Management Implications

This study has implications for the restoration of sites invaded by Ailanthus altissima (tree of heaven). Sites that have had A. altissima wood left behind either after chemical treatments, death due to disease, or damage due to windthrow or other disturbances may be subject to legacy effects of the release of allelopathic compounds from the decomposing wood. Forests with A. altissima trees that are planned for chemical treatment or suffering from Verticillium nonalfalfae (Verticillium wilt) are relatively common in its invasive range, including North America and Europe. The results of this study show that A. altissima wood left behind for at least 18 mo will likely negatively affect restoration efforts that require seeding or planting. There is no impact to plants germinating directly from the soil seedbank, but many eastern forest seedbanks are depauperate due to invasion by exotic plants, excessive deer (Odocoileus virginianus) herbivory, and poor silvicultural management. This study also reveals that A. altissima mulch that has been left outside for at least 2 yr (26 mo) may have added value for active restoration, improving the germination and growth of some native plantings or seedings. Finally, this study shows that the use of garden fabric over an extended period to kill invasive plants and their seeds could have similar negative effects on native plant restoration as allelopathic compounds. Removal of A. altissima coarse woody debris left behind after control efforts or disease may help ensure successful restoration of a site, especially if native seeding or planting is planned. Further research is needed to determine the duration of the A. altissima’s legacy effect on soils due to allelopathy and whether the impact varies with other disturbance and physiographic factors, such as harvesting or fire history, soil type, and topography.

Introduction

Several invasive plants are capable of fundamentally altering ecosystem properties (Corbin and D’Antonio Reference Corbin and D’Antonio2012), and exuding allelopathic compounds is one mechanism shared by some of these drivers of environmental change (Morgan and Overholdt Reference Morgan and Overholt2005; Murrell et al. Reference Murrell, Gerber, Krebs, Parepa, Schaffner and Bossdorf2011; Parepa et al. Reference Parepa, Schaffner and Bossdorf2012; Prati and Bossdorf Reference Prati and Bossdorf2004). Allelopathic compounds produced by invasive plants may have remnant negative effects on site restoration after removal of the invasive plants (Grove et al. Reference Grove, Haubensak and Parker2012). Allelopathic effects tend to (1) be more potent against phylogenetically distant plants, (2) dissipate over time, and (3) impact native species more than associated non-native species (Small et al. Reference Small, White and Hargbol2010; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Liu, Yuan, Weber and van Kleunen2021).

Removal of invasive plant litter, stems, and boles known to be allelopathic could potentially improve tree regeneration and restoration efforts (Huo et al. Reference Huo, Wang, Bing, Li, Kang, Yang, Wei and Chao2019). Negative allelopathic effects of litter can last at least a year for some allelopathic species, such as Australian blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon R. Br.), southern blue gum (Eucalyptus globulus Labill.), and Monterey pine (Pinus radiata D. Don), depending on soil type (Souto et al. Reference Souto, Gonzales and Reigosa1994). Likewise, mulch from some allelopathic plants, such as black walnut (Juglans nigra L.) has been used as a chemical weed control (Saha et al. Reference Saha, Marble and Pearson2018), but allelopathic effects could potentially dissipate over time (Duryea et al. Reference Duryea, English and Hermansen1999).

Tree of heaven [Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle] is a non-native, allelopathic, invasive deciduous tree, originating from China, Taiwan, and north Vietnam (Kowarik and Säumel Reference Kowarik and Säumel2007). Its first record of introduction to the United States was in 1784 in Philadelphia, PA. Ailanthus altissima is found in a wide range of climatic conditions (Miller Reference Miller1990), elevations (Feret Reference Feret1985), and land types from open urban areas to closed-canopy forests (Hamerlynck Reference Hamerlynck2001; Hu Reference Hu1979; Knapp and Canham Reference Knapp and Canham2000). In North America, A. altissima’s eastern range extends from Vermont and the southernmost part of Ontario to as far south as Georgia. Centrally it extends as far north as Wisconsin to as far south as southern Texas. Its distribution also extends as far west as southern British Columbia to southern California. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), the Global Invasive Species Database (GISD), and eFloraMEX show A. altissima as naturalized in Mexico, but lack detailed location information (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Gaertner, Robertson and Richardson2017). Ailanthus altissima’s invasive range also includes parts of Africa, Europe, and South America (Hu Reference Hu1979). This dioecious species grows and reproduces both vegetatively and sexually in rich and impoverished soils and under other stressful conditions (Marshall and Furnier Reference Marshall and Furnier1981; Pan and Bassuk Reference Pan and Bassuk1986). Although relatively short-lived, A. altissima can reach sizes similar to many native trees in a short time and trees older than 100 yr are not unusual (Wickert et al. Reference Wickert, O’Neal, Davis and Kasson2017), with some in Europe documented to be 130 yr (Lauche Reference Lauche1936).

Ailanthus altissima has documented allelopathic compounds (Heisey Reference Heisey1990a, Reference Heisey1990b, Reference Heisey1996). These compounds may be released from its leaves, stems, and roots and may impact the germination and growth of associated plants, although longer exposure time to or association with A. altissima may decrease severity of impact from the allelopathic compounds (Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Colwell and Sexton1991). Lawrence et al. (Reference Lawrence, Colwell and Sexton1991) found allelopathic compounds in young stems of A. altissima, and Heisey (Reference Heisey1990b) found such compounds to be highest in the bark of roots and stems, intermediate in leaves, and lowest in the wood. Allelopathic compounds in decomposing plant parts may leach to the soil, resulting in legacy effects, although the life span of leached allelochemicals likely varies with soil pH and microbes. Ailanthus altissima’s allelopathic compounds, ailanthone and quassin, break down in alkaline soils (pH = 10), whereas they do not in acidic or sterile soils, suggesting a microbial mechanism behind the loss of allelopathic compounds (Sasnow Reference Sasnow2014).

Forest management in stands with or near A. altissima populations often includes locally eradicating it, especially if the forest prescription is to open the canopy (Huebner et al. Reference Huebner, Regula and McGill2018; Radtke et al. Reference Radtke, Ambraß, Zerbe, Tonon, Fontana and Ammer2013). Large A. altissima trees in both natural and urban areas can be effectively killed using stem injection with a herbicide or applying herbicide to a cut stump, with greatest impact in the fall (Meloche and Murphy Reference Meloche and Murphy2006). Killing A. altissima trees with herbicide may result in many remnant large stems either immediately after the cut or after the dead trees fall. In addition to the stems, the slash is often left behind to inhibit establishment of A. altissima seedlings, sprouts, and suckers or deter deer (Odocoileus virginianus) (Kota and Bartos Reference Kota and Bartos2010; Puettmann et al. Reference Puettmann, Cole and Newton2024).

Because A. altissima is spotted lantern fly’s (Lycorma delicatula) preferred host, there may be an increase in A. altissima mortality associated with the spread of this destructive, invasive insect (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Kuhn, Raupp and Martinson2023). Similarly, stands impacted by Verticillium wilt (Verticillium nonalfalfae) are often littered with large, fallen, dead A. altissima trees (personal observation). Verticillium nonalfalfae is a fungus that can kill young A. altissima trees in 3 mo and larger trees in 1 yr (Schall and Davis Reference Schall and Davis2009), and A. altissima infections with V. nonalfalfae have been confirmed in Pennsylvania (Schall and Davis Reference Schall and Davis2009), Ohio (Rebbeck et al. Reference Rebbeck, Malone, Short, Kasson, O’Neal and Davis2013), and Virginia (Snyder et al. Reference Snyder, Kasson, Salom, Davis, Griffin and Kok2013). It has also been documented in Europe (Lechner et al. Reference Lechner, Maschek, Kirisits and Halmschlager2023).

The goal of this study is to determine the likelihood of soil legacy effects from A. altissima’s allelopathic compounds in response to remnant coarse woody debris that might occur after a windstorm, mechanical and chemical A. altissima treatments, or mortality caused by V. nonalfalfae and L. delicatula. The following questions are addressed: (1) Will soil beneath decomposing A. altissima wood have a negative effect on native species germination and growth? (2) Does this legacy effect spread to areas adjacent to any direct decomposition? (3) Does mulch derived from A. altissima trees negatively affect native species? (4) Do any allelopathic effects vary with light level or native species? (5) Is germination from the seedbank impacted by this legacy effect? (6) Do allelopathic effects vary with soil under garden fabric (weed barrier or tarp) versus grass?

Materials and Methods

Site Description

Ailanthus altissima was grown in a common garden located in Morgantown, WV (39.6508, −79.9869) for 4 yr starting in May 2018. This fenced garden is 625 m2 or 34.25 by 18.25 m in size, and 150 A. altissima seedlings with their first two sets of leaves were planted in ten 15-m rows on a 3% south-facing slope as part of a competition study. Seedlings were grown in plug trays in a greenhouse using seed collected from A. altissima trees in Morgantown, WV. By the end of 4 yr, trees averaged 5.91 cm in basal diameter and were generally 5- to 6-m tall.

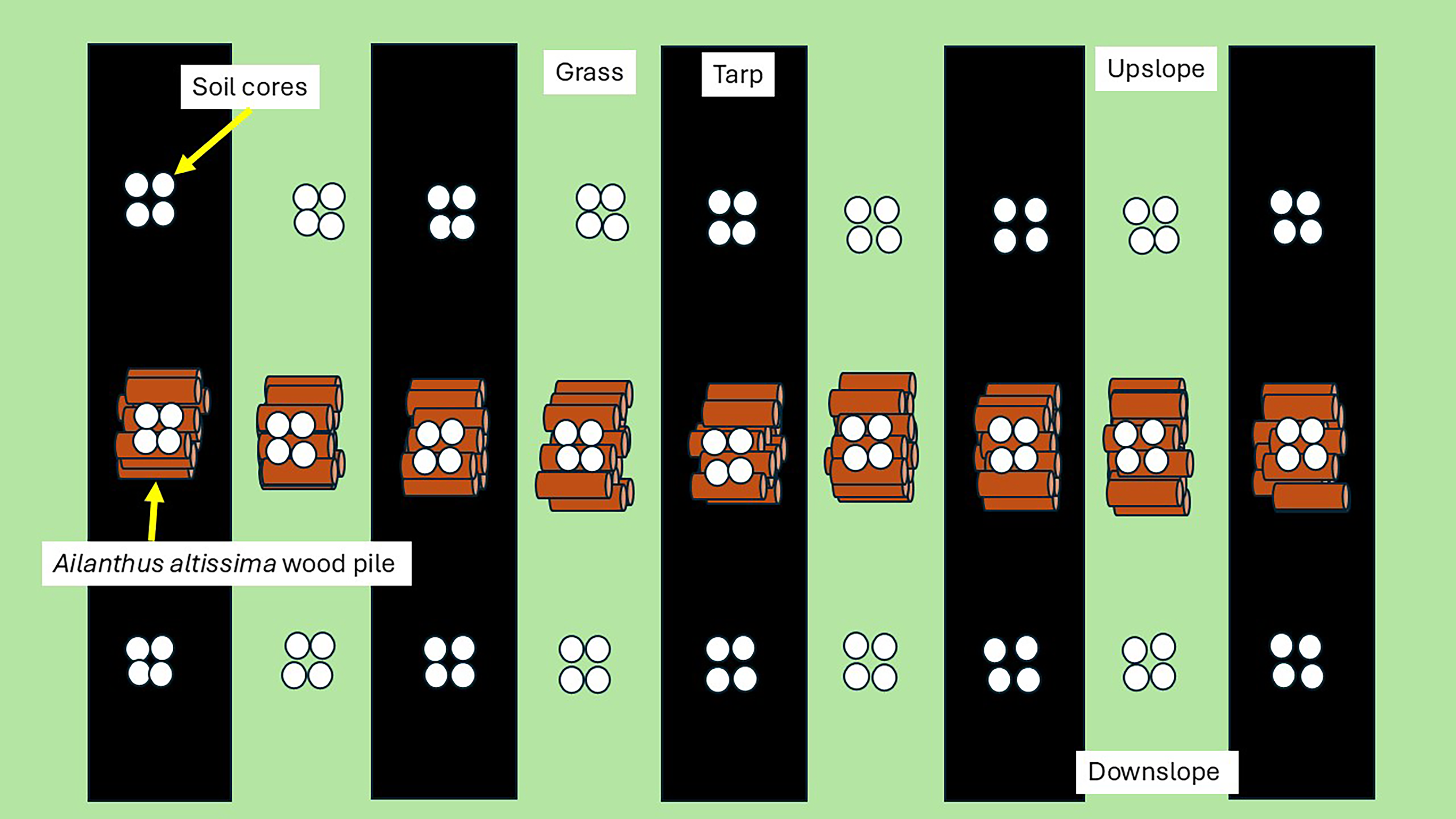

Seedlings were planted in cut-out areas in a breathable (permeable to water, nutrients, and air), woven polypropylene (A.M. Leonard Horticultural Tool and Supplies Company, Piqua, OH, USA) weed barrier or garden fabric (shortened to “tarp” in tables, figures, and remaining text); the covered rows, each 4-m wide, were separated by strips of grass of the same width (Figure 1). The 4-yr-old trees were removed in October 2021 by basally cutting the stem and applying 50% glyphosate to the stumps. The stems were then cut into 1-m sections and placed in piles three stems high with stems varying in basal diameter from 3 to 10 cm in the same garden the A. altissima trees had been growing. These woodpiles were left to decompose for 18 mo both on grass and on tarp (Figure 1). After this time, the woodpiles were mulched in a chipper and the mulch was stored in plastic trash bags outside for 8 mo, with potential for leaching. Some water and air could get in and out due to the thin plastic and some breakdown of the plastic by UV radiation.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of common garden sampling area.

There is, thus, a potential for allelopathic compounds to be generally present in the soil from 4 yr of A. altissima growth with no removal of leaf litter before the establishment of the woodpiles. This fact would be similar to A. altissima–invaded sites before any A. altissima chemical treatment or death, although the age of the trees before treatment or loss may differ. The goal was to mimic conditions after a control treatment or a mortality event.

Experimental Design

Four 10-cm-deep soil cores were taken directly under each woodpile as well as 2-m upslope and downslope from the piles on tarp and on grass. Soil was collected after the 18 mo of decomposition in early May 2022. Soil was sieved and stored in a freezer at −20 C for 8 mo. Fifty grams of this soil were added as 0.5-cm layer over potting media in 3.79 L (1-gal) pots.

Twenty seeds each of three native perennials were planted together in each pot directly on top of the field soil on January 2, 2023. These species were purple coneflower [Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench; open-areas species], dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum L.; roadside species), and false nettle [Boehmeria cylindrica (L.) Sw.; woodland species]. These species were chosen for their habitat preference, general expected size, and the fact none require seed pre-stratification (e.g., moist and cold conditions for 30 to 60 d) for germination. Seeds were purchased from Prairie Moon Nursery (Winona, MN, USA). A 1-cm layer of potting media was placed on top of the seed for half the pots. The other half had A. altissima mulch added, also as a 1-cm layer. These native perennials were not planted directly in the common garden because it was not possible to evaluate the effect of different light levels on the three species of variable light preferences, and we could not control for the effects of all herbivory (small mammals and insects).

Pots were kept in a high-light (∼400 μmol m−2 s−1) greenhouse room and a low-light (∼200 μmol m−2 s−1) greenhouse room with daytime and nighttime temperatures between 24 and 29 C and 16 and 21 C, respectively. Light and daylengths (14 h to mimic late spring) were maintained using supplemental high-pressure sodium lights. Because the three species prefer different light levels, evaluating germination and growth under two light levels may enable managers to predict how each species may germinate, grow, and interact under open (e.g., old fields or roadsides) and less open (e.g., disturbed or thinned forest) conditions. Pots were given ample nutrients (Peters 20-10-20 N-P-K fertilizer (J.R. Peters, Inc., Allentown, PA, USA); 16 g L−1 every 2 wk for the first month and then once a week) and water for 3 mo. The greenhouse experimental design has seven different “soil treatments,” two light levels, two mulch types (with or without A. altissima mulch), and five replications for a total of 140 pots (Table 1). Each of the five replicates was placed on a separate table in each of two different light-level rooms in the greenhouse, and the five tables were centrally located in the rooms. On each table, the 14 pots were randomly located by treatment (7 soil treatments *mulch/no mulch = 14 pots per table per room).

Table 1. Experimental design using seven different soil treatments from the common garden each with or without Ailanthus altissima mulch (potting media above the seed) and at two light levels as part of the experiment designed under controlled conditions in a greenhouse.

a AA, soil collected directly below the decomposing A. altissima woodpiles; Tarp, soil collected from under the black tarp that kept light out but allowed water through; Grass, soil collected from under grass; C, control where soil was collected outside of the decomposing woodpiles and with no likely gravitational movement of allelopathic compounds or potting media only; Up, 2-m upslope from the decomposing woodpile; Down, 2-m downslope from the decomposing woodpile.

These seven soil treatments included soil from (1) below the woodpiles, (2) upslope and (3) downslope from the woodpiles, with all collected from under either tarp or grass (3 *2 = 6 treatments). In addition, the seventh treatment had no field soil, containing only potting media, and thus no effects from A. altissima being present as adult trees as well as no soil microbiota. The two controls were (1) the upslope treatment, which tests the effects of the woodpile compared with the general soil in the invaded site (e.g., what would be expected if wood is not removed from the site versus if it were to be removed), as well as removing possible allelochemical gravitational leaching represented by the downslope treatment; and (2) the potting media–only treatment, which tests the potential effects of any remnant allelochemicals not directly associated with the woodpiles as well as any interactions the soil microbiota may have with allelochemicals potentially still present in the added mulch.

Germination and Growth Measurements

Individual plants, including any new germinations, were tallied each month (January, February, and March) for each species in each pot. March data represent a total count of surviving stems and germinations per species minus any individual stem deaths; these were used for the germination-related analyses in this study. Because the collected field soil could contain a seedbank, we also tallied other plant species that germinated from the field soil at the same time we tallied the three planted species. Seedbank individuals were removed once identified to reduce additional competition from these plants as they grew in size. None of the three planted species have ever been seen in the common garden at least 25 years and consequently were unlikely to germinate from the seedbank.

At the end of 3 mo, shoots for each planted species in each pot were cut at the root collar, placed in a paper bag, and dried for 3 d at 70 C in a drying oven and then weighed. Root dry biomass was also determined by washing roots, drying at 70 C for 3 d, and weighing, but all three species were combined, because roots for each species could not be easily differentiated. Because of the labor involved, roots were only washed for all the treatments with soil collected directly under the decomposing woodpiles, the potting media–only treatments, and the grass–upslope treatments, excluding the tarp–upslope, the grass–downslope, and the tarp–downslope treatments.

Soil Chemistry

Soil chemistry (pH, % organic material, total N, total C, Ca, K, Mg, P, Al, Fe, Mn, Zn, and effective cation exchange capacity [ECEC]) was evaluated on another 80 g of the soil collected (Maine Agriculture and Forest Experiment Station Analytical Laboratories and Maine Soil Testing Service, Orono, ME). Soil pH was measured in distilled water. Organic matter was measured by percent lost on ignition at 550 C. Total nitrogen and carbon were measured as percentages by combustion analysis at 1,350 C. Exchangeable cations (Ca, K, Mg, P, Al, Fe, Mn, and Zn) were extracted in ammonium chloride and measured by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES; units of mg kg−1). ECEC was calculated by the summation of milliequivalent levels of Ca, K, Mg, Na, and acidity with units of milliequivalents per 100 g of soil. ECEC is a measure of available cations and an estimate of soil fertility.

Statistical Analyses

The germination and dry shoot biomass of the three species under the seven treatments with and without mulch and under high or low light were compared statistically using general linear mixed models. Distributions were determined for each variable using univariate analyses to compare different distribution types (normal, lognormal, etc.) and selecting the one(s) that passed three goodness-of-fit tests (Proc Univariate in SAS v. 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A Tukey adjusted post hoc comparison of the least-square means was conducted for multiple comparisons. Each of the three species was evaluated separately.

Germination counts for all three species and the seedbank used a negative binomial distribution (Proc Glimmix in SAS v. 9.4). The best distribution for E. purpurea shoot biomass and root biomass was gaussian, using the default identity link function. In contrast, A. cannabinum’s and B. cylindrica’s best distributions for their shoot biomass were gamma with its default log link function (Proc Glimmix in SAS v. 9.4). Soil chemistry variables were evaluated separately as dependent variables across the six field soil treatments (soil treatment being the independent variable) using one-way ANOVAs; all variables met normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions except P, Al, Fe, Zn, and ECEC, which were log transformed (Proc GLM in SAS v. 9.4). The main interest here was to determine any spatial patterns in soil chemistry across the soil treatments, not to do a full evaluation of how these soil chemistry variables may be interacting.

Results and Discussion

Question 1: Will Soil Beneath Decomposing Ailanthus altissima Wood Have a Negative Effect on Native Species Germination and Growth?

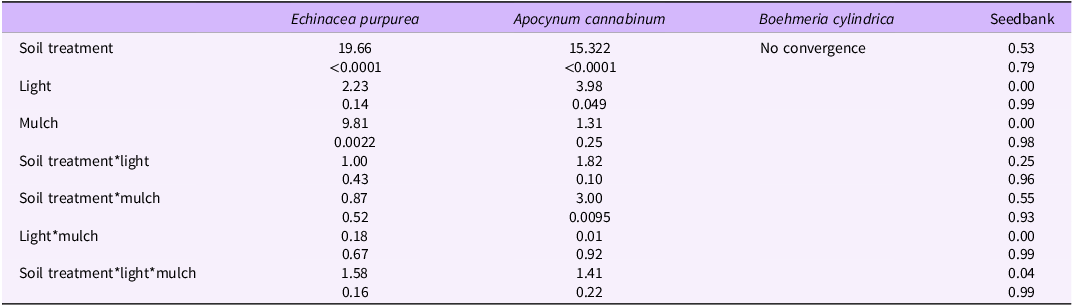

The germination counts under the different soil treatments differ significantly from one another for E. purpurea, with both woodpile-soil treatments having significantly fewer germinations than the other five soil treatments. Soil treatments with A. altissima mulch added had significantly more E. purpurea germinating than soil treatments without the A. altissima mulch. The two light levels did not differ significantly, and there were no significant interactions (two-way or three-way) for E. purpurea germinations (Table 2). Germinations for E. purpurea were significantly fewer in all pots with soil collected directly under the decomposing A. altissima woodpiles (called “woodpile soil” from this point forward in the text) than all the non–woodpile soil treatments under grass. The woodpile-soil treatments under grass and without mulch under both light conditions were also significantly different from all the non–woodpile tarp and potting media–only treatments (Figure 2A; Table 2). Similarly, the woodpile-soil treatments under tarp and without mulch were significantly different from all non-woodpile treatments under tarp as well as all potting media–only treatments (Figure 2A; Table 2).

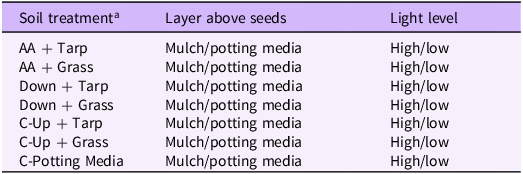

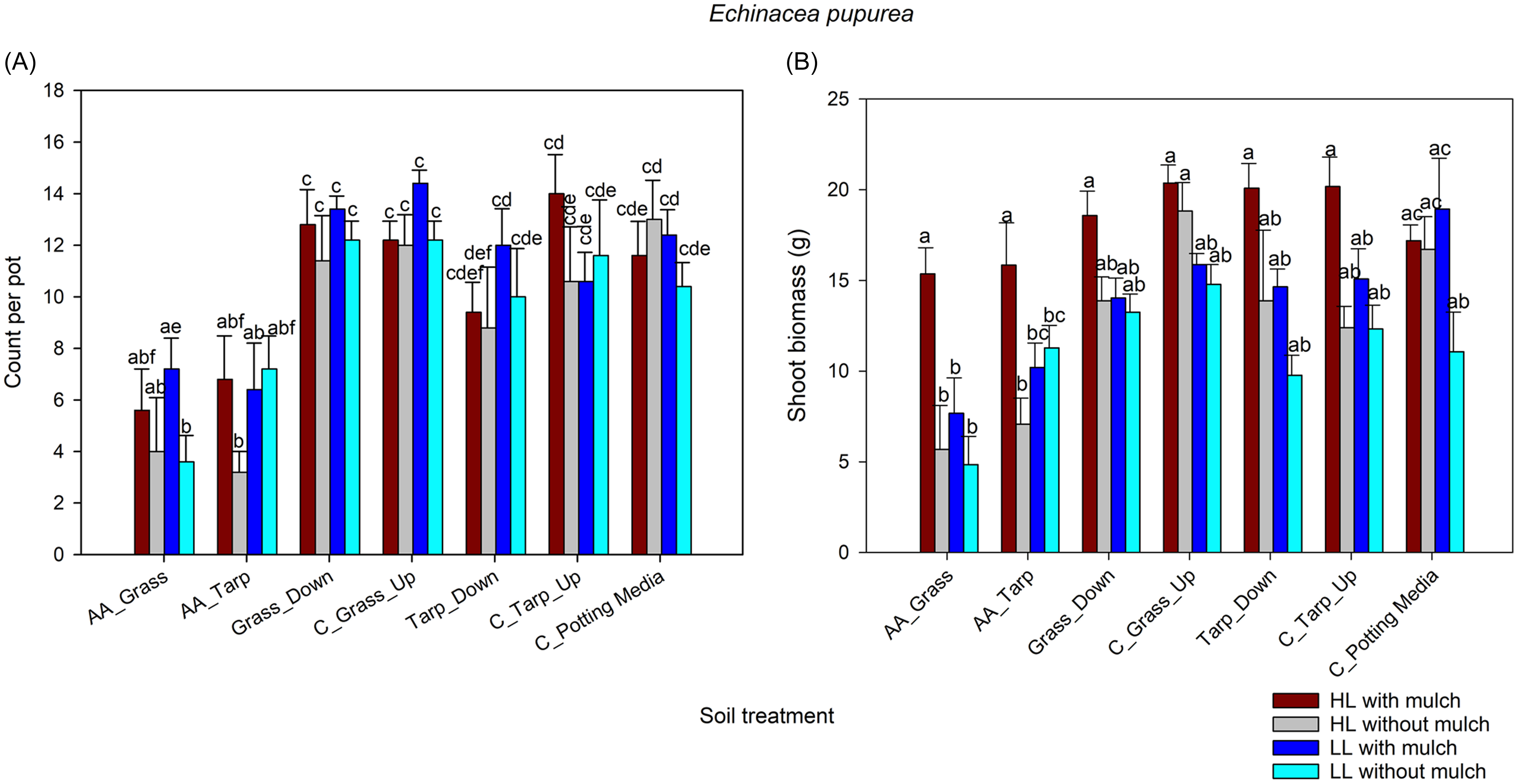

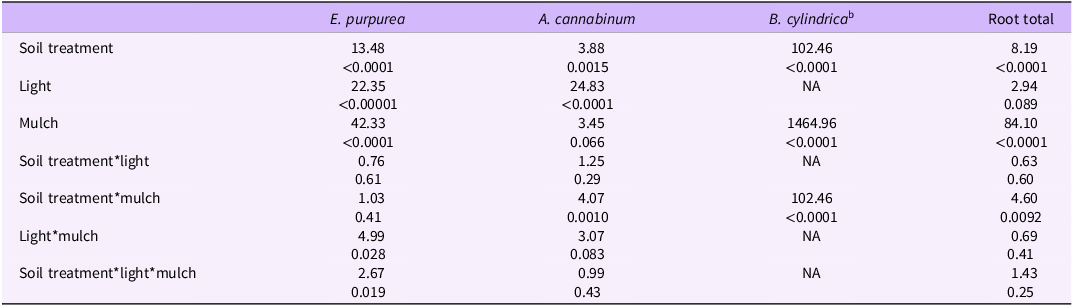

Table 2. Comparison of germination by soil treatment with or without Ailanthus altissima mulch under two light levels for each species and the total seedbank germinations using general linear mixed model using a negative binomial distribution a .

a F-values and P-values presented: first line = F statistic; second line = P-value.

Figure 2. (A) Comparison of Echinacea purpurea germinations across soil treatment (defined in Table 1) with and without Ailanthus altissima mulch under two light levels, using a general linear mixed model with a negative binomial distribution. (B) Comparison of E. purpurea dry shoot biomass across soil treatments with and without A. altissima mulch under two light levels, using a general linear mixed model with a gaussian distribution and identity link function. Treatments with different letters are significantly different (α < 0.05) based on Tukey adjusted post hoc comparisons of the least-square means. AA, soil under A. altissima woodpiles; HL, high light in greenhouse; LL, low light in greenhouse; C, control; Down, 2-m downslope from woodpile; Up, 2-m upslope from woodpile.

Both woodpile-soil treatments had significantly lower E. purpurea shoot biomass weights than the remaining five soil treatments, except the downslope-tarp treatment did not differ significantly from the woodpile-tarp treatment. Pots under high light had significantly more E. purpurea shoot biomass than pots under low light. Pots with added A. altissima mulch had significantly higher E. purpurea shoot biomass than pots without added A. altissima mulch, but there was a significant two-way interaction between the presence or absence of mulch and light level as well as a significant three-way interaction (soil treatment, presence or absence of mulch, and light level; Table 3). Shoot biomass of E. purpurea manifested lower values associated with the woodpile-soil than non–woodpile soil treatments, except when mulch was present. There was a trend for all non-woodpile treatments under high light and with mulch to show greater biomass than the woodpile treatments without mulch (Figure 2B).

Table 3. Comparison of shoot biomass by soil treatment with and without Ailanthus altissima mulch under two light levels for each species and total root biomass using a general linear mixed model (gaussian distribution with identity link function for Echinacea purpurea shoot biomass, and root biomass; gamma distribution with log link function for Apocynum cannabinum and Boehmeria cylindrica) a .

a F-values and P-values presented: first line = F statistic; second line = P-value.

b Boehmeria cylindrica only germinated under low-light conditions; so light was not evaluated as a variable for biomass.

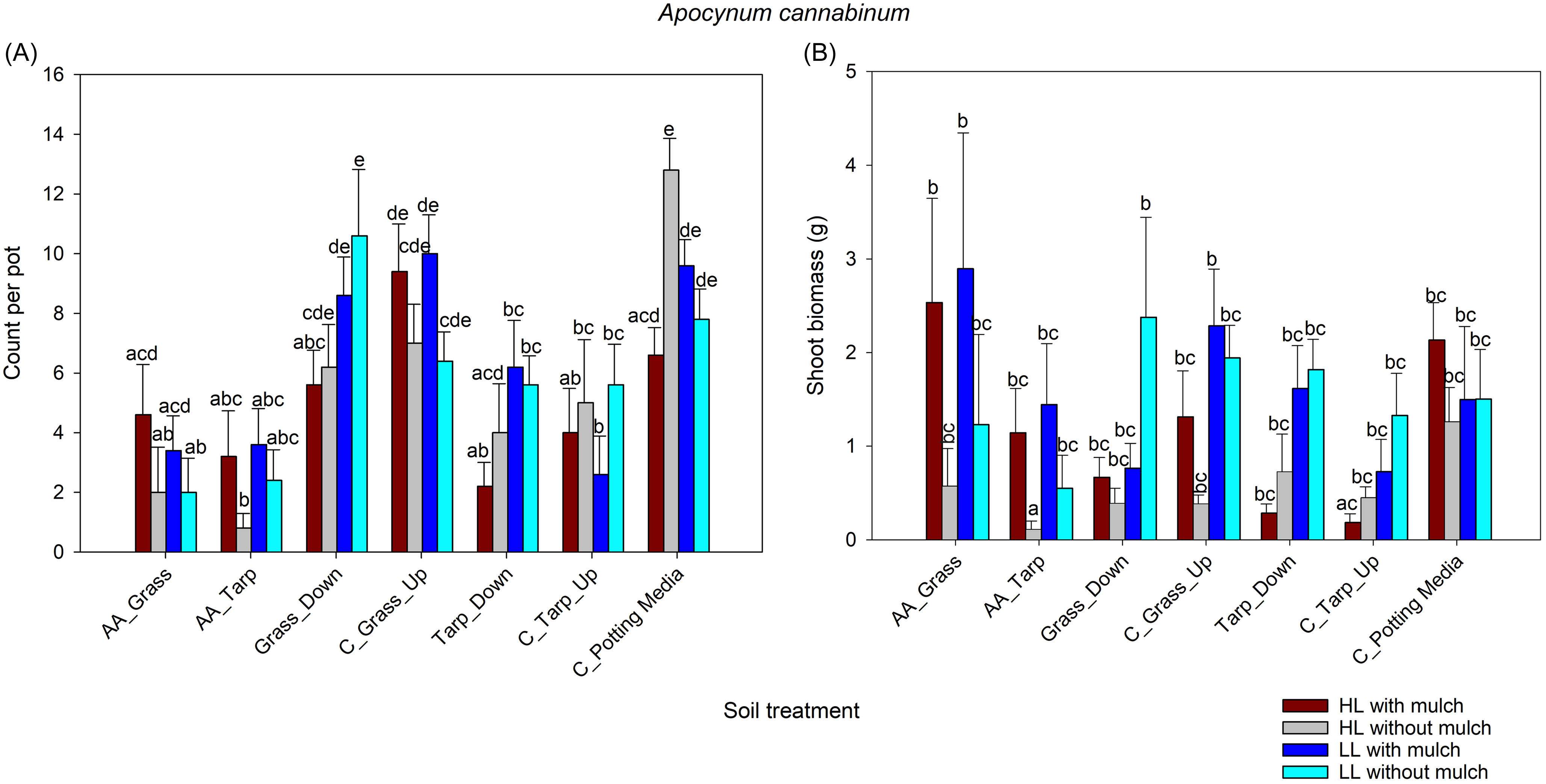

Apocynum cannabinum germinations for the woodpile-soil treatments and the non–woodpile tarp soil treatments were significantly lower than the non–woodpile grass soil treatments and the potting media–only treatment. Pots under lower light had significantly more A. cannabinum germinations than pots under high light. Although pots with added A. altissima mulch had more A. cannabinum seed germinating, it was not significant. However, there was a significant interaction between soil treatment and presence or absence of A. altissima mulch (Table 2). Apocynum cannabinum germinations were fewer for the woodpile-soil treatments than the grass and potting media–only treatments, but similar to the treatments under the tarp (Figure 3A; Table 2). The largest number of germinations for A. cannabinum were associated with the soil treatments under grass in low light (with and without mulch) and the potting media–only treatments in high light without mulch and low light with and without mulch (Figure 3A; Table 2).

Figure 3. (A) Comparison of Apocynum cannabinum germinations across soil treatments (defined in Table 1) with and without Ailanthus altissima mulch under two light levels, using a general linear mixed model with a negative binomial distribution. (B) Comparison of A. cannabinum dry shoot biomass across soil treatments with and without A. altissima mulch under two light levels, using a general linear mixed model with a gamma distribution and log link function (after adding 0.001 to all to remove zeroes). Treatments with different letters are significantly different (α < 0.05) based on Tukey adjusted post hoc comparisons of the least-square means. AA, soil under A. altissima woodpiles; HL, high light in greenhouse; LL, low light in greenhouse; C, control; Down, 2-m downslope from woodpile; Up, 2-m upslope from woodpile.

For shoot biomass, Apocynum cannabinum shows a less distinct response than E. purpurea to the woodpile-soil treatment, with pots containing the woodpile and tarp soil showing significantly lower A. cannabinum biomass than pots containing the woodpile and grass soil or potting media only. Also, unlike E. purpurea, A. cannabinum shoot biomass was significantly greater for pots growing in low light than in high light. Pots with added A. altissima mulch had only marginally significant greater shoot biomass than pots without the added A. altissima mulch, and there was a significant two-way interaction with soil treatment (Table 3). Shoot biomass of A. cannabinum for the woodpile-soil under tarp treatment, without A. altissima mulch and under high light, was significantly lower than all but the control upslope tarp treatment with mulch and under high light. All other treatments did not differ significantly but there was a trend for greater biomass in woodpile-soil with mulch than without mulch and in non–woodpile soil treatments under low light (Figure 3B; Table 3). The largest shoot biomass of A. cannabinum, which was found with the woodpile-soil treatment under low light and with mulch (Figure 3B), was nearly seven times smaller than the largest shoot biomass of E. purpurea found under the control-grass-upslope and mulch treatment (Figure 2B).

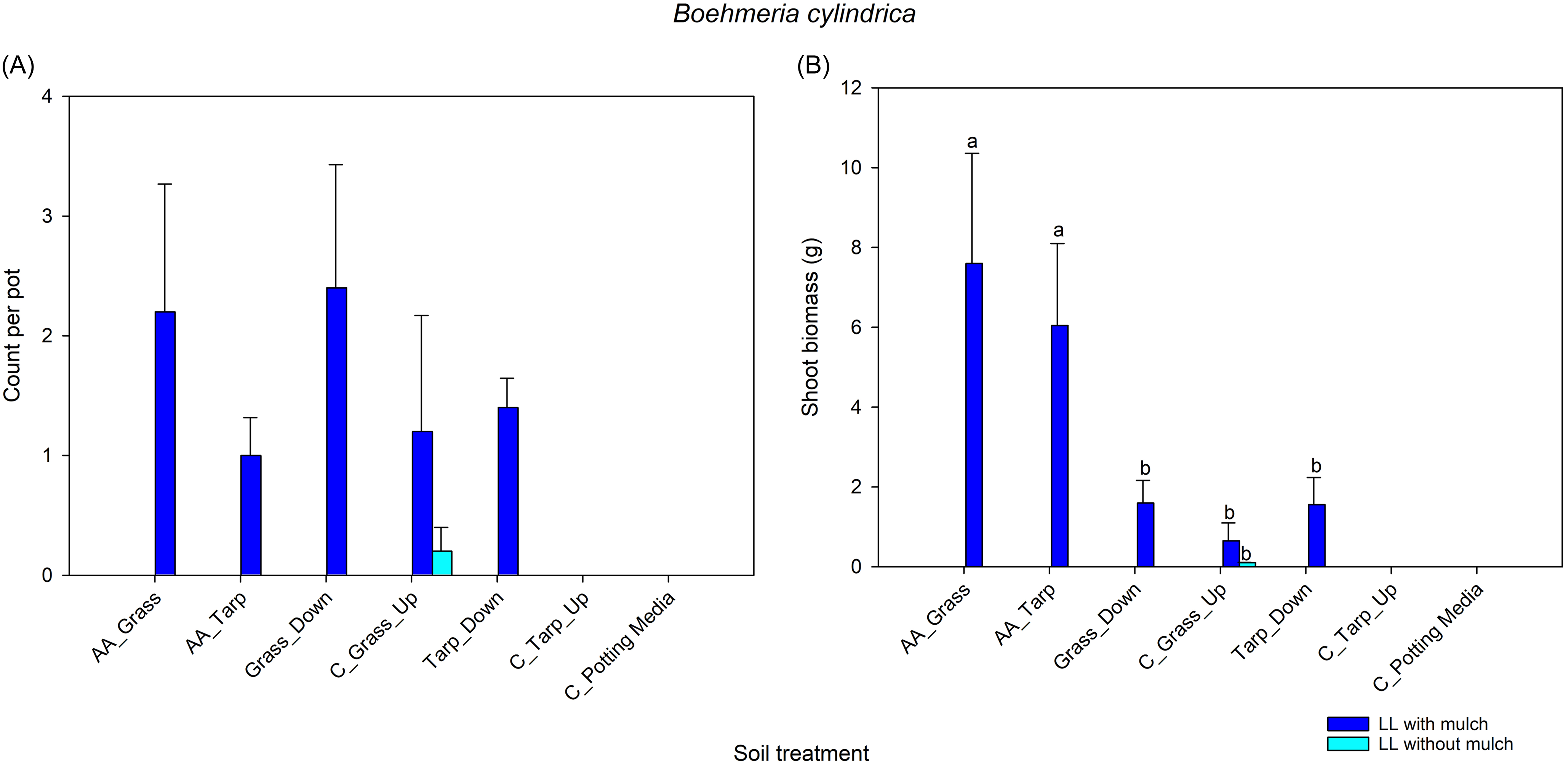

Boehmeria cylindrica germinated only under low-light conditions and in pots with mulch (except for the control-grass-upslope soil treatment) (Figure 4A; Table 2). The lack of data prevented the germination model from converging, making it impossible to statistically compare its germination responses with the other two species.

Figure 4. (A) Comparison of Boehmeria cylindrica germinations across soil treatments (defined in Table 1) with and without Ailanthus altissima mulch under two light levels, using a general linear mixed model with a negative binomial distribution. (B) Comparison of B. cylindrica dry shoot biomass across soil treatments with and without A. altissima mulch under two light levels, using a general linear mixed model with a gamma distribution and log link function (after adding 0.001 to all to remove zeroes). Treatments with different letters are significantly different (α < 0.05) based on Tukey adjusted post hoc comparisons of the least-square means. There was no germination or subsequent growth under high-light conditions. AA, soil under A. altissima woodpiles; LL, low light in greenhouse; C, control; Down, 2-m downslope from woodpile; Up, 2-m upslope from woodpile.

Boehmeria cylindrica’s shoot biomass was greatest in the woodpile-soil treatments, which had significantly greater biomass than in the B. cylindrica non–woodpile soil grass and tarp treatments. There was no shoot biomass in the high-light room to compare light levels for B. cylindrica. The significant interaction between presence or absence of mulch and soil treatment is due to only one soil treatment without mulch having any measurable B. cylindrica biomass (Figure 4B; Table 3).

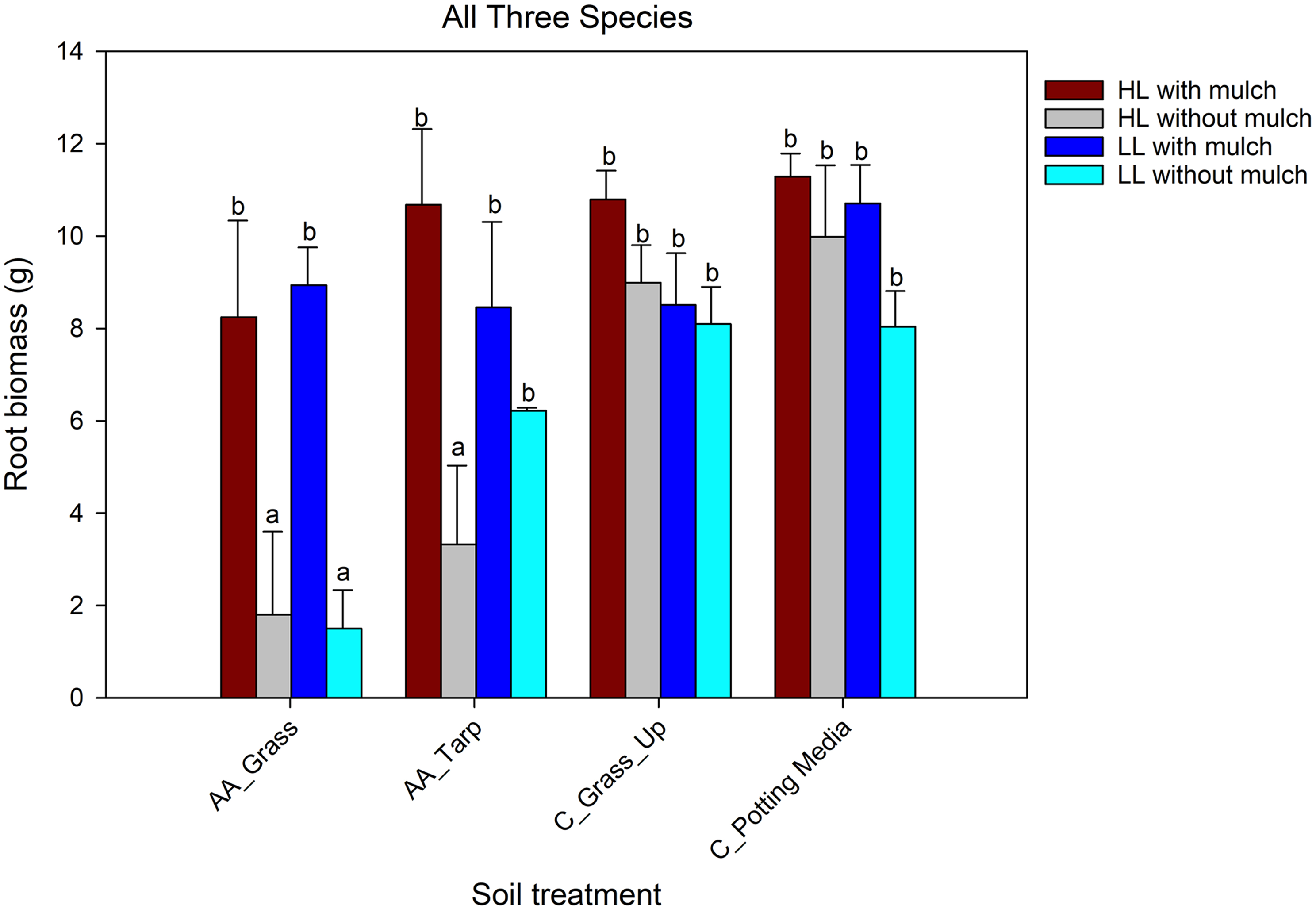

Both woodpile-soil treatments had significantly lower root biomass than the potting media–only treatment. The woodpile-soil treatment in grass also had significantly lower root biomass than the control upslope grass soil treatment, but this latter treatment did not differ significantly from the woodpile-soil tarp treatment. Root biomass did not differ under the two light levels, but was significantly greater for treatments with added A. altissima mulch than without the mulch. There was a significant two-way interaction between soil treatment and the presence or absence of A. altissima mulch (Table 3). Root biomass of the plants grown in woodpile soil was significantly lower for treatments without mulch, except the tarp treatment under low light (Figure 5; Table 3). These results support a negative effect of the allelopathic compounds from the woodpile soil on root growth, but added mulch reduces this effect. This is similar to the shoot biomass patterns found for E. purpurea and A. cannabinum (Figures 2B and 3B).

Figure 5. Comparison of dry root biomass of all three species combined across soil treatments (defined in Table 1) with and without Ailanthus altissima mulch under two light levels. Comparisons were made using a general linear mixed model with a gaussian distribution and identity link function. Root biomass was combined, because roots of the three species could not be reliably differentiated. Missing soil treatments (Grass_Down, C_Tarp_Up, and Tarp_Down) did not have roots washed due to the additional labor required. AA, soil under A. altissima woodpiles; HL, high light in greenhouse; LL, low light in greenhouse; C, control; Up, 2-m upslope from woodpile.

Greater shoot biomass under low-light treatments for A. cannabinum suggests a possible competitive effect with E. purpurea under high-light conditions. Echinacea purpurea prefers high light or open habitats; it is not surprising that in this study it had greater germination and biomass than A. cannabinum under high light (Figures 2–4). Boehmeria cylindrica only germinated under low-light conditions, its preferred habitat, and consequently had no biomass to compare under high-light conditions. In contrast to E. purpurea and A. cannabinum, its greatest biomass under low-light conditions was in the woodpile-soil treatments (Figure 4B), where it would be experiencing less competition from both E. purpurea and A. cannabinum due to lower germination, survival, and growth when compared with the other soil treatments (Figure 3B).

Despite the subsequent growth differences among the three species in response to competition with E. purpurea, these results highlight the negative effects of woodpile-soil on E. purpurea and A. cannabinum’s germination, which may be explained by allelopathic compounds leaching from the decaying A. altissima woodpiles. Allelopathic effects of A. altissima include negative impacts on germination and early growth of native plants (Gómez-Aparicio and Canham Reference Gómez-Aparicio and Canham2008; Naveed et al. Reference Naveed, Ullah, Reema, Azam, Khalid, Momin and Paveen2024; Small et al. Reference Small, White and Hargbol2010). Negative effects of allelopathic compounds on the germination of native species are well documented by studies that evaluate the effects of allelopathic compounds from mostly leaf extracts (Morgan and Overholt Reference Morgan and Overholt2005; Prati and Bossdorf Reference Prati and Bossdorf2004; Souto et al. Reference Souto, Gonzales and Reigosa1994) and from some stem extracts (Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Colwell and Sexton1991). Other studies use trained soil where A. altissima was growing as a dominant tree to evaluate the soil’s effect on the growth of native and non-native species (Small et al. Reference Small, White and Hargbol2010) or its effects on both germination and growth of native trees planted as seed near patches of A. altissima trees (Gómez-Aparicio and Canham Reference Gómez-Aparicio and Canham2008). This study is the first that evaluates the effects of decomposing A. altissima wood from field-collected soil on native plant germination and growth under a controlled greenhouse setting.

It is important to highlight that the soil collected in this study is the product of 18 mo of leaching of decomposing A. altissima wood. Soil collected after a longer period of leaching may contain more allopathic compounds due to more decomposition or it could contain less if these chemicals are removed from the bark and outer wood earlier rather than throughout decomposition. More research is needed to determine allelopathic compound leaching and interactions with soil microbes over time.

Question 2: Does This Legacy Effect Spread to Areas Adjacent to Any Direct Decomposition?

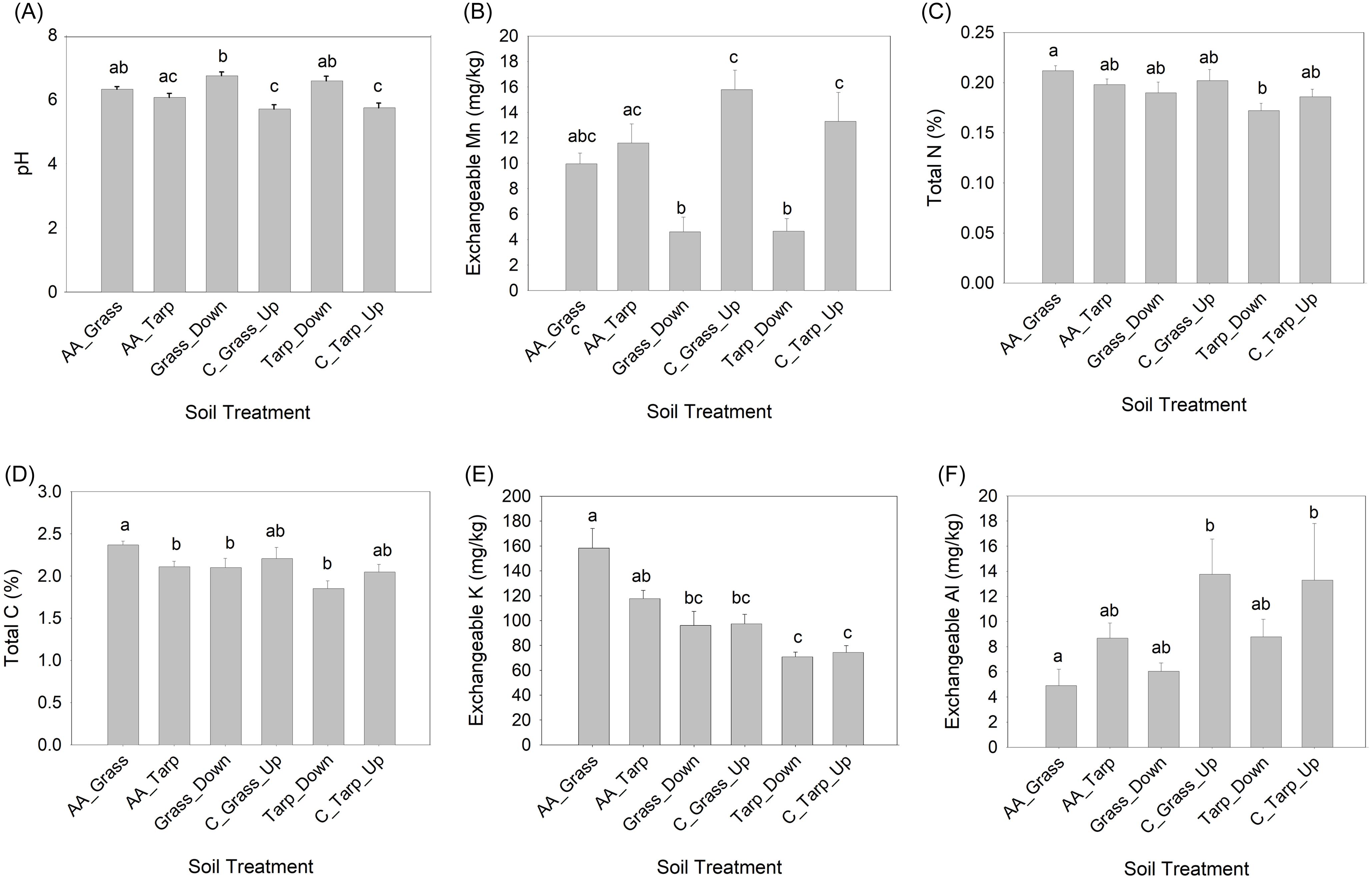

There was no significant difference of the effects of woodpile-soil treatments on perennial plant germination and growth between upslope or downslope samples, suggesting no gravitational movement of allelopathic compounds in the soil. However, there were some significant differences in soil properties that may be related to the decomposing woodpiles. Soil pH (F = 11.45; P < 0.0001) and exchangeable Mn (F = 9.84; P < 0.0001) of the control upslope treatments were significantly more acidic and more concentrated, respectively, than the downslope treatments (Figure 6A and 6B). Total N (F = 2.88; P = 0.36) and total C (F = 3.36, P = 0.019) were greater for woodpile-soil under grass than for the tarp, downslope treatment (Figure 6C and 6D). Exchangeable K (both upslope and downslope; F = 11.92; P < 0.0001) was greater for woodpile-soil treatments than for the tarp treatments (Figure 6E). Exchangeable Al (F = 3.86; P = 0.010) was greater for both control upslope treatments than for the woodpile-soil under grass treatment (Figure 6F; Supplementary Table 1). Overall, the soil under the decomposing woodpiles was more fertile (more K, total N, and total C; less Al) than the non–woodpile soil treatments, but the downslope treatments tended to be less acidic than the upslope treatments. The latter could be due to some leaching of nutrients downward from the woodpiles, but it is also possible these differences between the upper and lower slopes existed before the effects of decomposition. Ailanthus altissima’s presence in sites has been associated with increasing soil fertility (Medina-Villar et al. Reference Medina-Villar, Castro-Díez, Alonso, Cabra-Rivas, Parker and Pérez-Corona2015); A. altissima wood decomposition may show similar tendencies. Despite the higher soil fertility, the impact of woodpile soil on two of the seeded perennial species’ germination in this study was negative, but this effect does not appear to spread 2 m or more beyond the decaying pile of A. altissima wood.

Figure 6. Comparison of soil variables by soil treatment using one-way ANOVAs for (A) pH, (B) exchangeable Mn, (C) total N, (D), total C, (E) exchangeable K, and (F) exchangeable Al. All variables met normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions except Al, which was log transformed (but actual values are shown). Full set of soil variables can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Questions 3 and 4: Does Mulch Derived from Ailanthus altissima Trees Negatively Affect Native Species and Do Any Allelopathic Effects Vary with Light Level or Native Species?

Echinacea purpurea germination was significantly lower in the woodpile-soil treatment without mulch compared with pots with mulch (Table 2), but only in treatments under grass and low light. There was a clear trend for E. purpurea under the woodpile-soil treatments to have greater germination when mulch was present, but light was not an important factor in E. purpurea germination (Figure 2A; Table 2), although it was very important for E. purpurea’s shoot biomass (Table 3). Echinacea purpurea’s shoot biomass was significantly greater with mulch for the woodpile-soil treatment (both grass and tarp) under high light (Figure 2B; Table 3).

Apocynum cannabinum shared the trend (though not significant) with E. purpurea of greater germination when mulch was present in the woodpile-soil treatments, (Figure 3A; Table 2). In contrast, there was significantly greater germination of A. cannabinum seed in the potting media–only (lack of soil microbes), high-light treatment without mulch (Figure 3A), supporting possible negative allelopathic effects of the mulch that could not be removed by soil microbes that would be found with the field soil. This pattern was not shared by E. purpurea (Figure 2A). It is possible that A. cannabinum germination is more sensitive to lower concentrations of allelopathic compounds (those that may remain in the mulch) under high-light conditions. Alternatively, the lack of beneficial mycorrhizae in the potting media–only control may have made acquisition of nutrients from the mulch more difficult for A. cannabinum seeds because of A. cannabinum’s association with vesicular-arbuscular endomycorrhizal fungi (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Clements, Darbyshire and Dauer2009; Rickerl et al. Reference Rickerl, Sancho and Ananth1994). Greater A. cannabinum shoot biomass is associated with mulch in the woodpile-soil treatment (both grass and tarp) under high light, but was only marginally significant, with the woodpile-soil, high-light, tarp with no mulch treatment showing the lowest biomass (Figure 3B; Table 3).

Mulch and lower light conditions were critical for germination of B. cylindrica, but significance could not be evaluated due to a lack of data in many of the treatments (Figure 4A; Table 2). Because there was only germination under low light with mulch and no germination in the control tarp upslope and potting media–only treatments, comparisons of shoot biomass are also limited. The results show significantly greater B. cylindrica shoot biomass in the woodpile-soil treatments than the control treatments (Figure 4B; Table 3), likely due to less competition from E. purpurea and A. cannabinum under the woodpile-soil treatments.

Root biomass combined for all three species was greater in the pots with mulch in the woodpile-soil treatments, except for the woodpile-soil low-light, tarp treatment. Unlike with germination and shoot biomass of the separate species, total root biomass was not significantly impacted by light (Figure 5; Table 3). However, this is likely a factor of combining the three species, which respond differently to the light conditions.

The positive effect of A. altissima mulch suggests that any remnant allelopathic compounds in the mulch were gone or were in such small amounts that soil microbes remaining in the thin layer of soil could break them down. Mulch was bagged but stored outside for an additional 8 mo beyond the 18 mo the woodpiles were left to decay. The rate of loss of the allelopathic compounds may be greater if the wood is broken down (i.e., mulched), exposing more surface area to fungi and microbes. Allelopathic effects appear to have dissipated over time, not unlike melaleuca [Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S.F. Blake] and eucalyptus (Eucalyptus grandis W. Hill ex Maid.), whose mulch shows no significant allelopathic impacts after 6 mo and decreased impacts as soon as 3 mo (Duryea et al. Reference Duryea, English and Hermansen1999).

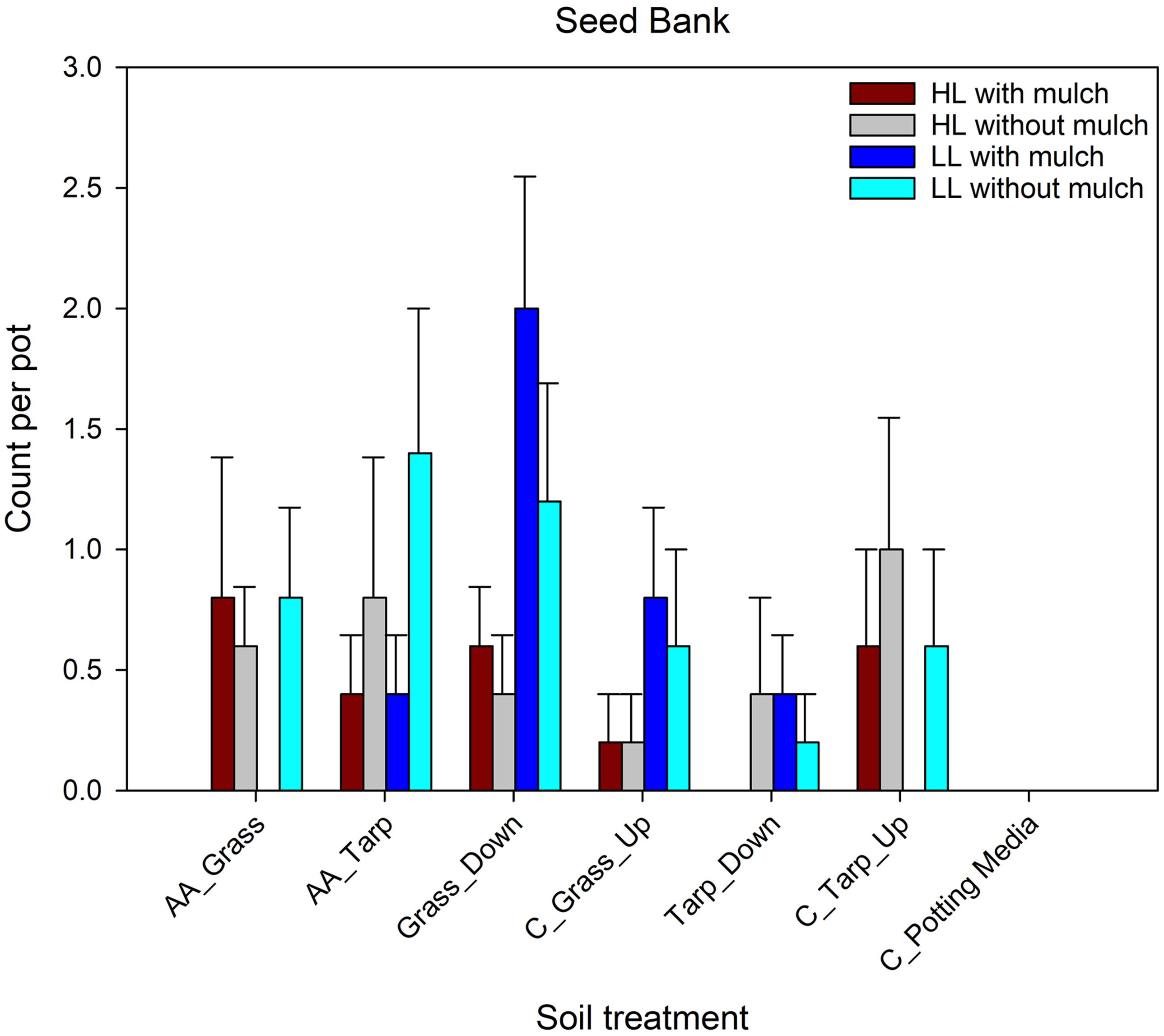

Question 5: Is Germination from the Seedbank Impacted by This Legacy Effect?

There was no negative effect of woodpile soil on the existing seedbank germinations and no treatments differed significantly from one another (Figure 7; Table 2). The most common species that germinated from the seedbank included (in order of importance) common yellow sheep sorrel (Oxalis stricta L.; native), prostrate spurge (Chamaesyce maculata (L.) Small; native), broadleaf plantain (Plantago major L.; non-native), spreading cinquefoil (Potentilla simplex Michx.; native), brambles (Rubus L. sp.; native), thymeleaf speedwell (Veronica serpyllifolia L.; native), common blue violet (Viola sororia Willd.; native), and sedges (Carex L. sp.; native). These species are common early-successional species that are often found in disturbed areas. The non-native P. major has been in the United States since the 1700s; its native range (Europe and parts of Asia) may overlap with A. altissima ’s native and invasive ranges. There was no evident difference in how native versus non-native species in the seedbank responded to the woodpile soil. The lack of effect on germinating plants from the seedbank supports Lawrence et al.’s (1991) finding that plants pre-exposed to A. altissima’s allelopathic compounds are likely to be impacted less in subsequent exposures. Brooks et al. (Reference Brooks, Barney and Salom2021) also showed no impact on seedbank composition or germinating seedling abundance in sites dominated by A. altissima compared with adjacent sites with no A. altissima. However, these findings differ from other research where allelopathic compounds of the invasive shrub desert wormwood (Artemisia herba-alba Asso) did not change the species composition of the seedbank but did reduce the number of germinating individuals (Arroyo et al. Reference Arroyo, Pueyo, Reiné, Giner and Alados2017). Similarly, artichoke thistle (Cynara cardunculus L.) allelopathic compounds reduced the total number of seed germinating from the seedbank and in some cases also decreased the richness of species in the seedbank (Scavo et al. Reference Scavo, Restuccia, Abbate and Mauromicale2019). Indeed, some cover crops, such as canola (Brassica napus L.), cultivated radish (Rhaphanus sativus L.), mustard species (Brassicaceae spp.), and annual ryegrass [Lolium perenne L. ssp.multiflorum (Lam.) Husnot], are used for their allelopathic compounds to suppress other weeds that might be present in the seedbank (Sias et al. Reference Sias, Wolters, Reiter and Flessner2021). Our results, however, would indicate that A. altissima would not help suppress existing weeds in the soil, except perhaps immediately after A. altissima was first introduced into a site.

Figure 7. Comparison of seedbank germinations across soil treatment (defined in Table 1) with and without Ailanthus altissima mulch under two light levels. Comparisons were made using a general linear mixed model with a negative binomial distribution. No soil treatments with or without A. altissima mulch or under the two light levels were significantly different from each other. AA, soil under A. altissima woodpiles; HL, high light in greenhouse; LL, low light in greenhouse; C, control; Down, 2-m downslope from woodpile; Up, 2-m upslope from woodpile.

Question 6: Do Allelopathic Effects Vary with Soil Under Garden Fabric (Tarp) versus Grass?

Plants growing in soil collected from under garden fabric tended to have low germination values similar to plants growing in soil from below the A. altissima woodpiles, both being lower than values found with the soil treatments under grass. This suggests negative impacts of the fabric possibly associated with a lack of soil microorganisms or particular microbes (Feldman et al. Reference Feldman, Holmes and Blomgren2000). There are several online gardening sites that mention potential negative impacts of landscape fabrics on soil chemistry and soil microbes, possibly due to increased heat. The scientific literature on the effects of garden fabric on plants and soils is limited, with a few stating the negative effects on soil organisms is greater the longer the duration of the fabric cover (Chalker-Scott Reference Chalker-Scott2007). As a related management tool, solarization, or the use of non-breathable plastic covers to kill invasive plants and their seeds in the soil seedbank, is being used increasingly as a management tool and has been found to be effective against weeds but also reduces fungal and bacterial abundance by more than 50% and 20%, respectively (Shinde et al. Reference Shinde, Jagtap, Patil and Khatri2023) and may increase some pathogenic fungi and bacteria (Kokalis-Burelle et al. Reference Kokalis-Burelle, McSorley, Wang, Saha and McGovern2017). Soil temperatures under solarization may reach as high as 60 to 70 C (Bonanomi et al. Reference Bonanomi, Chiurazzi, Caporaso, Del Sorbo, Moschetti and Felice2008), and solarization reduces the infectivity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi after 8 mo of cover (Schreiner et al. Reference Schreiner, Ivors and Pinkerton2001). We may expect similar, though reduced, effects due to breathable garden fabrics.

In this study, the negative effects of using garden fabric on the three native plants are similar to the effects of woodpile soils, especially for A. cannabinum’s germination (Figure 4). Apocynum cannabinum may suffer more from the negative effects of the garden fabric on soil microbes because it benefits from an association with vesicular-arbuscular endomycorrhizal fungi (DiTommaso et al. Reference DiTommaso, Clements, Darbyshire and Dauer2009; Rickerl et al. Reference Rickerl, Sancho and Ananth1994). However, E. purpurea also benefits from arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal associations (Iakab et al. Reference Iakab, Domokos, Benedek, Molnár, Kentelky, Buta and Dulf2022), although possibly more for growth and less for germination. Based on these findings, use of garden fabric and other weed barriers as a management tool may impair restoration efforts after the removal of the target invasive plants.

The garden fabric also had a negative effect on total N (F = 2.88; P = 0.036), total C (F = 3.36; P = 0.019), and exchangeable K (F = 11.92; P < 0.0001) (Figure 6C–E; Supplementary Table 1). These differences in soil chemistry could be due to changes in microbial compositions or abundance due to the increase in heat associated with the black garden fabric or to less available oxygen and a reduced supply of litter. Further research is needed to evaluate interactions between allelopathic compounds, weed barriers, and the soil microbial community.

Conclusions

Soil associated with decomposing A. altissima wood negatively impacts the germination and growth of native plant species, but this impact varies with species and their interactions. The strongest negative impact in this study was with the germination of E. purpurea and A. cannabinum under both high- and low-light conditions without any mulch. The negative effects on growth were again associated with a lack of mulch but were greater under high-light conditions for E. purpurea. Apocynum cannabinum showed signs of competition with E. purpurea under high-light conditions (E. purpurea’s preferred habitat) without woodpile soil. Similarly, B. cylindrica’s growth was greatest under low-light conditions in woodpile soils, suggesting it was competing with both A. cannabinum and E. purpurea in the low-light non–woodpile soil treatments. Plants originating from the soil seedbank were not affected by the woodpile soil, which indicates sites with healthy seedbanks would not be impacted by decomposing A. altissima coarse woody debris as long as A. altissima trees were already present at the site, allowing for some acclimation. Unfortunately, many forested sites have impoverished native seedbanks due to poor silviculture management, deer herbivory, and invasion by exotic plants. This study also indicates that the extended use of garden fabrics and solarization for managing invasive species could have unintentional negative effects on native species restoration. Removal of A. altissima coarse woody debris after herbicide treatments or mortality due to disease may ensure successful restoration of sites where seeding or planting are likely to be required due to depauperate seedbanks. Ailanthus altissima mulch that has been allowed to sit for more than 2 yr, presumably leaching out allelopathic compounds, may be beneficial to native plants. This 2-yr duration may indicate that coarse woody debris left longer than 2 yr may have less of a negative legacy effect on soils than shown in this study where wood decomposed for 18 mo. However, more research is still needed to evaluate the potential duration of allelopathic compounds in decomposing A. altissima wood, which is likely to take much longer to leach out chemicals than its mulch. This study shows that not only are plants used for restoration likely to be negatively impacted by soil with an allelopathic legacy, this legacy effect will also impact how these plants interact with one another.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/inp.2025.10034

Acknowledgments

The following individuals helped make this research possible by helping to plant seeds for both common garden and greenhouse portion of the study, take detailed plant measurements, collect soil samples and process the soil, and maintain the common garden and the greenhouse growing rooms: Lorenzo Ferrari, Jennifer Greenleaf, and Nick Partington.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station operating funds. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or the commercial or non-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The author declares no conflicts of interest.