This book is about unsteady combusting flows, with a particular emphasis on the system dynamics that occur at the intersection of the combustion, fluid mechanics, and acoustic disciplines – i.e., on combustor physics. In other words, this is not a combustion book – rather, it treats the interactions of flames with unsteady flow processes that control the behavior of combustor systems. While numerous topics in reactive flow dynamics are “unsteady” (e.g., internal combustion engines, detonations, flame flickering in buoyancy-dominated flows, thermoacoustic instabilities), this text specifically focuses on unsteady combustor issues in high Reynolds number, gas-phase flows. This book is written for individuals with a background in fluid mechanics and combustion (it does not presuppose a background in acoustics), and is organized to synthesize these fields into a coherent understanding of the intrinsically unsteady processes in combustors.

This book follows several texts or monographs which have treated related topics – including Toong’s Combustion Dynamics [Reference Toong1], Crocco and Cheng’s Theory of Combustion Instability in Liquid Propellant Rocket Motors [Reference Crocco and Cheng2], Liquid Propellant Rocket Combustion Instability by Harrje and Reardon [Reference Harrje and Reardon3], Putnam’s Combustion Driven Oscillations in Industry [Reference Putnam4], Fred Culick’s Unsteady Motions in Combustion Chambers for Propulsion Systems [Reference Culick5], or Lieuwen and Yang’s edited Combustion Instabilities in Gas Turbine Engines [Reference Lieuwen and Yang6]. Similarly, several dedicated texts on turbulent combustion have been written, including Peters [Reference Peters7] and Lipatnikov [Reference Lipatnikov8].

Unsteady combustor processes define many of the most important considerations associated with modern combustor design. These unsteady processes include transient, time harmonic, and stochastic processes. For example, ignition, flame blowoff and flashback are transient combustor issues that often define the range of fuel/air ratios or velocities over which a combustor can operate. As we discuss in this book, these transient processes involve the coupling of chemical kinetics, mass and energy transport, flame propagation in high shear flow regions, hydrodynamic flow stability, and interaction of flame-induced dilatation on the flow field – much more than a simple balance of flame speed and flow velocity.

Similarly, combustion instabilities are a time-harmonic unsteady combustor issue where the unsteady heat release excites natural acoustic modes of the combustion chamber. These instabilities cause such severe vibrations in the system that they can impose additional constraints on where combustor systems can be operated. The acoustic oscillations associated with these instabilities are controlled by the entire combustor system; i.e., they involve the natural acoustics of the coupled plenum, fuel delivery system, combustor, and turbine transition section. Moreover, these acoustic oscillations often excite natural hydrodynamic instabilities of the flow, which then wrinkle the flame front and cause modulation of the heat release rate. As such, combustion instability problems involve the coupling of acoustics, flame dynamics, and hydrodynamic flow stability.

Turbulent combustion itself is an intrinsically unsteady problem involving stochastic fluctuations that are both stationary (such as turbulent velocity fluctuations) and nonstationary (such as turbulent flame brush development in attached flames). Problems such as turbulent combustion noise generation require an understanding of the broadband fluctuations in heat release induced by the turbulent flow, as well as the conversion of these fluctuations into propagating sound waves. Moreover, the turbulent combustion problem is a good example for a wider motivation of this book – many time-averaged characteristics of combustor systems cannot be understood without understanding their unsteady features. For example, the turbulent flame speed, related to the time-averaged consumption rate of fuel, can be one to two orders of magnitude larger than the laminar flame speed, precisely because of the effect of unsteadiness on the time-averaged burning rate. In turn, crucial issues such as flame spreading angle and flame length, which then directly feed into basic design considerations such as locations of high combustor wall heat transfer, or combustor length requirements, are then directly controlled by unsteadiness.

Even in nonreacting flows, intrinsically unsteady flow dynamics control many time-averaged flow features. For example, it became clear a few decades ago that turbulent mixing layers did not simply consist of broadband turbulent fluctuations, but were, rather, dominated by quasi-periodic structures. Understanding the dynamics of these large-scale structures has played a key role in our understanding of the time-averaged features of shear layers, such as growth rates, mixing rates, or exothermicity effects. Additionally, this understanding has been indispensable in understanding intrinsically unsteady problems, such as how shear layers respond to external forcing.

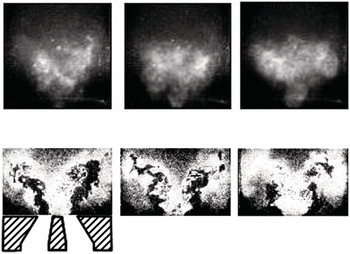

Similarly, many of the flow fields in combustor geometries are controlled by hydrodynamic flow instabilities and unsteady large-scale structures that, in turn, are also profoundly influenced by combustion-induced heat release. It is well known that the instantaneous and time-averaged flame shapes and recirculating flow fields in many combustor geometries often bear little resemblance to each other, with the instantaneous flow field exhibiting substantially more flow structures and asymmetry. Flows with high levels of swirl are a good example of this, as shown by the comparison of time-averaged (a) and instantaneous (b–d) streamlines in Figure I.1. Understanding such features as recirculation zone lengths and flow topology, and how these features are influenced by exothermicity or operational conditions, necessarily requires an understanding of the dynamic flow features. To summarize, continued progress in predicting steady-state combustor processes will come from a fuller understanding of their time dynamics.

Figure I.1 (a) Time-averaged and (b–d) instantaneous flow field in a swirling combustor flow. Dashed line denotes isocontour of zero axial velocity and shaded regions denote vorticity values.

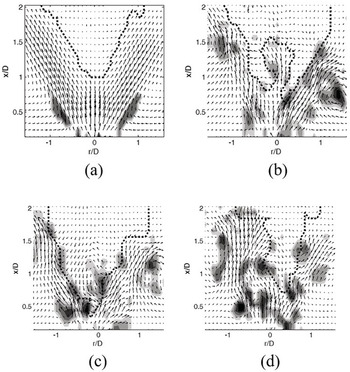

Modern computations and diagnostics have revolutionized our understanding of the spatiotemporal dynamics of flames since the publication of Markstein’s Nonsteady Flame Propagation [Reference Markstein9]. Indeed, massive improvements in computational power and techniques for experimental characterization of the spatial features of reacting flows has led to a paradigm shift in recent decades in our understanding of turbulent flame processes. For example, well-stirred reactors once served as a widely accepted physical model used to describe certain types of flames, using insight based on line-of-sight flame imaging, such as shown in the top three images taken from a swirling flow in Figure I.2. These descriptions suggest that the combustion zone is essentially a homogeneous, distributed reaction zone due to the vigorous stirring in the vortex breakdown region. Well-stirred reactor models formed an important conceptual picture of the flow for subsequent modeling work, such as to model blowoff limits or pollutant formation rates. However, modern diagnostics, as illustrated by the planar cuts through the same flame that are shown in the bottom series of images in Figure I.2, show a completely different picture. These images show a thin, but highly corrugated, flame sheet. This flame sheet is not distributed, but a thin region that is so wrinkled in all three spatial dimensions that a line-of-sight image suggests a homogeneous reaction volume.

Figure I.2 Line-of-sight (top) and planar (bottom) OH-PLIF images of turbulent, swirling flame [Reference Bellows, Bobba, Seitzman and Lieuwen10].

Such comparisons of the instantaneous versus time-averaged flow field and flame, or the line-of-sight versus planar images, suggest that many exciting advances still lie in front of this community. These observations – that a better understanding of temporal combustor dynamics will lead to improved understanding of both its time-averaged and unsteady features – serve as a key motivator for this book. I hope that it will provide a useful resource for the next generation of scientists and engineers working in the field, grappling with some of the most challenging combustion and combustor problems yet faced by workers in this difficult yet rewarding field.

Updates to the Second Edition

It is hard to believe that 10 years have gone by since we started this project. Many of the motivators and drivers of this book remain the same, but much has changed as well. From a societal point of view, the march toward decarbonization is accelerating, motivating topics like hydrogen combustion or combustor operability limits of alternative fuels. The commercial space market has taken off and combustion instabilities remain a key risk for rocket development. Major interest has developed in rotating detonation engines, where the wave dynamics in annular passages and coupled injector dynamics mirror many similar combustion instability topics. There is a resurgence of interest in data-driven approaches for the analysis of complex data sets, active control, or prediction of future or unmeasured system behaviors. Significant developments have also taken place in hydrodynamic stability, particularly reacting flows.

With this in mind, this book has been refreshed and updated. New sections have been added or major updates made in the following sections:

- Vorticity/circulation dynamics, Section 1.6.

- Exact solution of one-dimensional, linearized Navier–Stokes equations, motivating the canonical decomposition into entropy, acoustic, and vortical disturbances, Section 2.2.1.

- New example problem on randomly forced nonlinear oscillators in Section 2.5.3.3.

- Phase space dynamics of nonlinear systems, Section 2.6.

- Decompositions of data, including the Fourier transform, wavelets, partial orthogonal decomposition (POD), spectral POD, and dynamic mode decomposition, Section 2.7.

- New material and complete reorganization of Chapter 3, organized around different approaches for analyzing hydrodynamic flow stability, including a new section on mean flow stability theory and limit cycle amplitudes of globally unstable flows.

- Section 3.8 on instabilities in rotating and density stratified flows.

- Reacting jets in cross flow in Section 4.3.4.2.

- Stability of confined and multielement canonical flows in Section 4.7.

- Acoustic wave dynamics in annular passages in Section 5.6.

- Acoustic–entropy mode coupling in Section 6.2.3.

- Acoustic wave interactions with injectors in Section 6.3.3.

- Generalized discussion of surface dynamics, including constant property, passive scalar, and propagating surfaces in Chapter 7. Also reorganized material from Chapter 11 on premixed and nonpremixed flame surface dynamics into this chapter.

- Autoignition waves in inhomogeneous mixtures in Sections 8.2.2.4 and 9.2.

- Wave solutions of reaction–diffusion equations in Section 9.11, showing how fundamentally different types of wave solutions are possible depending on the shape of the reaction rate curve.

- Flame propagation in flows with deterministic velocity disturbances in Section 11.2.3.3, showing two fundamentally different regimes where flame propagation speed is controlled by localized points or the entire velocity field.

- Flame position, heat release response, and sound radiation from flames disturbed by three-dimensional disturbances in Sections 11.2.2.4, 12.3.1.3, and 12.4.3.2.

- Harmonic forcing effects of turbulent flames in Section 11.5.

- Flame configuration effects on its sensitivity to disturbances in Section 12.2.

- Heat release response of nonpremixed flames to harmonic forcing in Section 12.3.1.2.