2.1 Introduction

Policy growth is a widespread phenomenon in which the adoption of more policies leads to an expansion of administrative tasks that implementation bodies must perform. If this task expansion is not accompanied by a corresponding increase in administrative capacities, it can result in bureaucratic overload that negatively affects implementation performance.

Although these challenges associated with policy growth are well acknowledged (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019; Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2020), we do not have a clear understanding yet of whether evermore policies ultimately lead to an erosion of organizational implementation performance and, if so, under what conditions this happens. To address this question, first we need to develop a concept for capturing changes in organizational performance. This will enable us to measure the impact of policy growth on implementation performance in a systematic manner. In the second step, we need to identify the factors that explain why the consequences of policy growth on policy implementation performance vary across organizations. By examining these factors, we will gain a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms that determine how implementation bodies respond to the challenges posed by policy growth.

2.2 An Organizational Perspective on Implementation: The Concept of Policy Triage

In this book, we aim to complement mainstream implementation research by adopting an organizational perspective to study the impact of policy growth on implementation activities. Rather than focusing on the implementation of individual policies, we examine the entire policy stocks that organizations need to implement and the trade-offs they must make between competing policies. By taking this approach, we shift the unit of analysis away from the individual policy or bureaucrat and instead focus on the proliferation of implementation problems across a population of organizations responsible for implementation. This perspective allows us to explore the extent to which growing policy stocks and overburdening of implementation bodies contribute to the prevalence of implementation deficits in the aggregate.

Studying implementation deficits is complex and challenging as there are numerous potential problems that can arise during implementation, and different benchmarks are used in the literature to evaluate implementation effectiveness (for a detailed discussion, see Hupe & Hill, Reference Hupe and Hill2016). From a top-down perspective, implementation success or failure is typically measured in reference to the objectives defined in the decision-making process (Pressman & Wildavsky, Reference Pressman and Wildavsky1973). From a bottom-up view, implementation effectiveness is evaluated depending on the degree of policy adjustment under the consideration of local peculiarities (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky2010). Given these varying understandings, we use a definition of implementation deficits that is consistent with top-down and bottom-up analytical benchmarks as well as broad enough to capture different types of implementation problems. Specifically, we conceive of implementation deficits as the partial or complete neglect of an implementation task, directly or indirectly associated with a given policy, that leads to delay, distortion, or noncompliance with specific policy goals.

2.2.1 Organizational Policy Triage: Trade-Offs in the Implementation of Policy Stocks

We rely on the concept of policy triage to compare variation and change in organizational implementation performance. Policy triage implies that an organization privileges the implementation tasks related to certain policies over others. With growing overload, organizations are increasingly forced to take trade-off decisions of this kind. The higher the triage prevalence, the lower an organization’s implementation performance is, as certain policies and tasks are systematically and routinely neglected at the expense of others.

Organizations are constantly required to make trade-offs in their day-to-day activities, balancing competing priorities and allocating resources accordingly. A rise in policy triage, however, signals that organizations are making increasingly difficult trade-offs, putting them at risk of experiencing more implementation deficits and failures. Following this logic, the prevalence of implementation deficits is hence defined by the extent to which triage determines the organizational routines and internal proceedings of implementation bodies (Bayerlein, Knill, Steinebach, et al., Reference Bayerlein, Knill, Steinebach, Zink, Howlett and Tosun2021; Bayerlein, Knill, & Zink, Reference Bayerlein, Knill, Steinebach, Zink, Howlett and Tosun2021; Bayerlein et al., Reference Bayerlein, Knill and Steinebach2020). Consequently, we conceive of policy triage as an organizational pattern. Our analytical interest is in triage patterns that become apparent in organizational routines. As highlighted by Becker et al. (Reference Becker, Lazaric, Nelson and Winter2005), organizational routines constitute “a repository of organizational capabilities” and “a crucial part of any account of how organizations accomplish their tasks” (p. 775). Empirically, we thus expect that policy triage manifests in organizations’ informal routines or, in severe cases, even in their formal modus operandi.

Policy triage decisions may be driven by various logics related to organizational performance, including effectiveness, efficiency, as well as legal or political accountability. When the effectiveness dimension dominates, an organization may prioritize policies with a higher impact on policy goal achievement (Kaplaner & Steinebach, Reference Kaplaner and Steinebach2024). Efficiency concerns may lead an organization to prioritize less complicated policies and implementation tasks over more complex and time-consuming measures (Kaplaner & Steinebach, Reference Kaplaner and Steinebach2024). In contrast, the dominance of legal accountability may favor a “first come, first serve” approach, with older policies receiving more attention than new ones. Triage patterns may differ entirely if triage decisions follow concerns of political accountability. In such situations, implementation bodies may focus their work on newly adopted measures at the expense of older policies. Additionally, political accountability may lead to triage decisions based on organizational assessments of issue salience, resulting in implementation resources being concentrated on politically more salient policies (see, e.g., Spendzharova & Versluis, Reference Spendzharova and Versluis2013).

While detailed accounts for the variation in organizational triage logics are important, the central point of departure for this study is not to provide such accounts. Instead, the key point is that any instance of policy triage ultimately results in selective implementation and, consequently, implementation deficits. This holds true regardless of the rationale guiding implementation bodies in prioritizing certain policies or tasks over others. Put differently, implementation deficits are expected to increase always when administrative bodies rely on organizational routines that involve policy triage decisions in carrying out their implementation tasks.

2.2.2 The Degree of Policy Triage: Frequency and Intensity

Any triage or trade-off decision is the result of a choice that entails losses as well as gains. In our context, these choices refer to the ways implementation bodies allocate their scarce resources over the stock of policies and tasks under their responsibility. Depending on these choices, some policies or tasks might be privileged over others. The more organizations have embodied such routines of trading off their resources, the more this undermines their overall implementation activities. In short, the higher the degree of policy triage, the lower the overall organizational implementation performance.

The exact level of policy triage can be assessed by the combination of two aspects: triage frequency and triage intensity. Triage frequency captures how often implementation bodies engage in trade-off decisions. High frequency entails that policy triage is an important part of an organization’s routine and is performed on a regular basis. Low triage frequency, by contrast, refers to constellations in which trade-offs are not systematically embodied in organizational routines but rather take place periodically or under exceptional circumstances. Triage intensity, unlike triage frequency, refers to the extent of resource reallocation. A high triage intensity involves significant trade-offs, resulting in organizations fully abandoning the implementation of certain policies or the execution of important implementation tasks in favor of others. In such constellations, policy triage implies that certain organizational duties are de facto no longer performed. By contrast, triage intensity can be considered low if the trade-offs are less extensive and instead hinder, but do not entirely prevent, the execution of certain implementation tasks.

In sum, the level of policy triage is considered high if trade-off decisions are taken frequently by implementation bodies and involve the extensive reshuffling of resources between different policies and implementation tasks. By contrast, the level of policy triage is low when decisions on resource reallocation are infrequent and involve only minor shifts in resources. More details on the operationalization and measurement of these dimensions are provided in Chapter 3.

2.3 Theoretical Framework: Policy Growth and Organizational Policy Triage

Which factors account for variation in the degree of policy triage across implementation organizations? In addressing this question, we depart from the general acknowledgment of growing sectoral policy stocks and resulting administrative implementation burdens (see Chapter 1). If these burdens are not compensated by expansions in administrative resources, or if implementation bodies face resource cuts despite increasing burden load, the gradual erosion of organizational implementation capacities and the growing need for policy triage is the imminent result. If we accept this as the “baseline” or “default” scenario, the theoretical interest shifts to the factors that can account for the variation in the extent to which burden expansions are compensated by administrative resource expansions, that is, the factors that moderate the link between policy growth on the one hand and the prevalence of implementation deficits on the other.

The analytical framework we employ is focused on exploring the various conditions that impact on the extent to which policy growth leads to organizational policy triage. It is essential to note that our theoretical considerations are not deterministic in nature but rather aimed at identifying the different factors that influence the degree of policy triage in contexts of policy growth. We view these factors as configurative explanations that consider the complex nature of our subject matter. We begin with the premise that the process of policy triage is influenced by the arrangement and interaction of various factors, which may either substitute for or complement one another in their impact. In sum, the configuration and interaction of different factors are crucial in determining policy triage.

More precisely, our argument suggests that the relationship between policy growth and policy triage is influenced by three distinct factors: (1) blame-shifting limitations for central policy-makers; (2) the implementation authorities’ opportunities to mobilize external resources; and (3) the extent to which implementation authorities are committed to making things work despite lacking resources. The first two factors contribute to an organization’s vulnerability to overload, while the third factor relates to the organization’s willingness to compensate, buffer, and reduce overload.

2.3.1 Blame-Shifting Limitations for Central Policymakers

Organizations responsible for policy implementation are affected differently by increasing implementation burdens based on their vulnerability to overload. A primary factor affecting this susceptibility relates to the question to what extent policymakers have to take or may shift the blame for implementation failures. If politicians can easily shift the blame for deficient implementation, they have lower incentives to provide implementers with sufficient resources to cope with their growing burden load. Blame-shifting opportunities are largely structured by the underlying institutional arrangements shaping implementation processes.

We have shown in Chapter 1 that policy growth is a central feature of advanced democracies, regardless of the country or policy sector under study. New policy targets and instruments are added to existing policy portfolios, while existing arrangements are rarely replaced or terminated. Policy growth not only means that new policy elements are adopted constantly but also that an equally steady increase of new administrative rules is required to apply and implement those newly adopted policies.

Politicians are often driven to propose and implement new policies in order to showcase their responsiveness to public and interest group demands, as well as their competence in addressing complex policy problems (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019; Gratton et al., Reference Gratton, Guiso, Michelacci and Morelli2021). While the creation of new policies may not necessarily lead to an increase in the number of policies, if new policies are intended to replace less effective ones, research on policy dismantling and termination suggests that such situations are quite uncommon. Instead, political actors are more inclined to add new policies rather than substitute them, given the potential for resistance from anti-termination coalitions (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Jordan, Green-Pedersen and Héritier2012; Knill et al., Reference Knill and Steinebach2022). Consequently, the existing political incentive structures do generally encourage policy growth regardless of the exact policy sector in practice.

The same logic, however, does not apply to expanding the administrative capacities needed for proper policy implementation. Unlike policy growth, there are weak electoral incentives for politicians to invest in implementation capacities. Although bureaucratic resources can enhance implementation, it is challenging for voters to attribute such improvement to the actions of individual politicians and parties. This challenge is intensified in political systems that have multiple levels of governance or high levels of administrative decentralization. According to Lobao et al. (Reference Lobao, Gray, Cox and Kitson2018), politicians intentionally “off-load […] central government responsibility for administering and implementing services, policies and programs” to subnational governments (p. 395). In consequence, there is a lack of clarity regarding political responsibility for implementation, which undermines the incentives of politicians to make costly investments in administrative resources (Dasgupta & Kapur, Reference Dasgupta and Kapur2020).

Yet, not all political–administrative arrangements are equal in terms of the extent to which they obscure political responsibility and provide opportunities to shift blame in case of implementation failure (Bache et al., Reference Bache, Bartle, Flinders and Marsden2015). While some institutional structures clearly “cloud the clarity of responsibility” (Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2020: 30), others offer fewer opportunities for politicians to deflect blame. In the latter case, central policymakers have a vested interest in that implementing authorities receive (at least) some additional resources to effectively carry out policies.

Limitations on political blame-shifting opportunities for central policymakers arise from various factors, including the design of delegation structures and the level of political stability. Delegation structures are a direct reflection of the political distribution of policy accountabilities, particularly with regard to implementation. When the governmental level responsible for policy production is also tasked with implementing those policies, the attribution of responsibility is relatively straightforward (Heinkelmann-Wild & Zangl, Reference Heinkelmann-Wild and Zangl2020). In situations where implementation is delegated to organizations located at other levels of government, the accountability “costs” for central policymakers are notably lowered, and responsibility for implementation failures can be more easily shifted to the responsible governmental level. If implementation tasks are delegated to independent agencies, the degree of political accountability varies depending on the level of autonomy given to these agencies (T. Bach et al., Reference Bach, Van Thiel, Hammerschmid and Steiner2017). Typically, the chances of holding incumbent politicians accountable for implementation are greater with an overall lower level of formal autonomy granted to the agencies (but see Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2012).

Second, the level of accountability and associated political “costs” vary depending on the degree of political stability and the expected length of legislative terms. Gratton et al. (Reference Gratton, Guiso, Michelacci and Morelli2021) argue that politicians with short-term horizons are more likely to propose new policies to demonstrate responsiveness to societal demands without being constrained by the need to take formal blame for deficient implementation. Due to the time lag between policy adoption and the observation of implementation effects, short legislative terms decrease the likelihood that politicians responsible for policy adoption will still be in office when implementation failure occurs.

In sum, we can expect that the chance for policy triage is greater in institutional setups where central policymakers can come up with new policies without being held accountable for their successful implementation. In such circumstances, policymakers produce policies to receive credit for taking action but have little to no incentive to provide the resources required to ensure implementation effectiveness. Institutional setups with clearly defined responsibilities, by contrast, make it harder to shift blame for ineffective implementation. Consequently, we can assume that policy growth is at least partly offset by additional resources and, as a result, there are lower levels of policy triage among implementing authorities.

2.3.2 Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization

The vulnerability of implementation bodies to overload cannot be solely attributed to the blame-shifting opportunities available to central policymakers. Implementing authorities can actively employ strategies to mobilize external resources and to “lobby from within the system” (Loftis & Kettler, Reference Loftis and Kettler2015). To be successful in these endeavors, implementing authorities require the ability to form and articulate a unified opinion and they must be given the opportunity to convey their concerns to policymakers. What is more, it is imperative that adequate financial resources are available that can be distributed to the implementing authorities.

To effectively claim for resource expansions, implementation bodies must develop coherent positions. The potential to articulate a joint position presumes a minimum level of organizational integration and coordination between different implementation bodies, such as, for instance, the existence of associations of local or regional authorities that represent the interests of lower levels of government in central policymaking (J. M. Jensen, Reference Jensen2018). In a recent example in Germany, for instance, local authorities signed and published a joint statement indicating that their “load limit has been exceeded” (Gemeindetag Baden Württemberg, 2022: 4) and that, in consequence, “new standards, legal rights, and benefits can no longer be implemented” (Gemeindetag Baden Württemberg, 2022). The implementing authorities’ political “voice” also depends on their access to political decision-making (Cohen & Aviram, Reference Cohen and Aviram2021). Consultations can be a valuable tool for gathering perspectives and demands from implementation bodies. Unfortunately, consultations can often be seen as a mere formality, resulting in no real improvements on the “ground.” To truly impact overload vulnerability, policymakers must also take the implementation bodies’ perspectives into account (Lee, Reference Lee2022). This can be facilitated through various channels such as party–political ties or other informal backchannels.

Moreover, the success of mobilization efforts is closely tied to fiscal constraints. Given that the public budget cannot be expanded “ad infinitum,” all resource allocation decisions are redistributive in nature (Breunig & Busemeyer, Reference Breunig and Busemeyer2012). Organizations’ resource claims need hence to be justified in light of competing claims. As Flink (Reference Flink2017) points out, “organizations of the same structure can experience different levels of budgetary change as a result of varying amounts of friction brought about by environmental demands or other issues surrounding the organization” (p. 107). This suggests that implementation bodies will find it easier to mobilize external resources if the policies they are in charge of rank high on the government’s agenda and receive broad political attention.

In sum, we have observed that organizations differ in their vulnerability to being overwhelmed by increasing implementation tasks. The vulnerability of an organization to overload is influenced by several factors, including restrictions on blame-shifting and the ability of implementation bodies to mobilize resources. These factors may reinforce each other, with low constraints on blame-shifting coupled with limited mobilization opportunities resulting in high vulnerability to overload. Yet, compensatory effects may also come into play. Effective resource mobilization may outweigh the limited restrictions on central policymakers to simply “off-load” the responsibility for policy implementation.

2.3.3 Commitment to Overload Compensation

Organizations responsible for implementation are not passive receivers and mere takers of administrative burdens and policies. Rather, they have the ability to engage in organizational processes that can help them balance or compensate for the overload. This may involve utilizing organizational slack, reallocating resources, or improving internal processes, as suggested by Cyert & March (Reference Cyert and March1963). Additionally, overload can be mitigated by staff members who temporarily commit to efforts beyond their mandatory duties, such as working past regular hours or taking on extra tasks to support colleagues. In short, implementation bodies might do “policy repair,” using creativity, improvisation, and commitment to find contextual solutions for emergent implementation problems in response to scarcity (Masood & Nisar, Reference Masood and Nisar2022). However, not all administrations are equally committed to taking such measures. As shown by Peled (Reference Peled2002), administrations’ commitment to smooth policy implementation and reform can vary significantly. This commitment depends on the common organizational culture and the level of policy ownership.

Organizational culture is the aggregate of values, beliefs, practices, and attitudes that guide employee behavior and influence how work is performed within an organization (Ouchi & Wilkins, Reference Ouchi and Wilkins1985). A common organizational culture can include a strong belief in the organization’s overall mission and vision as well as a strong “esprit de corps” (Alvesson & Sandkull, Reference Alvesson and Sandkull1988). The emergence of both aspects is typically facilitated by a joint educational and professional background (Juncos & Pomorska, Reference Juncos and Pomorska2014). For instance, Kaufman’s (Reference Kaufman1960) classic work on the US Forest Service demonstrates how the agency’s recruitment and socialization practices created a unique spirit among the forest rangers that enables the organization to fulfill its mandate even under adverse conditions. A strong, impact-oriented organizational culture fosters a sense of shared purpose and values and encourages teamwork as well as unity among administrators. Cross (Reference Cross2013) highlights that “organizations with a strong common culture are more likely to remain cohesive, regardless of the circumstances” (p. 150). In situations of overload, this can mean that members of the organization are willing to go above and beyond what is formally required of them, such as working extra hours or taking on additional tasks (Wiley & Berry, Reference Wiley and Berry2018).

In addition, the willingness of implementation authorities to exceed their “regular” duties can vary depending on how they perceive the policies they are required to implement. If policies align with their organization’s goals and values, they are more likely to be motivated to take additional actions. However, during periods of policy growth and increasing workload, administrators may experience a growing sense of alienation from public policies that may result in “a cognitive disconnectedness” (Usman et al., Reference Usman, Ali, Mughal and Agyemang-Mintah2021: 81) from either specific or overall government policies in a particular sector (van Engen, Reference van Engen2017). This disconnection can stem from a feeling of policies simply being “dumped” on them or doubts that public policies will add value and contribute to society (see Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Bekkers and Steijn2009). To mitigate this, administrators need to develop and keep a sense of “ownership” toward the policies they implement. By fostering a sense of ownership and investment in policies, administrators can be motivated to take additional actions and (partially) overcome the challenges posed by overload. Among other aspects, the feeling of policy ownership can be improved by delegating more decisional discretion to the implementing authorities (Brattström & Hellström, Reference Brattström and Hellström2019; Tummers & Bekkers, Reference Tummers and Bekkers2013).

The earlier discussion suggests that policy growth does not always result in chronic overburdening of implementing organizations and continuous proliferation of implementation deficits. The prevalence of deficits depends on the interaction of three factors: blame-shifting opportunities for central policymakers, organizational mobilization of external resources, and organizational overload compensation. It is thus not evermore policies alone that cause implementation deficits but also the exact institutional setup in which these policies are produced and the type of organization charged with their implementation. By engaging in overload compensation and being flexible in response to workload changes, organizations can try to reduce implementation deficits and efficiently implement policies. Table 2.1 summarizes and provides an overview of our central theoretical arguments and expectations.

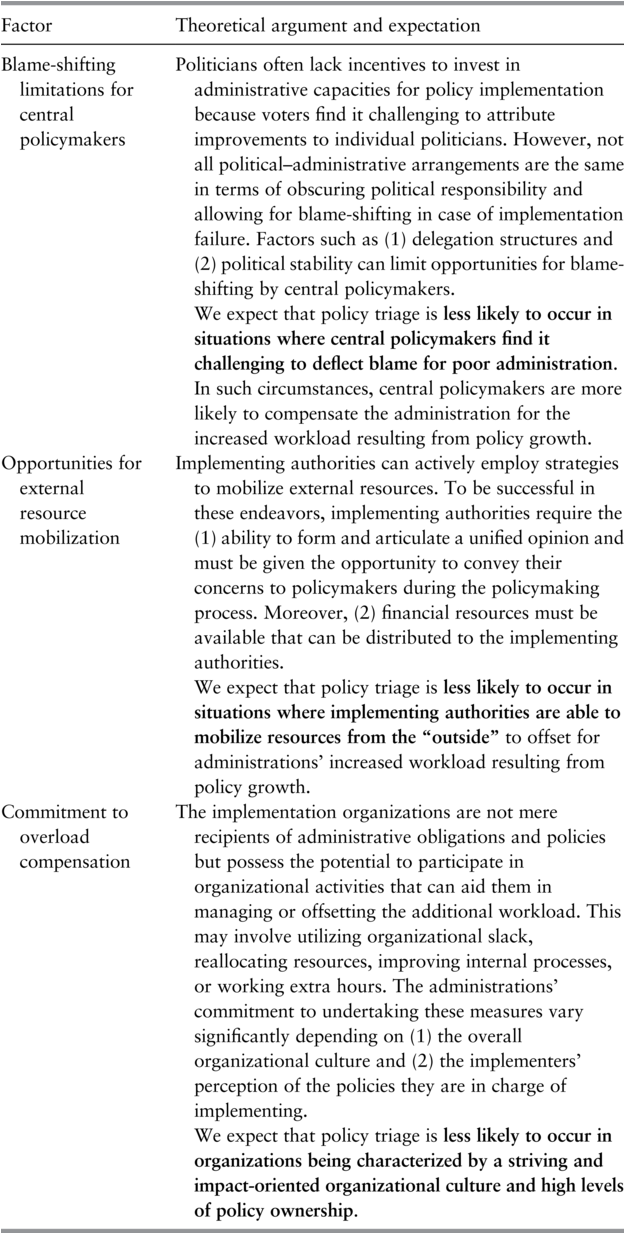

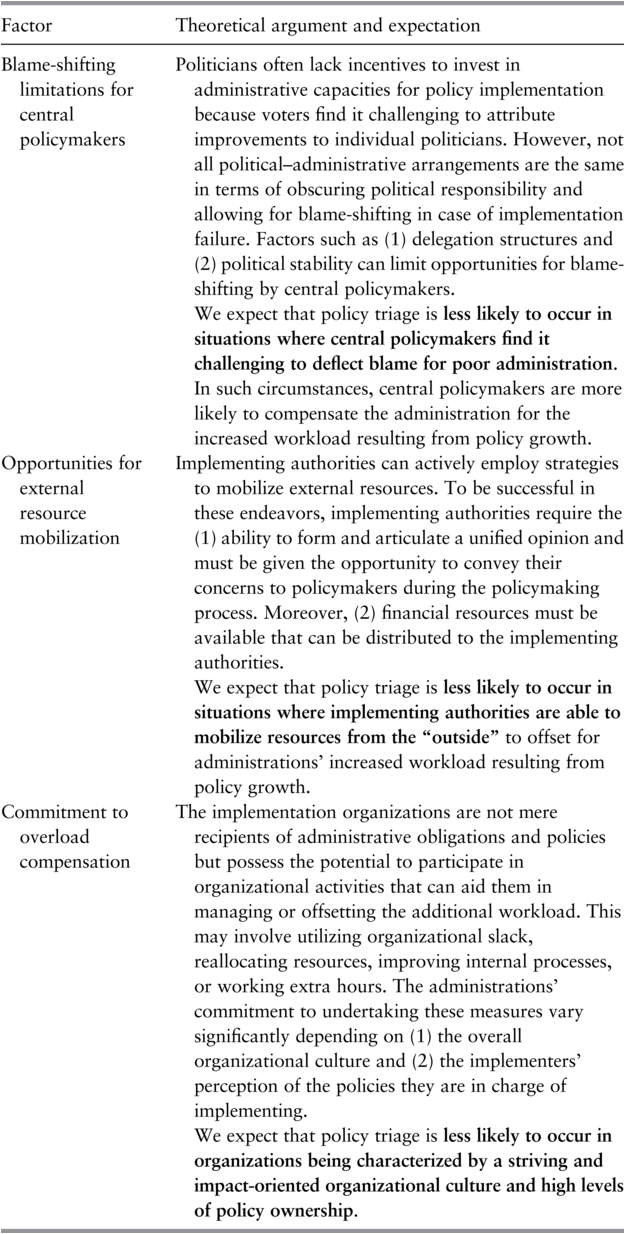

Table 2.1Long description

The table has two columns titled factor and theoretical argument and expectation. It has three rows.

Row 1. Blame-Shifting Limitations for Central Policy-Makers:

Politicians often lack incentives to invest in administrative capacities for policy implementation because voters find it challenging to attribute improvements to individual politicians. However, not all political-administrative arrangements are the same in terms of obscuring political responsibility and allowing for blame-shifting in case of implementation failure. Factors such as 1, delegation structures and 2, political stability can limit opportunities for blame-shifting by central policy-makers.

We expect that policy triage is less likely to occur in situations where central policy-makers find it challenging to deflect blame for poor administration. In such circumstances, central policy-makers are more likely to compensate the administration for the increased workload resulting from policy growth.

Row 2. Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization:

Implementing authorities can actively employ strategies to mobilize external resources. To be successful in these endeavors, implementing authorities require the 1, ability to form and articulate a unified opinion and must be given the opportunity to convey their concerns to policy-makers during the policy-making process. Moreover, 2, financial resources must be available that can be distributed to the implementing authorities.

We expect that policy triage is less likely to occur in situations where implementing authorities are able to mobilize resources from the outside to offset for administrations´ increased workload resulting from policy growth.

Row 3. Commitment to Overload Compensation:

The implementation organizations are not mere recipients of administrative obligations and policies but possess the potential to participate in organizational activities that can aid them in managing or offsetting the additional workload. This may involve utilizing organizational slack, reallocating resources, improving internal processes, or working extra hours. The administrations’ commitment to undertake these measures vary significantly depending on 1, the overall organizational culture and 2. the implementers’ perception of the policies they are in charge of implementing.

We expect that policy triage is less likely to occur in organizations being characterized by a striving and impact-oriented organizational culture and high levels of policy ownership.

2.3.4 Additive and Substitutable Effects of Different Factors

In the Section 2.3, we introduced three factors that we believe are critical in moderating the link between policy growth and the prevalence of organizational policy triage. But how do these factors and their individual effects relate to each other?

We expect that the factors we consider have additive and substitutable effects. The first aspect implies that the presence or high level of a particular factor alone cannot guarantee the complete absence of organizational policy triage. To cope with the substantial increase in implementation tasks that public administration faces, efforts are required at all levels and stages of the policy process. This includes (1) direct administrative offsetting during policymaking, (2) additional resource mobilization during implementation, and (3) exceptional commitment by implementing authorities to execute and enforce public policies. Therefore, low levels of policy triage can only be expected in situations where all three theoretical conditions are favorable and mitigate the adverse effects of policy growth.

The substitutability of effects means that we have no prior expectations regarding the exact effect sizes of the factors under analysis. We assume that challenges arising from policy growth overload can be addressed equally well from the top – by the central level – as well as from the bottom – by the policy implementing authorities. This assumption is consistent with the “synthesiz[ed] implementation literature” (Matland, Reference Matland1995), which gives equal weight to centrally determined aspects such as the institutional structure and available resources, as well as locally determined aspects such as the strategies and actions of the actors involved in the micro-implementation process.

2.4 Conclusion

This chapter started with the observation that the adoption of new policies without parallel expansions of implementation capacities will lead to a creeping overburdening of implementation bodies and negatively affect the overall implementation effectiveness. So far, this phenomenon has remained unexplored in conceptual and theoretical terms. Conceptually, the focus has typically been on the study of implementation processes of individual policies, while a more holistic approach capturing the implementation of policy stocks at the level of organizations has been completely absent. To address this deficit, we introduced the concept of organizational policy triage that takes account of trade-offs and interactions between different policies up for implementation.

We developed a novel theoretical framework that explains policy triage prevalence to account for organizational variation in policy triage. Our framework is based on the configuration of different factors that affect the interplay between policy growth and policy triage. First, implementation bodies’ vulnerability to being overloaded might vary as a result of different political opportunities to shift the blame for implementation failures. Second, overload vulnerability is affected by the potential of implementation bodies to effectively engage in the mobilization of external resources. Third, organizational overload compensation captures the organizational commitment to sound implementation and hence the disposition to reduce overload through internal efforts and reforms. The prevalence of policy triage in constellations of policy growth needs to be understood in light of the interplay of these different aspects that might substitute and complement each other in their respective effects.

Given that our theoretical argument is based on organizations rather than on countries or policies, our explanatory framework can be applied universally to implementing organizations regardless of the country or policy sector in question. This, however, also implies that we expect considerable variation in these patterns across different national and sectoral organizations in charge of policy implementation. Although countries might differ strongly in their administrative traditions, their state and administrative capacities, and the institutional design of their politico-administrative systems, this macro-level variation hardly captures the high diversity of implementation arrangements within countries. In short, we expect the configuration of factors determining policy triage to vary across different implementation bodies. For instance, local authorities in a given country will display patterns different from that of central agencies, which might again vary across and within policy sectors, and so on. It is exactly this variation that we are interested in analyzing in this book. In Chapter 3, we provide a detailed outline of our methodological considerations and research design for testing our theoretical arguments empirically.