Introduction

Looking after Country is a significant and shared tenet of Australian Aboriginal philosophies of place and being. For Marra people, like many other Indigenous groups across Australia, the world is structured in a kin-centric system where all things—human and non-human, material and non-material—are understood in terms of their relation to one another and the responsibilities those relationships create (Bradley Reference Bradley2022, 68; Kearney Reference Kearney2023, 15; li-Yanyuwa li-Wirdiwalangu et al. Reference Brady, Bradley and Kearney2023). In such a relational lifeworld, it can be considered an ‘obligation and moral duty’ to clear campsite floors and to keep Country clean (Kearney Reference Kearney2009, 326).

A stone artefact mound uncovered at Walanjiwurru 1 rockshelter in Marra Country reveals how these philosophies manifest through maintenance practices. While large-scale mounds have been studied extensively in Australia and internationally (see below), the small scale and incredibly dense composition of 8622 stone artefacts that is the focus of our study is a unique occurrence rarely documented in archaeological literature.

This study addresses the mound with three aims: to document the formation and composition of the mound through integrated archaeological and cultural analysis; to understand this feature within Marra frameworks of stone significance and maintenance obligations; and to integrate archaeological and Indigenous knowledge systems into our theoretical approach.

This research advances archaeological understanding in several significant ways. It demonstrates how maintenance activities carried out by Marra malbumalbu (a Marra term for deceased Marra men and women, or the ‘Old People’) embody cultural significance beyond simple cleaning practices, reveals how stone artefacts operate within broader cultural frameworks and provides a practical example of successfully integrating Indigenous and archaeological knowledge systems. While archaeological studies have previously documented sweeping as a site-formation activity (Binford Reference Binford1986; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Conard, Goldberg and Berna2010; O’Connell Reference O’Connell1987) and the social significance of stone in Australia has been well established (Bradley Reference Bradley, David and Thomas2008; Jones & White Reference Jones, White, Meehan and Jones1981; McBryde Reference McBryde1984; Taçon Reference Taçon1991), few studies have examined how these practices intersect with Indigenous understandings of maintaining Country.

First, we discuss the significance of stone in Marra Country, examining three major quarry sites and their associated creator Ancestral Beings (also referred to as ‘Dreamings’). Our methodological framework then details how we integrate archaeological analysis with Marra knowledge systems. The results section presents the archaeological evidence from Walanjiwurru 1 and its cultural significance, focusing on patterns that emerge through this integrated analysis. Finally, we discuss how this evidence demonstrates relationships between people, materials and Country maintained through sweeping.

It is important to note that due to colonial displacements, direct Marra ethnographic accounts of rock-shelter sweeping are limited. Throughout this paper, where appropriate, we draw on closely related Yanyuwa records documented by JB, noting cultural continuity and long-standing ties between communities (see below). The Marra term malbumalbu is introduced here to frame the assemblage in local categories, and when we extend to neighbouring ethnography, we do so transparently and for specific practices.

Marra Country and stone

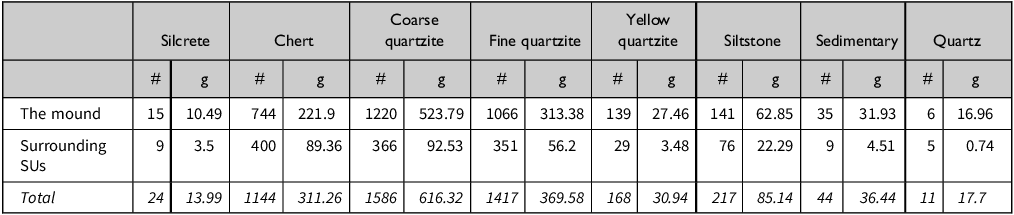

Marra Country encompasses approximately 10,000 square kilometres of the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, Northern Territory. Their Country includes coastal areas, islands, savannah plains and the distinctive sandstone formations of Yiyinji (Yinyintyi Ranges) within Limmen National Park (Fig. 1). ‘Country’ is a term commonly used in Aboriginal English to describe the bounded parameters of a group’s geographical, ecological, ancestral and socially configured world. Country (radburr) was shaped by Ancestral Beings (yijan) who imbued the land and sea with important resources, cosmological significance, ceremony and Law (Bradley Reference Bradley2018, 25; Marra Traditional Owners 2023, 3). For Marra, Country is also understood to be a living entity with agency and a will of its own, forming a social and spiritual lifeworld which is bounded by people, kin and relationships (Bradley Reference Bradley2018, 26). Marra people ‘listen to, sing for and cry for [their] country’ and have an intrinsic connection to the sea, identifying as ‘saltwater people’ (Marra Traditional Owners 2023, 3).

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Marra Country and Walanjiwurru 1 in relation to neighbouring language groups.

Due to the establishment of pastoral stations in the late nineteenth century and subsequent violence and displacement, most Marra people have not lived on their Country full-time since the 1960s (Bradley Reference Bradley2018, 17). Communities such as Ngukurr, Numbulwar, Minyerri and Borroloola are now where most Marra people live, alongside other language groups (Fig. 1). Therefore, while this paper concerns Marra people and Country, many ethnographic examples come from JB’s research with the neighbouring Yanyuwa people who today live alongside Marra people in Borroloola (Fig. 1). Yanyuwa and Marra are closely connected by marriage and shared cultural practices through Dreamings, kujika (songlines) and Law (Bradley Reference Bradley2018, 58). While they are distinct in both language and Country, their close connections mean there are many shared cultural elements which can be used to illustrate the complex ways of knowing present in the region.

Stone sources and ancestral power

Three main quarry sites, Bandabandajawawulu, Jararrawawulu and Yilakala (Fig. 2), form a part of the wider network of social and spiritual relationships that run through Marra land and sea Country (see Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022). Their importance is derived from direct links to the Ancestral Beings that created them, and the stone found there.

Figure 2. Map showing the location of Bandabandajawawulu, Jararrawawulu, Yilakala and associated Ancestral Beings in relation to Walanjiwurru 1. (Map: Hugh Cowie, using ethnography provided by John Bradley, and the following images: ‘CSIRO ScienceImage 3990 Death Adder’ by John Wombey, CSIRO licensed under CC BY 3.0; ‘Brolga’ by friendsintheair licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0; ‘Coastal-Taipan’ by AllenMcC. licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0; ‘king brown snake, mulgaschlange, mulga snake’ by Max Tibby marked with CC0 1.0.)

At Bandabandajawawulu, chert is the actual shed skin of Yalijali (Death Adder Snake Ancestral Being) who resides there (Fig. 3). Jararrawawulu, a source of quartzite, received its significance as part of the Kurdarrku (Brolga) Ancestral Being’s journey as it travelled from Yanyuwa Country and continued northwest through Marra Country. At Yilakala, the yellow quartzite was created when two powerful Bandiyan (King Brown Snake) Ancestral Beings vomited up the stone. Ancestral Beings such as these have agency of their own and can act in benevolent or malevolent manner towards people and Country.Footnote 1

Figure 3. Photo of Bandabandajawawulu, a Yalijali (Death Adder) Ancestral Being site and source of chert for the region. (Photograph: Liam M. Brady.)

Whether they rest in place or continue their journey moving through Country, the essence of each Ancestral Being is imbued in situ through their creative and generative actions. Stone sources, which can result from ancestral presence and substance, then become unique features of the landscape and present opportunities for people to make use of the ancestral power infused within the material. By integrating these factors into our categorization and interpretation of stone, we can come to a deeper understanding of what stone can be, and its value to the people who used it.

Access to stone and making tools

The power of Ancestral Beings present at quarries requires strict protocols for access under Marra Law. Responsibility for the management of physical access and spiritual safety is determined by the socio-political roles of minirringki (owners through patrilineal descent) and jungkayi (guardians for their mother’s Country), who claim authority based on their relationship to the Ancestral Beings that created the sites (Bradley Reference Bradley2018, 34). Strict control of stone sources and manufacturing is seen across Australia, with ancestral connections informing who can and cannot access such places (Howitt [1904] Reference Howitt1996, 311; McKenzie Reference McKenzie1983; Petrequin & Petrequin Reference Pétrequin, Pétrequin, Morin and Le Brun-Ricalens2020, 143). Places like these hold an immutable level of danger and if entered without proper adherence to Law are understood to cause serious illness or death (see Beirnoff Reference Beirnoff and Hiatt1978, 95). Yilakala, and its associated Bandiyan Ancestral Beings, is one such powerful place. The Bandiyan travelled southward along the coast from Arnhem Land, creating other Ancestral Beings and places, and are associated with important ceremony (Bradley Reference Bradley2018, 21). Their power is heightened at Yilakala and therefore the site must be very carefully negotiated to acquire the quartzite safely. This power affords the site a high level of respect and it has not been visited for many years, as senior men with the required level of knowledge to access it are no longer alive.

Marra knowledge of stone tools is bound closely with Law, ceremony and Ancestral presence that emphasizes relationships beyond utilitarian understandings (also see Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022). Ethnographic information regarding the specific production and manufacturing processes of stone tools in Marra Country is minimal, but we document what is known here. The Marra verb garlgjujunyi, meaning ‘to break up, to smash (e.g., stones); to hatch (egg)’ (Heath Reference Heath1981, 450), suggests a conceptual link between the birthing of something physical with making stone tools. Stone points at Yilakala were described by senior Marra men Mack Riley Manguji and Roy Hammer Abaju as always being present within the stone, needing only the skill and knowledge of a senior man to extract what already exists (pers. comm. to JB, 1984). A stone tool could then be conceptualized as an item with agency being birthed into the world. Like the Marra concept, senior Yolngu men in northeastern Arnhem Land have described some stone as containing ‘baby stones’ as if they were pregnant, which would continue to grow as they were left in the ground (Cane Reference Cane1992, 16; McKenzie Reference McKenzie1983). In the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, stone tools also maintain agency of their own as the metamorphosed remains of Ancestral Beings, with Yanyuwa senior elder Jerry Ngarnawakajarra expressing in song: ‘this stone tool is my most senior paternal grandfather, this stone tool is the Dingo’ (Bradley Reference Bradley, David and Thomas2008, 634). This recognition of stone’s ancestral ngalki (essence) positions people within kinship relationships to the material itself. It is not known how these understandings impacted the malbumalbu’s production of stone tools, but extensive evidence for working and retouching of tools can be seen throughout many rock-shelters in Marra Country.

Stone is also linked to fat, which is seen across northern Australia as symbolic of power and life (Bradley Reference Bradley, David and Thomas2008, 634; Jones & White Reference Jones, White, Meehan and Jones1981, 61; Rose Reference Rose1992, 66). For Yanyuwa people, and by extension Marra, the fat of an animal is what speaks to its health and greater well-being within its environment (Bradley Reference Bradley1997, 319). As stone is often understood to be metamorphosed remains of Ancestral Beings, some of these concepts are reflected in ethnographic observations concerning the significance of stone tools. Paintings in rock-shelters across Marra Country show animals and Ancestral Beings with their fat emphasized, signifying their vitality. While overseeing a younger man breaking stones at Ngilipitji quarry, Yolngu Country, one senior man commented ‘too lean, get inside to the fat’, indicating its importance in the extraction process (McKenzie Reference McKenzie1983; see also Bradley Reference Bradley, David and Thomas2008, 634). Taçon (Reference Taçon1991, 199) also noted that in eastern Arnhem Land objects exhibiting brightness such as fat and quartzite are considered ‘spiritually charged with power’. The links between the significance of fat, stone and Ancestral Beings suggests accessing this fat would be beneficial in producing quality stone tools.

The process of collecting stone and subsequent working into tools in Marra Country is therefore tied into complex ways of knowing, requiring negotiations of the power afforded to stone by the Ancestral Beings that created it. Understanding how the relational quality of stone affects how people treat and interact with it is critical in discerning how it fits into broader maintenance practices observed in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria.

Maintenance practices

In the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, maintenance practices are concerned with the emotional, physical and spiritual well-being of Country and its inhabitants. This concerns not only large-scale environmental issues, but also the smaller-scale cleaning of places like campsites which were (and still are) kept clean through daily sweeping (Bradley Reference Bradley1997, 386; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017, 70). The sweeping of central domestic areas keeps them both physically and spiritually clean and is part of maintaining people’s relationship with Country (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017, 72).

Alongside daily cleaning, an important part of maintaining the well-being of Country is people’s ability to interact with places physically and emotionally. Yanyuwa elders speak of Country being ‘low down’ when places are not emotionally engaged with as people are lacking the proper ability or knowledge to engage as their ancestors once did (Kearney & Bradley Reference Kearney and Bradley2009, 88). Likewise, for Marra, the ability to care for their Country is considered high priority for strengthening their position as Traditional Owners in the face of the various non-Indigenous groups invested in their Country (Marra Traditional Owners 2023, 34–5). These aspirations are founded in the moral obligation of Marra people to care for their Country according to their Law as carried by Ancestral Beings and upheld by their ancestors.

The Marra words gurljujunyi ‘to clean’ and mayamayaganji ‘to clean the floor’ are recorded by linguist Jeffrey Heath (Reference Heath1981, 456, 472), but we lack knowledge of the deeper meanings of these terms.Footnote 2 However, in the neighbouring Yanyuwa language, rlikarlika (‘to make clean’) concerns a singular activity encompassing both physical and spiritual aspects of cleaning (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017, 71). For many Indigenous Australian peoples, the separation between functional and spiritual does not exist in the way that Western academic traditions often categorize them, but instead is ‘just another pragmatic aspect of reality’ (Bradley & McNiven Reference Bradley and McNiven2019, 348; see also e.g. Kwaymullina Reference Kwaymullina2020, 27–9; Watson Reference Watson2014, 72). The perceived distinction only arises when measured against definitions of a modern Western understanding, which tends to emphasize difference between things in binary pairs (Bradley Reference Bradley2022, 23; McNiven Reference McNiven2016, 34). Therefore, maintenance of places through practices like sweeping represents more than simple cleaning in a Marra understanding. For Marra people, the cleaning of Country extends into the responsibility of people to maintain both the physical and spiritual well-being of Country, not only for sustainable future inhabitation by people, but also to protect those places which bear the marks of ancestral activity (Kearney Reference Kearney2009, 171).

Previous archaeological research

Sweeping and maintenance practices in archaeology and anthropology

Ethnographic observations in Australia and the Americas mention sweeping of debris material using either a broom, branches or hands (Binford Reference Binford1978, 347; Reference Binford1986, 553; Hayden & Cannon Reference Hayden and Cannon1983; Lampert & Steele Reference Lampert and Steele1993, 64; O’Connell Reference O’Connell1987, 82). Sweeping of stone artefact debitage, among other maintenance practices, has been identified as a major influence on the spatial configuration of Australian rock-shelters (Steele 1987, cited in Lampert & Steele Reference Lampert and Steele1993, 63). Features characteristic of sweeping in the archaeological record have been discussed, such as presence of remaining small artefacts on the floor (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Conard, Goldberg and Berna2010, 33; O’Connell Reference O’Connell1987, 82), rapid mixing of sediments with artefacts (Lampert & Steele Reference Lampert and Steele1993, 62) and in situ location of swept artefacts in less busy areas of the site (Hayden & Cannon Reference Hayden and Cannon1983, 12; Lampert & Steele Reference Lampert and Steele1993, 64; O’Connell Reference O’Connell1987, 82). Geoarchaeological studies have considered the micromorphological evidence of sweeping in the formation of hearths (Alzate-Casallas et al. Reference Alzate-Casallas, Sánchez-Carro, Barbieri and González-Morales2024; Goldberg et al. Reference Goldberg, Miller and Schiegl2009; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Conard, Goldberg and Berna2010). The influence of artefact size and shape on spatial distribution patters of sweeping with brooms has also been tested (Winter et al. Reference Winter, Green, Benfield-Constable, Romano and Drummond-Wilson2021).

Archaeological micromorphology has also become an important tool for fine-grained understandings of site-formation processes, including maintenance practices like floor sweeping (Goldberg & Berna Reference Goldberg and Berna2010; Shillito et al. Reference Shillito, Matthews, Almond and Bull2011). Experimental work shows that sweeping, dumping and trampling generate diagnostic microstratigraphic signatures in ash and floor deposits, including laminated rake-out lenses and reworked surface crusts (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Conard, Goldberg and Berna2010). At Neolithic Çatalhöyük, thin-section studies have demonstrated that floor surfaces were kept ‘remarkably clean’, by identifying the presence of frequent sweeping and micro-debris removal on floors and streets (Matthews Reference Matthews and Hodder2005; Shillito et al. Reference Shillito, Matthews, Almond and Bull2011, 1025). While sweeping and trampling are considered difficult to distinguish within hearths and are often identified together, it is suspected that a unique signature of sweeping is the separation of fine from larger material (Alzate-Casallas et al. Reference Alzate-Casallas, Sánchez-Carro, Barbieri and González-Morales2024, 16–17; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Conard, Goldberg and Berna2010, 33; see Winter et al. Reference Winter, Green, Benfield-Constable, Romano and Drummond-Wilson2021 for a macroscopic example). We did not recover oriented sediment samples from Walanjiwurru 1; however, the size-sorting of objects within the mound we observe and the stratigraphic configuration of SU6 are consistent with a maintained surface that accumulated through repeated cleaning events (see below).

In anthropological literature, sweeping has been discussed as part of meaningful engagements with place through cleaning. Notions of cleanliness are not universal, and colonial powers have a history of imposing their own views with ‘religious zeal’, leaving them unable or unwilling to see evidence to the contrary in pursuit of ‘tidiness’ (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, van Dijk and Taylor2011, 31; see also Michaels Reference Michaels1990, 15). Hill, Bradley and Standfield’s (Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017) discussion of a broom made by Yanyuwa woman Emalina a-Wanajabi demonstrates how, for Yanyuwa, objects and their associated actions are inseparable from their kin-centred ontology. The broom expresses the importance Yanyuwa people place on maintaining the cleanliness of Country in response to colonial representations of Indigenous people as dirty (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017, 70). For Yanyuwa, cleanliness concerns maintaining the physical and spiritual wellbeing of Country for the benefit of those inhabiting it (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017, 71). This challenges colonial misconceptions about Indigenous relationships with place, which have often failed to recognize sophisticated systems of environmental management and care (Hill Reference Hill2016, 46–58).

Broader anthropological discussions and Indigenous philosophical notions of cleanliness show how sweeping can be a meaningful part of maintenance practices that extend into the deeper well-being of people and place. These ideas demonstrate the value in treating sweeping as primary evidence and provide deeper insight into how Marra people may maintain relationships with Country.

Stone studies in Australian archaeology

The social significance of stone for Indigenous peoples in Australia has been relatively well documented, particularly in McBryde’s (Reference McBryde1978; Reference McBryde1984; McBryde & Watchman Reference McBryde and Watchman1976) influential work on exchange networks and quarry sites in southeastern Australia. McBryde’s research highlighted the importance of considering symbolic factors in understanding the social dimensions of stone (e.g. Brumm Reference Brumm, Boivin and Owoc2004, Reference Brumm2010; Paton Reference Paton1994). Other approaches to stone artefact studies have been reviewed extensively elsewhere (e.g. Andrefsky Reference Andrefsky2005; Hiscock & Clarkson Reference Hiscock and Clarkson2000; Holdaway & Stern Reference Holdaway and Stern2004; Tafelmaier et al. Reference Tafelmaier, Bataille, Schmid, Taller and Will2022), focusing on knapping techniques and technological change over time.

In northern Australia, researchers have documented how stone sources are understood as manifestations of Ancestral Beings and their creative action, imbuing materials with power and socio-political significance (Bradley Reference Bradley, David and Thomas2008; Jones & White Reference Jones, White, Meehan and Jones1981; Taçon Reference Taçon1991). Taçon (Reference Taçon1991) argued that preference for quartzite stone artefacts could be linked to their brightness, which is reflective of symbolic associations with the power of Ancestral Beings in western Arnhem Land. Other studies have shown that the sacred nature of particular stone types and sources has a significant impact on people’s preference and the efforts gone to access such stones (Gould & Saggers Reference Gould and Saggers1985, 120; Jones & White Reference Jones, White, Meehan and Jones1981; Ross et al. Reference Ross, Anderson and Campbell2003, 79). Bradley’s (Reference Bradley, David and Thomas2008, 635) work with Yanyuwa people demonstrated how stone tools can be understood as direct manifestations of Ancestral Beings, shifting from the vital to the super-vital in context with place, cosmogenic forces and social action. Most recently, Ash et al. (Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022, 15) argued that stone artefact assemblages in Marra Country reflect shifting socio-political power dynamics in relation to quarries and their Ancestral Beings. An important implication for this research was that for Marra people stone is meaningful, binding beings and places across the landscape both socially and politically (Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022, 15).

Mounding practices in archaeological contexts

Archaeological discussions on the social significance of mounding practices offer insight into the meaning potentially associated with sweeping. Mounded formations have been studied extensively since the late nineteenth century, with studies focused on large-scale earth and shell formations (Grinsell [1953] Reference Grinsell2014; Nelson Reference Nelson1909; Thomas Reference Thomas1891, Reference Thomas1898). In northern Australia, large shell and earthen mounds have been characterized as results of human exploitation of environmental factors (Bailey Reference Bailey1977; Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Chappell and Cribb1994; Brockwell Reference Brockwell2006), natural products of tides and bird nesting (Stone Reference Stone1989, Reference Stone1992; see also Cribb Reference Cribb1991 and Bailey Reference Bailey1993), and as remnants of large social gatherings (Morrison Reference Morrison2003).

However, the significance of mounded materials extends beyond their physical presence and cannot be explained by a materialistic approach alone (Moore & Thompson Reference Moore and Thompson2012, 280). For example, pre-Columbian mounds in San Francisco have been interpreted as layered with symbolic significance tying them into a broad cosmology linking food, home and the dead (Luby & Gruber Reference Luby and Gruber1999, 102). Likewise, Moore and Thompson (Reference Moore and Thompson2012, 268) have characterized mounds as persistent places made socially significant through continuous use and reuse. This resonates with documented practices in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, where purposefully arranged materials can evoke memories of ancestors and maintain connections to Country (Bradley Reference Bradley1997, 386). Similarly, mounding of dugong bones in the Torres Strait connects to ritual engagement with seascapes, and a physical expression of collective cultural identity (McNiven Reference McNiven2013, 576; McNiven & Feldman Reference McNiven and Feldman2003). Therefore, it is not just the final product of the mound which is important, but the act of mounding itself. This action speaks to Ingold’s (Reference Ingold2000, 189) theory of a dwelling perspective, in which ‘the landscape is constituted as an enduring record of—and testimony to—the lives and works of past generations who have dwelt within it’, where mounded materials are part of an ongoing process of living, or dwelling. Where most of the literature is focused on large-scale mounds, this perspective provides a way of understanding the much smaller stone artefact mound of our study.

Theoretical framework

For Marra people, stone holds deep cultural significance in its relation to ongoing philosophical and spiritual frameworks that underpin Marra ways of life. Integrating these understandings requires what we term a ‘relational materiality’ approach, where materials are recognized as active participants in maintaining relationships between people, ancestors and Country. We place importance on the relational qualities of stone which cannot be fixed in time or space but rather are subject to constant interpretation and renegotiation by people as part of their lifeworld (Cummings Reference Cummings2012; Ingold Reference Ingold2007; Krzywoszynska & Marchesi Reference Krzywoszynska and Marchesi2020).

Integration of Indigenous and archaeological knowledge systems is increasingly advocated for (McNiven Reference McNiven2016), yet practical examples of such integration in material analysis remain limited. This reflects archaeology’s colonial foundations and history of privileging Western scientific frameworks over Indigenous ones (Atalay Reference Atalay2006; Bradley Reference Bradley2022, 23; McNiven & Russell Reference McNiven, Russell, Bentley, Maschner and Chippindale2007; Watson Reference Watson2014, 71). By ignoring the interconnectedness of Indigenous ways of knowing, archaeologists risk becoming complicit in ignoring their existence (Hill Reference Hill2016, 14). In response, we adopt a pluralist approach that acknowledges multiple ways of knowing can co-exist without needing to be reduced to a singular truth (Brady & Kearney Reference Brady and Kearney2016, 633; Brady et al. Reference Brady, Bradley and Kearney2024, 295; Chang Reference Chang2012, 261).

It has been said that for Indigenous Australians ‘life doesn’t move through time, time moves through life’ (Kwaymullina Reference Kwaymullina2020, 21). We recognize that ancestral actions are simultaneously ‘present, observable, and important’, rather than confined to a linear past (Kearney et al. Reference Kearney, Bradley and Brady2020, 74). The past can be ‘regenerated’ through recognition of relationships between people and their ancestors (Bradley Reference Bradley2022, 24). With such an approach the ‘past’ then becomes active, capable of revealing or concealing itself to people existing in the ‘present’ (Brady & Kearney Reference Brady and Kearney2016, 652). This challenges us to consider the ongoing processes of engagement between people and things, not as an absolute rejection of linear time but as an attempt to bridge multiple ways of knowing and produce an interpretation which aligns with Aboriginal concepts of time and presence.

These issues considered, our analysis of the mound and its stone artefacts is guided by three key theoretical principles:

-

1. Relational Materiality: archaeological features and materials are not passive records of past activities but active participants in ongoing relationships.

-

2. Knowledge Integration: we seek to work productively in the space between different knowledge systems, recognizing that multiple understandings can exist simultaneously without requiring resolution into a single narrative.

-

3. Temporal Simultaneity: rather than viewing archaeological deposits as static records of past events, we recognize how features like the mound represent ongoing processes of engagement with Country that challenge the boundaries of linear time.

Walanjiwurru 1 rock-shelter

Located within Limmen National Park, Walanjiwurru 1 is a sandstone rock-shelter positioned on a high sandstone outlier that provides expansive views over the savannah plains below (Fig. 4). The site is part of the Mambali Clan estate (one of four Marra clans, the others being Murrugun, Budal and Guyal) and was created by the Karrimala Ancestral Beings on their travels north towards their resting place along the Limmen River (Fig. 2).

Figure 4. Walanjiwurru 1 rock-shelter. (Photograph: Liam M. Brady.)

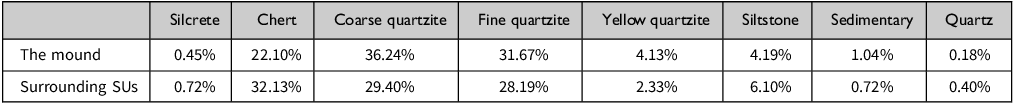

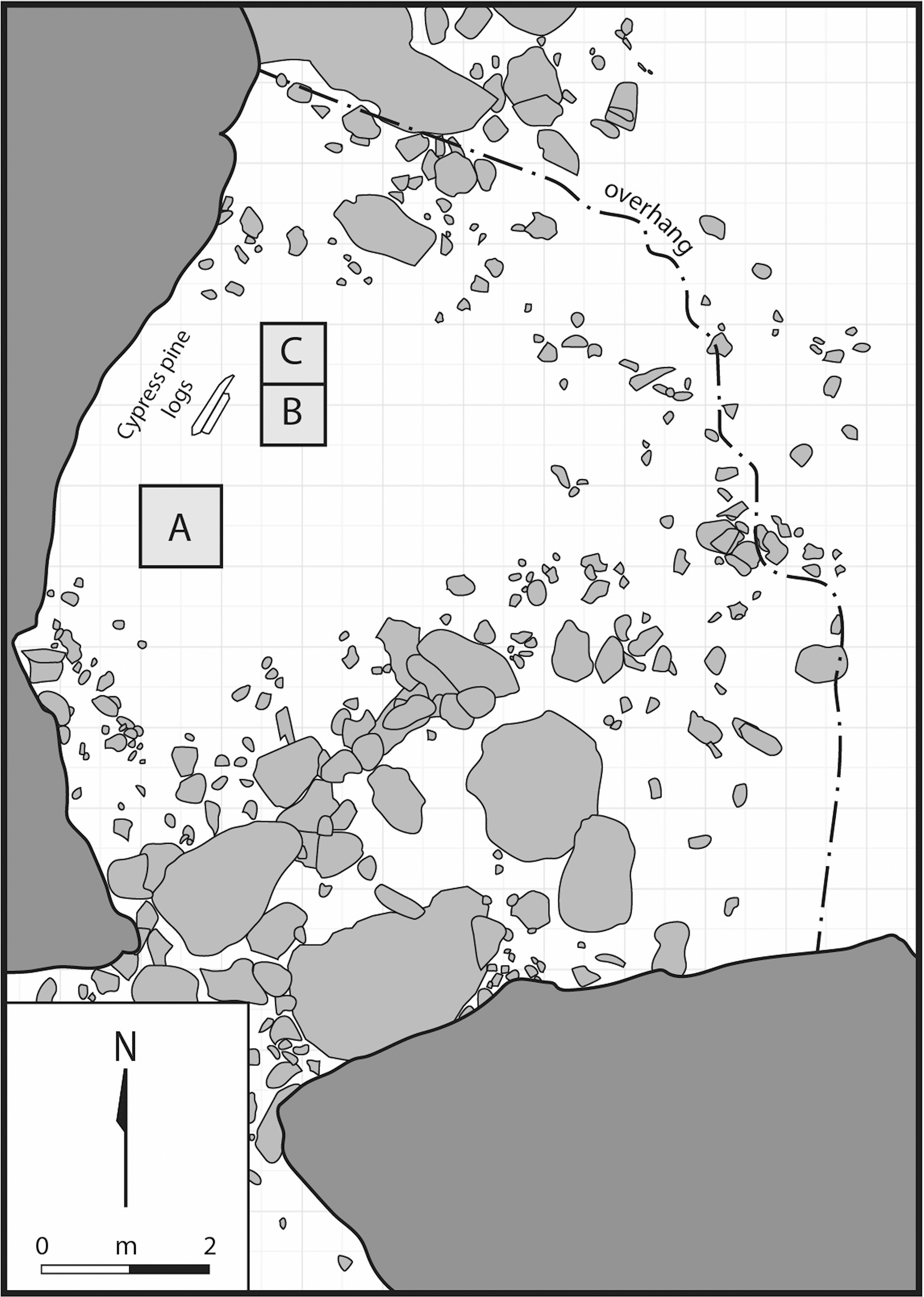

The shelter measures 7 m deep from rear wall to dripline and 10 m wide between side walls, with a maximum ceiling height of 5 m at the dripline. The floor consists of undulating, loose sandy sediment and small cobbles, with large sandstone blocks occurring at the shelter front and sides from localized wall and ceiling collapse (Fig. 5). A cascade of large sandstone blocks at the southernmost end created a second smaller entrance following a major rock-collapse event. Rock art adorns all three walls, connecting the shelter to broader artistic traditions in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Bradley and Wesley2019).

Figure 5. Walanjiwurru 1 main overhang and site of excavation squares. (Photograph: Liam M. Brady.)

Initial archaeological investigation of Walanjiwurru 1 began in 2019 with excavation of Square A (75×75 cm). This work established the site’s basic chronological sequence, with deposits extending from the early twentieth century to approximately 2300 years ago (Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022). These investigations revealed well-stratified cultural deposits including stone artefacts, botanical remains and evidence for long-term management of the local environment (Rowe et al. Reference Rowe, Ash, Brady, Wesley, Evans and Barrett2023; Walsh et al. Reference Walsh, Dotte-Sarout and Brady2024). Analysis of the stone assemblage from Square A demonstrated connections to all three major quarry sites in Marra Country, with distinctive patterns in the distribution of different stone types (Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022).

JA, LMB, DW, SE and DB returned to the site in July 2022 to determine if other parts of the shelter would reveal similar or different chronological sequences. Two new squares (B & C, each 75×75 cm) were positioned adjacent to the original excavation (Fig. 6). Here they encountered the distinctive mound of stone artefacts at the base of Square B (Fig. 7). Detailed analysis of sediments, radiocarbon-dating chronology and remainder of the cultural assemblage from Squares B & C will be reported elsewhere.

Figure 6. Site plan of Walanjiwurru 1 rock-shelter. (Drawing: Jeremy Ash and Bruno David.)

Figure 7. The stone artefact mound (outlined) as it appeared in situ, demonstrating its mounded appearance and high concentration of artefacts. (Photographs: Liam M. Brady.)

Methods

A. Archaeological methods

Field methods

Squares B and C (75×75 cm each) were positioned approximately 1 m northeast of Square A. The squares were excavated in 52 arbitrarily sized excavation units (XUs), averaging 1.4 cm in thickness and following the natural stratigraphy to a maximum depth of 77.3 cm. A dumpy level was used to measure end elevations for each XU to maintain vertical control. All excavated deposit was dry-sieved through 2 mm mesh on site, with retained materials bagged and transported to laboratory facilities for further processing.

The mound was first identified at XU33, approximately 39 cm below datum (Fig. 15, below). Given its distinct nature, characterized by a high density of stone artefacts and charcoal compared to surrounding deposits, it was designated as subXUf and excavated separately from surrounding matrices. Bulk sediment samples were collected from each XU for soil analyses.

In situ charcoal samples for radiocarbon dating were plotted in three dimensions, collected with handheld mini trowels and placed within sterile plastic tubes to prevent contamination. Samples were selected from secure contexts within both the mound and surrounding deposits, with priority given to samples showing minimal evidence of post-depositional movement. AMS dating was conducted at Waikato Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory, with dates calibrated using OxCal v4.4 and the SHCal20 calibration curve.

Laboratory methods

Initial processing involved wet-sieving all excavated material through 2 mm mesh, followed by air drying and preliminary sorting of cultural materials. Stone artefacts were cleaned using soft brushes and water where necessary, with particular attention paid to preserving edges and surfaces for subsequent analysis. Two size categories were established using laboratory sieves: >4 mm and <4 mm.

B. Analytical framework

Stone type classification

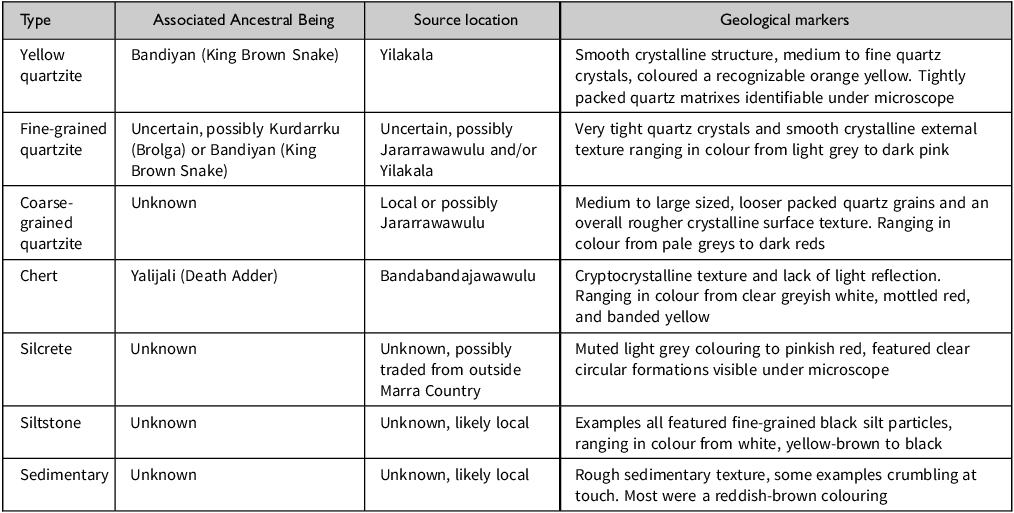

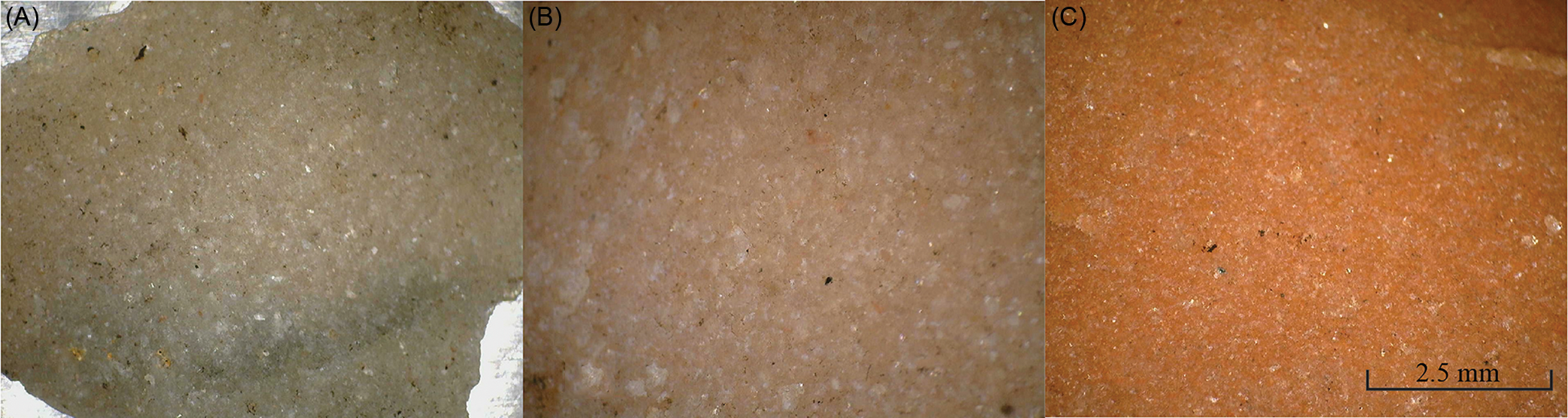

Our analytical approach required balancing geological distinctions typically used in archaeological analyses with Indigenous knowledge of the places where certain stone types could be found, the Ancestral Beings associated with their creation, and any information regarding their quality and properties. Six main categories were established: fine-grained quartzite (Fig. 8), coarse-grained quartzite (Fig. 9), yellow quartzite (Figs 10 & 11), chert (Fig. 12), silcrete (Fig. 13) and siltstone (Fig. 14) (Table 1).

Figure 8. Microscopic images of fine grain quartzite: (A) artefact ID XU35F_fgquartzite_5; (B) artefact ID XU35F_7; (C) artefact ID XU35F_fgquartzite_11. (Photographs: Hugh Cowie.)

Figure 9. Microscopic images of coarse grain quartzite: (A) artefact ID XU35F_cgquartzite_118; (B) artefact ID XU35F_cgquartzite_119; (C) artefact ID 35F_cgquartzite_120. (Photographs: Hugh Cowie).

Figure 10. Microscopic images of yellow quartzite: (A) artefact ID XU35F_exquartzite_14; (B) artefact ID XU35F_exquartzite_2; (C) artefact ID XU35F_exquartzite_3. (Photographs: Hugh Cowie.)

Figure 11. (A) Macroscopic image of Bradley’s Yilakala stone; (B) microscopic image of Bradley’s Yilakala stone. (Photographs: Hugh Cowie.)

Figure 12. Microscopic images of chert: (A) artefact ID XU35F_chert_96; (B) artefact ID XU35F_chert_41; (C) artefact ID XU35F_chert_92. (Photographs: Hugh Cowie.)

Figure 13. Microscopic images of silcrete: (A) artefact ID XU35F_silcrete_1 (B) artefact ID XU35F_silcrete_2; (C) artefact ID XU35F_silcrete_2. (Photographs: Hugh Cowie.)

Figure 14. Microscopic image of siltstone: (A) artefact ID XU35F_siltstone_8; (B) artefact ID XU35F_siltstone_12; (C) artefact ID XU35F_siltstone_15. (Photographs: Hugh Cowie.)

Table 1. Stone type classification criteria incorporating Marra knowledge of stone sources.

Identification of the yellow quartzite was particularly significant, given its cultural associations with Yilakala. Classification was based on previous work by Jerome Milanes for Square A and comparison with reference specimens, including a quartzite stone tool that would have been mounted on a curved stick to make a binymala (handaxe/chisel), provided to JB by senior Marra man Dulu Burranda, who was jungkayi for Yilakala (Fig. 11) (Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022). This integration of classification systems enabled recognition of relationships between stone types and Ancestral Beings that might otherwise have been overlooked.

Size classification

All stone artefacts were divided into two size classes using a 4 mm sieve. The <4 mm artefacts were not individually analysed in this study but were included in overall assemblage counts where specified. All >4 mm artefacts were individually measured from photographs using a combination of Adobe Photoshop and a Python-based program designed by JA. Photos were taken on an iPhone X by HC, against a black cotton cloth background to reduce lamp flare, with an IFRAO scale with colour standard, and a fixed stand for the camera to rest on. The program had an average error margin of <1 mm which was deemed acceptable considering the aims of the project to identify general trends and patterns in size distribution.

Spatial analysis distribution

Distribution patterns were analysed across three spatial domains: within the mound, outside the mound (surrounding SUs),and along the vertical sequence. This analysis examined stone type frequencies and distributions, size-sorting patterns, temporal changes in deposition and evidence for selective placement or movement of stone materials. Statistical analysis focused on identifying significant patterns in the distribution of different stone types and size classes between the mound and surrounding SUs.

Results

A. Archaeological results

Stratigraphy

Excavation of Squares B and C revealed seven major stratigraphic units (SUs), each consisting of loosely consolidated sandy quartz matrices with slight visible differences in colour and compaction (Fig. 15). The upper units (SU1 to SU3) are charcoal-rich and dark brown-black, indistinctly grading into one another. The lower units (SU4 to SU7, except SU6) are lighter in colour, tending to lighter browns, though charcoal remains common throughout.

The mound (SU6) represents a distinct deposit between thin underlying deposits (SU7) and overlying/surrounding units (SU4 and SU5). It consists primarily of a dark grey-brown and charcoal-rich matrix, distinguished from surrounding sediments by its high density of stone artefacts and charcoal. The sloped exterior of the mound and how SU4 and SU5 wrap around it indicate it was a visible feature during the shelter’s use, with these units forming around it (Fig. 15).

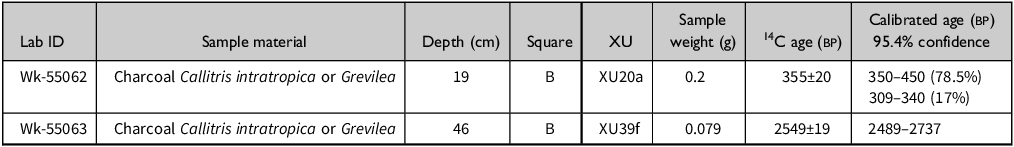

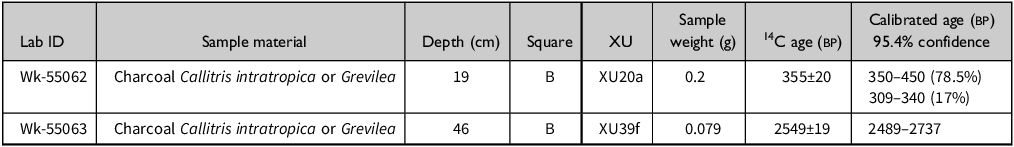

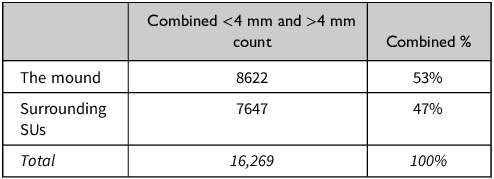

Chronology

Two accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dates were obtained from individual pieces of charcoal (Table 2): one from above the mound in SU2b [Wk-55062] and one from within the mound in SU6 [Wk-55063]. The sample from SU2b (XU20a) returned a date of 355±20 bp (calibrating to 350–450 cal. bp), and the sample from approximately the vertical midpoint of the mound (XU39f) returned an age of 2549±19 bp (calibrating to 2489–2737 cal. bp).

Table 2. Details of AMS dates from Square B, Walanjiwurru (OxCal v4.4; Southern Hemisphere atmospheric data: Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Heaton and Hua2020).

These dates align with phased occupation history established for the nearby Square A (Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022, 8), where Phase 1 spans 2339–2136 cal. bp and Phases 2 and 3 represent the upper units (493 cal. bp to present). While the SU2b date corresponds with Phases 2 and 3, the SU6 date extends the site’s chronology approximately 200 years earlier than previously documented. However, the potential for mixing of materials within SU6 means this date could reflect either the mound’s formation or an earlier event incorporated during sweeping activities. The wrapping of SU5 and SU4 around SU6 (Fig. 15) also makes the intriguing implication that the mound was a positive feature which endured on the rock-shelter surface for some time after the single date we have obtained.

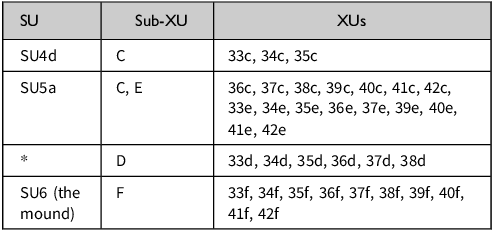

Stone assemblage composition

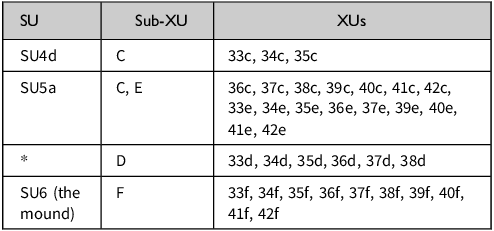

Our analysis was based on a comparison between two groups of SUs (Table 3) referred to as;

-

The mound—SU6 (recorded during excavation as sub-XUf)

-

Surrounding SUs—SU4d, SU5a, SU7 (recorded during excavation as sub-XUc, sub-XUd, sub-XUe)

Table 3. Breakdown of the sub-units used to group the artefacts under discussion.

*Sub-XUd was backplotted against the west wall, where the microstratigraphy was very difficult to identify due to issues with lighting and soil colouration, but is associated with SU4 and SU5.

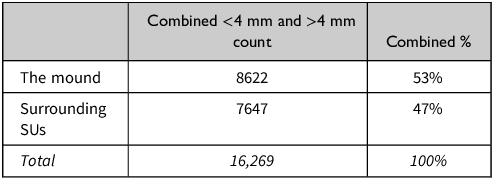

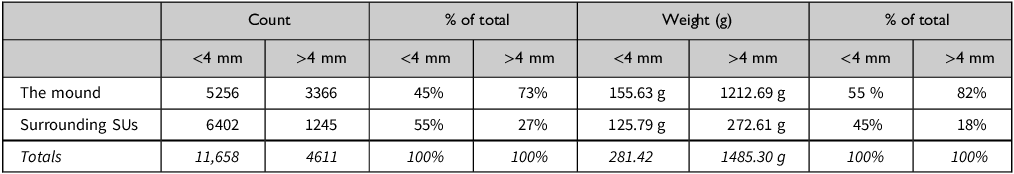

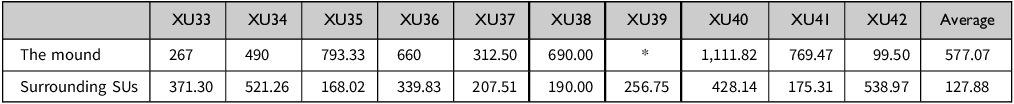

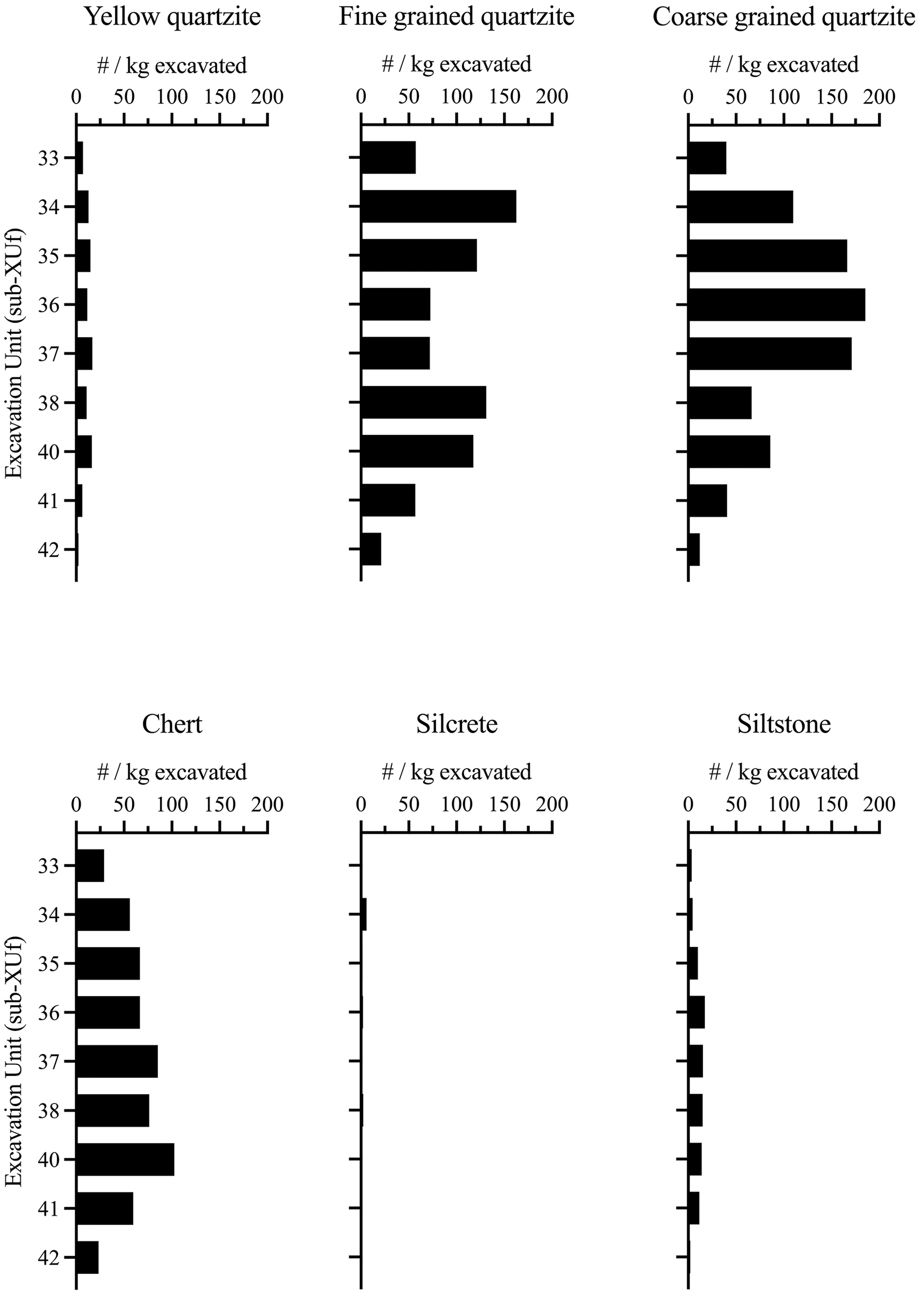

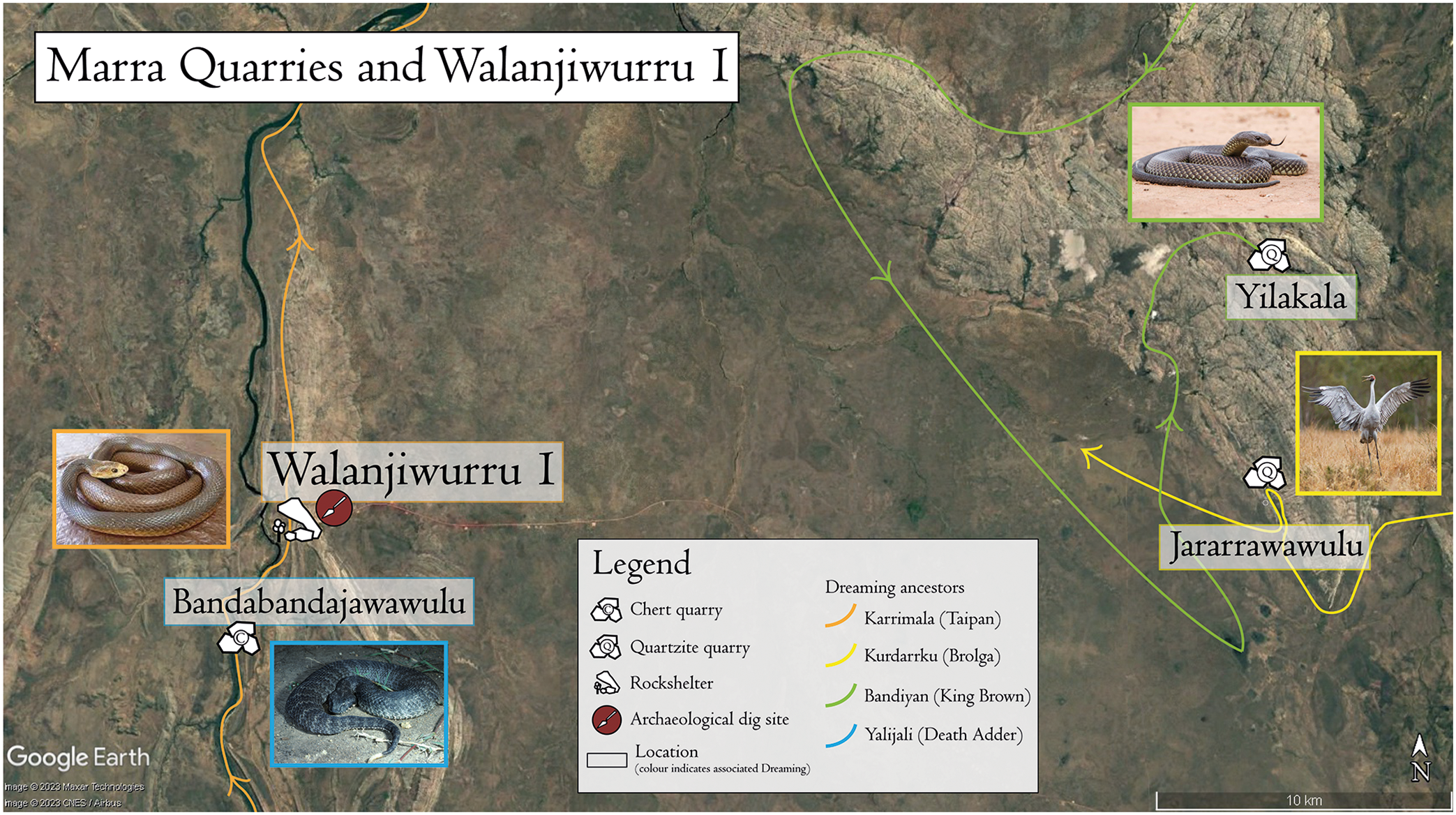

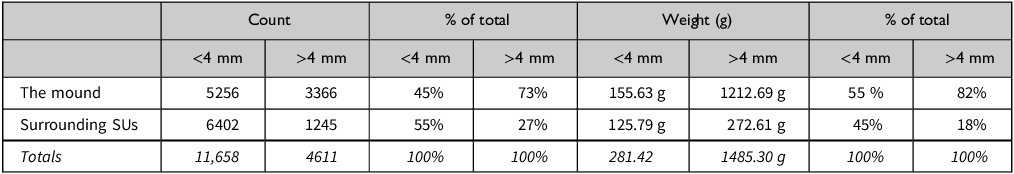

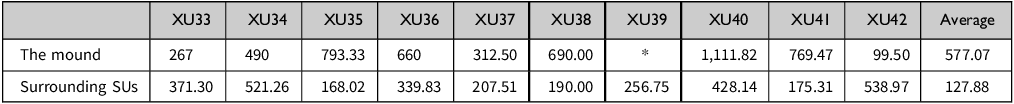

Analysis of 16,269 stone artefacts excavated from XU33–XU42 revealed distinct patterns in both distribution and composition of materials between the mound and surrounding SUs (Tables 4 & 5). The mound contained 73 per cent of all >4 mm stone artefacts analysed and 82 per cent of total stone artefact weight. Of 4611 artefacts >4 mm in size, 3366 were recovered from the mound, with 1245 from surrounding SUs. When standardized by weight of excavated sediment, the mound showed significantly higher density, averaging 577.07 artefacts per kg compared to 127.88 artefacts per kg in surrounding SUs (Table 6).

Table 4. Total counts of stone artefacts from within the mound in comparison with the surrounding SUs.

Table 5. The counts, weights and percentages of artefacts <4 mm and >4 mm in size from the mound and surrounding SUs.

Table 6. Standardized amounts of artefacts per kg of excavated deposit (all size classes).

*XU39f did not have an excavated weight recorded on the excavation forms.

Distribution patterns for <4 mm materials show a markedly different pattern. The surrounding SUs contained 55 per cent of <4 mm artefacts (n=6402) compared to 45 per cent (n=5256) in the mound, suggesting different factors influencing distribution of the smallest artefacts.

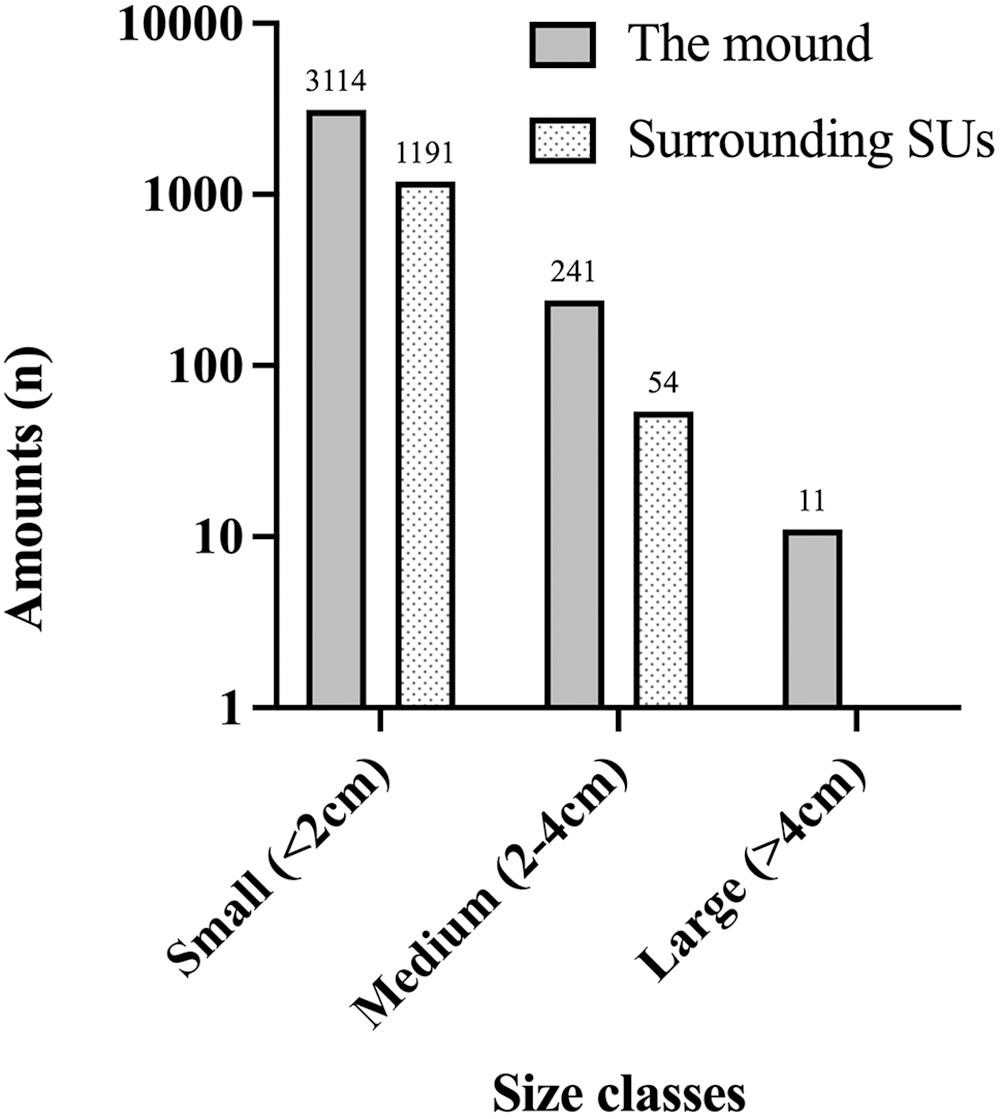

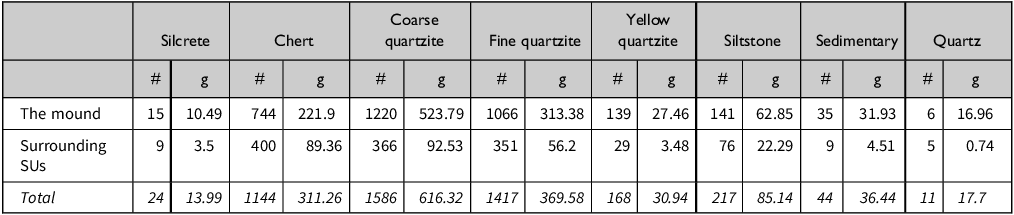

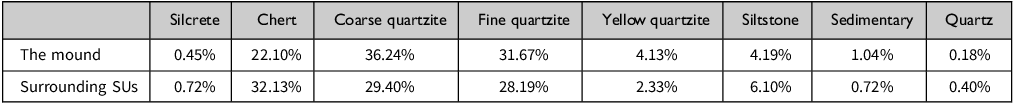

Stone type distribution

Analysis of stone type distribution reveals distinct patterns between the mound and surrounding SUs. While all stone types found in the mound also occurred in surrounding SUs, their proportions differed significantly.

Within the mound, coarse-grained quartzite dominated the assemblage (36.24 per cent, n=1220), followed by fine-grained quartzite (31.67 per cent, n=1066) and chert (22.10 per cent, n=744). Most notably, of the total yellow quartzite excavated (n=168), 82.7 per cent (n=139) was concentrated within the mound.

This distribution differs notably from surrounding SUs, where chert comprises a higher proportion (32.13 per cent) and yellow quartzite appears less frequently. The high proportions of quartzites and cherts reflect the availability of these materials at nearby quarry sites: Bandabandajawawulu (chert), Jararrawawulu and Yilakala (quartzites).

Size distribution analysis

Size distribution analysis demonstrates evidence of selective deposition. While <4 mm artefacts showed relatively even distribution between the mound and surrounding deposits, the mound contained 73 per cent (n=3366) of all >4 mm artefacts. This pattern becomes more pronounced with increasing artefact size. Of the 306 artefacts exceeding 20 mm in length, 252 (82 per cent) were found within the mound (Fig. 16). This includes all formal tools recovered during excavation: seven points manufactured from fine-grained quartzite and chert and four cores showing systematic reduction patterns (Fig. 17).

Figure 15. Section drawing of the east wall of Squares B and C, Walanjiwurru 1, highlighting the mound (SU6) with XUs and 14C samples superimposed. Note the draping of SU4/5 over SU6 (the mound, outlined) indicating its possible visibility over an extended time period. Scales indicate depth below datum in centimetres (cm). (Drawing: Jeremy Ash and Bruno David.)

Figure 16. Distribution of >4 mm artefacts (n) by small, medium, and large size classes (cm) within the mound versus outside the mound. The lack of large artefacts outside the mound reflects observations of size sorting in previous studies of sweeping. Amounts of individual size classes are listed above each bar. (Graph: Hugh Cowie.)

Figure 17. Examples of formal artefacts found within the mound: (a) artefact ID 36F_cgquartzite_9, broken unifacial point; (b) artefact ID 39F_chert_1, small bifacial point; (c) artefact ID 36F_cgquartzite_1, used core. (Photographs: Hugh Cowie.)

Vertical changes in stone types

Vertical analysis indicates changes in stone type proportions through the deposit. The interface between SU4d and SU5a corresponds with shifts in material composition, particularly visible in the proportions of coarse-grained quartzite. In SU5a, coarse-grained quartzite comprises 42.3 per cent (n=567) of the assemblage, while in SU4d this decreases to 31.8 per cent (n=428). A notable change occurs at XU38f, where coarse-grained quartzite decreases from 36.24 per cent to 22.15 per cent, concurrent with the stratigraphic change observed in surrounding deposits (Figs 15 & 18).

Figure 18. Distribution of stone types by excavation unit (XU) within the mound. Note the shift in material composition in XU36–37 between fine- and coarse-grained quartzites, aligning with stratigraphic change between SU4 and SU5. (Graph: Hugh Cowie.)

B. Results: cultural context of the archaeological patterns

Stone types and sources

The stone assemblage from Walanjiwurru 1 includes materials from three main quarry sites in Marra Country: Bandabandajawawulu (chert), Jararrawawulu and Yilakala (quartzites). The yellow quartzite from Yilakala is disproportionately represented in the mound compared to surrounding SUs. Access to these quarry sites is governed by specific protocols under Marra Law, with Yilakala requiring particular care due to its powerful ancestral associations (see above).

Distribution patterns and site maintenance

Size distribution patterns across the assemblage (Table 5; Fig. 16) correspond with previous archaeological, micromorphological and ethnographic observations of material accumulation through sweeping (Alzate-Casallas et al. Reference Alzate-Casallas, Sánchez-Carro, Barbieri and González-Morales2024; Bradley Reference Bradley1997, 386; Hayden & Cannon Reference Hayden and Cannon1983; Lampert & Steele Reference Lampert and Steele1993). In the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, such practices have a combined practical and spiritual purpose of maintaining relationships with Country (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017, 71). Bradley (Reference Bradley1997, 386) documented comparable practices of intentional mounding of dugong bone through sweeping, noting how these activities contributed to ongoing ancestral relationships with Country. While there is no detailed ethnographic documentation of sweeping rock-shelters in Marra Country, similarities of our archaeological data to other studies of sweeping internationally combined with recorded sweeping practices from close neighbouring groups, and knowledge of how Marra care for Country, indicates strong evidence for sweeping at Walanjiwurru 1.

Formation sequence

Vertical distribution of materials indicates multiple formation events, evidenced by changes in stone type proportions between SU4d and SU5a (Fig. 15). These changes are consistent with broader patterns of long-term site maintenance documented in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, where regular cleaning practices form part of continuing connections to Country (Hill Reference Hill2016, 46–58). The presence of all formal tools within the mound context, rather than in surrounding deposits, also suggests a deliberate placement of certain materials over time. Alternative processes, such as episodic dumping from hearth rake-out or purposeful discard, could also contribute; however, the observed size sorting, exclusive association of formal tools with SU6 and the stratigraphic wrapping of SU4/5 around a pre-existing mound favour a maintenance (sweeping) origin.

Discussion

Our interpretation treats sweeping as the best-supported process given the combined presence of strong concentration of larger and formal artefacts in SU6, more even dispersal of <4 mm material in surrounding SUs, and SU4/5 draping around a pre-existing rise. While episodic discard and hearth rake-out likely contributed some fraction of the assemblage, we propose the patterning aligns most closely with a maintenance (sweeping-plus-selective-placement) model. Guided by our three theoretical principles of relational materiality, knowledge integration, and temporal simultaneity, we now discuss how the mound expresses ongoing relationships between people, materials, and Country maintained through the practice of sweeping.

The power of stone

The disproportionate representation of yellow quartzite within the mound reflects broader patterns of power and management in Marra Country. This raw material’s connection to powerful Ancestral Beings at Yilakala imbues it with particular significance, requiring careful management even in maintenance practices. It appears to have been much less common amongst the malbumalbu than other quartzites, and most of what was worked at the site has been carefully moved into the mound. Interestingly, no formal artefacts of this stone type were found in the mound or surrounding SUs (or in Square A: see Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022), suggesting the heightened value placed on yellow quartzite in comparison to other stone types. Ultimately, the concentration of this stone within the mound suggests the malbumalbu were actively managing powerful materials through established practices of site maintenance.

Overall, quartzites appear to have been preferred by the malbumalbu, even with an easily accessible chert quarry nearby to the rock-shelter (Bandabandajawawulu: Fig. 2). Ethnography from Marra Country (see above) suggests that this was primarily due to their connections with Ancestral Beings and the power this afforded them. Elsewhere in northern Australia importance is placed on the visible brightness of quartzite due to its association with ancestral beings, blood and life force (Morphy Reference Morphy1989, 30; Taçon Reference Taçon1991, 198–9). These links also exist in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, where shininess is associated with Ancestral Beings, indicating life and power (see Bradley Reference Bradley, David and Thomas2008). The visual quality of shininess is also linked with fat, which as discussed above, represents life force and vitality and is conceptually linked with working stone into stone tools. Due to these factors stones in Marra Country carry the power of their Ancestral Being creators, connecting ‘sources of power across the landscape’ (Ash et al. Reference Ash, Bradley and Mialanes2022, 15). Therefore, Walanjiwurru 1 and its stone artefacts can be seen as making up a small part of an expansive ‘lifeworld saturated with meaning’ (Moore & Thompson Reference Moore and Thompson2012, 280). With a relational approach to stone, the interconnected nature of Country and Law is made apparent and provides deeper meaning to the mound.

The moral responsibility of sweeping and being

For Aboriginal people today, arrangements of material such as stone, shell and bone are meaningful and can evoke memory of ancestral activity (Ross Reference Ross2008; Hiscock & Faulkner Reference Hiscock and Faulkner2006, 215). In the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, Bradley (Reference Bradley1997, 386) documented how carefully swept mounds of dugong bones became ‘quiet source[s] of pride’ of one’s connections to past ancestors. Likewise in the Torres Strait, mounded shell and bone material is expressive of Goemu connections to their landscapes and seascapes (McNiven Reference McNiven2013, 576). Such examples are embedded within an intellectual framework that prioritises the coevality of past and present. They make up part of Law, Country and family, which, for senior Yanyuwa and Marra woman Annie Karrakayny, is “still there, still with me” (pers. comm. to JB, 2000). Therefore, ancestral actions are a constant reminder of the co-presence of people with ancestral influences and activity (Kearney et al. Reference Kearney, Bradley and Brady2020, 74). This understanding of temporality creates a responsibility for people to consider their actions as their effects ‘radiate out’ across time (Kwaymullina Reference Kwaymullina2020, 21). Thus, we might say there is a morality to what might be called the ‘past’ as ancestral presences and Country continue to be negotiated. This understanding helps explain the archaeological evidence for repeated maintenance at Walanjiwurru 1 and its continuing significance.

Sweeping can be considered an ‘obligation and moral duty’ as part of keeping Country clean (Kearney Reference Kearney2009, 326). The cleaning of material from the wider area into a concentrated mound can be seen as part of how people maintain and establish order in the world around them (Reader Reference Reader, Martinez and Van Bremen1994, 228). The sweeping of a campsite is a daily activity encompassing both the physical and spiritual wellbeing of Country, and our results reflect this dual purpose (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017, 71). The concentration of larger artefacts (>4 mm) within the mound, combined with a more even distribution of smaller flakes in surrounding SUs, suggests deliberate cleaning activities at Walanjiwurru in which the malbumalbu sought to order, clean and maintain their Country. These distribution patterns align with previously identified indications of sweeping (Lampert & Steele Reference Lampert and Steele1993, 64; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Conard, Goldberg and Berna2010, 33; O’Connell Reference O’Connell1987, 82). Furthermore, careful treatment of different stone types, particularly those connected to powerful Ancestral Beings, indicates this was not purely functional cleaning but part of maintaining proper relationships with Country.

Evidence for multiple formation events in the mound, combined with careful treatment of significant stone types, suggests sweeping at Walanjiwurru 1 represents an ongoing process of engagement with Country. Stratigraphic evidence indicates repeated maintenance activities over time, while concentration of formal tools within the mound context suggests deliberate placement rather than random accumulation. Indeed, the stratigraphy and radiocarbon dating suggest the mound remained above the ground surface for many years after its initial creation and was likely visible to those who returned to camp there in subsequent years. Thus, it could be interpreted as both a tangible testament to the efforts of the malbumalbu to maintain their camp and a visible reminder of the importance of cleaning Country over time.

Relational materiality

The Walanjiwurru 1 mound demonstrates how archaeological features can be understood through what we term ‘relational materiality’, where materials actively participate in maintaining relationships between people, ancestors and Country. In doing so, they have the potential to stretch the boundaries of linear time, expressing relationships with an ancestral past which is simultaneously of a time long ago and still ‘present, observable, and important’ (Kearney et al. Reference Kearney, Bradley and Brady2020, 74; and see Kwaymullina Reference Kwaymullina2020, 19–21).

This challenges other archaeological approaches that view maintenance features primarily through functional frameworks. However, the distinction between functional and symbolic aspects only arises when measured against modern Western understanding, which tends to classify things within dichotomous pairs and ‘renders invisible’ that which defies translation into this system (Vázquez Reference Vázquez2011, 28). For Marra people, stone sources are places of combined importance which cannot be meaningfully separated, encompassing symbolism, politics, spirituality, economics, and more. The same is true for the stone originating from these places. An encounter with specific stone types which carry this meaning therefore calls about a negotiation of relationships, thus maintaining connections between people, ancestors and Country. This integration of meaning extends to maintenance practices, where sweeping simultaneously maintains physical cleanliness and spiritual well-being.

The evidence supports a relational perspective in multiple ways. First, selective treatment of stone types, particularly concentration of yellow quartzite from Yilakala, demonstrates how materials are understood and managed according to their ancestral ngalki (essence) and power. This power is attributed to ancestral forces, both malevolent and benevolent, inherent to the material itself, giving it the agency to demand selective treatment as it exists in-relation to people around it. Our observed distribution patterns of stone type (Tables 7 & 8), size (Fig. 16) and typology (Fig. 17) match this pattern. Second, repeated formation events visible in the stratigraphy show how maintenance practices were not simply practical activities but relational processes of engagement between people, stone and Ancestral Beings.

Table 7. Counts (#) and weights (g) of stone types included in analysis.

Table 8. Percentages of stone type counts within the mound and surrounding SUs.

This understanding of materials as active agents in maintaining relationships helps explain two key patterns in our results:

-

Spatial Organisation: concentration of larger artefacts and formal tools within the mound, careful placement of powerful stone types, and creation of distinct maintenance areas within the shelter.

-

Temporal Patterns: evidence for multiple formation events, changes in stone type distributions over time, and continuing significance of the deposit as the mound endured over time.

Expressions of meaning

The activities of sweeping and mounding are part of a larger process of living, or being, on Country. Places and the Ancestral Beings who reside within them have multiple layers of meaning and are part of a political landscape which traces back to the time of creation (Kearney et al. Reference Kearney, Bradley and Brady2020, 73). Even sweeping has a ‘dual meaning’ of not just tidying in a Western sense but also in a deeper sense of maintaining a clean, healthy Country (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Bradley and Standfield2017, 17). The presence of the sweeping mound at Walanjiwurru 1 means people cared about keeping their living spaces clean, and they did so at multiple points over time. Therefore, sweeping can be understood as a means of maintaining strong connections between people and Country, as a poorly looked-after Country risks becoming ‘wild’ and dangerous. By exploring the mound in such a way, we propose it represents not just a source of archaeological information, but an expression of the deeply complex Marra way of being that is continuously engaged in hyper-relational negotiations of kinship, Law and Country.

The flow chart (Fig. 19) attempts to demonstrate the various threads comprising the history of the mound and its stone artefacts. It provides an overview of the processes which our exploration of the mound has revealed, including important social factors which would have influenced their linked stages. In this chart we present the story of the mound in a way that demonstrates the importance of the relational in understanding the layers of meaning, interaction and socio-politics forming its history.

Figure 19. Flow chart showing the expanded history of the mound. Orange boxes represent major events that would have occurred during the mound’s formation and lifespan, with interconnected white circles containing influential factors in those important stages, demonstrating how Marra knowledge of Law and Ancestral Beings is integral to our interpretation. Light-yellow boxes contain the archaeological evidence that guided our interpretation.

Broader implications for archaeological practice

While traditional approaches to investigating site formation may view maintenance features as secondary evidence of primary activities, our results demonstrate how such features can instead be understood as primary evidence of ongoing relationships with Country. Careful treatment of different stone types at Walanjiwurru 1 shows how materials themselves can be understood as active participants in social relationships rather than passive objects of human action. Moreover, the evidence for repeated formation events, combined with Marra understandings of time and presence, suggests we need to reconceptualize how we think about archaeological temporality.

These findings point toward several productive directions for future research. First, the investigation of maintenance features as evidence of continuing cultural practice rather than simply site-formation processes. Second, development of methodologies that better integrate Indigenous knowledge systems with archaeological evidence. Finally, exploration of how materials actively participate in maintaining connections between past and present.

Conclusion

For Marra people, stone carries a depth of significance extending beyond its utilitarian functions, even if it has not been used for tools in decades. As Jones and White (Reference Jones, White, Meehan and Jones1981, 84) rightly state, ‘to miss this would be to miss the point’.

This study demonstrates how methodological choices that respect different knowledge systems can reveal complex relationships between people, materials and Country. Integration of archaeological and Marra knowledge systems not only provided deeper understanding, but also suggested new ways of approaching archaeological features. Our analysis of the Walanjiwurru 1 stone artefact mound has demonstrated three key findings:

-

1. The integration of practical and spiritual aspects in site maintenance, where sweeping practices simultaneously serve functional purposes and maintain Country.

-

2. The continued significance of stone in Marra philosophical framing, rooted in the creative actions of Ancestral Beings who imbue stone with their essence, thus determining its position in the relational lifeworld of Marra Country.

-

3. The value of integrating archaeological and Indigenous knowledge systems, which together provide a deeper understanding of cultural practices and their material traces, and enabled recognition of relationships between people and stone artefacts that might otherwise have been overlooked.

While some specific knowledge about stone-working has transitioned over time, broader frameworks of understanding stone’s power and proper management remain active. These frameworks demonstrate how quarries and stone materials participate in networks of social, political and spiritual relationships that continue to shape archaeological practice in Marra Country.

Stone tools retain the essence of Ancestral Beings who created them and can evoke memory of the people who used them (see Bradley Reference Bradley, David and Thomas2008). Therefore, stone tools remain active within Country as expressions and reminders of the actions of ancestors who are both past and present. The sweeping mound we have explored is one such reminder, and we have attempted to capture a sense of the wider history that can be drawn from this assemblage. While many of us trained in an empirical tradition may feel the urge to pull apart these threads to discern an ‘absolute truth’, we propose the uncertainty that exists in the space between co-existing knowledges is not one that should be avoided, but one that we as academics should be comfortable in exploring (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Bradley and Kearney2024, 295). It is in this space where truly methodologically open practice must exist to produce deeper, more meaningful interpretations, not just in stone artefact studies, but in archaeology more broadly.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Marra Families past and present for their help with this research and generously sharing their knowledge about the sites discussed in this paper. Fieldwork was supported by Marra Families and Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory, in particular Glenn Durie (Manager, Capacity Building and Aboriginal Engagement). Thanks also to Jerome Mialanes for sharing his specialist advice on stone tools from the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, and to Bruno David for his help in producing site plans and drawings. This research is funded by the Australian Research Council (DP170101083, FT180100038, LP220100143).