[The romance] is a mine that contains precious treasures and true masterworks. Yes, grave philosophers, illustrious composers, who from the height of your academic thrones regard with a disdainful air all that does not have at least the dimensions of a one-act opera or a solfege, know that this melody, sprung from the heart, will be more respected by posterity than many weighty scores.Footnote 1

Paul Scudo’s 1850 admonishment to academics and composers underscores the immense popularity and cultural cachet of the nineteenth-century French romance. The strophic songs – characterized by their ‘sweet, natural, rustic’ melodies and amorous themes, according to Rousseau’s oft-cited definitionFootnote 2 – were ubiquitous in Paris, appearing in public concerts, operas, military barracks, working class choral societies, and above all, bourgeois and aristocratic salons and drawing rooms. During the July Monarchy, some 250,000 romances were printed each year, and popular songs like Amédée de Beauplan’s ‘Dormez donc mes chères amours’ sold as many as 40,000 copies in a few weeks.Footnote 3 Despite the romance’s historical significance, both economically and culturally, it has not – as Scudo envisioned – stood the test of time. The genre is all but absent from modern recitals, musicological histories and standard syllabi.

Though the reasons for this are undoubtedly multifaceted – including changing compositional and literary tastes in response to the popularity of Schubert’s Lieder in Paris, the perceived femininity of the romance, its nebulous position between commercial and art music, and, as William Cheng argues, our ‘collective prejudice against musical manifestations of ease and simplicity’Footnote 4 – the loss of the vocal performance practices that animated the genre has played a significant role.Footnote 5 Indeed, nineteenth-century critics insisted that the romance needed to be heard to be fully appreciated. In an 1842 concert review in the Revue et Gazette musicale de Paris, for instance, the anonymous author claimed that ‘it is necessary to hear mademoiselle [Loïsa] Puget herself to understand all the charm and often profound sensibility that her romances contain’.Footnote 6 In many ways, romances were, as David Tunley suggests, a singer’s art rather than a composer’s.Footnote 7 If it was largely in the act of delivery that sentiment and meaning were conveyed rather than in the notes of the score, it is to performance practices that we must turn to truly understand the nature and appeal of the genre.

In their 1881 Le chant – a work that is part treatise, part history of singing – Théophile Lemaire and Henri Lavoix fils offer a retrospective summary of the uniquely French manner in which salon singers interpreted romances:

We wish to speak of salon singers, of those who, not daring or not able to approach the theatre, dedicate themselves to a charming art, full of delicacy and taste, displaying a talent for diction, expression and virtuosity that our singers alone seem to have possessed … It is these artists who have given the romance such a large place in our French art; it is them who seem to have perpetuated through the centuries the national taste for simple music, it is true, but [music that is] tender, elegant, without false brio, and without exaggeration in its expressive effect.Footnote 8

Effective romance performances were delicate, tender and elegant, driven by subtle yet sincere word-based expression and an intimate aesthetic that differed from the more Italianate approach heard on the lyric stage. Numerous nineteenth-century writers emphasized and sought to preserve this interpretive juxtaposition. In an 1840 review of a salon performance by tenor Gustave-Hippolyte Roger, then singing at the Opéra Comique, Henri Blanchard wrote that his singing was too loud for the romances he performed: he sang ‘with his dramatic voice, which he should have restrained a bit to sing chamber music’.Footnote 9 Jacques Schoboerlichneraasfeldenberg (an amusing pseudonym) was more explicit in a review of Annette Lebrun, who sang at the Opéra Comique and the Opéra. He counselled her ‘not to deliver a simple and tender romance with the dramatic expression suitable for the juive Rachel when she is about to be thrown into a cauldron of boiling oil’.Footnote 10 The romance also depended on a sense of vocal individuality, a commitment to the unique sound of one’s natural voice that signalled sincere interior expression. According to Paul Thiébault in his 1813 Du chant, singing a romance required ‘more soul than voice’.Footnote 11

The primary element of this ‘soulful’ performance was, as I argue here, the sound of the voice itself, its timbre.Footnote 12 Nineteenth-century writers defined vocal timbre as both the unique quality that allows listeners to distinguish one individual’s voice from another’s and the myriad sounds that every individual voice is theoretically able to produce.Footnote 13 Here, I am more concerned with the latter, and I make two distinct though related claims. First, nineteenth-century French salon singers – especially in the first half of the century – cultivated a fundamentally different vocal technique than the one now taught in modern operatic studios.Footnote 14 This technique, based on the timbre clair (perhaps best translated as the ‘clear’ or ‘bright’ timbre), is bright, thin and delicate. It was heard as both individualistic and quintessentially French, intertwining timbre and identity in ways recalling work by Nina Sun Eidsheim.Footnote 15 A serious examination of this technique is necessary in order to more fully understand, and perhaps recreate, the sonic aesthetics of the Parisian salon; as John Potter convincingly argues, technique more than style defines sound worlds.Footnote 16 Second, though the timbre clair was the foundational or default timbre, singers were expected to continuously vary the colour of their voices to convey a song’s range of subtle sentiments.

In this article, I first explore descriptions of the ‘romance singer’s’ voice, drawing attention to ways in which it differed from the operatic voice. I then outline the timbre clair and the timbre sombre, explaining how each is physically produced and how the former’s aesthetic qualities, gender connotations, and links to both the French language and national identity relate to the romance. I conclude by exploring declamation practices, particularly timbral variation, in the romance, using ‘Pauvre enfant’ (a romance from Antoine Romagnesi’s L’art de chanter les romances) as a case study.Footnote 17 Ultimately, I hope that a better understanding of these timbral practices will allow us to reconnect sound with meaning, enabling us to hear how the romance captivated French audiences, and perhaps even returning it to modern concert programs.

Chanteurs de romances

By the mid-nineteenth century, ‘chanteur de romance’ (also commonly referred to as ‘chanteur de salon’) became a codified voice type, with its own characteristic sounds, style and look. Such singers often appeared in satirical physiologies, reflecting, as Mary Anne Garnett compellingly argues, broader attitudes related to gender and class transgressions.Footnote 18 Albert Cler, for instance, dedicates a section of his Physiologie du musicien (1841) to romance singers, deriding them for prioritizing fashion over musical talent.Footnote 19 He notes that they are usually short, stocky gentlemen with black coats and white cravats who must have shiny and curled hair (though often their ‘toupees are as false as [their] notes’), a vain portrait perfectly captured in an 1830 caricature by Henry Monnier (Figure 1).Footnote 20 Cler further insinuates that their craft was more commercial than artistic. After singing in spa towns like Baden-Baden or Aix over the summer, ‘our troubadour brings his commerce of couplets back to Paris’ where, ‘with the products of his labour’, he can even receive the croix d’honneur (a ‘reward for courage that would more appropriately suit’ his audience).Footnote 21 The author of the 1831 ‘Chanteur de salon’ in Le Figaro adds that salon singers championed French music and railed against Italian and German composers like Rossini (‘monotone’) and Meyerbeer (‘conceited’), a move that he positions as a self-serving effort to sell scores masquerading as patriotism.Footnote 22

Figure 1. Henry Monnier, ‘Un chanteur de romances’ (1830).

While a part of the salon singers’ commercial ability depended on their fashionable celebrity and entrepreneurial tenacity, the way in which they sang romances also surely contributed. In fact, I would argue that caricatures offer some of the most detailed accounts of the salon voice and style, despite comedic exaggeration. For instance, Jean-Baptiste Rosemond Beauvallon writes that the romance singer is invariably a tenor with a ‘weak, trembling’ voice that, ‘animated by a natural aversion for all that constrains and shackles, liberates itself from metre and detests the pitch’.Footnote 23 More optimistically, this suggests that they were tenors who possessed light voices and employed a great deal of tempo rubato. Satirists also highlight a penchant for nasality, with one claiming that the salon singer lacks a voice and lungs and instead ‘has nothing but a nose and makes the most of it’.Footnote 24 While this in part relates to the nasal sounds that characterize the French language, it further suggests a technique founded on the timbre clair (to be discussed below). Salon singers also used a variety of distinct character voices to dramatize the romance. As one satirist notes, ‘obligated to imitate the voice of Colette, of Jean-Jean, of a sapper and of Mayeux, [the salon singer] is a ventriloquist’.Footnote 25 For some, this dramatization was unnatural and exaggerated, especially given the typical age, physical characteristics and gender of the romance singer:

The romance singer is ordinarily a man over thirty, big, fresh and fat. It is in this state that he approaches the piano to sing of his sunken cheeks, his pallor, his thinness. Possessed of a particular affection for the murmuring wave, the chirping bird, the sighing wind, he always proposes promenades along the waters, reveries in the groves, and kisses in the zephyr. Then, suddenly, he cries: ‘Ma pauvre mère! Ma pauvre chaumière!’ and he is desolate, and he withers and dies like the flower of the field, still with that same rounded, rosy face that we have been talking about.Footnote 26

Serious critics also addressed romance singers, often juxtaposing them with opera singers. Some argued that singers associated with Paris’s lyric stages could and should modify their technique depending on venue, that celebrated artists shone in part because of their chameleon-like ability to sonically blend into their diverse environments.Footnote 27 As Antoine Elwart, Damour and Burnett write, stars like Giovanni Battista Rubini, Adolphe Nourrit and Cornélie Falcon ‘adopt a different tone than that of the theatre’ when singing in concerts and salons.Footnote 28 Some even wrote of the ‘romance singer’ as though it were a stage role, one that required its own unique approach and voice like any other. This idea can be seen in an 1866 review of tenor Placide Poultier’s final performance of Lucia di Lammermoor:

It was not only Edgard who received this ovation, it was Masaniello, Fernand and especially Georges Brown. It was also the romance singer. No one excels to the same degree as Poultier in these sweet melodies, in these tender cantilènes, these little sung recitatifs that he knows how to modulate so well. There, no effort: the singing flows from his lips like a pure spring.Footnote 29

The critic positions Poultier’s laudable abilities as a romance singer alongside, though separate from, his operatic accomplishments in works like La muette de Portici and La Dame blanche. The perceived ease and naturalness of his romance performances should not be overlooked.

Echoing the satirists, however, some critics held that salon singers possessed fundamentally different voices than opera singers, that they were truly a distinct voice type. Consider an 1839 review of Il barbiere di Siviglia: tenor Altairac ‘has one of those pretty voices, so common in the Midi of our France, with a bright and sweet timbre, without volume, but with an expansive range of falsetto notes (notes de fausset), a naturally flexible voice, lively, and easy to animate: a salon voice more than a theatrical one’.Footnote 30 Often, as Lemaire and Lavoix suggest above, the designation ‘salon voice’ was tied to amateurism, and was used to imply that the voice in question was not capable of successful operatic performance. But this incompatibility could cut both ways. When an inappropriate voice took on the romance, the results could be equally disappointing. In an otherwise glowing 1840 article on Jean-Auguste Dur-Laborde (first tenor at the Théâtre de la Renaissance), the author writes that ‘we would like the romance sung by what one calls a “salon voice” more than by a first tenor of grand opera, especially one with a voice as large as Dur-Laborde’s … to apply it to so slight a thing is to use Archimedes’s lever to lift a feather’.Footnote 31

Perhaps no singer exemplified the salon voice and style, was more associated with the romance, than le Chevalier Richelmi, a tenor who Jules Lovy characterized as the last true romance singer. Cast by one writer as ‘the soul of all our concerts’, Richelmi was one of the most successful non-operatic singers on the salon and concert circuit in the 1830s and 40s. Likely born in Nice, he arrived in Paris in the late 1820s where he developed a reputation as the ‘missionary of the romance’ and even ‘romance man’.Footnote 32 He also sang throughout France. An account of his tour with composer Aristide de Latour in the winter of 1841–42 showcases the commercial relationship between singer, composer, and the score:

For a romance to be savoured, it must be sung. No one more religiously observes this precept than MM. de le Tour [sic] and Richelmi: like our trouvères in the Middle Ages, these two nomadic apostles, these conjoined lyres, peddle their accents throughout all of France … Richelmi fears neither ice, nor seas, nor storms; at his sweet and vibrant voice, clouds dissipate, rivers suspend their course. If M. de la Tour were to lose M. Richelmi, we do not know what would happen in France.Footnote 33

Significantly, Richelmi’s singing alone (for better or worse) could secure the financial success of romances, further cementing the centrality of performance itself in the song tradition.

Accounts of Richelmi’s singing help to flesh out romance performance aesthetics. An 1829 review of a soirée hosted by the tenor characterized his voice as ‘neither loud nor rangy’, but tasteful and easy;Footnote 34 another drew attention to its noteworthy flexibility.Footnote 35 A review of an 1836 concert hosted by the Ménestrel lauds the ‘skilled concert singer’ for his phrasing, clear diction, and timbre.Footnote 36 Another claims that while he did not have the most beautiful voice, it was ‘the most touching of all’.Footnote 37 His expressivity was a strength, and critics noted his ability to draw listeners into the songs. One comments that when Richelmi sings, ‘we follow the murmuring stream, we breathe in a grove’s shade, we hear words of tenderness and love; we remain in contemplation and ecstasy, as if on a beautiful morning, embalmed with sweet perfume, we admire the sky and nature’.Footnote 38 Another writes that ‘his voice is not a voice, it is something simple and sweet, like the chirping of a warbler, which charms the ear and goes straight to the heart’.Footnote 39 Such avian imagery was so common that one critic wrote at the coming of spring: ‘Hello warbler! Hello goldfinch, sparrow and nightingale! Hello lovely virtuosos, small-footed Richelmis who populate the firmament’.Footnote 40 The constant references to birds and nature not only reflect the pastoral settings so common in romances, but also insist upon the perceived naturalness of Richelmi’s voice, suggesting that listeners heard it as devoid of artifice and labour.

With its smaller dimensions and unique timbre, critics claimed that Richelmi’s voice suited the romance, that ‘the tender and plaintive romance can no longer do without Richelmi’s silvery, fluted voice than a song (chant) by Meyerbeer without [Gilbert] Duprez’s great, powerful voice’.Footnote 41 Beginning in the late 1830s, several accounts of Richelmi’s voice directly target fanatics of Duprez (and other similar operatic singers), casting the salon singer as a kind of bulwark against that school of singing. In the Revue de l’Anjou et du Maine for instance, Éliacin Lachèse writes about concerts given in January 1839 that ‘the great success of the two concerts given by this artist can serve as a response to those who appreciate the range and sonority of the voice above all other qualities’.Footnote 42 He specifically contrasts Richelmi’s ‘pure organ’ (a code for naturalness and perhaps, as shall be seen, the use of the timbre clair) and delicate approach with the range and volume of operatic voices.

The timbres clair and sombre

While Richelmi and other salon singers likely possessed inherently smaller voices, their vocal technique helped to create the delicate, subtle and introverted aesthetic that defined successful romance performance. In their 1840 ‘Memoire sur une nouvelle espèce de voix chantée’, physiologists Paul Diday and Joseph Petréquin make a remarkable claim about singing romances: ‘the [voix] sombrée seems made mostly for our large lyric stages, and the voix blanche for opéras comiques and the romance’.Footnote 43 In essence, the romance (and the closely related opéra comique) required an entirely different method of vocal production than larger lyric works, like grand opera.Footnote 44 Diday and Petréquin identify two ‘species of voice’: the voix sombrée and the voix blanche, more commonly referred to as the timbre sombre (dark or sombre timbre) and the timbre clair. Their study speaks to a broader preoccupation with vocal timbre in mid-nineteenth-century France, prompted largely by Duprez’s famous 1837 ut de poitrine (chested high C) in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, and his corresponding preference for the timbre sombre. Footnote 45 Scholars like Gregory W. Bloch, J.Q. Davies and Sean M. Parr tend to focus on this new vogue for the timbre sombre within the operatic sphere and its relationship to registers (chest, voix mixte and head).Footnote 46 Their arguments are invaluable for understanding an important shift in French operatic aesthetics, and certainly intersect with the aims of this article. While broader histories of the voice, including those by John Potter and John Rosselli, reference the timbre clair, few claim that its loss has impacted the legacies of certain repertoires, particularly the lighter domestic genres that suffer from the darker, louder and heavier approach that now defines the classical voice.Footnote 47 In the following two sections, I explore how the timbre clair is produced and how it is physiologically and aesthetically different from the timbre sombre. I then tease out ways in which perceptions of the timbre clair relate to, and even reinforce, romance aesthetics, as well as conceptions of gender and national identity. Ultimately, I aim to broaden our understanding of how French listeners heard and understood the timbre clair and how, as I argue, it came to define the French voice, particularly – though not exclusively – in the salons.Footnote 48

Manuel Garcia fils explains how to physically produce both timbres in his seminal Traité complet de l’art du chant (1847).Footnote 49 The timbre clair is sung with a moveable larynx (for an illustration of the vocal anatomy, see Figure 2). At the bottom of the range, the larynx begins lower than its neutral position and rises as the pitch ascends. At each register shift – from chest to fausset (or voix mixte), and fausset to headFootnote 50 – the larynx resets to its lowest position before rising again with the pitch. At the top of each register, the larynx hits a point of ‘déglutation’ (swallowing), and the sounds become ‘thin and strangled’.Footnote 51 At the bottom of each register, the pharynx starts longer than in its neutral position; as the notes ascend, the pharynx shortens with the rising larynx. As this occurs, the soft palate and the tongue come together, the former lowering and the latter rising so that the larynx, soft palate and tongue nearly meet. With the lowered soft palate, the nasal cavities remain open in timbre clair, putting it at considerable odds with modern classical technique. Garcia recommends tilting the head back on higher notes, which softens the curve of the throat and allows the larynx to rise to the isthmus more easily.

Figure 2. Chart of the vocal anatomy from Enrico Delle Sedie, L’art lyrique (1874).

The timbre sombre is produced with a fixed larynx, held lower than its neutral resting position through all registers regardless of pitch. A slight expansion of the infrahyoid muscles at the front of the throat is all one sees externally, particularly when singing at full volume. Unlike the timbre clair, in the timbre sombre the soft palate starts arched and continues to rise in an ‘appreciable manner’, absolutely closing off the nasal cavities for all pitches above middle C.Footnote 52 For this timbre, the head tilts forward slightly as the pitch ascends, allowing the column of air to strike the raised soft palate. This is now a fundamental element of classical singing. For instance, though cautioning against an exaggerated depressed larynx, Richard Miller nonetheless argues that ‘following the slight [laryngeal] descent that accompanies inspiration, the larynx should then remain in a stabilized position. It should neither ascend nor descend, either for pitch or power … it should stay “put”’.Footnote 53

Writers across the nineteenth century offer consistent descriptions of the sounds and qualities of each of these timbres. Garcia describes the timbre clair as bright, pure and brilliant.Footnote 54 Stéphen de la Madeleine writes that the pharynx ‘does not permit the voice volume; but it gives it a brightness that all too easily becomes piercing’.Footnote 55 Diday and Petréquin add that the timbre clair is agile, precise and delicate.Footnote 56 In contrast, Garcia describes the timbre sombre as biting, full, covered, muted and round, with a greater capacity for volume.Footnote 57 Enrico Delle Sedie notes a greater ease with high notes.Footnote 58 Duprez, who purportedly introduced the technique to Parisian audiences, calls it full and sweet, indicating that it is produced with an open throat. Finally, several writers attribute a certain timbral homogeneity to the timbre sombre. In an 1839 letter to Louis Quicherat about learning the timbre sombre in Italy, Nourrit complained that he had to ‘adopt a certain kind of sonority that one cannot acquire except by sacrificing the fine and delicate nuances that permit a variety of effects and give each role a distinctive character’.Footnote 59 Diday and Petréquin state that the timbre sombre ‘does not display individual differences as distinctly as the voix blanche [timbre clair]’.Footnote 60 They then provide the pros and cons of the two timbres:

The sombre gives the singing more energy, but it removes a lot of agility; the voix blanche [timbre clair] has less force, but it retakes the advantage when speed becomes indispensable. The first has a slow and more solemn quality; the second offers more facility in its manner, more delicacy in its forms. The sound in this one is full, but veiled; in that one, it is bright, but a little thin. One transports and dominates with its power; the other seduces and captivates with its flexibility.Footnote 61

While Diday and Petréquin are the only writers to explicitly call for the timbre clair in the romance, it is possible to tease out support in other sources. Gustave Carulli, for instance, argues that romances should not be sung ‘in full voice’, a nod to the timbre sombre’s loudness.Footnote 62 More generally, descriptions of the romance mirror those of the timbre clair, including delicate, light and natural. This last term in particular resonates with Diday and Petréquin, who refer to the timbre clair as the voix ordinaire, or the standard, ‘natural’ voice.Footnote 63 The timbre sombre, by contrast, was considered pathological, artificial and false.Footnote 64 To nineteenth-century ears, it also sounded difficult to produce, awakening ‘in the spirit of the listener the idea that a punishing effort had been necessary to produce it’.Footnote 65 Concerning the romance, Thiébault asserts that obvious effort is outside the tradition: the romance ‘does not permit anything that shows or necessitates study or work’.Footnote 66 Such statements clearly resonate with descriptions of salon voices.

Antoine Romagnesi provides some of the best support for a timbre clair-based vocal production in his L’Art de chanter les romances, les chansonnettes, et les nocturnes (1846), a treatise dedicated to salon singing. Romagnesi not only published over 300 romances, but he also edited and contributed to the score periodicals Le Troubadour des salons (beginning in 1824) and L’Abeille musicale (1828–1839). He was, in essence, a romance specialist, hailed by Scudo as ‘one of the most active and charming glories’ of the genre.Footnote 67 Though he never mentions the two timbres, his treatise was written well after Duprez’s timbre sombre high C, and much of his language hints at a repudiation of such sounds in the romance. First, he claims that while dramatic singers possess ‘strong and rebellious voices’, salon singers have ‘modest, manageable’ ones: their gentle voices are the signs of a ‘delicate larynx’ that should not be overworked, echoing Thiébault’s statements above.Footnote 68 The most obvious evidence against the use of timbre sombre concerns male singers who ‘seek success in the manifestation of their powerful organ … they sing loudly rather than singing well’.Footnote 69 He cautions that tenors especially must ‘resist the vigour of their [vocal] organ and not confuse screams with expression’.Footnote 70 This is another clear reference to Duprez, and the school of singing he inspired. Cler similarly blames Duprez for increased tenor volume, and by extension the greater use of the timbre sombre: ‘Since the success obtained by the screams of Duprez in the famous “Suivez-moi!” from Guillaume Tell, the most meagre artistic frogs attempt to swell up in unison. Everyone screams at the Opéra and Opéra-Comique, and, in imitation, one screams even louder in salons’.Footnote 71 The reference to the swelling of frogs’ throats is reminiscent of Garcia’s description of the external signs of timbre sombre, particularly the visible expansion of the infrahyoid muscles.

Finally, some also began to perceive both the timbre clair and, by extension, the male salon voice as feminine, echoing widespread characterizations of the romance as a feminine genre.Footnote 72 Though quibbling with French terminology in his Mémoire sur la voix humaine (1847), Garcia claimed that, in Italy, the voix blanche signifies ‘the voices of women and children’.Footnote 73 In his 1852 Hygiène de la voix, Auguste Debay claimed that ‘a woman’s timbre is clair, velvety and dulcet; a man’s is less gentle, but fuller, more resounding. The former has something tender, voluptuous; the latter, more energetic, seems made for command’.Footnote 74 Male romance singers were also accused of singing like women.Footnote 75 De Limagne’s 1842 description of Monsieur Arnaud’s approach, for instance, recalls the timbre clair, linking such sounds to women’s sociability: ‘his singing absolutely resembles the conversation of a witty woman who does not speak too loudly and does not gesticulate excessively, because, thinking simply, she expresses herself in the same way’ (my emphasis).Footnote 76 Reviewing a concert at the Athénée Royal de Paris in 1842, meanwhile, another critic noted that Richelmi sang romances ‘with that feminine voice for which he is known’.Footnote 77 In a piece ridiculing the flurry of false death reports about the singer in 1845, Bartolo casts Richelmi’s entire persona in a feminine light, as something straight from a romance: ‘[provincial journals] announced with great regret that a virtuoso of the highest merit, someone like Duprez or Rubini, had just died in Nice of a languid illness – the death of a pretty woman, no less!’Footnote 78 The gender politics at play here are admittedly complicated. Such portrayals aimed, in part, to undermine the ‘feminine’ romance and its singers in favour of the ‘masculine’ Lieder of Schubert, complementing more common caricatures of the male salon singer as a social transgressor.Footnote 79 And yet, the way in which male romance singers sang perhaps contributed to this perceived femininity. Indeed, explicit remarks about the ‘feminine’ voices of the chanteurs de romances were often published after Duprez’s timbre sombre high C and a rapidly shifting preference for that sound in the public sphere.Footnote 80 At the risk of oversimplification, I would suggest that such singers’ continued use of the timbre clair in romances perhaps sounded ‘feminine’ when heard alongside the louder, darker, more strident voice of Duprez and his imitators, especially given its connection to the romance.

The timbre clair and Sounding French

Not all were enamoured with the darker, ‘masculine’ timbre of Duprez’s voice. In his 1852 Théories complètes du chant, for example, Stéphen de la Madeleine rails against the new vogue for the exclusive use of the timbre sombre, or what he calls ‘Duprez’s system’.Footnote 81 Though he argues that French singers knew about, and used, the timbre sombre well before Duprez, it had been considered an occasional effect rather than the norm. After 1837, however, he notes that French singers (especially tenors) quickly followed Duprez’s lead:

And then we shouted against the folly of imitation, when all the tenors of Paris, when all the singing students, tried to force their voices to fit into the system of this unassailable model. Alas! All these unfortunate singers, violently torn from the individuality of their talent, had no choice … In Paris, understudies were needed for the great master; Duprezes were needed in the rest of France … Were the unfortunate tenors, who hitherto had an honourable and peaceful career, free to remain themselves? They had to start their studies over. For it was no longer permitted for a tenor who had any respect for his talent to give a single note in timbre clair or fausset. Fausset, good God! Who would have been the unfortunate one so abandoned by God and by the voix sombrée to risk such inadequacy?Footnote 82

This invective supports several claims made earlier, including the idea that the timbre sombre was heard as anti-individual, representing a homogenized sound that undercut the unique qualities of each voice, and that a timbre sombre-based technique severely limited options for timbral manipulations. Significantly, the fact that French tenors had to relearn their technique to prioritize the timbre sombre also suggests that it was not previously the foundational element of their singing. Put another way, Madeleine positions the timbre clair as a hallmark of the French voice, at least prior to Duprez. He was not alone in doing so. Duprez himself connects timbre and national singing style, arguing about the timbre sombre that ‘the Italians have nothing but this manner of emission’.Footnote 83 Given that the romance was often cast as France’s ‘national’ song genre, it is worth establishing the links between timbre, language and national identity in some detail.

Nourrit’s letters from 1837 until his death in 1839 – written during his time in Italy, when he attempted to fundamentally change his singing technique – represent a fruitful starting point.Footnote 84 Though he died before the coining of the term by Diday and Petréquin, Nourrit states multiple times that he studied with Donizetti to become ‘an Italian singer’ by altering the ‘quality of [his] voice’.Footnote 85 He writes about the gulf between French and Italian singing with language that calls to mind the two fundamental timbres:

Even with mediocre singers, I find Italian accentuation, which seems to us exaggerated in France accustomed as we are to a reserved and respectable manner … [but that] truly gives a great power to music. This accentuation comes from the genius of the language … and that is what I must study and acquire. This is difficult for a Frenchman, for a Parisian especially: fortunately, I am of Gascon descent, and the southern accent gives me the key to the Italian method. The difficulty is great for singing: I must lose certain habits of vocal production that come from when I was 16 or 17 years old … [but] I am convinced that my voice will gain force, quality and surety. Footnote 86

Importantly, Nourrit links timbre to regional accent and language, arguing that his Gascon roots – and the corresponding southern accent – allowed him easier access to the Italianate timbre sombre. Elsewhere, he adds that the Italian voice is characterized by sonorousness and exteriority, while in France ‘we sing as we speak, with pinched lips and a certain restraint that constitutes good tone in France’.Footnote 87 Initially, Nourrit sought to strip away any hint of Frenchness from his voice, particularly nasality;Footnote 88 however, he soon began to regret that his embrace of the Italian method caused him to lose his French sounds, writing that ‘I no longer know how to sing French … I cannot recover my French inflections, my normal effects’.Footnote 89 He lamented losing ‘delicate nuances’ and ‘variety of inflections’, claiming that ‘with the Italian accent that I had fabricated, I no longer sang well because I had only one colour at my disposal’.Footnote 90 After renouncing his goal to become an Italian singer, he wrote of regaining his ‘natural timbre’Footnote 91: ‘I had recovered my natural accents; it was no longer with my throat that I sang, it was with my soul; I had become myself again’.Footnote 92 He had regained, in other words, both his vocal individuality and his French sound, his French timbre clair.

Adèle Nourrit, his wife, expressed dismay when she heard Adolphe’s new sombre Italian voice. She noted a lack of purity and a homogeneity in colour, as well as an inability to access his head voice or sing quietly.Footnote 93 To console herself, she rationalized the change: ‘I tell myself that Adolphe has a new role to play, that of an Italian singer, and that just as he transformed his voice and his allures to portray an old Jew, or a peasant, or a young knight, he transforms them today to sing à l’italienne’.Footnote 94 Later, she claims he ‘renounced the voix sombrée’, and that ‘by returning to his natural voice, recover[ed] some of the sounds (accents) that he had’.Footnote 95 She complained that Italian audiences did not desire ‘delicacy’, and that he ‘force[d] his voice; he sombre[ed] it as Donizetti requires’.Footnote 96 While she also points to an overuse of chest voice, it is surely significant that that she blamed a darker timbre for his vocal decline.

In 1867, Nourrit’s biographer Quicherat directly blamed the timbre sombre for the tenor’s vocal transformation, and for a more general (and in his opinion disastrous) shift in French singing. He characterizes the timbre sombre as a new Italian method first unsuccessfully introduced to Parisians in the 1820s by tenor Domenico Donzelli and soprano Benedetta Rosmunda Pisaroni. He notes that reviewers, including Fétis, highlighted certain qualities that would later become associated with the timbre sombre: forced sounds, a lack of agility, and monotony. After Duprez, however, it quickly came to dominate the operatic sound world, transforming into the ‘tenors’ gospel’.Footnote 97 Quicherat was especially concerned about Duprez as a pedagogue, about the almost messianic influence he had over his ‘apostles’ (who would soon become ‘martyrs’), writing that he ‘had to wage war on the natural production of sounds, to infuse his students with the sombre method’ which caused most of them to lose their ‘natural means’.Footnote 98 Other singers followed Duprez’s example in France, including François Joseph Schumpff. According to Paul Bernard, he was initially a salon singer who ‘then Italianized himself’ by not only adopting the stage name Morini, but by touring Italy.Footnote 99 He returned ‘completely Italian … and truly metamorphosed in every respect’, with notable changes in technique and vocal timbre.

On the flip side, evidence of a French preference for the timbre clair (prior to the mid nineteenth century) extends at least into the seventeenth century. In his Harmonie universelle (1636), for instance, Marin Mersenne states unequivocally that ‘the larynx rises when we sing high notes … and descends when we sing low notes’. Footnote 100 Jean-Antoine Bérard makes similar claims a century later in his L’art du chant (1755).Footnote 101 The continued dominance of the timbre clair in the first half of the nineteenth century can be inferred, in part, from negative descriptions of French singing. In his 1841 Music and Manners in France and Germany, Henry Fothergill Chorley castigates French tenors prior to Duprez, writing that in the French Pantheon of Art ‘few traces would be there found, it is true, of the well-toned and well-cultivated voices, which distinguished the great men of the Italian opera’.Footnote 102 Recalling statements seen in connection with romance singers above, he faults their nasality in particular, noting that it was common to say that ‘such or such a nose has a good voice’.Footnote 103 Carulli echoes this stereotype of French singers in his Méthode de chant (1838). In the dedication addressed to Duprez, he writes:

As one could not contest the superiority of Italian singers, one contented oneself by attributing it to the harmony and sonority of the Italian language without first verifying for oneself if their technique was the same as French singers.

So thus, it was the French language that caused so many nasal voices.

At last, you arrived! Tempered again in the classic land of singing [Italy], you came to give a ringing refutation of those unjust preconceptions.Footnote 104

The use of the timbre clair – with its low soft palate and open nasal cavities – likely contributed to the French nasality that both Chorley and Carulli contrast with Italian sonorousness.

Yet, like Carulli and Nourrit, numerous writers held that the French language itself explicitly encouraged or even necessitated the use of the timbre clair. Debay notes that there is an ‘intimate relationship’ between timbre and spoken language. The French, he writes, are recognized by their timbre clair because it is a distinguishing feature of the French language, as opposed to the Italian and Spanish timbre sombre and the German and Arab guttural timbre.Footnote 105 François-Achille Longet, in his Traité de physiologie (1852), writes that while Provençal and Italian singers favour the timbre sombre – ‘which characterizes the voices of various renowned singers and contributes to their intensity’ – the French ‘almost always sing in the timbre clair’ because the French language ‘hardly lends itself to the timbre sombre’.Footnote 106 Echoing this sentiment in 1869, Albert Deleschamps cautions that French singers cannot employ the timbre sombre exclusively, because it ‘denatures the timbre of certain letters’: that is, because it destroys certain characteristic sounds of the French language.Footnote 107

Longet’s differentiation between French timbre clair and Provençal timbre sombre points to broader post-Revolutionary arguments that increasingly tied the French language – and its ‘proper’ pronunciation – to French national identity.Footnote 108 David A. Bell, for instance, explores Jacobin efforts in 1794 to linguistically unify the nation by eradicating local languages or patois. As he writes, what had been ‘the language of the prince could only be called, in post-1789 France, the language of the nation. Therefore, once raised, the struggle for a generally accessible language immediately became the struggle for a national language, and as such entered irrevocably into the larger ideology of the nation’.Footnote 109 While initial revolutionary reforms were unsuccessful, many, particularly those who subscribed to a republican vision, continued to view language as proof of national disunity and backwardness that required ‘civilizing’.Footnote 110 Anne Judge notes that, since the sixteenth century, French writers and grammarians lauded the ‘perfection’ and ‘universality’ of the French language, a linguistic pride that led speakers of regional languages – or even speakers of regional French who developed accents in relation to standard French – to feel shame or develop an ‘inferiority complex’.Footnote 111 Katherine Ellis adds that post-Revolutionary regimes consistently tied French identity to centralization, and that ‘unity in uniformity’, linguistically speaking, might even prevent further revolutions. Such ideas very much influenced music: for proponents of a Paris-centric conception of Frenchness, ‘musical Paris signal[ed] musical France … Parisian practice implie[d] national conformity, or, at least, the expectation that provincials [would] aspire to emulate the capital’.Footnote 112 Indeed, one of the tasks of pedagogues training provincial singers to attend the Paris Conservatoire was to erase their regional accents, to (at least in part, as I argue) shift their timbre from sombre to clair.Footnote 113 That pedagogues consistently highlight the centrality of ‘pure, clear, natural’ pronunciation in romance performance ought to be read in the context of this broader nationalistic discourse.Footnote 114 In general, sounding appropriately ‘French’ had political and social implications and played a significant role in constructions of French identity.

The perceived Frenchness of the timbre clair was especially important in the romance, often positioned as France’s national song genre and even a musical symbol of French style and identity. François-Joseph Fétis claims that ‘the romance belongs to France … one cannot deny that it has conserved a certain je ne sais quoi that is the model of authentic French music’.Footnote 115 Scudo even more forcefully links the romance to both the French language and identity, asserting that the romance is as old as ‘the French language. Its history is intimately linked to the history of our literature, our customs and our civilization … [The romance] is the manifestation of French sensibility, grace and gallantry’.Footnote 116 Thiébault goes so far as to claim that it is ‘impossible to successfully sing romances … in front of foreigners, to whom the delicate charms of the genre and everything related to the subtleties of language must be lost’.Footnote 117 He also expressed anxieties, echoed by numerous writers throughout the first half of the century, that foreigners would alter the genre. He complains that they ‘seek to denature the romance, and transform it into a piece for study, difficulty and long attention’, and lauds the composers who protected the romance from that ‘contagion’.Footnote 118 Such concerns mirror complaints about the rise of the timbre sombre in France, which some compared to civilization-destroying foreign invasion. Madeleine, in his melodramatic way, viewed the rise of an exclusive use of timbre sombre as more disastrous for French art than the barbarian invasion was to the late Roman Empire.Footnote 119 In 1841, Henri Blanchard compared it to the most turbulent and violent events in the French Revolution, while nodding to heated debates surrounding the aesthetic: ‘[The timbre sombre] is an 89, a 93, an 18 fructidor, a revolution, a death-sentence, though others say a Restoration’.Footnote 120 By the 1860s, Quicherat bemoaned that the ‘decadence of the vocal arts in our century dates from the time when the timbre sombre became the foundation of singing’.Footnote 121 Prior to this, though opinions began to shift as early as the 1840s, the exclusive or majority use of timbre sombre was seen as foreign, homogenizing and artificial. A vocal production favouring the timbre clair – with its brightness, delicacy, individuality and even nasality – was a signal of Frenchness and an essential aspect of the romance aesthetic.

Declaiming the Romance

Though the timbre clair formed the foundation of French salon singing, Thiébault cautions that one should never prioritize a beautiful voice over expression, which he identifies as the ‘primary principle’ of the romance.Footnote 122 Thiébault continues that the romance must be ‘less sung than declaimed’, suggesting that theories and practices of declamation ought to serve as a starting point when attempting to understand what he meant by ‘expression’, or what ‘expression’ sounded like. Thiébault was far from the only writer to insist upon a declamatory approach. Carulli, for instance, claims that romances must ‘sometimes even be spoken’, and Garaudé advises singers to sing them with ‘true theatrical diction’.Footnote 123 Maurice Bourge, meanwhile, lauds tenor Gustave-Hippolyte Roger’s approach: ‘in the romance, he knows how to get a great effect from very modest means with the help of a finely accentuated (accentuée) declamation. He speaks more than he sings, but he speaks well’.Footnote 124

As Bourge indicates, accent is a key element of declamation. Though a definition of the accent – much less a clear translation into English – is thorny, several sources clarify its meaning. In his Théorie de l’art du comédien (1826), Aristippe de Maligny defines accent as ‘the pantomime of the voice; the soul of discourse, it gives sensibility and truth’.Footnote 125 Bernardo Mengozzi writes that ‘the sounds [a singer] produces and the words they pronounce gain an accent that is able, so to speak, to more powerfully touch and move [a listener] than the words and notes themselves’.Footnote 126 M.V.M Fourcade offers one of the clearest definitions:

… if it is easy to understand what one means by accent, it is not as easy to define; we will attempt to do so, and we will say that it is a certain particular and natural je ne sais quoi imprinted on a vocal sound or multiple vocal sounds that highlight this or that part of a word, this or that word of a phrase, this or that phrase of a discourse … The accent is also something that gives a general tone colour over the entire word, and so the effect is to paint sentiments and sensations. Finally, the accent is again all that … modifies that quality of vocal sounds to express thoughts and sentiments.Footnote 127

Accent is fundamentally an issue of sound, of manipulating vocal timbre to highlight key words and, more importantly, convey poetic meaning and sentiment.

The centrality of accent, of sound and colour, cannot be overstated in romance performance. Numerous sources directly link expression to vocal timbre. Here, writers move beyond basic technique – that is, strategies for producing the timbre clair – and instead detail ways of subtly altering this fundamental sound to develop a palette of accents to better depict emotion. Charles Delprat, for instance, writes that each piece must be given its proper accent, and that such expression ‘resides principally in the particular quality and timbre of the voice, in the soul of the singer who possesses it’.Footnote 128 Madeleine concurs, noting that the accent must be distinct enough that through timbre alone, the interjection ‘Ah!’ should be able to ‘paint many sentiments’, including physical pain, despair, anger, regret, satisfaction, pleasure and joy.Footnote 129 Here it is necessary to complicate the timbre clair and timbre sombre dichotomy. After all, Madeleine argues that rather than conceiving of the timbres as mutually exclusive, we should view them as two extremes of a single timbral spectrum: ‘the two qualities of timbre blend into each other like the brightest day passing into complete darkness by crepuscular degrees’.Footnote 130 He then argues that the expression ‘resides in the sound [of the voice] itself, that is to say in the vowel that contains a host of characters’.Footnote 131 Garcia agrees, arguing that ‘timbres are such an essential part of discourse, such a natural condition of sincere sentiments, that one cannot neglect the choice of one without invariably falling into falsehood’.Footnote 132 To use a single vocal colour, to strive for homogeneity of tone (even of beautiful tone), was not only monotonous, but dishonest.

Writers insist that singers must constantly vary timbre when singing romances. Thiébault cautions that, ‘in order to avoid monotony, one must take care to vary the manner of singing each couplet’.Footnote 133 Quicherat claims that Nourrit approached the romance the same way he did a role: ‘each formed a whole, imprinted with the same character, and each couplet received a finely grasped nuance, so as to satisfy all at once nature and the law of truth. He excelled at varying the return of refrains’.Footnote 134 Madeleine, meanwhile, states that he had to modify his timbre clair at times when singing romances: ‘I myself, low bass that I am, could not have sung, as I did in concerts, the most tender romances of madame [Pauline] Duchambge, of [Auguste] Panseron … if I did not have at my disposal, in the high notes of my chest register, the richness of the muted or sombre timbre’.Footnote 135 So great was the expectation for timbral variety that Madeleine refused to assign romances (easy though they appear) to his singing students because ‘it is almost always much harder to sing [than a cavatina], because a romance is typically a little highly dramatized poem that contains a host of nuances, oppositions and effects, and that therefore provides all the obstacles that I want to avoid when choosing music for singing students’.Footnote 136 In her article ‘De la romance’ (1835), Jeanette Lozaouis explains why the romance requires such variety, claiming that while arias tend to express one isolated subject and thus ‘touch only one heartstring’, romances are ‘complete dramas’ or even ‘abridged novels’.Footnote 137 In this respect, then, romances were more difficult to sing than Italianate arias, often calling for an exceptionally virtuosic command of vocal colour.Footnote 138

Reviews of romance performances often laud such a colourful declamatory approach. This was seen in writings on Richelmi cited above. It is also the case in those about performances by Loïsa Puget, who is now better known as a romance composer.Footnote 139 Numerous authors, including Scudo, attributed at least part of her compositional success to her performance abilities. Indeed, as the anonymous critic cited at the start of this article attested, hearing Puget sing allowed listeners to glimpse hitherto unknown depths in her romances. This notion was echoed in an 1841 article in Les Coulisses, which drew a clear link between her singing style and theatrical declamation: ‘listening to her, one witnesses the performance of so many little dramas, all pulsating with interest, of so many comedies full of gaiety, spirit and pleasing words. It is impossible to recount with the pen that clean and intense diction … those vocal inflections’.Footnote 140 Reviews of Puget’s concerts often highlight her ability to colour her voice:

Puget’s voice is not very extensive; it is a slightly weak instrument, and yet this weak voice works wonders with the airs that it modulates, with the words that it dresses. Mademoiselle Loïsa does not sing precisely: she says, she speaks, she narrates. At times full of sentiment and tenderness, of melancholy and of pain, at times loving and coquettish, gay and laughing, she paints the sentiments in all their diversity, she gives, with a precious flexibility, the tone and appearance that suits each of her spiritual compositions.Footnote 141

She moved her audience with her ability to appropriately ‘dress’ words, to give neutral or nude words meaning through metaphoric timbral costumes. Moreover, like the male salon singers discussed above, Puget apparently possessed a small, ‘slightly weak’ voice. As another critic claimed, she had ‘just enough voice’ to effectively sing.Footnote 142 Though potentially meant to be dismissive, such statements – coupled with comments by Scudo that her voice was a bit ‘shrill’Footnote 143 – nonetheless suggest a technique centred on the timbre clair. Ultimately, this light approach and emphasis on word colouring made her singing, according to one critic, akin to the most expressive poetry. As he writes, ‘Puget made me believe in everything that she sang (disait); [if] she had wanted me to laugh or to cry, I laughed or I cried’.Footnote 144

Expressive Timbre in Antoine Romagnesi’s ‘Pauvre enfant’

Romagnesi offers clues about how often timbre must shift to reflect sentiment by providing prose descriptions on how to perform ten romances at the end of L’Art de chanter la romance (1846). In ‘Ruth à Noëmi’, for instance, he calls for a ‘religious and sympathetic accent’; in ‘Les orphelins du moulin’, he asserts that the first part of each couplet must have ‘an accent of tenderness and of devotion’, giving way to a ‘tone of frankness and gaiety in the refrain’.Footnote 145 His description of the dramatic romance ‘Pauvre enfant’ indicates a number of timbral shifts (Example 1):

The surprised child seeks out his father whom he hoped to find next to him. Foiled in that expectation, his fear awakens … he searches … he moans … the voice thus rises; it takes on the tone of surprise and fear; then the following phrases, expressing the agitation of the child who calls his father across the countryside, must be sung faster up to the moment when the one whom he interrogates cannot help but cry out in despair: Pauvre enfant!Footnote 146

Example 1. Antoine Romagnesi, ‘Pauvre enfant’ from L’Art de chanter les romances, annotated using Delle Sedie’s timbral notation.

He instructs the singer to find appropriate timbres to express surprise, fear, agitation and despair, all within 22 bars.

The music itself aids the singer in this task by reinforcing the narrative Romagnesi describes, at least in the first strophe. The piano introduction establishes the key of C major, rendering it unnerving with an accented dissonant E over a D minor harmony (bar 2) and a chromatic A♭ (bar 3). The singer enters with a few bars of recitative (bars 5–8) that reaffirm C major. The harmonic stability highlights the comfort of the past as relayed by the child, when he slept in the arms of his father. The discovery of the father’s absence – and the corresponding ‘tone of surprise and fear’ – is depicted with an octave leap in the voice and a modulation to A minor. As the agitated child searches in vain, Romagnesi goes through a series of rapid tonicizations, starting in A minor, moving to F (both major and minor), and then back to C major through its dominant G. While the return to C major initially seems at odds with the ‘cry of despair’ that Romagnesi calls for on the lines ‘pauvre enfant’, it ultimately serves as a bit of foreshadowing. In the final strophe, the child meets a priest who invites him to the presbytery to ‘find a father’, and the despairing cry on ‘pauvre enfant’ that had ended the first two strophes transforms into a hopeful invitation. If C major originally depicted the child’s security in the arms of his father, its return at the end suggests that he will find similar comfort in the church. Given the strophic form, in which the words change and the music does not, the singer must vary their timbre to convey such radical shifts in meaning. The same holds true for the rest of the piece, and indeed the genre as a whole: to express changing narrative and sentiments in an equally effective manner throughout, singers must employ a host of vocal colours.

Returning to the first strophe, while Romagnesi calls for rapidly shifting timbres, he does not tell us what they sounded like or how to produce them physically. Fortunately, though their focus on opera limits the direct applicability of their larger ideas concerning style, Garcia and Delle Sedie help fill in the gaps. Garcia, for instance, theorized that timbre is created by laryngeal position (creating, as seen above, either the timbre clair or the timbre sombre) and the manner in which the folds of the glottis come into contact, which can modify the timbre clair or sombre to render it more brilliant (if the glottis is fully closed) or muted (if the glottis is partially closed).Footnote 147 This too runs counter to modern classical pedagogy, producing colours now more associated with musical theatre and popular music. Julia Davids and Stephen LaTour, for instance, note that firm glottal closure creates a heavy belt while relaxed glottal closure creates a breathy tone; classical technique tends to fall somewhere between, with consistently moderate glottal closure.Footnote 148 In any case, combinations of the variables introduced by Garcia – in conjunction with vocal effects like a hoarse or guttural voice, vocal flaws that can be exploited for expressive endsFootnote 149 – create unique timbres, which he then connects to specific sentiments.Footnote 150 He offers general advice on choosing timbres: (1) Sounds without brilliance (that is, muted sounds produced with a partially closed glottis) correspond to sentiments that ‘trouble the soul’, including tenderness, timidity, fear, confusion and terror;)2) Sounds with brilliance (produced with a fully closed glottis) express sentiments that excite the voice, including joy, anger, rage and pride; (3) Happy sentiments, or terrible ones ‘that explode with violence’, use the timbre clair; and (4) Serious, elevated, or restrained sentiments use the timbre sombre.Footnote 151 Finally, echoing Madeleine’s thoughts on a single timbral spectrum, he claims that the clair and sombre emerge from an intermediary point and move towards pure (or even exaggerated) extremes as the passions progress from soft or moderate sentiments to heightened sentiments.Footnote 152

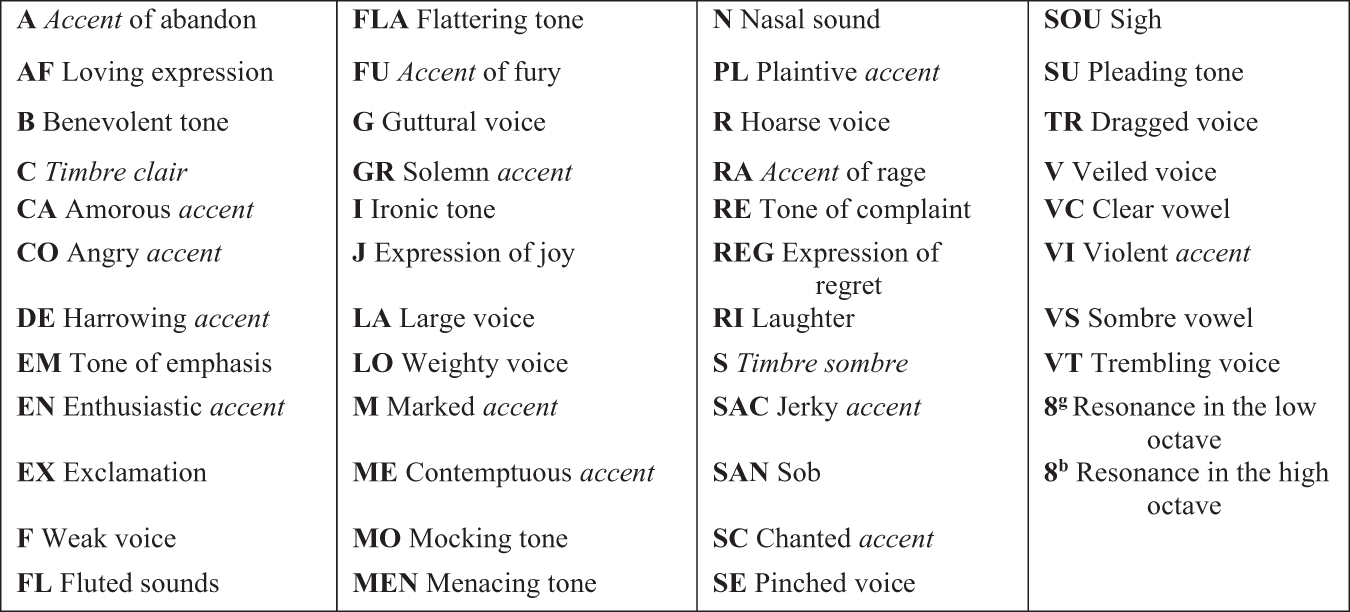

Delle Sedie also links sound to specific emotions, and his treatise provides a useful model for notating timbres and vocal effects in scores. He first shows his system in a series of vocalises meant to develop sound-based expression. To indicate the accent, timbre and vocal effects, he uses a series of letters above the staff (Figure 3).Footnote 153 Among the possible effects, which can be combined, are the timbres clair and sombre, sighs, a trembling voice, a veiled voice, a weak voice and sobs. Like Garcia, he also includes effects that he earlier defines as vocal flaws, including nasal and guttural tones.Footnote 154 Delle Sedie links these timbres and effects to far more specific and numerous passions than Garcia. His first vocalise, for instance, expresses ‘sad and sombre sorrow, almost without hope’ and includes shadings like ‘despondency’ and ‘the turning of thoughts to a regretted past’.Footnote 155 The first page alone, which has only 24 bars, contains 13 different combinations of vocal sounds to show profound grief, despair and reproach to adversity (Example 2). Though he is not as prescriptive as Garcia – specifically stating he seeks to help stretch students’ timbral flexibility, not to ‘create automatons’ – Delle Sedie vocalises demonstrate the radical timbre shifts expected by nineteenth-century audiences.

Figure 3. Expressive vocal colours and effects for vocalises in Enrico Delle Sedie, L’art lyrique: Traité complet de chant et de declamation lyrique (Paris: Léon Escudier, 1874): 91.

Example 2. Enrico Delle Sedie, ‘Première vocalise’ from L’Art lyrique, bars 1–24.

Once more, Garcia and Delle Sedie do not focus on salon singing; however, while vocal effects and timbral shadings were likely subtler (though more rapidly changing) in the romance, we can nonetheless draw inspiration from their treatises to begin to reconstruct what Romagnesi imagined in ‘Pauvre enfant’ when he calls for sounds of surprise, fear, agitation and despair (for an annotated score using Delle Sedie’s notation, see Example 1).Footnote 156 For surprise (bars 5–8), which in this context is better understood as uncertainty, Delle Sedie recommends the timbre sombre, a harrowing accent (achieved by fully closing the glottis), a halting accent (here aided by the breathless rests in the score) and a weak voice. Fear (bars 9–12), according to Garcia, ‘deadens the sound, rendering it sombre and hoarse’, meaning timbre sombre with a partially closed glottis to mute the sound, creating perhaps what Delle Sedie calls a veiled voice. To show the child’s moaning (a sentiment akin to Delle Sedie’s ‘reproach to adversity’) on the line ‘ô douleur amère’ (bar 9), one can employ a guttural tone and a heavy voice. Agitation (bars 10–16) demands the timbre clair, and the child’s despondency can be heightened with a guttural and trembling voice. The narrator’s entrance (bar 17) can be marked with a change to restrained grief (timbre sombre and a cavernous voice, which elsewhere Garcia describes as hoarse) before the explosion of despair on the line ‘pauvre enfant!’ (bar 20), which should be painted with an ‘open [clair], piercing, harrowing sound’, a guttural voice and sobs. By doing this kind of detailed timbral work – by constantly manipulating laryngeal position and glottal closure for expressive purposes – singers could, and still can, avoid the kind of monotonous or neutral performances that make the romance seem shallow or vacuous, and instead exploit and convey the deep emotional potential of these (to borrow from Lozaouis) ‘complete dramas’. Or, put another way, such work allowed (and allows) singers to use more soul than voice.

Conclusion

Though we cannot know for certain what each of these expressive timbres and effects truly sounded like, it is nevertheless clear that the romance required a greater variety of vocal colour than modern audiences are accustomed to hearing, at least in the realm of classical music. Sources like Delle Sedie and Garcia, which do not rely exclusively on metaphoric language and instead attempt to describe physical processes to produce various sounds, are particularly helpful when trying to understand this now-lost tradition. More generally, the preference for timbre clair-based technique and for subtly manipulated vocal colours were sonic exemplars of French salon aesthetics. These practices allowed performers to infuse the romance with meaning, to sing it with the delicacy and subtly that listeners prized. While not a complete answer, they also help explain why the genre declined as newer practices that arose in the late-nineteenth century stripped the romance of its primary means of expression. In many cases, these practices were decidedly louder. In others, especially those championed by singers associated with the mélodie such as Claire Croiza, Jane Bathori, or Charles Panzéra, practices began to reflect newer conceptions of l’art de dire, characterized by Katherine Bergeron as ‘deliberately dispassionate’ with emphasis on expressive consonants.Footnote 157 In other words, expression shifted away from infinitely coloured vowels favoured by romance singers to subtly and intentionally articulated consonants.

Yet, as Emily Kilpatrick has recently explored, the earlier salon aesthetics I have described endured at least in part into the twentieth century through amateur society singers like Maurice Bagès Jacobé de Trigny.Footnote 158 She notes that his voice was perceived as different from those of Conservatoire-trained singers, whose training largely focused on grand opera. Prized for his conversational tone, it is possible that Bagès even employed the timbre clair. Like the voices of the earlier chanteurs de romances, critics often described his voice as sweet, flexible and quiet – particularly his high notes. Recalling conceptions of the timbre sombre as pathological, Camille Benoît wrote that Bagès had ‘a voice that is fresh and natural, completely different from the artificial sounding voices of most singers, unaccustomed to transmitting, in their subtlety and vivacity, more intimate emotions’.Footnote 159 Though no recordings of Bagès’s voice exist, we might look to other singers of the time. Consider Anna Thibaud, a performer associated with the café-concert.Footnote 160 A 1905 article dedicated to her in Paris qui chante specifically indicates that

She knew how, in the romance (eminently French, though a bit castigated by so-called connoisseurs), to bring to bear true notes, emotional diction, and especially simplicity, which transformed the old romance (a little too catchy and sought after by barrel organs!) not into a sentimental song, but a song of sentiments.Footnote 161

Her popularity was partly built on nostalgia. According to the British society journal The Sketch, Thibaud ‘made a specialty of the songs of 1830’ and even wore pseudo historical costumes ‘to give a touch of local colour’.Footnote 162 Her singing approach, described as ‘simpler’ and ‘more human’, was similarly hailed as a ‘return’ to the past. As the author describes it, ‘every word of her song tells’. Though it is famously difficult to hear timbre in early recordings, recent work by Barbara Gentili and Daniele Palma on timbre in early operatic recordings convincingly argues that there is still much of value to hear through the distortion.Footnote 163 Thibaud’s 1913 recording of Désiré Dihau’s ‘Quand les lilas refleuriront’ (1890) not only gives a sense of her style, but is evocative of the older approach I have described in this article.Footnote 164 Her tone remains bright throughout, especially in higher passages. Her performance is also extremely declamatory, making judicious use of extreme tempo changes and tempo rubato to better convey a sense of the words.

While I am not the first to note the shift to a timbre sombre-based approach beginning (more-or-less) with Duprez in the 1830s, I would like to argue more forcefully that we ought to experiment with, and perform using, the timbre clair.Footnote 165 By continuing to fix the larynx in its lowered position – even as we have begun to seriously explore other nineteenth-century stylistic elements like ornamentation, tempo rubato, drastic tempo changes, and portamento – we have lost access to fully half of the historically used vocal colours that animated at least the romance, if not a host of other French vocal works.Footnote 166 It is, of course, fair to ask: would modern audiences accept these brighter and thinner sounds? They are, after all, not only fundamentally different from the classical singing aesthetics we now know and cherish, but bear resemblance to colours more commonly heard in musical theatre and contemporary commercial music. Quicherat had this same concern in 1867, when the timbre sombre began to define the operatic voice: ‘what will make it difficult to return to a more moderate art, a more restrained execution, is public taste. The ear gets used to noise like the palate to strong liquor: what we would have found deafening in 1830 seems today only to be warm.’Footnote 167 I find myself agreeing with his optimistic response several pages later when he claims that an artist with conviction, one who strongly and artfully makes a case for an expansion of acceptable timbres, can change public tastes.Footnote 168 Finally, I have sought to complement studies that champion the romance by identifying specific songs that might still appeal to modern performers and audiences. Tunley’s multi-volume Romantic French Song 1830–1870 in particular serves as an effective introduction to the genre, containing numerous pieces that he feels ‘deserve to be rescued’.Footnote 169 By focusing more on vocal techniques and performance practices, I hope to encourage readers to hear the genre as a whole with fresh ears and to provide singers with ideas on how to approach a repertoire that might initially appear lacklustre on the page. Ultimately, as we develop a more concrete sense of the aesthetics of the genre, and of the vital contributions of performers, it emerges not as vacuous or meaningless, but as a window into an essential French sound world.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Francesca Brittan and the anonymous readers for this Journal for their helpful feedback and guidance.

Nathan Dougherty is an Assistant Professor of Musicology and Director of the Collegium Musicum at the University of Oklahoma. His research focuses on late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century French song and song cultures, with recent publications on debates around women’s sexuality and expression in song and historical performance practices related to the romance. He is currently working on a monograph that explores the sentimental mode in the romance and how composers, poets, and performers harnessed it to comment on issues relating to race, gender, political exile, and animal rights and cognition. He also maintains an active career as a tenor, and has performed as a soloist and chamber singer with a number of American early music ensembles and chamber choirs, including Apollo’s Fire, Les Délices, The Newberry Consort, The Thirteen, Atlanta Baroque, Oklahoma Baroque Orchestra, and Trobàr. He received his PhD in Historical Musicology with an emphasis in Historical Performance Practices from Case Western Reserve University in 2022.