Introduction

For a long time, the Neoproterozoic was considered to be the time of the onset of modern-style plate tectonics considering the first appearance of blueschist, abundant eclogite and even ultra-high-pressure rocks (Maruyama and Liou, Reference Maruyama and Liou1998; Jahn et al., Reference Jahn, Caby and Monie2001; Stern, Reference Stern2005). However, to date, at least eight major occurrences worldwide show that eclogite had already formed during the Palaeoproterozoic, ∼2 Ga ago: in Tanzania at 1.89–2.0 Ga (U/Pb zircon; Möller et al., Reference Möller, Appel, Mezger and Schenk1995; Boniface et al., Reference Boniface, Schenk and Appel2012), in Cameroon at 2.09 Ga (U/Pb zircon; Loose and Schenk, Reference Loose and Schenk2018), in the Democratic Republic of the Congo at 2.09 Ga (rutile/zircon U/Pb; François et al., Reference François, Debaille, Paquette, Baudet and Javaux2018), in the Canadian Shield at 1.90–1.91 Ga (zircon U/Pb; Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Bowring, Williams and Williams2004) and at 1.83 Ga (U/Pb monazite in garnet; Weller and St-Onge, Reference Weller and St-Onge2017), in Greenland at 1.88–1.89 Ga (U/Pb rutile, monazite, zircon; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Dziggel, Kolb and Sindern2018), in NE China at 1.80–1.85 Ga (U/Pb zircon; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wei and Chu2020; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Kynický, Song, Tao, Li, Li, Yang, Pohanka, Galiova, Zhang and Fei2018) and particularly well studied in Karelia/Russia at 1.83–1.96 Ga (U/Pb zircon; Skublov et al., Reference Skublov, Astaf’ev, Berezin, Marin, Mel’nik and Presnyakov2011; Mel’nik et al., Reference Mel’nik, Skublov, Marin, Berezin and Bogomolov2013, Reference Mel’nik, Skublov, Rubatto, Müller, Li, Li, Berezin, Herwartz and Machevariani2021; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Slabunov and Bader2017, Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023; Imayama et al., Reference Imayama, Oh, Baltybaev, Park, Yi and Jung2017; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Zhang, Zhang, Wei, Li, Guo, Bader and Qi2019a; Lu/Hf garnet: Herwartz et al., Reference Herwartz, Skublov, Berezin and Mel’nik2012, Yu et al., Reference Yu, Zhang, Lanari, Rubatto and Li2019b, Mel’nik et al. Reference Mel’nik, Skublov, Rubatto, Müller, Li, Li, Berezin, Herwartz and Machevariani2021; Fig. 1). All these eclogite localities occur along suture zones that belong to collisional belts which finally led to the formation of the first supercontinent “Columbia” (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Cawood, Wilde and Sun2002, Reference Zhao, Sun, Wilde and Li2004).

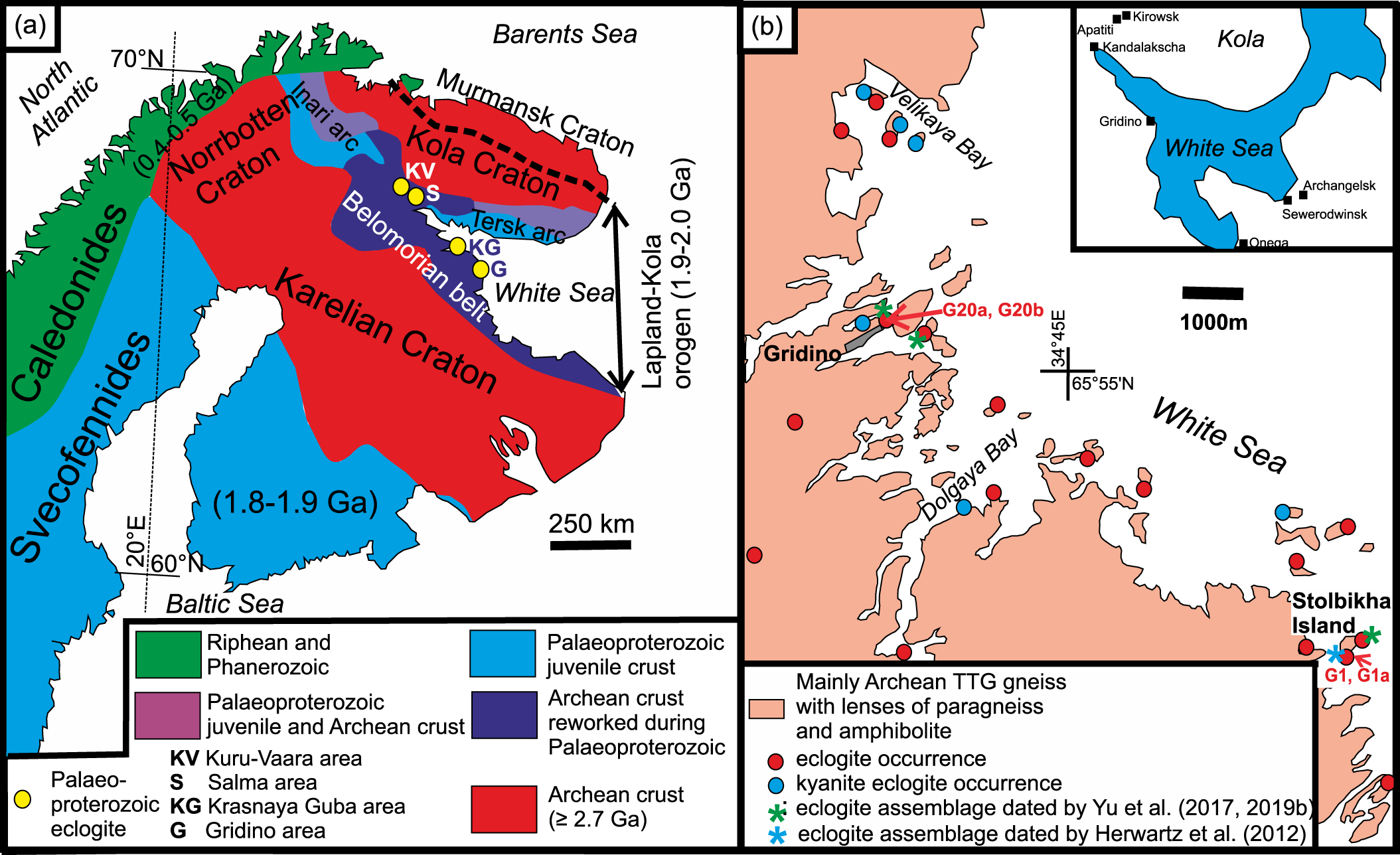

Figure 1. (a) Major tectonic units of the Fennoscandian shield (redrawn after Slabunov et al., Reference Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019, Reference Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2021) and the location of the Palaeoproterozoic retro-eclogite occurrences within the Belomorian Belt. (b) Simplified map of sample locations and eclogite occurrences in the Gridino area (after Sibelev, Reference Sibelev and Golubev2012 in Slabunov et al., Reference Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019).

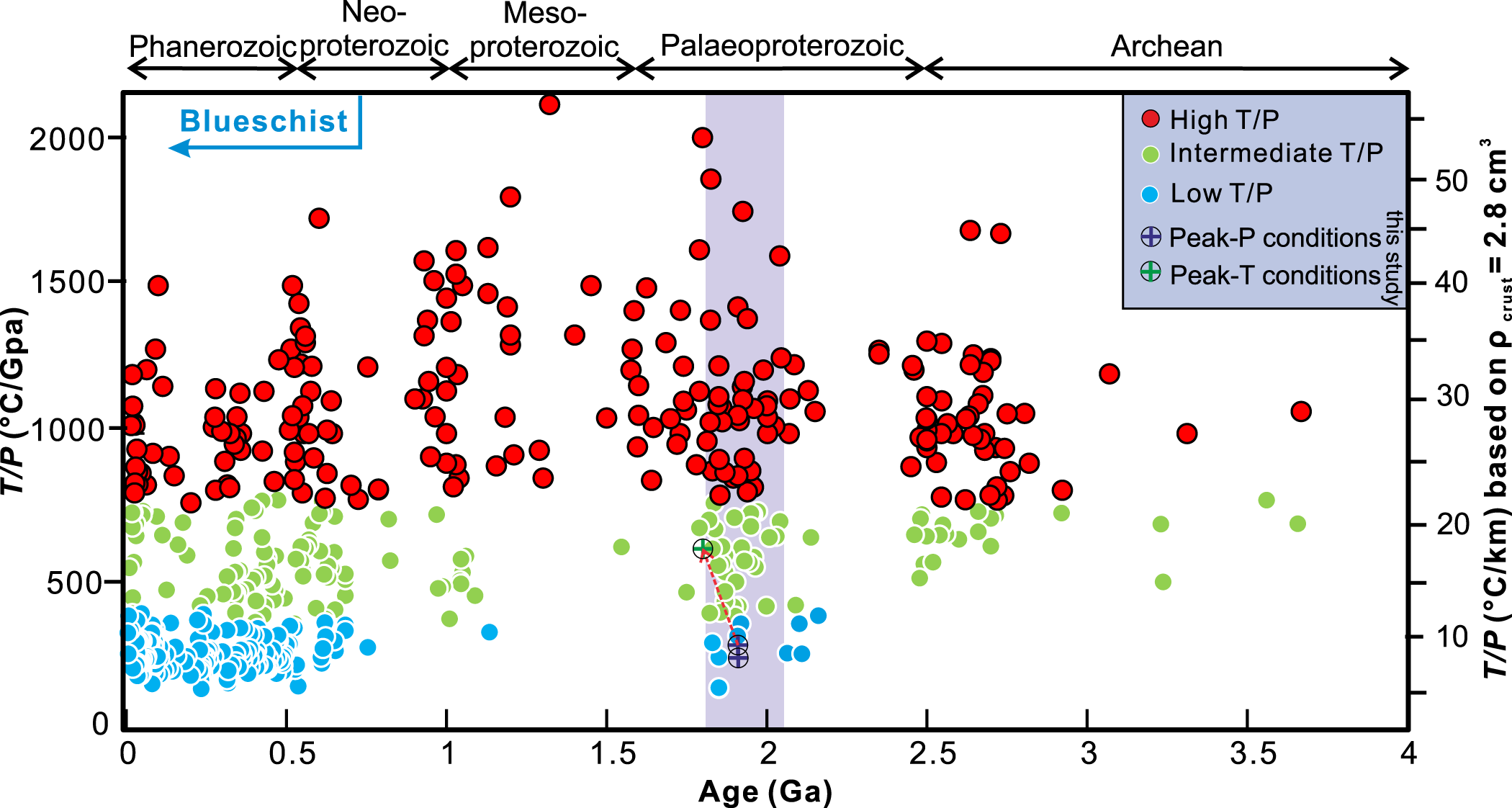

These high-pressure (HP) rocks are crucial in evaluating whether modern-style plate tectonics already had operated during subduction and collision in the Palaeoproterozoic. In this respect, low thermobaric ratios <375°C/GPa indicate ‘cold’ and hence ‘deep’ subduction as in modern-style subduction zone environments, i.e. at initially low transient metamorphic gradients of 5–12°C/km. Such conditions are common for Phanerozoic and Neoproterozoic eclogites and blueschists. However, they are sparsely reported from Palaeoproterozoic eclogites (Brown and Johnson, Reference Brown and Johnson2018, Reference Brown and Johnson2019; Brown, Reference Brown2023). By contrast, ‘warm’ subduction under an intermediate thermobaric ratio between 775 and 375°C/GPa, as shown by some high-pressure granulite and eclogite occurrences, is known to have already prevailed from the Mesoarchaean onwards (Brown and Johnson, Reference Brown and Johnson2018, Reference Brown and Johnson2019; Brown, Reference Brown2023).

However, studies of most ∼2 Ga HP occurrences revealed either a pressure peak at high temperature (HT) and/or a HP-granulite-facies overprint. High temperature (HT) metamorphism commonly obliterates prograde PT conditions, especially of peak pressure conditions. This leads to many different P-T estimates particularly in the well-studied Belomorian retro-eclogite occurrences which would rather point to ‘warm’ subduction conditions around 390–480°C/GPa (see list of citations in Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023). By contrast, Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023) reported evidence for a low T/P gradient of 303 ±16°C/GPa (7.9–8.4°C/km) for the peak-pressure conditions during subduction, clearly indicating a modern-style plate-tectonic regime. This conclusion is based on pseudosection modelling focussing on relict garnet core compositions (involving prograde growth zonation) in retro-eclogite from the northern part of the Belomorian belt (Salma area; Fig. 1). Here, peak pressure (peak-P) eclogite-facies conditions of 650–670°C, 22–23 kbar were estimated. Estimates close to these results were also previously obtained by Perchuk and Morgunova (Reference Perchuk and Morgunova2014) using traditional reverse modelling. Even potential ultra-high-pressure (UHP) conditions were considered locally (Morgunova and Perchuk, Reference Morgunova and Perchuk2012). Thus, it appears to be rather a matter of the geothermobarometric method to re-evaluate whether cold or warm transient gradients are represented by the Belomorian (retro)eclogite.

In view of the necessity of further confirmation of Palaeoproterozoic ‘cold’ subduction, our current study focuses on PT pseudosection modelling determining peak-P (eclogite-facies) conditions in biotite-free retro-eclogite from Stolbikha Island and a rare Mg-rich biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite and biotite gneiss from Gridino village, both in the southern part of the Belomorian belt (Fig. 1b). The ages of the latter two rock samples from Gridino village were determined using the Rb/Sr system to obtain information on the time of exhumation. Furthermore, conditions of the intensive HP granulite-facies overprint in these rocks at peak temperatures (peak-T) are newly estimated using zircon-in-rutile thermometry and quartz-in-garnet elastic thermobarometry.

Geological setting

Eclogite-facies rocks in Karelia (Russia) occur in the oldest part of the Fennoscandian shield within the Belomorian belt and are considered to be a result of a Palaeoproterozoic continent–continent collision between the Palaeo-Mesoarchaean Karelian and Kola cratons (Lapland-Kola orogen; Slabunov et al., Reference Slabunov, Lobach-Zhuchenko, Bibikova, Sorjonen-Ward, Balagansky, Volodichev, Shchipansky, Svetov, Chekulaev, Arestova, Stepanov, Gee and Stephenson2006, Reference Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019, Reference Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2021; Fig. 1a). The Belomorian belt is mainly composed of Meso-/Neoarchaean, partly migmatitic tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTG) gneiss (2.72–2.90 Ga) and subordinate paragneiss (2.78–2.89 Ga) formed during early continental growth. These units also host veins of pegmatite and large Meso-/Neoarchaean greenstone complexes (2.65–3.10 Ga), as well as ubiquitous small lenses of eclogite, amphibolite and pyroxenite (former veins; protolith ages of 2.18–2.88 Ga; Slabunov et al., Reference Slabunov, Lobach-Zhuchenko, Bibikova, Sorjonen-Ward, Balagansky, Volodichev, Shchipansky, Svetov, Chekulaev, Arestova, Stepanov, Gee and Stephenson2006, Reference Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019, Reference Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2021; Skublov et al., Reference Skublov, Berezin, Mel’nik, Astafiev, Voinova and Alekseev2016; Lahtinen and Huhma, Reference Lahtinen and Huhma2019). The Belomorian eclogite occurrences were shown to have mostly affinities to N- and E-MORB composition (Imayama et al., Reference Imayama, Oh, Baltybaev, Park, Yi and Jung2017; Konilov et al., Reference Konilov, Shchipansky, Mints, Dokukina, Kaulina, Bayanova, Dobrzhinetskaya, Cuthbert, Faryad and Wallis2011; Mints et al., Reference Mints, Dokukina and Konilov2014; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Zhang, Wei, Li and Guo2017). Structurally, the Belomorian belt consists of several deep-seated, southwest-vergent nappes thrusted onto the Palaeo-/Mesoarchaean Karelian craton. Nevertheless, the Kola craton is regarded as the lower plate during collision and experienced a southwestward subduction below the Inari/Kersk arcs (1.92–1.96 Ga) and a subsequent Palaeoproterozoic collision (Lahtinen and Huhma, Reference Lahtinen and Huhma2019). In this context, the eclogite lenses are considered to occur along a NW–SE-trending cryptic suture. Most structures are also NW–SE trending within the Lapland-Kola orogen. Granulite- to amphibolite-facies metamorphism occurred during both the Archaean and the Palaeoproterozoic.

Metamorphic conditions and their timing for eclogite bodies concentrating in four regions are much debated (Kuru-Vaara, Salma, Krasnaya Guba and Gridino areas; Fig. 1a). So far, wide ranges of PT estimations were reported roughly ranging between 650–850°C, 16–18 kbar for the eclogite stage and 700–900°C, 9–12 kbar for the high-pressure granulite-facies overprint (see summary by Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023). Ages in the range of 1.83–1.96 Ga were determined ubiquitously in all areas mainly by U/Pb zircon geochronology and perfectly confirmed by direct dating of eclogite assemblages by Lu/Hf garnet-omphacite isochrons (Herwartz et al., Reference Herwartz, Skublov, Berezin and Mel’nik2012, Yu et al., Reference Yu, Zhang, Lanari, Rubatto and Li2019b, Mel’nik et al., Reference Mel’nik, Skublov, Rubatto, Müller, Li, Li, Berezin, Herwartz and Machevariani2021). By contrast, a number of authors have suggested an earlier, Archaean eclogite-facies metamorphic event on the basis of U/Pb age determination of metamorphic zircon in the same regions and partly in the same rocks (2.72–2.87 Ga; e.g. Volodichev et al., Reference Volodichev, Slabunov, Bibikova, Konilov and Kuzenko2004, Reference Volodichev, Maksimov, Kuzenko and Slabunov2021; Mints et al., Reference Mints, Belousova, Konilov, Natapov, Shchipansky, Griffin, O’Reilly, Dokukina and Kaulina2010; Shchipansky et al., Reference Shchipansky, Khodorevskaya and Slabunov2012; Balagansky et al., Reference Balagansky, Maksimov, Gorbunov, Gorbunova, Mudruk, Sidorov, Sibelev and Slabunov2024), although a true Archaean eclogitic assemblage is not yet confirmed by direct dating of garnet-omphacite isochrons nor by PT estimates

Potentially, metamorphic Archean zircon (with clinopyroxene inclusions of low jadeite component only) do not unequivocally indicate eclogite facies conditions, but could rather represent inherited relics of an earlier Archaean granulite- or amphibolite-facies event which is ubiquitously recorded throughout the entire Belomorian belt (Imayama et al., Reference Imayama, Oh, Baltybaev, Park, Yi and Jung2017; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Slabunov and Bader2017, Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023). The 2.7 Ga metamorphic zircons could also be relics of an earlier local metamorphism incorporated as xenocrysts within the magmatic protoliths of the eclogite. Certainly, rocks from different crustal levels were probably subducted to eclogite-facies conditions during collision.

The samples: petrographical characteristics and mineral compositions

We selected four samples from two localities in the Gridino area: (1) samples G1 and G1a are strongly retrogressed eclogite (retro-eclogite) from the SW of Stolbikha Island located in the White Sea (N65°52’41.60’’; E34°50’53.68’’; Fig. 1b); and (2) Mg-rich biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a as well as biotite paragneiss G20b from an outcrop close to the eastern end of the coastal village of Gridino (Fig. 1b).

Abbreviations used in the text and Figures are: apfu = atoms per formula unit (depending on normalisation mode; see Table S1); ab = albite; Am = amphibole; an = anorthite; alm = almandine; andr = andradite; Bi = biotite; Ch = chlorite; Cp = clinopyroxene; Co = coesite; Cz = clinozoisite; Di = diopside; Gl = glaucophane; gro = grossular; Gt = garnet; Im = ilmenite; Ky = kyanite; Lw = lawsonite; Max = maximum; Min = minimum; Mt = magnetite; Op = orthopyroxene; Pa = paragonite; Pl = plagioclase; pyr = pyrope; Qz = quartz; Rt = rutile; spess = spessartine; Sym = clinopyroxene-plagioclase symplectite; Tc = talc; Tt = titanite; vol = volume; Wm = white mica; wt. = weight.

Mineral compositions were determined using an electron microprobe at the Central Microanalytical Laboratory of the Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany. All data are provided in Table S1 of the supplementary material together with the respective analytical conditions and normalisation modes.

Samples G1 and G1a

Equigranular, medium-grained retro-eclogite samples G1 and G1a occur in a dm-sized boudin within a mainly tonalitic and hornblende TTG gneiss, which also include some amphibolite. Both samples are similar but differ in the amount of plagioclase which prevails in G1a. Sample G1a is also slightly banded. Due to comparable deformation style in the retro-eclogite and the surrounding TTG gneiss it is suggested that these rocks have a common deformational history (Balagansky et al., Reference Balagansky, Maksimov, Gorbunov, Kartushinskaya, Mudruk, Sidorov, Sibelev, Volodichev, Stepanova, Stepanov, Slabunov, Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019). Identical protolith ages of 2702±25 and 2745±32 Ma by U/Pb methods for zircon were determined by Skublov et al. (Reference Skublov, Astaf’ev, Berezin, Marin, Mel’nik and Presnyakov2011) and Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Zhang, Wei, Li and Guo2017), respectively. Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Zhang, Wei, Li and Guo2017) also classified the protolith of the retro-eclogite as similar to E-MORB.

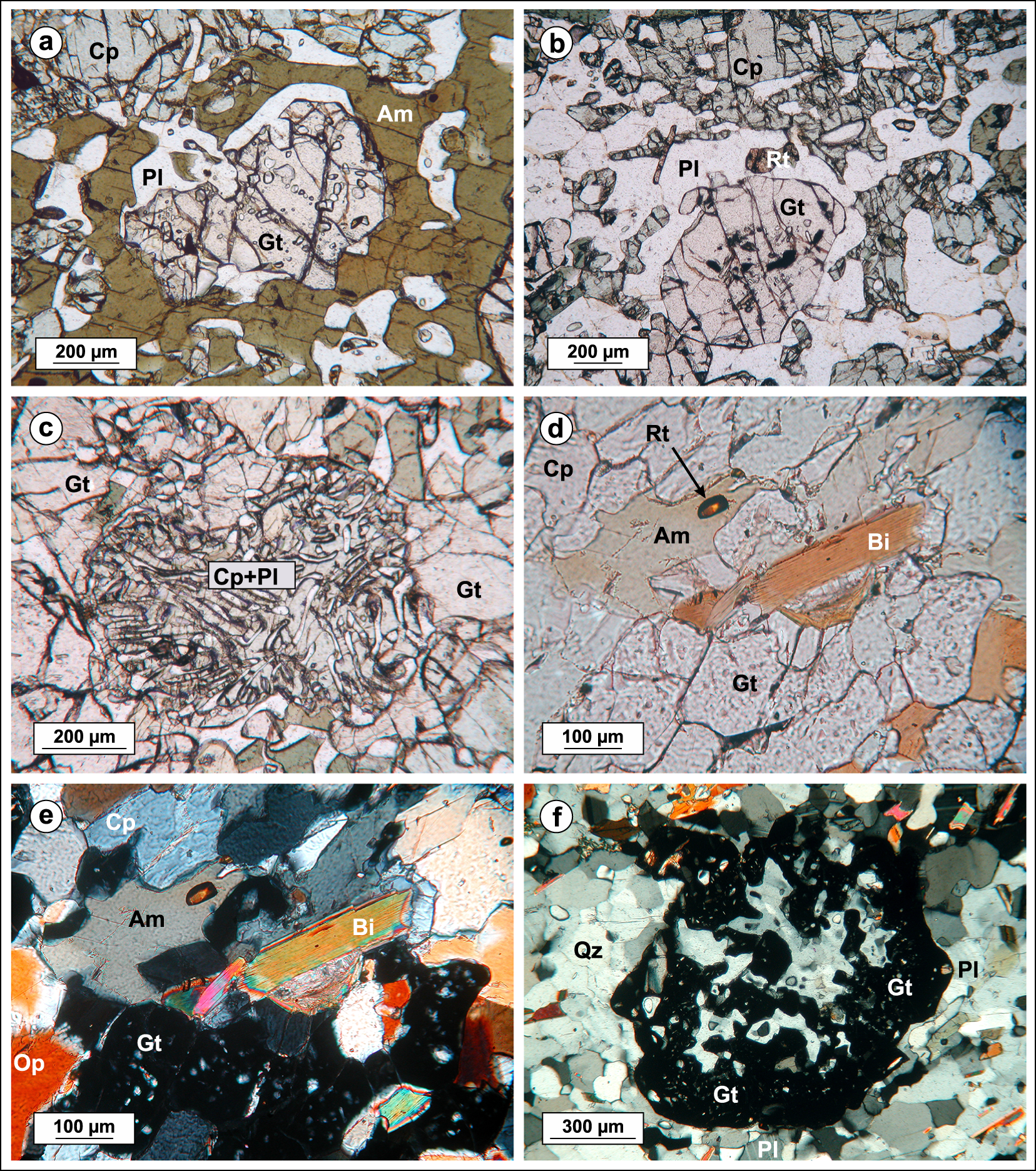

Garnet porphyroblasts (0.6–2.0 mm; Fig. 2a, b) rarely show rational grain boundaries but are generally replaced at the rims by aggregates of amphibole (0.1–0.6 mm) and plagioclase (0.05–0.2 mm), as well as by rare amphibole-plagioclase symplectites. Inclusions in the garnet core comprise clinopyroxene, amphibole, rutile, clinozoisite and quartz. Clinozoisite, however, only occurs as inclusions in garnet of sample G1a, and is absent from the matrix of both samples. Titanite and ilmenite are also present as inclusions in garnet, and also occur in the matrix of both samples, where they are retrograde phases formed at the expense of matrix rutile. Remarkably, local inclusions of chlorite and a single plagioclase inclusion occur in one single G1a garnet grain. Abundant clinopyroxene-plagioclase symplectites (0.5–1.0 mm; Fig. 2c) replaced mostly clinopyroxene at the rims. Also, amphibole and plagioclase partially replaced clinopyroxene throughout. Quartz (<0.3 mm) frequently occurs as inclusions in the core of garnet, but is also enclosed in rutile, clinopyroxene and amphibole. Rare small polygonal quartz aggregates can rarely be observed in the matrix. Pyrite, zircon and apatite are accessory phases in the matrix and may occur as inclusions in garnet. Magnetite is an accessory phase in the matrix.

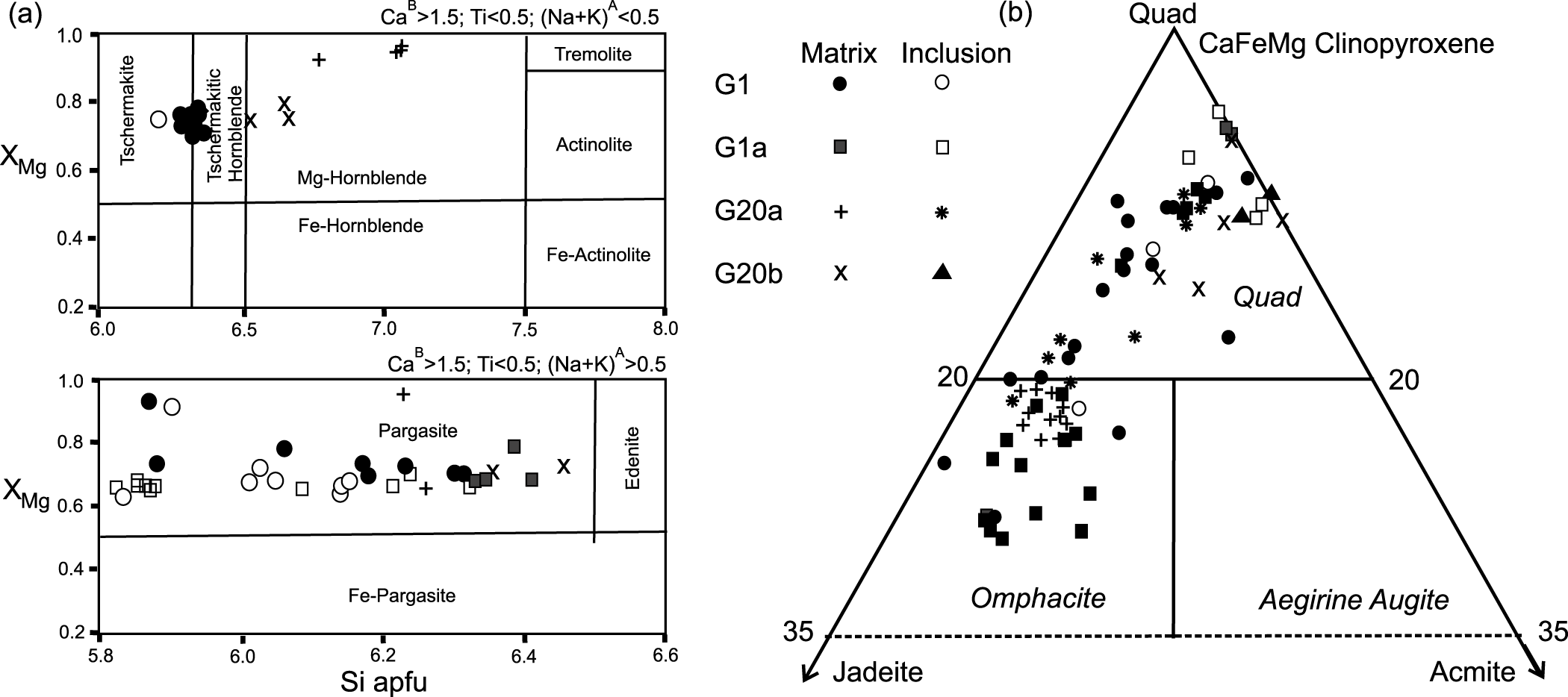

Figure 2. Micrographs from: (a) retro-eclogite G1; (b,c) retro-eclogite G1a; (d,e) biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a; (f) biotite gneiss G20c. (a) eclogite assemblage replaced to a moderate extent by plagioclase and amphibole at the grain boundaries; (b) same, extensively replaced by plagioclase; (c) clinopyroxene-plagioclase symplectites mainly replacing garnet and omphacite; (d,e) slightly foliated fine-grained biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite; (f) poikiloblastic garnet in polygonal quartz-plagioclase matrix. (a,d) Plane-polarised light; (e,f) crossed polars.

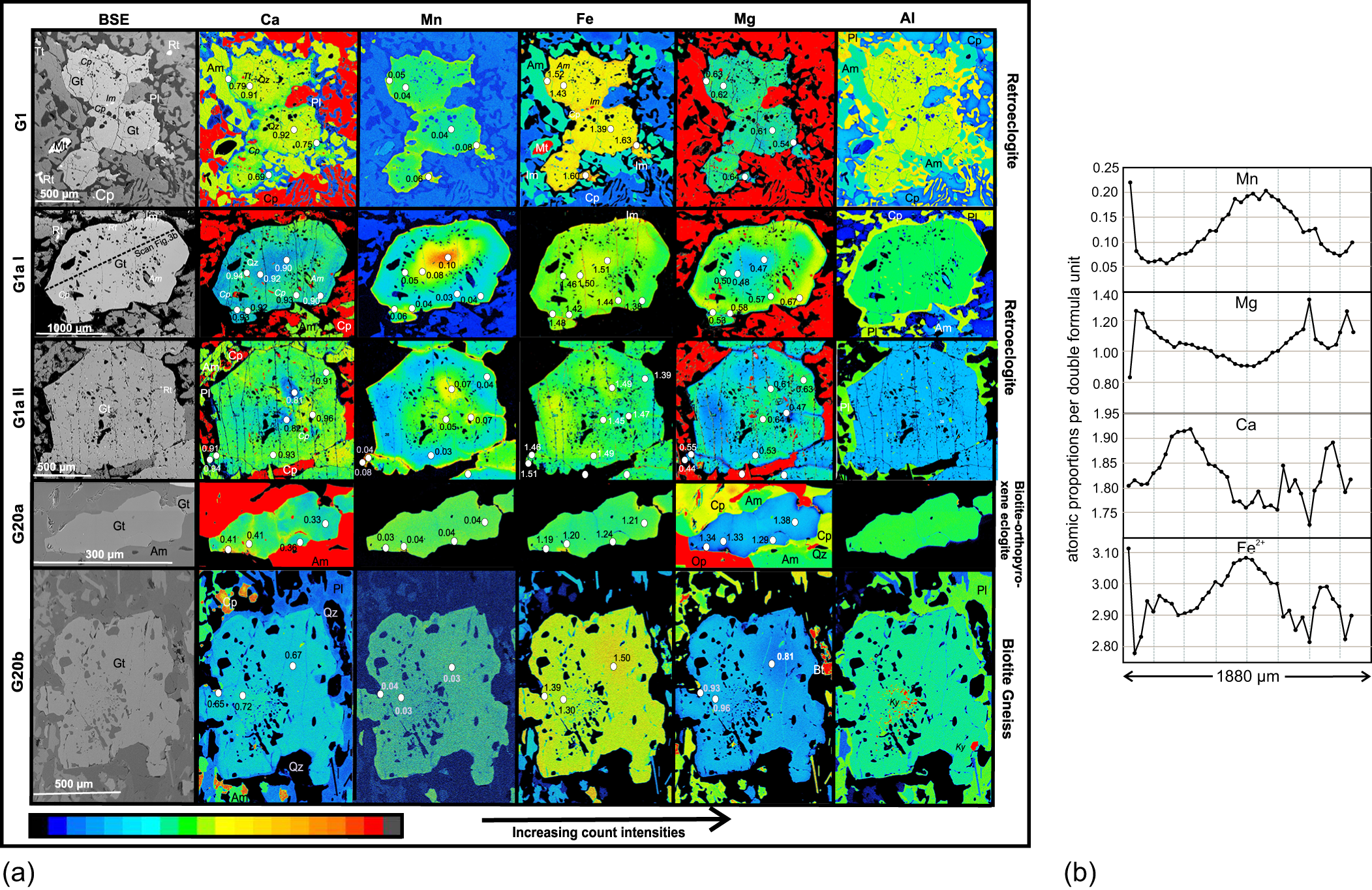

Garnet of samples G1 and G1a is mainly Ca-Mg-Fe2+ garnet with negligible andradite and spessartine components and exhibits a variably preserved relic growth zonation in its core and often a non-coherent narrow rim of only 20–50 µm (Fig. 3a, b). The inner core is usually rich in inclusions. Compositions in G1 garnet core (andr0.00–0.05gro0.26–0.30spes0.01–0.02pyr0.20–0.23alm0.47–0.49), in G1a garnet inner core (andr0.00–0.03gro0.27–0.30spes0.01–0.03pyr0.15–0.18alm0.48–0.50) and outer core (andr0.00–0.03gro0.31–0.32spes0.01–0.02pyr0.17–0.21alm0.46–0.49) show decreasing Mn and Fe and increasing Ca and Mg outwards. However, towards the outermost rim, Ca and Mg decrease again and Mn and Fe increase with corresponding rim compositions of G1 (andr0.00–0.01gro0.23–0.25spes0.02–0.03pyr0.20–0.23alm0.47–0.49) and G1a (andr0.01–0.02gro0.30–0.31spes0.02–0.03pyr0.13–0.19alm0.47–0.51). The narrow rims have diffuse borders and follow the replacement embayments of garnet. They probably originated by diffusion near peak temperature and early cooling conditions. Amphibole shows a remarkably similar wide compositional range in both samples from tschermakite over magnesium hornblende to pargasite for matrix as well as inclusion phases (Fig. 4a). An internal zoning is not detectable. Clinopyroxene in samples G1 and G1a shows a range of mainly Mg-rich CaMgFe-clinopyroxene (up to 88 mol.% diopside) to omphacite compositions (up to 24 mol.% jadeite; Fig. 4b). The compositional range of clinopyroxene in the matrix, symplectites and inclusions within garnet is similar (Fig. 4b). In general, a faint zonation can be observed with increasing Ca and Mg from core to rim, whereas Al and hence Na decrease in the same direction (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. (a) BSE images and element-distribution maps of Ca, Mn, Fe, Mg and Al of garnet porphyroblasts showing relative X-ray intensities as detected by the electron microprobe. Inserted are local quantitative element compositions (apfu). Inclusion phases are marked in italics. (b) Compositional scan across grain G1aI (see Fig. 3a).

Figure 4. (a) Compositional variations of X Mg (=Mg/Mg+Fe2+) vs. Si in calcic amphibole following the nomenclature of Leake et al. (Reference Leake, Woolley, Arps, Birch, Gilbert, Grice, Hawthorne, Kato, Kisch, Krivovichev, Linthout, Laird, Mandarino, Maresch, Nickel, Rock, Schumacher, Smith, Stephenson, Ungaretti, Whittaker and Guo1997; see also Hawthorne et al., Reference Hawthorne, Oberti, Harlow, Maresch, Martin, Schumacher and Welch2012). (b) Compositional variation of Quad (CaFeMg-clinopyroxene)-jadeite-acmite for sodic clinopyroxene following the nomenclature by Morimoto et al. (Reference Morimoto, Fabries, Ferguson, Ginzburg, Ross, Seifert, Zussman, Aoki and Gottardi1988).

Clinozoisite with X Fe (=Fe3+/(Fe3++Al)) of 0.16–0.19 only occurs as inclusions in G1a garnet. The compositional range of matrix plagioclase in samples G1 and G1a is similar (ab0.71–0.80). Exceptional is a rare plagioclase inclusion with deviating composition in one single garnet grain of sample G1a (ab0.51). This is probably a prograde plagioclase contrasting with the plagioclase in the matrix because it occurs with chlorite in the same inclusion in the same G1a garnet grain. This chlorite exhibits a large Si content of 7.66 apfu and X Mg of 0.83. There is no chlorite at peak metamorphic conditions and no retrograde chlorite. All other samples also lack chlorite.

Summarizing, the dominant matrix assemblage is rather indicative of granulite-facies: Gtrim-Cp-Sym-Am-Rt-Im-Mt-Pl-Qz, where cores of garnet, clinopyroxene, amphibole and rutile probably represent eclogite-facies relicts. Inclusions in the garnet core reveal an earlier epidote eclogite-facies assemblage: Gtcore-Cp-Am-Rt±Cz-Qz without plagioclase. Inclusions of jadeite-poor clinopyroxene as well as of rare chlorite and plagioclase with intermediate composition could represent an earlier prograde assemblage. Titanite represents a prograde precursor of rutile as well as a retrograde breakdown product of rutile.

Sample G20a

Sample G20a is a fine-grained (0.05–0.4 mm), equigranular and weakly foliated Mg-rich biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite. It is unusually Mg-rich (17.47 wt.% MgO) with a low SiO2-content (49.90 wt.%) and a Na2O+K2O content of 1.78 wt.% (Table S2 in the supplement). According to the IUGS-2002 nomenclature based on the composition of volcanic rocks (Le Maitre, Reference Le Maitre2002), the bulk rock is similar to picrite, possibly representing the protolith composition. It was sampled from a major eclogitized dyke, where samples with similar compositions are known (15.3–20.9 wt.% MgO, 48.1–49.7 wt.% SiO2, 1.52–2.29 wt.% Na2O+K2O; Balagansky et al., Reference Balagansky, Maksimov, Gorbunov, Kartushinskaya, Mudruk, Sidorov, Sibelev, Volodichev, Stepanova, Stepanov, Slabunov, Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019). Volodichev et al. (Reference Volodichev, Slabunov, Sibelev, Skublov and Kuzenko2012) classified the dyke as original gabbro-norite based on supposed magmatic relics in some rocks of the dyke and yielded an age of the intrusion of 2389 ± 25 Ma by U/Pb methods for zircon.

Garnet (0.2–0.8 mm) has mainly rounded grain boundaries with embayments due to replacement by thin films of plagioclase, amphibole and rare clinopyroxene-plagioclase symplectites. Inclusions of amphibole, biotite, orthopyroxene, clinopyroxene and rutile are abundant. Reddish-brown biotite and amphibole (both 0.05–0.5 mm) are orientated parallel to a faint foliation (Fig. 2d, e). Clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene (both 0.1–0.6mm) are common in the matrix. Plagioclase-clinopyroxene symplectites replacing clinopyroxene are rare. Pyrite, chalcopyrite, apatite, rutile and zircon are accessories in the matrix and also occur as inclusions in garnet. Quartz can form rare tiny polygonal aggregates together with plagioclase in the matrix.

In sample G20a the garnet core composition (andr0.00–0.03gro0.08–0.12spes0.01–0.02pyr0.43–0.48alm0.39–0.43) shows almost no zoning (Fig. 3), though there is some slight increase of Ca and Fe with decreasing Mg towards the weakly pronounced rim (andr0.02–0.03gro0.10–0.13spes0.01–0.02pyr0.42–0.46alm0.39–0.45). Amphibole shows a compositional range from tschermakite through magnesium hornblende to pargasite in the matrix and inclusions without internal zoning, in common with the other retro-eclogite samples (Fig. 4a). Also, clinopyroxene in sample G20 shows a similar range of mainly Mg-rich CaMgFe-clinopyroxene to omphacite compositions in the matrix, symplectites and inclusions within garnet (Fig. 4b).

Orthopyroxene is only observed in biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a and is enstatite (enstatite0.80–0.83ferrosilite0.16–0.19acmite0.03–0.06tschermak-component0.03-0.06). This compositional range is also that of matrix orthopyroxene and inclusions in garnet. Biotite composition in sample G20a is characterized by X Mg(=Mg/(Mg+Fe)) 0.81–0.83, Ti 0.41–0.48 apfu and Na 0.06–0.11 apfu. Plagioclase composition is ab0.64–0.78.

In common with previous samples, the inclusions in the core of garnet and the cores of the matrix phases define an early eclogite-facies assemblage: Gtcore-Am-Bi-Op-Cp-Rt. Due to minor replacement by plagioclase, quartz and clinopyroxene-plagioclase symplectite, the overprinting granulite-facies assemblage Gtrim-Bi-Cp-Op-Am-Rt-Pl-Qz is less pronounced.

Sample G20b

Biotite gneiss G20b is weakly foliated with a slight orientation of reddish-brown biotite (0.05–0.30mm) and slightly larger grains of green amphibole (0.05–0.5 mm), whereas garnet (0.2–0.7mm) is partly enriched in banding laminae. Garnet is generally rounded with very rare rational grain boundaries and commonly contains polygonal quartz aggregates in the cores (Fig. 2f), whereas inclusions of biotite, amphibole and clinopyroxene are rare. Abundant small, rounded rutile (0.01–0.05 mm) occurs in the matrix and forms inclusions in garnet similar to those of accessory pyrite, chalcopyrite, zircon and apatite. Quartz and plagioclase (both 0.1– 0.5 mm) form dominant polygonal aggregates in the matrix (Fig. 2f). Rare clinopyroxene-plagioclase symplectites replace clinopyroxene and partly garnet. Clinopyroxene is a minor phase observed as inclusions in garnet and the matrix. Potassic white mica is present as an inclusion in a single garnet grain. It is also very rarely observed as tiny films along grain boundaries in the matrix. Rare kyanite occurs exclusively as inclusions in garnet.

Garnet core composition in sample G20b (andr0.00–0.02gro0.20–0.32spes0.01–0.02pyr0.24–0.34alm0.40–0.51) displays a weak outward decrease of Ca and Fe and increase of Mg. In addition, towards a very narrow outermost rim, some increase of Ca, Mn and Fe with decreasing Mg is observed (Fig. 3). Amphibole composition ranges from Mg-hornblende to pargasite. In contrast to the other samples investigated, omphacite was not observed and only CaMgFe-clinopyroxene is present in sample G20b.

Biotite composition in biotite gneiss G20b is characterised by X Mg 0.65–0.73, Ti 0.32–0.59 apfu and Na 0.01–0.04 apfu. Plagioclase composition is ab0.68–0.78 with slightly increasing Ca-content from core to rim (Fig. 3). Kyanite with traces of Fe (0.02–0.03 apfu; calculated as trivalent iron) is only observed as inclusions in garnet of biotite gneiss G20b.

The dominant granulite-facies matrix assemblage of this paragneiss is Gtrim-Bi-Cp-Am-Rt-Wm-Pl-Qz, the earlier eclogite-facies assemblage is given by the inclusions in garnet: Gtcore-Cp-Am-Wm-Ky-Rt-Qz without plagioclase.

Geothermobarometry

Conditions of the pressure-peak of metamorphism

PT pseudosections and isopleths of mineral compositions were calculated in the PT-range of 10–30 kbar, 450–850°C in the NKCFMnMASHTO-system using PERPLE_X (Connolly, Reference Connolly1990, Reference Connolly2005; version 7.1.1) and the internally consistent data set of Holland and Powell (Reference Holland and Powell2011, updated data set ds62). The fluid equation of state used is a compensated Redlich-Kwong equation (CORK) by Holland and Powell (Reference Holland and Powell1998). The major element compositions analysed by XRF were normalized to 100% (Table S2 in the supplement) including water contents augmented to excess water conditions which are considered to have prevailed as free hydrous fluid particularly during prograde and peak-pressure conditions. As our pseudosection modelling involved medium as well as high-grade conditions, we are also showing how the modelling is affected under dry conditions, where minimum water contents are estimated from mol.% H2O-T diagrams for the peak pressure that would be necessary to reproduce the peak-P assemblage (see Fig. S1 in the supplement). Also, the amount of CaO was corrected for the CaO present in apatite. The applied solid-solution models are: White et al. (Reference White, Powell, Holland, Johnson and Green2014) for garnet, white mica, orthopyroxene, chlorite, ilmenite and melt (for samples G1, G1a, G20a): Green et al. (Reference Green, White, Diener, Powell, Holland and Palin2016) for clinopyroxene, clinoamphibole and melt (for sample G20b); Holland and Powell (Reference Holland and Powell2011) for epidote; Holland and Powell (Reference Holland and Powell1998) for talc and chloritoid; Holland and Powell (Reference Holland and Powell2003) for plagioclase. This configuration was tested successfully by Duan et al. (Reference Duan, Li, Schertl, Willner and Sun2022). Lawsonite, quartz, paragonite, kyanite, K-feldspar, titanite and H2O are treated as pure phases.

We derived PT conditions only for the peak-P by calculation of isopleths of a small range of X Ca, X Mg and X Fe-contents (X Ca=Ca/(Ca+Mg+Fe+Mn)) in the garnet core using the intersections within the predicted PT-field of the observed peak-P assemblage. The X Mn contents are generally too low to be reliable. Some peak-P metamorphic minerals were only observed as inclusion in garnet. Note that we only used forward pseudosection modelling to derive quantitative PT conditions for the eclogite-facies stage and show effects of resetting of phases during the high-grade overprint qualitatively.

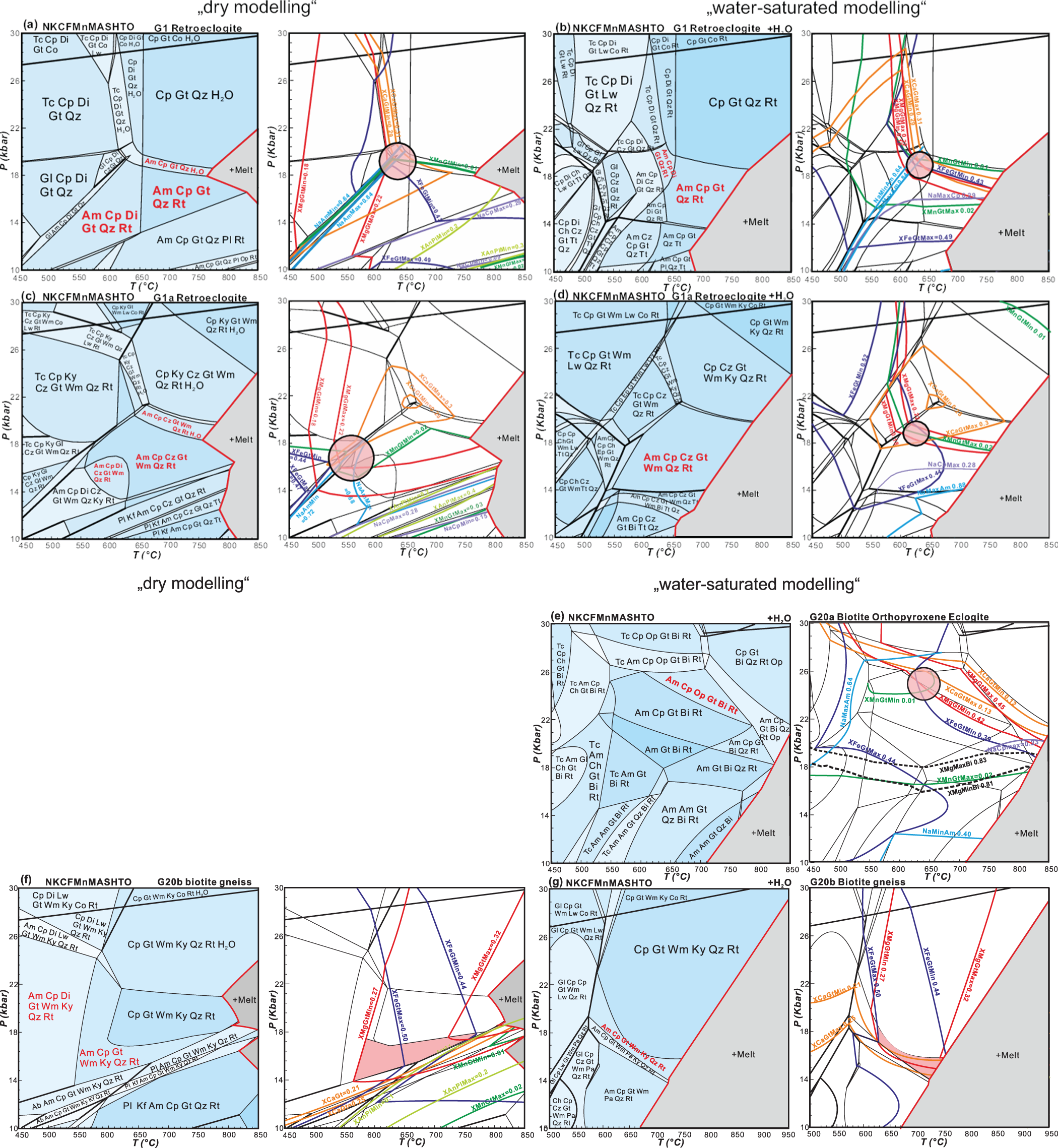

Comparing the pseudosections calculated with a minimum water content (see Fig. S1 in the supplement) with those calculated under water-saturated conditions, the following differences became apparent at medium grade (Fig. 5): in all pseudosections modelled under ‘dry’ conditions (1) garnet compositional isopleth convergence is less pronounced compared to those modelled under water-saturated conditions; (2) the predicted PT fields of the observed assemblages are wider; and hence, (3) the PT-conditions for the pressure peak are wider (cf. Fig. 5a, c and f with Fig. 5b, d and g). Most importantly, peak conditions for ‘dry’ and ‘wet’ conditions are similar, and thus the assumed water content does not alter the results. For the biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a, only ‘wet’ modelling is possible, because no biotite solid solution can be reproduced under ‘dry’ conditions. Hence, we are only extracting peak-P conditions from the pseudosections modelled under water-saturated conditions. For the high-grade conditions, both sets of pseudosections also deviate especially for the position of the tonalitic solidus. This is important for the estimation of the conditions of the temperature peak (see below). No melt occurs in the outcrops of the studied samples, nor is it reported from areas nearby.

Figure 5. (a) and (c) ‘dry modelling’ shows PT pseudosections on the left modelled for the eclogite samples G1 and G1a in the range 10-30 kbar, 450–850°C, at ‘dry’ conditions (for calculation of minimum water contents see Fig. S1) with the predicted PT-field of the observed peak-pressure assemblage marked in red. The double appearance of clinopyroxene and amphibole in calculated assemblages indicate local exsolution gaps. In the plots to the right, isopleths of a limited range of X Ca,X Mg,X Fe,X Mn-compositions in the garnet cores with intersections (in red circles) within the predicted PT-field of the observed peak-pressure assemblage are shown. Maximum and minimum Na-contents of amphibole and clinopyroxene (as apfu) as well as X Mg of biotite and X An of plagioclase indicate the approximate range, where the observed mineral compositions were stable. Some minimum contents may plot below 10 kbar. For the used whole-rock compositions see Table S2 in the supplement. (b) and (d) ‘water-saturated conditions’ show the same modelled pseudosections on the left and isopleths on the right. (e) only ‘water saturated modelling’ is possible for biotite orthopyroxene eclogite G20a. (f) ‘dry modelling’ and (g) ‘water saturated modelling’ for biotite gneiss G20b.

In retro-eclogite G1 the intersection of the divalent element isopleths for the garnet core composition plots within the PT field of the predicted peak-P assemblage Gt-Cp-Am-Rt-Qz at 610–650°C, 18–20 kbar (Fig. 5b), which matches well with the observed eclogite-facies inclusion assemblage. Only the isopleth of the maximum Fe-content in the garnet core deviates because Fe is generally more sensitive to diffusion than Ca and Mg (e.g. Carlson, Reference Carlson2006). Also, the isopleths of the observed maximum and minimum Na-contents in amphibole match with this PT stage. By contrast, although the observed maximum Na contents of clinopyroxene are at least close to the peak-P conditions, most of the clinopyroxene has much smaller Na contents. Obviously, the original jadeite component had been greater than the observed omphacite composition (maximum of 24 mol.% jadeite). In fact, an omphacite inclusion in garnet with 28 mol.% jadeite was observed by Balagansky et al. (Reference Balagansky, Maksimov, Gorbunov, Kartushinskaya, Mudruk, Sidorov, Sibelev, Volodichev, Stepanova, Stepanov, Slabunov, Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019) at the same locality. The lower Na-contents of matrix clinopyroxene can be explained by resetting during temperature increase and pressure decrease. Titanite inclusions in garnet appear in compatibility fields at much lower PT conditions than those of the peak-P. This proves titanite as a prograde relict. Similarly, the composition of clinopyroxene inclusions ranges towards diopside composition, which must also be regarded as prograde inclusions (Fig. 4b).

In retro-eclogite G1a, the predicted peak-P assemblage Am-Cp-Cz-Gt-Wm-Qz-Rt occupies a wide PT compatibility field, but the garnet isopleth intersection defines peak-P conditions at 18–20 kbar, 615–650°C (Fig. 5d), which is compatible with the less overprinted sample G1 from the same locality. The predicted peak-P assemblage almost matches the observed one, as clinozoisite occurs only as inclusions in garnet and was replaced in the matrix, but potassic white mica was not observed. This is not surprising as the calculated amount of potassic white mica is only 2.5 vol.%. However, Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023) mention white mica inclusions in garnet of some Belomorian retro-eclogite of similar composition and peak-P conditions. The observed maximum and minimum Na-contents of amphibole and clinopyroxene delimit PT-fields at lower pressure and higher temperature than the peak-P conditions. Inclusion phases titanite, ilmenite, chlorite and plagioclase (an0.51) in garnet, however, occur in compatibility fields in the PT pseudosection at much lower pressure than the peak-P conditions, but also at medium-grade.

The isopleth intersection for garnet core compositions in biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a within the predicted and observed assemblage Am-Cp-Op-Gt-Bi-Rt occurs at 610–665°C, 23.5–26.3 kbar (Fig. 5e). Whereas the maximum-Na-isopleth for amphibole is almost compatible with these PT-conditions, the observed maximum and minimum XMg isopleths of biotite and the observed maximum-Na-isopleth for clinopyroxene define conditions at lower pressures. Most of the clinopyroxene compositions even plot below 10 kbar. This proves strong resetting of amphibole, clinopyroxene and biotite compositions during the high-grade overprint.

The range of temperatures for the peak pressure conditions of biotite gneiss G20b is at 640–740°C, 15–18.2 kbar, and thus much wider compared to the other samples studied. This results particularly from the subparallel orientation of the derived PT field of the predicted and observed peak-P assemblage Am-Cp-Gt-Wm-Ky-Qz-Rt as well as the related garnet Ca- and Mg-isopleths relative to the temperature axis (Fig. 5g). The upper temperature limit is given by the appearance of melt. Kyanite is only observed as inclusions in garnet and is part of the peak-P assemblage and disappears at lower pressure and higher temperature. A rare potassic white mica inclusion was observed in garnet, but also rare white mica films along matrix-grain boundaries can occur with newly grown plagioclase towards lower P and higher T as part of a younger matrix assemblage. Biotite, part of the younger assemblage, does not occur in compatibility PT-fields above 10 kbar for sample G20b. Furthermore, Na-isopleths of amphibole and clinopyroxene also do not plot at pressures exceeding 10 kbar. Hence, the biotite gneiss appears to be the most overprinted of the samples studied. The strongly deviating conditions with respect to those of the neighbouring biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a suggest even an early resetting of the entire peak-P assemblage.

Conditions of the temperature peak of metamorphism

Geothermobarometry to detect high-grade PT conditions for the peak-T HP granulite-facies overprint in the Belomorian retro-eclogite has been applied extensively to date but has led to extremely variable results (see a summary in Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023). The application of pseudosection modelling for the high-grade event is problematic, because the determination of the effective whole-rock compositions to model the narrow garnet rims with very variable compositions is unsecure. Also, water saturation is unlikely at these conditions. Moreover, the garnet-rim composition was probably modified by diffusion during retrogression. On the other hand, reverse modelling using conventional geothermobarometry or multivariant equilibria as done with the Belomorian (retro)eclogite, mostly involves Fe–Mg exchange that is subject to diffusion during the high-grade overprint. Alternatively, we are offering to use methods that were tested to be robust at high grade and which depend only on compositions of one single mineral within a defined limiting assemblage. Hence, it is not necessary to assume that selected compositions of different minerals were in equilibrium as has been done for the calculation of multivariant equilibria.

Zirconium-in-rutile thermometry

Zr-in-rutile thermometry is applied to rutile in the limiting assemblage with quartz and zircon and was frequently tested successfully at granulite-facies conditions. During heating, rutile continuously records the temperature conditions it experiences up to the respective closing temperature which can reach 900–1000°C, and Zr is particularly immobile during later overprints (Ewing et al., Reference Ewing, Hermann and Rubatto2013). However, several calibrations are offered with quite variable results: compared to the original empirical calibrations by: (1) Zack et al. (Reference Zack, Moraes and Kronz2004); (2) Watson et al. (Reference Watson, Wark and Thomas2006) tested the T-dependence; (3) Ferry and Watson (Reference Ferry and E.B2007) the dependence on aSiO2 of the system; and (4) Tomkins et al. (Reference Tomkins, Powell and Ellis2007) the P-dependence; whereas (5) Kohn (Reference Kohn2020) developed an independent experimental calibration.

We applied this thermometer to retro-eclogite G1a and biotite gneiss G20b with sufficiently large and chemically homogeneous rutile grains in the matrix using all five calibrations. In both samples, zircon is present. Data and analytical conditions as well as single temperature estimations are listed in Table S3 in the supplement. Within uncertainties we achieved similar results for calibrations 2–5 ranging between 706±10°C and 718±9°C for retro-eclogite G1a (n=16) and from 684±21°C to 699±19°C for biotite gneiss G20b (n=17), whereas unrealistically high temperatures of 820±12°C (G1a) and 793±27°C (G20b) were derived using the original purely empirical calibration 1. Therefore, we disregard the results of calibration 1 and take weighted means of 712±5°C (G1a) and 693±9°C (G20b) for all calibrations 2–4 as conditions of the peak-T. Within uncertainties, temperatures of both samples from the two different outcrop areas are the same in spite of the fact that retro-eclogite G1a and biotite gneiss G20b have very different overprint histories.

Quartz-in-garnet elastic thermobarometry

Elastic geothermobarometry is a method for estimating metamorphic conditions from the excess pressures exhibited by mineral inclusions trapped inside host minerals (Angel et al., Reference Angel, Mazzucchelli, Alvaro and Nestola2017). By considering the Raman band positions of a quartz inclusion entrapped in garnet compared to a free quartz crystal in the matrix, one can back-calculate the inclusion strain, and hence the residual inclusion pressure and the isomeke, which is a curve of relative volume equivalency of quartz and garnet in the PT space (Angel et al., Reference Angel, Murri, Mihailova and Alvaro2019; Mazzucchelli et al., Reference Mazzucchelli, Angel and Alvaro2021).

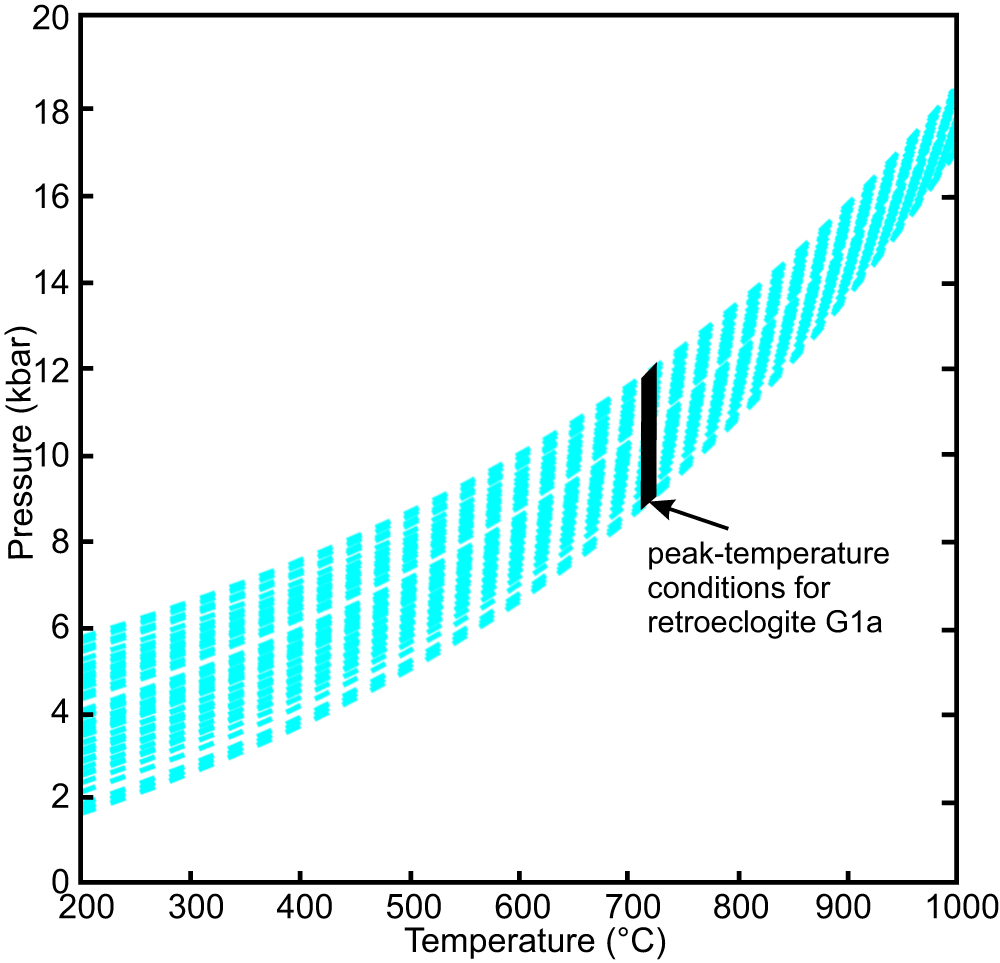

Forty three quartz inclusions in 14 garnet grains of retro-eclogite G1a were selected for Raman spectroscopy at the University of Göttingen, Germany. All considered inclusions are elastically isolated and their aspect ratio is <1:1:3, ensuring that geometric effects are negligible (Mazzucchelli et al., Reference Mazzucchelli, Burnley, Angel, Morganti, Domeneghetti, Nestola and Alvaro2018). The Raman shifts of the ∼128 cm−1, ∼206 cm−1 and ∼464 cm−1 modes were determined (compared to free quartz crystals) from the Raman spectrum by iterative curve fitting (Lünsdorf and Lünsdorf, Reference Lünsdorf and Lünsdorf2016). Inclusion strains were calculated using the Mode Grüneisen tensor of quartz (Murri et al., Reference Murri, Mazzucchelli, Campomenosi, Korsakov, Prencipe, Mihailova, Scambelluri, Angel and Alvaro2018) and the stRAinMAN software (Angel et al., Reference Angel, Murri, Mihailova and Alvaro2019). Residual inclusion pressure (Pinc) and corresponding isomekes were calculated using the EntraPT software (Mazzucchelli et al., Reference Mazzucchelli, Angel and Alvaro2021) and the equation of state for almandine (Angel et al., Reference Angel, Gilio, Mazzucchelli and Alvaro2022) and quartz (Angel et al., Reference Angel, Mazzucchelli, Alvaro and Nestola2017). All analytical details are provided in Table S4.

Residual pressure in the quartz inclusions (Pinc; n = 43) ranges between 0.2 and 2.6 kbar, with a mean of 1.4 ± 0.6 kbar at the 2σ-confidence level (Fig. S2). Variations in inclusion pressure do not correlate with a specific garnet zone (core, mantle, rim) but show a weak correlation with the distance from the garnet/matrix interface.

The isomekes plot at considerably lower pressure than the above derived peak pressure conditions (Fig. 6). Considering the above derived peak-T of 712±5°C for retro-eclogite G1a and the absence of brittle deformation, we conclude that Pinc reequilibrated by viscous creep during early decompression (e.g. Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Moulas and Tajcmanová2020). This effect was also chosen by Baldwin et al. (Reference Baldwin, Schönig, Gonzalez, Davies and von Eynatten2021) for quartz inclusions in detrital garnet from a HP/UHP metamorphic complex in eastern Papua New Guinea. Although elastic inclusion reequilibration in the sample studied was not uniform considering the notable variations of Pinc for individual inclusions, the metamorphic stage of elastic reequilibration is appropriately defined and occurred at HP granulite-facies conditions at pressures of 9–12 kbar (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Quartz-in-garnet elastic barometry for retro-eclogite sample G1a: PT-variation of the measured quartz-in-garnet isomekes; temperature range derived from Zr-in-rutile thermometry is inserted. For data see Table 4.

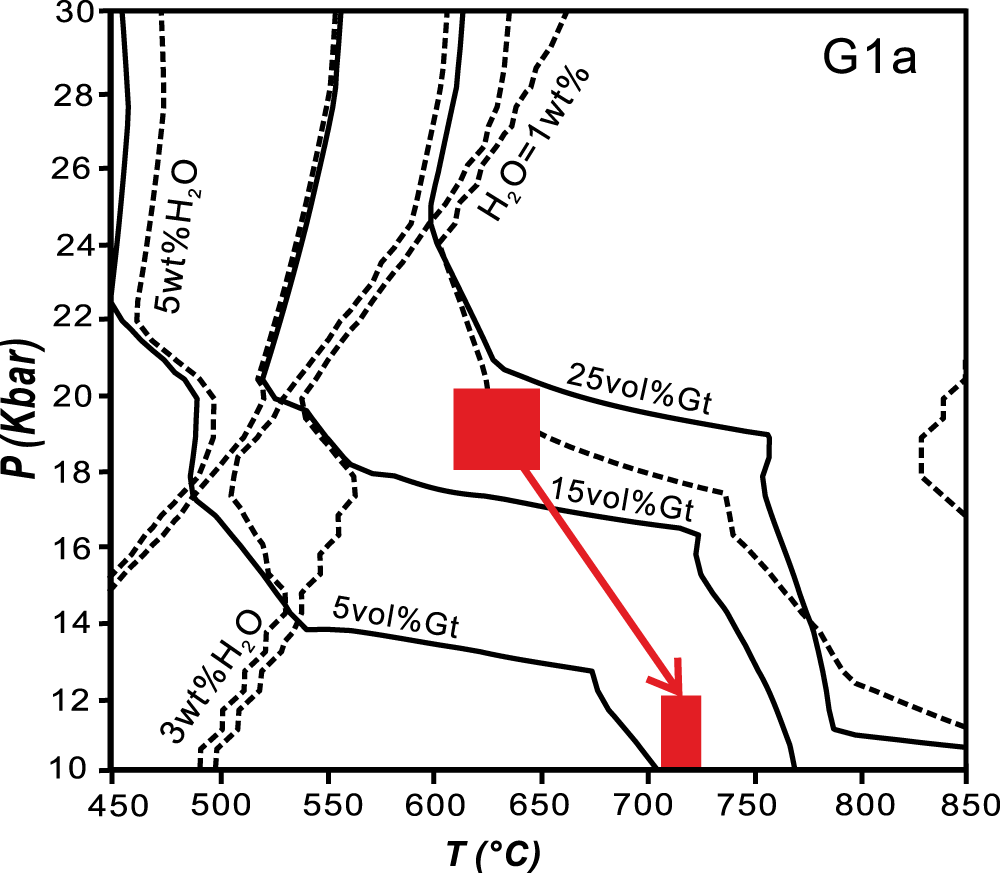

The derived PT-conditions for the HP granulite-facies event of 712±5°C, 9–12 kbar is compatible with the position of the tonalitic solidus between dry and wet conditions (no melt present) and the composition of the plagioclase formed during the PT-path between the peak-P (Fig. 5a–d) and the peak-T conditions. Figure 7 shows isolines of vol.% garnet and wt.% water bound to solids extracted from the pseudosection d for sample G1a in Fig. 5a, where this PT-path is inserted. Garnet contents decrease considerably during decompression due to decomposition to plagioclase, whereas water is already quite low and seems to have been mostly released during the prograde PT-path towards the peak-P conditions by dehydration.

Figure 7. PT-diagram with isolines of vol.% garnet and wt.% water bound to solids extracted from the water-saturated pseudosection for retro-eclogite G1a. The PT-path between peak-P and peak-T conditions is inserted.

Rb/Sr geochronology

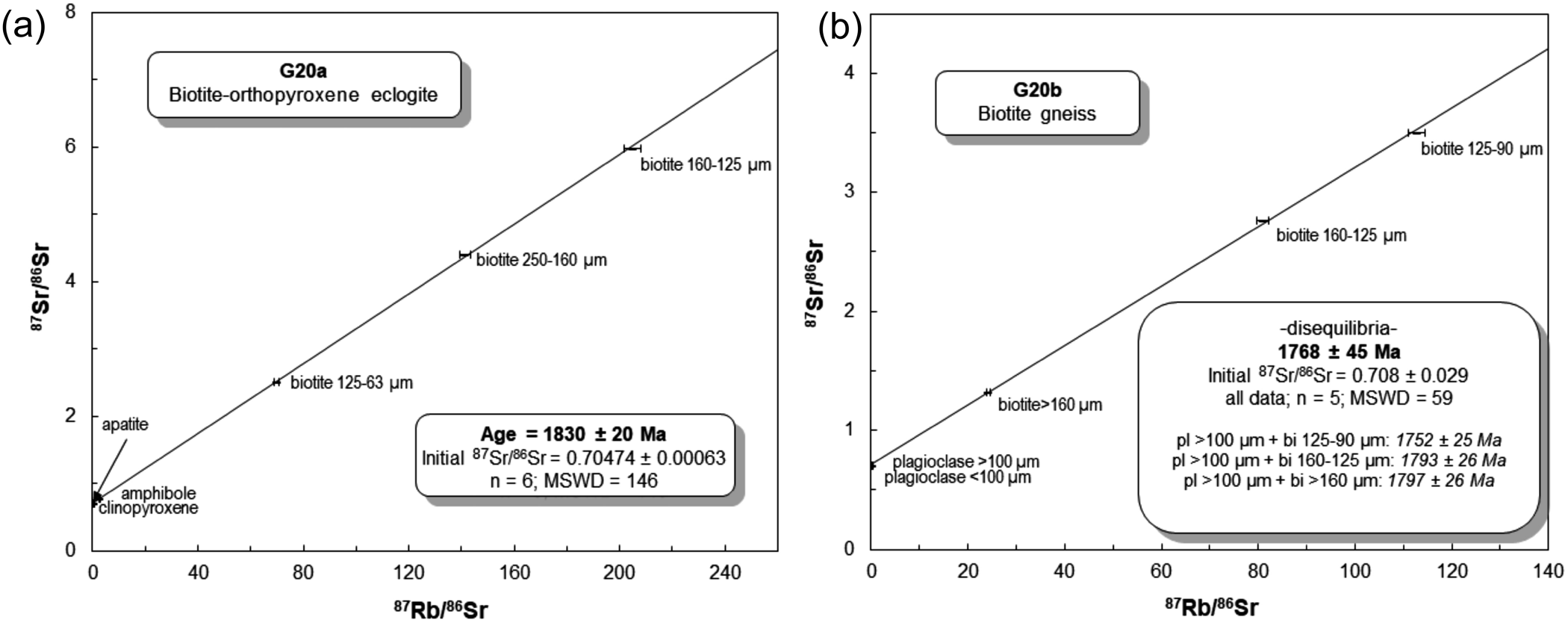

Two samples were selected for Rb-Sr radiometric age determination using a Thermo Scientific TRITON thermal ionization mass spectrometer at GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences Potsdam/Germany. Biotite-bearing assemblages were analysed in the biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a and biotite gneiss G20b. Biotite in different grain size fractions was analysed to check for possible mixed biotite populations, i.e. for pre- or early-deformational biotite relics (cf. Müller et al., Reference Müller, Dallmeyer, Neubauer and Thöni1999), and potentially protracted (re)crystallization/deformation histories. Analytical data and the experimental procedures are presented in Supplementary Table S5 and in Fig. 8.

Figure 8. Rb–Sr isochrons for samples (a) biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a and (b) biotite gneiss G20b. Isotopic data and analytical procedures are given in Table S5 in the supplement. All uncertainties are 2σ.

The regression line for Rb-Sr mineral data for sample G20a (Fig. 8a) is defined by six mineral fractions including three different biotite grain size fractions, one apatite, one clinopyroxene and one amphibole fraction yielding an age of 1830±20 Ma (MSWD 146). No correlation between grain size and apparent ages of biotite exists indicating complete metamorphic recrystallisation of biotite. The elevated MSWD is due to small but significant Sr-isotopic disequilibria between the low-Rb/Sr phases apatite, amphibole and clinopyroxene. However, because of the way the fit of isochrons is calculated, small isotopic heterogeneities among low-Rb/Sr phases, which have large weights, result in high-MSDW values, but this has no effect on the slope of the isochron. Hence, the accuracy of the age information is not affected by these disequilibria (cf. Kullerud, Reference Kullerud1991). Considering that all biotite and clinopyroxene, and partly also amphibole, show compositions attained at pressures lower and temperatures higher than the above-derived peak-P (eclogite-facies) conditions (Fig. 5c), we infer that the derived age for the biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite closely approximates the age of the peak-T (HP granulite-facies) conditions.

A substantially different age of 1768±45 Ma (MSWD 59; Fig. 8b) was obtained for biotite gneiss G20b. The five-point regression line is defined by three grain size fractions of biotite and two fractions of plagioclase. However, there are disequilibria regarding the isotopic distribution (Fig. 8b; Table S5): biotite calculated with large plagioclase (>100 µm) shows a correlation between grain size and apparent age. Thus, large grains appear older than smaller ones. By contrast, larger plagioclase grains have smaller initial Sr ratios (calculated for t = 1800 Ma) than smaller grains (0.70433 vs. 0.704677). This combination of patterns is probably caused by diffusion during slow cooling from high temperature (cf. Glodny et al., Reference Glodny, Kühn and Austrheim2008) between roughly 1800 and 1750 Ma. Considering these evidently retrograde effects that are not observed for the biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite, it can also be taken as further proof that the above-derived Rb/Sr age of the biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite probably corresponds to the peak-temperature conditions.

Discussion

Comparison with previous geothermobarometric estimates

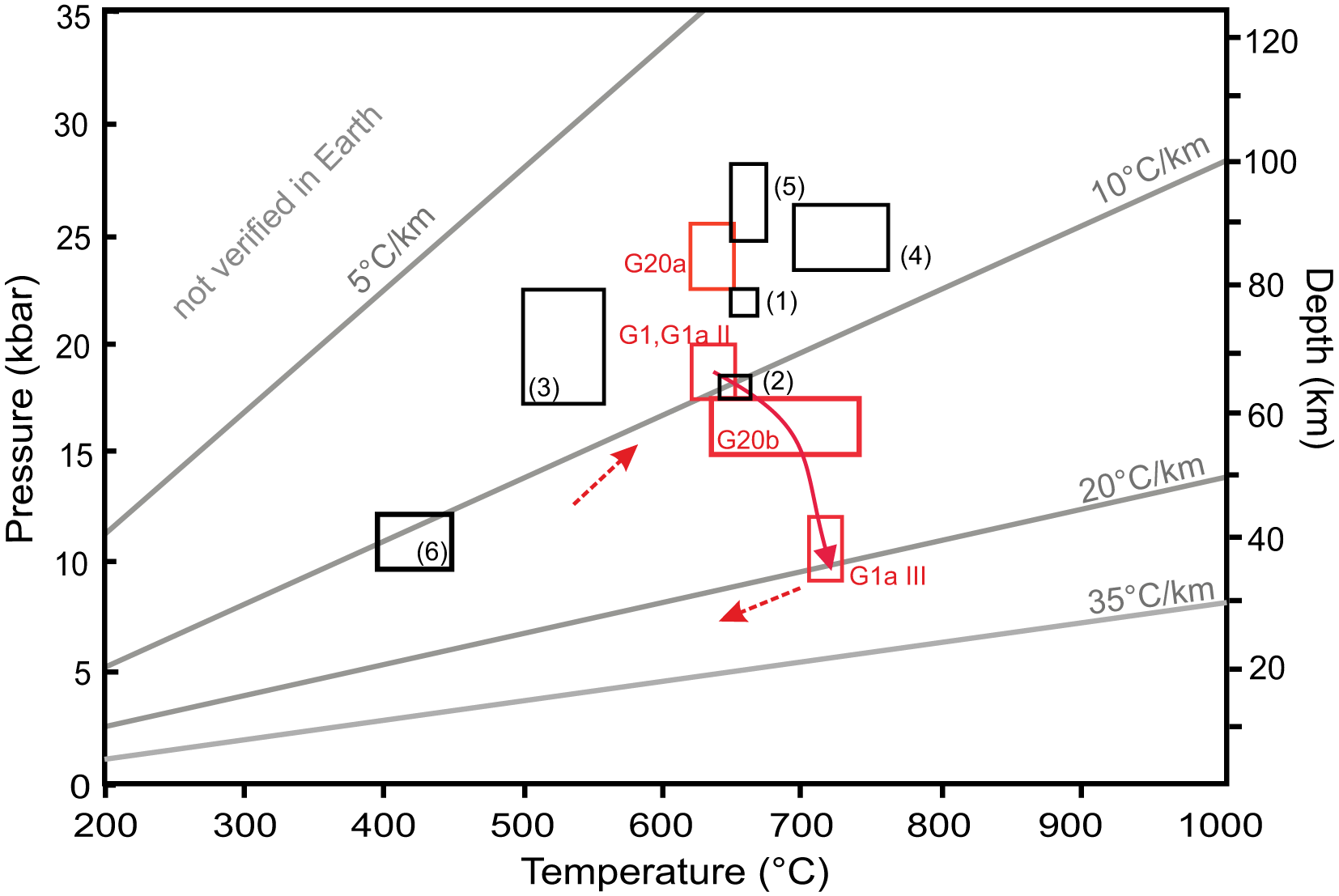

Pseudosection modelling of relict garnet core compositions in three of our studied retro-eclogite samples shows PT-conditions for the peak-P eclogite-facies stage corresponding to transient metamorphic field gradients below 12°C/km (calculated with ρ = 2.8 g/cm3 as the crustal mean density) typical for modern-style ‘cold’ subduction (Fig. 9): retro-eclogite samples G1 and G1a at 8.7–10°C/km (610–650°C, 18–20 kbar) and biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a at 6.6–8.0°C/km (610–665°C, 23–26 kbar). The pressure difference between the two sample areas (Fig. 1b) might indicate different maximum subduction depths considering that uncertainties in all geothermobarometric methods due to analytical imprecision, uncertainties in mineral activity models or accuracy of experimental calibration can be expected, which generally range in a minimum order of ∼±1 kbar, ∼±25°C at 1σ level, (Spear, 1993).

Figure 9. In red: PT-path of retro-eclogite G1a with prograde (I), peak-P (II) and peak-T (III) stages and peak-P stages of biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a and biotite gneiss G20b. In black: comparable peak-P data for other Palaeoproterozoic eclogite occurrences worldwide indicating cold subduction: (1) 1931±29 Ma retro-eclogite, Salma area (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023); (2) retro-eclogite, Gridino area (Perchuk and Morgunova, Reference Perchuk and Morgunova2014); (3) 2089±13 Ma eclogite, Congo Craton (François et al., Reference François, Debaille, Paquette, Baudet and Javaux2018); (4) 1861±5 Ma eclogite, Trans-Hudson Orogen/Canada (Weller and St-Onge, Reference Weller and St-Onge2017); (5) 1840±26 Ma eclogite North China Craton (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Kynický, Song, Tao, Li, Li, Yang, Pohanka, Galiova, Zhang and Fei2018); (6) 2.0–2.2 Ga low-grade HP schist, West African Craton (Ganne et al., Reference Ganne, De Andrade, Weinberg, Vidal, Dubacq, Kagambega, Naba, Baratoux, Jessell and Allibon2012). Four approximate transient metamorphic field gradients are inserted. Gradients between 5 and 12°C indicate cold subduction conditions.

Our data deviate considerably from former PT estimates of the peak-P eclogite-facies stage of rocks that occur at almost the same localities: 750°C, 14 kbar (Balagansky et al., Reference Balagansky, Maksimov, Gorbunov, Kartushinskaya, Mudruk, Sidorov, Sibelev, Volodichev, Stepanova, Stepanov, Slabunov, Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019) and 740–865°C, 14–17.5 kbar (Volodichev et al., Reference Volodichev, Slabunov, Bibikova, Konilov and Kuzenko2004) near samples G1 and G1a as well as 765–930°C, 15–19 kbar (Balagansky et al., Reference Balagansky, Maksimov, Gorbunov, Kartushinskaya, Mudruk, Sidorov, Sibelev, Volodichev, Stepanova, Stepanov, Slabunov, Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019) near sample G20a. These estimations would imply ‘warm’ gradients and subduction conditions. We envisage the main reason for this deviation to be that all previous geothermobarometry involved Fe/Mg exchange between minerals considered to be in equilibrium. However, the respective Fe/Mg ratios were changed to variable degrees in different phases during diffusion and recrystallisation, when decompression and heating to HP granulite-facies conditions occurred. Dohmen and Chakraborty (Reference Dohmen and Chakraborty2003) also showed that the presence or absence of small water films between phases in mutual contact (considered a reliable sign of equilibrium) can have a strong influence on redistribution of elements during polymetamorphic stages. In a similar way, the peak-T granulite-facies conditions were probably overestimated previously: whereas 750–900°C, 11–14 kbar (Balagansky et al., Reference Balagansky, Maksimov, Gorbunov, Kartushinskaya, Mudruk, Sidorov, Sibelev, Volodichev, Stepanova, Stepanov, Slabunov, Slabunov, Balagansky and Shchipansky2019) and 750–850°C, 12–15 kbar (Volodichev et al., Reference Volodichev, Slabunov, Bibikova, Konilov and Kuzenko2004) were previously considered to result from rocks that occur near sample G1a, we derived conditions of 712±5°C, 9–12 kbar using geothermobarometric methods independent of any Fe/Mg exchange. Note that these differences also imply differences in pressures. Thus, PT differences between the eclogite and HP granulite-facies stages could not be clearly separated previously. Using our geothermometry approach, the temperature for the HP granulite-facies overprint could reliably be derived in the same way for rocks of very different overprint histories after the peak-P stage as retro-eclogite G1a and biotite gneiss G20b.

It should also be noted here that biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite is known as a high-temperature eclogite variety (T>700°C) occurring as xenoliths in kimberlites (Jacob, Reference Jacob2004) or in the high-grade Western Gneiss Region of the Norwegian Caledonides (e.g. Lappin and Smith, Reference Lappin and Smith1978). According to Nakamura (Reference Nakamura2003) it is essentially the picritic whole-rock composition that is responsible for the stabilisation of orthopyroxene and biotite at HP/HT conditions compared with eclogite of ‘normal’ basaltic composition. Our pseudosection modelling of the Belomorian biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite, however, shows that its eclogite-facies assemblage including biotite and orthopyroxene is already stable at somewhat lower temperatures than previously thought.

The PT values (650–670°C, 22–23 kbar) for the eclogite stage derived by Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023) for the Salma area in the northern part of the Belomorian belt by pseudosection modelling is within the range of our samples. Also, an earlier PT estimation by using a multivariant reaction approach by Perchuk and Morgunova (Reference Perchuk and Morgunova2014) for an eclogite in the Gridino area straddles the 10°C/km gradient (Fig. 9). This shows that the suggestion by Li et al. (Reference Li, Zhang, Wei, Bader and Guo2023) that their geothermobarometric data are not a local effect is correct. In addition, the method used to reach a correct gradient rather depends on the type of geothermobarometric approach chosen for this special combination of a still medium-grade eclogite event combined with a HP granulite-facies overprint during early decompression that causes considerable and variable resetting of mineral compositions.

However, according to our modelling, biotite gneiss G20b shows more variable conditions (640–740°C, 15–18 kbar) at much lower pressure and thus a higher gradient than biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a occurring in close vicinity. Evidently this metapelitic rock already re-equilibrated during early exhumation, because it probably contained more free H2O released during metamorphic reactions near peak-T conditions and early decompression than the eclogite which is entirely embedded in relatively dry TTG gneiss of magmatic origin.

In spite of the high temperatures recorded for the peak-T of the Belomorian retro-eclogite and its possible slow exhumation and cooling, initial compositions attained after subduction to maximum depths are evidently still preserved in garnet cores only. Most likely, the overall dry conditions in the retro-eclogite (containing few OH-phases only) hampered re-equilibration. Dry conditions are shown by abundant symplectites and are due to the location of the eclogite bodies within the enveloping TTG-orthogneiss (which probably also released very little water during metamorphism). The effects of intergranular element and isotopic exchange between neighbouring phases at high grade mediated by a fluid phase were studied experimentally by Dohmen and Chakraborty (Reference Dohmen and Chakraborty2003). In our case, changes evidently occurred to a limited and variable extent only at the garnet rims, whereas the cores remained little affected. In contrast, element and isotopic exchange in biotite during the high-grade event was complete.

PT-path and geodynamic considerations

Besides the Belomorian retro-eclogite, at least two additional Palaeoproterozoic eclogite occurrences worldwide became known in recent years, which record peak-P conditions indicating metamorphic field gradients <12°C/km during subduction (Fig. 9). These are, for instance, eclogite of the Congo Craton (Francois et al., Reference François, Debaille, Paquette, Baudet and Javaux2018), and of the Trans-Hudson Orogen/Canada (Weller and St-Onge, Reference Weller and St-Onge2017). In addition, in the West African craton of Burkina Faso (Ganne et al., Reference Ganne, De Andrade, Weinberg, Vidal, Dubacq, Kagambega, Naba, Baratoux, Jessell and Allibon2012) in 2.0–2.2 Ga old low-grade schists, HP metamorphic conditions of 400–450°C, 10–12 kbar (geothermal gradient of 10–12°C/km) were noted, representing blueschist-facies equivalents.

On the other hand, our derived conditions for the peak-T granulite-facies conditions of 712±5°C, 9–12 kbar straddle the relatively cold 20°C/km gradient (Fig. 10), which is common in old cratonic crust and unlikely to be related to any magmatic event. Pressures for this high-grade event are very similar to those derived by other authors in the Belomorian belt, but our temperature estimation is rather at the lower end of the range of earlier estimations, which may even exceed 800°C (see above). This could also be one explanation for the preservation of peak-P conditions in garnet. We also confirm an overall clockwise PT-path observed by all previous researchers. A retrograde decompression path can also be inferred because during cooling below 700°C and pressure release below 10 kbar, titanite became stable according to the PT pseudosections in Fig. 5; titanite grew at the expense of rutile as observed in the matrix of the retro-eclogite.

Figure 10. Summary probability plot of all ages (and their 2σ uncertainties) of the Palaeoproterozoic metamorphism in the Gridino area derived in this work and literature data (see Fig. 1b).

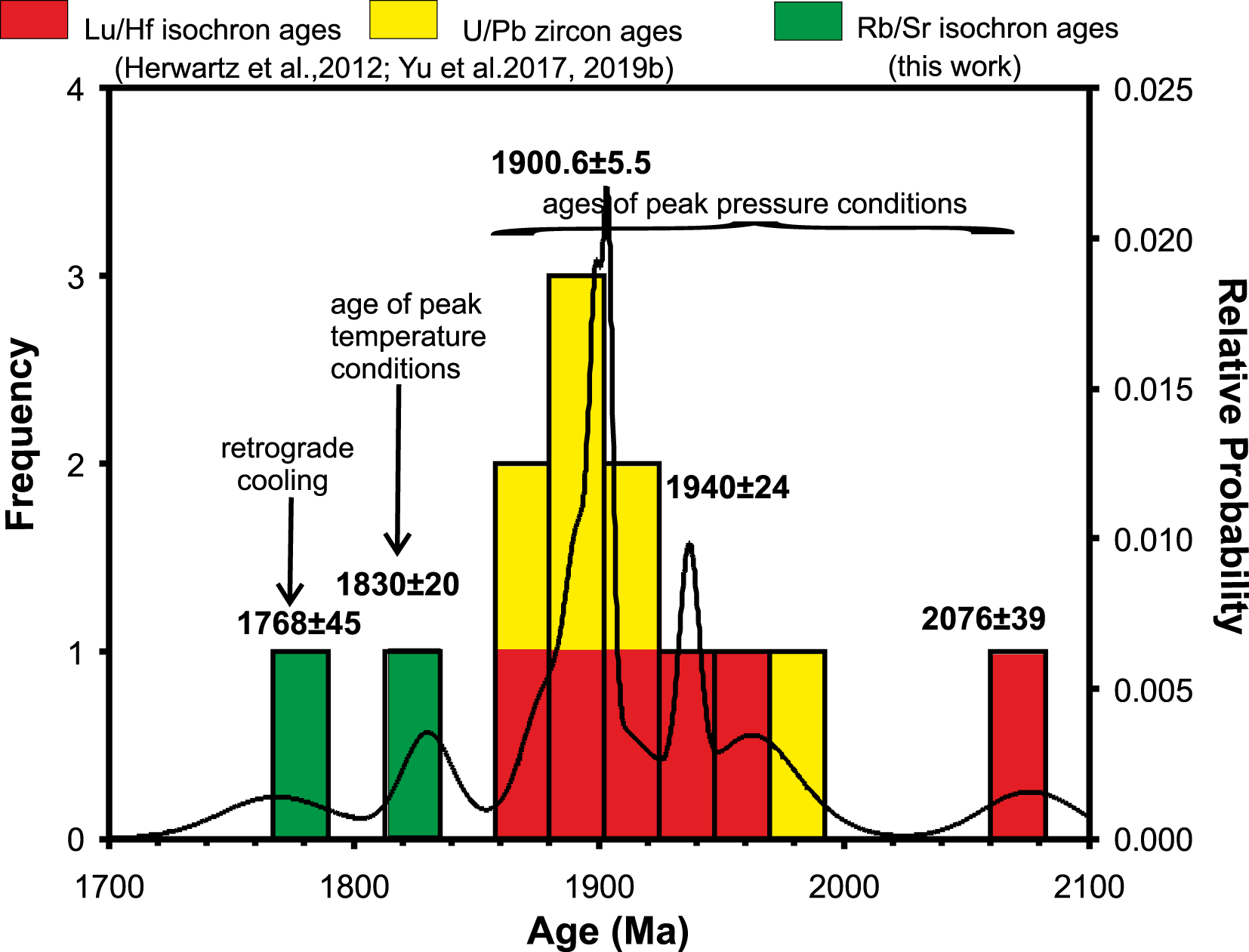

Age of the granulite-facies overprint and early exhumation rates

The derived conditions for the eclogite-facies peak-P and HP granulite-facies peak-T in combination with age determination of these events allows an estimation of early exhumation rates for the retro-eclogite in the Gridino area. We were the first to determine the age of the granulite-facies overprint and, helpfully, a previous age determination of the eclogitic assemblages has been undertaken for six samples in close vicinity to our samples on Stolbikha Island and east of Gridino village by Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Zhang, Lanari, Rubatto and Li2019b) and Herwartz et al. (Reference Herwartz, Skublov, Berezin and Mel’nik2012) applying both Lu/Hf radiometric age determination of garnet-bearing assemblages and U/Pb methods for metamorphic zircon on the same samples (Fig. 1b). Age ranges in both localities, both systems and for both author groups are similar. The Lu/Hf isochrons give the age of the eclogite-facies peak-P stage of metamorphism, because Lu is generally fractionated into the garnet cores where early eclogite-facies conditions are preserved (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Weyer, Mezger, Scherer, Yilin, Hoefs and Brey2008). However, a probability plot of all ages of both author groups (Fig. 10) shows that some older ages differ from the weighted mean age for most ages of 1901±6 Ma. Note that our derived Rb/Sr age for the peak-T granulite-facies stage of biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite G20a at 1830±20 Ma is still significantly lower than this value and instead gives the age of recrystallisation during the HP granulite overprint (Fig. 10). The duration of the early exhumation, i.e. from peak-P to peak-T depths would result in a range of 45–97 M.y. (including uncertainties). On the basis of the mean of all peak-P ages at 1906±13 Ma, this duration would be of the order of 69–83 M.y. (including uncertainties). For retro-eclogite G1a we derived peak-P and peak-T conditions equivalent to an exhumation from a depth of 64–71 km to a depth of 31–42 km (using a mean ρ = 2.8 g/cm3 for the crust). Using the above-derived exhumation durations, estimated exhumation rates during early decompression and heating from peak-P to peak-T are in the range 0.23–0.89 mm/y.

Such low overall exhumation rates of <0.9 mm/yare only an order of magnitude greater than general mean erosion rates of 0.05 mm/y (Ring et al., Reference Ring, Brandon, Willett, Lister, Ring, Brandon, Lister and Willett1999) and similar to rates of 0.2– 0.8 mm/y for erosion-controlled exhumation of accretionary wedges in California and Chile (Ring and Brandon, Reference Ring, Brandon, Ring, Brandon, Lister and Willett1999; Willner et al., Reference Willner, Thomson, Kröner, Wartho, Wijbrans and Hervé2005). Hence, we conclude that erosion was the main exhumation process and heating towards peak-T during early exhumation was probably due to thermal relaxation. Similarly, the significantly lower Rb/Sr date for the biotite gneiss G20b (1768±45 Ma; Fig. 8b) and its diffusion-related Sr-isotopic disequilibrium pattern points to slow cooling and possible retrograde deformation during continued exhumation.

However, it should be noted that, for instance, O’Brien (Reference O’Brien1997) observed preserved growth zonation in garnet of eclogite in the central mid-European Variscides that were overprinted at granulite-facies conditions. With diffusion modelling he could show that the high-temperature event was rather short, compatible with the extreme exhumation rates in that part of the orogen. This is certainly a good explanation for the preservation of growth zonation. Obviously, such explanation seems to contradict our proposed slow exhumation or a short heating/cooling event appeared during exhumation. To solve this discrepancy is beyond the scope of the present study.

Conclusions

Relict conditions for the eclogite-facies peak-P of the Belomorian retro-eclogite and the biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite are mainly preserved in garnet cores and can reasonably be quantified by pseudosection techniques. This allows us to detect initial metamorphic field gradients of <12°C/km during the Palaeoproterozoic subduction to maximum depth. Taking low T/P gradients as a proxy, this finding confirms earlier reports from Karelia and some other Palaeoproterozoic eclogite occurrences world-wide that modern-style subduction conditions were established on Earth for the first time around 2 Ga ago. In the global compilation of metamorphic PT gradients by Brown and Johnson (Reference Brown and Johnson2018) with few of our own supplements (Fig. 11) it becomes evident that our peak-P data plot into a time-restricted field of low T/P gradients, whereas the peak-T data show intermediate T/P gradients which are common since the Mesoarchaean. This time-restricted period coincides roughly with the Orosirian period (1.80–2.05 Ga), when further, modern-style, plate-tectonic features emerged. As pointed out by Stern (Reference Stern2023), such features are ophiolites, passive margins, high relief, palaeomagnetic constraints, ore deposits and seismic images of subduction zones. The following one billion yr period of plate tectonic quiescence until the start of new plate tectonics in the Neoproterozoic is attributed to minor reorganisation between the supercontinents Columbia and Rodinia (Brown and Johnson, Reference Brown and Johnson2019; Brown, Reference Brown2023) perhaps involving a stagnant-lid phase (Stern, Reference Stern2023; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Chen, Palin, Li, Zhao, Li, Li, Li and Li2024).

Figure 11. Metamorphic thermobaric ratios (T/P) plotted against ages redrawn after Brown and Johnson (Reference Brown and Johnson2019) and Brown (Reference Brown2023). The worldwide collection by Brown and Johnson (Reference Brown and Johnson2019) and Brown (Reference Brown2023) was supplemented by data (1-3) in Fig. 9 and the peak-P and peak-T conditions of the retro-eclogite in the Gridino area derived in this study. The violet bar indicates the Orosirian period (1800–2050 Ma) when the first modern-style plate tectonic conditions were probably established (Stern, Reference Stern2023).

The Belomorian retro-eclogite studied was strongly overprinted at granulite-facies conditions during early exhumation to peak-T conditions around 712±5°C, 9–12 kbar along a transient metamorphic field gradient of 20°C/km probably by thermal relaxation, whereby most mineral compositions were reset to variable degrees. We were able to determine the time of the peak-T conditions with a Rb/Sr multi-mineral age at 1830±20 Ma for a biotite-orthopyroxene eclogite and derive very slow early exhumation rates of <1 mm/y. This is confirmed by a younger Rb/Sr isochron at 1768±45 Ma for a neighbouring biotite gneiss with an isotopic distribution pattern of disequilibria characteristic of slow cooling during continued exhumation.

In recent years many new discoveries of Palaeoproterozoic eclogite worldwide have been made. These rocks may potentially show evolutions comparable to the Belomorian eclogite, and we strongly recommend that these occurrences are studied again, applying a combination of different isotope systems regarding age determination and P-T pseudosection modelling plus traditional geothermobarometrical methods, as presented here. The more information that we have about the Orosirian period and before, the more it will become apparent that the transition from hot to cold subduction is a secular process of cooling since the Neoarchean as required by Holder et al. (Reference Holder, Viete, Brown and Johnson2019), and not an abrupt event.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2025.10117.

Acknowledgements

Samples were taken during a field trip related to the 13th International Eclogite Conference 2019 in Petrozavodsk, Karelia. The attendance of APW was funded by the German Academic Exchange Service, DAAD. The authors thank B.W.D. Yardley and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive criticism, A. Slabunov, V. Balagansky and A. Shchipansky for their guidance in the field, J.P. Gonzalez for discussions on elastic geothermobarometry and R. Romer and U. Knittel for advice. No other funding was available for this study.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.