6.1 Introduction

In 2012, then-Prime Minister David Cameron expressed his frustration with the UK’s public sector, criticizing it for producing “reams of bureaucratic nonsense.”Footnote 1 This sentiment has been part of a long-standing conservative approach characterized by significant deregulation and public spending cuts, unparalleled in Europe (Dalingwater, Reference Dalingwater2015; Hernandez, Reference Hernandez2021). Echoes of Thatcherism’s disdain for perceived public sector inefficiency persisted through successive administrations (Dorey, Reference Dorey, Peele and Francis2016; Jackson, Reference Jackson2014). Even the New Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown continued to promote ideas of New Public Management and the trimming of public services (Bevir & O’Brien, Reference Bevir and O’Brien2001). Despite the Conservative Party’s significant electoral defeat in 2024, the impacts of austerity continue to resonate across all levels of public service in the UK, leaving the country ill-equipped to tackle new and upcoming challenges such as climate change and rising demand for social services.

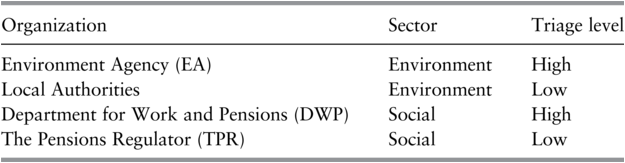

As a result of more than four decades of “assault on the welfare state” (Grimshaw, Reference Grimshaw and Vaughan-Whitehead2013: 581), the major implementers in the environmental and social policy area – the Environment Agency (EA) and the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) – find themselves in what could be termed “implementation hell.” Plagued by severe underfunding, staff shortages, and an overwhelming increase in responsibilities without adequate support from policymakers, these agencies struggle daily to manage their workload. As a result, both organizations have embedded policy triage deeply in their organizational routines, frequently having to resort to it with increasingly severe consequences. Yet, while the EA and the DWP find themselves in similar scenarios coined by unequivocally high levels of triage, they show variance with regard to two of our three mechanisms theorized earlier: While both organizations are presented with opportunities to mobilize resources externally only rarely, they encounter different dynamics when it comes to blame-shifting. The EA often is used by policy formulators as a public scapegoat, whereas the DWP presents a case of formulators trying to avoid responsibility and instead shifting accountability toward lower levels of the organization, largely trying to avoid the public eye while doing so. Secondly, the EA and the DWP also differ in their capacity to compensate for overload. While the former is still able to rally the troops in times of emergencies, the latter appears to have exhausted any such compensatory capacity.

In stark contrast to the dire situation at the DWP and EA, The Pensions Regulator (TPR) emerges as an administrative oasis, challenging the assumption that policy triage is a generalized phenomenon across all central-level organizations. TPR’s specialized role within the social sector shields it from the blame-shifting tactics often observed in other instances. Its focused mandate also enhances TPR’s ability to mobilize external resources effectively and manage its operations more autonomously, including control over specific revenue streams not directly tied to government funding. Furthermore, TPR maintains a robust reputation that not only aids in resource mobilization but also boosts its appeal as an employer, empowering it to attract and retain skilled personnel. This combination of factors enables the organization to handle potential overload situations with a proactive and committed workforce, setting it apart from the other two organizations at the central level.

Lastly, local authorities in England, while facing their own set of challenges, generally exhibit a better adaptation to the accumulation-induced pressures compared to their central counterparts and other local actors in our sample. This relative resilience can be attributed to the centralized nature of governance in the UK, which limits the scope for blame-shifting attempts from the formulating level. In addition, local authorities often profit from good relations with the formulating level while at the same time opening up additional streams of revenue by commercializing services, for example. Compared to the EA, local authorities also display higher levels of ownership and advocacy due to the closeness to the policies they implement. An analysis of our key three mechanisms thus reveals that local authorities can sustain relatively low levels of triage, even within the overarching detrimental framework of national policy.

The overall organizational setup regarding levels of triage is fairly similar in both the environmental and social sectors. In both cases, the central implementers – the EA and the DWP, respectively – perform significantly worse than the comparatively less impactful local authorities and TPR. This represents the first puzzling observation in the British context. The second puzzle emerges from the generally favorable conditions under which local authorities operate and their overall relatively low levels of triage. This is particularly striking when considering that, in other countries, local authorities often perform worse than their central counterparts. Given that the implementation landscape in both policy fields is marked by extremes, we opted for a sectoral comparison rather than a cross-sectoral or multilevel approach.

In the following sections, we investigate those stark contrasts in policy triage and explain the puzzling variation unique to Rule Britannia. We begin with an exploration of the organizational structures and the evolving task loads across different agencies, providing a foundational overview in Section 6.2. In Section 6.3, we analyze the prevalence of triage at the English environmental and social implementers. In Sections 6.4 and 6.5, respectively, we account for the marked variation in triage levels in both sectors. Concluding in Section 6.6, we reflect on the overall impacts of triage dynamics on policy implementation across the UK’s social and environmental landscapes.

6.2 Structural Overview: Environmental and Social Policy Implementation in the UK

The UK is often described as a “union state” between England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland (Rokkan & Urwin, Reference Rokkan and Urwin1983). The UK’s central government in Westminster formulates and implements policy for both England and the UK as a whole, while the other three countries possess varying degrees of autonomy in lawmaking, tax levying, and policy implementation (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell and Stolz2010). These unique devolution processes have led to limited but complex transfers of competence, constituting a “conferred powers model” that retains formally strong central control. Implementation of environmental policy, however, has been almost entirely devolved, with Westminster primarily responsible for England and maritime protection in Northern Ireland (Trench, Reference Trench and Trench2004). In the realm of social policy, Westminster oversees general policy formulation and implementation across Great Britain, with the exception of certain minor benefits and services devolved to Scotland. Northern Ireland, in principle, maintains its own social policy and service delivery system (Gray & Birrell, Reference Gray and Birrell2012).

The UK’s political environment has been highly dynamic in recent years compared to that of previous periods. The traditional two-party system, dominated by the Conservative and Labour parties, has faced significant challenges from smaller parties such as the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Liberal Democrats, as well as the emergence of new political forces like the right-wing populist Reform UK. After the 2024 election, the party system emerged as the most fragmented in British history with Reform UK, the Greens, and Plaid Cymru all seeing record results (Prosser, Reference Prosser2024). This political dynamism, combined with the complexities of devolution, has created a more fragmented implementation structure (Keating, Reference Keating2022a, Reference Keating2022b). In this chapter, we focus primarily on England for two reasons. First, doing so reduces analytical complexity, as it allows us to sidestep the varying levels of devolution and the distinct competencies on the formulating and implementing levels found in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Moreover, England represents the largest and most economically and demographically dominant part of the United Kingdom, making it particularly relevant for understanding broader implementation patterns and policy impacts compared to the other three countries.

The UK administrative system, particularly in England, has traditionally adhered to the Westminster model of governance, characterized by a strong central government, a relatively small civil service, and a significant degree of executive control (Heffernan, Reference Heffernan2005). In particular, the prime minister as “the focal point of modern cabinet” (Mackintosh, Reference Mackintosh1968: 428) yields significant authority over policy formulation and implementation as he or she also “oversees the operation of the civil service and government agencies”Footnote 2 (see also Diamond, Reference Diamond2023; Lowe & Pemberton, Reference Lowe and Pemberton2020). The civil service, though professional and merit-based, has experienced varying degrees of politicization, especially in light of recent political events such as Brexit, which have placed substantial strains on the administrative apparatus (Diamond, Reference Diamond2023). While some scholars anticipated a process of significant de-Europeanization, empirical evidence suggests a more nuanced reality. Rather than wholesale dismantling, many major policy tasks previously under European Union (EU) jurisdiction have been reabsorbed by national implementers (Greer & Grant, Reference Greer and Grant2023). A prominent illustration of this shift from a radical decoupling agenda to a more incremental approach is the removal of the “Sunset Clause” from the Retained EU Law Bill. Originally, this clause would have automatically revoked all EU-derived laws by the end of 2023, but it was ultimately abandoned in favor of a more measured strategy (Diamond & Richardson, Reference Diamond and Richardson2023). This followed the notion that Whitehall “lacked the knowledge and capacity to deal with the sheer amount of EU legislation, particularly given the tight timetable” (Dudley & Gamble, Reference Dudley and Gamble2023: 2574). Instead, research – and our empirical findings – provide evidence for a layering process where “new arrangements are bolted onto existing structures and rules” (Diamond, Reference Diamond2023: 2255), exacerbating dynamics of increasing complexity and accumulation.

The implementation structure in England is characterized by a dual governance model, where responsibilities are allocated between central and local administrations (Leyland, Reference Leyland, Sommermann, Krzywoń and Fraenkel-Haeberle2025). In total, there are 317 local authorities that fall in one of six categories: unitary authorities, metropolitan districts, London boroughs, combined authorities, and county and district councils (NAO, 2021: 16).

The latter two are part of a two-tier scheme where responsibilities are split between the larger county councils and the more local districts councils. The English model exhibits significant asymmetries: The central government retains authority over crucial sectors such as defense, foreign affairs, and immigration, while devolved administrations govern localized policies including health, education, and environmental regulation within their jurisdictions (Trench, Reference Trench2015). Since 2010, austerity measures have precipitated a notable centralization of power and resources at the national level. This centralization has systematically weakened the operational capacities of local governments and devolved bodies by consolidating funding and decision-making powers at the central level, thereby diminishing local autonomy and resources (Lowndes & Gardner, Reference Lowndes and Gardner2016). The shift has strained intergovernmental relationships and has imposed significant challenges on these administrations regarding their ability to effectively achieve policy objectives within the constraints of reduced fiscal space.

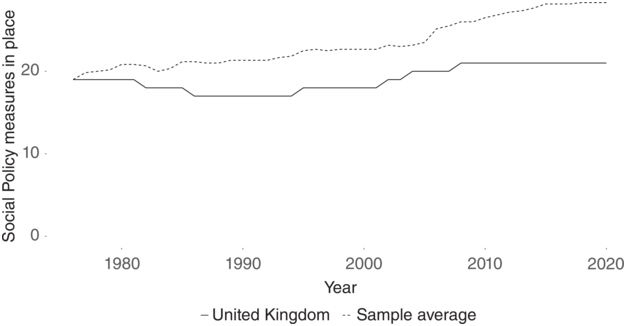

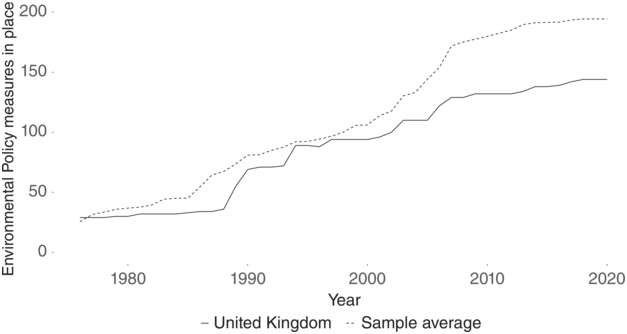

Compared to other countries in our study, the UK stands out due to its relatively restrained policy accumulation, particularly in the environmental sector. As illustrated in Figure 6.1, the UK has the smallest environmental portfolio among the countries in our sample. Until the early 2000s, the size of the UK’s policy stock was closely aligned with that of Denmark and Ireland. However, while Denmark and Ireland have since considerably expanded their environmental policy portfolios (see Chapters 4 and 7), the UK has followed a more measured trajectory of growth. After 2008, UK environmental policy growth has significantly slowed, with additions to the portfolio centrally being driven by the EU (Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher & Zink, Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2024). Besides delegation to the EU level, a key factor responsible for this change in growth dynamic was the Cameron administration’s approach to deregulation. Nevertheless, and despite its comparatively slower accumulation, the UK has still experienced a notable increase in environmental policy activity. Brexit, in particular, led to substantial workload increases as the regulatory scope of the EA expanded significantly. This expansion was driven by the transfer of implementation tasks previously managed at the European level, such as the administration of emission trading schemes, to national authorities. It is important to note that these increases are not reflected in Figure 6.1, as they do not constitute new policy additions under our accounting scheme but instead represent a shift in administrative responsibilities. At the same time, and concurrent with the slowdown in national policy growth, the resources available at both the central and local levels have been substantially diminished due to the Coalition government’s austerity measures. This has resulted in organizations having to manage expanding workloads with significantly fewer resources, forcing the EA in particular to rely on triage more and more frequently.

Figure 6.1 Environmental policy measures in the UK.

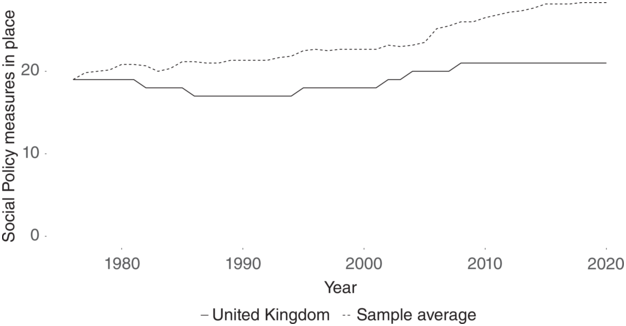

In the social policy domain, the UK also maintains a relatively modest portfolio in comparative perspective, ranking just above Denmark. Notably, even during and following the financial crisis – a period when most countries in our sample, including Denmark, introduced new measures to mitigate the impact of the crisis – the UK did not expand its social policy portfolio (see Figure 6.2). At first glance, it might seem that accumulation-induced overload should be minimal, if not nonexistent. After all, the growth of primary legislation has stagnated, as depicted in Figure 6.2. However, this perspective overlooks a notable increase in secondary legislation and regulatory activity, resulting in substantial workload increases, driven largely by continuous welfare state reforms. These reforms have led to a significant expansion of administrative tasks and operational activities that occur “below the surface” of formal policy adoptions. As a result, while the volume of visible primary legislation may appear stable, the underlying administrative burden has grown considerably, placing heightened pressure on implementing agencies. An example of such “clandestine” workload increases is the introduction of weekly meeting requirements for unemployed individuals. Although this change did not constitute an expansion of the social policy portfolio in a formal sense, it placed substantial burdens on caseworkers, significantly increasing their workload.

Figure 6.2 Social policy measures in the UK.

Moreover, the UK welfare system has been subject to near-constant reform since 1997, following the election of the New Labour government. While reforms under New Labour were significant, the pace of change accelerated markedly after 2010 under the Conservative-led coalition government. This period saw the introduction of a range of major welfare reforms (Beatty & Fothergill, Reference Beatty and Fothergill2018), the most comprehensive of which was the rollout of Universal Credit (UC), consolidating six existing benefits – including Jobseeker’s Allowance, Housing Benefit, and Income Support – into a single monthly payment (DWP, 2010). In that sense, it is “best understood as a repackaging of existing benefits that for the first time introduces a consistent withdrawal rate, with the rules governing eligibility carried over from the existing benefits it replaces” (Beatty & Fothergill, Reference Beatty and Fothergill2018: 952). Rather than introducing new policies, the objective was to simplify the welfare system, make it more efficient, and incentivize employment by reducing the disincentives traditionally associated with moving from welfare to work. While this consolidation aimed to streamline benefits administration, it also came with substantial challenges that have considerably increased the workload for the DWP. Thus, even with a stable policy portfolio, the depth and complexity of secondary legislation and reforms like UC have contributed to significant workload pressures within the DWP.

6.2.1 Competence and Burden Allocation in Environmental Policy

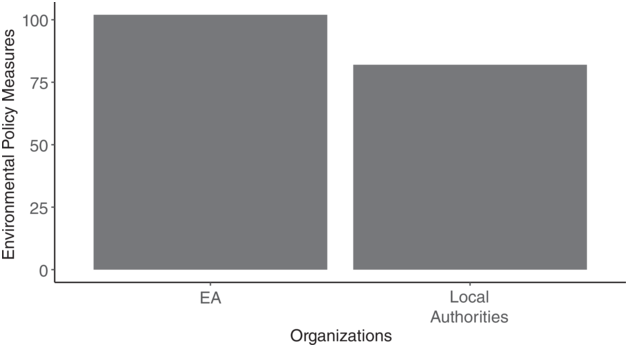

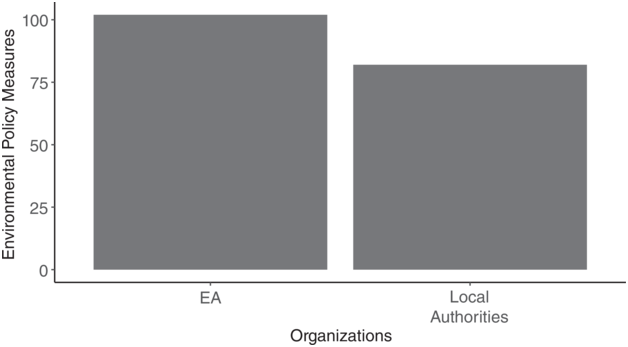

Moving on to the environmental implementation landscape, the large part of policy in the UK is implemented by the EA and the local authorities (see Figure 6.3). While other, smaller entities also are tasked with the implementation of some parts of environmental policy, they are either focusing on a single issue such as the Drinking Water Inspectorate (DWI) or their core mandate is not within the environmental sector such as the Driver and Vehicles Standard Agency (see Zink et al., Reference Zink, Knill and Steinebach2024: 12). Consequently, in our analysis, we focus on the two major implementers, the EA and the local authorities.

Figure 6.3 Environmental policy measures per organization.

The EA was established under the Environment Act of 1995 and became operational in 1996, initially overseeing environmental regulations across England and Wales. However, in 2013, responsibilities for Wales were transferred to Natural Resources Wales, leaving the EA solely in charge of England. Among the central environmental implementers examined in this study, the EA possesses the broadest mandate. Besides regulating major industries and waste, treating contaminated land, and ensuring water and air quality, the EA is also responsible for fisheries, conservation and ecology, and – centrally – flood management.

While the EA is set up as an independent agency or a nondepartmental public body (NDPB), potential limitations to the organization’s autonomy are embedded within the very legislation that established it. The Environment Act (1995) stipulates that “The Secretary of State shall from time to time give guidance to the Agency with respect to objectives which the Secretary of State considers it appropriate for the Agency to pursue in the discharge of its functions” (Environment Act, 1995: c1 s2). This provision effectively allows the government to influence the agency’s priorities and actions, potentially curbing its autonomy. In contrast, the Irish EPA, for example, was established as a truly independent regulator, free from such direct governmental oversight, which significantly enhances its ability to operate without external pressures (see Chapter 7). The institutional setup of the EA thus already provides more avenues for political interference and potential blame-shifting than is the case for comparable bodies in other countries.

The central aim of informing the organizational setup of the EA thus was not the creation of an independent regulator necessarily but instead to provide a “one stop shop” for environmental affairs. The idea was to significantly increase coherence and effectiveness of environmental policy in England while decreasing the overall number of governmental bodies at the same time. Despite widespread consensus on the need for creating a central environmental agency among parties and stakeholders such as environmental and industry interests groups, it stretched “only to the principle of establishing such an agency” (Carter & Lowe, Reference Carter, Lowe and Gray1995: 38). Even within government, no clear consensus on the mandate of the prospective organization emerged as a number of ministers feared a devaluation of their own portfolio. Ultimately, the EA was created by a merger of eighty-five organizations: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Pollution (HMIP), the National Rivers Authority (NRA), and eighty-three local Waste Regulation Authorities (WRAs). This merger was not only administratively demanding but also came with significant cultural and operational caveats. It unified bodies with distinct regulatory philosophies, operational styles, and environmental focus areas, each deeply entrenched in their unique historical and scientific paradigms:

The really challenging time was when the environment agency was formed, because we were trying to bring together three different cultures. There was a Pollution Inspectorate, there was the National Rivers Authority, paid more, more qualified. And then I was one of staff from 83 separate local authority Waste Regulation Bodies. We had to come together into a single body. In the months running up to that we had had to face a complete overhaul of our whole way of regulating. […] The whole way of doing stuff suddenly [increased by] an order of complexity, a 1000 times. […] We literally had – before the agency was formed – two weeks’ notice from government that this was coming in.

For much of its adolescence, the agency thus struggled with a lack of vision and direction as multiple interest groups within the agency competed for attention. The EA was criticized heavily by “regulated industries, environmental groups, anglers, local authorities, employees, the government, local communities, members of the public” (Bell & Gray, Reference Bell and Gray2002), ultimately triggering a review of the organization by the Commons Select Committee on Environment, Transport and Regional Affairs (SCETRA). The conclusion of the report was devastating, decrying a failure of leadership that prevented the organization from making “a significant contribution to the attainment of sustainable development in England and Wales” (SCETRA, 2000: 155).

In response to the SCETRA report and following subsequent leadership changes, the agency embarked on a mission to redefine itself as the “champion of the environment.” This new vision aimed to foster stronger coherence across various segments of the organization and among individual staff members. Recognizing the overwhelming demands of their roles, the agency cultivated a culture of collaboration, as described by one employee: “we realized that no single person could cope with the job on their own. Therefore, we needed to work together, find a way through, share good ideas, and give stuff up to manage our responsibilities more effectively” (UK03). Still, “it took a long time to standardize terms and conditions” within the agency (UK03). Yet, in the early 2000s, the EA finally appeared to have found its footing, which was also noted in a report by the House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee. The report positively recognized “the success of its performance as ‘modern regulator’ balancing national consistency with local flexibility” (Bigg, Reference Bigg and Foreman2018: 23).

The EA’s responsibilities are framed by several key legislative acts and regulations. Centrally, it is the main implementer for a broad range of tasks that includes regulating industrial pollution, water quality, waste management, and flood risk. The Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2016 give the EA authority to issue permits and enforce compliance on larger industrial operations and activities impacting air, water, and land. The Water Resources Act 1991 and the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 define the EA’s responsibilities in managing water resources, preventing flooding, and protecting water quality. Additionally, the Climate Change Act 2008 and the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) Regulations 2012 assign the EA a central role in regulating emissions and overseeing the implementation of carbon reduction strategies. The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017 further tasks the EA with protecting biodiversity and ensuring that development projects comply with nature conservation standards. These statutory responsibilities are supported by the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA), which provides policy direction, and ensure that the EA implements and enforces national and EU-derived environmental legislation effectively across England (Environment Agency, 2024).

Unlike the Irish EPA, which has a similar scope regarding water, air, and waste management, the EA’s responsibilities thus also encompass conservation and flood defense. This dual responsibility, particularly the need to manage flood defenses alongside general environmental regulation, often requires the agency to balance conflicting priorities. The challenge of resource allocation is particularly significant, as funding and staff are often stretched between immediate flood defense needs and long-term environmental goals. Although there have been discussions about divesting flood management responsibilities to a separate organization to alleviate this burden, no concrete action has been taken so far.

Aside from the EA, the 317 local authorities engage in environmental policy implementation (see Figure 6.3). The English Local Government Association (LGA) estimates that 7,170 staffers are employed in environmental roles in local councils, on average approximately 24 per organization (LGA, 2024a). The responsibilities of those bodies are governed by various legislative frameworks and guidelines, often in a shared mandate with the EA. Key among these is the Environmental Protection Act 1990, which outlines duties in waste management and pollution control, and the Air Quality Regulations 2000 and Air Quality Standards Regulations 2010, which mandate air quality monitoring and the creation of Air Quality Action Plans. The Flood and Water Management Act 2010 assigns local authorities a role in managing flood risks, while the Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2016 place responsibility for regulating small-scale industrial emissions on local councils. Additionally, the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) guides local authorities in incorporating environmental considerations into land-use and planning decisions. Local councils also have obligations under the Local Government Act 2000 to promote sustainability and well-being, and under the Climate Change Act 2008 to contribute to national carbon reduction goals through local climate action plans and energy efficiency initiatives. These frameworks are further supported by guidance from DEFRA, which provides overarching policy direction on environmental health, waste, and air quality management. Compared to the EA, however, the issues covered by local authorities can be considered to be of low risk and limited impact.

6.2.2 Competence and Burden Allocation in Social Policy

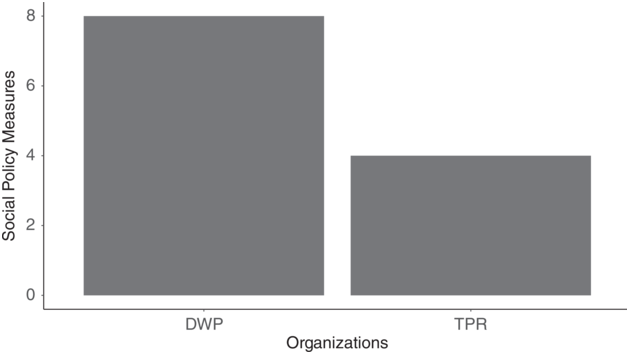

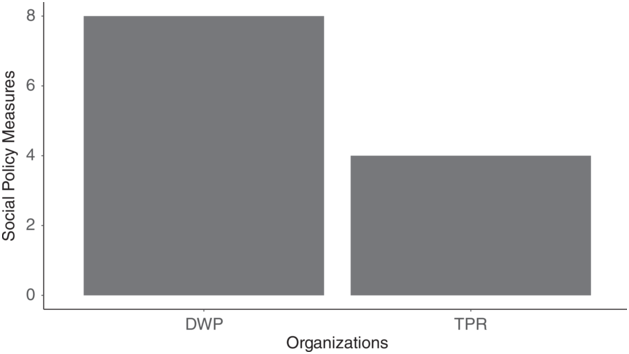

Turning to social policy, the DWP is the central implementer in the UK (see Figure 6.4). It is the largest public service department and has the largest number of core staff, of about 82,000. It is responsible for the majority of UK’s social policy portfolio. The department has two delivery services, the Jobcentre Plus and the Child Maintenance Services. While the latter focuses on statutory child support schemes, the former is responsible for UC, Jobseeker’s Allowance, and Employment and Support Allowance. In addition, the Department also oversees a number of nondepartmental bodies such as TPR and the Health and Safety Executive.

Figure 6.4 Social policy measures per organization.

The DWP was created in 2001, merging the Department of Social Security that had existed in one form or the other for almost a generation (Carmel & Papadopoulos, Reference Carmel, Papadopoulos and Millar2003: 1) with the Employment Service and the policy units of the Department for Education and Employment. The consolidation of services was characterized not only by administrative changes but has been described as an indicator of a broader reorganization of social policy in the UK (Carmel & Papadopoulos, Reference Carmel, Papadopoulos and Millar2003). The reorganization was a result of the changing objectives of social welfare under New Labour: moving social policy from a protection mandate toward one of support. The aim was to enable the state to “steer” claimants’ behavior toward a situation where they can adapt to demands of the market economy (Grover & Stewart, Reference Grover and Stewart1999). A further consolidation of the welfare services took place in 2008 when two separate executive agencies, the Pension Service and the Disability and Carers Service, were merged and later dissolved and its functions subsequently brought into the DWP entirely in 2011. Essentially, this made the Department the overarching authority with regard to social policy.

Additional regulatory functions regarding pension policy are carried out by TPR – which, however, is also directly answerable to the DWP. Similar to the Irish Pensions Authority, for example (see Chapter 7), TPR in the UK plays a crucial role in overseeing workplace pensions, ensuring compliance with pension legislation, and maintaining the financial stability of pension schemes. It monitors employers to ensure they provide proper pension access, enforces standards through fines and sanctions if necessary, and offers guidance to help manage and comply with legal duties. TPR also manages risks by assessing and acting to mitigate potential financial failures that could impact pension schemes. Additionally, it promotes administrative standards and engages with stakeholders, including other regulatory bodies and industry groups, to continually enhance pension security and effectiveness. Overall, TPR benefits from its very narrow role of regulating pensions schemes, rendering the allocation of additional tasks outside this scope nigh impossible.

6.3 On Desolation Row: Policy Triage in the English Environmental and Social Sector

In this section, we delve deeper into policy triage in England’s environmental and social sectors. We provide a detailed account of the extent to which key implementers – EA and local authorities in the environmental realm, as well as the DWP and TPR in the social arena – are compelled to engage in policy triage. We begin by assessing the levels of triage at the EA and the environmental implementers operating at the local level. Unlike the pattern observed in other countries within our sample, England presents a puzzling scenario: Local implementers fare significantly better than the central agency. This deviation warrants further attention, particularly given that the EA, despite a rocky start, managed to operate effectively for a decade following the turn of the millennium. However, the current situation is marked by frequent and severe instances of triage, suggesting that implementation capacity and workload have become misaligned. Turning to the social sector, an additional puzzle emerges from the triage variation observed between the DWP and the TPR. Despite both agencies operating at the same administrative level, their experiences with triage differ starkly. While the DWP appears to be “riding the highway to implementation hell” at full speed, frequently resorting to severe instances of triage, the TPR seems to have taken the “stairway to heaven,” exhibiting little to no signs of triage.

6.3.1 The Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Rampant Triage at the EA

There is a compelling reason why the EA was highlighted at the outset of this book (see Chapter 1). Described as a “demoralised and paranoid organization that had been severely undermined by austerity” (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2024), the state of the EA is undeniably dire. It exemplifies an organization compelled to frequent policy triage, facing profound operational challenges and severe consequences as a result. Confronted with an ever-increasing task portfolio on the one hand but decreasing resources on the other, both in terms of funding and staffing, the agency is forced to engage in policy triage extensively to manage its overwhelming workload (Zink et al., Reference Zink, Knill and Steinebach2024):

We definitely haven’t got enough money to do the job. In some cases, we might make a decision to say even though there’s a legal risk and the reputational risk and an environmental risk, we’re actually not going to do it until we have the resources to do it.

In addition to the growing gap between the increasing implementation burdens and decreasing resources, the EA’s situation is further complicated by instances of what is described as “policy layering” in the literature (Daugbjerg & Swinbank, Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2016):

We’ve got lots of layers of additional policy. You kind of have one policy and then you choose another one which overlays on top of that, and then another which kind of overlays on top of that. If you look at individual layers at the time, it makes perfect sense why you want to do it. They don’t look particularly significant in terms of additional resource at the time. But then over time, we seem to have lots of these new initiatives, new policies. They build up and all of a sudden you reach a bit of a tipping point where you have to make some difficult decisions. It makes it quite difficult to unpick. So you can’t unravel one bit without unravelling something else.

This situation has necessitated significant trade-off decisions, encapsulating what one staff member has described as “a kind of a constant form of triage” (UK03). As we theorized earlier (see Chapter 2), these decisions have indeed led to the development of informal routines and processes aimed at managing daily operations under constrained circumstances. A notable coping strategy has been the “incident triage project,” an informal initiative that prioritizes high-impact environmental incidents, to alleviate the workload of inspectors by neglecting lower impact issues (Salvidge, Reference Salvidge2022). This selective approach underscores the organization’s struggle to meet broader obligations, effectively reducing its operations to a bare minimum, as one staff member lamented:

We probably will just do really what we’re legally required to do. We won’t help out by providing ‘oh here’s a little bit of extra context or have you thought about this or what about that’. So providing the most basic product or response that we can to requests and just doing that within any statutory deadlines and some of those have slipped. When we face particular peaks around permitting, they [the permitting unit] take longer. There’s a greater backlog in terms of how long they’re taking to determine. Some of the advice that we give to local authorities on planning decisions definitely increased in the amount of time it takes to provide that response. In some cases we’re not providing a response anymore on particular issues that we’ve done in the past.

The EA’s policy triage affects more than just consultation and permit issuance; it profoundly impacts one of the organization’s core functions – monitoring environmental compliance. The ability to conduct essential inspections has been notably diminished, leading to a drastic reduction in the agency’s oversight capabilities. Previously annual assessments of water body health are now scheduled only once every six years, significantly delaying the detection and resolution of potential environmental issues (Salvidge & Hosea, Reference Salvidge and Hosea2023a). Between 2018 and 2023, the number of inspections for entities licensed to abstract water dropped from 4,539 to a mere 2,303, reflecting a steep decline in regulatory oversight (Salvidge & Hosea, Reference Salvidge and Hosea2023b). Moreover, a Freedom of Information request in 2020 revealed a startling statistic: The average farm in England would only be inspected once every 263 years, underscoring the severity of the reduction in monitoring activities and highlighting a near-complete erosion of the agency’s preventative and corrective capacities in this area (McGlone, Reference McGlone2024).

The substantial decline in regulatory oversight at the EA has drastically limited access to critical environmental data as well, leaving both the agency and the UK government significantly uninformed. This reduction in monitoring capabilities thus not only severely compromised the agency’s ability to enforce compliance and manage environmental resources effectively but also rendered it virtually blind to the scale of environmental pollution. Consequently, the EA’s capacity to respond promptly to environmental emergencies has also been notably weakened. With routine inspections drastically reduced, the EA frequently remains unaware of emerging issues, critically impairing its crisis management capabilities. Reports indicate that the agency’s response is so constrained that staff members admit inspections only occur in the presence of immediate, visible environmental damage or, in the words of an inspector, “unless there were dead fish floating everywhere” (Salvidge, Reference Salvidge2022). A former staff member even claimed that the agency overlooks the worsening condition of rivers on purpose: “The attitude from the higher-ups was really a sense of, ‘If we did a better job at finding pollution, there would be more of an expectation that we would then have to do something about it’” (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2024).

This scenario highlights a severe erosion of both preventive and reactive environmental protection measures at the EA and is seen as one of the central long-term challenges the organization is confronted with: “the biggest risk at the minute is that you’re not able to project five, ten years ahead. You can’t spot trends until they become issues, and you end up not having the right strategies in place. You’re just fighting the consequences” (UK04). This lack of forward planning is particularly critical in the context of climate change, where the agency’s ability to move proactively has not only stalled but regressed. “Not only are we not prepared,” an employee lamented, “but progress has slipped back in the last five years. It’s pretty distressing when that happens on your watch” (UK03).

While the reduction in inspections and diminished response capabilities is alarming, staff testimonials reveal an even grimmer reality within the EA. An employee described how drastic budget and staff cuts have rendered the agency ineffective as a regulatory body, stating that “resources have been cut back to such an extent that we cannot do our jobs, and the regulator is no longer a deterrent to polluters” (Salvidge, Reference Salvidge2022). Other comments reflect a widespread sentiment of despair within the organization, pointing to a significant decline in both the overall capacity and effectiveness of the agency in fulfilling its environmental protection mandate:

You have to run just to stand still. It is harder to sustain the progress that we’ve made, let alone make further progress […] Resources have eroded over time. So we have had to reduce the amount of the enforcement work that we do and the long-term consequence of that is that there’s more illegal activity that we aren’t able to address.

These accounts from EA staff vividly illustrate the severe challenges the organization faces in maintaining its regulatory functions amid dwindling resources. The situation has been exacerbated by the addition of new responsibilities to the organization’s portfolio, despite the decline of available resources. Particularly impactful was Brexit, which markedly increased the burden on the EA. As the UK transitioned away from the EU, a comprehensive recalibration of environmental oversight became necessary, as many tasks previously managed under EU jurisdiction had to be incorporated into national frameworks. Consequently, the EA was charged with new responsibilities, including the monitoring of emissions within the UK, a task previously overseen by regulatory bodies on the EU level:

We used to be part of the EU emissions trading system. We’ve had to create the UK emissions scheme and there are several of those. And then the environment act, which is also really a consequence of EU exit, introduced various new duties, local nature recovery strategies, biodiversity net gain, waste reforms.

This added burden has placed further strain on an already overstretched agency, compounding the difficulties in enforcing environmental regulations and managing the nation’s natural resources effectively. The consequences of these implementation failures are abysmal, leaving the UK with one of the lowest amounts of biodiversity in Europe (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Mordue, al Fulaji, Boersch-Supan, Boswell, Boyd, Bradfer-Lawrence, de Ornellas, de Palma, de Zylva, Dennis, Foster, Gilbert, Halliwell, Hawkins, Haysom, Holland, Hughes, Jackson and Gregory2023; Davis, Reference Davis2020). Furthermore, the country’s progress in meeting its own environmental targets is dismal. According to a government report, of forty legally binding environmental targets set post-Brexit, only four are on track to be achieved (Office for Environmental Protection, 2024). This shortfall highlights a critical planning deficiency, as noted by an agency staff member: “The biggest risk at the minute is that you’re not able to project five, ten years ahead. You can’t spot trends until they become issues and you end up not having the right strategies in place. You’re just fighting the consequences” (UK04).

Overall, it is not surprising that the EA is forced to engage in severe triage activity on a frequent level, due to a mismatch between the organization’s implementation load and its capacities. Yet, it is puzzling why that is the case, particularly when comparing the current situation to that of the early 2000s. During this period, the triage levels of the EA appeared to be more in line with other central implementers such as in Ireland and Denmark, for example. Centrally, the EA demonstrated a robust alignment between the expansion of its policy portfolio and its capacities. While the number of tasks in the organization’s portfolio did increase, so did the resources allocated for the implementation of new policies. This balance of responsibilities and resources underscored a period of enhanced capability within the EA, permitting the organization to manage its environmental mandates effectively:

There was a big increase of work and requirements, probably the late 90s, when things like the Urban Wastewater Treatment directive, a lot of the environment legislation came [from the European level]. But that was largely resourced. The next increase was probably the time of implementation of the Water Framework Directive, kind of mid 2000s when it took off and that attracted quite a lot of significant additional resources again.

The central question concerning the EA thus is why an organization that once effectively managed its responsibilities without significant reliance on triage is now a prime example of frequent and severe policy triage. This transformation from a period of proficient operational management to one marked by considerable implementation deficits warrants a deeper investigation into the underlying causes. Before we do so, however, we will first report on the state of policy triage on the local level.

6.3.2 Everything in Its Right Place: Contained Triage at the Local Level

Assessing the extent of policy triage among local implementers in England involves considerable complexity. Unlike their counterparts in the other countries within our study, English local authorities exhibit significant variations in terms of size and structural characteristics. Local authorities have been described as “an unusual patchwork of governance models” (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Dalton and Coggins2022: 2) or, as “slightly bonkers actually” according to one interviewee, before dryly reflecting that “if you were an alien landing in Britain, you’d just think, nah, start again” (UK09). These differences impact their capacity to manage policies effectively to varying degrees, with disparities often stark between jurisdictions, as vividly described by a former local official: “I came from a wealthy authority that took this [environmental health] seriously, the neighboring authority literally had one man and a dog. The dog was sick” (UK03).

Apart from the organizational properties, the informal processes also differ from authority to authority. In particular, when it comes to the mobilization of external resource, there exists significant variation with regard to the number of opportunities individual authorities are presented with and their abilities to capitalize on them (UK09). Consequently, authorities differ with regard to the extent to which they have to engage in policy triage. Deviations toward both ends of the triage spectrum can be observed as a result of the heterogeneous landscape of local government and the organizational ecology they operate in.

Still, compared to the EA, local authorities in England engage in policy triage less frequently and less severely, on average. However, they still face challenges due to resource and time constraints, which often result in the curtailment of tasks associated with the implementation process such as policy promotion. As one interviewee explained, “in some spaces we’re doing more with less. It does mean that some of the softer things, the nice things to do or the right things to do get lost a little bit” (UK05). One interviewee highlighted the process:

We look at the funding availability, we look at the policies and our priorities, and we try and match the two. Over the course of the last 10 years, it has meant that some of the things that we’d like to do have been either reduced in number or changed to enable us to meet our budgets. So stuff has been cut, stuff has been reduced and that, to be honest, has mainly been driven by a reduction in budgets.

In other words, while trying to manage their expansive mandates, local implementers must often sacrifice nonessential yet beneficial activities, making “things more sort of stretched” (UK02). In addition, environmental units within local governments find themselves in constant competition for resources with other policy areas, such as transportation, since these functions are frequently combined into a single administrative unit (UK05). This internal competition often requires trade-offs between economically, environmentally, or socially focused policies, making resource allocation a challenging and politically sensitive process (Jonas & Gibbs, Reference Jonas and Gibbs2003). As one interviewee highlighted: “whilst you might have a really sound policy around environment or waste, you have to balance that up against pressures for social care or in children’s services” (UK06). Ultimately, the prioritization of tasks and the distribution of resources are heavily influenced by elected officials, who must balance organizational needs with public expectations and feedback (UK05).

Yet, local authorities in England, despite increasing responsibilities and workloads, are somewhat shielded from the worst impacts of uncompensated overload due to three key factors. First, the policies they implement tend to be less complex, as high-risk and high-impact tasks remain primarily the responsibility of the national agency, reducing the need for sophisticated strategies at the local level (UK03). Second, while devolution has led local authorities to assume greater duties, a significant portion of the workload induced by policy accumulation still falls to the EA, as illustrated in Figure 6.3. Lastly, the financial strain on local authorities is mitigated by the New Burdens Doctrine, which mandates that any new responsibilities assigned to local bodies by the central government must be fully and properly funded. It stipulates that the department initiating the policy has to secure and transfer the necessary resources to cover the additional costs incurred by local authorities for implementing these new tasks (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2022). This system helps to protect local authorities from becoming overwhelmed by unfunded mandates, although challenges remain in managing their expanding roles.

Overall, the incidence of policy triage among local authorities has been relatively limited, with policies generally being implemented. Despite the high workload and being “incredibly, incredibly busy,” a local official expressed confidence in their efficiency, stating, “I like to think that not much gets past us” (UK05). This sentiment is echoed across various authorities, indicating that service delivery and implementation have not been broadly compromised by resource constraints. For instance, one representative assured, “we haven’t shut the front office or restricted hours” (UK06), suggesting that despite the pressures, public-facing services have maintained their availability and performance. However, the LGA has expressed concerns about the capacity of local authorities. In a recent report, the advocate of English local governments highlighted that environmental health departments currently have “no capacity to absorb and proactively implement new responsibilities other than at the expense of existing work” (LGA, 2024b). Thus, while local authorities generally manage to avoid extensive policy triage, the ongoing trends of budget cuts and increasing workloads may lead to more frequent and severe triage activities in the future.

6.3.3 Divided They Fall: Triage at the DWP

When assessing the level of policy triage within the DWP, a picture of a deeply divided organization emerges. Senior management often portrays an image of control and adherence to the strategic objectives, citing the complex reforms to the social welfare systems progressing despite some delays:

Some things are late; I won’t pull any punches there. Some things are late by design, and some things are late because it just isn’t possible to deliver to various timetables. But we’re moving forward and I’m confident we’ll deliver everything, just maybe not to every date that’s in the book at the moment.

One of those instances was the implementation of UC, for example, which has placed considerable pressure on DWP staff due to its complexity and the number of claimants needing to be transitioned from legacy benefits. The rollout process involved not only technical and administrative changes but also significant interactions with claimants, many of whom required personalized guidance to understand the new system and adapt to monthly payments. Furthermore, issues such as system glitches, delays in payments, and the need for frequent adjustments to eligibility criteria increased the need for ongoing support and intervention by DWP staff. The programs’ phased rollout, coupled with the subsequent need to address emerging implementation problems, has led to substantial operational demands, testing the limits of the department’s capacity. Despite those issues, however, senior management suggest that the challenges are manageable and primarily technical in nature (UK10).

While upper management at the DWP projects a scenario where operational challenges are just minor hiccups in an otherwise smooth rollout of reforms, the narrative starkly contrasts with the experiences of staff at lower tiers of the organization. Case managers, work coaches, and counselors describe their daily work environment as nothing short of implementation hell. Amid a declining workforce, these staffers handle an ever-growing number of complex cases, forcing them to engage in severe triage tactics to manage their overwhelming caseloads. This disparity in perspectives between the echelons of upper management and the rest of the organization is brought into sharp relief by the severe consequences emerging from the frontline. Staff members have reported “more threats of suicide by claimants, in some cases already attempted, sometimes successfully” (PCS, 2023: 8) as a result of staggering backlog of tasks and a prioritization system that is “failing to protect the most vulnerable citizens in society” (PCS, 2023: 3). Across the organization, triage is highly prevalent and becomes observable in a number of formal and informal routines. For one, management instructs staff to focus on easier cases in order to deal with surging demands as one caseworker highlighted:

Work coaches like me are currently told to prioritize mandatory appointments as we simply do not have the capacity to see all claimants. This means completely ignoring our heavy caseload of people with English as a foreign language.

Another common form of organizational triage involves prioritizing tasks based on the frequency of client interactions. Staff often allow tasks initiated by a single customer contact to remain in queues for extended periods, sometimes up to a year, while customers who call repeatedly are moved up the priority list (PCS, 2023: 30). This strategy, while unavoidable under the current operational strains, creates a de facto hierarchy of service that favors the most persistent claimants, neglecting those less capable of frequent follow-ups. What is more, the triage system at the DWP generally seems to be informed by how performance metrics can be “optimized” to present a more favorable operational picture. Staff have noted that claims involving health conditions that affect work capability are often sidelined for extended periods, for example. The official rationale given is to prioritize individuals who are ready to work; however, the underlying reason is that these more complex cases do not figure into the performance metrics that shape management evaluations (PCS, 2023: 9). Yet, triage activity is even more frequent and severe in the enforcement division of the DWP, as one staffer noted: “we are basically ignoring 90 percent of fraudulent activity. This essentially renders any Universal Credit review pointless – even if we find anything, there’s nowhere for the issue to go” (PCS, 2023: 5). In summary, policy triage has become ingrained deeply within DWP’s operational routines, leading to a scenario where “the absolute bare minimum is getting done and vulnerable customers are falling through the gaps” (PCS, 2023: 46).

Several factors contributed to this dire situation: Firstly, the number of claimants has surged, accompanied by increasingly complex procedures for claim assessment such as weekly appointments for clients, for example (PCS, 2023: 45). The resulting scenario was vividly illustrated by a caseworker at a Jobcentre, who reported managing approximately 230 claimants, each theoretically requiring half-hour weekly reviews. This expectation would necessitate each caseworker to dedicate a staggering 115 hours per week solely to these meetings, far surpassing realistic work capacity (PCS, 2023: 8).

Secondly, staffing increases introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic have been rolled back, despite a continuing rise in demands. As a result, DWP staff from various roles have reported a severe escalation in workloads per capita “since they sacked the majority of staff that they took on during Covid” (PCS, 2023: 38). Case managers and work coaches are particularly strained, each handling an overwhelming number of claimants. This operational strain is vividly illustrated by one team lead’s account:

My team of case managers had around 18,000 claims between 10 of us. This is already high but when you factor in peak leave and sickness, we spent a lot of the summer with around five people a day, 3,600 claims apiece. Every day felt like drowning, getting upwards of 60 messages from claimants to deal with, on top of all the other work. I’ve been in my role for several years and this was the worst it has gotten.

Lastly, the DWP is significantly impacted by other organizations reducing their public-facing services, shifting a greater burden onto its operations. As entities like Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs (HMRC) have minimized client interactions by transitioning most services online and cutting down on their street-level workforce, the DWP’s Jobcentres have become the de facto last resort for individuals in need. This shift has dramatically broadened the scope of inquiries handled by Jobcentres. One DWP staff member summarized the situation:

We are a last resort for many, many vulnerable people with housing issues, etc. Can’t get through to HMRC? Pop into the Jobcentre. Problems with your PIP [Personal Independence Payment] claim? Call into the Jobcentre. International student and want a part-time job? Call into the Jobcentre. Kicked out of your house and nowhere to live? Jobcentre. No food, no money? Jobcentre. Carer allowance enquiries, bereavement benefits… we get it all.

In conclusion, the empirical evidence on the DWP paints a picture of an organization divided between its management and street-level perspectives. The accounts from management often depict a controlled and stable operational environment, while frontline employees provide starkly contrasting testimonies of frequent and severe policy triage. Given the crucial role of street-level employees in social policy implementation and the extensive evidence of the impacts of policy triage they experience, it is clear that the DWP is significantly overburdened.

6.3.4 Policy Triage at TPR: An Administrative Oasis

TPR stands in stark contrast to the DWP, epitomizing what could be described as an administrative oasis amid the broader tumult of the social policy sector in the UK and opposed to the implementation hell the DWP finds itself in. Unlike the DWP, TPR exhibits minimal signs of overload and does not engage in substantive policy triage, aligning with the experiences of similar regulatory bodies in other nations, such as Ireland (see Chapter 7). While a staff member acknowledged increases in workload and complexity (UK11), they are not the result of additional policies primarily. Instead, increases in workload occurred due to the expansion of regulatory frameworks TPR is in charge of due to changes in the pension scheme landscape and the shifting of tasks from other organizations into the mandate of the regulator (DWP, 2023). For instance, alongside taking on public service pension plans, TPR has also adapted to significant developments within private sector pensions, such as the surge in Defined-Contribution (DC)Footnote 3 plans and the introduction of innovative structures like master trusts and collective DC schemes, which have grown to dominate the market in recent years, as one staffer explained:

So we had those two things running in tandem. We did a little bit on DC. We didn’t do anything for public service because we didn’t have any responsibility for it. Then, we’ve got responsibility for public service. We’ve also got more focus on DC because of the growth in DC. We’ve got master trust set up, which are a new thing, but are now 90 percent of the DC market. We’ve got super funds, which are new into DB [Defined-Benefits Plan]. We’ve got collective DC schemes, which are new. Most of these things have happened in the last three or four years. There’s a real ramp up.

TPR itself continues to evolve its regulatory framework to address emerging issues within its remit. This proactive stance is exemplified by its response to the climate crisis, integrating new assessment criteria that require pension funds to report on their environmental impact (The Pensions Regulator, 2023). Furthermore, TPR has broadened its focus to encompass equality, diversity, and inclusion within the governance boards of pension funds, reflecting its commitment to ensuring that these bodies mirror societal values and diversity. This expansion in oversight capability has led to a more nuanced approach to pension regulation, with a staffer noting, “the richness of the way that we look at schemes is growing. Types of schemes that we look at have grown. The complexity of the way that we look at things has increased. It’s very much been a kind of a rapid growth” (UK11).

Despite the increasing complexity and breadth of its regulatory duties, TPR has not resorted to any significant triage activities (UK11; DWP, 2023). Instead, the organization has not only managed its expanding mandate effectively but has also advocated for further extension of its regulatory scope. This proactive stance is driven by a desire to enhance its influence and effectiveness in the pensions sector. An internal evaluation by the DWP underscored TPR’s robust management, noting that it is “broadly well-run and well-regarded, as reflected in its consistently strong performance” (DWP, 2023: 7). Furthermore, TPR’s positive reception extends beyond internal assessments. Annual stakeholder surveys reveal high approval ratings, with 69 percent rating TPR’s performance as either very good or good, 94 percent viewing the organization as trustworthy, and 85 percent endorsing its regulatory approach (The Pensions Regulator, 2024: 1–3). Taken together, these findings illustrate TPR’s successful adaptation to its responsibilities, marked by the absence of policy triage, and its recognized role as a reliable and influential regulator in the pensions landscape.

In summary, the experiences with policy triage diverge significantly between the two implementers. TPR, responsible for overseeing pension policies, rarely engages in triage, demonstrating operational stability comparable to similar regulatory bodies, such as the Pensions Authority in Ireland (see Chapter 7). In contrast, the DWP faces frequent and severe triage challenges. These difficulties are driven less by the accumulation of new policy mandates and more by the enduring weight of long-standing obligations, exhaustive reforms, additional requirements to existing policies, and declining resources. Compounding these pressures is the closure of numerous adjacent social services, which has led to a growing number of individuals turning to the DWP and its Jobcentres as a provider of last resort, further straining its capacity. A severe staffing crisis exacerbates these issues, with the greatest impact felt at the frontline level, where operational demands are most acute.

6.4 Standing in the Rain or Good Day Sunshine? Determinants of Policy Triage in the Environmental Sector

With regard to environmental policy implementation, the account of triage in the environmental sector reveals two puzzling developments. First, the EA experienced a shift from relatively effective implementation in the early 2000s to a situation marked by frequent and intense triage in more recent years. Second, local implementers consistently fare better than their central counterpart, a notable exception compared to other local bodies in our sample. To account for this variation, we explore how our three mechanisms theorized in Chapter 2 account for such marked variation.

6.4.1 Blame-Shifting in the Environmental Sector

Blame-shifting significantly influences the dynamics of policy triage among environmental implementers in England. Unlike countries such as Ireland, where regulatory agencies typically exhibit greater formal autonomy and communicative capacity, the English context illustrates distinct patterns in the distribution of blame among implementing entities (Elston, Reference Elston2014). Despite the EA status as an NDPB, English policymakers frequently use it as a scapegoat for policy failures (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Elston, Bilous, Flinders, Hinterleitner, Rhodes, Weaver and Dimova2024). This behavior contrasts with the situation in Ireland, where policy formulators are less inclined to engage in such blame allocation. Notably, local authorities in England are substantially insulated from this blame-shifting, underscoring the unique interplay of accountability and responsibility within the country’s environmental policy landscape.

Someone to Blame: The EA as a Useful Scapegoat

In the case of the EA, politicians easily are able to dump responsibility for implementation failure onto the organization. The agency’s independent status has made it a convenient target for politicians to shift blame and offload responsibility for implementation failures. One avenue used for blame-shifting is facilitated by the agency’s ability to generate licensing revenue, which some policymakers argue should mitigate the impact of stagnant or even reduced government funding. For example, a former environment secretary attributed river pollution not to budget cuts but to “agency management failure,” despite the fact that the agency’s budget for monitoring license conditions is supposed to be fully cost-recovered (Elliott & Capurro, Reference Elliott and Capurro2023). He also paradoxically described the EA as a “generously resourced organization,” despite a decline in funding during his tenure (Adie, Reference Adie2023).

This example, indicative of an established pattern of blame-shifting seems to intensify during crises, turning the agency into a scapegoat for broader governmental inadequacies. A notable instance occurred during the flooding in 2014. The government criticized the EA for its delayed response in dredging the county’s main river – an action widely recognized by experts as ineffective for flood management. Eric Pickles, the then communities secretary, publicly blamed the agency, questioning its expertise on national television: “We were dealing with the Environment Agency,” he remarked. “We thought we were dealing with experts” (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2024).

The culture of blaming the EA appears to have been entrenched during the Cameron government’s tenure from 2010 onwards. Under the coalition government, there were systematic efforts to diminish the agency’s visibility and voice, perceived as obstructive to economic development. In 2014, significant steps were taken to reduce the agency’s autonomy; its independent website was shut down, and its press office was consolidated with that of its parent department, DEFRA, effectively limiting the EA’s ability to communicate independently. Barbara Young, who led the EA from 2000 to 2008, described the government’s approach as wanting the agency “to be seen but not heard,” adding that there was an intention to “muzzle it the minute it starts to bark” (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2024). This sentiment was echoed by John Selwyn Gummer, the conservative minister responsible for establishing the EA in 1995. He criticized the coalition government for lacking confidence in their handling of environmental issues and – feeling threatened by criticism – leading them to try and suppress the agency’s influence and voice (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2024). This strategy of silencing not only limited the EA’s ability to advocate for environmental concerns but it also “made it nigh impossible to defend itself publicly” against unjustified attributions of blame by the formulating level (Kaminski, Reference Kaminski2016). As one interviewee noted, “what the environment is experiencing isn’t a failure of ours, it’s a failure of industry. But we are seen as the guardians of that” (UK03). Furthermore, this blame culture has spilled over to the public domain, affecting individuals working at the agency:

Staff will also get some not very nice personal attacks on them through social media or in public meetings. You get that from the industry, traditionally. But the fact that the public will also… Staff have to take steps to protect themselves, their identity, their safety.

Overall, the EA is highly susceptible to blame-shifting by policymakers at the formulating level, who have effectively managed to dismantle any potential limitations over time. This strategic undermining has left the EA exposed to criticism and responsibility for environmental issues that often stem from broader industrial practices or policy failures. The systematic reduction in the EA’s communicative autonomy and public presence has facilitated this process, allowing government officials to redirect blame toward the agency without having to expect major rebuttals. This stands in strong contrast to other central implementers such as the EPA in Ireland, which seems immune to blame-shifting due to stellar reputation and its close, cooperative relationship with the policy formulating level, characterized by mutual respect and trust (see Chapter 7).

A Less Convenient Target: Limited Blame Goes Toward Local Authorities

Blame-shifting dynamics for local authorities markedly contrasts with those observable for the EA. The local level generally experiences minimal blame-shifting from the central government, largely due to several key factors. Firstly, the central government remains reluctant to delegate significant powers or funding to the local level, thereby maintaining tight control but also a high level of responsibly for local authorities (UK09). Secondly, the EA acts as an inadvertent shield for local authorities by absorbing most of the blame, leaving little scope for blame to be redirected downward. Unlike in countries such as Ireland, where central agencies may publicly critique local authorities for failures to implement certain policies or meet environmental targets, the EA tends to adopt a more lenient and cooperative approach toward local implementers in England. This relationship is often perceived as a partnership rather than a strict regulatory supervision, fostering “incredibly positive” interactions (UK05; UK04).

Moreover, the prevalent relationships formed by party politics further deter blame-shifting. Local and national politicians often share affiliations, creating a network of mutual accountability that discourages public criticism across different governmental levels. As described by a local authority member, there is a “constant dialogue with government on the national level,” involving multiple tiers from members of parliament to local councilors, which aligns their objectives and reduces the likelihood of “friendly fire” or internal party criticism (UK05; UK02). In contrast, the EA, as a nonpartisan body, presents a more convenient target for blame, sparing local authorities from significant scrutiny and shifting the focus away from them in discussions of implementation failures. The situation of English local authorities also differs markedly from comparable actors in other countries. In Ireland, for example, there are few limitations preventing policy formulators from shifting blame onto local implementers. Unlike English local authorities, their Irish counterparts cannot rely on party–political channels to limit blame-shifting. Furthermore, while the EA in England often acts as a shield for local authorities by absorbing blame, the EPA in Ireland plays a more confrontational role. Rather than deflecting criticism away from local implementers, the EPA often functions as a “burning glass,” highlighting the shortcomings of local city and county councils publicly (see Chapter 7).

6.4.2 Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization

While both the EA and the local authorities face considerable financial and staffing pressures, their ability to mobilize external resources differs markedly. The EA, as an NDPB, operates within a constrained financial framework, heavily reliant on government grants-in-aid and revenue from licensing fees. Austerity-induced budget cuts and government-imposed constraints on its communicative autonomy have further eroded its capacity to mobilize additional resources. By contrast, local authorities possess a broader set of tools for resource mobilization. They benefit from more direct engagement with central government through party–political networks and advocacy efforts by the LGA. Moreover, their capacity to tap into diverse funding streams, such as competitive grants, public–private partnerships, and commercial ventures, provides them with greater flexibility. Lastly, English local authorities increasingly engage in collaboration with each other. In 2017, “344 (97.5 per cent) of English local authorities participated in a total of 338 partnerships involving at least one other council” (Dixon & Elston, Reference Dixon and Elston2020: 756). However, the extent to which local authorities succeed in mobilizing resources depends on their administrative capacity, political alignment with the central government, and local expertise in grant applications. This section explores the contrasting opportunities for resource mobilization available to the EA and local authorities, shedding light on how these differences influence their capacity to maintain operational stability.

A Hard Day’s Night: Diminishing Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization at the EA

The austerity measures imposed across the public sector in the wake of the financial crisis disproportionately impacted the EA’s opportunities to mobilize resources externally. Cuts in public spending were exacerbated by the Cameron government’s preference for a more business-friendly approach at the expense of environmental concerns. A retired EA staff member suggested that the budget reductions served as a mechanism to diminish the agency’s influence, stating, “I think the cuts were also a way of silencing the EA” (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2024). This sentiment was echoed more starkly by Tom Burke – a former government advisor – who argued, “The government knew it couldn’t have a political argument about winding back environmental law, because the public likes environmental law. So instead, they set out to kill environmental law by stealth” (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2024). This strategy highlights a tactical reduction of the EA’s operational capacity as a means to indirectly weaken environmental regulations. This approach bears similarities to tactics used by the Reagan administration, which, unable to dismantle environmental policies, engaged in sabotage of the American EPA via budget cuts and staff reductions (Ansell et al., Reference Ansell, Comfort, Keller, LaPorte and Schulman2021; Golden, Reference Golden2000).

Despite recent increases in funding for the EA, the allocation has primarily targeted new initiatives rather than reinforcing core environmental functions which continue to suffer from long-term budget cuts initiated since the 2008 financial crisis. A senior staffer elucidated the dilemma:

So overall the amount of money we’ve got is significantly more. But our historic core functions have not been given new money and indeed over the period since, more than 10 years now, really since the austerity that followed the financial crisis in 2008, our core funding has been eroded both in absolute terms but also of course in real terms because of wage and other inflation over that period. […] Some of our core historic functions, monitoring environments, enforcing regulation are things that have to be funded by grant in aid from government. […] The squeeze has been on the ongoing core environmental functions.

Additionally, much of the funding for these essential activities remains tied to grants-in-aid, which are inherently temporary and thus unreliable for long-term planning. This precarious financial setup forces the EA to adopt drastic measures to secure necessary resources, as articulated by another official:

If we know we definitely haven’t got enough money to do the job, we might make a decision to say, well, actually, even though there’s a legal risk and the reputational risk of not doing this and environmental risk, we’re actually not going to do it until we have the resources to do it. Because why is government going to fund you, give you more money to do something which you’re already doing? So actually, until you stop doing it, you can’t necessarily make the point that we’re not actually resourced up when you do the work.

Compounding the financial challenges, the EA also struggles to attract and retain skilled personnel. This issue has been exacerbated by a shift in public perception and organizational reputation, as reflected in the stark decrease in job applications:

We used to get hundreds of people applying for jobs. Everybody wanted to work for the Environment Agency because they were doing such good work. And now we’re lucky if we get three people applying for each job.

This decline in staff recruitment and retention highlights the agency’s ongoing difficulties in maintaining operational efficacy amid financial and reputational constraints. Consequently, recent initiatives aimed at bolstering staff numbers only led to a marginal net increase in employees from 2014 to 2024. The agency hired 8,967 new staff members during this period, but this was almost exactly offset by departures, resulting in a net gain of only 140 staff in an organization of approximately 10,000. A significant factor contributing to the staffing crisis is the lower salary levels offered by the EA compared to other departments under DEFRA, making it less competitive and leading to a high turnover rate (UK03; McGlone, Reference McGlone2024). This situation has led to claims that the agency is “haemorrhaging staff” (Colley, Reference Colley2024).

Local Authorities: They Can’t Always Get What They Want, But When They Try Some Time, They Get What They Need

In contrast, the large part of local authorities enjoys good relations with the central government. As one representative put it: “we do have a great feedback loop to central government. So if there is a need for support, we can feed back to that central government loop and let them know that we do need more support here and more support there” (UK05). In addition, the LGA acts as a strong advocate for the needs and interests of local authorities vis-à-vis the government in Whitehall (UK06).