Introduction

During election campaigns, political parties make dozens and sometimes hundreds of promisesFootnote 1 (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017). While extensive promise making is ideal for establishing a well‐functioning democracy because voters can use promises to hold parties accountable, parties’ incentives to bind themselves to their future behaviour seem less clear. Difficulties in the coalition formation process as well as unexpected events such as an economic crisis after an election might challenge a party's attempt to fulfil its election promises (Mansergh & Thomson, Reference Mansergh and Thomson2007; Praprotnik, Reference Praprotnik2017b). While parties fulfil a large majority of their election promises, they break on average around one of three across Western democracies (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017), which can have severe consequences as voters punish them for it (Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020; Naurin, Soroka, et al., Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019). So, if promises come with so hefty costs in terms of lost autonomy and potential electoral backlash down the road, why do parties make them to such a high extent?

To answer this question, I emphasize the enormous transformation of the political system in many Western democracies over the last 50 years. New parties have entered the parliamentary arena (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Meguid, Reference Meguid2005), old party–voter linkages have dissolved (Dalton, Reference Dalton2002; Gingrich & Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Stubager, Reference Stubager2013; Thomassen, Reference Thomassen2005) and voters today are more flexible and less loyal to specific parties than previously (Dassonneville, Reference Dassonneville2022; Hernández & Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016; Mair, Reference Mair2013). This means that parties have to operate in a more unpredictable context where they increasingly compete on setting the common political agenda and have to change their issue profile more frequently (Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2007, Reference Green‐Pedersen2019). I argue that parties, because of these major changes in the political landscape, can use policy commitments to gain credibility in the increasing competition for votes.

I define commitments as statements in which a party takes high responsibility for a future policy (for instance, by saying ‘We will increase [X]’ or ‘We promise to implement [Y]’). Exactly because promises are electorally costly if not fulfilled later (Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020), they are also credible signals to voters about the sincerity of parties’ intentions. Since a party is punished if it breaks its promises after an election, voters can have higher expectations that the party will follow through on its campaigned policies (Bonilla, Reference Bonilla2022; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017). Therefore, I expect that parties will use commitments to try to gain credibility when this is highly needed (see also Vestergaard, Reference Vestergaardforthcoming). Specifically, I make four hypotheses: First, parties make a higher share of commitments today than previously because of the transformation of the political landscape (a time trend). Second, parties competing in countries with a large effective number of parties will feel a stronger pressure to commit (system‐level factor). Third, mainstream parties will make a higher share of commitments in response to the emergence of niche parties (party‐level factor). Fourth, parties will make a higher share of commitments on issues to which they previously paid limited attention (issue‐level factor).

Testing these expectations systematically is not straightforward as we lack a comprehensive dataset that allows us to study how parties strategically formulate promises across political issues and countries. Existing research either focuses on categorizing issues in political texts without considering how parties talk about each issue (see the Comparative Manifesto Project, Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020) or code the number of promises without considering the issues on which the promises are made (Naurin, Royed, et al., Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019). I bridge these two approaches by developing a novel dataset that identifies commitments within specific issues. The dataset is also suitable for testing expectations at the manifesto level (i.e., the hypotheses related to the time trend, system‐level factor and party‐level factor).

To be able to identify commitments and combine them with the issue coding from previous research, I take advantage of a state‐of‐the‐art language model. Even though these models have improved considerably in recent years (with the invention of models such as ELECTRA, ChatGPT and LLaMA), we are not sure about their ability to identify complex political concepts like commitments. Therefore, I first developed a coding scheme that outlines how commitments can be identified within each quasi‐sentence (Vestergaard, Reference Vestergaard2023). Second, human coders applied the coding scheme to manually categorize 65,630 quasi‐sentences on different codes, so each quasi‐sentence could be categorized as containing or not containing a commitment. Third, I used a large part of these quasi‐sentences to train the language model to automatically code a total of 330,850 quasi‐sentences. A main advantage of the coding scheme is that I have tested the reliability of and achieved high scores on both human and machine coding, which leaves me with a highly reliable dataset that shows great validity and covers 11 Western democracies across four decades of elections. The dataset enables me to study how parties use the policy‐committing strategy (measured as the share of commitments within an issue) under different electoral circumstances and over time.

Employing the new dataset in this paper, I find support for three out of four expectations: Parties have increased their use of the policy‐committing strategy over time; mainstream parties make a higher share of commitments than niche parties; and parties use the policy‐committing strategy more intensely as an issue becomes increasingly salient to them. This latter finding not only means that parties make more commitments when they write more quasi‐sentences on an issue (which would be rather unsurprising); parties make a higher share of commitments on the issue (which is more demanding than just raising the number of commitments) when they have increased their emphasis on the issue, suggesting that parties put more effort into appearing serious and determined on an issue to compensate for their previous lack of attention to it. I do not find support for the expectation that parties with more competitors will make a higher share of commitments. On the contrary, they use the policy‐committing strategy less, which I will discuss in the concluding section.

The results from this paper are crucial because they shed light on key factors influencing the emergence of parties’ commitments. Previous research has mainly been interested in the effects of election promises, which strongly influence policymaking (Naurin, Royed, et al., Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017), voters (Bøggild & Jensen, Reference Bøggild and Jensen2023; Elinder et al., Reference Elinder, Jordahl and Poutvaara2015; Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020; Naurin, Soroka, et al., Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019) and media coverage of politics (Duval, Reference Duval2019; Müller, Reference Müller2020). However, until now, we have not had a theory of why parties even make these promises. This study shows that parties can use policy commitments to try to gain credibility in an increasingly competitive political landscape. To predict the policies of tomorrow, we, therefore, have to understand the parties’ need for credibility today.

Theory

A transformation of the political landscape

In many Western democracies, political parties have witnessed a significant transformation of the political landscape, especially within recent decades. Several new parties have emerged, typically with a niche focus on issues such as immigration, climate or regional independence (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Meguid, Reference Meguid2008). The old parties have experienced that their traditional voters have disappeared or are much less loyal, and the historical linkages between social class and vote choice have weakened (Dalton, Reference Dalton2002; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Stubager, Reference Stubager2013; Thomassen, Reference Thomassen2005).

New connections between voters and parties may have appeared, but voters are still much more flexible in their party choice than previously. They change party from election to election (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, McAllister, Wattenberg, Dalton and Wattenberg2000; Dassonneville, Reference Dassonneville2022; Mair, Reference Mair2013), and they do not decide their vote choice before the election campaign starts and oftentimes not until the very last days of the campaign (Box‐Steffensmeier et al., Reference Box‐Steffensmeier, Dillard, Kimball and Massengill2015; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, McAllister, Wattenberg, Dalton and Wattenberg2000; Irwin & Van Holsteyn, Reference Irwin and Van Holsteyn2008). Furthermore, parties increasingly compete on issues in an attempt to set the common political agenda (Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2007). Parties can try to raise different issues on which they have an advantage, but they also have to emphasize issues that are outside their primary focus because it is on the agenda of the other parties or the electorate (Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010; Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014).

These empirical developments have changed the arena in which political parties operate. The consequences of having more parties, more flexible voters and more issue competition are twofold: The competition for votes has increased, and election campaigns have become more important. How can parties respond to these developments in a way that attracts voters? Below, I argue that the policy‐committing strategy is particularly useful in this new political landscape.

A costly signal

A statement includes a commitment when a party takes high responsibility for a future policy. The party links itself to the provision of a policy by saying that it will make sure that the policy will be implemented.Footnote 2 Commitments can increase the credibility of a party's policy programme because they help voters hold the party accountable at the next election. This should enhance voters’ confidence that the party will keep its word and pursue its stated policy plans. Empirically, voters do increase their expectations of policy implementation when parties have made a promise on it (Bonilla, Reference Bonilla2022), and parties, generally, gain votes by making promises (Bøggild & Jensen, Reference Bøggild and Jensen2023; Elinder et al., Reference Elinder, Jordahl and Poutvaara2015). A commitment should be even more valuable to voters today than previously as post‐election government negotiations have become more difficult and unpredictable (for instance, the number of days until a government is formed is higher today, see Online Appendix B). By making a commitment, a party signals to voters that they are willing to prioritize the policy in these complex negotiations.

Even though parties can profit by making commitments in the short term, they limit their flexibility in the long term because they will have to fulfil them after the election. Predicting a party's likelihood of keeping its promises is notoriously difficult, as there are many steps between the formulation of a promise and actual policy implementation: Election results are unknown as is the outcome of government formation, especially if it includes a coalition of several parties (e.g., De Winter & Dumont, Reference De Winter, Dumont, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Golder, Reference Golder2010). In the legislative arena, a party often has to negotiate with other parties and make compromises, which eventually means breaking its pre‐electoral promises (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017). Finally, unforeseeable crises can make specific policies more demanding to implement than a policy promised before an election (Praprotnik, Reference Praprotnik2017b).

If parties break their promises, they are likely to attract negative media coverage (Duval, Reference Duval2019; Müller, Reference Müller2020) and risk that voters punish them in the next election. Empirically, Matthieß (Reference Matthieß2020) finds that parties lose a higher share of votes the more pledges they break. Voters also evaluate parties more negatively when pledges are broken (Naurin, Soroka, et al., Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019). While electoral punishment does not necessarily translate into a loss of seats, policymaking power or government offices (this depends on party characteristics and institutional settings such as the electoral system and party system; see Kam et al., Reference Kam, Bertelli and Held2020), we should expect that losing votes, all else equal, is harmful to a vote‐seeking party. Making promises is thus potentially electorally costly in the long term, and parties should save the strategy for situations in which they are in high need of credibility in the short term.

In sum, the policy‐committing strategy provides prospects and perils to parties that need to adapt to changes in their environment. While promises limit the parties’ manoeuvrability after the election, the pressure to make commitments has grown in recent decades due to the developments mentioned above. Making commitments can be a way for a party to attract voters by making its policy programme more credible. Therefore, I expect a time trend in the use of the policy‐committing strategy:

Time trend hypothesis: The share of commitments has increased over time.

However, the pressure to commit has not necessarily increased homogenously across contexts but may depend on the specific party system, party type and issue on which a party campaigns. Below, I elaborate on these factors and their influence on parties’ use of the policy‐committing strategy.

System‐level differences: The importance of commitments in complex negotiation environments

The number of political parties has generally increased over time, usually measured as the effective number, which takes each party's relative strength into account (Best, Reference Best2013; Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, McAllister, Wattenberg, Dalton and Wattenberg2000; De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries, Hobolt, Velasco and Bucelli2022). Particularly, this development has happened in countries with proportional voting systems as they are more permissive than systems with plurality voting (Duverger, Reference Duverger1959).

When the number of parties in a political system increases, the competition for votes intensifies, all else equal. Moreover, a higher number of parties also has consequences for the period after the election. For instance, the number of parties in a system is positively associated with the level of fractionalization within a government (Valentim & Dinas, Reference Valentim and Dinas2024). Furthermore, the negotiation period is typically more complex and lasts longer until a government is formed because parties have to get to know each other's preferences and more parties might disagree (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Hellström, Lindvall and Teorell2024; Golder, Reference Golder2010). Consequently, the successful implementation of a party's policy programme also becomes more uncertain. For instance, if parties are trying to form a coalition, and they disagree on an issue, they may use the written agreement to make compromises (Eichorst, Reference Eichorst2014; Klüver et al., Reference Klüver, Bäck and Krauss2023; Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011). In a coalition government, parties also have to allocate ministerial offices, and a minister from the other party may pursue policies that are against the coalition partners’ interests (Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996; Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011).

From the electorate's perspective, voters should value policy commitments more when implementation of a policy programme becomes more uncertain in a system with more political parties. The party signals that despite the complex political environment, it is very determined to pursue its policies, to prioritize the policy and to put its trustworthiness at stake. Parties can thus make their election programme more credible by using the policy‐committing strategy.Footnote 3

To sum up, since a larger number of parties increases competition before elections and uncertainty about policy implementation after, parties should be more likely to make commitments in a highly fragmented party system to attract voters:

System‐level hypothesis: The share of commitments will be higher when the effective number of parties increases.

A particular type of party, usually referred to as niche parties (e.g., Meguid, Reference Meguid2005), has emerged in these increasingly fragmented party systems and challenges established mainstream parties. Below, I argue that the pressure to commit is uneven across the two types of parties.

Party‐level differences: How a party's mainstream status affects the usefulness of the policy‐committing strategy

During the 1980s, green parties and anti‐immigration parties gained prominence among voters at the expense of mainstream parties such as conservatives, social democrats and liberals (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). Green parties and anti‐immigration parties are often defined as niche parties as they mainly focus on a specific niche issue (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). Their advantage is that they can appear very determined and principled on their core issue and attract voters who find this issue important as well (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996; Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014). Typically, they are more extreme on their positions, follow the preferences of their supporters and attract voters by appearing principled and motivated by policy (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Ezrow et al., Reference Ezrow, De Vries, Steenbergen and Edwards2011; Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2016). In contrast, mainstream parties usually cover several issues and may appear less determined on specific issues, yet they appeal more broadly (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Bergman & Flatt, Reference Bergman and Flatt2020; Greene, Reference Greene2016; Van Heck, Reference Van Heck2018). While several studies have shown that mainstream parties may respond to the emergence of niche parties at the issue level (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Meguid, Reference Meguid2008), I argue that mainstream parties can use a strategy at the programmatic level, namely the policy‐committing strategy. By making commitments, mainstream parties can try to appear credible and determined in their policy programme and thus counterbalance the positive reputation of niche parties as more principled and policy‐seeking.

Another argument for making commitments is that the mainstream party highlights its own status as government potential. Mainstream parties are typically government actors, while niche parties usually stay in opposition (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). By making commitments, a government‐aspiring party signals to voters that if they vote for the party, its policy preferences are more likely to be implemented as their support will translate into a potential future government party.

In sum, I expect that mainstream parties are more likely to use the policy‐committing strategy as a response to the relatively new phenomenon of niche parties; both to challenge the status of niche parties as more principled and to highlight their own status as a more likely government party:

Party‐level hypothesis: Mainstream parties make a higher share of commitments than niche parties.

As already hinted in the previous section, issue emphasis is an important way parties compete against each other and a way for scholars to distinguish between parties. However, to understand parties’ pressure to commit, we also need to focus on specific issues and the general dynamics of issue competition. This is the purpose of the next section.

Issue‐level differences: How parties need credibility when changing issue emphasis

Political parties increasingly compete on political issues (Greene, Reference Greene2016; Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2007). Even niche parties are broadening their issue appeals (Bergman & Flatt, Reference Bergman and Flatt2020; Meguid, Reference Meguid2022; Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2013). Parties will try to force their competitors to focus on their issue agenda and at the same time be constrained by the common party system agenda (Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010). Increased issue competition implies that parties sometimes have to emphasize issues they did not talk much about previously at the expense of issues they used to prioritize.

A major cost of changing issue priorities is the loss of credibility. A party's credibility comes from many years of dedication to an issue (Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). When a party shifts attention from one election to the next, it loses its political identity (Janda et al., Reference Janda, Harmel, Edens and Goff1995) and has no reputation on its new issue agenda (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Tresch and Lefevere2015). Changing the political package can therefore be harmful to the party (Meyer, Reference Meyer2013, p. 10; Volkens & Klingemann, Reference Volkens, Klingemann, Luther and Müller‐Rommel2002, p. 145). Voters are sceptical about the party's ability and willingness to solve the problems they suddenly begin to worry about and will eventually perceive its change in viewpoints as opportunistic and dishonest (Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012). Voters prefer parties that are consistent and reliable, so when a party changes its profile voters may respond negatively (Ansolabehere & Snyder, Reference Ansolabehere and Snyder2000; Groseclose, Reference Groseclose2001).

Therefore, a party mainly changes its emphasis if it is forced to, for instance, if it has lost an election or is trailing opposing parties and wants to be more responsive to the voters’ priorities (Damore, Reference Damore2004; Janda et al., Reference Janda, Harmel, Edens and Goff1995; Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2013; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2014). Alternatively, the party may have to focus on new issues if other parties have placed them on the agenda (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2010; Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). If some problems become too large to ignore, parties may have to respond by increasing their focus on the issue (Baumgartner & Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2010; Dalmus et al., Reference Dalmus, Hänggli, Bernhard, Van Aelst and Walgrave2017; Kristensen, Reference Kristensen2020; Seeberg, Reference Seeberg2021). In these cases, the party must convince voters that it can deliver credible solutions to problems it did not pay much attention to before. Voters might be sceptical about the party's intentions and be unsure whether it will pursue the policies after the election because it has no record on these matters. The party must compensate for a lack of credibility by signalling that it is trustworthy on its new political agenda, and this is where the policy‐committing strategy becomes important.

By making commitments, parties signal to voters that their new priorities are credible. While they risk losing credibility when they abruptly focus on political problems they previously ignored, parties can attempt to regain the electorate's trust by constraining their future behaviour. They commit themselves to solving the problems they pay attention to. When parties use the policy‐committing strategy to rebrand their political images, they exchange flexibility in the future policymaking phase for voter credibility in the current campaign phase:

Issue‐level hypothesis: When parties have increased the saliency of an issue, they will make a higher share of commitments on the issue.

To test the four hypotheses, I developed a large cross‐national dataset that identifies parties’ use of commitments in 11 countries. In the next section, I will elaborate on the data collection process.

Method

Data source and case selection

Parties’ election promises have been identified in research, but they have never been measured within parties’ issue agendas in a cross‐country design (for one‐country studies, see Praprotnik, Reference Praprotnik2017a; Praprotnik & Ennser‐Jedenastik, Reference Praprotnik and Ennser‐Jedenastik2023), perhaps because it is difficult to identify promises systematically (Naurin, Royed, et al., Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019).Footnote 4 To test my argument, I developed and tested a coding scheme that produces high‐quality human coding (see more details about this part in Vestergaard, Reference Vestergaard2023) that could subsequently be used to train a language model to code unknown material and allowed me to use machine coding to include several countries. The final dataset gives me an overview of parties’ use of policy commitments across 11 countries covering four decades. I will explain the coding process in detail later, but first, I will describe the data source and case selection.

I tested and used my coding scheme on election manifestoes, which are, in a sense, contracts between parties and voters. Parties also make commitments on other platforms, such as social media, websites, political ads and television, but they announce their political visions in the manifesto, including their views on the most pressing problems and their solutions to them, and voters indirectly sign the contract by their vote on the election day. There are many steps between an election campaign and actual policy enactment after an election (for instance, the election itself, negotiations between parties, government formation and parliamentary debates about policy bills), and the manifesto works as a written agreement that voters can use to remind the party about its promises. In this way, manifestoes establish an important link of accountability between parties and voters and are used in most studies on election promises (e.g., Artés & Bustos, Reference Artés and Bustos2008; Naurin, Royed, et al., Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019; Thomson, Reference Thomson2001). Another benefit is that I can use manifestoes to track parties’ political agendas across countries and over time and test the issue‐level hypothesis. In particular, I can measure party agendas and commitments from the same data source, which is advantageous since I assume that parties base their policy‐committing strategy on a total set of considerations, including how salient they find different issues.

The analysis includes 11 countries with different institutional characteristics: United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), Australia (AU), Canada (CA), New Zealand (NZ), Switzerland (CH), Germany (DE), Luxembourg (LU), Austria (AT), Ireland (IE) and Denmark (DK). Diversity in terms of political setting is crucial because it affects parties’ incentives to make commitments as argued in the theory section. Most importantly, the countries differ regarding the number of parties normally represented in the parliamentary arena, ranging from a pure two‐party system like the United States to a pure multi‐party system like Denmark. Moreover, the countries vary in terms of the typical type of government and the executive–legislative relation, which are added to the analysis as control variables (see below). Online Appendix C provides an overview of differences and similarities between the 11 countries on these three institutional characteristics.

By including a diverse set of countries in the analysis, I also increase the likelihood that the results from this study can be generalized to countries with varying types of party dynamics and institutional setups. I include all available election manifestoes from the 11 countries in the corpus of the Comparative Manifesto Project (Burst et al., Reference Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Lewandowski, Matthieß, Merz and Zehnter2020); see Online Appendix D.

Dependent variable

Coding process

To identify commitments in quasi‐sentences, I had to classify each text unit based on whether the party mentions any future policy, and whether the party takes high responsibility for these future policies. These two aspects affect whether a political statement is considered a policy commitment.

The coding process involved (1) developing a new coding scheme, (2) training eight human coders and testing the reliability of their coding, (3) human coding 65,630 quasi‐sentences, (4) training a machine (using the ELECTRA model) on the human coded quasi‐sentences and (5) machine coding 330,850 quasi‐sentences. During this process, I tested the reliability of both human and machine coding, which showed great results (kappa/Krippendorff's alpha values of at least 0.81, and F 1 of at least 0.88). For a full overview of the coding process, including the coding scheme, the human coding phase, the machine coding phase and reliability tests, see Online Appendix J.

Measuring the policy‐committing strategy

After having identified commitments in election manifestoes, I calculated how committed the party was. This could be done at the manifesto and issue level. For the first three hypotheses, both measures were used, but only the issue‐level measure made sense for the fourth hypothesis to test the expected issue dynamics.

At the manifesto level, I simply calculated the share of commitments relative to the total number of quasi‐sentences. I measured this as a percentage. The formula that measures the share of commitments (SC) is

where C is the number of quasi‐sentences that includes commitments and N is the total number of quasi‐sentences in the manifesto.

At the issue level, I made this calculation within issues. The formula then becomes

where i is the issue, C is the number of commitments and N is the number of quasi‐sentences.

The Comparative Manifesto Project has already coded each quasi‐sentence on the issue dimension, so I used their coding to measure the share of commitments at the issue level (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020). Their dataset has 56 main categories and several subcategories. To avoid too many issue categories, I grouped the codes (e.g., per104 ‘Military: Positive’ and per105 ‘Military: Negative’ in one military issue, and per303 ‘Governmental and Administrative Efficiency’ and per304 ‘Political Corruption’ in one bureaucracy issue) into 24 issues: agriculture, bureaucracy, centralization, civic‐mindedness, constitutionalism, culture, democracy, EU, economic groups, economy, education, environment, equality, foreign policy, internationalism, law and order, military, morality, multiculturalism, national way of life, non‐economic groups, protectionism, technology and infrastructure and welfare. In Online Appendix E, I show which codes from the Comparative Manifesto Project I grouped into the broader issue categories. In Online Appendix H, I tested the robustness of my findings with a more minimal grouping of issue codes (43 issue categories).

The descriptive statistics of the variable reveal that around 14 per cent of the quasi‐sentences within an issue contain policy commitments (see Table 1 for more details). This suggests that commitments are indeed a costly signal that parties are hesitant to use and that parties also use election manifestoes for other purposes than making commitments.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of variables

Note: The descriptive statistics are based on the observations included in Model II in the analysis (measuring the share of commitments at the issue level).

Primary independent variables

I have four independent variables, one for each hypothesis. To measure the potential time trend, I used the year of the election as the main variable.

To measure the effective number of parties, I relied on a variable from The Comparative Political Data Set that measures the number at the vote level (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Engler, Leemann and Weisstanner2022). They follow the formula proposed by Laakso and Taagepera (Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979) that takes each party's vote share into account when calculating the total number of parties.

The third main independent variable is related to the status of a party as either mainstream or niche. Traditionally, this has been done by categorizing parties based on their party family. Even though more recent accounts base the decision on a more nuanced measure of a party's communication style and issue profile (Bischof, Reference Bischof2017; Greene, Reference Greene2016; Meyer & Miller, Reference Meyer and Miller2015; Wagner, Reference Wagner2012), the party family approach is still largely used (e.g., Gunderson, Reference Gunderson2023; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2019) and was chosen here to not confuse the party‐level variable with the fourth independent variable of saliency change. Thus, mainstream parties belong to the party family of Christian democrats, conservatives, liberals or social democrats, while niche parties are all other party families (the categorization into party families is from the Comparative Manifesto Project; see Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020).

Regarding the fourth independent variable, I measured saliency change at the issue level making use of the Comparative Manifesto Project's coding of election manifestoes (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020). As a first step, I calculated the number of quasi‐sentences a party devoted to a specific issue relative to the total number of quasi‐sentences in the manifesto. Specifically, I used Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011)’s formula to calculate saliency (Sa):

where i is the issue, Se is the number of quasi‐sentences within an issue i and N is the total number of quasi‐sentences in the manifesto.

By using the logarithmic measure, I take into account that an increase in saliency means more when a party puts less emphasis on an issue (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011). Increasing emphasis on an issue from 1 per cent to 2 per cent of the manifesto represents a larger boost in saliency than increasing the emphasis from 50 per cent to 51 per cent. This logarithmic measure of saliency is scaled in such a way that the less negative it is, the more salient the issue is to the party.

As a second step, I measured the change in saliency from one election to the next by subtracting the saliency of an issue at the current election from the saliency at a previous election. In most cases, saliency is available for the previous election, but, if not, I take the most recent available election (except if the previous election was more than 10 years ago). Thus, positive values mean that a party increased the saliency towards the current election (the more positive, the more salient), and negative values mean that a party decreased the saliency (the more negative, the less salient).

Estimation strategy and control variables

In the analysis, I used negative binomial multivariate regression models with robust standard errors, which are suitable when the dependent variable has a count‐like structure,Footnote 5 follows a negative binomial distribution and is over‐dispersed (i.e., the mean is considerably lower than the variance). I ran two models, one using the policy‐committing strategy at the manifesto level and one at the issue level. In both models, I included government status (based on ParlGov, see Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2021) before the election as a control variable. Government experience matters both for parties’ issue agendas and the extent to which they communicate prospectively about policies and make promises in their manifestoes (Müller, Reference Müller2022; Praprotnik & Ennser‐Jedenastik, Reference Praprotnik and Ennser‐Jedenastik2023; Van Heck, Reference Van Heck2018).

Regarding country‐level controls, I added, first, a variable on the executive–legislative relations within the country (i.e., a presidential system or a semi‐presidential/parliamentary/hybrid system) and, second, a variable on the type of government at a given election (single‐party majority, minimal winning coalition, surplus coalition, single‐party minority government or multi‐party minority government). Like the effective number of parties, these institutional differences might affect a party's incentive to make commitments as well as constrain its ability to pursue its preferred policies after an election (e.g., a minority government needs support from other parties to implement its policies). These two variables are from the Comparative Political Data Set (Armingeon et al., Reference Armingeon, Engler, Leemann and Weisstanner2022).

In the issue‐level model, I included issue dummies to control for unique issue‐specific characteristics. Furthermore, it is important to control for the current saliency of an issue, since higher saliency generally makes it more demanding to achieve a high share of commitments irrespective of how much the party changed the saliency since the previous election (e.g., if it has written 10 quasi‐sentences on an issue, it only has to make commitments in five of them to achieve a 50 per cent share of commitments, while it has to commit in 50 quasi‐sentences if it has written 100 quasi‐sentences on the issue to achieve the same share).Footnote 6 Similarly, I controlled for overall issue engagement at the previous election (i.e., whether the party talked about the issue). Other potential issue‐level controls would be the inclusion of voter agendas as well as problem indicators since these could affect parties’ incentives to change their issue focus (as argued in the Theory section). However, it is difficult to get data on these measures that can be easily matched with the issues from the Comparative Manifesto Project. Furthermore, it is not easy to specify the model with these controls, as parties’ saliency change might both be the result of voters’ agendas and different problem indicators and the cause of these.

In Table 1, I give an overview of the descriptive statistics of the dependent variable as well as the four main independent variables in the analysis. The statistics are based on Model II. In Online Appendix G, I show the descriptive statistics of all variables and from each of the two models.

Results

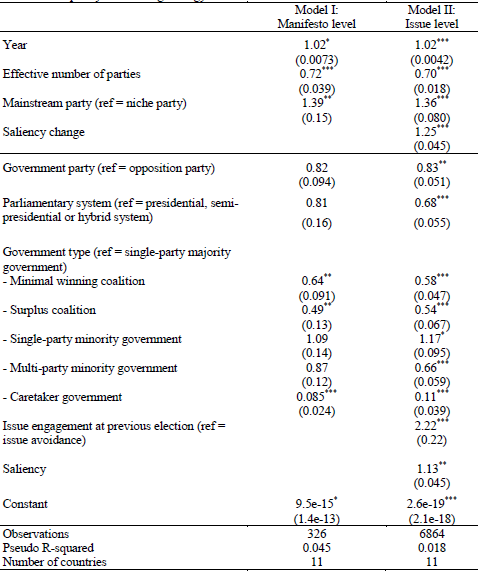

In the analysis, I test each of the four hypotheses in turn based on the results in Table 2, which consists of two models. In the first model, each observation is at the manifesto level (i.e., the share of commitments within manifestoes); in the second model, each observation is at the issue level (i.e., the share of commitments within issues). Notice that the coefficients are shown as incidence rate ratios, that is, values above 1 suggest that the effect is positive and values below 1 indicate negative effects. For each of the primary independent variables, I will supplement the analysis with a figure of the marginal effects to better interpret the results.

Table 2. The policy‐committing strategy and its causes

Note: Based on negative binomial regression models with robust standard errors. The beta‐coefficients illustrate the incidence rate ratios (the constant is the baseline incidence rate). Coefficients of issue dummies are not shown (only used in Model II).

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Time trend hypothesis

As shown in Table 2, there is a positive and significant time trend (illustrated by an incidence rate above 1), suggesting that political parties make a higher share of commitments in recent elections compared to previously. The incidence rate of 1.02 in both models means that a party has increased its share of commitments by a factor of 1.02 per year.

As illustrated in Figure 1, this is a substantial effect. Based on the predicted values, a party doubled the share of commitments within manifestoes from the start until the end of the period under study in this paper. While policy commitments were present in around 1 out of 10 quasi‐sentences in 1984, this was the case in around 1 out of 5 in 2019. Thus, the time trend hypothesis finds support in the data.Footnote 7

Figure 1. The use of policy commitments in election manifestoes over time.

Note: Negative binomial regression; see Table 2 (Model I). Confidence intervals are at the 95 %‐level.

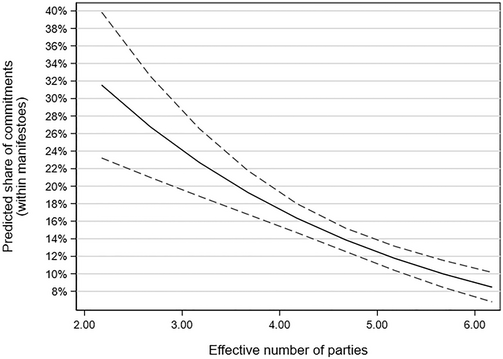

System‐level hypothesis

Looking at the second primary independent variable, the coefficients in both Models I and II are significant and below 1 (the incidence rate ratio is 0.72 and 0.70, respectively). This suggests, contrary to the expectation, that the share of commitments parties make decreases as the effective number of parties increases.

Figure 2 shows that the effect is remarkable. In two‐party systems, parties make a commitment in almost every third quasi‐sentence, which drops to less than every 10th in multi‐party systems with more than six parties (measured as the effective number). Since I do not find support for the system‐level hypothesis, I will discuss this result in more detail in the concluding parts of the paper.

Figure 2. The use of policy commitments as a response to the effective number of parties.

Note: Negative binomial regression; see Table 2 (Model I). Confidence intervals are at the 95 %‐level.

Party‐level hypothesis

The third hypothesis focuses on party differences, specifically the difference between mainstream and niche parties. The expectation that mainstream parties will make a higher share of commitments than niche parties is supported by the coefficients in Table 2. The incidence rate ratios are 1.39/1.36 in the two models, meaning that the share of commitments increases by a factor of 1.39/1.36 when we move from niche parties to mainstream parties. As the predicted share of commitments is 13.39 per cent for niche parties, the share for mainstream parties is 1.39/1.36 times higher (i.e., a predicted share of commitments around 18,67 per cent; see Figure 3). Thus, I find support for the party‐level hypothesis.

Figure 3. The use of policy commitments by mainstream and niche parties.

Note: Negative binomial regression; see Table 2 (Model I). Confidence intervals are at the 95 %‐level.

Issue‐level hypothesis

The final hypothesis is at the issue level. To reiterate, I expect that parties will make a higher share of commitments when they have increased the saliency on an issue. As shown in Model II of Table 2, I find support for the hypothesis. The independent variable goes from a large decrease in saliency to a large increase in saliency and changing from lower levels to higher levels on this variable increases the share of commitments. The incidence rate ratio is 1.25 and significant, meaning that when a party increases the logged saliency (or decreases the logged saliency to a lesser extent) by one scale point (the variable ranges from −5.84 to +4.99), the party increases the share of commitments by a factor of 1.25.

Figure 4 illustrates the main effect with predicted values of the dependent variable, specifically the predicted share of commitments across different levels of my independent variable (i.e., saliency change). From a very low value of saliency change (observation at the 10th percentile), that is, a high decrease in saliency, to a very high value of saliency change (observation at the 90th percentile), that is, a high increase in saliency, the share of commitments increases from around 11 per cent to more than 20 per cent. This reveals the substantial effect of saliency change on the use of the policy‐committing strategy.

Figure 4. The use of policy commitments after changing the saliency of an issue.

Note: Negative binomial regression; see Table 2 (Model II). Confidence intervals are at the 95 %‐level. ‘High decrease in saliency’ is −1.32 (10th percentile). ‘High increase in saliency’ is 1.30 (90th percentile).

Discussion

The main argument in this paper is that parties make commitments to gain credibility in the competition for voters. As the electorate considers commitments to be a more honest signal of a party's future intentions than a more vague declaration, parties can try to increase their own credibility with these promises (Bonilla, Reference Bonilla2022). However, as I have emphasized, parties should use the policy‐committing strategy with caution. The parliamentary and governmental situation after an election is difficult to predict, and if circumstances make it impossible for a party to keep its promises, it risks being punished at the next election (Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020; Naurin, Soroka, et al., Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019). Thus, parties must weigh two key considerations when deciding how much to commit: either they make heavy use of commitments to enhance the short‐term credibility of their electoral programme, or they adopt more modest language to preserve their flexibility after the election.

In recent elections, parties have been increasingly pressured to make a higher share of commitments. As I have argued, this might be a result of the changing political landscape with less loyal voters and stronger electoral competition (Dassonneville, Reference Dassonneville2022; Dassonneville & Hooghe, Reference Dassonneville and Hooghe2017; Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2007, Reference Green‐Pedersen2019; Mair, Reference Mair2013). I have found that mainstream parties make a higher share of commitments than niche parties, which might be a way for the old parties to respond to the new challengers (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). Moreover, parties make more use of the policy‐committing strategy when they have increased their emphasis on a political issue, which points to the relevance of the policy‐committing strategy as issue competition has intensified (Green‐Pedersen, Reference Green‐Pedersen2007, Reference Green‐Pedersen2019). While parties might increase the saliency of an issue for various reasons as highlighted in the theory section, the results show that parties generally follow up on this change by increasing their commitment to the issue. Future research could examine whether the reason for this saliency change (e.g., voter pressure, pressure from other parties or the emergence of a crisis) affects the extent to which parties make use of the policy‐committing strategy. If parties that already have a strong reputation on an issue push another party to pay attention to the issue, the focal party might be more likely to make commitments to try to gain credibility than if a crisis suddenly occurs. If a crisis like the covid pandemic happens out of the blue, voters might be more forgiving about the fact that the party did not pay much attention to the issue before the pandemic.

One result in the analysis was striking: Parties, in general, do not make a higher share of commitments in systems with several competitors compared to systems with fewer. My expectation was that a party would feel more pressure to commit in systems with many other parties because competition for votes is higher and because commitments signal determination if the government formation and policymaking processes after an election are likely to become difficult. Yet, in multi‐party systems, a party's need for manoeuvrability in post‐election negotiations appears to dominate and counter‐act the pressure on the party to commit in a highly competitive election. When there are more parties, uncertainty about the parliamentary and governmental situation after the election is simply too high, even if the party would be better able to attract voters in the short term by gaining credibility from these commitments.

Another reason for this striking finding might stem from the fact that the share of commitments was measured at the party‐level (within each election manifesto). When looking at the issue level, research has shown that parties do make more commitments when they are positionally closer to other parties (Vestergaard, Reference Vestergaardforthcoming). This would suggest that it is not an increase in the effective number of parties per se that pressures parties to make use of the policy‐committing strategy but the degree of positional similarity between competing parties.

What do these four findings in combination tell us about the use of the policy‐committing strategy in the transformed political landscape that I sketched in the front‐end of this paper? The simple conclusion would be that the increasing use of the policy‐committing strategy over time comes from mainstream parties in systems with few parties that have been increasingly pressured to recalibrate their agendas to focus on new issues (raised by the newly formed niche parties) and as a result make more commitments to appear credible. However, when the number of niche parties escalates and the effective number of parties goes (too much) up, the post‐election coalition‐building processes become so unpredictable and complex that these mainstream parties reduce the use of the policy‐committing strategy to keep a certain room of manoeuvrability in these negotiations.

However, as written, this conclusion would be too simple. That mainstream parties make more use of the policy‐committing strategy than niche parties does not mean that the latter does not make use of commitments at all. Sometimes, these parties might also have to reorient their issue focus and need the commitment strategy to remain credible (for instance, when a crisis occurs). Similarly, that parties in systems with several competitors make less use of commitments than in systems with a few does not mean that parties under these contextual conditions do not use the strategy at all. Some elections and government negotiations might be more predictable, making it less risky for parties to commit themselves to their future behaviour. Some parties might be so similar in their viewpoints, pressuring them to make more commitments to stand out (Vestergaard, Reference Vestergaardforthcoming). This discussion illustrates how many different considerations might enter parties’ calculations when they decide when, to which extent, and on which issues they will make use of policy commitments. Exploring empirically how these considerations – that exist at different analytical levels – interact with each other is a key task for future research.

The results of this paper are important not only for our understanding of party competition but also in a wider context of democratic representation. When voters delegate their power to parties at elections, they give them a mandate to fulfil their policy programmes from the election campaign (McDonald & Budge, Reference McDonald and Budge2005). However, these programmes contain much more information than policy commitments. Parties also define problems, attack opponents, claim credit for previous policies and use vague signals of future intentions, such as ‘We support this policy’ (Dolezal et al., Reference Dolezal, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Müller, Praprotnik and Winkler2018). While voters can use these parts of the programme to infer a party's visions, commitments are the most explicit signal of what policies a party will implement after an election. Voters can use promises to hold parties accountable because they can punish parties in the following election for not delivering on their policy solutions (Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020). Therefore, the results of this paper also highlight situations under which democratic accountability might be more difficult to uphold for voters. For instance, as discussed above, parties become more reluctant to commit when they are surrounded by several other parties. Voters might, thus, find it more difficult to hold parties accountable in multi‐party than in two‐party systems. This is, broadly speaking, also the overall conclusion of Kam et al. (Reference Kam, Bertelli and Held2020), especially if parties in multi‐party systems are not grouped into two clearly distinct blocs. These authors argue that even if a substantial number of voters withdraw their vote for a party, the consequences for this party might be minimal, at least in terms of government entrance after the election. That parties are both less likely to make commitments and less affected by vote losses illustrates how challenging it is for voters to punish parties in multi‐party systems.

The policy‐committing strategy is an integral part of parties’ political communication, and research on parties, issue competition and policymaking, in general, should take the strategy seriously in future studies. Future research should study how parties’ use of the policy‐committing strategy might conflict with their aspirations to become part of a government after an election. As I have argued theoretically, parties are not only concerned about the immediate vote gains at the coming election when they make commitments. They are also considering how these commitments affect the government formation and policymaking processes after the election. These considerations are important for parties’ chances to fulfil their commitments and for their government aspirations. When a party has locked itself on its position, it is more difficult to make compromises and that might deter other parties from collaborating with the party. The conflict between a party's vote‐seeking (pre‐electoral) and office‐seeking (post‐electoral) motives constitutes a difficult dilemma for political parties, especially in modern politics where the policy‐committing strategy has become increasingly important.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the EJPR editors and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Furthermore, this paper has received valuable feedback from Elin Naurin, Theres Matthieß, Christoffer Green‐Pedersen, Zeynep Somer‐Topcu, Tarik Abou‐Chadi, Valentin Daur, participants at the ECPR General Conference 2022 and members of the Comparative Politics Section at Aarhus University. Daniel Møller Eriksen kindly introduced me to large language models which I benefitted greatly from in this paper. I am also grateful for the work done by the team of human coders (Andreas, Asbjørn, Caroline, Christian, Marie, Mathilde and Tobias). Finally, I wish to extend my deepest gratitude to Carsten Jensen and Helene Helboe Pedersen for their invaluable feedback, insightful questions and constructive suggestions throughout the entire process of developing this paper.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 817855).

Conflicts of interest statements

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The dataset (polcommit_v1.0.csv) is available from the following Harvard Dataverse: ‘Vestergaard, M. B. (2025): PolCommit dataset, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Y7RGS5, Harvard Dataverse’.

The replication do‐file (Stata‐version) can be found on this Harvard Dataverse: ‘Vestergaard, M. B. (2025): Replication Data for: Vestergaard (2025): Why all these promises? How parties strategically use commitments to gain credibility in an increasingly competitive political landscape. European Journal of Political Research, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/CL9WEA, Harvard Dataverse’.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix A: Pledges versus commitments

Appendix B: Bargaining days to form governments

Appendix C: Selection of countries

Appendix D: Included manifestoes

Appendix E: Categorization of issues

Appendix F: Relationship between saliency and commitments

Appendix G: Descriptive statistics

Appendix H: Robustness tests

Appendix I: Length of manifestoes over time

Appendix J: Coding procedure of dependent variable