Heroic Balladry

The philological project of editing epics from ancient manuscripts was flanked by a concurrent vogue for materials taken down from oral performance. The prototype appeared in Vienna in 1814. It was a Serbian anthology, sponsored by the Vienna court librarian and Slavic philologist Jernej Kopitar (whom we encountered in Chapter 4 as a contact of Hoffmann von Fallersleben). Kopitar had taken a young man under his wing who had taken refuge in Vienna from the anti-Ottoman warfare in the Pashalik of Belgrade. This man, Vuk Karadžić, had the unique advantage of being both highly literate and intimately acquainted with the oral literature traditions of his home region. At Kopitar’s behest, he published a collection of Serbian folksongs, Srpske narodne pjesme, in 1814.1

In this initiative Kopitar took his cue from Jacob Grimm, who was beginning to make a name for himself as a philologist and as a collector of oral literature. Jacob and Wilhelm had tangentially collaborated on the seminal collection of German balladry Des Knaben Wunderhorn, edited by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano. The Grimms’ collaboration with Arnim/Brentano’s family–friends network (the so-called Bökendorf Circle) had continued when the brothers followed through with that benchmark of benchmarks: their collection of folktales and fairy tales (in the original: Kinder- und Hausmärchen, ‘Wonder Tales for Children and the Household’, 1812–1815). The Grimms were shifting the frame in which oral literature was collected and read. Formerly, folk literature had been read sentimentally, as representing the artless, homely pastimes of naive but virtuous rustics; but starting with the Grimms, such texts were also read ethnographically, as the unmediated cultural expression of the unlettered masses, who, thanks to their lack of exposure to polite learning, had kept their native cultural heritage intact in unadulterated, authentic, albeit rough-hewn form.

Grimm had met Kopitar after joining the Hessian delegation to the Congress of Vienna in a secretarial capacity. In Vienna, Grimm had elaborated his new, more ethnographical approach to folk literature in a convivial circle that met during the Congress in 1814: the ‘Wollzeiler Circle’. Its members had drawn up a questionnaire to be distributed to wide circles of possible respondents, developing a similar one that had already been drawn up by Brentano for the Wunderhorn project in 1806.Footnote * Karadžić’s anthologizing work was sparked off when Kopitar presented that questionnaire to him.2

In turn, Grimm was fascinated by this voice from what was still the Ottoman-dominated part of Europe. He went to the trouble of learning Serbian, entered into direct correspondence with Karadžić, reviewed his work and published a translation of his Serbian grammar in 1824.

Authentic and rough-hewn: that is what Karadžić’s collection certainly was. It came from a part of Europe where late-Enlightenment, genteel sentimentalism was thin on the ground. Instead, there were violent altercations between local warlords and outlaws and their capricious and harsh Ottoman rulers. A follow-up volume appeared in 1815, when the second Serbian insurrection against the Ottomans broke out, and in it were hard-bitten martial ballads based on recent events. Grimm was delighted with this unexpected contribution to his folkloric–philological agenda from an unexpected corner of Europe. He would support a new expanded edition that appeared in Leipzig in three volumes in 1823–1824.

The combination of linguistic and folkloric interests characterizes both Grimm and Karadžić. The latter would become the ‘Serbian Grimm’ and would go on to collect further oral material. He would also reform the Serbian language and alphabet, lessening its dependence on the old liturgical language and adapting it to modern circumstances and usage.

The Serbian heroic balladry collected by Karadžić reached a European readership on the wings of the Serbian insurrection; meanwhile, Byron had published his stirring poems of passionate violence in Europe’s wild, Turkish-dominated outlands. The Srpske narodne pjesme were just that: songs of the nation (narod), nothing like the juvenile and domestic (Kinder- und Haus-) context where the Grimms’ fairy tales came from.

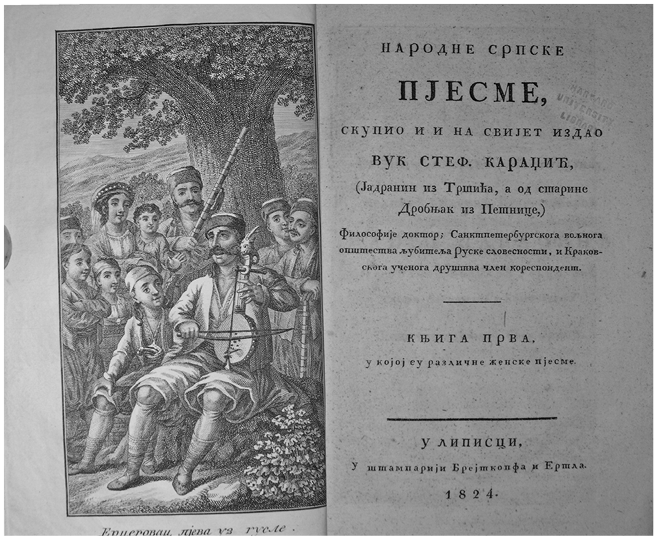

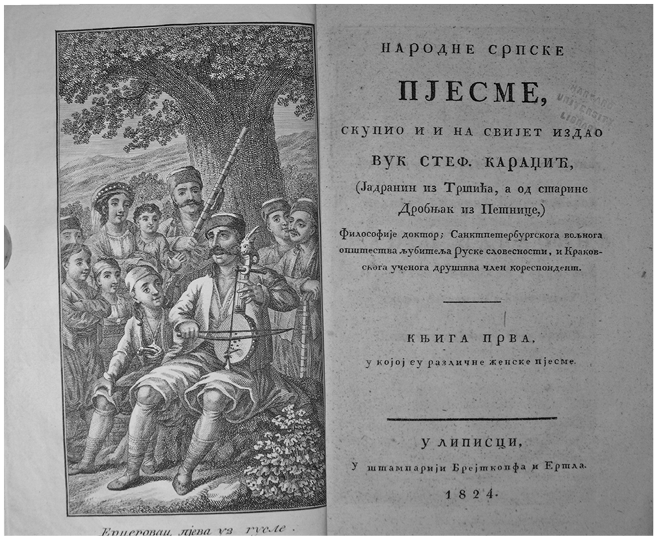

The frontispiece to the 1824 Leipzig edition of Karadžić’s collection (Figure 5.1) shows the setting for this type of oral-performative literature: a seated singer with his one-string fiddle (gusle) to accompany his rhythmically chanted ballad. He stares into the middle distance in something that is either concentration, a poetic ‘flow’ or a Romantic rapture that, Ossian-style, captures the collective imagination; we are reminded, incongruously, of the painting in which an impassioned Rouget de Lisle sings ‘La Marseillaise’ before enraptured listeners (Figure 1.3). The ‘abstracted staring gaze’ can be encountered repeatedly in many illustrations in this book, from Ossian to Liszt. In most cases it signifies inspired rapture. In this specific instance it may also connote blindness. Vuk Karadžić’s main informant, the guslar Filip Višnjić, had gone blind at an early age as a result of smallpox. In many societies, the visually impaired made a living as performing poets/musicians. Their physical blindness was, in the popular imagination, often linked to their literary gifts, for example in Irish folklore (Ó hÓgáin Reference Ó hÓgáin1982). The blindness of Homer and Tiresias added classical prototypes; Višnjić became known as the ‘Serbian Homer’. Around the guslar (to return to the frontispiece of Karadžić’s anthology), and under the tree of what is apparently a village setting, various representative members of the community (different genders and ages) are listening to his song, united in their rapt attention as an ‘affective community’; one of them is a martial young man with a rifle.

Figure 5.1 Frontispiece and title page of the 1824 edition of Vuk Karadžić’s anthology.

This picture of the performer as, literally, the voice of his narod, reciting the traditional literary heritage for a contemporary audience, quickly became iconic. In part it suited the post-Ossianic idea of the inspired poet as the voice of his nation – the guslar shown here is the modern equivalent of Ossian, and both are ‘bards’. There was also a contemporary context for this appeal: in these years there was a widespread philhellenic interest in the klephtic songs of insurrectionary Greece, and it had repercussions far afield. Claude Fauriel’s philhellenic Chants populaires de la Grèce moderne appeared in 1825; and that book in turn inspired the Irish collection of James Hardiman, Irish Minstrelsy (1834), which retrieved anti-English balladry from the preceding century. Hardiman prefaced it with a firebrand introduction, citing Fauriel’s example and arguing that the position of Ireland under British rule was similar to that of Greece under Turkish rule – explosive stuff, in a year that saw Athens established as the capital of an independent Greece.3

Popular songs, including those that were folkloristically retrieved, became the public carriers and platforms of popular discontent and national aspirations. The outlaws and rebels (hajduks) celebrated in these songs became Byronic hero-figures with a nationally inspiring value. One century later, the guslar was cited as the most important cultural claim to independence for the southern Slavic nations. In 1917, when American geographers were preparing the Paris Peace Conference and deliberating how to apply the principle of the ‘self-determination of peoples’, the echoes of Karadžić’s frontispiece of 1822 were still reverberating in a book with the indicative title The Frontiers of Language and Nationality in Europe:

The pjesme voices Serbia’s national aspirations once more in the storm and stress of new afflictions. Its accents ring so true, that the geographer, in search of Serbian boundaries, tries in vain to discover a surer guide to delimitation. From the Adriatic to the Western walls of the Balkan ranges, from Croatia to Macedonia, the guzlar’s ballad is the symbol of national solidarity. His tune lives within the heart and upon the lips of every Serbian. The pjesme may therefore be fittingly considered the measure and index of a nationality whose fibre it has stirred. To make Serbian territory coincide with the regional extension of the pjesme implies the defining of the Serbian national area.4

The European spread of this heroic balladry ran through the conduit of the works of a young woman of letters, Therese von Jacob (her pen name, based on her initials, was ‘Talvj’), whose translation of Volkslieder der Serben appeared in 1825. Talvj had been recommended to Kopitar and Grimm by none other than Goethe himself, who used the occasion to recall that he himself had, in fact, already translated one of these ballads forty years previously.

That was part of what made Goethe so awe-inspiring and so irritating to his younger literary contemporaries: the fact that he had always already been there and done all that – all those things that were subsequently being discovered as new and exciting. Since his debut in 1770s he had consistently been ahead of the literary curve; and in 1775 he had, in fact, translated a southern Slavic ballad, Hasanaginica.

Flashback: Ossian in the Balkans

The ballad in question, on the tragic fate of the wife of the warlord Hasan-Aga, had been noted down in 1770 by a Venetian traveller and geographer, the priest Alberto Fortis. Fortis had undertaken a field trip to Dalmatia, the eastern coastlands of the Adriatic sea, then under Venetian control but adjacent to Ottoman-dominated territory. His Viaggio in Dalmazia (1774) contained, next to the description of cities and regions, the full text of Hasanaginica, in the original Croatian with an Italian translation on the facing pages. It caused a furore. Goethe got hold of a German prose translation and cast it into metrical form, using the ten-syllable metre that was also used in the original Croatian ballad. The text was published in Herder’s classic edition of multinational Volkslieder (1778, later retitled Stimmen der Völker in Liedern, ‘the voices of nations in their songs’). From there, Hasanaginica went viral across Europe, with versions in English, French and Russian being penned by the likes of Walter Scott, Prosper Mérimee and Alexander Pushkin.5

This first wave of European popularity was as yet in the sombre, Ossianic, sentimental mode that dominated the 1770s. Indeed, Ossian’s shadow is all over Hasanaginica’s reputation and spread. Fortis was in fact an associate of Cesarotti, the Vico-inspired translator of Homer and Ossian, and his Dalmatian voyage had been sponsored by the great Scottish champion of Ossian’s authenticity, Lord Bute. (The 1778 English version of Fortis’s book, Travels into Dalmatia, is dedicated to Bute.). It looks as if an Ossianic bug had spread in Venice: here, too, antiquaries were hunting for ancient, lost literary treasures. Like Edinburgh, the Venetian metropolis had wild highlands in its geographical backyard, inhabited by a population that seemed to Venetians alien and primitive. Situationally, the Scottish model that had led to the discovery of Ossian could inspire fieldwork in the Dalmatian uplands. But fieldwork it was indeed: not a search amidst library shelves for lost manuscripts, but (as with Macpherson) a voyage into remote lands to note down orally performed traditions.

The Ossian model could obviously inspire folklore research as well as philology. Indeed, the scandal of Ossian had the effect of breaking down the division between literary epic and oral tradition. Initially, Ossian was exposed as fraudulent because written originals were not forthcoming and people were unwilling to credit ‘savage Highlanders’ with maintaining, orally and over many centuries, an epic tradition. But that crux could be turned on its head. If indeed Ossian was not the ‘northern Homer’ he had been reputed to be, could it not be that Homer himself had been a sort of ‘Mediterranean Macpherson’? Was not Homer’s own method closely akin to what Macpherson had done – cobbling together oral ballad material into an epic whole? Were there not oral-performative (‘rhapsodic’) sources providing Homer with the building blocks of his Iliad and Odyssey? Was Homer not the compiler, rather than the creator, of his epics? This was the notorious ‘Homeric question’ that hit Europe in the 1790s; it had been anticipated by Herder’s reflections on the authenticity of Ossian and by the discovery of Hasanaginica.6

By the early nineteenth century some consensus had been reached that ‘foundational’ epic texts were perhaps not that Big Bang out of nowhere that they had previously been imagined to be: that they were the crystallization of an earlier, orally circulating body of heroic ballads sung by ‘rhapsodes’, not unlike the guslar on the title page of Karadžić’s collection. The Golden Age of ancient literature was preceded, as Thomas Love Peacock put it, by an Iron Age. This hugely raised the status of balladry and oral literature. Philologists began to look for the moment when national literatures (in written, formalized form) emerged from their oral-formulaic, folkloric run-up; contemporary performances such as the Serbian ones were a case in point and were aligned with other, older cases such as the medieval Provençal troubadours. Claude Fauriel, first professor of littératures étrangères at the Sorbonne, studied the origins of both troubadour poetry and oral Greek balladry (spawning his philhellenic Chants populaires de la Grèce moderne of 1824). In both cases, he was trying to chart the transition from oral-performative to written-literate stages of national literatures.7

No wonder the framing of oral literature shifted from sentimental to national-historicist, as the two-stage reception of Hasanaginica shows. Forty years after Goethe, Karadžić’s collection included the Hasanaginica once more.Footnote * By now, however, the frame in which those texts were read was no longer sentimental and Ossianic; it had shifted to a Byronic register, with its harsh evocation of violent passions under Ottoman tyranny. In addition, the status of oral literature had shifted as well. The Grimm brothers by 1812 had begun to consider fairy tales as very serious business indeed: the last vestiges of ancient legends and sagas (much as Macpherson had seen his Highland balladry as the broken remains of an ancient epic). And the collecting of oral-performative, traditional literature became a twin discipline to the textual scholarship of philology. The Grimms and Karadžić were players in both fields. The idea of ‘oral epic’ was born – something that, like ‘national epic’, might have seemed a self-contradictory term a few decades previously.

The Nation as Author

Epic and oral literature had in common anonymity and an unclear provenance. It was this that opened up the suspicion of forgery. (More on that in Chapter 7.) When Prosper Mérimée, in his collection La guzla (1824), cashed in on the vogue for the balladry of Balkan outlaws, he included, among his French translations, some counterfeits of his own as well as a patently fabricated story of how he had ‘noted these down’ from oral recitation; Hoffmann von Fallersleben later on ‘edited’ traditional Flemish ballads that turned out to have been his own confections. Both men later tried to brush these off as mere playful Romantic pranks.8

Another way of dealing with this murky uncertainty was to proclaim the diffuseness of the provenance as a virtue: ancient epics were the product of the nation’s collective imagination at the very moment when it was beginning to find a voice of its own. The ancient bards, rhapsodes and myth-tellers were mere mouthpieces of the nation at large, and their anonymity was therefore fitting. The Grimms went so far as to argue that the medieval chivalric texts with known authors (Wolfram von Eschenbach, Gottfried of Strasbourg etc.) were already beginning to lose the vigour of the truly archaic, authorless texts, were beginning to pander to the courtly taste of the elite and were exposed to the pernicious influence of a French-based, Europe-wide taste for romance rather than rough-hewn, native epic.9

For those cultural communities that had historically been unable to build up a textual documentary archive of their own, or whose literary output had obtained no access to the printing press, it was a good second best to have access to heroic balladry and oral epic. Such literature documented the vigorous character and ancient traditions of the nation, even in the absence of written documentation. The ripple effects of the Grimms’ oral researches spread far and wide. In Russia and its Baltic provinces, byliny (ballads) and skazki (folktales) were a matter of interest (collected by Pavel Rybnikov and by Alexander Afanas’ev in the 1860s). In Ireland, Norway, Finland, the Baltic, the Balkans, the work of the Grimms was picked up. Inspired by the Grimms, Thomas Crofton Croker collected Irish fairy legends, which the Grimms then translated into German as Irische Märchen. In Norway, Asbjørnsen and Moe collected their Norske Folkeæventyr. But nowhere was the impact as powerful as in Finland.10

Long a Swedish province, Finland had been ceded to the Russian Empire in 1811, and Finnish culture was better off as a result of the transfer. Its cultivation was allowed under Russian rule because this weakened the old ties with Sweden. The local elite, traditionally Swedish-speaking, turned to Finnish as a way out of the predicament that, no longer Swedish, they could never become Russian. What is more, there was now an open border with Karelia to the east and with the hinterland around St Petersburg, where similar, related vernacular cultures could be encountered. Fieldwork and ballad-collecting was done among the local populations, largely in the eastern parts of Finland, and a rich harvest of oral-formulaic poetry was noted down. The heroes of these lays and ballads were already known from legends, and one of the foremost collectors, Elias Lönnrot, spliced the ballads together into a coherent legendarium involving the deeds and fates of a focused set of mythical protagonists. Indeed, the tales bordered on myth in that many of the incidents bespoke a magical world-view full of supernatural incidents and a fluid non-demarcation among humans, animals and objects.11

In fact, Lönnrot did exactly what Macpherson had tried to do. But whereas Macpherson was still working in the paradigm of discrete heroic epics created by a single, individually known original genius, Lönnrot (who anyway was more candid about the provenance of his diffuse source material) presented his Kalevala more in the mode of a thematically integrated legendarium of ancient Finnish traditions involving ancestral figures and memories as told in formulaic verse by rustic performers. The result was nonetheless immediately hailed as ‘the Finnish national epic’, once again demonstrating the philological proximity between folklore and high literature. Grimm’s comments on the epic quoted in Chapter 4 (to the effect that it required its readers to mentally project themselves into wholly vanished circumstances) were made, in fact, in a paper ‘Über das finnische Epos’ presenting the Kalevala to the Prussian Academy in 1845; and in it Grimm drew a direct line from Finland to Serbia:

In Serbia the faithful memory of the people, especially old blind men, preserved a body of songs, each of which contains fifty, a hundred or even 500 or 1000 lines in the purest and most easy-flowing language; if one were to integrate those which belong together … one could form entire cycles amounting to minor epics.12

Finnish culture received a huge boost from the Kalevala; its publication day is still a national holiday in contemporary Finland. It put Finland, literally, on the European map, stimulated the fennicization of the Swedish-speaking Finnish elite and stimulated the organization of Finnish-language cultural and academic life. And it had a knock-on effect of its own: the German-speaking bourgeoisie of present-day Estonia was inspired to delve into the country’s own vernacular culture, closely related to Finnish. An Estonian who studied theology in Helsinki notified the local learned society of Tartu of the appearance of the Kalevala; this galvanized an already emerging interest in similar Estonian lays; and before long these were compiled in the Estonian ‘national epic’, the Kalevipoeg.13

The pattern even caught on outside Europe. In North America, Henry Schoolcraft collected Ojibwe material, very much in the Grimm mode. He had privileged access to this cultural tradition because his wife Jane was of Ojibwe descent and informed many of the works published under Henry’s name. Also in North America, loosely circulating heroic legends were forged together into a literary whole in Henry Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha (1855). It was consciously inspired by Lönnrot’s Kalevala and shared its metre (a trochaic tetrameter prevalent in Finnish oral poetry), and for its theme it drew on Schoolcraft’s Algic Researches (1839); its publication triggered in turn Schoolcraft’s The Myth of Hiawatha (1856, dedicated to Longfellow). In the background, there were also (to some extent misidentified) cultural memories of a historical Hiawatha, cofounder of the Iroquois Confederacy.14

What made these epics truly ‘national’ was their inspirational value for contemporary audiences. The texts became classics, and as we saw in Chapter 4, that canonical status was demonstrated most of all by the wealth of remediation that these heroic epics inspired. Hiawatha and his beloved Minnehaha resonated through sentimental American culture in countless paintings and porcelain figurines; and it was to have been the basis for a nationally American opera by Dvořák (who abandoned the project and instead used it as an incidental, tangential inspiration for his symphony From the New World). Parts of the Kalevala were set to music in many compositions by Jean Sibelius, and it inspired illustrations, paintings and murals by the art nouveau artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela. The streetscapes of Helsinki are suffused with references to the characters of the Kalevala, in the names of streets, buildings and businesses. And the cultural backbone of Finland shifted decisively towards a mythical, idealized ‘Karelia’, an undefined rustic region remote from Swedish modernity and uncertainly straddling what is now the Russian-Finnish border. The Kalevala-driven fennicization of Finland as an emergent nation also meant that this Finland claimed descent from a Karelia that would always be, fatally, contested with the neighbouring Russian Empire, leading to repeated frictions and hostilities.15

A Window on Mythology

The retrieval of epic, be it as literary text or as folkloric material, is a way of trying to delve into to the deep primordial antiquity, the primeval roots even, of the nation’s literature. For Grimm, both epic and folklore were expressions of the deepest strata of the nation’s self-articulation and Weltanschauung. Ancient epic and folklore offer us glimpses of how the nation experienced the world at very ancient moments of its emergence into history, and before it experienced the influences of other cultural traditions. Grimm used law in a similar ethnographic manner, studying ancient legal customs about ownership, kinship, trespass and punishment, in order to retrieve, almost anthropologically, the German nation’s primal ethics and self-regulations.16

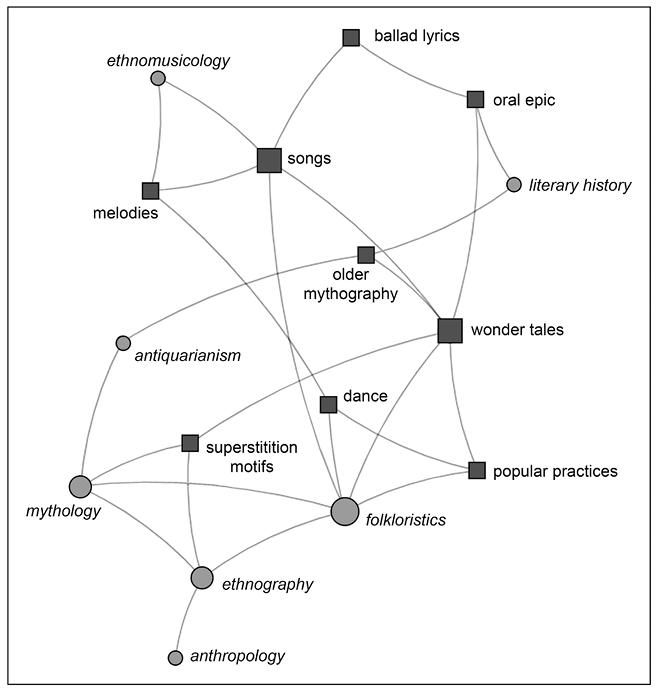

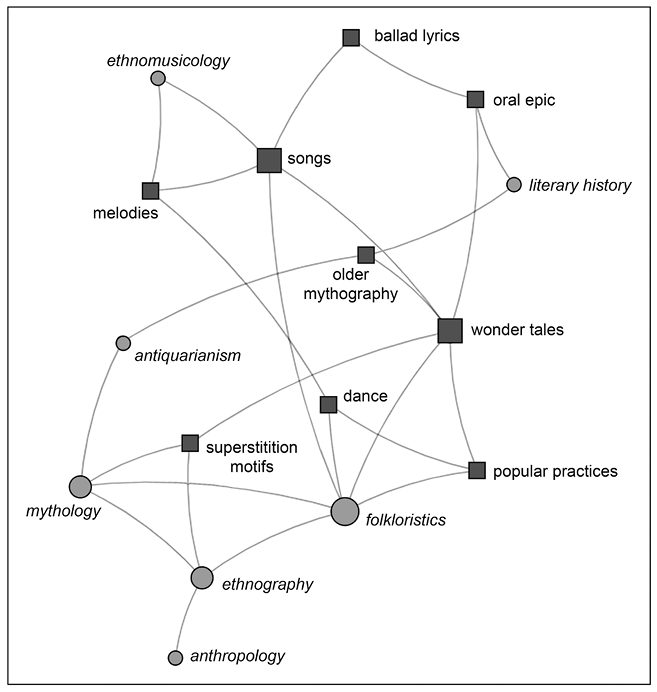

At this point we must briefly ask ourselves what precisely the orality was that philologists were beginning to investigate. The word ‘folklore’ did not yet exist – that word was consciously coined later to cover the field of ‘popular culture’ – but an interest in unwritten texts and oral-performative culture was on the rise everywhere. From the beginning it covered various genres.

Ballads both heroic and sentimental were included (the former shading into what became known as ‘oral epic’).

The study of melodies arose later and became the object of ethnomusicology. The study (and revival) of folk-dances branched off from this, as well as more generally the ethnographic study of manners, customs and popular practices.

Wonder tales were a central concern; in the Grimmian approach, their study feeds into that of supernatural folk beliefs, soon aligned with the study of ancient myths.

This cluster of practices and concerns, usually grouped together as the study of ‘folklore’ or ‘traditional/oral culture’, would map out as shown in Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2 A mind-map of relations between genres in popular culture (square nodes) and specialisms in knowledge production (round nodes).

Grimm’s Deutsche Mythologie of 1835 was an extension of his work on the comparative grammar and history of the Germanic languages. He was hampered by the fact that there was no written corpus of German myths comparable to the Graeco-Roman or Scandinavian ones. In trying to establish what the original German system of myths had been, Grimm wanted to complement the Scandinavian myth texts with German material, and this he found in fairy tales and customs – in other words: folklore – mythologically deciphered. In his attempt to unlock oral traditions as a window on ancient myths, Grimm was applying a method (comparative-historical) that he practically patented; we have already seen him apply it to ancient literary texts and to linguistic relations. This approach examines concrete data (such as variant manuscripts, different versions of a folktale or a superstition, legal verdicts or consonants in different languages) as variable instances each of which reflects in its own way an underlying pattern, word-root or Stoff. The variant ‘expressions’ are multiple, but through their family resemblances they can be reconciled into an underlying pattern. It was in applying this method of ‘comparing expressions to elaborate the underlying type’ that Grimm had been able to come up with his archaeology of words and consonantal shifts.17

For Grimm, the comparative-historical method becomes a type of structuralism of ‘types’ generating ‘expressions’, foreshadowing the Saussurean notion that different speech acts – paroles – express an underlying language, langue. Grimm’s critical edition of the Reinhart material, going from the variants to the Stoff, exemplifies the operation of this model in the field of animal epic. In Grimm analyses of folklore materials (popular wonder tales), the motifs themselves were apparent as parts of a structure underlying the tales’ different versions; but the motifs could themselves be aligned to suggest something deeper still, something of which they were themselves the expression. In aligning folklore motifs comparatively Grimm began to go beyond the epic/folklore divide and to drill down to what he considered the deepest, and most formative layer in a nation’s expression of its world-view: its mythology.18

‘Mythology’ traditionally meant two things: either a collection of tales (muthos being the neutral Greek word for a tale, a plotline motif or an anecdote) or else a belief system – a pagan theology describing the deities, their acts and mutual relations, against the background of a cosmogony of how the world took its present shape.19 In the Romantic period, mythology developed a third meaning. Alongside the anthology (a collection of supernatural, traditionally transmitted tales) and the theology (a pagan belief system), ‘mythology’ also became a form of philology: the scholarly, academic investigation of myths. This trifurcation can be observed neatly in the core area from which the rediscovery of vernacular mythologies fanned out all over Europe: Denmark. Following Edda editions and re-editions in the later eighteenth century, N. F. S. Grundtvig addressed, philologically, what he called Nordens Mytologi (the Edda-derived set of tales); Rasmus Nyerup analysed the Edda as Skandinavernes hedenske Gudelære, a pagan belief system; and Nyerup’s study, published in 1806, cantilevered out of the more historical/antiquarian work of Fredrik Suhm, Om Odin og den hedniske Gudelære og Gudstjeneste udi Norden (1771), which treated the Edda as an originally secular historical account whose protagonists were in later treatments raised to divine status.20

Like the Greek and Roman mythologies, this Nordic material was authentically documented in ancient texts. But the mythological spin-offs elsewhere in Europe had little or no written sources to work from. Instead they drew their information from oral praxis and traditional folktales, as the run-up to Lönnrot’s Kalevala shows. Interest in Finnish oral literature had been evinced early on by Swedish intellectuals at the University of Åbo (Turku). Christfried Ganander’s Mythologia Fennica (1789) was a dictionary-style list of deities from folk religion illustrated with stanzas from Finnish folk balladry; the book already included such names as Ilmarinen and Väinämöinen, important figures in the later Kalevala compilation.

Slavic mythology, which emerged around the same time, moved in the same literary–folkloric–pagan triangle. Unlike the Finnish case, it drew on a dispersed variety of source traditions and different intellectual centres (Russian, Bohemian, Croatian); only in the mid-century, as the ideology of pan-Slavism took hold, did it converge into a common Slavic matière (Konrad Schwenck, Die Mythologie der Slawen, 1853). Folklore and oral material became available as folktales (skazki) were collected; an early researcher was the Russian army officer Andrej von Kayssarow, who published his Versuch einer slavischen Mythologie in alphabetischer Ordnung in Göttingen in 1804.Footnote *

For all this, Grimm’s Deutsche Mythologie provided a Europe-wide benchmark. Fairy tales and popular superstitions were decoded as a trickled-down residue of ancient superstitions, involving supernatural beings (dwarves, giants and elves) and reflecting ancient socio-cultural patterns such as curses, cures, rites of passage, seasonal festivals and shamanism. Supernatural beings such as dwarfs and elves, in particular, Jacob Grimm saw as things handed down from pagan times and reflecting pre-Christian beliefs and, yes, myths. Once identified as such, these mythical elements could be encountered in an astounding variety of cultural expressions.

Myths, then, are something always in the background, rather than manifestly present in solid documentation. But for all its vagueness, mythology is omnipresent in the nineteenth-century imagination; although it never quite solidified into an academic discipline, it generated enormous quantities of popular infotainment, collections of myths and legends aimed at the general public as a form of cultural archaeology for leisure-time reading. As the ancient pursuit of ‘antiquarianism’ fissioned into archaeology, linguistics and folklore, the study of vernacular mythologies came to rest, or rather wobble, on a tripod of archaeological, philological and folkloric-ethnographical approaches. These methods and fields of expertise were not easy to reconcile. As a result, mythology became both ubiquitous and vague, a diffuse and speculative background to other forms of knowledge production. Mythology was invoked to provide background ‘explanations’ for folktales, for epic, for archaeological remains, for the social history of Europe’s ancient tribal societies.

Accordingly, mythology often reverts to the genre of a quasi-scholarly anthology of ancient wonder tales; it enriches not so much the field of academic knowledge production as that of artistic inspiration. Literary raconteurs or visual artists make grateful use of the mythographers’ harvest: the proto-Czech prophetess Libuše, the Celtic Rhiannon or Manannan Mac Lír, or the Lithuanian love goddess Milda. The most outstanding example is the reception history of the Edda in German culture. The dual-track, scholarly-cum-cultural recyclings culminate in the popularizing retellings by the Germanist Andreas Heusler (Urväterhort, 1904), the poet/novelist professor Felix Dahn (Walhall, 1885) and, of course, the operatic-dramatic treatment by Richard Wagner in Der Ring des Nibelungen.21

In the post-Wagner century, the pattern is aptly illustrated by the fantasy world of J. R. R. Tolkien. As a philologist, Tolkien was a true scion of the Grimm school, doing work on the Oxford English Dictionary, editing medieval texts such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and looking for archaic elements in Beowulf. In his fascination with Old English texts, he was constantly (again like Grimm) reaching for the unspoken, mythological or archetypical traces of something underlying even ancient epic. Tolkien bitterly regretted the fact that England had no mythology of its own (much as in Grimm’s envy of the Scandinavians). In response, he created a fictional legendarium faute de mieux. True to the Grimm model, Tolkien’s philological celebration of a mythologized Englishness moved from linguistic history and language derivations (his Middle-Earth cosmogony) to legends (the Silmarillion) and epic and chivalric romance (The Lord of the Rings), with some folk-rustic hobbits thrown in for good measure. Companiable hobbits for homely folklore, aristocratic Gondor for chivalric romance, grim dwarves and Rohan warriors for epic, vanished Númenor for sagas, eternal elves for myth: it is all there, and all is held together by Tolkien’s linguistic framework. For as he famously stated, the history of his Middle-Earth was an explanatory narrative frame for him to trace the branching developments of the fictional languages he fabricated.22

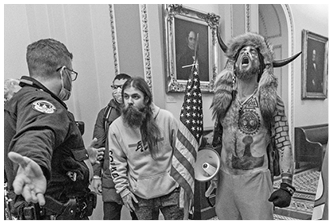

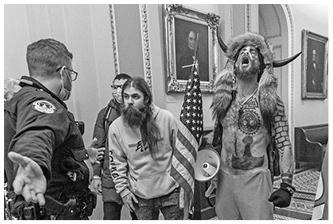

Another offshoot in the twentieth century was the resurgence of neopaganism. For those who saw Christianity as a regrettable Mediterranean/Roman/Semitic adulteration of the stalwart native morality of the Germanic Northern Europeans, ancient myth became an object of fond nostalgia; Grimm and his adepts Felix Dahn and Max Müller had repeatedly stressed the integrity of the religious and moral world-view of their Germanic ancestors, while rejecting Roman Catholicism as a hypocritical perversion. For the Germanisten of the post-Grimm generation, the pagan Saxon leader Widukind becomes a tragically doomed tribal hero, sadly overcome by the Rome-supported imperial power politics of his Frankish opponent Charlemagne. That pagan-friendly tendency ran wild in certain factions of National Socialism – notably Himmler’s SS and its cultural department, the Ahnenerbe. With the resurgence of an identitarian alt-right in post-1989 Europe, this tradition sprang back to life, often recycling – naively or knowingly – Ahnenerbe material. At the same time, a new-age type of neopaganism began to flourish, which in some manifestations (though by no means in all) harked back to a Nazi-tainted iconography, sometimes in knowing sympathy with the underlying ideology, sometimes naively, sometimes quasi-naively as a ‘dog whistle’. This repertoire of Germanic neopaganism, including runic and Nordic ornamental symbols, was also proclaimed in heavy metal rock music (‘viking metal’, which itself can shade into ‘National Socialist black metal’).23 And it showed up on the bare chest of the ‘QAnon Shaman’, a colourful participant in the storming of Washington’s Capitol in January 2021 (Figure 5.3). Wearing a horned bison headdress and carrying an American flag, he displayed on his bare chest three Germanic neopagan tattoos: the ‘Valknut’, the ‘Yggdrasil’ Tree of Life, and the ‘Mjölnir’ Hammer of Thor.

Figure 5.3 ‘QAnon Shaman’ Jacob Chansley during the 2021 Capitol riots.

The Roots of Identity

Many myths relate how the world came into being and came to be populated with gods and heroes. Chronologically, their narratives form a prequel to those of the heroic epics. For that reason, myths (as pagan religions) were held to date back to the very earliest literary products of a nation, something that came into being as that nation was going through its cultural ethnogenesis. If, in the Grimmian logic, each cultural expression emanates from an underlying cultural type, then mythology, itself a type underlying the later expressions of epic and folklore, must be the expression of the nethermost bedrock of the nation’s position in the world (that is to say, its very identity), a ‘type underlying all other types’, a cultural archetype.Footnote * There was a word for that archetype, and it had been coined by Grimm’s mentor, the legal scholar Carl von Savigny: Volksgeist, the nation’s spirit or essence.24

For Savigny and Grimm, two immediate emanations of the Volksgeist were the nation’s language and its legal customs. Grimm studies the two conjointly in his great, now neglected Rechtsaltertümer or ‘legal antiquities’, propped up by four massive volumes of documentation inventorizing the rulings of medieval case law: the Weisthümer (1840–1863). In it he analyses the historical vocabulary and the conceptual history of fundamental legal and societal principles such as ‘right’, ‘ownership’, ‘crime’ and ‘freedom’, aiming to show how the German social, moral and legal order developed in tandem with its verbal articulation, almost in tandem with the language itself. In that he proves himself the adept of his teacher Savigny, even though he chose not to follow the profession of law. It had been Savigny who had rejected Napoleonic law as an artificial, technocratic instrument of conflict and power management, an alien imposition on a Germany whose native law system had organically developed in accordance with the moral outlook of the people, a direct expression of their (as he coined the word) Volksgeist.

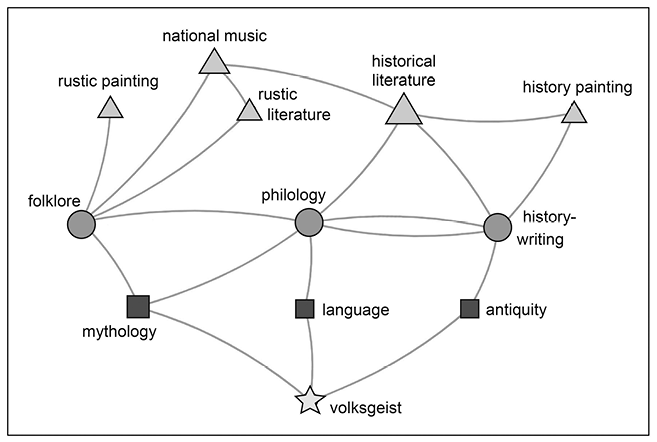

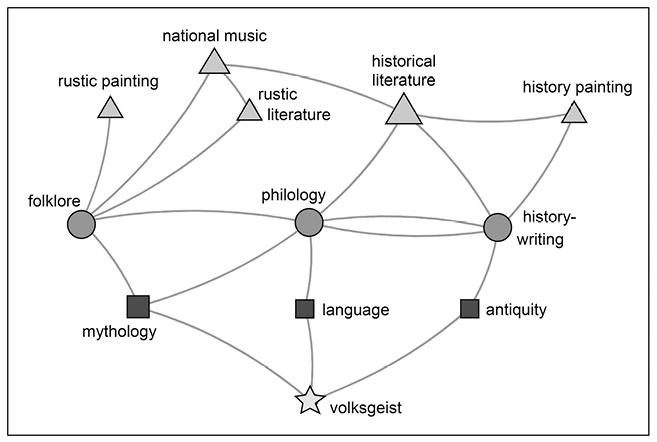

Grimm remained a lifelong adherent of this organicist notion of law. At the Germanisten conferences of 1846 and 1847 he included legal scholars alongside philologists and historians in the discipline of ‘Germanisten’: all three groups were concerned with historical manifestations of the German identity. In sum, the Romantic successors to old school antiquarianism could address three fields of deep, anthropological culture that offered them access to the nation’s primordial essence or Volksgeist: deep antiquity and ancient history;Footnote ** mythology; and language as the nation’s cultural operating system. Those fields are somewhat haphazardly divided among the scholarly disciplines of the ethnohistorian, the philologist and the folklorist, and they inspire a nation’s art in various media of expression. This is shown schematically in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4 A mind-map showing how Romantic nationalism sees the connections among cultural fields.

The triangular nodes (top tier of Figure 5.4) represent genres of artistic production and their intermedial connections; the round nodes (second tier) represent fields of knowledge production, their interdisciplinary relationships, and how they informed artistic production. The square nodes represent ‘deep culture’ (ancient, primordial or ambient) emanating from the fundamental spirit of the nation or Volksgeist (star-shaped node at the bottom), and how they are studied by the scholarly disciplines. The scheme also suggests how knowledge production takes up an intermediate, intellectual position between artistic cultural production and the ‘deep’ anthropological culture that fundamentally characterizes the nation. Only lyrical poetry, as we saw in Chapter 3, can directly intuit the Volksgeist without any intermediary or intellectual aid, thanks to its powers of visionary inspiration.

In critical writings of the nineteenth century, we frequently encounter the notion that a nation’s language is directly linked to the nation’s character, spirit or essential identity, both philosophically and in more commonplace contexts. Philosophically, the Platonic idea of language as logos was inflected by Herder’s insight that the essence of language is its capacity for diversification. For Plato, the logos is the specifically human intellectual capacity to schematize and formulate one’s sensations and thoughts into a rational position, and this is done with the tool of language, its lexical concepts and its grammatical order. Language is not a mere code system for communicating one’s ideas but a human operating system allowing one to conceptualize and articulate one’s thoughts in the first place. This language-as-logos concept was originally anthropological in the general sense, a factor that set humans (as animals endowed with sapience) apart from ‘brute’ beasts; we still encounter it in full force in Friedrich Schlegel’s Vienna lectures of 1812: ‘Spirit and language are so indivisible, as are thought and word, that, if we consider thought to be the specific privilege of humans, we must also consider the word (in its primal meaning and dignity) to be a human’s inner nature.’25 But on top of that, Herder had powerfully argued that what made human language special was also its power of proliferating diversification, its multiplicity, allowing societies in very different circumstances to each have their own logos, and if necessary their own ‘fifty words for snow’ (to quote a hackneyed phrase). The end result of this merger between Platonic idealism and Herderian diversity we see in the linguistic anthropology of Wilhelm von Humboldt, witness his Latium und Hellas (1806):

Most of the circumstances that accompany the life of a nation (residence, climate, religion, political constitution, manners and customs) can be seen separately from it, and one can, even in the case of intense interaction, distinguish between the influence they exerted and the influences they were exposed to. But one aspect is of a wholly different order, and that is language. It is the breath, the very soul of the nation, appearing everywhere in tandem with it, and (whether it be considered as something that has exerted historical influence or else undergone it) setting the limits of what can be known about it.26

Humboldt was to return repeatedly to this idea that language is both ergon (something performed, an impact) and energeia (something enabling the performance, an impetus). Language is both the expression of, and the formative impulse behind, a nation’s identity (e.g. in Humboldt’s 1836 treatise ‘On the Diversity of Human Language and Its Impact on the Mental Development of Humankind’); in due course this was to debouch into the famous Sapir–Whorf hypothesis and, anecdotally, played into the ambient ethnotypes of the century explaining national differences based on the nations’ innate ‘characters’ (see note 2 in Chapter 1).

The association between native language and national identity was also a powerful poetical trope. In his song ‘What is the German’s Fatherland?’ (see Chapter 3), E. M. Arndt answered his title question not only linguistically (wherever the German language is spoken; more on that in Chapter 6) but also characterologically and morally: ‘That is the German’s fatherland, where a clasped hand is as good as an oath, where faithfulness shines from the sparkling eye and love speaks warmly in the heart.’ This ethnotype of forthright honesty is highlighted by contrasting it with the specious deceitfulness of the French foe – for Arndt wrote this song in 1813, while the German lands were still under Napoleonic hegemony: in the German’s fatherland ‘French frippery is scornfully swept aside, every Frenchman is called a foe and each German called a friend.’Footnote * The apposition of the positive self-image and the sneering image of the Other’s innate character is glaringly illustrated here, hinting more generally at the ease with which nationalistic self-celebrations can derail into a character assassination of foreigners.27

The invocation of language as Volksgeist-determined is most strenuously made when that language is under threat, and will be encountered at its most explicit among subaltern cultural communities; I will cite a Flemish, an Irish and a Corsican example. Flemish nationalists, resisting the hegemony of French in post-1830 Belgium, are a case in point. Conscience in his novel The Lion of Flanders (Reference Conscience1838) coined the slogan Wat Wals is, vals is (‘If it is French, it is false’), and as we have seen, a patriotic-Flemish association in Ghent called itself De Taal is gansch het Volk – ‘The language is, entirely, the nation’ or ‘The language wholly marks the nation.’ That phrase had been lifted from a poem by Prudens Van Duyse, who in turn referred to Buffon’s famous ‘Le style, c’est l’homme même’ (‘A man’s style bespeaks his very personality’). In Van Duyse’s words: ‘The style wholly bespeaks the man – Buffon, those are your words: the language wholly marks the nation.’28 Grimm was to repeat the sentiment in 1846: ‘What is a Volk? A Volk is the totality of people speaking the same language.’

Indeed, in commenting on the Frenchification of Belgium, including Flanders, Grimm had in 1830 stated that giving up one’s language was tantamount to giving up one’s essential nature: ‘Any Volk that relinquishes the language of its ancestors is degenerate [entartet] and anchorless [ohne festen Halt].’ Anchorless implies that the language and its permanence are what provide a fixed, firm position for a nation in the world. Degeneracy connotes more than merely depravity or corruption: such a nation is denatured, out of touch with its inner nature and Volksgeist. Without its native/ancestral language, a nation, in Grimm’s view, has no ethical footing in the world anymore.29

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Irish nationalist poet and journalist Thomas Davis echoed the same sentiments:

The language, which grows up with a people, is conformed to their organs, descriptive of their climate, constitution, and manners, mingled inseparably with their history and their soil, fitted beyond any other language to express their prevalent thoughts in the most natural and efficient way. To impose another language on such a people is to send their history adrift among the accidents of translation – ’tis to tear their identity from all places – ’tis to substitute arbitrary signs for picturesque and suggestive names – ’tis to cut off the entail of feeling, and separate the people from their forefathers by a deep gulf – ’tis to corrupt their very organs, and abridge their power of expression. … A people without a language of its own is only half a nation. A nation should guard its language more than its territories – ’tis a surer barrier, and more important frontier, than fortress or river.30

And this is how Salvatore Viale renounced the Frenchification of Corsica in 1857 in his ‘On the use of the native language in Corsica’ (Dell’uso della lingua patria in Corsica):

And as regards love of country, which is the most powerful and necessary affection in the citizen, it should be noted that the language of a people is the complex expression of its way of thinking and feeling, of its domestic and civil customs; it is the repository, in a certain way, of its traditions, its history, its literature, all of which the homeland largely consists of. Therefore, in changing their language, a people loses their identity, or rather their personality, indeed they themselves contribute to divesting themselves of it; they therefore lose that self-esteem and awareness, that faith in themselves, in which their value lies.31

These instances from various corners of Europe are multiplied. The notion that the fundamental personality of a nation is encoded in its own language is, in the aftermath of Romanticism, one of Europe’s great cultural commonplaces. If mythology and ancient pagan belief systems bring us close to the ethnographic bedrock of the nation, the language is not only the nation’s proper, fundamental ‘operating system’ but also the container of its cultural legacies, traditions and memories. It is the main guarantor not only of its distinct position vis-à-vis other nations in the proximity of space but also of its historical permanence in the vicissitudes of time. And, more than that, the language articulates and bespeaks the nation’s essential Volksgeist.

The discourse of national identity habitually and almost in passing asserts formulaic characterizations – ethnotypes – as ‘truths universally acknowledged’: contemplative Germans, gallant French, Slavs either long-suffering or intransigent. These are not trivial asides or anecdotal parenthetical proverbs; they operate in a discourse that is suffused with invocations of the nations’ underlying temperamental proclivities, and these in turn ultimately boil down to something like a blueprint or genome, something that is so fundamental as to be almost nameless. That ineffable archetype is the perspectival vanishing point on the cognitive horizon of Romantic philologists, mythologists and folklorists. It is metaphysical: something beyond the practical or material things that are open to empirical investigation. It is gestured at by such terms as ‘identity’, ‘Volksgeist’, ‘national character’, the ‘spirit of the nation’, and it is seen as the informing principle of the nation’s mores and culture as well as the validator of the repertoire of ethnotypes. Felix Dahn summarized it in a five-line motto he composed for Alldeutscher Verband; it was to be repeatedly reproduced, sometimes in truncated form.

Making the Nation Personal: Self-Renamings

A remarkable phenomenon occurred across Europe as the modernizing states were perfecting their administrative grip on their population records. Family names became, after Napoleon, a far more fundamental part of a person’s civic identity than they had been heretofore, although their spelling remained, for most of the century, fluid (my own ancestors show up in records up to 1914 as Lerschen, Lerssen, Lersen and other tentative approximations). For members of minority cultures in multinational states, the gap between the native and the administrative rendering of the name could be considerable and could signify alienation between the state and its minority cultures. In various places we accordingly see a trend to ‘nativize’ name-forms in a deliberate rejection of official administrative usage in the hegemonic language. Sometimes this was merely a question of orthography and was retroactively imposed as new ways of spelling were established and modern standards replaced older ones: Franz Prescheren has become France Prešeren, Paul Schaffarik has become Pavol Šafárik, and the fact that Edmond de Valero morphed into the Irish statesman Éamonn De Valera is the result of a gradual adaptation to Gaelic standards as these crystallized. But De Valera’s wife, Sinéad De Valera née Ní Fhlannagáin, replaced her birth name (Jane Flanagan) with its nativist, Gaelic form in a deliberate act of self-renaming, in line with a widespread movement: Douglas Hyde himself, when writing in Gaelic, used the name-form Dubhghlas de h-Íde. A similar process spread in Finland, where Swedish name-forms were fennicized: Axel Gallen to Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Zacharias Forsman to Sakari Yrjö-Koskinen, and Einar Lönnbohm becoming the poet Eino Leino. Many Jews Hebraized their names: Eliezer Perlman and Asher Ginsberg became Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and Ahad Ha’am, David Ben-Gurion had been born as David Grün. In Hungary, many cultural activists Magyarized their names: Schedel to Toldy, Petrovics to Petőfi, Hunsdorfer to Hunfalvy, Blum to Virág, in order to signal their patriotic identification with their country (many Budapest Jews also adopting the gesture). In the 1880s a Central Name-Magyarization Society was established, encouraging people to undergo ‘national baptism’. A third crest in this wave of transnominations occurred in the period 1920–1945.33 The trend took a specific form among Czechs and Slovaks. They adopted given names of an archaic, Slavic nature, involving elements such as -slav or -mir: for example, the sports organizer Miroslav Tyrš, born Friedrich Tirsch. Among the followers of the Slovak leader Ľudovit (born Ludwig) Štúr, entire groups would undertake a pilgrimage to the historically symbolic site of Devin Castle and there choose a Slavic given name by way of ‘national baptism’.34

To some extent this activism took place on the old battle-line between the private and public spheres: names being both intensely personal and also a way of positioning oneself in society. In pre-independence Ireland, controversies ensued as to whether Gaelic name-forms could be displayed on shop-signs or used for addressing letters through the Royal Mail; this more public form of national name-contestation would of course become sharply visible in the later politics of city names, from Irish Dún Laoghaire (formerly Kingstown) to Indian Chennai (Madras). But at the same time, this was an intensely private, even intimate matter, an interiorization of the national ideal at the most fundamental level of self-identification. Private to public: what we note here is a fluid, small-to-large ‘multiscalarity’ that is particularly pronounced in language politics. Territorial multiscalarity will be discussed in Chapter 6.