Introduction

The regulation of online speech is not merely a technical matter – it is a normative and political one. Hate speech in particular has become a pressing concern in the digital age, necessitating not only scalable detection mechanisms but also critical reflection on how such content is governed, regulated, and contested within broader democratic frameworks. Regarding the ability to identify such content on a large scale, recent advancements in Natural Language Processing (NLP), especially the rapid progress in the area of Large Language Models (LLMs), present new opportunities for addressing this issue and efficiently (Kotarcic et al. Reference Kotarcic, Hangartner, Gilardi, Kurer, Donnay, Goldberg, Kozareva and Zhang2022; Parker and Ruths Reference Parker and Ruths2023). These models have demonstrated significant zero-shot capabilities across various NLP tasks, highlighting their potential utility in flagging online harmful content at scale (Gilardi et al. Reference Gilardi, Alizadeh and Kubli2023; Kasneci et al. Reference Kasneci, Seßler, Küchemann, Bannert, Dementieva, Fischer, Gasser, Groh, Günnemann and Hüllermeier2023). Yet, reliably detecting hate speech and other harmful online content using automated approaches remains challenging.

Hate speech refers to toxic (that is, abusive, pejorative, or otherwise harmful) content that targets individuals as representatives of (protected) groups (United Nations 2020, 8). This definition situates hate speech within the broader category of harmful speech, distinguishing it from toxic speech that is offensive but lacks group-based targeting. We refer to speech that is neither hate speech nor toxic as non-harmful. Hateful statements may be (intentionally) ambivalent or subtle, and there is typically no reliable ground-truth for what constitutes offending content. Moreover, pre-trained LLMs may carry, and even exacerbate, systemic biases, driven by the characteristics of the datasets they were trained on (Ferrara Reference Ferrara2023; Kasneci et al. Reference Kasneci, Seßler, Küchemann, Bannert, Dementieva, Fischer, Gasser, Groh, Günnemann and Hüllermeier2023; Ray Reference Ray2023; Shaikh et al. Reference Shaikh, Zhang, Held, Bernstein and Yang2022). A domain-specific model fine-tuned for the task of detecting hate speech and sensitive to the particular context can help address these issues and improve model performance, even with a small number of annotations (Fui-Hoon Nah et al. Reference Fui-Hoon Nah, Zheng, Cai, Siau and Chen2023; Kasneci et al. Reference Kasneci, Seßler, Küchemann, Bannert, Dementieva, Fischer, Gasser, Groh, Günnemann and Hüllermeier2023; Kocoń et al. Reference Koco, Cichecki, Kaszyca, Kochanek, Szydło, Baran, Bielaniewicz, Gruza, Janz and Kanclerz2023). In this paper, we contribute to these efforts by fine-tuning GPT-4o-mini on a diverse corpus of online comments in German, each annotated by coders from five groups with varying annotation quality: research assistants, activists, two kinds of crowd workers, and citizen scientists. With expert annotations as the gold standard for what constitutes hate speech, we study how the performance of fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini varies, relative to the zero-shot model, depending on the quality of the annotations used for fine-tuning.

We first demonstrate that annotation quality for what constitutes hate speech notably differs across our annotator groups. This includes significant variation in inter-coder agreement across groups. In addition, the agreement of different groups with the expert-based gold standard varies strongly between the best-performing group, trained research assistants, and the worst-performing group, citizen scientists. These differences in annotation quality then directly influence whether the performance of the LLM can actually be improved through fine-tuning or not. Specifically, we identify two key characteristics that set high-quality fine-tuning data apart.

First, only when using annotations from groups with a balanced ability to recover the gold standard, ie with relatively similar precision and recall, does fine-tuning enhance or at least match the zero-shot performance of GPT-4o-mini. Second, and most importantly, we find that only fine-tuning with data from groups that are better than zero-shot GPT-4o-mini at recognizing hate speech actually boosts classification performance. Specifically, fine-tuning using the highest-quality annotator group – trained research assistants – noticeably improves classification performance compared to zero-shot GPT-4o-mini by increasing precision without sacrificing recall. In practice, deciding when harmful content is targeted or not can be difficult even for well-trained experts. In all of our analyses, we therefore first consider harmful vs. non-harmful speech more broadly, and then treat hate speech (targeted attacks) and toxic speech (non-targeted attacks) as distinct forms of harmful speech. Our findings hold across both specifications.

Taken together, our results underscore the nuanced impact of data quality when fine-tuning LLMs to enhance hate speech detection. We demonstrate both that GPT-4o-mini performance can be noticeably improved by fine-tuning using only a small number of labeled data and that the quality of annotations is crucial. Fine-tuning helps when human coders perform better than zero-shot GPT-4o-mini, but it has no impact or may even hurt classification performance otherwise. In line with the emerging literature on supervised fine-tuning of LLMs for real-world classification tasks (Alizadeh et al. Reference Alizadeh, Kubli, Samei, Dehghani, Zahedivafa, Bermeo, Korobeynikova and Gilardi2025; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Zhang, Fu, Zhao and Wu2023), this finding suggests a move away from sheer quantity of labels to focusing on their quality instead. While data quality is a known concern in practice and has been widely acknowledged in the informal literature, there is to date a dearth of systematic evaluations of its impact. Our insights into what exactly constitutes ‘high-quality’ data and how this then translates to the performance of fine-tuned LLMs are, therefore, not only methodologically highly relevant but also have direct implications for their real-world application.

Enhancing the quality and precision of detection is a critical prerequisite for any kind of intervention that aims to manage the harms of online discourse, acknowledging that such interventions are inherently political and shaped by contested norms and power relations. The development of task-specific and context-sensitive machine learning classifiers for hate speech detection demands significant time, funding, and computing resources, along with extensive training data (Laurer et al. Reference Laurer, van Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2024). In contrast, LLMs can be rapidly deployed and efficiently fine-tuned to achieve excellent classification performance, as long as comparably small but high-quality datasets are used. Given the small size of datasets needed for fine-tuning, it is feasible to rely on the comparably more costly annotations from trained research assistants to enable the fine-tuning of LLMs for complex classification tasks. Crowd work annotations, in comparison, are more affordable but, as we demonstrate, not of sufficient quality to boost classification performance through fine-tuning. Similarly, labels from volunteer contributors, such as citizen scientists or NGO activists, are also of insufficient quality.

While the primary aim of this study is to improve hate speech detection through fine-tuning LLMs, we also seek to draw broader insights into fine-tuning methodologies for tasks characterized by ambiguity and subjectivity. Hate speech, as a socially and politically constructed category, resists fixed definitions, making it an ideal case to examine how fine-tuning with varied annotation quality influences model performance. By empirically analyzing how different types of human judgment affect the fine-tuning of LLMs, we provide practical guidance for using machine learning in settings where contextual sensitivity is essential. In doing so, we also contribute to ongoing debates about the societal implications of automated content moderation and the role of human judgment in shaping its outcomes.

Concepts, data, and methods

Conceptual foundations

The term ‘hate speech’ is inherently contested (Gagliardone et al. Reference Gagliardone, Gal, Alves and Martínez2015). Philosophical work treats hate speech not merely as offensive talk but as a practice that undermines equal civic standing (Waldron Reference Waldron2014). From a speech-act angle, certain forms of speech can subordinate targets by enacting social hierarchies rather than just describing them (Langton Reference Langton1993). This insight can be refined by distinguishing constitutive harms (the very act of denigration) from consequential harms (downstream violence or exclusion) (Maitra and McGowan Reference Maitra, McGowan, Maitra and McGowan2012). Together, these strands motivate treating hate speech as harmful in itself, even when no immediate violent outcome occurs. Building on these accounts, and consistent with the United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech (United Nations 2020), we define hate speech as any communication that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a protected characteristic.

Operationalizing hate speech

Distinguishing between hate speech targeting individuals as representatives of (protected) groups and non-targeted toxic speech is conceptually important but can in practice be very challenging, even for highly trained expert coders. Following Kotarcic et al. (Reference Kotarcic, Hangartner, Gilardi, Kurer, Donnay, Goldberg, Kozareva and Zhang2022), we use a two-step coding protocol designed to make this distinction as explicit as possible. The protocol is used for all groups and our expert annotators, but also in the LLM-based classifications. In the first step, the protocol distinguishes non-harmful speech from harmful speech. In the second step, it then distinguishes within the broader category of harmful speech between targeted hate speech and non-targeted toxic speech based on whether a target can be identified. The first step yields a broader (binary) distinction between harmful and non-harmful speech, whereas the first and second steps jointly produce a more fine-grained (multi-class) categorization in three categories (hate speech, toxic speech, and non-harmful speech). We consider the performance for both tasks separately throughout our analysis, allowing us to test how the complexity of the tasks (for annotators and the LLM) influences what can be achieved by fine-tuning.

Hate speech corpus

This study leverages a unique dataset of online comments in German encompassing a diverse set of hateful and non-hateful content. The comments stem from the German-language editions of two large Swiss newspapers that operate with relatively strict moderation guidelines. By collaborating directly with their community-management teams, we gained access not only to comments that were publicly visible, but also to entries the moderators had already hidden or deleted. The corpus covers a broad range of salient Swiss topics and inherently reflects the pluralistic nature of Swiss politics. At the same time, the data remain culturally coherent: all comments are in German, share the same domestic legal constraints, and are produced under the outlets’ house rules.

Overall, the dataset includes annotations by 204 individuals across five distinct groups as follows: research assistants (3 people), crowd workers from AppenFootnote 1 (17 people) and ProlificFootnote 2 (53 people), individuals participating in a Citizen Science challenge (24 people), and a large group of activists in the volunteer community of a partner NGO (107 people). The selection of coder groups originated from a collaboration with the NGO.Footnote 3 While the activists’ contributions were relevant for understanding how motivated, non-professional annotators perform, their annotations proved insufficient for our research needs, prompting the inclusion of alternative groups with varying levels of training and experience.

Each comment in our data was independently annotated by at least three individual coders from each group. Given the lack of an objective ground truth, three experts, all co-authors of this paper, annotated a gold standard set in line with the hate speech definition adopted in this paper. One of the three experts has longstanding experience with marginalized groups, allowing for a more balanced annotation of the ground truth dataset. In this step, the experts first labeled each comment independently. The initial labels assigned by the experts agreed for close to 80% of comments (Krippendorff’s alpha: 0.728). For the remaining 20%, the experts deliberated until they reached full consensus on each comment.Footnote 4 The harmonized labels attained from this procedure were employed as the study’s gold standard. Even so, it is important to note that hate speech annotations are inherently subjective and that there is no such thing as an absolute ground truth.

Our initial corpus consisted of 500 unique user-produced comments obtained from the discussion section of collaborating Swiss national media outlets and included published, moderated, and deleted comments (Kotarcic et al. Reference Kotarcic, Hangartner, Gilardi, Kurer, Donnay, Goldberg, Kozareva and Zhang2022). The comments were posted under more than 60 different news articles spanning a broad range of topics, including COVID-19, international politics, current affairs, local news, sports, and lifestyle. Most comments are rather short, fully formulated sentences. They may include emojis, but no other visual content. Because of platform settings, six comments could not be consistently annotated across all groups, resulting in a total of 494 unique comments for analysis. To ensure consistency across annotator groups, we randomly sampled three annotations per comment for groups where some comments were annotated more than three times (notably Appen and the NGO), preserving the per-comment distribution of positive and negative labels. Finally, within each group, we determined a single label for each comment using majority rule, ie the majority label selected by at least two of three coders within each group.

Annotation quality of human coders

When quantifying the variation in annotation quality among our human coders, we use standard metrics to both measure inter-coder agreement and the quality of annotations relative to the expert-based gold-standard labels. Specifically, we rely on Krippendorff’s alpha to evaluate the level of consistency among multiple annotators when assigning labels to the same data set (Barberá et al. Reference Barberá, Boydstun, Linn, McMahon and Nagler2021; Van Atteveldt et al. Reference Van Atteveldt, Van der Velden and Boukes2021). In assessing consistency, we consider the binary (harmful speech vs. non-harmful speech, bin) and the multi-class (hate speech vs. toxic speech vs. non-harmful speech, multi) distinctions. The two most consistent groups of coders are the trained research assistants (

![]() ${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.506$

,

${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.506$

,

![]() ${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.435$

) and NGO activists (

${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.435$

) and NGO activists (

![]() ${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.458$

,

${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.458$

,

![]() ${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.433$

). Crowd workers from Prolific (

${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.433$

). Crowd workers from Prolific (

![]() ${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.391$

,

${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.391$

,

![]() ${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.391$

) and the citizen scientists (

${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.391$

) and the citizen scientists (

![]() ${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.335$

,

${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.335$

,

![]() ${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.308$

) are both less consistent. The by far lowest level of inter-coder agreement is found for crowd workers from Appen (

${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.308$

) are both less consistent. The by far lowest level of inter-coder agreement is found for crowd workers from Appen (

![]() ${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.080$

,

${\alpha _{bin}} = 0.080$

,

![]() ${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.129$

). The overall relatively low inter-coder agreement within all groups is in line with existing literature, emphasizing the inherent challenges in achieving consensus among annotators for subjective tasks like hate speech detection (Akhtar et al. Reference Akhtar, Basile and Patti2020; Kralj Novak et al. Reference Kralj Novak, Scantamburlo, Pelicon, Cinelli, Mozeti and Zollo2022).

${\alpha _{multi}} = 0.129$

). The overall relatively low inter-coder agreement within all groups is in line with existing literature, emphasizing the inherent challenges in achieving consensus among annotators for subjective tasks like hate speech detection (Akhtar et al. Reference Akhtar, Basile and Patti2020; Kralj Novak et al. Reference Kralj Novak, Scantamburlo, Pelicon, Cinelli, Mozeti and Zollo2022).

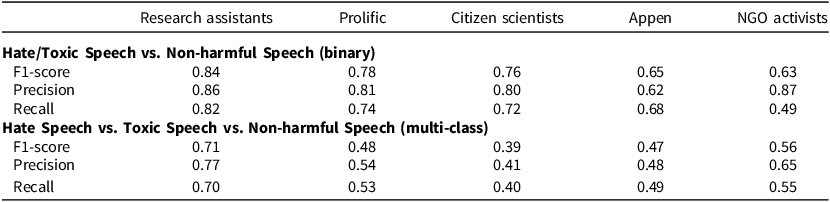

Evaluating the annotation quality for each group relative to the expert-based gold standard, we rely on three standard measures commonly used for quantifying annotation and classification performance: precision, recall, and F1 scores.Footnote 5 Taken together, these metrics provide a comprehensive picture of annotation quality, reflecting the reliability in identifying true instances of hate speech (precision), the ability to capture all such instances (recall), and the respective trade-offs (F1). Coding conducted by research assistants has the highest quality, coming closest to the gold-standard labels for the binary and multi-class annotations (Table 1). Crowd workers from Prolific follow in quality, but their annotations are significantly less accurate when distinguishing between (targeted) hate speech, (non-targeted) toxic speech, and non-harmful content.

Table 1. Comparison of annotation quality across various coder groups

Note: All annotation quality measures are calculated relative to the expert-based gold-standard hate speech labels.

Interestingly, annotations by NGO activists achieve the highest precision in recovering the gold-standard labels for the harmful vs. non-harmful speech distinction, but also the lowest recall. That is, they most accurately identify instances of harmful speech but fail to capture many of them. This suggests a solid understanding of the nuances of coding harmful content, which is also evident in the hate speech vs. toxic speech distinction, where they outperform Prolific crowd workers in precision and recall.Footnote 6 Quality drops notably in the other two groups. Citizen scientists perform well in distinguishing harmful from non-harmful speech but struggle to separately distinguish (targeted) hate speech and (non-targeted) toxic speech from non-harmful speech. Meanwhile, Appen crowd workers perform significantly worse than research assistants on both tasks.

Taken together, the comparisons among coders and the level of agreement with the gold-standard labels demonstrate that our different annotator groups produced labels of significantly different quality. This is crucial in evaluating the impact of data quality on the fine-tuning of LLMs.

Fine-tuning GPT-4o-mini

A key strength of LLMs is that by virtue of their pre-training on huge amounts of data, they already perform well on a wide range of tasks without additional training (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Mann, Ryder, Subbiah, Kaplan, Dhariwal, Neelakantan, Shyam, Sastry and Askell2020; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Yuan, Fu, Jiang, Hayashi and Neubig2023). At the same time, the broad scope of the models typically implies a lack of context- and domain-specificity (Au Yeung et al. Reference Au Yeung, Kraljevic, Luintel, Balston, Idowu, Dobson and Teo2023; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Tan, Lu, Thirunavukarasu, Ting and Liu2023). Fine-tuning here offers a way to fully leverage the strength of a broad pre-trained model while enhancing performance with specific nuances or domain-specific knowledge (Ouyang et al. Reference Ouyang, Wu, Jiang, Almeida, Wainwright, Mishkin, Zhang, Agarwal, Slama, Ray, Schulman, Hilton, Kelton, Miller, Simens, Askell, Welinder, Christiano, Leike, Lowe, Koyejo, Mohamed, Agarwal, Belgrave, Cho and Oh2022; Wei et al. Reference Wei, Bosma, Zhao, Guu, Yu, Lester, Du, Dai and Le2022). On a technical level, fine-tuning adjusts a subset of the model’s weight parameters based on additional data with task-specific labels (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Wang, Lan, Xu, Lim, Bing, Xu, Poria, Lee, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023). In particular, for tasks such as hate speech detection, which are intrinsically complex and subjective, fine-tuning also explicitly brings human perspectives into the loop. As a result, fine-tuning not only improves model performance but also addresses concerns regarding model-induced biases, which can be especially critical for tasks such as hate speech detection (Kasneci et al. Reference Kasneci, Seßler, Küchemann, Bannert, Dementieva, Fischer, Gasser, Groh, Günnemann and Hüllermeier2023).

We use GPT-4o-mini with the standard temperature setting (Gilardi et al. Reference Gilardi, Alizadeh and Kubli2023).Footnote 7 The model is prompted to classify a text input without any task-specific fine-tuning. It uses its general understanding of language and context, acquired from pre-training, to decide on the classification category. For more details on the classification, see Appendix 1. Fine-tuning of the model was then implemented on OpenAI’s GPT-4o-mini architecture by using the openly available API.Footnote 8 Next to the model’s zero-shot performance, ie the base GPT-4o-mini model performance without fine-tuning, we tested two different fine-tuning regimes: one using 100, the other 250 comments. We used the same two random sets of comments across all groups, assigning to each comment the respective group-specific (majority) label obtained from the annotations.

To quantify the hate speech classification performance of GPT-4o-mini, we rely on the same gold standard and same standard metrics introduced above: precision, recall, and F1. We also report confidence intervals obtained through bootstrapping as a measure of the robustness of the model’s classification performance.

Results

The main findings are displayed in two figures. Figure 1 shows the performance of the different annotator groups, zero-shot GPT-4o-mini, and fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini for the binary harmful vs. non-harmful classification task, while Figure 2 does the same for the multi-class distinction between hate speech, toxic speech, and non-harmful speech. Our discussion focuses first on the zero-shot performance of GPT-4o-mini, and then on the performance of the fine-tuned model.

Figure 1. F1, precision, and recall of the fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini for binary classification of harmful vs. non-harmful speech across annotator groups, using 100 or 250 training labels. Performance is shown relative to the expert gold standard; vertical lines mark zero-shot performance. Green bars indicate label quality. Error bars show 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Average F1, precision, and recall of the fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini for classifying hate, toxic, and non-harmful speech across annotator groups, using 100 or 250 training labels. Performance is shown relative to the expert gold standard, alongside the label quality per group. Error bars indicate 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Zero-shot classification

The baseline performance of zero-shot GPT-4o-mini varies significantly between the broader harmful speech detection task and the narrower hate speech detection task. Even without prior task-specific training, it performs quite well on the binary harmful vs. non-harmful speech distinction (vertical lines in Figure 1). With an F1 score of 0.79, it matches or outperforms all human annotator groups when compared to the expert-based gold standard, except for the trained research assistants, who achieve an F1 score of 0.84. However, its performance declines in the multi-class classification task, which further distinguishes (targeted) hate speech from (non-targeted) toxic speech within harmful speech (vertical lines in Figure 2). Here, its F1 score of 0.65 still surpasses all human annotator groups except the trained research assistants (F1: 0.71).

The GPT-4o-mini zero-shot model exhibits a stark imbalance between precision (0.68) and recall (0.95) for the broader harmful vs. non-harmful speech distinction but not for the narrower hate speech detection task (precision: 0.67, recall: 0.68). In other words, its higher zero-shot performance in the broader task is driven entirely by its significantly higher recall. Specifically, the model correctly predicts harmful speech in 226 out of 238 instances, missing only 12 cases. However, this comes at the cost of a high number of false positives – 106 out of 332 predicted harmful speech instances are incorrect, which is consistent with its relatively low precision. In contrast, for the narrower hate speech detection task, the model captures true instances of hate speech (83 out of 148) and toxic speech (78 out of 94) reasonably well but frequently misclassifies non-harmful speech as either toxic or hate speech. This explains its relatively low precision and recall for this task (see Appendix 4.1).

Using classifiers with low precision can be problematic in real-world applications, as it may lead to a high rate of (over-)moderation, flagging comments that are not actually hate speech (or more broadly, harmful speech). Human annotator groups tend to have lower recall but higher precision, particularly in distinguishing between harmful and non-harmful speech, resulting in a more balanced annotation quality overall. This suggests that fine-tuning GPT-4o-mini with human labels should improve precision, ideally without a significant loss in recall. For the narrower hate speech detection task, we also expect fine-tuning to enhance performance, but only with annotations from research assistants – the only group whose labels are of sufficiently high quality to improve precision. In practice, this means a model fine-tuned on high-quality data should maintain its ability to identify relevant instances of hate (or harmful) speech while reducing instances of over-moderation.

Fine-tuned model

The fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini model demonstrates a clear improvement in performance compared to the zero-shot model for the broader harmful speech and the narrower hate speech classification tasks (horizontal bars in Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 9 The best-performing models enhance GPT-4o-mini’s performance by up to five percentage points, particularly when fine-tuned with 250 labels (violet bars), achieving F1 scores of up to 0.83 for harmful vs. non-harmful speech and 0.71 for hate speech detection. These gains stem primarily from notable improvements in precision compared to the zero-shot model. The only consistently reliable annotation set for fine-tuning comes from the trained research assistants, who provide the highest annotation quality across groups. Notably, GPT-4o-mini does not seem to absorb much noise from the citizen science fine-tuning set, as indicated by minimal deviation from its zero-shot performance. This suggests that the model is relatively resistant to lower-quality annotations, likely because of its strong pre-trained decision boundaries.

A detailed analysis of model performance reveals that the overall improvement across both tasks is primarily driven by a reduction in false positive classifications in the fine-tuned model, without a corresponding increase in false negatives or a decrease in true positivesFootnote 10 . The best-performing fine-tuned model closely matches the highest human annotation quality in both classification settings. For the broader harmful vs. non-harmful speech distinction, precision and recall are significantly more balanced in the fine-tuned model compared to the zero-shot GPT-4o-mini, indicating a more robust classifier. We also observe a notable precision gain when fine-tuning with lower-quality annotations, such as those from NGOs, which tend to have high precision but low recall. However, this comes at the cost of reduced recall, leading to an overall decrease in F1-score and less robust performance than the zero-shot model.

While it may seem intuitive in hindsight that LLM fine-tuning is sensitive to differences in annotation quality, we did not anticipate the extent of this sensitivity, particularly given the strong performance of LLMs in zero-shot settings. Our study contributes to ongoing discussions on the usage of LLMs for text annotation by providing empirical evidence that annotation quality significantly influences fine-tuning outcomes. At the same time, we demonstrate that the differences in model performance are primarily attributable to the quality of the annotations provided by each group, particularly the balance between precision and recall. We expect these insights to hold in other language contexts. Taken together, the results underscore that in our context, with Swiss news sites that enforce comparatively strict ex-ante and ex-post moderation, fine-tuning with expert labels can make LLMs viable for assisted moderation pipelines, while scaling up with inexpensive crowd labels risks either over-blocking speech or under-detecting subtle hostility. The unique Swiss variation of German included in our study provides evidence of the fine-tuned model’s ability to handle linguistic nuances, suggesting that similar performance might be observed in other languages with regional variations.

Conclusion

Efforts to address online hate speech and safeguard democratic discourse depend not only on scalable detection capacities but also on navigating the political and normative decisions that shape what is considered harmful, who decides, and how such speech is governed in pluralistic societies. Focusing on detection, this paper demonstrates the potential of fine-tuned, context- and task-specific LLMs to improve the identification of hate speech. However, as our study shows, the quality of fine-tuning data is crucial for the ability of LLMs like GPT-4o-mini to classify hate speech effectively. Simply fine-tuning with any data does not guarantee improved performance. In fact, we show that using low-quality annotations for fine-tuning can even degrade the model’s zero-shot performance. Only high-quality data that appropriately balances the precision-recall trade-off leads to a meaningful boost in classification performance, regardless of coder group size.

A crucial aspect of NLP approaches, for hate speech detection and similar tasks, is the substantial number of annotations required to train context-specific classifiers (Barberá et al. Reference Barberá, Boydstun, Linn, McMahon and Nagler2021; Benoit et al. Reference Benoit, Conway, Lauderdale, Laver and Mikhaylov2016; Boukes et al. Reference Boukes, Van de Velde, Araujo and Vliegenthart2020; Laurer et al. Reference Laurer, van Atteveldt, Casas and Welbers2024; Van Atteveldt et al. Reference Van Atteveldt, Van der Velden and Boukes2021). The use of fine-tuned LLMs offers a shift away from relying solely on large quantities of labels, instead emphasizing fewer but higher-quality annotations. Our results suggest that high-quality human labels will remain essential for achieving the task- and context-sensitivity needed for LLMs to match high-quality human annotators’ classification performance. As we demonstrate, this is reasonably achievable in practice: the amount of high-quality data required is small and can be generated at a reasonable cost and effort by trained research assistants to effectively enhance the model’s performance.

We acknowledge that our approach, which relies on proprietary models, has certain limitations, particularly with respect to reproducibility and transparency, as well as data protection (Barrie et al. Reference Barrie, Palmer and Spirling2024; Ollion et al. Reference Ollion, Shen, Macanovic and Chatelain2024; Spirling Reference Spirling2023). However, recent work has demonstrated that open-source models can achieve similar or even superior performance, offering a way to address these limitations (Alizadeh et al. Reference Alizadeh, Kubli, Samei, Dehghani, Zahedivafa, Bermeo, Korobeynikova and Gilardi2025). Therefore, although our study uses proprietary models, there are compelling reasons to believe that the findings generalize to LLMs that are better aligned with reproducibility, transparency, and data protection.

Fine-tuned LLMs have important real-world applications beyond hate speech detection. For instance, an emerging body of research explores the role of supervised fine-tuning in facilitating content moderation decisions more broadly (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Zhang, Fu, Zhao and Wu2023). As with hate speech detection, this approach integrates LLMs with high-quality labels provided by human moderators. This hybrid model leverages the strengths of both LLMs and human judgment, potentially enabling more accurate, fair, and nuanced content moderation at scale. However, further research is needed to establish clear guidelines and frameworks for the use of LLMs in content moderation.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100546

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available at the Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/U9ODTE).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Public Discourse Foundation, whose StopHateSpeech campaign inspired this project. We would also like to thank Citizen Science Zurich and the different groups of volunteers who contributed their time to this project.

Funding statement

We gratefully acknowledge funding by InnoSuisse (Grant 46165.1 IP-SBM) and the Swiss Federal Office of Communications.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.