Assessment of newborn size is a vital component of neonatal care that informs the level of postnatal care required, guides early interventions, and helps to predict future health risks. Birth data at population level is a reliable indicator of the overall health and nutritional status when compared with international standards to inform public health policy.

In 2014, to standardize individual newborn care and facilitate comparisons across the world, the INTERGROWTH-21st Consortium published international newborn size standards for singletons (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Cheikh Ismail, Victora, Ohuma, Bertino, Altman, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Gravett, Purwar, Frederick, Noble, Pang, Barros, Chumlea, Bhutta and Kennedy2014), based on World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations for the evaluation of anthropometric measures (de Onis & Habicht, Reference de Onis and Habicht1996). Using these standards, the estimated prevalence of small vulnerable newborns—born preterm or small for gestational age (SGA)—among 165 million live births in 23 countries from 2000 to 2021 was 11.7%, IQR 9.9−14.2% (Suarez-Idueta et al., Reference Suárez-Idueta, Yargawa, Blencowe, Bradley, Okwaraji, Pingray, Gibbons, Gordon, Warrilow, Paixao, Falcão, Lisonkova, Wen, Mardones, Caulier-Cisterna, Velebil, Jírová, Horváth-Puhó and Sørensen2023).

Whether the same standards should be used to assess the size of newborn twins remains uncertain. Compared to singletons, newborn twins have lower birth weights for gestational age with a distribution shifted to the left (Joseph et al., Reference Joseph, Liu, Demissie, Wen, Platt, Ananth, Dzakpasu, Sauve, Allen and Kramer2003) and different etiological characteristics of the low birth weight; and the pattern of their intrauterine growth differs from 26−28 weeks’ gestation (Ghi et al., Reference Ghi, Prefumo, Fichera, Lanna, Periti, Persico, Viora and Rizzo2017; Grantz et al, Reference Grantz, Grewal, Albert, Wapner, D’Alton, Sciscione, Grobman, Wing, Owen, Newman, Chien, Gore-Langton, Kim, Zhang, Buck Louis and Hediger2016; Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Okby, Freeman, Rosen, Nevo, Barrett and Melamed2020). Consequently, the SGA rate for newborn twins at birth, based on singleton charts, can be as high as 30−50% (Grantz et al., Reference Grantz, Grewal, Albert, Wapner, D’Alton, Sciscione, Grobman, Wing, Owen, Newman, Chien, Gore-Langton, Kim, Zhang, Buck Louis and Hediger2016; Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Barrett, Fox, Rebarber, Kingdom and Melamed2022; Melamed & Hiersch, Reference Melamed and Hiersch2025).

The divergence in fetal growth between twins and singletons has traditionally been explained by the physical constraints imposed by the size of the uterus and the so-called ‘placental crowding hypothesis’, that is, the concept that the uteroplacental unit fails to meet the fetuses’ nutritional requirements late in pregnancy (Bleker et al., Reference Bleker, Wolf and Oosting1995).

It has also been suggested that the slower growth of twin fetuses is ‘a benign physiological adaptation in a predominantly monotocous species when faced with the challenge of multiple gestations’ (Melamed & Hiersch, Reference Melamed and Hiersch2025). The evidence for such a physiological adaptation includes the finding that twins diagnosed as SGA on singleton reference charts are less likely to have abnormal placental histopathology than SGA singletons (Kibel et al., Reference Kibel, Kahn, Sherman, Kingdom, Zaltz, Barrett and Melamed2017). In addition, it has recently been shown that dichorionic twins have proportionally, in some ultrasonographic markers, less fat accumulation than singletons from as early as 15 weeks’ gestation (Gleason et al., Reference Gleason, Lee, Chen, Wagner, He, Grobman, Newman, Sherman, Gore-Langton, Chien, Goncalves and Grantz2025). Whether or not this is an early evolutionary adaptive process or a consequence of risk factors associated with multiple pregnancies (i.e., maternal age, assisted conception, infertility history) remains unclear.

Hence, there are arguments for using twin-specific charts to avoid over-diagnosing SGA at birth and potential clinical harms (Townsend & Khalil, Reference Townsend and Khalil2021). However, the selection of a prescriptive population for the construction of such normative tools is perhaps the most limiting factor, that is, what is a normative twin population considering the multicausality of multiple pregnancies and the associated pathologies?

While the debate about the use of twin-specific charts continues, given that (a) the INTERGROWTH-21st Consortium has collected data to characterize a normative sample matching the singleton standards and (b) there is a clinical demand for such a robust tool, we have decided to offer the size at birth counterpart for twin newborns. Thus, here we present international newborn size normative charts for twins using the same methodological approach adopted to construct the singleton standards.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

A detailed description of the study design, methodology, and strategy for selecting the study populations is available elsewhere (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Altman, Purwar, Noble, Knight, Ruyan, Cheikh Ismail, Barros, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Bertino, Gravett, Bhutta and Kennedy2013). In brief, the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study (NCSS) of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project was a population-based study, conducted between 2009 and 2014, in eight delimited urban centers in three high-income, three middle-income and two low-income countries worldwide: Pelotas, Brazil; Turin, Italy; Muscat, Oman; Oxford, UK; Seattle, USA; Shunyi County, a suburban district of the Beijing municipality, China; Central Nagpur, Maharashtra, India; and the Parklands suburb of Nairobi, Kenya.

The populations were selected in settings in which mothers’ health and nutritional needs were met, adequate antenatal care was offered and there were no major environmental constraints on fetal growth. Participating hospitals covered >80% of all deliveries in their corresponding geographically demarcated areas during the study period. Data were collected from all newborns over 12 consecutive months at each study site, or until the target of >7000 deliveries per site was attained.

Detailed information on maternal social, demographic, environmental and clinical characteristics, as well as pregnancy and delivery outcomes were abstracted from medical records, complemented by information from care providers (if records were incomplete) and by interviewing the mothers using a structured questionnaire. During the study period, all newborns—including those admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), to special care or to another referral-care level—were assessed daily until hospital discharge to document mortality and morbidity.

All body size measures were collected independently in duplicate by two trained anthropometrists. Measures were taken within 12 hours of birth using identical equipment at all sites: an electronic scale (Seca, Hangzhou, China) for birth weight, a specially designed Harpeden infantometer (Chasmors, London, UK) for length, and a metallic nonextendable tape (Chasmors) for head circumference. The equipment, which was calibrated twice a week, was selected for accuracy, precision, and robustness. Measurement procedures were standardized across sites. If any differences between measurements exceeded the set maximum allowable values (birth weight = 50 g, birth length = 7 mm and head circumference = 5 mm), both observers independently obtained a second measurement. The intra- and inter-observer error of measurement values, obtained during the standardization and retraining sessions of the anthropometry staff, were 0.3 to 0.5 cm for recumbent length (Cheikh Ismail et al., Reference Cheikh Ismail, Knight, Ohuma, Hoch and Chumlea2013).

Methods for training, standardization and quality control were uniformly employed across all sites and have been described elsewhere (Cheikh Ismail et al., Reference Cheikh Ismail, Knight, Ohuma, Hoch and Chumlea2013). Neonatal clinical practices, including NICU care and feeding, were also standardized across sites based on a package of minimum evidence-based practices, following an agreed protocol adopted by the INTERGROWTH-21st Neonatal Study Group (Bhutta et al., Reference Bhutta, Giuliani, Haroon, Knight, Albernaz, Batra, Bhat, Bertino, McCormick, Ochieng, Rajan, Ruyan, Cheikh Ismail and Paul2013).

To construct the INTERGROWTH-21st newborn size standards for singletons, we selected an ‘NCSS prescriptive subpopulation’ that consisted of all pregnancies meeting, in addition to the underlying population characteristics, strict individual eligibility criteria for a pregnant population at low risk of impaired fetal growth (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Cheikh Ismail, Victora, Ohuma, Bertino, Altman, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Gravett, Purwar, Frederick, Noble, Pang, Barros, Chumlea, Bhutta and Kennedy2014). Women also had a reliable ultrasound estimate of gestational age using crown-rump length <14 weeks’ gestation or biparietal diameter, the latter if antenatal care started ≥14 weeks and ≤24 weeks’ gestation.

In the present analysis, we have produced international newborn size normative charts for twins using the same conceptual framework and methodology as for singletons, except that we slightly modified the inclusion criteria used for the original study on singleton pregnancies because we also included women: (a) aged >35 and <40; (b) who conceived using assisted reproductive technology (ART); and (c) with a history of previous miscarriages because these are causally associated with twin pregnancies. We performed a sensitivity analysis to ascertain any effect of these variables on twin size at birth.

Data Collection

The data processing and management systems are described in detail elsewhere (Ohuma et al., Reference Ohuma, Hoch, Cosgrove, Knight, Cheikh Ismail, Juodvirsiene, Papageorghiou, Al-Jabri, Domingues, Gilli, Kunnawar, Musee, Roseman, Carter, Wu and Altman2013). In brief, all supporting documentation and data collection forms used in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project were translated into the main local language, tested locally and introduced into the specially developed, electronic data management system. All forms were integrated and linked to reduce duplication in the data collection process and facilitate data quality control mechanisms. During data cleaning, all implausible measures were excluded from the analysis. All data collection forms and manuals of operation are freely available online (www.intergrowth21.org.uk).

Statistical Analysis

Our analytical approach has been described in detail previously (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Cheikh Ismail, Victora, Ohuma, Bertino, Altman, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Gravett, Purwar, Frederick, Noble, Pang, Barros, Chumlea, Bhutta and Kennedy2014). In brief, fractional polynomials (Royston & Altman, Reference Royston and Altman1994), LMS (Cole, Reference Cole1988, Reference Cole1989; Cole & Green, Reference Cole and Green1992), LMST (Rigby & Stasinopoulos, Reference Rigby and Stasinopoulos2006) and LMSP (Rigby & Stasinopoulos, Reference Rigby and Stasinopoulos2004) methods assuming a skewed t distribution were used to estimate the fitted centiles. Although fractional polynomials provided satisfactory estimates compared to the other three methods, here we applied all approaches given that our twins sample is smaller and could have different characteristics to the singletons.

As before, we employed the Generalized Additive Models for Location, Scale and Shape (GAMLSS) framework (Rigby & Stasinopoulos, Reference Rigby and Stasinopoulos2005, Reference Rigby and Stasinopoulos2007), which provides the option of fitting various distributions other than the normal (skewed and kurtotic distributions) and modeling other parameters of a distribution that determine scale and shape using fractional polynomials. Furthermore, we evaluated three smoothing techniques: fractional polynomials (Royston & Altman, Reference Royston and Altman1994), cubic splines (Green and Silverman, Reference Green and Silverman1994) and penalized splines (Eilers & Marx, Reference Eilers and Marx1996).

Goodness-of-fit was assessed by four methods: visual inspection of the overall fit of the model using residual quantile-quantile graphs; Worm plot (van Buuren & Fredriks, Reference van Buuren and Fredriks2001); Q statistic (Royston & Wright, Reference Royston and Wright2000) for a particular gestational age range; plots of residual versus fitted values and the distribution of fitted z scores across gestational ages.

Data Availability

Anonymized data will be made available upon reasonable request for academic use and within the limitations of the informed consent. Requests must be made to the corresponding author. Every request will be reviewed by the INTERGROWTH-21st Consortium Executive Committee. After approval the researcher will need to sign a data access agreement with the INTERBIO-21st Consortium.

Results

Of the 59,137 deliveries included in NCSS between May 2009 and August 2013, 1034 (1.7%) were multiple pregnancies (Figure 1). Among those deliveries, we excluded higher order multiple pregnancies (n = 32, 3.1%) and pregnancies with an unreliable estimate of gestational age (n = 122, 11.8%), as well as mothers aged < 18 or > 40 years (n = 61, 5.9%), with a body mass index (kg/m2) > 35 or < 18.5 (124; 12,5%), who smoked or used alcohol or drugs (n = 36; 3.5%), and had pregnancy complications (n = 142, 13.7%) i.e. diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia. We also excluded infants with a congenital malformation (n = 26, 2.5%, excluding only the newborn with a malformation and not the twin if healthy), those born <30 or > 40 weeks’ gestation (n = 30, 2.9%) and those with a birth-weight discrepancy > 25% that was found in literature to be associated with higher risk (n = 114, 11.0%), leaving a final sample of 864 twin newborns.

Figure 1. Flow chart.

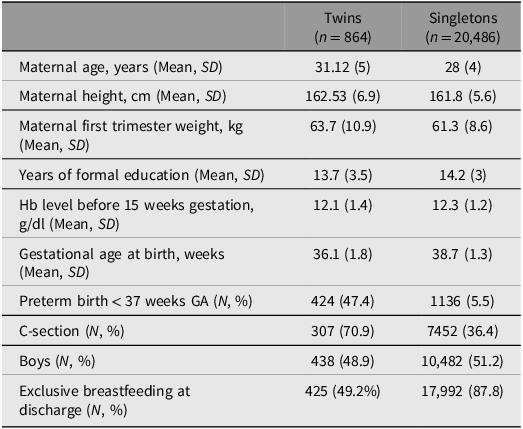

Table 1 shows the baseline maternal and neonatal characteristics of the twin sample and, for comparison, those for the pregnancies in NCSS, which contributed to the newborn size standards for singletons (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Cheikh Ismail, Victora, Ohuma, Bertino, Altman, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Gravett, Purwar, Frederick, Noble, Pang, Barros, Chumlea, Bhutta and Kennedy2014). The marked differences between the twin and singleton datasets were the rates of cesarean section (70.9% vs. 36.4%), preterm birth (47.4% vs. 5.5%) and exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge (49.2% vs. 87.8%).

Table 1. Population baseline characteristics for twin and singleton NCSS21 population. All values are mean (SD) for continuous variables and absolute numbers (percentage) for categorical variables

Note: NCSS21, Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project.

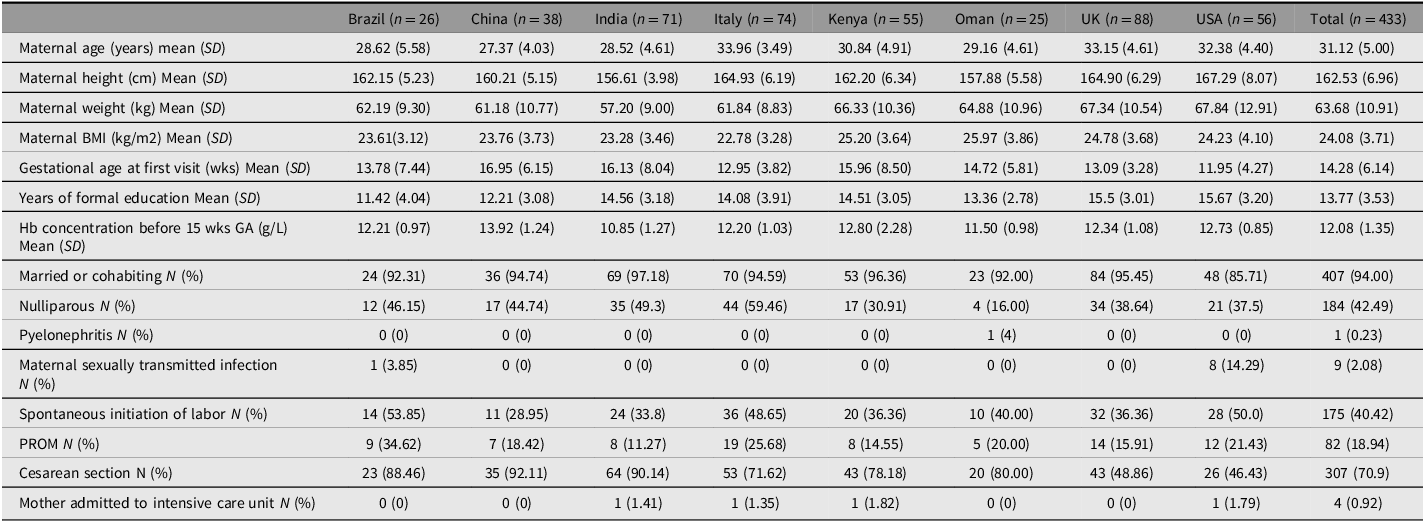

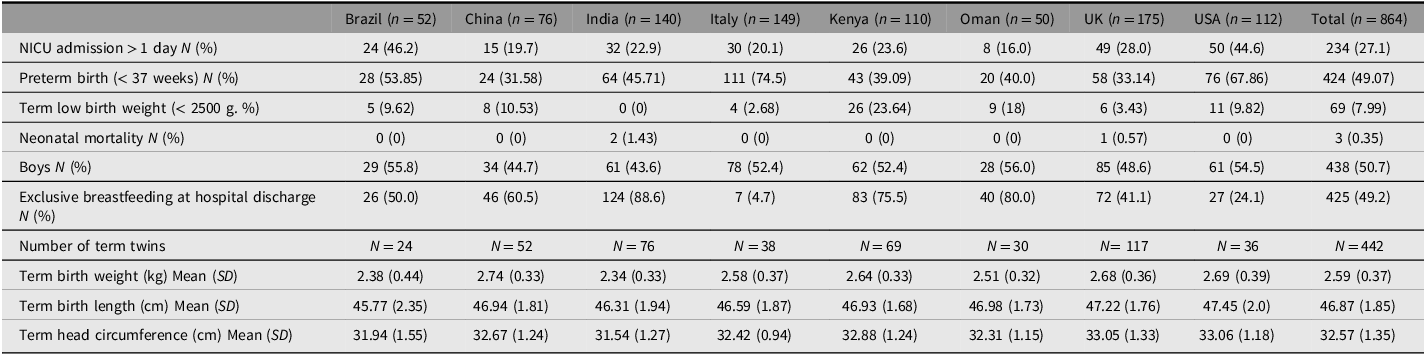

Tables 2 and 3 show maternal and neonatal baseline characteristics and perinatal events by study site. The rates of cesarean section were highest in Beijing (92.1%) and Nagpur 90.1%) and lowest in Oxford (48.9%) and Seattle (46.4%). The preterm birth rates were highest in Turin (74.5%) and Seattle (67.9%) and lowest in Beijing (31.6%) and Oxford (33.1%). Although NICU admission rates for >1 day varied from 16% (Muscat) to 46.2% (Pelotas), overall neonatal mortality was very low (0.4%).

Table 2. Maternal baseline characteristics, by country

Note: PROM, prelabor rupture of membranes.

Table 3. Neonatal baseline characteristics and perinatal events, by country

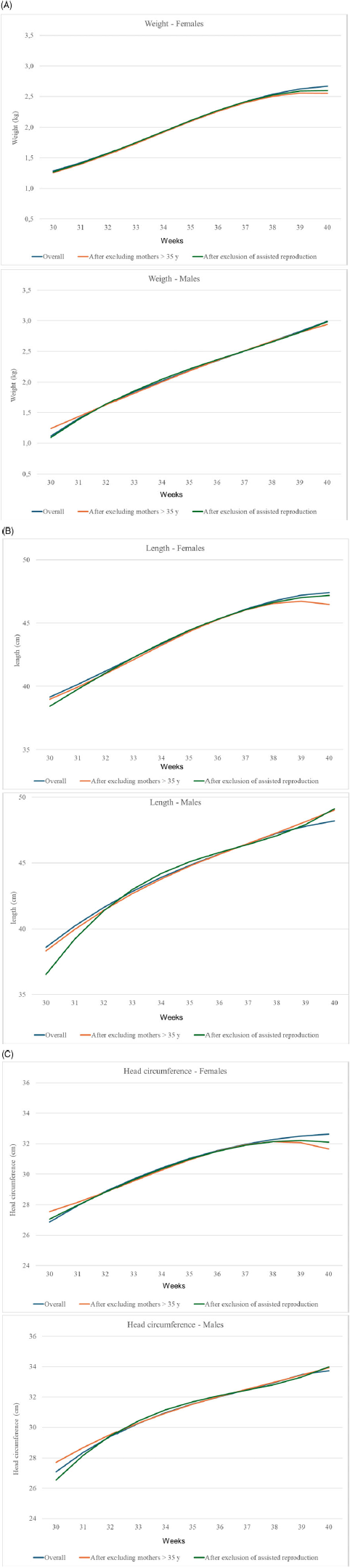

Figure 2 shows the sensitivity analyses for birth weight (A), length (B) and head circumference (C) for boys and girls separately after excluding maternal age > 35 years, previous miscarriages and conception due to ART in our sample; neither maternal age, previous miscarriages nor ART had any major effect on the pooled centiles.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analyses for maternal age > 35 years and assisted reproduction techniques for birth weight (A), birth length (B) and head circumference (C) for females and male.

Figure 3 shows the scatter plots of the birth weight (A), length (B), and head circumference (C) of each individual female twin, and compares the 50th centiles of the singleton and twin charts. Interestingly, most of the twin population falls below the 50th centile of the singletons. There is also an increasing divergence between the 50th centiles as gestational age increases towards term for all three measures, but mainly for weight. The same pattern can be observed in boys (data not shown).

Figure 3. Comparison between the 50th centile of singleton (black) and twin (red) standards of females, for weight (A), length (B) and head circumference (C), for females, with twin measurements scatter plot superimposed.

Figure 4A-4F shows the 3rd, 10th, 50th, 90th and 97th smoothed centile curves from 30 to 40 weeks’ gestation for weight (A), length (B) and head circumference (C) according to gestational age and sex, which represent the international normative charts for newborn twins.

Figure 4 A. International newborn twin size standards for weight for girls.

Figure 4 B. International newborn twin size standards for weight for boys.

Figure 4 C. International newborn twin size standards for length for girls.

Figure 4 D. International newborn twin size standards for length for boys.

Figure 4 E. International newborn twin size standards for head circumference for girls.

Figure 4 F. International newborn twin size standards for head circumference for boys.

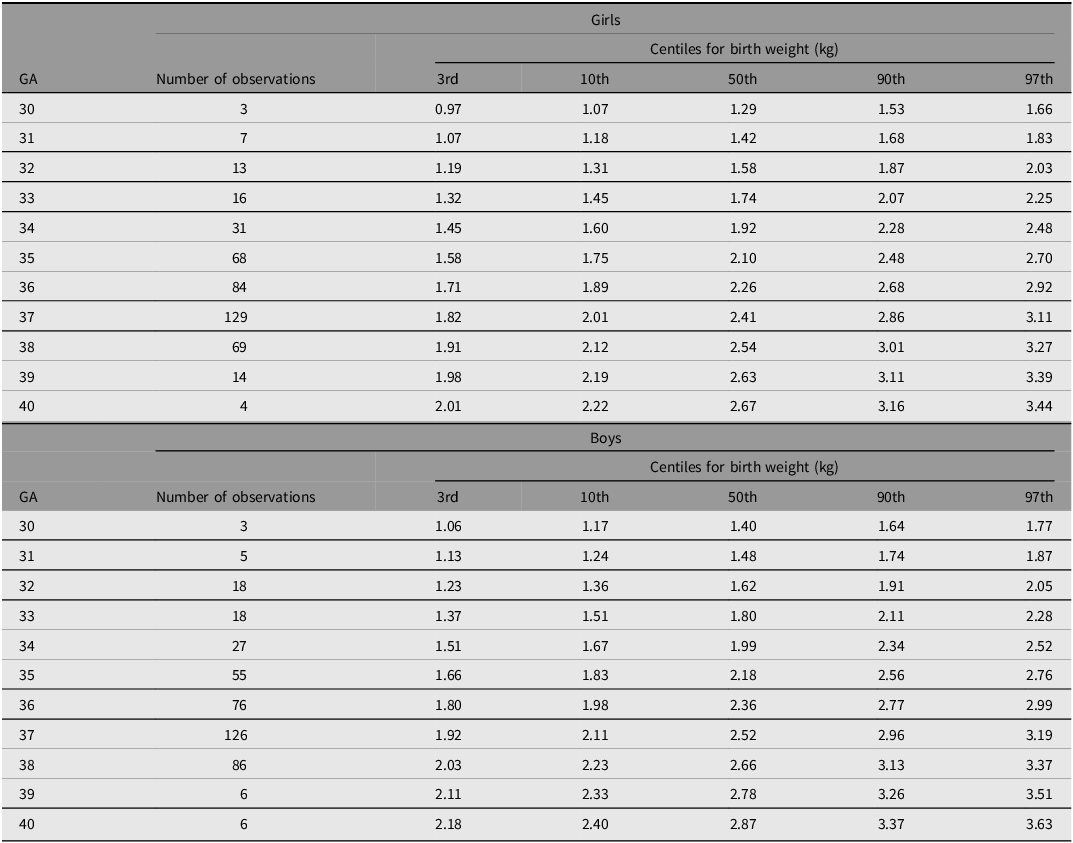

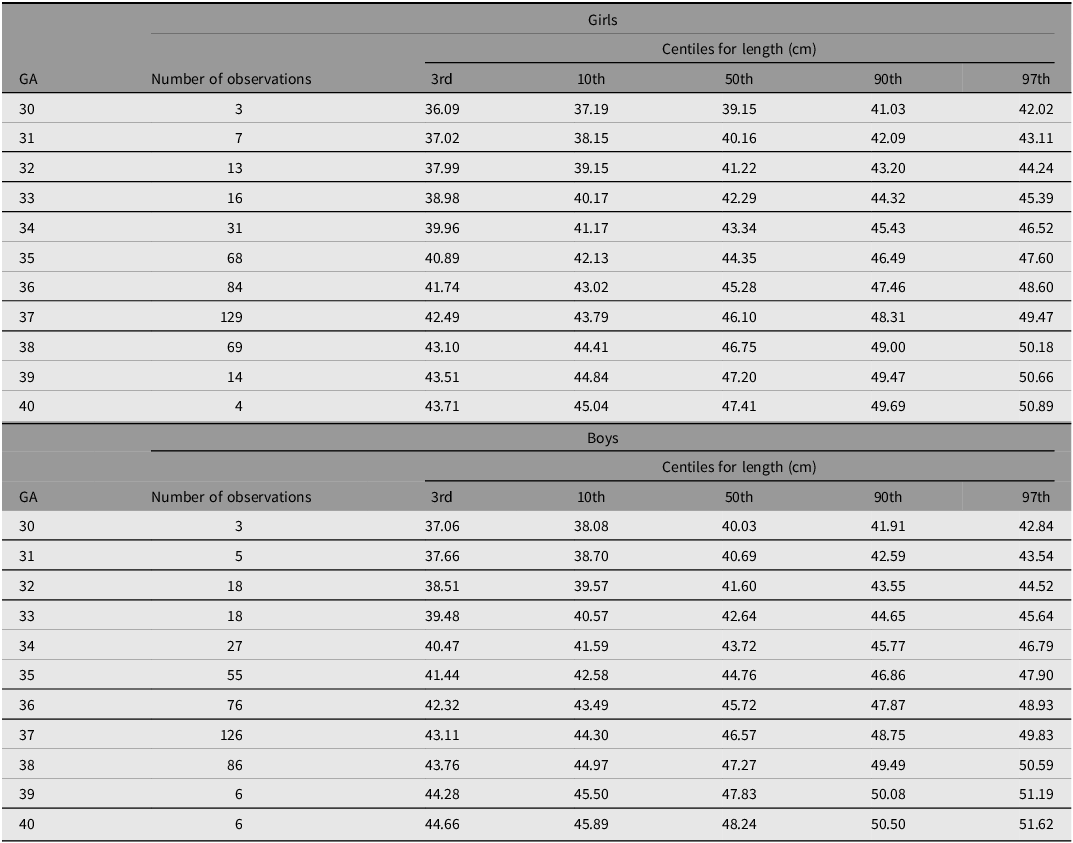

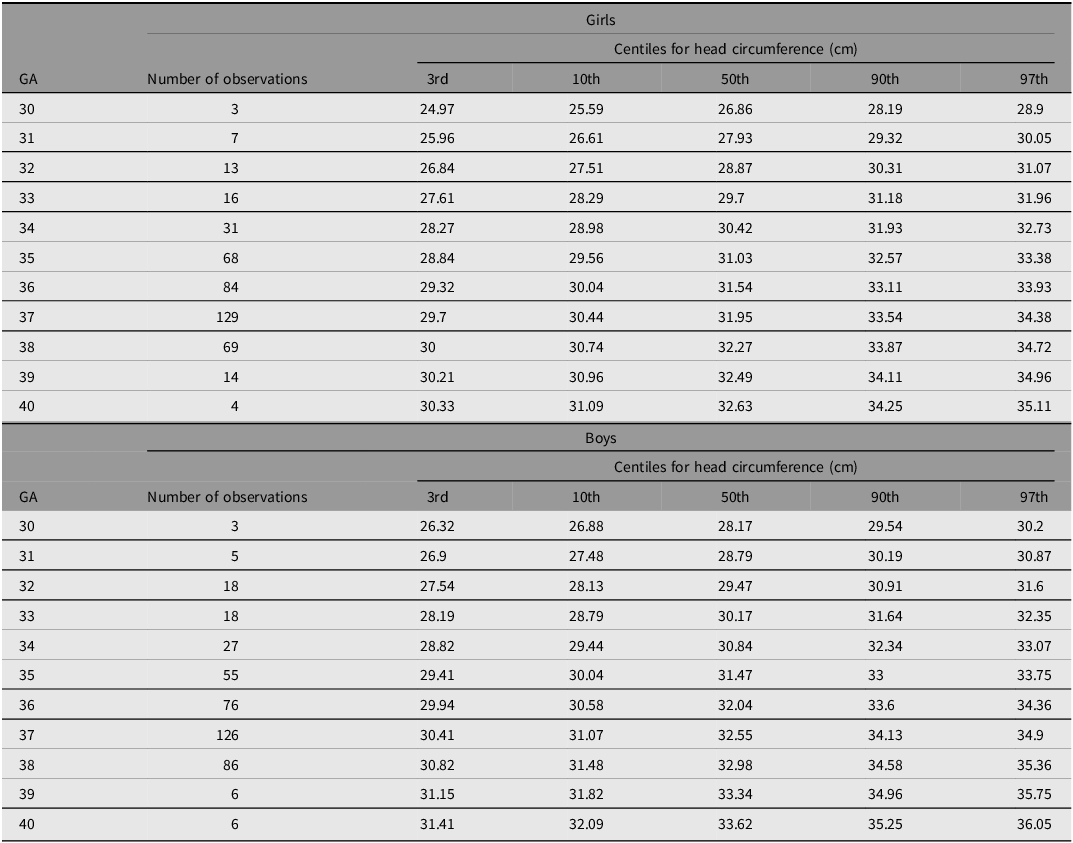

Tables 4−6 show the smoothed 3rd, 10th, 50th, 90th and 97th centiles for twin boys and girls for birth weight (kg), length (cm) and head circumference (cm) according to gestational age. Overall, boys were heavier and longer, and had larger head circumferences than girls.

Table 4. Smoothed centiles for birthweight, of girls and boys, according to gestational age

Note: GA, gestational age.

Table 5. Smoothed centiles for birth length, of girls and boys, according to gestational age

Note: GA, gestational age.

Table 6. Smoothed centiles fors head circumference, of girls and boys, according to gestational age

Note: GA, gestational age.

Discussion

To our knowledge these are the first international, multi-ethnic, sex-specific, anthropometric normative charts for assessing the size of newborn twins, mirroring the methodological approach used to produce the INTERGROWTH-21st newborn size standards for singletons (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Cheikh Ismail, Victora, Ohuma, Bertino, Altman, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Gravett, Purwar, Frederick, Noble, Pang, Barros, Chumlea, Bhutta and Kennedy2014).

These twin-specific normative charts meet the WHO recommendations as compared to our systematic review of the methodological quality of studies designed to create twin-specific newborn charts (Giuliani et al., Reference Giuliani, Ohuma, Spada, Bertino, Al Dhaheri, Altman, Conde-Agudelo, Kennedy, Villar and Cheikh Ismail2015), which did not identify any studies that did so. Among the included studies, most had methodological flaws, such as unreliable gestational age assessment, lack of head circumference and length measures, single center recruitment, and lack of a preplanned design or unclear statistical methodology, thus making comparisons difficult across different populations.

Beyond the variables shared with singleton pregnancies, there are specific factors affecting twin fetal growth that can challenge the prescriptive concept: (a) pathological (i.e., selective FGR in monochorionic twins with unequal placental sharing or twin-to-twin transfusion) or (b) an adaptation secondary to a demand–driven constraint, whose mechanisms are still not completely understood. This explains why various groups, such as the UK Southwest Thames Obstetric Research Collaborative (STORK), have produced twin-specific fetal growth charts that enable the causes for the disproportionately high SGA rate found when using singleton charts to be explored (Kalafat et al., Reference Kalafat, Sebghati, Thilaganathan and Khalil2019; Kalafat & Khalil, Reference Kalafat and Khalil2022).

Predictably, birth-weight thresholds related to neonatal morbidity and mortality differ between singletons and twins, being lower for the latter (Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Barrett, Fox, Rebarber, Kingdom and Melamed2022). In addition, many studies have shown that even if the proportion of twins identified as SGA on singleton charts is much higher than that for singletons, the association between SGA and adverse neonatal outcomes is only apparent when SGA is diagnosed using twin-specific charts (Briffa et al., Reference Briffa, Di Fabrizio, Kalafat, Giorgione, Bhate, Huddy, Richards, Shetty and Khalil2022; Mendez-Figueroa et al., Reference Mendez-Figueroa, Truong, Pedroza and Chauhan2018; Nowacka et al., Reference Nowacka, Kosińska-Kaczyńska, Krajewski, Saletra-Bielińska, Walasik and Szymusik2021; Shea et al., Reference Shea, Likins, Boan, Newman and Finneran2021).

Furthermore, Joseph et al. (Reference Joseph, Fahey, Platt, Liston, Lee, Sauve, Liu, Allen and Kramer2009), instead of using a fixed centile cut-off across gestational ages as a measure of impaired fetal growth, estimated the risk for adverse neonatal outcomes in relation to absolute birth weight as a continuous variable at each gestational week that was associated with the lowest risk. They found that the threshold was lower in twins than in singletons across all gestational ages, supporting the hypothesis that an important component of size difference between twins and singletons is benign, that is, the smaller size of twins compared to singletons is not necessarily predictive of pathology.

The observed centile differences between the NCSS twins and singletons in our dataset are also supportive of the hypothesis.

Our study is uniquely positioned to provide such normative data because: (1) by selecting an ‘NCSS prescriptive subpopulation’ of twins, we have adhered as strongly as possible to the WHO recommendations for constructing international anthropometric standards (de Onis & Habicht, Reference de Onis and Habicht1996). Hence, the included pregnancies were selected on the basis of their social, economic, health and nutritional status, creating a low-risk environment for fetal growth impairment. Indeed, the baseline characteristics of the twin population were similar to the sample used to produce the INTERGROWTH-21st newborn size standards for singletons (Villar et al., Reference Villar, Cheikh Ismail, Victora, Ohuma, Bertino, Altman, Lambert, Papageorghiou, Carvalho, Jaffer, Gravett, Purwar, Frederick, Noble, Pang, Barros, Chumlea, Bhutta and Kennedy2014), except for maternal age (although the difference was not statistically significant), and the cesarean section and preterm birth rates which were, as expected, significantly higher in twins; (2) We did not exclude twins conceived through ART as they represent such a high proportion of the total twin population, especially in high-income countries, although they are most likely different in terms of ‘prescriptiveness’ (Marleen et al., Reference Marleen, Kodithuwakku, Nandasena, Mohideen, Allotey, Fernández-García, Gaetano-Gil, Ruiz-Calvo, Aquilina, Khalil, Bhide, Zamora and Thangaratinam2024). Reassuringly, the sensitivity analysis showed that excluding them did not change the pooled extreme centiles, which supports the clinical applicability of the standards.

However, we had relatively few twins (15.6%) born < 34 weeks’ gestation, although ample numbers were available at more advanced gestational ages that are arguably more relevant clinically. On the other hand, aiming to create normative standards for the more critical infants, that is, those with gestational age below 30 weeks age, would be questionable. We also lacked information regarding chorionicity; however, small differences are reported between the growth of mono- and dichorionic twin fetuses that are probably not relevant clinically, making reasonable the use of the same chart for both types of pregnancy (Hiersch et al., Reference Hiersch, Barrett, Fox, Rebarber, Kingdom and Melamed2022). Moreover, in a recent systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis, the risks of adverse perinatal outcomes for both monochorionic and dichorionic twins appeared similar when one or both twins were SGA (Koch et al., Reference Koch, Burger, Schuit, Mateus, Goya, Carreras, Biancolin, Barzilay, Soliman, Cooper, Metcalfe, Lodha, Fichera, Stagnati, Kawamura, Rustico, Lanna, Munim, Russo, Nassar and Li2022).

In summary, we have produced international, sex-specific, smoothed normative centiles for weight, length, and head circumference for gestational age at birth for twin newborns, starting from 30 weeks’ gestation, thereby extending the INTERGROWTH-21st clinical tools to the twin population. It is now incumbent upon research teams and specialized societies to continue this work by conducting validation studies, selecting the most appropriate clinically relevant cut-off points (as opposed to statistically selected centiles; e.g., 3rd or 10th) to determine which twin newborns are most at risk of adverse postnatal outcomes.

Acknowledgments

INTERGROWTH The study was supported by a grant (49038) from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the University of Oxford. We thank the Health Authorities in Pelotas, Brazil; Beijing, China; Nagpur, India; Turin, Italy; Nairobi, Kenya; Muscat, Oman; Oxford, UK; and Seattle, WA, USA, who helped with the project by allowing participation of these study sites as collaborating centers. We thank Philips Healthcare for providing the ultrasound equipment and technical assistance throughout the project and MedSciNet UK for setting up the INTERGROWTH-21st website and for the development, maintenance, and support of the online data management system. We also thank the parents and infants who participated in the studies and the more than 200 members of the research teams who made the implementation of this project possible.

The participating hospitals included: Brazil, Pelotas (Hospital Miguel Piltcher, Hospital São Francisco de Paula, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Pelotas, and Hospital Escola da Universidade Federal de Pelotas); China, Beijing (Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Shunyi Maternal and Child Health Centre, and Shunyi General Hospital); India, Nagpur (Ketkar Hospital, Avanti Institute of Cardiology, Avantika Hospital, Gurukrupa Maternity Hospital, Mulik Hospital and Research Centre, Nandlok Hospital, Om Women’s Hospital, Renuka Hospital and Maternity Home, Saboo Hospital, Brajmonhan Taori Memorial Hospital, and Somani Nursing Home); Kenya, Nairobi (Aga Khan University Hospital, MP Shah Hospital, and Avenue Hospital); Italy, Turin (Ospedale Infantile Regina Margherita Sant’ Anna and Azienda Ospedaliera Ordine Mauriziano); Oman, Muscat (Khoula Hospital, Royal Hospital, Wattayah Obstetrics and Gynaecology Poly Clinic, Wattayah Health Centre, Ruwi Health Centre, Al-Ghoubra Health Centre, and Al-Khuwair Health Centre); UK, Oxford (John Radcliffe Hospital) and USA, Seattle (University of Washington Hospital, Swedish Hospital, and Providence Everett Hospital). Full acknowledgment of all those who contributed to the development of 21st Project are online and in the Appendix.

Ethics

The INTERGROWTH-21st Project was approved by the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee ‘C’ (reference 08/H0606/139), the research ethics committees of the individual participating institutions, and the corresponding regional or national health authorities where the project was done. We obtained institutional consent to use routinely collected data and women gave oral consent for the use of those data.

Declaration of interests

ATP is supported by the Oxford Partnership Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre with funding from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) funding scheme. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR the Department of Health or any of the other funders. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Role of the funding source

The sponsors had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributors statement

FG, SD, and GM verified the full data for the paper, all authors have full access to the data and accept responsibility for publication