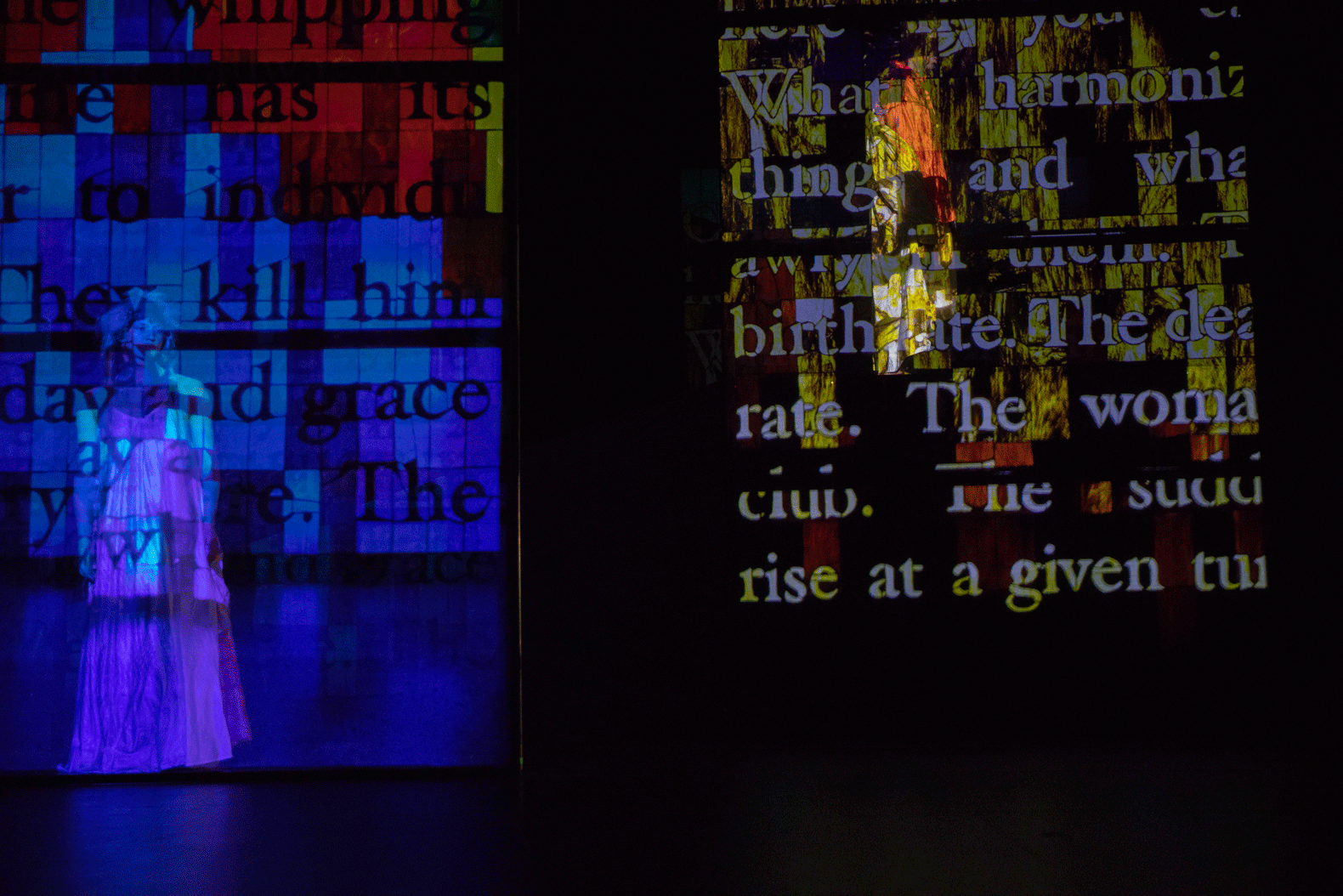

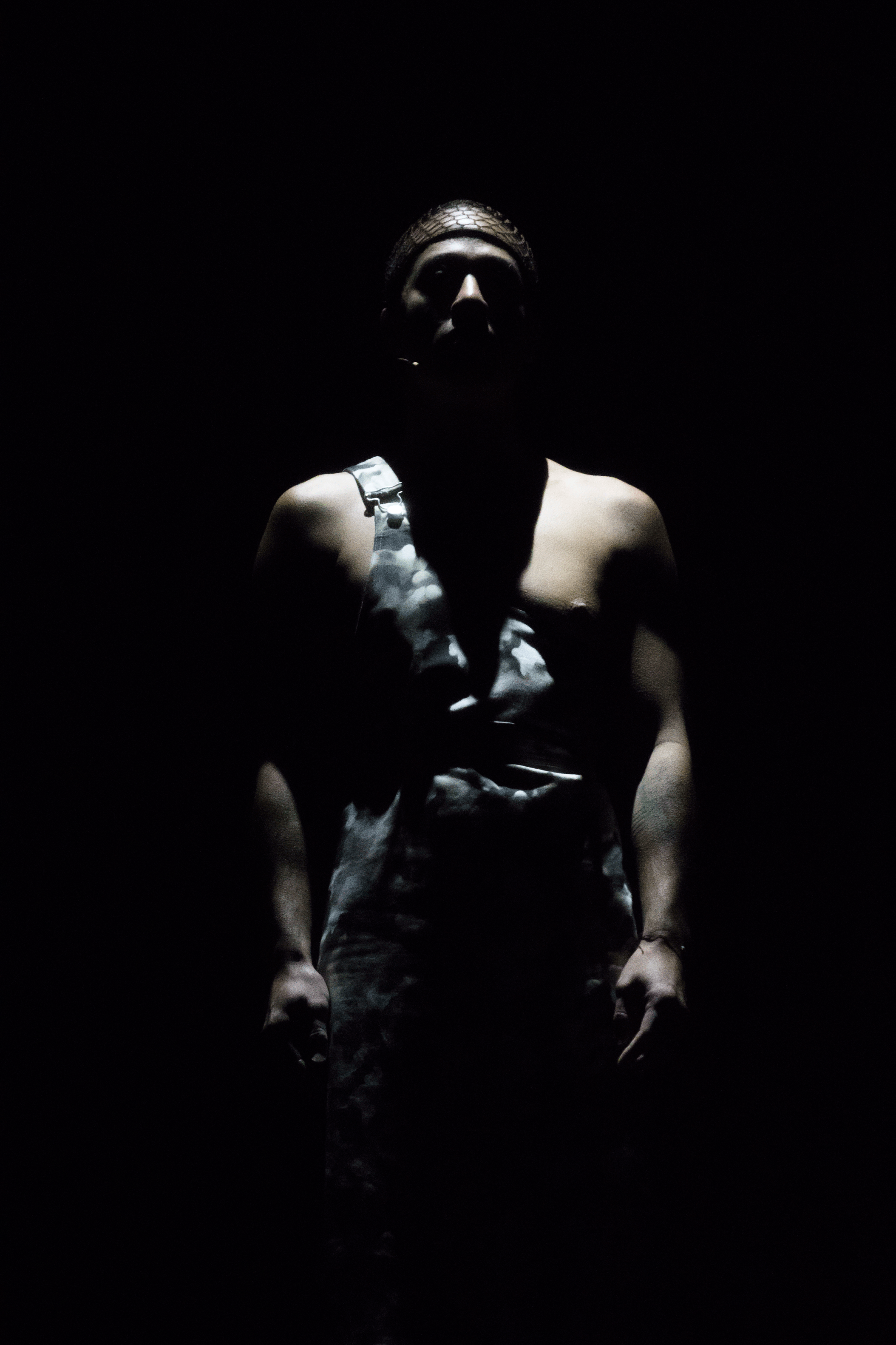

Figure 1. Apparitions (boychild) behind projection in Sudden Rise, directed by Moved by the Motion, Wu Tsang, and boychild. Schauspielhaus Zürich, 2019. (Photo by Ketty Bertossi)

The lecturer approaches the audience and, before returning to her assigned position, says, in an excited voice:

I’m late, a little bit, palpitating. Un-ironed. Radical inability properly to present myself. Disrespectable because it purports to be all, you know, um… Well whatever, that’s beside the point. Um, although it might appear to be that one would need to explain why. And I’m just thinking about…the detail. Well, if you look at ’em for a minute you see that they’re moving. Dark underneath and light on top. One just kinda rolling over the mountain. (Moten and Tsang Reference Moten and Tsang2016:1)

Given the current rapidly changing world and political situation, the search for relevant and “futurable” forms of theatre that can reflect the radical nature of these changes and challenges is more urgent than ever. The pressing issues—climate catastrophe, wars, and the abuse of political power—catapult the theatre arts beyond their traditional boundaries toward interdisciplinarity as well as the interaction of theory and practice. The performance Sudden Rise (2019) by the Chinese American performance and video artist Wu Tsang and the collective Moved by the Motion—comprising performers Josh Johnson and Tosh Basco alias boychild, cellist Patrick Belaga, sound artist Asma Maroof, and others (see Richman Reference Richman2022)Footnote 1 —is an example of futurable theatre. The first section of Sudden Rise offers an opportunity to focus on the self-referential and transgressive features of the work that justify calling it a posthuman theatre paradigm. In his article in this issue of TDR, Frithwin Wagner-Lippok presents another phenomenological approach to Sudden Rise and asks how this transgression opens up a postsubjective field of theatricality through this transgression and can thus be understood as a Ricoeurian metaphor for the paradox of theatrical form. He also examines the working method of Wu Tsang’s team in this context (see Wagner-Lippok Reference Wagner-Lippok2025).Footnote 2 Although both of our essays are based on what is experienced in Sudden Rise, we use different theories in our analyses of the work.Footnote 3

Moved by the Motion is a performance group of interdisciplinary artists, founded in 2013 by Wu Tsang and boychild. The “band,” as it is perceived by the members, combines media such as language, movement, image, and sound. Membership is fluid; at various times, eight to ten people have felt they belonged to the group. Tsang’s first feature-length documentary, Wildness (2012), portrayed the historical Latin/LGBT nightclub Silver Platter in Los Angeles, where she met boychild, Asma Maroof, and Patrick Belaga as well as Josh Johnson and poet, scholar, and philosopher Fred Moten. Their roots are in the New York and Los Angeles house music, drag, and dance scene. Directly related to Sudden Rise was Tsang’s exhibition There is no nonviolent way to look at somebody (2019) at the Gropius Bau, Berlin, which addresses the violence between seeing and being seen.

Sudden Rise begins in complete darkness, after the theatre’s auditorium lights have gone out and two musicians (Patrick Belaga and Asma Maroof) have taken their places behind the cello and keyboard at the end of the entrance to the front right of the stage. For more than two minutes, the darkness is filled by a chromatic minor scale played on a cello. Then, something surprising happens. Instead of an eagerly awaited live event, images flicker across an upstage screen to the staccato rhythm of the electronically altered plucked cello: photographs of historical depictions that seem to be taken from a lexicon of cultural history in the style of d’Alembert and Diderot’s Encyclopédie, Renaissance drawings in the style of da Vinci, early scientific and technical representations, and so on. The barrage of images draws viewers into something like a narrative, a smorgasbord of historical testimonies from cultural history, interspersed with vanitas motifs such as photos of human skulls—for example, Albrecht Dürer’s master engraving Saint Jerome in His Study from 1514—superseded occasionally by portrait photos, well-known symbols (such as the Apple logo), landscapes, and short video clips. Familiar-seeming images appear between undecipherable icons, triggering for a fraction of a second recollections that might be verified only after the show using a video: the oil painting Adam and Eve by Lucas Cranach the Elder; the picture of a modern haystack; two anonymous pictures of Saint Moses the Black; a photograph of the moon, another of an indefinable hole in a wall or in the pavement; after some screen flickering, a sheet of music from which we might catch the title “Stolen Moments,”Footnote 4 soon followed by a book cover, Jamaica Labrish,Footnote 5 then a shocking mushroom cloud;Footnote 6 a jagged diagram of esophageal pressure over time with the title “Antral Manometry in Rumination Syndrome”; a half-second clip from Chaplin’s Modern Times; hands clawing at the bars of a prison window from the inside—which is actually a human eye with large dark eyelashes, not consciously perceived during the first viewing due to the short duration of the projection; an Escher drawing of an intertwined knot; a cargo steamer accident; several depictions of Baroque theatre scenes, one of which shows a horrified crowd recoiling from the wall fresco of a life-size skeleton (vanitas motifs repeatedly haunt the paintings and, as it were, thematize the entire sequence of pictures); and finally, a mysterious bar chart.

In the last third of this storm of icons, the reticent, anodyne voice of a figure who has appeared at the bottom left of the video, skimpily dressed in a colorful garment and dimly illuminated, makes the flurry of icons even more compelling. This microphone-amplified, slightly spherical-sounding, calm, gentle voice of a master accompanies the performance for long passages. Short clips of factory robots show calm mechanical movements that seem to coincide strikingly with the speech patterns of the performer.

Arrayed in a suggestive rhythm, the images and clips keep us busy seeking a pattern, a story behind them. We are sucked into the picture stream as if sitting in the cinema. The strange icons soon become a fictitious reality, and our objective and detached perception transforms as we become empathetically immersed in the picture flow. Yet we are not drawn into it by illusion; on the contrary, for instance, four times in succession, short projections of a wide body of water flowing towards us, which seems to fill the entire screen, are intercut with images of saints for about a quarter of a second each, creating a surreal contrast, “flashing” like a message; at another moment a big hand moves in front of a landscape with a forest and a meadow, as if wanting to move it around, showing that the landscape is a picture. The performance repeatedly reveals the means it is using to create the image. However, the flow of images is unpredictable, alienating us from it so that we perceive it as something uncontrollable, even chaotic. We want to recognize every single image and decipher what it could possibly mean, but we know we have to let them flash by, ignore them, let them be ephemeral. We feel torn between the hopeless activity of deciphering and the experience of ultimately succumbing to the flood. The richness of information and the rapidity and sheer number of projections facilitates this seductive yet unsettling experience. Physiologically overwhelmed, we become aware that we are no longer experiencing individual representations but the very process of being affected by them. The sequence of impressions becomes an experience of being seized by a sublime, albeit past reality, and of being astonished that we are so touched by it.

The initial surprise of the transition from darkness to the picture torrent and the subsequent change in our way of perceiving (from decoding the pictures to surrendering to the experience) make us suspect that we are trespassing outside known theatrical territory. Accustomed to searching for the meaning of what we see and hear, we wonder: What is this? An outlandish documentation? Some historico-cultural lecture? But comprehending this experience lies on another level. The unexpected, striking, and long-lasting sequence of images forces us to abandon the question of what we perceive in detail and instead ask about the how of the experience, i.e., to trace, while experiencing them, the subjective events that make up this “how.” In the course of the three-and-a-half-minute picture storm, a regularity becomes recognizable: the rhythm of the cellists and drummers playing live regularly lapses into rapid whirls whose staccato-like beat is followed precisely by the projections. Projections and soundtrack do not serve simply as atmospheric background but are contextualized twice as an image-sound structure—images appearing in a sound context and vice versa—and as a sensually experienced interplay of offer (the incoming stream of images and sounds) and interpretation (the viewer’s subjective associations and thoughts). “Interplay” here refers neither to an objective fact nor a subjective perception, but rather to an aesthetic fact, which as such cannot be reduced to psychology (perception) from a phenomenological perspective, but is ultimately to be accepted as an enigmatic entanglement of subjectivity and materiality. It can be understood as a dialog between us and the scenic events: an incarnation of a phenomenological theatre concept that conceives the performance as an intermediate phenomenon taking place neither in our subjective experience nor in the objective scenic events onstage, but, as an ongoing process, somewhere in between.Footnote 7 However, since this dialog is not initiated by the actors, but develops in their absence—as it were, in secret—between images and sounds on the one side and us on the other, it is simultaneously the manifestation of a non-dialog, an interpersonal void.

A small detail epitomizes this experience. The subjective expectation at the beginning, a kind of suspense that something significant will happen, is supported by the cello staccato that starts five seconds before the picture storm, producing two opposite effects: surprise on the symbolic level (images instead of actors) and a rhythmic concordance on the affective level (visual and acoustic changes). Since this surprise lies in the astonishing contradiction between expectation and experience, the intellectual affront and the affective harmony are united here in a single event. The break between anticipated and actual events is experienced rhythmically as a seamless, even logical development. As a result of this contradiction, I am struck by something that affects me from the outside, but at the same time is thwarted by its possible meaning from the inside. As my focus constantly crosses the boundary between objective rhythm and subjective expectation, I become aware not only of the contradictory simultaneity of what might be called affront and harmony, but also, on a more abstract level, of the paradoxical entanglement that brackets affect and meaning.

The performance doesn’t even disguise the trick. The rhythmic image-sound couplings accompany the whole image storm in such a way that its alienating effect is demonstrated. The performance abandons all pretense, renouncing mimesis and representation. By openly displaying—and playing with—the mechanism of the trick, it transcends itself as a representation of something external and instead re-fers to itself (in the original Latin sense of “to carry back”). By showing its mechanism, it makes itself perceivable as a show. This recursive transgression makes Sudden Rise an autoreferential system: it shows itself as a whole—and thus, paradoxically, stands outside itself—for the concept of “showing” implies a difference between that which shows and that which is shown; interpreted spatially, the one must be in a different place than the other. Something can indeed “refer” to itself, but as soon as it “shows” itself as a whole, it enters a logical abyss in which all identity dissolves. It crosses the demarcation line that makes it identical with itself. It remains the same and yet, by transgressing itself, expands at the same time. By harboring this paradox,Footnote 8 it embodies a logical crisis that brings about change through an internal contradiction. By demonstrating the making of the effect while producing it, the performance questions its formal prerequisites, detaching itself from its theatrical (representational or presentational) foundations and emerging as a new, self-generated phenomenon. We saw, on closer inspection, that the overwhelming of the senses turns out to be a conflict of affective and intellectual processes. The undisguised presentation of the aesthetic production of this conflict enables the paradoxical experience of a constantly transcending process. The question arises whether this autoreferential—self-questioning, self-transcending, and/or self-transgressing—attitude is specific to Sudden Rise or is an inherent part of theatre. Isn’t this kind of autoreferentiality implicit in the self-presentation of actors who appear behind their roles as persons? Isn’t this the well-known postdramatic strategy of revealing the work’s own theatricality?

Beyond Theatre

The Aesthetics of Autonomy

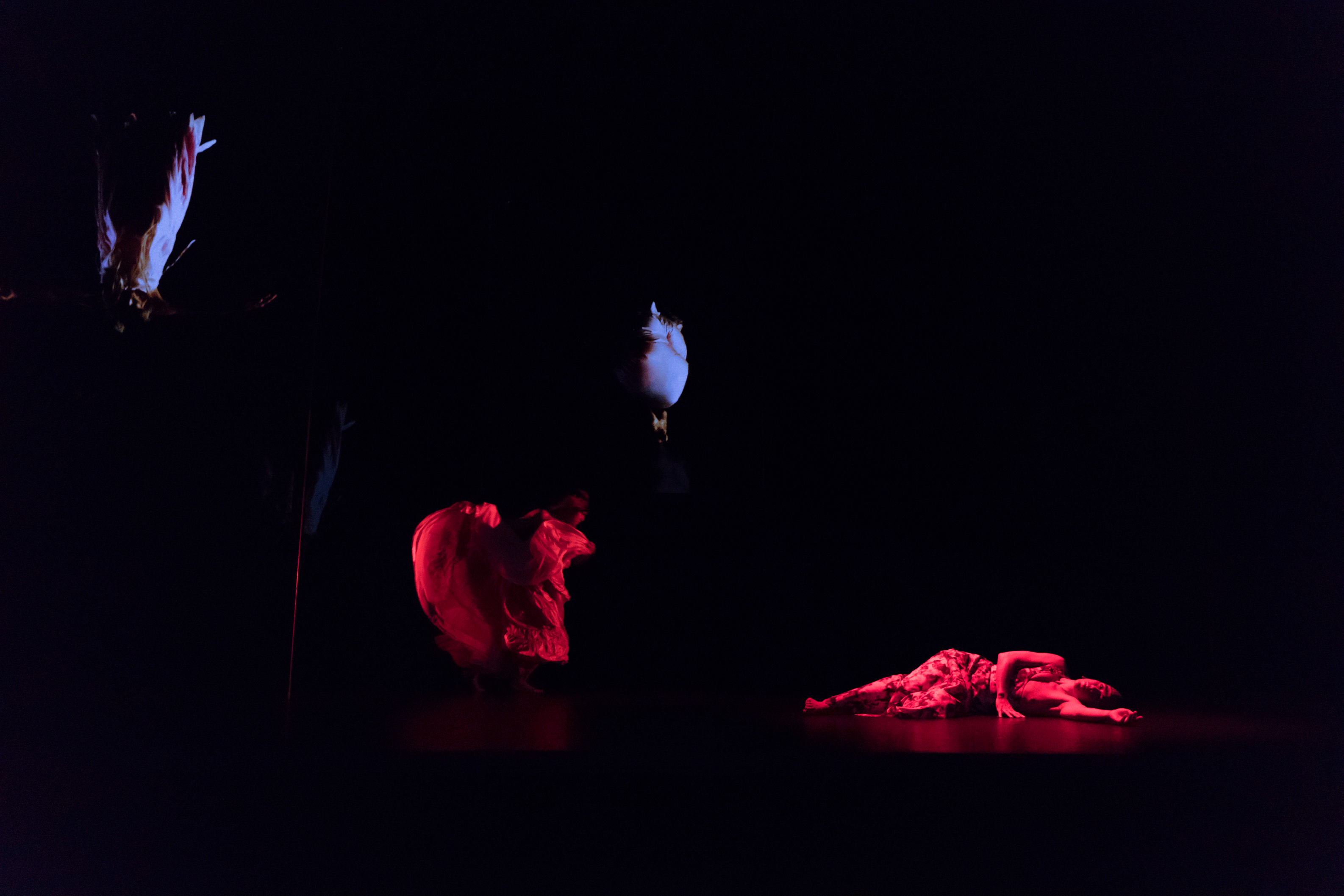

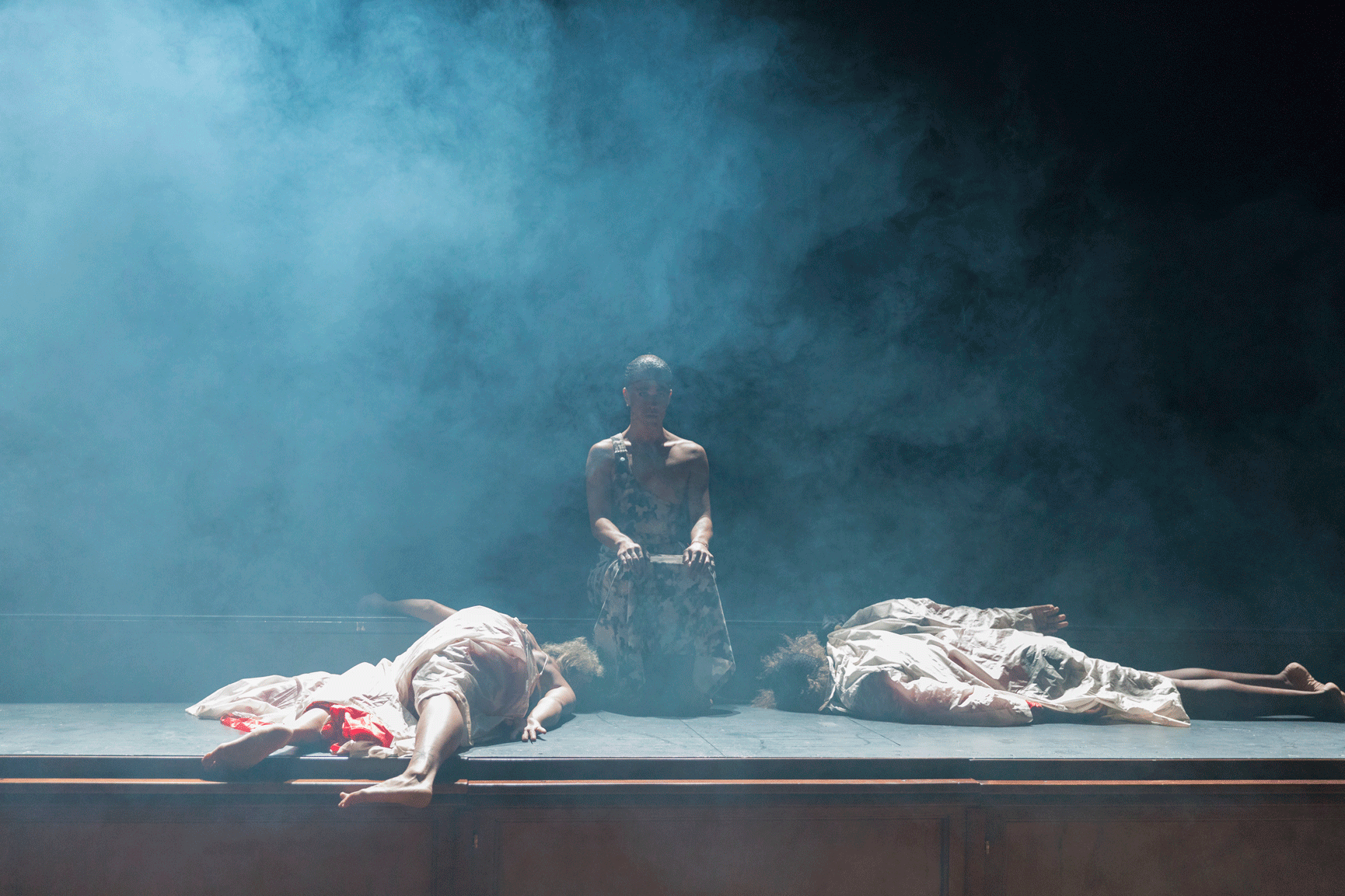

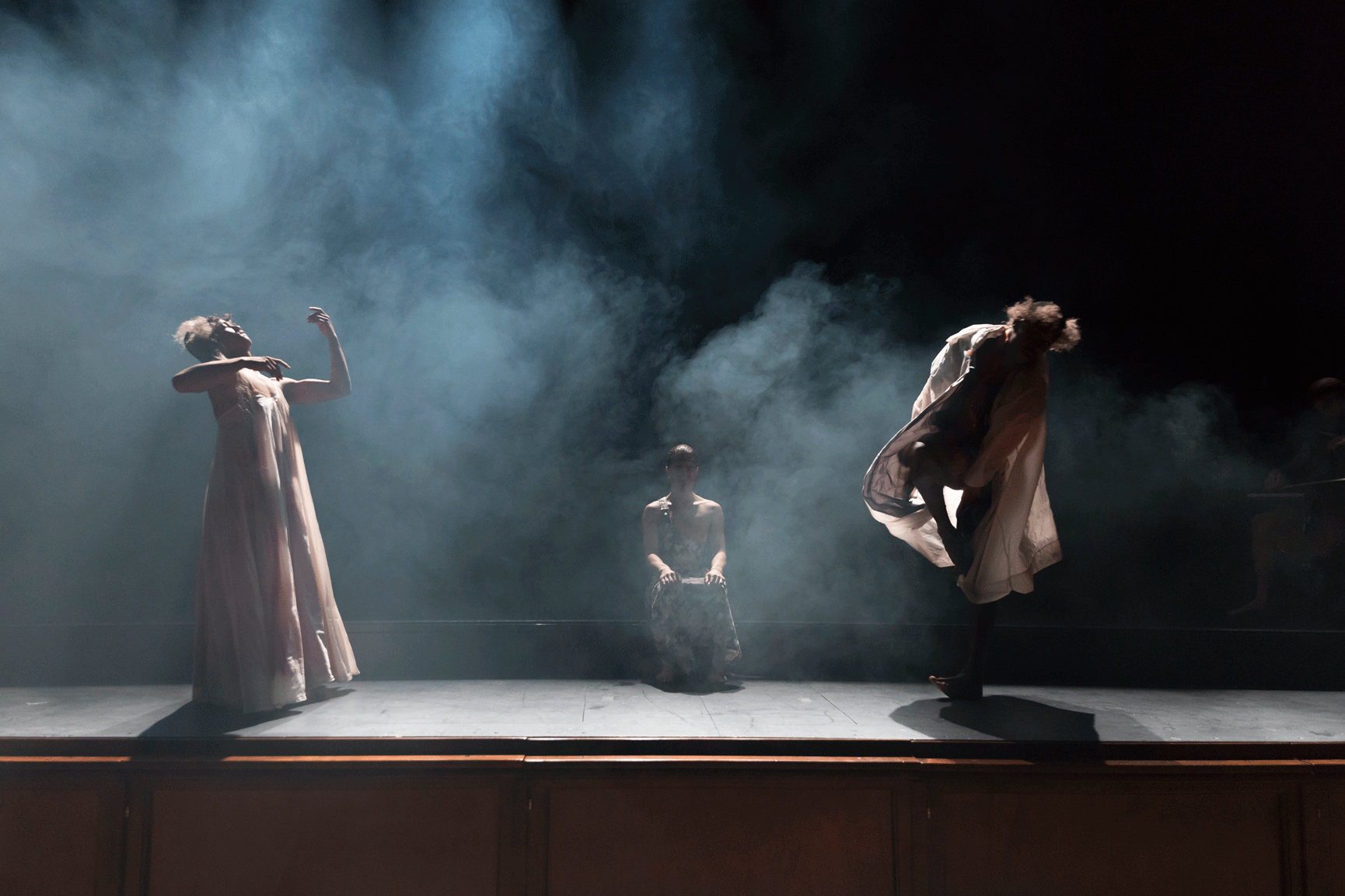

What is crucial, and different from most postdramatic theatre, is that Sudden Rise pushes self-transcendence beyond both character portrayal and presenting the self of the actor. In the careful synchronous interplay of image and sound, the performance is dissociated from any scenic action, any story. Nevertheless, it seems to point to something with urgency, going beyond merely playing out its own material. The flashing images from different categories and eras rivals any drama or self-portrayal in terms of tension and transcends the need for a scenario. The performance emancipates itself from its own theatricality. This emancipation is ostentatiously displayed in the astonishing staccato speed of the rushing images, which mocks any communication hitherto necessary for plot-driven theatre. The same effect is experienced further on in the performance when projections of fleeting figures cross real bodies dressed in long, flowing, monochrome robes, so that they convey less the impression of figures or individuals (which could still appeal to us, contact us)Footnote 9 than that of detached apparitions. When the gliding bodies, or, more precisely, the clothes they wear, appear lit like models in a fashion show, as the projected figures move slowly up and down, to the left or right, merging with each other in countless cross-fades—or when, instead of narrative actions, the bodies perform only the simplest movements, illuminated by pale blue-white or bright red light as they stride between digitized projections—this simultaneously realizes and destroys the immediate corporeality of theatre, especially in the absence of action or dialog, revealing the paradoxical intertwining of its material reality and unreality. What we see are fragile, vulnerable, erotic bodies of uncertain gender identity, moving without any apparent intention, and we don’t know if or in which way they exist before our eyes. Haphazardly, real and projected bodies seem to dance with each other, merge into each other, emerge from one another, and disappear again. By dispensing with a narrative, by blurring any distinction between male and female, between human protagonist (subject) and dancing body (object), even between material and projected figures, bodies and thoughts, flesh and garments, reality and imagination—in short, between aesthetic and existential categories—Sudden Rise is a reflexive performance-video-art hybrid that proposes a new, autonomous (anti)theatrical form in which humans only appear as mannequins, as carriers of clothes and movements.

The phenomenologically interesting point is that the experience that gave rise to my thesis is not the result of language, even though an endless flow of words delivered by Wu Tsang incessantly points to meanings and ironically produces allusions. The experience arises from the aesthetic design. Not being able to hear the spoken text would not much change the effect; in fact, the words could even rob the viewer of the magic that resides in the purely aesthetic experience. Wu Tsang’s spoken text is not necessary for this strangely one-sided dialog between stage and audience. Although the incessant interweaving of semiotic and performative processes—the haunting interplay of thoughts, colors, movements, bodies—provokes questions of what Sudden Rise means for us, here, today, in this theatre, what we experience does not provide an answer. We see carefully crafted, precisely balanced scenes, and yet we are experiencing autonomous processes. This emancipation from the poetic subject goes beyond even postdramatic theatre in two transgressive aspects.

Figure 2. From left: boychild and Wu Tsang in Sudden Rise. Schauspielhaus Zürich, 2019. (Photo by Ketty Bertossi)

Firstly, subjectivity is simply ignored, both among the characters onstage and between them and the audience. That is, even the living figures onstage seem not to recognize each other or the audience sitting in front of them in the way that people have normally done up to now,Footnote 10 in the awareness of their own subjectivity as well as that of others. Even though there is a speaker, the text—a surrealistic mix of “Sudden Rise at a Given Tune” (2018) by Wu Tsang and philosopher, poet, and performance studies scholar Fred Moten (see Moten and Tsang Reference Moten and Tsang2018) with many quotes from other authorsFootnote 11 —is not addressed to us. Even though we see actors, these seem to be no more real than their projected doubles. And we spectators do not seem to matter to the performance, which proceeds indifferent to its audience. This experienced indifference is a result of the way—the how—the performance works: stage and audience, according to the performance experience, do not seem to be connected by a communicative bond; what scenic communication reaches us seems like a statement of future, nonhuman beings. This aesthetic harbors the paradox that the performance undermines its own premise.Footnote 12 Inundated by the flood of images, we gradually become alienated from what is happening onstage. We become aware of something like the aesthetic takeover by the nonhuman. Instead of protagonists, we experience shapes and colors, projections and video clips, soulless bodies and statements that no longer appear to be human but seem to take on an unconscious life of their own. Wu Tsang prefigures the vanishing of the subject. There is no group of humans communicating with other, onlooking humans. By abolishing the categorical separation of showing and being shown, authorship and product, Sudden Rise resembles a natural, extratheatrical process controlled not by an author but by natural law. Sudden Rise is theatre pointing beyond theatre.

Beyond Humanity

Ensoulment of the Nonhuman

While Sudden Rise aesthetically refers to, and thus transcends, its own aesthetic frame, its second transgressive aspect is that it dissolves the borders separating our surrounding reality from our possible future by pointing, knowingly or not, to the need for a “change of perspective” brought about by the climate crisis and the destruction of the planet’s ecosystems. As Philipp Blom specifies, we need “to rethink our civilization, because from the very beginning it has been linked to the idea of dominating nature and the idea that man is above and outside of nature and is not himself nature” (in Blom and Raddatz Reference Blom and Raddatz2021:97).Footnote 13 We have traditionally focused on individuals instead of seeing the relationships among them—and between them and other living beings. The expansion of what theatre can be about, beyond what people decide and do—i.e., beyond Aristotle’s concept of action—to movements and processes whose authors can also be nonhuman actors, can be understood as the abolition of the boundaries between human action and mere event. Sudden Rise counteracts the isolation that results from the theatre’s restriction to the imitation of individual human actions by (post)theatrically repositioning humans and rethinking them as part of the complex “relation to other animals and the rest of nature” (102). By transgressing the art-life border (thus itself embodying a crisis), Sudden Rise is the answer to what Blom demands:

Theatre can analyze the anatomy of power, but it can go further. […W]e need to consider whether there isn’t a more meaningful way of conceptualizing ourselves in this world and of defining what is good about life. A system collapse is a moment when such questions must be asked anew. That is something completely different than proclaiming ideal solutions. After all, it is a matter of life and death. (in Blom and Raddatz Reference Blom and Raddatz2021:103)

In Sudden Rise, the ensoulment of the nonhuman becomes tangible in autonomous sounds, pictures, shapes, colors, and texts. These connect us not only with other species but also with our immediate environment, with the microbiome in each of our bodies and even with inanimate objects such as photos or diagrams. Blom explains:

We don’t just have to reevaluate our relationship to other animals and the rest of nature. [There is also] the completely unknown continent in our own bodies in the form of a microbiome, without which we could not exist. We form a symbiotic community with thousands of species of microbes and have more microbial than human DNA.Footnote 14 This extrahuman DNA influences everything—from our sensitivities to our illnesses, our intelligence, our personality. The microbes only function by communicating with each other. Also strategic, because they actually make decisions about what they want to produce more of than others and in which direction they want to go. We must say goodbye to the image of man as a machine. The same applies to other areas of nature. Science is beginning to describe nature as a network of relationships and states of matter, not as a collection of clearly defined individual objects. It’s like a word or a sound that only acquires meaning, identity, and potency when it appears in certain contexts, as an ephemeral part of a larger process. (in Blom and Raddatz Reference Blom and Raddatz2021:102–03)

Figure 3. From left: boychild, Wu Tsang, and Josh Johnson in Sudden Rise. Schauspielhaus Zürich, 2019. (Photo by Ketty Bertossi)

This “network,” the “larger process,” as well as the systemic crisis implied by becoming aware of it, is experienced in Sudden Rise when, for example, the big hand moves back and forth in front of the landscape, as if, in a surrealist movie, it wants to move objects. Here the hand not only bespeaks the pictural character of the image, but also gives the sense that this reality is in crisis: the current reality is experienced as brittle, and a new, unknown reality is anticipated. We feel that something is wrong, but also sense the dawn of something new. The flood of images throws us out of the present and asks, paradoxically by conjuring up the ghosts of the past, what lies ahead, what comes after us.

The modesty or restraint that Sudden Rise proposes by the mysterious autonomy of its pictures, clips, and scenic shapes arouses multiple associations with nature, empowering even nonliving, abstract entities. The performance repositions humanity by inviting, as Martina Ruhsam puts it, an “interrogation of the human, a reflection on the handling of things and materials, and on the movements and actions of human performers in relation to those of non-human entities” (2021:47). Instead of plots, new possibilities of social relations and theatrical agency come into view. Instead of acting subjects, Sudden Rise stages the appearance and disappearance of shapes and movements, thus visualizing transitions between real bodies and digital projections, sketches and diagrams, subjectivity and matter. This creates a new theatrical sensation. Spectators wonder what these ephemeral figures are, what language encodes their movement. We feel we are witnessing something we cannot yet categorize. The digital-corporeal beings in Sudden Rise do not fit any vision of our future (as subjects who control nature and digital technology) but rather acquire a life of their own, reaching out for new, autonomous structures of space and meaning with their own will to live.

Reframing (Human) Theory

Both transgressive aspects—the emancipation from the poetic subject and the dissolution of borders between human action and mere event—transcend the theatrical frame and raise performance theory questions. With the porosity or even disappearance of subject and identity and the thematic link to ecological precariousness of humanity, Sudden Rise presents itself as a disappearing institution: a recursive loop through which the theatre questions, contradicts, and crosses out its framings, making theory and practice one, conflating the representing and the represented. The question raised by the theory about human subjectivity as the source of action onstage or in life can therefore also be extended to this very theory and raises analogous questions about its subjective origin. By infecting theory in this way, Sudden Rise not only undermines the theatrical framework, but also the exclusive power of the subject over the act of thinking and writing about it. The expanded perspective provoked by the inclusion of nonhuman entities as theatrical actors disavows not only human actors and actions as the framework preconditions of theatre, but also the human subject as the originator and sovereign of its theoretical consideration. If the human being is only “an ephemeral part of a larger process,” as Blom says, analysis, too, may be the productive result of the interweaving of author and object, thought and affect, imagination and body, theory and practice. In her vision of a new, hybrid art-science, Ruhsam explains the relationship between these interwoven areas:

I do not assume an oppositional relationship between theory and practice, but rather assume that conceptual and artistic as well as material realities have always been intertwined or that they have a reciprocal influence. I will relate different voices from (the practice of) theory and (the theory of) practice. In doing so, I do not strive for the most universal knowledge or conclusion possible, but try to identify differences, singularities, contradictions, parallels, and resonances between the individual artistic settings and theoretical assertions as well as socio-political and socio-economic developments. (2021:26)

Three levels of reality are equally intertwined here: the individual-artistic impulse, the theoretical discourse in whose force field this impulse is staged, and the economic-ecological (and it should be added: material) reality by which this staging is conditioned and limited. This interweaving of art, thought, and reality undermines the categorial separation of a performance from its analysis. It implies a context-awareness from both artist and theorist, including theoretical work like my own. This is what the performer-lecturer quoted at the beginning of this article alludes to. The passage is taken from Who Touched Me?, a compilation of Moten and Tsang’s research project (Moten and Tsang Reference Moten and Tsang2016). Contextuality, the thinking together, and the hybridization of art forms, theoretical settings, social-economic backgrounds, and the material-physical reality of the artists involved appear in their text as a methodological framework for the scenic processing of theoretical discourses and the associated analyses. This joining creates a highly complex performative-poetic laboratory work. Sudden Rise turns out to be a prime example of this work: a practice that is radically tied back to its own theory, rethinking concepts of human subjectivity and thus affecting the way we reflect on (and treat) them, ourselves, others, and the world around us. Against this background, the relationship between what we encounter onstage and the framework in which this encounter manifests itself, i.e., what makes this encounter possible, must be reconceptualized.

Borrowing

The reorientation of this relationship requires an idea of how mutually exclusive objects of experience—the affective and the symbolic; the sensuously perceived and the imaginatively anticipated; the appearances and the figures we recognize in them; finally, subjectivity and the physical world—actually appear in their entanglement onstage. In what kind of “togetherness” do subject and world appear onstage in Sudden Rise?

The phenomenology of the apparitions in Sudden Rise must take into account that they stand within a framework of past and future. What it means to be a human figure here, in this performance, is closely related to its appearance amidst a sudden influx of cultural and technical reminiscences and posthuman projections. In this historical setting, the abolition of the subjective paradoxically generates a reborn self-awareness of the human subject as a temporal being. The ironic point of Wu Tsang’s work is that the human body, though vanishing, is very present, addressing the ambivalence of its subject-object status. This makes Tsang’s theatrical self-reflection a critical self-transcending, granting it new, liquid, posthuman possibilities. It radically rejects the human being as a sovereign operator who is superior to the natural world. Tsang invents a new mode of perception and also offers a different reading of the theatrical event.

By dissolving/eliminating the subject, Sudden Rise explores the boundaries of theatre. It is no longer the subjects who organize the discourse about subjectivity. Rather, their subjectivity is replaced by a conference, so to speak; convened by other beings and things, by circumstances, by nature. However, in its very replacement, subjectivity remains at stake because it seems undecidable whether the subject addresses its obsolescence or the new status of humanity. By flooding and overwhelming the spectators, the sounds and voices of the performance reach beyond both theatre and ordinary reality. They seem to be part of an expanded universe in which earthly realities are small and meaningless. They create resonant spaces of bodily/atmospheric involvement, provoking an open, reflexive and thus critical receptivity. In these spaces, the images and traces of human history and natural history take the place of actors. An autonomous self-determination announces itself, which is not humanly administered but self-legislated. The existing entities establish a frame of their own, allowing the “human” to appear in a new neighborhood, just like the framed object in a Japanese shakkei: a background landscape or a seashore that is horizontally and vertically limited by being viewed from the interior of a room. Dance theorist Gabriele Brandstetter uses shakkei to describe a subtle aspect of theatrical performance, one that “follows a different economy of appearance and entry: the borrowing” (2015:30). In a shakkei, a landscape does not appear “in a spectacular sense” but is perceived as quietly gliding into appearance, revealing a relation to its frame. Analogously, the apparitions in Sudden Rise are framed by their spatial and temporal environment—for example, the cello staccato starting five seconds before the picture storm. Except that in Sudden Rise things are reversed: instead of a natural landscape cropped and framed by the window, locating nature as a human artifact, in Sudden Rise the human appears as framed by nature. This posthuman reality forces a new awareness of one’s own ephemerality and transience. The passivity and ephemerality of the bodies appearing and disappearing onstage point to a borrowed reality in Brandstetter’s sense:

The idea of this borrowing and lending does not mean exchange and not substitution, not a borrowing or lending in an economy of taking and repaying; not the proliferations of possession and yield with the aim of an offsetting of the power of appearance. It is a mode of framing in which inside and outside appear at the same time, a transition that does not know the patterns of transmission of a figurality of appearance: not the sharpness of illusion, not the fictitious as if; neither the aura of appearance nor the suspicion of falsehood, it does not know the duality of being and appearance, of authenticity and pretense/representation. It is a different frame—as it were, the opening of a sliding door for an appearance: borrowing as a gentle carrying on. (2015:30–31)

The specific borrowing by which Brandstetter wants “to close, or should I say: to open my considerations on performance and theatrical appearance” (30) proves striking for the way images and figures step into appearance in Sudden Rise. Brandstetter’s borrowing and lending belong to a semantic field very different from civil law concepts such as the law of obligations, or economic theory concepts such as Marx’s surplus value. Both the law of obligations and surplus value are zero-sum games in which one side loses what the other gains, i.e., the sum is zero. In Brandstetter’s “borrowing,” the content does not come to the fore by rendering its frame secondary, nor does the frame dominate by pushing the content out of focus. There is no exchange or surplus value. It is not a substitution by which the appearance of something is paid for by the absence of something else. Rather, Brandstetter uses the German verb “borgen,” to borrow, and the compound verb “verleihen” in the double sense of “to lend” and “to give something a quality,” the additional quality serving as a framework with which to highlight and emphasize something, to make it stand out, to bring it to the fore. Frame and content share a common space, suggesting equal importance. This type of presentation—from the Latin presentare, to show, to demonstrate—requires the frame not to logically exist before its object, but to appear simultaneously with it. What is being presented appears at one and the same glance in sensual apprehension (Kant’s Anschauung) as syntopic: at the same time in the same place. What is framed in this way is neither spatially in front or temporally behind; it is not logically conditioned by the frame (in the sense of only coming into being after what conditions it), nor does it condition the frame. It presupposes and is at the same time presupposed: by framing, it itself is framed. If we replace object and frame with the Kantian “Anschauung” (often poorly translated as “intuition” or “envisagement”) and “Begriff” (concept; the formal, logical part of a thought), the simultaneity of the presented object and the presenting frame is reminiscent of Kant’s “Thoughts without content are empty, perceptions without concepts are blind” ([1781] 1956:95). Kant favors neither sensual perception nor conceptual thinking, insisting on their interdependence.

In a similar line of thought, Brandstetter’s “at the same time” (“time” here includes spatial, temporal, and logical relations) tries to overcome Western dichotomies by playing not a zero-sum game but a win-win: the simultaneous awareness of figure and frame so that distinctions between truth and falsehood, to be or to appear to be, authenticity or representation, are obsolete. Brandstetter describes this with a Hitchcockian image: the opening of a sliding door as being itself the appearance of what is disclosed. The sliding door equates the foreground and background so that a new affective thinking “suddenly rises” where what and how are united and where the borrowing (of a scene by another one) becomes a gentle carrying on (between them). In this kind of borrowing, the picture torrent of Sudden Rise’s opening scene works both within and outside the performance—using the performance as a sliding door that simultaneously appears (as itself) and reveals (something else). Performance and subjectivity do not appear “because of” or “on the basis of” each other but in the same borrowing togetherness.

Gentle Transition to a Posthuman Collective

Brandstetter’s “borrowing” rejects the traditional divisions that subliminally codetermine theatrical discourses: real bodies vs. fictitious characters, scenic facts vs. imaginary settings, being vs. appearance, frame vs. content. From a phenomenological point of view, the “apparent” and the “real” are not distinguishable by their “power of appearance”; nor logically, because the term “power of appearance” suggests that we can distinguish between what is a strong and what is a weak phenomenon in the first place, which in turn would presuppose knowing the difference between what “seems to be” and what is “really” there.

The hybridity of reality and appearance—the anti-Aristotelian convergency of substance and form—in the Japanese shakkei is difficult to conceive and hard to experience. “Inside” and “outside” appear as a single process that intertwines the awareness of a frame with an equally strong awareness of what is cut out and thus emphasized by this frame. Sudden Rise provides a shakkei-like theatrical frame inside which there is an entirely different aesthetic phenomenon: the image storm of the opening scene. These flashing images, which represent only a tiny part of the collective memory, are experienced as if they represent the totality of cultural events, including this theatrical performance: they frame what they are framed by (the actual performance)—a paradoxical loop, analogous to that of the subject and its materiality. Because we are used to hierarchical classifications such as frame and picture, author and oeuvre, performance and scene, we find it difficult to give equal weight to both, the framing and the framed, in the shakkei. It seems strange that the image storm itself is the framework for the entire performance. We tend to split one and the same phenomenon into two reciprocal processes, a structure in which the two parts appear alternately framed by each other. Thus, for us, the experience of “borrowing” composed by the performers becomes a framing paradox. We fail to understand the simultaneity of inside and outside.

In this paradoxical way, the performance interweaves inside and outside, gliding at every moment from appearance to being, from speaking-of to doing, that is, it becomes a gentle carrying on that even blurs the dividing line between ontological and epistemological status. This opening scene, despite the overkill, presents authentic documents, making the scene appear realistic and factual. The rapidity of the sequence of images is thwarted by the juxtaposition of cultural-historical images such as paintings and images of saints alongside trivia such as the cargo steamer or the mysterious bar chart; the slow gentle music; the dim lighting; the synching of the cello staccato and the projections; the reticent, anodyne voice; the calm, mechanical look and speech of the factory robots. These demonstrate Moved by the Motion’s aesthetic strategy: the meticulous attention to every detail inviting us to study each single document, which we cannot do in the fragment of time allotted to each. We catch only infinitesimal glimpses of endearing little things—the moon, the cavity in the pavement, the jazz-blues “Stolen Moments,” Louise Bennett’s Jamaica Labrish, the absurd diagram title “Antral Manometry in Rumination Syndrome,” the hands at a prison window grille. This flood of details not only demands from us an affective reconstruction of our cultural history, but also reminds us gently of our individual lives. The awareness of the contrast between the simplicity of the images and the overpowering sensuality of them awakens in us the longing for a re-view of these images that we lose so quickly, along with their contexts, producing a nostalgia for a culture whose demise we read into the fast-forward of the opening scene. These cultural reminiscences ultimately turn out to be a declaration of love for the very culture that may be lost in a posthuman world. Due to their numbers and the impossibility of comprehending all their connotations and networks of meaning, the icons and diagrams flying by turn into a strange, autonomous being, a living natural phenomenon with a life of its own testifying to an unreal, absurd, unknown reality.

Figure 4. From left: boychild, Wu Tsang, and Josh Johnson in Sudden Rise. Schauspielhaus Zürich, 2019. (Photo by Ketty Bertossi)

The effects that arise from the juxtaposition of scientific realism and poetic surrealism in the opening scene continue later in the show when actual bodies and digital body images merge. At first glance, this feels futuristic, astral, even esoteric, and yet realistic. We journey to another galaxy, another reference to life that transcends the anthropocentric Western spectator’s mindset. What “suddenly rises” is a new order, a new complicity between bodies and meaning, time and corporeality, frame and message. Almost casually, the male-female dichotomy is also overcome. What emerges is a cosmic order guided by nonhuman beings who put a historically outdated humanity into perspective, especially its subjective-destructive drive.

Sudden Rise thus symbolically proposes, and aesthetically presents, a utopian collective endeavor close to Bruno Latour’s new “political ecology” (Latour Reference Latour1999:9) leading to “a common world, what the Greek called a cosmos” (18). Latour argues that the traditional political economy “contrary to its frequent statements, is unable to preserve nature” because it has not radically thought through its concepts. Above all, the traditional concept of nature is untenable because it describes both a part of reality (nature outside of humans) and at the same time the whole, that is, “the (non-social) nature and the (nature of the) social” (77). All traditional societies, says Latour, are barbaric because they think they are “surrounded only by insignificant entities threatening destruction […], a nature to be governed” (276). In contrast, a civilized society is able to “draw lessons from what it has pushed out” (276). To do this, however, it must “play through the primal scene of colonization again, but this time the person setting out to meet civilized people is himself a civilized person” (277). To make this civilized encounter possible, Latour tries to emancipate theory from its basic myth that science can rescue our otherwise wrong and deficient politics,Footnote 15 proposing instead the “progressive composition of the common world” (32). Such modest restraint requires a revision of what Latour calls the three fundamental concepts that guide the West: “polis, logos, and physis” (375). A new policy depends on a new concept of nature, and this in turn “depends, just like the concept of politics, on a specific concept of science” (375).

Traditional political ecology tried to take into account the interests of nature—without first critically reconsidering the concepts of nature and politics and, if necessary, re-founding them. These terms have “been defined over the centuries in such a way that any rapprochement, any synthesis, any combination, of the two has been prevented” (Latour Reference Latour1999:11). Political ecologists tried to overcome the dichotomies of “persons and things, legal subject and scientific object, production system and environment” without considering that these dichotomies have been “modeled, stamped and chiseled to gradually become incompatible” (11). A new political ecology requires the transition from the old “two-chamber-collective” (72) of nature and society, or “‘things’ and ‘persons’” (67), towards the idea of a single collective in which beings would be grouped “that we, Westerners, would insist to be housed separately” (66). This implies a “procedure to collect the associations of humans and non-human beings” (351)—including “material things” (128), and “well-formed propositions” (129). However, to achieve this new society, we must take the time “not to cut the Gordian knot, but to shake it in a thousand ways until a splicing iron can be inserted to untangle a few ends and tie them differently” (11–12). In Sudden Rise, such a slow taking-one’s-time can be physically felt. The beings telling us this show themselves in their timeless, gliding, hybrid appearance as part of the utopian reality they project. We experience a gentle transition into a posthuman coexistence—the theatrical anticipation of Latour’s “cosmos” both in the “Greek meaning as arrangement, harmony,” and in the “traditional meaning of world” (352), denoting a “good shared world,” defined as the “provisional result of the progressive unification of the outer worlds” (357).

In Sudden Rise, which is performed in our world now, on this side of utopia, there is a tension between the subjective perspective and the surrounding reality. This tension runs through the entire performance and is prefigured in the opening scene’s flood of images that appear before us like independent, objective realities—an infinitesimally tiny fraction, as I said, of all the cultural icons that actually exist. In them we therefore experience both the immeasurable reality that surrounds us and the contingency of an individual choice made by the artists. What seems to be a comprehensive summary of cultural history is actually one set of possibilities among countless others. The independent world still contains traces of subjectivity. But the affective experience of this flood of memory debris suggests a new reality that is no longer dominated by humans. Rather, both digitally and physically present bodies become servants of a passive submission to movement, light, and sound that cannot be classified as female or male. This gender ambiguity makes them irrelevant as traditional dramatic subjects. In them, not the factual but the possible, the potential, is revealed. Their ambiguity gives them no place in history, but it gives them a future. The scenic figures live in gender-free spaces that at present seem unreal to some of us. With their historically gendered bodies now obsolete, they seem ready for transformation into a new, integrated posthuman mode of existence. They are precursors of a coming society in which the biblical instruction to subjugate the earth is reinterpreted to suit a still unfinished creation in which the relationship to other living beings (animals, plants, viruses, bacteria, etc.) is reevaluated. The boundaries between living beings are transforming into new forms of interdisciplinarity in the broadest sense, allowing for Latour’s collective. The delicate sensuality of Sudden Rise, especially Wu Tsang’s final approach to the audience—when she walks towards us in a kind of purgatory scene, in the flickering light like a savior, speaking calmly about cruelty and injustice—thus proposes a communion of human and nonhuman, biological and digital beings, an aesthetic convergence between an affective-physical and a symbolic-ethical world. Sudden Rise affirms Latour’s statement that “after centuries of misunderstanding, ‘first contacts’ are now being resumed” (Latour Reference Latour1999:277).

Figure 5. Wu Tsang in Sudden Rise. Schauspielhaus Zürich, 2019. (Photo by Ketty Bertossi)

The relief we may feel at the thought of justice between humans and nature, things and beings, recognizes the crucial mistake in the age-old opposition of subject and object. As Ruhsam explains, the problem with the subject-object dichotomy is primarily its power imbalance:

It is an attempt to consider things as performers and to stage assemblages or entanglements of human and material bodies in such a way that dichotomous attributions (subject versus object, activity versus passivity, value versus worthlessness, the choreographer versus the choreographed) are confused. (2021:87)

Traditionally, “object” stands for passivity, oppression, lack of codetermination, and reification; while “subject” is associated with autonomy, self-determination, rationality, freedom, and agency. Yet today, in an era of performance capitalism, in which the subject is increasingly viewed as human capital, the demand for subject status paradoxically seems like a voluntary leap into submission. The autonomy of the subject becomes a threat in the face of increasing social disintegration, climate change, and ecological crises. An integrated understanding of subjectivity as a part and partner of nature seems overdue.

At the end of the performance Wu Tsang stands before us. The new (post)human suddenly rises in a sparsely flickering light like a futuristic promise. The figure comes closer, gets bigger, and finally retreats again, disappearing into a pleasant, gently enveloping darkness. The scene recalls Foucault’s prediction that just as they appeared, humans will disappear again “like a face in the sand on the seashore” (1966:398).Footnote 16 From the obsolescence of the actors’ bodies onstage, there is an arc to the obsolescence of humanity in a nature that might be much better off without us. In Tsang’s work, however, the bodies don’t disappear, but are present to the end, dancing and coming closer to the spectators as the end approaches—as if moved by the same life principle that also animates their surroundings. Integrated in their environment, “such a rethinking of man” is inevitably, as Blom formulated, a “rediscovery of man” (in Blom and Raddatz Reference Blom and Raddatz2021:103). It is time to recognize the fragility of our lives, the dependence on others, and to redirect ourselves towards a politics and aesthetics of fragility that demands social, but also cognitive justice. A fragility that is allowed to show itself in theory, in its discourses, and in its reflections in the theatre.