Festive Culture, Urban Reticulation, Embodied Communities

The leisure-time space of the nineteenth-century European city, with its sociability and its café culture, fostered a climate for entertainments that in turn would be platforms for the assertion of national identity. National dances in cafés-chantants became a feature from Zagreb (with its tamburica ensembles and kolo dances) to Zaragoza (with its zarzuelas and jota). But city life was, in this century, also internationally enmeshed: the polka, first made popular in Prague in the 1830s as a national Slavic–Bohemian dance, became a veritable craze in mid-1840s Paris and went as global as the Viennese waltz.1

Polka and waltz exemplify the matryoshka scalarity that we also encountered when dealing with aggregation levels of language. Leisure-time sociability can oscillate effortlessly between the local and the transnational. The primary ambience for such activities is that of the town or city. As similar cultural leisure pursuits spread from city to city, these can reticulate (as we have seen in the case of choirs) into networks that have a regional or even national function. Leisure activities pursued locally mesh into trends with nationwide or even international outreach and influence.

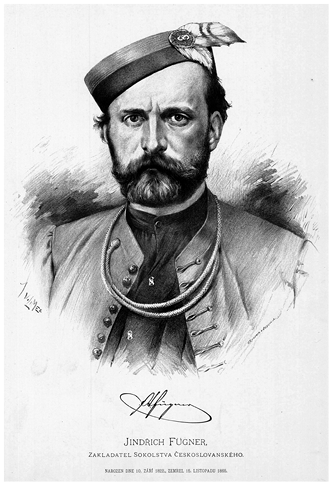

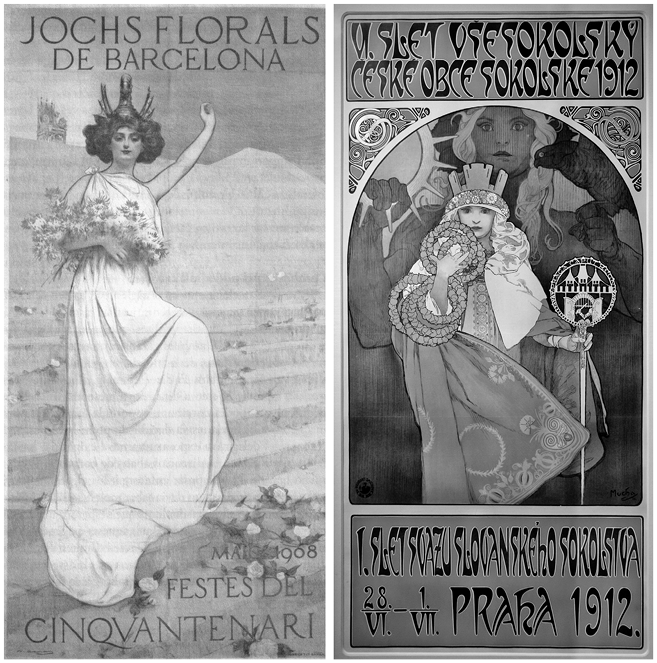

Sports and athletics follow this same pattern. Football is at the same time global and celebrated in England, where it originated, as a specifically local-cum-national tradition. Some sports are pursued in a powerfully nationalizing context. Events such as the Eleven Cities ice-skating tour in Friesland or cross-country skiing in Sweden and Norway symbolically assert the nation’s culture, tradition and identity. The Swedish Vasaloppet and the Norwegian Birkebeinerrennet are both named after nationally legendary historical exploits (see Figure 8.8). Sports associations such as the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland and the Sokol athletics clubs in many Slavic lands became nationalistic gathering places, and their sports events functioned as public mass demonstrations of nationalist commitment. Even mountain hiking was undertaken in a nationalizing spirit: for example, Slovak hiking tours in the Tatras or the activities of the Catalan excursionistas.2

One form of reticulation is competitive imitation – as when Estonians and Lithuanians used the German template of the choral society for their own national agendas. The athletic assertion of nationality had been heralded by the German Turnvereine, established in the 1810s by the firebrand nationalist Ludwig Jahn. Their German chauvinism excluded non-Germans from membership; and so Czechs in Prague and Jews in various cities engaged in competitive imitations. The former associated in the Sokol clubs, which became a powerful Austro-Slavic nationalizing platform and reticulated into most Slavic lands under the Habsburg crown. The latter formed Maccabi and Bar Kochba associations, which aimed to develop what Max Nordau called ‘muscular Jewry’ (Muskeljudentum) and which ultimately led to the international Maccabiah Games; these have been held every four years in Israel since 1932. A similar combination of global outreach and national positioning was articulated in the earliest Olympic Games (Athens 1896), developed as an international event but serving as a powerful projecting platform for Greek identity. From the local urban to the global, the national level is somewhere midway, a powerful public validator of leisure culture.3

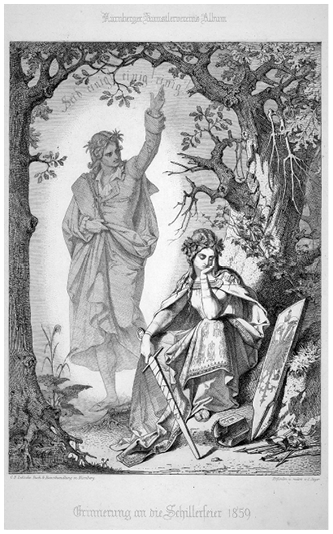

Across urban stepping-stones, a culture of modern, middle-class leisure amusements reticulated and created ‘embodied communities’ everywhere – with singers joining in a chorus, or dancers dancing together, or athletes competing on the field before a convivial crowd of spectators. The nineteenth century is not only the century of the ‘imagined community’ but also that of the ‘embodied community’. We encountered the Trachtenvereine earlier on, as well as the most prominent specimen of embodied sociability, choral singing. The enabling ambience of the embodied community was not restricted to inconsequential leisure-time amusements: the nineteenth century is also the century of the mass demonstration, and any mass event, culturally, could become a political one – as the Baltic ‘singing revolution’ showed. In the 1820s and 1830s, the Irish agitator for Catholic emancipation Daniel O’Connell harnessed the power of the mass rally to press home political points to an unwilling government; elsewhere, cultural occasions (such as the public funerals we have come across) provided a suitable respectability for assembling together in large numbers in urban squares and thoroughfares. Literary commemorations provided an important crypto-political platform. German commemorations of Schiller’s birth and death allowed the celebration of the author who had issued a clarion call for freedom of conscience (Gedankenfreiheit) in his Don Carlos, and who in his Wilhem Tell had celebrated the power of the people, once united beyond their local divisions, to shake off the yoke of tyranny: ‘Seid einig! einig! einig!’ (Figure 10.1). The Schiller commemorations of 1839, 1845 and especially 1859 (leaving traces in the dozens of Schiller statues and the many hundreds of Schiller Streets in Germany and also in the US) were ostensibly celebrations of a literary giant, and as such wholly unobjectionable, but they carried a potent connotation of ongoing resistance against reactionary politics in the different German statelets.

Figure 10.1 The spirit of Schiller exhorting a personified Germany to unify as she sits dejected under an oak tree, her imperial regalia cast down

The impact of the 1859 commemoration in Switzerland was especially noteworthy – and for good reason, because Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell had canonized that country’s foremost national hero. When Schiller was honoured with a monument in 1860, the Mythenstein, that occasion led to Gottfried Keller’s agenda for a nationally Swiss festivity: the mass-participation cultural Festspiel. The fifth centenary of the Battle of Sempach as celebrated in 1886 took the form of such a Festspiel: choral tableaux with collectively spoken texts and incidental music evoking important episodes from the national past. After Sempach 1886, Festspiele were held with increasing frequency throughout the 1890s and up to 1914. In addition, the Tellskapelle (a fresco-ornamented chapel recently constructed, marking the spot where Tell had made his daring leap into Gessner’s boat) became the destination of an official civic pilgrimage, held annually from 1884 on.

Commemorations of national poets carried particular weight in the non-sovereign communities of Central and Eastern Europe: Mickiewicz, Mácha, Gundulić and Prešeren in Poland, Bohemia, Croatia and Slovenia. But also in established states, a tsunami of statues washed over cities’ public spaces, each one the focus for wreath-laying, speeches and choral cantatas – from Camões in Lisbon to Runeberg in Helsinki, from Moore in Ireland and Burns and Scott in Scotland to Byron in Athens.4 A particular type of Festspiel had also emerged further west. The Welsh eisteddfod has been mentioned: it had long ago been a poetic gathering and was now reinvigorated from near obsolescence by cultural nationalists around Thomas Price in the 1820s and 1830. Not only did it inspire Bretons and other Celts, but it has developed to become an important annual event in Welsh culture. Cultural revivalists in Ireland and Scotland adopted the template for their Oireachtas and Mòd festivals.5

Between the Pyrenees and the Alps something altogether remarkable took shape along literary-historicist lines.6 During the Bourbon restoration, the city of Toulouse reinvigorated its own, very ancient but somnolescent literary festival, the jeux floraux (floral games). The tradition went back to the late Middle Ages as a form of poetic contest (of the type also celebrated in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg). Like so many medieval heirlooms it was now Romantically reinterpreted: as a vestigial, urban continuation of the region’s underlying troubadour tradition, which itself had of late been rediscovered and celebrated by philologists such as Fauriel. As they saw it, the troubadours had been the earliest to use the Latin-descended vernacular language to express a refined poetic sensibility. Their achievements antedated the development of a literary culture in Paris and Castile. And the city poets competing in their floral games were the civic successors of these chivalric Ur-poets. This was the prestige now shedding lustre on the revivified floral games. A youthful and as yet very conservative Victor Hugo made his literary debut by successfully competing in the floral games of 1819 and 1820, and the tradition had gathered steam by the mid-century.

From here, we can see the pattern of urban ‘reticulation’ setting in, much as in the urban concatenation of choral festivals in Germany: the format spreads from one town to the next. Each town, in adopting the festive format, ‘does its own thing’ locally as a form of urban sociability, with occasional exchange visits at most; but the repertoire they draw on is translocal and carries a national collective significance. Following the Toulouse example, Barcelonese city culture rediscovered its troubadour roots in the 1850s. When Verdi’s opera Il Trovatore premiered there in 1854, it was lost on no one that the storyline was based on the successful Spanish play El trovador by Antonio García Gutiérrez (1836). Whereas Welsh, Breton and Cornish poets were beginning to see themselves in ‘bardic’ terms at their eisteddfods and Gorsedds, here, poets were framing themselves as heirs to the troubadours of old. In 1859 Barcelona hosted its own first floral games, involving literary performances and contests and making many references to medieval troubadour and amour courtois culture. The successful contestants were given prizes of flowers wrought in precious metal, and pre-eminent writers were given the special title of ‘Master of the Joyful Arts’ (Mestre en gai saber). Barcelona closely followed the Toulouse pattern, and its Jocs Florals soon became a huge launchpad for a regionalist, and later nationalist, Catalan literary culture. The driving force was the philologist–poet Antoni de Bofarull, who in 1858 brought out a collection of contemporary poets writing in Catalan under the title The New Troubadours. In the same process, the familial relations between the regional Romance languages was renegotiated. Hitherto the regional idioms around Toulouse, Aix-en-Provence and Valencia had been referred to by more or less vague labels such as ‘Limousin’; but now their troubadour ancestry and their independent descent from late Latin were asserted (and hence their autonomous standing alongside Spanish and French) and their mutual relations redefined. (Not definitively, or to everyone’s satisfaction: the relationships between Occitan and Provençal and between Catalan and Valencian are still sensitive issues.) Catalan was definitively lifted to the A-list of European literary languages as a result of this movement, known as the Renaixença.7

The Barcelona festival in turn spawned floral games in Valencia, in Galicia (La Coruña and Santiago de Compostela) and in the Basque country, all of them regions that looked back to local feudal autonomy before the centralization of the modern Spanish state. There was also a backwash into France: across the Pyrenees there were joint initiatives, and when Catalan authors took refuge there from political repression, the result was a strengthening of ties and a further reinvigoration of Occitan/Provençal revivalism under the aegis of the Félibrige movement. These encounters inspired formatively influential writers such as Jacint Verdaguer and Frédéric Mistral, respectively. But the ideological trajectories diverged sharply: the Félibrige in France aligned itself with nostalgic conservative regionalism after 1871, while the Catalan movement remained radical in its pursuit of autonomy from Madrid’s reactionary autocratic rule. In both cases, what is nonetheless remarkable is how urban cultural festivals could reticulate, forming networks of mutual inspiration and mutual recognition that were translocal, transregional and indeed transnational as much as national.8

The City as Showcase: Modernity, Memory, Belonging

Walter Benjamin’s collection of notes and observations known as the Passagenwerk or ‘Arcades Project’ is organized around the covered shopping arcades of Paris, with their girder-and-glass roofs. For Benjamin, these were the new habitat for a modern leisure consumerism. They were places for loitering strollers (flâneurs) and chance encounters between strangers. They were also intensely scopic, visual: shops would offer their wares in windows that were like museum showcases or display cabinets; advertisement billboards and columns (the ubiquitous ‘Morris columns’) dotted Haussmann’s boulevards, bedecked with advertisements; even street-walking sex workers would join in this display culture, advertising themselves to lure potential customers. The key word for Benjamin was ‘panoramic’: named after coin-operated attractions where viewers could gaze at stereoscopic photographs of exotic locations. These commercial attractions formed part of a wider scopic regime that also included dioramas, waxworks, museums, viewing towers, zoos, botanical gardens, trade fairs and, later, the cinema. This display culture affected not only the city’s inhabitants and boulevardiers but also its visitors and the tourist industry: the modern city becomes an object of sightseeing and becomes itself a display platform. And often the displays would draw into their field of vision the wider world abroad: with its panoramas, botanical gardens and zoos, the city becomes a microcosm capturing global variety.9

This turn towards the spectacular Nebeneinander was also a turn away from narrative Nacheinander (see Chapter 8). As things were arranged visually in side-by-side displays, their historicity, the narrative one-thing-after-another was abolished. In the display cabinet called Paris, all of France and all the world were collapsed into a single location and all of the past was present in the urban here-and-now. That pattern had been initiated by the Paris-based, Cologne-born architect Hittorf, who in the 1830s had redesigned the large square between the Tuileries and the Champs-Elysées into what was called, aspirationally and programmatically, the Place de la Concorde. It had become the locus of multiple incompatible memories palimpsestically inscribed by the country’s successive regime changes since 1789: dedicated to Bourbon monarchs but also the place where Louis XVI had been guillotined. In order to retrieve a spatial sense of unity from the divided narratives of history, Hittorf’s design abolished all temporal references in favour of geographic ones. Two huge fountains on the oval’s focal points evoke the aquatic aspects of France: the country’s coastlines and its rivers. In the middle, an Egyptian obelisk was placed in 1836 (donated as a diplomatic gesture by Muhammad Ali Pasha). Its erection was a publicity stunt that demonstrated the tour de force of the French navy bringing it over with its new paddle-steamers and that carried overtones of the country’s imperial ambitions in Northern Africa (France was in these years engaged in the colonial conquest of Algeria). Around the square were placed eight statues of personified cities: Bordeaux, Brest, Lille, Lyon, Nantes, Marseille, Rouen and Strasbourg. They function almost as signposts pointing at distant places. The co-presence of these signposts (seated statues of female municipal deities) symbolically draws the various outlying corners of France, like so many spokes in a wheel, into the Place de la Concorde as a unifying hub of the country as a whole. And so Space serves to suspend Time, and Paris becomes a microcosm of the national territory. Hittorf repeated this gesture in his later Gare du Nord, that temple of modern transport, with on its roofline classicist statues representing all the cities now connected by the railways fanning out from that station. The statue of Paris stands in paramount position as the centre of it all, allegorizing what Benjamin would call the ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’.10

This spectacular spatialization was, of course, an overlay on the lingering influence of historicism. Even as Hittorf glorified space, distance and modernity, memorial statues to historical figures sprang up like mushrooms here as in all European cities, recalling a set of historical actors rendered canonical by Romantic historians and placed in public thoroughfares to assert the undiminished presence of the national past. Between 1830 and 1900, the Panthéon developed into the shrine to the great French fatherlanders that it still is today, with on the façade its dedication ‘To our great men: the grateful fatherland’ (Aux grands hommes la patrie reconnaissante). Some seventy-five free-standing statues were erected in Paris alone during this period (including twenty-two historical queens in the Luxembourg Gardens, and three to Joan of Arc), as well as some 300 smaller ones (or busts) that were set in the façade niches of the Hôtel de Ville, the Louvre, the Sorbonne, the Garnier Opera and other prominent public buildings.11

In many European cities, neighbourhoods newly constructed post-1870 outside old (formerly walled) city centres were programmatically given historicizing names, so as to provide a sense of continuity in these new streetscapes. Thus Barcelona’s Eixample and the expansion belt in Amsterdam, where the streets were named after admirals and painters from the country’s seventeenth-century ‘Golden Age’. The interplay between modern urban space and national memories is illustrated nowhere better than in the ground plan of the Parisian metro, familiar to anyone who has ever visited that city. The metro, a prime example of the accelerated technological modernity of the nineteenth century, is now a tangled web of linking connections. The stations usually take their names from the streets nearby;12 these are medieval in the old city centre (Châtelet, Louvre, Temple, Bastille, Notre Dame and many other church names); they evoke glorious events and victorious battles in the immediately adjoining belt (Rivoli, Vosges, Volontaires, Iéna, Alma, Austerlitz, Solférino, Wagram, Campo Formio, Pyramides, Crimée, Sébastopol, Trocadéro, Bir-Hakeim, Stalingrad), far-flung and, deeper in the suburbs, also longer ago (Tolbiac, Alésia). Marshals and generals are in evidence (Ségur, Hoche, Kléber, Daumesnil, Duroc, Drouot, Lourmel, Bizot, Molitor, Mouton-Duvernet, Pelleport and the defiant Waterloo hero Cambronne) as well as statesmen and politicians (Richelieu, Malesherbes, Mirabeau, Robespierre, Félix Faure, Gallieni, Gambetta, Vavin, Clémenceau, Charles de Gaulle, Louis Blanc, Jean Jaurès) and anti-Nazi resistance heroes (Bonsergent, Fabien, Lamarck, Guy Môquet, Gabriel Péri, Léo Lagrange). In the residential areas, we encounter names from arts, learning and literature (Balard, Curie, Jussieu, Mabillon, Monge, Pasteur, Réaumur, Louis Aragon, Victor Hugo, Raymond Queneau, Edgar Quinet, Voltaire, Emile Zola).

These lists give a sense of two things. The first is how many different ideological strands of political life in France are included, from Richelieu to Robespierre – with, to be sure, the radical ones concentrated in the more left-wing quartiers and arrondissements of Paris and the august literati in the more settled bourgeois parts. Second, the ultracanonical sits cheek by jowl with obscure names that by now need explaining (or looking up in Wikipedia, as I have done): the list ranges from celebrated household names to footnotes in specialized history. But even for those who are familiar with French history and culture and with the historical connotations of the more famous station names individually, the condensed and aggregated list may be somewhat startling in showing how very numerous and densely seeded all these names in fact are. The national-mnemonic background noise is much louder than we thought.

To be sure, the effect of a metro trip across Paris cannot amount to a propagandistic history indoctrination: in many cases, the unaware traveller will not even know if a name refers to a locality, a landmark or a person (‘Vavin’?). The semantic cloud that is the Parisian metro map is nothing if not diffuse, with many of the references hardly amounting to anything referential at all. But for all its diffuseness, the total effect of this accumulation of mnemonic signals is nonetheless powerful: it does not pedagogically ‘inform’ the metro traveller (i.e. guide them from ignorance to knowledge), but it offers a constant reaffirmation of the familiarity of these historical names and their droit de cité in the public sphere that is Paris (and, by implication, France). These names belong here, they are visible like endlessly repeated mantras at every stop and on dozens of signs, and this render the names, if not a concrete national reference, then at least a point of recognizability, a sense of belonging, and a habitual presence in one’s experience of public space. Habitual, that is, in the specific sense as defined by Bourdieu: a socio-cultural response that is so steadily and unremittingly present in one’s life that it ceases to be perceived as such and becomes unconscious, natural, like drawing breath or blinking one’s eyes.13

As such, the ‘habitual’, an ambient and latent presence, is the opposite of something we may call the ‘sensational’: something that is eminently noticeable, saliently standing out from the ordinary. And in the scopic regime of modern cities, much effort went into making display culture precisely that: noticeable, sensational.

But even as modern cities were developing into an archipelago of display platforms for the sensation of modernity, the countryside with its timeless peasantry was enshrined firmly in how the nation was imagined. That paradox – how in an increasingly urban modernity, the repertoire of the national identity became more rustic – will be addressed in what follows.

Narratives of Timelessness, Rustic Spectacles

The culmination of the nineteenth-century historical novel is Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1865–1869). It recalls the years 1805–1812. In the hands of a writer such as Tolstoy, the historical novel had outgrown its progenitor, Walter Scott. For one thing, War and Peace uses not the single ‘privileged witness’ protagonist but an entire palette of main characters, all with their own individual personalities and behaviours and together forming the collective tableau of an entire social class. Despite some sentimental vignettes of commoners – most importantly the meek and naively wise cobbler Platon Karatayev – the class at the centre of the book is firmly aristocratic: the action is set in mansions and among military officers. At the same time, Tolstoy sees the events as collectively experienced and somehow historically fated: great figures such as Napoleon may dream of ordaining, by their might and willpower, the course of events, but what determines the outcome of the war is ultimately the Russian Volksgeist as a transcendent instrument of the inexorable course of history – something that is intuited both by the visionary commander-in-chief Kutuzov and the saintly everyman Karataev. The moral tale of War and Peace is how an enervated aristocratic elite, conversing in French and pursuing its high-society life, finds its true character in the crucible of war: the Byronic prince Andrej Bolkonsky, the wavering count Pierre Bezukhov, the high-strung adolescent Natasha Rostov.

One celebrated episode revolves around Natasha’s winter visit to a relative’s country estate. Her uncle, though a nobleman, is rusticated and lives surrounded by his peasant servants. It is here that Natasha witnesses a song-and-dance evening with Russian folk music and is inspired to dance herself. Almost mystically, Tolstoy evokes how the movements of the folk dance come naturally and untaught to Natasha, like a slumbering instinct.

Where, how and when could this young countess, who had had a French émigrée for governess, have imbibed from the Russian air she breathed the spirit of that dance? … the spirit and the movements were the very ones – inimitable, unteachable, Russian – which ‘Uncle’ had expected of her. … Her performance was so perfect, so absolutely perfect, that Anisya Fyodorovna [a servant], who had at once handed her the handkerchief she needed to dance, had tears in her eyes, though she laughed as she watched the slender, graceful countess, reared in silks and velvets, in another world than hers, who was yet able to understand all that was in Anisya and in Anisya’s father and mother and aunt, and in every Russian man and woman.14

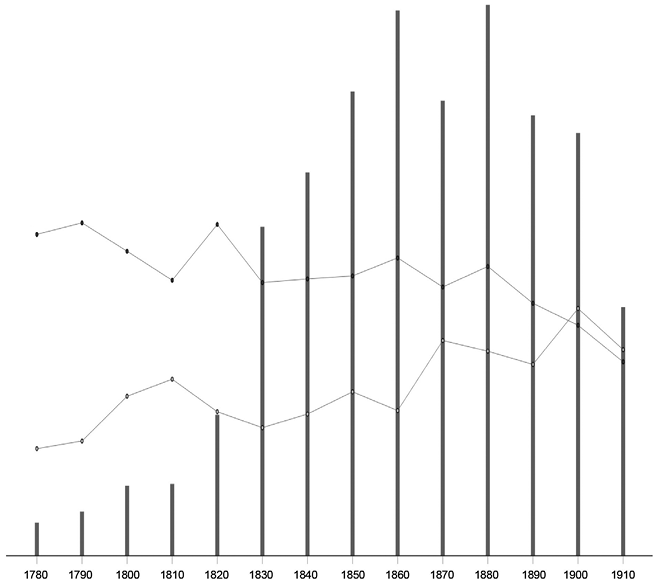

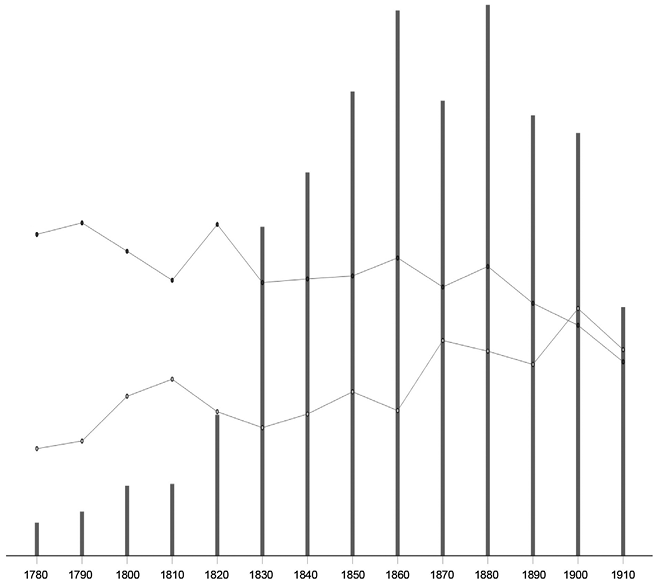

As a set piece, this scene has become famous and has furnished the title to an important cultural history study tracing the interaction between elite and folk culture in Russian history, Natasha’s Dance (Figes Reference Figes2002). My reason for highlighting it here is related specifically to the Romantic evocation of national character as an innate agency, truly a Volksgeist, and how indispensable traditional peasant culture had become by the 1860s as a validator of national authenticity: even in a historical novel and a novelistic philosophy of history. This turn from ‘past to peasant’ is noticeable both in literature and in painting over the course of the Romantic century (Figure 10.2). Not only does the modern state impose its national state structures on a backward-lagging peasantry (as described in Eugen Weber’s classic study Peasants into Frenchmen, 1976); the peasantry is at the same time canonized as an enduring, timeless presence at the heart of evolving modernity.

Figure 10.2 Shifting proportions of national-historical themes (upper line graph) and rustic ones (lower line graph) in 4,500 academic paintings, 1760–1910.

We have come across the sentimental presence of folk culture in Romanticism before, mainly in the Romantics’ interest in folksongs and folktales. For Herder, this interest was largely an assertion of the value of spontaneous, untaught art in comparison with the artificial requirements of (classicist) formalism; it dovetailed with Rousseau’s cult of innocent childhood and ‘noble savages’. The idyllic preference for a simple, rustic life over the stilted conventions of life at court or in high circles is of very long standing indeed, going back all the way to the arcadian and bucolic literature of classical antiquity.15 With Grimm and the Romantics, the ascendency of spontaneous authenticity over artificial contrivance gains a national-identitarian flavour: popular traditional culture is celebrated for having been unaffected by cosmopolitan or foreign-imposed ‘high’ culture and for having remained true to the nation’s proper, primitive, pre-civilizational origins – in other words, for being authentic in the root sense of that word.

Much of the medievalism of Romanticism – the fascination with a chivalric past – is already shot through with a folkloric interest in traditional rustic culture; and rustic idyll becomes increasingly prominent once historicist interest tapers off. Many ‘realistic’ tales and novels of the mid-century hold up life in the countryside as a wholesome alternative to the modernizing city, or as a sentimental alternative to modern pragmatic soullessness. The opposition systematized in the 1880s by the sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies was already in the air: between the traditional rural community (Gemeinschaft) and modern urban society (Gesellschaft). Community life, be it among the peasantry or on noble country estates, is evoked in German Biedermeier (post-Romantic) literature by such authors as Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (Die Judenbuche, 1842; Bei uns zulande auf dem Lande, posthumously published); it is what Dickens’s David Copperfield (1850) escapes to when he flees, on foot, from the London slums to his aunt’s cottage in Kent. The lure of the traditional countryside is evoked by George Sand (La Mare au diable, 1846); and it suffuses, with a cheerful nostalgic glow, Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz (1834). We see its loving, lingering traces in St Mary Mead (Miss Marple’s village) and Downton Abbey, in the Provençal tales of Alphonse Daudet and Marcel Pagnol, in the ‘Piccolo mondo’ of Don Camillo and Peppone.

To be sure, the countryside became the location for tragic and fraught tales as well as idyllic escapism: thus in George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss (1860) or Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891), or in Janaček’s peasant opera Jenůfa (1904). But even in these works, life in the countryside is still represented as ‘timeless’ and representative of deep ethnographic structures and emotional sincerity; and what is selected for ‘comfort viewing’ are still adaptations of Eliot’s and Hardy’s happier-ending tales: Silas Marner (1861) and Far from the Madding Crowd (1874).

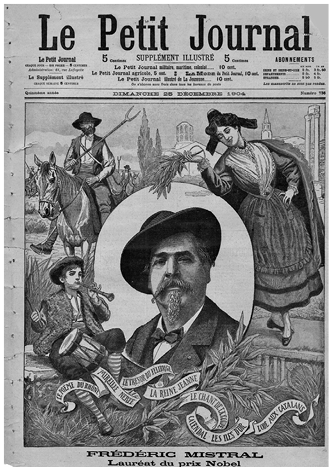

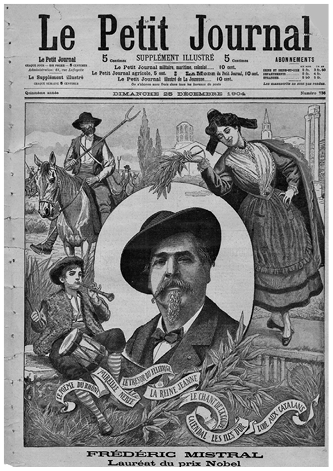

Mass-appeal literature commodified rustic local colour into a comfort zone for undemanding readers. In France, there was the regionalism of the Languedoc. Gounod’s opera Mireille (1864) was based on Frédéric Mistral’s dramatic poem in Occitan, Mirèio (1859; Figure 10.3); Mistral also inspired Alphonse Daudet, for example with L’Arlésienne, which was staged as a melodrama with music by Bizet (1872).16 In Germany, there was the phenomenon of Heimatliteratur and, later, the Heimatfilm, escapist idylls set in a timeless, unspoilt countryside with picturesque peasants and predictable plotlines (Berthold Auerbach, Village Tales from the Black Forest, 1842); this heile Welt or ‘unmarred world’ filled a market need in the suburbs of the modernizing industrial cities of the nineteenth century and in the guilt-burdened and war-ruined Germany of the 1950s. The peasant is here an essentially exoticist presence (not unlike Tolstoy’s Anisya Fyodorovna): always described as being alluringly different from the life-world of the readership. Heimat literature and the Dorfgeschichte (‘village tale’) accordingly became ‘domestic exoticism’ for the suburban lower middle classes.17

Figure 10.3 Newspaper coverage of Frédéric Mistral’s Nobel Prize for literature (1904).

Figure 10.3Long description

Front page of Le Petit Journal carries a color portrait of Mistral surrounded by rustic figures in a Provençal landscape: a farmer on horseback, an elegant young woman in traditional dress, a boy playing fife and drum. Underneath the portrait, there is a palm branch and scroll with the titles of his works.

The juxtaposition of traditional countryfolk and rustic landscape gives both an extrahistorical, ‘timeless’ quality. That effect had already been announced in Wordsworth’s ‘Solitary Reaper’ (1807), in which a singing maiden seen from afar, reaping corn in a wide valley, makes the poet (who cannot understand her, since she sings in Scots-Gaelic) wonder how historical, ancient or timeless her song is. The technique was also used by Thomas Hardy, whose Wessex novels often begin by describing, panorama-style, huge, brooding landscapes with a solitary wandering figure; as that figure is slowly zoomed in upon, the narrative detaches itself from the spectacle. Scott had used similar openings, but whereas he patented the trope of a cavalcade of knights making their way to a distant castle, Hardy’s wayfarers are peasants, countryfolk.18

In the transition from Wordsworth’s Romanticism to Biedermeier sentimentalism and Hardy’s naturalism, we see a ‘peasant turn’ even as Romantic historicism gave way to contemporary concerns. That transition from ‘past to peasant’ was powerfully affected by a sea-change in painting technique.

The Tube and the Dirndl: Plein-air Painting and National Costume

In 1841, John G. Rand patented a squeezable tin (or lead) tube for artist’s paint. Oil paint could now be kept from drying out and transported; it need no longer be mixed and used within the confines of the studio but could be taken on field trips, which heretofore had only been used for preliminary sketching or at best water-colour painting. Open-air oil painting had become a possibility.

One of the first to avail himself of this possibility was Gustave Courbet, the harbinger of a new current in painting that he himself called ‘Realism’. Rejected for an Academy salon in the mid-1850s, he mounted a private exhibition that he entitled Le réalisme. This challenge was all the more resonant because Courbet’s Pavillon du Réalisme formed part of a totally new type of display platform: that of the world fair or exposition universelle. The first world fair had been held in London – the Great Exhibition of 1851; it was followed by the Parisian Exposition Universelle of 1855. This was the noisy fairground that Courbet sought, bustling with five million visitors seeking a new type of commercial, leisure-time mass entertainment. It was a new ambience for cultural display, as Walter Benjamin was to observe later, expressing itself in commercial concourses such as dioramas, panoramas, zoos and shopping arcades. As the contemporary critic Champfleury noted, Courbet’s pavilion represented, for some, an audacious appeal to the public at large, bypassing institutions and selection committees, a sign of liberation; while for others it was an anarchic scandal, sullying art in the mud of fairgrounds. The controversy marked the beginning of an adversarial antagonism between succeeding generations, putting an end to the master–pupil filiations fostered by the academies. A few years later, in 1862, there was a crest in protests against the venerable Academy salon as the official showcase of academically endorsed art, as works by (among others) Courbet and Manet were rejected. As a palliative measure, a ‘Salon des refusés’ was organized; it included some of the more unconventional new work of the period and became a hatching ground for modern art. The Academy was losing its grip on the visuals arts.19

Ironically, these intensely urban, metropolitan developments changed the thematization of, precisely, the countryside. Fontainebleau and its great forest had become accessible by railroad. The railway station at Melun had opened in 1849, and the village of Barbizon was reachable from there; that soon became a haunt of plein-air painters armed with lead tubes and portable easels. They mainly did landscape and genre paintings of village scenes and evinced the new taste for ‘realism’, with its depiction of scenes from ordinary contemporary life. The brushwork became looser, crisp outlines made way for an evocation of shimmering, dappled natural light, and artists began to gather not in the studios at or around academies but in convivial, bohémien (and mixed-gender) countryside gatherings. The Barbizon school was the prototype of the artist colonies that would spring up all around Europe, taking over from the academies as the nurseries of great art.20

Plein-air painting, almost tautologically, focused on life in the countryside. ‘Realism’ à la Courbet, Cézanne and Van Gogh, or in the style of the Russian Peredvizhniki group and their colony at Ambramtsevo, tried to capture the modest, day-to-day essentials of life, often in all their poverty and with implied social criticism. That was a sharply different direction from the celebratory depiction of the nation’s historical heroism and glories. But in the process, the depiction of peasant figures in their traditional dress became a fixture, a pictorial icon. They are usually de-individualized, anonymous representatives of a class marginal to the art market but inspiring to artists and their social consciences; they are depicted in their habitual domestic, religious or agricultural pursuits (weddings, processions, milking or harvesting); and, if female, they are usually presented in a flattering light, with their colourful and exotic traditional dress as an eye-catching accessory setting off their elegant bearing to advantage (Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4 The Reaper (Kanutas Ruseckas, 1844; Lithuanian Art Museum, Vilnius).

Those genre paintings of young peasant women in traditional settings are so ubiquitous across Europe, from Brittany and the Basque country to the Baltic and the Bucovina, as to become mere ambient background noise to spectators nowadays. But they represented a new, anti-academic movement in nineteenth-century art that shifted the symbolic representation of the nation’s authentic character away from historical grandeur to what was, in the English phrase of that period, ‘racy of the soil’. And they also document traditional practices such as markets and fairs, seasonal feasts and religious processions, lovingly representing the colourful garb in which this all took place.

The depiction of nationally representative costume is not a Romantic invention but goes back to earlier centuries. The earliest examples antedate the invention of print. Maps of the seventeenth century habitually represent, in their margins, figures from various lands in their specific costumes as a display gallery of cultural diversity. Costume books, often depicting colourful sartorial traditions such as those of Spain, the Netherlands and the Scottish Highlands, profited from improved printing techniques and provided a panorama of local colour to armchair travellers, who could enjoy the genres of Voyages pittoresques or Los Españoles pintados por su mismos; book illustrations added their weight to this ambient tradition.21

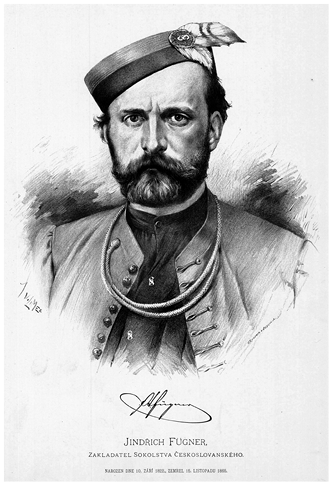

Costumes themselves acquired the function of signalling a national identity. Romantic German students dressed in an ‘Old German’ fashion proclaimed by Arndt in 1814 and inspired by Dürer portraits (as in the hairstyle and the outfit of Hoffmann von Fallersleben, Figure 4.4), with tight waistcoasts and open collars: rejecting all the frivolous elegance of French style. Caroline Pichler expressed a hope in 1815 that her Old German dress for ladies would be worn both in Berlin and in Vienna. A military element was added for those in the armed forces. Military uniforms were specific to the armies of different countries and regimes and tended to follow vernacular sartorial traditions (Hussars, Cossacks, Bersaglieri, Highland regiments). In the course of the nineteenth century, these obtained a powerfully national symbolism at a time when formal (civil) dress for men was becoming increasingly transnational and nationally indistinct. George IV wearing a Highland kilt during his Edinburgh visit of 1821 marked an adoption of this vernacular dress code as prestigiously ‘national’. The nobility of Hungary prided itself early on its Hussar-style, tight-waisted and heavily embroidered ‘Attila’ jackets and its tight, embroidered breeches, with the aristocratic accessory of the sabre like the one given to Liszt (Chapter 9). This style was that of the Empress Maria Theresa’s Hungarian Guards; it had become fashionable in Vienna and had been worn in the 1780s as an expression of protest against Joseph II’s attempts to centralize and Germanize the empire. A similar jacket style was worn by the Polish nobility (the so-called czamara), and that frog-and-loop jacket became popular as the čamara among Czech supporters of the Polish Uprising of 1831 and again in 1848 among supporters of Hungarian independence. From there it became a pan-Slavic signal, influencing the uniform of the many Sokol athletics clubs that sprang up in Bohemia and other Habsburg–Slavic regions from the mid-century (Figure 10.5).22

Figure 10.5 Jindřich Fügner in the Sokol club’s national Slavic uniform.

Thus traditional and ‘national’ dress began to make its way into the urban middle classes. But the main thrust of that development fanned out from the Alps. The mountain-dwelling population of the Tyrol had gained great sympathy and symbolic prestige following their 1809 insurrection against Napoleonic rule; the leader, the innkeeper Andreas Hofer, was glorified in song and later in painting and statues.23 Tyrolean garb shared in this prestige: woollen or leather knee-breeches (Lederhosen) and felt hats became the preferred dress code for leisure-time huntsmen and hikers.

Even before Hofer’s insurrection, in 1806, the Bavarian agricultural scientist Joseph von Hazzi had compiled a description of peasant dress styles in lower Bavaria as part of the new statistical inventory of state culture (Trachten aus Niederbayern nach den statistischen Aufschlüssen über das Herzogtum Baiern). Later, the historian Felix Joseph von Lipowsky published a collection of Bavarian popular costumes, to which he gave the epithet ‘national’ (Sammlung Bayerischer National-Costüme). The various regions of Bavaria (flanked by neighbouring Tyrol, the Black Forest and Switzerland) were at the forefront of this national-traditionalist dress revival under the Romantically minded Ludwig I of Bavaria. In 1842, the wedding of the Bavarian Crown Prince Maximilian with the Prussian Princess Marie featured Bavarian peasants in traditional costume; in 1853, the same Maximilian (by then King Maximilian II) ordained a decree for the ‘Encouragement of national feeling and especially of traditional dress’ in order to oppose ‘general homogenization and levelling’. The first societies with the express aim of cultivating traditional dress (Trachtenvereine) were founded (again in Bavaria, more particularly in the Alpine regions) in the 1850s. They joined into a regionwide federative association (Gauverband) in 1883; the number of its affiliates grew from fifteen associations in 1891 to sixty-one in 1906. Meanwhile other regional federations were founded, and in 1925 they merged into a Bavarian federation. The motivation was avowedly conservative-national: in 1886 King Ludwig II had ordained a decree to encourage the foundation of such societies ‘in order to preserve the beautiful dress of the mountain regions and the old dances … and to foster in these societies a communal feeling and love of the homeland and the fatherland’. Accordingly, such Trachtenvereine proclaimed as their aim ‘to throw up a barrier against the modern age while cultivating, and preserving for posterity, the dress, mores and traditions of our ancestors’.24

While Bavaria and neighbouring Tyrol were the heartlands of the Trachtenvereine, the trend spread across the German lands, from the Alps to the north Frisian islands and including Austrian and Swiss societies and associations. A generic women’s style known as the Dirndl (a blouse under a tight, often low-cut bodice, loose long skirt with apron, white stockings) emerged in the 1870s; it was originally worn by servant girls and as such became known to the urban tourist patrons of rural hotels and inns. Like the Lederhosen it became a popular fashion, also in non-rural settings, in the twentieth century. Having originally been fostered by royal patronage, the success of the Dirndl was mainly commercially carried: the Munich fashion house Wallach, established in 1900, specialized in these dresses and sponsored them being worn by servers at the Munich Oktoberfest,Footnote * when that event celebrated its centenary in 1910.25 The success of the Dirndl thus marks the adoption of peasant culture by the urban middle classes, facilitated by festive culture, leisure consumerism and countryside tourism (Figure 10.6).

Figure 10.6 Sigmund and Anna Freud in Austrian country dress.

A similar pattern is noticeable everywhere in Europe: folk traditions became commodified and an inspiration for middle-class leisure pursuits, although the particulars were very different from country to country. In Sweden and Norway, traditional patterns were used by feminist activists. In Sweden, Hanna Winge and Sophie Adlersparre, founders in 1874 of the still active ‘Friends of Manual Craftwork’, attempted to create cottage industries for rural women. In Norway, where photographs of peasants in traditional dress became popular from the 1880s, bunad (traditional dress) was used in a 1902 performance by the folklorist and folk-dance expert Klara Semb. This inspired the pamphlet Norsk klædebunad (1903) by her mentor Hulda Garborg, a social radical and cultural revivalist who was also active in the fields of traditional cookery, amateur theatre and women’s rights. We shall encounter this remarkable combination of stylistic traditionalism and social reformism further on, when discussing the Arts and Crafts movement that inspired Garborg.26

In the wholly different social context of Central and Eastern Europe, emergent cultural sociability found an outlet in choral singing. As women increasingly participated in mixed choirs, they opted for traditional local dress as a collective stage costume. Some of them may have had inherited specimens of such dresses in their wardrobes; if not, the presence of many plein-air paintings in the various local galleries and museums provided patterns from which to work.27 The fashion caught on in the Slavic portions of the Habsburg Empire and also in western provinces of Russia: the Baltic, Poland and Ukraine. In Lithuania, German Romantics such as the polymath Georg Sauerwein organized festivals where Lithuanians were invited to appear in traditional costume. Photographs were taken on those occasions, and Sauerwein used these as illustrative material in his lectures. Sauerwein also exhorted Lithuanians to maintain or to revive their ancient garments so as to display their nationality.28

At his suggestion, the choral director Vydūnas (pseudonym of Wilhelm Storost) had his Tilsit Singers’ Society perform in Lithuanian costume (for the women: white aprons, white embroidered shirts, the heads decorated with blue ribbons and green myrtle wreaths). National dress henceforth became a matter of Lithuanian self-identification; and, as in Latvia and Estonia, it was part of collective-performative public presence involving choral singing and amateur theatre. The attire was home-made (possibly after collective consultations).

From the Munich Oktoberfest to the Tilsit choral festival: the adoption of national costume is a veritable performance of national identity. The performers belong to the emerging modest middle classes, sensitized to national identity and traditional culture; the repertoire is that of traditional peasant culture, initially perceived through the ‘male gaze’ of plein-air painters and costume ethnographers, then appropriated by the wearers themselves. And the setting is something that emerges in the context of late-nineteenth-century modernity, along with its proto- or early-feminist undercurrents: that of the leisure-time display platform – festivals and fairgrounds, where town audiences could watch country performances. The countryside with its nationally characteristic traditions was exhibited.

Exhibiting the Nation: World Fairs and Nation-Branding

London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 was launched out of a pre-existing tradition of public trade and industry fairs. Like them, it displayed the products of agriculture, manufacture, trade and industry (with an emphasis on technologies and design innovation); but it was held in a dedicated new space, the famed Crystal Palace, with its novel girder-and-glass design – made possible by the invention of sheet glass in 1832, which was then widely used for railway stations and large greenhouses in botanical gardens. The Crystal Palace, as the embodiment and prototype of the exhibition platform, became itself a meta-exhibit, both containing the items of display and being one in its own right. This nesting recursivity was to become one of the defining features of world fairs henceforth: they became a telescoping sub-space, a window on the world and at the same time a microcosm of the world, where one could lose oneself among pavilions, and, within the pavilions, among the many exhibits on display there. These displays were often themselves of a compound nature, uniting various elements and performative practices – dances or musical performances with ‘authentic’ costumes and instruments, or ditto tea ceremonies. The Crystal Palace, copied or imitated in numerous other venues (New York’s Crystal Palace, 1853, Amsterdam’s Paleis voor Volksvlijt, 1855, Porto’s Palacio de Cristal, 1865, the Grand Palais in Paris, 1897), shared its pavilion typology and glass/girder ceiling with the century’s great shopping arcades and marked the transition from a fair (in the meaning of ‘marketplace for economic exchange’) to fairground (in the meaning of ‘a venue for multiple spectacular and immersive entertainments’): ‘sensational’ rather than ‘habitual’ culture.29

The Crystal Palace remained a venue for mass entertainment beyond the immediate occasion of its construction; as we have seen, a large choral festival was held there in 1861. It also heralded a new type of metropolitan landmark. While the fairs themselves were short-lived events, the sites tended to endure, and in some instances for longer, and more prominently, than one might expect. They needed to be constructed, often hastily, under the pressure of a commercial budget and an organizational timeline, and they needed to encapsulate a maximum of space in a minimum of building material; in that respect they were more like circus tents than real ‘palaces’, as they grandiloquently styles themselves. The term ‘pavilion’ does their ephemeral and thin, hollow nature greater justice. They could be removed to make place for successor buildings (like the Parisian Palais de l’Industrie, 1855–1897, and Palais du Trocadéro, 1878–1935), and they were prone to accidental destruction by fire. The New York Crystal Palace went up in flames in 1858, the Amsterdam Paleis voor Volksvlijt in 1929, the London Crystal Palace itself in 1936. Or they could just drop out of fashion, lose their function and be demolished. But in a surprising number of instances, things that were conceived as follies, extravaganzas or temporary hangars became fixtures in the cityscape. Besides the flagship examples of the Brussels Atomium (1958) and the Parisian Eiffel Tower and Grand Palais (1889 and 1900), we encounter, also in Paris, the Palais de Tokyo and the Palais de Chaillot (1937); in Prague, the Jugendstil Palace of Industry and the neo-Gothic Tourist Pavilion (1891); in Rome, the Fascist-era Palace of Italian Civilization (1942) and the neo-baroque Pan-Latin lighthouse on the Gianicolo hill (1911, Figure 10.7); in Lisbon, the huge waterfront Monument to the Discoveries (1940); in Barcelona, the waterfront Columbus Monument and the Triumphal Arch leading into the Parc de la Ciutadella (1888); in Seville, the enormous, tilework-embellished Plaza de España (1929) – to name only some prominent examples within Europe.

Figure 10.7 A landmark left by the 1911 world fair in Rome: lighthouse donated by Argentina to the host city as a ‘beacon of the Latin world’.

As these examples show, world fairs played an important role, in tandem with the rise in mass tourism, in turning cities into tourist attractions, studded with places of interest and entertainment spaces. As commercial enterprises, world fairs relied on mass attendance to succeed, and indeed on a larger attendance than the local population could provide. A logic clicked into place whereby the necessary crowds at world fairs would come from far away and stay only for a limited amount of time – the time of a holiday excursion. Their communal presence was, as a result, both numerous and transitory, and their engagement with the spectacle and its exhibits was necessarily and almost by definition superficial; hence also the great number of take-home souvenirs. What was proffered was a sampler of a world of goods and sights, and what was done by the audience was precisely that: they sampled. Heterogeneous cultural products from very different countries were taken in and tried out in quick succession. To be sure, some cultural exhibits could strike a responsive chord (the European interest in Japanese tea, in Indonesian gamelan music and wayang shadow-puppetry, or in Indian raga music are sometimes linked to world fair encounters) and play a role in cultural transfers; but in the majority of cases they left little more impact than a ‘flavour’, a vague familiarity based on a remembered and confused sense of local colour.

The exhibition tradition had until 1851 been intra-national, aimed at strengthening a country’s inner resources. The world fairs added to this a new, mercantilist dimension: that of an international arena in which many nations participated and in which competition and exchange were equally important and equally justified. Not only did nations vie with each other and boast of their own achievements, they also took a mutual interest in each other. What could a country expect from the world as a sphere of operations? What could it expect by way of imports, exports and trade opportunities? For each country to expect interest being taken in what it had to offer, it had to reciprocate by taking an interest in what the others were offering. As manifestations of growing economic internationalism, world fairs were giving the nation a new setting: not the enmity of its Other but its participation (both competitive and collaborative) in an international economic order.

The economic internationalization that world fairs exemplified and encouraged was counterbalanced by national self-positioning. As might be expected, culture provided the repertoire for that. World fairs themselves became an internationally coordinated enterprise, taking place, now in this, then in that metropolis and gradually crystallizing into a fixed system.Footnote * But universal and global as they claimed to be, the format very early on explicitly required participants to display themselves also in their local colour and national specificity, with exhibits of traditional lifestyles or cottage industries. And whereas technological progress and the intensification of world trade tended to lead to convergence between modern industries and economies, countries positioned themselves as individually recognizable point of interest – thanks to their cultural traditions.

This led to a triangle of possible registers in which participating nations presented their individuality to the world: either in attractively playful, highly decorated but makeshift pavilions in the style of fairground attractions; or as dynamically modern, internationally engaged and forward-looking (this leading to the great fashion of an almost futuristic ‘international modern style’ in pavilion design); or, finally, as rooted in authentic traditions that gave each country a national character of its own. These three modalities between them reflect the triangle of ‘amusement, modernity and memory’ that we have seen at work in the Parisian cityscapes as analysed by Walter Benjamin; and in that triangle, traditional peasant culture, historicism and high modernity are brought together in the nation’s international projection of its self-image. The use of vernacular architecture is a key element in the display repertoire, using either historicist pastiches of ancient landmarks or quaint, popular structures: Ottoman kiosks, Byzantine churches, Alpine chalets, American wigwams, rustic villages and traditional Flemish or Merry Old English townscapes. An expo fairground had to be experienced as an architectural zoo; and a specific and authentic culture became a trademark, a ‘unique selling point’ for participants.30

The eclecticism and mixing of registers (something that nowadays counts as the very definition of kitsch) was of course part and parcel of the format. This was a kermesse, a bazaar. The underlying constant was that the nation’s particular identity was here used as an identifying ‘brand’ in a trade emporium that mashed up the entire world into a welter of economic and cultural encounters and exchanges. In this light, the hoopla-national profiling that world fairs called for may represent the first step in a development that would ultimately lead to the condition of ‘banal nationalism’. World fairs came into their own in the century of trade internationalization. Trademarks had come into use around the time of London’s Great Exhibition, and by 1891 an attempt was made to regulate their use internationally (the Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks). By this time, nationality itself was beginning to develop into a trademark of sorts. Geographical indications of product provenance were first imposed by the British country-of-origin legislation of 1883, initially a protectionist measure against imports falsely pretending to be British-made. However, the imposition of labels such as ‘Made in Germany’ or ‘Swiss Made’ soon became boastful marks of quality; and between 1905 and 1919 France enacted a number of Appellation d’origine laws. Thus, as the mesh of international trade grew more tight-knit, a dual necessity took shape: the identification of a product’s national point of origin, and at the same time the identifiability of the nationality itself as a recognizable point of origin. Hence the use of national flags as brands and logos on representative ‘national’ products: watches, pocket knives and chocolate with Swiss flags, tulip bulbs and cheeses with Dutch flags, skiing resorts with Austrian flags. In this bidirectional dynamics – closer involvement of the nation-state in an international mercantile world order; greater need for the nation to set itself apart as recognizably different from the others – world fairs played a leading role.

A national flag on a consumer product such as a pizza box, pocket knife or pickled-herring snack is almost a textbook definition of what Michael Billig (Reference Billig1995) has termed ‘banal nationalism’. As with the names of the Parisian metro stations, the effect is one of ambient habituation. The diffuse and trivial carriers (pizza box, pocket knives or herring) turn the nation into a ‘hidden persuader’, giving to a consumer product a trademark or logo with an instant, automatic feel-good factor. The national brand is used not as a crude exhortation to ‘buy this product because it represents an admirable country’ but in a more indirect way: ‘We who bring this product to your attention do so on the basis of what we think is a shared affect between us and you, the customer: a reliance on the national values symbolized by this flag and applicable to this product.’ In advertising terms, the use of the flag is a ‘reason to believe’: it sends not a message in its own right but a meta-message serving to enhance the message that it accompanies, providing it with a subliminal feel-good factor.31

Alongside this ‘habitual’, unobtrusive nationalization, the display of exotically local-coloured culture has a more ‘sensational’ effect. The reliance on culture to provide characteristic distinctness and authenticity is now firmly co-opted by the modern state as a self-profiling strategy: for states, with their economic and trading policies, were the institutional participants in world fairs. World fairs, in other words, feed into the increasing instrumentalization of national identity for the benefit of state interests.

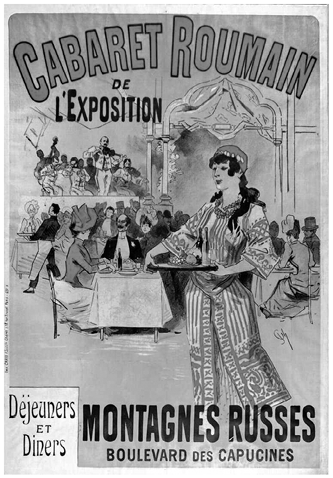

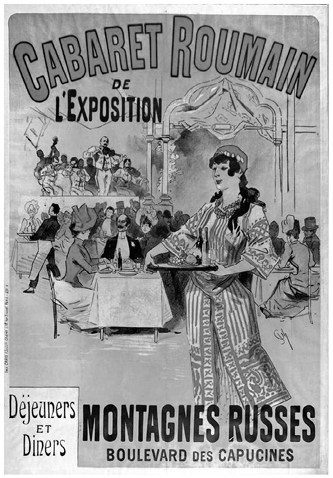

To be sure, these were not yet the nation-states that would emerge from the Great War; many of them were empires with colonies worldwide and considerable cultural diversity within their peripheral provinces. As a result, there is a fluid scalarity in their self-presentation. Historicism and technocratic modernity are used to project the metropolitan heartland; but at a sub-imperial level, the rustic provinces and the colonies were used to provide traditionalism, local colour and exoticism. In the cafés, cafeterias and beer gardens, regionally specific food would be served (coffee, tea, lager and sausages), enlivened by national music performances; with ‘Gypsy’ musicians being a particularly exotic and popular feature for Hungarian and Romanian cabarets (Figure 10.8).32

Figure 10.8 Poster for the Romanian cabaret at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle (Jules Chéret), showing a waitress in traditional dress and Romany lӑutari musicians in the background, with bourgeois patrons seated at the tables.

As the presence of those Romany musicians indicates, human subjects themselves were exhibited as local-colour features, in their traditional costumes. Sweden displayed mannequins in traditional peasant clothes and sold postcards depicting these; the Ottoman empire for its Vienna participation provided a sumptuous album of all the local costumes worn in its various provinces, from the Balkans to the Maghreb. Outside the immediate framework of the world fair, the Russian empire would follow that Ottoman template when it brought out a lithographed album of ethnic costumes in order to mark the Empire’s millennium; and in 1883 the imperial conspectus of its rich diversity would culminate in the Austro-Hungarian Kronprinzenwerk, a twenty-four-volume encyclopedic panorama of minority folk traditions under the benevolent aegis of the Habsburg crown prince. A highly specific development took place in Albania. The Garibaldist insurgent Pietro Marubi took refuge from political persecution in Shkodër and started a photographic studio there, soon specializing in portraits of locals in their traditional costumes. Over the decades, the Marubi studio remained active as the founder’s son and grandson took over, and their local postcards became popular among visitors, tourists and soldiers stationed in the area. This sustained production amounts to 150,000 negatives documenting a wealth of traditional costume and culture; it is now incorporated in Albania’s Marubi National Museum of Photography.33

Meanwhile, back at the fairground, some displays went one better than mannequins in display cases, photographs and lithographs: performers were on display in local-colour settings, employed in traditional handicrafts and wearing traditional apparel. This type of ‘folk village’ anticipated what would become the many open-air folk museums of Europe, beginning with Sweden’s Skansen resort near Stockholm (1891; the staff, like that at the Munich Oktoberfest, were dressed up in folk attire to enhance the sensation of authenticity). A similar performative turn was taken in the display of the trading empires’ colonial outposts: Indonesian dance and gamelan music were performed in Dutch exhibits featuring a Javanese folk village, Buffalo Bill displayed the horsemanship of his ‘Cowboys and Indians’ Rough Riders, and, notoriously, ‘primitive’ people from the colonies were put on display in ‘human zoos’. Thus the scalarity of imperial self-display ranged from the national heartland to the rustic periphery to the outlying colonies.

Used as we are nowadays to the power distribution inherent in ‘the gaze’, we cannot but consider the reduction of local cultures into an object of metropolitan spectacle as anything other than degrading. The colonial exhibitions held within Europe were part of a Eurocentric exploitation both of the natural resources and of the inhabitants of the colonies and their cultural riches, and as such these exhibitions form a standing reproach, a century later, to this European legacy. The sites that were designed to celebrate European colonialism (such as the ones at Brussels in 1897 and Paris in 1931) have now been refashioned into postcolonial reflections on this problematic heritage: the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren and the Cité de l’Immigration in Paris.

Degrading the ‘human zoos’ certainly were. The Jardin d’acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne, where they became a fixture, had originally been a zoo, founded to test the possible domestication of exotic animals. Most of its animals were eaten during the siege of Paris in 1870–1871. In 1877 the management started to mount ‘ethnographic spectacles’, twenty-two in total over the next decades. These were discontinued in 1931 and the Jardin became the amusement park it is today. ‘Acclimatizing’ was a misnomer: the subjects were exhibited with insufficient clothing in the uncongenial Parisian temperatures, and thirty-two of them died of exposure.34 The entire set-up confirmed or expressed existing power relations and was complicit in their underlying injustice. But such exhibitions were the outer end of a sliding imperial centre–periphery scale on which the ‘nation’ was as yet uncertainly positioned. Nor were all ‘existing power relations’ necessarily perpetuated or consolidated by these displays; world fairs were reflections and manifestations not only of centre–periphery imbalanc but also of shifts in that balance. Local-colour advertisement was quickly adopted by non-European empires or states to gain access to a new globalized market economy – especially by Japan and the United States, but also by the Ottoman Empire and independent Latin American states. As world fairs came to be hosted outside Europe (Philadelphia 1876, Melbourne 1880, Chicago 1893, St Louis 1904, San Francisco 1915), non-European countries found a platform for self-presentation bypassing the central position that the old continent had arrogated for itself. The careers of the important nation-building artists Raja Ravi Varma of India and Kakuzo Okakura of Japan were launched, tellingly, at the Chicago’s World’s Fair in 1893, which also provided a global rostrum for the fin-de-siècle guru Swami Vivekananda. And the ‘colonial’ expositions held in Calcutta (1883, 1923) and Hanoi (1902) and in various Australian cities (Sydney 1870 and 1879, Melbourne 1872 and 1888, Adelaide 1887) exhibit a striking difference from the ones in Paris or Brussels. No human zoos there; rather, those events signal colonies taking a more self-focused stance as regards their economic position in the world, announcing a presence in world trade that, at odds with a mere exploitative extraction economy, would later in the century lead into its logical consequence: independence. Autonomous participation in a world fair would also become a newly independent country’s manifestation of its place in the twentieth-century’s international order, as we can see from the presence of former imperial peripheries – Lebanon, Poland, Ireland and the Baltic states – at the Chicago Century of Progress Expo, 1933, and Paris’s Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, 1937. Europe’s Asian and African colonies would follow suit after World War II.

There is a parallel of sorts between the developing presence of extra-European colonies and intra-European imperial peripheries. The large ethnographic exhibition mounted by the Russian empire in Riga in 1896 was to some extent colonial vis-à-vis Russia’s inner minority cultures, to some extent also a Slavophile manifestation of pan-Russianism, but not insignificantly an event putting Riga on the map as the empire’s most important city after Moscow and St Petersburg, and a boost for Latvian awareness. The Bosnian-Herzegovinian pavilion that the Austro-Hungarian Empire (having annexed that territory) put up in Paris 1900 was designed by Alphonse Mucha, who used his unique combination of art nouveau style and pan-Slavic political sympathies to deliver an oblique message unintended by the imperial rulers. The intense regionalism that was deployed by Spanish designers fed into the localism of Barcelona, which co-hosted the 1929 event together with Seville; the Spanish presence was thus being riven between a Catalan wing at one end and an ‘Ibero-American’ one at the other.35

Late-nineteenth-century regionalism was, if anything, strengthened by a cult of traditional arts and crafts in the empires’ rustic peripheries. Patronizingly celebrated as ethnographic infotainment at the world fairs, the local artists and intellectuals nonetheless took strength and inspiration from a sense that Europe, like the world at large, was a transnational palette in which each cultural community could find its own way towards modernity and a coequal standing. What counted as quaint local colour in the fairground ambience became nationally iconic when repatriated into its home country: the Finnish Pavilion in Paris 1900 furnished the baseline design for the Finnish National Museum in Helsinki. Similarly, a Byzantine pavilion at the Paris 1900 Expo, designed by the Frenchman Lucien Magne, was re-erected, iron columns and girders and all, in Athens where it was consecrated as the church of Agios Sostis, Christ the Saviour. And in many countries, open-air museums of traditional peasant dwellings turned into internal, localized fairs celebrating the country’s own identity. Skansen near Stockholm was copied across Europe, with an agenda of internal identity affirmation rather than external local-colour display. Ironically, much as Heimat nostalgia is a form of ‘domestic exoticism’, cultural nationalism in subaltern regions often begins as internalized exoticism.

Europe’s imperial peripheries differed from actual colonies in a number of respects. Both lacked self-determination; both were in a subaltern position and had known violent subjection in their past. But the imperial provinces were not, on the whole, subject to an extraction economy; in the local cities and market towns there was an educated class, as well as a petty bourgeoisie and a white-collar working class with sufficient spare time to pursue cultural interests; and cultural interests could enjoy patronage and fostering from a home-grown elite. Scotland, Ireland, Catalonia/Aragon, the Basque country, Poland-Lithuania, Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia all had vestiges of an indigenous feudal past and could look back on their own high-prestige histories, which were frequently invoked as a morale-booster against contemporary subordination.Footnote * It is in the context of these sub-imperial peripheries that we see a particular flourishing at the fin-de-siècle of a new type of sub-imperial, culture-driven, late-Romantic nationalism, characterized by a new way of combining traditional vernacular culture with progressive politics. The spark-off moments came from the Arts and Crafts movement in London (on which more later in the chapter) and from an amateur theatre in Western Norway.

Henrik Ibsen and the Theatre

In the 1780s, Schiller had hailed the theatre as a ‘moral institution’ allowing for the development of a public sphere in modern Germany as it had once done in ancient Athens. Certainly the dramatic collaboration between him and Goethe in Weimar had created a rejuvenation of German letters. But for all that, the Romantic generation tended to prefer lyrical poetry and prose fiction to the drama. Goethe’s Faust (1808/1832) and Shelley’s The Cenci (1819) had been all but unplayable; theatres tended to provide social entertainment rather than exploring new artistic horizons. Even in France, where the advent of Romanticism had been heralded by Hugo’s Hernani (1830; or rather, its preface–manifesto), the theatres drifted to boulevard amusements with easy-going plays lavishly produced. The point of gravity for theatre productions shifted to musical performances, with grand opera as the prestigious flagship, surrounded by a flotilla of more popular ‘variety’ entertainments, from operetta to zarzuela and vaudeville. Occasionally a nationalizing impulse could emanate from here, but only incidentally. Thus Kajetan Tyl’s operetta The Shoemakers’ Feast of 1834 featured the nationally sentimental song ‘Kde domov můj?’ (‘Where is My Homeland?’), which grew in popularity to become the Czech national anthem in 1918.36

One place where the theatre played a fully national role was Copenhagen, where Adam Oehlenschläger set the tone with his dramatic evocations of the past (starting with his 1809 Lord Håkon the Rich). Oehlenschläger’s influence radiated out to Christiania (now Oslo), which recently had moved from Danish to Swedish rule but where Danish was still the language of high culture. In Norway, a budding writer, Henrik Ibsen, marked Oehlenschläger’s death in 1848 with the elegy ‘The Skald in Walhalla’; Ibsen, too, would at the beginning of his career write history plays in the Oehlenschläger mode. Now largely forgotten, they included Lady Inger of Ostrat (1855), The Vikings at Helgoland (1858) and Pretenders to the Throne (1863).

What was formative and innovative in Ibsen’s career as a playwright was his work for a small amateur theatre company in the provincial town of Bergen.37 Ibsen stayed there from 1851 to 1857, then relocating to the Christiania theatre until its closure in 1862. When Ibsen moved abroad (he would not return to Norway until 1891) he abandoned the thematics of semi-legendary heroic warriors. For his Brand (1864) and Peer Gynt (1867), he turned, tellingly, to the countryside: Brand is a moral tragedy set in a rural parish, and Peer Gynt relates the tall tales of a larger-than-life strongman (the play is now known mainly for the incidental music that Edvard Grieg composed for it in 1876). But from the mid-1870s on, Ibsen’s taste for realism (now no longer just a pictorial but also a literary current) came to the fore, and he turned to the emotional and moral problems of the contemporary middle classes living in post-Romantic and post-religious disenchantment. Plays such as The Pillars of Society (1877), A Doll’s House (1879), Ghosts and An Enemy of the People (1882) drew on a stagecraft of frugality that he had learned in Bergen but now disseminated globally: the plays premiered in Munich, Copenhagen, Chicago and Oslo respectively. As critics internationally hailed his work, Ibsen became the figurehead of a new approach to drama altogether, ‘literary theatre’. Literary theatre eschewed the glitz of the lavish boulevard productions; its audiences were small and the plays that were performed were muted in their production values, relying mainly on the dramatic and literary appeal of the plays’ dialogue. Ibsen’s unforgiving exposure of the soul-destroying nature of social conventions inspired avant-garde circles in the 1880s; G. B. Shaw and James Joyce were both card-carrying ‘Ibsenites’, and many small theatre troupes availed themselves gratefully of his sparse, almost spartan production values.

Ibsen’s influence took a specific turn in Dublin, where the London-raised Irish poet W. B. Yeats wanted to establish a literary theatre. Yeats’s taste (he had pursued his early career among fin-de-siècle aesthetes and ‘decadents’, and he was a snob) did not run to Ibsenite middle-class realism or naturalism; his penchant was more for symbolism, as performed in Parisian theatres staging the rarefied aesthetes Maurice Maeterlinck and Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. But Yeats’s political loyalty lay firmly with Ireland, culturally fallow ground in his view, and a literary theatre in Dublin could make use of amateur companies that had, for their part, certainly been inspired by Ibsen. The resulting Irish Literary Theatre was a hybrid in many senses, uneasily straddling the social radicalism of Ibsenites and Yeats’s elitist avant-garde aestheticism. Its use of the term ‘national’ was in effect glossing over two contradictory meanings of that term: for Yeats, ‘national’ was the opposite of ‘provincial’, meaning that Ireland could outgrow its drab vulgarity and take its place in cosmopolitan European modernity; for others, it fitted more in the mold of Douglas Hyde’s ‘de-anglicisation’, meaning that Ireland should abandon alienating foreign influences and return to its native-rooted cultural strength. Cosmopolitan or nativist? The history of the Irish Literary Theatre was marked by vehement altercations between these two wings throughout its existence.38 The plays in its repertoire similarly oscillate between international avant-garde and de-anglicizing propaganda.

What was beyond doubt was the high quality of the repertoire and of the acting: this theatre was innovative and inspiring, and at its best it managed to draw on Irish themes and settings (both legendary-heroic and contemporary-rustic, past and peasantry) to implement a non-complacent, nonconformist, innovative agenda. The unprofessional background of the actors became an asset: they delivered their lines without ‘hamming it up’, in a pensive manner that suited the theatre’s ‘literary’ nature. The Irish theatre acquired a high reputation, also in Britain and the US, and deliberately positioned itself as ‘artistic inspiration coming from the margins’. What Bergen was to Swedish-dominated Norway, Dublin was to the English-dominated British Empire.

The Ibsenite turn inspired many grass-roots ‘national’ theatre companies and playwrights in other sub-imperial cities across Northern Europe: Reykjavík had its Ibsenite moment in 1897 when the Leikfélag Reykjavíkur (Reykjavík Theatre Company) was founded; the instigators were mindful of the work of the Norwegian theatre in Bergen and were influenced, obviously, by impulses from Copenhagen (where the multitalented Sigurður Guðmundsson, painter, costume designer and national activist, had often visited the theatre). In 1908 the Reykjavík Theatre Company produced the first work of Jóhann Sigurjónsson, who would later reach an international audience with his Eyvind of the Mountains (1911) and Loftur the Magician (1914). In Helsinki, a long-struggling Finnish Theatre Company successfully performed Ibsen’s ‘A Doll’s House’ in Finnish, and from the 1890s it staged Kalevala-themed plays to increasing public response; it moved to a newly built National Theatre (designed in national-Romantic style) in 1905.39 A Dublin reverberation also reached the budding Galician movement in Spain, where a Brotherhood of Friends of the Language was founded in 1916 in obvious imitation of the Gaelic League; their founder Antón Villar Ponte translated the most nationalistic of Yeats’s plays, Cathleen Ní Houlihan (a historical allegory set in a peasant cottage), into Galician in 1921.40