1 Introduction and Methodology

The Great Palace of Constantinople served as the residence of the Byzantine emperors for a millennium and stands as one of the most significant examples of aulic architecture during the Late Roman and medieval periods. The objective of this Element is to provide a comprehensive examination of the palatial complex, addressing specific challenges along the way.Footnote 1

The Great Palace was located at the southeastern corner of the Byzantine peninsula, within the first region of Constantinople, in close proximity to the city’s most prominent monumental landmarks, such as Hagia Sophia, the Hippodrome, the Augoustaion square, and the Baths of Zeuxippos. From the first hill, the complex descended southward down the slope, towards the shore of the Marmara Sea. This was achieved by a series of artificial terraces. The total area of the complex encompassed approximately 16 hectares. However, the palace would only reach such dimensions through successive expansions. The original core, known as Daphne, was established by Constantine (r. 306–337) at the same time as the construction of his new capital. Situated in the upper part of the hill, it was adjacent to the Hippodrome. Upon entering the palace through the Chalke – its main gate, located near the Great Church – one would encounter the barracks of the guard, arranged across several porticoes. Beyond the barracks were various significant halls dating back to the Late Antique period, including the Augousteus, the Nineteen Couches, and the Consistory. This palace remained the heart of the imperial residence until the sixth century, when it gradually ceded importance to the lower complex, by the seashore. The Lower Palace was the result of the amalgamation of several noble residences, such as the Palace of Hormisdas and the houses of various Theodosian princesses. By the tenth century, the Chrysotriklinos had become the focal point of this complex, around which were situated the imperial private quarters, the palatine churches of the Pharos Terrace, and the maritime façade known as Boukoleon.

Prior to embarking upon the study of the palace, it is important to mention some of the main approaches to the complex. In the mid nineteenth century, Jules Labarte is credited with the first comprehensive modern study of the palace.Footnote 2 At the turn of the century, subsequent authors, such as Jean Ebersolt, integrated a more meticulous analysis of the sources with first-hand knowledge of the area’s topography.Footnote 3 In the mid twentieth century, significant archaeological findings were made, which will be discussed in Section 3.9.1. Rodolphe Guilland’s studies from this period were particularly noteworthy, despite being limited to textual analysis.Footnote 4 Cyril Mango’s book on the Chalke Gate, published around that time, represents one of the most significant approaches to the palace, integrating, for the first time, analysis of archaeological, textual, and visual sources.Footnote 5 In the subsequent decades, there was a shift towards prioritising the analysis of archaeological remains over a broader study of the palace. From the 1990s onwards, along with the beginning of new excavations, there has been a revival of interest in the palace from a topographical and typological perspective. In this context, some of the most noteworthy authors include Jan Kostenec, Jonathan Bardill, Michael Featherstone, Albrecht Berger, and Nigel Westbrook, with the latter offering the most recent interpretation of the palace.Footnote 6

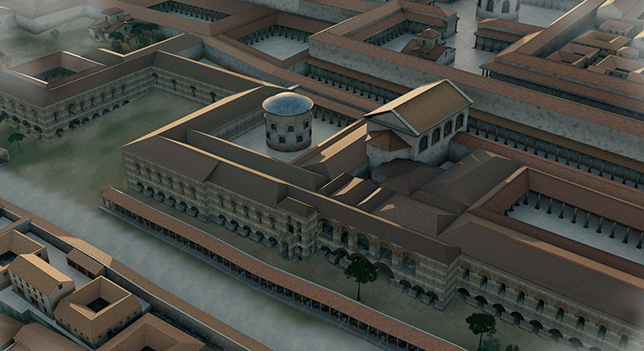

The primary objective of the present approach is to elucidate the historical development and functional evolution of the palace buildings, with the ultimate goal of establishing a topographically coherent layout of the ensemble (Plan 2 – hypothetical). For this purpose, it will be necessary to examine a range of sources, including archaeological, written, and visual materials. Once the location and features of the structures have been identified, they will be compared with better-known examples in order to determine their appearance and possible typological parallels. Some of the preceding approaches to the palace have been complemented by reconstructive drawings and, in more recent times, by 3D virtual reconstructions, such as the one found in the Byzantium1200 project.Footnote 7 For this approach a new reconstruction has likewise been created (Figure 1), with the goal of conveying a general idea of the palace and its layout, including decorative elements and furnishings, which are essential for the understanding of medieval architecture.

Figure 1 3D reconstruction of the Great Palace of Constantinople in the tenth century.

2 Evidence for the Study of the Palace

2.1 Archaeological Evidence

A comparison of the entire area occupied by the palace with the surviving evidence may lead to the conclusion that the archaeological remains are scarce (Plan 1 –archaeological). On occasion, Ottoman buildings, such as the Blue Mosque, have been erected over areas previously occupied by some central elements of the complex, such as the Constantinian Daphne. Nonetheless, some significant ensembles have survived, like the façade of the Boukoleon over the Marmara, while others of great relevance have been excavated, such as the mosaic peristyle or the Chalke Gate. Consequently, the archaeological remains should be regarded as the primary source of information for a topographical study of the palace. The first comprehensive archaeological survey of the area is credited to Ernest Mamboury and Theodor Wiegand, who documented much of the Byzantine evidence that emerged in the eastern end of the peninsula at the beginning of the twentieth century. Of particular interest are the remains found beneath the Palace of Justice, which burned down in 1933. The surveyed areas labelled as Mamboury Aa, Ab, and Ac comprised the infrastructure of what were once the Palace Gate, barracks, administrative offices, and a series of galleries that traversed the palace from north to south. Further south, the team proceeded along the galleries towards the Marmara Sea and documented the Mamboury B, featuring a polygonal apse and the sole standing structure of the Upper Palace, a kochlias or spiral staircase known as the Ramp House. Continuing southward, the Mamboury D group, which comprised additional galleries, the infrastructure of a rectangular chamber, and a cistern, hinted at the next significant discovery in the area: the mosaic peristyle.Footnote 8

The peristyle was discovered in 1935 by a British team. The war interrupted the excavations, which were resumed in 1952 and confirmed that a large apsed hall overlooked the eastern side of the courtyard.Footnote 9 In the 1980s and 1990s, a team from the Austrian Academy of Sciences undertook the appropriate restoration of the peristyle and transformed it into a museum.Footnote 10 The archaeological site was notable not only for its size, comparable in plan to that of Hagia Sophia, but also for the mosaic that adorned the four porticoes forming the peristyle. Despite the significance of the discovery, there is currently no consensus regarding the dating, patronage, and identity of the complex.

Over the past few decades, Turkish archaeologists have been particularly active in the area surrounding the Palace of Justice. The excavation of the Mamboury Aa complex was resumed, with the uncovering of the Chalke Gate and a chapel. In a northward direction, parallel to Hagia Sophia, significant findings were made, including the apse of another chapel, Late Roman mosaics, a bath complex dating to the reign of Justinian (r. 527–565), and infrastructures featuring frescoes, likely associated with the Magnaura.Footnote 11 It is similarly important to acknowledge the contributions of Eugenia Bolognesi, who initiated a comprehensive review, regrettably unfinished, of all the archaeological remains of the palace. However, she provided one of the most crucial insights for studying the ensemble: the systematisation of the terraces upon which the palace was raised.Footnote 12

2.2 Written Sources

The most extensive body of information about the palace is derived from written sources. Among them, the most significant is the Book of Ceremonies, which was compiled in the mid tenth century at the behest of Constantine VII (r. 913–959). The emperor, raised as a hostage in the palace, was aware of the crucial role that ceremonies played in reflecting the integrity of the imperial institution. This was defined by the Byzantines as order, taxis, a key concept of imperial discourse. Therefore, the purpose of the Book of Ceremonies is to compile the imperial ritual to ensure its accurate execution and transmission to future generations, thus maintaining the harmony of the State.Footnote 13

The Book of Ceremonies is the result of a revision undertaken during the reign of Nicephorus II Phocas (r. 963–969). It consists of two books. The first one begins with religious ceremonies, describing the major fixed feasts, such as Christmas. It then proceeds to the movable ones, and some of particular interest to the Macedonian dynasty, such as the inauguration of the Nea Ekklesia. Subsequently, the text proceeds to delineate civil ceremonies: coronations, wedding rites, and promotions. Finally, we find the protocols necessary for the Hippodrome and the emperor’s interaction with the factions. The first book ends with a fragment from a lost work by Peter the Patrician, a contemporary of Justinian. The second book begins with some chapters that follow the organisation of the first volume, featuring processions, receptions, and promotions. However, the structure becomes increasingly complex thereafter, likely due to the inclusion of materials that were never properly organised, such as rituals illustrated with historical events, a brief history of the Byzantine emperors, a list of imperial tombs, inventories of palace warehouses, and salary lists. Finally, a manual for banquets composed in 899, the Kletorologion of Philotheos, and a list of bishoprics, attributed to Epiphanius of Salamis, were appended.

The importance of the Book of Ceremonies for the understanding of the palace lies in the method chosen to systematise the rituals, which was based on a detailed account of processions. This required a meticulous description of the itineraries through the palace, detailing in strict order the connections between the halls, chambers, and galleries. The Book of Ceremonies also addresses logistics and ornamentation, describing the veils, thrones, tables, and couches displayed during banquets and audiences, as well as the lamps and precious objects that were hung from arches and domes. This is important not only in its own right but also because it often provides additional insights into the architecture, such as the number of arches or the presence of an apse. Thus, after a proper interpretation of the itineraries, we can achieve a reasonably accurate depiction of the palace as it stood at the time of the compilation.

However, the Book of Ceremonies has its limitations: it was written by and for individuals familiar with the palace, and it never mentions anything that is not absolutely necessary. Therefore, we have to rely on other sources, such as histories, topographic records, and travel accounts. Some important texts in this regard, including detailed descriptions of the palace, are Theophanes Continuatus, the Patria of Constantinople, and the Embassy of Liudprand, bishop of Cremona, among many others.

2.3 Visual Evidence

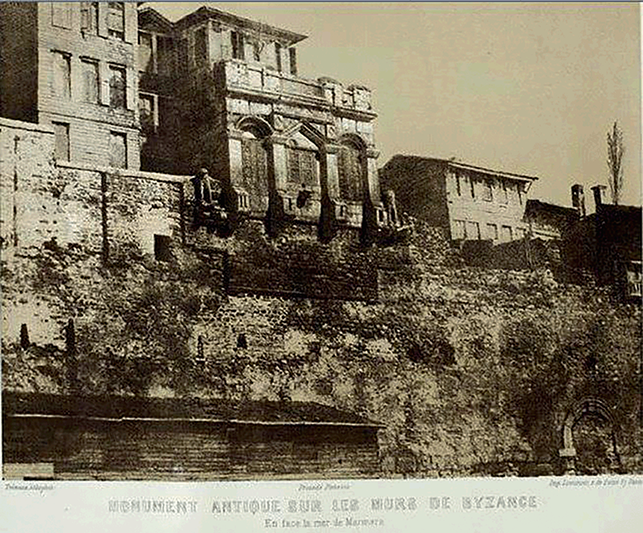

Although little remains of the palace, visual representations of certain buildings have survived. Some of these, such as the Late Antique base of the Egyptian obelisk or the twelfth-century Madrid Scylitzes manuscript (BNE, VITR/26/2), are contemporaneous with the complex and are therefore of considerable importance. However, most of them date from the Ottoman period, when Turkish miniaturists and Western travellers shared a common interest in recording the ruined monuments of the Byzantine past, which they regarded as both marvellous and exotic. Notable examples include the maps by Cristoforo Buondelmonti and Matrakçi Nasuh, engravings by Pieter Coecke Van Aelst and Willey Reveley, and even daguerreotypes, such as Pierre Tremaux’s 1850 photograph of the Boukoleon balcony.

3 The Upper Palace

According to Bolognesi, the Upper Palace was built on three terraces:

(a) At 32 and 31 m.a.s.l. stood the main avenue of the city, the Mese, the Hippodrome, the Baths of Zeuxippos, and the Augoustaion square. In addition, the Chalke Gate and the Palace of Daphne were situated at the same level, along with the barracks of the guard and the administrative offices. This area roughly corresponds to Atmeydanı Square, Sultan Ahmet Park, the Four Seasons Hotel and its surroundings, and the Blue Mosque.

(b) At 26 m.a.s.l., on the eastern flank of the palace, the Mamboury galleries B and D, as well as the peristyle of the mosaics, can be found. These structures run through Kutlugun Sk. and Akbiyik Cd., where remnants of some of them, like the Ramp House, are still visible. The museum of the mosaics is situated beneath the southeastern corner of the Blue Mosque, within the present-day Arasta Bazaar.

(c) At 21 m.a.s.l., Bolognesi documented the floor of the infrastructure that supported the previous buildings. This level would have served as a transition between the Upper and Lower Palaces.Footnote 14

Besides the presence of these levels, it is essential to highlight that the Upper Palace was organised along two axes, one to the west and another to the east. This allows for a systematic study of the upper complex. Starting from the original core, we will follow these routes clockwise until we return to our starting point. The western route will take us through Daphne and the Kathisma, the Tribunal and the Nineteen Couches, the barracks of the scholarioi and the exkoubitores, and the Chalke Gate. Upon reaching the northernmost point in the Magnaura, we will descend along the eastern axis, passing through the Ovaton, the barracks of the kandidatoi, and the peristyle of the mosaics. Subsequently, we will return to the vicinity of Daphne, at the courtyard known as the Covered Hippodrome. Finally, we will address the expansions of the Upper Palace over the centuries (Figure 2).

Figure 2 View of the Upper Palace.

3.1 Daphne

Although not explicitly stated in the sources, it is thought that Daphne was the original core established by Constantine, and it is already documented in the fifth century. Its name likely originates from the triumphant symbolism associated with laurel wreaths in Late Antiquity. This is corroborated by the denomination of some of the buildings that were part of the complex, such as the chapel of St Stephen (his name coinciding with the word for crown or wreath), the portico of the Gold Hand, and the Stepsimon or coronation hall. The complex became emblematic, subsequently serving as a model for the imperial palace in Ravenna, which was given the same name (ad Laureta) (Figure 3).Footnote 15 Nothing remains of Daphne and its neighbouring structures, and the Blue Mosque now stands on its former site.

Figure 3 Mosaic of the Palatium in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, sixth century.

Initially, the term Daphne may have encompassed the entire palace. However, by the tenth century, it referred only to the Augousteus triklinos (audience or banqueting hall) and adjacent rooms. At that time, the complex continued to serve as a significant ceremonial venue, although the emperor’s main residence had already shifted to the Lower Palace. Access to the Augousteus was gained from the Covered Hippodrome or the Triconch via a series of internal galleries.Footnote 16 Before reaching the hall, adjacent to the Galleries of Daphne, two chapels were located, one consecrated to the Virgin and another to the Trinity. It is known that both chapels were connected to each other, and that the latter had an adjoining chamber where relics were kept. Further on was the baptistery.Footnote 17 The Augousteus was the main audience hall of the foundational complex. It was closely associated with the emperor’s residence, and he would frequently traverse it to reach his private chamber in Daphne, to access the Kathisma of the Hippodrome, or, alternatively, to reach the grand portico of the Upper Palace, known as the Tribunal (Figure 4). The Augousteus plays a pivotal role in the Book of Ceremonies, serving as the venue for the coronation of the empress and the solemn appearance of the emperor, already crowned, before the court. Consequently, it is referred to as Stepsimon, Stepahana, or Domus Coronaria.Footnote 18

Figure 4 View of the Tribunal, with the Augousteus and its portico, the Gold Hand, and the triklinos of the Nineteen Couches.

We know some details about the Augousteus’s structure and elements. The assembly of courtiers was typically arranged in a Π-shaped configuration, which suggests a rectangular plan.Footnote 19 It is beyond doubt that an apse was present at the southern end of the structure.Footnote 20 The aforementioned internal galleries must have reached the triklinos from its eastern side, as the chapels had to be oriented in this direction. It is also known with certainty that the Octagon, situated adjacent to the Augousteus in the west, served as a dressing room where the cubicularii (attendants of the imperial bedchamber) attired the emperor prior to his appearance before the court.Footnote 21 To the north, the hall opened onto the portico of the Gold Hand in the Tribunal through a single great door, from which curtains bearing designs of birds were hung.Footnote 22 Thanks to these clarifications, it can be inferred that the Augousteus had a rectangular plan with an apse and opened onto a portico. In summary, it had the canonical appearance of a typical triclinium from Late Antiquity, exactly like the one unearthed by the mosaic peristyle.Footnote 23 Furthermore, the presence of additional structures suggests that the building had a north–south orientation.

As previously stated, the western side of the Augousteus provided access to the Octagon. Besides its function as a dressing room, the Octagon also served to distribute access to several spaces. The emperor’s private chamber was situated on one side of the building, while the chapel of St Stephen was located on the opposite side.Footnote 24 Looking west, this chapel, or more likely a passageway connected to it, led to the spiral staircase leading to the Kathisma of the Hippodrome.Footnote 25 St Stephen was the most important chapel in Daphne. Originally, it was used as a winter chamber but was later consecrated to the First Martyr by Pulcheria (r. 450–453).Footnote 26 Its primary function was to host the imperial wedding liturgy and the blessing of water on Epiphany. Inside the chapel were preserved the Cross of Constantine, sceptres, diptychs, and gold insignias belonging to the kandidatoi.Footnote 27 The only known feature of the structure is a narthex.Footnote 28

3.2 The Kathisma

In Rome, the Palatine Hill overlooked the valley of the Circus Maximus. The propaganda potential of connecting the circus to the Palace was quickly recognised by the emperors. Augustus (r. 27 BC–AD 14) erected the original Pulvinar, which Trajan (r. 98–117) later transformed into a monumental tribune. By the late third century and during the Tetrarchic period, the hippodrome–palace formula had already been established, with significant examples such as the urban palaces of the Sessorium in Rome, Milan, Sirmium, Thessalonica, Nicomedia, and Antioch, as well as the villa of Maxentius along the Appian Way.Footnote 29 While historical accounts agree in suggesting Constantine’s desire to emulate Rome, his construction of a palace adjacent to the circus merely reflected the customs of his era. In Constantinople, the imperial box overlooking the circus was designated as Kathisma and remained in use, albeit deteriorated, until the late twelfth century.Footnote 30 It is probable that it was destroyed by fire in 1204.Footnote 31

The Kathisma was situated on the eastern flank of the Hippodrome, although its precise location remains a matter of debate. The majority of authors posit that the Kathisma stood in front of one of the main monuments of the arena, such as the Egyptian obelisk, the bronze serpent, or the masonry obelisk. The latter appears to be the most plausible hypothesis, as the masonry colossus stands in front of a thick pillar of the Hippodrome’s infrastructure (Mamboury H1), and because it is the sole monument of the spina (a central strip dividing the arena of a circus) mentioned in connection with the Kathisma (Figure 5).Footnote 32

Figure 5 View of the Kathisma.

Arriving from the Galleries of St Stephen, one would reach the kochlias. The original staircase, being too narrow for imperial processions, was enlarged by Justinian.Footnote 33 Upon ascending, the emperor would not arrive at the intermediate level but rather at the uppermost one, designated as the parakyptika (overlooking galleries). From this point, he could observe the arena privately, behind a screen. Once the preparations had been completed, he descended via a stone staircase to a private chamber on the main level. There, the cubicularii dressed him in the chlamys and crown. Afterwards, he passed through a small dining room to reach the great dining hall, where he was greeted by the court. Finally, the large door leading to the imperial box would open and the emperor sat on his throne to watch the races. The box and the flanking porticoes of the senators were also reformed under Justinian, shortly after his accession to the throne, in 528.Footnote 34 Upon returning to the palace, the emperor could access the kochlias directly without having to ascend to the parakyptika.Footnote 35

The lower level of the Kathisma on the circus side was known as skamma, stama, or Π. This name referred to the recessed area in front of the imperial box, where athletes contended and victorious charioteers received their prizes. Sometimes this area is also referred to as Daphne of the Hippodrome, after the laurel wreaths awarded to the victors.Footnote 36 The Karea Gate, which opened onto the Hippodrome, led through a passage to the Covered Hippodrome, within the palace. The denomination of this gate likely originated from a nearby statue of Artemis, as it coincided with the name of the main festival of the goddess in the Peloponnese.Footnote 37

Due to its public nature and its connection with the Hippodrome, the Kathisma is among the most visually documented monuments of the palace. Consequently, we can picture the exterior appearance of the Kathisma and visualise many of its elements as described in the sources. In addition to the well-known bases of Theodosius’s obelisk, evidence from the 5th and 6th centuries includes the bases of the monuments celebrating the charioteer Porphyrius, the Kugelspiel of Berlin, and various consular diptychs featuring the stama. Their medieval counterparts are the eleventh-century fresco from Hagia Sophia in Kiev (Figure 6) and the miniatures from the Scylitzes manuscript (fols. 55 r–55 v). The different levels of the Kathisma are depicted in these artefacts with the main floor featuring the imperial throne, its canopy, and, in the background, an arcade under which the courtiers stand. On the upper level we can clearly observe the parakyptika with the lattice. These images also represent some of the changes undergone by the Kathisma. For instance, in the earliest examples, we can see multiple gates and staircases ascending from the arena to the upper levels. Except for the Karea, these features are absent in the Kiev fresco, having been suppressed by Justinian after the Nika riots.Footnote 38

Figure 6 Kathisma of the Hippodrome in a fresco from St Sophia in Kiev, eleventh century.

3.3 The Tribunal and the Gold Hand

The Tribunal was the main porticoed courtyard (exaeron, araia) of the Upper Palace (Figure 4).Footnote 39 It was overlooked by the Augousteus and the triklinos of the Nineteen Couches, the former from the portico of the Gold Hand, to the south, and the latter from the portico of the Nineteen Couches, to the west.Footnote 40 The triklinoi of the guard, namely, the hall of the kandidatoi to the east and the halls of the exkoubitores and the scholarioi to the north, protected the Tribunal from the remaining sides. The main function of the Tribunal was to provide an open space for the courtiers and the palatine regiments to assemble and acclaim the emperors. In this regard, we know that the dances of the circus factions were celebrated there until the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641).Footnote 41

The most significant feature of the Tribunal was the Gold Hand, that is, the southern portico of the courtyard. Its columns were made of polychrome marbles taken as spolia from Delphi. At its centre stood the dikionion, a monumental porch with two columns that led to the Augousteus. While the origin of its name remains unknown, the Gold Hand is undoubtedly related to the coronation rituals and the Daphne complex. When the crowned emperors left the adjoining hall through the great door, they stood beneath the dikionion, flanked by patricians and senators. The veil hanging from the columns was then removed, and the emperor was acclaimed by the court gathered in the Tribunal.Footnote 42

3.4 The Triklinos of the Nineteen Couches

The largest hall in the palace was the triklinos of the Nineteen Couches (Figure 4). Since its foundation, its primary function was to host banquets held by the emperor. The hall was constructed by Constantine, and it may have been operational as early as 325, as the celebrations accompanying the Council of Nicaea were held there. At that time, it was already characterised by the succession of couches placed on each side and the splendid coffered ceiling adorned with jewelled crosses.Footnote 43 It served a number of other purposes, including the display of the deceased emperors.Footnote 44 The southern end of the triklinos, where the imperial table was placed, was aligned with the portico of the Gold Hand, to which it was connected through a door. This section of the hall stood above several steps and was separated from the rest of the space by a railing adorned with silver columns.Footnote 45 The most significant pieces of evidence about the location of the banquet hall are that, as previously stated, it overlooked the Tribunal and that, according to Liudprand, it was very close to, or even adjoining, the Hippodrome, with a north–south orientation.Footnote 46 The Nineteen Couches remained in use until the tenth century, when it was restored by Constantine VII, who added a new coffered ceiling composed of octagons carved with gilded vine leaves.Footnote 47 From this point onwards, the hall is no longer mentioned in the sources.

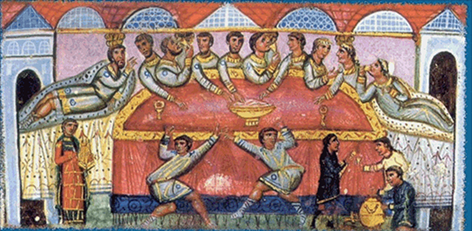

As inferred from its name, this triklinos was renowned for its distinctive arrangement of nineteen tables with a sigma shape, where guests would dine while reclining on couches (akoubita), following the ancient Roman custom (Figure 7). The emperor’s table was situated at one end, while the remaining eighteen tables were arranged on either side, in two rows of nine tables facing each other. With twelve guests per table, the total number amounted 228. Courtiers were arranged hierarchically, both on their couches and the hall, with proximity to the emperor indicating the person’s importance.Footnote 48 Foreign dignitaries frequently attended these gatherings, which featured various spectacles: Liudprand of Cremona and Harun ibn-Yahya described the tableware, all of gold and silver, and how the food was transported along the hall in large golden vessels, so heavy that they had to be carried on carts guided by a pulley mechanism hanging from the ceiling. Singers entertained during the dinner, while the evening concluded with a series of balancing acts and acrobatics.Footnote 49

Figure 7 A banquet featuring akoubita and sigma-shaped tables from the Book of Job, eleventh century. Monastery of St Catherine, Sinai, Cod. Sin. Gr. 3, fol. 17v. From Weitzmann, Kurt and Galavaris, George, The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Illuminated Greek Manuscripts. Vol. 1 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), pl. 17, fig. b.

The typology of this hall has been the subject of significant debate regarding terminological and morphological issues. The problem was first raised by Richard Krautheimer, who proposed that, around the year 800, Pope Leo III (r. 795–816) copied the Nineteen Couches in his eleven-apsed triclinium in the Lateran Palace. After comparing the ritual and the furniture, he concluded that the Nineteen Couches must have also had nineteen apses. To this day, authors such as Martin Luchterhandt, Kostenec, or Westbrook have supported this theory.Footnote 50 Others, like Simon Malmberg, Isabella Baldini-Lippolis, and Salvatore Cosentino, lean towards a strictly basilical solution, without lateral apses.Footnote 51

Regarding terminology, it is important to point out that the mention of akoubita and sigma-shaped tables does not imply the existence of apses, as can be seen in some trapezai (refectories) on Mount Athos, which follow the model established in the Great Lavra by St Athanasios in the tenth century. Moreover, not a single text mentions the presence of apses in the hall. In fact, Liudprand states that the name of the Nineteen Couches ‘did not emerge from the structure itself’.Footnote 52 In any case, the papal protocols cited by Krautheimer do not refer to the eleven-apsed basilica but rather another hall known as the Basilica Magna, which only had three apses. Consequently, the comparison is purely superficial.

To complete our morphological characterisation of the Nineteen Couches, it is also important to consider how it was connected to the Tribunal. As it was the largest hall in the palace, scholars have often placed it in a central position, presiding over the Tribunal, and have even associated it with the dikionion, thus displacing the Augousteus. However, the Nineteen Couches did not have a frontal access but rather a lateral one. The triklinos had only two entrances, one to the north and the other to the south, next to the imperial couch.Footnote 53 Given that the hall was adjacent to the circus and oriented in a north–south direction, the only feasible solution would be to place the doors on the eastern side. This configuration resembles strictly contemporary examples consisting of large basilicas laterally attached to porticoes, as in the Tetrarchic palaces of Sirmium, Milan, and, especially, Thessaloniki. The latter is an exact parallel to the present interpretation of the Nineteen Couches.Footnote 54 It also has nine recesses on each side, likely implying the presence of windows and, maybe, couches. This is a feature shared by the Constantinian basilica in Trier as well (Figure 8). This conclusion is of significant importance, as it not only assists in visualising the Nineteen Couches but could also contribute to a more accurate characterisation of the functions of these grand structures, which are often described as audience halls. Given their size and morphology, it is more likely that they were banquet halls, just like the Nineteen Couches in Constantinople (Figure 9).

Figure 8 The Basilica of Constantine in Trier, early fourth century.

Figure 9 The triklinos of the Nineteen Couches.

3.5 The Barracks of the Imperial Guard

As in most royal residences, in Constantinople barracks stretched between the private and ceremonial quarters and the main gate. The barracks consisted of a succession of porticoes, cubicles, and monuments, which not only served as living quarters for the soldiers but also housed various administrative offices. This area is broadly referred to as the Scholai, from the Latin schola, meaning a small room, in reference to the aforementioned cubicula.Footnote 55 The barracks were built by Constantine but burned down during the Nika Revolt and were later rebuilt by Justinian.Footnote 56

It has been mentioned that the triklinoi of the three corps of palatine troops were adjacent to the Tribunal. The hall of the kandidatoi was attached to the eastern portico of the court, serving as a connection with the eastern itinerary, while those of the exkoubitores and the scholarioi were adjacent to the northern portico. The first monument on the way to the gate, also adjacent to the northern side of the Tribunal, was the Dome of the Lamps or Heptakandelon. Its name derived from the ceremonial display featuring a menorah upon which the Mandylion of Edessa was hung.Footnote 57 This superimposition might have represented the fulfilment of the Old Testament promises through the incarnation of Christ.

One exited the Lamps through the Great Gate of the Exkoubitores, which led to the Curtains.Footnote 58 It is unclear whether this refers to an actual veil hanging above the gate or a portico adorned with drapes. Nearby stood a stable, as the emperor enjoyed the privilege to ride up to this place after crossing the Chalke.Footnote 59 After passing through the Curtains, one would reach the first Schola, presided over by the Rotunda of the Eight Columns. This building must have been ancient, as it was also known as the Old Mint.Footnote 60 Its form and alleged early date of construction suggest that it was likely a Constantinian structure, and thus might have resembled various Late Antique centralised typologies, such as the mausoleum of Diocletian and the treasury of the palace in Sirmium.Footnote 61

Although we know there should have been seven Scholai, one for each regiment, apart from the first, only the fifth is mentioned in the Book of Ceremonies.Footnote 62 Nearby stood the last significant monument before reaching the Palace Gate, the Church of the Holy Apostles, which may also have been the work of Constantine. Its dedication coincides with that of his mausoleum, and we know that the emperor took great care to ensure his bodyguards were Christians.Footnote 63

3.6 The Chalke Gate and Its Surroundings

Constantine constructed a vestibule for his palace, which he surmounted with a painting depicting the emperor and his sons slaying a serpent symbolising Licinius.Footnote 64 A visual representation of this propylaeum may be achieved by comparing it with the vestibule of Theodoric’s palace in Ravenna, as depicted in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo (Figure 3). This construction might have emulated the one in Constantinople and was also known as Chalke. However, the Constantinian gate was destroyed during a revolt in Anastasius’s reign (r. 491–518), around 495. He assumed the reconstruction of the edifice, but it was subsequently destroyed during the Nika riots of 532.Footnote 65 The ruins that we know today correspond to the final reconstruction undertaken by Justinian. Although it predates this period, it is from that moment onwards when its designation, Chalke, became popular. The term was used to describe either the grand bronze doors or the roof, made from the same material. In the Byzantine period, the gate led directly to the Mese, the main avenue of the city. This initial section of the street was known as the Regia and featured two-storey porticoes (Figure 10). At the far end stood the Milion, a triumphal arch in the shape of a tetrapylon (quadrifrons triumphal arch). This layout followed a typical scheme found in Late Antique urban palaces, as evidenced in Split or Antioch.Footnote 66

Figure 10 The Chalke Gate and its surroundings, including the Magnaura and the Church of the Saviour.

The ruins of the main gate of the palace lay under the remains of the Ottoman Palace of Justice, between the eastern boundary of Sultanahmet Square and the Four Seasons Hotel. After the fire that destroyed it, in 1933, Mamboury surveyed the area and labelled it as zone Aa.Footnote 67 Between 1997 and 2008, a Turkish team conducted extensive excavations east of Sultanahmet Square and Hagia Sophia. Successive campaigns uncovered the remains of the Gate, which Mango had placed in the same location fifty years earlier.Footnote 68

The excavations revealed a rectangular courtyard. The western enclosing wall, 2.5 m thick, was pierced by a large gate over 6 m wide. On either side of the gate, two thick pillars projecting from the wall indicated the presence of the vestibule. Flanking these pillars, the courtyard wall was adorned with niches and columns standing on marble steps. On the northern wall of the courtyard, a smaller vestibule was uncovered, opening onto a narrow passage. It had a rectangular plan and a two-arched entrance supported by a marble pillar. A small rectangular chapel was attached to the south wall.Footnote 69

The discovered ruins accurately match Procopius’s description: the Gate had the plan of an almost square rectangle. From each of the corners, a thick pillar ascended. The two eastern pillars projected from the enclosing wall, as it has been revealed in the course of excavations. Above, four arches spanned between each of the four pillars. The resulting space between the pillars and these arches was closed with four pendentives, upon which rose a dome. The decoration comprised polychrome marbles and mosaics, depicting the victories of Belisarius, contemplated by Justinian and Theodora, who, surrounded by the court, stood at the centre of the dome (Figure 11).Footnote 70 This architectural model corresponds to a typology widespread in the Late Antique Mediterranean, known as projecting porch. It was likely present in the vestibule erected in Cartagena by Comentiolus, Byzantine governor of Spain, and is well documented in the Islamic sphere with examples from the palaces of Amman and Khirbat al-Mafjar, in the Levant, and Ajdabiya, in Libya.

Figure 11 Interior of the Chalke Gate.

The remaining elements unearthed are also mentioned in the sources. The porticoed gallery flanking the vestibule was known as the peripatos. The northern, smaller porch was known as the Iron Gate, while the chapel to the south was likely the one erected by Romanus Lecapenus (r. 920–944) in honour of Christ the Saviour. In close proximity to this chapel, John Tzimisces (r. 969–976) constructed another, larger one, with the same dedication.Footnote 71 It featured two semi-domes and a large central dome, and was probably standing on a platform that gave the church additional height. Several representations of the structure exist, including Nasuh’s map of Istanbul, Reveley’s view of Hagia Sophia, and an engraving by Gugas Inciciyan (Figure 12). The building was demolished in 1804, and no remains have been discovered.Footnote 72

Figure 12 The Church of the Saviour in the 1790s, engraving by Gugas Inciciyan, from Eyice, ‘Arslanhane ve Çevresinin Arkeolojisi’, figure 4.

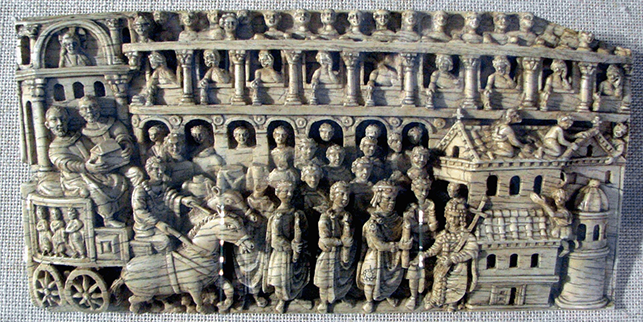

Being the main public façade of the palace, the Chalke became a showcase of imperial will. For instance, upon the declaration of war, weapons and shields were hung from the gate.Footnote 73 In this regard, the Chalke played a crucial role in demonstrating the emperors’ support for either the iconoclastic or orthodox faction. According to tradition, an icon of Christ had presided over the Chalke Gate since at least the reign of Maurice (r. 582–602). Leo III (r. 717–741) is said to have dismantled it to express his rejection of icons. Nowadays, it is widely acknowledged that this account is likely apocryphal. It is believed that Irene (r. 769–802) installed the mosaic of Christ above the gate for the first time. The icon was then dismantled by Leo V (r. 813–820), only to be definitively restored by Theodora (r. 830–856) in 843, marking the Triumph of Orthodoxy.Footnote 74 While its dating and attribution are controversial, the Trier ivory, depicting a translation of relics, likely portrays the Chalke Gate and the two-storied portico of the Regia around that time (Figure 13).Footnote 75

Figure 13 The Trier Ivory, mid ninth century. Treasury of the Cathedral.

Following the iconoclastic period, the Chalke Gate assumed additional roles, functioning as a court of justice and a prison.Footnote 76 Emperor Isaac II (r. 1185–1195) removed the bronze doors, but the vestibule survived the Byzantine Empire, albeit in a ruined state.Footnote 77 This is how we see it in various representations, such as the Nuremberg Chronicle and an engraving by Van Aelst.Footnote 78 The building may have been finally demolished in the first half of the seventeenth century, likely to salvage materials.Footnote 79

3.7 The Great Triklinos of the Magnaura

During the Middle Byzantine period, the Magnaura served as the primary audience hall of the palace. It also accommodated part of the imperial wedding ceremony, the emperors’ public addresses during Lent, a court of justice, and a government-sponsored school.Footnote 80 Despite its importance, it was situated outside the palace, adjoining the complex at its northern end. It was close to Hagia Sophia, approximately parallel to the Augoustaion square, which gave its name to one of the gates leading out of the Magnaura complex.Footnote 81 The hall itself stood on a semicircular terrace constructed in the early seventh century, together with a commemorative column and an armoury.Footnote 82 The monumental complex was completed during the reign of Heraclius.Footnote 83 The curvature of this terrace can still be discerned along the İshak Paşa Cd. ramp as it ascends towards Hagia Sophia. Some archaeological remains may be associated with the relative position of the Magnaura. Of particular note is a basement dating back to the sixth century, which was later embellished with frescoes in the 8th and 9th centuries.Footnote 84 Also noteworthy is the presence of a cistern that, according to written sources, might have been the same that provided delicious fish for the emperor’s table.Footnote 85

The Patria state that the hall’s name originated from the cry uttered by the elderly Emperor Anastasius upon his death, as he was caught in a thunderstorm: ‘O mother (mana), I perish by the breeze (aura) [of fire]’.Footnote 86 However, it is merely an adaptation of the Latin Magna Aula. Although the construction of the Magnaura is traditionally attributed to Constantine, it achieved its greatest renown during the 9th and 10th centuries, when it hosted memorable state receptions for foreign ambassadors.Footnote 87

The location and date of the complex have stirred controversy regarding its possible identification with the Senate of the Augoustaion, reconstructed by Justinian following the Nika riots, as proposed by Mango (Figure 10).Footnote 88 Other scholars, such as Rudolf Stichel, posit that the Curia and the Magnaura were distinct buildings.Footnote 89 The argument put forth by this author is based on the presence of monumental columns in the Augoustaion, which are purported to match those described by Procopius as adorning the Senate’s porch. Nevertheless, it is known that a considerable number of commemorative columns stood in the Augoustaion.Footnote 90 Furthermore, the Senate did not directly open onto it; instead, it was situated on the other side of the street or square running east of the Augoustaion, the Pittakia, whose main feature was the column of Eudoxia.Footnote 91 The base of this monument was discovered to the southeast of Hagia Sophia and can be seen today in the garden of the Great Church. Aside from its location, the most compelling evidence supporting the identification of Senate and Magnaura arises from the correspondence between the morphology described in independent historical sources and the Book of Ceremonies.

Describing the hall’s morphology is a complex task. While traditional views support a three-aisled basilica, Berger, for instance, has proposed the possibility of a central dome.Footnote 92 According to the sources, the complex consisted of two elements: the triklinos itself and a porticoed courtyard planted with trees known as anadendradion. The Magnaura had a conch at the eastern end, beneath which the emperor’s throne was placed. The presence of a conch is also highlighted in the accounts describing the Senate of the Augoustaion.Footnote 93 The throne was the most characteristic element of the hall and was designed to emulate the throne of King Solomon, from which it took its name. It was situated behind a railing, above a flight of steps, and flanked by automata shaped like lions. These figures could stand, roar, and move their tails. A tree of gold with singing birds stood above the ensemble, and a mechanism allowed the enthroned emperor to ascend to the ceiling of the hall. The entire spectacle would unfold as the thunderous organs filled the air.Footnote 94 Regarding the hall itself, we only know that it had a rectangular floor plan, as evidenced by the fact that two rows of seven lamps were hung there during receptions, indicating two short sides to the east and west, and two long sides to the north and south.Footnote 95 A bedchamber was adjacent to the building.Footnote 96

The façade of the Magnaura was notable for its porch, which, according to the Book of Ceremonies, consisted of four large columns and a great arch.Footnote 97 This is consistent with Procopius’s description of the Senate’s porch, which comprised two pilasters adjacent to the wall and four immense columns of white marble supporting a vault.Footnote 98 Under this arch, a green marble omphalion (circular marble plaque) marked the emperor’s position during ceremonies.Footnote 99 From there, a monumental flight of stairs led to the garden. Courtiers, bodyguards, and leaders of the circus factions would be arranged on these steps in hierarchical order, flanking the emperor, who stood on the highest step. The courtyard had two porticoes, and a row of trees, the actual anadendradion (garden), which was decorated with chains, silks, precious objects, and lamps, as if they were colonnades. The northern portico was adjacent to the empress’s stable, while the southern one led to the palace through a bridge. The western end of the courtyard opened to the public thoroughfare by the aforementioned Gate of the Augoustaion.Footnote 100 This side was closed off by the anabasion, a raised passage built by Justinian, which allowed access from the palace to the Great Church. The anabasion started at the Iron Gate of the Chalke, in a place called Chytos, and led to the southeastern gallery of Hagia Sophia, through a door that now opens to the void.Footnote 101 A portion of this passage can be observed in the engraving of the Nuremberg Chronicle and in Matrakçı Nasuh’s map of Istanbul.Footnote 102

During excavations in the vicinity of the Chalke Gate, a polygonal apse was uncovered in an area corresponding to the space between the Magnaura and the Augoustaion. This structure plausibly aligns with the Chapel of the Varangians, also known as the Chapel of the Patricians. According to Byzantine sources, it was located behind Hagia Sophia, between the Chalke Gate and the Chapel of the Holy Well, exactly where the apse was found.Footnote 103

3.8 The Eastern Itinerary: The Galleries of Eros and the Triklinos of the Ovaton

As mentioned in the introduction, the entire eastern flank of the palace is lined with the remains of galleries running north–south:

(a) The first ensemble of relevance consists of a thick wall made of stone ashlar, which must have formed the southern end of the Magnaura’s terrace. This wall bordered a street 40 m long and 4 m wide. The Mamboury Ac2 group was situated directly south of the street, already within the palace proper. It comprised a terrace formed by a network of chambers separated by brick cruciform pillars. Further south, the Mamboury Ab group marks the actual beginning of the galleries heading southward.Footnote 104

(b) These galleries extended to the Mamboury B complex, whose main feature is the Ramp House (Ba), a kochlias or three-storey spiral staircase divided into nine sections, which gave access to one of the upper terraces of the palace, at 26 m.a.s.l (Figure 14). A small apse on the upper level suggests the presence of a chapel. A few metres northwest of the ramp, the foundations of a grand polygonal apse (Bc) were documented, surrounded by galleries (Bb) and cisterns (Bd). Further south, a series of passages led to a fountain (Bg). Near this source, the remains of a ramp similar to Ba were also documented, but practically destroyed (Be). From here, after creating a recess, the galleries proceeded southward until reaching the next significant complex, Mamboury D.Footnote 105

Figure 14 The Ramp House in Akbiyik Cd.

The itinerary corresponding to these remains is designated by the Book of Ceremonies as the passageways leading to the Hall of Eros, one of the southernmost chambers of the Upper Palace.Footnote 106 This route is fairly well documented, especially thanks to the bridal ritual, which allows for many identifications. Firstly, it must be noted that a street separated the area ascribed to the Magnaura terrace and the palace proper. We know that to transition between the two, one had to cross a bridge located south of the great triklinos. This would have served to cross over the 40 m long street found to the north of the Mamboury Ac2 group.Footnote 107 Kostenec suggested that the Ramp House (Ba) matched the staircase of St Christina, down which empresses descended to take a bath three days after their wedding night.Footnote 108 This assumption is supported by several lines of evidence. Firstly, the staircase is the first in the galleries leading outside the palace. Secondly, the ramp is associated with the apse of an important building, and we know that the staircase of St Christina was associated with the triklinos of the Ovaton. Finally, the itineraries suggest that this complex was located at an intermediate point along the eastern route, and the ruins effectively occupy a central position within the route of the galleries running from the Magnaura to the southern end of the Upper Palace (Figure 15).

Figure 15 View of the Ovaton and the Mamboury B complex.

Following this reasoning, the polygonal apse (Bc) would correspond to the triklinos of the Ovaton. We know that in order to reach the staircase of St Christina, it was necessary to pass ‘at the side of the Ovaton’, and then ‘behind the Ovaton’, which aligns with the position of the apse, the adjacent galleries, and the ramp.Footnote 109 This hall, also known as the triklinos of the Dome or Troullos, was given its name due to its connection with the archive of the treasury, which, in accordance with the tradition of skeuophylakia (treasuries) had a centralised plan and was topped by a dome.Footnote 110 The building is attributed to either Constantine or Anastasius.Footnote 111 The triklinos of the Ovaton was primarily known for hosting the Sixth (680–681) and Quinisext (696) councils, after which they were known as Trullan Councils.Footnote 112 The building was still in use in the late twelfth century, as the wedding of Alexius II (r. 1180–1183) and Agnes of France (1180) was celebrated there.Footnote 113

3.9 The Peristyle of the Mosaics and the Consistorium

3.9.1 Archaeological Remains

Mamboury Da emerges from the slope at the southern end of the B structures, representing the southeastern corner of a recess formed by the galleries. This indicates that the galleries continued further southward. Two additional ensembles were documented to the southwest of these remains. Db, dated to the sixth century, was a cruciform chamber with a groined vault, featuring four small rectangular spaces between the arms of the cross. This was preceded to the west by an antechamber, built with earlier materials, possibly from the fifth century. Mamboury Dc, comprising several cisterns, was discovered 20 m to the south of the aforementioned structure.Footnote 114

Since the beginning of the century, the Scottish magnate Sir David Russell and his spiritualist friend, Wellesley Tudor Pole, had been contemplating the possibility of excavating in the area, following a revelation during séances conducted by Russian monks exiled from the Revolution.Footnote 115 At last, in 1935, the excavation began under the direction of James Houston Baxter, a professor of church history at the University of Glasgow. Works revealed a peristyle paved with a magnificent mosaic displaying hunting scenes and the remains of a cruciform church. After the Second World War, in 1952, Sir David Talbot Rice led a second campaign, which unearthed the Apsed Hall overlooking the courtyard.

The peristyle boasted monumental dimensions of 65 × 55.5 m, while the hall measured 32 × 16.5 m. The Mamboury Db complex was adjacent to the hall on its northern side, while the cisterns in Dc were adjacent to it on the southern side. A street and a sequence of galleries divided this primary ensemble from a secondary one located north of the peristyle, notable for the remains of a cruciform church. A passageway ran along the western end of the peristyle, while an elongated hall was attached to the southern outer wall. The peristyle was situated above the southeastern edge of the terraces of the Upper Palace, with the piano nobile (main floor) at approximately 26 m.a.s.l. This meant that the earth beneath the site had been disturbed and originated from elsewhere, complicating the dating process. Nevertheless, it was determined that the filling must have occurred between 500 and 540.Footnote 116

One of the earliest elements of the ensemble was the Paved Way, a two-level brick viaduct that ran through the centre of the courtyard in an east–west direction, deviating slightly from its axis. The surface was paved with marble slabs. It is important to note that the viaduct always terminated in front of the foundations of the hall, suggesting that a significant building may have already stood at the eastern end of the courtyard in the earliest phases of the complex.Footnote 117 A fundamental structure for the study of the peristyle, and the next one in chronological order, is a cistern located beneath the southern portico. The structure was clearly older than this portico, as it was crossed by the latter’s foundations. The bricks used in the construction of the structure bore stamps typical of the sixth century, featuring two lines of text or a cruciform shape, signed by a certain Gaius.Footnote 118

The subsequent phase of construction pertains to the peristyle and the hall. The peristyle comprised four porticoed galleries. The initial entry to the complex was located at the northwestern extremity of the peristyle (Figure 16). The northern portico, aligned with the entrance, featured recesses with built-in marble benches. In the 1980s and 1990s, an Austrian team resumed excavations at the site. Works uncovered evidence suggesting that, despite sharing the same plan, two successive peristyles must have existed on the site. The first peristyle may have been decorated with a bichrome mosaic floor in black and white, while the second and final peristyle was embellished with the magnificent hunting-themed mosaics (Figures 20–23). The pottery discovered in the layer of debris between the two floors provided a terminus post quem for the mosaic peristyle, indicating that it was constructed after the year 475.Footnote 119 The hall also stood upon earlier buildings, as evidenced by a complex network of infrastructures with successive phases. Its foundations revealed that the structure was divided into an antechamber by a thick wall pierced by three arches. This vestibule led to the actual hall through three doors corresponding to the inferior arches. The presence of pillars under the apse indicated that the floor level in this area was higher than that of the rest of the chamber.Footnote 120

Figure 16 The northern portico of the peristyle of the mosaics in the late sixth century.

The mosaic remained exposed for an extended period, resulting in damage that required repairs. The broken sections were subsequently filled in with opus signinum (Roman waterproof mortar). Later, the complex underwent significant transformations. The north and south porticoes were walled, and repurposed into long galleries, while the western one was eliminated. The mosaic was meticulously protected by the application of marble slabs, which ultimately ensured its preservation. The Paved Way regained its central position when a new main door was opened at the western end of the courtyard, aligned with the viaduct. The final intervention involved the walling of the recesses with benches in the northern portico. At some point in the late twelfth century, the site was subjected to extensive damage, as evidenced by the discovery of weaponry and armour in a context suggestive of violence and fire (Figure 17).Footnote 121

Figure 17 The peristyle of the mosaics before and after the reform that removed the porticoes.

3.9.2 Previous Datings and Identifications of the Site

Paradoxically, the discovery of the mosaic has presented a challenge in determining the date of the site, as numerous approaches have favoured the stylistic examination of the pavement over a strictly archaeological and topographic point of view. In this context, the narrative surrounding the date of the mosaic reflects the broader perception of Late Roman and Byzantine art. The assumption was that the more ‘Classical’ or ‘Hellenistic’ the features of an iconography, the earlier its date, and vice versa. Considerations such as the coexistence of diverse levels of artistic quality, disparities between centre and periphery, and the persistence of prestigious models in specific contexts, like the court, were overlooked.

For instance, in the initial excavation report, the analysis of hairstyles and clothing led researchers to propose a date around the year 410, despite this being at odds with the archaeological evidence. In any case, all such dating was based on the erroneous presumption that the site was the terrace of the Pharos.Footnote 122 The sixth century was only considered after stylistic comparisons were established with Syrian mosaics.Footnote 123 While Talbot Rice placed a greater emphasis on archaeology, he still relied heavily on stylistic labels such as ‘Medieval’, ‘Classical’, ‘Hellenistic’ or even ‘neo-Attic’ to suggest a date between 450 and 500. This was the case even when the author explicitly suggested that the work was executed later.Footnote 124

Victor Lazarev proposed a date in the mid sixth century, after comparing the mosaic with silver plates from the reigns of Justinian and his successors.Footnote 125 Following initial reservations, Mango and Irving Lavin also unequivocally pointed to the sixth century.Footnote 126 Some years later, Per J. Nordhagen sparked a new trend, suggesting a later date for the mosaic. According to him, the mosaic’s style would reflect a revival imitating the sixth century, believed to have been introduced by Justinian II (r. 685–695 and 705–711) around the year 700. Accordingly, the hall would be identified with the triklinos of Justinian II.Footnote 127 The proposal was so successful that some authors even spoke of a ‘Justinian II style’.Footnote 128

Although stylistic analysis has never been entirely abandoned, the 1970s saw the emergence of some criticism based on iconography and archaeology. For example, John W. Hayes studied the pottery, establishing a temporal framework for the creation of the mosaic, which he dated between 520 and 540.Footnote 129 Anthony Cutler showed that the mosaic incorporated models from different periods and geographical contexts, invalidating the stylistic dating hypothesis.Footnote 130 Gisela Hellenkemper-Salies undertook a significant reassessment of both the archaeological data and the mosaic’s style, which led her to conclude that works were likely completed around 475. Nevertheless, her arguments have since been superseded, and the value of her work is essentially bibliographic.Footnote 131 During this time, Salvador Miranda, a Mexican architect, concluded that, in topographical terms, the peristyle should be identified with the triklinos Augousteus.Footnote 132

James Trilling’s approach stands as the most comprehensive contribution to the mosaic’s style, which he links to North African examples. Nonetheless, his article draws heavily on an iconological reading, as he implies that the depictions of violence mirror emperor Heraclius’s troubled soul.Footnote 133 Chuck Morss’s readings focus on a purely stylistic analysis, demonstrating a clear link between the mosaic and Syrian and the Levantine examples dated to the mid sixth century.Footnote 134

It has been previously noted that Austrian archaeologists dated the mosaic after 475. Furthermore, they expressed a preference for attributing it to Justinian.Footnote 135 Subsequently, several proposals have been put forward. Bolognesi suggested that we are dealing with a structure known as the Apsis, related to the Triconch complex built by Theophilus (r. 829–842).Footnote 136 This interpretation, but from an iconographic perspective, has been adapted by Gianclaudio Macchiarella, who dated the mosaic to the ninth century.Footnote 137 Kostenec, espousing Trilling’s arguments, proposed that the ensemble was constructed by Heraclius to host the performances of the circus factions, and was subsequently transformed by Theophilus into a warehouse known as the Karianos.Footnote 138 Featherstone has suggested that we may be dealing with another of Theophilus’s constructions, the Margarites.Footnote 139

The interpretation that merits the most consideration, given its foundation on archaeological evidence, is that of Bardill. In accordance with Miranda’s perspective, Bardill postulated that the Apsed Hall is the Augousteus. Despite it being a Constantinian building, the mosaic and the main structures should be dated to around the year 600.Footnote 140 He postulated that the Paved Way had two phases, the lower one corresponding to the 4th or 5th centuries, and the upper one to the sixth century, based on the different size of the bricks found in each of the arcades. With regard to the cistern beneath the southern portico, he demonstrated that it could be dated after 518 or 533, when the use of cruciform monograms was introduced. After considering the size of the bricks, the use of the dative case, and the presence of cruciform monograms, he believed that the cistern was built at the end of the sixth century, further delaying the date of the whole complex built above it at least to the early seventh century. However, he admitted that the ceramic materials present in the earth fill and beneath the porticoes do not preclude a date as early as the year 500. After coins of Justinian, Phocas (r. 602–610), and Constantine IV (r. 668–685) were found upon the removal of the western portico, he suggested a terminus post quem for the reform of the marble pavement around the year 700. When analysing the Apsed Hall, Bardill argued that he could only identify phases dating back to the beginning of the sixth century at the earliest. While he acknowledged a succession of constructive phases and reinforcements, the main phase should be dated around the year 600. Bardill’s assessment was particularly influenced by the size of the materials and a stamp found on a brick utilised during a reinforcement phase, which is securely dated to either the years 583/584 or 598/599, corresponding to the reign of Maurice.Footnote 141

3.9.3 Chronological Analysis of Stamped Bricks

The initial certainty that must be considered before dating the peristyle is that the earth fill took place, according to Bardill, as early as around the year 500. However, as demonstrated by Hayes, it is unlikely that it occurred later than the year 540. Prior to the final fill, the upper arcade of the Paved Way may have been exposed, forming a raised walkway. This interpretation, rather than the two proposed constructive phases, would explain the observed difference in brick sizes. The height of this pre-existing walkway would have determined the level at which the peristyle was constructed.

Bardill proposed that the cistern under the southern portico was built in the late sixth century. However, this is not likely if we consider that the cistern preceded the earth fill, which has a terminal date of 540. He based his dating on the size of the bricks, the cruciform stamps, and the presence of the dative case. Though it is accurate to state that the bricks decrease in size over the course of the sixth century, Bardill himself admitted that there is a significant deviation in the measurements and that these cannot be employed as an absolute criterion for dating.Footnote 142 He also acknowledged that the size may vary depending on the function and size of the building, as he pointed out when studying the fifth-century baths located near the Kalenderhane Mosque.Footnote 143 However, the cistern was undoubtedly constructed after 518 or 533, as evidenced by the presence of the cruciform monogram. Although most stamps on the bricks appear in the genitive case, the dative case is not a solid argument for supporting a later date either. Concerning the bricks stamped by Gaius (1364.1a and 1365.1a), Bardill’s own classification places similar examples in constructions dating to the first half of the sixth century, such as St Polyeuctus, Hagia Sophia, Hagia Eirene, the Basilica Cistern, and the ruins of the Hospice of Sampson.Footnote 144 Consequently, it can be inferred that the cistern was constructed between the years 518 or 533, when the cruciform monograms first appear, and the 540s, as inferred from the earth fill.

An analysis of the bricks found in the peristyle yields similar conclusions. Bardill types 666, 785.1 c, 880.1a, 1257.1a, 1342.3b, 1342.8a, and 1344.1 c were notably prevalent in the walls of the peristyle and several drainage conduits. These types were also found in the cross-shaped church to the north, as well as in sixth-century contexts such as Mamboury A, B, and C. Outside the palace, this type is also found in St Polyeuctus, the reconstruction of Zeuxippos, Hagia Sophia, Hagia Eirene, repairs to the Balaban Ağa Mosque dating to the sixth century, and the north church of the Kalenderhane complex from the mid sixth century. During the renovation of the marble floor, stamps 619.1a and 620.1a were repurposed in a conduit. The same stamps were also found beneath the hall and in the southern cistern. This stamp features the abbreviation ‘skri-’, which may refer to the rank of skriniarios or skribon. If it refers to the latter, the brick must be dated after 545, when this position was first recorded.Footnote 145 Similar examples can be found in Zeuxippos, in interventions undertaken in the palace of Antiochus during the sixth century, and again in Kalenderhane, with a similar date.

Beneath the remnants of the western portico, a coin of Justinian was discovered. Initially, it was thought that this suggested the emperor’s involvement in covering the mosaic, a view partially shared by Bardill, who proposed that the coin was deposited during this phase.Footnote 146 However, considering the chronology of the bricks and the stratum, which coincided with the boundary between the Late Roman level and subsequent renovations, it is more probable that the coin was deposited during the construction of the peristyle.Footnote 147

Regarding the infrastructures of the hall, Bardill admitted that a significant building already stood there by the year 500, as evidenced by repairs dated to the early sixth century.Footnote 148 It can be reasonably assumed that the Paved Way led to that building. Two significant groups of stamped bricks were unearthed below the hall. The first, dating to the early sixth century, was believed by Bardill to be the result of a massive reuse of building materials. Conversely, the group contemporary to the construction of the hall would be later, dating to the end of the century. In this group, nine out of ten stamps were of the ‘skri-’ type.Footnote 149 Another significant brick bore a stamp dated to 583/584 or 598/599, during the reign of Maurice (231.1b). This brick might be the main reason behind Bardill’s dating of the complex to the late sixth century. However, only one specimen was discovered, detached from one of the vaults, which suggests that it originated from a restoration. This view would be further reinforced if the brick was promptly placed in 583/584, as a violent earthquake occurred that year.Footnote 150

In conclusion, in the fifth century there was already a significant complex standing in the location of the peristyle, judging by the Paved Way and the infrastructures of the Apsed Hall. The analysis of stamps from the peristyle and the hall suggests that the main constructive phase took place in the mid sixth century, as it is also inferred from the terminus ante quem of the earth fill around 540 and the apparition of the ‘skri-’-type stamps, probably dated from 545 onwards. This chronology aligns with the finding of Justinian’s coin and the dating of the bricks. It can thus be reasonably concluded that the primary construction phase of the complex occurred during the latter half of this emperor’s reign.

3.9.4 The Consistorium and the Church of the Lord

It is this author’s opinion that the archaeological site should be identified with the Consistorium. To support this identification, it is essential to elaborate on the features of the building. The Consistorium was the main audience hall of the palace in Late Antiquity, where courtiers conducted the adoratio or proskynesis (prostration or obeisance) and foreign ambassadors were received by the emperor. It was also the place where he dictated laws before his council, the consistory, which gave its name to the building.Footnote 151 The hall is first documented as early as 467, when an embassy from the Western Emperor Anthemius (r. 467–472) was received there. It also played an important role during the proclamation of Leo I (r. 457–474), Anastasius, and Justin I (r. 518–527).Footnote 152 Despite its early importance, the Consistorium holds a marginal position in the Book of Ceremonies, as by the tenth century it had been replaced by the Magnaura and the Chrysotriklinos. Even its name was forgotten, becoming known as ‘the hall where the baldachin stands and where the magistroi are appointed’.Footnote 153

The position of the Consistorium and its connections with other elements of the complex can be reasonably ascertained through its neighbouring structures. It was the last significant hall along the eastern route. The Church of the Lord was situated north of the building, the triklinos of the kandidatoi standing exactly opposite the chapel. As previously stated, the latter was adjacent to the eastern side of the Tribunal.Footnote 154 This position rendered the site a crucial junction where the eastern and western itineraries converged. The Consistorium was also near the ancient baths and not far from the Covered Hippodrome. However, the connection with these structures ended following the construction of the Triconch.Footnote 155 In any case, these clarifications are crucial, as they reinstate the position of the Consistorium at the southernmost edge of the Upper Palace. On the other hand, the position of the Church of the Lord roughly corresponds to the cruciform church to the north.

The Consistorium was preceded by the Onopodion, an area of uncertain nature. Here, courtiers, coming from the Gold Hand, would customarily greet the emperor before proceeding into the hall. Our knowledge of the Onopodion is limited to the fact that access was gained through a bronze door covered with a veil that led onto a marble floor. This door was located exactly in front of the Consistorium. Additionally, a triple door of the Onopodion is referenced.Footnote 156 Scholars such as Berger and Kostenec speculated that this space likely took on a horseshoe shape, given its name, meaning donkey hoof.Footnote 157 Guilland, however, proposed that it might have been a gallery wide enough for a donkey to pass through.Footnote 158 Prior to entering the Consistorium, another enigmatic chamber, known as the Indians, is referenced.Footnote 159

In the sixth century the Consistorium was preceded by a space or antechamber known as the Anticonsistorium.Footnote 160 From here, one accessed the hall known as the Grand Consistorium, through three ivory doors that were usually covered with veils.Footnote 161 The Consistorium featured a floor adorned with porphyry omphalia, indicating the position where ambassadors were to kneel before the emperor. At the far end of the chamber, above three porphyry steps, stood the baldachin of the imperial throne.Footnote 162 The Grand or Summer Consistorium was adjacent to the Small or Winter Consistorium, where courtiers would often dress following their promotions.Footnote 163

The hall’s most distinctive feature was the baldachin (Figure 18). Corippus, who chronicled an embassy during the reign of Justin II (r. 565–578), described it as a structure supported by four columns and topped with a hemispherical dome that symbolised the vault of Heaven. Each corner was surmounted by the figure of a winged victory, bearing a laurel wreath. The entire structure was crafted from gold and adorned with precious stones and purple silks.Footnote 164 Several accurate representations of the artefact have come down to us: in the two ivories featuring Ariadne, the empress is depicted beneath the baldachin. Four centuries later, during Basil I’s reign (r. 867–886), it is found again in a manuscript of the homilies of St Gregory (fol. 239 r) (Figure 19). The only difference from Corippus’s description is the replacement of victories with eagles holding wreaths.

Figure 18 Interior of the Apsed Hall interpreted as the Consistorium.

Figure 19 The baldachin of the Consistorium in the Homilies of St. Gregory, 2nd half of the ninth century. Paris, BNF, Par. gr. 510, fol. 239 r.

The location of the Church of the Lord has already been outlined. However, it is worth noting that it was also identified as one of the main entrances to the palace, in this case, on its eastern flank.Footnote 165 According to the Patria, Constantine was the builder of the church.Footnote 166 The only information available regarding the structure is that it possessed bronze doors, a narthex, and a sanctuary.Footnote 167 The interior of the church was used to store the insignia of high-ranking members of the hierarchy, including the Caesar, as well as the labara (military pennants, often decorated with a Chi-Rho) and dragon standards of the guards.Footnote 168

3.9.5 Identifying the Peristyle (I): Topographical Analysis

The site’s immediate characteristics, including the triclinium-peristyle layout and the scale of the complex, indicate that we are facing one of the main triklinoi of the Upper Palace, that is, the Augousteus, the Nineteen Couches, the Hall of Justinian II, or the Consistorium. As previously stated, Miranda and Bardill already suggested the Augousteus. However, the identification does not seem feasible: its location does not correspond with the site, and its orientation probably does not either. Some recognisable annexes, such as the Octagon, are absent, and the chronology of materials does not correspond to the Constantinian period. Nordhagen opted to identify the complex with the triklinos of Justinian II. The location appears more suitable, as this hall abutted the southern terraces. Nevertheless, it did so from the western side, not far from the curved end of the Hippodrome. Moreover, the construction of the building occurred around the year 700, when the peristyle had already been in existence for at least a century. The Nineteen Couches can be dismissed with minimal consideration, as it had a north–south orientation and was adjacent to the Hippodrome. In contrast, the Consistorium shares several features with the complex. Firstly, topographic coincidences will be listed:

(a) North of the Consistorium stood the Church of the Lord, which also served as an eastern entrance to the palace. To the north of the peristyle, the remains of a church were discovered, situated near the recess between groups Mamboury B and D. Given the upward slope of the area, it is possible that this structure was linked to the aforementioned access to the imperial residence.

(b) The Consistorium was situated on the eastern flank of the Upper Palace, like the excavated structures.

(c) Prior to the construction of the Triconch, the Consistorium was positioned opposite the Covered Hippodrome and the baths, at the southernmost point of the upper terraces, much like the peristyle complex.

(d) The Book of Ceremonies places important elements to the north and west of the Consistorium, namely the Church of the Lord and the Onopodion. However, nothing is mentioned east or south. This leads to the conclusion that, similarly to the peristyle, the Consistorium was situated at the southeastern corner of the Upper Palace.

The morphology of the site and that of the Consistorium also exhibit significant parallels:

(a) In the sixth century, the Consistorium was preceded by the Anticonsistorium, where ambassadors sat while waiting to be granted entrance to the hall. Marble benches were discovered in the northern portico of the peristyle, aligned with the entrance to the courtyard.

(b) The Consistorium was accessed through three ivory doors. Their material suggests that they did not open directly to the outside but rather to an antechamber. Entrance to the main room of the apsidal hall was via a vestibule and three doors, as evidenced by the infrastructure.

(c) The Consistorium had a smaller adjoining chamber known as the Winter Consistorium, and the Apsed Hall had a northern extension labelled Mamboury Db.

(d) In the Consistorium, the throne stood upon a dais with three porphyry steps. In the hall, the area of the apse was raised above the rest of the chamber.