate equations (1) and (2) using Stata 16.0 (StataCorp Reference StataCorp2019).Footnote 2

Study area, data, and description of variables

Study area

This study was part of a larger research project coordinated by AfricaRice, a CGIAR Research Center, to investigate food and nutrition security among smallholder farmers in West Africa. Data were collected in two regions in Côte d’Ivoire (Bouake and Gagnoa) and two regions in Ghana (Ahafo Ano North and Ahafo Ano South).Footnote 3 Figure 1 presents a map of the study areas.

Figure 1. Map of the study area.

The selected inland valleys are located in or near the studied villages (i.e., within walking distance or accessible by (motor)bike. According to village chiefs and cooperatives, the number of household heads in the sampled inland valleys ranges from 32 to 153. In Ghana, approximately 80% of land is held under customary tenure and land use rights are assigned to individual households (Abdulai et al. Reference Abdulai, Owusu and Goetz2011). The right to transfer is vested in the chief, family, lineage, or clan (Abdulai et al. Reference Abdulai, Owusu and Goetz2011). In Côte d’Ivoire, customary claims are recognized by the community but not legally secure under formal land laws (Dolcerocca Reference Dolcerocca2022). In both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, inland valleys are generally subject to the same land tenure arrangements as surrounding agricultural land. We found no evidence of distinct formal tenure rules for inland valleys from our interviews and policy documents in either country. However, their relatively higher soil fertility and water availability can give rise to informal or seasonal allocation arrangements within communities.

Access to land varies among different types of farmers (Sward Reference Sward2017). Smallholder farmers often depend on rental agreements or sharecropping arrangements (Alemayehu et al. Reference Alemayehu, Assogba, Gabbert, Giller, Hammond, Arouna, Dossou-Yovo and van de Ven2022). Farmers with inherited land tend to invest in long-term improvements, whereas those who rent or sharecrop may be hesitant to invest due to the uncertainty of their tenure (Diendéré and Wadio Reference Diendéré and Wadio2023; Noufé Reference Noufé2023). Adopting inland valley farming follows the following steps: land acquisition, initial land preparation, water management investments, and finally, depending on available resources and tenure stability, crop selection (Totin et al. Reference Totin, van Mierlo, Saïdou, Mongbo, Agbossou, Stroosnijder and Leeuwis2012; Niang et al. Reference Niang, Becker, Ewert, Dieng, Gaiser, Tanaka, Senthilkumar, Rodenburg, Johnson, Akakpo, Segda, Gbakatchetche, Jaiteh, Bam, Dogbe, Keita, Kamissoko, Mossi, Bakare, Cissé, Baggie, Ablede and Saito2017; Dossou-Yovo et al. Reference Dossou-Yovo, Devkota, Akpoti, Danvi, Duku and Zwart2022).

Sampling design and data collection

A multi-stage sampling procedure was used to select regions, inland valleys, and farmers. The study was conducted at the farm household level. In the first stage, four regions were purposively selected by AfricaRice and the project partner institutions to capture variation in farming systems. Within each region, a range of crops is being produced. In the second stage, a database of all inland valleys in the selected regions, including the geo-referenced location, was provided by national research institutions. Four selection criteria for inland valleys were identified based on scientific literature, information from partners, and transect walks: physical accessibility, level of development intervention, crop diversity, and water management type. We used a simple multi-criteria analysis by assigning scores to each of the four selection criteria, together with members of the national partner institutions. The scores were then summed to obtain one overall score for each inland valley, resulting in a ranking of inland valleys per region. In total, 32 inland valleys, the eight highest-scoring inland valleys in each region, were selected. In the third stage, reliable lists with information on farmers were obtained in each selected inland valley with the help of cooperatives, agricultural extension agents, and village chiefs, and a sampling frame was developed. The number of farmers selected per inland valley was proportional to the number of households per inland valley. We used a random number generator in Excel to ensure random selection. Finally, survey data were collected from 742 farmers: 369 in Côte d’Ivoire and 373 in Ghana.Footnote 4

Household survey data were collected in July and August 2018. We used the Rural Household Multiple Indicator Survey (RHoMIS) survey tool (http://www.rhomis.org) with additional questions specific to the study context. The RHoMIS household survey tool is a standardized modular survey questionnaire and analysis package with relevant questions for our research that captures important variables in agriculture (van Wijk et al. Reference van Wijk, Hammond, Gorman, Adams, Ayantunde, Baines, Bolliger, Bosire, Carpena, Chesterman, Chinyophiro, Daudi, Dontsop, Douxchamps, Emera, Fraval, Fonte, Hok, Kiara, Kihoro, Korir, Lamanna, Long, Manyawu, Mehrabi, Mengistu, Mercado, Meza, Mora, Mutemi, Ng’endo, Njingulula, Okafor, Pagella, Phengsavanh, Rao, Ritzema, Rosenstock, Skirrow, Steinke, Stirling, Gabriel Suchini, Teufel, Thorne, Vanek, van Etten, Vanlauwe, Wichern and Yameogo2020).

A survey questionnaire was prepared, pre-tested, and administered using Open Data Kit data collection computer software installed on Android-based tablets (Hartung et al. Reference Hartung, Lerer, Anokwa, Tseng, Brunette and Borriello2010). The data were collected by trained and experienced local enumerators who know the farming systems, speak both the local language and English, and have prior experience with survey work. Enumerators interviewed adult farmers. Each respondent farmer was given the option not to participate in the survey.

Description of variables and hypotheses

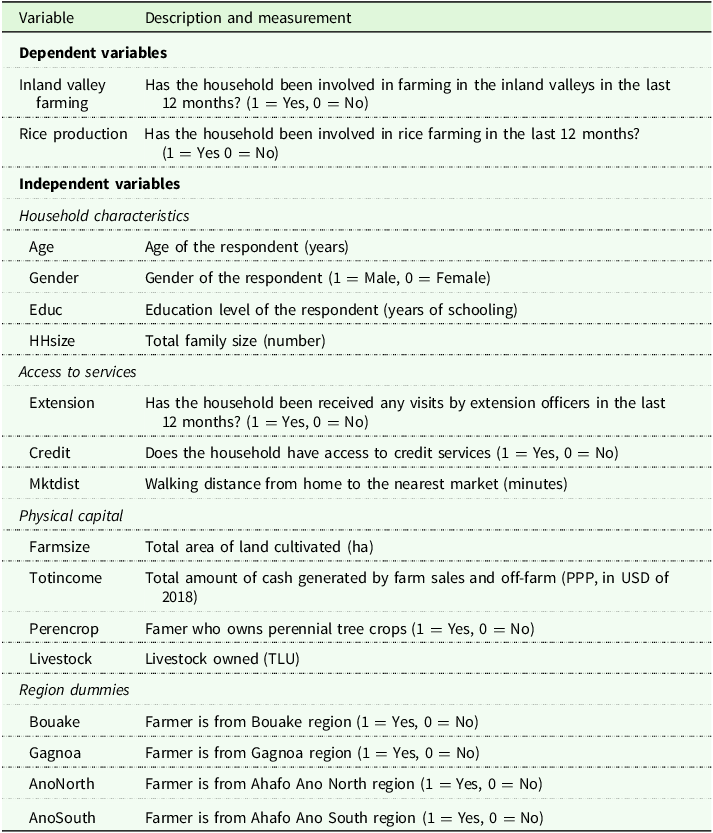

The selection of explanatory variables was guided by the study’s conceptual framework, economic theory, and existing empirical adoption literature. The main variables can be categorized into four groups: household characteristics, access to services, physical capital and regional dummies. Table 1 provides the names and definitions of all variables.

Table 1. Names and definitions of variables

Household characteristics

Many studies on technology adoption by smallholder farmers find that household size, age, education and gender of the farmers are key factors in decision-making (e.g., Feder et al. Reference Feder, Just and Zilberman1985; Ruzzante et al. Reference Ruzzante, Labarta and Bilton2021). Older farmers typically have more farming experience and exposure to production technologies and environments than younger ones, who often opt for non-farm activities (Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Teklewold, Jaleta, Marenya and Erenstein2015; Okeyo et al. Reference Okeyo, Ndirangu, Isaboke, Njeru and Omenda2020). Moreover, older farmers may have accumulated physical and social capital (Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Teklewold, Jaleta, Marenya and Erenstein2015). However, they often have short-term planning horizons, declining physical ability, and greater risk aversion, making them less open to new technologies (Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Teklewold, Jaleta, Marenya and Erenstein2015; Abegunde et al. Reference Abegunde, Sibanda and Obi2020). Hence, the effect of age on the decision to adopt inland valley farming and rice production is difficult to predict a priori.

Female farmers typically face more constraints than male farmers regarding the availability of resources such as land, labor, and cash, and they face more discrimination regarding access to inputs and information, which deters them from adoption (Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013). Therefore, we hypothesize that female farmers are less likely to adopt inland valley farming and rice production than male farmers.

Farmers with better education are more likely to be capable of assessing the benefits and drawbacks of new agricultural technologies, enabling them to make informed decisions suited to their farm operations (Abdulai and Huffman Reference Abdulai and Huffman2014). However, they may be less inclined to adopt labor-intensive technologies like inland valley farming and rice production if alternative opportunities offer higher returns on their labor and capital (Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013). Thus, the effect of education on inland valley farming and rice production is unclear a priori.

Household size influences labor availability and hence, farming decisions (Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013). Farmers with more workers in the household have more labor for agriculture, facilitating the adoption of labor-intensive technologies like rice production while reducing hired labor costs (Feder et al. Reference Feder, Just and Zilberman1985; Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013; Onyeneke Reference Onyeneke2017). However, farmers with large households may not have the financial resources to invest in inland valley farming or rice production since they may need the resources for other household needs (Kotu et al. Reference Kotu, Alene, Manyong, Hoeschle-Zeledon and Larbi2017; Onyeneke Reference Onyeneke2017). Thus, the effect of household size on the decision to adopt inland valley farming and rice production is unclear a priori.

Access to services

Agricultural extension agents are a primary source of information for farmers regarding technology adoption in many developing countries (Manda et al. Reference Manda, Alene, Gardebroek, Kassie and Tembo2016). Moreover, national and local authorities support rice production (Schmitter et al. Reference Schmitter, Zwart, Danvi and Gbaguidi2015; CARD 2019; AfricaRice 2020). Therefore, we hypothesize that access to extension services positively affects the adoption of inland valley farming and rice production.

Farmers in developing countries face liquidity constraints that prevent them from doing major investments, e.g., in water control infrastructure (Abdulai and Huffman Reference Abdulai and Huffman2014). Farmers who have access to credit may be able to make these investments and purchase additional farm inputs (including labor) needed to farm in inland valleys or produce rice (Rashid Reference Rashid2021; Ruzzante et al. Reference Ruzzante, Labarta and Bilton2021). Therefore, we hypothesize that access to credit and the decision to adopt inland valley farming and rice production are positively related.

Distance to the nearest market can influence farmers’ decision-making since a longer distance increases input costs and reduces profitability (Teklewold et al. Reference Teklewold, Kassie and Shiferaw2013; Huat et al. Reference Huat, Fusillier, Dossou-Yovo, Lidon, Kouyaté, Touré, Simpara and Hamadoun2020). Thus, farmers farther from the nearest markets are more likely to produce for subsistence rather than for sale, making them less inclined to invest. Additionally, longer distances can limit access to information and credit institutions (Erenstein Reference Erenstein2006; Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013). Thus, we hypothesize that distance to market is negatively related to the likelihood of adopting inland valley farming and rice production.

Physical capital

As a measure of the physical capital of the household, we include farm size, a dummy variable equal to one if the household owns perennial tree crops, livestock ownership (in tropical livestock units; TLU) and total household income (in purchasing power parity; PPP) as proxies of physical capital.

Farmers with more cultivated land may have more resources to invest in the adoption of new agricultural technologies (Teklewold et al. Reference Teklewold, Kassie and Shiferaw2013; Manda et al. Reference Manda, Alene, Gardebroek, Kassie and Tembo2016). However, farmers with relatively larger cultivated land may follow an extensification path, opting for less labor-intensive farming methods, whereas farmers with smaller land tend to engage in subsistence farming (Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Li, Zhang and Wang2022). Since inland valley farming and rice production are considered to be more labor-intensive (Balasubramanian et al. Reference Balasubramanian, Sie, Hijmans and Otsuka2007; Paresys et al. Reference Paresys, Malézieux, Huat, Kropff and Rossing2018), farmers with a large amount of cultivated land may prioritize upland farming and refrain from rice production (Paresys et al. Reference Paresys, Malézieux, Huat, Kropff and Rossing2018). Therefore, the effect of farm size on the adoption of inland valley farming and rice production is indeterminate.

The hypothesis regarding the relationship between perennial tree crop ownership and the decision to adopt inland valley farming and rice production is based on two key mechanisms: a production effect and a wealth effect. Perennial tree crops, such as cocoa, coffee, cashew nuts, and rubber, require more labor and resource allocation during the initial establishment stage of plantation (Feinerman and Tsur Reference Feinerman and Tsur2014; Asante et al. Reference Asante, Acheampong, Kyereh and Kyereh2017). Perennial tree crops can take up to eight years before they start to yield an economic return, depending on the species (Feinerman and Tsur Reference Feinerman and Tsur2014), which can limit farmers’ capacity to engage in other forms of agriculture. After the establishment period, the wealth effect starts to play a role. Perennial tree crop owners view their decision to grow perennial tree crops as an investment that provides higher returns and more financial stability and can be passed on to the next generation (Afriyie-Kraft et al. Reference Afriyie-Kraft, Zabel and Damnyag2020; Siegle et al. Reference Siegle, Astill, Plakias and Tregeagle2024). Furthermore, perennial tree crops can serve as collateral, improving access to credit and reducing liquidity constraints (Asante et al. Reference Asante, Acheampong, Kyereh and Kyereh2017; Afriyie-Kraft et al. Reference Afriyie-Kraft, Zabel and Damnyag2020). The financial stability of perennial crops makes farmers less likely to adopt riskier and more labor-intensive practices, such as inland valley farming or rice production, which is produced for own consumption with some additional production sold on the local market (Asante et al. Reference Asante, Acheampong, Kyereh and Kyereh2017; Afriyie-Kraft et al. Reference Afriyie-Kraft, Zabel and Damnyag2020). Although greater wealth is typically associated with lower risk aversion, the long production cycles and delayed cash flows from perennial crops can limit short-term liquidity and tie up household labor. This inflexibility reduces incentives to diversify into more labor-intensive activities, such as inland valley farming or rice production, even when overall income levels are higher. Therefore, we hypothesize a negative correlation between ownership of perennial tree crops and the adoption of inland valley farming and rice production.

In this study, livestock ownership is measured in tropical livestock units (TLUs). In the African context, livestock can function as a form of wealth and insurance, enabling farmers to cope with shocks (Ng’ang’a et al. Reference Ng’ang’a, Bulte, Giller, Ndiwa, Kifugo, McIntire, Herrero and Rufino2016). Livestock potentially eases credit constraints (Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Zikhali, Manjur and Edwards2009), which may support investment in labor-intensive practices such as inland valley farming and rice production. Besides, livestock farming and crop production can be complementary; for instance, manure can be used for soil fertility, while crop residues can be used as livestock feed (Asante et al. Reference Asante, Ennin, Osei-Adu, Asumadu, Adegbidi, Saho and Nantoume2019). From this perspective, livestock ownership may support inland valley farming and rice production. However, livestock husbandry, particularly in free grazing systems, which is common in inland valleys, requires substantial labor and land resources, which may compete with inland valley farming and rice production (Sanogo et al. Reference Sanogo, Toure, Arinloye, Dossou-Yovo and Bayala2023). Moreover, inland valleys are often seasonally flooded, limiting their accessibility and compatibility with livestock grazing (Mekuria and Mekonnen Reference Mekuria and Mekonnen2018; Sanogo et al. Reference Sanogo, Toure, Arinloye, Dossou-Yovo and Bayala2023). Therefore, we hypothesize that the relationship between livestock ownership and the decision to adopt inland valley farming and rice production is unclear a priori.

Total household income is the total amount of cash generated by farm sales and off-farm income. Farmers with higher total income may be able to adopt since higher income may provide farmers with greater liquidity, enabling them to invest in the necessary inputs to enhance farm productivity (Abdulai and Huffman Reference Abdulai and Huffman2014; Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Teklewold, Jaleta, Marenya and Erenstein2015). Nevertheless, inland valley farming and rice production involve labor-intensive practices and are associated with various health risks. This may discourage higher-income farmers from adopting these practices. Thus, the effect of farmers’ total income on adopting inland valley farming and rice production is indeterminate.

Regional dummies

Environmental, cultural, and institutional factors are likely to be similar for all farmers in the same region but may differ between regions. Since these factors are not fully captured by the other variables, we include region dummies in the models (Wauters and Mathijs Reference Wauters and Mathijs2014; Danso-Abbeam and Baiyegunhi Reference Danso-Abbeam and Baiyegunhi2017; Ojo and Baiyegunhi Reference Ojo and Baiyegunhi2020).

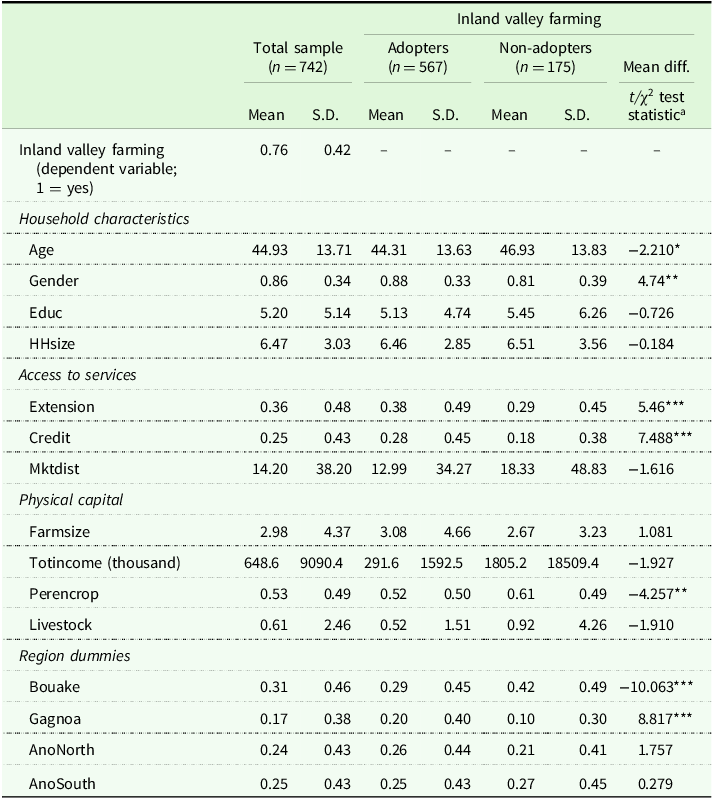

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the key variables of interest. In our sample, about 76% of farmers are engaged in inland valley farming. The average age of the respondents is 45 years. Additionally, the survey sample consisted primarily of male-headed households, with 86% of the respondents falling into this category. The average education level of the respondents is 5 years. The average household size of the respondents is 6.5 members, with an average farm size of 3 hectares. About 53% of households own perennial tree crops. Access to extension and credit services is limited, with only 36% and 25% of households having access to these services, respectively. This result indicates that credit and extension services are not widely available. The average walking distance from home to the market is about a quarter of an hour. Table 2 further presents the differences in the means of all independent variables between adopters and non-adopters of inland valley farming. The results indicate that adopters differ significantly from non-adopters in terms of age and gender. The share of households that own perennial tree crops is larger for non-adopters than for adopters. The share of households with access to extension services and credit is larger for adopters than non-adopters.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of variables used in the analysis of adoption of inland valley farming

Note: S.D. is standard deviation. */**/*** significant at 10/5/1% level.

a t-test and χ2-test are used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

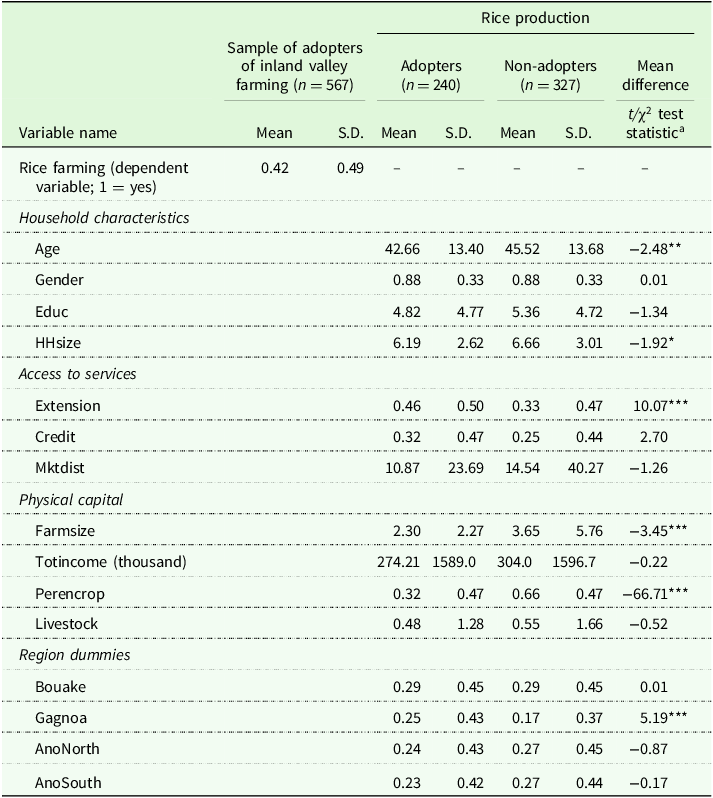

Table 3 presents an overview of descriptive statistics and statistical significance tests on the equality of means for rice production for only households that adopt inland valley farming. The table shows that 42% of households have been involved in rice production in the preceding 12 months. Households that opted for rice production have households that are, on average, younger than households that do not grow rice. Furthermore, on average, households that choose to grow rice have smaller farms and are less likely to grow perennial tree crops.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analysis of adoption of rice production, only for households that adopted inland valley farming (n = 567)

Note: S.D. is standard deviation. */**/*** significant at 10/5/1% level.

a t-test and χ 2-test are used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

In the regressions, we include the natural logarithm of both farm size and total income rather than their levels due to their skewed distributions.

Results

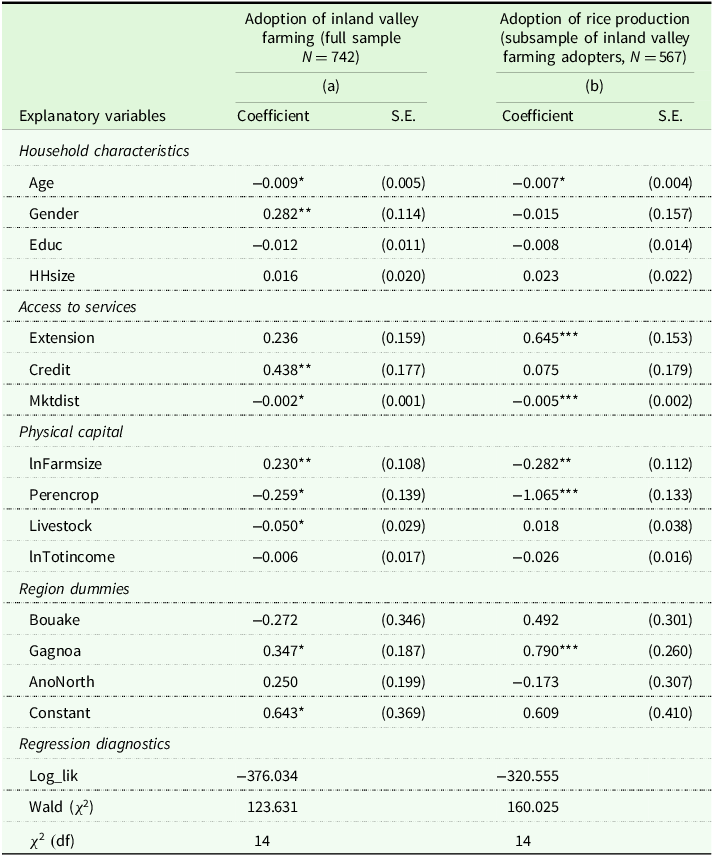

Table 4 presents the results from the probit regression analyses. The probit regression in column (a) presents the results for the adoption of inland valley farming using the full sample of 742 households. The probit regression in column (b) estimates the adoption of rice production for those farmers who adopted inland valley farming (567 households). The regression diagnostic statistics indicate that both models are well-specified and statistically robust. For the full-sample model of inland valley farming adoption, the Wald chi-square test (χ2 = 123.63, p < 0.01) indicates that the explanatory variables jointly and significantly explain the variation in adoption. Likewise, the rice production model, estimated on the subsample of inland valley farming adopters, shows a strong overall fit (χ2 = 160.03, p < 0.01).

Table 4. Probit model estimates of adoption decision of inland valley farming and rice production

Note: S.E. is the Standard errors clustered at inland valley levels in parentheses. */**/*** statistically significant at 10/5/1% level. The reference region is Ahafo Ano South.

Determinants of adoption of inland valley farming

Column (a) of Table 4 presents the regression results of the determinants of farmers’ adoption decision of inland valley farming. The results show that the decision to adopt inland valley farming is negatively and significantly associated with the age of the household. As expected, male farmers are more likely to adopt inland valley farming than female farmers. Access to credit services is positively associated with the adoption of inland valley farming, while the distance to the market has a negative correlation. The results also reveal that the size of cultivated land has a positive correlation, while ownership of perennial tree crops and livestock ownership is negatively correlated with the adoption of inland valley farming.

Determinants of adoption of rice production

The estimates of the determinants of farmers’ decision to grow rice for only farmers who adopted inland valley farming are presented in Table 4 of column (b). The results reveal that the age of the household is negatively and significantly correlated with the adoption of rice production. As expected, rice production is positively and significantly correlated with access to extension services, while distance to market has a negative correlation. The results also show that the size of cultivated land and ownership of perennial tree crops are negatively and significantly associated with the decision to grow rice.

Robustness checks

We further assess the robustness of the results using two different subsamples (see Supplementary Material – Appendix B ).

First, we perform a probit regression analysis of the adoption of inland valley farming with the sub-sample excluding observations in which non-household heads were interviewed, yielding 674 observations instead of 742 (Table B1, column a). Second, we perform a probit regression analysis of rice production adoption, restricting the sample to household heads who adopt inland valley farming, which yields 516 observations instead of 567 (Table B1, column b). This restriction excludes non-head respondents who may not have full decision-making or complete knowledge about household farming choices. This robustness check assesses whether differences in information between groups of respondents affect our findings.

The results (Table B1, column a and b) are largely consistent with those from the full sample. Age remains negatively associated with the probability of both inland valley farming and rice production adoption. Gender continues to exert a positive and highly significant effect on inland valley farming adoption and remains insignificant for rice production adoption. Access to credit is positively and significantly associated with inland valley farming, while it remains insignificant for rice production adoption. Extension services are positive but not significant for inland valley adoption, yet strongly positive and significant for rice production adoption. Market distance consistently exerts a negative and statistically significant correlation with inland valley farming and rice production adoption. Among the physical capital variables, farm size continues to be positively and significantly associated with inland valley farming and negatively and significantly associated with rice production adoption. Perennial crop ownership is negatively and significantly associated with both inland valley farming and rice production adoption. Livestock ownership remains negatively associated with inland valley farming adoption, while total household income becomes weakly significant and negative in the rice production adoption model, a finding not observed in the main results. Overall, the results of the robustness check indicate that it does not affect our main conclusions.

Discussion

Household characteristics

In subection “description of variables and hypotheses” we hypothesized that female farmers are less likely to adopt inland valley farming and rice production. We did not derive clear hypotheses for the role of age, education, and household size.

Our findings suggest that older farmers are less likely to adopt inland valley farming and rice production. This result may be linked to the labor-intensive nature of this agricultural practice, given the potential decline in the physical capability of older farmers. Moreover, it is consistent with the notion that older farmers often exhibit shorter planning horizons, potentially rendering them more risk-averse. This is particularly relevant in the inland valleys, where these agricultural practices are connected to health risks, ultimately impacting production. This result is also in consonance with earlier work on adoption (e.g., Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Teklewold, Jaleta, Marenya and Erenstein2015; Abegunde et al. Reference Abegunde, Sibanda and Obi2020; Ojo and Baiyegunhi Reference Ojo and Baiyegunhi2020).

Our findings confirm the hypothesis that female farmers are less likely to adopt inland valley farming than their male counterparts. This is consistent with the findings of some previous studies (e.g., Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013; Manda et al. Reference Manda, Alene, Gardebroek, Kassie and Tembo2016). This may reflect that women have less access to critical resources, such as land, education, training, and information on agricultural practices, as emphasized in studies by Bedeke et al. (Reference Bedeke, Vanhove, Gezahegn, Natarajan and Van Damme2019) and Ndiritu et al. (Reference Ndiritu, Kassie and Shiferaw2014). However, we do not find a statistically significant relationship between gender and rice production. This is likely attributed to the fact that access to critical resources, which may hold women back from adopting inland valley farming, does not seem to play a role when it comes to the adoption of rice production. Across West Africa, women’s adoption of new farming practices is often constrained by limited access to land, credit, and extension services (e.g., Theriault et al. Reference Theriault, Smale and Haider2017). In rice production, however, social norms and cropping systems sometimes grant women clearer roles and better access to communal resources in West Africa (e.g., Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Madagascar, Sierra Leone), narrowing these gaps (Kinkingninhoun Medagbe et al. Reference Kinkingninhoun Medagbe, Komatsu, Mujawamariya and Saito2020).

Education and household size do not seem to affect the likelihood of inland valley farming or rice production. This reflects the fact that the literature finds, for each variable, opposing effects when it comes to farming decisions and technology adoption.

Access to services

We expected access to extension services to positively contribute to both the adoption of inland valley farming and rice production. However, we only find evidence for rice production adoption, not for inland valley farming. These results are in line with previous research on adoption (Abdulai and Huffman Reference Abdulai and Huffman2014; Schmitter et al. Reference Schmitter, Zwart, Danvi and Gbaguidi2015; AfricaRice 2020; Ruzzante et al. Reference Ruzzante, Labarta and Bilton2021). The results suggest that farmers who have access to extension services are more inclined to engage in rice production, implying that extension services provide essential support in terms of technical assistance and market information related to rice production in the inland valleys. The coefficient for having received extension services in the past twelve months is not significant for the adoption of inland valley farming. This suggests that smallholder farmers are already familiar with inland valley farming, making them less reliant on support from extension services.

We hypothesized that access to credit would increase the likelihood of both inland valley farming and rice production. The hypothesis is confirmed for inland valley farming, which suggests that liquidity constraints play a role in the investments required for inland valley farming. Notably, this finding aligns with prior research on the role of credit in the adoption of new farming techniques (e.g., Teklewold et al. Reference Teklewold, Kassie and Shiferaw2013; Abdulai and Huffman Reference Abdulai and Huffman2014; Ojo and Baiyegunhi Reference Ojo and Baiyegunhi2020; Ruzzante et al. Reference Ruzzante, Labarta and Bilton2021). However, we do not find a statistical relationship between access to credit and rice production. This could be due to the government’s provision of seeds, fertilizer, and small equipment as incentives to rice farmers (Fofana et al. Reference Fofana, Goundan and Domgho2014; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Saito, van Oort, van Ittersum, Peng and Grassini2024).

Distance to market was expected to be negatively associated with the adoption of inland valley farming and rice production. Consistent with previous research work on adoption (e.g., Erenstein Reference Erenstein2006; Kassie et al. Reference Kassie, Jaleta, Shiferaw, Mmbando and Mekuria2013; Teklewold et al. Reference Teklewold, Kassie and Shiferaw2013; Djagba et al. Reference Djagba, Sintondji, Kouyate, Baggie, Agbahungba, Hamadoun and Zwart2018; Muriithi et al. Reference Muriithi, Menale, Diiro and Muricho2018; Tey and Brindal Reference Tey and Brindal2023), we find that distance to market has a negative correlation with both the adoption of inland valley farming and the adoption of rice production, though evidence is less strong for the former. This result could be that a longer distance to the market increases the costs of inputs and selling outputs, leading farmers to produce for their own consumption rather than sell to the local market.

Physical capital

As indicated in section “Physical capital”, for farm size, livestock, and income, we found that there are both factors that increase the likelihood of adoption of inland valley farming and rice production and factors that decrease these likelihoods. Hence, we were unable to formulate clear hypotheses for these variables. We hypothesized that ownership of perennial crops would reduce the likelihood of adoption of inland valley farming and rice production.

Farm size has a positive and statistically significant relationship with the adoption of inland valley farming. A possible explanation could simply be the fact that, given the amount of land that an individual farmer has in the uplands, starting farming activities in inland valleys implies an increase in cultivated area compared to a farmer who does not adopt inland valley farming. In addition, the size of cultivated land is an important measure of household wealth and resource availability, while the adoption of inland valley farming necessitates the availability of resources for the deployment of technologies such as power tiller equipment and small-scale mechanization. The result agrees with the empirical findings of Manda et al. (Reference Manda, Alene, Gardebroek, Kassie and Tembo2016) and Teklewold et al. (Reference Teklewold, Kassie and Shiferaw2013).

However, farm size is negatively and significantly correlated with the adoption of rice production, suggesting that farmers with more cultivated land are less likely to grow rice. While this finding may be surprising from the perspective of the agricultural technology adoption literature, it is in line with Chan et al. (Reference Chan, Tusting, Bottomley, Saito, Djouaka and Lines2022), who indicated that at the early stages of rice production, malaria vector densities are high in inland valleys, making rice production risky. Thus, wealthier farmers, in terms of farm size, may prefer alternative crops, while households with small farms may prioritize rice production, as rice is a staple food.

We find that ownership of perennial tree crops is negatively associated with both inland valley farming and rice production. One possible explanation for this result may be the higher returns and financial stability as compared to other crops, and the fact that perennial tree crops can be passed on to the next generation. This agrees with Afriyie-Kraft et al. (Reference Afriyie-Kraft, Zabel and Damnyag2020), who indicated the economic superiority of perennial crops over other annual crops, and Asante et al. (Reference Asante, Acheampong, Kyereh and Kyereh2017), who emphasized the financial stability provided by perennial tree crops. Another reason may be that, unlike annual crop cultivation, the initial stages of perennial crop cultivation are more labor-intensive than alternative crop cultivation, which leaves farmers with limited time to engage in alternative farming activities such as inland valley farming and rice production. This result is also in agreement with (Feinerman and Tsur Reference Feinerman and Tsur2014; Asante et al. Reference Asante, Acheampong, Kyereh and Kyereh2017). Moreover, from a welfare perspective, even though perennial tree crops offer greater long-term profitability and stable income, rice production provides more frequent harvests and short-term cash flow critical for household food security. This trade-off means that, although perennial crops are lucrative, rice production remains important for reducing food vulnerability and dependency on market purchases.

We find that livestock ownership is negatively correlated with the adoption of inland valley farming, but there is no statistically significant association with rice production. This result supports the notion that livestock husbandry, particularly under free grazing systems common in the study areas, competes with inland valley farming for land and labor resources (Sanogo et al. Reference Sanogo, Toure, Arinloye, Dossou-Yovo and Bayala2023). Farmers with larger livestock holdings may prioritize grazing areas and allocate household labor to livestock management rather than investing in labor-intensive inland valley cultivation.

We fail to find a statistically significant correlation between total household income and the adoption of inland valley farming and rice production. This may reflect the fact that the literature finds opposing effects when it comes to farming decisions and technology adoption.

Conclusion and policy implications

Inland valleys remain significantly underutilized for agriculture and rice production in West Africa. This paper examines the determinants of farmers’ decisions to adopt inland valley farming and to adopt rice production, using cross-sectional data collected from a sample of 742 smallholder farmers in the inland valleys of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Overall, the findings of this study indicate the important role of household characteristics, access to services, and the availability of physical capital in the adoption of inland valley farming and rice production.

This study provides new evidence into the importance of perennial tree crop ownership in agricultural adoption. Perennial crops provide superior economic returns, long-term benefits for successive generations and financial stability. Such context-specific information helps policymakers identify target farmers for promoting inland valley farming and rice production.

Our findings carry several policy implications. First, the analysis provides new evidence on the role of owning perennial tree crops in agricultural adoption in the inland valley context. Ownership of perennial tree crops is negatively associated with both inland valley farming and rice production. Extension services could be more effective by focusing on farm households who do not own perennial tree crops.

Second, farm size was positively correlated with inland valley farming but negatively correlated with rice production. The reason may be that farmers with small landholdings may have no option rather than prioritize rice production to meet their family’s food needs since rice is a staple food crop. As such, it underscores that farm size has a differential effect on adoption, depending on the type of agricultural practices. Policymakers and extension workers could factor in the effect of this physical capital variable.

Third, since access to extension services has a strong positive association with the adoption of rice production, policies and strategies of governments fostering rice production could be geared towards strengthening the agricultural extension systems. Furthermore, enhancing farmers’ access to credit is identified as a potential avenue for accelerating the adoption of inland valley farming. Therefore, policymakers could consider implementing measures such as expanding rural microfinance markets to improve farmers’ access to credit services.

Fourth, as female farmers show lower adoption of inland valley farming, policymakers could consider measures that ensure women have greater access to complementary inputs, such as land, labor, and extension services. It is crucial to recognize that women may face unique challenges and constraints that hinder their ability to engage in farming practices.

Fifth, as farmers with more livestock show lower adoption of inland valley farming, policymakers should design measures that address the potential trade-offs between livestock husbandry and valley cultivation. This could include promoting controlled grazing systems, offering incentives for integrated crop livestock practices, or targeting farmers with fewer livestock who may face fewer barriers to adoption.

Finally, our study is not without limitations. Our findings are derived from a representative sample of farmers in inland valleys in four regions of two West African countries. However, West Africa’s inland valley farming and rice production practices have unique dynamics and challenges, and it is essential to recognize that these features do shape agricultural adoption decisions. Although our results provide interesting new insights about the adoption decisions of inland valley farming and rice production in West Africa, more research is needed in other regions of the world to draw more general conclusions about inland valley farming.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/age.2025.10018

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [T.A], upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The support provided by Centre National de Recherche Agronomique (CNRA, Côte d’Ivoire), the Agence Nationale d’Appui au Développement Rural (ANADER, Côte d’Ivoire), and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research – Soil Research Institute (CSIR-SRI, Ghana) is gratefully acknowledged. Particular thanks go to Mohammed Moro Buri, Depieu Ernest, Boris Kouasi, and Aaron Mahamah for their support while conducting the survey and Djagba Justin for the study area map. Most importantly, we would like to acknowledge the hospitality and passion of smallholder farmers participating in the survey.

Funding statement

The research was funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (Grant Agreement number: 2000001206). Open access funding provided by Wageningen University & Research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.