1 Introduction

High rising terminals (HRT), commonly referred to as “uptalk,” refer to intonational contours that involve a rising pitch at the end of a declarative utterance (Levon Reference Levon2020). Essentially, uptalk occurs when declarative statements are produced with a rising intonation, phonetically resembling the pitch pattern of a question rather than the typical falling intonation of a statement. However, syntactically, these utterances remain declarative rather than interrogative. In English, its use is variable: Certain intonational phrases in declarative sentences may not exhibit it, as shown in example (1a), while others may incorporate a rising pitch, as in example (1b). In this instance, the term virus was identified using acoustic analysis software Praat with a pronounced HRT (Slobe Reference Slobe2018: 549). Under the sociolinguistic variationist framework (Labov Reference Labov1972b), the use of uptalk (i.e., [+ uptalk]) and nonuse of uptalk (i.e., [− uptalk]) can be regarded as variants of a single variable. In this Element, we refer to this variable as uptalk (2). In line with sociolinguistic literature, we use small caps (i.e., uptalk) to refer to “uptalk” as a sociolinguistic variable that encompasses use and nonuse of uptalk, and regular text (e.g., uptalk) to refer to the phenomenon of rising intonation, as illustrated in (2).

a. There is a pandemic that is rampant in this country∅

b. … and it’s the sexy baby vocal virus↑

(excerpt from the show Late Night with Conan O’Brien where voiceover actress Lake Bell was featured to promote her comedy film in 2013; uptalk indicated with ↑ while lack of uptalk with ∅; analysis done with Praat) (Slobe Reference Slobe2018: 549)

(2)

uptalk → [+ uptalk/HRT] → [− uptalk/HRT] or ∅

The uptalk variable has often been a subject of interest in English sociolinguistic research due to its association with gendered meanings. One of the earliest and perhaps most well-known identifications of this connection between gender and language was made by Lakoff (Reference Lakoff1973), whose work remains a foundational reference in sociolinguistics. She identified linguistic features such as uptalk and the use of empty adjectives as part of what she termed “women’s language,” an ideological construct that reflects societal expectations about how women should speak. Lakoff’s analysis, while based largely on introspection and folk-linguistic observation, was pioneering in its argument that women’s linguistic patterns emerge as a response to systemic power asymmetries. She posited that features such as hedging, tag questions, and politeness strategies are strategies for navigating male-dominated interactions. Although Lakoff’s work laid the groundwork for sociolinguistic research on gender, subsequent scholarship has moved beyond the dominance-based framework she outlined. Researchers have drawn on constructivist approaches, viewing gender as performative (Butler Reference Butler1988) rather than as a fixed social category with predetermined linguistic correlates. This perspective frames gender as emergent through iterative linguistic and social practices, including prosodic features like uptalk (Tyler Reference Tyler2015), challenging static notions of “women’s language” and emphasizing the role of discourse in the continuous reconstitution of gendered identities.

Researchers focusing on English within “Global North” (henceforth, Western)Footnote 1 contexts such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand have discovered that the use of uptalk can serve as a stylistic resource to convey femininity; however, they also found that it can carry other various social meanings, including politeness, inauthenticity, excessiveness, lack of intelligence, and informality, depending on the sociolinguistic context (see Section 2) (Britain Reference Britain1992; Kiesling Reference Kiesling2005; Levon Reference Levon2016, Reference Levon2020). Beyond indexing individual social meanings, the use of uptalk has been identified as a significant marker of solidarity between speakers and is used as a stylistic tool in constructing a gendered persona, that is, the “mock white girl persona” (Slobe Reference Slobe2018: 541), a persona where “gender” intersects and cannot be understood without notions of race (i.e., “White-ness”) and age (i.e., “young”), as well as class (i.e., “middle class”).

The findings of these scholars generally coalesce around two key ideas: First, there is no exclusive, direct one-to-one correspondence between uptalk (i.e., the use or nonuse of uptalk) and gender, and second, the set of social meanings in an “indexical field” (Eckert Reference Eckert2008: 453) – including gender-related ones – associated with uptalk varies based on cultural, community, and contextual factors. In essence, there appears to be no universally fixed set of (gendered) meanings attached to uptalk. Also, these meanings relate to and intertwine with each other in the varied performances of gender in society (e.g., the enactment of personae) (D’Onofrio Reference D’Onofrio2020). It is also understood that, like other gendered sociolinguistic variables such as the use of falsetto (Podesva Reference Podesva2007), the use of (ING) (Gratton Reference Gratton2016) (e.g., running vs. runnin’), or fronted /s/ (Calder Reference Calder2019: 31), uptalk can interact with other social factors, such as profession, the perceived safety of the environment, or the projection of specific personae like “fierce queen,” thereby acquiring different meanings and functions in diverse contexts (Podesva Reference Podesva2007; Calder Reference Calder2019).

Despite our increasing understanding of the nuanced, intersectional, and context-dependent nature of uptalk in recent years, its use and social implications remain relatively unexplored in “non-Western” contexts like Hong Kong. The gap prevents a comprehensive understanding of the variable uptalk in all of its social contexts and hinders one from fully understanding how gender operates linguistically in Hong Kong. To date and to our knowledge, the only relevant work in this geographic region is that of Cheng and Warren (Reference Cheng and Warren2005), which focused on general “rising tones” rather than exclusively on “uptalk” or rising pitch or rising terminals occurring at the end of intonation phrases. Their research indicated that rising tones were used to establish dominance and control and not gender, suggesting that uptalk may not inherently be tied to gendered speech patterns, as is often assumed in Western frameworks. There was no clear evidence that rising tones indexed femininity or masculinity, as speakers of all genders exhibited similar tone choices. Given that dominance and control were identified as exclusive functions of rising tones in their study, it is plausible that uptalk in Hong Kong may serve similar pragmatic functions, rather than being primarily linked to gender as often proposed in Western contexts.

However, a crucial question arises: What if we were to specifically and systematically examine rising tones at the end of intonational phrases, which, as mentioned in the sociolinguistic literature, have been associated with gender? If such rising tones do indeed carry gendered meanings, would we observe variations in their patterns and meanings within the unique cultural context of Hong Kong, where Chinese and Western influences intersect? Addressing these inquiries will offer one of the initial insights into the sociolinguistics of uptalk in Hong Kong, shedding light on the potential range of localized and gendered indexical meanings associated with this linguistic practice.

In this Element, our primary objective is to investigate the role of gender on prosodic stylistic variation of uptalk in “mainstream-style” Hong Kong English (henceforth, HKE), which we define here as the dominant form of English spoken in Hong Kong with influences from Cantonese. As will be detailed in the methodology section (Section 4), our initial approach draws from the first-wave Labovian variationist framework (Labov Reference Labov1972a), analyzing “gender” through predefined but self-identified groups. Specifically, in this Element we focus on “female”-identifying cisgender individuals who were assigned “female” at birth (henceforth, female)Footnote 2 and “male”-identifying cisgender participants who were assigned “male” at birth (henceforth, male), acknowledging, of course, the contentious nature of this binary classification in academia and beyond, recognizing it simplifies gender to mere biological distinctions. Nonetheless, we employ this classification as an initial comparative framework, consistent with some established sociolinguistic research methodologies. We recognize the importance of extending our analysis in future studies to include a more diverse array of gender identities. We also employ a constructionist paradigm that puts individual experiences and identifications at the center. In the context of Hong Kong (and particularly our set of participants), this approach requires us to engage with the highly hegemonic binary gender construct. This methodology not only facilitates easier dialogue with classical sociolinguistic research but also enables our research to be attuned with local cultural dynamics and individual preferences on gender expression.

To guide our investigation, we pose the following questions:

1. Is uptalk in HKE perceived to be gendered? If not, what is the range of social meanings attached to it, as observed in listener evaluations?

2. Does gender (i.e., speaker gender, listener gender, gender context/setting) condition the production of uptalk in Hong Kong, as previous research suggests? If not, what other factors affect or moderate its use?

3. To what extent are patterns observed in uptalk evaluation different from that of production? That is, could explicit/implicit awareness play a role?

2 Background

2.1 Social Constructionism and Accommodation

Our study primarily relies on social constructionism and accommodation theories to examine uptalk, a linguistic variable that has been observed to be gendered in many communities across the globe. In recent sociolinguistic research, scholars have predominantly embraced a postmodern perspective on language and its relationship with gender. This perspective neither characterizes gender as something that entails essential(ized) gendered qualities (i.e., women should use women’s language) nor presents it as a static outcome of early socialization (i.e., individuals socialized to be feminine will always grow up to be feminine) (Cameron Reference Cameron2003: 188). Instead, gender is something that is dynamically constructed and negotiated through social interactions with meaning-laden linguistic and semiotic resources. Language, along with other semiotic resources (e.g., hairstyle, clothing), can be agentively used to convey or shape one’s gendered identit(ies) or enact gendered persona(s) in social interactions (Section 2.2), which coalesce to form the notion of “gender” we know today (Eckert Reference Eckert1989, Reference Eckert2008). An illustrative instance of a gendered linguistic resource is uptalk, which has been observed to have indexical values related to tentativeness and uncertainty, which can then be further linked to femininity (Warren Reference Warren2015).

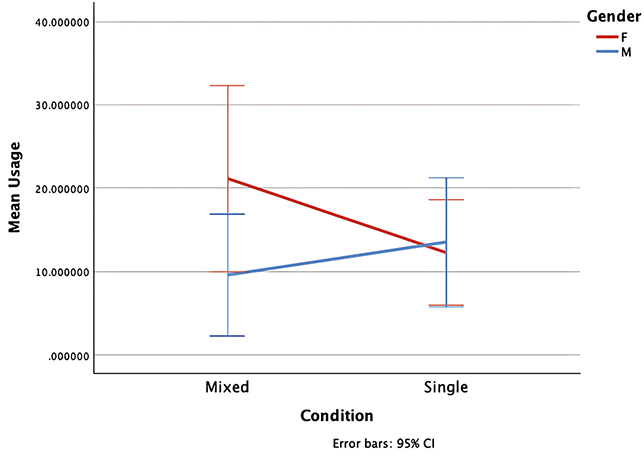

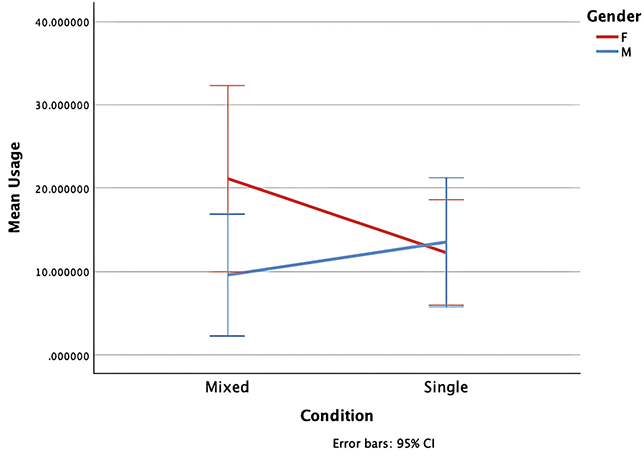

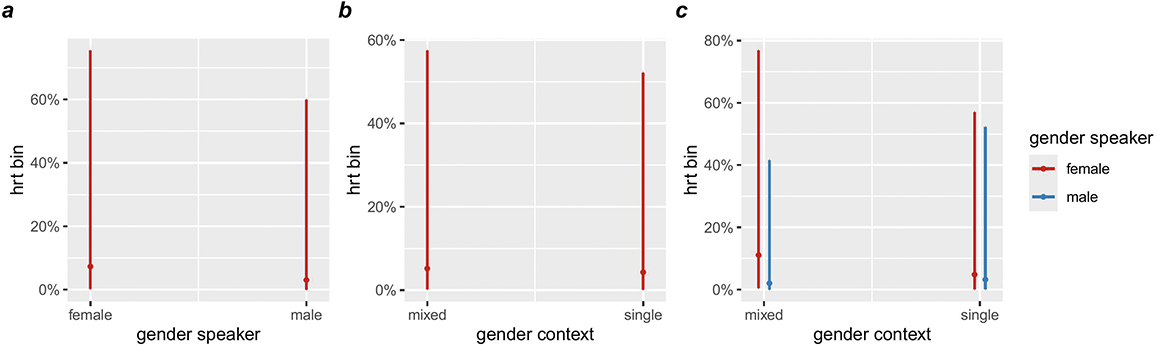

In addition to social constructionist theories, this study draws on communication accommodation theory (CAT) (Giles Reference Giles2016: 36) to examine stylistic variation. Communication accommodation theory posits that speakers modulate their speech in response to audiences by converging, diverging, or maintaining their linguistic patterns. This theoretical framework is particularly relevant given prior research demonstrating accommodation-like effects in studies of uptalk. Though not arguing for an accommodation approach, Levon’s (Reference Levon2016) study in London provides critical insights into the variable and accommodation-like use of HRT by men and women in mixed-gender interactions. Men exhibit a higher frequency of HRT use in mixed-sex conversations compared to single-sex conversations, employing the feature as a discursive strategy to assert interactional presence and engagement. Rather than reflecting traditional accommodation to female interlocutors, men’s use of HRT was found to serve to consolidate their participation and maintain interactional salience. In contrast, women deploy HRT primarily as a mechanism for managing conversational control and mitigating potential disagreement. Their use of HRT is thus less indicative of accommodative convergence and more reflective of strategies aimed at sustaining interactional harmony (Levon Reference Levon2016: 157). These findings suggest that linguistic adaptation is shaped not merely by convergence toward the interlocutor’s speech patterns but also by broader interactional and social considerations. The patterns observed in London may be indicative of similar processes in other mixed-gender sociolinguistic settings, such as those in Hong Kong.

2.2 Gender Identity and Gendered Personae in Hong Kong

Scholars have identified diverse gender identities and gendered personae in Hong Kong society, reflecting the presence of a wide range of ways in which gender manifests in Hong Kong. Before delving into how “gender” is realized in Hong Kong, it is worth discussing “identity” and “persona” and the relationship between them.

Scholars have viewed identity as a distinct construct with psychological underpinnings (Kish Bar-On & Lamm Reference Bar-On, Kati and Lamm2023), frequently operationalized as being related to one’s subjective understanding of self, group membership, and social positioning (Cruwys et al. Reference Tegan, Steffens, Haslam, Haslam, Jetten, Jolanda and Dingle2016). It has been conceptualized as an “emergent product rather than the pre-existing source of linguistic and other semiotic practices and therefore as fundamentally a social and cultural phenomenon” (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2005: 587). Thus identity categories are not seen as fixed entities but rather as necessarily dynamic constructs that evolve through consistent practice and are shaped by changing sociohistorical and ideological contexts (Haas, Jones, & Fazio Reference Haas, Jones and Fazio2019).

Identity is often differentiated from “personae,” which are the social roles or facades that individuals adopt and perform in different situations or specific group settings. Agha (Reference Agha2003) defines a persona as a social construct associated with distinct linguistic registers, styles, or manners of speaking. A persona embodies a way of being and acting that transcends mere social identity, manifesting as either an imagined or actual character (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2017). In this context, personae are not direct reflections of individual identities or “selves” but rather serve as “characterological touchstones” (D’Onofrio Reference D’Onofrio2020: 11) that individuals can adopt, modify, or discard as needed in various situations, such as the roles of “diva” or “fierce queen” (Podesva Reference Podesva2007; Calder Reference Calder2019).

In contemporary sociolinguistic variationist research, identity is often described as ideologically interconnected with the concept of “persona.” From this perspective, “identity” is considered a broader term that includes or is constituted by various social personae. These personae are interactional constructs that individuals use to conduct recognizable identity work within their social interactions; they are necessarily specified for macrosocial information like race, place of origin, age, class, sexual orientation, and of course gender (D’Onofrio Reference D’Onofrio2020). The concept of “persona” broadens our understanding of social interactions beyond just macrosocial categories, local affiliations, or psychological constructs of (self-)identities.

Relating language and language variation to these notions, the idea is that any association of the use of linguistic variables with gender (e.g., uptalk with femininity) is mediated by interactional personae like the “Valley Girl,” and broader notions of femininity emerge from the ways in which these personae become “ideologically linkable with macro-social categories through interactional use” (D’Onofrio Reference D’Onofrio2020: 7).

In the Hong Kong context, studies of language in relation to macrosocial gender “identity” are limited compared to Western studies. These studies tend not to put emphasis on (micro)language variables, focusing instead on (general) gender itself. These studies all agree that gender identities in Hong Kong result from an ongoing negotiation between societal “Chinese” and “local” gender norms and individual self-perception. For instance, Kam (Reference Kam2003) demonstrated in Hong Kong that self-identifying masculine women can reshape and redefine womanhood without necessarily abandoning it in favor of masculinity.

The discussion of gender identity in Hong Kong would certainly not be complete without discussing gendered personae in the region. Unlike local work on gender identity, work on gendered personae has placed more emphasis on the role of language. One of the most prominent local gendered personae is the gong neoi “Kong Girl” persona, derived from “Hong Kong Girl.” While the Kong Girl persona originally referred to women in Hong Kong neutrally, it has acquired a negative connotation over time, becoming synonymous with being “materialistic, narcissistic, and demanding” (Chen & Kang Reference Chen and Kang2015: 194). This persona has evolved into a stereotype recognized through both nonlinguistic traits like an obsession with food photos and linguistic features such as a higher pitch, code-switching between Cantonese and English, and excessive use of /r/ sounds (Chen & Kang Reference Chen and Kang2015).

In summary, research on macrosocial gender “identities” and gendered personae in Hong Kong highlights the use of various semiotic resources in constructing them, revealing indexical links between language variables (e.g., code-switching and /r/) and social meanings such as entitlement and shallowness, which are then ideologically linked to femininity or “womanhood” via widely recognized and media-moderated personae such as “Kong Girl.”

2.3 Gender and Language in the Hong Kong Context

Previous studies in Hong Kong have explored the relationship of gender with linguistic features, such as hedges, refusal strategies, and code-mixing. Wong (Reference Wong2006), for example, found that hedges were more frequently used by female speakers, attributing this to women’s expected role in maintaining conversational solidarity. Wong (Reference Wong2018) studied how Hong Kong Chinese EFL learners made refusals in English, revealing that men and women employed different strategies. Men tend to use a combination of both direct and indirect strategies when making refusals. Women, on the other hand, mostly use indirect strategies only for refusing. Schnurr and Mak (Reference Schnurr and Mak2011) analyzed real-life workplace interactions and found that female leaders often used both feminine and masculine speech styles to navigate a male-dominated environment: They often display masculine leadership styles, such as directness and authority, while incorporating feminine elements like a soft tone of voice and inclusive language (e.g., “we” instead of “I”) to mitigate the impact of their directives. Wong (Reference Wong2004) reported that female Cantonese–English bilingual speakers used more code-mixing, especially with female interlocutors.

However, these studies have faced limitations. Some, like Wong (Reference Wong2006) and Wong (Reference Wong2018), did not effectively disentangle the influence of gender from that of gender settings, potentially muddling the source of linguistic variations. Wong (Reference Wong2018) found that participants’ native languages (e.g., Cantonese, Japanese) may have affected their language strategies, introducing potential confounding factors. Furthermore, participants’ gender imbalances, as seen in Wong (Reference Wong2018), may result in skewed data, raising questions about the representativeness of the findings.

This Element aims to overcome these limitations by ensuring an equal representation of genders and a balanced number of participants, while also controlling for variables like language backgrounds and social status.

2.4 Uptalk in Hong Kong and Beyond

The variable uptalk has garnered considerable interest in sociolinguistic research, with studies revealing diverse social connotations attributed to uptalk across various contexts.

In the context of Porirua, New Zealand, Britain (Reference Britain1992) found that the use of uptalk was favored by young Māori and young Pakeha women, suggesting that uptalk had acquired social meanings associated with youth, Māori ethnicity, Pakeha ethnicity, and femininity. Slobe (Reference Slobe2018) investigates parody performances of the “mock white girl” persona in the United States. The research identified uptalk as one of the semiotic resources used in stylizing the persona, along with features like creaky voice, blondeness, and going to Starbucks. The study found that exaggerated use of uptalk rendered the style excessive and inauthentic. Uptalk in this context was associated with whiteness, femininity, and the performance of inauthenticity and excessiveness. The findings highlighted the diverse interpretations and associations individuals make with the use of uptalk.

In the context of Hong Kong, uptalk has not been directly explored. The closest work is that of Cheng and Warren (Reference Cheng and Warren2005), who conducted corpus analyses on the use of rising and rise-fall tones in Hong Kong, focusing on HKE and Chinese. Their study found that intonation was influenced by discourse type and designated roles of speakers. Rising tone was found to be almost ten times more frequent among supervisors than supervisees. The use of rise-fall tones was infrequent but occurred more frequently in supervisor–supervisee interactions, particularly when discussing unclear topics. Rising tone (which we interpret as being inclusive of uptalk) in the HKE context was perceived as asserting dominance and control, with no salient gendered meanings observed. Speakers regardless of gender exhibited similar behavior in terms of their uptalk rates in the data investigated.

In addition to the social meanings and confounding factors identified in previous studies, the current study also speculates that one’s “explicit awareness” of uptalk influences their use and interpretation of the variable. The notion of “explicit awareness” follows Labov’s conception of “attention paid to speech” (Labov Reference Labov1972a), which states that linguistic style shifts can occur when speakers’ attention is drawn to them. For example, in his work, Labov directed the participants’ attention to the pronunciation of “ten.” The results showed that by making the participants more aware of the location of their tongue, participants were more aware of articulation and replied with more casual answers, showing that awareness could lead to style shifts. As such, the current study takes participants’ awareness of uptalk into consideration when evaluating their usage and interpretation of the variable. This will be discussed in depth in Section 5.2.

Overall, the works reviewed demonstrate that the social meanings associated with uptalk vary across different cultural and linguistic contexts. While some social meanings, such as youth and femininity, tend to appear somewhat consistent for specific regions, other indexical meanings of uptalk seem to be activated in various degrees depending on the community and cultural norms. They suggest that further research is needed to get a more nuanced understanding of uptalk’s social meaning(s) in specific regions and communities.

3 Hypotheses

This Element proposes the following hypotheses regarding uptalk in HKE, motivated by prior sociolinguistic work and research questions, which are discussed in Section 2.

H1. The use of uptalk will predominantly convey “feminine” connotations or meanings that could be ideologically linked and interpreted as “feminine.” It will also have other meanings that are not necessarily related to gender (e.g., informality).

H2. Gender will affect the production of uptalk. That is, women will use uptalk more frequently than their male counterparts. Gender will interact with other social or “extralinguistic” factors to condition uptalk. The link between uptalk and gender will be mediated/moderated by other macrosocial factors (e.g., ethnicity).

H3. In conditions where speakers are explicitly aware of uptalk, at least some speakers of HKE will attribute “feminine” meanings to it. uptalk will be mobilized differently in various gender contexts, for example, when conversing with individuals of the same gender compared to those of another gender.

4 Methodology

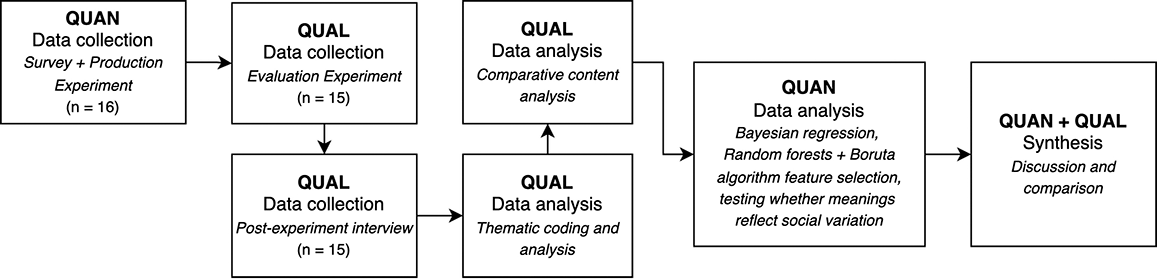

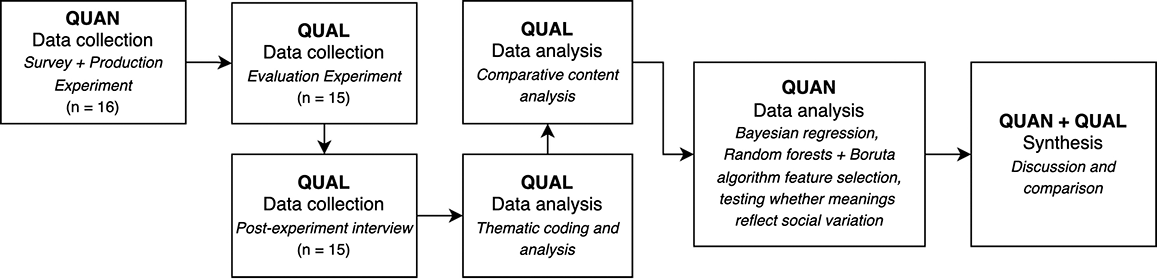

A mixed-methods approach was used to gain a more nuanced understanding of uptalk in Hong Kong. Our methodology utilized a sequential design, commencing with the collection of quantitative evidence via a production experiment (Section 4.1) (Figure 1). Subsequently, we conducted an evaluation experiment (Section 4.1.4) followed by postexperiment interviews to gather qualitative data (Section 4.1.5). These qualitative data were later subjected to thematic coding and comparative content analysis (Section 4.2). The insights gleaned from this qualitative analysis (Sections 5.1 and 5.2) informed our statistical analysis of the quantitative data in Section 5.3, where we used both Bayesian regression analysis and random forests analysis complemented by a Boruta feature selection algorithm.

Figure 1 Procedural diagram of research activities in this sequential mixed-methods study.

We will use both quantitative and qualitative data to examine all three hypotheses.

To ensure the integrity of our study, we strategically conducted quantitative data collection (i.e., production experiment) prior to qualitative data collection. This sequencing aimed to minimize speaker awareness and attention to speech, which have been found to influence speech patterns (Labov Reference Labov1972a; Bell Reference Bell1984). The rationale behind this approach is that in the last part of the qualitative data collection (i.e., postexperiment interview), we explicitly conveyed the study’s objectives and asked participants to evaluate uptalk, making participants aware of the variable of interest. Furthermore, in the first part of the qualitative data collection – the evaluation experiment – we asked participants to evaluate sentences that either have uptalk or not. Although we did not inform them that these sentences contain uptalk, the limited number of stimuli and lack of fillers could potentially prompt participants to be nevertheless aware of uptalk, biasing the study as well. As such, we decided to conduct the (quantitative) production experiment before the two qualitative data collection sessions (i.e., evaluation experiment and interview). Had we conducted the interviews and evaluation experiment before the production experiments, participants might have adjusted their speech patterns based on this knowledge, introducing bias into the study.

The order of data analysis was also strategic: By conducting qualitative analysis before quantitative analysis, we aimed to gain insights into the factors to incorporate into our statistical modeling. Additionally, we sought to test whether the social meanings inferred from the evaluation experiment and interviews aligned with the social variation patterns observed in the production experiment data.

The entire protocol was vetted and approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board equivalent) of a public university in Hong Kong (SBRE‐22‐0753). This step was done to ensure that our study conforms to ethical standards in sociolinguistic research.

4.1 Data Collection

4.1.1 Participants

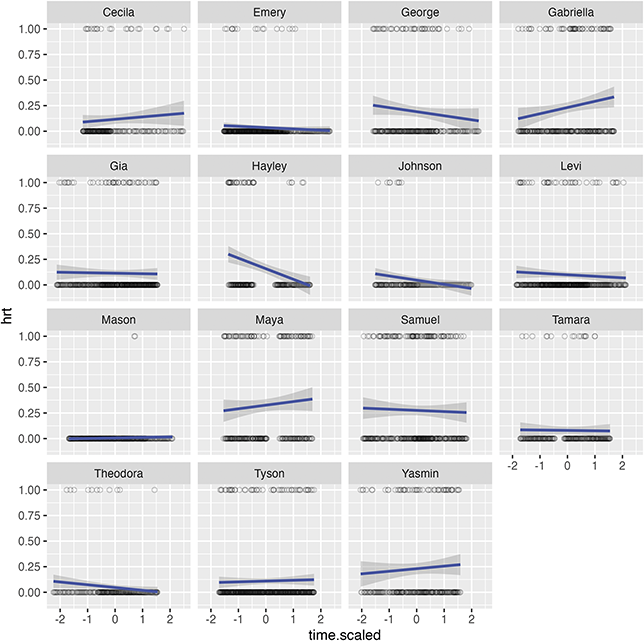

We recruited sixteen undergraduate students from Hong Kong to partake in our study, focusing on the impact of gender on uptalk within this specific setting through an experimental lens. As such, our methodology was influenced primarily by the first-wave Labovian variationist approach (Labov Reference Labov1972a), aiming to categorize “gender” into predefined groups. To determine participant groupings, we first conducted a preliminary survey with twenty-three individuals who had expressed interest in the study. Rather than using the common fixed-response format of “male, female, other” – which risks biasing participants toward binary categories and potentially marginalizing or “othering” nonbinary identities – we employed an open-ended question: What gender do you identify as? This approach allowed us to avoid assumptions about participants’ gender identities and ensure that their self-reported categories guided our grouping decisions. All respondents identified as either “male” or “female.” Based on these data, we randomly selected an equal number of participants from each of these two groups, centering our analysis on the predominant gender distinction that emerged within our participant pool: “male” versus “female.” We acknowledge the contentious nature of this binary classification in academia and beyond, recognizing it simplifies gender to mere biological distinctions. Despite the complexity of gender and sex beyond simple binaries (Sauntson Reference Sauntson2019), this goal of this study is to first establish foundational insights for subsequent research on gender and language in the HKE-speaking context. Our primary questions include whether binary gender influences uptalk and its association with perceived femininity or masculinity, aiding in future explorations of the dynamics between normative and nonnormative gender categories and uptalk. We also want to emphasize that, in Hong Kong, the concept of gender is still highly heteronormative, intertwined with conservative Chinese ideologies and culture that enforce such a binary (Liong Reference Liong2010). All sixteen participants, even with the option to identify outside the “male” or “female” categories, chose to identify within them. Adopting a grounded theoretical approach (Glaser & Strauss Reference Glaser and Strauss2017), we respected the participants’ self-identification. Overall, we found eight “female”-identifying cisgendered participants who were assigned “female” at birth (henceforth, female) and eight “male”-identifying cisgendered participants who were assigned “male” at birth (henceforth, male).

Although we do not anticipate that the university attended by the speakers would affect their usage of uptalk, we took precautions by balancing our data: Four males and four females were selected from one university (The Chinese University of Hong Kong), with the remaining participants chosen from another university (The University of Hong Kong). All the participants we recruited were aged between eighteen and twenty-five, a measure to account for potential impacts of generational shifts or educational backgrounds.

A combination of snowball and purposive sampling methods was employed for recruitment, drawing participants from our social networks. Some of these individuals were acquainted with one another, while others were strangers. Our deliberate decision to include participants with varying degrees of familiarity was motivated by our intention to investigate its potential influence on uptalk as a factor in our data analysis.

4.1.2 Survey

After participants were briefed on the procedure and provided their consent, they were tasked with filling out a sociolinguistic survey. This survey aimed to gather various social information that we expected would condition the use of uptalk, based primarily on our review of the sociolinguistic literature. The metadata we gathered in the survey include socioeconomic status (1 to 7, continuous), age (continuous), gender identity (i.e., “male,” “female,” “other,” categorical), ethnic identity or ethnicity (degree of Chinese orientation, continuous), and self-reported English proficiency (1 to 7, continuous).

The goal was to gather as much social metadata as possible prior to conducting the experiments and interviews. From this extensive list, we would later select specific factors, like those enumerated previously, to include in our quantitative analysis. Our decision on which factors to include in the analysis was informed by insights gained from the qualitative analysis of the evaluation experiment and the postexperiment interviews. For example, if the interviews mentioned English proficiency, then the data related to English proficiency would be extracted from the survey data and linked to the production experiment data for confirmatory analysis. This selection process would help us determine whether our qualitative findings aligned with potential patterns of social variation observed in the production experiment. However, recognizing that some meanings of uptalk may not be in the explicit awareness of speakers and thus not surface in the qualitative interviews and evaluation experiments, we also included social factors gathered from our survey that may implicitly influence uptalk (e.g., age, class, stylistic formality) and interact with gender to condition uptalk (Eckert Reference Eckert1989), based on previous English studies on sociolinguistic variation.

Overall, the collection of sociolinguistic metadata through a survey enabled us to explore the relationship between uptalk, gender, and other factors, helping us get a more nuanced understanding of the uptalk phenomenon. The sociolinguistic metadata from the survey will be used to supplement the qualitative analysis of uptalk evaluation, but it will be linked to the production experiment data (Section 4.1.3) and primarily used to derive (sociolinguistic) factors for the quantitative analysis or modeling of likelihood of uptalk production.

4.1.3 Production Experiment

This experiment aims to gather data that can help us understand the relationship between gender and uptalk in language production and pinpoint the role(s) of other nongender social factors in the production of uptalk, examining to what extent these nongender factors directly influence the use of uptalk and to what extent they mediate or moderate how gender conditions uptalk. We operationalize “gender” in this experiment as “speaker gender” and “gender context,” attempting to examine whether the speakers’ gender and the gender context condition uptalk. “Gender context” was integrated into the design of the experiment in order to test the last hypothesis – to find potential evidence of gender-driven stylistic speech accommodation or the (agentive) use of uptalk in various gender settings (i.e., single-gender vs. mixed-gender settings).

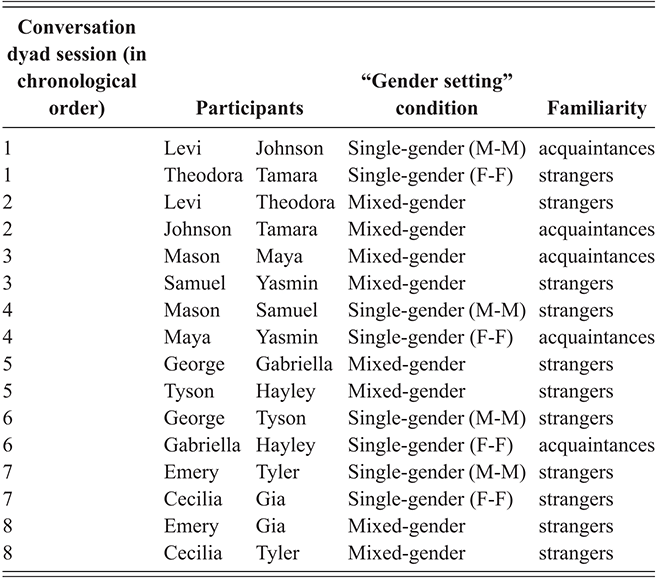

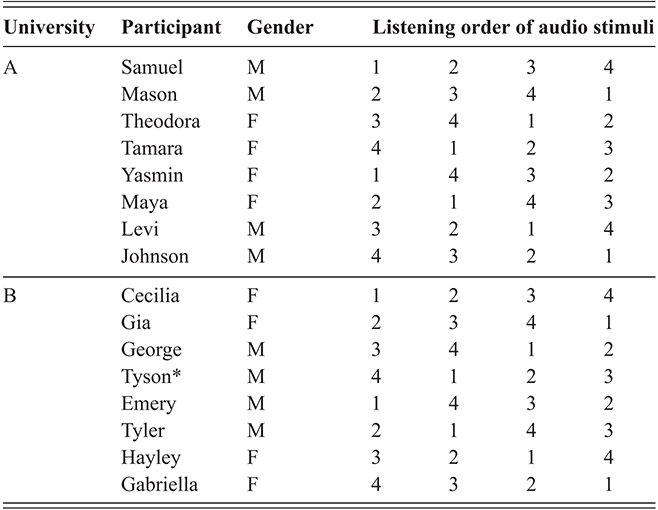

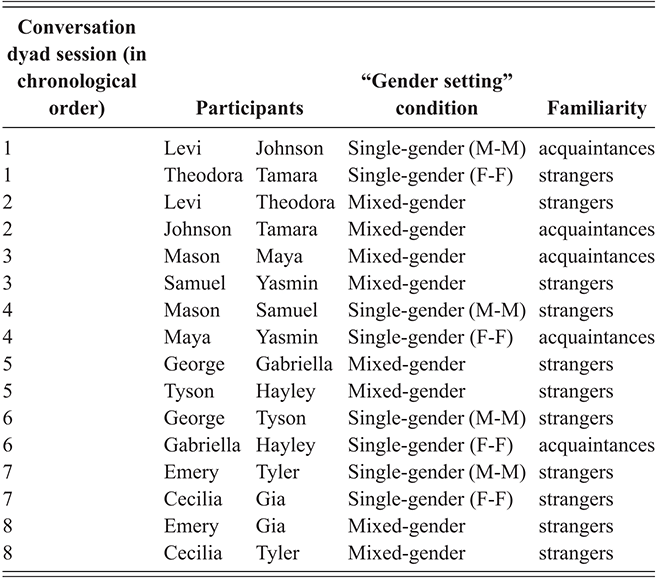

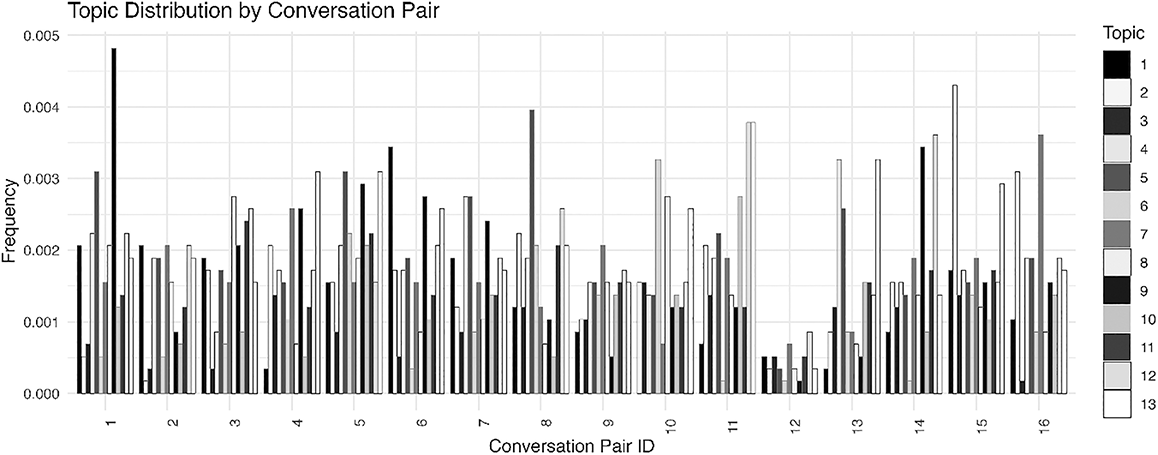

Prior to the experiment proper, we randomly assigned sixteen participants into eight single-gender (comprising male-male or female-female pairs) and eight mixed-gender pairs, forming sixteen conversation dyads (consisting of male-female pairs) (see Table 1). Each of the sixteen participants underwent both gender setting conditions, to enable us to make causal inferences. The numbers of male-male (n = 4) and female-female dyads (n = 4) within the single-gender dyads were equal. Given our focus on the effects of familiarity on the use of uptalk, we sought to balance dyads in terms of acquaintance versus stranger status during participant pairing. However, given the priority placed on controlling for gender, the final dyads pairing exhibited some imbalance in familiarity distribution, resulting in five dyads composed of strangers and eleven dyads composed of acquaintances (Table 1). Despite this limitation, diagnostic analyses indicate that our model remains robust. Specifically, the effective sample size (ESS) of 3,944 suggests that our posterior samples provide sufficient independent draws for reliable inference, while an R-hat value of 1 confirms that our Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm has successfully converged despite the imbalance. These diagnostics affirm the model’s stability and the validity of our estimates. Thus, while the dataset is not ideally balanced by familiarity, it nonetheless provides a strong empirical foundation for investigating the relationship between social familiarity and the use of uptalk.

Table 1.Long description

The participants were sorted into 16 dyads. The sessions are by chronological order.1. In session 1, Levi and Johnson took part in a single-gender (M-M) condition. They were acquaintances.2. In session 1, Theodora and Tamara took part in a single-gender (F-F) condition. They were strangers.3. In session 2, Levi and Theodora took part in a mixed-gender (M-F) condition. They were strangers.4. In session 2, Johnson and Tamara took part in a mixed-gender (M-F) condition. They were acquaintances.5. In session 3, Mason and Maya took part in a mixed-gender (M-F) condition. They were acquaintances.6. In session 3, Samuel and Yasmin took part in a mixed-gender (M-F) condition. They were strangers.7. In session 4, Mason and Samuel took part in a single-gender (M-M) condition. They were strangers.8. In session 4, Maya and Yasmin took part in a single-gender (F-F) condition. They were acquaintances.9. In session 5, George and Gabriella took part in a mixed-gender (M-F) condition. They were strangers.10. In session 5, Tyson and Hayley took part in a mixed-gender (M-F) condition. They were strangers.11. In session 6, George and Tyson took part in a single-gender (M-M) condition. They were strangers.12. In session 6, Gabriella and Hayley took part in a single-gender (F-F) condition. They were acquaintances.13. In session 7, Emery and Tyler took part in a single-gender (M-M) condition. They were strangers.14. In session 7, Cecilia and Gia took part in a single-gender (F-F) condition. They were strangers.15. In session 8, Emery and Gia took part in a mixed-gender (M-F) condition. They were strangers.16. In session 8, Cecilia and Tyler took part in a mixed-gender (M-F) condition. They were strangers.

Each member of the sixteen dyads was instructed to engage in discussions on any topic they wanted in a quiet room, specifically, designated rooms within university libraries. Half of the participants began with the single-gender dyad conversations, where they conversed with someone of the same gender, and then proceeded to engage in mixed-gender dyad conversations with someone of another gender. The other half of the participants followed the reverse order, starting with mixed-gender dyads. This sequencing was implemented to control for potential blocking order effects.

Each participant completed both single-sex and mixed-sex dyad conversations within the same day. Each dyad conversation lasted for roughly thirty minutes and was audio-recorded using recorders with a sampling rate of 44,100 Hz, which allowed us to conduct acoustic analyses (Section 4.2). During the conversations, the facilitator(s) intentionally removed themselves from the room to mitigate the observer effect.

In summary, the dyads followed the organization detailed in Table 1.

4.1.4 Evaluation Experiment

This experiment attempted to probe the social evaluations and, consequently, meanings that English speakers in Hong Kong implicitly associate with uptalk. Although we recognize that gender intersects with other social structures (e.g., class, age), for this experiment, we attempted to simplify the experiment design and simply focused on setting up the experiment to gauge or “isolate” the conditioning effect(s) of gender on (non)gendered attitudes or evaluations toward uptalk. In the production experiment, gender was operationalized as “gender setting” and “speaker gender.” However, in this evaluation experiment, gender was operationalized as “listener/evaluator gender” and “speaker gender.”

To investigate whether there are gender-based differences in uptalk interpretations, we addressed the question of (1) whether male listeners attribute different social meanings to uptalk compared to female listeners (i.e., “listener gender”), and (2) whether listeners attribute different social meanings to uptalk by male speakers compared to female speakers (i.e., “speaker gender”). In recognition of the complexity of “gender,” we also explored the potential interactions between the gender of the listener/evaluator and the gender of the speaker. Specifically, we compared how male listeners rate male speakers versus female speakers. Similarly, we examined how female listeners rate male speakers in contrast to female speakers.

Following the production experiment, the same participants were invited to take part in a recorded session via Zoom. The same participants were invited to enable us to maintain consistency in the data and to allow for a direct comparison between the production and evaluation data of this study. During the evaluation experiment session, each participant was presented with all four recorded audio stimuli once. In cases where the audio was unclear, participants were allowed to request a replay. Following exposure to each stimulus, participants were instructed to provide detailed, descriptive accounts of the speaker. This was inspired by the matched-guise experimental procedure in sociolinguistic variation studies (Mallinson, Childs, & Van Herk Reference Mallinson, Childs and Van Herk2017). Unlike the matched-guise paradigm, in which participants rate filler or distractor stimuli to obscure the primary research focus by presenting speech as originating from multiple speakers, this experiment employed a more streamlined design. Participants were asked to evaluate only the target stimuli from two speakers, a decision made to mitigate participant fatigue, which had been a significant issue in our pilot study conducted one month prior. Despite the absence of filler stimuli, postexperimental informal interviews revealed that participants were largely unaware that the study focused on uptalk. Instead, they believed they were assessing speaker attributes, and notably, they did not realize that the stimuli were produced by only two speakers. Evidence of this lack of awareness emerged in the participant’s choice of wording. Rather than specifying “he/she is trying to say the same line four times” or “both of them are trying to say the same line,” the participant instead employed the term “all,” inaccurately suggesting the presence of more than two speakers when only two were involved.

(3) I think all of them are trying to say the same line. They recall for this purpose of meaning. Okay, yeah. (Mason)

This suggests that the experimental design effectively maintained the intended level of perceptual naturalness and minimized potential demand characteristics.

Specifically, participants were instructed to infer aspects of the speaker’s personality, mood, ethnicity, social class, and other relevant characteristics based on the audio stimuli. This approach was chosen over directly asking participants their feelings upon hearing the stimuli, based on pilot test results indicating that participants struggled with direct evaluations but found it easier to assess the speaker. Unlike classical language attitude studies that rely on adjective-based Likert scales for speaker evaluation (Campbell-Kibler Reference Campbell-Kibler2010), we adopted an open-ended approach, allowing participants to provide spontaneous commentary rather than selecting from predetermined descriptors. This method minimizes bias and captures a broader spectrum of social meanings, including those that may operate below the level of explicit awareness.

We can conclude that the evaluations were influenced by uptalk, not the content of the sentence, since all stimuli contained identical text:

I think there is no inherent meaning in life, because humans are not tools like cups or tables, we are not born to serve a specific purpose.

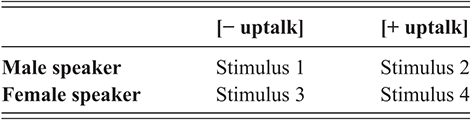

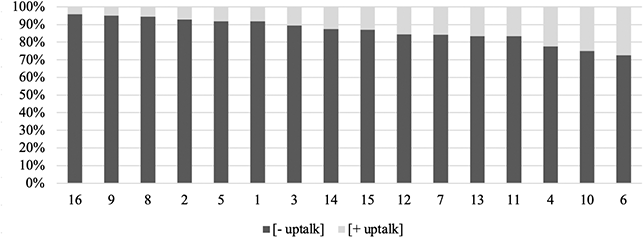

Among these stimuli, two included uptalk at the ends of intonational phrases, occurring in the words life and purpose (stimuli 2 and 4), while the other two did not exhibit uptalk in these locations (stimuli 1 and 3). To ensure that the stimuli were representative of HKE, they were presented to two native speakers of HKE, who confirmed their acceptability as characteristic of the variety.

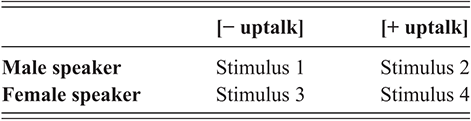

To account for potential speaker gender effects, two sets of stimuli were created for the [+ uptalk] and [−uptalk] conditions. Half of the stimuli were produced by a young female-identifying speaker of HKE (stimuli 3 and 4), while the other half were produced by a young male-identifying speaker of HKE (stimuli 1 and 2) (see Table 2). Both speakers were in their early twenties, identified as native speakers of a “mainstream” variety of HKE, and shared similar socioeconomic and linguistic backgrounds. They were proficient in Cantonese, Standard American English, and HKE.

Table 2.Long description

1. Stimuli 1: Male speaker, [- uptalk]2. Stimuli 2: Male speaker, [+ uptalk]3. Stimuli 3: Female speaker, [- uptalk]4. Stimuli 4: Female speaker, [+ uptalk]

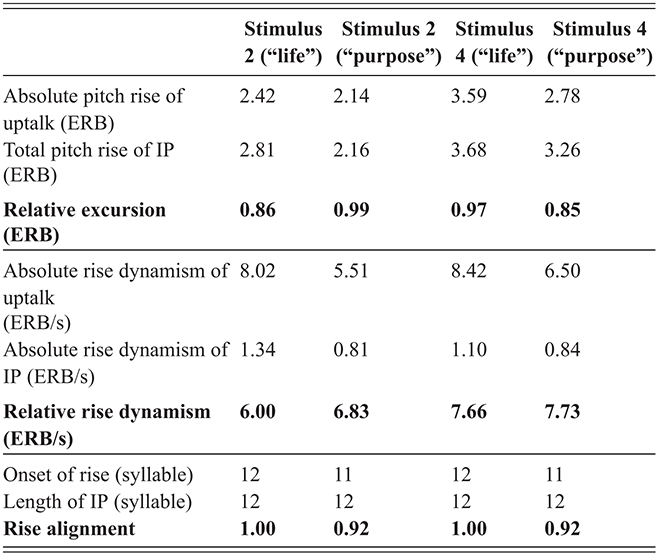

The phonetic properties of the [+ uptalk] stimuli were analyzed according to Levon’s (Reference Levon2020) protocol, and were shown to be kept consistent (Table 3). Relative excursion indicates the degree of pitch rise in relation to the entire intonational phrase (IP). It is measured by taking the difference between the F0 at the highest point of the rise IP and the F0 at the onset of the rise elbow, which is the point that shows a clear upward trajectory of the pitch contour. The absolute difference is then divided by the highest and lowest F0 of the entire IP. In addition to relative excursion, rise dynamism and rise alignment were also measured. Rise dynamism is the degree of pitch rise in relation to time, while rise alignment is calculated by dividing the syllable in which the uptalk begins with the total number of syllables in the IP.

![The table shows the phonological properties of [+uptalk] stimuli in ERB (Equivalent Rectangular Bandwidth), including the pitch rise, relative excursion, rise synamism, and rise alignment. See long description.](https://static.cambridge.org/binary/version/id/urn:cambridge.org:id:binary:20260216040009705-0144:9781009634083:63404tbl1_3.png?pub-status=live)

Table 3.Long description

1. For Stimulus 2 (“life”), the absolute pitch rise of uptalk is 2.42 ERB, the total pitch rise of IP is 2.81 ERB, the relative excursion is 0.86 ERB, the absolute rise dynamism of uptalk is 8.02 ERB/s, the absolute rise dynamism of IP is 1.34 ERB/s, the relative rise dynamism is 6.00 ERB/s, the onset of rise is 12 syllables, the length of IP is 12 syllables, and the rise alignment is 1.00.2. For Stimulus 2 (“purpose”), the absolute pitch rise of uptalk is 2.14 ERB, the total pitch rise of IP is 2.16 ERB, the relative excursion is 0.99 ERB, the absolute rise dynamism of uptalk is 5.51 ERB/s, the absolute rise dynamism of IP is 0.81 ERB/s, the relative rise dynamism is 6.83 ERB/s, the onset of rise is 11 syllables, the length of IP is 12 syllables, and the rise alignment is 0.92.3. For Stimulus 4 (“life”), the absolute pitch rise of uptalk is 3.59 ERB, the total pitch rise of IP is 3.68 ERB, the relative excursion is 0.97 ERB, the absolute rise dynamism of uptalk is 8.42 ERB/s, the absolute rise dynamism of IP is 1.10 ERB/s, the relative rise dynamism is 7.66 ERB/s, the onset of rise is 12 syllables, the length of IP is 12 syllables, and the rise alignment is 1.00.4. For Stimulus 2 (“purpose”), the absolute pitch rise of uptalk is 2.78 ERB, the total pitch rise of IP is 3.26 ERB, the relative excursion is 0.85 ERB, the absolute rise dynamism of uptalk is 6.50 ERB/s, the absolute rise dynamism of IP is 0.84 ERB/s, the relative rise dynamism is 7.73 ERB/s, the onset of rise is 12 syllables, the length of IP is 11 syllables, and the rise alignment is 0.92.

The speakers were instructed to produce each stimulus six times (i.e., three times with uptalk and three times without) while maintaining a “mainstream” HKE accent. When productions did not meet the experimental criteria, coaching was provided, and retakes were required until satisfactory stimuli were obtained. Once candidate stimuli were produced, a single exemplar was selected for each condition (uptalk and nonuptalk) per speaker, resulting in a total of four finalized stimuli. The selection process involved consultation with the two HKE speakers mentioned earlier, who were knowledgeable about the phonetic characteristics of the variety.

To enhance experimental control while maintaining a natural and realistic quality (ecological validity), the focus syllables (i.e., those with or without uptalk) were extracted and spliced onto the alternate version produced by the same speaker. This process was designed to minimize extraneous variation while preserving the natural quality of the speech samples. While we recognize the importance of factors such as the rate of pitch rise (F0), onset of pitch rise, and other prosodic parameters in studies of uptalk such as “rise dynamism” (Levon Reference Levon2020: 49), we opted not to manipulate these features explicitly. Initial efforts to control for these variables across gendered stimuli in a pilot study yielded stimuli that listeners characterized as “unnatural” and “robotic,” thereby introducing potential confounds rather than enhancing experimental control. Consequently, we opted not to impose strict controls on these prosodic variables, particularly given that the two [+ uptalk] stimuli were controlled to already examine gender effects. For example, prior research (Levon Reference Levon2020) has demonstrated that fundamental differences exist between women’s and men’s average F0 levels, underscoring the challenge of achieving perfect control without inadvertently influencing listener evaluations. Our pilot study further corroborated this concern, indicating that attempts to equate F0 levels across gendered stimuli may themselves introduce perceptual artifacts, ultimately undermining the validity of the experimental design.

Given that this is an exploratory study, our primary objective is to lay a foundation for understanding the role of familiarity in uptalk use while maximizing ecological validity. Accordingly, inspired by Levon (Reference Levon2020), we prioritized the preservation of naturally occurring speech patterns by gender over the imposition of rigid prosodic controls across gender, ensuring that our analysis captures speech as it is authentically produced in interaction. While this choice introduces interpretive complexity (e.g., different interpretations of uptalk), particularly as perceptual responses may be influenced by variation in F0 across stimuli, it reflects a commitment to ecological validity. This trade-off is an inherent consideration when working with spontaneous speech data. We expect that future complementary research would investigate the role of controlled prosodic manipulations in shaping listener evaluations, an important yet distinct line of inquiry beyond the scope of this Element.

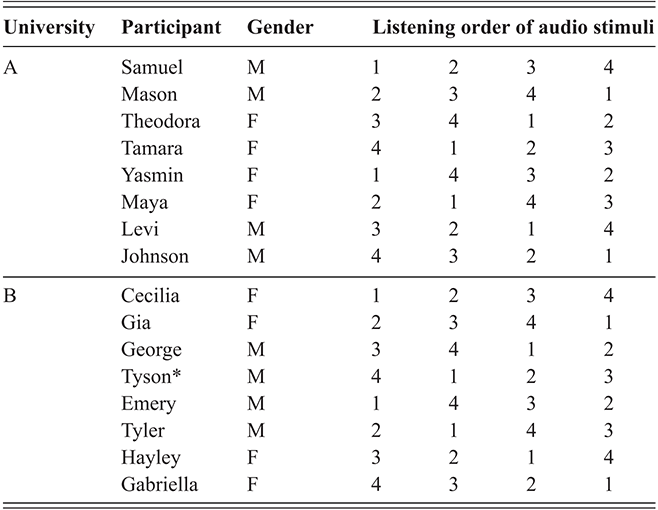

To control for the carryover effect and order effect in the evaluation process, a Latin square design was employed in the presentation of the four stimuli per individual (Table 4).

Table 4.Long description

1. For Samuel, a male student from university A, the listening order of audio stimuli was 1, 2, 3, 4.2. For Mason, a male student from university A, the listening order of audio stimuli was 2, 3, 4, 1.3. For Theodora, a female student from university A, the listening order of audio stimuli was 3, 4, 1, 2.4. For Tamara, a female student from university A, the listening order of audio stimuli was 4, 1, 2, 3.5. For Yasmin, a female student from university A, the listening order of audio stimuli was 1, 4, 3, 2.6. For Maya, a female student from university A, the listening order of audio stimuli was 2, 1, 4, 3.7. For Levi, a male student from university A, the listening order of audio stimuli was 3, 2, 1, 4.8. For Johnson, a male student from university A, the listening order of audio stimuli was 4, 3, 2, 1.9. For Cecilia, a female student from university B, the listening order of audio stimuli was 1, 2, 3, 4.10. For Gia, a female student from university B, the listening order of audio stimuli was 2, 3, 4, 1.11. For George, a male student from university B, the listening order of audio stimuli was 3, 4, 1, 2.12. For Tyson, a male student from university B, the listening order of audio stimuli was 4, 1, 2, 3. He did not come.13. For Emery, a male student from university B, the listening order of audio stimuli was 1, 4, 3, 2.14. For Tyler, a male student from university B, the listening order of audio stimuli was 2, 1, 4, 3.15. For Hayley, a female student from university B, the listening order of audio stimuli was 3, 2, 1, 4.16. For Gabriella, a female student from university B, the listening order of audio stimuli was 4, 3, 2, 1.

It is worth noting that one participant, Tyson, was unable to attend the evaluation experiment and postexperiment interview due to personal reasons. Nevertheless, we retained his production data as the study’s dyadic design made its removal problematic; excluding his data would require eliminating all dyad interactions involving him, potentially affecting the overall interpretation. In contrast, the evaluation and postexperiment interview did not rely on dyadic interactions and were primarily concerned with identifying broader patterns. Therefore, while Tyson’s evaluation and postexperiment interview data were excluded, his production data remained integral to our analysis.

4.1.5 Postexperiment Interview

While the evaluation experiment explored implicit social evaluations toward uptalk, the postexperiment interview focuses on the deliberate or explicit associations English users in Hong Kong make with it (research question 3). Following a bottom-up approach, it identifies explicit evaluations interviewees made that may or may not be gendered. By analyzing the data from the bottom up, the interview addresses the question of whether participants link gendered meanings such as masculinity or femininity with uptalk without steering them towards confirming preestablished gendered notions. This approach facilitates a less biased exploration of participants’ personal interpretations of uptalk by minimizing external influence on their responses. It provides a more authentic and nuanced understanding into their social evaluations of uptalk. These insights can reveal the social meanings tied to the variable, potentially including those related to gender.

The focus of the Element is on examining how gender conditions social evaluations or meanings of uptalk. Therefore, instead of just focusing on general evaluations of uptalk or the (gendered) meanings of uptalk in general, the interview protocol was designed to explore whether the meanings of uptalk made when people are explicitly aware of uptalk vary according to the listeners’ self-identified gender. In short, the interviews aimed to provide us insight into how the gender of the listener potentially impacts their evaluations of uptalk when they are explicitly aware of the variable, building on sociolinguistic research suggesting that the social meanings associated with linguistic features depend on the context and the listener’s background (Eckert Reference Eckert and Coupland2016).

Before examining the extent to which explicit awareness influences the social meanings attributed to uptalk, the interview first investigates whether listeners can explicitly identify and comment on the feature itself. This approach aligns with Labov’s (Reference Labov1972a) distinction between linguistic indicators, markers, and stereotypes, helping determine whether uptalk operates below the level of explicit awareness (as an “indicator”), is subject to stylistic variation and social evaluation (as a “marker”), or has become a socially recognized and widely commented-upon “stereotype.”

The protocol of the interview was as follows: Following each participant’s completion of the evaluation experiment, they immediately proceeded to a one-on-one interview. At the outset of the interview, participants were explicitly informed that half of the recordings they had heard during the evaluation experiment contained instances of uptalk. They were then given a concise explanation of uptalk, supplemented with illustrative examples to ensure comprehension. This step was implemented to confirm that all participant-listeners had a clear awareness of uptalk as a prosodic feature. After this explanatory phase, participants responded to a structured set of four questions. The first question was designed to assess explicit awareness of uptalk usage. The remaining three questions examined broader sociolinguistic awareness, focusing on participants’ recognition of sociolinguistic patterning and the social meanings explicitly attributed to uptalk:

1. To what extent do you use uptalk in your everyday speech? When do you use it most often?

2. Why do you think other people might use uptalk? And when would they use it?

3. Which people would use uptalk more often? Why do you think so?

4. If a person uses uptalk often in their speech, how would you evaluate them?

When participants provided responses that were too general, ambiguous, or incomplete – for instance, characterizing uptalk as “feminine” – additional probing questions were posed, such as “Why do you believe women utilize more uptalk?” The interviews maintained a semistructured format, permitting deviations from the predetermined four questions as long as discussions still revolved around uptalk or gender-related topics.

Since one participant opted out of the postexperiment interview, data from only fifteen participants out of the original sixteen were collected.

4.2 Data Analysis

4.2.1 Qualitative Data

Data Related to Explicit Awareness of Uptalk

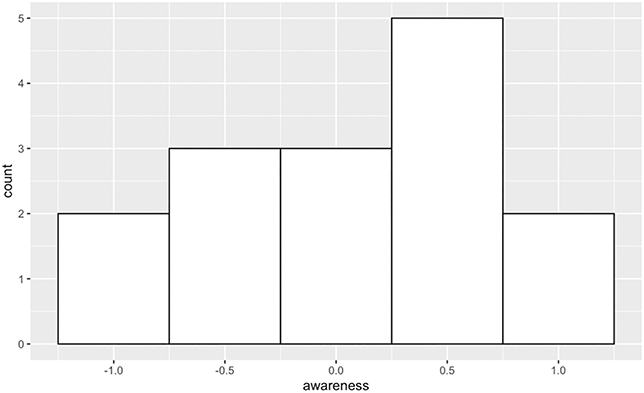

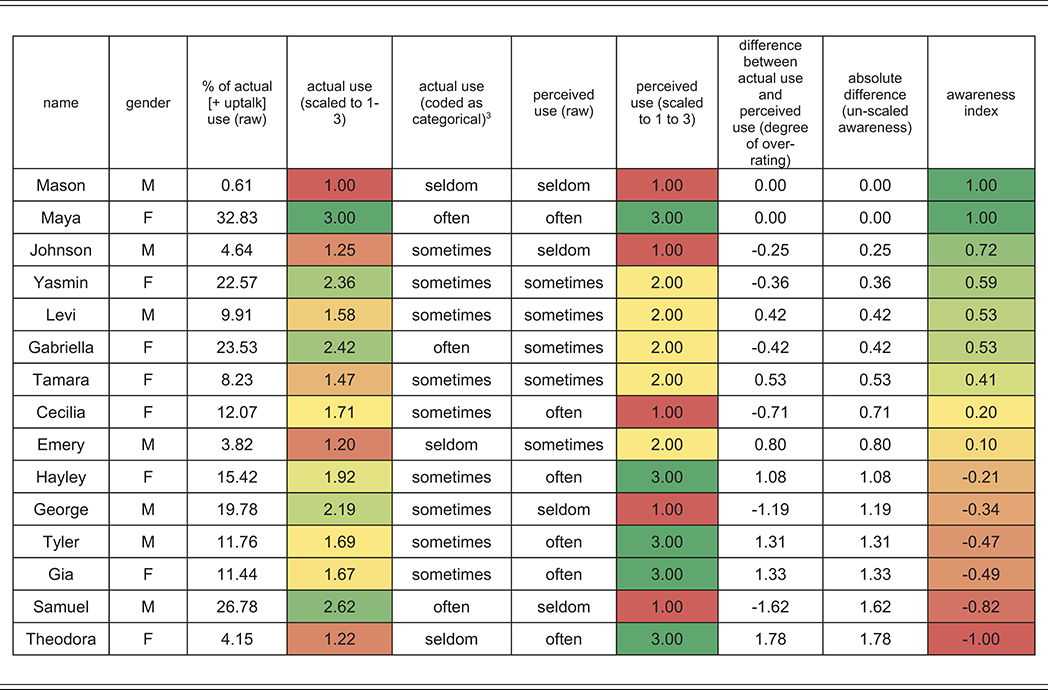

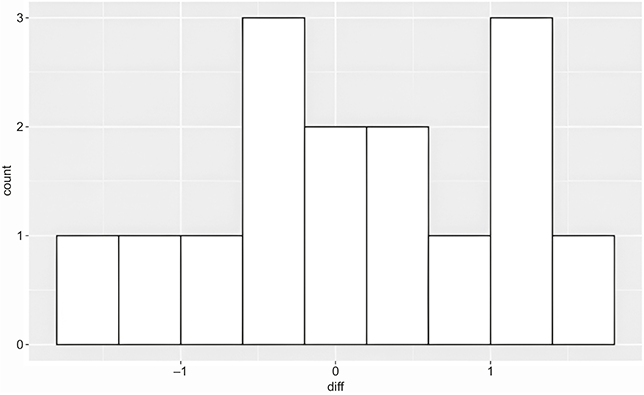

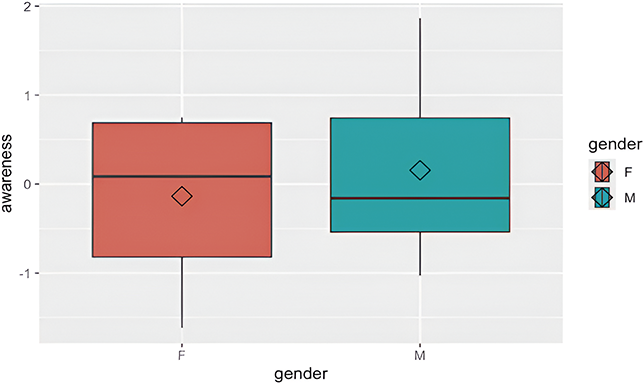

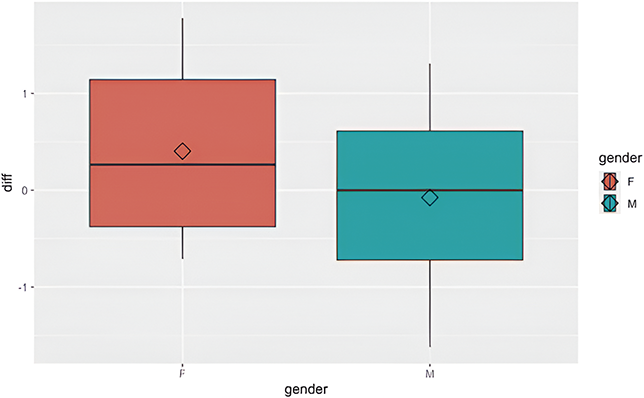

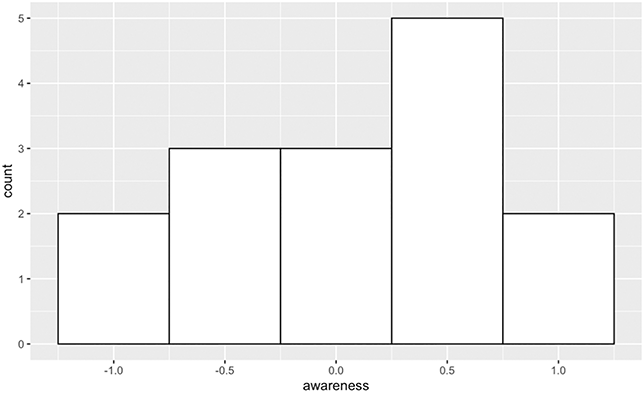

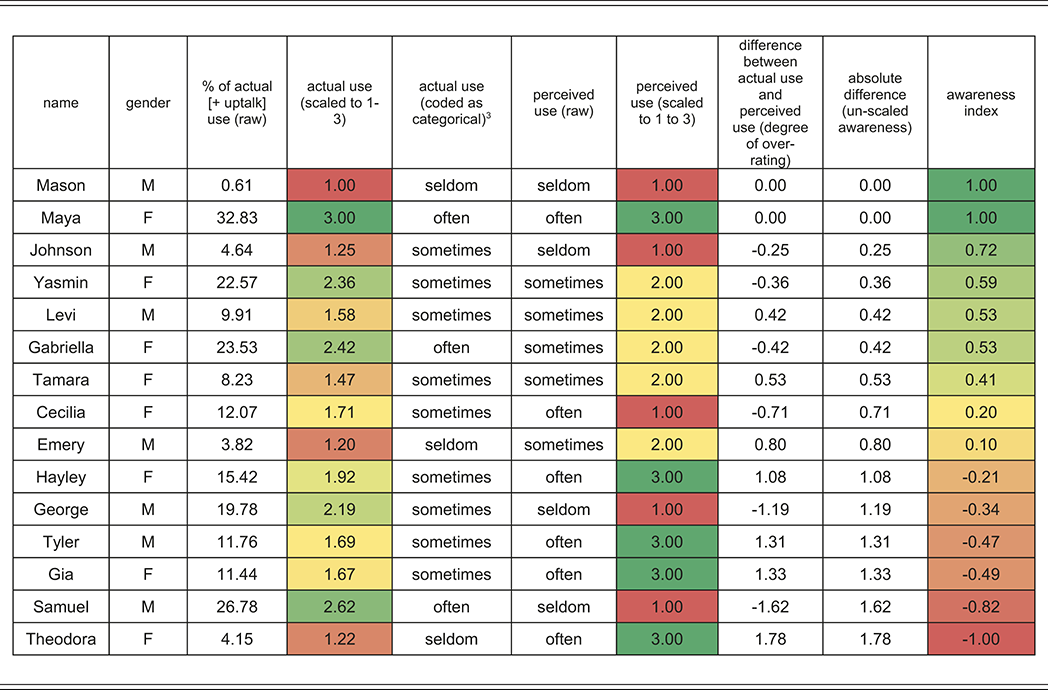

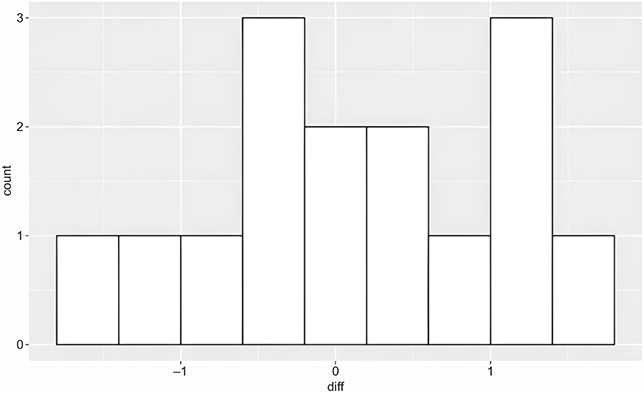

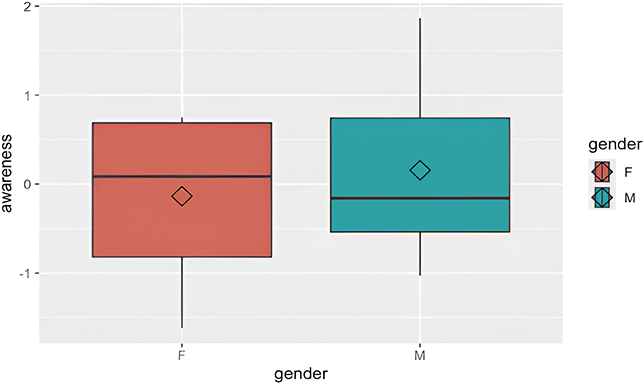

The responses from the first question of the postexperiment interview (Section 4.1.5) were coded categorically and analyzed quantitatively to probe “awareness” of a linguistic feature, which is not usually a straightforward task (D’Onofrio Reference D’Onofrio2018). In this Element, we adopt an indirect method to measure awareness. We first evaluate uptalk production for each listener based on a production experiment (Section 4.1.3), establishing an index that reflects the relative frequency of uptalk usage (Section 5.3). After explicitly defining and clarifying the concept of uptalk to participants, we asked listeners to characterize and explain to what extent they use uptalk in everyday English conversations (question 1, Section 4.1.5), which we coded into a five-category variable: never, seldom, sometimes, often, always. This is the actual frequency index. Then we calculated an index representing the relative perceived frequency of uptalk usage. From these two indices, we derived a measure of awareness by comparing actual and perceived uptalk usage: Larger discrepancies were interpreted as lower awareness. For instance, a listener with a low awareness index may report minimal uptalk use (perceived use) but actually uses it extensively, or vice versa. Conversely, a listener with a high awareness index would have a perceived use of uptalk that closely aligns with their actual use. The “match” between perceived and actual uptalk usage is quantified by the difference between the two indices related to awareness.

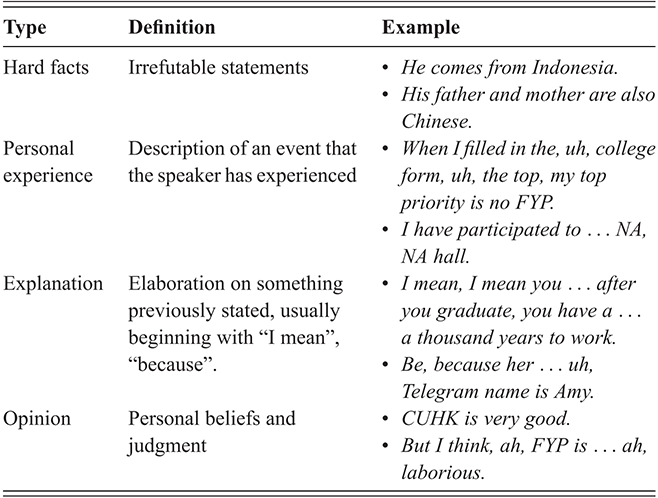

Data Related to Social Meanings of uptalk

Qualitative data related to social meanings of uptalk – that is, the evaluation experiment data (implicit evaluation – evaluations below awareness) and responses to questions 2 to 4 in the postexperiment interview (explicit evaluation – evaluations above awareness) – were analyzed qualitatively. The audio evaluations from the implicit evaluation of uptalk experiment were transcribed and then coded for uptalk (i.e., presence or absence of uptalk), “speaker gender,” and “listener gender.” Responses to the interview that are related to explicitly evaluated social meaning (questions 2 to 4), on the other hand, were transcribed and categorized based on listener gender, as, unlike the evaluation experiment, we opted for a more general approach and did not ask participants to specifically comment on the use of uptalk by male and female speakers, only asking them to comment on general uptalk use that they were exposed to during the evaluation experiment.

The transcribed and organized or categorized responses for the evaluation experiment and the social meanings part of the postexperiment interview were summarized and preprocessed for qualitative analysis. Descriptors and keywords (e.g., adjectives, social types) related to the speaker(s) who use uptalk in the evaluation task and descriptors or terms related to uptalk in general were extracted. There were instances when listeners would comment on or evaluate a non-uptalk variable such as code-switching. Descriptors that involved these were excluded from the analysis. Descriptors that occurred in both “uptalk” and “nonuptalk” conditions were also excluded from the analysis to highlight potential sociolinguistic patterns, for example, the salient differences in social meanings indexed by “uptalk” and “nonuptalk” variants. To enable a consistent comparison, we normalized the terminology by grouping related terms or synonyms under a unified descriptor (e.g., “reluctant,” “hesitant” > “hesitant”). We acknowledge that certain descriptors may carry subtle differences in meaning that are significant and should be preserved. Therefore, when any of the authors identified two similar descriptors as distinct, we opted not to combine them into a single concept. However, when all authors agreed on the merger, the terms were consolidated.

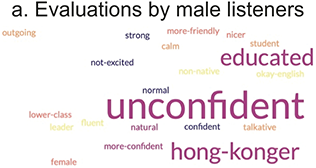

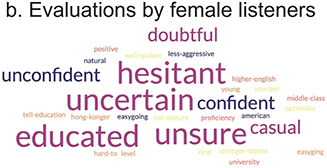

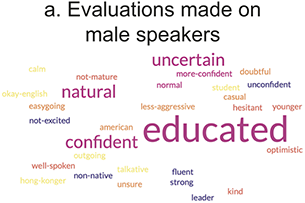

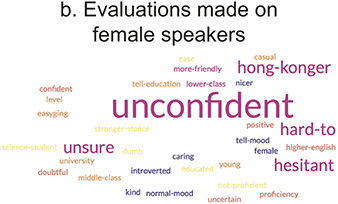

Once the evaluations were preprocessed, summarized, and standardized, we conducted a qualitative comparison of keyword evaluations. For the responses related to the evaluation experiment, we analyzed the responses by uptalk condition. Apart from analyzing the meanings of uptalk generally, we also analyzed the meanings by listener-participant gender as well as speaker gender. For the summarized responses related to the postexperiment interview, we analyzed the meanings by speaker gender in addition to analyzing the meanings of uptalk in general.

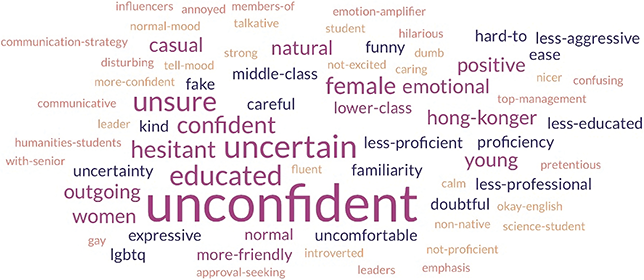

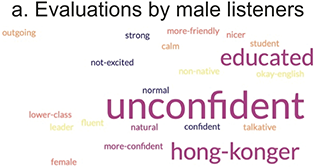

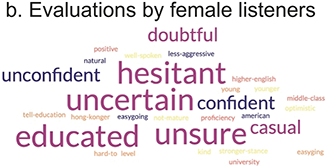

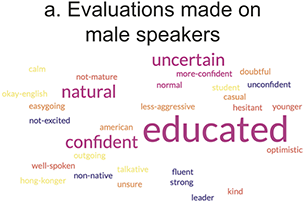

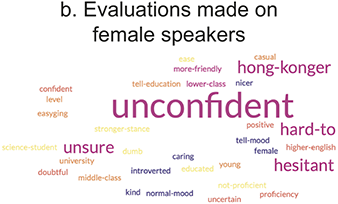

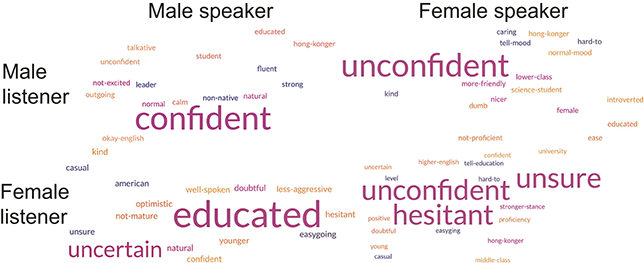

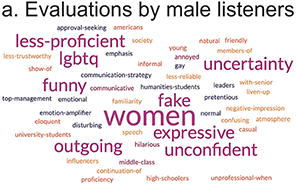

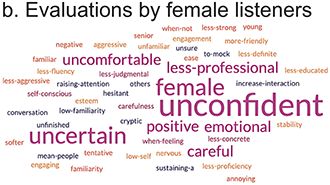

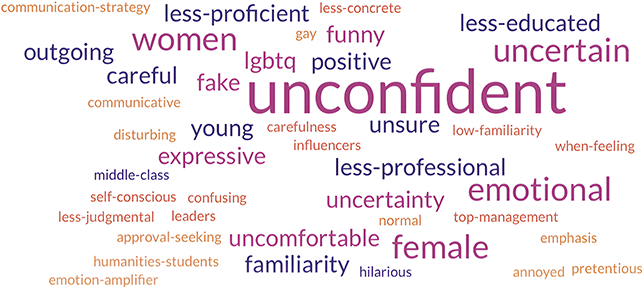

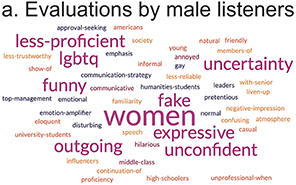

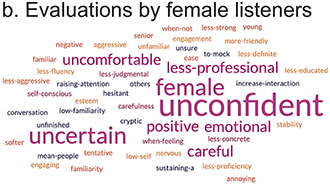

To visually represent distinctions between gender variables, we opted to generate word clouds for both our evaluation experiment and postexperiment interview data, with larger words indicating higher relative frequency compared to smaller words. We decided to use word clouds for both types of data as it can facilitate an easier qualitative comparison between un-/sub-implicit evaluations of uptalk versus explicit ones.

We anticipated that the findings of the word-cloud analysis may erase some of the nuances in social evaluations of uptalk. As such, for the postexperiment interview data, we also conducted a modified form of thematic analysis (McKinley & Rose Reference McKinley and Rose2020) on the raw transcribed data. We initially categorized the interview data by the gender of the participant. Then each comment within these categories was assigned specific codes based on the prevailing themes expressed, such as the level of awareness or the educated meanings associated with uptalk. Following this coding phase, we attempted to connect and interrelate related codes to construct overarching themes that shed light on the nature of uptalk and its explicit connotations.

4.2.2 Quantitative Data: Production Experiment

Preprocessing, Coding, and Subsetting

The audio recordings from the interviews were subjected to a preprocessing and coding process prior to quantitative analysis. First, the recordings were imported into ELAN, where they were segmented into IPs and transcribed into text. These audio-linked transcriptions were subsequently transferred to Praat for further analytical procedures. In Praat, we auditorily identified and coded declarative clauses and instances of rising intonation by leveraging acoustic cues – that is, each IP that we segmented was first coded for type (e.g., declarative, interrogative). Then, we did further uptalk coding only for declarative phrases since uptalk is predominantly salient in these phrases, and such phrases are often the focal point of research into uptalk, presumably due to the relative ease of identifying instances of uptalk in these sentences compared to interrogatives or exclamatory sentences.

For the coding process involving declarative sentences, we annotated each IP for the presence or absence of a final rising intonation. This process involved both instrumental and auditory assessment. First, we examined the fundamental frequency (F0) contours using Praat, visually inspecting pitch tracks for evidence of rising intonation at clause boundaries. This step served as an initial indicator of potential uptalk, though we remained mindful of pitch-tracking errors that can occur in F0 extraction.

Following this acoustic analysis, we conducted an auditory evaluation of the utterances to determine whether the perceptual impression aligned with the visualized F0 contour. In cases where discrepancies arose between the two analyses, the research team engaged in collective discussion to resolve inconsistencies. Our methodological approach was informed by prior research on uptalk (Levon Reference Levon2020) but was adapted to fit the specific research questions and sociolinguistic context of our study. Each utterance was then coded based on a consensus approach. If all four researchers agreed that an utterance exhibited uptalk, it was assigned a coding value of 1; if none perceived uptalk, it was assigned a value of 0. In instances of disagreement (e.g., a two–two split), we consulted a trained linguist based in Hong Kong, who provided an expert judgment to resolve the tie. This multitiered approach ensured methodological rigor and reliability in our uptalk annotations.

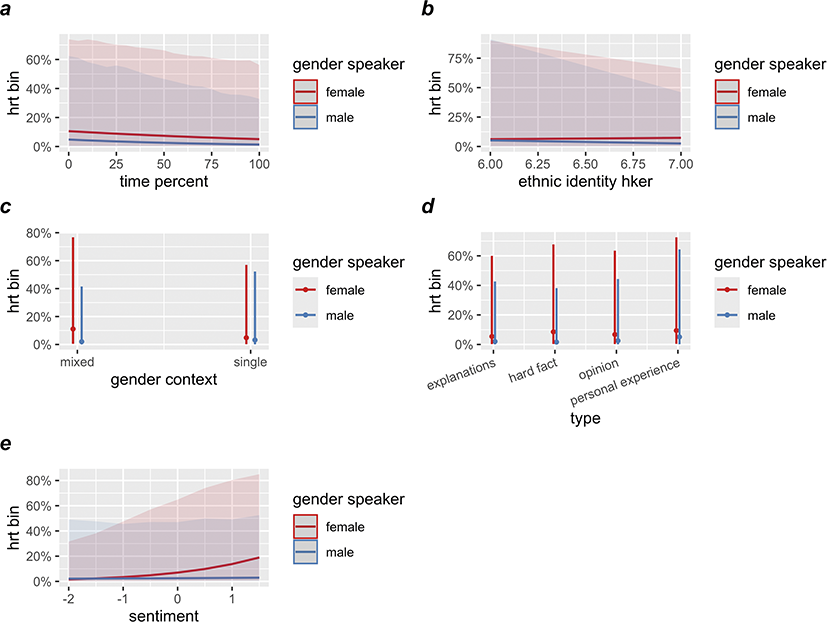

Since we were interested in understanding the potential impact of social and demographic factors on uptalk, we coded each phrase for the factors identified in what follows. The selection of variables in this study was informed by themes emerging from the qualitative analyses as well as insights drawn from the extant literature. Specifically, factors such as socioeconomic status, gender identity, English proficiency, familiarity, and sentiment of utterance were incorporated based on their salience in both empirical data and prior research. Notably, the inclusion of “tertiary institution” as a variable was motivated by research on vowel variation, which has demonstrated that university affiliation can serve as a predictor of localized phonetic patterns (Prichard & Tamminga Reference Prichard and Tamminga2012). In the Hong Kong context, the University of Hong Kong (HKU) is widely perceived as more internationally and Western-oriented compared to other institutions. This sociolinguistic perception suggests the potential for systematic differences in uptalk production among HKU students, thereby justifying the inclusion of “tertiary institution” as a relevant factor in our analysis.

As for the choice to include ethnic identity as a continuous variable and not a categorical one, we used a continuous measure of ethnic identity to capture its fluidity and complexity, rather than rigid categories. This approach is particularly appropriate in a context like Hong Kong, where ethnic identity is often perceived as dynamic rather than fixed (Hansen Edwards Reference Edwards and Jette2016) – that is, many individuals do not see themselves as entirely Chinese or entirely Hong Konger, while some might say they are fully both. Prior research conducted in similar multicultural settings also show that higher ethnic orientation (EO) scores correlate rather than cluster with distinct linguistic patterns, supporting a gradient rather than binary distinction (Hoffman & Walker Reference Hoffman and Walker2010).

1. Socioeconomic status (self-reported scale of 1 “low SES” to 7 “high SES”)

2. Gender identity of speaker (male, female)

3. Age

4. Gender context (mixed-sex, single-sex)

5. Proficiency (self-reported English proficiency of 1 “low” to 7 “high”)

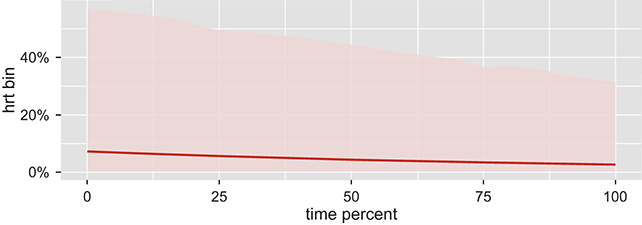

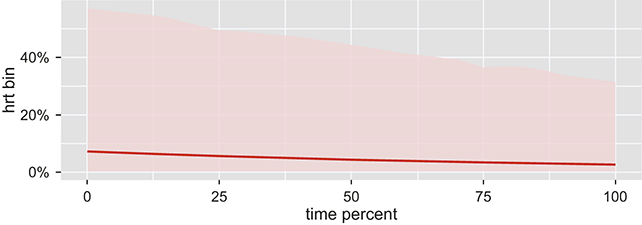

6. Time (normalized to percentage scale)

7. Tertiary institution (Chinese University of Hong Kong vs. University of Hong Kong)

8. Familiarity (strangers vs. acquaintances)

9. Gender of speaker by gender context

10. Individual (random intercept)

11. Conversation pair (random intercept)

12. Awareness

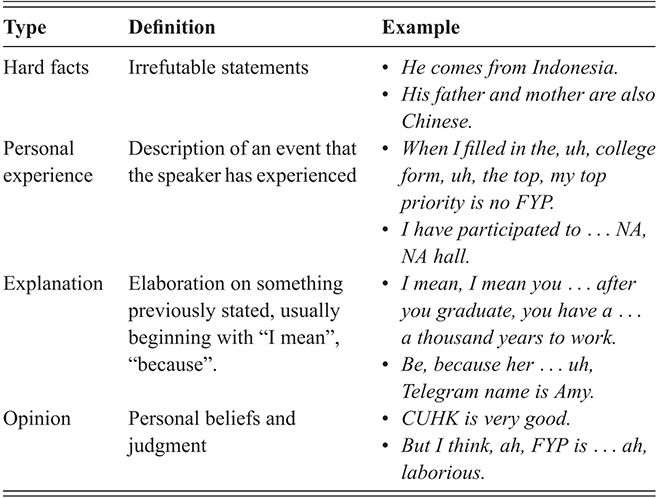

13. Nature of statement (i.e., hard facts, personal experience, explanations, opinions)

The variables were derived or coded from a sociolinguistic survey they completed, which asked them to provide demographic data. The “sentiment” variable was derived using a sentimentR package that takes in a string of texts and outputs a value that corresponds to the level of positivity or negativity detected (Rinker Reference Rinker2022).

Our final dataset contained 4,854 declarative IPs, with a randomly selected 90% (n = 4,368) forming the training set for building a statistical model predicting uptalk likelihood and ranking factors, while the remaining 10% (n = 486) served as the test set, excluded from model fitting and used solely for evaluation. The model (see the following section on the Bayesian regression model) achieved an overall accuracy of 64.4% (95% CI: 59.97–68.66%).

We opted for a 90%–10% split instead of the conventional 80%–20% split to maximize training data, improving robustness and generalizability. This allowed the model to generalize over more data, enhancing its ability to detect uptalk patterns. The model performed well, correctly classifying 272 nonuptalk and 41 uptalk instances, yielding a high positive predictive value (91.58%) – indicating strong reliability when predicting nonuptalk. The balanced accuracy of 63.44% (over baseline 50%) further confirms its effectiveness across both classes despite class prevalence differences. These findings underscore the reliability of the model and the robustness of the statistical patterns it identified, supporting the validity of the results presented later.

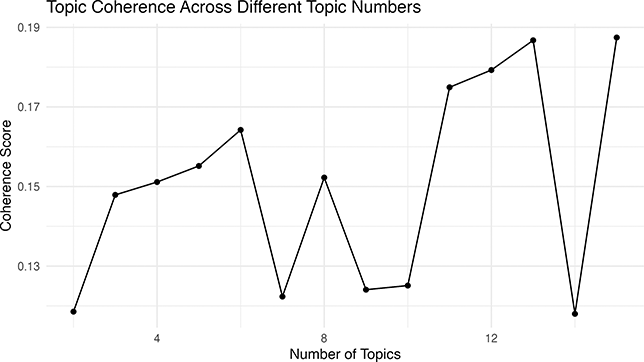

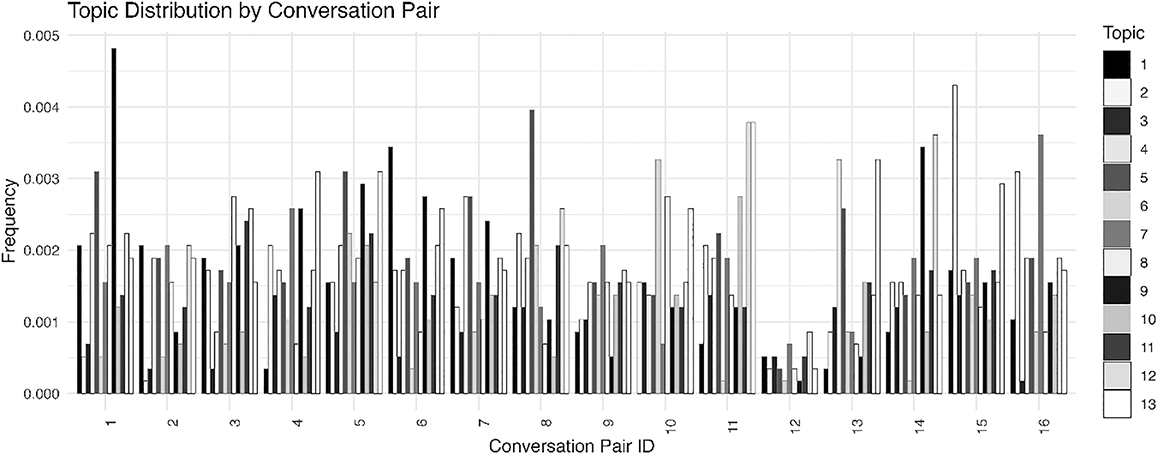

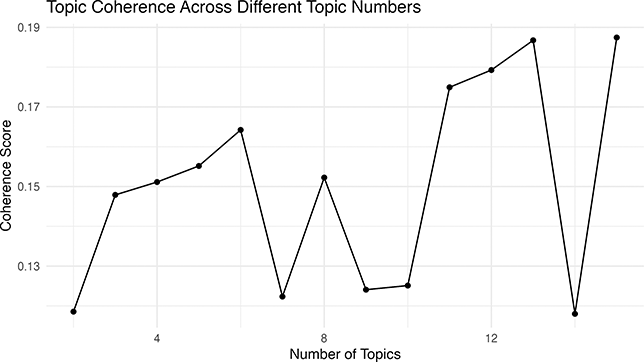

Using the training dataset, we employed two statistical techniques. The first was Bayesian logistic regression, which allowed us to identify factors that condition uptalk, the extent to which these factors condition it (i.e., nonstandardized coefficients), and the likelihood of such conditioning effects. The second technique we used was Boruta algorithm with random forest modeling, which allowed us to identify standardized coefficients or the relative importance of the factors in predicting uptalk.

Bayesian Regression

We employed a Bayesian mixed-effects logistic regression model, incorporating all previously enumerated factors as single, noninteraction predictors. To assess moderation effects of sociolinguistic and extralinguistic factors on the relationship between gender and uptalk, we included interaction terms between “speaker gender” and selected factors: socioeconomic status, age, gender context, ethnic identity, English proficiency, time, tertiary institution, familiarity, and sentiment. Random intercepts for individuals and conversation pairs were added to control for individual and pair-level variability, enhancing our ability to detect extralinguistic effects. Bayesian regression analysis was conducted using the MCMC algorithm in the brms package within R. Each model ran 30,000 iterations per chain across four Markov chains. To ensure convergence, we followed Vehtari et al. (Reference Vehtari, Gelman, Simpson, Carpenter and Bürkner2021: 683), maintaining R̂ values below 1.01 and ESS values above 400.

To evaluate certainty in effect presence, we used the probability of direction (pd) measure, which reflects the proportion of posterior draws aligning with the sign of the median estimate. A pd value close to 1 indicates high certainty in the effect’s direction, whereas values near 0.5 suggest ambiguity (Makowski et al. Reference Dominique, Ben-Shachar, Chen, Annabel and Lüdecke2019). While median values in Bayesian regression models indicate effect size, coefficients are not directly comparable due to differing variable scales. Standard scaling methods, such as centering and z-scoring, are inapplicable to categorical variables and could obscure critical details. Instead, we supplemented our analysis with the Boruta algorithm to rank variable importance in explaining and predicting uptalk usage.

Boruta Algorithm

The Boruta algorithm, a machine-learning method for feature selection (Kursa & Rudnicki Reference Kursa and Rudnicki2010), ranked variables by their importance in predicting uptalk. It generated a shadow dataset – randomly shuffled versions of original variables – to simulate noninformative features. A random forest model then compares real and shadow variables to assess their predictive value.

Feature significance was determined using a z-scored mean decrease accuracy method where a variable was considered important if its z-score surpassed its shadow counterparts. To ensure robustness, the algorithm ran 200 times, minimizing randomness. The output ranked variables based on predictive consistency, using metrics such as median, mean, and maximum z-scores. It also calculated normHits – the frequency with which a variable outperforms its shadow. Features were classified as confirmed (reliable predictors), tentative (potentially predictive), or rejected (insignificant).

This study focuses on the relative ranking of variables, particularly gender-related factors, by examining the mean importance index, normHits, and Boruta’s classifications. These insights, combined with Bayesian regression findings, enhance our understanding of uptalk’s social meanings and extralinguistic influences.

5 Results and Discussion

5.1 Evaluation Experiment

In this section, we report our findings for the evaluation experiment. To reiterate, because we did not explicitly ask participants to rate the utterances with uptalk, the findings of this experiment can inform us about the meanings of uptalk below the level of awareness (i.e., meanings associated with uptalk when the listener is not explicitly aware of the variable).

5.1.1 Evaluations of [+ Uptalk] below the Level of Awareness

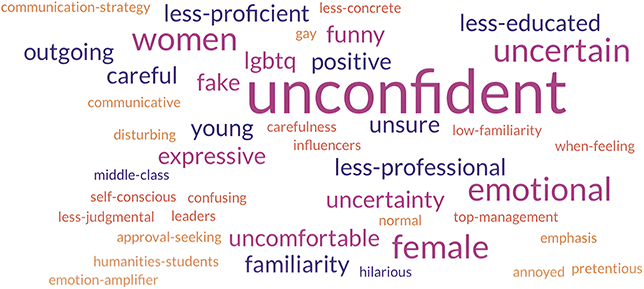

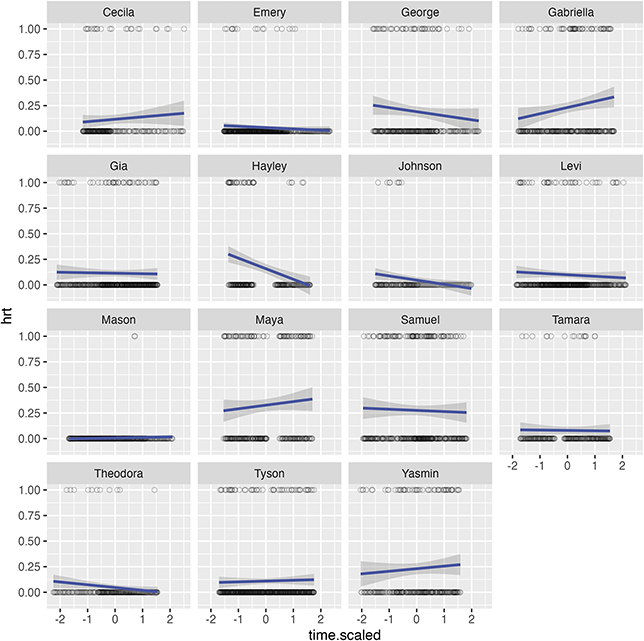

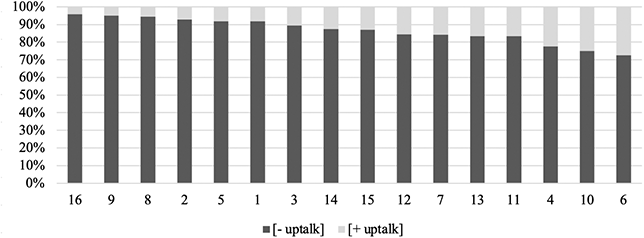

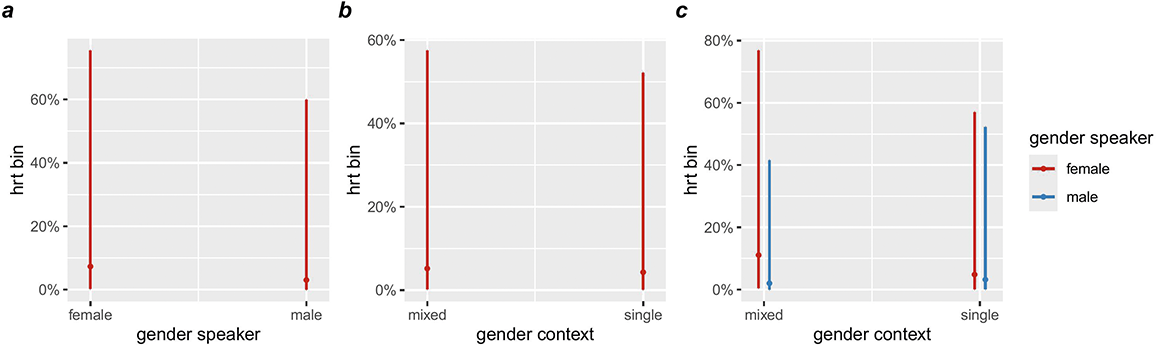

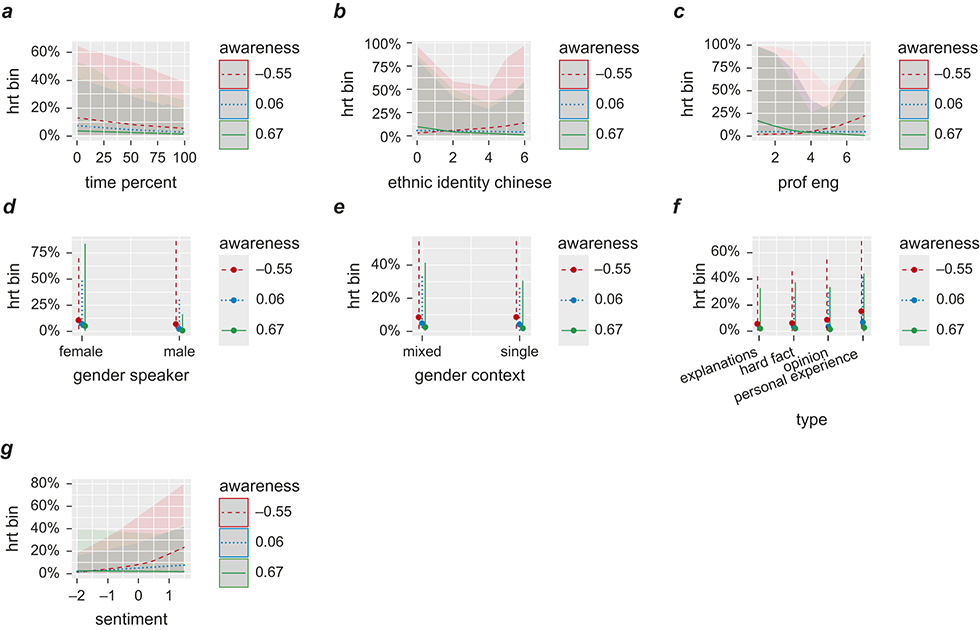

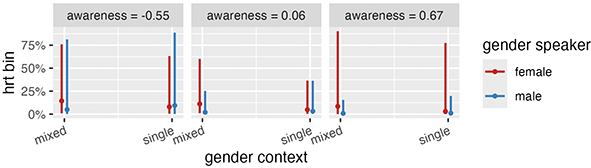

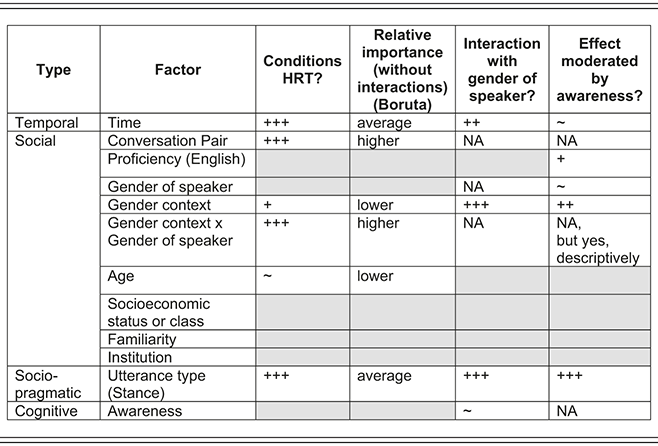

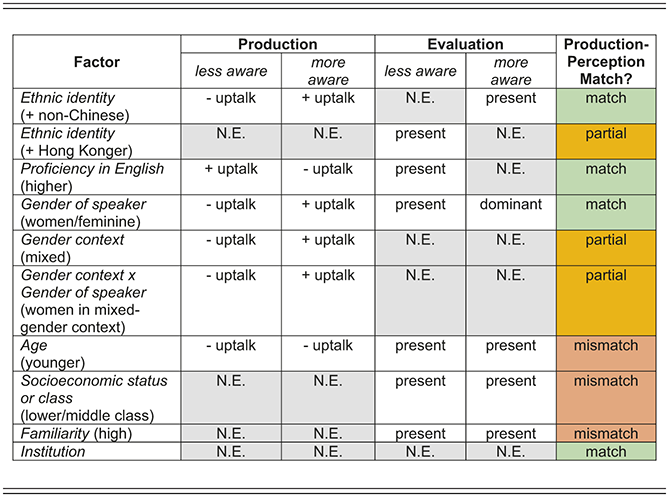

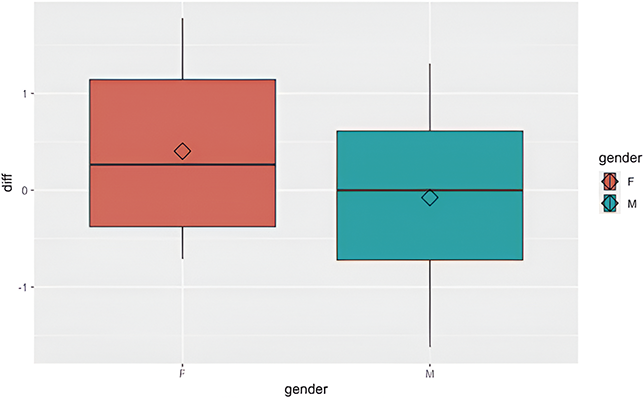

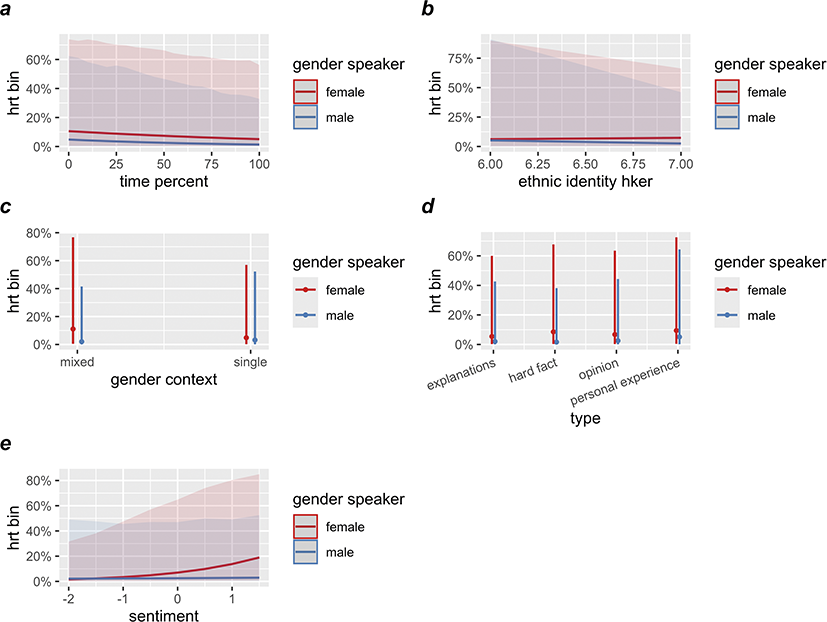

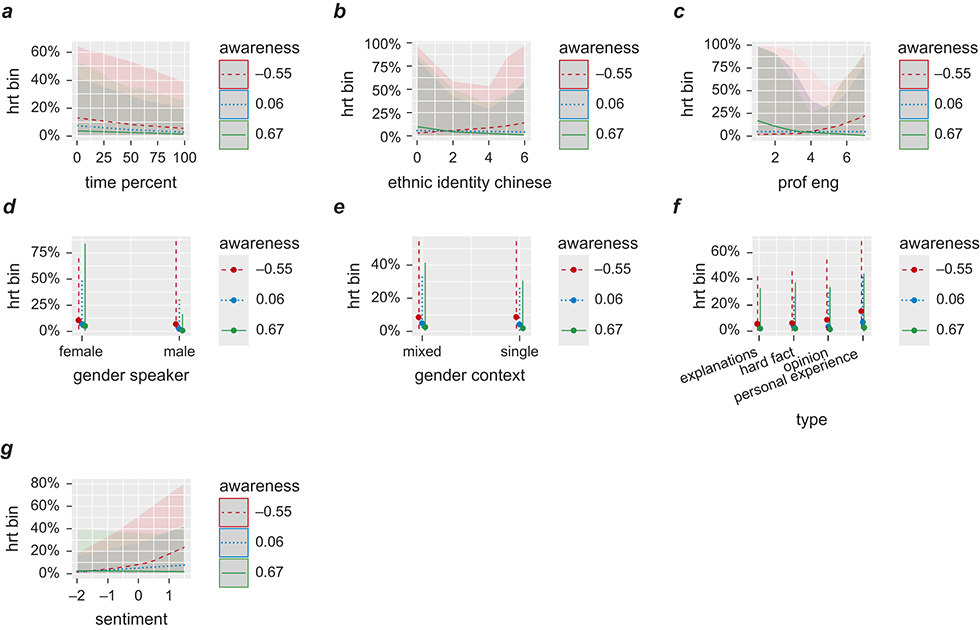

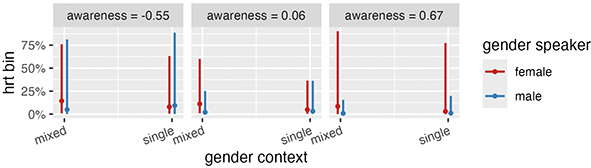

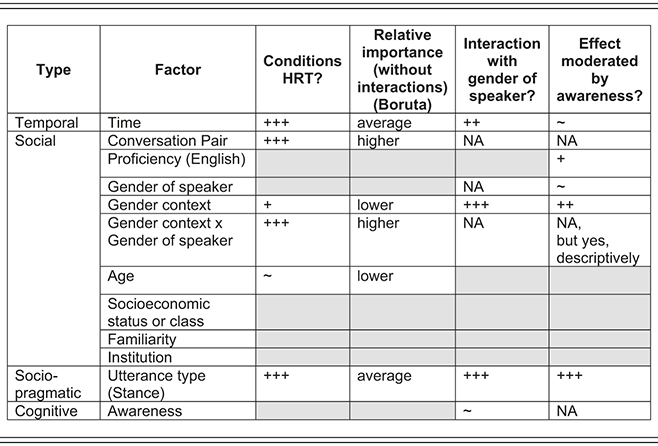

In general evaluations of [+ uptalk], many observers have perceived its use as indicative of a lack of confidence. Other negatively perceived attributes associated with [+ uptalk] include “lower class,” “unsure,” “hesitant,” “less educated,” “fake,” and “uncomfortable.” Conversely, positive perceptions of [+ uptalk] include “natural,” “positive,” “educated,” “more friendly,” and “careful.” Additionally, the use of uptalk is connected to social meanings that are neither strictly positive nor negative, such as femininity (e.g., “female”), queerness (e.g., “LGBTQ”), and local identity (i.e., “Hong Konger”). These observations support our current understanding of variation in modern variationist sociolinguistics, challenging the outdated notion of a direct, unchanging one-to-one relationship between linguistic variables like uptalk and gender. Instead, our findings illustrate a more complex, one-to-many relationship where the gendered meanings of uptalk intersect with meanings of ethnicity, sexuality, and geography. It should be noted that while there is indeed evidence of gendered meanings of uptalk in this evaluation experiment, most participants were not able to identify the gendered meanings of uptalk when they were not explicitly aware of the variable. This is evidenced in Figure 2, where the meanings of “unconfident” and “uncertain” are notably larger than “female” and “women,” meaning that significantly fewer participants identified gendered meanings compared to meanings related to stance.

Furthermore, it is also worth noting that listeners predominantly and implicitly ascribed more positive interpretations to [+ uptalk] than anticipated. Examples of such interpretations include high sociability, evidenced by descriptors such as “friendly,” “kind,” “outgoing,” “easygoing,” and “less aggressive.” Additionally, although [+ uptalk] was associated with the lack of confidence frequently, as indicated in the larger relative size of “unconfident” in Figure 2, it is also associated with “confidence” and an overall positive sentiment. A subset of respondents also suggested that uptalk may signal leadership capabilities (Figure 2).

![The word cloud shows keywords that participants used in their implicit evaluations of [+uptalk]. The biggest (most mentioned) keyword is unconfident, followed by uncertain, unsure and educated. Smaller keywords include hesitant, confident and female.](https://static.cambridge.org/binary/version/id/urn:cambridge.org:id:binary:20260216040009705-0144:9781009634083:63404fig2.png?pub-status=live)

Figure 2 Summary of implicit evaluations of [+ uptalk] overall

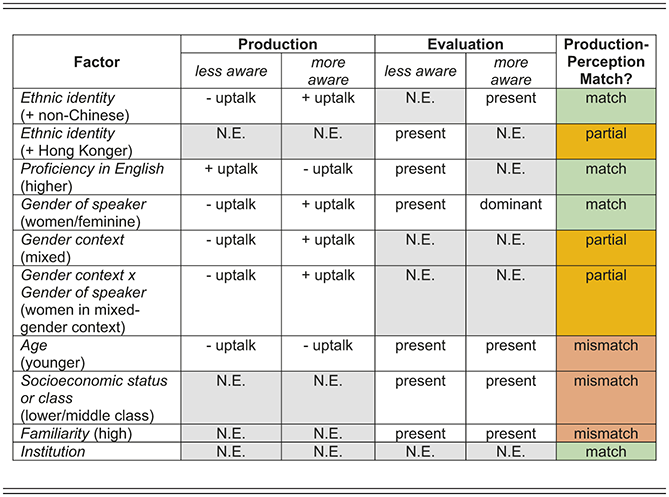

Our study also highlights apparent contradictions, like the simultaneous association of uptalk with both “confident” and “unconfident,” as well as “educated” and “less educated.” Within the framework of sociolinguistic variationism, such contradictions are anticipated, reflecting the inherent under-specification of language and the contextual emergence of meanings (Hall-Lew, Cardoso, & Davies Reference Hall-Lew, Cardoso, Davies, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021). These conflicting interpretations suggest that varying contexts might lead to different understandings of uptalk. Consequently, we delve into an analysis segmented by different gender contexts, starting with the gender of the listener, followed by the speaker’s gender, and finally examining the dynamics between genders of speakers and listeners.