Introduction

Taking Pakistan as our exemplar, we focus in this article on large indigenous voluntary organizations and how they contribute to socio-economic development in developing nations; asking how and why such organizations are formed and gain traction to provide valuable services for large numbers of poor people in societies riddled with inequalities? Much of the development literature is focused on the responsibilities of richer countries to lesser developed countries and is presented as the main solution to enduring economic and social injustices (Holcombe, Reference Holcombe2014; Suárez & Gugerty, Reference Suárez and Gugerty2016). There is relatively little scholarship focusing on indigenous philanthropy or social entrepreneurship in countries like Pakistan. It is this imbalance we seek to help redress. In a world in which foreign aid is stretched increasingly thinly, devising local solutions is arguably a better approach to socio-economic problems (Appe & Pallas, Reference Appe and Pallas2018).

Pakistan, like many developing countries, suffers from multiple forms of deprivation. In 2018, according to the World Food Program, almost 44% of children under five were stunted and 18% suffered from malnutrition. Pakistan ranks 129 of 165 countries in the Global Hunger Index with 24.3% of its population living below the poverty line (UN HDR, 2019). In terms of education, Pakistan has the lowest government education expenditure as a percentage of GDP and per pupil in South Asia. In health care, spending likewise remains exceptionally low at under 1% of GDP (Hassan et al., Reference Hassan, Mahmood and Bukhsh2017), and consequently life expectancy in the country is just 67 years compared to averages of 70 for South Asia, 71 for all low- and middle-income countries, and 80 for high-income countries (World Bank, 2020). Yet, despite this, paradoxically, Pakistan can lay claim to being a generous country: the World Giving Index ranks it 41 of 126 countries (Charities Aid Foundation (CAF), 2019), with 1% of GDP devoted to philanthropic causes (Amjad & Ali, Reference Amjad and Ali2018). This giving rate is three times that of India and 33 times that of China (CAF, 2016).

Pakistan is a country that preferences relatively low rates of taxation over higher government spending on services in support of families, education, and health care (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Soucat and Kutzin2018). Systemic reforms have favoured making education and health care private rather than public goods (McGregor, Reference McGregor2001) or basic human rights (Chapman, Reference Chapman2014). The overall effect of these policies is to perpetuate inequalities. There are considerable disparities in income levels, housing standards, education, and health care provision between rural and urban areas in each of Pakistan’s five main administrative regions (Pasha, Reference Pasha2018). Urban areas generally have superior infrastructure, employment opportunities and access to schooling and medical facilities, fuelling migration from rural to urban areas (Khalid & Martin, Reference Khalid and Martin2017). Rural communities endure multiple forms of discrimination—in incomes, infrastructure, education, and health care—which all compound to increase inequities, disproportionately impacting on women who make up almost 80% of the workforce in the agricultural sector (Bano, Reference Bano2009).

Our paper unfolds as follows. First, we review the literature on the role of large philanthropically funded voluntary organizations in socio-economic development. The next section outlines the sources and methods underpinning our research. We then present our findings. In the ensuing discussion we make the case for concentrating philanthropic support on provenly efficient and effective voluntary organizations with the vision and organizational capabilities needed to operate at scale, across provinces and potentially nationally.

Philanthropy and Voluntary Organizations in Socio-economic Development

Conceptualizing Socio-economic Development

We define socio-economic development as the process of sustainably improving the well-being of collectivities such as social groups, communities, and nations. According to Sen (Reference Sen1999), socio-economic change is a process that places human freedoms at the centre stage. Greater freedoms make for increased opportunities for individuals to help themselves to lead a better life. Sen argues that a lack of freedom is directly linked to persistent poverty, hunger, illnesses, and illiteracy, and, therefore, the goal is to remove the barriers that restrict freedom. The necessary conditions that promote human freedom include economic, social, political, and cultural freedoms (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2003). These are interlinked and reinforce each other to promote and influence the development process; the basis of what Sen calls the capabilities approach. Economic freedom means freedom from hunger and poverty, access to finance, and availability of opportunities. Social freedom means freedom from social deprivations and access to social services such as education, health care, clean water, and sanitation (Carothers & de Gramont, Reference Carothers and Gramont2013). In short, development is a process that allows freedom of opportunity, enhancing the capabilities of individuals to participate in economic, social, and political activities. The absence of opportunities leads to the lack of basic capabilities to fight hunger, disease, illiteracy, limiting the ability of individuals to act and bring about change (Sen, Reference Sen2005).

Following the freedoms-capabilities approach to socio-economic development requires governmental commitment to democratic processes, the rule of law, and a supportive state that creates the macroeconomic and macrosocial conditions under which individuals might flourish (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2011; Sen, Reference Sen1999). It is predicated on the establishment of constructive partnerships between the state, the third sector and private enterprise (Singh & Prakash, Reference Singh and Prakash2010). Markets, state financing, and philanthropy each have a role to play in socio-economic development (Giloth, Reference Giloth2019). As the process unfolds, ever larger numbers within the population develop the capabilities needed to generate incomes and trade in markets. However, in the early stages, ideal conditions do not prevail, as a large proportion of the populace lacks the basic capabilities and purchasing power needed to function in extensively marketized economies. The necessity, therefore, is for the state and third sector, in some combination, proactively to provide or subsidise the cost of the freedoms-capabilities needed by people to develop themselves, grow their incomes and fully engage in society (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2011). Universal provision of educational opportunities, health care, and the knowledge, skills and infrastructure needed routinely to engage in buying and selling are thus critical to the process of socio-economic development.

The freedoms-capabilities approach has had a profound effect on thinking with policy circles within both developed and developing countries and international agencies (Miletzki et al., Reference Miletzki and Broten2017). Its appeal lies in the aspirational pursuit of social inclusion and equal opportunities, liberating individuals from the shackles of ignorance and ill health, as the best means of banishing poverty and socio-economic inequalities (Evans, Reference Evans2002). It suffers, however, from two obvious limitations. The first is excessive generalization and the failure sufficiently to recognize that freedoms and development processes inevitably are shaped locally by specific historical and contextual factors and that some freedoms and capabilities are more fundamental than others (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2003). The second is that development processes are often derailed by struggles for power and corruption within jurisdictions as elites—military, political and business—who perceive the ideal of social justice as running counter to their own hegemonic interests (Corbridge, Reference Corbridge2002). We accept these critiques as valid. They suggest that any well-founded approach to socio-economic development must be flexible enough to accommodate the particularities of history, elite power, and national circumstances. We add a third critique. The freedoms-capabilities approach, like other policy approaches, is largely silent on the organizational challenges involved in delivering freedoms and developing capabilities. Yet, when governments and markets fail to deliver, the creation of sustainable and scalable voluntary organizations is crucial in sustaining the process of socio-economic development (Westley et al., Reference Westley, Antadze, Riddell, Robinson and Geobey2014).

The Role of Indigenous Voluntary Organisations in Pakistan

It is estimated that there are between 100,000 and 150,000 voluntary organizations in Pakistan, but most are small, local service providers operating within specific niches, and lacking in strategic ambition (Shah, Reference Shah2014). They tend to be autonomous, independent of both government and the market, legally registered as charities, and frequently styled as trusts or foundations. However, unlike Western trusts and foundations, they rarely engage in fund management and grant making, but rather serve as front-line service delivery organizations (Maclean et al., Reference Maclean, Harvey, Yang and Mueller2021).

International NGOs are a major force in Pakistan, often working in partnership with the state to address social problems. However, these organisations are often unable to effectively mobilise communities in support of their objectives (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Hulme and Edwards2015; Bano, Reference Bano2019), primarily because the solution tends to be couched in ‘northern values’ (Bano, Reference Bano2008, p. 2298). This top-down approach means indigenous populations are systemically excluded, as objectives tend to cater for more remote elite groups (Banks & Hulme, Reference Banks and Hulme2014). Conversely, large indigenous voluntary organizations offer certain benefits, for example, local networks (anks & Hulme, Reference Banks and Hulme2014), legitimacy (Borchgrevink, Reference Borchgrevink2020), and the generation of trust in projects (Appe, Reference Appe2017; Suárez & Gugerty, Reference Suárez and Gugerty2016); all factors necessary for success in social initiatives. Therefore, these forms of social capital, which are, “the networks of community and the norms of trust and reciprocity that facilitate collective action” (Brown & Ferris, Reference Brown and Ferris2007, p. 86), tend to be critically important for the performance of social projects. Despite social capital being a key advantage of indigenous voluntary organisations, few have broken free from broader resource and capability constraints to make a large impact as national or even provincial service providers. Yet, it is encouraging that some have done so, emerging in recent years as leaders in socio-economic development in the education, health, and economic spheres, begging the question at the heart of this paper: what might be learned from the experiences of these success stories? There is little extant research on this topic. We know that Pakistan’s leading voluntary organizations secure about half their income from fees and charges for services that philanthropy is the next largest source of funds, and that government grants and foreign aid from public and private sources contribute smaller but valuable sums (Ghaus-Pasha et al, Reference Ghaus-Pasha, Haroon and Iqbal2002).

As strategically significant players, with popular, governmental and international support, large voluntary organizations have sought to fill the ‘institutional voids’ that occur when neither the state nor markets have the skill, will or resources needed to tackle deeply entrenched socio-economic problems (Mair & Marti, Reference Mair and Marti2009; Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Uhlander and Stride2015; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Khoury and Hitt2020). Institutional voids manifest when people have no access to basic institutions like hospitals and schools, and it is in filling these voids that large voluntary organizations contribute to socio-economic development. In health care in Pakistan, for example, where the public sector provides just 30% of services, just 27% of the population has full health care coverage and the remainder pay for private consultations and treatment or receive free or subsidised care from voluntary health care providers (Hassan et al., Reference Hassan, Mahmood and Bukhsh2017). Impoverished communities are especially badly served.

Social Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation

Social entrepreneurship and social innovation are fundamental to the growth and socio-economic impact of large indigenous voluntary organizations. The two constructs, as Maclean et al. (Reference Maclean, Harvey and Gordon2013) observe, are closely linked, the pressure to innovate being integral to social entrepreneurship. Thus, while social entrepreneurship is about channelling entrepreneurial activity to solve social problems resulting from market failures, social innovation is about implementing fresh ideas with ‘potential to improve either the quality or the quantity of life’ (Pol & Ville, Reference Pol and Ville2009: 881), suggesting that social innovations may by system changing in so much as they permanently seek to change the perceptions, behaviours and structures that previously gave rise to these challenges. Mair and Marti’s (Reference Mair and Marti2009) pioneering study of BRAC in Bangladesh is instructive. In this, the authors focus on a specific institutional void, the lack of microfinance for the ultra-poor, especially women, in rural areas. In filling the void, BRAC, as social entrepreneur, had to devise new products and processes in severely resource constrained circumstances. The authors point to the necessity of strategic bricolage, coming up with innovative tactics and making do with whatever resources were at hand to swell the client base and fill the institutional void. Philanthropy often plays a crucial role in development processes by helping social entrepreneurs overcome initial resource constraints and thenceforth by enabling the progressive upscaling of activities (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Maclean and Suddaby2019).

Scaling-up activities is a necessity if any social innovation is to impact significantly, and involves social entrepreneurs variously in offering additional services, replicating services across a larger geographic area, and finding new ways to serve more people (Westley et al., Reference Westley, Antadze, Riddell, Robinson and Geobey2014). From this perspective, social value creation is dependent on the creation of viable social ventures, voluntary organizations with an entrepreneurial orientation capable of surmounting manifold challenges to their establishment and growth. Perrini et al. (Reference Perrini, Vurro and Costanzo2010) depict the process of social value creation processually in terms of opportunity identification, opportunity exploitation and scaling-up and propose that successful growth depends on entrepreneurial awareness, impactful innovation, a superior business model, economic viability, resource mobilization, consistent organization, and trusted reputation. Jowett and Dyer (Reference Jowett and Dyer2012), while focusing on different pathways to replication, make the case that success in scaling-up operations is contingent on adaptability to local circumstances and organizational learning. A similar conclusion is reached by Westley et al. (Reference Westley, Antadze, Riddell, Robinson and Geobey2014) who point to the importance of initial conditions, founding visions and social networks in determining how social innovations are exploited and scaled-up. In what follows, we build on these ideas to demonstrate how philanthropy allied to social entrepreneurship and social innovation can help in bridging social divides in developing countries like Pakistan.

Methodology

In-depth case studies founded on oral histories and documentary evidence are particularly valuable as a means of developing, improving and challenging theory (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007; Yin, Reference Yin2009). Our research is focused upon the emergence and development of five large philanthropically supported indigenous voluntary organizations that serve as engines of socio-economic development in Pakistan. The case organizations were selected purposively as established leaders within their respective fields and willing to grant access to the research team. For each case we first gathered historical data relating to founding, founders, operations, and growth from publicly available sources such as books, annual reports, media interviews, and websites. We next conducted semi-structured interviews with five knowledgeable actors at each organization (25 in total) with roles such as Chairman, Chief Executive, Managing Director and Head of Operations. Our interview strategy was to obtain data from actors at all levels within the case study organisations. In each case, the interview schedule followed a similar pattern to be able adequately to triangulate the findings. The specific questions we asked were guided by key concepts covered in our literature review, for example, their perspectives on legitimacy, the institutional environment, and the role of the Islamic faith. Our broad purpose was to understand why and how the organizations came into being and what it took to become impactful agents for socio-economic development.

Case Studies

Brief details of each of the five case studies are provided in Table 1. First, the Fauji Foundation is one of the oldest charitable organizations in Pakistan with operations in all parts of the country. It was controlled by the military and since 1954, initially drawing on a fund legated by the former British administration and has accumulated an impressive portfolio of private-sector companies, the profits from which support its philanthropic endeavours. Fauji pays and benefits former armed service personnel and their families. Second, the Al-Shifa Eye Trust based in Rawalpindi, treats all major eye diseases through an expanding chain of modern hospitals, a specialist paediatric hospital, and eye camps servicing remote parts of the country. Third, the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital (SKMCH) is Pakistan’s first and foremost comprehensive cancer care research and treatment hospital group. It is based in Lahore and is expanding its chain of hospitals in other major cities. Both Al-Shifa and SKMCH offer free treatment to 75% of the disadvantaged patients. Fourth, the Akhuwat Foundation, also based in Lahore, is the world’s largest interest-free microfinance organization. Finally, the Engro Foundation is the philanthropic arm of the Engro Corporation, a multinational conglomerate based in Karachi with subsidiaries involved in production of fertilizers, foods, chemicals, energy, and petrochemicals. Its focus is on economic development, and the training of small holder farmers in modern agricultural methods (Khan, Reference Khan2021).

Table 1 Case organizations.

Organization |

Year founded |

Philanthropic field(s) |

Main source(s) of income |

|---|---|---|---|

Fauji Foundation |

1954 |

Social welfare (pensions and benefits for ex-military personnel); Education (schools and colleges); Health (hospitals and treatment centres); Higher education |

Dividends from numerous businesses owned and controlled by the Foundation |

Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital |

1985 |

Health (eye care) |

Philanthropic fundraising; Patient fees; Project support grants |

Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital (SKMCH) |

1991 |

Health (cancer care) |

Philanthropic fundraising; Patient fees; Project support grants |

Akhuwat Foundation |

2001 |

Enterprise, skills, and economic development (microfinance) |

Philanthropic fundraising; Trading income; Project support grants |

Engro Foundation |

2007 |

Education; Health; Enterprise, skills, and economic development; Environment |

Allocations from profits of Engro Corporation; Project support grants |

Analysis and Interpretation

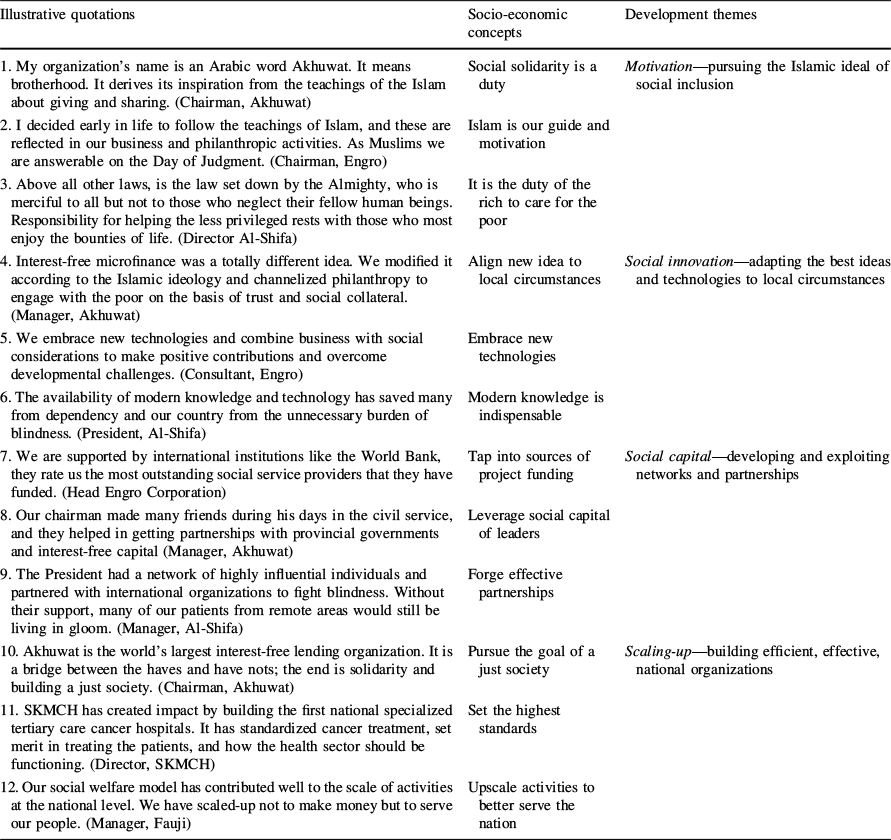

We coded our interviews thematically in NVivo. In a first pass, we open coded the corpus of 150,000 words captured in transcripts of our 25 interviews (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2015), yielding numerous text segments classified by 38 first-order terms, the broad topics discussed by interviewees. Coding was carried out by two researchers and differences reconciled. Next, following the Gioia method (Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012), the first-order terms were distilled further to identify 12 s-order socio-economic concepts, which were then aggregated into four aggregate development themes, as illustrated in Table 2 below. The meaning and significance of each of four development themes emerging from the data were then interpreted with reference to existing literature and documentary sources. This involved placing the evidence within the broader socio-economic and policy context prevailing in Pakistan, deriving wider meaning and points of theoretical interest from close examination of interview data.

Table 2 Drivers of growth of large third sector organizations in Pakistan

Illustrative quotations |

Socio-economic concepts |

Development themes |

|---|---|---|

1. My organization’s name is an Arabic word Akhuwat. It means brotherhood. It derives its inspiration from the teachings of the Islam about giving and sharing. (Chairman, Akhuwat) |

Social solidarity is a duty |

Motivation—pursuing the Islamic ideal of social inclusion |

2. I decided early in life to follow the teachings of Islam, and these are reflected in our business and philanthropic activities. As Muslims we are answerable on the Day of Judgment. (Chairman, Engro) |

Islam is our guide and motivation |

|

3. Above all other laws, is the law set down by the Almighty, who is merciful to all but not to those who neglect their fellow human beings. Responsibility for helping the less privileged rests with those who most enjoy the bounties of life. (Director Al-Shifa) |

It is the duty of the rich to care for the poor |

|

4. Interest-free microfinance was a totally different idea. We modified it according to the Islamic ideology and channelized philanthropy to engage with the poor on the basis of trust and social collateral. (Manager, Akhuwat) |

Align new idea to local circumstances |

Social innovation—adapting the best ideas and technologies to local circumstances |

5. We embrace new technologies and combine business with social considerations to make positive contributions and overcome developmental challenges. (Consultant, Engro) |

Embrace new technologies |

|

6. The availability of modern knowledge and technology has saved many from dependency and our country from the unnecessary burden of blindness. (President, Al-Shifa) |

Modern knowledge is indispensable |

|

7. We are supported by international institutions like the World Bank, they rate us the most outstanding social service providers that they have funded. (Head Engro Corporation) |

Tap into sources of project funding |

Social capital—developing and exploiting networks and partnerships |

8. Our chairman made many friends during his days in the civil service, and they helped in getting partnerships with provincial governments and interest-free capital (Manager, Akhuwat) |

Leverage social capital of leaders |

|

9. The President had a network of highly influential individuals and partnered with international organizations to fight blindness. Without their support, many of our patients from remote areas would still be living in gloom. (Manager, Al-Shifa) |

Forge effective partnerships |

|

10. Akhuwat is the world’s largest interest-free lending organization. It is a bridge between the haves and have nots; the end is solidarity and building a just society. (Chairman, Akhuwat) |

Pursue the goal of a just society |

Scaling-up—building efficient, effective, national organizations |

11. SKMCH has created impact by building the first national specialized tertiary care cancer hospitals. It has standardized cancer treatment, set merit in treating the patients, and how the health sector should be functioning. (Director, SKMCH) |

Set the highest standards |

|

12. Our social welfare model has contributed well to the scale of activities at the national level. We have scaled-up not to make money but to serve our people. (Manager, Fauji) |

Upscale activities to better serve the nation |

Findings

In seeking to learn from the experiences of Fauji, Al-Shifa, SKMCH, Akhuwat and Engro as philanthropically enabled agents of socio-economic development, we next detail our findings on each of the four aggregate themes emerging from analysis of our interview data. First, quotations one to three in Table 2 emphasize the importance of indigenous voluntary organizations in Pakistan of acting in accordance with Islamic values to maintain social solidarity, relatively well-off people having a duty to support less privileged members of society. Second, quotations four to six confirm that Islamic values are not seen as incompatible with innovation and social change. Rather, the drive is to harness modern ideas and technologies, suitably adapted to local circumstances, to bridge the divide between rich and poor. Third, quotations seven to nine indicate the importance of connectivity and social capital of organizational leaders to delivering on mission. Partnering on projects with government, international agencies, and philanthropists to increase impact is a high strategic priority in all cases. Fourth, quotations ten to twelve, strongly suggest that high ethical standards and the explicit pursuit of a just society are fundamental to the acquisition of organizational legitimacy and the scaling-up of operations nationally.

Motivation: Pursuing the Islamic Ideal of Social Inclusion

The senior officials we interviewed were acutely aware of the contemporary realities of socio-economic backwardness and assumed strategic responsibility to champion solutions. To achieve their objectives, each organization developed its own distinctive model of socio-economic change focused on long-term needs and individual capabilities consistent with development theory (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2003; Sen, Reference Sen2005). Motivated by Islamic values of social inclusion, the Chairman of the Engro Foundation saw a social purpose beyond profit making, stating that “the attributes of my Holy prophet (PBUH)… are reflected in our business and philanthropic activities” (Interview, 2018). The foundation expresses these values by providing opportunities in low-income rural communities to develop the know-how and business skills needed to raise incomes. In this way, Engro promotes marketization and integrates commercial strategies to “align business development goals with social considerations to create shared value and positive economic impact” (Interview, Chairman, 2018). A similar motivation animates Akhuwat whose core purpose is to support self-employment through the provision of interest-free business loans. The words of its Chairman are instructive:

We need to change the socio- cultural and political norms that govern power nexus at the national, regional and global levels (Interview, Amal Academy, 2018).

Akhuwat founder, Dr Amjad, perceived that the small loans business sector had been hijacked by commercial banks charging high rates of interest to poor customers. Consistent with the tenets of Islam, he established Akhuwat as a no interest small loans provider. His vision proved inspirational, enabling Akhuwat to raise 75% of its permanent capital base from donations and contributions (Akhuwat Foundation, 2022). Philanthropy inspired by Islamic values, in effect, funded the growth of the organization while also paying for a large proportion of administrative costs—hence its ability to offer interest-free loans.

The Fauji Foundation’s motto “earn to serve” is emblematic of the role it plays in Pakistan’s socio-economic development. Fauji is controlled by the military and the profits from its business empire primarily support military families (Siddiqa, Reference Siddiqa2017). Fauji’s leadership takes pride in promoting markets, competition, and industrial efficiency, but “we do so to meet the growing welfare needs of our beneficiaries and to support the government in addressing the challenges of poverty, inequality and sustained socio-economic development” (Interview, General Manager, 2018). Al-Shifa and SKMCH, as medical charities, have more conventional funding models—charging wealthier patients for treatment while relying on philanthropic income to provide services free for poorer patients—but they too are motivated by the goal of an inclusive Islamic society. Al-Shifa gives “high priority to serving less advantaged patients in distant under privileged areas where many with treatable blindness live in isolation” (Interview, Resource Manager, 2018). Imran Khan, founder of SKMCH, following the loss of his mother to cancer, “decided to build a hospital that provides treatment completely free of charge” after observing that hitherto the rich “went abroad for treatment” but “the common man … had no place to go” (Interview with Imran Khan, Pakistan Television, 2020).

Social Innovation: Adapting the Best Ideas and Technologies to Local Circumstances

Our research strongly suggests that social innovation—the implementation of fresh ideas to solve seemingly intractable social problems—has been fundamental to the success of our case study organizations in overcoming resource and knowledge constraints to socio-economic development. The key to the success of Akhuwat, for example, is its famously low-cost, no-frills operating model, which enables the organization to support the less privileged in a manner consistent with the Islamic principle of interest-free loans. As its Finance Manager (Interview, 2018) explained: “the creativity which we brought in was that we were forced to develop a program, or design a program, which didn’t contradict the basic ideology, faith, and traditions of the society.” This could only be accomplished through “simplicity to minimize our operational cost … there are no vehicles, no overheads, our board members and likeminded civil society members work for us voluntarily” (Interview, Head of Training, 2018). Akhuwat’s model has had a transformational effect on the field of microfinance by changing institutional norms, expectations, and standards, with “conclusions that go far beyond microfinance” (Harper, Reference Harper and Rasheed2011: 26). In much the same way Engro has demonstrated innovative ways to deliver change by adapting farming techniques to solve specific local problems. Its rural entrepreneurship programmes focuses on increasing output and productivity in the rice and milk sectors by training farmers in superior methods. The farmers can then sell surplus production of rice and milk to Engro as accredited suppliers because of the quality assurance techniques they adopt (Khan, Reference Khan2021).

The challenges facing health care innovators, Al-Shifa and SKMCH, were at the outset especially daunting, as encapsulated by the first Chief Executive of SKMCH:

To develop a master plan for a tertiary care, state-of-the-art, cancer institution in a developing country was a daunting task. No reliable statistics on cancer incidence in Pakistan were available in 1990, concepts of modern hospital management did not exist in the country, nursing training had not kept pace with modern trends, and there was a dire shortage of trained ancillary health staff (Burki, Reference Burki2019).

At both Al-Shifa and SKMCH, organizational development proceeded by adopting best practice international standards, protocols and methods of treatment, essentially emulating practices in the US and UK but adapting these to local circumstances. Two major organizational innovations followed. First, recognizing the near complete lack of provision for patients in remote parts of the country, the practice developed of setting up medical camps on a temporary basis staffed by travelling doctors and nurses. The hub-and-spoke model has enabled Al-Shifa “personnel to reach the village level patients at their doorstep through our eye camps” and when at one camp “we reached 200 patients per day we built the first regional children eye care hospital” (Interview, Executive Director, 2018). Second, to meet the cost of treating 75% of patients free of charge to the highest international standards, Al-Shifa and SKMCH have had to create exemplary fundraising organizations to solicit donations from individuals and charitable foundations at home and abroad, especially with respect to the payment of Zakat, which Imran Khan credits SKMCH’s success in confounding “experts and critics [who in 1989] were of the opinion that providing free treatment in a cancer hospital was not feasible. [It is] through the Islamic concept of Zakat, [we’ve shown how] indigent cancer patients can be supported” (Khan, Reference Khan2022).

Social Capital: Developing and Exploiting Networks and Partnerships

Our findings suggest that possession and accumulation of social capital is crucial to launching and building sustainable third sector organizations in developing countries. Each of the five case organizations had well-connected founders whom other members of the Pakistani elite lent support. et al.-Shifa, for example, General Jahan Dad Khan “had links with presidents, top government officials and would go to the corridors of power for assistance” (Interview, Executive Director, 2018), while at Akhuwat Dr Amjad felt able to go directly to “the Chief Minister Punjab … [and say] I can go for a bigger scale if you give us the state resource and my team will bring passion” (Interview, Amal Academy, 2018). At Fauji the top management team is “very well connected” and “has access to resources” (Interview, Investment Manager, 2018), and at SKMCH founder Imran Khan leads on fundraising by “exploiting his social status [in approaching] his network of influential relatives and friends and the masses for donations” (Interview, Marketing Manager, 2018).

Social capital is the glue that binds enduring networks and partnerships. Having abundant social capital provides access to scarce resource, increasing activity levels and the scale, scope, and effectiveness of operations. The Marketing Manager of SKMCH (Interview, 2018) reported having “individual donors both within and outside the country, corporate donors, and grant making organizations like the UNHCR who find us credible.” According to its Director of Research (Interview, 2018), funding from these sources enabled SKMCH quickly to adopt new techniques and procedures by “hiring well remunerated foreign qualified specialist physicians” who might train up locally educated physicians to increase the numbers of patients treated. The Executive Director of the Fauji Foundation (Interview, 2018) observed with respect to NGOs that “they partner with us because we are an institution that people trust, and we have gained good reputation over the years.” Al-Shifa’s Resource Generation Manger (Interview, 2018) claimed that “without support from international partners many of our patients from remote areas would still have been living in gloom”, adding that “locally we partner with corporates and oil companies for eye camps.”

National and provincial government agencies are important partners, lending credibility to projects (Appe, Reference Appe2017; Borchgrevink, Reference Borchgrevink2020) and bringing significant funding (Suárez & Gugerty, Reference Suárez and Gugerty2016). Akhuwat, for example, manages the government’s microfinance loan fund and its youth self-employment fund of $500 million, co-funded with the Gates Foundation (PCP, 2019). Reputation rather than legal status is the critical variable in attracting funding partners. Engro, as a corporate foundation, is a well networked organization with numerous “implementation partners, financial partners such as US Aid, the European Union, Australian Aid, various international development banks and, of course, the government, and knowledge partners who design, monitor and evaluate programs” (Head of Engro Foundation).

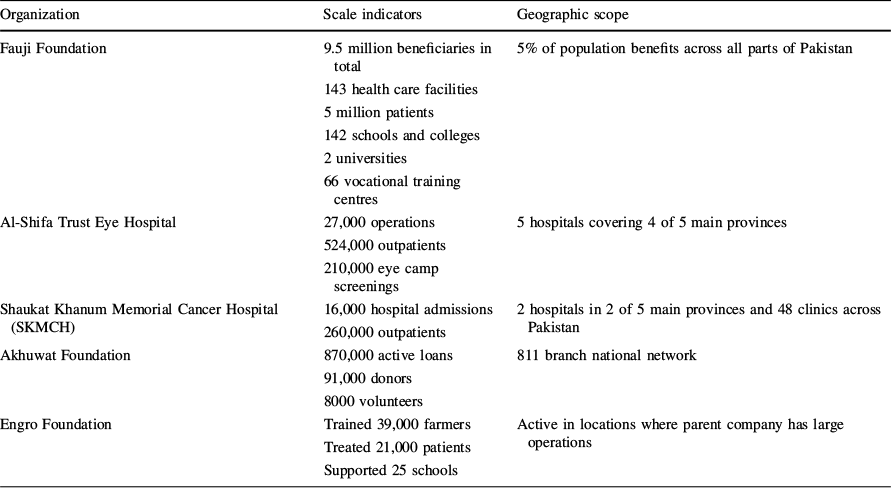

Scaling-Up: Building Efficient, Effective, National Organizations

Gerschenkron (Reference Gerschenkron1962), in his comparative historical study of socio-economic development, observed that less developed countries suffer overwhelmingly from shortages of capital, knowledge, and entrepreneurial talent. He demonstrated, theoretically and empirically, that typically in such circumstances development is driven by a relatively small number of organizations that accumulate scarce resources, pursue growth, and outpace the general rate of change in society. In effect, these leading-edge organizations become the main drivers of development until the resources and entrepreneurial talent needed to sustain transformational change become more widely available. The emergence and progressive scaling-up of our case study organizations is best seen in this light. Table 3 provides indicative details of their present scale and scope.

Table 3 Indicators of scale and scope of organizational activities (circa 2020).

Organization |

Scale indicators |

Geographic scope |

|---|---|---|

Fauji Foundation |

9.5 million beneficiaries in total 143 health care facilities 5 million patients 142 schools and colleges 2 universities 66 vocational training centres |

5% of population benefits across all parts of Pakistan |

Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital |

27,000 operations 524,000 outpatients 210,000 eye camp screenings |

5 hospitals covering 4 of 5 main provinces |

Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital (SKMCH) |

16,000 hospital admissions 260,000 outpatients |

2 hospitals in 2 of 5 main provinces and 48 clinics across Pakistan |

Akhuwat Foundation |

870,000 active loans 91,000 donors 8000 volunteers |

811 branch national network |

Engro Foundation |

Trained 39,000 farmers Treated 21,000 patients Supported 25 schools |

Active in locations where parent company has large operations |

Each of these large voluntary organizations is a pro-socially directed locus of resources and capabilities created by members of the Pakistani elite and sanctioned by a supportive government. Fauji is a rare example of a philanthropic enterprise that since 1954 has operated in commercial markets to generate profits in support of a “social welfare model that has contributed well to the growth and scale of activities undertaken at the national level” (Interview, General Manager, 2018). It is the largest social welfare provider outside government, and one of the largest business conglomerates in Pakistan. Al-Shifa “has grown to be the leading eye-health care provider in Pakistan delivering quality treatment and blindness prevention services to the poorest of the poor” with five hospitals, a paediatric hospital, three clinics, a professional training institute, a research centre, and drug manufacturing facility (Interview, General Manager, 2018). SKMCH is “a rare institution that has a financial deficit, yet continues to expand, from one hospital in Lahore to two major hospitals and a third opening in Karachi in 2023” (Interview, Marketing Manager, 2018). Like Al-Shifa, it has become a major provider of clinical training and sponsor of research. Akhuwat has experienced phenomenal growth based on a simple low-cost model that supports a compelling value proposition, creating “social impact and change nationally by giving access to finance at zero interest” (Interview, Volunteer, 2018). Finally, the Engro Foundation champions transformational change in rural communities by growing the incomes of farmers: “We believe in impact and scale enabled by philanthropic contributions and access to markets; that’s why our value chain projects, raising productivity, and increasing farmer incomes are core to our strategy” (Interview, Head of Foundation, 2018).

Discussion and Conclusion

Our research asks how and why large indigenous voluntary organizations are created and how they are able to overcome challenges, gain traction, and make a big difference to the lives of ordinary people? In answering this question, we begin by reiterating that all the case study organizations researched were founded by social entrepreneurs motivated by a desire to resolve what appeared to them to be a glaring social problem that if left unaddressed would cause unnecessary suffering on a grand scale among the poorest sections of society. In seeking to bridge social divides they established organizations that have grown to fill significant institutional voids. Fauji caters for the welfare, health and educational needs of former military families, relieving the state of significant obligations. Al-Shifa and SKMCH provide state-of-the-art medical treatments free of charge in both urban and rural settings. Akhuwat and Engro, by making no interest loans and providing training in modern agricultural methods, create opportunities to grow family incomes. Each organization, in its own way, contributes to development by enhancing the capabilities of individuals to participate more effectively in economy and society (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2011; Sen, Reference Sen1999).

Four factors stand out in explaining how the case organizations have overcome severe resource constraints to grow and prosper. First, the motivations, values and ethical stances of the five organizations inspire widespread trust, confidence and legitimacy. This explains why philanthropic donors at home and abroad support them in such large numbers, and why NGOs, charitable foundations and government agencies partner with them and support their projects, including Engro, a corporate foundation whose interests are closely aligned with those of its for-profit parent. Second, each of the organizations has embraced social innovation as a leitmotiv, searching for new and better ways of doing things. Enthusiasm for experimentation first took Al-Shifa into remote rural areas and brought Akhuwat to a market leading position within the space of a few years. Third, it is conspicuous that all five organizations have become institutionally embedded, aligned with the interests of other powerful actors in the public and private sectors. Actively accumulating and expending their social capital has resulted in them having a high degree of legitimacy both at home and abroad, making it easier to implement complex strategies that require the support and approval of numerous agencies. Fourth, they have projected bright visions for the future in an often-troubled land. In fashioning strategies for growth, they have kept to the fore the ideal of an increasingly prosperous Pakistan in which citizens are healthy, well educated, infrastructurally supported, materially comfortable, and in regular employment. Each has offered something new and valuable, consistent with this vision, and governments, philanthropists and the public have responded positively, in supporting their plans.

It is important to highlight the importance of embeddedness in the emergence and growth of large indigenous voluntary sector organizations in countries like Pakistan. Indigenous organizations are critical to the processes of socio-economic development because they have a more secure grasp than international organizations of local issues and environments (McKeever et al., Reference McKeever, Jack and Anderson2014; O’Connor & Afonso, Reference O’Connor and Afonso2019). Our research emphasises the role of social capital in uniting the networks of private, voluntary, and governmental actors needed to deliver large projects. Indigenous voluntary organizations are effective precisely because they have affiliations to the communities, cultures and the purposes they serve (Moulaert, Reference Moulaert, MacCallum, Moulaert and Hillier2009). Hence “social innovations can help establish a specific identity with place… [and] can provide models to be replicated or adapted in other places and be scaled-up” (Baker & Eckerberg, Reference Baker, Eckerberg, Baker and Eckerberg2008: 331). Indigenous organizations have the advantage of being on hand to form partnerships with local actors, particularly in remote locales with little institutional and economic infrastructure or private-sector provision (Baker & Eckerberg, Reference Baker, Eckerberg, Baker and Eckerberg2008; Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw2005). Finally, we suggest that locally embedded models are most likely to thrive in Islamic nations like Pakistan where value congruence, customs and shared understandings are fundamental to legitimacy and philanthropic giving (Borchgrevink, Reference Borchgrevink2020; Suárez & Gugerty, Reference Suárez and Gugerty2016). We suggest our findings are emblematic of other philanthropic adaptions seen elsewhere in the world in so much as the practices of philanthropy reflects the cultures, ethics and values of the population. We content that legitimacy is critical in creating shared meaning that is essential for social projects (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Warren and Bensemann2019; Nicholls, Reference Nicholls2010). Congruent with Borchgrevink (Reference Borchgrevink2020), our study suggests that Islamic philanthropy is critical in embedding common values in philanthropic networks.

It is impossible to discuss social divides in Pakistan and not acknowledge how gendered these divides are. Pakistan has a highly patriarchal social structure that excludes women from participation in many spheres of social and economic activity. The lack of access to health and education systems means women are often treated as second-class citizens in Pakistan. As a result, the positive innovations that we present as successfully overcoming social divides are perhaps limited. Notwithstanding this, the conclusion we reach is hopeful. Our research identifies a modern type of organization—large indigenous voluntary organizations—with the potential needed to bring about change at scale in developing countries. Our study highlights the nature of philanthropy as geographically inscribed, underlining that where government spending is very limited, its effects may be materially amplified. The primary contribution we make to the literature therefore is to highlight the already impressive achievements of large voluntary organizations in bridging social divides and their potential to play an increasingly significant role in the socio-economic development of Pakistan.

Funding

The authors declare that this article was researched and written without the support of any funding body.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.