Introduction

Over the last decades, the incidence and survival rates of cancer have increased, and therewith the number of patients who have received curative treatment for cancer (Rowland and Bellizzi Reference Rowland and Bellizzi2008; Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Rutherford and Bardot2019; Sung et al. Reference Sung, Ferlay and Siegel2021). After completion of treatment, patients face a transitional period known as the re-entry phase (Stanton Reference Stanton2012). In this phase – typically the first 18 months after curative systemic treatment, patients need to resume their former lives despite changes in life due to long-lasting physical and psychological symptoms of the cancer treatment. These difficulties are not always understood by their social environment (Tan et al. Reference Tan, Butow and Boyle2014). Patients face existential concerns such as fear of death, loss of control, vulnerability, isolation, rejection, meaninglessness, and threats to self-identity (Henoch and Danielson Reference Henoch and Danielson2009; van der Spek et al. Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-kraan2013; Post et al. Reference Post, Ganzevoort and Verdonck-de Leeuw2020).

Especially, patients treated for breast cancer or melanoma are both groups that frequently report existential concerns in the re-entry phase (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Savadatti and Gurmankin Levy2009; Drageset et al. Reference Drageset, Lindstrøm and Underlid2016; Martínez Arroyo et al. Reference Martínez Arroyo, Andreu Vaíllo and Martínez López2019; Visser et al. Reference Visser, Post and Dekker2022). After finishing long-lasting (neo-)adjuvant systemic treatments (Bleicher Reference Bleicher2018; Seth et al. Reference Seth, Agarwala and Messersmith2023; Tolaney et al. Reference Tolaney, Tarantino and Graham2023), patients lose the safety net of hospital care (Holland and Reznik Reference Holland and Reznik2005; Stanton Reference Stanton2012). During the first year after finishing treatment, unmet needs are more prevalent than in long-term survivorship (Martínez Arroyo et al. Reference Martínez Arroyo, Andreu Vaíllo and Martínez López2019). These unmet needs encompass, among others, managing the expectations of being labeled a “cancer survivor,” acknowledging the impact cancer has made, and navigating life decisions (Martínez Arroyo et al. Reference Martínez Arroyo, Andreu Vaíllo and Martínez López2019). Addressing these existential unmet needs is crucial in preventing the onset of chronic and persistent distress, which can lead to diminished overall well-being (Martínez Arroyo et al. Reference Martínez Arroyo, Andreu Vaíllo and Martínez López2019).

Several effective interventions aimed at enhancing a sense of meaning and purpose have been developed in order to increase cancer survivors’ well-being. The fundamental motivational force for wellbeing, according to Frankl (Reference Frankl1992), the founder of logotherapy, is man’s search for meaning. Informed by Frankl’s work, Breitbart et al. (Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2015) developed Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy (MCP), a psychotherapeutic intervention to support patients with cancer in finding meaning and purpose. Van der Spek et al. (Reference Van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-kraan2017) subsequently adapted MCP for cancer survivors. An alternative approach entails the enhancement of narrative meaning-making (Hartog et al. Reference Hartog, Scherer-Rath and Kruizinga2020), drawing upon Ricoeur’s theoretical perspective, which facilitates individuals in constructing meaning from their cancer experience through processes of storytelling and retrospective life review. An example is the spiritual life review intervention for cancer survivors (Post et al. Reference Post, Ganzevoort and Verdonck-de Leeuw2020).

Still another conceptual framework is the meaning-making model of Park (Reference Park2010), which conceptualizes the meaning-making process as the reappraisal of a negative event that conflicts with one’s global meaning (i.e., one’s beliefs, self-identity, goals, and values). This can result in “meanings made,” reflecting either an adapted understanding of the event or a changed (global) meaning. Such meaning-making is ultimately valuable in promoting growth and identifying meaningful goals to pursue (Park Reference Park2022). In rehabilitation medicine, an intervention was developed informed by this model, in which patients’ global meaning was explored as a starting point for setting rehabilitation goals (Dekker et al. Reference Dekker, de Groot and Ter Steeg2020). This approach showed that addressing global meaning contributed to the intrinsic rehabilitation motivation of patients (Littooij et al. Reference Littooij, Doodeman and Holla2021).

Drawing on these promising findings and taking feasibility into account, we developed an existential intervention in a single one-hour format based on this approach. Our aim was to support patients treated for breast cancer or melanoma in their meaning-making process, with a focus on setting meaningful goals in the re-entry phase. Although existential interventions such as MCP and spiritual life review have shown promising results (Breitbart et al. Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2015; Van der Spek et al. Reference Van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-kraan2017; Bauereiß et al. Reference Bauereiß, Obermaier and Özünal2018; Post et al. Reference Post, Ganzevoort and Verdonck-de Leeuw2020), these interventions comprise several sessions, are solely intended for patients with high levels of (psychological) distress, and are not specifically designed for the re-entry phase (Vehling and Philipp Reference Vehling and Philipp2018).

An intervention in the re-entry is of importance, as the transition from active treatment to survivorship can bring about a significant shift in life’s meaning (Park et al. Reference Park, Magin and Bellizzi2024), and the meaning-making process shifts from coping with the effects of the disease and treatment to navigating the challenges of picking up life (Visser et al. Reference Visser, Post and Dekker2022). Patients treated for melanoma or breast cancer reported drawing on existing sources of meaning while also adapting, strengthening, or seeking (new) sources of meaning to address existential concerns and life changes during this transition (Visser et al. Reference Visser, Post and Dekker2024). We expect that enhancing patients’ awareness of their personal sources of meaning may strengthen the process of meaning-making, goal-setting, and dealing with existential concerns in the re-entry phase. Ultimately, the aim of the intervention is to empower and motivate patients to pick up life (Visser et al. Reference Visser, Post and Dekker2024). The present study employed a mixed-method formative evaluation to assess the intervention, recognizing that this is crucial for ensuring effective translation into meaningful patient care (Elwy et al. Reference Park, Magin and Bellizzi2008).

Methods

Study design and setting

This study used a formative evaluation method with a mixed-methods design to evaluate an intervention to support patients with their meaning-making process, with a focus on picking up life and setting meaningful goals in the re-entry phase. We used a combination of semi-structured interviews and questionnaires. The study was performed at the outpatient clinic of Medical Oncology in the Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc, between June 2021 and February 2022. This study is reported according to the guidelines for Good Reporting of A Mixed Methods Study (O’cathain et al. Reference O’cathain, Murphy and Nicholl2008).

Patient selection

Eligible patients were recruited by their oncologist or nurse practitioner. Patients were included after finishing systemic treatment with curative intent for breast cancer stage or melanoma (i.e, breast cancer stage I–III and melanoma stage III). Patients had to be in the re-entry phase, defined as the period from completion of surgical and systemic treatment (with the exception of hormonal therapy) up to 18 months, with no signs of recurrence of disease. Other inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 18 years and proficiency in the Dutch language. We hypothesized that 10 to 15 interviews would be sufficient to achieve saturation, given the specificity of the phenomenon under study.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of a single semi-structured conversation concerning meaning-making for one hour. The intervention took place in the hospital and was carried out by an experienced spiritual counselor (LP). The aim of the intervention, which was based on the results of a focus group study about meaning-making in the re-entry phase (Visser et al. Reference Visser, Post and Dekker2024), was to support patients’ meaning-making process in the re-entry phase by exploring their sources of meaning. This was supposed to help patients identify the sources of meaning they can rely on during the re-entry phase and help them find new or adapted sources of meaning to deal with the changes in life and existential concerns.

During the intervention, patients were asked about their goals or challenges regarding the re-entry phase. Second, sources of meaning were explored, concerning relationships, inner posture, worldview, identity, and values in life. Finally, the spiritual counselor explored together with the patient how the patient’s sources of meaning could be helpful in dealing with their challenges in the re-entry phase and set meaningful goals for the re-entry phase. The structure of the intervention is shown in Appendix 1.

To ascertain whether patients would derive benefit from a summary of the conversation, we randomly assigned one-third of the patients to receive a summary of the conversation made by the spiritual counselor, one-third to receive a handout immediately following the conversation, which outlined the global sources of meaning (relationships, inner posture, worldview, identity and values in life), and one-third to receive no additional material to take home.

Ethics

The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc, The Netherlands. It was declared that the Research Involving Human Subjects Act did not apply to this study. All patients provided informed consent. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

Qualitative data

The qualitative evaluation took place three months after the intervention. A semi-structured interview was conducted via Zoom by a trained researcher (AV). The interview protocol focused on evaluating the intervention in terms of experience and appreciation, as well as assessing the perceived benefits. Each interview lasted approximately 30–45 minutes. With participants’ permission, interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional company.

Quantitative data

Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire online at baseline (T0), one week (T1), and three months post-intervention (T2). Questionnaires were completed online using the web-based survey tool Survalyzer Essential 2020. The last questionnaire had to be completed before the evaluation interview took place. The process and outcomes of meaning-making were evaluated by the Dutch version of Ryff’s Scales of Psychospiritual Well-Being (consisting of eight subscales: positive relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life, self-acceptance, inner strength, and relationship with a higher power) (van Dierendonck Reference van Dierendonck2004) and the Personal Meaning Profile (a total score of meaning in life with five subscales: goal-orientedness, fairness in life, relationship with God, relationships with others, and dedication to life) (Jaarsma et al. Reference Jaarsma, Pool and Ranchor2007). The Mental Adjustment to Cancer (MAC) scale (consisting of two summary scales: positive and negative adjustment to cancer (Watson et al. Reference Watson, Greer and Young1988; Braeken et al. Reference Braeken, Kempen and Watson2010) was used because it is known that successfully adapting or creating new meaning from the cancer experience leads to better adjustment to cancer (Park et al. Reference Park, Edmondson and Fenster2008).

Data analysis

Qualitative data

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software 2021) was used for coding. Transcripts were analyzed using reflexive thematic content analysis (Clarke and Braun Reference Clarke and Braun2017; Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2019). The analysis was guided by both predetermined evaluation criteria (expectations, experience, appreciation, benefits, enhancements, and recommendations) and researchers’ openness to emerging concepts. The recordings of each interview were coded by one researcher (AV); spot checks were conducted every third transcript by a second researcher (LP). The aim was to reach consensus on the outcomes by mutual agreement. After this discussion, the researchers compared, contrasted, refined, and grouped all codes into themes, after which saturation of all generated themes was evaluated. Themes were further refined as the data were sifted through multiple times. The number of patients who referenced a specific theme was quantified. This was incorporated into the text through the use of descriptors, whereby “a single patient” indicated one patient, “a few” indicated up to a quarter of the patients, “some” indicated up to half of the patients, “many” indicated up to three-quarters, and “most” indicated more than three-quarters of the patients.

Quantitative data

Survey data from the questionnaire survey saved in Survalyzer were entered into SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0, 2021). Changes in outcome measures over time were assessed using linear mixed models analysis (LMM). A fixed effect for measurement-time and a random effect for subjects were used. Effect sizes were calculated by dividing the difference in change since the baseline by the pooled standard deviation, at the separate points in time (one week and three months post-intervention). Effect sizes of 0.2 were categorized as small, 0.5 as moderate, and 0.8 as large (Cohen Reference Cohen2013). Only effect sizes were reported, because it is well recognized that effect size is more informative than statistical significance in small samples, as P-values are strongly influenced by sample size (Sullivan and Feinn Reference Sullivan and Feinn2012).

Results

Patients

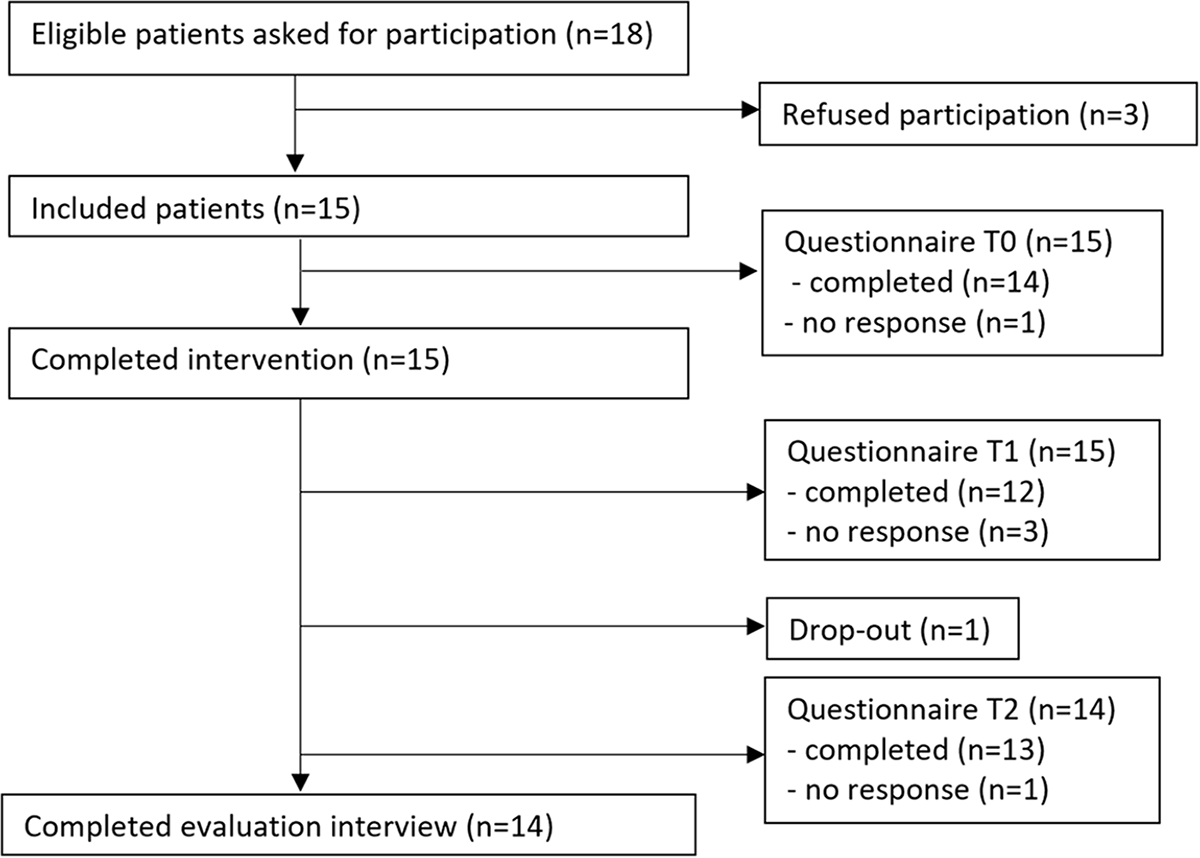

A total of 18 eligible patients were asked to participate. One participant refused without providing a reason, one patient did not feel the need to participate, and another patient felt the intervention was too soon after the end of treatment. Fifteen patients were included. Seven patients had been treated for breast cancer, and eight patients had been treated for melanoma. Participant demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographics of participants

Study adherence

One patient with melanoma withdrew from the study without providing a reason after completing the questionnaire at baseline, the intervention, and the questionnaire one week after the intervention. Consequently, 14 patients completed the evaluation interview. Of the 15 patients, 11 completed the questionnaire at all three time points. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the inclusion and data collection.

Qualitative results

The following themes resulted from the analysis:

A detailed description of each theme and subtheme is provided, accompanied by quotations from the evaluation interviews in Table 2.

Table 2. Themes with description of each subtheme accompanied with quotes

Overall evaluation

Qualitative interviews demonstrated an overall positive experience and appreciation of the intervention. Most patients reported they felt at ease and appreciated the support and the opportunity to share their experiences. Many patients indicated that the conversation covered all important topics.

Perceived benefits of the intervention

Patients reported the following perceived benefits of the intervention: reflection on existential concerns and sources of meaning, validation of sources of meaning, insights into the use of sources of meaning, and motivation to pick up life. Patients reported, to a lesser extent, setting priorities, identifying meaningful goals, and undertaking specific actions post-intervention.

Optimization of the intervention

Many patients made suggestions on how to tailor the intervention more to their needs and requested additional supporting materials. This included suggestions for adjusting the timing of the intervention and the role of the spiritual counselor to better meet individual needs, as well as recommendations for more comprehensive preparation and a summary of the intervention afterwards.

Quantitative results

Patient reported changes in the experience of meaning in life and mental adjustment to cancer following the intervention. Increases with small effect sizes were observed in the subscales fairness in life, autonomy, and goal-orientedness one week after the intervention. Goal-orientedness also showed a small effect size improvement three months after the intervention. Detailed results are presented in Appendix 2.

Discussion

This mixed-method formative study evaluated an intervention to explore one’s sources of meaning and help set meaningful goals for the re-entry phase after systemic cancer treatment. The intervention was designed to support meaning-making after cancer treatment to help patients address existential concerns (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Savadatti and Gurmankin Levy2009; Stanton Reference Stanton2012; van der Spek et al. Reference van der Spek, Vos and van Uden-kraan2013; Dekker et al. Reference Dekker, Braamse and Schuurhuizen2017; den Bakker et al. Reference den Bakker, Schaafsma and Huirne2018; Park et al. Reference Park, Magin and Bellizzi2024) and motivate patients to pick up life. Patients responded positively, reporting multiple benefits. The qualitative findings highlight the potential of a single one-hour session to facilitate patients’ meaning-making process. The intervention facilitated reflection, and it validated what patients find meaningful, as well as the meaning they ascribe to their experiences and actions. It motivated patients to pick up life again and to use identified sources of meaning to address their existential concerns. It prompted some patients to reorient in life by prioritizing, setting goals, or adopting different approaches to their situation.

Notably, the benefits varied in the degree of patient engagement. Reflection was facilitated by probing questions of the spiritual counselor, which enabled patients’ awareness and acknowledgment of their sources of meaning and existential concerns. Furthermore, the intervention instigated validation, motivation, and insights into how to use their sources of meaning during and after the intervention. This empowered patients to derive strength from sources of meaning and actively self-manage their meaning-making processes. Empowerment has been increasingly recognized as an important component in cancer survivorship care (Jørgensen et al. Reference Jørgensen, Thomsen and Ross2018). Some studies highlight its association with the motivation to find meaning after cancer (Mok et al. Reference Mok, Martinson and Wong2004) and the pursuit of personal and health-related goals (Groen et al. Reference Groen, Kuijpers and Oldenburg2015). The most active forms of engagement were reflected in the themes of prioritization, identifying meaningful goals, and action-taking, collectively representing a form of existential reorientation. Reflection, empowerment, and re-orientation may represent conceptual constructs that require further investigation in the future to refine the intervention.

Based on the intervention on setting meaningful goals in rehabilitation (Littooij et al. Reference Littooij, Doodeman and Holla2021), we expected goal-setting for the re-entry phase to be a clear benefit. Goal-orientedness showed a small effect size improvement after intervention; however, the qualitative results regarding goal-setting were mixed. Not all patients reported setting goals, and the desire to set goals varied among patients. Moreover, some patients identified meaningful goals but were not aware of them as such. These goals were not actively and specifically targeted toward the re-entry phase, but were more personal strivings in life. Earlier research on goal-setting in cancer survivors showed that patients find it hard to specify exact goals (Hauken et al. Reference Hauken, Holsen and Fismen2014), and that goals that are set can be viewed more as general hopes or desires, such as “get back to normal” and “stay cancer free.” These goals are similar to the goals we found in our focus groups prior to the development of this intervention (Visser et al. Reference Visser, Post and Dekker2024). This raises the question of whether all patients actually feel the need for goal-setting, and whether the current intervention addresses goal-setting sufficiently and appropriately. We propose that in the future design of the intervention, the spiritual counselor involved in the intervention makes implicit goals more explicit and documents them as “meaningful goals” in the summary provided to patients afterwards. Additionally, if patients wish to, the intervention could facilitate the translation of general goals into more specific actionable goals by providing patients with suggestions on how to bring this into practice (Bovend’Eerdt et al. Reference Bovend’Eerdt, Botell and Wade2009).

Our intervention is the first existential intervention that uses a single session of one hour only for patients, specifically in the re-entry phase, that can empower patients to resume their lives (Oh and Kim Reference Oh and Kim2014). This approach places minimal strain on hospital staff resources. As this current evaluation is of a formative nature, the findings can be used to maximize the benefits of the intervention. First, it is essential to align the timing with the patient. The focus of the meaning-making process in the re-entry phase shifts from focusing on the disease and treatment to focusing on picking up life (Visser et al. Reference Visser, Post and Dekker2024). Our findings showed that the optimal timing for the intervention was depended on patients’ perception of when they felt ready to resume their “normal life” again. It should be the responsibility of the healthcare provider to liaise with the patient to ascertain this moment and to schedule the intervention accordingly. Furthermore, not all patients felt prepared for the intervention. It is recognized that both patients and healthcare professionals lack sufficient knowledge regarding the nature of existential and spiritual interventions (van de Geer et al. Reference van de Geer, Groot and Andela2016; Best et al. Reference Best, Washington and Condello2022; Stavig et al. Reference Stavig, Bowlby and Oliver2022). Therefore, patients should be adequately informed to know what to expect, and healthcare professionals should be better informed to counsel patients. Finally, in accordance with the findings of the evaluation, a summary should be provided to patients following the intervention to enhances its benefits of the intervention.

Based on literature, we anticipated that supporting the meaning-making process would strengthen certain sources of meaning, leading to increases in meaning in life and psychospiritual well-being, as well as greater positive adjustment to cancer (Park et al. Reference Park, Edmondson and Fenster2008; Park and Gutierrez Reference Park and Gutierrez2013; Breitbart et al. Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2015; Bauereiß et al. Reference Bauereiß, Obermaier and Özünal2018; Visser et al. Reference Visser, Post and Dekker2024). Our qualitative findings suggest that sources of meaning were strengthened, while quantitative findings demonstrated modest improvements in goal-orientedness, fairness of life, and autonomy. Notably, the quantitative analyses were constrained by the limited sample size of 11 patients who completed all three questionnaires. However, future research should also reconsider the appropriateness of the instruments used to evaluate the intervention, as the limited sample size may not be the only explanation for the modest quantitative effects. Furthermore, a more targeted approach to identify those who derive the greatest benefit from this intervention is necessary to optimize its effectiveness. A multicenter study with a larger sample size should be conducted to assess the feasibility, effects, and determine the best methods for implementing this intervention.

Strengths and limitations

In addition to qualitatively assessing patients’ experiences, appreciation, and perceived benefits, a strength of this formative evaluation was its ability to identify opportunities to further optimize the intervention. Another positive aspect was the high participation rate. However, it should be noted that the study was susceptible to selection bias. It is possible that healthcare providers may have selected patients they believed are suitable for this type of intervention.

Conclusion

This formative study shows that a one-hour intervention on meaning-making is applicable, positively experienced, and well appreciated by patients treated for breast cancer and melanoma in the re-entry phase after cancer. The qualitative evaluation presented promising results that a single one-hour intervention supported patients’ meaning-making process, in particular through reflection on, validation of, and use of their sources of meaning, and supporting motivation to pick up life. The evaluation identified possibilities for further optimization of the intervention. A multicenter study is needed to evaluate the feasibility, implementation, and beneficial effects of the intervention.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author’s contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection was performed by Anna Visser. Data analysis was performed by Anna Visser and Lenneke Post. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Anna Visser and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from Novartis Pharma B.V. (Grant number: 1325851).

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Amsterdam University Medical Center.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix 1:Structure of the intervention

Appendix 2