Introduction

Field theories broadly refer to a set of related sociological frameworks that prioritize a relational and meso-level understanding of social action in particular social arenas (Kluttz & Fligstein Reference Kluttz, Fligstein and Abrutyn2016). Among these, strategic action field theory (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012)—which attempts to synthetize the core elements of Bourdieusian field theory and New Institutionalism—offers a powerful lens to explore the relationships of conflict and cooperation that exist among actors in meso-level social orders. In a nutshell, a strategic action field (SAF) can be understood as:

A constructed mesolevel social order in which actors (who can be individual or collective) are attuned to and interact with one another on the basis of shared (which is not to say consensual) understandings about the purposes of the field, relationships to others in the field (including who has power and why), and the rules governing legitimate action in the field (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012, p. 9).

SAF theory represents a systematic and comprehensive attempt to make sense of the relationships of conflict and cooperation, of reproduction and change, that characterize several meso-level social orders in which individual or collective actors interact, ally, compete and vie for advantage. Like other field theories, strategic action field (SAF) theory has proved a useful theoretical instrument for analysing several arenas, including the non-profit sector (Barman, Reference Barman2016). For instance, it has been notably effective in examining the re-emergence of collaborative projects in the housing field (Lang & Mullins, Reference Lang and Mullins2020), the emergence of a nascent field composed of organizations addressing issues related to sex work and trafficking (Anasti, Reference Anasti2020), and the encroachment process that underlies the rise of the social entrepreneurship field (Spicer et al., Reference Spicer, Kay and Ganz2019).

However, unlike earlier field approaches, there has been little systematic effort to apply social network analysis (SNA) in combination with SAF theory, possibly due to the apparently dismissive position of its proponents (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 30, 187). We contend that SNA, especially when combined with qualitative data, lets us visualize and examine field positions and position-takings, and more broadly understand how material and symbolic forms of power are distributed in, and affect, the social order under investigation (e.g. Serino et al., Reference Serino, D’Ambrosio and Ragozini2017). Hence, the encounter between SAF theory and SNA tools can enable researchers to gain a more comprehensive understanding of meso-level social orders, uncovering hidden patterns and connections that may not be apparent through other methods, thus enhancing the methodological rigour of their research.

The main purpose of this article is to illustrate the benefits of coupling qualitative and network data to examine in greater detail the hidden mechanics of a field and to test and refine findings obtained from qualitative data. To do so, this paper builds on a study of the charitable food provision field in Greater Manchester (UK), showing how network-analytic formalizations of seemingly unimportant digital connections, such as Twitter ‘follows’, can provide meaningful insights into the functioning of SAFs. Through this analytical exercise, we highlight some specific strengths of SAF theory that make its network formalization especially fitting. Furthermore, we illustrate a cost-effective and time-efficient way to obtain one informative type of network data on civil society organizations using readily available digital traces from social media.

Besides its core methodological objective, the innovative analyses carried out in this paper also help us advance our understanding of food poverty and food aid by using network data to provide further support to the claim that the charitable food provision (CFP) sector should better be understood as a field where different interests are at stake (Oncini, Reference Oncini2022a; Reference Oncini2023). Over recent decades, the number and salience of food charities have increased in higher-income countries all over the world (Lambie-Mumford & Silvasti, Reference Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti2020). Especially in the UK, where the rise and institutionalization of food aid has been more marked, scholars have investigated in depth the causes and consequences of the emergence of food banks (e.g. Garthwaite, Reference Garthwaite2016; Loopstra et al., Reference Loopstra, Fledderjohann, Reeves and Stuckler2018), but neglected the heterogeneity and relational dimension of the sector, and how it is embedded more widely and interlinked with other institutions.

In this paper, we first investigate the link between SAF theory, SNA and qualitative methods, focusing on their utility in analysing a SAF. Hence, we illustrate the findings from a preceding qualitative study in Greater Manchester, interpreting the CFP sector as a SAF. We then present the strategy employed to collect data on food charities’ digital connections, the network-analytic hypotheses built from the qualitative data and the findings obtained using whole-network measures, positional analyses and group density analyses. Finally, we discuss the strengths and limitations of the approach and outline how researchers could use Twitter data in different phases of field investigations.

Strategic Action Fields and Social Network Analysis: Like Oil and Water?

The idea of bridging field theory with SNA is certainly not new. While from inception New Institutionalism explicitly referred to network data—and particularly blockmodelling—as possible tools to collect information on and study fields (DiMaggio, Reference DiMaggio1986; DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983), Bourdieu rejected SNA and advocated correspondence analysis since the technique resembles his relational approach (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992; Lebaron, Reference Lebaron2009). In his view, the focus on manifest interactions that lies at the basis of SNA would prevent the analyst from grasping the objective, latent relations that fundamentally structure society. SNA would mistake consequences for causes and neglect the role of history in determining principles of classification used by actors to evaluate themselves and others (de Nooy, Reference De Nooy2003). In other words, it would prevent the sociologist from achieving the epistemological break from common sense that is necessary to unveil the power relationships that structure a field (Singh, Reference Singh2019). Despite such reluctance, his argument has been criticized on both methodological and theoretical grounds (Bottero & Crossley, Reference Bottero and Crossley2011; de Nooy, Reference De Nooy2003), and SNA has been fruitfully used in conjunction with Bourdieu’s positional approach (e.g. Serino et al., Reference Serino, D’Ambrosio and Ragozini2017).

Since SAF draws heavily from both New Institutionalism and Bourdieu’s field theory (Barman, Reference Barman2016), it is not surprising that Fligstein and McAdam dedicate some space in A Theory of Fields to discussing SNA. In two distinct passages, the authors argue that SNA can be a powerful ancillary tool in the study of strategic action fields, but they do not explain further how the theory and the technique could be put into dialogue:

Network analysis has the potential to be a powerful aid to the study of strategic action fields but only when informed by some broader theory of field dynamics. A structural mapping of field relations, however sophisticated, will never substitute for a deeper analysis into the shared (or contested) understandings that inform and necessarily shape strategic action within a strategic action field. (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 30)

And again:

One of the frustrating aspects of such [network-analytic] studies is that they often assume that the technique is isomorphic to the field. That is, the technique in and of itself defines the field. We argue that one needs to have a conceptual understanding of the field before one can apply such techniques. One way to understand this critique is to suggest that there is a lack of linkage between the theoretical arguments one might make about a particular field and the technique one uses to generate a quantitative analysis of that field. (Ibid.: 187)

While sympathetic to this view, we believe that the argument could be unpacked further to discuss the potential ways through which SNA can help us better understand strategic action fields dynamics. We agree that, as any other statistical technique, SNA cannot speak on its own and often remains silent about the symbolic fabric and the motivations behind relationships of cooperation and competition within a field. As the chisel does not carve without a sculptor, statistical procedures do not hint at the meanings hiding beneath data associations without the analyst. This is the reason why qualitative data—interviews, participant observation, document and archival analysis—are necessary, and potentially sufficient, to comprehend how a field works. At the same time, there are at least three ways through which SNA can improve our understanding of any strategic action field. First, it permits to confirm the basic premise underpinning the existence of a field, namely that actors are aware of each other’s existence and actions, and provide guiding with the cumbersome task of delimiting the field’s boundaries. Second, it allows to explore the field’s internal heterogeneity by identifying distinct clusters and structural positions, to verify the correspondence between qualitative and SNA findings, and to further investigate potential discrepancies. Third, it lets us consider the relationships of (inter)dependency between a large number of field actors (typically many more than what qualitative fieldwork methods allows to consider) and its surrounding.

This view resonates with the emerging body of literature arguing that mixed-methods approaches to SNA are optimal for identifying patterns of connection and network dynamics, and elucidating the mechanisms behind those patterns (e.g. Bellotti, Reference Bellotti2015). As Crossley and Edwards (Reference Crossley and Edwards2016: 5.5) explain:

Quantitative techniques of SNA are crucial for identifying and measuring the properties of networks and for identifying associations between such properties and wider behaviours and factors that might be regarded either as causes or effects of them but we believe that qualitative work is often essential if we are to understand the how and why of such associations.

The combination of qualitative and quantitative tools lets us simultaneously keep the worlds of meaning, conventions and narratives that structure the field together with the formal study of network configurations that can bring to light less obvious patterns of ties and/or emergent clusters of actors. Evidently, this corresponds with SAF’s roots in Bourdieu’s field theory, symbolic interactionism and New Institutionalism.

Hence, SAF and SNA have some affinities that are worth exploiting. Like other field theories, SAF looks at a meso-level social order made up of actors who ‘are attuned to and that interact with one another’ (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 10). Accordingly, we believe it must be always possible to formalize the field structure as a social network. While agreeing that networks per se are not fields, nor provide a definitive portrait of all relevant field dynamics, we contend that reconstructing and analysing the manifest social network structure of an SAF will always yield analytical benefits.

Charitable Food Provision as a Strategic Action Field

This section summarizes the empirical study we use to illustrate our proposed methodological approach: the charitable food provision field in the Greater Manchester area. As it has been recently argued elsewhere (Oncini, Reference Oncini2022a; Reference Oncini2023), the application of SAF theory (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012) provides much analytical leverage for understanding food charities’ perspectives, practices and relationships. In recent decades, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, rising poverty levels and financial precarity have led to the emergence and consolidation of charitable food provision in the UK, where providing food aid has become an integral part of the assistance landscape, with thousands of charities donating food parcels and meals to millions of people in poverty (Loopstra et al., Reference Loopstra, Fledderjohann, Reeves and Stuckler2018). The COVID-19 crisis further exacerbated this, with major organizations reporting unprecedented levels of demand (Boons et al., Reference Boons2020; Oncini, Reference Oncini2021; Reference Oncini2022b; Hirth et al., Reference Hirth, Oncini, Boons and Doherty2022).

While food banks have become the prototype ‘food charity’, the whole food assistance sector has in fact expanded. Next to famous food bank networks (e.g. Trussell Trust) organizations such as community kitchens, independent food banks, soup vans and pantries also provide food aid to people (Lambie-Mumford & Silvasti, Reference Lambie-Mumford and Silvasti2020). Concurrently, given the rising attention given to the environmental impact of food waste, many food sector businesses have reorganized to distribute surplus food. This has become a crucial supply channel for many food charities and further cemented the centrality of the CFP sector in British society (Caplan, Reference Caplan2017).

Our study focuses on a particular urban region in the UK: Greater Manchester. Given its high levels of food insecurity and the presence of a wide range of food charities (GMPA, 2020, 2021), Greater Manchester could be considered as a typical case (Gerring, Reference Gerring2007) for Britain. Furthermore, as previously argued by the first author (Oncini, Reference Oncini2022a; Reference Oncini2023), many theorized traits of SAFs can be observed in the everyday functioning of CFP in the region. Drawing upon self-collected qualitative data, the author highlighted four main points for discussion that could subsequently be used in follow-up network analysis:

A. Although multiple models of food support are present (see B) an overarching SAF is in place, as all types of food charities share a basic understanding of the field’s main purpose (providing relief from food poverty) and they take each other into account in their decision-making processes (including whether to cooperate or compete with other field members).

B. Although part of the same, superordinate SAF, different models of food provision and support operate within it, namely Trussell Trust food banks, independent food banks, warm-meal providers, food pantries and hybrid charities. They present their own internal logics and understandings of legitimate action. The first two providers are the best known: service users are given a parcel containing food to take home, prepare and eat. However, some years ago the Independent Food Aid Network (IFAN) started to challenge the Trussell Trust model and to represent independent food banks that did not become part of a more formal affiliation-based model. Concurrently, food pantries challenged the food bank model tout court: they give access to groceries, usually every week, for payment of a small subscription, arguing that this is a more respectable way to counter poverty. Finally, meal providers distribute cooked meals or operate free-access canteens, and a few hybrids of these four models exist.

C. As in any organized social space, the broader CFP field in Greater Manchester contains a hierarchy in which some actors wield considerably more influence and power than others. In this field, food banks affiliated with the Trussell Trust are generally perceived as incumbents both by other CFPs and relevant stakeholders. On the other hand, two types of subaltern actors can be distinguished: while independent food banks (some of them formally united around IFAN) and food pantries could be described as challengers of the status quo, a significant number of organizations, mostly warm-meal providers, are less engaged in struggles for legitimacy but still influenced by the field's internal dynamics, and thus would be better characterized as sideliners.

D. The activities of food charities are conditioned not only by other actors within local CFP but also by actors from a wider environment. In particular, five categories of external actors involved in proximate fields were identified as particularly relevant, imposing different constraints on and opportunities to CFP: (i) national state agencies and bodies, (ii) local authorities, (iii) private funding institutions, (iv) food surplus distributors and (v) academic researchers (see Table 1). While food charities seem to have a relationship of dependence on national authorities, funding institutions and food surplus distributors (unbalanced), the relationship with local authorities and academic researchers appears more horizontal, driven by interdependence.

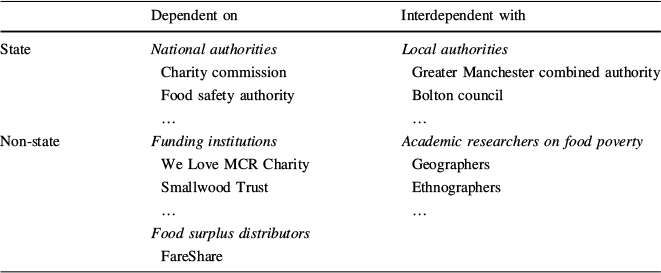

Table 1 Broader field environment: main fields of interest (in italics) and examples of actors (indented)

Dependent on |

Interdependent with |

|

|---|---|---|

State |

National authorities Charity commission Food safety authority … |

Local authorities Greater Manchester combined authority Bolton council … |

Non-state |

Funding institutions We Love MCR Charity Smallwood Trust … Food surplus distributors FareShare |

Academic researchers on food poverty Geographers Ethnographers … |

See full list in Table A.II of online Appendix.

While undoubtedly rich and insightful, is it possible to further test the accuracy of these conclusions? In other words, how can we know that the qualitative evidence provides a good description of what really goes on within the CFP field? After all, the evidence is limited (many food charities were not part of the sample) and, more importantly, the characteristics of a meso-level social order were not directly observed at that analytical level, but were mostly inferred through the aggregated assessment of discrete organizational responses and documents. While gathering actors’ own accounts of their activities and perceptions of their surroundings is tremendously informative, analysts should be aware of its inherent limitations. Social actors often fail to gain a view of the whole social structure in which they operate, being limited by what they observe in their immediate environment, that is, from other actors with whom they directly interact. This is where triangulation with social network data might prove particularly beneficial.

Empirical Strategy

Data: Public Connections on Twitter

If analysts decide to enrich their analysis of a strategic action field with SNA, an important practical question quickly comes to mind: what kind of social network should be reconstructed and submitted to analysis? While the range of possible relations that can be considered is almost infinite—‘limited only by a researcher’s imagination’ (Brass et al. Reference Brass, Galaskiewicz, Greve and Tsai2004: 795)—, quality network data on many relationships of interest can be extremely hard to gather. In the context of the ever-increasing digitalization of social life, researchers often resort to ‘trace data on online behaviours’ (Adams & Lubbers, Reference Adams and Lubbers2023) and use the resulting social networks to analyses as the empirical object. This was precisely the path we followed in this article.

In this article, we aimed to validate and expand our qualitative findings about the functioning of the CFP strategic action field by collecting systematic data on interorganizational digital connections on Twitter.Footnote 1 The choice to focus on this social media platform was driven by two key practical considerations: the accessibility of the data and the broad presence of local and national food charities, which ensured a broad coverage of the organizational population. To ensure comprehensive coverage and expand the network boundary well beyond the dozens of food charities already known to the first author, two additional strategies were followed in order to identify additional Twitter accounts.Footnote 2 Ultimately, we identified 130 Twitter accounts of charitable food providers active in Greater Manchester (see Table A.I in online Appendix).

Among the several types of digital activity between these Twitter accounts that could be examined (e.g. tweets, retweets, replies, mentions), the analyses presented in the following section make use of the simplest, most abundant and stable kind of tie: ‘follows’. While ‘follows’ do not necessarily evince actual communicative interaction between accounts, but only the potential for it (Pavan, Reference Pavan2017), they reflect ‘positive nominations’ (Simpson, Reference Simpson2015) and, when reciprocated, ‘mutual recognition’ (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2020). When one organization’s official account follows another organization’s official account, this allows the follower to keep up with that organization’s activities, therefore reflecting the influence of the followed organization on the activities of the follower organization. More importantly, publicly visible follows suggest to supporters and potential observers a similarity between two organizations. Thus, like hyperlinks between organizational websites (e.g. Vicari, Reference Vicari2014), ‘positive nomination’ ties established by a follower relationship can be understood as a weak online alliance through which food charities improve the flow of information and seek to establish a perception of closeness with similar alters, which in turn may contribute to (re)constructing ‘(sub)movement boundaries around collective identity’ (Simpson, Reference Simpson2015: 49). While we realize that these positive nomination ties on Twitter provide a very limited view of interorganizational relationships—even within the digital sphere—they can still help us understand how to delimit the field’s boundaries and explore its internal dynamics and power asymmetries.

The follower network data were collected in November 2021 using the Twitter Users Network importer in NodeXL (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Ceni, Milic-Frayling, Shneiderman, Mendes Rodrigues, Leskovec and Dunne2010) with the usernames of the 130 selected food charities.Footnote 3 Additionally, to explore hypotheses D1 and D2 (see next subsection) about food charities’ connections with members of proximate external fields we added the Twitter usernames of 29 prominent actors of these of five relevant external fields (see Table 1) based on our previous qualitative analysis of the field (see Table A.2 in online Appendix).

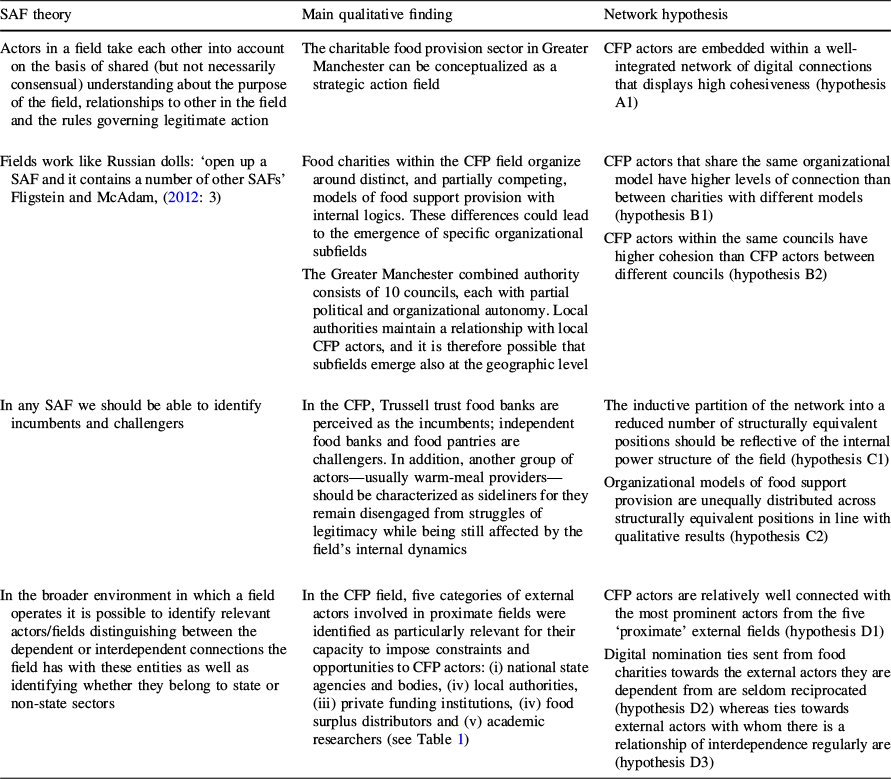

Network Hypotheses

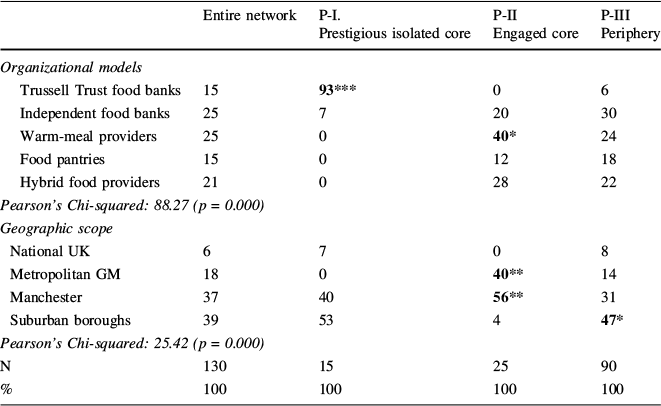

To illustrate and support our claims regarding the compatibility of SAF analytic frameworks and SNA tools, we now formulate eight social network hypotheses derived from qualitative observations A to D (see previous section). We contend that a thorough descriptive analysis of relevant network data guided by these hypotheses will allow us to corroborate, qualify or expand our understanding of the CFP field’s internal dynamics. Table 2 summarizes the correspondence between these hypotheses and both the theoretical expectations of SAF theory and the previous qualitative findings in the context of the CFP field in Greater Manchester.

Table 2 Summary of network hypotheses

SAF theory |

Main qualitative finding |

Network hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

Actors in a field take each other into account on the basis of shared (but not necessarily consensual) understanding about the purpose of the field, relationships to other in the field and the rules governing legitimate action |

The charitable food provision sector in Greater Manchester can be conceptualized as a strategic action field |

CFP actors are embedded within a well-integrated network of digital connections that displays high cohesiveness (hypothesis A1) |

Fields work like Russian dolls: ‘open up a SAF and it contains a number of other SAFs’ Fligstein and McAdam, (Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 3) |

Food charities within the CFP field organize around distinct, and partially competing, models of food support provision with internal logics. These differences could lead to the emergence of specific organizational subfields The Greater Manchester combined authority consists of 10 councils, each with partial political and organizational autonomy. Local authorities maintain a relationship with local CFP actors, and it is therefore possible that subfields emerge also at the geographic level |

CFP actors that share the same organizational model have higher levels of connection than between charities with different models (hypothesis B1) CFP actors within the same councils have higher cohesion than CFP actors between different councils (hypothesis B2) |

In any SAF we should be able to identify incumbents and challengers |

In the CFP, Trussell trust food banks are perceived as the incumbents; independent food banks and food pantries are challengers. In addition, another group of actors—usually warm-meal providers—should be characterized as sideliners for they remain disengaged from struggles of legitimacy while being still affected by the field’s internal dynamics |

The inductive partition of the network into a reduced number of structurally equivalent positions should be reflective of the internal power structure of the field (hypothesis C1) Organizational models of food support provision are unequally distributed across structurally equivalent positions in line with qualitative results (hypothesis C2) |

In the broader environment in which a field operates it is possible to identify relevant actors/fields distinguishing between the dependent or interdependent connections the field has with these entities as well as identifying whether they belong to state or non-state sectors |

In the CFP field, five categories of external actors involved in proximate fields were identified as particularly relevant for their capacity to impose constraints and opportunities to CFP actors: (i) national state agencies and bodies, (iv) local authorities, (iii) private funding institutions, (iv) food surplus distributors and (v) academic researchers (see Table 1) |

CFP actors are relatively well connected with the most prominent actors from the five ‘proximate’ external fields (hypothesis D1) Digital nomination ties sent from food charities towards the external actors they are dependent from are seldom reciprocated (hypothesis D2) whereas ties towards external actors with whom there is a relationship of interdependence regularly are (hypothesis D3) |

First, we aim to corroborate in network terms that food charities in Greater Manchester operate within a bounded and structured SAF, i.e. they take each other into account (finding A). Hypothesis A1 states that the network of digital connections among the considered food providers should exhibit high cohesiveness.

Second, we explore the existence of smaller subfields within the broader metropolitan CFP field (finding B). Given that SAFs are theorized to display a Russian-doll structure, and considering the high heterogeneity within the CFP field in terms of organizational models of food support (i.e. Trussell Trust food banks, independent food banks, warm-meal providers, food pantries and hybrid charities), hypothesis B1 predicts higher levels of connection among charities that share the same organizational model than between charities embracing different models. Additionally, even though the geographic dimension did not receive particular attention in the qualitative exploration of the field, the fact that most of these charities carry out their activities within particular councils of Greater Manchester might also trigger local subfields characterized by high internal cohesion (hypothesis B2).

Third, in order to gain further insight into the hierarchical power structure of the field, we investigate the correspondence between the three distinct power positions identified through fieldwork (incumbents, challengers and sideliners) and the relational structure of the Twitter follower network. Making use of blockmodeling, we reduce the complexity of the network by identifying structurally equivalent positions and describing the relational patterns established between them. Hypothesis C1 expects this inductively identified relational structure to have a significant correspondence with the power structure unveiled through qualitative fieldwork. Hypothesis C2 anticipates charities subscribing to different models of food support to be unequally distributed across structurally equivalent positions. More specifically, in line with qualitative finding C, we would expect the ‘incumbent’ role to be disproportionally populated by Trussell Trust food banks; ‘challenger’ roles to be filled by a large proportion of independent food banks and pantries; and ‘sideliners’ to consist mainly of warm-meal providers and hybrid charities.

Finally, regarding the relationship with the broader environment (finding D), we can expect members of the CFP field to be relatively well connected with the most prominent actors from all five theoretically ‘proximate’ external fields: national state agencies and bodies, private funding institutions, food surplus distributors, local authorities and local academics (hypothesis D1). Moreover, building upon the observation that food charities seem to be dependent on the first three fields, we expect digital nomination ties sent from food charities towards these external actors to be seldom reciprocated (hypothesis D2), whereas the interdependence with local authorities and academics is expected to be reflected in more symmetric relationships where digital ties are often reciprocated (hypothesis D3).

These eight hypotheses are tested in the next section using four main types of quantitative network-analytic tools: whole-network metrics (hypothesis A1), group density analyses (hypotheses B1 and B2), inductive direct blockmodeling (hypotheses C1 and C2) and group reciprocity analyses (hypotheses D1, D2 and D3).

Analyses: Exploring a Digital Network Through the Lenses of Strategic Action Field Theory

Whole-Network Metrics and the Existence of the Charitable Food Provision Field

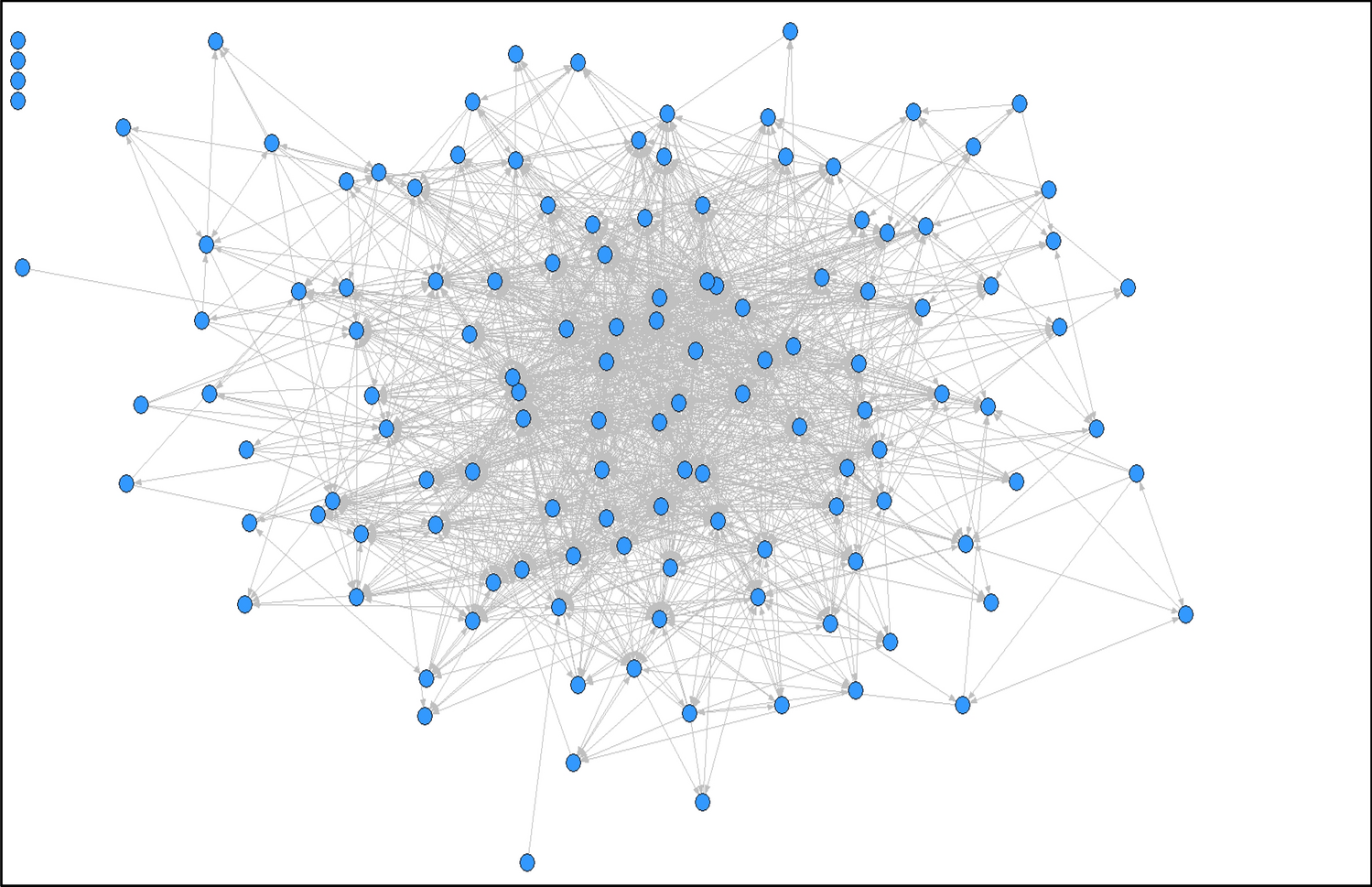

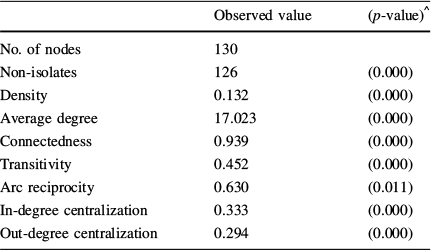

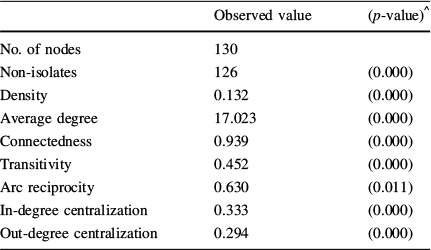

The first step of the analysis was to ascertain the very existence of a strategic action field, that is, to corroborate that food charities active in Greater Manchester are embedded within a delineated and structured interorganizational meso-level social order. For this purpose, we conducted a whole-network analysis concentrating on several conventional indicators of network cohesiveness. High levels of density, connectedness, transitivity and reciprocity would provide strong evidence on the fact that charitable food providers included in the analyses are indeed attuned and interact with one another. Figure 1 displays the network sociogram, and Table 3 presents selected cohesiveness indicators.

Fig. 1 Twitter follower network among the 130 considered CFPs

Table 3 Descriptive whole-network measures of cohesiveness

Observed value |

(p-value)^ |

|

|---|---|---|

No. of nodes |

130 |

|

Non-isolates |

126 |

(0.000) |

Density |

0.132 |

(0.000) |

Average degree |

17.023 |

(0.000) |

Connectedness |

0.939 |

(0.000) |

Transitivity |

0.452 |

(0.000) |

Arc reciprocity |

0.630 |

(0.011) |

In-degree centralization |

0.333 |

(0.000) |

Out-degree centralization |

0.294 |

(0.000) |

^ Proportion of 10,000 equally sized (n = 130) subnetworks randomly sampled from the CFPs’ Twitter environment that displayed values as extreme as the observed in the CFP follower network. See online Appendix for details on p-values calculation (see also Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2020)

Results in Table 3 indicate that the CFP Twitter follower network is indeed cohesive, presenting not only high levels of internal activity, but also high interconnectedness. All but four CFPs form a single component in which food charities either follow each other directly or can indirectly reach any other account through very few intermediaries. Similarly, transitivity, reciprocity and centralization levels are notably high, surpassing those observed in randomly selected Twitter follower networks of equal size. All in all, positive nominations on Twitter among the encompassing list of considered food charities are abundant, often reciprocated, form a tight-knit structure and tend to be concentrated around a minority of popular actors. Thus, whole-network metrics strongly support hypothesis A, confirming the existence of a consolidated charitable food provision field.

Group Density Analyses to Unveil Subfield Dynamics

In a second step, we partition the network into predefined categories and rely on group density analyses to explore the extent to which organizational traits and the specific geographic scope of activity might foster specific subfield dynamics.

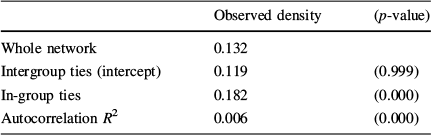

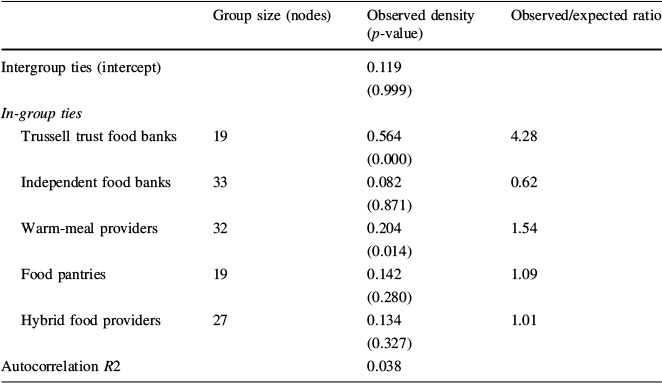

For the partitioning based on organizational models, we found only partial support for the tendencies to homophily posited by hypothesis B1. In-group ties were denser (0.182) than intergroup ties (0.119), but the explanatory power of the constant homophily model (Table 4) was modest, accounting for less than 1% of observed tie distribution. Examining in-group densities separately (Table 5), we observed significant homophily in only two groups: Trussell Trust food banks and warm-meal providers. The density scores food pantries and hybrid food providers do not deviate significantly from the overall density of the network, whereas independent food banks are only sparsely connected with one another. Therefore, independent food banks seem to actually carry out their activities largely ‘independently’, through an ‘organizational mode of coordination’ (Diani, Reference Diani2015) that entails little or no coordination with other charities of any type.

Table 4 Constant homophily model by organizational model

Observed density |

(p-value) |

|

|---|---|---|

Whole network |

0.132 |

|

Intergroup ties (intercept) |

0.119 |

(0.999) |

In-group ties |

0.182 |

(0.000) |

Autocorrelation R 2 |

0.006 |

(0.000) |

Table 5 Variable homophily model by organizational model

Group size (nodes) |

Observed density (p-value) |

Observed/expected ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Intergroup ties (intercept) |

0.119 (0.999) |

||

In-group ties |

|||

Trussell trust food banks |

19 |

0.564 (0.000) |

4.28 |

Independent food banks |

33 |

0.082 (0.871) |

0.62 |

Warm-meal providers |

32 |

0.204 (0.014) |

1.54 |

Food pantries |

19 |

0.142 (0.280) |

1.09 |

Hybrid food providers |

27 |

0.134 (0.327) |

1.01 |

Autocorrelation R2 |

0.038 (0.000) |

||

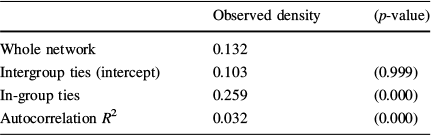

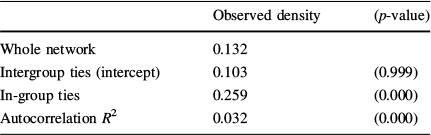

When partitioning the network by the geographic scope we find even stronger tendencies to homophily than for partition by organizational model. Indeed, a simple constant homophily model (Table 6) explains a non-negligible 3% of tie distribution variance. Additionally, all but two of the twelve geographic groups examined present statistically significant inbreeding tendencies (see Table A.3 in online Appendix). Thus, it is possible to discern multiple cohesive local subfields within the broader metropolitan CFP field, supporting hypothesis B2.

Table 6 Constant homophily model by geographic scope

Observed density |

(p-value) |

|

|---|---|---|

Whole network |

0.132 |

|

Intergroup ties (intercept) |

0.103 |

(0.999) |

In-group ties |

0.259 |

(0.000) |

Autocorrelation R 2 |

0.032 |

(0.000) |

Direct Blockmodelling: Structural Equivalence and Power Positions within the Field

Positional approaches to SNA developed within mathematical sociology are a helpful approach for reducing the complexity of network data, identifying subgroups of actors that are similarly positioned within the network. Relational positions are understood as clusters of actors with similar patterns of connection to other actors and are typically associated with differentiated statuses within a given social system (e.g. Burt, Reference Burt1980). A common way of defining this similarity is through ‘structural equivalence’ (Lorrain & White, Reference Lorrain and White1971): two actors would be perfectly equivalent if they connect to exactly the same set of actors in the network. In this part of the analyses, we explore the extent to which the simplification of our Twitter follower network into three structurally equivalent clusters is congruent with the fieldwork-based description of internal power hierarchies within the CFP field (incumbents, challengers and sideliners).

For these analyses, we use generalized blockmodelling (Batagelj et al., Reference Batagelj, Ferligoj and Doreian1992; Doreian et al., Reference Doreian, Batagelj and Ferligoj2005), under which blockmodels are ‘directly obtained from the network data by optimizing a criterion function, typically with a relocation algorithm’ (Matjasic et al., Reference Matjasic, Cugmas and Ziberna2020: 52). Blockmodelling was conducted in an inductive, exploratory fashion, keeping pre-specifications to a minimum, merely specifying the number of desired positions (here, three) and allowed block types (here, complete or null). The analyses were run through the R package ‘blockmodeling’ (Žiberna, Reference Žiberna2019).

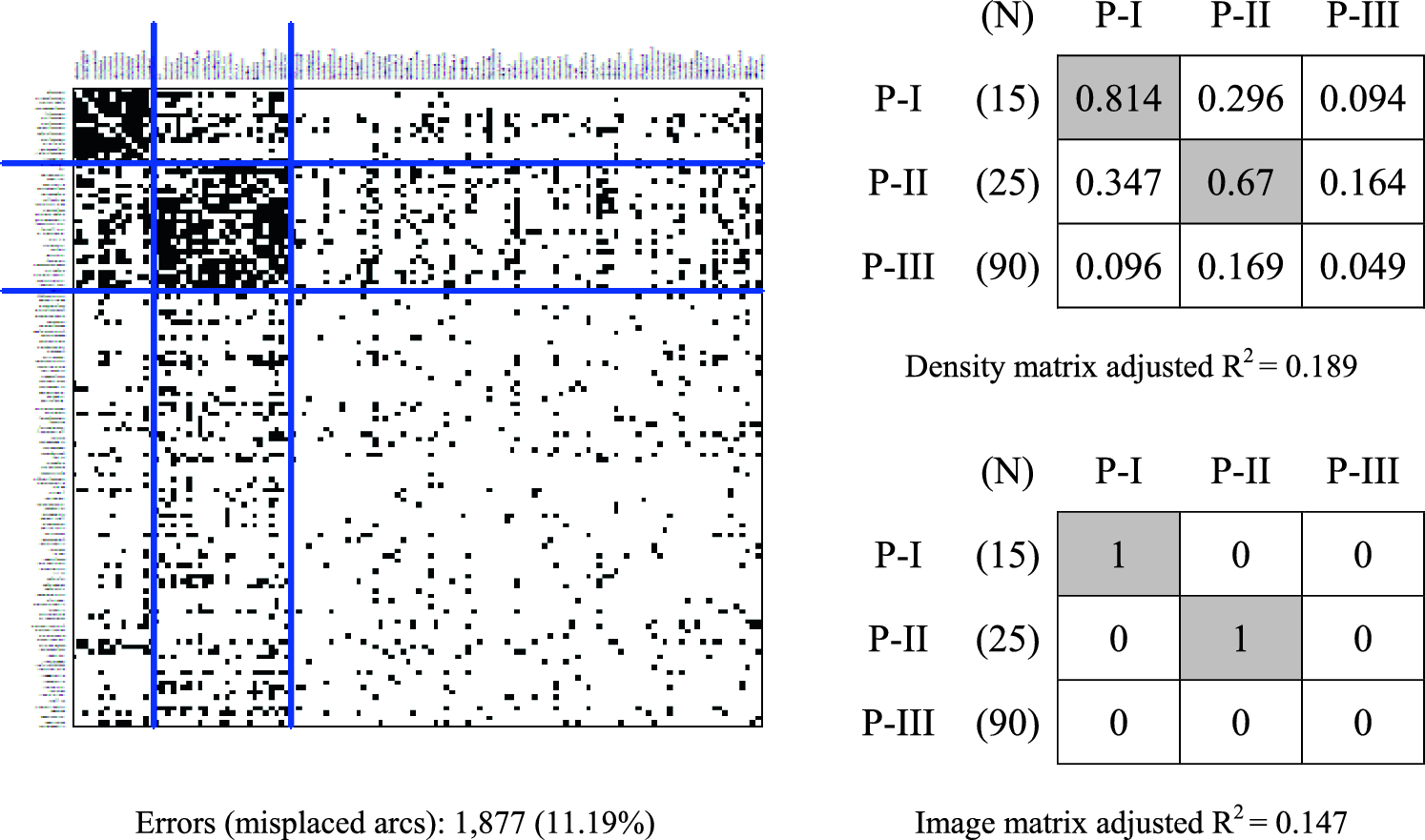

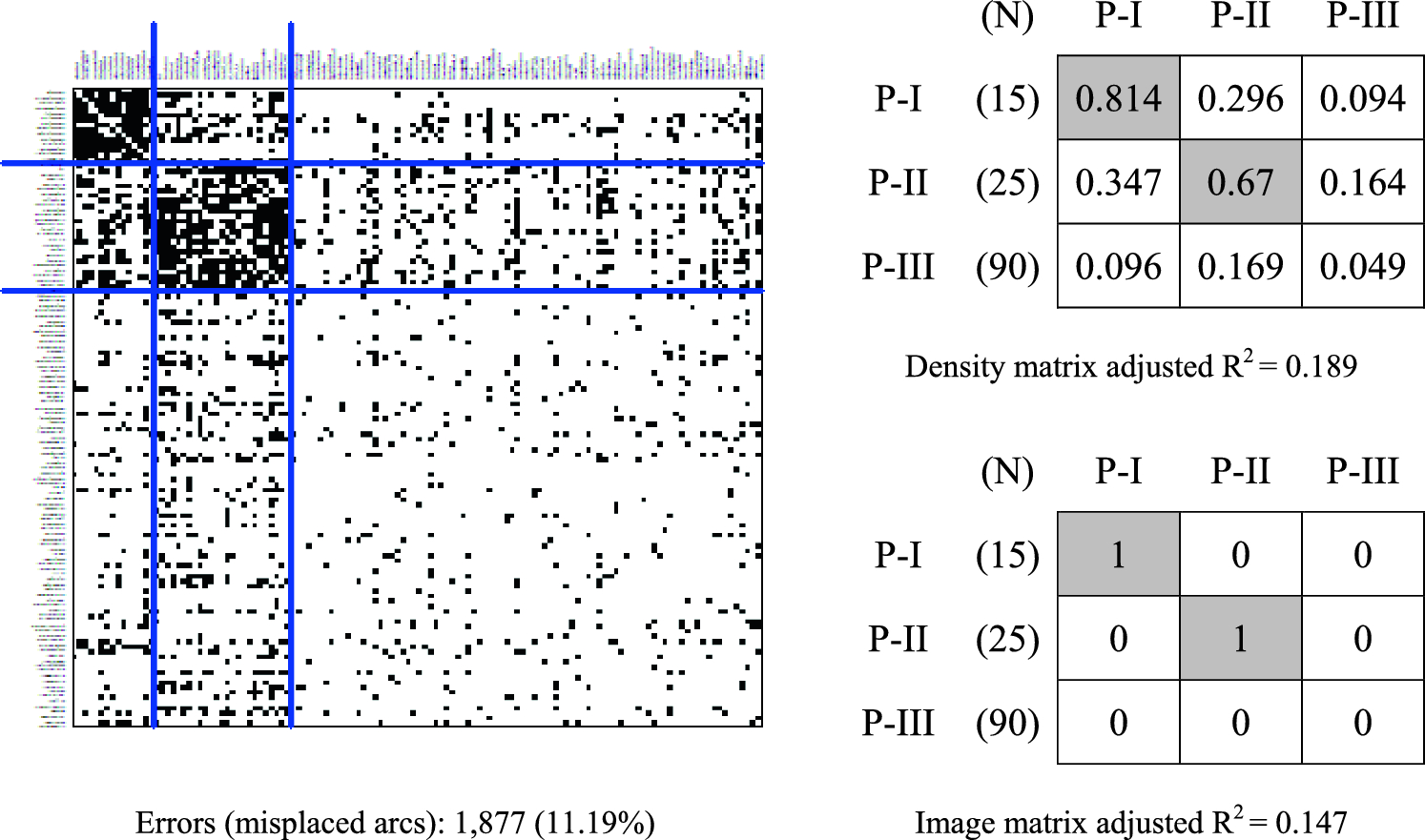

The results presented in Fig. 2 reveal an interesting variation on a core–periphery structure,Footnote 4 On the one hand, the vast majority of CFPs fall in the periphery (P-III), being sparsely connected among one another and only moderately with more central actors. On the other hand, these central actors can be split into two cohesive subgroups. Accounts in the first one (P-I) receive more ‘follows’ than they send and at the same time are weakly connected with peripheral charities, whereas accounts in the second (P-II) engage much more with less popular actors. This simplified representation of the network structure is compatible to some extent with the relational patterns that would be expected from incumbents (P-I), challengers (P-II) and sideliners (P-III), thus providing moderate support for hypothesis C1.

Fig. 2 Optimized 3-cluster blockmodeling partition: reordered matrix (left), density matrix (upper right) and simplified image matrix (bottom right)

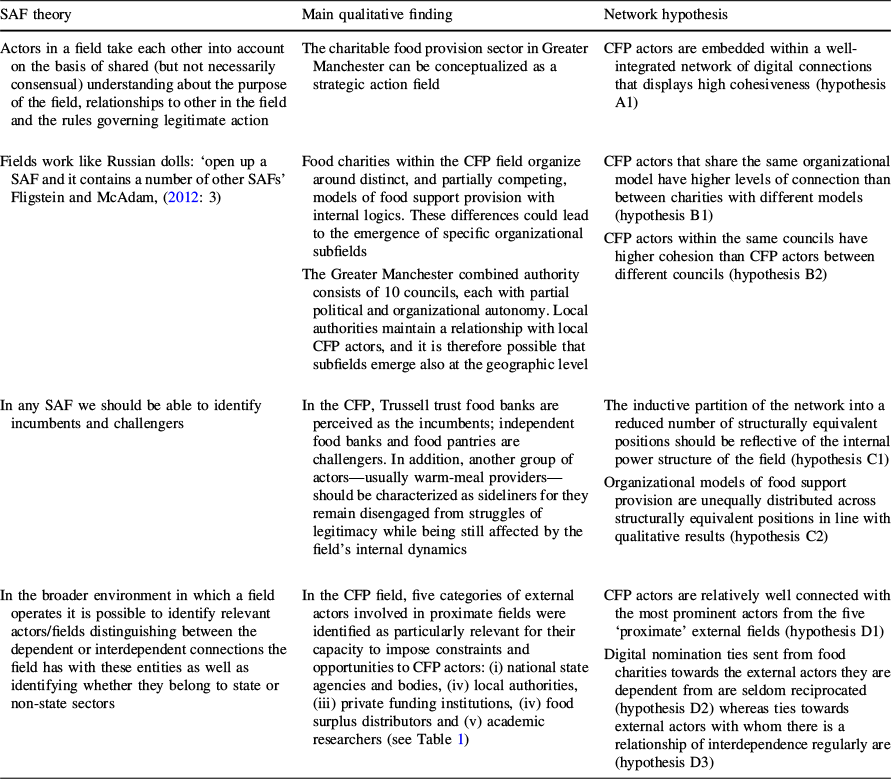

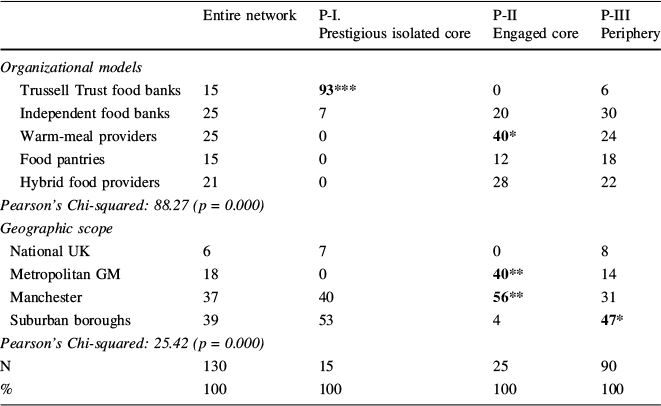

When we move to a closer assessment of the composition of each structurally equivalent position (Table 7), we can see that organizational characteristics and geographic spheres of action are not randomly distributed across the three basic, structurally equivalent positions in the network. However, the associations do not fully correspond with the expectations of hypothesis C2. While the P-I position, the most compatible with the incumbent role, indeed includes fourteen of the nineteen Trussell Trust food banks, warm-meal providers are found slightly more often in the P-II position rather than in the (peripheral) P-III. Conversely, very few presumed challengers such as food pantries and independent food banks—including the account of the umbrella group IFAN—were placed in the engaged core position (P-II), which can be interpreted as the position most congruent with the challenger role. Finally, when breaking down the composition of relational positions by geographic coverage we find, unsurprisingly, that organizations based in the city of Manchester and/or present across the entire metropolitan area are more likely to occupy a core position, while suburban-only organizations tend to be peripheral.

Table 7 Contingency table of placement in structurally equivalent positions by organizational models and geographic scope (column percentages)

Entire network |

P-I. Prestigious isolated core |

P-II Engaged core |

P-III Periphery |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Organizational models |

||||

Trussell Trust food banks |

15 |

93*** |

0 |

6 |

Independent food banks |

25 |

7 |

20 |

30 |

Warm-meal providers |

25 |

0 |

40* |

24 |

Food pantries |

15 |

0 |

12 |

18 |

Hybrid food providers |

21 |

0 |

28 |

22 |

Pearson’s Chi-squared: 88.27 (p = 0.000) |

||||

Geographic scope |

||||

National UK |

6 |

7 |

0 |

8 |

Metropolitan GM |

18 |

0 |

40** |

14 |

Manchester |

37 |

40 |

56** |

31 |

Suburban boroughs |

39 |

53 |

4 |

47* |

Pearson’s Chi-squared: 25.42 (p = 0.000) |

||||

N |

130 |

15 |

25 |

90 |

% |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Positive statistical associations highlighted in bold; *p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01

Group Reciprocity Analyses to Assess (Inter)Dependencies with External Actors

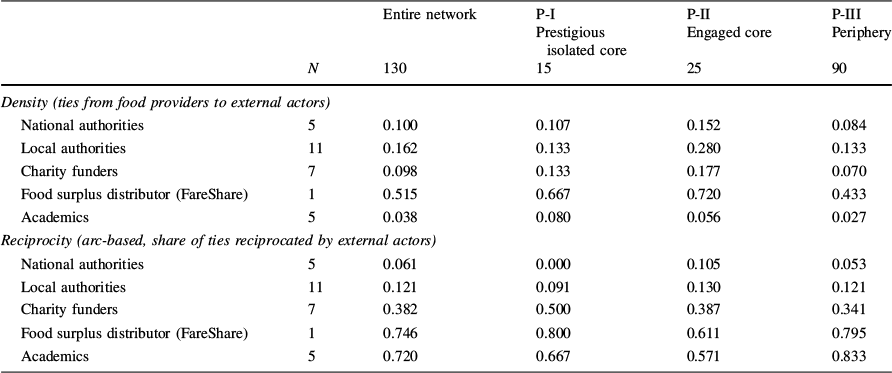

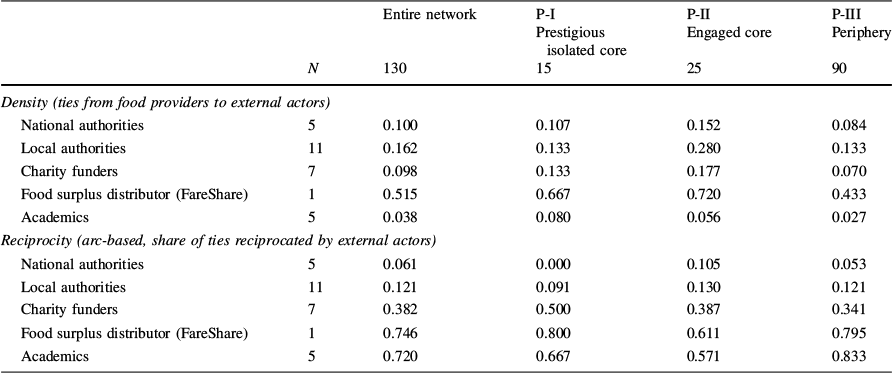

Group reciprocity analyses allow us to assess the extent to which the relationships between the CFP field and relevant external actors mirror the expectations of proximity and (inter)dependence derived from the qualitative fieldwork (hypotheses D1, D2 and D3). Table 8 reports how often CFPs—separated into the different structurally equivalent positions identified in the previous subsection—follow selected external actors, as well as the proportion of those ties that are reciprocated by the latter.

Table 8 Densities and reciprocity between members of the CFP field and selected prominent actors from relevant external fields

Entire network |

P-I Prestigious isolated core |

P-II Engaged core |

P-III Periphery |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

N |

130 |

15 |

25 |

90 |

|

Density (ties from food providers to external actors) |

|||||

National authorities |

5 |

0.100 |

0.107 |

0.152 |

0.084 |

Local authorities |

11 |

0.162 |

0.133 |

0.280 |

0.133 |

Charity funders |

7 |

0.098 |

0.133 |

0.177 |

0.070 |

Food surplus distributor (FareShare) |

1 |

0.515 |

0.667 |

0.720 |

0.433 |

Academics |

5 |

0.038 |

0.080 |

0.056 |

0.027 |

Reciprocity (arc-based, share of ties reciprocated by external actors) |

|||||

National authorities |

5 |

0.061 |

0.000 |

0.105 |

0.053 |

Local authorities |

11 |

0.121 |

0.091 |

0.130 |

0.121 |

Charity funders |

7 |

0.382 |

0.500 |

0.387 |

0.341 |

Food surplus distributor (FareShare) |

1 |

0.746 |

0.800 |

0.611 |

0.795 |

Academics |

5 |

0.720 |

0.667 |

0.571 |

0.833 |

Focusing first on density scores, the fact that many core food charities are interested in following the information shared by these external actors on Twitter indicates how close these external fields are to the CFP. In other words, CFPs (especially those in core positions) seem to share a general sense of being affected by the actions of all these external actors, except for academics, which seems a relatively more distant field. Thus, all in all, hypothesis D1 receives significant support.

On the other hand, reciprocity levels reported in the bottom panel of Table 8 show the relative symmetry or asymmetry of existing digital connections between CFPs and each of these five proximate external fields, which in turn can arguably be associated with the power relationships that exist between them.Footnote 5 The arc-based reciprocity metric reports how often a CFP’s ‘follow’ is returned by prominent external actors; therefore, levels equal or above 0.5 indicate horizontal relationships and mutual interest, whereas lower scores indicate unbalanced relationships in which external actors remain mostly uninterested in the digital activities of food charities.

This second, asymmetric scenario was expected for national authorities, private funders and food surplus distributors under hypothesis D2. However, this expectation is only supported for national authorities, while digital connections with private charitable funders and FareShare were more symmetrical than expected. Similarly, the expectations of symmetry formulated in hypothesis D3 were only partly supported. While academics show high reciprocity, ties with local authorities are severely unbalanced, contrary to expectation.

Discussion and Conclusion

Taking the case of the charitable food provision field, this article proposed an original approach: to combine SAF theory with the application of SNA to organic digital data from Twitter. The idea of exploiting network data to visualize and study fields is certainly not new—several authors have noted that such data lets us map the structure of recognition, patterns of prestige and tendencies to homophily (e.g. Bottero & Crossley, Reference Bottero and Crossley2011; De Nooy, Reference De Nooy2003; Lindell, Reference Lindell2017; Serino et al., Reference Serino, D’Ambrosio and Ragozini2017). The encounter between SAF theory and SNA, however, has remained undertheorized and underdeveloped, despite the theory presenting innovative features that are worth analysing with network data and that could further advance the debate. On a general level, the paper demonstrates that combining the structured approach of SAF theory with the analytical methods of SNA can enhance our understanding of field dynamics and create a virtuous cycle that can inspire researchers to continually expand, reassess and refine their research questions, data collection methods and hypotheses. In addition, the study provides a valuable methodological guide to apply SNA in other strategic action fields, particularly in the non-profit sector.

Building on an earlier examination of the intra- and interfield relationships of several food charities based in Greater Manchester (Oncini, Reference Oncini2022a; Reference Oncini2023), we used Twitter follower relationships to further investigate and triangulate some of that study’s qualitative findings with common network-analytic metrics. First, whole-network measures permitted us to ascertain the existence of the field itself (A). The selected organizations do indeed take each other into account, are highly interconnected and tend to reciprocate each other at high rates, certainly much more than what would be expected by chance.

Second, we took into consideration the field’s ‘Russian-doll structure’, namely the possibility that within the CFP field we can discern smaller SAFs (B). In their work, Fligstein and McAdam write ‘open up a SAF and it contains a number of other SAFs’ (Fligstein & McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012: 3), but do not reflect further on how to find lower-level fields. The results of the group density analyses are thought-provoking and could be taken as indicating where one could find subfields (or not): we find higher levels of homophily between food banks that are part of the Trussell Trust network and among warm-meal providers than between independent food banks—in a sense, confirming their ‘independence’—and between hybrid CFPs—possibly signalling the lack of a precise reference model and purpose. Additionally, we find higher levels of homophily among providers operating in the same council, suggesting that (sub)field dynamics are probably also at work spatially. Together, these results underline the importance of selective attention when ‘opening up’ a field, for not all organizations with similar ends may be involved in a SAF themselves.

Third, since the field presents relatively high levels of centralization, with a disproportionate share of ties concentrated among few organizations, we examined whether the structural positions of the charities in the network are isomorphic to their power role in the field—i.e. if there is a strong correspondence between both structures (C). To do this, we relied on inductive direct blockmodelling. The three-cluster solution is mostly compatible with the relational patterns one would expect from incumbents, challengers and sideliners: ‘incumbents’ are popular actors, ‘challengers’ more engaged with less popular actors—potentially looking for alliances to challenge the incumbents—and ‘sideliners’ connect sparsely with a vast majority of charities and link moderately with more central actors. As expected, we find most Trussell Trust food banks (as well as the national account) in the incumbent cluster; contrary to the evidence built with qualitative data, however, the engaged core (P-II) is mostly constituted by warm-meal providers, while independent food banks (and the IFAN national account) end up in the periphery. This seems puzzling at first, but it points to the benefits of mixing qualitative and network data. The fact that warm-meal providers end up in the challenger position could be wrongly interpreted if one did not have qualitative data telling us that IFAN and pantries, not warm-meal providers, have been challenging the dominant Trussell Trust franchise model for several years. After all, it is the alternative, confrontational framing proposed by the challenger that makes it a challenger, not merely its position in a blockmodel. Nevertheless, this result indicates new lines of investigation as well as suggesting warm-meal providers to contact, to examine further their role in the field. For instance, it is possible that since they present themselves as such, sideliners follow many other accounts to observe what is going on from a more neutral position; at the same time, they are seen as competitors neither by incumbents nor by established challengers, and therefore may enjoy more prestige and sympathy, later converted into ‘follows’.

Fourth, we looked at the broader field environment by analysing intergroup ties, assuming that digital connections with pre-specified external fields may be taken as signals of dependence and interdependence (D). Density scores and arc-based reciprocity metrics partly support our initial hypotheses: most external actors are followed by the food charities in our sample—especially core CFPs—implying that they are key elements of the broader field environment that permit a better grasp of field dynamics. The (a) symmetry of the connections, however, is not clear-cut: as expected we find asymmetric relationships between CFPs and national authorities, but levels of reciprocity with funders and with FareShare (the hegemonic food surplus distributor) are notably high. In the first case, a closer look reveals that this reciprocity is mainly with funders based in Greater Manchester, suggesting that geographic proximity should be taken into account to distinguish between levels of interdependence in the broader field environment. The high levels of reciprocity with FareShare require some context. Although this may seem contradictory at first, it is important to recall that during the COVID-19 crisis the food surplus distributor temporarily invaded the CFP field. During the emergency FareShare operated across fields by distributing both surplus food and new food, donated by companies, to charities across the UK (Oncini, Reference Oncini2022a; Reference Oncini2023). Although we do not have data on the pre-COVID ties, it is likely that during that period FareShare increased the number of accounts it followed as a way to get more in touch with the CFP field dynamics. In addition, FareShare started to support the food pantry model, while openly challenging the food bank model. This attempt to support challengers may have pushed the surplus distributor to be more involved in CFP field dynamics and to increase the number of ties with food charities.

Lastly, we find reciprocal relationships with academics, but not with local authorities. The academic field, however, seems relatively ‘distant’ from the CFP field with few in-degree ties, but we should keep in mind that the types of ties created are more important than their number: in this sense, qualitative data reveal the relationships of cooperation developed between some scholars and larger food charities, both incumbents and challengers. In the case of local authorities, it could be that where the number of followers of institutional accounts is too large, this inhibits reciprocity. As argued elsewhere (Oncini, Reference Oncini2023), further research is necessary to understand the relationships of cooperation and conflict between local governments and food charities: the former keep very well informed on the food support initiatives taking place in their territories, and the latter often keep in touch and meet representatives and officials.

The approach here proposed is not free from limitations. Clearly, our analyses were guided by the expectation that power relationships within the field could be partly reflected in the relational structure of the digital network. This creates the possibility of a twofold bias. On the one hand, Twitter contains a self-selected sample of food charities, and results might differ if we examined a broader population. On the other, Twitter follower relationships are simple signals that could hide much more complex opinions, alliances and practices. Moreover, it should be noted that while larger organizations may employ social media managers and explicit rules of engagement, smaller CFPs may be more spontaneous, or several persons might speak for them. This, in turn, could have an impact on how follows are distributed. Nevertheless, despite these inherent limitations on the approach, we believe there are very good reasons to take it into account.

As we demonstrate here, Twitter network data could help explore field dynamics after the collection and analysis of qualitative data. For instance, simple whole-network measures could help identifying important actors that were previously neglected and highlight potential contradictions that are worth investigating in detail. At the same time, we believe that Twitter data could become advantageous when approaching the study of a field, before starting to collect qualitative data. If one had a vague idea about who the important actors were or its boundaries, downloading the follower network could help set priorities and identify who to get in touch with to start the investigation. Also, if one lacked a register of the potential field members, Twitter’s account suggestions could be handy at the beginning. Suggestions are based on previous activity and geolocation, and one could start a trial-and-error mining of suggested accounts simply by setting up a new account. We are clearly aware that only a minority of fields’ networks may be available on Twitter and that survey-based network data could be much more refined and informative than the simple observed follower ties. Indeed, nothing prevents researchers from exploring other social media platforms with open APIs, nor from obtaining finer network data at a later stage to complement the limited and often quite shallow information that digital trace data can provide. Furthermore, it should be noted that, as it has become evident over the last couple of years, the social media landscape is extremely dynamic and can suffer deep transformations in very short periods of time, with emerging successful competitors, and unanticipated external disruptions, leading to data collection opportunities that constantly arise or disappear. Nevertheless, at present, the massive presence of third-sector organizations on Twitter, coupled with the high practicality of the approach, suggest that many researchers could obtain good, insightful data to make their analysis more convincing and sound.

Funding

This research was supported by the H2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship (Grant Number 838965), the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow 22F22755), and the Sustainable Consumption Institute (University of Manchester) internal fund.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The research reported here obtained ethical clearance from the University of Manchester Ethics Committee (2020–9377-15273).