1. Introduction

The dark-matter halo-mass represents one of the most fundamental properties governing galaxy evolution within the hierarchical structure formation paradigm; as galaxies form and evolve within these gravitationally bound dark matter structures, the halo mass strongly influences numerous galaxy properties including star formation histories, morphologies, and chemical enrichment pathways (White & Rees Reference White and Rees1978; Blumenthal et al. Reference Blumenthal, Faber, Primack and Rees1984; Bower et al. Reference Bower2006). Accurate determination of halo masses therefore underpins our ability to connect theoretical models of structure formation with observational constraints on galaxy evolution across cosmic time.

Given the importance of halo mass in the field of galaxy evolution, accurate measures of halo mass are critical; however, it remains challenging to measure directly for individual groups. Weak gravitational lensing provides accurate and widely adopted halo mass estimates, and is routinely used to validate indirect estimators (Leauthaud et al. Reference Leauthaud2012; Hoekstra et al. Reference Hoekstra2013; Velander et al. Reference Velander2014; Mandelbaum et al. Reference Mandelbaum2016; Mandelbaum et al. Reference Mandelbaum2018). Nonetheless, robust weak-lensing halo masses for individual galaxy groups are not universally available at typical survey depths, as the per-object signal-to-noise at group-scale masses is often insufficient without stacking or targeted deep imaging (Leauthaud et al. Reference Leauthaud2012; Velander et al. Reference Velander2014; Viola et al. Reference Viola2015; Simet et al. Reference Simet2017). Other indirect probes include X-ray emission from hot gas (e.g. Arnaud et al. Reference Arnaud2010) and galaxy dynamics (e.g. Old et al. Reference Old2014); these can be applied to individual groups, but carry method-specific systematics that are particularly pronounced in low membership groups. This regime is crucial for tracing the growth of structure within group environments and for understanding the transition from group to cluster environments (Yang et al. Reference Yang2007; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011). Current approaches to estimating halo masses face several challenges: weak lensing signals become increasingly difficult to detect for lower-mass systems (Viola et al. Reference Viola2015), while X-ray observations require the presence of hot gas in hydrostatic equilibrium; a condition typically not met in group-scale environments (Lovisari et al. Reference Lovisari, Ettori, Gaspari and Giles2021). Traditional dynamical mass estimators based on the virial theorem assume that systems are both virialised and well-sampled; these assumptions often break down for groups with low multiplicity, particularly when survey completeness is limited (Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011; Old et al. Reference Old2018; Wojtak et al. Reference Wojtak2018). Collectively, these limitations introduce substantial scatter and systematic uncertainty in halo mass estimates, particularly in the low mass/multiplicity group regime where accurate halo mass measurements are most critical for understanding the impact of baryonic feedback on galaxy evolution (Wechsler & Tinker Reference Wechsler and Tinker2018).

Improved halo mass estimations are required to address several fundamental questions in modern astrophysics. First, the precise shape and amplitude of the halo mass function provide important constraints on cosmological parameters, particularly

![]() $\sigma_{8}$

and

$\sigma_{8}$

and

![]() $\Omega_{m}$

(Tinker et al. Reference Tinker2008; Castro et al. Reference Castro2021; Driver et al. Reference Driver2022a). Second, understanding the coevolution of galaxies and their host haloes requires accurate mapping between observable galaxy properties and underlying halo masses (Behroozi et al. Reference Behroozi, Wechsler, Hearin and Conroy2019; Moster, Naab, & White Reference Moster, Naab and White2020). The scatter in the stellar halo mass relation (SHMR) offers insights into the complex baryonic processes driving galaxy assembly, including feedback from supernovae, active galactic nuclei (AGN), and star-formation efficiency (Pillepich et al. Reference Pillepich2018; Davies et al. Reference Davies2019; Oyarzún et al. Reference Oyarzún, Tinker, Bundy, Xhakaj and Wyithe2024; Wang & Peng Reference Wang and Peng2025). More broadly, measuring the baryonic properties of galaxies as a function of halo mass remains a central goal in galaxy evolution and cosmology. For example, Chauhan et al. (Reference Chauhan2020) demonstrated that the signatures of AGN feedback on the HI content of haloes are remarkably strong, with variations between simulations exceeding 1 dex. However, subsequent work by Chauhan et al. (Reference Chauhan2021) showed that the uncertainties inherent in halo mass estimation, particularly when using the HI stacking techniques commonly adopted in the literature, can completely obscure these feedback signatures, makes it impossible to distinguish between different simulation models. These studies further highlight that while dynamical mass estimators perform well for high-multiplicity systems, but are unable to resolve the underlying distribution for low mass, low multiplicity groups. This underscores the critical importance of minimising halo mass uncertainties in order to robustly connect baryonic content and feedback processes to the underlying dark matter halo population.

$\Omega_{m}$

(Tinker et al. Reference Tinker2008; Castro et al. Reference Castro2021; Driver et al. Reference Driver2022a). Second, understanding the coevolution of galaxies and their host haloes requires accurate mapping between observable galaxy properties and underlying halo masses (Behroozi et al. Reference Behroozi, Wechsler, Hearin and Conroy2019; Moster, Naab, & White Reference Moster, Naab and White2020). The scatter in the stellar halo mass relation (SHMR) offers insights into the complex baryonic processes driving galaxy assembly, including feedback from supernovae, active galactic nuclei (AGN), and star-formation efficiency (Pillepich et al. Reference Pillepich2018; Davies et al. Reference Davies2019; Oyarzún et al. Reference Oyarzún, Tinker, Bundy, Xhakaj and Wyithe2024; Wang & Peng Reference Wang and Peng2025). More broadly, measuring the baryonic properties of galaxies as a function of halo mass remains a central goal in galaxy evolution and cosmology. For example, Chauhan et al. (Reference Chauhan2020) demonstrated that the signatures of AGN feedback on the HI content of haloes are remarkably strong, with variations between simulations exceeding 1 dex. However, subsequent work by Chauhan et al. (Reference Chauhan2021) showed that the uncertainties inherent in halo mass estimation, particularly when using the HI stacking techniques commonly adopted in the literature, can completely obscure these feedback signatures, makes it impossible to distinguish between different simulation models. These studies further highlight that while dynamical mass estimators perform well for high-multiplicity systems, but are unable to resolve the underlying distribution for low mass, low multiplicity groups. This underscores the critical importance of minimising halo mass uncertainties in order to robustly connect baryonic content and feedback processes to the underlying dark matter halo population.

The advent of next-generation wide-field spectroscopic surveys such as Wide Area Vista Extragalactic Survey (WAVES; Driver et al. Reference Driver2019), the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (Desi; DESI Collaboration et al. 2016), and the 4MOST Hemisphere Survey (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor2023) promises to generate comprehensive catalogues of galaxy groups across cosmic time. These surveys will deliver spectroscopic redshifts for millions of galaxies, where high completeness will facilitate the robust identification of gravitationally bound structures at the group scale where environmental effects demonstrably alter galaxy properties and evolutionary trajectories (Peng et al. Reference Peng2010; Wetzel et al. Reference Wetzel, Tinker, Conroy and van den Bosch2013; Davies et al. Reference Davies2019). However, the scientific potential of these datasets precariously depends on our capacity to accurately translate observable group properties into reliable halo mass estimates (Kravtsov, Vikhlinin, & Meshcheryakov Reference Kravtsov, Vikhlinin and Meshcheryakov2018; Eckert et al. Reference Eckert2020; Tinker Reference Tinker2021). This connection between observable baryonic tracers and the underlying dark matter distribution remains fundamental for quantitatively testing hierarchical structure formation models.

The continuous flow of gas into, within, and out of galaxies is referred to as the baryon cycle and represents a key process governing galaxy evolution (Davé et al. Reference Davé, Finlator and Oppenheimer2012; Lilly et al. Reference Lilly, Carollo, Pipino, Renzini and Peng2013). Complementary multi-wavelength facilities such as Euclid (Laureijs et al. Reference Laureijs2011), the Vera Rubin Observatory (LSST Science Collaboration et al. 2009), the Square Kilometre Array (SKA; Dewdney et al. Reference Dewdney, Hall, Schilizzi and Lazio2009), the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA; Wootten & Thompson Reference Wootten and Thompson2009), the extended Roentgen Survey with an Imaging Telescope Array (eROSITA; Merloni et al. Reference Merloni2012), the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston2008), and the Very Large Telescope/Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (VLT/MUSE; Bacon et al. Reference Bacon, McLean, Ramsay and Takami2010) capture distinct components of this cycle: stellar content through optical and near-infrared observations, molecular gas reservoirs via millimetre observations, hot gas through X-ray measurements, neutral hydrogen via radio observations, and spatially resolved gas kinematics through integral-field spectroscopy (Saintonge et al. Reference Saintonge2017; Péroux & Howk Reference Péroux and Howk2020; Tacconi, Genzel, & Sternberg Reference Tacconi, Genzel and Sternberg2020). Pairing these multi-wavelength datasets with spectroscopic information and group catalogues allows us to directly probe the influence of dark matter on the baryon cycle and empirically test how halo properties regulate key processes such as gas accretion rates, star formation efficiency, and feedback-driven outflows across diverse environments and cosmic epochs (Tumlinson, Peeples, & Werk Reference Tumlinson, Peeples and Werk2017; Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Schaye, Bower and Crain2020; van de Voort et al. Reference van de Voort2021). A comprehensive understanding of these complex relationships necessitates both the statistical power of large-scale spectroscopic group catalogues and the detailed multi-wavelength characterisation of baryon cycle components. Nevertheless, precise halo mass measurements remain the critical prerequisite, particularly at the group scale (

![]() $10^{12}$

–

$10^{12}$

–

![]() $10^{14}$

M

$10^{14}$

M

![]() $_{\odot}$

) where the interplay between dark matter and baryonic processes most significantly influences galaxy evolution (Behroozi et al. Reference Behroozi, Wechsler, Hearin and Conroy2019; Davies et al. Reference Davies2019; Wang & Peng Reference Wang and Peng2025).

$_{\odot}$

) where the interplay between dark matter and baryonic processes most significantly influences galaxy evolution (Behroozi et al. Reference Behroozi, Wechsler, Hearin and Conroy2019; Davies et al. Reference Davies2019; Wang & Peng Reference Wang and Peng2025).

Semi-analytical models (SAMs) offer a powerful framework for developing and calibrating such techniques. These models implement physically motivated prescriptions for galaxy formation within dark matter halo merger trees from N-body simulations (Prada et al. Reference Prada, Klypin, Cuesta, Betancort-Rijo and Primack2012; Somerville, Popping, & Trager Reference Somerville, Popping and Trager2015; Croton et al. Reference Croton2016; Lagos et al. Reference Lagos2018; De Lucia et al. Reference De Lucia, Fontanot, Xie and Hirschmann2024). By producing realistic galaxy populations with known halo properties, SAMs allow us to assess the performance of different mass estimation techniques and quantify their associated uncertainties. Recent advances in SAMs, including improved treatments of gas cooling, star formation, and feedback processes, which has significantly enhanced their ability to reproduce observed galaxy properties across a wide range of environments (Klypin et al. Reference Klypin, Yepes, Gottlöber, Prada and Heß2016; Croton et al. Reference Croton2016; Lacey et al. Reference Lacey2016; Lagos et al. Reference Lagos2018; Stevens et al. 2018; Henriques et al. Reference Henriques2020; Lagos et al. Reference Lagos2024; De Lucia et al. Reference De Lucia, Fontanot, Xie and Hirschmann2024).

In this paper, we present two complementary approaches to improve observational halo mass estimates for galaxy groups. The first approach addresses limitations in traditional dynamical mass estimators via the virial theorem when applied to low-multiplicity groups by developing a corrective framework that accounts for systematic biases in groups with small velocity dispersions and projected radius measurements. The second method uses the correlation between baryonic mass and dark matter mass, probing the mass relationship between the three most massive galaxies in the halo and that of the halo mass.

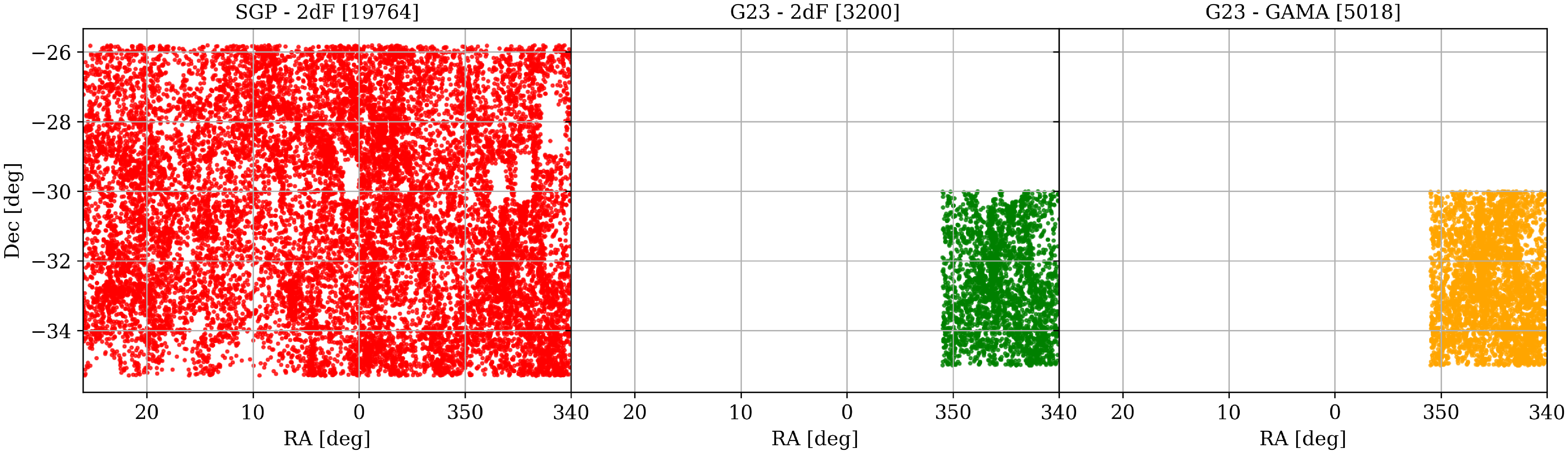

Figure 1. RA–Dec distribution of the three SGP sub-samples used for uniform completeness: SGP–2dF (red), G23–2dF (green), and G23–GAMA (orange). Comparing G23–2dF with G23–GAMA highlights the effect of spectroscopic completeness. Numbers in brackets denote sample sizes.

This paper is organised as follows. In Sections 2 and 3, we introduce the observational dataset in which we showcase applications of the halo mass relations and describe the SAMs used to calibrate/validate our relations. Section 4 introduces our two calibrated halo mass estimators; Section 4.1 presents the first approach utilising a modified virial theorem (MVT) to estimate the halo mass, and in Section 4.2 we present a summed stellar-halo mass relation (sSHMR) using the three most massive galaxies in a group as a proxy for halo mass. In Section 5, we apply the halo mass estimations to the observational data and demonstrate their performance and use cases. Finally, Section 6 summarises our findings and outlines future directions for halo mass estimation in upcoming large-scale surveys.

Throughout this paper, we adopt a flat

![]() $\Lambda$

CDM cosmology with parameters:

$\Lambda$

CDM cosmology with parameters:

![]() $H_{0}$

= 70 km s

$H_{0}$

= 70 km s

![]() $^{-1}$

Mpc

$^{-1}$

Mpc

![]() $^{-1}$

,

$^{-1}$

,

![]() $\Omega_{M}$

= 0.3, and

$\Omega_{M}$

= 0.3, and

![]() $\Omega_{\Lambda}$

= 0.7, unless stated otherwise. All halo masses are defined as

$\Omega_{\Lambda}$

= 0.7, unless stated otherwise. All halo masses are defined as

![]() $M_{200}$

, the mass enclosed within a radius where the mean density is 200 times the critical density of the Universe.

$M_{200}$

, the mass enclosed within a radius where the mean density is 200 times the critical density of the Universe.

2. Observational data

The primary observational dataset used in this work is the Southern Galactic Pole (SGP) catalogue introduced in Van Kempen et al. (Reference Van Kempen2024). The SGP provides a highly complete spectroscopic sample of galaxies at

![]() $z \lt 0.1$

across 376 deg

$z \lt 0.1$

across 376 deg

![]() $^2$

(

$^2$

(

![]() $340^\circ \lt \mathrm{RA} \lt 26^\circ$

,

$340^\circ \lt \mathrm{RA} \lt 26^\circ$

,

![]() $-35.3^\circ \lt \mathrm{Dec} \lt -25.8^\circ$

), the Two-degree-Field Galaxy Redshift Survey (2dFGRS; Colless et al. Reference Colless2001) and Galaxy And Mass Assembly (GAMA; Driver et al. Reference Driver2009) G23 survey regions. Redshifts are sourced primarily from 2dFGRS and GAMA, and are supplemented with the Six-degree Field Galaxy Survey (6dFGRS; Blake et al. Reference Blake2016), the 2-degree Field Lensing Survey (2dFLenS; Jones et al. Reference Jones2004), the 2MASS Redshift Survey (2MRS; Macri et al. Reference Macri2019), and the Million Quasars catalogue (MILLIQUAS; Flesch Reference Flesch2021) measurements. The SGP catalogue is comprised of 24 656 unique spectroscopic sources. These sources were cross-matched with photometry from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE; Wright et al. Reference Wright2010), combining both the WISE Extended Source Catalogue (WXSC; Jarrett et al. Reference Jarrett2013, Reference Jarrett2019) and the point-source AllWISE catalogue (Cluver et al. Reference Cluver2014, Reference Cluver2020). The matching between WISE photometry and that of the spectroscopic sources was approximately 93%, yielding mid-infrared measurements for 22 933 galaxies. The cross-matched WISE photometry enables robust estimates of stellar masses, derived from the W1-based relations of Jarrett et al. (Reference Jarrett2023), as well as star formation rates, calculated from W3 and W4 luminosities following the calibrations of Cluver et al. (Reference Cluver2025).

$-35.3^\circ \lt \mathrm{Dec} \lt -25.8^\circ$

), the Two-degree-Field Galaxy Redshift Survey (2dFGRS; Colless et al. Reference Colless2001) and Galaxy And Mass Assembly (GAMA; Driver et al. Reference Driver2009) G23 survey regions. Redshifts are sourced primarily from 2dFGRS and GAMA, and are supplemented with the Six-degree Field Galaxy Survey (6dFGRS; Blake et al. Reference Blake2016), the 2-degree Field Lensing Survey (2dFLenS; Jones et al. Reference Jones2004), the 2MASS Redshift Survey (2MRS; Macri et al. Reference Macri2019), and the Million Quasars catalogue (MILLIQUAS; Flesch Reference Flesch2021) measurements. The SGP catalogue is comprised of 24 656 unique spectroscopic sources. These sources were cross-matched with photometry from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE; Wright et al. Reference Wright2010), combining both the WISE Extended Source Catalogue (WXSC; Jarrett et al. Reference Jarrett2013, Reference Jarrett2019) and the point-source AllWISE catalogue (Cluver et al. Reference Cluver2014, Reference Cluver2020). The matching between WISE photometry and that of the spectroscopic sources was approximately 93%, yielding mid-infrared measurements for 22 933 galaxies. The cross-matched WISE photometry enables robust estimates of stellar masses, derived from the W1-based relations of Jarrett et al. (Reference Jarrett2023), as well as star formation rates, calculated from W3 and W4 luminosities following the calibrations of Cluver et al. (Reference Cluver2025).

As the SGP catalogue is constructed from multiple spectroscopic catalogues, the resulting dataset is heterogeneous in nature. To establish homogeneity for our analyses, we define three spectroscopic sub-samples: (1) SGP–2dF, comprising all galaxies with 2dFGRS photometry across the full SGP footprint; (2) G23–2dF, containing galaxies with 2dFGRS photometry restricted to the GAMA G23 region (

![]() $339^\circ \lt \mathrm{RA} \lt 351^\circ$

,

$339^\circ \lt \mathrm{RA} \lt 351^\circ$

,

![]() $-35^\circ \lt \mathrm{Dec} \lt -30^\circ$

); and (3) G23–GAMA, consisting of galaxies with GAMA photometry within G23. Figure 1 presents an Right Ascension–Declination view of the homogeneous, WISE cross-matched sub-samples of the SGP dataset. The G23-GAMA sub-samples clearly demonstrate higher spectroscopic completeness, which is approximately 2.3 times greater than that of G23–2dF.

$-35^\circ \lt \mathrm{Dec} \lt -30^\circ$

); and (3) G23–GAMA, consisting of galaxies with GAMA photometry within G23. Figure 1 presents an Right Ascension–Declination view of the homogeneous, WISE cross-matched sub-samples of the SGP dataset. The G23-GAMA sub-samples clearly demonstrate higher spectroscopic completeness, which is approximately 2.3 times greater than that of G23–2dF.

The SGP catalogue provides 1 413 galaxy groups, identified via a Python-based, graph-theory implementation of a friends-of-friends (FoF) algorithm, FoFpy (Lambert et al. Reference Lambert, Kraan-Korteweg, Jarrett and Macri2020). FoFpy links galaxies when both their projected separations and line-of-sight velocity differences fall below scalable linking lengths, with a probabilistic cut used to reject links (see Lambert et al. Reference Lambert, Kraan-Korteweg, Jarrett and Macri2020 for further details on the FoFpy algorithm). To ensure robust recovery of galaxy groups, a two-pass strategy was adopted: an initial FoF run with extended linking lengths captured larger groups, which were removed prior to a second pass with smaller linking lengths targeting smaller groups. The linking lengths were calibrated using mock lightcones constructed from the Millennium simulation (Springel et al. Reference Springel2005) and the Semi-Analytic Galaxy Evolution (SAGE) model (Croton et al. Reference Croton2016). These mock lightcones were generated with 2dFGRS (

![]() $b_{J}=19.45$

) and GAMA (

$b_{J}=19.45$

) and GAMA (

![]() $i=19.2$

) magnitude limits. See Van Kempen et al. (Reference Van Kempen2024) for a full description of the construction of the SGP group catalogue.

$i=19.2$

) magnitude limits. See Van Kempen et al. (Reference Van Kempen2024) for a full description of the construction of the SGP group catalogue.

3. Semi-analytic models of galaxy formation

This section provides a comprehensive overview of the simulated datasets used in this study. We describe the suite of state-of-the-art SAMs of galaxy formation employed in this work. SAMs represent powerful theoretical tools for exploring the interplay between dark matter structure formation and baryonic physics. These models implement physically motivated prescriptions for key astrophysical processes within merger trees extracted from cosmological N-body simulations (see reviews by Baugh Reference Baugh2006; Benson Reference Benson2010). By providing self-consistent galaxy populations with fully known dark matter halo properties, SAMs offer an ideal framework for developing and calibrating halo-mass estimation techniques. In this work, three independent SAMs are used with distinct roles: Shark (Lagos et al. Reference Lagos2018, Reference Lagos2024) Lagos et al. Reference Lagos2018; Lagos et al. Reference Lagos2024) serves as the fiducial calibration model for the halo mass estimates, whereas SAGE and the GAlaxy Evolution and Assembly (GAEA; De Lucia et al. Reference De Lucia2014, Reference De Lucia, Fontanot, Xie and Hirschmann2024; Hirschmann, De Lucia, & Fontanot Reference Hirschmann, De Lucia and Fontanot2016) models are used exclusively for validation and robustness testing. No parameters of the estimators are re-tuned on SAGE or GAEA. Each of these SAMs implement different physical prescriptions while operating on distinct N-body simulations. This multi-model approach enables assessment of robustness to variations in the underlying galaxy-formation physics and cosmology.

To ensure comparability with the observations described in Section 2, all SAM outputs are post-processed into mock light cones with realistic sky coordinates and redshifts, including peculiar-velocity–induced redshift-space distortions. Apparent magnitudes are computed and an SGP-like selection is applied (e.g. GAMA G23 magnitude limit of

![]() $i\lt19.2$

) to emulate the survey depth. Galaxy groups in the SAMs provide ground-truth memberships and halo masses while retaining observational selection effects. Estimator inputs are restricted to observables after the SGP-like selection, this methodology ensures that the calibration and validation of halo mass estimators are performed under conditions that closely mimic real, highly complete spectroscopic surveys, thereby enhancing the reliability and applicability of the methods to current and future observational datasets. As a caveat, a fainter magnitude limit of

$i\lt19.2$

) to emulate the survey depth. Galaxy groups in the SAMs provide ground-truth memberships and halo masses while retaining observational selection effects. Estimator inputs are restricted to observables after the SGP-like selection, this methodology ensures that the calibration and validation of halo mass estimators are performed under conditions that closely mimic real, highly complete spectroscopic surveys, thereby enhancing the reliability and applicability of the methods to current and future observational datasets. As a caveat, a fainter magnitude limit of

![]() $Z\lt21.2$

is used for Shark in the development of the sSHMR (see Section 4.2.3).

$Z\lt21.2$

is used for Shark in the development of the sSHMR (see Section 4.2.3).

3.1. SHARK

Shark v2.0 (Lagos et al. Reference Lagos2018, Reference Lagos2024) is an open-source, modular semi-analytic model of galaxy formation and evolution. The latest version incorporates significant advancements, including an improved treatment of angular momentum evolution, several environmental processes including ram pressure and tidal stripping, and updated feedback models. The free parameters in Shark are calibrated to reproduce the observed stellar mass function, star formation rate density, and cold gas scaling relations at

![]() $z = 0$

.

$z = 0$

.

The Shark runs analysed in this work are based on the SURFS suite of N-body simulations (Elahi et al. Reference Elahi2018), specifically medi-SURFS, which spans

![]() $(210h^{-1}\mathrm{Mpc})^3$

with

$(210h^{-1}\mathrm{Mpc})^3$

with

![]() $1\,536^3$

dark matter particles, yielding a particle mass of

$1\,536^3$

dark matter particles, yielding a particle mass of

![]() $2.21\times10^8h^{-1}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$

. Haloes, sub-haloes, and merger trees are constructed using HBT+HERONS (Chandro-Gómez et al. Reference Chandro-Gómez2025). The Shark simulated light cones used in this work correspond to WAVES WIDE (North + South) light cones, totalling

$2.21\times10^8h^{-1}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$

. Haloes, sub-haloes, and merger trees are constructed using HBT+HERONS (Chandro-Gómez et al. Reference Chandro-Gómez2025). The Shark simulated light cones used in this work correspond to WAVES WIDE (North + South) light cones, totalling

![]() $\sim 1\,100\,\mathrm{deg}^2$

in area. These light cones were constructed using the pipeline described in Lagos et al. (Reference Lagos2019): the survey geometry and magnitude selections are built using Stingray (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan2019), and the galaxy SEDs are built using ProSpect (Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2020). A lower stellar mass limit of

$\sim 1\,100\,\mathrm{deg}^2$

in area. These light cones were constructed using the pipeline described in Lagos et al. (Reference Lagos2019): the survey geometry and magnitude selections are built using Stingray (Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan2019), and the galaxy SEDs are built using ProSpect (Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2020). A lower stellar mass limit of

![]() $\log M_{\star} \gt 7.5\,({\rm M}_{\odot})$

was applied to the mock light cones to ensure completeness and reliability in the resulting galaxy sample. The simulation adopts a Planck 2015 cosmology (Planck Collaboration et al. 2016), with

$\log M_{\star} \gt 7.5\,({\rm M}_{\odot})$

was applied to the mock light cones to ensure completeness and reliability in the resulting galaxy sample. The simulation adopts a Planck 2015 cosmology (Planck Collaboration et al. 2016), with

![]() $\Omega_{{m}} = 0.3121$

,

$\Omega_{{m}} = 0.3121$

,

![]() $\Omega_{\Lambda} = 0.6879$

,

$\Omega_{\Lambda} = 0.6879$

,

![]() $\Omega_{{b}} = 0.0491$

,

$\Omega_{{b}} = 0.0491$

,

![]() $h = 0.6751$

,

$h = 0.6751$

,

![]() $\sigma_8 = 0.8150$

, and

$\sigma_8 = 0.8150$

, and

![]() $n_{{s}} = 0.9653$

. All calibrations of the halo mass relations are performed on Shark.

$n_{{s}} = 0.9653$

. All calibrations of the halo mass relations are performed on Shark.

3.2. SAGE

The Semi-Analytic Galaxy Evolution (SAGE) model (Croton et al. Reference Croton2016) is a flexible, publicly available semi-analytic framework, building upon the Munich model lineage (Croton et al. Reference Croton2006). SAGE incorporates detailed prescriptions for radiative cooling, star formation, stellar and AGN feedback, black hole growth, and environmental processes. The model parameters are tuned to match the observed stellar mass function and galaxy colour distributions at

![]() $z = 0$

.

$z = 0$

.

For this study, SAGE is applied to the BOLSHOI N-body simulation (Klypin, Trujillo-Gomez, & Primack Reference Klypin, Trujillo-Gomez and Primack2011), which covers a volume of

![]() $(250h^{-1}\mathrm{Mpc})^3$

with

$(250h^{-1}\mathrm{Mpc})^3$

with

![]() $2\,048^3$

particles, corresponding to a mass resolution of

$2\,048^3$

particles, corresponding to a mass resolution of

![]() $1.35 \times 10^8h^{-1}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$

. The SAGE simulated light cones used in this work consisted of 10 lightcones, each with an area of

$1.35 \times 10^8h^{-1}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$

. The SAGE simulated light cones used in this work consisted of 10 lightcones, each with an area of

![]() $\sim 1\,960\,\mathrm{deg}^2$

. Haloes are identified using the ROCKSTAR phase-space halo finder (Behroozi, Wechsler, & Wu Reference Behroozi, Wechsler and Wu2013a), and merger trees are constructed with the Consistent Trees algorithm (Behroozi et al. Reference Behroozi2013b). A lower stellar mass limit of

$\sim 1\,960\,\mathrm{deg}^2$

. Haloes are identified using the ROCKSTAR phase-space halo finder (Behroozi, Wechsler, & Wu Reference Behroozi, Wechsler and Wu2013a), and merger trees are constructed with the Consistent Trees algorithm (Behroozi et al. Reference Behroozi2013b). A lower stellar mass limit of

![]() $\log M_{\star} \gt 7.5\,({\rm M}_{\odot})$

was applied to the mock light cones to ensure completeness and reliability in the resulting galaxy sample. The adopted cosmology is based on WMAP7 (Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu2011), with

$\log M_{\star} \gt 7.5\,({\rm M}_{\odot})$

was applied to the mock light cones to ensure completeness and reliability in the resulting galaxy sample. The adopted cosmology is based on WMAP7 (Komatsu et al. Reference Komatsu2011), with

![]() $\Omega_{{m}} = 0.270$

,

$\Omega_{{m}} = 0.270$

,

![]() $\Omega_{\Lambda} = 0.730$

,

$\Omega_{\Lambda} = 0.730$

,

![]() $\Omega_{{b}} = 0.0469$

,

$\Omega_{{b}} = 0.0469$

,

![]() $h = 0.70$

,

$h = 0.70$

,

![]() $\sigma_8 = 0.82$

, and

$\sigma_8 = 0.82$

, and

![]() $n_{{s}} = 0.95$

. SAGE is used solely to validate the halo mass estimators without any re-tuning, thereby probing sensitivity to differing galaxy-formation prescriptions.

$n_{{s}} = 0.95$

. SAGE is used solely to validate the halo mass estimators without any re-tuning, thereby probing sensitivity to differing galaxy-formation prescriptions.

3.3. GAEA

The Galaxy Evolution and Assembly (GAEA) semi-analytic model (De Lucia et al. Reference De Lucia2014; Hirschmann et al. Reference Hirschmann, De Lucia and Fontanot2016; De Lucia et al. Reference De Lucia, Fontanot, Xie and Hirschmann2024) provides an independent theoretical benchmark in this work. The latest version includes updated prescriptions for AGN feedback, environmental processes affecting satellites, black hole accretion, disk instabilities, and starburst activity (Fontanot et al. Reference Fontanot2020; De Lucia et al. Reference De Lucia, Fontanot, Wilman and Monaco2011).

GAEA parameters are calibrated to match the stellar mass function over

![]() $0 \lt z \lt 4$

, local atomic and molecular hydrogen mass functions, and AGN bolometric luminosity function evolution to

$0 \lt z \lt 4$

, local atomic and molecular hydrogen mass functions, and AGN bolometric luminosity function evolution to

![]() $z \sim 4$

. The model is run on merger trees from the Millennium Simulation (Springel et al. Reference Springel2005), which adopts a

$z \sim 4$

. The model is run on merger trees from the Millennium Simulation (Springel et al. Reference Springel2005), which adopts a

![]() $\Lambda$

CDM cosmology with

$\Lambda$

CDM cosmology with

![]() $\Omega_{{m}} = 0.25$

,

$\Omega_{{m}} = 0.25$

,

![]() $\Omega_{{b}} = 0.045$

,

$\Omega_{{b}} = 0.045$

,

![]() $\Omega_{\Lambda} = 0.75$

,

$\Omega_{\Lambda} = 0.75$

,

![]() $h = 0.73$

,

$h = 0.73$

,

![]() $n_{{s}} = 1$

, and

$n_{{s}} = 1$

, and

![]() $\sigma_8 = 0.8$

. The simulation volume is

$\sigma_8 = 0.8$

. The simulation volume is

![]() $(500h^{-1}\mathrm{Mpc})^3$

, with a particle mass of

$(500h^{-1}\mathrm{Mpc})^3$

, with a particle mass of

![]() $8.625 \times 10^8~h^{-1}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$

. The constructed observational cone from this simulation, was large enough to produce a full celestial sphere (

$8.625 \times 10^8~h^{-1}\,{\rm M}_{\odot}$

. The constructed observational cone from this simulation, was large enough to produce a full celestial sphere (

![]() $\sim 41\,253 \, \mathrm{deg}^2$

). A lower stellar mass limit of

$\sim 41\,253 \, \mathrm{deg}^2$

). A lower stellar mass limit of

![]() $\log M_{\star} \gt 8\,({\rm M}_{\odot})$

was applied to the mock light cones to ensure completeness and reliability in the resulting galaxy sample. Haloes and merger trees are constructed using Subfind and Sub-LINK (Springel et al. Reference Springel, White, Tormen and Kauffmann2001). GAEA is used solely to validate our halo mass estimates, without any re-tuning, thereby probing the estimates sensitivity to differing galaxy-formation prescriptions.

$\log M_{\star} \gt 8\,({\rm M}_{\odot})$

was applied to the mock light cones to ensure completeness and reliability in the resulting galaxy sample. Haloes and merger trees are constructed using Subfind and Sub-LINK (Springel et al. Reference Springel, White, Tormen and Kauffmann2001). GAEA is used solely to validate our halo mass estimates, without any re-tuning, thereby probing the estimates sensitivity to differing galaxy-formation prescriptions.

4. Halo mass relations

In the group and cluster regime, halo mass estimates are traditionally derived from dynamical tracers, such as the velocity dispersion of member galaxies, or from abundance matching techniques that link observed galaxy properties to theoretical halo mass functions (Yang et al. Reference Yang2007; Viola et al. Reference Viola2015; Lim et al. Reference Lim2021). However, these methods are subject to significant systematic uncertainties, particularly at low halo masses and for groups with low multiplicity, where the reliability of dynamical indicators is compromised by small number statistics and projection effects (Old et al. Reference Old2015; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011; Muldrew et al. Reference Muldrew2012).

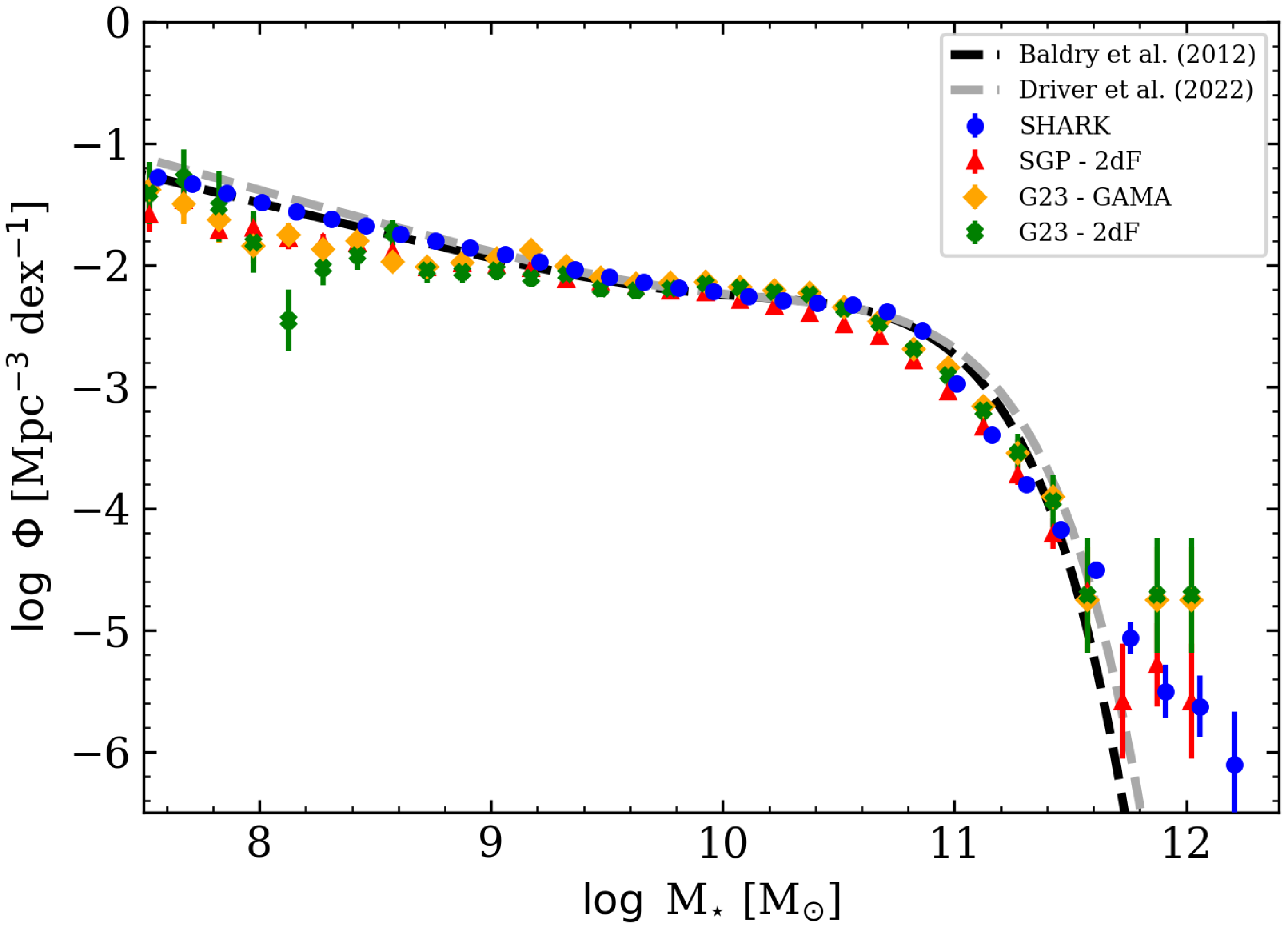

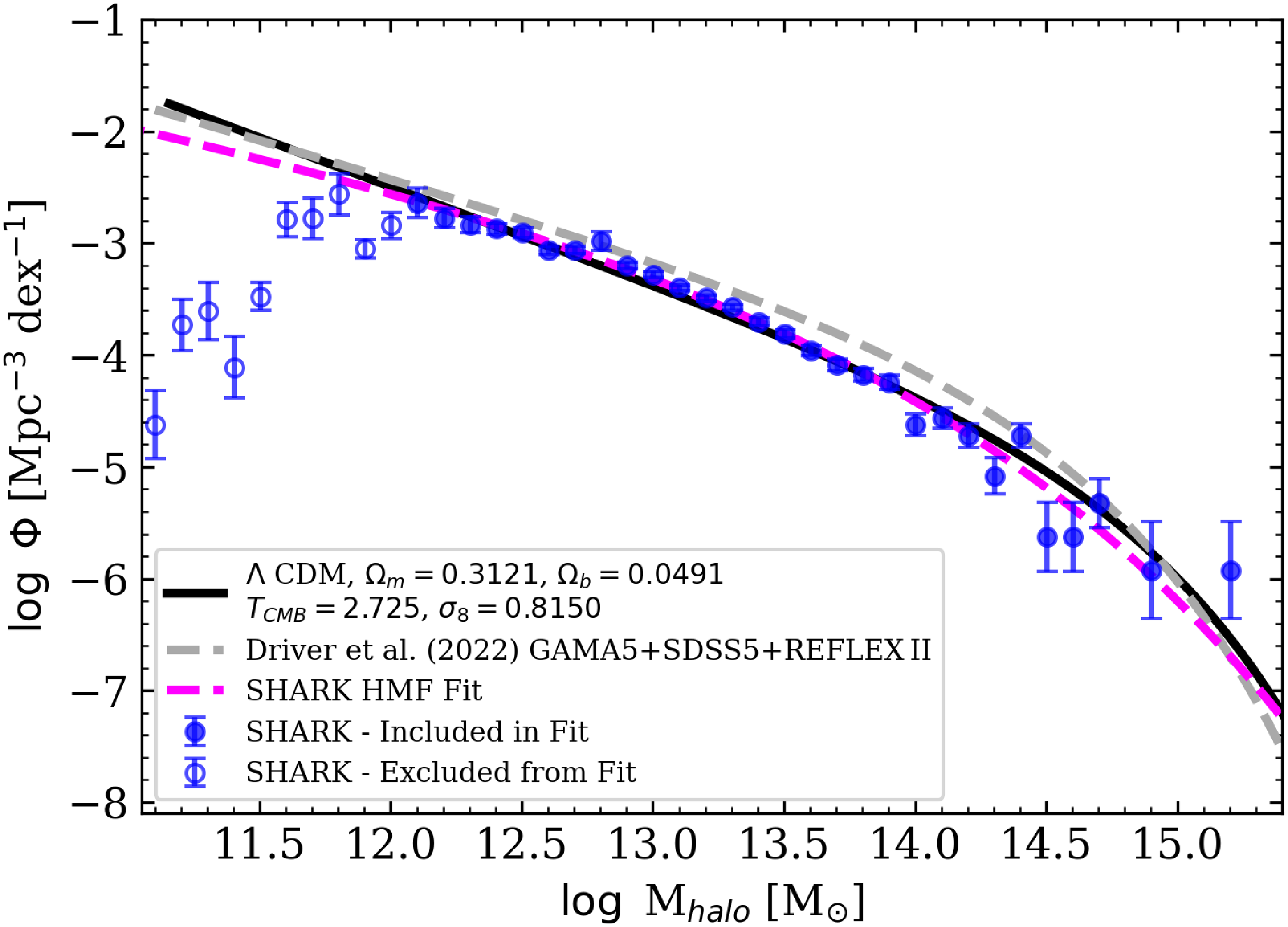

To provide a physically motivated and observationally calibrated framework for halo mass estimation, we chose to calibrate our halo mass estimators to Shark. This decision is motivated by Shark’s demonstrated ability to reproduce key observables, most notably the observed stellar mass function (SMF; Figure 2) and halo mass function (HMF; Figure 3), when measured using observational techniques. Furthermore, Shark is specifically tailored for application to forthcoming large-scale surveys, most notably WAVES, but also 4HS, and will serve as the primary simulation framework for training and assessing future group-finding algorithms to be used in these surveys (Lagos et al. Reference Lagos2019). In addition, recent advancements in Shark, such as the implementation of the HBT+HERONS merger tree algorithm (Chandro-Gómez et al. Reference Chandro-Gómez2025), have significantly reduced numerical artefacts, including: mass swapping, massive transients, and orphan galaxies – that can arise in dark matter merger trees. These improvements yield a more stable and physically consistent halo population, which is essential for the development of robust and reliable halo mass estimators.

Figure 2. Comparison of the SMF from Shark to well-established observational SMFs and SMFs produced by observational data from Van Kempen et al. (Reference Van Kempen2024). The figure shows the SMF (

![]() $\log \unicode{x03D5}$

) versus stellar mass (

$\log \unicode{x03D5}$

) versus stellar mass (

![]() $\log M_{\star}$

) for Shark v2.0 (blue circles) alongside canonical constraints from Baldry et al. (Reference Baldry2012) (black dashed line) and Driver et al. (Reference Driver2022a) (grey dashed line). Red triangles, orange diamonds, and green crosses represent our observational data from Van Kempen et al. (Reference Van Kempen2024) (SGP-2dF, G23-GAMA, and G23-2dF datasets, respectively). Error bars indicate Poisson uncertainties. Shark demonstrates excellent agreement with the established SMFs and across our observational datasets, with only minor deviations.

$\log M_{\star}$

) for Shark v2.0 (blue circles) alongside canonical constraints from Baldry et al. (Reference Baldry2012) (black dashed line) and Driver et al. (Reference Driver2022a) (grey dashed line). Red triangles, orange diamonds, and green crosses represent our observational data from Van Kempen et al. (Reference Van Kempen2024) (SGP-2dF, G23-GAMA, and G23-2dF datasets, respectively). Error bars indicate Poisson uncertainties. Shark demonstrates excellent agreement with the established SMFs and across our observational datasets, with only minor deviations.

Figure 3. Comparison of the HMF derived from Shark with analytic and observational benchmarks. The blue data points represent the Shark HMF, with error bars indicating Poisson uncertainties in each mass bin. The solid black curve denotes the analytic HMF prediction for the input cosmology of Shark, computed using the hmf Python package (Murray, Power, & Robotham Reference Murray, Power and Robotham2013). The grey dashed line shows the empirical fit from Driver et al. (Reference Driver2022a), based on GAMA5, SDSS5, and REFLEX II data. The magenta dashed curve corresponds to a Schechter function fit to the Shark HMF.

As shown in Figure 2, Shark provides an excellent match to well-established observational SMFs (Baldry et al. Reference Baldry2012; Driver et al. Reference Driver2022a) across the full stellar mass range. The observational datasets from Van Kempen et al. (Reference Van Kempen2024) (SGP-2dF, G23-GAMA, and G23-2dF) show good agreement with the Baldry et al. (Reference Baldry2012) and Driver et al. (Reference Driver2022a) SMFs across the intermediate to high stellar mass range, which demonstrates the reliability of the sample in this regime. At lower stellar masses, however, the observed SMFs exhibit a deficit relative to these fits. This offset is attributable to the limitations of WISE photometry in detecting low-surface brightness and low stellar mass galaxies, resulting in systematic incompleteness at the faint end. Such incompleteness is a well-known limitation of near-infrared selected samples and must be considered when interpreting the low-mass behaviour of the observed SMF.

The SMF and HMF are constructed using a standard

![]() $1/V_{\mathrm{max}}$

approach to correct for survey incompleteness and selection effects. For a given mass bin (

$1/V_{\mathrm{max}}$

approach to correct for survey incompleteness and selection effects. For a given mass bin (

![]() $\Delta \log M$

; stellar mass for the SMF and halo mass for the HMF), the number density is computed as:

$\Delta \log M$

; stellar mass for the SMF and halo mass for the HMF), the number density is computed as:

where

![]() $V_{\mathrm{max}}^i$

is the maximum comoving volume within which the ith galaxy (for the SMF) or group (for the HMF) could be observed, given the survey magnitude limits and selection criteria. For the SMF,

$V_{\mathrm{max}}^i$

is the maximum comoving volume within which the ith galaxy (for the SMF) or group (for the HMF) could be observed, given the survey magnitude limits and selection criteria. For the SMF,

![]() $V_{\mathrm{max}}^i$

is determined by the redshift range over which each galaxy remains above the survey flux limit. For the HMF, following the methodology of Driver et al. (Reference Driver2022a),

$V_{\mathrm{max}}^i$

is determined by the redshift range over which each galaxy remains above the survey flux limit. For the HMF, following the methodology of Driver et al. (Reference Driver2022a),

![]() $V_{\mathrm{max}}^i$

is estimated based on the nth brightest galaxy in each group (here,

$V_{\mathrm{max}}^i$

is estimated based on the nth brightest galaxy in each group (here,

![]() $n=3$

), such that the group’s

$n=3$

), such that the group’s

![]() $V_{\mathrm{max}}$

is calculated based on the maximum survey volume that the nth brightest member remains above the survey flux limit. This approach ensures that the group sample is volume-limited with respect to its membership.

$V_{\mathrm{max}}$

is calculated based on the maximum survey volume that the nth brightest member remains above the survey flux limit. This approach ensures that the group sample is volume-limited with respect to its membership.

The halo mass function (HMF) is fit as a single Schechter function of the form:

where

![]() $M^*$

is the characteristic halo mass,

$M^*$

is the characteristic halo mass,

![]() $\unicode{x03D5}_*$

is the normalisation,

$\unicode{x03D5}_*$

is the normalisation,

![]() $\alpha$

is the low-mass slope, and

$\alpha$

is the low-mass slope, and

![]() $\unicode{x03B2}$

is the exponential cutoff parameter.

$\unicode{x03B2}$

is the exponential cutoff parameter.

Figure 3 demonstrates the close agreement between the Shark HMF and analytic predictions, with only minor deviations at the lowest halo masses. The robust match between Shark and analytic expectations ensures that systematic biases in the halo mass distribution are minimised, providing a reliable foundation for calibrating observational mass proxies.

In the subsequent subsections, the formulation, calibration, accuracy, uncertainty and use cases of each halo mass estimator are described in detail. We employ SAGE and GAEA as independent tests to validate our Shark-calibrated relations. These models were run on different N-body simulations and contain different physical prescriptions, allowing us to assess whether our derived scaling relations remain robust across varied galaxy formation prescriptions and are suitable for general observational applications.

4.1. Modifying the virial theorem

The evolution of dark matter haloes is governed solely by gravitational forces, a regime that is well explored through detailed N-body simulations and SAMs, whereas galaxies are complex systems regulated by a multitude of baryonic processes, including gas cooling, star formation, and feedback (see review of Somerville & Davé Reference Somerville and Davé2015). This fundamental distinction underpins the rationale for employing dynamical, gravity-based estimators for halo mass, which are expected to exhibit minimal dependence on the details of baryonic physics and thus provide a robust, model-independent approach to halo mass estimation.

4.1.1. The virial theorem

In observational studies of galaxy groups and clusters, the velocity dispersion is measured along the line of sight, denoted as

![]() $\sigma_{\mathrm{los}}$

(in units of km s

$\sigma_{\mathrm{los}}$

(in units of km s

![]() $^{-1}$

). For a self-gravitating, isotropic, and uniform sphere of mass M and radius R, the virial theorem relates the total kinetic energy T and potential energy U as

$^{-1}$

). For a self-gravitating, isotropic, and uniform sphere of mass M and radius R, the virial theorem relates the total kinetic energy T and potential energy U as

![]() $2T + U = 0$

in equilibrium. The total kinetic energy can be expressed in terms of

$2T + U = 0$

in equilibrium. The total kinetic energy can be expressed in terms of

![]() $\sigma_{\mathrm{los}}$

as

$\sigma_{\mathrm{los}}$

as

![]() $T = \frac{1}{2} M \sigma_{\mathrm{los}}^2$

, while the gravitational potential energy remains

$T = \frac{1}{2} M \sigma_{\mathrm{los}}^2$

, while the gravitational potential energy remains

![]() $U = -\frac{3}{5} \frac{GM^2}{R}$

. This yields the standard virial mass estimator:

$U = -\frac{3}{5} \frac{GM^2}{R}$

. This yields the standard virial mass estimator:

where R is a radius (e.g. the maximum projected separation among group members from the median centre of the group) in units of Mpc, and G is the gravitational constant in units of M

![]() $_{\odot}^{-1}\,\mathrm{km}^2\,\mathrm{s}^{-2}\,\mathrm{Mpc}$

, yielding a mass in

$_{\odot}^{-1}\,\mathrm{km}^2\,\mathrm{s}^{-2}\,\mathrm{Mpc}$

, yielding a mass in

![]() $h^{-1}{\rm M}_{\odot}$

. This estimator is widely used in both observational and theoretical studies of galaxy groups and clusters (e.g. Carlberg et al. Reference Carlberg1996; Eke et al. Reference Eke2004; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011). While the

$h^{-1}{\rm M}_{\odot}$

. This estimator is widely used in both observational and theoretical studies of galaxy groups and clusters (e.g. Carlberg et al. Reference Carlberg1996; Eke et al. Reference Eke2004; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011). While the

![]() $\frac{5}{3}$

coefficient is sometimes omitted in the literature (e.g. Finn et al. Reference Finn2005; Evrard et al. Reference Evrard2008; Lau, Nagai, & Kravtsov Reference Lau, Nagai and Kravtsov2010; Poggianti et al. Reference Poggianti2010; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011; Alpaslan et al. Reference Alpaslan2012), it is physically motivated and essential for accurate mass estimates, particularly for massive halos.

$\frac{5}{3}$

coefficient is sometimes omitted in the literature (e.g. Finn et al. Reference Finn2005; Evrard et al. Reference Evrard2008; Lau, Nagai, & Kravtsov Reference Lau, Nagai and Kravtsov2010; Poggianti et al. Reference Poggianti2010; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011; Alpaslan et al. Reference Alpaslan2012), it is physically motivated and essential for accurate mass estimates, particularly for massive halos.

The line-of-sight velocity dispersion,

![]() $\sigma_{\mathrm{los}}$

, is calculated using the Gapper (gap) method (Beers, Flynn, & Gebhardt Reference Beers, Flynn and Gebhardt1990), which is particularly robust for small group sizes and is less sensitive to outliers than standard deviation-based estimators. For a group of N galaxies with ordered velocities

$\sigma_{\mathrm{los}}$

, is calculated using the Gapper (gap) method (Beers, Flynn, & Gebhardt Reference Beers, Flynn and Gebhardt1990), which is particularly robust for small group sizes and is less sensitive to outliers than standard deviation-based estimators. For a group of N galaxies with ordered velocities

![]() $v_1 \lt v_2 \lt \cdots \lt v_N$

, the Gapper estimator is defined as:

$v_1 \lt v_2 \lt \cdots \lt v_N$

, the Gapper estimator is defined as:

where

![]() $g_i = v_{i+1} - v_i$

is the velocity gap between adjacent ordered velocities, and

$g_i = v_{i+1} - v_i$

is the velocity gap between adjacent ordered velocities, and

![]() $w_i = i(N-i)$

is a weighting factor. Through the use of ordered velocity gaps, the gap method provides lower sampling variance than standard-deviation or bi-weight scale estimators, and is less sensitive to interlopers and has thus become a standard approach in modern group catalogues (e.g. Eke et al. Reference Eke2004; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011; Old et al. Reference Old2015).

$w_i = i(N-i)$

is a weighting factor. Through the use of ordered velocity gaps, the gap method provides lower sampling variance than standard-deviation or bi-weight scale estimators, and is less sensitive to interlopers and has thus become a standard approach in modern group catalogues (e.g. Eke et al. Reference Eke2004; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011; Old et al. Reference Old2015).

In most mock haloes, the brightest galaxy is assumed to be at rest with respect to the halo centre of mass. To account for this, the velocity dispersion is further corrected by a factor of

![]() $\sqrt{N/(N-1)}$

(Eke et al. Reference Eke2004; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011). The final velocity dispersion is then given by:

$\sqrt{N/(N-1)}$

(Eke et al. Reference Eke2004; Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011). The final velocity dispersion is then given by:

This approach ensures that the velocity dispersion estimates are unbiased and robust, even for low-multiplicity systems, and that the dominant sources of observational uncertainty are properly propagated (Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011).

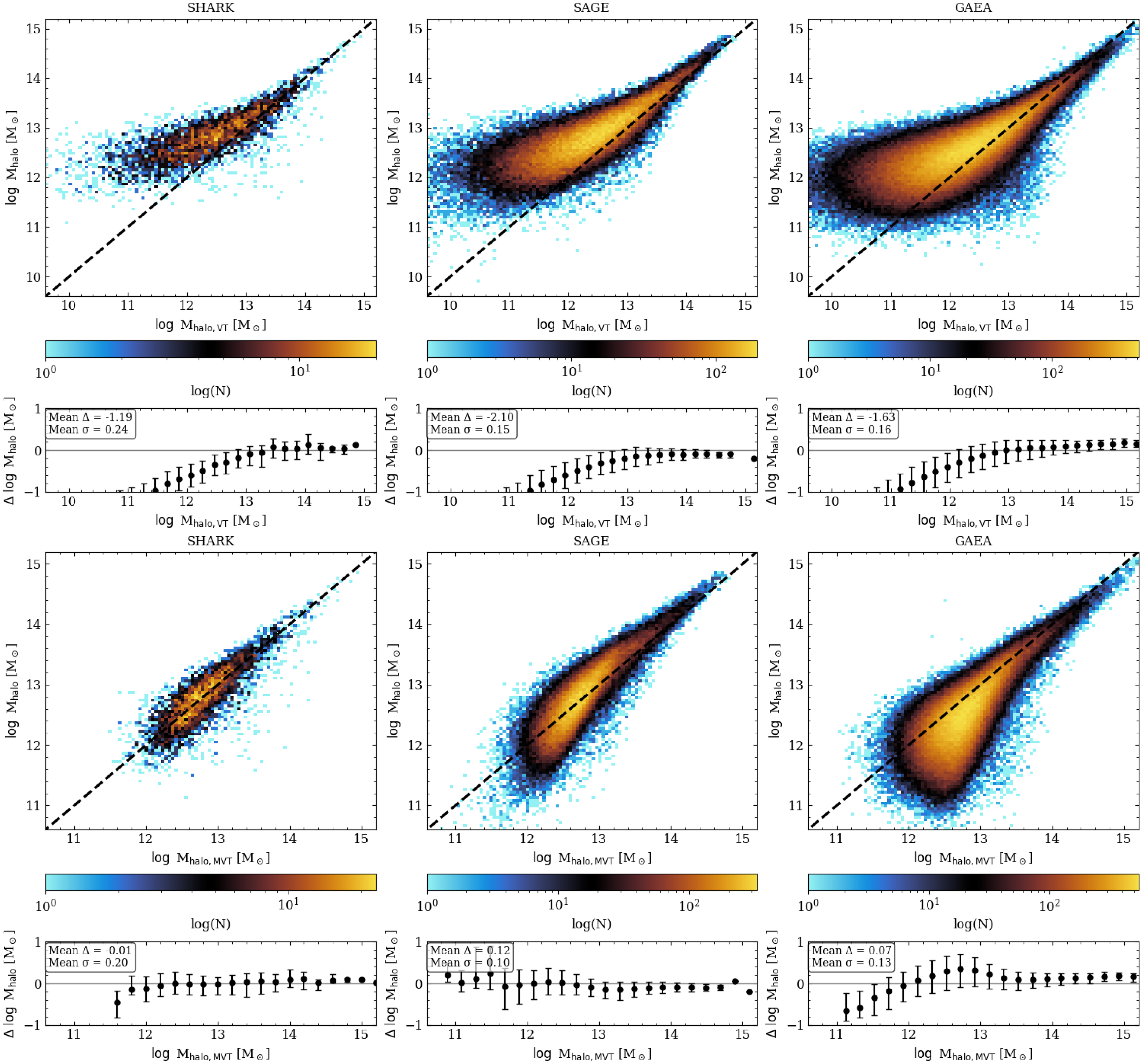

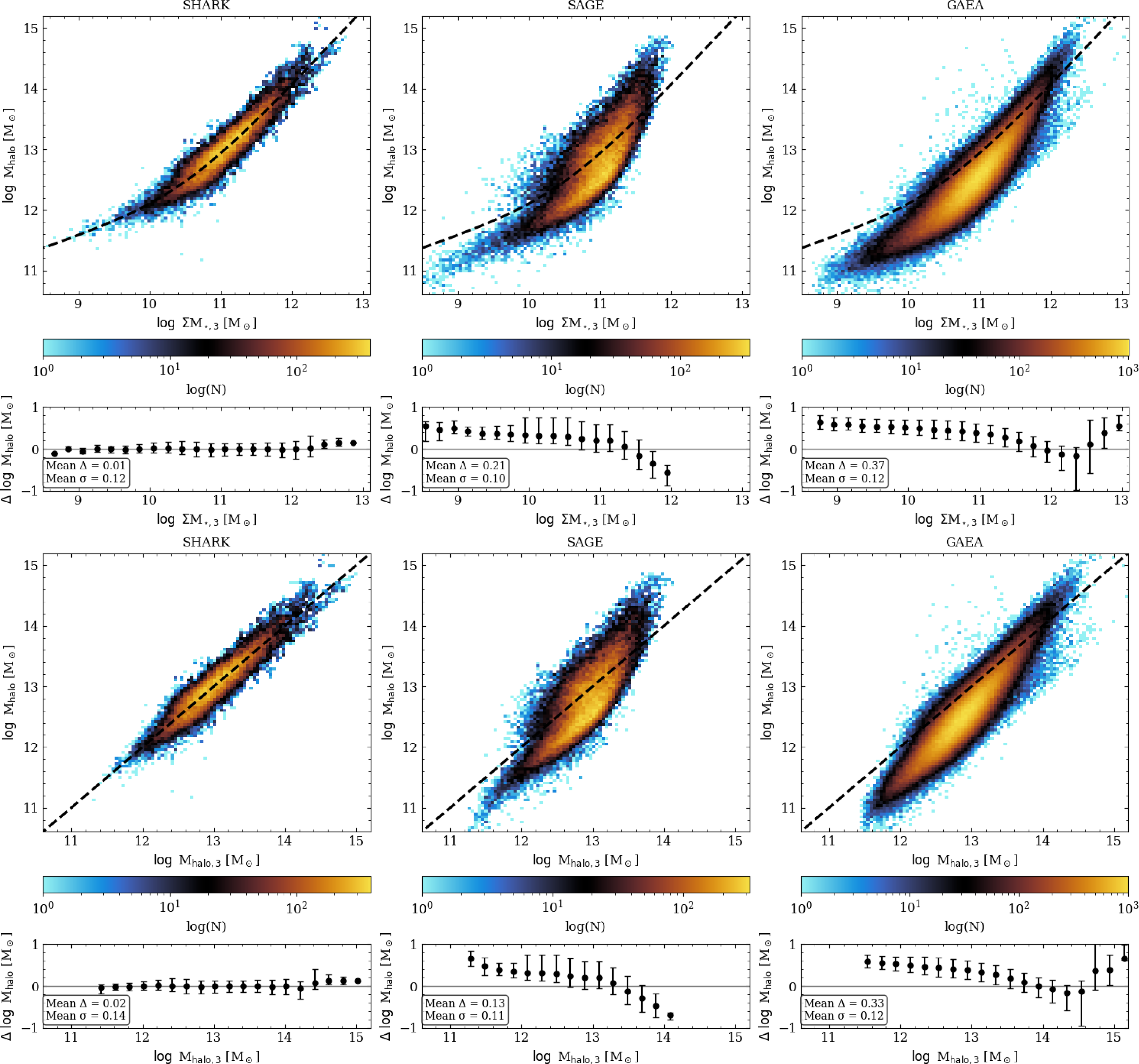

Figure 4. Comparison of halo mass estimates derived from the velocity dispersion relation before and after calibration, across three semi-analytic models: Shark, SAGE, and GAEA. All samples have a manitude limit of

![]() $i\lt19.2$

and a redshift limit of

$i\lt19.2$

and a redshift limit of

![]() $z\lt0.1$

. Top Row: The virial theorem halo mass (

$z\lt0.1$

. Top Row: The virial theorem halo mass (

![]() $\log M_{\mathrm{halo, \, VT}}$

) versus the true halo mass (

$\log M_{\mathrm{halo, \, VT}}$

) versus the true halo mass (

![]() $\log M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

) for each model, with colour indicating the logarithmic number density of halos in each bin. The dashed line denotes the one-to-one relation. Second Row: Corresponding residuals (

$\log M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

) for each model, with colour indicating the logarithmic number density of halos in each bin. The dashed line denotes the one-to-one relation. Second Row: Corresponding residuals (

![]() $\Delta \log M_{\mathrm{halo}} = \log M_{\mathrm{halo, \, VT}} - \log M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

) and error bars indicate 16th and 84th percentiles in each bin. The mean offset and scatter indicated in the legend. Third Row: The MVT halo mass estimates (

$\Delta \log M_{\mathrm{halo}} = \log M_{\mathrm{halo, \, VT}} - \log M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

) and error bars indicate 16th and 84th percentiles in each bin. The mean offset and scatter indicated in the legend. Third Row: The MVT halo mass estimates (

![]() $\log$

M

$\log$

M

![]() $_{\mathrm{halo, \, MVT}}$

), compared to the true halo mass (

$_{\mathrm{halo, \, MVT}}$

), compared to the true halo mass (

![]() $\log M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

). Bottom Row: Corresponding median of residuals (

$\log M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

). Bottom Row: Corresponding median of residuals (

![]() $\Delta \log M_{\mathrm{halo}} = \log M_{\mathrm{halo, \, MVT}} - \log M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

) and error bars indicate 16th and 84th percentiles in each bin. The mean offset and scatter indicated in the legend.

$\Delta \log M_{\mathrm{halo}} = \log M_{\mathrm{halo, \, MVT}} - \log M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

) and error bars indicate 16th and 84th percentiles in each bin. The mean offset and scatter indicated in the legend.

The top panels of Figure 4 compare the true halo masses from the simulations to those measured using the virial theorem via Equation (3) on the simulated light-cones with a

![]() $z\lt0.1$

limit. These results demonstrate that the traditional virial theorem mass estimator is subject to substantial scatter and systematic offsets, particularly at low halo masses and for systems with low multiplicity. As shown in the lower panels, the mean offset (

$z\lt0.1$

limit. These results demonstrate that the traditional virial theorem mass estimator is subject to substantial scatter and systematic offsets, particularly at low halo masses and for systems with low multiplicity. As shown in the lower panels, the mean offset (

![]() $\Delta$

) between the estimated and true halo masses is significant across all models, reaching values as large as

$\Delta$

) between the estimated and true halo masses is significant across all models, reaching values as large as

![]() $-2.10$

dex (SAGE),

$-2.10$

dex (SAGE),

![]() $-1.63$

dex (GAEA), and

$-1.63$

dex (GAEA), and

![]() $-1.19$

dex (SHARK). These biases indicate that, without modification, the virial theorem systematically underestimates halo masses, especially in the low-mass regime, highlighting the need for improved halo mass estimates in group environments. Given these limitations, it is essential to develop improved approaches for halo mass estimation in group environments. In the following section, we present a calibrated virial theorem estimator designed to address these shortcomings and provide more reliable halo mass measurements.

$-1.19$

dex (SHARK). These biases indicate that, without modification, the virial theorem systematically underestimates halo masses, especially in the low-mass regime, highlighting the need for improved halo mass estimates in group environments. Given these limitations, it is essential to develop improved approaches for halo mass estimation in group environments. In the following section, we present a calibrated virial theorem estimator designed to address these shortcomings and provide more reliable halo mass measurements.

4.1.2. Calibration of the modified virial theorem

While the virial theorem provides a physically motivated starting point, its direct application to observed galaxy groups is complicated by departures from equilibrium, projection effects, and uncertainties in group membership, especially for low-multiplicity systems (Robotham et al. Reference Robotham2011; Muldrew et al. Reference Muldrew2012; Old et al. Reference Old2015). To account for these effects, we introduce an MVT, which includes a scale factor, A, to Equation (3) and corrects the mass estimate based on the measured velocity dispersion and projected radius of the group:

where A is a function of both velocity dispersion and group radius. The calibration of A is essential to ensure unbiased halo mass estimates across the full range of group halo masses.

The calibration of the MVT was performed using a Bayesian framework, employing Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to explore the posterior probability distribution of the model parameters. The likelihood function was constructed to minimise the scatter in

![]() $\log M_{\mathrm{halo}}\,(M_{\odot})$

at fixed predicted halo mass, effectively minimising

$\log M_{\mathrm{halo}}\,(M_{\odot})$

at fixed predicted halo mass, effectively minimising

![]() $\chi^2$

and maximising the log-likelihood. Convergence of the MCMC chains was assessed via autocorrelation analysis. Further details of the likelihood function and the Bayesian inference methodology are provided in Appendix A.

$\chi^2$

and maximising the log-likelihood. Convergence of the MCMC chains was assessed via autocorrelation analysis. Further details of the likelihood function and the Bayesian inference methodology are provided in Appendix A.

A suite of functional forms for the correction terms

![]() $A_{\sigma}$

and

$A_{\sigma}$

and

![]() $A_{R}$

were tested, including exponential, inverse square, linear, logistic, and sigmoid decay models. The power-law form was found to provide the best fit to the simulation data, as quantified by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), outperforming alternative models by a substantial margin. The final adopted form for the A coefficient is:

$A_{R}$

were tested, including exponential, inverse square, linear, logistic, and sigmoid decay models. The power-law form was found to provide the best fit to the simulation data, as quantified by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), outperforming alternative models by a substantial margin. The final adopted form for the A coefficient is:

with the power-law decay models for

![]() $A_{\sigma}$

and

$A_{\sigma}$

and

![]() $A_{R}$

given by:

$A_{R}$

given by:

where

![]() $\alpha$

,

$\alpha$

,

![]() $\sigma_{\lim}$

,

$\sigma_{\lim}$

,

![]() $n_1$

,

$n_1$

,

![]() $\unicode{x03B2}$

,

$\unicode{x03B2}$

,

![]() $R_{\lim}$

, and

$R_{\lim}$

, and

![]() $n_2$

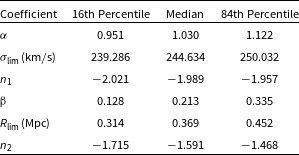

are free parameters determined by the MCMC sampling. The resulting posterior distributions for all model parameters are presented in Figure A1 in Appendix A, demonstrating that the parameters are well-constrained. The best-fitting parameters for the MVT are given in Table 1 for convenience.

$n_2$

are free parameters determined by the MCMC sampling. The resulting posterior distributions for all model parameters are presented in Figure A1 in Appendix A, demonstrating that the parameters are well-constrained. The best-fitting parameters for the MVT are given in Table 1 for convenience.

Notably, the calibrated

![]() $A_{\sigma}$

and

$A_{\sigma}$

and

![]() $A_{R}$

coefficients decay to zero at the fitted velocity dispersion and group radius limits, reflecting that for larger multiplicity groups, the velocity dispersion and radius are well-defined and no further modification is required. Above these limits, the MVT (Equation 6) reduces to the virial theorem (Equation 3). This procedure ensures that the MVT estimator is unbiased and robust across the full range of group properties, with well-quantified uncertainties and minimal model dependence.

$A_{R}$

coefficients decay to zero at the fitted velocity dispersion and group radius limits, reflecting that for larger multiplicity groups, the velocity dispersion and radius are well-defined and no further modification is required. Above these limits, the MVT (Equation 6) reduces to the virial theorem (Equation 3). This procedure ensures that the MVT estimator is unbiased and robust across the full range of group properties, with well-quantified uncertainties and minimal model dependence.

To convert halo masses between different values of the Hubble parameter

![]() $H_0$

(or Hubble constant h), the following scaling should be applied:

$H_0$

(or Hubble constant h), the following scaling should be applied:

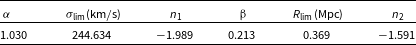

Table 1. Best-fitting parameters for the calibrated virial theorem relation.

where

![]() $R_{\lim}^{'}$

is the group radius limit for a newly chosen h’, and h is the value used in this work (

$R_{\lim}^{'}$

is the group radius limit for a newly chosen h’, and h is the value used in this work (

![]() $h=0.7$

). For example, converting to

$h=0.7$

). For example, converting to

![]() $h'=0.67$

yields

$h'=0.67$

yields

![]() $R_{\lim}^{'} = 0.369\cdot \frac{0.7}{0.67}=0.386$

Mpc. Alternatively, a factor of

$R_{\lim}^{'} = 0.369\cdot \frac{0.7}{0.67}=0.386$

Mpc. Alternatively, a factor of

![]() $\log_{10} (h'/h)$

can be added to the calculated

$\log_{10} (h'/h)$

can be added to the calculated

![]() $M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

from Equation (6) when using the

$M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

from Equation (6) when using the

![]() $R_{\lim}$

in Table 1. The calculated projected group radius for a given group should also be recalculated for the chosen h value.

$R_{\lim}$

in Table 1. The calculated projected group radius for a given group should also be recalculated for the chosen h value.

4.1.3. MVT – Accuracy, uncertainty and use cases

The MVT is calibrated to Shark, we then quantify the calibration accuracy and uncertainty on Shark and cross-validate the calibrated estimator to both SAGE and GAEA. The bottom panels of Figure 4 present a quantitative comparison between the predicted halo mass from the MVT (Equation 6) and true halo masses for each model (calibrated to

![]() $z \lt 0.1$

and

$z \lt 0.1$

and

![]() $i\lt19.2$

mag). The accuracy of the MVT is characterised by the mean offset (mean

$i\lt19.2$

mag). The accuracy of the MVT is characterised by the mean offset (mean

![]() $\Delta$

) between the predicted and true halo masses, while the uncertainty is quantified by the mean of the

$\Delta$

) between the predicted and true halo masses, while the uncertainty is quantified by the mean of the

![]() $16{\mathrm{th}}$

and

$16{\mathrm{th}}$

and

![]() $84{\mathrm{th}}$

percentiles (mean

$84{\mathrm{th}}$

percentiles (mean

![]() $\sigma$

) of the residuals. These metrics are shown in the bottom panels of Figure 4 as a function of the predicted halo mass for each simulation. On the calibration model (Shark), the mean

$\sigma$

) of the residuals. These metrics are shown in the bottom panels of Figure 4 as a function of the predicted halo mass for each simulation. On the calibration model (Shark), the mean

![]() $\Delta$

is

$\Delta$

is

![]() $-0.01$

dex, with a mean

$-0.01$

dex, with a mean

![]() $\sigma$

of

$\sigma$

of

![]() $0.20$

dex, indicating negligible systematic bias and moderate scatter. On the validation models; SAGE yields a mean

$0.20$

dex, indicating negligible systematic bias and moderate scatter. On the validation models; SAGE yields a mean

![]() $\Delta$

of

$\Delta$

of

![]() $0.12$

dex and a mean

$0.12$

dex and a mean

![]() $\sigma$

of

$\sigma$

of

![]() $0.10$

dex, while the GAEA model exhibits a mean

$0.10$

dex, while the GAEA model exhibits a mean

![]() $\Delta$

of

$\Delta$

of

![]() $0.07$

dex and a mean

$0.07$

dex and a mean

![]() $\sigma$

of

$\sigma$

of

![]() $0.13$

dex. These results demonstrate that the calibration procedure effectively removes systematic biases and reduces scatter across the full mass range and for all group multiplicities. The calibrated relation yields a high degree of consistency in both normalisation and slope across the models compared to the traditional virial theorem estimator (top panels), with only minor differences from the true halo mass, particularly at the low-mass end in the GAEA model. The small variance in the calibrated relation between the different models reflects the minimal dependence of the virial theorem on the details of baryonic physics, as it is fundamentally anchored in gravitational dynamics. However, some residual differences are observed, particularly in the low-mass regime for the GAEA simulation.

$0.13$

dex. These results demonstrate that the calibration procedure effectively removes systematic biases and reduces scatter across the full mass range and for all group multiplicities. The calibrated relation yields a high degree of consistency in both normalisation and slope across the models compared to the traditional virial theorem estimator (top panels), with only minor differences from the true halo mass, particularly at the low-mass end in the GAEA model. The small variance in the calibrated relation between the different models reflects the minimal dependence of the virial theorem on the details of baryonic physics, as it is fundamentally anchored in gravitational dynamics. However, some residual differences are observed, particularly in the low-mass regime for the GAEA simulation.

The robustness of the calibrated relation was further tested by varying the magnitude and redshift limits. When imposing a fainter WAVES-wide magnitude limit (

![]() $Z \lt 21.2$

), the free parameters changed by 1–20%, with the correction factor decreasing due to the deeper limiting magnitude. Extending the redshift range to

$Z \lt 21.2$

), the free parameters changed by 1–20%, with the correction factor decreasing due to the deeper limiting magnitude. Extending the redshift range to

![]() $z \lt 0.3$

resulted in larger changes of 5–40% in the free parameters, as stronger corrections were required as a function of redshift. These tests demonstrate that the calibrated relation presented here is specifically tailored to GAMA-like selection criteria (i.e.

$z \lt 0.3$

resulted in larger changes of 5–40% in the free parameters, as stronger corrections were required as a function of redshift. These tests demonstrate that the calibrated relation presented here is specifically tailored to GAMA-like selection criteria (i.e.

![]() $i \lt 19.2$

) and to

$i \lt 19.2$

) and to

![]() $z \lt 0.1$

. Users applying this relation to datasets with different selection functions or redshift limits should be aware of the potential systematic biases that may arise when doing so and a recalibration of the relation for their specific survey parameters is suggested. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the application of the calibrated relation to non-ideal datasets remains preferable to relying solely on the traditional virial theorem, which does not account for selection effects or redshift-dependent biases.

$z \lt 0.1$

. Users applying this relation to datasets with different selection functions or redshift limits should be aware of the potential systematic biases that may arise when doing so and a recalibration of the relation for their specific survey parameters is suggested. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the application of the calibrated relation to non-ideal datasets remains preferable to relying solely on the traditional virial theorem, which does not account for selection effects or redshift-dependent biases.

In summary, the MVT is the least model-dependent method considered in this work, as it does not require knowledge of galaxy properties or detailed prescriptions for baryonic processes amongst the models. This makes it ideally suited for applications where unbiased halo mass estimates are required, such as the construction of the halo mass function (HMF) in spectroscopic surveys or the derivation of cosmological parameters from group catalogues, provided that the relation is applied to the appropriate dataset.

4.2. The summed stellar-to-halo mass relation

The connection between the stellar content of galaxies and their host dark matter haloes is a cornerstone of galaxy formation theory, providing a critical link between observable baryonic properties and the underlying dark matter distribution (Behroozi, Conroy, & Wechsler Reference Behroozi, Conroy and Wechsler2010; Moster, Naab, & White Reference Moster, Naab and White2013; Wechsler & Tinker Reference Wechsler and Tinker2018). While abundance matching and halo occupation models have traditionally been used to infer this relationship on a statistical basis (e.g. Yang, Mo, & van den Bosch Reference Yang, Mo and van den Bosch2003; Vale & Ostriker Reference Vale and Ostriker2004; Behroozi et al. Reference Behroozi, Conroy and Wechsler2010; Moster et al. Reference Moster, Naab and White2013; Kravtsov et al. Reference Kravtsov, Vikhlinin and Meshcheryakov2018), direct group-based approaches offer a powerful means to calibrate halo mass estimators for individual systems (e.g. Viola et al. Reference Viola2015; Lim et al. Reference Lim2021), particularly in the group regime where dynamical methods become less reliable at low multiplicity (Old et al. Reference Old2015; Muldrew et al. Reference Muldrew2012).

4.2.1. Summed stellar mass proxy

In this section, we establish an empirical sSHMR between the summed stellar masses of the three most massive galaxies in a group (

![]() $\Sigma M_{*,\mathrm{3}}$

) and the group halo mass (

$\Sigma M_{*,\mathrm{3}}$

) and the group halo mass (

![]() $M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

). This approach is motivated by the expectation that the most massive group members should provide the most reliable baryonic tracers of the underlying halo mass. By summing the stellar mass of the three most massive galaxies, this method should mitigate stochasticity compared to a typical single galaxy tracer via a stellar-to-halo mass relation (SHMR). The choice of three galaxies represents a balance between competing factors, using only the most massive galaxy may introduce excessive scatter and result in a steeper high-mass slope in the SHMR, where small changes in stellar mass would produce disproportionately large changes in the estimated halo mass. Conversely, extending the sum to more galaxies may yield diminishing returns while adding noise from less reliable tracers. Summing over the three most massive galaxies should flatten the relation at the high-mass end and provide a more stable and physically motivated estimator. Additionally, we assess the robustness of this relation by varying the selection criteria from the GAMA-like limit (

$M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

). This approach is motivated by the expectation that the most massive group members should provide the most reliable baryonic tracers of the underlying halo mass. By summing the stellar mass of the three most massive galaxies, this method should mitigate stochasticity compared to a typical single galaxy tracer via a stellar-to-halo mass relation (SHMR). The choice of three galaxies represents a balance between competing factors, using only the most massive galaxy may introduce excessive scatter and result in a steeper high-mass slope in the SHMR, where small changes in stellar mass would produce disproportionately large changes in the estimated halo mass. Conversely, extending the sum to more galaxies may yield diminishing returns while adding noise from less reliable tracers. Summing over the three most massive galaxies should flatten the relation at the high-mass end and provide a more stable and physically motivated estimator. Additionally, we assess the robustness of this relation by varying the selection criteria from the GAMA-like limit (

![]() $i \lt 19.2$

) to a fainter WAVES-wide limit (

$i \lt 19.2$

) to a fainter WAVES-wide limit (

![]() $Z \lt 21.2$

) and by extending the redshift range from

$Z \lt 21.2$

) and by extending the redshift range from

![]() $z \lt 0.1$

to

$z \lt 0.1$

to

![]() $z \lt 0.3$

, examining how the relation responds to different survey parameters.

$z \lt 0.3$

, examining how the relation responds to different survey parameters.

4.2.2. sSHMR calibration and functional form

We use the same MCMC methodology as in Section 4.1.2. The likelihood function was constructed to minimise the scatter in

![]() $\log$

$\log$

![]() $M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

at fixed

$M_{\mathrm{halo}}$

at fixed

![]() $\log \Sigma M_{\star, \, 3}$

; convergence was assessed via autocorrelation analysis. The resulting posterior distributions for the model parameters are shown in Figure B1, and further details of the likelihood function, the fitting methodology and the uncertainty of the fitted parameters are provided in Appendix B.

$\log \Sigma M_{\star, \, 3}$

; convergence was assessed via autocorrelation analysis. The resulting posterior distributions for the model parameters are shown in Figure B1, and further details of the likelihood function, the fitting methodology and the uncertainty of the fitted parameters are provided in Appendix B.

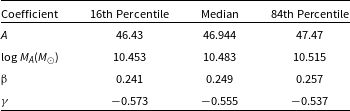

The adopted functional form for the sSHMR is a double power-law in the form:

where

![]() $\Sigma M_{*,\mathrm{3}}$

is the sum of the stellar masses of the three most massive galaxies in the group in units of

$\Sigma M_{*,\mathrm{3}}$

is the sum of the stellar masses of the three most massive galaxies in the group in units of

![]() $M_{\odot}$

, A is the normalisation,

$M_{\odot}$

, A is the normalisation,

![]() $M_A$

is the characteristic stellar mass in units of

$M_A$

is the characteristic stellar mass in units of

![]() $M_{\odot}$

, and

$M_{\odot}$

, and

![]() $\unicode{x03B2}$

and

$\unicode{x03B2}$

and

![]() $\gamma$

are the low- and high-mass slopes, respectively. The best-fitting parameters from the MCMC sampling are summarised in Table 2.

$\gamma$

are the low- and high-mass slopes, respectively. The best-fitting parameters from the MCMC sampling are summarised in Table 2.

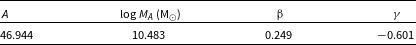

Table 2. Best-fitting parameters for the summed stellar mass–halo mass relation.

To convert the SHMR between different values of the Hubble parameter

![]() $H_0$

(or h), the following scaling should be applied:

$H_0$

(or h), the following scaling should be applied:

where

![]() $M_{A}^{'}$

is the characteristic stellar mass for a newly chosen

$M_{A}^{'}$

is the characteristic stellar mass for a newly chosen

![]() $h^{'}$

, and h is the value used in this work (

$h^{'}$

, and h is the value used in this work (

![]() $h=0.7$

). For example, converting to

$h=0.7$

). For example, converting to

![]() $h^{'} = 0.67$

yields

$h^{'} = 0.67$

yields

![]() $\log M_{A}^{'} = \log (10^{10.483} \cdot \frac{0.7}{0.67}) = 10.502$

. As the characteristic stellar mass is derived from simulations, there is only one factor of

$\log M_{A}^{'} = \log (10^{10.483} \cdot \frac{0.7}{0.67}) = 10.502$

. As the characteristic stellar mass is derived from simulations, there is only one factor of

![]() $h^{-1}$

rather than the typical

$h^{-1}$

rather than the typical

![]() $h^{-2}$

for observations. It is essential to ensure that both the stellar masses used in the sSHMR and the characteristic mass parameter

$h^{-2}$

for observations. It is essential to ensure that both the stellar masses used in the sSHMR and the characteristic mass parameter

![]() $M_A$

are consistently defined with respect to the chosen value of h. Any conversion of the sSHMR to a different Hubble parameter must be accompanied by a corresponding adjustment of these quantities.

$M_A$

are consistently defined with respect to the chosen value of h. Any conversion of the sSHMR to a different Hubble parameter must be accompanied by a corresponding adjustment of these quantities.

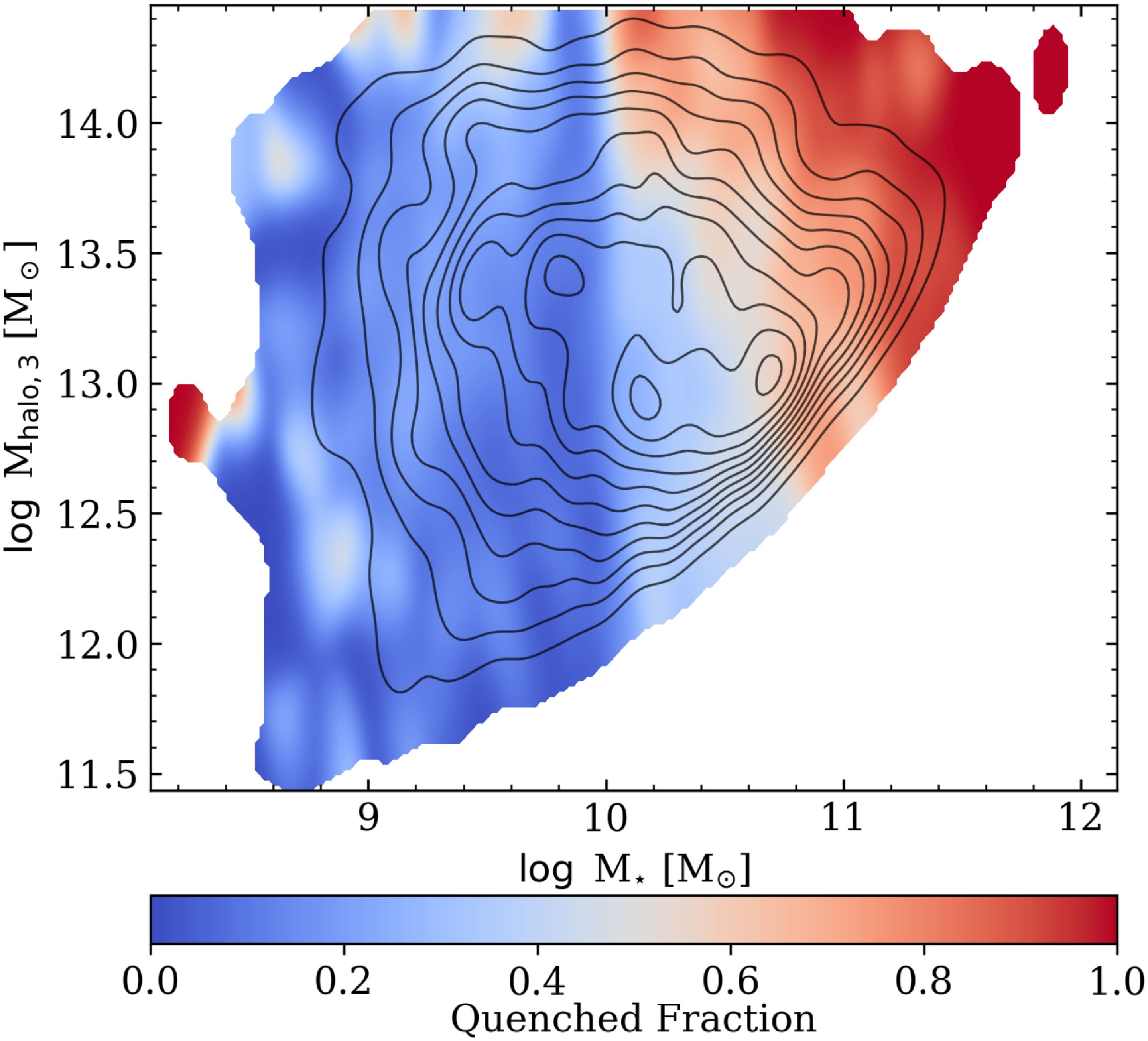

4.2.3. sSHMR – Accuracy, uncertainty and use cases

Following the same methods as in Section 4.1.3, the sSHMR is calibrated to Shark where we test the accuracy and uncertainty of this calibration, then we-cross validate this with SAGE and GAEA as independent tests. The accuracy of the sSHMR calibration is characterised by the mean

![]() $\Delta$

between the predicted and true halo masses, while the uncertainty is quantified by the mean

$\Delta$

between the predicted and true halo masses, while the uncertainty is quantified by the mean

![]() $\sigma$

. Both are presented in the second and last rows of Figure 5 as a function of both the sum of the primary three stellar masses (

$\sigma$

. Both are presented in the second and last rows of Figure 5 as a function of both the sum of the primary three stellar masses (

![]() $\Sigma M_{\star,\,3}$

) and the predicted halo mass (

$\Sigma M_{\star,\,3}$

) and the predicted halo mass (

![]() $M_{\mathrm{halo,\,3}}$

) for each model. On the calibration model (Shark), the mean

$M_{\mathrm{halo,\,3}}$

) for each model. On the calibration model (Shark), the mean

![]() $\Delta$

is

$\Delta$

is

![]() $0.01$

dex as a function of the summed masses, with a mean

$0.01$

dex as a function of the summed masses, with a mean

![]() $\sigma$

of

$\sigma$

of

![]() $0.12$

dex; as a function of the predicted halo mass, the mean

$0.12$

dex; as a function of the predicted halo mass, the mean

![]() $\Delta$

is

$\Delta$

is

![]() $0.02$

dex with a mean

$0.02$

dex with a mean

![]() $\sigma$

of

$\sigma$

of

![]() $0.14$

dex, indicating negligible systematic bias. Compared to the MVT in Section 4.1.3, the sSHMR achieves similar accuracy but with approximately half the uncertainty in the Shark model.

$0.14$

dex, indicating negligible systematic bias. Compared to the MVT in Section 4.1.3, the sSHMR achieves similar accuracy but with approximately half the uncertainty in the Shark model.

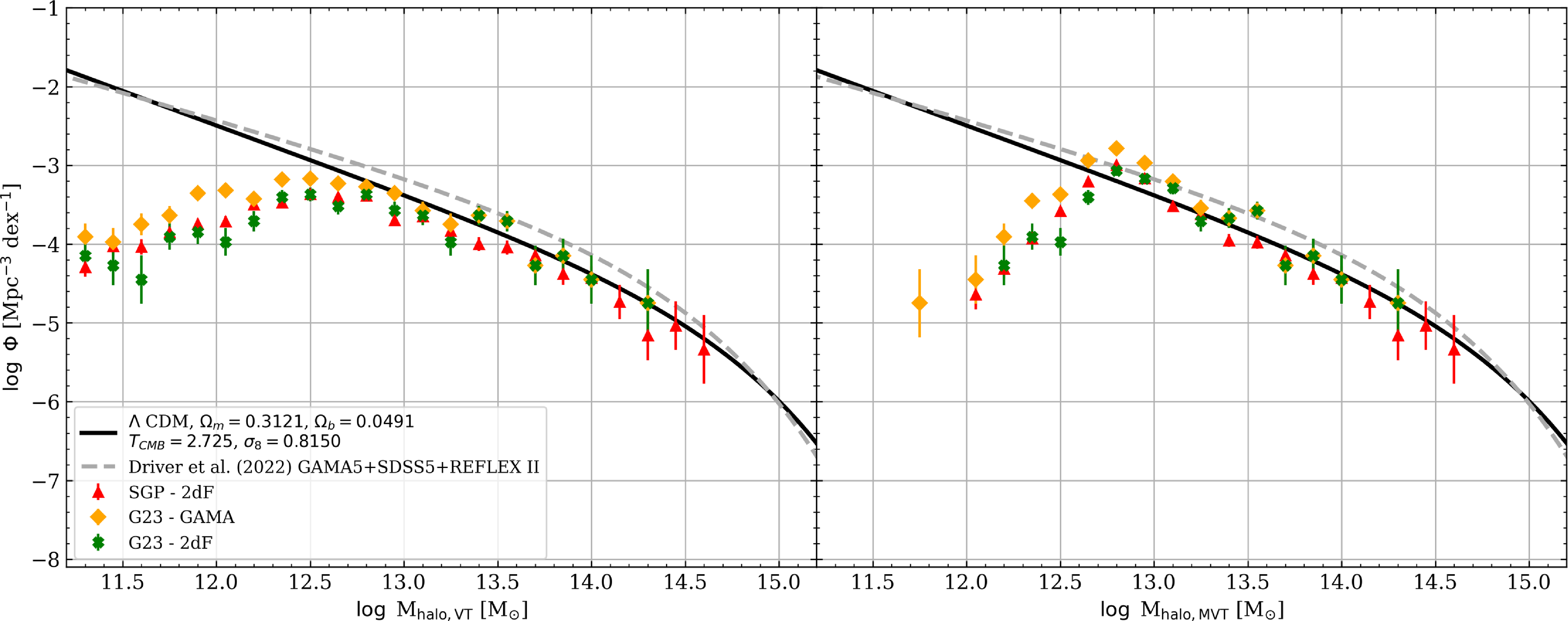

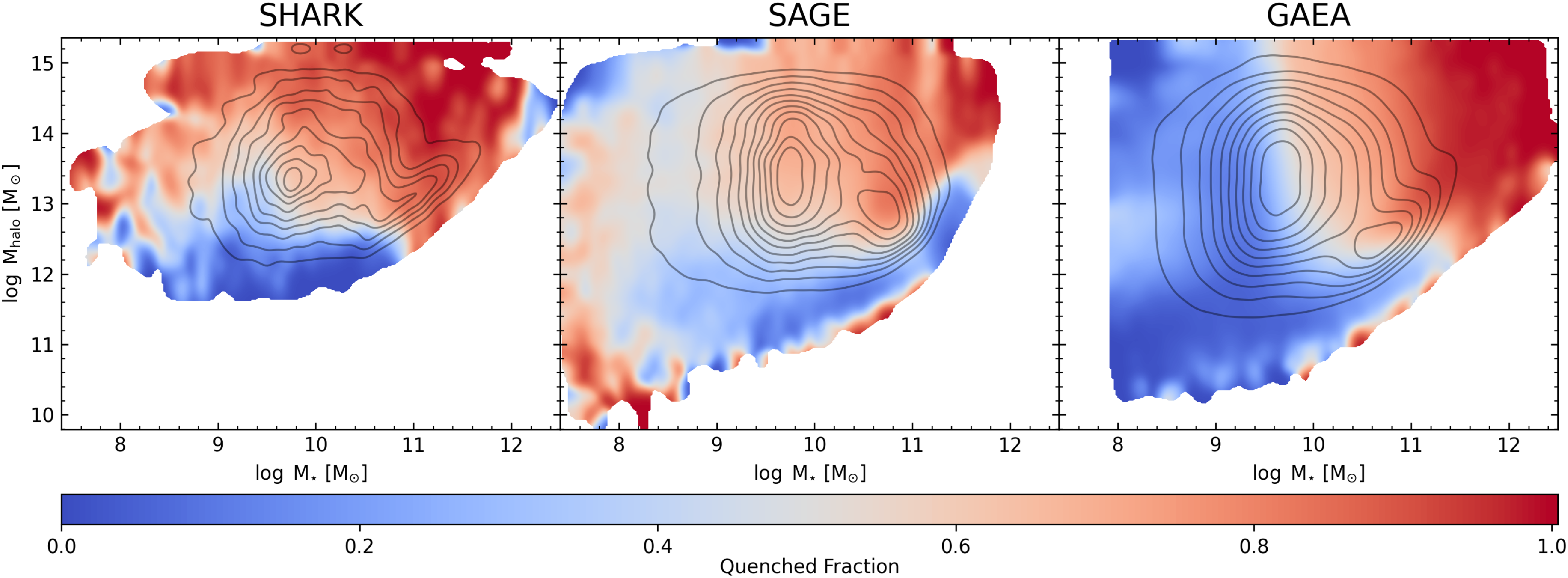

Figure 5. Comparison of baryonic and halo mass relations across three SAMs: Shark, SAGE, and GAEA. The Shark sample has a fainter magnitude limit of

![]() $Z\lt21.2$

and a deeper redshift limit of

$Z\lt21.2$

and a deeper redshift limit of

![]() $z\lt0.3$

compared to SAGE and GAEA (

$z\lt0.3$

compared to SAGE and GAEA (

![]() $i\lt19.2$

and

$i\lt19.2$

and

![]() $z\lt0.1$

). Top Row: The sSHMR using the summed stellar mass of the three most massive group galaxies (

$z\lt0.1$

). Top Row: The sSHMR using the summed stellar mass of the three most massive group galaxies (

![]() $\log \sum {M}_{*,3}$